Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI

TANJUNGPINANG, KEPULAUAN RIAU] Date: 13 January 2016, At: 17:34

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Cyber Dimensions: Using World Wide Web Utilities

to Engage Students in Money, Banking, and Credit

Scott E. Hein & Katherine Austin Stalcup

To cite this article: Scott E. Hein & Katherine Austin Stalcup (2001) Cyber Dimensions: Using World Wide Web Utilities to Engage Students in Money, Banking, and Credit, Journal of Education for Business, 76:3, 167-172, DOI: 10.1080/08832320109601305

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320109601305

Published online: 31 Mar 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 15

View related articles

Using World Wide Web Utilities to

Engage Students in Money,

Banking, and Credit

SCOTT E. HElN

KATHERINE AUSTIN STALCUP

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Texas

Tech

University Lubbock, Texass academia moves into an age of

A

information technology and active learning, all faculty are being chal- lenged to use technology to engage stu- dents. Historically, active learning has included faculty-to-student interaction, student-to-student interaction, and stu- dent-to-content interaction. Academi- cians now agree that the concept of edu- cational interaction must be expanded to include student-to-interface activities(Hillman, Willis,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Gunawardena,1994). Research supports the premise that computer-assisted instruction (Kulik & Kulik, 1986) contributes posi- tively to learning and performance. Zack (1995) found that electronic mes- saging earned very favorable student reviews in a business administration class. Students concluded that the tech- nology improved the “professor’s effec- tiveness, accessibility, responsiveness, and the quality of the course overall.” In this vein, we hypothesized that students would benefit from the incorporation of technology into the learning and teach- ing process.

In this article, we describe and exam- ine the pedagogic foundations behind the technology selection and implementation process in an undergraduate finance course. In particular, we discuss the inte- gration of Web pages and threaded dis- cussions into the course, along with our observations on enhanced student perfor-

ABSTRACT. All business school fac- ulties increasingly are being chal- lenged to use technology to teach and engage today’s student more effective- ly. In this article, we describe and examine the pedagogic foundations behind the selection of new technolo- gy tools and their implementation in an undergraduate finance course. The discussion focuses on the use of a course Web page and, more particular- ly, threaded discussions as new tools to help educate and engage students. We also provide preliminary evidence

on the effectiveness of these tools.

mance. We close with suggestions for future directions for related study.

Course Overview

The World Wide Web and threaded discussions have been employed in Principles of Money, Banking and Credit (PMBC), a junior level finance course at Texas Tech University. It is similar to courses such as Financial Institutions and Financial Markets (FIM) at many schools but probably devotes a little more time to the money supply process and monetary policy than FIM courses usually do. The course is required for all finance stu- dents, international business majors, and financial planning majors.

The textbook

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

The Economics ofMoney, Banking, and Financial Markets

by Frederic S . Mishkin (1998) was used

initially. More recently, Financial Mar-

kets and Institutions, by Frederic S .

Mishkin and Stanley G. Eakins

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(2000),has been adopted. The course has three major areas of emphasis: (a) financial markets, (b) financial institutions, and (c) central banking and monetary poli-

cy. There is no separate section devoted

to international finance, but internation- al issues are addressed throughout the semester in each of the three areas.

Besides the textbook, students are required to read the Wall Street Journal’ for several reasons. Most important, the subject area is changing so rapidly that some of the textbook information is out of date. For example, the text describes Glass-Steagall banking regulations, which were greatly modified in late 1999. Further, we felt that students learn more when they see their studies as rele- vant to the real world, and the Wall Street

Journal brings home that relevance. Student assignments in the course traditionally entail in-class quizzes

(which take between

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 and 10 minutesto complete), one or two take-home assignments in financial mathematics, and three or four in-class exams. The exams take 50 to 75 minutes to com- plete and are composed of multiple- choice and true/false questions. Ques- tions on quizzes or exams are drawn

from the textbook, the Wall Street Jour-

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

nal, or lectures.

January/February 2001 167

Pedagogic Foundations

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Clearly, technology for its own sake is not worth the student’s or the faculty member’s efforts. We employed tech- nology to reinforce and advocate sound pedagogic strategy. We identified six pedagogic foundations for examining, evaluating, and selecting technologies for the classroom. Our first pedagogic element concerns the type of informa- tion in a particular course or subject. In general, course topics and objectives are a combination of symbolic, procedural, or conceptual information (Shute, 1995).* Upon analysis, we concluded that the PMBC course is heavily proce- dural, requiring students to master a variety of mathematical procedures and calculations. Research and evaluation have indicated that procedural or skills- based courses are a natural partner for

Web-based technologies (Zanglein

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

&Stalcup, 1999).

The second pedagogic issue involves deciding between the linear and nonlin- ear instructional approaches in course activities and d e l i ~ e r y . ~ The PMBC course approach clearly should be lin- ear, requiring students to master a cer- tain level of terminology and definition and then to apply this knowledge before continuing to the next application. Cer- tain technologies lend themselves better to a linear instructional approach as opposed to a nonlinear, less structured approach (Smith & Stalcup, 2001).

The third pedagogic issue concerns the need for active participation and col- laboration in the classroom. Though research indicates that active and partic- ipative learning produces better long- term retention, quite often the practical limitations of class size, room configu- ration, and teaching style prohibit stu- dent discussion and participation in the traditional classroom (Brandon &

Hollingshead, 1999, p. 110). Current research indicates that computer-based collaboration facilitates greater commu- nication with peers and discussion of course concepts (King, 1994) and can be effective in generating positive acad- emic and affective outcomes in a tradi- tional classroom setting (Johnson, John- son, & Smith, 1991; O’Donnell &

O’Kelly, 1994; Slavin, 1991). In our particular case, the PMBC class is

taught as a large lecture class, often including about 200 students per sec- tion. The instructor hypothesized that technology could provide a forum for collaboration and student interaction, creating an active learning environment. The fourth pedagogical criterion con- cerns the reinforcement and encourage- ment of higher order thinking skills such as application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation (Bloom, 1956). We anticipated that allowing students to collaborate and interact on reading assignments and course questions would help them to analyze and evalu- ate outside materials, as well as course materials. Further, certain technologies might create an exploratory environ- ment, which would encourage students to assimilate various core principles with outside materials.

For our

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

fifth pedagogic element, wewanted to evaluate the type of commu- nication necessary in the classroom. Synchronous communication requires that both communicators be present simultaneously, either in person or via a technology that permits instant commu- nication. Asynchronous communication implies that there is a delay in time between the sending and receiving of information. Clearly, in a class of 200, the limited amount of interaction between the instructor and the students is synchronous. Our hypothesis was that we could use asynchronous technology tools to enhance communication among students in the classroom.

Our last pedagogic foundation requires that we provide adequate resources for students to master any technology employed. Given that stu- dents have differing levels of technolog- ical experience, we must offer them training and practice opportunities. Our goal was to empower students to use an

additional learning tool. We therefore wanted to select technologies that the College of Business Administration and Texas Tech University could support.

Technology Selection

Given our pedagogical framework and focus, we selected two technologies to enrich the classroom experience and enhance the learning process (Kulik &

Kulik, 1986, p. 82). We selected thread-

ed discussions as an asynchronous com- munication tool to increase course dis- cussion and participation outside the classroom. Althaus (1997, p. 159) rein- forced this selection when identifying four advantages to threaded discussion technology: place independence, time independence, structured communica- tion, and rich communication. Place independence suggests that students can communicate thoughts and ideas from any Internet-connected computer. Stu- dents are free to use college and univer- sity resources as well as home resources. Second, the students have the convenience of working and contribut- ing on their own time schedules. Hence, we would expand the course time to any time that the student is contributing to the threaded discussion. Threaded dis- cussion technology also provides a structure for many-to-many discussions. Using simple Web-based threaded dis- cussions, each student can record his or her message for all to review and respond to.4 Students also can take time to reflect and respond, which enhances the communication.

We reasoned that threaded discussion technology would add an active learn- ing element to the PMBC course struc- ture. Students would attend a lecture and use the threaded discussion to inter- act with peers and the instructor outside of class time. In terms of higher-order thinking skills, computer-mediated communication tools “teach us new ways of expressing ideas and new ways of interpreting ideas; new ways of rais- ing questions and answering questions; it offers a new relationship among our actions and our solving problems” (Olaniran, Savage, & Sorenson, 1996, p. 245). Further, the threaded discussion would expose the student to “alternative points of view (and) can challenge hisher initial understanding and thus motivate learning” (Glaser & Bassok, 1989, p. 644). As the technology is Web based and does not require additional software, the college and university have ample resources to support the fac- ulty and students using it in the course.

A second technology tool that we selected is the World Wide Web, for delivering course materials, assign- ments, and grades. Because the course is largely procedural with some concep-

168

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

JournalzyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for Businesstual highlights, the World Wide Web offered an opportunity to enhance active learning through exploration. Students were encouraged to use the Internet as a resource for information not included in the course

material^.^

Daniel (1999) and Michelson and Smith (1999) reported that the Web can expand interactivity and adaptability. It easily can accommo- date a wide variety of learners: For example, it attracts both kinesthetic andvisual learners (Zanglein

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Stalcup,1999). Hence, we hypothesized that the World Wide Web would encourage greater participation and engagement from those not stimulated in a tradition-

al classroom.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Technology Implementation

We offered opportunities for students to learn the threaded discussion and Web technologies in the classroom. In the beginning of the semester, students attended a guest lecture describing and demonstrating the technologies. Stu- dents were encouraged to ask questions and participate, and the instructor was available to answer questions during traditional office hours and via electron-

ic mail.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

World Wide Web Page

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

A Web page was set up as a means of

information dissemination to supple- ment class time and other media. The Web page contained the detailed syl- labus for the semester, so students who had lost or misplaced it would have an

immediate, alternative source. The Web page also was used for general periodic announcements, reminders of exam dates, review dates, and so forth.

All quizzes and exams from earlier semesters are also posted on the Web, so all students have equal access to them. These are posted as hypertext markup pages, so they can be accessed through any type of personal computer or soft- ware. We feel that this aids students’ learning by giving them examples of questions to work on for themselves. To discourage students from just memoriz- ing the “right” answer to specific ques- tions, only the questions are provided. Posting questions on the Web requires that new questions be developed each

semester. This is not an enjoyable task, but the enhanced learning appears worth the cost.

Grades from quizzes and exams are also posted. The university provides each student with a randomly generated identification number. If the student gives his or her written permission to the instructor, the instructor posts the grades and sorts them by this unique student number, which ensures privacy of the information over the Web. Over 90% of students in our classes provide the written permission slips, suggesting that they value this information provi- sion tool. Researchers have emphasized the benefits of immediate feedback on learning. The posting of grades on the Web frequently allows students to receive feedback before the next class session, or before they can arrive at the one spot on campus where the grades are posted on a wall (Menges & Rando, 1996). In addition to benefiting the stu- dent and the learning process, the post- ing of grades benefits the instructor, who previously would be interrupted by frequent student visits during office hours for the checking of grades on par- ticular quizzes or exams.

Finally, the Web page has proved beneficial in calling attention to certain articles in the Wall Street Journal. On the Web page, the instructor provides links to specific articles in the Wall

Street Journal, so students who sub- scribe its interactive page have immedi- ate access to key articles from the Inter- net. Many students have remarked that they find this feature valuable, especial- ly in preparing for exams.

Threaded Discussions

The Web page also contains a link to threaded discussions for the class. Con- tributions to threaded discussions are voluntary. However, as an incentive, bonus points are awarded for meaning- ful contributions to the discussion. Each individual contribution is worth one bonus point added to the student’s final class average. Contributions can come in the form of questions or answers to other students’ questions. By allowing students to answer questions, the instructor is responsible for much less than the usual one half of classroom-

related discourse. The instructor needs only to confirm that students provide no serious misinformation, which has not occurred to any significant extent in ear- lier classes. Questions from students can pertain to the text, lecture, or the real world and the Wall Street Journal.

A maximum of five bonus points can be earned during the course of 1 semester, allowing one half of one letter grade improvement overall.

Threaded discussions allow for active and collaborative student learning. McKeachie (1997, p. 1219) saw evi- dence of “better student retention, thinking, and motivational effects when students are more actively involved in talking, writing, and doing.” Large class sizes are not generally conducive to active, collaborative learning, but threaded discussions technology en- ables them to experience it.

Contributions to Threaded Discussions and the Learning Process

The technologies described were used in the PMBC course in spring 1999 and spring 2000. Student feedback has been generally quite favorable. Students like the fact that scores are posted quickly, that links to Wall Street Journal articles are provided, and that bonus points can be earned by making contri- butions to threaded discussions.6

There was some initial concern about the bonus point system used to reward contributions to threaded discussions. We felt that some students, interested only in their grade, might try to take advantage of the bonus points and post less-than-significant comments or ques- tions. To overcome this problem, the syllabus clearly states: “The instructor will decide whether a question, or reply, is worthy of a bonus point. To be worthy of a bonus point a listing must be post- ed properly and posted only once. Moreover, the question, or reply, must be (1) clearly written; (2) complete; (3)

relevant to the course discussion; and

(4) the product of a desire to learn. In

addition, a reply must be correct and to the point of the question.” Though this has added to the workload of the instructor, it requires only about 1 hour a week to keep up with this task.

Even with this warning we were con-

January/February 2001 169

cemed that students, in optimizing their scoredeffort tradeoff, might slack off if they had significant bonus points award- ed. On the other hand, we knew that if students learned from their efforts in contributing to threaded discussions, they might deserve better grades overall. To assess which of these two situa- tions dominated, we calculated simple correlation coefficients for the correla- tion between the number of bonus points awarded to a particular student and the scores he or she made on quizzes or exams. In Table 1, we pro- vide the correlation coefficients and

their

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

t statistics for both semesters inwhich the technology was employed. In all cases, the correlation coefficients were positive, indicating that those stu- dents with the most bonus points also

did the best on quizzes and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

exams. Thet statistics also allow us generally to reject the hypothesis that these esti- mates are not different from zero, at tra- ditional levels of significance.

Of course, correlation does not imply causality. It could be the case that the

brightest students are the ones most comfortable with this new technology. Still, this evidence is suggestive that learning might take place via threaded discussions.

To further assess the impact of threaded discussions on the teaching of

PMCB, we undertook an informal sur-

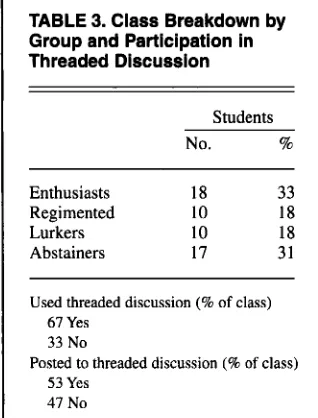

rvey of students at the end of a summer session in 1999. A survey analysis showed that the students could be logi- cally grouped into four categories based on their responses to three questions about the threaded discussions. The first question asked whether the student posted to the threaded discussion; the second asked whether he or she read it; and the last question prompted the stu- dents for recommendations and sugges- tions. We classified the students into one of four groups based on their accounts (see Table 2). In Table 3, we

provide the percentages for each group, the number of students who used threaded discussions by going to the Web site, and the number who actually

In the appendix, we delineate some of the specific positive and negative com- ments by group. In general, a majority of the students used the threaded discus- sion either actively (posting and read- ing) or passively (reading), and a major- ity found the discussion useful in their learning process. The abstainers noted a few obstacles that will be addressed in future curriculum design. For instance, many students commented that they were unsure of the correctness of peer responses. In the future, students will be reassured at the beginning of the semes- ter that the professor is monitoring the discussion and will correct any false or misleading responses. The survey also indicates that further quantitative data are needed to more thoroughly analyze the extent of student participation and learning. Still, we are encouraged by the survey results. The threaded discussion technology is not for everyone. Not all students will use it. But, in this day of larger classrooms and stretched resources, being able to reach a larger

posted comments. number of students is very beneficial.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

TABLE 1. Correlation Coefficients for Student Bonus Points and Other Specific Student Scores Correlation between bonus points on threaded discussion and

Semester of Quiz average Exam 1 score Exam 2 score Exam 3 score Final exam score

threaded discussion use

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(p value) (p value) (p value) (p value) (p value)Spring 1999

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(n = 61) 0.151 0.201 0.207 NA 0.251 (0.057) (0.0 10) (0.008) (0.001)Spring 2000 (n = 151) 0.190 0.225 0.236 0.317 0.247 (0.004) (0.0006) (0.0003) (0.00004) (0 BOOS)

Note. NA indicates that exam no. 3 scores were not available this semester, as only two in-class exams were given.

TABLE 2. Classification of Students Into Four Groups, Based on Responses to Three Questions Regimented group

based on a perceived

(participated reluctantly Abstainers (did not participate Enthusiasts extra credit points, Lurkers negative attitudes

necessity, such as and described Survey question (participated eagerly) professor expectations) (only read the discussion) about the discussion) Did you post to the

Did you read the threaded Please offer suggestions

threaded discussion? Yes discussion? Yes and recommendations. Positive

Yes Yes Negative

No

Yes Positive

No

No

Negative

170 Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Education for BusinessTABLE 3. Class Breakdown by Group and Participation in

Threaded Discussion

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Students

No.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

%Enthusiasts 18 33

Regimented 10 18

Lurkers 10 18

Abstainers

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

17 31Used threaded discussion (% of class)

67 Yes

33 No

53 Yes

47 No

Posted to threaded discussion (% of class)

One word of caution on our survey findings is appropriate. This survey was undertaken during a summer session, in

which classes meet every day over a

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5-week period. This is a much more con- densed time frame than the regular full semester, and the difference might have reduced the value of threaded discus- sions. Follow-up research is planned to assess the importance of this dimension of the classroom setting and the value of threaded discussions.

Conclusions and Future Directions

In this article, we have attempted to convey the theoretical and qualitative application of certain technologies and instructional approaches to an under- graduate finance course. Given the instructors’ observations, the student feedback, and the improved grades from those involved, we are convinced that the technology enhances the teaching and learning process.

We plan to continue to evaluate the technology effectiveness by using stu- dent evaluations, student performance on quizzes and examinations, and instructor evaluations. In addition, we will measure student participation using Web server statistical software. We will be able to measure the Web page activi- ty as well as the duration of each visit to the Web site.

For evaluation of the threaded discus- sion participation, each message posted to the discussion is recorded. We will

collect the messages and analyze the posting frequency of each student as well as do a qualitative analysis of each posting. The qualitative analysis will allow us to distinguish high-quality input (awarded course points) from poor-quality input (not awarded course points). We will evaluate how well the technology engages the students as well as student performance.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We wish to thank Dr. Larry Austin, Mark Swanstrom, and an anonymous referee for helpful comments on this article.

NOTES

1. The syllabus for spring 2000, or earlier, is available from the authors upon request.

2. Symbolic course content teaches a basic understanding and description of a topic or process. For instance, students learn about the banking institutional structures and learn to iden- tify each entity and its role in the larger system. Students also learn fundamental precepts and def- initions throughout the course. Procedural course information teaches learning objectives founded in mastering skills and processes. In PMBC, stu- dents learn basic mathematical calculations such as present value and interest rate determination. The conceptual course information asks the stu- dent to learn about a topic or process, and to relate it to other discipline topics and concepts. When students learn about the monetary structures and policies, the instructor often will encourage the students to apply general economic theory to determine the role of monetary policy and theory in a democratic society.

3. Linear and nonlinear schemata refer to the manner in which learning objectives and activities are organized and presented to students. Linear instructional methodologies afford students a structured and guided learning path through the course objective and outcomes (Spiro & Jehng,

1990). A nonlinear schema suggests that the order in which the student masters the learning objec- tives will not inherently affect the learning out- comes.

4. Microsoft’s FrontPage has a wizard that allows threaded discussions to be set up in a mat- ter of minutes.

5. As a starting place, the instructor provides

links to specific articles in the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Interactive WallStreet Journal.

6. For individuals interested in seeing the con- tributions to threaded discussions over these 2

semesters, please contact one of the authors.

REFERENCES

Althaus, S. L. (1997). Computer-mediated com- munication in the university classroom: An experiment with on-line discussions. Communi-

cation Education, 46(7), 158-174.

Bloom, B. S. (Ed.). (1956). Taxonomy of educa-

tional objectives: The class$cation

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of educa-tional goals by a committee of college and uni-

versity examiners. New York: David McKay.

Brandon, D. P., & Hollingshead, A. B. (1999).

Collaborative learning and computer-supported groups. Communication Education, 48(4),

109-126.

Daniel, J. (1999). Computer-aided instruction on the World Wide Web: The third generation.

Journal of Economic Education, Spring, pp.

Glaser, R., & Bassok, M. (1989). Learning theory and the study of instruction. Annual Review of

Psychology, 40, pp. 631-666.

Hillman, D. C., Willis, D. J., & Gunawardena, C. N. (1994). Learner-interface interaction in dis- tance education: An extension of contemporary models and strategies for practitioners. The

American Journal of Distance Education, 8(2),

3 M 2 .

Johnson, D. W., Johnson, R. T., & Smith, K. A.

(1991). Cooperative learning: Increasing col-

lege faculty instructional productivity (ASHE-

ERIC Higher Education Report No. 4). Wash- ington, DC: The George Washington University School of Education and Human Development. (ERIC document reproduction service no. ED

343 465)

King, K. M. (1994). Leading classroom discus- sions: Using computers for a new approach.

Teaching Sociology, 22, pp. 174-182.

Kulik, C. C., & Kulik, J. A. (1986). Effectiveness of computer-based education in colleges. AEDS

Journal, 19(Winter/Spring), 8 1-108.

McKeachie, W. (1997). Student ratings: The valid- ity of use. American Psychologist, 52( 1 I ) ,

12 18-1 225.

Menges, R., & Rando, W. (1996). Feedback for enhanced teaching and learning. In R. Menges & M. Weimer (Eds.), Teaching on solid ground:

Using scholarship to improve practice (pp.

233-255). San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Michelson, S., & Smith, S. D. (1999). Applica-

tions of WWW technology in teaching finance.

Financial Services Review, 8, 319-328.

Mishkin, F. S. (1998). The economics of money,

banking, andjnancial markets (5” ed.). Read-

ing, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Mishkin, F. S., & Eakins, S. G . (2000). Financial

markets and institutions (3d ed.). Reading. MA:

Addison Wesley Longman.

O’Donnell, A. M., & O’Kelly, J. (1994). Learning from peers: Beyond the rhetoric of positive results. Educational Psychology Review, 6, pp.

321-349.

Olaniran, B. A., Savage, G. T., & Sorenson, R. L.

(1996). Experimental and experiential approaches to teaching face-to-face and com- puter-mediated group discussion. Communica- tion Education, 45(7), 244-259.

Shute,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

V. J. (1995). SMART Student modelingapproach for responsive tutoring. User model-

ing and user-adapter interaction, 5, pp. 1-44.

Slavin, R. E. (1991). Synthesis of research on cooperative learning. Educational Leadership,

Smith, R., & Stalcup, K. A. (2001, forthcoming). Technology consulting: Keeping pedagogy in the forefront. In Face-to-Face (2nd ed.). Stillwa- ter, OK: New Forums Press.

Spiro, R. J., & Jehng, J-C. (1990). Cognitive flex- ibility and hypertext: Theory and technology for the nonlinear and multidimensional traver- sal of complex subject matter. In D. Nix & R. Spiro (Eds.), Cognition, education, and multi-

media: Exploring ideas in high technology (pp.

163-205). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Zack, M. H. (1995). Using electronic messaging to improve the quality of instruction. Journal of

Education for Business, 70, pp. 202-206.

Zanglein, J., & Stalcup, K. (1999). Te(a)chnology: Web-based instruction in legal skills courses.

Journal of Legal Education, 49(4), 1-24.

163-1 74.

48, pp. 71-82.

Junuary/Februury 2001

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

171 [image:6.612.45.204.47.256.2]APPENDIX

1999 STUDENT SURVEY STATEMENTS

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Enthusiasts’ Comments

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I think they’re [threaded discussions] the only thing saving my grade. It also helped to learn because I’d have to research an answer.”

“Very helpful.”

“Good study tool.”

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

“I felt it was a great way to learn and“Some questions were very hard to

‘‘I was impressed that my classmates

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

“. .

.I learned more by posting answers “It makes you think.”“. . .

I learned a lot of things that we interact with the students.”answer, but it was a good learning tool.” could answer some of the questions.” than I did posting questions.”

wouldn’t have been discussed in class.”

Disciplined Group’s Comments

“Fair. If more students used it, it would be more effective.”

“I think the threaded discussions were made to be intimidating in a way they shouldn’t be. I think some people are timid and their questions would not be worthy.”

“People like to dream up really hard ques- tions that sound good.”

“.

.

.not accessible to all students.” “Explain better how to post questions in order to get points.”“Some of my questions did not get answered.”

“I never got a response on my question so I stopped paying attention.”

“. .

.sometimes I wonder if the answer you get from another classmate is correct-they are at the same level as you are.”Lurkers’ Comments

“I thought it was neat. I never posted any- thing but I checked it almost everyday.”

“I only had a chance to read them a few times.”

“I only read the discussion. I wondered if the replies from students were accurate- should I take it as fact.”

‘‘I read two and quit.

. .

.too time con- suming.”Abstainers’ Comments

“Get rid of it [threaded discussion].” “Never looked at it.”

“I think it is an excellent tool for the stu- dents with a genuine interest in the course.” [Student never posted or read the discussion.] “It’s hard when you do not have a com- puter and work forty hours per week.”

172 Journal of Education for Business