Tectonics and sedimentation in a paleo

/

mesoproterozoic

rift-sag basin (Espinhac¸o basin, southeastern Brazil)

Marcelo A. Martins-Neto

Departamento de Geologia,Escola de Minas,Uni6ersidade Federal de Ouro Preto,Caixa Postal173, Campus Morro do Cruzeiro s/n,35400-000Ouro Preto,MG,Brazil

Received 2 June 1999; accepted 20 March 2000

Abstract

Sedimentologic, paleogeographic, stratigraphic, structural and tectonic studies in a paleo

/

mesoproterozoic

metased-imentary succession (Espinhac¸o Megasequence, southeastern Brazil) indicates deposition in a rift-sag basin. Four

basin evolution stages are recognized (prerift, rift, transitional and flexural). The four stages can be represented by six

unconformity-bounded tectonosequences. The unconformities are recognized in the field and mappable even on a

regional scale. The prerift and rift stages of the Espinhac¸o basin were filled by products of continental depositional

systems. The prerift stage probably represents the first product of the rifting process, before the development of the

half-grabens that characterize the rift stage. During the rift stage, mechanical subsidence due to lithospheric stretching

was predominant and led to episodic rising of the depositional base level. As a result, the basin fill is characterized

by coarsening-upward intervals. Paleocurrent patterns indicate that block tilting and half-graben subsidence

/

uplift

controlled sediment dispersion. The first marine incursion within the Espinhac¸o basin marks the change in the

subsidence regime of the basin. The evolution of the transitional and flexural stages was probably controlled by

thermal subsidence due to thermal contraction of the lithosphere during cooling. The transitional stage was

characterized by relatively low subsidence rates. Higher subsidence rates and a consequent sea-level rise characterize

the flexural stage of the Espinhac¸o basin, in which three second-order transgressive-progradational sequences can be

recognized. © 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:Brazil; Proterozoic; Tectonostratigraphic units; Basin analysis; Tectonics; Sedimentation

www.elsevier.com/locate/precamres

1. Introduction

Rift-sag basins represent the tectonic product of

aborted passive-margin development (Allen and

Allen, 1990). These basins, commonly referred to

as aulacogens or failed rifts, display a ‘steer’s

head’ geometry due to early rifting and

sub-sequent thermally-driven downwarping (White

and McKenzie, 1988). The stratigraphic

frame-work, structural style, and tectonic evolution of

rift-sag basins have been interpreted mainly

through seismic reflection profiles (e.g. Meyerhoff,

1982; Schlee and Hinz, 1987; Badley et al., 1988).

With exceptions (e.g. Eriksson et al., 1993), few

E-mail address:[email protected] (M.A. Martins-Neto).examples based on direct field observations have

been published.

Deposits of the paleo

/

mesoproterozoic

Espin-hac¸o basin outcrop in the central and western parts

of the Serra do Espinhac¸o, southeastern Brazil

(Fig. 1). Because of inversion during the

neo-proterozoic (Brasiliano

/

Pan African orogeny), and

because of a deep erosional level, the Espinhac¸o

basin provides an opportunity to evaluate the

paleogeographic and tectonic evolution of a rift-sag

basin

through

outcrop

data.

Of

particular

importance, deposits recording initial rifting are

exposed. These constitute a valuable source of data

to characterize the three-dimensional architecture

of an early half-graben, and to document the

relationships between tectonics and sedimentation

that might not be available through geophysical

studies alone.

This

paper

presents

a

model

for

the

tectono-sedimentary evolution of the Espinhac¸o

rift-sag basin, based on geological mapping and

integrated

sedimentologic,

paleogeographic,

stratigraphic, structural and tectonic studies,

carried out in the central and western parts of the

southern Serra do Espinhac¸o, Brazil (Fig. 1). Early

workers (e.g. Pflug, 1965) described the Espinhac¸o

supergroup

as

a

miogeosynclinal

sequence.

Subsequently, a rift to passive-margin setting was

proposed (Pflug et al., 1980), and Martins-Neto

(1993), Schobbenhaus (1993), Dussin and Dussin

(1995) suggested, based on the ensialic setting and

stratigraphic

framework,

deposition

in

an

intracratonic basin, with an initial rift phase and a

subsequent flexural phase. The present paper

provides detail documenting the prerift, rift,

transitional and flexural stages of basin evolution.

2. Regional setting

The southern Serra do Espinhac¸o belongs to the

external zone of the Arac¸uaı´ fold-thrust belt,

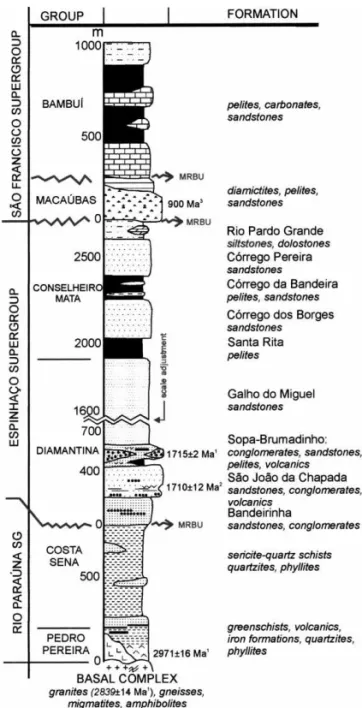

Fig. 2. Lithostratigraphy of the southern Serra do Espinhac¸o after Pflug (1968), Fogac¸a et al. (1984), Dossin et al. (1984), Almeida Abreu and Pflug (1992) (modified after Martins-Neto, 1993). Geochronological ages are from (1) Machado et al. (1989), (2) Dussin and Dussin (1995) and (3) Buch-waldt et al. (1999). MRBU, major regional bounding uncon-formity.

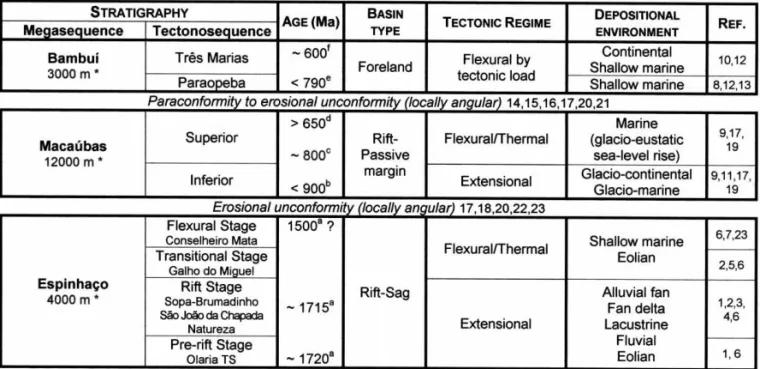

Fig. 3. Stratigraphic framework and tectono-depositional features of the paleo/meso and neoproterozoic cover sequences of the Sa˜o Francisco craton and external zone of the Arac¸uaı´ fold belt.

along the southeastern margin of the

neo-proterozoic Sa˜o Francisco craton, southeastern

Brazil (Fig. 1; Brito Neves and Cordani, 1991;

Trompette et al., 1992; Schobbenhaus, 1993;

Alkmim et al., 1993; Martins-Neto, 1998a). The

paleo

/

mesoproterozoic Espinhac¸o supergroup (Fig.

2) is the predominant unit in the southern Serra do

Espinhac¸o,

overlying

the

archean

basement

complex and supracrustal rocks of the archean

/

paleoproterozoic Rio Parau´na supergroup

uncon-formably (Pflug, 1965). It is in turn unconuncon-formably

overlain by the neoproterozoic Sa˜o Francisco

supergroup (Fig. 2; Pflug and Renger, 1973;

Dupont, 1996; Martins-Neto et al., 1997a,b, 1999a).

The maximum age of the Espinhac¸o supergroup

is limited by U

/

Pb dating of metamorphic zircon

in pre-Espinhac¸o units (1844

9

15 Ma; Machado et

al., 1989), and depositional ages from magmatic

zircons in volcanic-bearing units in the lower parts

of the Espinhac¸o supergroup include, (1) 1711 Ma

(U

/

Pb;

N.

Machado

oral

commun.,

1993;

in

Schobbenhaus,

1993);

(2)

1710

9

12

Ma

(

207Pb

/

206Pb; Dussin and Dussin, 1995); and

(3) 1715

9

2 Ma (U

/

Pb; Machado et al., 1989). The

minimum age of the Espinhac¸o supergroup is

less constrained, and is currently defined by basic

intrusions that cut the entire column (ca. 1.1 –

0.9 Ga; Brito Neves et al., 1979; Machado et al.,

1989).

The southern Serra do Espinhac¸o was deformed

and metamorphosed in the Brasiliano

/

Pan African

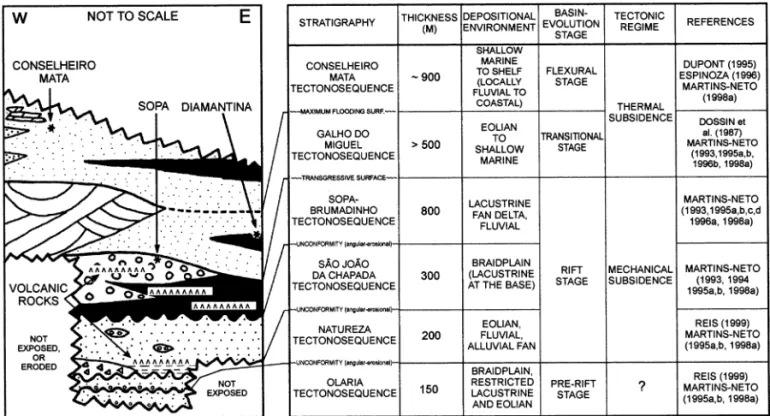

Fig. 4. Stratigraphic chart for the Espinhac¸o Megasequence showing the main characteristics of the tectono-sedimentary units (modified from Martins-Neto, 1995a).

3. Stratigraphic framework

The Espinhac¸o supergroup is a thick (

4000

m) succession of siliciclastic metasedimentary

rocks containing subordinate volcanic intervals

(Fig. 2). These have been grouped

lithostratigraph-ically into nine formations (Pflug, 1968; Almeida

Abreu and Pflug, 1992). Herein, adopting a genetic

stratigraphic approach, the Espinhac¸o supergroup

is referred to as the ‘Espinhac¸o Megasequence’,

which is the record of an unconformity-bounded,

single basin-fill cycle. The basin-fill cycle is

com-posed of six tectonosequences, from bottom to top

(Figs. 3 and 4), the Olaria tectonosequence (prerift

stage), the Natureza, Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada and

Sopa-Brumadinho tectonosequences (rift stage);

the Galho do Miguel tectonosequence (transitional

stage) and the Conselheiro Mata tectonosequence

(flexural stage). Each tectonosequence records

linked depositional systems accumulated in a

spe-cific tectonic phase of the basin, and is defined by

major regional bounding unconformities (Fig. 4;

Da Silva, 1993; Martins-Neto, 1995a,b). These

unconformities represent periods of significant

tec-tonically induced paleogeographic reorganization.

During the rift stage, mechanical subsidence due to

lithospheric stretching controlled basin evolution.

The transitional and flexural stages were

trolled by thermal subsidence arising from

con-traction of the lithosphere due to cooling.

The genetic stratigraphic approach adopted

herein is based on the definition of a major

uncon-formity-bounded megasequence, allowing

recogni-tion and analysis of a true basin entity, even

though its life span is not well constrained. Each

tectonosequence represents the record of an

evolu-tionary stage of the basin, with its own

accommo-dation history. Contacts are recognized in the field

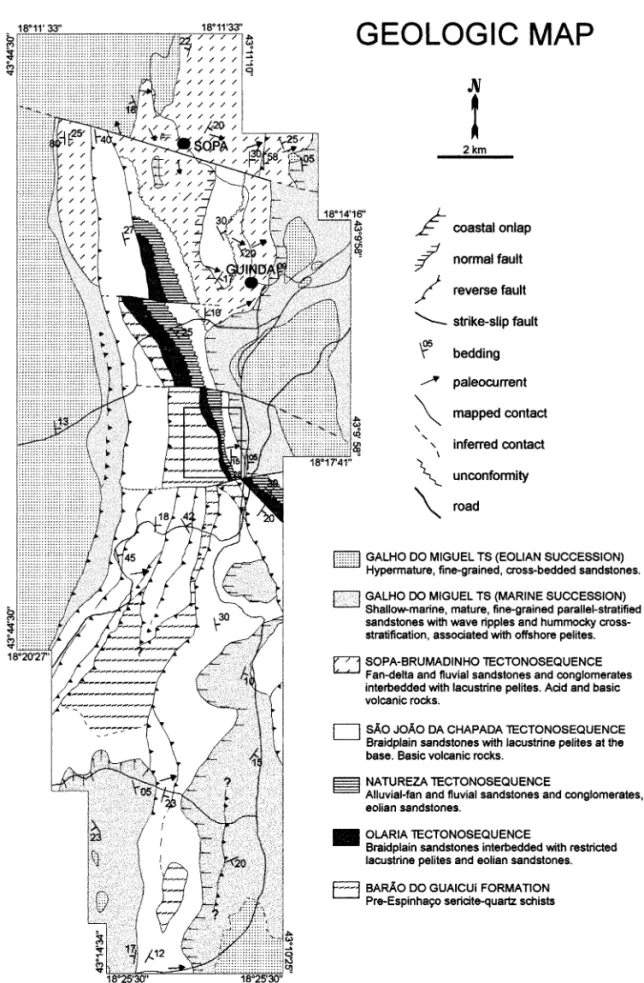

and mappable even on a regional scale (Fig. 5).

4. Prerift stage: Olaria tectonosequence

Fig. 6. Photograph showing sheet-flood sandstones of the Olaria braidplain deposits. Note hammer (circled) for scale.

terpretations are limited by poor outcrop and

high strain, the lack of volcanic rocks and of

evidence of synsedimentary faults (in contrast to

overlying sequences) suggest that the Olaria

tec-tonosequence was deposited in an initial sag that

was the product of ductile stretching, before the

upper crust had reached its elastic limit.

How-ever, clastic dykes filled by conglomeratic

sand-stones

occur

at

the

top

of

the

Olaria

tectonosequence. These are truncated at the

an-gular unconformity with the overlying Natureza

tectonosequence, and are likely precursors of

ac-tive shallow-level faulting.

5. Rift stage: Natureza; Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada;

Sopa-Brumadinho tectonosequences

The rift stage of the Espinhac¸o basin is

charac-terized by three phases all of which are bounded

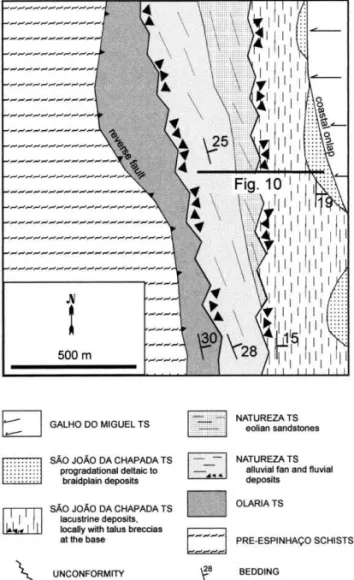

by angular unconformities (Figs. 4, 5 and 7),

synrift 1 (Natureza tectonosequence); synrift 2

(Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada tectonosequence); and

synrift 3 (Sopa-Brumadinho tectonosequence).

5.1.

Synrift

1

phase

(

Natureza tectonosequence

)

The Natureza tectonosequence is up to 200 m

thick (cf. Reis, 1999). Massive and inversely

graded clast-supported conglomerates interpreted

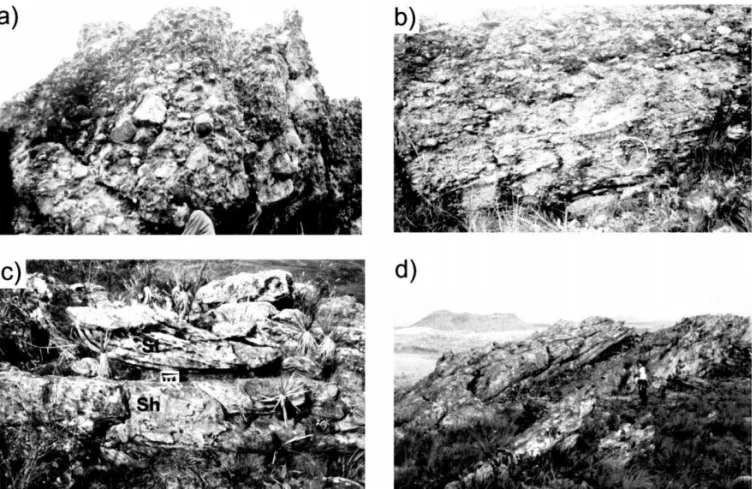

as debris-flow deposits (Fig. 8a) occur above the

mudstones (sericitic phyllites). The deposits are

likely high-energy ephemeral flood deposits

simi-lar to those described by Tunbridge (1981, 1984).

Some lenticular bodies composed of fine-grained

sandstones with high textural maturity occur in

the middle portion of the unit (Reis, 1999). These

display large-scale cross-stratification (sets up to

3 m thick) with high-angle (30 – 35°) truncations

may be suggestive of an eolian origin. Thick

layers of sericitic phyllites, which may represent

deposition in ponds, occur locally.

The available data (Table 1) suggest that the

Olaria tectonosequence was probably deposited

in alluvial braidplains associated with restricted

lacustrine and eolian environments. Although

in-Table 1

Summary of the depositional characteristics of the Olaria tectonosequence

Depositional Key lithologies Sedimentary features Depositional process

setting

Sheet floods under upper flow Poorly-sorted, medium to

Alluvial Parallel-stratification, sheet like

braidplain fine-grained sandstones geometry regime

Poorly-sorted, medium to Trough cross-stratification 3D-dune migration (sensu Ashley,

fine-grained sandstones 1990) under lower flow regime

Planar cross-stratification

Poorly-sorted, medium to 2D-dune migration (sansu Ashley,

1990) under lower flow regime fine-grained sandstones

Fine-grained sandstones Ripple cross-lamination Current-ripple migration Floodplain deposits

Pelites Thin mud drapes

Vertical accretion

Pelites Metric thick bodies

Lacustrine

Eolian dune migration Metric thick cross-beds with

Eolian Hypermature fine-grained

basal angular unconformity. The debris-flow

conglomerates are associated with clast- and

matrix-supported stratified conglomerates

con-sidered as traction deposits (Fig. 8b) and are

interpreted as having been deposited in an alluvial

fan and braided stream depositional system. The

conglomeratic deposits are covered by a sandy

braided fluvial succession (Fig. 8c) interbedded

with eolian sandstones (Fig. 8d, Table 2) (Silva,

1995; Reis, 1999).

Conglomerate

sections

and

the

angular

character of the unconformity at the base of the

Natureza

tectonosequence

are

suggestive

of

tectonic influence such as block tilting or selective

uplift and

/

or subsidence. This signifies rupture of

the upper crust and the development of the first

half-grabens in the Espinhac¸o basin. The limited

areal extent of the Natureza tectonosequence

suggests a restricted character of the basin at this

time. The absence of volcanic rocks infers a

stretching factor

b

(White and McKenzie, 1988)

of less than 2 for this phase.

5.2.

Synrift

2

phase

: (

Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada

tectonosequence

)

The Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada tectonosequence is

up to 300 m thick. Locally, above the angular

unconformity (Fig. 9), conglomerates and breccias

contain abundant sandstone clasts derived from

the underlying Natureza tectonosequence. These

have been interpreted as fault-scarp talus deposits

formed by cohesionless mass-flows, and are strong

indicators of repeated local fault uplift and

canni-balization as part of the rifting process

(Martins-Neto, 1993).

The onset of volcanism in the evolution of the

Espinhac¸o basin is marked by basic rocks near the

base of the Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada

tectonose-quence (Hoppe and Otto, 1982; Uhlein, 1991;

Schobbenhaus, 1993; Dussin, 1994; Dussin and

Dussin, 1995). Layers of hematitic phyllites within

these units have been interpreted as volcanic beds

altered by Paleoproterozoic subaerial weathering

(lateritization) and subsequent metamorphism

(Knauer and Schrank, 1993).

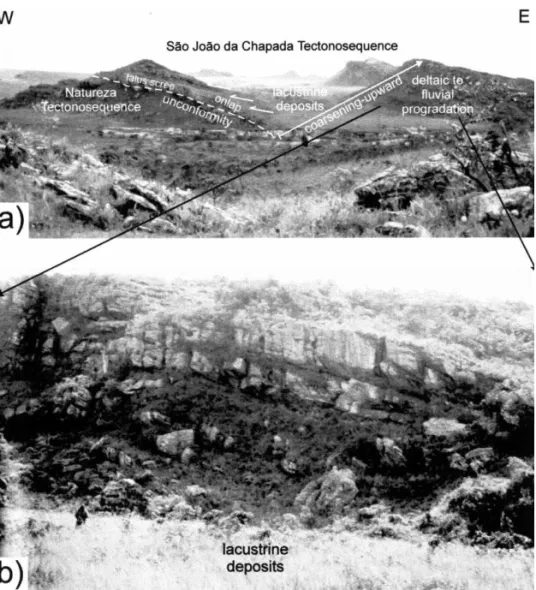

The Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada tectonosequence

defines an overall coarsening-upward succession

from lacustrine to deltaic to fluvial deposits (Fig.

10). Fine-grained sandstones and pelites at the

base, probably deposited in a storm-influenced

lacustrine environment, represent rapid

subsi-dence and abrupt basin deepening. These are

overlain by sandstone bodies of likely deltaic

origin that display a sigmoidal geometry and are

arranged in coarsening- and thickening-upward

sequences. Prograding over the deltaic

/

lacustrine

deposits are extensive braidplain sandstones that

Fig. 7. Geologic map showing the angular character, denotedFig. 8. Photographs showing deposits of the synrift 1 Natureza tectonosequence, (a) Debris-flow conglomerates. Note inverse grading in the body comprising the lower half of the outcrop; (b) stratified, sheet-flood conglomerates. Note hammer (circled) for scale; (c) horizontally stratified (Sh) and trough stratified sandstones (St) of braided fluvial origin; (d) metric-scale cross-stratified sandstones of eolian origin.

constitute ca. 80% of the Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada

tectonosequence. These signify relatively reduced

rates of subsidence (Martins-Neto, 1993, 1994).

The Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada braidplain deposits

(Table 3, Fig. 11a) are characterized by sheet-like

bodies of coarse and poorly-sorted sandstones

that display unidirectional paleocurrents with

re-markably little dispersion throughout the study

area (Fig. 11b). The sandstones generally define

fining- and thinning-upward sequences and are

invariably bounded by low-relief erosional

sur-faces (Martins-Neto, 1994). Typical sequences

start with parallel-stratified and low-angle

cross-stratified sandstones (Sh

/

Sl) and are capped by

trough cross-stratified sandstones (St) and locally,

mudstone layers, characteristic of high-energy

ephemeral streams (e.g. Miall and Gibling, 1978;

Tunbridge, 1981, 1984; Lawrence and Williams,

1987; Mun˜oz et al., 1992). As detailed elsewhere

(Martins-Neto, 1994), the superposition of such

waning-flood sheet sandstones built up a

braid-plain that extended ca. 35 km transverse to the

regional paleoslope (Fig. 12).

5.3.

Synrift

3

phase

(

Sopa

-

Brumadinho

tectonosequence

)

Table 2

Facies of the Natureza tectonosequence and interpretation

Facies Interpretation

Massive to inversely Debris flows graded, clast-supported

conglomerates

Parallel-stratified, Traction deposits matrix-supported

conglomerates

Parallel-stratified, Sheet floods under upper flow regime

poorly-sorted sandstones

Trough cross-stratified, Fluvial 3D-dune migration (sensu Ashley, 1990) under poorly sorted sandstones

lower flow regime Planar cross-stratified, Fluvial 2D-dune migration

poorly sorted sandstones (sensu Ashley, 1990) under lower flow regime Ripple cross-laminated Current-ripple migration

sandstones

Floodplain deposits Pelites

Eolian dune migration Hypermature fine-grained,

metric thick coss-bedded sandstones

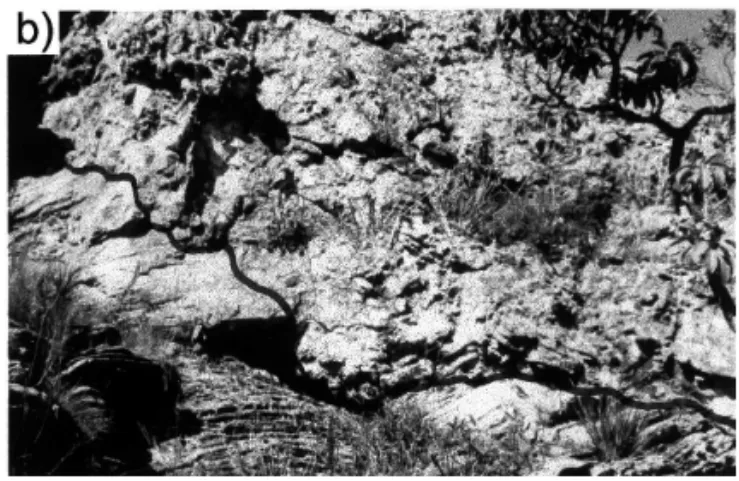

Fig. 9. Photographs showing (a) view of the angular unconfor-mity separating the Natureza and Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada tectonosequences and (b) detail emphasizing the erosional nature of this unconformity.

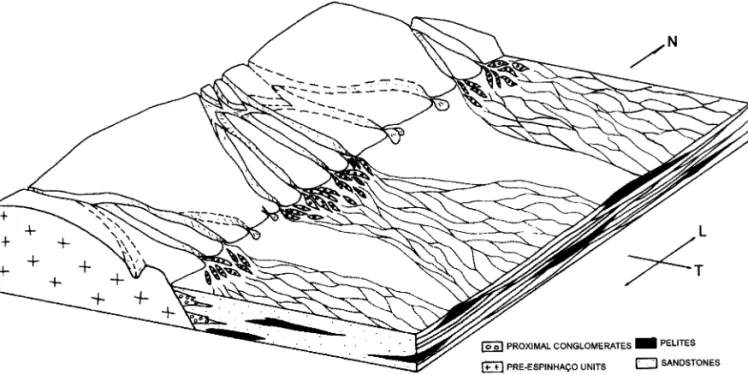

discussed in the following sub-headings,

lacus-trine, fan-delta and fluvial sedimentation took

place in half-grabens that were

compartmental-ized by north-trending normal faults and

east-trending transfer faults. Subsidence was episodic

and controlled by block tilting in asymmetric

grabens.

5.3.1.

Lacustrine

,

fan

-

delta and flu

6

ial deposits

The facies of the Sopa-Brumadinho

tectonose-quence are arranged in 40 – 80 m thick setectonose-quences

that coarsen and then fine upward (Fig. 13a and

b). At the base of each sequence are laminated

pelites (facies F). These are followed by, graded

and stratified sandstone beds (facies Sg); massive,

parallel-stratified, trough cross-stratified, and

pla-nar cross-stratified sandstones (facies Sm, Sh, St,

and Sp); and predominantly debris flow

conglom-eratic units (Table 4). The conglomerates then fine

upward to various sandstone facies (Fig. 13a).

Some sequences lack the lower turbiditic graded

sandstone component, and laminated mudstones

pass directly to stacked streamflood sandstones

(e.g. Fig. 13b). Mudlumps, formed by the rapid

loading of debris-flows onto water-saturated

muds (Dailly, 1976; Lewis, 1997) are locally

devel-oped. An approximately 200 m thick section of

parallel-stratified, trough cross-stratified and

pla-nar cross-stratified sandstones (

9

pelites)

inter-venes within the predominantly cyclic succession

(Reis, 1999; Martins-Neto et al., 1999b).

Table 4 summarizes the 13 facies of the

Sopa-Brumadinho tectonosequence and their

interpre-tation. More detailed descriptions of these facies

and the sedimentary processes that generated

them can be found in Martins-Neto (1995d,

1996b).

Fig. 10. (a) Outcrop section (see Fig. 7 for location) showing the overall coarsening-upward arrangement from lacustrine to deltaic to fluvial deposits of the Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada tectonosequence; (b) detail showing the thickening-upward arrangement of the initial deltaic progradation.

Table 3

Facies of the Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada braidplain deposits (codes modified after Miall, 1978)

Code Characteristics Interpretation

Massive to parallel-stratified conglomerates

Gm Migration of longitudinal bars

Sh/Sl Parallel-stratified to low-angle (B10°) cross-stratified Sheet floods under upper flow regime sandstones

Trough cross-stratified sandstones

St 3D-dune migration (sensu Ashley, 1990) under lower

flow regime Planar cross-stratified sandstones

Sp 2D-dune migration (sensu Ashley, 1990) under lower

flow regime

Current-ripple migration Sr Ripple cross-laminated sandstones

Floodplain deposits

Fig. 11. (a) Measured sedimentological sections of the Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada braidplain deposits. Geological map modified from Scho¨ll and Fogac¸a (1981), Chaves et al. (1985). (b) Paleocurrent data from Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada braidplain (316 measurements from cross-stratified sandstones). Modified after Martins-Neto (1993).

sequences are interpreted to represent repeated

episodes of rapid flooding (basal laminated mud

units) followed by progradation of fan lobes

which evolved from distal (subaqueous) to

proxi-mal (subaerial) environments. The fining-upward

parts represent the abandonment phases of the

depositional lobes. Discriminating between

lacus-trine and shallow marine deposits is commonly

difficult in Precambrian strata (e.g. Eriksson et

al., 1998). A lacustrine origin is favored in the

present example because pelitic rocks of facies F

define a number of isolated N – S elongate lenses.

5.3.2.

Tectonically

-

dri

6

en cyclicity

The lacustrine, fan-delta and fluvial

coarsening-upward and fining-coarsening-upward sequences are

consid-ered to represent repeated tectonically-driven

pulses (see e.g. Blair and Bilodeau, 1988).

Accord-ingly, flood surfaces and pelitic rocks at the base

of each sequence are the immediate response to

fault-induced subsidence of the basin floor, and

subsequent fan-delta progradation records a

de-layed response, reflecting erosional stripping of

relatively uplifted source areas. Fining-upward

trends at the top of the sequences signify a

reduc-tion in source-area relief during continued

tec-tonic quiescence.

Fig. 13b) may imply shallower lakes.

Smaller-scale pulses may be recorded by thin pelite layers

interbedded with some of the sandstones near the

base of the sequences (Fig. 13a and b and Fig.

14a). Although post-depositional processes have

strongly modified the original thicknesses of these

layers, thickness variation suggests varying

subsi-dence pulse magnitudes.

5.3.3.

Half

-

graben geometry

In regional cross section, fan development is

asymmetric. In the west, diamond mining

opera-tions have exposed the spatial and angular

rela-tionships between two fan-deltas (Fig. 14a). The

younger lobe (Lavrinha mine) forms a wedge

positioned basinward of an older fan segment

(Diamante Vermelho mine). Correction for

tec-tonic tilt using marine deposits of the overlying

Galho do Miguel tectonosequence as a

paleohori-zontal datum, yields a primary dip of ca.10 – 15°

for the older fan segment and ca. 5 – 10° for the

younger fan. These results are compatible with

published data of recent fan slopes (cf. Wells,

1984; Blair and McPherson, 1994). Basinward

stepping and increasing angle of tilt with age

(reflecting progressive rotation due to faulting) is

characteristic of many fans, modern and ancient

(e.g. Hooke, 1972; Steel et al., 1977; Heward,

1978a,b; Kleinspehn et al., 1984; Blair, 1987). In

contrast to these basinward stepping lobes, to the

northeast, at the Brumadinho mine (Fig. 14b),

clast-supported talus breccias form vertically

stacked linear bodies in direct fault contact with

older rocks. The two types of fans (Fig. 15) as

well as the geologic map and the cross-section

A – A

%

in Fig. 16 indicate an asymmetric-graben

geometry, with the Diamante Vermelho

/

Lavrinha

system representing hanging-wall sourced fans at

the unfaulted ramping margin, and the

Brumad-inho fans marking footwall sourced fans at the

faulted border (cf. Hooke, 1972; Gawthorpe and

Colella, 1990).

5.3.4.

Synsedimentary faults

East-trending transfer faults can be recognized

(Figs. 5 and 16). Paleocurrent patterns illustrate

the control exerted by transfer faults and

fault-bounded blocks on sediment dispersal (Fig. 16).

North of an east-trending transfer fault located

Table 4

Facies of the Sopa-Brumadinho tectonosequence (conglomer-ate codes after Martins-Neto, 1993, 1996b; sandstone codes after Miall, 1978)

Code Characteristics Interpretation Ungraded

UG-CS Cohesionless debria

clast-supported flows conglomerates

Inversely graded Cohesionless debris IG-CS

clast-supported flows conglomerates

Normally graded

NG-CS Cohesionless debris

flows clast-supporte

conglomerates

Crudely stratified Hyperconcentrated CS-CS

clast-supported flows conglomerates

TB-CS Talus-breccia Fault-adjacent talus clast-supported breccias

conglomerates Sand matrix-supported

S-MS Cohesionless debris

flows conglomerates

Mud matrix-supported Cohesive debris flows M-MS

conglomerates

Sm Massive sandstones Hyperconcentrated flows

Parallel-stratified

Sh Sheet floods under

upper flow regime sandstones

Trough cross-stratified

St 3D-dune migration

sandstones (sensu Ashley, 1990) under lower flow regime

Sp Planar cross-stratified 2D-dune migration sandstones (sensu Ashley, 1990)

under lower flow regime

Graded-stratified

Sg Turbidity currents

sandstones

F Pelites Vertically accreted

lacustrine deposits

Chapada, Natureza, and Olaria tectonosequences

(section A – A

%

, Fig. 16).

Several minor north-trending normal faults are

preserved in the Sopa-Brumadinho deposits. These

structures do not cut overlying beds,

demonstrat-ing that they formed as synsedimentary growth

faults (Fig. 17). East-trending ‘release faults’

(De-stro, 1995) are normal faults that terminate

against, and accommodate differential

displace-ment along, the north-trending structures (Fig. 18).

5.3.5.

Bimodal

6

olcanic rocks

Mafic and felsic volcanic rocks form local

in-terbeds in the Sopa-Brumadinho tectonosequence.

The rhyolites and their intrusive counterparts

(Borrachudos Suite) display a metaluminous to

subalkalic character and are enriched in K, Fe, Nb,

Y, Zr, Ga and light REE (Dussin, 1994; Dussin

and Dussin, 1995). According to Dussin and

Dussin (1995), the geochemical data and isotopic

compositions of Nd (

oNd1730 Ma

between

−

10.1 and

−

6.2) and of Sr (

87Sr

/

86Sr

i

=

0.7057) indicate

par-tial melting of crustal sources, typical of

continen-tal rift settings.

6. Transitional stage: Galho do Miguel

tectonosequence

The first marine incursion within the Espinhac¸o

Basin, represented by deposits of the Galho do

Miguel tectonosequence, marks the beginning of

the transitional stage (Martins-Neto, 1993). A

regionally mappable transgressive surface

sepa-rates these deposits from the underlying rift

succes-sion (Figs. 5, 14, 16 and 19). The Galho do Miguel

tectonosequence contains basal shallow-marine

de-posits that onlapped underlying units from the

east, and extensive eolian sand sheets that

pro-graded from the west (Table 5).

Wave and storm-dominated siliciclastic shelf

deposits define a lower transgressive succession

and an upper progradational succession (Table 5,

Fig. 20a). Paleocurrent data (Fig. 20b) and facies

distribution suggest a north-trending shoreline

and east-dipping paleoslope. In the transgressive

succession, shoreface, transition-zone and

off-shore deposits can be recognized. In the

prograda-south of Sopa, paleocurrents are easterly, roughly

tional succession, a complete offshore to coastal

suite of facies is developed (offshore, transition

zone, lower shoreface, upper shoreface, beach,

eolian). In contrast to underlying units, overall

rates of sediment supply were low relative to rates

of subsidence and

/

or sea-level rise. The initial

transgressive succession probably reflects an

inad-equate sediment supply compared with the rate of

relative sea-level rise, whereas the progradational

succession probably resulted from sediment

sup-ply exceeding relative sea-level rise.

The paleogeography of the Galho do Miguel

tectonosequence was strongly controlled by the

final disposition of earlier rift stages. This is

illus-trated by the distribution of eolian deposits (Figs.

5 and 21). Above synrift 3 (Sopa-Brumadinho

tectonosequence) depocenters, the dune fields

pro-graded eastward, whereas above structural highs

eolian deposits are thin or absent, and eolian

dunes did not reach the eastern parts of the

Espinhac¸o range.

The Galho do Miguel tectonosequence marks

the change from predominantly mechanical,

lo-cally compensated subsidence to thermal,

region-ally compensated subsidence. This transitional

stage was characterized by relatively low

subsi-dence rates by comparison to the previous and

subsequent stages. The resultant decrease in

ac-commodation space caused enlargement of the

basin, as the sediment supply was maintained. In

addition, increased flexural rigidity due to

litho-spheric cooling likely favored basin widening.

7. Flexural stage: Conselheiro Mata

tectonosequence

The deposits of the flexural stage of the

Espin-hac¸o basin belong to the ca. 900 m thick

Fig. 15. Sketch showing the spatial relationship between depositional lobes in half-grabens, (a) progradational relationship between hanging-wall-derived fans at the flexural border (see Fig. 14a and section AA% on Fig. 16) and (b) aggradational relationship (vertically stacked) between footwall-derived fans at the fault border (see Fig. 14b and section AA%on Fig. 16) (modified from Heward, 1978b).

heiro Mata tectonosequence. The base of this unit

is defined by a maximum flooding surface, which

marks the greatest expansion of the Espinhac¸o sea

(Martins-Neto, 1995b; Espinoza, 1996). Locally,

the lower boundary is defined by multiple

shoal-ing-upward sequences 10 – 20 m thick (Fig. 22;

Espinoza, 1996).

According to Dupont (1995), three depositional

sequences with a transgressive base and a

progra-dational top can be recognized in the Conselheiro

Mata tectonosequence (Fig. 23). The first

se-quence (250 – 400 m thick) contains transgressive

barred nearshore deposits and progradational

beach to shallow-marine deposits (Dupont, 1995;

Espinoza, 1996). The second sequence (250 – 350

m thick) comprises transgressive shelf deposits

overlain by progradational alluvial plain to

coastal successions (Dupont, 1995). The third

se-quence (200 – 300 m thick) is defined by

transgres-sive mixed siliciclastic – carbonate shelf deposits

overlain by coastal to fluvial sediments (Batista et

al., 1986; Dupont, 1995). The top of the third

depositional sequence marks the final filling up of

the Espinhac¸o basin. The thicknesses (ca. 300 m)

and the estimated time (some 10 million years) for

deposition of each sequence suggest that they may

represent

tectonically

controlled

second-order

product of variations in the in-plane stress field

(Martins-Neto, 1998a).

8. Discussion

Some aspects regarding the evolution of the

Espinhac¸o basin remain uncertain. One

impor-tant question concerns the larger-scale structure

of the rift stage. The dimensions of the

half-grabens described above indicate that they are

relatively minor structures, and evidence of

link-age to a master fault is lacking. However, the

predominance of eastward-directed paleocurrents

in deposits related to lateral-transport systems

(Leeder and Gawthorpe, 1987) may indicate a

master fault located to the east, outside the study

area (see Martins-Neto, 1994, 1996b). Thick

con-glomeratic successions in the eastern domains of

the Espinhac¸o range may be related to such a

Fig. 18. East-trending synsedimentary ‘release faults’ (Destro, 1995), which terminate against the north-trending normal fault of Fig. 17.

Fig. 17. Photograph and sketch showing minor north-trending synsedimentary normal fault preserved in the Sopa-Brumad-inho deposits. The fault controlled the site of conglomerate deposition. Photograph taken in the Diamante Vermelho dia-mond mine (see Fig. 14 for location of the mine).

master fault, but full documentation is inhibited

by intense Brasiliano

/

Pan African deformation.

Fig. 19. Outcrop section and interpretation sketch showing transgressive surface separating lacustrine pelites and a small deltaic lobe of the rift stage from shallow-marine transgressive deposits of the Galho do Miguel tectonosequence (transitional stage) (modified after Martins-Neto, 1993).

Table 5

Summary of the depositional characteristics of the Galho do Miguel tectonosequence

Depositional process Depositional Key lithologies Sedimentary features

setting

Eolian Hypermature fine-grained Metric to decametric thick Eolian dune migration by sandstones cross-beds; ripple marks; bimodal combination of sand-flow and

lamination sand-fall

Beach Medium-grained sandstones with Parallel-lamination or stratification Beach lamination (Clifton, 1979), locally with internal inverse grain segregation within heavy-minerals levels

grading; low-angel truncations; high-energy flows during wave backwash

ripple marks

Upper shoreface Amalgamated well-sorted, fine- to Parallel lamination; wave ripples; Intercalation of storm and medium-grained sandstone beds locally small-scale, trough and fair-weather wave-induced

processes planar cross-stratification

with heavy-minerals levels Amalgamated well-sorted,

Lower shoreface Parallel to slightly undulated Amalgamated storm events

lamination; hummocky fine-grained sandstones

cross-stratification; wave ripples

Transition zone Fine-grained sandstones Parallel stratification; hummocky Discrete storm beds (Dott and Bourgeois, 1982; Walker et al., cross-stratification; wave ripples

interbedded with pelites

1983) interbedded with fair-weather muds

Sheet-like layers with normal Vertical accretion of mud bellow Sericitic phylites (metamorphosed

Offshore

storm wave base with intervening grading from sandstones to

mudstones) with centimetric

Fig. 21. Cross-stratified sandstone of the Galho do Miguel eolian deposits.

tonosequences

(in

ascending

order),

Olaria,

Natureza, Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada,

Sopa-Brumad-inho, Galho do Miguel, Conselheiro Mata. The

Olaria tectonosequence records the prerift stage,

the Natureza, Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada and

Sopa-Brumadinho tectonosequences record the rift

stage, the Galho do Miguel tectonosequence the

transitional stage, and the Conselheiro Mata

tec-tonosequence the flexural stage. Each

tectonose-Fig. 22. Sedimentological section measured along the Pedreira creek at the eastern border of the Serra do Cabral (see Fig. 1 for location), showing the coarsening-upward rhythms which characterize the marine transgression at the transition between the Galho do Miguel and Conselheiro Mata tectonosequences (modified after Espinoza, 1996).

thickness measured in the central part of the

Espinhac¸o range.

The full life span of the Espinhac¸o basin

re-mains unknown and further geochronologic data

are required. Available geochronologic data

indi-cate rifting at ca. 1720 Ma. Using maximum

intervals derived from the literature of ca. 50

million year for rifting and ca. 200 million year for

thermal subsidence (Brunet and Le Pichon, 1982;

Allen and Allen, 1990; Perrodon and Zabec, 1990;

Bond et al., 1995; Klein, 1995), final filling of the

Espinhac¸o basin may have taken place at ca. 1500

Ma, giving a spread of ca. 200 – 250 million year

for the basin life span, which is compatible with

published data on average duration for first-order,

basin-fill cycles (e.g. Krapez, 1993; Miall, 1997).

High resolution geochronologic data are also

re-quired to test the validity of the tectonosequences

described herein and to calibrate potential future

studies directed towards quantifying rates of

sedi-mentation and subsidence.

9. Conclusions

Field-based sedimentologic, paleogeographic,

stratigraphic, structural and tectonic studies in the

paleo

/

mesoproterozoic Espinhac¸o basin,

tec-Fig. 23. Schematic stratigraphic sections showing the three depositional sequences of the Conselheiro Mata tectonosequence (modified after Dupont, 1995). Section at Conselheiro Mata area is about 900 m thick.

quence includes the record of linked depositional

systems, and is bounded by regional

unconformi-ties. These unconformities mark times when

tec-tonically

controlled

reorganization

of

basin

paleogeography took place.

The prerift and rift stages of the Espinhac¸o basin

are recorded by continental deposits in alluvial

braidplain, lake and alluvial fans

/

fan-delta

envi-ronments. During the rift stage, mechanical

subsi-dence due to lithospheric stretching predominated.

The evolution of the transitional and flexural

stages was probably controlled by thermal

subsi-dence from contraction of the lithosphere due to

cooling. The transitional stage was characterized

by relatively low subsidence rates. This induced a

decrease of the accommodation space and, as the

sediment supply was maintained, caused an

en-largement of the basin. The basal and top portions

of the transitional stage are represented by

shal-low-marine deposits, whereas the middle part

con-tains thick and extensive eolian deposits.

Higher subsidence rates and the consequent

sea-level rise characterize the flexural stage of the

Espinhac¸o basin. Shallow-marine shelf deposits

predominate in this stage. Three depositional

se-quences with a transgressive base and a

prograda-tional top can be recognized. The basal

trans-gressive parts represent initially rapid subsidence

rates, whereas the progradational tops reflect the

Fig. 24. Cartoon showing probable location (inset at bottomrelatively slow subsidence rates and overfill of the

accommodation space. These sequences probably

correspond to tectonically controlled

second-or-der cycles.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Fernando Alkmim, Joa˜o

Hippertt and P. Southgate for useful

commen-taries on an earlier draft. Dave Nelson and

espe-cially Larry Aspler are thanked for careful reviews

of the manuscript. Wulf Mueller and Pat Eriksson

are also thanked for their criticism and

construc-tive reviews of the paper. The research, which

resulted in this paper was supported by the

FAPEMIG-Research Support Foundation of

Mi-nas Gerais State, Brazil (contract no. CEX 895

/

95) and by the CNPq-Brazilian National Research

Council through a researcher fellowship to the

author (contract no. 300404

/

94-8).

References

Alkmim, F.F., Marshak, S., 1998. Transamazonian orogeny in the southern Sa˜o Francisco craton region, Minas Gerais, Brazil: evidence for paleoproterozoic collision and collapse in the Quadrila´tero Ferrı´fero. Precambrian Res. 90, 29 – 58. Alkmim, F.F., Brito Neves, B.B., Alves, J.A.C., 1993. Ar-cabouc¸o tectoˆnico do Cra´ton do Sa˜o Francisco-uma re-visa˜o. In: Dominguez, J.M.L., Misi, A. (Eds.), O Cra´ton do Sa˜o Francisco, SBG, SGM, CNPq, Salvador, pp. 45 – 62.

Allen, P.A., Allen, J.R., 1990. Basin Analysis — Principles and Applications. Blackwell (Basil), Oxford, p. 451. Almeida Abreu, P.A., Pflug, R., 1992. Geodynamic evolution

of the southern Serra do Espinhac¸o, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Part 1: the basin. 13. Geowissensch. Lateinamerika Koll., Mu¨nster, abstracts.

Araga˜o, M.A.N.F., Peraro, A.A., 1994. Elementos estruturais do Rifte Tucano/Jatoba´. Simp. Sobre o Creta´ceo do Brasil, Rio Claro. Bol. 3, 161 – 165.

Ashley, G.M., 1990. Classification of large-scale subaqueous bedforms: a new look at an old problem. J. Sediment. Petrol. 60, 160 – 172.

Badley, M.E., Price, J.D., Dahl, D.R., Agdestein, T., 1988. The structural evolution of the northern Viking graben and its bearing upon extensional models of basin formation. J. Geol. Soc. London 145, 455 – 472.

Batista, A.J., Castro, W.B.M., Greco, F.M., Uhlein, A., Kar-funkel, J., 1986. Geologia da Serra do Espinhac¸o entre

Conselheiro Mata e Rodeador, Minas Gerais. SBG Cong. Bras. Geol., 34, Goiaˆnia, Anais, 2, pp. 949 – 959. Blair, T.C., Bilodeau, W.L., 1988. Development of tectonic

cyclotems in rift, pull-apart, and foreland basins: sedimen-tary response to episodic tectonism. Geology 16, 517 – 520. Blair, T.C., 1987. Tectonic and hydrologic controls on cyclic alluvial fan, fluvial, and lacustrine rift-basin sedimentation, Jurassic-lowermost Cretaceous Todos os Santos formation, Chiapas, Mexico. J. Sediment. Petrol. 57, 845 – 862. Blair, T.C., McPherson, J.G., 1994. Alluvial fans and their

natural distinction from rivers based on morphology, hy-draulic processes, sedimentary processes, and facies assem-blages. J. Sediment. Res. A64, 450 – 489.

Bond, G.C., Kominz, M.A., Sheridan, R.E., 1995. Continental terraces and rises. In: Busby, C.F., Ingersoll, R.V. (Eds.), Tectonics of Sedimentary Basins, pp. 149 – 178.

Braun, O.P.G., Martins, M., Oliveira, W.J., 1993. Con-tinuidade das sequ¨eˆncias rifeanas sob a Bacia do Sa˜o Francisco constatada por levantamentos geofı´sicos em Mi-nas Gerais. II Simp. do Cra´ton do Sa˜o Francisco, Sal-vador, Anais, pp. 164 – 166.

Brito Neves, B.B., Cordani, U.G., 1991. Tectonic evolution of South America during the late Proterozoic. Precambrian Res. 53, 23 – 40.

Brito Neves, B.B., Kawashita, K., Cordani, U.G., Delhal, J., 1979. A evoluc¸a˜o geocronolo´gica da Cordilheira do Espin-hac¸o, dados novos e integrac¸a˜o. Revista Brasileira de Geocieˆncias 9, 71 – 85.

Brunet, M.F., Le Pichon, X., 1982. Subsidence of the Paris basin. J. Geophys. Res. 87, 8547 – 8560.

Buchwaldt, R., Toulkeridis, T., Babinski, M., Noce, C.M., Martins-Neto, M.A., Hercos, C.M., 1999. Age determina-tion and age related provenance analysis of the Proterozoic glaciation event in central eastern Brazil. II South Ameri-can Symposium on Isotope Geology, September 1999, Co´rdoba, Argentine, pp. 387 – 390.

Chaves, M.L.S.C., Uhlein, A., Dossin, I.A., 1985. Mapa Geo-lo´gico da Quadrı´cula de Sopa, escala 1:25,000. Proj. Map. Geol. Espinhac¸o Meridional, Dep. Nac. Prod. Min./Centro Geol. Eschwege, Diamantina.

Chiavegatto, J.R.S., 1992. Ana´lise estratigra´fica das sequ¨eˆncias tempestı´ticas da Formac¸a˜o Treˆs Marias (Proterozo´ico su-perior), na porc¸a˜o meridional da Bacia do Sa˜o Francisco. M.Sc. thesis, Departamento de Geologia, Escola de Minas, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil, p. 216.

Clifton, H.E., 1979. Beach lamination: nature and origin. Mar. Geol. 63, 553 – 559.

Da Silva, H.T.F., 1993. Flooding surfaces, depositional ele-ments, and accumulation rates-characteristics of the lower Cretaceous tectonosequence in the Recoˆncavo basin, northeast Brazil. Ph.D. thesis, University of Texas, Austin, USA, p. 312.

Dardenne, M.A., 1978. Sı´ntese sobre a estratigrafia do Grupo Bambuı´ no Brasil central. SBG Cong. Bras. Geol., 30, Recife, Anais, 2, pp. 597 – 610.

Destro, N., 1995. Release fault: a variety of cross fault in linked extensional fault systems, in the Sergipe-Alagoas basin, NE Brazil. J. Struct. Geol. 17, 615 – 629.

Dossin, I.A., Uhlein, A., Dossin, T.M., 1984. Geologia da faixa mo´vel Espinhac¸o em sua porc¸a˜o meridional, M.G. SBG, Cong. Bras. Geol, 33, Rio de Janeiro, Anais, 7, pp. 3118 – 3132.

Dossin, I.A., Garcia, A.J.V., Uhlein, A., Dossin, T.M., 1987. Facies eo´lico na Formac¸a˜o Galho do Miguel, Supergrupo Espinhac¸o (MG). Bol. Soc. Bras. Geol., Nu´cleo Minas Gerais 6, 85 – 96.

Dott, R.H. Jr, Bourgeois, J., 1982. Hummocky stratification: significance of its variable bedding sequences. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 93, 663 – 680.

Dupont, H., 1995. O Grupo Conselheiro Mata no seu quadro paleogeogra´fico e estratigra´fico. Bol. Soc. Bras. Geol., Nu´-cleo Minas Gerais 13, 9 – 10.

Dupont, H., 1996. O Supergrupo Sa˜o Francisco entre a Serra do Cabral e as serras do Espinhac¸o e de Minas: estudo estratigra´fico e estrutural e relac¸o˜es de contato com o Supergrupo Espinhac¸o. SBG, Cong. Bras. Geol, 39, Sal-vador, Anais, 5, pp. 489 – 493.

Dussin, I.A., Dussin, T.M., 1995. Supergrupo Espinhac¸o: Modelo de evoluc¸a˜o geodinaˆmica. Geonomos 3, 19 – 26. Dussin, T.M., 1994. Associations volcano-plutoniques de

l’Espinhac¸o me´ridional (SE-Bre´sil): Un exemple d’e´volu-tion de la crouˆte Prote´rozoı¨que. Ph.D. thesis, Univ. Or-le´ans, France, p. 177.

Eriksson, K.E., Simpson, E.L., Jackson, M.J., 1993. Strati-graphical evolution of a Proterozoic syn-rift to post-rift basin: constraints on the nature of lithosphere extension in the Mount Isa Inlier, Australia. In: Frostick, L.E., Steel, R.J. (Eds.), Tectonic Controls and Signatures in Sedimen-tary Successions. International Association of Sediment. Special Publication, 20, pp. 203 – 221.

Eriksson, P.G., Condie, K.C., Tirsgaard, H., Mueller, W., Altermann, W., Miall, A.D., Aspler, L.B., Catuneanu, O., Chiarenzelli, J.R., 1998. Precambrian clastic sedimentation systems. Sediment. Geol. 120, 5 – 53.

Espinoza, J.A.A., 1996. Sistemas deposicionais e relac¸o˜es es-tratigra´ficas da Tectonossequ¨eˆncia Conselheiro Mata, na borda leste da Serra do Cabral, Minas Gerais, Brasil. M.Sc. thesis, Departamento de Geologia, Escola de Minas, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil, p. 66.

Euze´bio, L., 1999. Mapeamento geolo´gico em unidades tec-tono-estratigra´ficas (1:25,000) na Serra do Espinhac¸o me-ridional, regia˜o de Gouveia/Serra da Miu´da, Minas Gerais. B.Sc. thesis, Departamento de Geologia, Escola de Minas, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil, p. 51.

Fogac¸a, A.C.C., Almeida Abreu, P.A., Schorscher, H.D., 1984. Estratigrafia da sequ¨eˆncia supracrustal arqueana na porc¸a˜o mediana central da Serra do Espinhac¸o, M.G. SBG, Cong. Bras. Geol, 33, Rio de Janeiro, Anais, 2, pp. 2652 – 2667.

Gawthorpe, R.L., Colella, A., 1990. Tectonic controls on coarse-grained delta depositional systems in rift basins. In: Colella, A., Prior, D.B. (Eds.), Coarse-Grained Deltas. Special Publication International Association of Sediment., 10, pp. 113 – 128.

Hercos, C.M., Martins-Neto, M.A., 1997. Considerac¸o˜es sobre os supergrupos Espinhac¸o e Sa˜o Francisco na borda oeste da Serra da A´ gua Fria (MG). Bol. Soc. Bras. Geol. Nu´cleo Minas Gerais 14, 19 – 21.

Hercos, C.M., 2000. Evoluc¸a˜o tectono-estratigra´fica da Bacia Neoproterozo´ica do Sa˜o Francisco, na regia˜o entre Pi-rapora e a Serra da A´ gua Fria, MG, com base em dados de campo e sı´smica de reflexa˜o. M.Sc. thesis, Departamento de Geologia, Escola de Minas, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil, in press.

Herrgesell, G., Pflug, R., 1986. The thrust belt of the southern Serra do Espinhac¸o, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Zbl. Geol. Pala¨ont Teil I 9/10, 1405 – 1414.

Heward, A.P., 1978a. Alluvial fans and lacustrine sediments from the Stephanian A and B (La Magdalena, Cin˜era-Matallana and Sabero) coalfields, northern Spain. Sedi-mentology 25, 451 – 488.

Heward, A.P., 1978b. Alluvial fan sequence and megasequence models: with examples from Westphalian D-Stephanian B coalfields, northern Spain. In: Miall, A.D. (Ed.), Fluvial Sedimentology. Canadian Society of Petrology and Geol-ogy Memoir, 5, pp. 669 – 702.

Hooke, R.L.B., 1972. Geomorphic evidence of late-Wisconsin and Holocene tectonic deformation, Death valley, Califor-nia. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 83, 2073 – 2098.

Hoppe, A., Otto, J., 1982. Volcanic rocks of the Espinhac¸o supergroup (Proterozoic I), eastern Brazil. V Cong. Lat. Am. Geol., Buenos Aires, Actas, IV, pp. 125 – 135. Klein, G.D., 1995. Intracratonic basins. In: Busby, C.F.,

Inger-soll, R.V. (Eds.), Tectonics of Sedimentary Basins, pp. 459 – 478.

Kleinspehn, K.L., Steel, R.J., Johannessen, E., Netland, A., 1984. Conglomeratic fan-delta sequences, late Carbonifer-ous – early Permian, Western Spitsbergen. In: Koster, E.H., Steel, R.J. (Eds.), Sedimentology of Gravels and Conglom-erates. Canadian Society of Petrology and Geology Mem-oir, 10, pp. 279 – 294.

Knauer, L.G., Schrank, A., 1993. A origem dos filitos hematı´ti-cos da Serra do Espinhac¸o Meridional, Minas Gerais. Geonomos 1, 33 – 38.

Krapez, B., 1993. Sequence stratigraphy of the Archaean supracrustal belts of the Pilbara block, Western Australia. Precambrian Res. 60, 1 – 45.

Lawrence, D.A., Williams, B.P.J., 1987. Evolution of drainage systems in response to Acadian deformation: the Devonian Battery Point formation, eastern Canada. SEPM Special Publication, 39, pp. 287 – 300.

Lewis, G.J., 1997. The development of growth faults above ductile substrates. Ph.D. thesis, University of London, England, p. 330.

Machado, N., Schrank, A., Abreu, F.R., Knauer, L.G., Almeida Abreu, P.A., 1989. Resultados preliminares da geocronologia U/Pb na Serra do Espinhac¸o Meridional. Bol. Soc. Bras. Geol., Nu´cleo Minas Gerais 10, 171 – 174. Marshak, S., Alkmim, F.F., 1989. Proterozoic contraction/

ex-tension tectonics of the southern Sa˜o Francisco region, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Tectonics 8, 555 – 571.

Martins, M., Teixeira, L.B., Braun, O.P.G., 1993. Consid-erac¸o˜es sobre a estratigrafia da Bacia do Sa˜o Francisco com base em dados de subsuperfı´cie. II Simp. do Cra´ton do Sa˜o Francisco, Salvador, Anais, pp. 167 – 169.

Martins-Neto, M.A., 1993. The sedimentary evolution of a Proterozoic rift basin: the basal Espinhac¸o supergroup, southern Serra do Espinhac¸o, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Ph.D. thesis, Albert-Ludwigs Universita¨t, Freiburg, Germany, Freiburger Geowiss. Beitr., Band 4, p. 155.

Martins-Neto, M.A., 1994. Braidplain sedimentation in a Proterozoic rift basin: the Sa˜o Joa˜o da Chapada formation, southeastern Brazil. Sediment. Geol. 89, 219 – 239. Martins-Neto, M.A., 1995a. A evoluc¸a˜o tectoˆnica da Bacia

Espinhac¸o no Estado de Minas Gerais. V SNET-Simpo´sio Nacional de Estudos Tectoˆnicos, Gramado, RS, Anais, pp. 287 – 289.

Martins-Neto, M.A., 1995b. Tectono-estratigrafia da Bacia Espinhac¸o no Estado de Minas Gerais. Bol. Soc. Bras. Geol. Nu´cleo Minas Gerais 13, 25 – 27.

Martins-Neto, M.A., 1995c. A evoluc¸a˜o paleogeogra´fica da Tectonossequeˆncia Sopa-Brumadinho, Bacia Espinhac¸o, fase rifte, na regia˜o entre Sopa e Gouveia (MG). Bol. Soc. Bras. Geol., Nu´cleo Minas Gerais 13, 16 – 18.

Martins-Neto, M.A., 1995d. Fa´cies de fluxos gravitacionais de sedimentos na Tectonossequeˆncia Sopa-Brumadinho, Bacia Espinhac¸o (MG). Bol. Soc. Bras. Geol., Nu´cleo Minas Gerais 13, 22 – 24.

Martins-Neto, M.A., 1996a. Aspectos tectono-deposicionais da Tectonossequ¨eˆncia Galho do Miguel, Bacia Espinhac¸o (MG). SBG, Cong. Bras. Geol., 39, Salvador, Anais, 5, pp. 391 – 394.

Martins-Neto, M.A., 1996b. Lacustrine fan-deltaic sedimenta-tion in a Proterozoic rift basin: the Sopa-Brumadinho tectonosequence, southeastern Brazil. Sediment. Geol. 106, 65 – 96.

Martins-Neto, M.A., 1998a. O Supergrupo Espinhac¸o em Minas Gerais: Registro de uma bacia rifte-sag do Paleo/

Mesoproterozo´ico. Revista Brasileira de Geocieˆncias 28, 151 – 168.

Martins-Neto, M.A., 1998b. Mantle plume, rifting and the early Neoproterozoic glaciation in the Sa˜o Francisco craton and Arac¸uaı´ fold belt, southeastern Brazil. In: International Conference on Precambrian and Craton tectonics/14th In-ternational Conference on Basement Tectonics, abstracts, Ouro Preto, Brazil, pp. 32 – 34.

Martins-Neto, M.A., Castro, P.T.A., Hercos, C.M., 1997a. O Supergrupo Sa˜o Francisco (Neoproterozo´ico) no Cra´ton do

Sa˜o Francisco em Minas Gerais. Bol. Soc. Bras. Geol., Nu´cleo Minas Gerais 14, 22 – 24.

Martins-Neto, M.A., Castro, P.T.A., Ramos, M.L.S., Murta, C.R., 1997b. A pseudo discordaˆncia angular entre os Super-grupos Espinhac¸o (Mesoproterozo´ico) e Sa˜o Francisco (Neoproterozo´ico), na regia˜o entre Santa Ba´rbara e Curi-mataı´, Serra Mineira (MG). Bol. Soc. Bras. Geol., Nu´cleo Minas Gerais 14, 25 – 26.

Martins-Neto, M.A., Gomes, N.S., Hercos, C.M., Reis, L.A., 1999a. Fa´cies glaciocontinentais (outwash plain) na Megassequ¨eˆncia Macau´bas, norte da Serra da A´ gua Fria (MG). Revista Brasileira de Geocieˆncias 29 (2), 281 – 292. Martins-Neto, M.A., Reis, L., Euze´bio, L., 1999b. Distribution of tectono-stratigraphic units in the southern Serra do Espinhac¸o, Minas Gerais (Brazil) and the architecture of the Espinhac¸o rift. VII SNET-Simpo´sio Nacional de Estudos Tectoˆnicos, First International Symposium on Tectonics of the SBG-Geological Brazilian Society, Lenc¸o´is, BA, Brazil, Anais, II, pp. 16 – 17.

Meyerhoff, A.A., 1982. Hydrocarbon resources in Arctic and Subarctic regions. In: Embry, A.F., Blackwill, H.R. (Eds.), Arctic Geology and Geophysics. Canadian Society of Petrol-ogy and GeolPetrol-ogy, pp. 451 – 552.

Miall, A.D., Gibling, M.R., 1978. The Siluro-Devonian clastic wedge of Somerset Island, Artic Canada, and some regional paleogeographic implications. Sediment. Geol. 21, 85 – 127. Miall, A.D., 1978. Lithofacies types and vertical profile models in braided river deposits: a summary. In: Miall, A.D. (Ed.), Fluvial Sedimentology. Canadian Society of Petrology and Geology Memoir, 5, pp. 597 – 604.

Miall, A.D., 1981. Alluvial sedimentary basins: tectonic setting and basin architecture. In: Miall, A.D. (Ed.), Sedimentation and Tectonics in Alluvial Basins. Geological Association of Canada Special Paper, 23, pp. 1 – 33.

Miall, A.D., 1997. The Geology of Stratigraphic Sequences, first ed. Springer, Heidelberg, p. 433.

Mun˜oz, A., Ramos, A., Sa´nchez-Moya, Y., Sopen˜a, A., 1992. Evolving fluvial architecture during a marine transgression: Upper Buntsandstein, Triassic, central Spain. Sediment. Geol. 75, 257 – 281.

Nemec, W., Steel, R.J., 1988. What is a fan-delta and how do we recognize it? In: Nemec, W., Steel, R.J. (Eds.), Fan-deltas: Sedimentology and Tectonic Setting. Londres, Blackie, Glasgow and London, pp. 3 – 13.

Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Noce, C.M., Vidal, P., Monteiro, R.L.B.P., Leonardos, O.H., 1992. Toward a new tectonic model for the late Proterozoic Arac¸uaı´ (SE Brazil)-West Congolian (SW Africa) belt. J. South Am. Earth Sci. 6, 33 – 47.

Pedrosa-Soares, A.C., Dardenne, M.A., Hasui, Y., Castro, F.D.C., Carvalho, M.V.A., Reis, A.C., 1994. Mapa Geo-lo´gico do Estado de Minas Gerais, escala 1:1,000,000 e Nota Explicativa, COMIG, Belo Horizonte, p. 97.

Perrodon, A., Zabec, J., 1990. Paris basin. In: Leighton, M.W., Kolata, D.R., Oltz, D.F., Eidel, J.J. (Eds.), Interior Cratonic Basins. AAPG Memoir, 51, pp. 633 – 679. Pflug, R., 1965. A geologia da parte meridional da Serra do

Espinhac¸o e zonas adjacentes. Rio de Janeiro, DNPM/

DGM, Boletim, 226, p. 51.

Pflug, R., 1968. Observac¸o˜es sobre a estratigrafia da Se´rie Minas na regia˜o de Diamantina, Minas Gerais. Rio de Janeiro, DNPM/DGM, Notas Prel., 142, p 20.

Pflug, R., Hoppe, A., Brichta, A., 1980. Paleogeografia do Precambriano na Serra do Espinhac¸o, Minas Gerais, Brasil. In: Zeil, W. (Ed.), Nuevos Resultados de la Investi-gation Geocientı´fica Alemana en Latinoame´rica. Projectos de la Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, DFG/Boldt, Bop-pard, pp. 33 – 43.

Pflug, R., Renger, F.E., 1973. Estratigrafia e evoluc¸a˜o geolo´g-ica da margem SE do Cra´ton Sanfranciscano. SBG Cong. Bras. Geol., 27, Aracaju´, Anais, 2, pp. 5 – 19.

Pimentel, M.M., Fuck, R.A., Dardenne, M.A., Silva, L.J.H.D., Menezes, P.R., 1995. O magmatismo a´cido pera-luminoso associado ao Grupo Araxa´ na regia˜o entre Pires do Rio e Ipamerı´, Goia´s: Caracterı´sticas geoquı´micas e implicac¸o˜es geotectoˆnicas. In: Simp. Geol. Centro-Oeste, Anais, Goiaˆnia, pp. 68 – 71.

Reis, L., 1999. Mapeamento geolo´gico em unidades tectono-estratigra´ficas (1:25,000) na Serra do Espinhac¸o merid-ional, regia˜o de Sopa/Guinda, Minas Gerais. B.Sc. thesis, Departamento de Geologia, Escola de Minas, Universi-dade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil, p. 64. Romeiro Silva, P.C., 1997. A passagem do Mesoproterozo´ico

para o Neoproterozo´ico no centro-leste do Brasil e o estilo estrutural envolvido. Bol. Soc. Bras. Geol. Nu´cleo Minas Gerais 14, 9.

Schlee, J.S., Hinz, K., 1987. Seismic stratigraphy and facies of continental slope and rise seaward of Baltimore canyon trough. AAPG Bull. 71, 1046 – 1067.

Schobbenhaus, C., 1993. Das Mittlere Proterozoikum Brasiliens mit besonderer Beru¨cksichtung des zentralen Osten: Eine Revision. Ph.D. thesis, Albert-Ludwigs Uni-versita¨t, Freiburg, Germany, p. 166.

Scho¨ll, W.U., Fogac¸a, A.C.C., 1981. Mapa Geolo´gico da Quadrı´cula de Guinda, escala 1:25,000. Proj. Map. Geol. Espinhac¸o Meridional, Dep. Nac. Prod. Min./Centro Geol. Eschwege, Diamantina.

Scho¨ll, W.U., 1972. Der su¨dwestliche Randbereich der Espin-hac¸o-Zone, Minas Gerais, Brasilien. Geol. Rdsch. 61, 201 – 216.

Silva, R.R., 1995. Contribution to the stratigraphy and paleo-geography of the lower Espinhac¸o supergroup

(Meso-proterozoic) between Diamantina and Gouveia, Minas Gerais, Brazil. Ph.D. thesis, Albert-Ludwigs Universita¨t, Freiburg, Germany, Freiburger Geowiss. Beitr., Band 8, p. 115.

Souza Fo, R.C., 1995. Arcabouc¸o estrutural da porc¸a˜o externa da Faixa Arac¸uaı´ na Serra do Cabral (MG) e o contraste de estilos deformacionais entre os supergrupos Espinhac¸o e Sa˜o Francisco. M.Sc. thesis, Departamento de Geologia, Escola de Minas, Universidade Federal de Ouro Preto, Ouro Preto, Brazil, p. 148.

Steel, R.J., Mæhle, S., Nilsen, H.R., Røe, S.L., Spinnangr, A,., 1977. Coarsening upward cycles in the alluvium of Horne-len basin (Devonian, Norway) — sedimentary reponse to tectonic events. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 88, 1124 – 1134. Teixeira, L.B., Martins, M., Braun, O.P.G., 1993. Evoluc¸a˜o

geolo´gica da Bacia do Sa˜o Francisco com base em sı´smica de reflexa˜o e me´todos potenciais. II Simp. do Cra´ton do Sa˜o Francisco, Salvador, Anais, pp. 179 – 181.

Trompette, R., 1994. Geology of Western Gondwana (2000 – 500 Ma): Pan-African-Brasiliano Aggregation of South America and Africa. A.A. Balkema, Rotterdam, p. 350. Trompette, R., Uhlein, A., Silva, M.E., Karmann, I., 1992.

The Brasiliano Sa˜o Francisco Craton revised (central Brazil). J. South Am. Earth Sci. 6, 49 – 57.

Tunbridge, I.P., 1981. Sandy high-energy flood sedimentation-some criteria for recognition, with an example from the Devonian of SW England. Sediment. Geol. 28, 79 – 96. Tunbridge, I.P., 1984. Facies model for a sandy ephemeral

stream and clay playa complex; the middle Devonian Trentishoe formation of North Devon, UK. Sedimentol-ogy 31, 697 – 716.

Uhlein, A., 1991. Transic¸a˜o cra´ton-faixa dobrada: exemplo do Cra´ton do Sa˜o Francisco e da Faixa Arac¸uaı´ (Ciclo Brasil-iano) no Estado de Minas Gerais. Aspectos Estratigra´ficos e Estruturais. Ph.D. thesis, Inst. de Geocieˆncias, Universi-dade de Sa˜o Paulo, Sa˜o Paulo, Brazil, p. 295.

Walker, R.G., Duke, W.L., Leckie, D.A., 1983. Hummocky stratification: significance of its variable bedding sequences. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 94, 1245 – 1249.

Wells, N.A., 1984. Sheet debris flows and sheetfloods con-glomerates in Cretaceous cool-marine alluvial fans, South Orney Islands, Antarctica. In: Koster, E.H., Steel, R.J. (Eds.), Sedimentology of Gravels and Conglomerates. Canadian Society of Petrology and Geology Memoir, 10, pp. 133 – 145.

White, N., McKenzie, D., 1988. Formation of the ‘steer’s head’ geometry of sedimentary basins by differential stretching of the crust and mantle. Geology 16, 250 – 253.