Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:49

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Flipping the Classroom Applications to Curriculum

Redesign for an Introduction to Management

Course: Impact on Grades

Michael Albert & Brian J. Beatty

To cite this article: Michael Albert & Brian J. Beatty (2014) Flipping the Classroom Applications to Curriculum Redesign for an Introduction to Management Course: Impact on Grades, Journal of Education for Business, 89:8, 419-424, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.929559

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2014.929559

Published online: 04 Nov 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 410

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Flipping the Classroom Applications to Curriculum

Redesign for an Introduction to Management Course:

Impact on Grades

Michael Albert and Brian J. Beatty

San Francisco State University, San Francisco, California, USA

The authors discuss the application of the flipped classroom model to the redesign of an introduction to management course at a highly diverse, urban, Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business–accredited U.S. university. The author assessed the impact of a flipped classroom versus a lecture class on grades. Compared to the prior lecture class taught by the same instructor using the same text and tests, results indicate that grades on all three exams were higher, and grades on two of three exams were significantly higher.

Keywords: curriculum redesign, flipping the classroom, impact on grades, introduction to management course

During the past several years, advances in technology have continued to transform the way education is experienced for instructors and students. With low-cost computer-based video capture capabilities becoming more readily available, capturing, editing and posting digital video recordings is a realistic option for anyone who wants to produce informa-tion on literally any particular subject for a global audience. The Khan Academy, founded when Sal Khan began posting math tutorial videos for relatives and friends, has received substantial publicity and investment capital (Upbin, 2010).

In 2007, two rural Colorado high school chemistry teachers, Jonathan Bergmann and Aaron Sams, were con-cerned about students frequently missing end-of-day classes when leaving for sports and other competitions, and they began to record and post their lectures and demonstrations on YouTube. Their rethinking of the traditional paradigm to classroom education is discussed in the seminal book

Flip Your Classroom(Bergmann & Sams, 2012). They also created the nonprofit Flipped Learning Network (flipped-learning.org).

With lecture capture technology, students can watch lec-tures, view demonstrations and other presentation material before each class session, and focus on concept application activities during live classroom sessions (Zupancic & Horz, 2002). According to Harrison Keller, vice provost for

higher educational policy at University of Texas at Austin, “If you do this well, you can use faculty member’s time and expertise more appropriately, and you can use your facili-ties more efficiently. More important, you can get better student-learning outcomes” (Berrett, 2012, p. 2).

PURPOSES OF THE STUDY

The primary purpose of the study was to assess and com-pare the impact of a flipped classroom versus a lecture class on student grades. Four additional areas of focus include (a) the pedagogical rationale for the flipped classroom model, (b) the literature on applications and grade out-comes from flipped classrooms to higher education, (c) the redesign of an introduction to management (MGMT) course to a flipped classroom model, and (d) key design fac-tors for a flipped classroom model.

FLIPPING THE CLASSROOM: PEDAGOGICAL RATIONALE

A flipped classroom model fundamentally changes the lec-ture-centered mode of instruction to one that is more learn-ing-centered where the instructor focuses on using class time to improve understanding that the student has attained from watching prerecorded video material and completing Correspondence should be addressed to Michael Albert, San Francisco

State University, College of Business, 1600 Holloway Avenue, San Fran-cisco, CA 94132, USA. E-mail: malbert@sfsu.edu

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.929559

assigned readings. In this regard, Strayer (2012) stated that it “moves the lecture outside the classroom and uses learn-ing activities to move practice with the concepts inside the classroom” (p. 171). These learning-centered activities use active learning to engage the student’s thinking during class time. Educators using a learning-centered approach engage students in actively constructing knowledge (Huba & Freed, 2000). According to Michael (2006), active learning enables students to develop mental models, test the validity of these models (an individual’s understanding), and then change potentially faulty understanding and misconcep-tions. From the vantage point of (Bloom’s (1956) taxon-omy, the focus of class time is on applying, analyzing, and evaluating rather than on basic understanding.

Research on active learning has shown that it contributes to student learning, achievement, and engagement (Chap-lan, 2009; Freeman et al., 2007; Knight & Wood, 2005; Prince, 2004). The techniques used in courses that flip the classroom all share the same underlying imperative—stu-dents should not passively receive information in class and then be tasked with struggling to apply that information on their own outside of class. Note that many educators have used active learning techniques for years; however, in large classes the lecture-based delivery mode has dominated.

The manner in which the educator role is performed has an impact on the use of active learning. King (1993) described two contrasting educator roles as the sage on the stage versus the guide on the side. Historically, the role of the teacher has been to communicate knowledge to students during class, and then to assign homework to reinforce what was discussed in class. In essence, the professor lec-tures and the students listen and take notes. King (1993) contended that this passive approach to learning—known as the transmittal model—views students’ brains as empty containers into which knowledge is poured. In contrast, when playing the role as the guide on the side, the professor facilitates understanding by enabling the students to do something with the information they have read and heard. The role of the educator is paramount to transform the edu-cation process from content centered and teacher centered to learning centered and student centered (Fink, 2003; Huba & Freed, 2000; Saulnier, 2009).

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Research focusing on the effectiveness of the flipped class-room in higher education is extremely limited (Findlay-Thompson & Mombourquette, 2014; Hamdan, McKnight, McKnight & Arfstrom, 2013). Few published studies have focused on the impact of a flipped classroom on grades. Of the four studies I identified that focused on grades, two focused on core business courses and found no difference between the flipped classroom and the lecture class, and

two focused on a pharmacy and an electrical engineering course and found higher grades in the flipped classroom.

Findlay-Thompson and Mombourquette (2014) used a flipped classroom for one of three sections of an introduc-tion to business class at Mount Saint Vincent University. A traditional lecture was used in the other two sections. Stu-dents were given the same course outlines in all three sec-tions, with identical assignments and exams. In the flipped classroom, students watched videos outside of class and completed and discussed assignments during class, rather than working on them at home. No differences were found between grades among the three sections. Davies, Dean, and Ball (2013) did not find any difference in grades between a flipped class in which students watched videos outside of class and a lecture class for an introductory infor-mation systems and spreadsheet course at Brigham Young University. Ferreri and O’Connor (2013) redesigned a large lecture-oriented pharmacy course at the University of North Carolina to a flipped classroom using small-group case-based discussions during class time. Instead of using con-tent delivery by lecture, students spend class time gathering and applying patient information to self-care scenarios. They found significantly better grades with the flipped classroom. Papadopoulos and Roman (2010) used a flipped classroom approach in an electrical engineering class where students watched video lectures before class and worked on problem-solving exercises during class. They found higher test scores in the flipped class.

APPLYING THE FLIPPED CLASSROOM MODEL: INTRODUCTION TO MANAGEMENT

University Background

A flipped classroom model was applied to an MGMT course at a large, urban, diverse, Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business–accredited business school in the fall 2013 semester. There were approximately 5,200 students enrolled in the business school, accounting for 20% of university enrollment. Business students are highly diverse: Asian, Caucasian non-Hispanic, combined Latino, Filipino, and African American populations accounted for approximately 42%, 27%, 12%, 9%, and 5% of the student body, respectively.

Course Background

MGMT is one of 12 required core-courses required of all business majors. Students need junior standing to enroll. This MGMT course is the only undergraduate class in the business school to use a flipped classroom model. The key factor that led to course redesign was the availability of San Francisco State University’s CourseStream, a simple lec-ture/video capture system that enables an instructor to use

420 M. ALBERT AND B. J. BEATTY

any computer to record his or her lecture presentation and then easily post on the class course site. Prior to offering the flipped class, the course was taught by the same instruc-tor using a more traditional lecture style in the university theater. Although video cases were used, and there was some student discussion of work experiences, the course was primarily lecture.

FLIPPED CLASSROOM REDESIGN: KEY CONSIDERATIONS

Much of the research focused on the specific pedagogi-cal approach of flipped classrooms is just beginning to be published (Davies et al., 2013). Although there are a variety of ways that educators have implemented a flipped classroom (Bergmann, 2013; Bergmann & Sams, 2012; Hughes, 2012), flipped classrooms share five key characteristics: (a) the educational process transforms students from passive to active learners; (b) technology facilitates the approach; (c) class time and traditional homework time are inverted so that homework is done first; (d) content is given real-world context; and (e) class activities engage students in higher orders of criti-cal thinking and problem solving or help them grasp particularly challenging concepts (Bergmann & Sams, 2012). The instructor used these characteristics when redesigning the MGMT class to a flipped classroom.

I also consider the technology associated with any edu-cational process to be only one part of a learning system. As such, the technology must be integrated with appropriate pedagogies to add value both to the recorded video lecture and to the in-class student experience. Discussing this, Tucker (2012) stated, “it is not the instructional videos on their own, but how they are integrated into an overall approach that makes the difference” (p. 82).

The subsequent discussion is enumerated to highlight applications of these characteristics and additional key fac-tors focused on when redesigning the MGMT course into a flipped classroom model:

1. Convert each chapter to video capture, broken into several learning segments.Each of these video chap-ter segments summarizes the week-by-week lecture material. Students watch these videos and complete the assigned readings before each class. It is essential to have supporting slides that students can view dur-ing the digital presentation. Chapters should be divided into short segments so students can watch and learn at their own pace. In this regard, the instructor divided each of the 15 chapters into 2–4 segments. Chapters averaged a total of 76 min. 2. Redesign your curriculum: develop/select content for

in-class discussion that promotes active learning focused on key course concepts. It is essential to

identify the critical few key concepts for each chapter that will provide the context for in-class discussion and be the focus for active learning. The instructor used four types of content to promote active learning through discussion and to add value to the assigned readings and viewed lectures: (a) application ques-tions for each chapter that appeared in the course notebook, (b) video cases with application questions, (c) movie clips focused on key concepts, and (d) other multimedia material created by the author or edited from business oriented cable channels. Of these four, the application questions accounted for 50–65% of class time. Examples of application ques-tions from one chapter appear in the Appendix. 3. Create incentives for student participation.Because

students are needed to provide application-to-work examples during class, there should be incentives for such participation. Whereas instructors usually have the option of student participation grades in smaller classes, this is not practical in a class of 325. Instead, incentives were designed so students could increase their grade by as much as 10% through (a) correctly answering extra-credit multiple-choice questions focused on the video cases which were only available to view in class, (b) writing responses to one chapter application set of questions and sharing views of one question with the class, (c) subscribing to theWall Street Journal during the class, and (d) writing a summary of the implications of aWall Street Journal

article to chapter content and sharing with the class. 4. Provide students with an understanding of the flipped

classroom model.Students have probably not been in a flipped classroom. During the first class, it is essen-tial to discuss the flipped classroom model, and also summarize this on the syllabus. It is also important to exude authentic passion about the potential of the flipped classroom to the students.

5. Create a sense of ownership and commitment. An attitude of “We can do things differently in this class—but ‘we’ implies ‘you and I’” can provide stu-dents with a feeling of engagement to be part of a flipped classroom. Moreover, this attitude—commu-nicated throughout the semester—places some responsibility on the students to make the flipped classroom model a success, rather than have it rest solely on the instructor. This is particularly important during the first three to four weeks of the course. 6. Make other key changes to syllabus and supporting

material. Because syllabi and website postings are critical considerations regardless of the type of class model used, these need reassessment for a flipped classroom. In addition to summarizing the flipped classroom in the syllabus, the instructor provided a list of 10–12 key concepts to know for each chapter that were posted on the course website. Chapter video

files were also posted with the time of each video segment, and the respective chapter pages of each video segment.

METHODS

A quasiexperimental design used nonequivalent groups to compare the impact of the flipped classroom, the treatment group, to the lecture, the control group, on student exam grades. The lecture class was taught during the fall 2012 semester, and the flipped class was taught during the fall 2013 semester. The courses were identical and used the same text, syllabus, and tests, the same key chapter con-cepts, and were taught by the same instructor at the same time of day in the university theater. Both classes had opportunities for extra credit, which could raise a student’s grade by a maximum of 10%.

DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS

An independent samples t-test was conducted to examine whether there was a significant difference between the per-formance of students in Fall 12 and Fall 13 classes in rela-tion to their test scores on three exams. As indicated in Tables 1–3, the test revealed a statistically significant dif-ference between students in Fall 12 and students in Fall 13 for Test 1, t(527.295) D–2.666, p <.008; and Test 3, t (588.305)D–2.605,p<.009; but not for Test 2,t(915)D –1.733,p<.083.

For Test 1, students in Fall 12 (MD.7665,SDD.11653) scored significantly lower than students in Fall 13 (M D

.7924,SD D15162). For Test 3, students in Fall 12 (MD

.7526, SD D .12527) scored significantly lower than stu-dents in Fall 13 (MD.7773,SDD.14215). For Test 3, stu-dents in Fall 12 did score lower than stustu-dents in Fall 13, but significance did not reach .05.

DISCUSSION

As discussed previously, the present literature on the impact of flipped classrooms in higher education on grades is extremely limited; only four studies have focused on grades, and only two of these studies have reported higher grades in a flipped classroom. Moreover, prior to this study, only two studies have focused on Business courses, and both of these studies did not show any difference in grades with a flipped classroom (Findlay-Thompson & Mombour-quette, 2014; Davies et al., 2013).

The quasiexperimental design of the study, and the fact that the same instructor taught the lecture class and the flipped class with the same readings, key chapter concepts, and exams, provides strong support to the finding of

increased performance on grades in the flipped classroom. The results from this research suggest that the flipped class-room has the potential to contribute to increased student performance on grades. I strongly believe that the most sig-nificant factor for a flipped classroom to have a positive impact on student performance is for the instructor to rede-sign the curriculum so that the videos watched prior to class are integrated into each class with active learning pedago-gies. In this regard, I contend that Tucker (2012) focused on the essential DNA of flipped classrooms when stating it is how teachers integrate the videos into an overall approach that makes the difference The six characteristics and factors central to redesign of the MGMT course previ-ously discussed guided the integration process.

The finding from the study demonstrates the potential of a flipped classroom to have a positive impact on grades. To what extent the finding can be generalized to other business courses in management—and to other business courses— cannot be determined due to several imitations of this research. To what extent the results are somewhat attribut-able to the instructor’s ability to engage, positively influ-ence, or integrate the videos with active learning pedagogies designed for each class cannot be determined from this study. The very large class size may also be a fac-tor—650 in the lecture class and 325 in the flipped class. In this regard, it may be that in smaller classes of 30–50 indi-viduals, students do equally well in either type of class. Moreover, the exams in this study were multiple choice. To what extent student performance would be different in a lecture class if exams required written responses to man-agement situations, mini cases, and description of key con-cepts cannot be determined from this study.

IMPLICATIONS: FUTURE RESEARCH

As more educators develop courses using flipped classroom designs, I suggest three key research streams focus on (a) student performance and grades, (b) student perceptions and engagement, and (c) analysis of key factors related to student performance and grades.

Research directed to the impact of a flipped classroom on grades would focus on a variety of business courses, both introductory and advanced, and at the undergraduate

TABLE 1

Group Statistics (Term 0DFall ’12, Term 1 = Fall ’13)

Test Term n M SD SE M

Test 1 0 596 .7665 .11653 .00477 1 321 .7924 .15162 .00846 Test 2 0 596 .7375 .13039 .00534 1 321 .7534 .13664 .00763 Test 3 0 596 .7526 .12527 .00513 1 321 .7773 .14215 .00793 422 M. ALBERT AND B. J. BEATTY

and graduate levels. If the same instructor teaches the class with the same readings and tests, this quasiexperimental design could provide evidence of the impact of the flipped class on student performance. It may be found, for example, that the flipped classroom has greater impact on grades in advanced classes or at the graduate level due to the possibil-ity that students enrolled in these courses are more invested in their educational experience.

Research directed to student perceptions/engagement would focus on student attitudes and perceptions of their flipped classroom experience, and build on the modest research that has been done in this area. In this regard, Bishop and Verleger (2013) reviewed recent research and found 11 studies focused on student perceptions of the flipped classroom. They reported the results have been con-sistent with general student opinion being positive, with a significant minority having some negative views. Enfield (2013) discussed the survey he developed to assess student perceptions of a flipped classroom, and the results he found. Other surveys that educators develop, or interview method-ologies used, to assess perceptions and engagement of flipped classrooms would add to the limited literature. For example, Findlay-Thompson and Mombourquette (2014) described methodology focused on interviewing students related to their experience in the flipped classroom.

Research directed to key factors related to student perfor-mance and grades could focus on, for example, when and how often students watch the videos before class. It may be

that students who do not perform well in a flipped class do not watch the videos before class, or at all. Or, perhaps some students cram and watch the videos only before a test. There are data on university servers that track when students actually log into the course website to access video material posted for the course. This type of data, combined with data from student surveys, could be used to analyze key factors related to student performance in flipped classrooms.

CONCLUDING PERSPECTIVE

With the recent emergence of low-cost video capabilities available in many lecture halls, classrooms, and on most computers to capture digital recordings of presentations, coupled with university-based software and servers, educa-tors have a paradigm-shifting toolbox to reframe education and the student learning experience. However, as with any new technology, potential users—educators—may be reluc-tant to use the technology because they are comfortable teaching in a particular way, and there are few incentives for change. From the time-travel perspective of the authors, if it were possible to wake up tomorrow and have it be the year 2025, most educators, whether they teach in classrooms or online, would be creating their own videos or using some other educator’s video material. Students would be watching these videos as homework, and the educator would be facili-tating discussion to add value and build on the foundation knowledge and concepts from the assigned reading and assigned video material/tutorials. Tablet computers, smart-phones—with larger screens—and other soon-to-be-emerg-ing technologies and products—will continue to have the potential to enhance education, just as chalk, blackboards, transparency projectors, and the web have. In this regard, I strongly believe that educators need to decide when—not if—they want to make the transition to a flipped classroom.

REFERENCES

Bergmann, J. (Ed.). (2013).Flipping 2.0: Practical strategies for flipping your class. New Berlin, WI: The Bretzmann Group.

TABLE 2 Independent Samples Test

Levene’s test for equality of variances tfor equality of means

Test Variance F Sig. t df Sig. (2-tailed) Mean difference

Test 1 Equal variances assumed 30.471 .000 ¡2.881 915 .004 ¡.02591

Equal variances not assumed ¡2.666 527.295 .008 ¡.02591

Test 2 Equal variances assumed 1.683 .195 ¡1.733 915 .083 ¡.01592

Equal variances not assumed ¡1.709 629.412 .088 ¡.01592

Test 3 Equal variances assumed 3.953 .047 ¡2.705 915 .007 ¡.02461

Equal variances not assumed ¡2.605 588.305 .009 ¡.02461

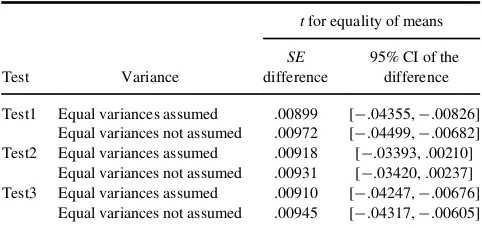

TABLE 3 Independent Samples Test

tfor equality of means

Test Variance

SE

difference

95% CI of the difference

Test1 Equal variances assumed .00899 [¡.04355,¡.00826]

Equal variances not assumed .00972 [¡.04499,¡.00682]

Test2 Equal variances assumed .00918 [¡.03393, .00210]

Equal variances not assumed .00931 [¡.03420, .00237]

Test3 Equal variances assumed .00910 [¡.04247,¡.00676]

Equal variances not assumed .00945 [¡.04317,¡.00605]

Bergmann, J., & Sams, A. (2012).Flip the classroom. Washington, DC: International Society for Technology in Education.

Berrett, D. (2012). How “flipping” the classroom can improve the tradi-tional lecture. Education Digest: Essential Readings Condensed for Quick Review,78, 36–41.

Bishop, J. L., & Verleger, M. A. (2013, June).The flipped classroom: A sur-vey of the research. Paper presented at the 120th American Society of Engineering Education Annual Conferences & Exposition, Atlanta, GA. Bloom, B. S. (1956).Taxonomy of educational objectives, handbook I: The

cognitive domain. New York, NY: David McKay.

Chaplin, S. (2009). Assessment of the impact of case studies on student learning gains in an introductory biology course.Journal of College Sci-ence Teaching,39, 72–79.

Davies, R., Dean, D., & Ball, N. (2013). Flipping the classroom and instructional technology integration in a college-level information sys-tems spreadsheet course.Educational Technology Research and Devel-opment,61, 563–580.

Enfield, J. (2013). Looking at the impact of the flipped classroom model of instruction on undergraduate multimedia students at CSU, Northridge.

TechTrends,57(6), 14–27.

Ferreri, S., & O’Connor, S. (2013). Redesign of a large lecture course into a small-group learning course. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education,77(1), 13. doi: 10.5688/ajpe77113

Findlay-Thompson, S., & Mombourquette, P. (2014). Evaulation of a flipped classroom in an undergraduate business course.Business Educa-tion & AccreditaEduca-tion,6, 63–71.

Fink, L. D. (2003).Creating significant learning experiences. San Fran-cisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Freeman, S., O’Connor, E., Parks, J. W., Cunningham, M., Hurley, D., Dirks, C., & Wenderoth, M. P. (2007). Prescribed active learning increases performance in introductory biology.CBE Life Science Educa-tion,6, 132–139.

Hamdan, N., McKnight, P., McKnight, K., & Arfstrom, K. M. (2013).A review of flipped learning. Retrieved from http://www.flippedlearning.org Huba, M. E., & Freed, J. E. (2000).Learner-centered assessment on

col-lege campuses: Shifting the focus from teaching to learning. Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Hughes, H. (2012). Introduction to flipping the college classroom. In T. Amiel & B. Wilson (Eds.),Proceedings from world conference on edu-cational multimedia, hypermedia, and telecommunications(pp. 2434– 2438). Chesapeake, VA: AACE.

King, A. (1993). From sage on the stage to guide on the side. College Teaching,41, 30–35.

Knight, J., & Wood, W. (2005). Teaching more by lecturing less.Cell Biol-ogy Education,4, 298–310.

Michael, J. (2006). Where’s the evidence that active learning works?

Advances in Physiology Education,30, 159–167.

Papadopoulos, C., & Roman, A. S. (2010, October). Implementing an inverted classroom in engineering statistics: initial results. Proceedings

of the 40th ASEE/IEEE Frontiers in Education Conference, Washington, DC.

Prince, M. (2004). Does active learning work? A review of the research.

Journal of Engineering Education,93, 223–231.

Saulnier, B. (2009). From “sage on the stage” to “Guide on the side revis-ited”: (Un)convering the content in the lecture-centered information sys-tems course.Information systems Education Journal,7(60), 1–10. Strayer, J. (2007).The effects of the classroom flip on the learning

environ-ment: a comparison of learning activity in a traditional classroom and a flip classroom that used an intelligent tutoring system. (Electronic The-sis or Dissertation). The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH. Retrieved from https://etd.ohiolink.edu/

Strayer, J. (2012). How learning in an inverted classroom influences coop-eration, innovation and task orientation. Learning Environments Research,15, 171–193.

Tucker, B. (2012). The flipped classroom.Education Next,12(1), 82. Upbin, B. (2010, October 28). Khan Academy: A name you need to know

in 2011. Forbes. Retrieved from http://www.forbes.com/sites/ bruceupbin/2010/10/28/khan-academy-a-name-you-need-to-know-in-2011/

Zupancic, B., & Horz, H. (2002, June).Lecture recording and its use in a traditional university course. Paper presented at the Annual Joint Con-ference Integrating Technology into Computer Science Education, Aarhus, Denmark.

APPENDIX: Application Discussion Questions

Note: These questions appear in the course notebook and are formatted so the student has approximately one-half page per question.

Management in the 21st Century—Chapter 1

1. Describe two specific examples of important effectiveness goals of an organization where you worked, or interview someone with experience.

2. Describe any of the 21st Century trends discussed in Chap-ter 1 that are relevant to the organization. Describe what the organization has done to respond to these trends? 3. Describe the job focus of a senior manager, middle

man-ager, or supervisor in the organization.

4. Describe a manager you have worked for who is highly competent. Summarize why you think he/she is highly competent as a manager. Focus on what he/she does that is particularly competent.

424 M. ALBERT AND B. J. BEATTY