www.elsevier.com / locate / bres

Research report

Neonatal polyamine depletion by

a

-difluoromethylornithine: effects on

adenylyl cyclase cell signaling are separable from effects on brain

region growth

a ,

*

b b a aT.A. Slotkin

, S.A. Ferguson , A.M. Cada , E.C. McCook , F.J. Seidler

a

Department of Pharmacology and Cancer Biology, Box 3813, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC 27710, USA

b

Division of Neurotoxicology, National Center for Toxicological Research, U.S. Food and Drug Administration, Jefferson, AR 72079, USA

Accepted 12 September 2000

Abstract

Ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) and the polyamines play an essential role in brain cell replication and differentiation. We administered

a-difluoromethylornithine (DFMO), an irreversible inhibitor of ODC, to neonatal rats on postnatal days 5–12, during the mitotic peak of the cerebellum, a treatment regimen that leads to selective growth inhibition and dysmorphology. In adulthood, cell signaling responses mediated through the adenylyl cyclase pathway were evaluated in order to determine if synaptic dysfunction extends to regions that appear to be otherwise unaffected by DFMO. Total adenylyl cyclase catalytic activity, evaluated with the direct enzymatic stimulant,

21

Mn , was significantly elevated in male rats both in the cerebellum and in brain regions showing no growth retardation (cerebral cortex, brainstem); there were no significant effects in females. In contrast, signaling mediated through the G proteins that couple neurotransmitter receptors to adenylyl cyclase showed a deficit in the DFMO group, as evaluated with the response to fluoride; in males, there was no corresponding increase in activity as would have been expected solely from the enhancement of adenylyl cyclase, and in females, there was actually a significant decrease in the response to fluoride. Again, the deficits were not restricted to the cerebellum. Stimulation of adenylyl cyclase by isoproterenol, ab-adrenergic receptor agonist that acts through G , likewise displayed deficits in boths

males and females, and without distinction by brain region. These results indicate that the ODC / polyamine pathway plays a role in the development of cell signaling, and hence in neurotransmission, above and beyond its role in cell replication and differentiation. Given the fact that numerous drugs and environmental contaminants have been shown to alter ODC and the polyamines in the developing brain, our findings suggest that changes in brain region growth or structure are inadequate to predict the targeting of specific neurotransmitter or signaling pathways, and that gender-selective functional defects may be present despite the absence of morphological differences. 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Theme: Development and regeneration

Topic: Neurotrophic factors: receptors and cellular mechanisms

Keywords: Adenylyl cyclase;b-Adrenergic receptor;a-Difluoromethylornithine; G protein; Ornithine decarboxylase

1. Introduction neurogenesis and architectural assembly [1,16,17] and

accordingly, ODC is rapidly responsive to conditions that Ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) catalyzes the initial step change these developmental events [17]. For this reason, in the formation of polyamines, major intracellular reg- ODC has proven useful to identify adverse developmental ulators of cell replication and differentiation [9,17]. A effects of drugs and environmental contaminants that target normal ODC developmental pattern is essential for proper the developing brain [4,6,7,9,12,15,17,27,28].

Whereas the roles of ODC and the polyamines in cell replication and differentiation have been well

character-*Corresponding author. Tel.: 11-919-681-8015; fax: 1

1-919-684-ized, it is unclear whether they influence the ontogeny of

8197.

E-mail address: [email protected] (T.A. Slotkin). specific neurotransmitter or signaling pathways over and

above more generalized aspects of cell development. This activity in the developing brain, with corresponding deple-question is of critical importance because alterations in tion of putrescine and spermidine [21]; activities recover ODC activity have been noted after fetal or neonatal within 1 week post-treatment, with only transient impair-exposure to drugs or toxic chemicals that do not evoke ment of general growth. DFMO treatment during this gross alterations in brain growth or morphology postnatal period impairs cerebellar growth and elicits [4,6,7,9,12,15,17,27,28]. If changes in polyamine synthesis reductions in cell number [5] and lasting anomalies of influence the development of cellular function, and not just cerebellar structure [1,16].

replication and differentiation, then straightforward mea- Brains were dissected into nine regions [8], weighed, surements of growth and morphology are inadequate flash-frozen and stored at 2458C. For this study, the predictors of fetal or neonatal brain injury. To test this cerebral cortex (less the frontal cortex), brainstem, and hypothesis, we have utilized a-difluoromethylornithine cerebellum were assayed. Care was taken so that each (DFMO), a specific and irreversible inhibitor of ODC that researcher dissected an equal number of animals from each is devoid of systemic toxicity [4,12,17,26]. Daily postnatal treatment group.

administration of DFMO to neonatal rats results in

imme-diate and persistent deficits of ODC activity, depletion of 2.2. b-Receptor binding putrescine and spermidine, and retardation of brain growth

targeted toward regions undergoing peaks of cell replica- Receptor binding capabilities were determined by meth-tion and differentiameth-tion [1,3,4,16,17,21,25]. With appro- ods described in earlier publications [14,20,24,29]. The priate selection of a treatment window, DFMO causes overall strategy was to examine binding at a single, selective growth retardation of specific brain regions while subsaturating ligand concentration in preparations from

sparing other regions. every animal. The selection of a single concentration of

In the current study, we have utilized a brief DFMO radioligand for the receptor analysis enables the detection treatment in neonatal rats that elicits alterations in growth of changes in either Kd or Bmax but does not permit and structure of the cerebellum only, including atrophy and distinction between the two possible mechanisms; this deficits in cell number [1,5,16], and have examined the strategy was necessitated by the requirement to measure effects when the animals reach adulthood. However, there receptor binding along with several different measures of is some evidence that this treatment alters functional adenylyl cyclase activity, across two treatment groups, development of neurotransmitter pathways elsewhere in both genders and three tissues (over 100 separate mem-the brain, culminating in disruption of complex behavioral brane preparations).

patterns [3,11,18]. Among the pathways showing potential Tissues were thawed and homogenized (Polytron, Brink-alterations from neonatal DFMO treatment, catecholamine mann Instruments, Westbury, NY) in 39 volumes of ice-systems stand out as prominent candidates [2,11,13,18,21]. cold buffer containing 145 mM NaCl, 2 mM MgCl , and2

Accordingly, we have concentrated on the effects of 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5). Homogenates were sedimented at DFMO onb-adrenergic receptors and their transduction of 40 0003g for 15 min. The pellets were washed twice,

cell signals through the adenylyl cyclase signaling path- resuspended (Polytron) in homogenization buffer followed way, comparing effects in the cerebellum to structurally by resedimentation, and were then dispersed with a unaffected regions [4,5,17,25]. homogenizer (smooth glass fitted with a Teflon pestle) to achieve a final protein concentration of 1.25 mg / ml in a buffer consisting of 250 mM sucrose, 2 mM MgCl , 502

125

2. Materials and methods mM Tris (pH 7.5). [ I]Iodopindolol (final concentration

of 67 pM; specific activity 2200 Ci / mmol; New England

2.1. Animal treatments Nuclear Corp., Boston, MA) was incubated with|125mg

of membrane protein in a medium of 145 mM NaCl, 2 mM Studies were carried out in accordance with the declara- MgCl , 1 mM Na ascorbate, 20 mM Tris (pH 7.5), for 202

tion of Helsinki and with the Guide for the Care and Use min at room temperature in a total volume of 250 ml.

of Laboratory Animals as adopted and promulgated by the Incubations were stopped by dilution with 3 ml of ice-cold National Institutes of Health. Fifteen litters of Sprague– buffer, and the labeled membranes were trapped by rapid Dawley rats were given subcutaneous injections of DFMO vacuum filtration onto Whatman GF / C filters, which were (500 mg / kg) on postnatal days 5–12 while another 15 then washed with additional buffer and counted by liquid litters received equivalent volumes of vehicle (isotonic scintillation spectrometry. Non-specific binding (displace-saline). Animals were weaned, housed separately by ment by 100mM isoproterenol; Sigma Chemical Co., St. gender, and allowed to reach approximately 6 months of Louis, MO) was generally about 10% of total binding. age before assays were conducted. Animals were selected

such that each litter contributed no more than one male and 2.3. Adenylyl cyclase activity one female rat. The DFMO regimen used here has been

for b-receptor binding. The membrane preparations were measure, since for each sample, all four measures were diluted 20-fold with 250 mM sucrose, 1 mM EGTA and 10 evaluated in the same membrane preparation). When the mM Tris (pH 7.4) prior to the assay. Aliquots of mem- initial test identified interactions of treatment with other brane preparation containing 30 mg of protein were variables, lower-order ANOVAs were then conducted, incubated for 10 min at 308C with final concentrations of followed by post hoc analysis (Fisher’s Protected Least 100 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.4), 10 mM theophylline, 1 mM Significant Difference) to identify individual variables for adenosine 59-triphosphate, 10 mM guanosine 59-triphos- which the DFMO group differed significantly from the phate, 10 mM MgCl , 1 mg / ml of bovine serum albumin,2 controls; however, where interactions were not detected, and a creatine phosphokinase-ATP-regenerating system main effects are reported without post hoc analyses. For consisting of 10 mM sodium phosphocreatine and 8 IU convenience, results are presented as the percent change phosphocreatine kinase (all reagents from Sigma) in a total from control values; however, statistical determinations volume of 250ml. The enzymatic reaction was stopped by were performed on the original data. Main effects were placing the samples in a 90–1008C water bath for 5 min, considered significant at the level of P,0.05 and inter-followed by sedimentation at 30003g for 15 min, and the action terms at P,0.1 [23]; in the latter case, the signifi-supernatant solution was assayed for cAMP using radioim- cance was verified by identification of main effects at munoassay kits (Amersham Corp., Chicago, IL). Prelimin- P,0.05 with lower-order ANOVAs, after separation of the ary experiments showed that the enzymatic reaction was interactive factors.

linear well beyond the assay time period and was linear with membrane protein concentration; concentrations of

cofactors were optimal. 3. Results

Adenylyl cyclase activity was measured under several

different conditions. First, basal activity was evaluated. In control rats, there were substantial regional and Second, the maximal G-protein-linked response was evalu- gender-related differences in adenylyl cyclase activity ated in samples containing 10 mM NaF. Third, maximal (Table 1). Overall activity was lower in the brainstem than

21

total activity of the AC catalytic unit, independent of in the other two regions; the response to Mn , which receptors or G proteins, was evaluated with 10 mM MnCl2 causes maximal, direct activation of the enzyme was 5- to [10]. Finally, b-receptor-mediated effects were evaluated 10-fold in the cerebellum and cerebral cortex, but only with 100mM isoproterenol [19]. The concentrations of all 3-fold in the brainstem. Similarly, fluoride, which produces the agents used here have been found previously to be complete activation of G proteins, evoked only a 25–30% optimal for effects on AC and were confirmed in prelimin- increase in the brainstem, compared to 30–40% in the

ary experiments. cerebellum and 50–70% in the cerebral cortex. In contrast,

the response to isoproterenol, ab-receptor stimulant, was

2.4. Data analysis largest in the brainstem (25–40% increase, compared to

10–15% in the other regions). Across all three regions, Results are presented as means and standard errors. females showed higher adenylyl cyclase activities than Alterations caused by DFMO were first examined with a males (main effect of gender); the effect was most notice-global analysis of variance (ANOVA), incorporating all able in the cerebellum (P,0.007), whereas there was no variables: treatment, brain region and gender, and for significant gender difference in the brainstem and a

21

adenylyl cyclase, the four types of activities (a repeated difference only for the Mn response in the cerebral

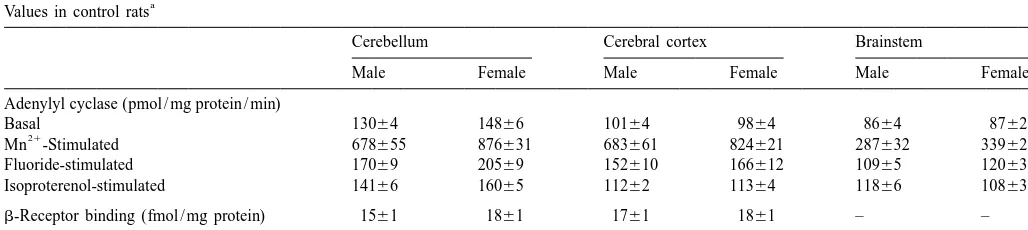

Table 1

a

Values in control rats

Cerebellum Cerebral cortex Brainstem

Male Female Male Female Male Female

Adenylyl cyclase (pmol / mg protein / min)

Basal 13064 14866 10164 9864 8664 8762

21

Mn -Stimulated 678655 876631 683661 824621 287632 339626

Fluoride-stimulated 17069 20569 152610 166612 10965 12063

Isoproterenol-stimulated 14166 16065 11262 11364 11866 10863

b-Receptor binding (fmol / mg protein) 1561 1861 1761 1861 – –

Weight (mg) 333613 30868 696622 640622 453615 412612

a

cortex. There was no significant regional or gender differ-ence forb-receptor binding in control rats but main effects of both variables were present for tissue weights.

Global statistical analyses of the effects of DFMO identified effects on adenylyl cyclase activity that were directed toward specific types of activity (treatment3

measure interaction) and that were gender selective (inter-action of treatment3gender3measure). Accordingly, re-sults for each type of adenylyl cyclase measurement are presented, separated by gender. In contrast, b-receptor binding did not show any significant treatment effects or interactions of treatment3other variables; brain region weights showed regionally dependent effects of DFMO (treatment3region interaction), without any gender selec-tivity (no interaction of treatment3gender or of treatment3gender3region).

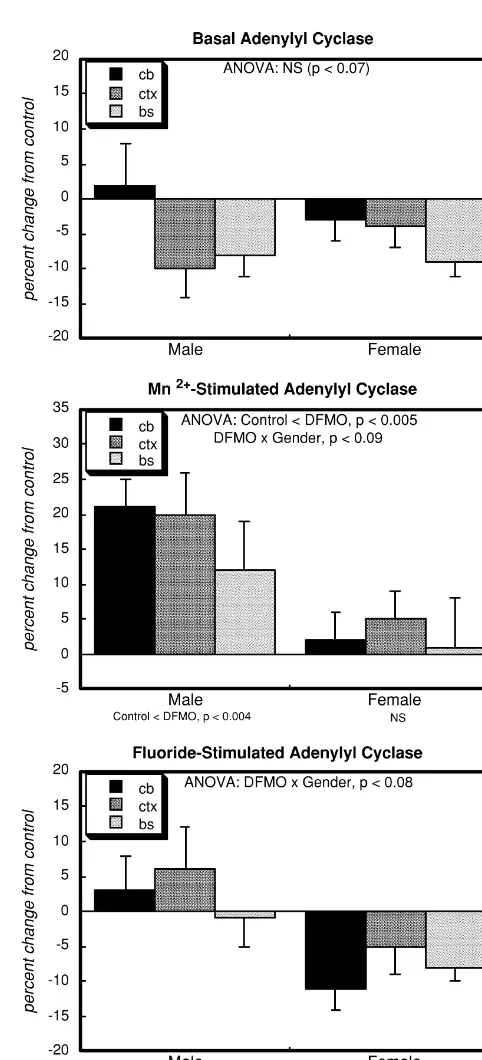

Across all three brain regions and both genders, basal adenylyl cyclase showed a trend (P,0.07) toward reduced activity in the DFMO group (Fig. 1, top panel). However,

21

total enzymatic activity, evaluated with Mn , indicated instead a significant overall elevation after neonatal DFMO treatment (middle panel), with a distinct gender selectivity (males.females). Although the effect was lower in the brainstem than in the other regions, it is difficult to ascribe regional significance, as there was no overall statistical difference among regions in the global test (Table 2). A reduction in basal adenylyl cyclase activity in the face of an increase in total enzymatic activity implies that DFMO is likely to affect cofactors that modulate the activity. Accordingly, we also evaluated the adenylyl cyclase response to fluoride, which evokes maximal association of the enzyme with G proteins (Fig. 1, bottom panel). DFMO treatment impaired the fluoride response, with a decided gender-dependence (significant deficits in females but not males).

Fluoride acts upon both stimulatory G proteins (G ) ands

inhibitory proteins (G ), so we next examined the responsei

to isoproterenol, which activates b-receptors that work predominantly through G . DFMO impaired the adenylyls

cyclase response to isoproterenol in both males and females (Fig. 2, top panel). However, given that DFMO

21

induced total adenylyl cyclase activity (Mn response) and altered overall G-protein signaling (fluoride response), we evaluated the effects on isoproterenol-stimulated activi-ty relative to the other two stimulants. Comparing the effects on b-receptor-mediated responses to total en-zymatic activity revealed profound deficits in the G -linkeds

receptor response, with a greater effect on males (middle 21

Fig. 1. Effects of neonatal DFMO administration on basal, Mn

-stimu-panel). The same pattern was seen when the isoproterenol lated and fluoride-stimulated adenylyl cyclase activity in brain regions of response was compared to that of fluoride (bottom panel): adult rats, presented as the percent change from control values (Table 1).

significant overall deficits with the greater loss seen in Data represent means and standard errors obtained from 8–10 animals for each gender. ANOVA across both genders appears at the top of each

males.

panel and separate evaluations for males and females are shown at the

Deficiencies in b-receptor cell signaling could also

bottom of the panel. Post hoc tests for each region were not carried out

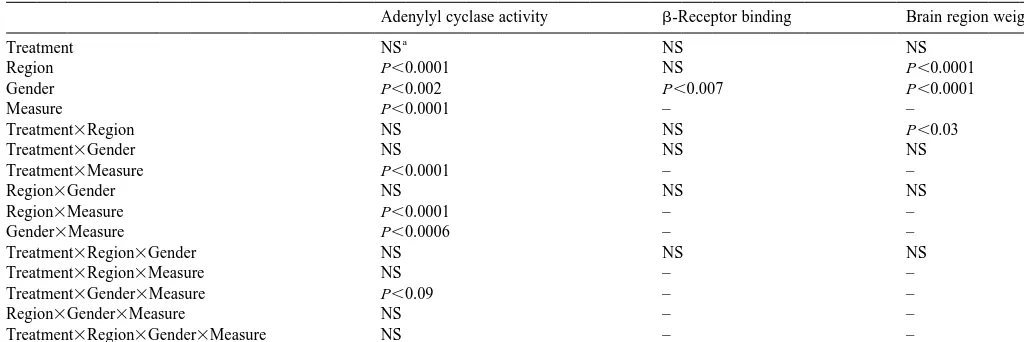

Table 2

Global statistical analyses

Adenylyl cyclase activity b-Receptor binding Brain region weight

a

Treatment NS NS NS

Region P,0.0001 NS P,0.0001

Gender P,0.002 P,0.007 P,0.0001

Measure P,0.0001 – –

Treatment3Region NS NS P,0.03

Treatment3Gender NS NS NS

Treatment3Measure P,0.0001 – –

Region3Gender NS NS NS

Region3Measure P,0.0001 – –

Gender3Measure P,0.0006 – –

Treatment3Region3Gender NS NS NS

Treatment3Region3Measure NS – –

Treatment3Gender3Measure P,0.09 – –

Region3Gender3Measure NS – –

Treatment3Region3Gender3Measure NS – –

a

NS, not significant.

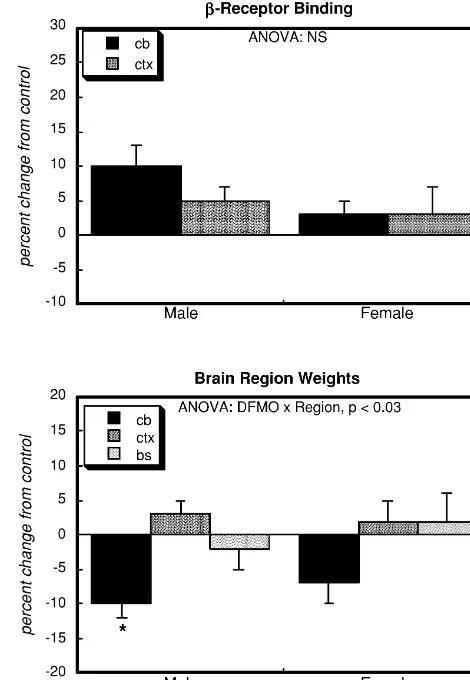

treatment increased receptor binding. The alterations in sensitive site of the enzyme [10]. If this were the only adenylyl cyclase signaling also did not correspond to effect, then all responses mediated through adenylyl regional growth impairment by DFMO (bottom panel). As cyclase should be equally enhanced; however, basal activi-expected from previous studies [1,5,16], growth impair- ty actually tended to be reduced, indicating that a defect in ment was limited to the cerebellum and showed no gender signaling exists upstream from adenylyl cyclase.

Approxi-selectivity. mately half of basal activity is actually dependent on

G-protein interactions with the enzyme, even in the absence of receptor stimulation [19,22]. Accordingly, we

4. Discussion next evaluated the response to fluoride, which stimulates

all G proteins maximally. There was no global increase as The present results indicate that the role of polyamines would be expected from the induction of adenylyl cyclase in brain development extends beyond the control of catalytic activity. Instead, activity was unchanged in males, general growth, to the programming of expression and / or and actually obtunded in females, suggesting that addition-function of specific signaling proteins involved in synaptic al gender-selective deficits reside in G-protein-coupled transmission. Although neonatal DFMO compromises the responses.

growth and structure of the cerebellum while sparing the Because fluoride activates both G and G , we also thens i

cerebral cortex and brainstem [1,5,16], effects on the evaluated the response to isoproterenol, which activates adenylyl cyclase signaling cascade were present in all three b-adrenergic receptors and thus stimulates adenylyl regions. Furthermore, although adverse changes in growth cyclase primarily through G . In this case, we identifieds

and morphology are shared by both males and females, the clear-cut deficiencies across both genders in the DFMO effects on signaling displayed distinct gender selectivity. group. Taking into account the fact that the loss of Accordingly, the DFMO-induced alterations in the func- response to isoproterenol occurs in the presence of gender-tioning of proteins in the adenylyl cyclase cascade are not selective induction of adenylyl cyclase, the deficit in the manifestations of impaired cerebellar growth, nor do they specific b-receptor mediated component was actually far represent a spreading of adverse effects to other regions more profound in males, as demonstrated by the sharp simply because they connect to cerebellar cells or cerebel- decline in the proportion of adenylyl cyclase activated by

21

lar function. It is therefore clear that even a brief de- b-receptor stimulation (the isoproterenol:Mn activity velopmental period of ODC inhibition exerts effects on ratio) or in the proportion of G proteins activated by the cellular signaling that are entirely distinct from those on receptors (isoproterenol:fluoride activity ratio). Indeed, the cell growth, and in turn, this implies that polyamines play deficiencies in G-protein-mediated responses are likely to a more specified role in the development of cell signaling. involve separate mechanisms in the two genders. In males, We obtained two main characteristics effects on the the deficits comprise loss of b-receptor coupling to G ,s

adenylyl cyclase signaling cascade: induction of adenylyl since the response to isoproterenol was reduced relative to cyclase activity itself, and interference with signaling that of fluoride, without a change inb-receptor binding; in mediated through G-protein-coupled receptors. Adenylyl addition, there are defects in G-protein coupling to cyclase induction was evident from the overall increase in adenylyl cyclase, demonstrated by the fact that the fluoride

21 21

Fig. 3. Effects of neonatal DFMO administration onb-receptor binding and on brain region weights, presented as the percent change from control values (Table 1). Data represent means and standard errors obtained from 5–10 animals for each gender. ANOVA across both genders appears at the top of each panel and separate evaluations for males and females are shown at the bottom of the panel. Post hoc tests for each region were carried out only for brain region weight, the only variable to show a significant interaction of treatment3region. cb, cerebellum; ctx, cerebral cortex; bs, brainstem.

cyclase. In females, the effects of DFMO are limited to the G-protein interaction with adenylyl cyclase. The response to fluoride was actually reduced despite adenylyl cyclase induction, implying a greater loss of G-protein function than in males; on the other hand, there was no further deficit in the response to isoproterenol, which simply mirrored the overall deficit in G-protein function (no effect on the isoproterenol:fluoride activity ratio). These results thus indicate that neonatal polyamine depletion can have vastly different effects on cell signaling in males and

Fig. 2. Effects of neonatal DFMO administration on

isoproterenol-stimu-females. Ultimately, these defects may contribute to

gen-lated adenylyl cyclase activity, and on isoproterenol stimulation relative

21 der-specific effects on behavior, and our results indicate

to Mn or fluoride-stimulated activity, presented as the percent change

from control values (Table 1). Data represent means and standard errors that selectivity may best be revealed by behavioral

re-obtained from 8–10 animals for each gender. ANOVA across both sponses that challenge receptor systems operating through genders appears at the top of each panel and separate evaluations for adenylyl cyclase.

males and females are shown at the bottom of the panel. Post hoc tests for

In conclusion, the role of polyamines in brain

develop-each region were not carried out because of the absence of significant

ment extends to expression or function of specific proteins

interactions of treatment3region or of treatment3region3gender. cb,

[12] C. Lau, R.J. Kavlock, Functional toxicity in the developing heart,

growth. Thus, effects on signaling extend to regions other

lung, and kidney, in: C.A. Kimmel, J. Buelke-Sam (Eds.),

De-than cerebellum, the only region whose growth is affected

velopmental Toxicology, 2nd edition, Raven, New York, 1994, pp.

by transient neonatal polyamine depletion [1,5,16]. The 119–188.

significance of these results extends beyond the effects of [13] C. Lau, T.A. Slotkin, Stimulation of rat heart ornithine

decarbox-DFMO. Perturbations of ODC activity and polyamines ylase by isoproterenol: evidence for post-translational control of enzyme activity?, Eur. J. Pharmacol. 78 (1982) 99–105.

have been identified for numerous suspected

neuro-[14] M.K. McMillian, S.M. Schanberg, C.M. Kuhn, Ontogeny of rat

teratogens [4,9,12,15,17], suggesting in these cases, too,

hepatic adrenoceptors, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 227 (1983) 181–

the effects on the ODC pathway may be mechanistically 186.

connected to lasting changes in synaptic function, even [15] W. Paschen, Polyamine metabolism in different pathological states

when growth and structure are apparently normal. The of the brain, Mol. Chem. Neuropathol. 16 (1992) 241–271. [16] L. Schweitzer, A.J. Robbins, T.A. Slotkin, Dendritic development of

ODC / polyamine system thus provides a potential

mech-Purkinje and granule cells in the cerebellar cortex of rats treated

anistic link between initial neuroteratogenic insults and the

postnatally with a-difluoromethylornithine, J. Neuropathol. Exp.

eventual functional outcome, rather than representing just a Neurol. 48 (1989) 11–22.

marker for perturbed growth and development. [17] T.A. Slotkin, J. Bartolome, Role of ornithine decarboxylase and the polyamines in nervous system development: a review, Brain Res. Bull. 17 (1986) 307–320.

[18] T.A. Slotkin, A. Grignolo, W.L. Whitmore, L. Lerea, P.A. Trepanier,

Acknowledgements

G.A. Barnes, S.J. Weigel, F.J. Seidler, J. Bartolome, Impaired development of central and peripheral catecholamine

neurotrans-This study was supported by USPHS HD-09713. mitter systems in preweanling rats treated witha -difluoromethylor-nithine, a specific irreversible inhibitor of ornithine decarboxylase, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 222 (1982) 746–751.

[19] T.A. Slotkin, D.B. Miller, F. Fumagalli, E.C. McCook, J. Zhang, G.

References

Bissette, F.J. Seidler, Modeling geriatric depression in animals: biochemical and behavioral effects of olfactory bulbectomy in [1] J.V. Bartolome, L. Schweitzer, T.A. Slotkin, J.V. Nadler, Impaired young versus aged rats, J. Pharmacol. Exp. Ther. 289 (1999)

development of cerebellar cortex in rats treated postnatally with 334–345.

a-difluoromethylornithine, Neuroscience 15 (1985) 203–213. [20] T.A. Slotkin, L. Orband-Miller, K.L. Queen, Development of

3

[2] J.V. Bartolome, P.A. Trepanier, E.A. Chait, T.A. Slotkin, Role of [ H]nicotine binding sites in brain regions of rats exposed to polyamines in isoproterenol-induced cardiac hypertrophy: effects of nicotine prenatally via maternal injections or infusions, J.

Phar-a-difluoromethylornithine, and irreversible inhibitor of ornithine macol. Exp. Ther. 242 (1987) 232–237.

decarboxylase, J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 14 (1982) 461–466. [21] T.A. Slotkin, W.L. Whitmore, L. Lerea, R.J. Slepetis, S.J. Weigel, [3] J.M. Bell, D.S. Madwed, T.A. Slotkin, Critical development periods P.A. Trepanier, F.J. Seidler, Role of ornithine decarboxylase and the for inhibition of ornithine decarboxylase by a-difluoromethylor- polyamines in nervous system development: short-term postnatal nithine: effects on ontogeny of sensorimotor behavior, Neuroscience administration ofa-difluoromethylornithine, an irreversible inhibitor 19 (1986) 457–464. of ornithine decarboxylase, Int. J. Dev. Neurosci. 1 (1983) 7–16. [4] J.M. Bell, T.A. Slotkin, Coordination of cell development by the [22] T.A. Slotkin, J. Zhang, E.C. McCook, F.J. Seidler,

Glucocorticoid-ornithine decarboxylase (ODC) / polyamine pathway as an underly- targeting of the adenylyl cyclase signaling pathway in the cere-ing mechanism in developmental neurotoxic events, Prog. Brain bellum of young vs. aged rats, Brain Res. 800 (1998) 236–244. Res. 73 (1988) 349–363. [23] G.W. Snedecor, W.G. Cochran, Statistical Methods, Iowa State [5] J.M. Bell, W.L. Whitmore, T.A. Slotkin, Effects of a-difluoro- University Press, Ames, IA, 1967.

methylornithine, a specific irreversible inhibitor of ornithine de- [24] X. Song, F.J. Seidler, J.L. Saleh, J. Zhang, S. Padilla, T.A. Slotkin, carboxylase, on nucleic acids and proteins in developing rat brain: Cellular mechanisms for developmental toxicity of chlorpyrifos: critical perinatal periods for regional selectivity, Neuroscience 17 targeting the adenylyl cyclase signaling cascade, Toxicol. Appl.

(1986) 399–407. Pharmacol. 145 (1997) 158–174.

[6] M. Davidson, K. Bedi, P. Wilce, Ethanol inhibition of brain ornithine [25] M. Sparapani, M. Virgili, M. Caprini, F. Facchinetti, E. Ciani, A. decarboxylase activity in the postnatal rat, Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 20 Contestabile, Effects of gestational or neonatal treatment with a -(1998) 523–530. difluoromethylornithine on ornithine decarboxylase and polyamines [7] S. Genedani, M. Bernardi, A. Bertolini, Developmental and be- in developing rat brain and on adult rat neurochemistry, Exp. Brain

havioral outcomes of perinatal inhibition of ornithine decarboxylase, Res. 108 (1996) 433–440.

Neurobehav. Toxicol. Teratol. 7 (1985) 57–65. [26] C.W. Tabor, H. Tabor, Polyamines, Annu. Rev. Biochem. 53 (1984) [8] J. Glowinski, L.L. Iversen, Regional studies of catecholamines in the 749–790.

3 3

rat brain. I. The disposition of [ H]norepinephrine, [ H]dopamine [27] M. Toraason, M.J. Breitenstein, R.J. Smith, Ethylene glycol

mono-3

and [ H]DOPA in various regions of the brain, J. Neurochem. 13 methyl ether (EGME) inhibits rat embryo ornithine decarboxylase (1966) 655–669. (ODC) activity, Drug Chem. Toxicol. 9 (1986) 191–203. [9] O. Heby, Role of polyamines in the control of cell proliferation and [28] K.D. Whitney, F.J. Seidler, T.A. Slotkin, Developmental

neuro-differentiation, Differentiation 19 (1981) 1–20. toxicity of chlorpyrifos: cellular mechanisms, Toxicol. Appl. Phar-[10] J.H. Hurley, Structure, mechanism, and regulation of mammalian macol. 134 (1995) 53–62.

adenylyl cyclase, J. Biol. Chem. 274 (1999) 7599–7602. [29] E.A. Zahalka, F.J. Seidler, J. Yanai, T.A. Slotkin, Fetal nicotine [11] L.S. Jones, L.L. Gauger, J.N. Davis, T.A. Slotkin, J.V. Bartolome, exposure alters ontogeny of M -receptors and their link to

G-1

Postnatal development of brain alpha -adrenergic receptors: in vitro1 proteins, Neurotoxicol. Teratol. 15 (1993) 107–115. 125