Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:18

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Student Engagement: Developing a Conceptual

Framework and Survey Instrument

Gerald F. Burch, Nathan A. Heller, Jana J. Burch, Rusty Freed & Steve A. Steed

To cite this article: Gerald F. Burch, Nathan A. Heller, Jana J. Burch, Rusty Freed & Steve A. Steed (2015) Student Engagement: Developing a Conceptual Framework and Survey Instrument, Journal of Education for Business, 90:4, 224-229, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1019821

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1019821

Published online: 25 Mar 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 354

View related articles

View Crossmark data

Student Engagement: Developing a Conceptual

Framework and Survey Instrument

Gerald F. Burch, Nathan A. Heller, Jana J. Burch, Rusty Freed,

and Steve A. Steed

Tarleton State University, Stephenville, Texas, USA

Student engagement is considered to be among the better predictors of learning, yet there is growing concern that there is no consensus on the conceptual foundation. The authors propose a conceptualization of student engagement grounded in A. W. Astin’s (1984) Student Involvement Theory and W. A. Kahn’s (1990) employee engagement research where student engagement is built on four components: emotional engagement, physical engagement, cognitive engagement in class, and cognitive engagement out of class. Using this framework the authors develop and psychometrically test a student engagement survey that can be used by researchers to advance engagement theory and by business schools to monitor continuous improvement.

Keywords: cognitive engagement, emotional engagement, engagement, engagement survey, physical engagement, student engagement

The need to investigate student engagement antecedents and outcomes is building. On one side, student engagement continues to be a business education focal point (e.g., Lund Dean & Jolly, 2012; Magni, Paolino, Cappetta, & Proser-pio, 2013) based on the significant relationship with learn-ing outcomes (Gellin, 2003; Pike & Kuh, 2005; Pike, Smart, & Ethington, 2012). On the other side, business schools associated with the Association to Advance Colle-giate Schools of Business (AACSB) face the added chal-lenge of demonstrating “continuous quality improvement” in engagement, to include student engagement (AACSB, 2013, p. 2). Business faculty are therefore challenged to find ways to measure student engagement to demonstrate continuous quality improvements, while simultaneously advancing student engagement research.

In this article we discuss the need to develop a stronger conceptual base for student engagement and offer a theoret-ically based, psychometrtheoret-ically proven student engagement scale that can be used at the class or course level. We use Astin’s (1984) Student Involvement Theory and Kahn’s (1990) employee engagement research to propose four the-oretically grounded student engagement factors: emotional

engagement, physical engagement, cognitive engagement in class, and cognitive engagement out of class. We con-clude the article with implications of this student engage-ment survey and provide recommendations for future studies to link student curriculum design and delivery to student engagement, and from student engagement to sig-nificant learning outcomes.

ISSUE IDENTIFICATION

Student engagement is often considered to be among the better predictors of student learning and development (Carini, Kuh, & Klein, 2006). As such, educators should refine their teaching by investigating engagement as a pri-mary contributor to learning outcomes (Pike, et al., 2012). Kuh (2003, p. 25) defines engagement as the time and energy students devote to educationally sound activities inside and outside of the classroom, and the policies and practices that institutions use to induce students to take part in these activities. However, this definition is not shared by all. Steele and Fullagar (2009) stated that there is no con-sensus on the conceptualization and the conceptual founda-tions of student engagement. This may be because recent student engagement research has been dominated by studies that focus on college activities that place university policies and practices related to college students as the focal point

Correspondence should be addressed to Gerald F. Burch, Tarleton State University, Department of Management, Box T0330, Stephenville, TX 76402, USA. E-mail: gburch@tarleton.edu

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1019821

(National Survey of Student Engagement, 2004, 2005). Hu and Wolniak (2010) stated that “the effort by National Survey of Student Engagement (NSSE) has made it an axiom that what matters in student outcomes is student engagement in college activities (Kuh, 2003)” (p. 751). This approach places more student engagement responsibil-ity on administrators and less on instructional faculty.

The NSSE has a designed purpose, but it may not be the best instrument for evaluating student engagement. The purpose of the NSSE is reported to be twofold (Gonyea & Kuh, 2009): to determine the amount of time and energy students put into education and related activities and to evaluate how institutions use resources to encourage stu-dents to engage in activities that increase the student’s learning experience. However, there are difficulties in using the NSSE to investigate student engagement. First, the NSSE was developed to compare universities to one another and therefore aggregates student engagement to the college/university level, thereby making it impossible to investigate course/class level engagement. This aggregation affects educators, business schools, and researchers. Educa-tors need to evaluate how class elements affect student engagement, business colleges require course and class engagement data to demonstrate continuous improvement, and researchers require more granular data to make general-ized conclusions about the instruction to engagement and engagement to learning relationships. Steele and Fullagar (2009) stated that the NSSE is the most pervasive attempt to study student engagement and is “too broad in scope and is a survey of student educational experiences more than a theoretical explanation of student engagement” (p. 5). Based on these claims, we investigated the appropriateness of using decades of employee engagement research by assuming the job of a student is to learn.

CONCEPTUAL GROUNDING

Our desire to develop a theory-based student engagement survey revealed two theoretical approaches currently being used by student engagement researchers. The first adopts theories primarily derived in learning and education, and the second is more firmly grounded in management theory. We propose that an appropriate conceptual framework may exist by combining the two approaches.

Student Involvement Theory (Astin, 1984) claims that educational policies and practices lead to student involve-ment (investinvolve-ment of psychological and physical energy) resulting in student learning and personal development. According to Astin, involvement is the investment of physi-cal and psychologiphysi-cal energy and student learning and per-sonal development are directly proportionate to the quantity and quality of involvement. The NSSE relies heavily on Student Involvement Theory.

Steele and Fullagar (2009) initiated the move away from the education-based theories by using Csikszentmihalyi’s (1975, 1990) flow theory and the Job Characteristics Model (Hackman & Oldham, 1980) to investigate the facilitators and outcomes of student engagement. The results of their empirical study show support for this move in education settings. We propose that selecting only education or man-agement theories may limit the knowledge and understand-ing associated with both disciplines. Student Involvement Theory (Astin, 1984) provides considerable explanation for student engagement, but it needs to be combined with man-agement theory. Kahn (1990) argued that engaged employ-ees were those that were willing to invest emotional, physical, and cognitive resources in the performance of their roles. Education researchers have supported this con-ception of engagement containing three components where cognitive engagement is displayed during the performance of the activity, emotional engagement is demonstrated through enjoyable states of mind, and physical arousal or innervation is displayed through physical engagement (Csikszentmihalyi, 1990; Jackson & Marsh, 1996; Steele & Fullagar, 2009). Using this framework, we propose investi-gating student engagement by using Kahn’s (1990) engage-ment components of emotional, physical, and cognitive investments. Returning to education theory, we propose that cognitive engagement may occur either in class or out of class and, therefore, we propose four distinct student engagement factors:

Hypothesis 1(H1): Student engagement consists of the sep-arate constructs of emotional engagement, physical engagement, cognitive engagement in class, and cogni-tive engagement out of class.

STUDY 1: SURVEY DEVELOPMENT AND PILOT TEST

The goal of this study was to develop a student engagement scale to measure the four proposed student engagement fac-tors. After developing the survey, a pilot test was conducted and exploratory factor analysis was used to determine if the items represented the desired constructs.

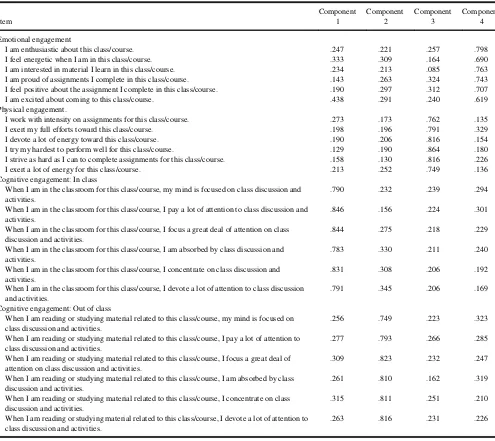

Survey Development

We modified the Rich, LePine, and Crawford (2010) 18-item employee engagement scale to develop the initial sur-vey. The Rich et al. scale consists of six items for three fac-tors (emotional, physical, and cognitive). We changed the context of the items to ensure students responded to their level of engagement toward a particular course or instructor and separated cognitive engagement into an in-class and out-of-class component. The 24 items are listed in Table 1.

STUDENT ENGAGEMENT 225

Participants and Procedure

The survey was administered to 214 undergraduate students at a mid-sized university in the southern United States dur-ing the last two weeks of the fall semester, 2013. The respondent’s average age was 21.7 years (s D 4.2 years),

53% were women, and 27.6% were minorities. All partici-pants voluntarily rated their level of student engagement.

Results

An exploratory factor analysis with varimax rotation was conducted for the pilot survey. The eigenvalues and scree plot suggest the four-component model is appro-priate. Factor loadings are presented in Table 1, while

eigenvalues and percent variance explained by each component is represented in Table 2. The results from the pilot test show that all six items from cognitive engagement in class loaded to component 1 (eigenvalue

D 13.47, 56.1% variance explained), all six items from

cognitive engagement out of class loaded to component 2 (eigenvalue 2.36, additional 9.8% variance explained), all six items from physical engagement loaded to com-ponent 3 (eigenvalue D 1.76, additional 7.3% variance

explained), and the six emotional engagement items loaded to component 4 (eigenvalue D 1.51, additional

6.3% variance explained). Coefficient alphas for the four components were all above the recommended .7 threshold: emotional engagement, .91; physical engage-ment, .93; cognitive in class, .96; and cognitive out of

TABLE 1

Burch Engagement Survey for Students (BESS) Factor Loadings

Item

Component 1

Component 2

Component 3

Component 4

Emotional engagement

I am enthusiastic about this class/course. .247 .221 .257 .798

I feel energetic when I am in this class/course. .333 .309 .164 .690

I am interested in material I learn in this class/course. .234 .213 .085 .763 I am proud of assignments I complete in this class/course. .143 .263 .324 .743 I feel positive about the assignment I complete in this class/course. .190 .297 .312 .707

I am excited about coming to this class/course. .438 .291 .240 .619

Physical engagement.

I work with intensity on assignments for this class/course. .273 .173 .762 .135

I exert my full efforts toward this class/course. .198 .196 .791 .329

I devote a lot of energy toward this class/course. .190 .206 .816 .154

I try my hardest to perform well for this class/course. .129 .190 .864 .180

I strive as hard as I can to complete assignments for this class/course. .158 .130 .816 .226

I exert a lot of energy for this class/course. .213 .252 .749 .136

Cognitive engagement: In class

When I am in the classroom for this class/course, my mind is focused on class discussion and activities.

.790 .232 .239 .294

When I am in the classroom for this class/course, I pay a lot of attention to class discussion and activities.

.846 .156 .224 .301

When I am in the classroom for this class/course, I focus a great deal of attention on class discussion and activities.

.844 .275 .218 .229

When I am in the classroom for this class/course, I am absorbed by class discussion and activities.

.783 .330 .211 .240

When I am in the classroom for this class/course, I concentrate on class discussion and activities.

.831 .308 .206 .192

When I am in the classroom for this class/course, I devote a lot of attention to class discussion and activities.

.791 .345 .206 .169

Cognitive engagement: Out of class

When I am reading or studying material related to this class/course, my mind is focused on class discussion and activities.

.256 .749 .223 .323

When I am reading or studying material related to this class/course, I pay a lot of attention to class discussion and activities.

.277 .793 .266 .285

When I am reading or studying material related to this class/course, I focus a great deal of attention on class discussion and activities.

.309 .823 .232 .247

When I am reading or studying material related to this class/course, I am absorbed by class discussion and activities.

.261 .810 .162 .319

When I am reading or studying material related to this class/course, I concentrate on class discussion and activities.

.315 .811 .251 .210

When I am reading or studying material related to this class/course, I devote a lot of attention to class discussion and activities.

.263 .816 .231 .226

class, .96. Study 1 thereby supported our hypothesis that engagement is composed of four distinct factors.

STUDY 2: FOUR-FACTOR MODEL VALIDATION

The purpose of Study 2 was to confirm the hypothesized four engagement factors were appropriate for the student engagement survey. The 24-item survey was administered to a second group of undergraduate students and confirma-tory factor analysis was used to compare the four-factor stu-dent engagement model to simplified models.

Participants and Procedure

Participants were 354 undergraduate students at a mid-sized university in the southern United States. Respondent’s aver-age aver-age was 20.1 years (sD3.2 years), 56% were women,

and 27.8% were minorities. All participants voluntarily rated their level of student engagement.

Results

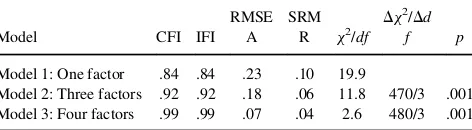

The proposed four-factor model was compared to a one-factor and three-one-factor model using the two-step approach recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988). The results from the structural equation modeling (LISREL 9.1; J€oreskog & S€orbom, 2013) are presented in Table 3. The first model evaluated a one-factor student engagement con-struct where all 24 items loaded on to one concon-struct (student

engagement). Model two contained three factors (emo-tional, physical, and cognitive), where cognitive engage-ment included the six items from engageengage-ment in class and six items for engagement out of class. The third model is the hypothesized four-factor model.

Several recommended goodness of fit measures were analyzed, including comparative fit index (CFI), incremen-tal fit index (IFI), root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), standardized root mean square residual (SRMR), and ratio of chi square relative to the degrees of freedom (L. Hu & Bentler, 1999). The following guidelines for evaluating the acceptability of model fit were used: CFI and IFI values above .90; RMSEA values close to .05; SRMR values less than .08 (Bentler, 1990; Bollen, 1989; L. Hu & Bentler, 1999; Kline, 2011), and the ratio of chi square to degrees of freedom (x2/df) less than 5 (Wheaton,

Muthen, Alwin, & Summers, 1977).

The one-factor model showed unacceptable fit where all fit indices were outside acceptable limits: CFI (.84), IFI (.84), RMSEA (.23), SRMR (.10), and x2/df (19.9). The

three-factor model showed improvement over the one-fac-tor model, but still had unacceptable limits for RMSEA (.18) and x2/df (11.8). The four-factor model fit indices

were all acceptable: CFI (.99), IFI (.99), RMSEA (.07), SRMR (.04), and x2/df (2.6). Based on these results, and

the chi-square difference test between the four-factor and other models (Dx2D480,dfD3), the one-and three-factor

models are rejected in favor of a four-factor model of stu-dent engagement, thereby supportingH1.

GENERAL DISCUSSION

Our contribution to engagement research is twofold. First, our two studies have demonstrated that engagement is not a single-dimension construct. Students can be emotionally engaged, physically engaged, cognitively engaged in class, or cognitively engaged out of class. Understanding these four factors can help educators engage students. However, we propose that the greatest contribution of this research is the development of a student engagement survey that is the-oretically grounded and psychometrically validated. Mea-suring student engagement at the class or course level is critical to developing strong curricula and improving deliv-ery techniques. It is our desire that this new survey will advance class and course engagement research and practice as quickly as the NSSE has advanced institutional engage-ment research.

Implications for Theory

Student engagement research should consider student engagement at the classroom and course level to directly identify antecedents, moderators, and outcomes associated with learning. We propose grounding student engagement

TABLE 3.

Results of Stage 2 Confirmatory Factor Analysis (ND354)

Model CFI IFI

Model 2: Three factors .92 .92 .18 .06 11.8 470/3 .001 Model 3: Four factors .99 .99 .07 .04 2.6 480/3 .001

Note: CFI D comparative fit index; IFI D incremental fit index;

RMSEADroot mean square error of approximation; SRMRD

standard-ized root mean square residual.

TABLE 2

Student Engagement Survey Factor Loadings

Initial eigenvalues Rotation sum of squares loadings

Component

1 13.47 56.13 56.13 5.15 21.44 21.44

2 2.36 9.83 65.95 4.99 20.77 42.21

3 1.76 7.33 73.28 4.79 19.97 62.18

4 1.51 6.31 79.58 4.18 17.40 79.58

STUDENT ENGAGEMENT 227

in Student Involvement Theory (Astin, 1984) and Kahn’s (1990) employee engagement research increases the likeli-hood of developing research that allows educators to improve student learning. With a solid measure of engage-ment, researchers can test the relationships between antece-dents and all four student engagement factors. It is expected that some antecedents will have greater influence on physical or emotional engagement, while others may drive cognitive engagement in or out of class. Obvious antecedents that should be investigated are classroom envi-ronment, learning activities, group projects, teaching style, delivery methods, and course material. The investigation of these antecedents could expose moderators of the relation-ship between antecedents and engagement. Potential mod-erators could be personal learning preferences (e.g., Kolb, 1984), classroom demographics, group engagement factors, longitudinal factors, and generational factors. Simply open-ing the door to the study of personal differences may iden-tify factors that can serve as the basis for a discipline based, prescriptive approach to teaching and learning.

Practical Implications

According to AACSB Standard 13 (AACSB, 2013), busi-ness schools must “show clear evidence of significant active student engagement in learning” (p. 37). Student engagement monitoring may therefore mirror current assur-ance of learning programs, where student engagement is measured at the course level and aggregated to a level where continuous process improvement goals can be estab-lished and monitored. Our survey could allow universities to quickly monitor student engagement in specific courses, make changes to curriculum design and delivery, and track related outcomes. These steps, combined with the measure-ment of outcomes, results in a continuous improvemeasure-ment cycle, which leads to higher order learning and better pre-pared students.

Future Research

We believe that future researchers should investigate how the class environment affects engagement and how engage-ment influences learning. It is expected that class activities such as simulations, games, and other active learning activi-ties may strongly influence physical engagement. Similarly, group projects, team teaching, individual projects, and homework increase student cognitive engagement out of the class. Emotional and cognitive engagement in class may be also be related to group activities. Researchers should investigate these relationships to help instructors further engage students.

Our study only assessed face-to-face instruction. Future research should investigate the difference between face-to-face, online, hybrid, and flipped classes to determine if stu-dent engagement differences exist based on mode of

delivery. Subsequent research could begin to determine the importance of how each class activity affects student engage-ment based on the delivery mode. In particular, we expect emotional engagement to be dependent on the quantity and quality of contact between students and instructors. Online instruction and instruction in large classes significantly reduce the potential for quality interactions which have been shown to increase engagement (Klem & Connell, 2004).

A second area for future researchers to investigate is how student individual differences affect the class environ-ment to engageenviron-ment and engageenviron-ment to learning process. Individual personality, age, gender, ethnicity, race, apti-tude, ability, motivation, prior experience, learning style, and learning preference all have the ability to affect student engagement. These differences may affect the four student engagement factors differently. Looking at the student as an employee may also significantly open doors to use man-agement research to investigate student actions. It is expected that students may perform their role of student in a manner similar to that of an employee. Management con-structs of organizational commitment, intention to quit, psychological contracts, as well as dozens of others may help explain student engagement behaviors.

CONCLUSION

Educators have both the desire and requirement to facilitate student learning. In the past, educators have altered course curriculum and delivery based on qualitative data to increase student engagement and student learning. In this study we provided a theoretically grounded student engage-ment scale and then psychometrically validated the measure using two separate studies. We propose that educators can use this scale to measure student emotional engagement, physical engagement, cognitive engagement in class, and cognitive engagement out of class. Educators that use the results from this analysis could systematically alter the learning environment with classroom activities that com-plement individual differences and lead to highly engaged students.

On the other hand, student engagement research has suf-fered from the lack of theoretically grounded support for the underlying factors that affect student learning. The results of our four-factor model of student engagement pro-vide empirical epro-vidence that student engagement is not a single component. Students can be emotionally engaged, physically engaged, cognitively engaged in class, or cogni-tively engaged out of class. These four factors enable researchers to further investigate the link between the class-room and engagement and from engagement to learning. We propose that this new model of student engagement will allow business schools to track engagement at the class and course level and provide the details needed to develop continuous improvement programs for student engagement.

REFERENCES

Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach.Psychological Bulletin,103, 411–423.

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2013). Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards for business accredi-tation. Tampa, FL: Author.

Astin, A. W. (1984). Student involvement: A developmental theory for higher education.Journal of College Student development,25, 297–308. Astin, A. W. (1993).Assessment for excellence: The philosophy and prac-tice of assessment and evaluation in higher education. Phoenix, AZ: American Council for Education and Oryx Press.

Bentler, P. M. (1990). Comparative fit indexes in structural models. Psy-chological Bulletin,107, 238–246.

Bollen, K. A. (1989).Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: Wiley Interscience.

Carini, R. M., Kuh, G. D., & Klein, S. P. (2006). Student engagement and stu-dent learning: Testing the linkages.Research in Higher Education,47, 1–32. Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1975).Beyond boredom and anxiety. San Francisco,

CA: Jossey-Bass.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990).Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

Gellin, A. (2003). The effect of undergraduate student involvement in criti-cal thinking: A meta-analysis of the literature, 1991–2000.Journal of College Student Development,44, 746–762.

Gonyea, R. M., & Kuh, G. D. (2009). NSSE, organizational intelligence and the institutional researcher. New Directions for Institutional Research,141, 107–113.

Hackman, J. R., & Oldham, G. R. (1980).Work redesign. Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struc-tural Equation Modeling,8, 1–55.

Hu, S., & Wolniak, G. C. (2010). Initial evidence on the influence of col-lege student engagement on early career earnings.Research in Higher Education,51, 750–766.

Jackson, S. A., & Marsh, H. W. (1996). Development and validation of a scale to measure optimal experience: The Flow State Scale.Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology,18, 17–35.

J€oreskog, K. W., & S€orbom, D. (2013).LISREL for Windows[Computer software], Skokie, IL: Scientific Software International.

Kahn, W. A. (1990). Psychological conditions of personal engagement and disengagement at work.Academy of Management Journal,33, 692–724. Klem, A. M., & Connell, J. P. (2004). Relationships matter: Linking teacher support to student engagement and achievement. Journal of School Health,74, 262–273.

Kline, R. B. (2011).Principles and practice of structural equation model-ing(3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guilford.

Kolb, D. A. (1984).Experiential learning. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall.

Kuh, G. D. (2003). What we’re learning about student engagement from NSSE.Change,35, 24–31.

Lund Dean, K., & Jolly, J. P. (2012). Student identity, disengagement, and learning.Academy of Management Learning & Education,11, 228–243. Magni, M., Paolino, C., Cappetta, R., & Proserpio, L. (2013). Diving too deep: How cognitive absorption and group learning behavior affect indi-vidual learning.Academy of Management Learning and Education,12, 51–69.

National Survey of Student Engagement. (2004). Student engagement: Pathways to collegiate success. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research.

National Survey of Student Engagement. (2005). Student engagement: Exploring different dimensions of student engagement. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Center for Postsecondary Research.

Pike, G. R., & Kuh, G. D. (2005). A typology of student engagement for American colleges and universities.Research in Higher Education,46, 185–210.

Pike, G. R., Smart, J. C., & Ethington, C. A. (2012). The mediating effects of student engagement on the relationships between academic disci-plines and learning outcomes: An extension of Holland’s Theory. Research in Higher Education,53, 550–575.

Rich, B. L., LePine, J. A., & Crawford, E. R. (2010). Job engagement: Antecedents and effects on job performance.Academy of Management Journal,53, 617–635.

Steele, J. P., & Fullagar, C. J. (2009). Facilitators and outcomes of student engagement in a college setting.The Journal of Psychology,142, 5–27. Wheaton, B., Muthen, B., Alwin, D., & Summers, G. (1977). Assessing

reliability and stability in panel models. In D. Heise (Ed.),Sociological methodology(pp. 84–136). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

STUDENT ENGAGEMENT 229