P

ARENTS

’ J

OBS

A

FFECT

Y

OUNG

P

EOPLE

BARBARAPOCOCK AND JANECLARKE∗

T

his paper examines the perspectives of young people about their parents’ paid and unpaid work, their preferences for time or money through more parental work, and their views about how their parents’ jobs affect them. It analyses qualitative empirical data collected in Australia in late 2003, by means of focus groups among 10–12 and 16–18-year-old males and females in urban and rural locations in two Australian states, in both high and low socioeconomic areas. It finds that more Australian children are looking for more time from parents than more money from more parental work, though this varies by income level, location and parental hours. This preference for ‘time over more money’ is consistent in single- and dual-earner couple households as well as sole parent/earner households. Children are acute observers of parents and their jobs. Both positive and negative spillovers are widely observed. Negative spillovers from long or unsocial hours are especially marked, reinforcing other findings in support of policy interventions to contain long or unsocial hours.INTRODUCTION

Changes in patterns of paid and unpaid work, workplaces, and household shape have been the subject of much recent analysis in Australia (HILDA 2001; Campbell 2002; Megalogenis 2003; Pocock 2003; Pusey 2003; Summers 2003; Tanner 2003; Watson, Buchanan, Campbell & Briggs 2003). They are driving a lively policy and political interest in the work and family ‘collision’ and gov-ernment responses to it, though action is slower to follow. The perspective of children is missing from these accounts, yet is relevant to industrial, workplace and household perspectives. Parents, in particular, act on certain assumptions about children’s welfare as they determine household patterns of participation in paid and unpaid work.

Whereas there has been some international research on the specific issue of parental work patterns and children’s views of them, there has been very little in Australia with the exception of Lewis, Tudball and Hand (2001). Galinsky (1999) argues, based on her large US study, that the ‘work/family’ debate has been mis-framed with too much focus on whether working mothers in particular are ‘bad’ for children, rather than how work affects parents, and through them, children. In the USA, the real question about parental work is ‘howparent’s work’, and how attentive or focused they are able to be towards their children when they are with them. Galinsky found that older children longed for more parental time, especially with their fathers. These older children looked for ‘hang around time’

∗School of Social Sciences, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, SA, 5005. Australia.

Email: Barbara.Pocock@adelaide.edu.au

more than younger children. She argues that thenatureof parents’ jobs is very im-portant to children who are very alert to parental moods. This result is confirmed by Nasman’s study of Swedish children about parental work which found that work affects parents’ ‘state and physical conditions’. This ‘colouring’ spills over to family life, overriding the idea of work and family as separate social spheres’ (2003: 51). This spillover was higher for parents with irregular or long hours and for single mothers, and manifested itself most obviously through parental fatigue. In a Scottish study McKee, Mauthner and Galilee (2003) found that children were profoundly aware of their parents’ work and its effects: they could ‘competently assess how work made their parents feel’ (2003: 39) and many wanted to avoid the stress arising from external control of work in their own future lives.

In Australia, Lewis, Tudball and Hand (2001) undertook interviews with a non-random group of parents and children from 47 Melbourne families (71 children over eight years old). The majority of children in the study felt that their parents worked ‘about the right amount of time’ and that—in accord with Galinsky’s work—‘it is not whether and how much parents work, but how they work and how they parent, that matters’ (2001: 23). Responses were divided ‘roughly evenly between those saying that they wished their parents spent more time with them and those who said their parents currently spent enough time with them’ (2001: 24). Only two parents in Lewiset al.’s study worked more than 50 hours a week. This Australian and international literature mostly addresses the question of spillover from parental work onto children. This paper addresses several ques-tions. First, how do young people perceive the time/work patterns and trade-offs in their households? Second, how do young Australians perceive spillover from their parents’ jobs? Third, do these perceptions vary in relation to household income, locations, household types, and different patterns of parental working hours? Do young people with a parent at home also experience spillover from that domestic form of work? Finally, how do these experiences and perceptions affect their own plans for the future?

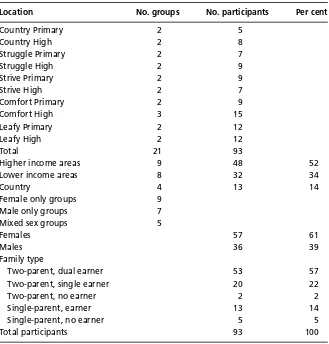

The analysis considers the perceptions of a group of young Australians at school in Year 6 (10–12 years old) and Year 11 (16–18 years old) (Pocock and Clarke 2004, and Pocock 2004 report more fully). We conducted 21 focus groups in two cities (eight in Sydney, nine in Adelaide and four in rural South Australia) in late 2003. The city schools were selected from a stratified sub-group of schools selected from the two states, in high and low socio-economic groups based on their score on the Index of Relative Socio-Economic Disadvantage (one of the five measures of disadvantage published by the ABS). We call the higher-income schools ‘Leafy’ (northern Sydney) and ‘Comfort’ (southern Adelaide), the lower-income schools ‘Strive’ (western Sydney) and ‘Struggle’ (northern and western Adelaide), and the country school ‘Country’. The average size of focus groups was four, and most were separate-sex focus groups. All were age specific. The participants are over-representative of males and higher-income areas, and children living with employed parents. They are fairly representative by household type (breadwinner, dual earner, single parent, blended).

one-on-one interviews with strangers. Further, we were interested in hearing young people in conversation with each other about these issues, as well as hearing their individual views in detail. Focus groups allowed in-depth consideration and probing of issues and allowed new questions to surface. Each person was asked their individual view on key issues, and the focus groups were attended by both a note taker and facilitator and they were taped and transcribed. This allowed us to identify each response by speaker, and to analyse their views by family type, income and so on. The data were analysed by theme from the transcripts. Table 1 sets out the characteristics of interviewees.

Forty-three of the 93 lived-in households where children identify (without prompting) long or unsocial hours as a significant issue affecting their parents (and them). This may be an over-representation of children with a parent working long or unsocial hours. However, it may not be, given that we are referring to both longorunsocial hours, and given the rise in the proportion of Australian workers who now work more than 45 hours a week (26 per cent in 2000 (Campbell 2002)).

Table 1 Focus group details

Location No. groups No. participants Per cent

Country Primary 2 5

Country High 2 8

Struggle Primary 2 7

Struggle High 2 9

Strive Primary 2 9

Strive High 2 7

Comfort Primary 2 9

Comfort High 3 15

Leafy Primary 2 12

Leafy High 2 12

Total 21 93

Higher income areas 9 48 52

Lower income areas 8 32 34

Country 4 13 14

Female only groups 9

Male only groups 7

Mixed sex groups 5

Females 57 61

Males 36 39

Family type

Two-parent, dual earner 53 57

Two-parent, single earner 20 22

Two-parent, no earner 2 2

Single-parent, earner 13 14

Single-parent, no earner 5 5

Most children now live with two earners who each have a one in four chance of working long hours. The study group includes a dozen children who lived with at least one self-employed parent (ten of whom worked long or unsocial hours). Children in the study described their parent’s hours with convincing precision, even where they did not know their parent’s occupation. The impact of these long or unsocial hours on the views of young people in this study is consistent and strong.

The discussion below falls into three sections: firstly consideration of young people’s preferences between time with parents and money from more parental work; secondly their perceptions about how parents’ jobs affect them; and finally some discussion of the implications for policy, action and theory.

TIME VERSUS MONEY: YOUNG PEOPLE’S PREFERENCES

In most households, parents’ jobs are valued by young people and understood as a necessity. For some in lower-income areas in particular they are specifically valued for the stability and security that they bring. Young people are well aware of the need to earn and fully support it. Overall, however, more young people in this study show a preference for more time with their parents, over more earnings and less time with parents.

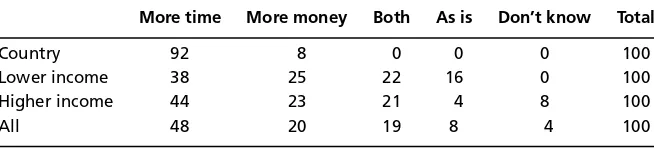

We asked participants:‘If you could choose to have more time with your parents on the one hand, or more money because they worked more, which would you choose?’Almost half of all 93 children would prefer more time with their parents, a fifth would prefer more money, and many couldn’t decide between them, saying ‘both’ (see table 2). Less than a tenth said that they liked things as they were, in contrast with the results found by Lewiset al.(2001). It is interesting that only four young people said they didn’t know. The preference for money was stronger in Sydney, and weaker in Adelaide and the country. Those in lower income areas preferred more money over more time. They were concerned about financial pressure and the need to have money to pay bills and mortgages. However, even in lower income areas, over a third of young people chose more time over more money, and only a quarter unambiguously chose more money. More of them wanted to keep things ‘as is’ than in higher-income areas. Many in both low- and higher-income areas wanted both, if only they could have them.

These results must be interpreted with caution. They are indicative of the views of the 93 young people in our focus groups, rather than reliable indicators for the larger population. However, they are suggestive of a significant preference

Table 2 Young people’s preferences for more time with parents or more money

More time More money Both As is Don’t know Total

Country 92 8 0 0 0 100

Lower income 38 25 22 16 0 100

Higher income 44 23 21 4 8 100

for more time in the minds of many young people—even those located in less financially comfortable areas.

Beneath this picture lies a much more complex story. Where children felt they had enough time with parents, they often chose more money: Andre from Leafy Primary put it like many others: ‘I’d probably choose more money because I can see my parents basically whenever I want. My Mum [an architect] doesn’t do that much work and my Dad [an artist] is at home’. A fifth wanted both: Charlie at Leafy High wanted more time with his father (‘I don’t really see my Dad’), and more money because he sees his parent’s employment in the entertainment industry as unpredictable. Like many others, his ‘both’ answer reflects his view that he sees enough of one parent (like most, his mother) and not enough of his father. Brittany at the same school finds it hard to choose: she likes it ‘the way it is. I would like to see my Dad more ‘cause I don’t see my Dad’.

In Adelaide households that are financially comfortable, and households in the country, more young people preferred time with their parents, over more money. In households feeling financial pressure, in Struggletown (northern or western Adelaide) or Strivetown (western Sydney), views were pretty evenly split. Money mattered more than in comfortable areas, but—despite financial pressure—a fair number of young people wanted more time with their parents. Many mentioned specific money pressures like meeting loan repayments and the bills. Some would not choose: ‘I can’t really pick because we need the money, but I also need my parents...so I don’t think I could choose’ (16 years old, Strive High).

There is surprisingly little difference in preferences between different house-hold types, with around half of those in dual-earner couple, single-earner couple and sole parent/earner households looking for more time, while about a fifth of each would choose more money through more parental work. Although having two parents in paid work might be expected to drive a preference for parental time more than in single-earner couple households, it does not. Neither does living in a sole parent/earner household.

Further conversation revealed that many young people in single-earner house-holds miss their breadwinner parent and are looking for specific time with them. They may see plenty of their mother, but this does not stop them for looking for time with their father, especially a father with a demanding job. This may explain the counter-intuitive result of little difference in preferences between children in single-earner and dual-earner households.

The more striking differences in money/time preferences lie with location and the demands of parents’ jobs, especially their hours. A sizeable difference in time/money preferences exists between those who live in Sydney—whether in low- or higher-income areas—and those who do not. Sydney-based young people showed a stronger preference for more money from parents’ work. Three times as many Sydney children wanted more money, than the proportion in Adelaide and the country. Given that Sydney is a relatively high-cost city, with very high housing costs, this is not surprising.

the ‘downsides/bad’ of mothers’ and then fathers’ jobs. Only a couple of the 43 children who mentioned that a parent worked long or unsocial hours did not name this as a negative aspect of their parent’s job, and in at least one case this was because they were ‘used to it’. Fifty-six per cent of those living with such a parent wanted more time with parents (while only 19 per cent wanted more money). This compares with 38 per cent of those who do not have a parent who is seen as working long or unsocial hours who wanted more time.

A work/spend cycle (whereby more work drives more spending and more spend-ing drives more work (Schor 1992)), was evident to many young people: ‘They earn more money so they can buy you more things, but I don’t get to see them as much if they’re working more’ as one young woman at Struggle High put it.

Young people in lower-income areas showed a high level of understanding about how their parents’ work patterns fund necessities and loans. They wanted the time, but they were understanding: ‘I’d prefer a bit more money because we’ve got a lot of loans to pay off and we’re really tight for money recently, so I’d prefer a bit more money...not too much that I don’t see them at all, but just a bit more’ (Melinda, 16, Strive High). These children see their parents working

hard—and they feel that this is for them. They see more money as a means to mitigate pressure on parents. Nearly all children in the country chose more time with their parents over more time spent earning, even though each of these had a mother at home or working part-time. They looked for more time from their fathers in particular. Like young people in the city, they understood the need for money. They were mostly sympathetic to their parents and their jobs.

The hyper-breadwinner

These discussions suggest that in single-earner couple households—the tradi-tional ‘breadwinner’ home—a form of ‘hyper-breadwinner’ is evident: that is, a breadwinner who is absent for long periods as he (they are mostly fathers) takes on the whole task of household earning. For many breadwinners in this study, this means overtime, longer hours at work, working on the phone or lap-top after hours, or travelling long distances to work intensively or for extended periods.

Having a parent who works long or unsocial hours drove a preference for time over money. In some cases, children were clear that they wanted time with one parent—always the one working longest or seen least. As Ali at Leafy Primary in Sydney described his Dad’s situation: ‘I think it’s not good because I don’t see him in the morning at all. He has to leave really early before I wake up and he comes home really late so its annoying ‘cause I never really see him...I never really get to interact with him. So it’s kind of lost time with him’ (Ali, 11, Leafy Primary). The good thing about his father’s job is that he ‘gets lots of money’.

workers: children of managers, small business people and professionals shared this perspective.

Parent-specific time hunger

At Comfort Primary, with relatively secure higher incomes, most children chose more time with their parents over more money, especially more time with a parent who is absent more. Nicky was an exception: she would choose more money, re-flecting the fact that she lives with her single mother who works part-time while her dad lives in another city. The general preference for time at Comfort Pri-mary illustrates how breadwinner household structures—with a time-rich parent at home, usually the mother—do not eliminate parental time hunger for chil-dren. Instead, they show a‘parent-specific’ time hunger. In the hyper-breadwinner household, where the breadwinner is working long or unsocial hours, that time hunger is pronounced, focused upon the absent parent, most often their father. For example, Bob, whose father runs a sporting range and sometimes works long hours while his Mum works part-time, wants to spend more time with his parents ‘especially my Dad because he hasn’t spent a lot of time at home’, and would chose that over more money.

A full-time job does not mean a lack of time with young people for some. Ellie, for example, who lives with her mother who works full-time, says that her mother ‘really enjoys her job...but I still see her, and my Mum and I are pretty close and we still can spend heaps of time together. So it’s good. She really likes it...She says its really satisfying’ (Ellie, 16, Leafy High).

Long hours and money/time

Hours are an important determinant of children’s perspectives about their parents’ jobs. Long hours are consistently associated with negative views of parental work patterns. A number of young people defined their own futuresagainsttheir parent’s working lives. They plan to make sure they spend enough time with their own children, or want to avoid demanding jobs and make sure they have weekends off. They name the kind of ‘work/eat/sleep’ cycle that long hours workers also name for themselves (Pocock, van Wanrooy, Strazzari & Bridge 2001):

Dad earns money and gets out—but he hardly spends any time with you. He comes home, eats tea and watches TV. We’d liketime...He feels bad because he can’t spend

time with the family. (Kelsey, 12, Struggle Primary).

When it comes to choosing between time and money, Bonnie, daughter of a country truck driver, did not hesitate: ‘more time...even if that means you mightn’t get everything that you wanted’. Brittany, in Sydney at Leafy Primary agreed: she wants more time. Some young people see a link between more time at work and poorer quality relationships. Several were very conscious of long hours and their impact on household relationships, seeing the need to balance money with time. As Adam, son of a cabinet maker and aged carer put it:

Time with fathers

Young men do not stop wanting time with their fathers as they grow up based on the consistent comments of 16–18 year old boys. While not all young men in our study felt the same (indeed some spoke of feeling distant from their fathers because of their absence over time), others were straight-forward about their sadness:

I reckon my Mum [who works part-time] is pretty much fine the way she is. Just leave her like that. But I suppose a little more time with my Dad would be good, seeing as I usually get to see him for about five minutes in the morning after I get up and he usually gets home around the time I’m doing homework so I only get to see him around tea time, and onwards at night. So not too much going on there. (Kyle, 16, Country High).

Kevin (17, Country High), whose father worked very long hours in the country, would like more time playing backyard cricket with his father, more ‘hang around time’: ‘I wouldn’t mind if I just sat in the next room, but it would be better if he wasn’t doing as much work’. Adam—from the same region—agreed. His father works in an industry with peaks and troughs. These young men whose fathers worked long or unsocial hours, missed time with their fathers, and were very alert to paternal stress. It is not surprising that they do not miss their mothers, given that most were at home or held part-time jobs, but their clear preference for time with the fathers, especially withunstressed fathers, suggests that time with one parent does not easily substitute for time with another: father-time has its own function and is clearly desired by young men (and young women).

For many children,timeis a key first requirement of a ‘good dad’. Kelsey, 12, at Struggle Primary describes a ‘good Dad’ as someone who ‘spends time with you’. Her friend Kelly agrees: ‘someone who mucks around with you’. For Zoe, whose father left her life some time ago a ‘good dad’ is ‘some one who doesn’t just come and leave’. In the same school, Harry whose father left when he was very young because ‘he didn’t like kids’ agrees: ‘A good Dad would be if he was part of my family again because it would be better if he still had a job and came back. If he came back and lived with my Mum and still got paid $700, it would be great’ (Harry, 11, Struggle Primary).

When discussing a ‘good mother’, young women stressed the importance of someone to talk to about issues of importance, particularly social relationships. While some young men mentioned this, they stress the importance of time with their fathers more. Young men were more likely to equate a good mother with a good cook, and value their help with homework.

Overwhelmingly young people spoke of the importance of their parents being there for special events, such as sports, choir, public performances, when they received an award, or for special events like birthdays. This confirms other findings (Galinsky 1999; Lewiset al.2001). Many sadly remember key events that their parents have missed. They like to share their successes and public events, and they also want parents around to help solve problems when they occur. Several didn’t think that ‘make up’ time later really compensated: they wanted their parents to witness their achievements and activities.

Many young men anticipate spending a considerable amount of time with their own children—taking care not to miss weekends and evenings, and some will parent very differently to their fathers, in terms of time and work allocations:

I’d love to be able to take a few years off and not work and spend it with my kids and with my wife and just starting a family and being there for my kids for the first few years of their life. But then I’d definitely go back to work like when they start school, but I’d make sure I was there for them in the evenings, help them with their homework and on the weekends do sporting activities and all that. And when they are older and think I’m just boring and not cool, let them do their own thing, but I’ll still try and sneak in some quality time. (Smithie, 17, Leafy High).

JOB SPILLOVER: HOW PARENTS’JOBS AFFECT YOUNG PEOPLE

Alongside the issue of work and time trades, the issues of spillover (from work to home and from home to work) have been widely discussed in the work and family literature (Pleck 1977; Hertz and Marshall 2001). This study shows that, from the children’s perspectives, not all jobs are the same. And not all children’s perspectives are the same, even about jobs that might appear similar. The effects of work on children are highly context-specific and diverse. Nonetheless, some similarities are striking and reinforce existing research.

A great deal of public attention in Australia has focused onwhetherto work when children are young—especially whether mothers should work. For young people in this study, this is the wrong question. This reinforces Galinsky’s (1999) US results, and those of Lewiset al. (2001) in Australia. Young people understand that many of their parents need to work and they do not see parents’ work as intrinsically bad or good. The important issue for the young people in this study is not whether parents go to work, butthe state in which they come home. Young people comment upon thenatureand effects of their parents’ jobs, rather than about whether they work or not. They talk about the effects of their parents’ jobs on them and their brothers and sisters—rather than seeing a problem with parents’ jobsper se. Many can see positive outcomes for their parents from their paid jobs—outcomes that flow to children through material comfort and, beyond this, to a happier parent and household. This is a consistent finding, evident in most focus groups, age groups, and in all household types.

et al.(2001) report . These include physical and emotional effects. Fred sees that ‘my little brother was really hard work for my mum’ when she looked after him full-time (Fred, 11, Comfort Primary). Others perceived tiredness, physical injuries, social isolation or a heavy domestic load that mothers often carried alone. Young people are also aware of the under-valuation of their mother’s work at home, and several mention their mother’s depression. Other children commented upon mothers who were happy doing domestic work. Once again, however, it is not the job itself that causes noticeable spillover,but its fit with parental preferences.

With respect to paid work there are a clear spillovers onto children. These include both positive and negative effects. Most obvious among the positive effects is income. Alongside this, many young people see benefits for them arising from their parents’ work-related skills. In addition, many children enjoy the things parents bring home: pens, equipment, supplies. Young people also see that their parents have fun and gain a sense of worth and contribution through their jobs. Others feel that parents enjoy making friends, having laughs and social connection through their jobs. As one put it ‘She tells funny stories from work, the people at work. My mum likes her job’ (Susie, 16, Comfort High). Others speak positively when their parents’ work is flexible, when they work hours that mean that they are home at the same time as children, and when they are able to participate in a meaningful way in their parents’ work.

On the negative side, many forms of spillover are obvious and common. The daughter of two full-time working parents who said ‘My parents try not to bring the work life home’ was unusual. She appreciated their containment: ‘I don’t really need their stress as well as mine’ (Jade, 16, Comfort High). Most young people could easily tell what kind of day their parents had had when they walk in the door. Jobs ‘colour’ parental moods—to use Nasman’s expression (2003), affecting their ‘state and physical condition’. However, these effects go beyond mere ‘colouring’ of parental mood. They are directly transmitted to children and to others in the household. Children not onlyobservetheir parent’s ‘colour’, but many are affected by it themselves and feel its effects through yelling, arguments and household tension. Young people are especially alert to thesenegativespillovers: it is these they notice and respond too—often withdrawing from their parent to cope. In line with studies in other countries, they notice when their parents are upset (Galinsky 1999; McKeeet al.2003).

arising from more occasional or episodic events—like injuries, job loss, redun-dancy, demotion or reassignment.

The impact of long or unsocial hours: ‘he’s not violent, he just yells...’

Long or unsocial hours were frequently mentioned as a first effect of parents’ work, with almost universal negative effects. Like others, Ali noticed his father’s stress and anger after a long shift: ‘sometime when he comes back in the afternoon he gets angry at simple things cause he’s stressed’. Andre’s father, an artist, is also ‘stressed and tired’ when he has been working late on a painting.

Children identified direct negative effects of long hours upon their parents. The word ‘grumpy’ was frequently used to describe parents—just as it is often used by long hours workers (and their partners) to describe themselves (Pococket al. 2001). Kyle (16, Country High) said of his farmer father ‘he’s got to work long hours, go and do things if he finds something wrong in one of the paddocks just as he is about to knock off. He has to go and fix it or whatever.’ As Kyle described it ‘You do something wrong and he gets up you’. ‘Yeah’ agreed Robert: ‘he usually comes home in a pretty foul mood and you’ve got to tread lightly around him’ (17, Country High). James (15, Struggle High), whose dad drives a truck for long hours, couldn’t see anything good about his father’s job. He described how its effects spilled over into non-work time.

In a higher socio-economic setting, Mark’s father works two jobs. He has given up a third which has made him ‘happier’. One of his jobs involves night shifts:

He’s incredibly tired, all the time, because he is just constantly going and he gets aggravated. He’s not violent, he just yells and he can yellreallyloud. He doesn’t do it all that often considering the stress he is under. (Mark, 17, Comfort High).

Like other young people, Mark is very understanding about his father’s work and its effects. He sees his dad as ‘good fun’ and—for all his occasional yelling— loves spending time with him. He keeps out of his father’s way when he is ‘in-credibly tired’.

Young people respond to negative spillover in several ways: most commonly they physically withdraw from a grumpy or shouting parent; they may turn to the other parent and distance themselves from the absent or grumpy parent. Some take steps to look after their tired parent. Others just worry about their parents, while others dislike—or hate—the contamination of their emotional states by their parents’ jobs.

tiredness. These effects cross most boundaries: city and country, high and low incomes, boys and girls, and they affected workers in blue, white and pink-collar jobs, reaching into many occupations and industries. Both small business owners and operators, and wage earners were affected in the perception of young people. Where fathers worked long hours there was a considerable sense of loss, and in some cases hurt and anger, particularly among boys and young men. Young people spoke of how their parent’s anger and frustration with work, spilled over onto them. With parents on a short fuse, young people knew when to ‘keep out of the way’. They valued some explanation about their parents’ moods. They did not like their parent being ‘shitty’, and it spilling over into interrogation of their children, but an explanation for these spillovers mitigated their effect.

RE-FRAMING THE WORK AND FAMILY DEBATE: IMPLICATIONS FOR POLICY,ACTION AND THEORY

This analysis affirms research that tells us thatit is not whether parents go to work or not, but the state in which they come home, that really affects children. This ‘state’ reflects objective characteristics of jobs (like hours and intensity) as well as the extent to which parents’ preferences match their jobs. The debate about whether to work or not needs to be re-framed in Australia (as Galinsky (1999) has argued in the USA). In particular, less attention should be paid to the issue of whether mothers should hold paid jobs, and more to the work of fathers. Most importantly, a mother at home does not make up for a father who is absent a great deal.

For many children, their mothers’ and fathers’ jobs are associated with positive spillover. Young people value the money and security that parents’ paid work brings. Beyond this, they can see that many parents enjoy their jobs, or aspects of them. They love their stories, sense their social connection through work, and see that their parents have fun and feel good about doing a job well.

But negative spillover is also widespread. It is especially associated with dis-appointed parental preferences (for example, a parent who doesn’t want to work part-time but has to, or a parent who cannot work the shifts they want). It is also associated with some specific job characteristics: risk of physical harm, job insecurity, work overload, or long or unsocial hours. These often send a parent home from work angry or upset. Their moods are obvious to young people—from physical, verbal and behavioural clues. Children ‘read’ their parents easily.

How should parents, workplaces and public policy respond to these findings? At the individual level, it is clear that ‘working mothers’ are not, in themselves, a problem in the view of children. Many see benefits arising from parents’ jobs. The nature of work itself, and its impact upon parents, emerge as the more important considerations. Where jobs send parents home worried, sick, hurt, tired or bad tempered, children notice and are negatively affected. Such spillovers are not confined to paid jobs: they also arise from domestic work if it fits poorly with parental preferences, or leaves parents isolated, depressed, tired or under-valued. Too much worry about having a job at all—especially with respect to working mothers—has diverted attention from more significant aspects of work that young people notice—like how absent working fathers or their long hours affect children, and how work affects parental bodies, tempers and emotions. It seems that negative spillover is reduced when parents do work that they like, for hours that suit their preferences, while minimising physical injury and long or unsocial hours that leave them bad tempered or tired.

Of course, this is at once both obvious and more easily said than done. For many parents their preferences do not—alone or even in significant part—determine their labour market outcomes; these are instead overshadowed by larger struc-tural, systemic and institutional forces. Changing these requires new public and workplace policies and practices. The finding that long or unsocial hours affect children negatively, in their perception, reinforces the well-documented concerns of adults (Pococket al.2001; Peetzet al.2004). This strengthens the argument for policies that contain hours of work to social and reasonable levels.

Other policies and practices that assist parents to find a good fit between how they want to parent and how they work, are also important to the perceptions of children. These include measures that increase worker say over the allocation of working time and its organisation (or greater ‘worker time sovereignty’), including over hours of work, start and finish times, days off, holidays, shifts and rosters. Greater worker capacity to move into and out of full-time and part-time work, without risk to employment or earnings, and into and out of paid work itself will also help by protecting home and children from fears about income and job security. This includes a policy regime of tax and social security arrangements that does not penalise people for changing jobs or for moving into and out of the labour market to get the best possible fit of preferences with circumstances. Predictable and secure job arrangements that do not destabilise and frustrate preferences, with negative consequences for the security of children, are also likely to be significant. An improved suite of paid and unpaid leave rights for working parents will also assist parents to better meet the changing demands of their dependents so that they can better parent around their work to meet both their own preferences and those of their children.

at present, as more carers (especially mothers) enter paid work, and experience personal guilt and very variable institutional supports (Pocock 2003). This analy-sis of the perceptions of young people confirms that theoretical treatment of work and family as separate social and policy spheres is unhelpful. They are intimately connected. This connection requires analysis of work that recognises that paid work is located within a larger ‘total labour’, and within diverse households and communities. It also requires policy action that takes account of these connections. Increasingly, producing bodies are also reproducing bodies, which affects how we must think about workers, workplaces, dependency, childhood and households.

In the perception of these young people, the spheres of work and households are not consistently in opposition to one another, the one draining the other. Work does not always have negative effects upon young people: positive spillover from work for some is also evident, encouraging us to consider ways and means to increase positive spillover, and to reconsider the conventional binary and op-positional theorisation of ‘work’ and ‘home’.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This research was funded by The Australia Institute and the Australian Research Council through the fellowship project ‘Theoretical and policy implications of changing work/life patterns and preferences of Australian women, men and children, household and communities’.

REFERENCES

Campbell I (2002) Extended working hours in Australia.Labour & Industry13(1), 73–90. Galinsky E (1999)Ask the Children: What America’s Children Really Think About Working Parents.

New York: William Morrow and Company.

Hertz R, Marshall NL (2001)Working Families.The Transformation of the American Home. Berkeley CA: University of California Press.

HILDA (2001)Annual Report. Melbourne: Melbourne Institute.

Jensen A, McKee L (Eds) (2003)Children and the Changing Family; Between Transforamtion and Negotiation. London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Lewis V, Tudball J, Hand K (2001) Family and work: the family’s perspective.Family Matters, No 59, Winter, 2001. Melbourne: Australian Institute of Family Studies.

McKee L, Mauthner N, Galilee J (2003) Children’s perspectives on middle-class work-family ar-rangements. In Jensen An–Margritt, McKee Lorna (Eds),Children and the Changing Family; Between Transformation and Negotiation. London: RoutledgeFalmer, pp. 27–45.

Megalogenis G (2003) Fault Lines. Race, Work and the Politics of Changing Australia. Scribe, Melbourne.

Nasman E (2003) Employed or unemployed parents: A child perspective. In Jensen An–Margritt, McKee Lorna (Eds.),Children and the Changing Family; Between Transformation and Negotiation. London: RoutledgeFalmer, pp. 46–60.

Peetz D, Fox A, Townsend K, Allan C (2004) The big squeeze: Domestic dimensions of exces-sive work, time and pressure.New Economies: New Industrial Relations,Proceedings of the 18th AIRAANZ Conference, 2–6 February 2004. pp. 381–390.

Pleck JH (1977) The work/family system.Social Problems, No. 24, 417–427.

Pocock B (2004)Work and Family Futures.How Young Australians Plan to Work and Care. Canberra: The Australia Institute.

Pocock B (2003)The Work/Life Collision.What work is doing to Australians and what to do about it. Sydney: Federation Press.

Pocock Bet al(2001a)Fifty Families: What Unreasonable Hours are Doing to Australians, Their Families and Their Communities. Melbourne, ACTU.

Pusey M (2003)The Experience of Middle Australia, The Dark Side of Economic Reform. Cambridge, Cambridge University Press.

Schor J (1992)The Overworked American: The Unexpected Decline of Leisure. New York: Basic Books. Summers A (2003)The End of Equality. Sydney: Random House.

Tanner L (2003)Crowded Lives. Sydney: Pluto Press.