Volume 12, Number 8, August 2015 (Serial Number 118)

Jour nal of US-China

Public Administration

Dav i d

Publication Information:

Journal of US-China Public Administration is published every month in print (ISSN 1548-6591) and online (ISSN 1935-9691) by David Publishing Company located at 1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, IL 60048, USA.

Aims and Scope:

Journal of US-China Public Administration, a professional academic journal, commits itself to promoting the academic communication about analysis of developments in the organizational, administrative and policy sciences, covers all sorts of researches on social security, public management, educational economy and management, national political and economical affairs, social work, management theory and practice etc. and tries to provide a platform for experts and scholars worldwide to exchange their latest researches and findings.

Editorial Board Members:

Andrew Ikeh Emmanuel Ewoh (Texas Southern University, USA) Beatriz Junquera (University of Oviedo, Spain)

Lipi Mukhopadhyay (Indian Institute of Public Administration, India)

Ludmila Cobzari (Academy of Economic Studies from Moldova, Republic of Moldova) Manfred Fredrick Meine (Troy University, USA)

Maria Bordas (Corvinus University of Budapest, Hungary) Massimo Franco (University of Molise, Italy)

Patrycja Joanna Suwaj (Stanislaw Staszic School of Public Administration, Poland) Paulo Vicente dos Santos Alves (Fundação Dom Cabral—FDC, Brazil)

Robert Henry Cox (University of Oklahoma, USA) Sema Kalaycioglu (Istanbul University, Turkey)

Manuscripts and correspondence are invited for publication. You can submit your papers via Web Submission, or E-mail to [email protected]. Submission guidelines and Web Submission system are available at http://www.davidpublisher.com

Editorial Office:

1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, IL 60048

Tel: 1-323-984-7526; 323-410-1082 Fax: 1-323-984-7374; 323-908-0457 E-mail: [email protected]; [email protected]

Copyright©2015 by David Publishing Company and individual contributors. All rights reserved. David Publishing Company holds the exclusive copyright of all the contents of this journal. In accordance with the international convention, no part of this journal may be reproduced or transmitted by any media or publishing organs (including various websites) without the written permission of the copyright holder. Otherwise, any conduct would be considered as the violation of the copyright. The contents of this journal are available for any citation, however, all the citations should be clearly indicated with the title of this journal, serial number and the name of the author.

Abstracted / Indexed in:

Chinese Database of CEPS, Airiti Inc. & OCLC

Chinese Scientific Journals Database, VIP Corporation, Chongqing, P.R.China Database of EBSCO, Massachusetts, USA

Google Scholar

Index Copernicus, Poland

Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD), Norway

ProQuest/CSA Social Science Collection, Public Affairs Information Service (PAIS), USA Summon Serials Solutions

Subscription Information:

Print $560 Online $360 Print and Online $680 (per year)

For past issues, please contact: [email protected], [email protected]

David Publishing Company

1840 Industrial Drive, Suite 160, Libertyville, IL 60048

Tel: 1-323-984-7526; 323-410-1082. Fax: 1-323-984-7374; 323-908-0457 E-mail: [email protected]

David Publishing Company www.davidpublisher.com

DAV ID P UBL ISH IN G

Jour na l of U S-China

Public Adm inist rat ion

Volume 12, Number 8, August 2015 (Serial Number 118)

Contents

Management Issues and Practice

The Resistance to Change as a Specific Risk for the Organization Transformation 593

Costel Loloiu, Toma Pleşanu, Dumitru Cătălin Bursuc

Performance Target Setting System and MoU Experience in India 603

Ram Kumar Mishra, Geeta Potaraju

Economical Issues and Innovation

Impacts of Intellectual Capital on Profitability: An Analysis on Sector Variations in Hong Kong 614

Michael C. S. Wong, Stephen C. Y. Li, Anthony C. T. Ku

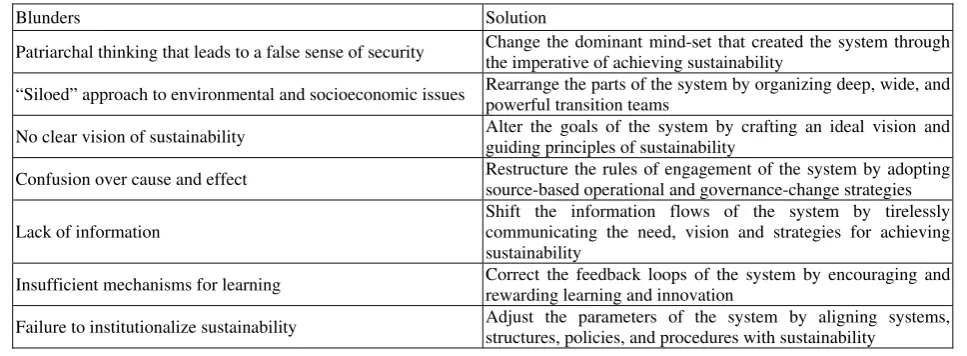

Models for Transforming Businesses Toward Sustainability 627

Julia Dobreva

Political Studies and and Social Governance

ASEAN’s Role and Potential in East Asian Integration: Theoretical Approaches Revisited 635

Nguyen Huu Quyet

Fiscal Sustainability: Responsiveness in Times of Crisis: A Review of Sub-National

Governments in Mexico 651

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2015, Vol. 12, No. 8, 593-602 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2015.08.001

The Resistance to Change as a Specific Risk for the

Organization Transformation

∗

Costel Loloiu, Toma Pleşanu, Dumitru Cătălin Bursuc

“Carol I” National Defence University, Bucharest, Romania

The theoretical approaches and also the practice in organizational change show us that there is no such thing as a

pre-defined solution, that we cannot say about an organization perspective if it is good or bad, but we can say about

it that it is appropriate, in accordance with the organization objectives, that it answers to the national specific and

also to the economic and social context. The pre-established solutions do not have an absolute value, they represent

only recommendations for establishing the actions regarding the organization management, the applying of the

performance management instruments, the developing of the transformation abilities, the change implementation.

In this situation, a question arises: Why does a useful and necessary transformation needed to accomplish the

organization objectives face a resistance? Besides the personal interests and attitudes, the resistance explanations

should be sought in the lack of correlation between the institutional objectives and individual ones, an area which is

not enough regulated by the organizational culture, but more often at a high level of inadequacy between the

structure and the categories of objectives mentioned above. We appreciate as being essential the learning capacity

proved by the organization; the innovative side must face the human nature which preserves its comfort created by

the routine, developing the tendency of denial for every change.

Keywords: resistance to change, organizational transformation, risk management

The organization responds to the environmental modifications by adapting specific changes which only aim to the planned outputs limit or may represent the reorganization of structures or processes. The manager equally thinks about the present and the future, the change orientation refers to the given chance and also to the subsequent events threat (Druker, 2010, p. 124).

The nowadays situation of public companies, with new and dynamic risks toward their functionality, makes the managers effort at the strategical and tactical level to aim mainly to designing and implementing the change. Besides the required qualities and abilities for managing the public organizations, it is mandatory the

∗

This work was possible with the financial support of the Sectoral Operational Programme for Human Resources Development 2007-2013, co-financed by the European Social Fund, under the project number POSDRU/159/1.5/S/138822 with the title “Transnational Network of Integrated Management of Intelligent Doctoral and Postdoctoral Research in the Fields of Military Science, Security and Intelligence, Public Order and National Security—Continuous Formation Programme for Elite Researchers”—“SmartSPODAS”.

Costel Loloiu, Ph.D. candidate in military science and information, “Carol I” National Defence University, Bucharest, Romania; research field: public administration. E-mail: [email protected].

Toma Pleşanu, Ph.D., Colonel Professor Eng., Dean of the Security and Defence Faculty, “Carol I” National Defence University, Bucharest, Romania; research fields: project management and knowledge management. E-mail: [email protected].

Corresponding author: Dumitru Cătălin Bursuc, Ph.D., Comander (Navy) Eng. Senior Instructor, Director of Postgraduate School in Military Management and Teaching Staff Training Department, “Carol I” National Defence University, Bucharest, Romania; research fields: modelation and simulation, military education, and career training. E-mail: [email protected].

DAVID PUBLISHING

leading personnel recognize the moment when the change is needed or unavoidable and they must require the others to be part of the initiative. The specialized literature adds the transformational leader to the classical leader types. This type of leader convinces the inferiors about the importance of achieving the new objectives and the rightness of the methods through which they are achieved, increasing the level of implication, the responsibility and the common goal adhesion. In this case, the personnel is encouraged to modify its thinking regarding the way they approach the problems, the subordinates are encouraged to have a new vision and a new attitude toward the problems, according to the personal and the organization objectives (Ispas, 2012, p. 25). The personnel focusing on the activities circumscribed to a successful project could develop a high inertia level which, in the case of running a new project represents a good premise for the organization transformation (Ruckes & Ronde, 2015, pp. 475-497).

The discussion on change must not exclude the continuity elements in the organization activity or structure. The continuity plans existence is legitimated by the fact that, the change must, in the first phase, identify the operations of maximum importance, so that the organization could achieve the main prerogatives the way they are defined in the strategical plans or the normative provisions. The recommendation referring to the continuity plans is that these should be developed starting from the most pessimistic scenario, taking into account the fact that the measures which must be taken should be at a smaller scale, in order to be adapted to the real situation which determined the necessity of change (ASIS Commission on Standards and Guidelines, 2005).

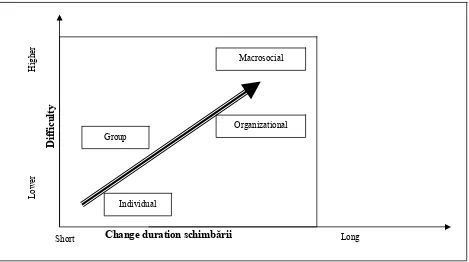

The difficulty of making the change is directly proportional with its depth and the structure dimension which is referring to. The change amplitude goes from individual to group level and to the organizational one. The project management has the most evident dynamics at the project team level, which from one phase to another or from one project to another reorganizes itself inside a matrix structure made up of specialists from different fields of activity.

For public organizations, the modality of change implementation is, generally speaking, from top to bottom due to the set hierarchical structure and the way the authority is centered. The authors consider the restructuring and the functional reorganization as being part of the generally term. They admit that it might exist a situation when change is not responding to a macrosocial situation modification, and this fact leads to other transformations, which are inevitably more subtle. In this case, the change is internally planned by a group with formal authority or informal influence that takes to functioning changes or structure modifications.

We should note that the change reaches the macrosocial level and sometimes has a nature which is inevitably commanded by global evolution. Figure 1 shows the change levels and the relation between the necessary time for the change correlated to its difficulty.

Figure 1. Difficulty and change duration correlation depending on the change level.

Change Resistance and Its Characteristics in Public Organizations

The issue of risks in public organizations cannot be analyzed separate from the realities which accompany the contemporary realities. An integrated model of activities analysis and planning at any level is needed so that the prevention may become an essential component of activity at any level. Organization must respond by structural modifications and by adapting their specific tasks to the new realities and to the way they influence the administrative structures and their missions. It is necessary for the specific regulation basis which ensures the risk’s integrated management in administration companies to be evaluated and reconsidered, in order to observe the organization necessity to adapt itself.

The change formal goals are: increasing the performance in objectives achievement, maintaining the internal organization balance, adapting and functional optimization together with the flexibility of the environment dynamics.

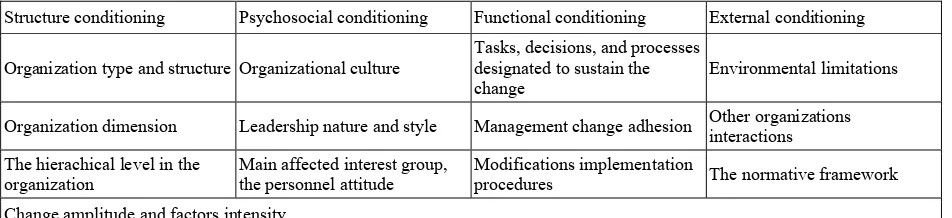

The environment changes and the organization internal evolution represent the change potential of the organization structure, of culture, policies and their processes. In reality, an important resistance is shown when the authors try to implement the modifications in the organization. They adapt a Leavitt diagram (see Figure 2) in order to illustrate the interdependent change characteristics and the mutual influence between technology and organization. Thus, the technological changes are turned from the right direction and cancelled by processes and organizational compounds, structures or persons. The Leavitt pattern of organization evolution shows off that the efficient way to induce the change is represented by a simultaneous change of technologies, tasks, structures, and persons.

It is necessary for the organization to be prepared before a change insertion in one of the components; then it comes the rapid implementation followed by a change institutionalization. The organization determinants which must be taken into consideration are shown below (see Table 1).

Change duration schimbării

Difficulty

Long

Higher

Lower

Short

Group

Individual

Figure 2. Levitt diagram.

Table 1

The Organization Determinants Which Play a Role in Transformation Process

Structure conditioning Psychosocial conditioning Functional conditioning External conditioning

Organization type and structure Organizational culture

Tasks, decisions, and processes designated to sustain the change

Environmental limitations

Organization dimension Leadership nature and style Management change adhesion Other organizations interactions The hierachical level in the

organization

Main affected interest group, the personnel attitude

Modifications implementation

procedures The normative framework

Change amplitude and factors intensity

In order to get benefits deriving from change, the alining of individual and collective interests must be designed at the same level and with the same intensity as the changes imposed by the implementation of the technologic factor. For example, if we choose technology because of the informatics and communication technology evolution acceleration, the modification will require changes of the organization culture elements and the norms, values and procedures.

Recent study (Righi & Saurin, 2015, pp. 19-30) shows that changes targeting the technological modifications have a pretty reduced framework to make them operational. Rules of change implementation are set and they follow the system complexity and environmental limitations which may have four directions which trace the dynamics interactions and also the unexpected evolutions with direct or mediated effects.

The forces-field action which governs the organizational transformation compares the change forces and the forces which oppose the change (Card, 2013, pp. 87-92). Forces against change can be of individual or group type and they refer to the following elements (Kotter & Schlesinger, 2008):

(1) Personal interest not connected to the organization interest; (2) Errors in understanding the implications of organizational change;

(3) Different situation assessment especially between the management and the workers; Tasks

Persons

(4) Low tolerance to change generated by the distrust to the capacity to adapt.

The recommended action is, in this case of deficiencies, reducing the forces which are opposing the organizational change. If correctly and in time identified, these forces may be reduced until cancelling their unwanted consequences using efficient management measures, a good communication inside the organization and a harmonization in the informal plan of the organization structure. The optimal solution is to transform them in forces that are positive to change.

When they are not controlled, the analyzed forces are uncertainty elements for the decisions, the management must make and in that situation, it is obvious that the person will try to reduce the problem to familiar situations using simplification.

Taking into consideration the pressures induced by changes on decisional personnel in the public organization, the authors admit the absolutely natural situation when these persons need certainty about the taken decisions. Adequate for this phase of organization transformation, the risk integrated management provides a warranty and control progressive framework that contributes to the transformation success.

Change Resistance in Public Organization Seen as a Risk Factor

The present and the processes and phenomena evolution at global level are characterized by a permanent state of change. Assessing the risks for the organizations must be related to this dynamic and to turn it into specific instruments that should ensure an optimum for functioning in managerial planning. Actions that in the past were blamed and were low disseminated, nowadays are widely diffused. For example, in the 75% of actual

conflicts, the children are used as soldiers or in the suicide attacks1.

Modifying realities at macrosocial level means a raised dynamic of the organizational change. At public organization level, changes in risks and threats situation referring to fundamental goals and their evolution raise very much the organizational changes rate. The risks’ management must develop a character which should eliminate the reactivity in order to respond to these transformation situations.

The social practice and also the elementary logic validate that risks cannot be identified and evaluated in their integrity. Opposite this situation, the authors find the tendency to deny the risks, an attitude type underlying the idea that an unknown danger does not affect you (Bursuc, 2014, p. 232). In the managerial practice, nowadays, there is a mutation from the situation of confronting the risks and assuming them, to an analysis and systematic risk measurement phase and also design of the ways to manage them.

The current legislation allows overcoming the reactivity management and enforcement of a proactive

conduct in the management exercise. So, at the organizational level, the risk management is included in the internal control management, thus providing systematic tools for diagnosing, monitoring, and managing the risks associated to organizational activity.

The Institute of Internal Auditors (IIA) determines a mutation on the way risks are seen at the

organizational level2. This perception will allow us to take into consideration the organizational change

mechanisms.

The risk management becomes an integrated part of the internal audit, the process being characterized by decentralization, accountability, and expanding of the best practices. By specific norms, a system of risk

1 UNHCR.

2008 global refugee trend: Statistic overview of population or refugees. Internally displaced persons and other persons in concern to UNHCR. Retrieved from http://www.unhcr.org.

management is set even where it does not exist. Risk is seen as any factor which can have an impact on the organization capacity of reaching its goals. In this situation, we can include the unfavorable personnel action generated by the distrust on management, misunderstanding of the change objectives, or lack of adhesion. The situation of the forces involved in change requires an assessment of the forces for and against transformation. The analysis allows highlighting the forces pro-change and their share, a situation that is usually in balance and which is naturally against change. The conceptual integration of the mentioned elements converges to describing organizational pathologies characterized by lack of flexibility and adaptation at all levels, a reactive attitude and constant response post-factum to changes in the environment.

Thus, the risk management provides a methodology that ensures a global risk management, which allows the organization to get the best cost under a programmed change. The estimated risk factors are any deficiencies, non-conformities, environmental or organization irregularities in the context of occurrence of events and they will cause adverse consequences for the entity. The regulatory framework well set must be doubled in practice by structures and responsibles at organization level, which from decision positions to plan and implement the right measures for the optimization of the process (Books, 2011, p. 17).

All these elements are found in the practice of public organizations but, because of their specificity, the elements take particular ways of expression. As an open system, a public organization has only a direct internal control with limited possibilities to adjust effectiveness. This refers to the functioning and activities assessment, the act which is the responsibility of members with duties; we include here the super organized structures staff. Other persons outside the organization, through their action only induce influence elements of the external environment. This lack of control and regulation through direct feedback at macro-social level is complemented by internal mechanisms which are legislatively regulated.

The reduced possibility of external control over public institution determines its greater rigidity and at the same time, gives the organization greater stability over time. Compared with other types of organization, the mentioned stability generates a high level of institutional inertia against the change adaptation.

The public organization is characterized by strict normative regulations, the necessity of specific normative regulations in the administrative field is one of the highest, because the organization is extremely complex; the stake of carrying out the tasks is good governance and it should be noted that unlike other organizations, a number of consequences of the activity, as error or failure, have an absolute existential value

condition3.

The evolution of society in the transition to the economy based on knowledge and less on conventional raw materials and physical labor occurs in close correlation with changes in the productive and social sector and induces changes in the nature of public administration. This framework requires a new understanding of relations between the administration and a rapidly changing society (Toffler, 1995, p. 89), including a new understanding of how to adapt the organization to the changing process of global society.

Usually, the change means to give up stability, the conditions, and the action context which used to be; this fact, associated with the impossibility of controlling future announced by the change, provokes insecurity justified by the risk factors and direct or derived consequences.

The conclusions of studies from the last two decades highlight the importance of the way people perceive and relate to change, identifying some factors appreciated as risk factors, factors which provoke the resistance

to change and they refer to:

(1) The lack of information regarding the goals and the change sense having as a result the lack of motivation;

(2) Information concerning the acceptance of change is effective when there is homogeneity of organization members, which is only possible for small organizations.

The change management act represents a strategic activity for the management, for a leader who must identify and know the organizational characteristics, understand the specific of every phase in functioning the institution general mechanism which allow him/her the intervention in order to raise the actions’ efficiency and efficacity. The bureaucratic institution notion implies change rigidity generated by the fundamental characteristics of this type of organization:

(1) Exclusive vertical subordination;

(2) Correlating authority with responsibility during activities;

(3) Increasing the role of discipline and order in organizational cohesion; (4) Specialization of roles and statuses;

(5) Jobs, functions, and degrees hierarchy.

From this perspective, the public organization does not exist as a result of individual options, but based on objective criteria that take into consideration the personnel capacities, abilities, and disponibilities to fulfill tasks.

The internal hierarchy is distinguished from others because it generates social group layers. The social distance between the positions taken by different personnel categories shapes intraorganizational phenomena which must be taken into consideration. These phenomena if not well-directed might block or slow down the organizational transformation process.

The understanding of the effects of social stratification from public organization involves a complex and interdisciplinary approach and requires ethics and consistency from the management side.

Every public organization acts for goals achievement next to the governmental apparatus components that way the organizational transformation will affect and is affected by elements interdependency from that macrosystem.

Processual Nature Solutions to Analyzed Problem

Internationally, there are some directions meant to determine the theoretical apparatus and instruments designated for integrated risk management, which will have direct implications on organizational performance. The works in the field (Burciu, 2008, p. 541) group the trends which are seen as organizational resistance overtaking elements using the following directions:

(1) Reporting to the stakeholders and the certification that the risks have been identified, but acknowledges that the need for transformation exists and is functional;

(2) Evaluating and promoting the benefits resulting from change in organization effective management; (3) Continuous improvement of methods and strategies of institutional risk management.

The practice in the fields establishes that organizations manage risk by identifying and analyzing it,

subsequently assess if the activity should be modified by risk treatment, in order to meet risk criteria4. In

4

conducting the process, organizations make public information and consult with the stakeholders, monitor and check the risk level and the means that can provide control. These means can modify the consequences in order to ensure that it does not exist a recurrence for risk treatment. International Standardization Organization (ISO) 31000 represents the international standard which thoroughly, systematically, and logically describes this process and can be used by any organization, it is not particular to a special social or economical field and can be applied to any type of risk.

For organizations of any type and dimension, it is necessary a reaction to a variety of risks which are considered to have an impact on the planned goals. The risk evaluation is part of the management that identifies the way the goals may be affected and analyzes the risk consequences and their probability of occurrence. The analysis phases precede decision and determine if a treatment is needed. As a solution, the SR EN

31010/2010 standard—risk management. Risks’ assessment technique is in theISO 31000 standard support and

ensures regulations regarding the selection and the way the systematic techniques for the risk assessment are applied.

The mentioned standard goal is to reflect the good practice usually applied in selection and the way risk assessment evaluation techniques are applied; it does not refer to new or emerging concepts that did not reach a

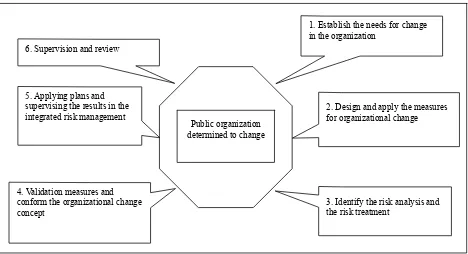

good level of professional consensus5. A procedural approach meant to treat resistance to change as a risk for

the public organization is presented in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Resistance to change processual treatment as risk in the public organization.

For synthesizing the stages of exemplified treatment, the authors will briefly resume the components of the organizational change process:

(1) Defrost—reducing the forces that maintain organization in the present state; (2) Change—transforming the organization to a new and desirable level;

5 http://www.consultanta-certificare.ro/stiti/iso-31010.html.

Public organization determined to change

1. Establish the needs for change in the organization

2. Design and apply the measures for organizational change

3. Identify the risk analysis and the risk treatment

6. Supervision and review

5. Applying plans and supervising the results in the integrated risk management

(3) Refreezing—stabilizing organization at a new balance state and fixing it.

We should mention that the change process must be implemented following the phases order, every phase is a consequence of the preceding functionality; in the first phase, it is essential to have information that do not acknowledge or do not follow the habits or practices from the old organization and to correlate the new information with important personal goals in order to induce a tension level that justifies the change opportunity.

Final Discussions

In case of continuous growth of environment influence on the organization, it is necessary that risk assessment is undertaken with full respect for the phases and procedures, and control and self-control activities, with their fixation on the flow stages that require permanent adaptation and updating. Only in this way, it can

provide increased activities efficiency correlated with evolving risks6.

For public organization, it is necessary that in designing risk management programs, valuable action proportional to the risk intensity should be provided, and they should be prioritized and targeted on two axes: the highest risks dangerousness or the most difficult to control. The resistance to change of the organization is not reported as a risk for organizations and it is not regarded as a specific case for the administrative institutions. An overhaul is needed and then, through planning, it is necessary to develop consistent measures, applying the same methods for similar situations being generalized in this way a positive experience and success for the organization activity. The situations of regional or global instability, which are characteristics for the periods of crisis require the more concrete measures and appropriate analysis and risk management in any organization. The organization must respond by structural changes and adapt to new realities, to specific tasks and how they influence their administration structures and missions. As well, the normative specific base which ensures the risk integrated management in public organizations must be evaluated and reconsidered.

References

ASIS Commission on Standards and Guidelines. (2005). Business continuity guideline: A practical approach for emergency preparedness, crisis management and disaster recovery. ASIS International. Retrieved from https://www.uschamber.com/ sites/default/files/legacy/issues/defense/files/guidelinesbc.pdf

Books, D. (2011). Security risk management: A psychometric map of expert knowledge structure. Risk Management, 13(1-2), 17-41.

Burciu, A. (2008). Management introduction (pp. 263-520). Bucharest: Economica Publishing.

Bursuc, D. C. (2014). Analysis of resistance to change as a specific risk of military organization. Proceedings of the International

Scientific Conference Strategies 21 12th Edition—The Complex and Dynamic Nature of the Security Environment.

November 25-26, “Carol I” National Defence University Centre for Defence and Security Strategic Studies, Bucharest, Romania.

Card, A. J. (2013). A new tool for hazard analysis and force-field analysis: The Lovebug diagram. Clinical Risk, 19(4-5), 87-92. Druker, P. F. (2010). The essential Druker. Peter F. Druker management works selection. Bucharest: Meteor Press Publishing.

ISO 31000:2009, Risk management—Principles and guidelines. (2009). Multiple. Distributed through American National

Standards Institute (ANSI).

Ispas, A. (2012). Comparative analysis—Servant leadership and transformational leadership. Intercultural Management, 14(1), 25.

6 In annex B. 2 of SR ISO IWA 2 standard—

Kotter, J. P., & Schlesinger, L. A. (2008). Choosing strategies for change. Harvard Business Review. Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation. Retrieved from https://hbr.org/2008/07/choosing-strategies-for-change/ar/1

Righi, A. W., & Saurin, T. A. (2015). Complex socio-technical systems: Characterization and management guidelines. Applied Ergonomics, 50, 19-30.

Ruckes, M., & Ronde, T. (2015). Dynamic incentives in organizations: Success and inertia. Manchester School, 83(4), 475-497. Sammer, J. (2002). Combating risk. Business Finance Magazine. Retrieved from http://www.businessfinancemag.com/

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2015, Vol. 12, No. 8, 603-613 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2015.08.002

Performance Target Setting System and MoU

Experience in India

Ram Kumar Mishra, Geeta Potaraju Institute of Public Enterprise, Hyderabad, India

In order to make state-owned enterprises (SOEs) more efficient, countries around the globe introduced a system

called Performance Contracting System which brought in focus on the results and achievements of a public

enterprise and put them on a path of financial profitability. In India, this system was called as the MoU

(memorandum of understanding) system and was introduced with an intention to bring in greater focus in the

working of the enterprises and in turn maximize benefits for their shareholders. One of the most critical ingredients

of the MoU system is identifying the performance criteria and setting performance targets for enterprises

adequately benchmarking them with similar enterprises in India and abroad. The paper highlights the issues and

challenges in determining the performance targets under the MoU system and some best practices adopted by

countries like China, South Korea, and others.

Keywords: performance contracts (PCs), performance target, performance benchmarking, memorandum of

understanding (MoU)

Performance contracts (PCs) have been adopted by governments globally as tools to enhance performance of their state-owned enterprises (SOEs). A study conducted by the World Bank shows that more than 32 developing countries adopted the system of PCs and they have been termed differently by different countries like contrat-plan in France, the memorandum of understanding (MoU) in India, signaling system in Pakistan and so on (Shirley, 1995). All these contracts are negotiated and written agreements between governments and their enterprises with mutually agreed targets which the enterprises achieve within a given time frame. The system also defines the mechanisms for evaluating the performance within the specified period within a pre-determined institutional framework.

PCs have been broadly classified under two systems—the French based systems and the signaling system. The French system was followed by France, Africa (Senegal, Benin, and Morocco), and Latin America. Under this system, weights were not allocated to the targets which added a high degree of subjectivity to the evaluation process, while in the signaling system, signals were sent to the managers in order to monitor the results of the contacts. This system originated in Pakistan and Korea and was adopted by many Asian countries (Pakistan, South Korea, and Bangladesh), Africa (Ghana, Nigeria, and Gambia), and Latin America. Initially,

Corresponding author: Ram Kumar Mishra, Ph.D. in public finance, senior professor, director, Institute of Public Enterprise,

Hyderabad, India; research fields: public sector policy and management, public finance, corporate governance, public private partnerships, and climate change. E-mail: [email protected].

Geeta Potaraju, Ph.D. in management, assistant professor, Centre for Governance and Public Policy, Institute of Public Enterprise, Hyderabad, India; research fields: good governance, public enterprise policy, citizen participation and governance tools, and public system studies. E-mail: [email protected].

DAVID PUBLISHING

the MoU system adopted in India was based on the line of French system; during its evolution, many features from the signaling system were adopted. Currently, the MoU signed between the public enterprises and the ministries consists of mission of the enterprise, its objectives, performance criteria, weightages assigned to each criterion and the period of contract and the mode of evaluation. The MoU system is based on the balanced score card approach, wherein all key factors in financial, financial are adequately represented.

The role and importance of these enterprises in a national economic growth changed considerably from being mere tools of fulfilling social objectives to being growth engines and contributing to economic prosperity of a nation. With the onset of the global financial crisis in 2008, for some countries, especially among the resource-rich emerging economies, the SOEs represented their main source of international capital as they accounted for one fifth of international mergers and acquisitions (Mehdi, 1985). The SOEs have emerged as an important source of international investment globally.

While there are some inherent problems that go along with these enterprises—they are usually very large in size with multiple control and accountability points which make them very difficult to govern. Therefore, the system of PCs was introduced at a time when many governments were facing troubles to manage performance of their enterprises. In this paper, the authors will focus on target setting process which is a key component of performance contracting system.

Target Setting Process

As a part of the process of PCs targets are set for both financial and non-financial parameters which are based on what the enterprise can reasonably achieve, given the expected policy environment, market situation, capital expenditures, and the level of delegation of financial powers to the enterprise. For each indicator, a rage of values is set so that performance can be graded, e.g., as excellent, good, fair, poor, or bad. There are some established methods for setting enterprise targets (Performance contracting for public enterprises, 1995).

(1) Inter-firm comparison: comparison of different firms in terms of their performance and profitability. Such a type of comparison is possible only when uniform costing is applied by all the firms which form a basis for comparison. The accumulated data regarding costs, prices, profits, etc., of different concerns are put in the form of consolidated statements and are made available to all the member-units so that they can make a comparative assessment of their achievements and weaknesses with those of others. This type of comparison helps in improvement in efficiency wherein each member-unit can try to improve its efficiency when on comparison with other member-firms it comes to know about its weak points. However, one of the key requirements of this method is the need for complete information;

(2) International comparisons of firms are not easy, because differences in market conditions, regulatory environment vary for each country. It is also not possible to comparison firms with other firms for monopoly enterprise, except where they are broken up regionally and the regional bodies can be compared. A combination of methods may be used for assessing public enterprises in each period.

simple projection of the past;

(b) Yardstick competition is applied by a target-setter knowing the unit costs in simi1ar enterprises. In Bangladesh, for example, a detailed system of comparing cotton textile mills is used by the Bangladesh Textile Mills Corporation. The target is set by reference to the average enterprise, or the most efficient enterprise, taking the best performance on each activity. The United Kingdom Audit Commission has a tradition of “inter-firm” comparisons of local authority performance, which indicates that such comparisons may be valid and useful, despite disputes on their interpretation (Geeta, 2000);

(c) Work study and management audit is also used to set up targets, which represent reasonably efficient performance, though this method is slow and costly. The United Kingdom Monopolies and Mergers Commission (MMC) carries out in-depth review of efficiency as required by the Department of Trade and Industry. The MMC examines the trend of performance indicators, such as unit costs and quality, and management processes for want of valid international or intra-national comparisons of performance indicators, it tends to conform to widely accepted standards of management practices.

Target Setting and Performance Evaluation of SOEs in India

In India, the process of the target setting and evaluation begins with the: (1) Department of Public Enterprises first, releasing MoU guidelines in the month of October/November; (2) based on the guidelines, draft MoUs are prepared by enterprises and submitted to their administrative ministries; (3) examination of draft MoUs is done by the MoU division of the Department of Public Enterprises and documents are handed over to the members of the task force (technical expert group outside government set up to oversee the MoU process); (4) MoU negotiation meetings are scheduled between the enterprise and task force that begin from January/February; (5) negotiation meetings end up with finalization of the MoUs with the task force (January/March) each year; and (6) all MoUs are signed before March 31 of every year (Public Enterprises

Survey 2011-12, 2011-2012).

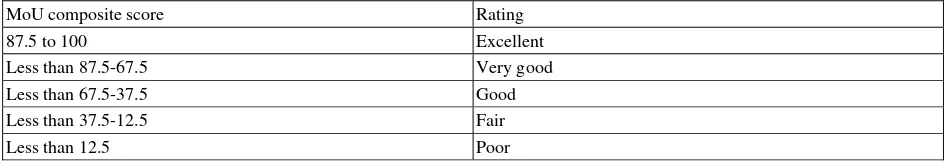

MoU Guidelines and Evaluation

Every year, MoU guidelines are issued by the MoU division of the government, taking into account the dynamic and complex environment in which the public enterprises operate. Based on the guidelines, the enterprises prepare the draft MoUs and from there, the MoU is negotiated and finally, the MoU is signed. The MoU guidelines form the first step of the MoU cycle. MoU evaluation process is based on the “Balance Score Card” approach and is a combination of “financial” and “non-financial” targets, having equal weightage in the overall scores. In the case of sick and loss making enterprises, the guidelines try to focus more on the non-financial indicators rather than the financial indicators and the slightly alter the ratio of the financial to non-financial weights. A five point grading scale is used to grade the enterprises—“excellent” to “poor”, based on the score they receive in the MoU score.

Financial Targets

the respective year and in conformity with those made by the Planning Commission, Ministry of Finance, Administrative Ministry/Department, and other statutory and regulatory bodies. In instances where the enterprises are found to be under-pitching, the task force or the Department of Public Enterprise will have the liberty to call upon their top management to give explanations for such under-pitching or gross over achievement. The basic targets are to be arrived at based on a combination of the performance of the enterprise over five preceding years and other factors such as: (1) capacity and its expansion; (2) business environment; (3) projects under implementation; (4) government policies; (5) external factors; and (6) company’s growth forecast (MoU guidelines 2015-16, 2015-2016).

Another important factor to be considered for the basic financial targets is the national/international benchmarking. In the extant MoU system, the basic targets are generally expected to be an ambitious growth over the performance of the enterprise in the preceding year, however, if the performance of the enterprise is found to be bad in the previous year, then a more realistic target based on the average performance of the previous three years is to be taken into account.

Non-Financial/Dynamic Targets

The non-financial targets are a little more difficult to determine and the guidelines specify that the non-financial targets must be Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Result-oriented, Tangible (SMART).

Non-financial targets in the MoU should be in the following categories: (1) Sector specific and enterprise specific targets;

(2) Initiatives for growth; (3) Capacity addition;

(4) Project management and implementation; (5) CAPEX—capital expenditure;

(6) Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and sustainability; (7) Research and development;

(8) Human resource management; (9) Risk management.

Corporate governance is a very important aspect in the existing system of MoU, where there are negative marks and penalties in scores for any enterprise found to be in non-compliance of the corporate governance norms which were specified by the government and for listed companies the Security and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) guidelines. Similar penalties and negative markings are also applicable to the non-compliance of the CSR guidelines, Department of Public Enterprise (DPE), Government of India guidelines, and other forms of non-compliance.

Grading

The MoU system when first introduced was based on the French Contracting System and it was later changed to the “signaling system” after a year and after 2004-2005, it was further refined to the “Balance Score Card” approach. The performance of the enterprises in the MoU system is scored on a 5 point index which is calculated as the aggregate of all the “actual achievements” as against the targets set in the 5 point scale.

Table 1

MoU Rating Scale

MoU composite score Rating

87.5 to 100 Excellent

Less than 87.5-67.5 Very good

Less than 67.5-37.5 Good

Less than 37.5-12.5 Fair

Less than 12.5 Poor

Issues and Challenges in Target Setting

Target setting process is one of the key activities of performance contracting system. A successful enterprise which is on the path of upward movement and aspires to be a leader in industry would adopt mechanisms for identifying realistic targets. Research has found out that SOEs world over have been grappling with this issue of target setting.

Broadly, the issues faced by enterprises can be categorized into the following:

Determining Performance Levels

There is a constant pressure on the management of public enterprises to raise the bar of performance each year. There is a general feeling among the enterprise managers that if they achieve a target in a year, their performance bar is raised in the next year. Therefore, there is a need to set realistic targets which can be achieved under given circumstances which have physical limits, such as capacity utilization, profitability, etc. Due to this reason, there is a tendency for the enterprises to set targets in such a way that it is very much within the reach of the enterprise. While setting targets, the enterprises make sure that their targets are neither too low which are easily achievable without effort nor too high which make them unachievable.

Information Asymmetry

Ideally, PCs must reduce the information advantage that enterprises have over the government and motivate enterprise officials through rewards or penalties (such as to pay bonuses or impose penalties) to achieve the targets (Shirley, 1995). In reality, the asymmetry of information between an enterprise and ministry allows the enterprise to get the targets it wants to set for itself. This asymmetry of information is taken advantage by the enterprise managers who use this information advantage to negotiate targets that were either hard for outsiders to evaluate or easy for them to achieve. In any case, performance is hard to evaluate, for example, when there are many targets or when targets change frequently or when the negotiations dragged on so long that targets were set equal to ex post performance, targets can be set soft.

The information advantage of the enterprise coupled with governments’ failure to give the bureaucrats responsible for negotiating the contracts and evaluating results the power, resources, and status they needed to face enterprise managers at a level playing field leads to poor target setting. Enterprises are therefore able to negotiate targets that they could achieve without making additional efforts to improve productivity. Here is a good example, the Government of Pakistan (Geeta, 2000) provides guidelines for setting targets as mentioned below:

(1) Efficient target setting to carried out in a participatory process. Without this approach, targets tend to take the form of formal directives, which are often overtly accepted and covertly resisted;

(3) Targets to be neither too low nor high. This would give wrong signals to the managers;

(4) Each enterprise must be looked at in its own unique environment which must be taken into account; (5) The targets must ensure that generation of surplus is significantly more than distribution by way of bonus;

(6) Targets must take into account the social tasks, which are taken up by the enterprises.

Ownership Model

The ownership model in the public sector, where politicians have many points of view and bureaucrats have many different agendas creates further problems in setting performance levels. Unlike the private companies, the public sector enterprises are susceptible to be used by political bosses for their personal benefits which may stand in contradiction to their progress to reach the declared performance targets.

Strengthening Target Setting Process

The success of the MoU exercise largely depends on the basic strength of target setting process. Such strength would largely depend on the initiatives outlined as under.

Generating continuous research evidence. Research evidence must be generated continuously for companies to set realistic as well as competitive targets as per their contracts. Empirical studies are carried out by countries to analyze the effect of such contracts on profitability and productivity and examine statistically the correlation between PCs and productivity so that evidence can be generated whether PCs actually improve efficiency. In a study conducted by the World Bank (Shirley, 1995), it found no pattern of improvement associated with the PCs in productivity or profitability trends. The study found no robust, positive association between PCs and productivity. An important question needs to be raised here—is it possible that PCs failed to improve productivity. A dedicated research group or an institution must continuously be involved in data collection from SOEs, conduct research and development for the benefit of SOEs, individually and collectively and disseminate results of study to all.

Strengthening governance mechanisms. Improving governance mechanisms go a long way in streamlining enterprise performance. Restructuring the board, which is driving force behind the success of an enterprise, is very critical. Research has shown that professionalizing the board improves the overall performance of enterprises especially in terms of achievement against the PCs. For example, Chile took up a successful experience in reforming its state enterprises and improving its efficiency as indicated below (Johnson & Beiman, 2007).

(1) Chile increased competition by ending state monopolies and barriers to entry, reducing import tariffs to 10% across the board, breaking up monopolies in sectors as electricity, and pushing state enterprises to contract out competitive activities under strict rules of competitive bidding;

(2) It placed state enterprises under private commercial law, and members of the boards of directors became liable for their decisions;

(3) Private parties were named to boards, and boards were kept small (five people) to reduce the political value of keeping companies public;

(4) The government eliminated all subsidies, transfers, and government guarantees for debts of state enterprises and instructed banks to lend to them under the same criteria as for private enterprises;

Stakeholder participation. Stakeholder participation is the key for efficient target setting. Targets should be negotiated between the government and management and should not be imposed. The benefits of participation are not confined to the government management interface. It is apparent that improvement of performance can arise only by changes in behavior at the operating level. Therefore, there should be an internal dialogue through all levels of the enterprise extending the corporate goal and incentives to divisions and sections of the enterprise.

Period of Contract

Period of contract is equally critical for efficiency in target setting process. Planning encompasses a future period of time necessary to fulfill through a series of actions and commitments made and the availability of the capital.

In Gambia, for instance, PCs have been for four years. They spell out the goals of the enterprise, and autonomy for the management. The targets are separately negotiated each year and signed at the technical level. These are the basis on which annual performance is evaluated and rewarded or penalized. In India, targets are made annually coinciding with the annual plans of the enterprises. While some production companies accepted the time span of one year, the companies which are in the construction and exploration business express their views differently. They prefer the contracts to be for a longer period at least for 24-36 months, which is minimum time period for completion of a project.

Strengthening Feedback Loop

Performance contracting is a cyclical process in which results are fed back to the government and public enterprise. This is done in order to make correction for short-term variances form contract and this process is called monitoring. This could be represented by the feed-back loop of control.

Case Study: Implementing Performance Incentives for SOEs in China

Economic Value Added (EVA) is a tool designed to give managers of SOEs better information to make decisions that create the greatest shareholder wealth. While EVA implementation has been mainly studied in Western companies from the perspective of improving economic efficiency, we look at the great possibility of introducing EVA as a part of Performance Management System. Studies reveal that some changes in managerial behaviour have also been seen with EVA implementation (Li, 2012). An EVA based performance assessment policy was introduced by the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State Council (SASAC), for 129 Chinese SOEs under direct administration of central government since 2010 as a part of the mission set out for SOEs under the 11th five-year plan (2006-2010) to “grow bigger and stronger”. The study shows that by the end of 2010, the net profit achieved by the 122 Central SOEs reached 848.89 billion yuan, sizeable given that total profit by all China’s SOEs was 21.37 billion yuan in 1998. The Central SOEs listed in the Fortune 500 have increased from six in 2003 to 38 in 2011.SASAC as investor encourages central SOEs to emphasize on value-creating and maximizing shareholder value. EVA method is being implemented since 2010 which flows as follows:

the cost of equity capital is deducted from NOPAT.

Positive changes have been reported to central SOEs after SASAC applying EVA to performance assessment. This has led to building up value management system, prudent in investment decision-making, attach importance in capital management and attach importance in research and development investment. In 2003, the net profit (NP) of 183 central SOEs is RMB140.2 billion yuan (USD$23 billion) with the rate of capital cost 5%, the total EVA is only RMB6.7 billion yuan (USD$1.1 billion). In 2014, the EVA of all the Central SOEs is RMB350 billion yuan (USD$58 billion).

South Korea Experience With Performance Evaluation System

South Korea has a total of 303 institutions which are designated as SOEs under the Act on the Management of Public Institutions. The Koreans have experimented and fine tuned their performance evaluation system over the years and now has a well-structured and effective performance evaluation system for their SOEs. The first stage of the broad transition was between the years 1984 and 2003 where the performance of public corporations was introduced under which included the CEO (chief executive officer) performance evaluation and innovation evaluation. The second stage of the transition of the performance evaluation system was between 2004 and 2007 when the performance evaluation of quasi-governmental organizations was introduced in addition to evaluation of public organizations which evaluated the CEO performance, innovation and additionally, the auditor’s performance was also evaluated. The last stage started from 2008 and continues presently which is the performance evaluation of SOEs system.

The broad monitoring system for SOEs in Korea has two parts. The first part is the performance evaluation system under which the following components of the SOEs are monitored, namely, SOE performance evaluation, CEO performance agreement and evaluation of the senior auditors. The second part of the monitoring of SOEs is the ALIO (All Public Information in One) system which is a system introduced to increase transparency through an information disclosure system.

The public institutions in Korea are evaluated by the Ministry of Strategy and Finance (MoSF) or the line ministries depending on the size and profitability of the corporations and organizations. The MoSF evaluates only the bigger public corporation or organizations which have self-generating revenue of more than 50% and also qausi-governmental organizations which have a self-generating revenue of less than 50%. With regards to size, the evaluation of the corporations and quasi-governmental organization is done by the MoSF only in case, the total employment is greater than or equal to 50 people. Public institutions which are non-classified and have less than 50 employees are evaluated by their respective line ministries.

The evaluation of the SOEs is conducted by a Performance Evaluation Unit which is a temporary team consisting of about 160 experts from varied fields like academics and research analysts, etc. The MoSF also organizes an independent team to evaluate the performance. Once the evaluation team evaluates the performance of the public institutions, the results are finalized by the Committee for Management of PIs (Performance Indicators). The public institutions may also have complaints and policy suggestions which are directed to the Research Centre for state-owned entities which further suggests the system improvements to the MoSF which go to the committee for management of PIs where they are deliberated and resolutions are passed and finally, the evaluation team approves and finalizes the system improvements.

non-quantitative indicators which are divided on 65%-35% ratio. For business administration, non-quantitative indicators include strategy planning, financial management, remuneration and welfare benefits, while the quantitative indicators include business efficiency, government recommending policy. As regards core businesses, the non-quantitative indicators include plan activities and performances and quantitative indicators include plan activities and performances.

The results of the evaluation are divided into six grades after they are converted to scores on a 100 scale. The six grades are S (superior), A, B, C, D, E (inferior). Based on the results of the performance evaluation, the incentive rate is decided. The range of the incentive rate varies from 0% to 250% of the monthly wage, depending upon the grade received in the evaluation. SOE employees’ incentives are determined by adding the institutional performance bonus and personal incentives. The Korean system also has a very unique penalty system where the MoSF in cases of low rated institutions may recommend the dismissal of CEO.

The evaluation system is linked to the incentive system (in the form of bonuses). The task force conducts the performance evaluation each year and the bonus size would vary between 0% and 500% of monthly wages depending on the evaluation results in the nine categories. The system also incorporates non-pecuniary incentives and sanctions. Awards are handed to the highest scoring enterprises while the enterprises that are performing poorly can have sanction (e.g., dismissal of top management) imposed on them. Finally, an important part of the entire system is the wide publicizing of the results of the performance evaluation in mass media. Public recognition plays an important role in Korean society and is a powerful motivational tool for performance of top management.

Balanced Score Card (BSC) Approach

The use of Balanced Score Card (BSC) Methodology for SOEs, is said to improve enterprise profitability, provide required guidance to enterprise managers using modern management concepts, methods, and tools, stimulate identification, analysis, and resolution of problems interfering with improvement of enterprise performance and most importantly build consensus and improves communication among management, employees, and stakeholders. The BSC tool is being used not only in developed economies, but in transitional economies as well. Having been successfully used to drive alignment and strategic results in the private sector, governments are increasingly using the BSC in government organizations and SOEs as part of an integrated strategy management process. Various types of SOEs use BSC tools to describe, measure, align, and manage their strategies.

individuals. As a result, company employees had clearer objectives, measures, and performance “targets”. Also, a variable pay incentive system was established while deploying the BSC Methodology. This led to an increase in employee motivation for improving business results. The company achieved significant improvements in vertical and horizontal alignment, as well as significant improvements in cross-departmental teamwork and cooperation as a result of its BSC implementation.

Measurable improvements in quantitative performance, as reported by Mr. Xia Pei Yun, General Manager of Jinshan Telecom, included the following (Xia, 2003):

(1) Jinshan Telecom’s 2003 growth rate was more than three times the Group Company’s growth rate. Jinshan grew by 14%, compared with the Group Company’s 4% growth rate (Jinshan was the first branch unit in the group company to deploy the BSC);

(2) Jinshan’s superior growth rate was enabled by reaching or exceeding strategic performance targets in the customer, process, and learning areas;

(3) Jinshan’s results on five performance measures met or exceeded targets: Key Account Satisfaction, Commercial Account Satisfaction, Repair Cycle Time, Connection to Internet Success, and Implementation of Planned Trainings.

Total Factor Productivity

Total Factor Productivity (TFP) is a composite measure of technological change and changes in the efficiency with which known technology is applied to production. The translog index of technology changes is based on a translog production function, characterization by constant returns to scale. In this method, two inputs Labour (L) and Capital (K) only, the total factor productivity growth (TFPG) can be estimated adequately. The studies show that growth in financial profitability is not necessarily always accompanied by an increase in TFP. Of the two, TFP is considered to be a superior method of evaluating performance. However, it is yet to gain acceptability in the SOEs as it does not support the managers’ to stake high performance claim, benefit from financial incentives and projecting brighter image. The complexity of the method and lack of capacity on the part of the regulators and managers to implement it has hindered TFP its popularity (Mishra, Nandgopal, Geeta, & Bulusu, 2001).

Conclusions

With the new government taking over in India in 2014, the focus has shifted on making the public enterprises more efficient and competitive so that they can face the stiff market competition. The MoU system is being made more transparent by using information technology and a new online MoU system is being designed and launched from the current year from October 2015-2016. This system will bring in greater scope for using the enterprise data for effective planning and decision-making by the government.

References

Geeta, P. (2000). Memorandum of understanding and public enterprises in India. PhD thesis. Submitted to Department of Business Management and Commerce, Osmania University, Hyderabad.

Johnson, C. C., & Beiman, I. (Eds.). (2007). Driving performance and corporate governance. Asian Development Bank.

Kaplan, R. (2001). Integrating shareholder value and activity-based costing with the balanced scorecard. Balanced Scorecard Report.

Mehdi, I. (1985). Setting targets for improving cost efficiencies in PE’s. Proceedings from the Conference on Cost Effective Management of PE’s in Karachi. July 14, Karachi.

Mishra, R. K., Nandgopal, Geeta, P., & Bulusu, N. (2001). Role of memorandum of understanding in public enterprise reforms. New Delhi: Vikas Publications.

MoU guidelines 2015-16. (2015-2016). Department of Public Enterprise, Government of India. Retrieved from

http://www.dpemou.nic.in/MOUFiles/MoU_GL_2015-16.pdf

Performance contracting for public enterprises. 1995. Development Support and Management Services, United Nations, New

York.

Public Enterprises Survey 2011-12. (2011-2012). Department of Public Enterprise, Government of India. Retrieved from

http://dpe.nic.in/sites/ upload_files/dpe/files/survey1112/survey01/vol1ch8.pdf

Shirley, M. (1995). Why performance contracts for state owned enterprises haven’t worked. World Bank Publication, Note No. 150, Public Policy for the Private Sector. Retrieved from http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EXTFINANCIALSECTOR/ Resources/282884-1303327122200/150shirl.pdf

Journal of US-China Public Administration, August 2015, Vol. 12, No. 8, 614-626 doi: 10.17265/1548-6591/2015.08.003

Impacts of Intellectual Capital on Profitability: An Analysis on

Sector Variations in Hong Kong

Michael C. S. Wong, Stephen C. Y. Li, Anthony C. T. Ku City University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

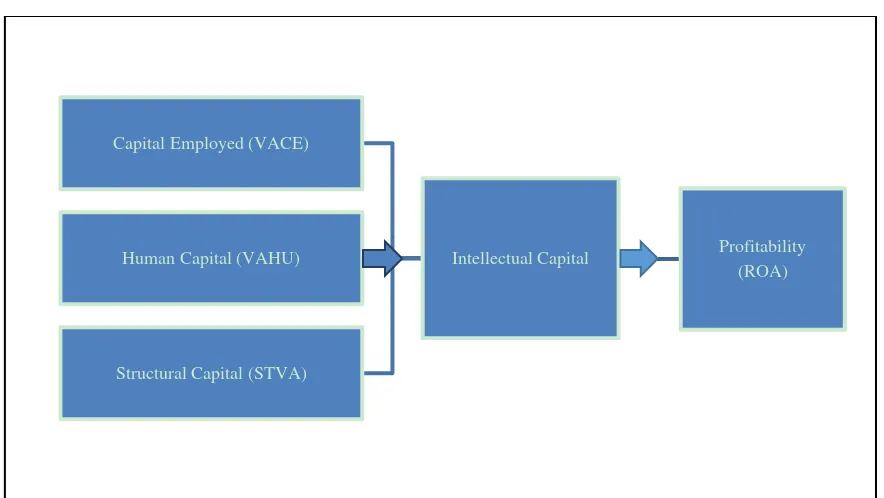

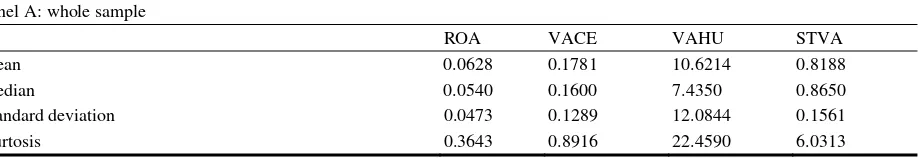

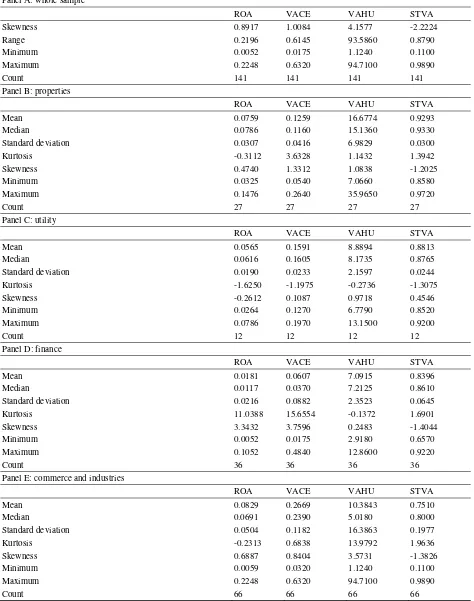

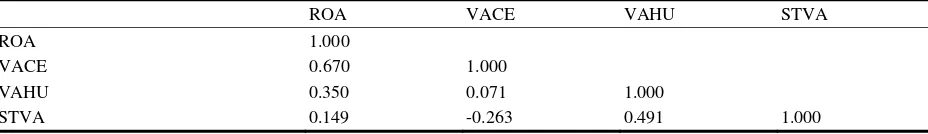

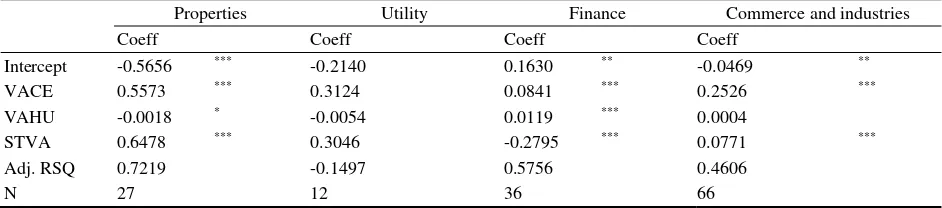

With the data from blue-chip companies listed in Hong Kong, this research finds that the three components of

intellectual capital, including Capital Employed Efficiency, Human Capital Efficiency, and Structural Capital

Efficiency, have strong impact on profitability. However, their impacts are not equally-weighted and are not

consistent in different sectors. The impact of Capital Employed efficiency is universal. However, Human Capital

Efficiency appears to be more important for companies in finance sector. Structural Capital Efficiency demonstrates

a very pronounced impact on companies in property sector. The results suggest that Pulic may have over simplified

impacts of intellectual capital. Also, previous studies may have ignored sector variation in the impacts of

intellectual capital. Future research is suggested to widen the research scope. The recommended future research

areas are to study the ways to improve the management of intellectual capital; to study other factors that mostly

affect the intellectual capital; and to study how the knowledge-based organizations benefited from the development

of intellectual capital.

Keywords: intellectual capital, profitability, knowledge-based economy, Hong Kong Stock Exchange Listed

Companies

Aim: The purpose of this study is to examine the relationship between intellectual capital and profitability as well as its impacts on companies in different sectors of Hong Kong.

Design/Methodology: Data are drawn from the companies included in the Hang Seng Composite Index, a commonly-used benchmark index for blue-chip stocks listed on Hong Kong Stock Exchange (HKSE).

Research limitations/implications: The study period covers annual reports of 2010-2013. An extended period is desirable for testing would raise the generalizability of this study. The current study only covered three years for the empirical test. It is recommended to extend the examination period to 10 to 20 years to raise the applicability of the future study.

Practical implications: The results suggest that intellectual capital is helpful to the management of the listed companies in Hong Kong.

Finding: It is observed that finance sector is efficient to leverage human capital to achieve better

Michael C. S. Wong, Ph.D., associate professor, Department of Economics and Finance, City University of Hong Kong; research fields: venture capital, financial markets, and enterprise risk management. E-mail: [email protected].

Corresponding author: Stephen C. Y. Li, Ph.D., senior lecturer, School of Continuing & Professional Education, City

University of Hong Kong; research fields: corporate governance, corporate finance, emerging markets, international trade and finance. E-mail: [email protected].

Anthony C. T. Ku, B.A., research assistance, School of Continuing & Professional Education, City University of Hong Kong; research fields: corporate governance, corporate finance, and dividend policies. E-mail: [email protected].

DAVID PUBLISHING

D

DAVID PUBLISHING