Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:25

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

An Evaluation of Critical Thinking Competencies in

Business Settings

Christopher P. Dwyer, Amy Boswell & Mark A. Elliott

To cite this article: Christopher P. Dwyer, Amy Boswell & Mark A. Elliott (2015) An Evaluation of Critical Thinking Competencies in Business Settings, Journal of Education for Business, 90:5, 260-269, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1038978

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1038978

Published online: 13 May 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 246

View related articles

An Evaluation of Critical Thinking Competencies in

Business Settings

Christopher P. Dwyer, Amy Boswell, and Mark A. Elliott

National University of Ireland, Galway, IrelandAlthough critical thinking (CT) skills are usually considered as domain general (Gabbenesch, 2006; Halpern, 2003), CT ability may benefit from expertise knowledge and skill. The current study examined both general CT ability and CT ability related to business scenarios for individuals (a) expert in business, (b) novice in business, and (c) with no business experience, as well as the effects of educational background on both general and business-related CT. Results are discussed in light of research and theory on CT and business, and implications for future research are discussed.

Keywords: critical thinking applications, critical thinking skills, expertise

Critical thinking (CT) has long been considered an impor-tant part of psychology in education, the workplace and in everyday settings. Though CT is context general (Butler et al., 2012; Gabbenesch, 2006; Halpern, 2003), in that it consists of the same components in an academic context as it does in everyday settings, a vast majority of extant research focuses on its application in educational settings, particularly in universities, across a wide range of domains (Alexander & Judy, 1988; Braun, 2004; Butchart, Bige-low, Oppy, Korb, & Gold, 2009; Dwyer, Hogan, & Stew-art, 2011, 2012; Heijltjes, van Gog, Leppink, & Paas, 2014; King, Wood, & Mines, 1990; Smith, 2003; Whitten, 2011). However, there is a dearth of research on individu-als’ CT development and performance after university, at a graduate level and especially, in the working world.

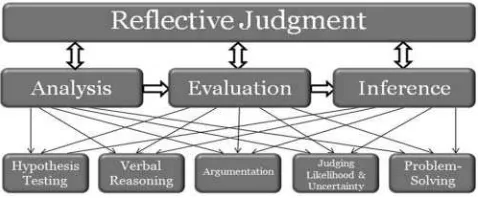

CT is a metacognitive process, consisting of the skills of analysis, evaluation, and inference; that, through pur-poseful, reflective judgment, increases the chances of pro-ducing a logical conclusion to an argument or solution to a problem (e.g., Dwyer et al., 2012, 2014, 2015). Recent conceptualizations of CT have also added greater focus on the application of CT skills to real-world scenarios, such as those involving hypothesis testing verbal reasoning argument analysis judging likelihood and uncertainty and problem solving (e.g., Butler et al., 2012; Halpern, 2003, 2010). Notably, CT skills transcend specific subjects or

disciplines and that a context is necessary in which to learn and apply these skills (Facione, 1990). Though, it is widely accepted that CT is applicable across a wide range of disciplinary areas, there is little consensus about whether CT is a set of generic skills that apply across sub-ject domains or if it is influenced by the subsub-ject domain and/or context in which it is taught (Ennis, 1989). While some theorists suggest that thinking skills are context bound and do not transfer across academic domains (Glaser, 1984), a large body of research has reported suc-cessful instruction in CT, across domains (Ennis, 1989; Gabbenesch, 2006; Hitchcock, 2004; Lehman & Nisbitt, 1990; Reed & Kromrey, 2001; Rimiene, 2002; Rubinstein & Firstenberg, 1987; Solon, 2007). Consistent with this domain-generality perspective of CT (Gabbenesch, 2006), it was hypothesized in the present research that CT would be a fundamental practice in business settings.

CRITICAL THINKING IN BUSINESS

Research indicates that studying business requires a strat-egy more extensive than mere rote memory (Whitten, 2011); rather, it is higher order cognitive skills, such as CT, that allow for success in business. That is, the teaching of CT in higher education has been identified as an area that requires exploration and development (Association of American Colleges & Universities, 2005; Australian Coun-cil for Educational Research, 2002; Higher Education Qual-ity Council, 1996), as such skills are needed to allow

Correspondence should be addressed to Christopher P. Dwyer, National University of Ireland, School of Psychology, Arts Millennium Building Extension, Co. Galway, Ireland. E-mail: cdwyer@nuigalway.ie JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS, 90: 260–269, 2015 CopyrightÓTaylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1038978

students to go beyond simply memorising information, to actually gaining a more complex understanding of the information being presented to them (Halpern, 2003). CT skills are not only important in the academic domain, but also in social, interpersonal, and business contexts where adequate decision making and problem solving are neces-sary on a daily basis (Ku, 2009). Good critical thinkers are more likely to get better grades and are often more employ-able as well (Holmes & Clizbe, 1997; National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Institute of Medicine, 2005).

Business, as conceptualized in the present study, is an organization or economic system engaged in commercial, industrial, or professional activities aimed at the attainment of value from assets through exchanging goods or services for one another or for money. Consistent with the previous perspective, CT and problem solving have been identified as being crucial to workforce preparedness and business

success (American Management Association [AMA],

2010). The ability to think critically is an important skill that employers look for in employees, as it enables individ-uals to act independently; analyze and evaluate data in order to draw conclusions; and thus, make the inferences, judgments and decisions necessary to take action (Deane &

Borg, 2011). For example, the council for Industry and

High Educationrated CT and decision-making skills as the most important skill (67%) sought for in future employees (Archer & Davison, 2008); and even more recently, in a study conducted on 400 senior human resources professio-nals, CT was ranked as the most important skill for employ-ees to possess (Deane & Borg, 2011).

The ability to apply CT skills to a particular problem implies a reflective sensibility and the capacity for reflective judgment, which refers to the understanding of the nature, limits, and certainty of knowing; and how this can affect how individuals defend their judgments and reasoning (King & Kitchener, 1994; see Figure 1 for the integration of CT skills, applications, and reflective judgment). However, though judgment research often focuses on the benefits of reflective judgment and the limitations of intuitive judgment (i.e., automatic cognitive processing which generally lacks effort, intention, awareness, or voluntary control—usually

experienced as perceptions or feelings; Kahneman, 2011; Tversky & Kahneman, 1974; West, Toplak, & Stanovich, 2008), research indicates that individuals in business and finance often fall prey to this type of intuitive judgment (see Kahneman, 2011).

EXPERTISE AND CRITICAL THINKING

The cognitive biases and heuristics that stem from reliance on intuitive judgment are influenced by individual’s famil-iarity and salience with a topic (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974); and in turn, influence the manner in which individu-als evaluate, assess probabilities and form judgments and conclusions. Interestingly, as alluded to previously, the use

of these heuristics and biases are not limited to na€ıve

sub-jects—experienced individuals have been found to make similar errors in judgments, perhaps explaining why indi-viduals in business and finance often fall prey to this type of intuitive judgment. However, individuals expert in a par-ticular domain of interest tend to use logic rather than intui-tion (Kahneman & Frederick, 2002) and they tend to avoid making elementary errors, such as the gambler’s fallacy (i.e., which inexperienced people tend to make). With that said, even experts’ intuitive judgments are still subject to similar fallacies (Tversky & Kahneman, 1974).

Though the line of thought described previously may come across contradictory (i.e., experienced individuals, such as those in business and finance, tend to use logic rather than intuition, but still succumb to heuristics and biased thinking), the potential for such contradiction can be

clarified by the distinction between experience and

exper-tise. For example, though experience is the critical

compo-nent of expertise, within the field of judgment and decision-making research, experience is very often observed to be unrelated to the accuracy of expert judgments and sometimes negatively correlated with accuracy (Goldberg, 1990; Hammond, 1996; Kahneman, 2011; Stewart, Heide-man, Moninger, & Reagan-Cirincione, 1992), perhaps as a result of overconfidence (Kahneman, 2011) or perhaps as a result of experience in doing the wrong thing (Hammond, 1996). On the other hand, while CT skills are argued to be intrinsically general in nature as an everyday skill (Deane & Borg, 2011; Gabbenesch, 2006) and applied to a wide range of contexts and domains, research has found that individuals with expertise or domain-specific knowledge in a particular field will perform better on problem solving, informal reasoning and CT tasks specific to that field (Cheung, Rudowicz, Kwan, & Yue, 2002; Chiesi, Spliich, & Voss, 1979; Graham & Donaldson, 1999; Voss, Blais, Means, Greene, & Ahwesh, 1986); perhaps as a result of being better able to evaluate the strengths and weaknesses of a given perspective due to more domain-specific knowledge.

FIGURE 1. Integration of critical thinking skills, applications and reflec-tive judgment (Dwyer, Hogan, & Stewart, 2014; Hogan, Dwyer, Noone, Harney, & Conway, 2014).

However, another factor to consider in overcoming the previous contradiction is the nature of the task (Hamm, 1988; Hammond, 1996), given that tasks vary with respect to the complexity, ambiguity and presentation of the task structure and content (Hamm, 1988). That is, there also exists a continuum between reflection-inducing tasks and intuition-inducing tasks (Hammond, 1996). For example, in an ill-structured problem (i.e., a problem that does not have one single 100% correct answer), experience may not necessarily aid the decision-making process given the associated uncertainty. However, in a well-structured prob-lem, where there is only one correct solution, relevant experience in the domain associated with the problem will aid the decision-making processes, perhaps automatically, because the individual can respond based on factual knowledge. Based on that logic, in the event that an ill-structured problem is encountered (as is often the case in CT), more reflective judgment might be the only option in search for a reasonable solution.

THE PRESENT STUDY

Given the debate regarding domain generality of CT and the type of thinking necessary for higher-order judgments, particularly those in business-related settings, the purpose of the current study was to examine the relationship between expertise in a particular domain (i.e., business) and CT performance. As past research indicates, that there is a relationship between CT ability and the context in which it is assessed (e.g., Cheung et al., 2002); and that experience (distinct from expertise) is often unrelated to accuracy in judgment making (Goldberg, 1990; Hammond, 1996; Kah-neman, 2011; Stewart et al., 1992) it was hypothesized that:

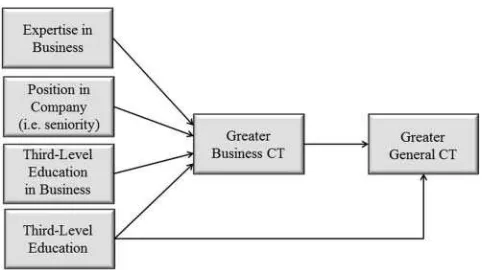

Hypothesis 1(H1): Those expert in business (Expert Group) would outperform both those less experienced (Novice Group) and those with no experience (Control Group) on business-related CT tasks; and there would be no dif-ference in business-related CT performance between those in the novice group and those in the control group.

This hypothesis is also supported by past research that found enhanced (context-dependent) reasoning and prob-lem solving resulting from the development of specialized (i.e., domain-specific) knowledge and reasoning schemas, as well as domain-specific concept-representation systems, over years of learning and experience (Chase & Simon, 1973; Chi, Glaser, & Rees, 1982). Given that the previous rationale is presented from the perspective that CT is domain-general and a transferable set of skills, it was also hypothesized that:

H2: Those who scored higher on business-related CT would

also score higher on general CT.

Also consistent with the previous rationale, previous research indicates that though there is a strong link between the higher-order thinking (such as CT) and higher educa-tional levels of business owners (Barringer & Jones, 2004), this relationship is limited to managerial roles in business and not necessarily the operational roles of business owners (Dobbs & Hamilton, 2007); thus, it was hypothesized that:

H3: Individuals holding more senior positions in a company

(e.g., managers and/or supervisors) would score signifi-cantly higher on business-related CT than company employees.

Notably, CT skills can be learned (Dwyer et al., 2012; Halpern, 2003; Marin & Halpern, 2011), which is impor-tant, particularly in educational settings, because they allow for individuals to stretch beyond simple retention of infor-mation to actually gaining a more complex understanding of the information being presented (Dwyer et al., 2012; Halpern, 2003). Furthermore, given that CT develops over an academic career (Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991), another hypothesis was that:

H4: Those with a third-level education would outperform

those without, in both general CT ability and business-related CT.

In addition to the rationale pertaining to domain-specific knowledge and expertise, as CT is often endorsed by busi-nesses to be taught in third-level education, particularly in business schools, and is also considered a vital prerequisite for business-related employment positions (AMA, 2010; Archer & Davison, 2008; Deane & Borg, 2011); the final hypothesis in the current study was that:

H5: Those with a business-related education would score

significantly higher on business-related CT than those with a non–business-related education.

Based on these hypotheses discussed, Figure 2 visually represents the relationships among the expected outcomes.

METHOD

Design

For the purpose of this study, a between-subjects quasiex-perimental design was used. A series of nonparametric

tests (i.e., Mann-WhitneyU and Jonckheere-Terpstra test)

were used (as the data were not normally distributed and parametric test equivalents could not be used), to test the hypotheses that (a) business expertise would predict enhanced scores on the business-related CT assessment, (b) CT would be generalizable across domains and that

262 C. P. DWYER ET AL.

those who scored higher on business-related CT would likewise score higher on the general CT assessment, (c) those with a third-level education would outperform those without on both business-related and general CT, (d) the presence of a business education would result in higher scores on a business-related CT assessment, and (e) and the position held in a company would result in differing performance on CT assessments. Correlations were also conducted using Spearman’s rho, where adjustments were made on the alpha levels to avoid making a type I error.

The alpha level was altered from p < .05 to p < .003,

based on the 15 pairwise comparisons.

Participants

Participants (N D 166), worldwide, were between 18 and

69 years old (MD30.1 years,SDD16.55 years).

Thirty-six percent of this sample completed both assessments (nD

60). There was a relatively even distribution between men

(nD27) and women (nD33). With respect to educational

background, in 29% of cases the completion of secondary or high school was the highest level of education achieved, 23.3% held undergraduate degrees, and 23.4% held post-graduate or doctoral degrees. A measure of salary was taken

with a range from€10,000 (or equivalent) to€118,000 per

annum (M D €32,750; SD D €28,430). Participants were

divided into three groups based on expertise in business: (a) nonbusiness people, who acted as the control condition

(n D30); (b) novices, who had less than five years’

busi-ness experience (N D16); and (c) experts who had more

than five years’ business experience (n D14), which

pro-vided a representative sample of business (n D 30) and

nonbusiness people (n D30). Participants were informed

about the nature of the study prior to participation and advised that they were able to withdraw from participation at any time. A complete debriefing was provided to partic-ipants at the end of the study. To ensure confidentiality, participants were identified by an assigned identification number only.

Materials

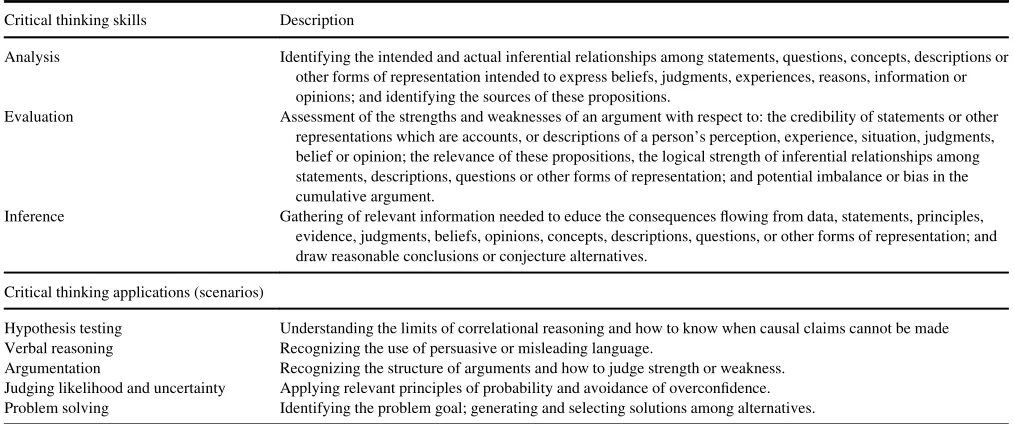

Two CT assessments (i.e., 60 items each) were developed for this study (see Figure 3 for a sample question from each), and were adapted from existing CT models and assessments—primarily the Halpern Critical Thinking Assessment (HCTA; Halpern, 2010), the California Critical Thinking Test (CCTST; Facione, 1990), and the Assess-ment Innovation Critical Thinking Test (Elliott & Dwyer, 2013). Both CT tests assess the three core CT skills (i.e., analysis, evaluation, and inference; see Table 1) outlined in the Delphi Report (i.e., 20 items each), applied in five real-world scenarios related to hypothesis testing; verbal reason-ing; argumentation; judging likelihood and uncertainty judgment; and problem solving (Halpern, 2003, 2010; see Table 1). That is, the first test assesses general CT (i.e., in the context of general, real-world scenarios). The second test assesses the same five applications in business-related scenarios (e.g., problems and questions faced by businesses on a day to day basis [i.e., those related to sales, marketing, distribution, and human resources]).

Cumulatively, each test consisted of five scenarios (i.e., each of the five applications) with 12 questions (i.e., four for each of the three CT skills), in which four possible answers to each question were provided in an multiple-choice questionnaire format. Only one option in each set of four answers was correct. The tests were structured and developed in a manner suitable to the population as a whole, regardless of background, for purposes of ensuring reader clarity and comprehension of the materials pre-sented. Cronbach’s alpha was used to assess the reliability of the test as a whole, including both parts (i.e., 120 items), yielding an alpha level of .724, which is considered reli-able. Separate reliability tests were conducted on the

gen-eral CT test (Cronbach’s a D .68) and business CT test

(Cronbach’s a D .67), both of which are considered

acceptable.

Procedure

Participation was advertised via personal contacts, online networks, local business people, personal contacts, and the National University of Ireland, Galway. Respondents will-ing to participate were (a) informed about the nature of the study prior to participation, (b) advised that they were able to withdraw at any time, and (c) were sent a link directly to the online testing website, via Fluid Surveys. Participants completed the tests online at a time and place that suited them. Assessment began with a short demo-graphic questionnaire, which asked questions regarding age, gender, education level, area of study, country of resi-dence, salary, socioeconomic group, and business-related questions (if applicable) such as business size, role in busi-ness, length of time working in busibusi-ness, and domain of business. Next, participants completed the two CT tests, FIGURE 2. Relationships among the expected outcomes.

which spanned 120 items over 10 scenarios (again, see Materials section for further details). Guided instructions were provided throughout with respect to the questions and scenarios. Cumulatively, the tests took 2 hr to

complete. Participants were allowed to stop the assess-ment and save their progress in order to come back at a later time. However, participants were advised to not take longer than a 2-hr break. Participants were also

TABLE 1

CT Skills and Scenarios (Adapted From Dwyer et al., 2014; Elliott & Dwyer, 2013; Facione, 1990; Halpern, 2010)

Critical thinking skills Description

Analysis Identifying the intended and actual inferential relationships among statements, questions, concepts, descriptions or other forms of representation intended to express beliefs, judgments, experiences, reasons, information or opinions; and identifying the sources of these propositions.

Evaluation Assessment of the strengths and weaknesses of an argument with respect to: the credibility of statements or other representations which are accounts, or descriptions of a person’s perception, experience, situation, judgments, belief or opinion; the relevance of these propositions, the logical strength of inferential relationships among statements, descriptions, questions or other forms of representation; and potential imbalance or bias in the cumulative argument.

Inference Gathering of relevant information needed to educe the consequences flowing from data, statements, principles, evidence, judgments, beliefs, opinions, concepts, descriptions, questions, or other forms of representation; and draw reasonable conclusions or conjecture alternatives.

Critical thinking applications (scenarios)

Hypothesis testing Understanding the limits of correlational reasoning and how to know when causal claims cannot be made Verbal reasoning Recognizing the use of persuasive or misleading language.

Argumentation Recognizing the structure of arguments and how to judge strength or weakness. Judging likelihood and uncertainty Applying relevant principles of probability and avoidance of overconfidence. Problem solving Identifying the problem goal; generating and selecting solutions among alternatives.

FIGURE 3. Examples of questions from the business-related and general CT assessments. 264 C. P. DWYER ET AL.

advised not to seek aid or guidance from others. As par-ticipants were unaware of the identities of others taking the assessments, it was not possible for them to confer. In order to control for order effects, the questionnaire was counterbalanced with the business and general sce-narios randomly ordered throughout (e.g., Scenario 1: general; Scenario 2: business, Scenario 3: general). A complete debriefing was administered to participants upon completion.

RESULTS

Means and standard deviations are presented in Table 2. A

series of nonparametric tests (Mann-WhitneyUand

Jonck-heere-Terpstra tests) were used to examine the effects of business experience (i.e., those with business experience and those without) and business expertise (i.e., business experts, business novices, and no-business controls) on both general CT and business-related CT. Results from the TABLE 2

Descriptive Statistics Regarding CT Performance in Business-Related and General CT

Business-related CT General CT

N M SD M SD

Business experience 30 231.94 43.55 234.72 61.35

No business experience 30 187.2 49.31 211.94 51.68

Expert 14 211.94 51.68 235 57.23

Novice 16 211.67 43.73 234.4 67.25

No expertise 30 187.2 49.31 211.94 51.68

College degree 28 231.25 36.62 242.26 60.09

No college degree 32 190.63 55.27 206.77 50.20

Business-related college degree 43 207.56 52.64 221.32 56.85

Non–business-related college deg. 17 214.71 49.08 228.43 60.24

Supervisors/managersSupervisors/managers 31 214.25 56.36 234.41 59.03

Employees 9 204.63 22.09 203.70 53.38

FIGURE 4. Business-related and general CT performances of business experts, novices and controls.

Mann-Whitney U tests revealed that those with business experience scored significantly higher on business-related

CT assessment (UD231.5,p <.001) than those without.

There was no effect of business experience on general CT. Results from the three-level Jonckheere-Terpstra tests revealed a significant effect of business expertise on the

business-related CT test, J(2) D 847.5, z D 3.974, p <

.001, where experts (median D258.3) scored significantly

higher than both novices (median D 200) and the control

condition (medianD187.5; see Figure 4). There were

nei-ther significant differences between Novices and controls on business-related CT, nor among the three groups on general CT performance.

Additional analysis was conducted in order to assess CT performances of individuals with a college education, in

which results of a Mann-Whitney U was 290 (zD –2.34,

p <.019), indicating that general CT ability was mediated

by a college education. Specifically, those with a college

education (medianD245.83) performed significantly better

than those without college education on general CT

(medianD204.16). With respect to the business-related CT

assessment, the Mann-Whitney U was 237 (z D –3.132,

p<.002), in which those with a college education (median

D 241.67) also significantly outperformed those without a

college education (medianD183.3).

Two subsequent Mann-WhitneyUtests were conducted

in order to evaluate the effects of college education type (business-related college education and non–business-related college education) on both business-non–business-related and general CT performance. Results from the Mann-Whitney

U revealed that those with a business degree performed

significantly better on business-related CT than those with

a non–business-related degree, U(59) D202, z D–2.017,

p D .044. There was no effect of college education type

on general CT.

Furthermore, two Jonckheere-Terpstra tests were con-ducted in order to evaluate the effects of one’s role in busi-ness on busibusi-ness-related and general CT performance, in which results revealed a significant effect of role in

busi-ness on busibusi-ness-related CT performance (J D 32.0, z D

–3.337, p < .001) in which supervisors and managers

(median D258.3) performed significantly better on

busi-ness-related CT than employees (medianD200). However,

there was no effect of role in business on general CT performance.

Correlational analyses were conducted in order to iden-tify determinants of business performance and general CT performance. In order to avoid type 1 errors, the alpha level of .05 was adjusted to .003 for Spearman’s rho analyses (i.e., by dividing the alpha level by the 15 tests). Results revealed that performance on the business-related CT test was found to have a strong positive correlations with age,

r(58)D.59,p<.001, and experience in business,r(58)D

.50,p<.001, and a moderate positive correlation with both

education level,r(58)D.51,p<.001, and salary,r(58)D

.34,p<.05, in a two-tailed test. On the other hand, general

CT performance was correlated with performance in the

business scenarios,r(58)D.51,p <.001; education level,

r(58)D.34,p <.05; and age,r(58)D.43,p<.01.

How-ever, the general CT test scores were not correlated with

salary, r(58) D.17, p<.05. Notably, the two CT

assess-ments were significantly correlated,r(58)D.51,p<.001.

All correlations are presented in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Results from this series of experiments suggest that though critical thinking is a domain-general ability, domain-spe-cific scenarios in which CT is required is facilitated by domain-specific expertise; and that though general CT and business-related CT are strongly related abilities (i.e., sig-nificantly correlated in the present study), they are distinct depending on the background expertise, experience, educa-tion, and employment role of individual test takers. Specifi-cally, results revealed that though there was no difference between those with and without business experience on general CT, those with business experience scored signifi-cantly higher on the business-related CT assessment than those without. This finding was further elaborated by the subsequent finding that those with business expertise (i.e., those with five or more years working in a business-related field) scored significantly higher on business-related CT than novices (i.e., less than five years working in a busi-ness-related field), as well as those without business experi-ence. Notably, there was no significant difference in the business-related CT performance of novices and those without business experience; which, along with the previ-ous finding and extant research (e.g., Cheung et al., 2002), suggests that expertise has a greater impact on business-related (i.e., domain-specific) CT than mere experience.

This perspective is also consistent with past research indicating that content-specific knowledge possessed by experts is associated with specialized reasoning schemas and superior reasoning regarding related content (Chi et al., 1982; Chiesi et al., 1979). Similarly, the use of effective and appropriate strategic knowledge, such as CT, is influ-enced by domain-specific knowledge (Alexander & Judy, TABLE 3

Correlations (Spearman’sr)

1 2 3 4 5 6

1. Business CT — 2. General CT .51** — 3. Business experience (years) .50** .22 — 4. Age .59** .43* .67** — 5. Education level .51** .34 .38* .53** — 6. Salary .34 .17 .53** .56** .27 —

*p<.003. **p<.001. 266 C. P. DWYER ET AL.

1988). Notably, these findings, to some extent, replicate those of Voss et al. (1986), who found that higher levels of domain-specific knowledge resulted in superior informal reasoning performance of those expert/experienced in the relevant domain in comparison with those who possessed little or no knowledge in that domain.

Results also supported the hypothesis that those with a college education, regardless of area studied, would outper-form those without a college education on general CT and business-related CT. With respect to general CT, this find-ing is consistent with previous research by Pascarella and Terenzini (1991), who found that CT develops over an aca-demic career, particularly during college. With respect to business-related CT, results indicate that perhaps, there was a transfer of knowledge from general CT to business-related CT, particularly for those with a college education. That is, those with a college education were able to generalize their CT abilities from broader domains to those more specific, such as business. Notably, it may be that the performance of those with a college education was greater than those without because a number of individuals’ education, within the former cohort, was business related, given that those with a business-related college education outperformed those with a non–business-related college education on business-related CT. However, this possibility is unlikely given that there was no difference between a business-related college education and non–business-business-related college education on general CT. Nevertheless, findings regarding the transferability of general CT ability to business-related CT as a result of college education must be interpreted with caution and require further research.

Notably, though CT has been considered an important aspect of a college education and much research has inves-tigated this perspective (Braun, 2004; Halpern, 2003; Pas-carella & Terenzini, 1991; Whitten, 2011), further research is required on the role of education in business-related CT settings. With that said, however, results from the current study are consistent with previous research in that immer-sion in business taught methods and strategies led to the development of related CT skills (e.g., Jones, 2007) and college education is associated with enhanced CT levels (Alvarez-Ortiz, 2007; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991). Thus, a college education, regardless of field, was as an indicator of improved CT in both the general and business-related CT assessments.

Finally, results from this study also yielded a significant effect of role in business on business-related CT perfor-mance, revealing that managers and supervisors of busi-nesses scored significantly higher on the business-related CT assessment than business employees, but not on general CT performance. These findings indicate that while there were no significant differences between groups on general CT ability, the significantly better performance of managers and supervisors on business-related CT might be facilitated by expertise in business (i.e., with respect to time) or age,

which were also found to be significant predictors of enhanced CT abilities. Results also suggest that while man-agers and supervisors are no better at general critical think-ing than employees, in scenarios directly related to business, in which business schemata or domain-specific knowledge is a potential advantage (Alexander & Judy, 1988; Chi et al., 1982; Jones, 2007; Voss et al., 1986), the expertise associated with higher roles in business elicit enhanced business-related CT. This is further interesting to consider, in tandem with this study’s previously discussed findings regarding education, as research has found that higher educational levels of business owners results in higher cognitive abilities, but that such abilities are limited to the managerial and not the operational roles of business owners (Dobbs & Hamilton, 2007). However, while most business owners who took part in the present study do not hold a higher education degree, those with more expertise and experience yielded higher scores on CT assessments.

Though a number of interesting results were yielded in the present study, there were also several limitations that require consideration. First, the sample size limited the effi-cacy of intragroup comparisons and subscale analyses that could potentially have helped explain and elaborate some of the more interesting findings (e.g., effects of expertise, experience, and education on analysis, evaluation, and inference competencies). One notable example is that of potential differences between manager–supervisors and employees resulting from differences in education. Though results revealed that there was an effect of both role in busi-ness and education, due to the small sample size it was not statistically feasible to further split groups, in order to assess whether or not role was mediated by education.

Due to time constraints on the current research, obtain-ing additional participants was not feasible. Given the lim-ited sample size, it is recommended that further, larger scale research be conducted on the evaluation of both gen-eral and business-related CT competencies as a result of expertise in business, experience (i.e., with respect to both employment and education), as such research could poten-tially shed light on the CT abilities cited as a vital

prerequi-site for business-related employment positions (AMA,

2010; Archer & Davison, 2008; Deane & Borg, 2011). Spe-cifically, formulating a CT model that businesses could use to assess CT competencies could allow for practical appli-cations for the hiring and training of employees, managers and supervisors.

The second limitation that requires consideration is that of CT subscale performance. Perhaps potential differences among groups on CT subscales (i.e., those associated with CT skills: analysis, evaluation, inference; and CT applica-tions: hypothesis testing, verbal reasoning, argumentation, problem solving, and judging likelihood and uncertainty) could have elaborated on the effects observed in the current study and perhaps pointed to specific CT competencies indicative of business-related thinking. However, without

adequate exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses (which is currently underway), it would be irresponsible, on the part of the authors, to report and speculate on such potential differences.

In summary, results from the current study indicate that though critical thinking is a domain-general ability, domain-specific scenarios in which CT is required (i.e., business related) is facilitated by domain-specific exper-tise; and that though general CT and business-related CT are strongly related abilities, they are distinct depending on the background expertise, experience, education and employment role of individual test-takers. Specifically, results revealed that though there was no difference between those with and without business experience on general CT, those with business experience (i.e., both experts and novices, cumulatively) scored significantly higher on the business-related CT assessment than those without. However, this effect was accounted for by the inclusion of experts as those with business expertise (i.e., those with 5 or more years working in a business-related field) scored significantly higher on business-related CT than both novices (i.e., less than five years working in a business-related field), as well as those without business experience; and because there was no difference in perfor-mance between novices and controls.

In addition, results revealed that those with a college education, regardless of area studied, outperformed those without a college education on both general and business-related CT. However, the enhanced performance of those with a college education on business-related CT may have been a result of the inclusion of individuals with a business-related college education, an interpretation consistent with the finding that those with a business-related college educa-tion scored significantly higher than those with a non–busi-ness-related college education on businon–busi-ness-related CT. Finally, results revealed that managers and supervisors of businesses scored significantly higher on the business-related CT assessment than business employees.

Though the current research yielded interesting findings that are particularly telling about the nature of business education, experience and related CT competencies; they also aid in the identification of necessary, future research to further expand on the nature of business-related CT. For example, future research should compare the effects of specific, business education interventions (e.g., ness-focused CT training, general CT training, and busi-ness education without CT) on both busibusi-ness-related and general CT. Another example of necessary, future research is to investigate potential benefits of enhanced CT performance in real-world business scenarios and academic, business-education scenarios. Such research, in tandem, has the potential to provide business academ-ics and executives alike with valuable information

regarding inputs that they can help develop and

facilitate.

In conclusion, though results from the current study indi-cate that critical thinking is a domain-general ability, it also appears that domain-specific knowledge in business facili-tates business-related CT. Similarly, findings also indicated, to some extent, that CT skills are transferable from that of general CT ability to business-related CT, a link that is con-sistent with past research (e.g., Royalty, 1995) and supports the perspective that CT is generalizable across subjects (Alexander & Judy, 1988; Butler et al., 2012; Dwyer et al., 2014; Halpern, 2003). Thus, while CT is a learning objec-tive without specific subject matter (Abrami et al., 2008), extant research suggests that the greatest potential benefits in CT development comes from the study and application of CT in a study area of particular interest (Graham & Donaldson, 1999), such as those in the business world. Though future research has been recommended, the current study has provided further support for the relationship between general and business-related critical thinking and the importance of both expertise and education in relevant critical thinking competencies.

REFERENCES

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis.Review of Educational Research,78, 1102–1134.

Alexander, P. A., & Judy, J. E. (1988). The interaction of domain-specific and strategic knowledge in academic performance.Review of Educa-tional Research,58, 375–404.

Alvarez-Ortiz, C. M. A. (2007)Does philosophy improve critical thinking skills?Melbourne, Australia: University of Melbourne Department of Philosophy.

American Management Association (AMA). (2010).AMA 2010 critical skills survey. Retrieved from http://www.amanet.org/news/AMA-2010-critical-skills-survey.aspx

Archer, W., & Davison, J. (2008). Graduate employability: What do employers think and want?London, England: Council for Industry and Higher Education.

Association of American Colleges and Universities. (2005).Liberal educa-tion outcomes: A preliminary report on student achievement in college. Washington, DC: Author.

Australian Council for Educational Research. (2002). Graduate skills assessment: Stage one validity study. Camberwell, Victoria, Australia: Department of Education, Science and Training.

Barringer, B. R., & Jones, F. F. (2004). Achieving rapid growth-revisting the managerial capacity problem. Journal of Development Entre-preneurship,9, 73–87.

Braun, M. (2004). Critical thinking in the business curriculum.Journal for Education for Business,79, 232–236.

Butchart, S., Bigelow, J., Oppy, G., Korb, K., & Gold, I. (2009). Improving critical thinking using web-based argument mapping exercises with automated feedback.Australasian Journal of Educational Technology,

25, 268–291.

Butler, H. A., Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J., Franco, A., Rivas, S. F., Saiz, C., & Almeida, L. S. (2012). The Halpern critical thinking assessment and real-world outcomes: Cross-national applications.Thinking Skills and Creativity,7, 112–121.

Chase, W. G., & Simon, H. A. (1973). Perception in chess.Cognitive Psy-chology,4, 55–81.

268 C. P. DWYER ET AL.

Chi, M. T. H., Glaser, R., & Rees, E. (1982). Expertise in problem solv-ing. In R. J. Sternberg (Ed.), Advances in instructional psychology

(pp. 7–75). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Chiesi, H. L., Spliich, G. J., & Voss, J. F. (1979). Acquisition of domain-related information in relation to high and low domain knowledge. Jour-nal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behaviour,18, 257–273.

Cheung, C., Rudowicz, E., Kwan, A. S. F., & Yue, X. D. (2002). Assessing university students’ general and specific critical thinking.College Stu-dent Journal,36, 504–522.

Deane, M., & Borg, E. (2011).Inside track: Critical thinking and analysis. Essex, England: Pearson.

Dobbs, M., & Hamilton, R. (2007). Small business growth: Recent evi-dence and new direction.International Journal of Entrepreneurship Behaviour Research,12, 296–322.

Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J., & Stewart, I. (2011). The promotion of critical thinking skills through argument mapping. In C. P. Horvath & J. M. Forte (Eds.),Critical thinking(pp. 97–112). New York, NY: Nova Science. Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J., & Stewart, I. (2012). An evaluation of

argu-ment mapping as a method of enhancing critical thinking performance in e-learning environments.Metacognition and Learning,7, 219–244. Dwyer, C. P., Hogan, M. J., & Stewart, I. (2014). An integrated critical

thinking framework for the 21stcentury.Thinking Skills and Creativity,

12, 43–52.

Elliott, M. A., & Dwyer, C. P. (2013). Assessment innovation research report: ProfIS assessment items validations study 1. Unpublished report. New York, NY: Assessment Innovation Inc.

Ennis, R. H. (1989). Critical thinking and subject specificity: Clarification and needed research.Educational Researcher,18, 4–10.

Facione, P. A. (1990).The California critical thinking skills test. Millbrae, CA: California Academic Press.

Glaser, R. (1984). Education and thinking: The role of knowledge. Ameri-can Psychologist,3, 93–104.

Goldberg, M. (1990). A quasi-experiment assessing the effectiveness of TV advertising directed to children.Journal of Marketing Research,27, 445–454.

Graham, S., & Donaldson, J. F. (1999). Adult student’s academic and intellectual development in college. Adult Education Quarterly, 49, 147–161.

Halpern, D. F. (2003)Thought and knowledge: An introduction to critical thinking(4th ed.). Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum.

Halpern, D. F. (2010).The Halpern critical thinking assessment: Manual.

Vienna, Austria: Schuhfried.

Hamm, R. M. (1988). Clinical intuition and clinical analysis: Expertise and the cognitive continuum. In J. Dowie & A. Elstein (Eds.),Professional judgment: A reader in clinical decision making(pp. 78–105). Cam-bridge, UK: Open University Press.

Hammond, K. R. (1996). Upon reflection.Thinking & Reasoning,2, 239– 248.

Heijltjes, A., van Gog, T., Leppink, J., & Paas, F. (2014). Improving criti-cal thinking: Effects of dispositions and instructions on economics students’ reasoning skills.Learning and Instruction,29, 31–42. Higgins, E. T. (1989). Knowledge accessibility and activation:

Subjectiv-ity and suffering from unconscious sources. Unintended Thought,

1989, 3–51.

Higher Education Quality Council. (1996).What are graduates? Clarify-ing the attributes of “graduateness.”London, England: Author. Hitchcock, D. (2004). The effectiveness of computer-assisted instruction in

critical thinking.Informal Logic,24, 183–218.

Hogan, M. J., Dwyer, C. P., Noone, C., Harney, O., & Conway, R. (2014). Metacognitive skill development and applied systems science: A frame-work of metacognitive skills, self-regulatory functions and real-world applications. In A. Pe~na-Ayala (Ed.),Metacognition: Fundaments, Appli-cations, and Trends, (vol. 4, pp. 75–106). Berlin, Germany: Springer. Holmes, J., & Clizbe, E. (1997). Facing the 21stcentury.Business

Educa-tion Forum,52, 33–35.

Jones, A. (2007). Multiplicities or manna from heaven? Critical thinking and the disciplinary context. Australian Journal of Education, 51, 84–103.

Kahneman, D. (2011).Thinking fast and slow. London, England: Penguin. Kahneman, D., & Frederick, S. (2002). Representativeness revisited:

Attribute substitution in intuitive judgment. In T. Gilovich, D. Grif-fin, & D. Kahneman (Eds.),Heuristics of intuitive judgment: Exten-sions and applications (pp. 267–294). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

King, P. M., & Kitchener, K. S. (1994).Developing reflective judgment: Understanding and promoting intellectual growth and critical thinking in adolescents and adults. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

King, P. M., Wood, P. K., & Mines, R. A. (1990). Critical thinking among college and graduate students.The Review of Higher Education,13, 167–186.

Ku, K. Y. L. (2009). Assessing students’ critical thinking performance: Urging for measurements using multi-response format.Thinking Skills and Creativity,4, 70–76.

Lehmann, D. R., & Nisbitt, R. E. (1990). Effects of teaching statistical laws on reasoning about everyday problems.Journal of Education Psychol-ogy,87, 33–46.

Lieberman, M. D. (2003). Reflexive and reflective judgment processes: A social cognitive neuroscience approach.Social Judgments: Implicit and Explicit Processes,5, 44–67.

Marin, L. M., & Halpern, D. F. (2011). Pedagogy for developing critical thinking in adolescents: Explicit instruction produces greatest gains.

Thinking Skills and Creativity,6, 1–13.

National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, Insti-tute of Medicine. (2005).Rising above the gathering storm: Energising and employing America for a brighter economic future. Washington, DC: Committee on Prospering in the Global Economy for the 21st Century.

Pascarella, E. T., & Terenzini, P. T. (1991).How college affects students: Findings and insights from twenty years of research. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

Reed, J. H., & Kromrey, J. D. (2001). Teaching critical thinking in a com-munity college history course: Empirical evidence from infusing Paul’s model.College Student Journal,35, 201–215.

Rimiene, V. (2002). Assessing and developing students’ critical thinking.

Psychology Learning and Teaching,2, 17–22.

Royalty, J. (1995). The generalizability ofcritical thinking: Paranormal beliefs versus statistical reasoning.Journal of Genetic Psychology,156, 477–488.

Smith, G. F. (2003). Beyond critical thinking and decision making: Teach-ing business students how to think.Journal of Management Education,

27, 24–51.

Stanovich, K. E., & West, R. F. (2000). Advancing the rationality debate.

Behavioral and Brain Sciences,23, 701–717.

Stewart, T. R., Heideman, K. F., Moninger, W. R., & Reagan-Cirincione, P. (1992). Effects of improved information on the components of skill in weather forecasting. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes,53, 107–134.

Tversky, A., & Kahneman, D. (1974). Judgment under uncertainty: Heuris-tics and biases.Science,185, 1124–1131.

Voss, J. F., Blais, J., Means, M. L., Greene, T. R., & Ahwesh, E. (1986). Infor-mal reasoning and subject matter knowledge in the solving of economics problems by naive and novice individuals.Cognition and Instruction,3, 269–302.

West, R. F., Toplak, M. E., & Stanovich, K. E. (2008). Heuristics and biases as measures of critical thinking: Associations with cognitive abil-ity and thinking dispositions.Journal of Educational Psychology,100, 930–941.

Whitten, D. (2011). Predictors of critical thinking skills of incoming business students.Academy of Educational Leadership Journal, 15, 1–13.