New perspectives on the

genetic classification of

Manda (Bantu N.11)

New perspectives on the genetic classification of

Manda (Bantu N.11)

Hazel Gray and Tim Roth

SIL Electronic Working Paper 2016-001

©2016 SIL International®

ISSN 1087-9250

Fair Use Policy

Documents published in the Electronic Working Paper series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructional purposes (under fair use guidelines) free of charge and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of an Electronic Working Paper or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s).

Managing Editor Eric Kindberg

Series Editor Lana Martens

Content/Copy Editor Mary Huttar

iv 1

Introduction and background

2

Dialectometry and lexicostatistical evidence

3

Phonological evidence

3.1

Dahl’s Law

3.2

Spirant weakening

3.3

*NC̥> NC or N

4

Sociohistorical evidence

5

Synthesis and conclusion

Appendix A: Lexicostatistics

1

Manda [ISO 639-3 code: mgs] is a Bantu language (N.11) spoken by the Manda and Matumba language communities located in the area between Lake Nyasa and the Livingstone Mountains (Maho 2009). The language area straddles two administrative regions in Tanzania: Njombe Region, north of the Ruhuhu River, and Ruvuma Region, south of the river. The area is bordered to the north by Kisi (G.67),1 to the

east by Pangwa (G.64) and Ngoni (N.12), and to the south by Matengo (N.13) and Mpoto (N.14) (Maho 2009). Lewis et al. (2015) report the Manda (and Matumba) population at 22,000. A previous SIL survey puts the estimate even higher, between 25,000 and 40,000 (Anderson et al. 2003a). This paper uses survey data from four other locations in addition to the Matumba variety in Luilo: Iwela, Lituhi, Litumba Kuhamba and Nsungu (see map below). We examine three streams of evidence (lexicostatistical,

phonological, and sociohistorical) in this study to determine the closest genetic relatives of Manda (and Matumba). New data is put forward from survey work conducted by SIL personnel in 2013 and

subsequent additional linguistic research (Gray, forthcoming; Gray and Mitterhoffer 2016).

1 The Guthrie codes for Bantu are referential, reflecting geography and not genetic relationship (see Schadeberg

The Matumba consider themselves a separate ethnic group from the Manda, but still regard their language to be essentially the same as Manda. The Matumba themselves claim that they were once Manda who moved from the shores of Lake Malawi up into the mountains (Anderson et al. 2003a). The prestige dialect (even according to the Matumba) of Manda is spoken in the area near Ilela and Nsungu, villages on the lakeshore (Gray and Mitterhoffer 2016). Various comparative linguistic studies have included Manda wordlists (Guthrie 1971, Nurse and Philippson 1975) and mention of Manda is made in diachronic studies by Nurse and Philippson (1980) and Nurse (1988, 1999). None of these studies mention the Matumba, so it is quite likely that the Matumba were unintentionally grouped with the Manda in previous studies. As we will see in section 3, this lack of previous dialect research has given rise to some misconceptions about the innovations that Manda shares with its neighbors.

Of those who have studied the Manda language with the aim of positing its closest genetic

affiliation, Nurse and Philippson (1980) and Nurse (1988, 1999) are in conflict with Ehret (1999, 2009). Ehret (2009:17) puts Manda alongside Ngoni in the Rufiji-Ruvuma (RR) subgroup, whereas Nurse classifies Manda within his Southern (Tanzania) Highlands (SH) subgroup. These are the main hypotheses we evaluate in light of the new data which reflects a better understanding of Manda dialectology. RR consists of two sub-branches. We are concerned primarily with Rufiji, which includes Manda’s immediate neighbors: Ngoni, Matengo, and Mpoto. The SH subgroup includes the G.60 languages, of which we are primarily concerned with Kisi and Pangwa for the same reason.

This paper mainly focuses on the arguments put forward by Nurse (1988), since he deals with the question of Manda’s genetic affiliation in the most depth. Ehret primarily relies on stem-morpheme innovations (lexical/semantic evidence) in his (1999) work, and does not offer the same depth of interaction with the corpus most like an SH language that Nurse does. From the Manda data Nurse uses, Manda appears to behave phonologically mostly like an SH language. However, we argue that the Manda data Nurse uses appears to be the Matumba dialect, which phonologically is quite different from the other Manda dialects. In section 3 we see how the features of Dahl’s Law, spirant weakening, and

NC̥>NC or N cast doubt on Nurse’s argument for Manda as SH. We offer three scenarios regarding the genetic history of Manda and Matumba in section 5.

In section 2 we present initial lexicostatistical evidence using dialectometry. Manda and Matumba varieties are compared to the other corpus languages: Kisi, Matengo, Mpoto, Ngoni, and Pangwa. Section 3 examines the phonological evidence for the corpus languages, while section 4 briefly examines the sociohistorical evidence. Section 5 concludes the paper with a synthesis, preliminary conclusions, and possibilities for future research.

2 Dialectometry and lexicostatistical evidence

Dialectometry is essentially quantitative dialectology. Distance-based networks are examples of such quantitative data explorations. A distance-based network analysis offers ‘‘an introductory visual means of data exploration’’ (Pelkey 2011:279). Subsumed under the rising field of dialectometry are several distance-based algorithmic applications that aim to help researchers explore language variation and/or change, while “making it possible to show more than one evolutionary pathway on a single graph” (Holden and Gray 2006:24). To create a distance-based network the opposite values of regular

lexicostatistical percentages are used within a standard matrix (e.g., the Kisi and Pangwa languages in figure 2 are 0.59 similar, but 0.41 dissimilar; see Appendix A). The resulting distance matrix is then subjected to the Neighbor-Net algorithm, as developed by Bryant and Moulton (2004) and implemented within the Splits Tree 4 (4.11.3) software program (see Huson and Bryant 2010). If the lexical

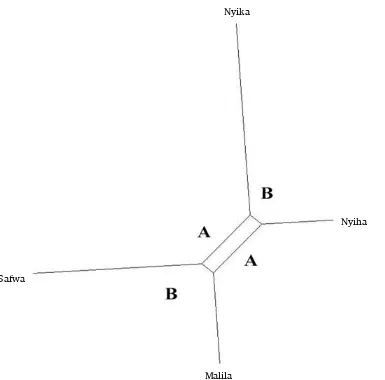

Figure 1. Sample network demonstrating ambiguity (adapted from Roth 2011:43).

In figure 1, the middle box indicates the ambiguous relationship: Split A—Nyika and Nyiha/ Safwa and Malila versus Split B—Nyika and Safwa/ Nyiha and Malila. In figure 1, Split A is more likely. Holden and Gray discuss other patterns and their meaning within the network diagram:

Rapid radiation may be inferred from a lack of phylogenetic signal, i.e. a rake- or star-shaped phylogeny, whereas reticulation would indicate possible borrowing. Reticulations can also pinpoint those languages which may have been involved in borrowing. Complex chains of conflicting relationships involving numerous languages may indicate that borrowing occurred in the context of dialect chains. (2006:24)

If the lexical relationships are more clear, the splits-graph looks more like a regular tree diagram (see Holden and Gray (2006) for further explanation of the Neighbor-Net algorithm, and the unique historical relationships between other Bantu languages).

Figure 2 below is based on the lexicostatistical data in Appendix A. The data includes lexical percentages from 313-item wordlists elicited in five locations (Iwela, Lituhi, Litumba Kuhamba, Luilo and Nsungu) during the 2013 dialect survey (Gray and Mitterhoffer 2016). This 313-item wordlist was based on the 100-item Leipzig-Jakarta wordlist (Tadmor 2009). Two hundred ninety-six of the lexical items2 in the 313-item wordlist were compared to data from SIL Fieldworks Language Explorer (FLEx)

2 Some lexical items were omitted due to duplications in the data.

Nyika

Nyiha

databases for Kisi and Pangwa, and CBOLD data for Mpoto, Matengo and Ngoni (supplemented by data from Ngonyani 2003 and Yoneda 2006) using the comparative method as the basis for determining cognacy. The lexical data (the 296-item wordlist) can be found in Appendix B. Consider the distance-based network below in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Distance-based network for SH, Rufiji and Manda corpus languages.

From the diagram in figure 2, we can clearly see the split between the branch containing the SH languages (Pangwa and Kisi) on the left and two of the Rufiji languages (Matengo and Mpoto) on the right. We can also see that the Manda dialects, while lexically related to SH and Rufiji, are at the same time lexically distinct, i.e., the Manda dialects seem to have a split-lexicon. Ngoni, while lexically more like Manda, is still split between Manda and the SH languages. (Ngoni is generally classified as RR, but its situation is similar to Manda’s, with the added complication of having an unclear relationship with the South African Nguni, see section 4).

In sum, the lexicostatistical evidence for Manda’s closest genetic affiliation is ambiguous as Manda has a split-lexicon. However, we can evaluate Nurse’s claim that Manda is “lexicostatistically a Rufiji

Pangwa Kisi

Matengo

Mpoto

Ngoni

Nsungu

Iwela

Lituhi

Manda

RR

Litumba Kuhamba

Luilo (Matumba)

language” (1988:70) and say that this more recent wordlist data does not corroborate that claim. Section 3 proceeds with evaluating the phonological evidence that ties Manda to either SH or Rufiji (or both).

3 Phonological evidence

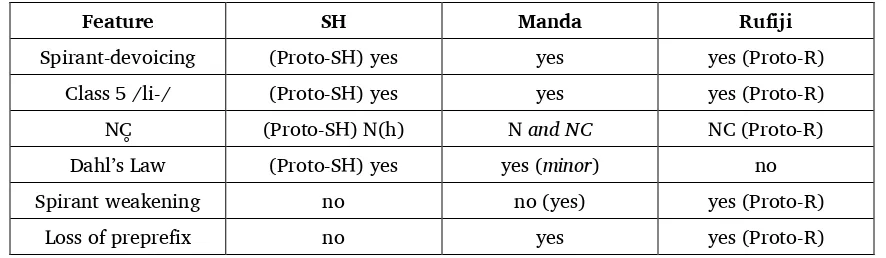

As we discuss in section 1, Nurse (1988) provides the most detailed argument regarding the genetic affiliation of Manda. Table 1 (adapted from Nurse 1988:47)3 is a comparison of what Nurse considers the

most relevant phonological features between SH, Rufiji, and Manda, in combination with conclusions from our newer data in italics.

Table 1. Comparison of Manda phonological features with SH and Rufiji (adapted from Nurse 1988:47)

Feature SH Manda Rufiji

Spirant-devoicing (Proto-SH) yes yes yes (Proto-R) Class 5 /li-/ (Proto-SH) yes yes yes (Proto-R)

NC̥ (Proto-SH) N(h) N and NC NC (Proto-R) Dahl’s Law (Proto-SH) yes yes (minor) no Spirant weakening no no (yes) yes (Proto-R)

Loss of preprefix no yes yes (Proto-R)

Nurse concludes that Manda is an SH language primarily based on the phonological evidence represented in this table. Nurse’s argument is as follows: (1) that SH and Rufiji differ in at least four categories (lines 3–6); (2) of those four categories, Manda matches SH in two cases, maybe three (line 5 is ambiguous); (3) thus, if Manda is SH, the only line which needs explanation is line 6 (the loss of the preprefix, or augment); whereas if Manda is Rufiji, lines 3–5 all need explanation. Nurse summarizes as follows:

It is therefore simplest to posit Manda, not as an original member of Rufiji, but rather as an original member of SH, which in recent times has undergone lexical change, and loss of preprefix, inherited vowel length (and possibly tones) under the influence of Rufiji, which presumably means Ngoni or Matengo (1988:48).

In this paper, we seek as much as possible to distinguish genetic inheritance from contact/areal diffusion, as well as shared innovations from shared retentions. For example, the class 5 *li- feature is a retention (compare Nurse 1988:30 and Nurse 1999:23), and a feature such as the loss of the preprefix (augment) is historically unclear and more likely to have been spread by contact (see Nurse 1988:47). Both are excluded from consideration here on this basis. Furthermore, the spirant-devoicing feature is shared by both subgroups (and most likely necessarily preceded spirant weakening), and so does not factor into the discussion (Nurse 1988:40, 43–44). That leaves Dahl’s Law, spirant weakening, and

NC̥>NC or N. Each of them are innovations, but they each also have their own unique considerations regarding the possibility of contact influence.

As we see in the remainder of this section, the Manda data Nurse uses appears to be the Matumba dialect. Even though Manda and Matumba are lexically similar (see section 2), Matumba is

phonologically quite different from the other Manda lects. This section provides the bulk of the evidence for Manda and Matumba as members of either SH or Rufiji. We examine Dahl’s Law, spirant weakening,

and NC̥>NC or N in sections 3.1, 3.2 and 3.3, respectively.

3 The table is duplicated with the exception of the feature “nasal and spirant”. This category is excluded from this

3.1 Dahl’s Law

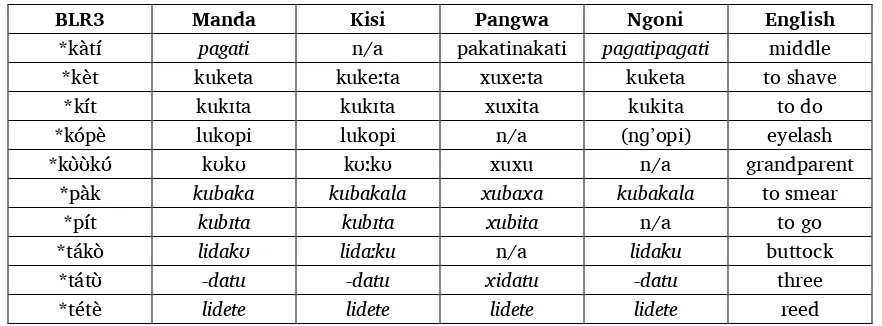

Dahl’s Law is a voicing dissimilation in many Bantu languages in which the first of two voiceless plosives becomes voiced, either within the root or across morpheme boundaries. Table 2 shows the examples of Dahl’s Law in several of the corpus languages. These are the only examples found in the Manda corpus. Nurse reports that there is no Dahl’s Law in Rufiji except for traces in Ngoni and Mbunga (P.15) (1988:103). The examples in italics are the lexical items showing Dahl’s Law. The BLR3 Proto-Bantu form is included in the table as well for comparison (Bastin et al. 2003). The lexical items not in italics are various stems where we might expect Dahl’s Law to operate but where no evidence of Dahl’s Law is found, despite both Proto-Bantu stem consonants being voiceless plosives.

Table 2. Dahl’s Law examples in the corpus languages

BLR3 Manda Kisi Pangwa Ngoni English

*kàtɪ́ pagati n/a pakatinakati paɡatipaɡati middle

*kèt kuketa kukeːta xuxeːta kuketa to shave *kɪ́t kukɪta kukɪta xuxita kukita to do *kópè lukopi lukopi n/a (nɡ’opi) eyelash *kʊ̀ʊ̀kʊ́ kʊkʊ kʊːkʊ xuxu n/a grandparent

*pàk kubaka kubakala xubaxa kubakala to smear *pít kubɪta kubɪta xubita n/a to go *tákò lidakʊ lidaːku n/a lidaku buttock

*tátʊ̀ -datu -datu xidatu -datu three

*tétè lidete lidete lidete lidete reed

The Manda dialects (including Matumba) share the same expression of Dahl’s Law: traces in the vast majority of the same lexical items and not across morpheme boundaries. Of the SH languages, only Hehe, Bena and Kinga have Dahl’s Law in all stems. Kisi and Pangwa show traces of it as does Manda/Matumba, while Sangu and Vwanji show no evidence of it at all. Based on this geographic distribution, it appears as though those languages with little or no trace of Dahl’s Law were on the outer edge of an earlier dialect continuum where Dahl’s Law was present. Regardless, Kisi, Pangwa,

Manda/Matumba and Ngoni all share the same traces of Dahl’s Law.

There are two main possibilities that might explain the pattern of Dahl’s Law traces in

Manda/Matumba: (1) genetic relationship with SH with (a) inconsistent application and/or (b) early phonological reversal (Nurse 1999:28), or (2) contact. Bantu languages can have inconsistent application of Dahl’s Law due to when the feature became inactive (Batibo 2000). A phonological feature becoming inactive can also be due to contact influences, as Batibo relates for the Sukuma/Nyamwezi languages (F.20) in western Tanzania:

The major reason for this inactivity, and therefore incompleteness, may have been the instability that both Sukuma and Nyamwezi experienced in their early years of resettlement due to the influx of intruding groups…The influx of the intruding groups meant the influx of new lexical items by speakers who did not have these rules in their language (2000:25).

3.2 Spirant weakening

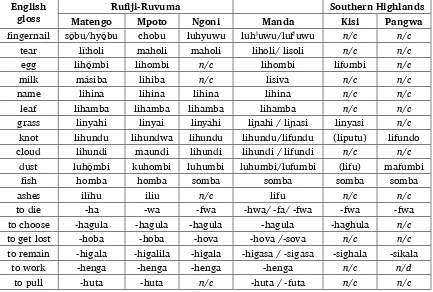

Spirant weakening, or lenition, is a process where spirants, such as /s/ and /f/, become weakened to /h/ or are lost entirely. Manda is again characterized by ambiguous data: a large number of lexical items still contain /s/ and /f/, though some have weakened to /h/. Table 3 shows all the relevant examples from the corpus of spirant versus /h/ forms in Matengo, Mpoto and Ngoni (RR), Kisi and Pangwa (SH), as well as Manda.

Table 3. Spirant vs /h/ in corpus languages

English gloss

Rufiji-Ruvuma Southern Highlands

Matengo Mpoto Ngoni Manda Kisi Pangwa fingernail sô̠bu/hyô̠bu chobu luhyuwu luhʲuwu/lufʲuwu n/c n/c

tear lîːholi maholi maholi liholi/ lisoli n/c n/c egg lihó̠mbi lihombi n/c lihombi lifʊmbi n/c milk másiba lihiba n/c lisiva n/c n/c name lihina lihina lihina lihina n/c n/c leaf lihamba lihamba lihamba lihamba n/c n/c grass linyahi linyai linyahi liɲahi / liɲasi linyasi n/c

knot lihundu lihundwa lihundu lihundu/lifundu (liputu) lifundo cloud lihundi maundi lihundi lihundi / lifundi n/c n/c

dust luhô̠mbi kuhombi luhumbi luhumbi/lufumbi (lifu) mafumbi fish homba homba somba somba somba somba

ashes ilîhu iliu n/c lifu n/c n/c

to die -ha -wa -fwa -hwa/ -fa/ -fwa -fwa -fwa to choose -hagula -hagula -hagula -hagula -haghula n/c to get lost -hoba -hoba -hova -hova /-sova n/c n/c to remain -higala -higalila -higala -higasa / -sigasa -sighala -sikala

to work -henga -henga -henga -henga n/c n/d to pull -huta -huta n/c -huta / -futa n/c n/c

Of the corpus languages, Matengo, Mpoto and Ngoni (all RR) generally use the weakened /h/ forms, while Kisi, Pangwa (SH) and the Manda lects of Iwela, Nsungu, and Luilo (Matumba) generally preserve /s, f/. The Lituhi and Litumba Kuhamba lects are in between, both geographically and in the type of forms they use. The Ruhuhu River separates these Manda dialects from the others.

sum, spirant weakening in the corpus languages remains inconclusive in terms of helping to determine the closest genetic affiliation for Manda.

3.3 *NC̥> NC or N

The phonological process whereby the historical sequence of a nasal followed by a voiceless homorganic plosive (*NC̥) has become either a nasal followed by a voiced plosive (NC) or a nasal by itself (N, in which the consonant has deleted altogether) is represented here as *NC̥> NC or N. Once again, the problem is that we need to try to distinguish inheritance/innovation from contact. Nurse explains the historical process as follows:

We assume here that inherited sequences of nasal plus voiceless homorganic stop have undergone one of two major processes: either the stop is voiced…or the sequence is maintained, which, however, can lead to devoicing of the nasal, which in turn can lead to N, Nʰ, C̥ʰ or C̥. Only the proto-languages for [RR] and Nyakyusa/Ndali show the stop voicing, whereas all the others show one or other form of the second process. (Nurse, 1988:31)

These processes constitute two very different pathways, and the issue is that we generally see

*NC̥>NC in Manda and *NC̥>N in Matumba. Kisi and Pangwa have N like Matumba, while Matengo and Mpoto have NC like the rest of Manda.

This is also an area where Nurse (1988) seems to use the Matumba dialect as normative for the entire language. In table 4, this is represented with the CBOLD label, which is the data that Nurse and Philippson collected. Table 4 shows all of the relevant reflexes of *NC̥ across Manda and Matumba from the corpus, and it also includes the CBOLD data and BLR3 references.

Table 4. Class 9/10 across Manda/Matumba dialects

PB stem *-kʊ́kʊ́ ‘chicken’ ŋguku ŋguku ŋguku ŋuku ŋguku ng’oko *-pépò ‘cold’ mbepʊ mepʊ/

mbepʊ mbepo mepu mbepu mepu

*-kópè ‘eyelash’ - - ŋgopi ŋopi ŋgopi (lukopi) *-kómb? ‘finger’ ŋgoɲɟi ŋoɲɟi/

ŋgoɲɟi (fiŋgoɲɟi) ŋgoɲɟi ŋgoɲɟi (lukonji)

n/c ‘goat’ mene mene mene mene mene mene n/c ‘lightning’ mbamba mamba mbamba mamba mbamba mamba *-ntù ‘person’ mundu mundu mundu munu mundu munu

We can clearly see from table 4 that the CBOLD data patterns most closely with the Luilo

(Matumba) dialect. To a certain extent there are examples of both N and NC in each dialect (often in the form of lexical doublets), but the overall pattern remains.

prenasalized consonant in the subsequent syllable, leaving behind either a simple or geminate nasal. Gray (forthcoming) describes in her Manda phonology sketch that it is not Ganda Law at work, but rather the post-nasal consonant is deleted across the board consistently for classes 1 and 3. There are many words where there is no NCVNC sequence, and yet C1 is deleted (for class 1 and 3), such as * n-dala/nala, and *n-gosi/ŋosi, etc. There are also lots of NCVN(C) sequences that do not become NVNC:

ndemba (hen), ngondo (quarrel/war), mbanda (slave), ndongo (relative), ndomondo (hippo).

The *NC̥> NC or N evidence in this section is not the silver bullet of clarity to Manda’s genetic relationship to either SH or RR. However, this new research into the *NC̥ process does pose a serious difficulty in any argument for Manda as a SH language. Possible rejoinders to the argument that Manda

is not SH on the basis of *NC̥ reflexes are that (1) perhaps Manda and Matumba should not be

considered a single historical language variety, in which case Matumba could certainly be SH, or (2) perhaps Manda/Matumba is SH and all the Manda dialects except for Matumba were in contact with RR. We explore these possibilities in our synthesis and conclusion in section 5, after we examine the

sociohistorical evidence in section 4.

4 Sociohistorical evidence

While oral traditions do not necessarily prove historical origin, it is worth taking into account what the Manda and Matumba say about their own historical origins. Data gleaned from group questionnaires taken during the 2013 SIL dialect survey of the Manda/Matumba area reveal that the Manda and Matumba have mixed views of their origins. Several groups claim the Manda are partly descended from the Nguni tribe of South Africa; others claim that they were from Malawi or from the Songea region.4

Some claim they are partly descended from the Pangwa and partly from the Matengo language communities. We will briefly comment on these claims.

Ngonyani (2003:1), in his explanation of the origins of the Tanzanian Ngoni people, states that the Ngoni people incorporated many indigenous inhabitants of the area from different language groups when they moved into the highlands east of Lake Nyasa. Ngonyani includes Manda in the list of language communities that the Ngoni incorporated. This statement implies there was at least a group called Manda living there at the time the Ngoni invaded, which seems to run counter to claims that the Manda are descended from the Ngoni. Linguistically, Nurse (1999:13) claims that the Ngoni themselves

abandoned the Nguni language in favour of the local languages in the nineteenth century when they invaded from the south. Nurse (1988) also made this claim based on the absence of connection between Tanzanian Ngoni and South African Nguni languages. It would seem that the invasion left few linguistic traces from Nguni (Nurse 1988:48), and that the language of the invaders themselves, now known as Tanzanian Ngoni, was more affected by the invasion than the neighboring groups were. However, according to the original SIL sociolinguistic survey (Anderson et al. 2003a), the Manda/Matumba themselves claim to understand Ngoni very well. This holds true even for those villages furthest from the Ngoni language area, with some saying that even children can understand Ngoni.

In regard to the claims about the historical relationship to Pangwa, Anderson et al. (2003a:9) state that “historically, people of various ethnic groups (mostly Pangwa) migrated from various areas into the region along the coast (of the lake)”. According to this history, the Manda would be most related to the Pangwa; however, the people’s own perception of the relationship between the languages contradicts these origins. The Pangwa survey report (Anderson et al. 2003b) confirms that currently at least, the Manda and Pangwa people groups have little contact, and that the Pangwa understand very little of the Manda language. The Manda/Matumba themselves claim that there is “no language relationship

whatsoever between Manda and Pangwa” (Anderson et al. 2003a:8), even for those villages closest to the Pangwa language area. The intelligibility of Kisi seems more disputed; some villages claimed that there was little resemblance, but some (Matumba villages) claimed to understand Kisi relatively well. All groups that were interviewed during the survey claimed that the lexicon is similar and the difference lies

in pronunciation. Interestingly, the Manda village called Iwela, which has had more contact with Kisi than most of the rest of the Manda area, is considered by some other Manda (Matumba) villages as a place where the people are not ethnically Manda and do not speak the Manda language. The people of Iwela themselves claim to be Manda, but many features of their dialect show the influence of the Kisi language on it. Nurse (1988:70) claims that Kisi has been heavily affected by the N.10 languages, which may be a factor influencing the higher intelligibility with Kisi than with Pangwa.

Regarding the possible connection with Matengo, the findings in the 2013 dialect survey were that for those villages south of the Ruhuhu River in the Ruvuma region there is considered to be little intelligibility between Mpoto and Manda and even less between Matengo and Manda.

In summary, the sociohistory of the Manda language community is still unclear. General feeling among the Manda/Matumba would connect them most closely to the Ngoni. However, Ngoni appears to have had merely a superstratum influence on Manda and other language communities in the area, and so this would not be an indicator of close genetic affiliation. For Pangwa, one would expect the

comprehension with Manda to be higher if the Manda had indeed descended from Pangwa as reported; however, comprehension is quite low as the Livingstone Mountains create a barrier between the Manda and the Pangwa language areas. As an added note, the accessibility of the Kisi area by canoe gives the Manda/Matumba more opportunity for contact with Kisi.

We now turn to synthesizing the lexical, phonological, and sociohistorical evidence, and developing some conclusions, specifically in interaction with the results regarding Manda’s historical relationships from Nurse (1988). We will also briefly explore ideas for further research.

5 Synthesis and conclusion

So far, this paper has considered three main streams of evidence (lexicostatistical, phonological, and sociohistorical) in working towards determining whether Manda is most closely genetically affiliated with SH or RR. In isolation, all of the streams have been ambiguous and so far inconclusive. In this section, we seek to synthesize these streams of evidence and arrive at some tentative conclusions.

In section 3.3 we encountered evidence that led to the possibility that we should consider Manda and Matumba historically separate languages. The *NC̥> NC or N feature was found to be the significant

phonological difference between the Matumba/Luilo dialect (*NC̥>N) and the remaining Manda dialects (*NC̥>NC). In this view, Manda could be historically RR while Matumba could be SH, solving the most pressing difficulty. There are at least two arguments for the historical unity of Manda and Matumba as dialects of one language: (1) the lexicostatistics bear this out (see section 2 and Appendix A), and (2) the testimony of Manda and Matumba native speakers themselves.

Frankly, however, this is not enough evidence to eliminate the option that Manda and Matumba were historically separate languages that originally came from different genetic subgroups. If this were indeed the case, it would not change the fact that Matumba can certainly be considered a modern-day dialect of Manda. In regard to (1), as important as lexicostatistics can be, they “can only describe and extend relatedness but cannot establish it” (Nichols 1996:64). The same can be said of native speaker testimony (see Hinnebusch 1999:179). The gold standard of evidence for genetic relatedness is shared innovations, specifically what Nichols (1996) calls ‘individual-identifying’ evidence. The only such evidence that could be considered ‘individual-identifying’ in this paper is the *NC̥ feature, which happens to cut across Manda and Matumba. Part of the reason for the lack of shared innovations could be rooted in the history of these Bantu subgroups. Nurse says of SH that there is “a relative lack of really distinctive innovations. None of the innovations preceding […] is unique, all being shared with some combination of surrounding groups, which raises the possibility that the innovations might be the result of areal spread, or that the Proto-SH period was short, not allowing time for innovation” (1988:40). Rufiji is in a similar situation (see Nurse 1999:31).

Normally with such a lack of shared innovations, we could rely even more on paradigmatic

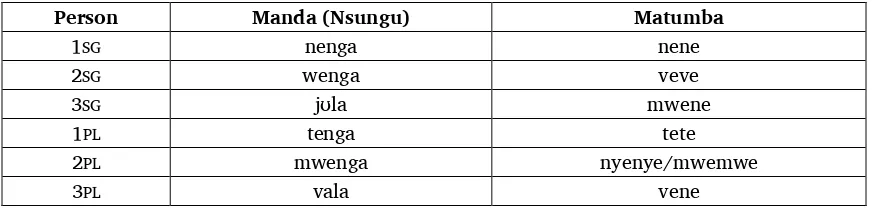

Manda. But again, the evidence remains ambiguous and inconclusive. We can see this in the clear differences between the personal pronoun set(s) in Manda and Matumba in table 5.

Table 5. Personal pronouns in Manda and Matumba (Gray 2016:148)

Person Manda (Nsungu) Matumba

1SG nenga nene

2SG wenga veve

3SG jʊla mwene

1PL tenga tete

2PL mwenga nyenye/mwemwe

3PL vala vene

Obviously, this is just one example of a paradigmatic grammatical set in which Manda and Matumba are in disagreement. More research is needed on the grammar of the Matumba dialect in particular. What we do know is that Manda and Matumba indeed share much in common phonologically and grammatically. That Matumba is a modern-day dialect of Manda is not in dispute. The issue is that we still cannot dismiss the possibility that historically Manda and Matumba did not come from the same recent ancestor—that Manda belonged to the Proto-Rufiji subgroup, while Matumba was a member of Proto-SH. This would entail that Matumba underwent massive relexification, to the point where today the lexicostatistics are indistinguishable. Matumba must have also adopted many grammatical elements from Manda. Under a long period of extreme contact, none of this is out of the question in a

geographical area where SH and Rufiji collide. What of the other possibilities?

If we set aside the option that Manda and Matumba come from different subgroups historically, we are left with Manda/Matumba as either SH or Rufiji. We saw in section 2 that Manda/Matumba

essentially has a split-lexicon between SH and Rufiji, which does not support one subgroup over another. The argument for Manda/Matumba as SH centers around the traces of Dahl’s Law. Under this scenario,

spirant weakening is adequately explained due to contact with Rufiji languages to the south. The *NC̥

feature is harder to explain, but not impossible. Its distribution too would have to be the result of

contact: *NC̥>N in Matumba represents the original SH feature, while *NC̥>NC in the rest of Manda would be due to contact with Rufiji. The question under this scenario: Why didn’t Matumba adopt NC like

the rest of Manda? It would have to have been in contact with Rufiji languages (or the other Manda

dialects with NC) to explain the spirant weakening pattern.

The argument for Manda/Matumba as Rufiji centers around the majority of Manda dialects showing *NC̥>NC and the spirant weakening pattern representing inconsistent application of the innovation. Dahl’s Law traces are explained by the borrowing of individual lexical items from SH. Given the small amount of the Manda lexicon that has been affected by Dahl’s Law and those traces being in common with the neighboring SH languages, contact influence is reasonable despite Dahl’s Law normally being diagnostic in other branches of Bantu. *NC̥>N in Matumba is due to contact with SH. In this scenario, this borrowing (or reversal) only happens in one dialect instead of several. Dahl’s Law lexical items would have diffused much earlier. Nurse also mentions for Rufiji, “an apparently unique set of

allomorphs for the /-ile/ suffix” (1988:45). Manda appears to have these allomorphs (Gray 2016:108), but although their geographical distribution has been clarified (e.g. Nurse 2008:267), it is still unclear whether these /-ile/ allomorphs truly would distinguish Rufiji from SH, but needs to be explored further.

In this paper we have explored lexicostatistical, phonological, and sociohistorical evidence in the goal of determining the closest genetic affiliation for Manda (SH or RR). Much of the evidence was ambiguous and inconclusive, but in this section we were able to put together three viable scenarios. Two of those scenarios we found much more likely than the remaining option, and both refine our

understanding of Manda’s history and dialectology. We primarily interacted with Nurse (1988) who had given the most in-depth previous account. Most crucially, it appears that the dialect used by Nurse for Manda is actually Matumba, which is phonologically different from the Manda dialects, especially in

14 Lituhi

75 Litumba Kuhamba

77 67 Nsungu

73 76 71 Luilo

75 73 77 78 Iwela

53 54 53 58 58 Kisi

43 44 45 50 48 59 Pangwa

65 65 60 67 63 52 45 Ngoni

47 44 48 43 48 37 26 43 Matengo

15

The wordlist data transcriptions are replicated from the original source databases (see §2), except for the Manda and Matumba varieties which are in IPA. Tone is generally not included due both to the nature of the source databases and the rapid survey word-collection conducted by SIL.

English

Gloss Lituhi Litumba Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

1 eye líhu - míhu liho - mihu lihu - mihu lihu - mihu lihu - mihu liːhu liho lihu lîhu - mîhu liu

2 eyelid fíkupalɪlɪ - kíkʊpalɪlɪ fikupulila - kikupulila ŋgopi ŋopi ŋgopi lukopi ng'ope cha mumiho ng'opi ingopi ingopi

3 ear líkutu - mákutu líkutu - makutu likutu -makutu likutu -makutu likutu -makutu mbʊlʊkʊtʊ mbulukhutu likutu; ɲɟɛvɛ likûtu -makûtu likutu

4 mouth ndomo - milomo ndomo - milomo ndomo -milomo milomondomo - ndomo -milomo ndomo mlomo m̩lɔmɔ ndomo -mílomo (lip) kukano

5 *jaw ɲɟeɟe ɲɟeɟe ɲɟege litama -matama tili taʝa lucheeche njeje lugômu –ingômu lugomo

6 nose mbúnu - mbunu mbunu / meŋelu mbunu mbunu mbunu mheŋelu meng'elo mɛŋɛlu ímbulu -ímbulu imbulu

7 *chin kiɲɟwemba - fiɲɟwemba kiɲɟwemba -fiɲɟwemba kiɲɟwemba -fiɲɟwemba kiɲɟwemba -fiɲɟwemba kiɲɟwemba -fiɲɟwemba kidefu khilefu ciɲɟwɛmba kíleu - íleu kileu - ileu

8 beard liɲɟwémba - maɟwémba liɲɟwemba -maɲɟwemba liɲɟwemba -maɲɟwemba maɲɟwemba ndefu ndefu mlefu maɲɟwɛmba lúnde(b)u -índe(b)u indeo

9 tooth línu - mínu linu - minu linʊ - minʊ linu - minu linu - minu liːnu lino linu lîno - mîno lino

10 tongue lulimi lulími lulimi lulimi lulimi lulimi lulimi lulimi lúlimi - ínimi lulimi

11 head mútu - mítu mútu - mítu mutu - mitu mʊtu - mitu mutu - mitu mutu mutwe mutu umûtu -mimûtu mmutu

12 hair (of head) lijúɲɟu - majúɲɟu lijuɲɟu - majuɲɟu ljuɲɟu -majuɲɟu lijuɲɟu lijuɲɟu -majuɲɟu ɲɟwili njwili ɲɟwili líjunzu -májunzu lijunju

13 neck siŋgu siŋgʊ siŋgʊ siŋgʊ siŋgʊ siŋgu singo siŋgu hîngu-hîngu hingo

14 stomach liléme - maléme liléme - maléme lileme -maleme lileme malemelileme - lileme -maleme lileme -maleme lileme -maleme lutumbo lutumbu

English

24 armpit ŋgwápa ŋgwapa ŋgwapa ŋgwapa ŋgwapa ŋ'hwapa mkhwapa ngwapanilu ngwâpa - ngwâpa ingwapa

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

33 wing lipapanílu - mapapanílu lipapanílmapapanílu ʊ - lipapanílu - mapapanílu lipapanilu - mapapanilu lipapanilu - mapapanilu kibabatilu lipapatilo ligwaba; lipapanilu kípapatila

English

54 god tʃapáŋga Muŋgu muluŋgu / kjuta muŋgu muluŋgu muŋgu linguluvi cimluŋgu ń̩do̠ngu tʃapaŋga

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

64 *fruit-bat liniminími - maniminími liniminimi - maniminimi liniminimi - maniminimi liniminimi - maniminimi

lindʊlindʊli-

makambaku likambaku likida likambaku

ng’ombi

lipôngu ŋombi

70 calf litóli - matóli litoli - matoli litoli - matoli litoli - matoli litoli - matoli ŋombi ndala khikwada litoli litoli litoli

71 chicken ŋgʊ́ku ŋguku -

maŋguku ŋguku ŋuku ŋguku ŋhʊkʊ ng'uukhu ŋguku íngo̠ku ingoko

English

mabasi libasi libanji libasi lijobateki lijola

81 leaf lihámba -

matafi litaːfi litaafya ndafi limbándi limbandi

83 shade kihwíli -

migunda ŋgʊnda lihala mgunda ńgo̠nda ngonda

English

mafundu liputu lifundo lihundu lihundu lihundwa

98 chair kiti kiti tʃa uʋiʋu kitiɪhu -

fihetulu humbulu zawadi mbonolo injombe kíhupo - íhupo

106 cooking pot kiʋɪga kifiʋega -

gubundwiki kuhoŋgola sitema

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

115 spear ŋoha - migoha ŋoha migoha - ŋoha migoha - migoha ŋoha - ŋoha migoha - ŋgoha mkoha mgɔha n̩kôa nkoa

116 arrow pɪndi mʃale -

miʃale lupindu

kipindi -

fipindi mshale mcɔyɔ; nduta n̩sâli - lihônga mpendi

117 hole lilindi - malindi

lilɪndi - malɪndi

lilɪndɪ - malɪndɪ

lilɪndi - malɪndi

lilindi -

malindi lilɪndɪ mlindi lilindi libó̠mba -

lihóto libomba

118 enemy duʋi - maduʋi dumaduʋi - ʋi

ndʊwʊ - ʋaluwu

duʋi - maduʋi

duʋi -

maduʋi duːβi litavangu

119 arguments ŋani ŋani lukani ŋani ŋgani nhaːni ng'aani

120 fire mwoto - mjoto mwoto - mjoto lilambi - malambi moto mwoto mwoto mwoto mwɔtɔ; mbasu mwôto motu

121 firewood mbawu luʋawu - mbawu lubawu - mbawu mbawu mbahu luʋahu - luβaβu luhakala sagala lúhanzu - nhânzu hanju

122 smoke ljohi ljosi -

maljosi ljosi ljosi ljosi ljosi lyosi lyɔhi lihyôi lihyoi

123 ashes ljeŋge -

maljeŋge ljeŋge maljeŋge- lifu lifu lifu - malifu ljeŋge lyenge lyɛŋgɛ / lihu ilîhu iliu

124 night kilu kilu kilu kilu kilu pakilu pakhilo kilu ikîlu ikilu

125 darkness lwisi lwisi lwisi lwisi lwisi ŋgiːsi khutiitu citita lwiê lubendu

126 month mwese - mjese mwesi - mjesi mwese mwese mwesi mwesi mwechi

127 star lundóndo - ndondo ndondʊ ndondo ndondo ndondo lutondo lutondwi lundɔndɔ; ɲɔta lútǒndo -

lúndǒndo ndondwa

128 sun ljʊʋa ljoʋa / lijoʋa liɟuʋa liɟuʋa liɟuʋa liɟʊβa lichuva / livala lyuva; lilaŋga lyô̠ba lyoba

129 daytime musi musi musi musi musi pamusi pamunyi necho muhi mûhi lyoba

130 today lelu lelʊ lɪlɪnu lelu lelu leːlu ileelo lɛlɔ lê̠lê̠nu leleno

131 *yester day golo golo ɠoɾo golo golo ɣolo ikolo gɔlɔ lǐso liso - licho

132 *tomor-row kilawu kilau kilawu kilau kilahu kilaβu khilaavo cilawu kilâbu kilabo

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

134 *cloud mahundi mahundi mafundi mahundi mafundi liβɪŋgu lifulukha lihundi; liwiŋgu líhundi maundi

135 wind mpʊŋgʊ mpuŋgu mpuŋgu mpʊŋgʊ mpuŋgu mpʊŋgʊ

fidunda kidʊnda ikhidunda citumbi kitômbi kitombi

142 stone ligáŋga -

madupi kikama umufuumbi madakali úto̠pi

matogopi; mandakali

144 *sand nsaŋga -

masaŋga nsáŋga masáŋga- msaŋga nmasaŋgasaŋga - nsaŋga nsaŋga mhanga masavati hǒko - lúhanga luhanga

145 *dust luhumbi luhúmbi - maluhúmbi lufumbi lufumbi lufumbi liːfu mafumbi

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

152 they ʋene ʋene ʋala ʋala ʋala βeːne aveene vɛnɛ bômbi - bóbi b'ombe

153 four ntʃétʃe ntʃetʃe ntʃetʃe ntʃetʃe ntʃetʃe fina chitayi / mtanda -cɛcɛ ń̩sesi nsesi

154 five muhanu muhanu muhanu muhanu muhanu fihanu chihanu -mhanu ń̩hanu nhwano

155 hot lupjʊwʊ ljoʋa likali lifuki kupjupa / dʒoto lifuki

156 cold mbepʊ mepʊ mbepo mepu mbepu mhepu -va ng'ala mɛpu +hîmo kipepo

157 long kitali kitaːli kitali kitali kitali tali taali -tali +lasu-nasu +lasu-nasu

158 short kihupi kihupi kifupi kifupi kifupi fupi fupi fupi +jǐpi -jipi

159 big kiʋaha kiʋaha kiʋaha /

kikʊlʊŋgʊ kiʋaha kiʋaha baha vaha -vaha +ko̠lô̠ngu -kolongwa

160 small kitʃoko kitkidebe ʃoko / kitʃoko kidebe kidebe debe deebe -dɛbɛ +sóku -soko

161 *heavy kitopa kindu kitopa kitopa kitʊpa kindu kitopa bhusitu chito -tɔpa -topa - +tópeu -topa

162 *light kijʊjʊfʊ kindu kitopa he kijujufu kijojʊfu kindu kijujufu ʝʊʝʊfu vevelele -jó̠jo̠hu -pepwa

163 difficult kinonono mtihani gugumu kinonono gunantahu mtihani gugumu nonono linonono

164 good tʃa bwina tʃa bwina kinofu kinoho kindʊ kinofu nofu nofu abwina +nyahi -nyai

165 bad kinofu lepa kindu tbwina he ʃa kiʋifu kinoho lepe kindʊ kibaja bhibhi viivi baya +nákau -ambone

166 *bitter giʋaʋa litunda liʋaʋa gaʋaʋa giʋaʋa giʋaʋa kulʊla -vava -baba -bhabha

167 *sweet giɲoŋoɲa matunda gi

ɲoŋoɲa ganoga ginoga ginoga kunogha noka -nɔga -noga -nogha

168 *left (hand) maŋgɪjɪ pandigwa ku

ʃoto maŋgeɣe maŋgɪgɪ maŋgɪgɪ - khikanja kumaŋgigi

kúboku

kumánangeja kumaŋgeja

169 *right

(hand) malɪlu

pandigwa

kulia malelu malɪlu malilu - khikanja kumalyɛlɔ

kúboku

kwanámalelelu kumalelo

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

171 behind kuŋoŋgo kuhjetu kuŋoŋgo kuŋoŋgo kuŋoŋgo kuɲuma kumkongo khwa kunyuma kumbele kumbele

172 in front of kulóŋgolo kuloŋgolo kuloŋgolo kuloŋgolo kuloŋgolo βuloŋgolo khuvolongolo kuloŋgolo kulooŋge kulongi

173 near papipi papipi papipi papipi papipi papiːpi papiipi papipi pámbipi pambipi

174 new tʃa mpja kindu kja mpja kiɲipa kiɲipa kiɲipa pya pya mpya +nyâhi -henu

175 all fjoha findu fjoha fjoha fjoha foha oha ooha -ɔha +ôha -oa

176 many fjamahele findu fimehele fjamahele fimehele fimehele -ŋgɪ +olofu máhɛlɛ +íngi ingi

177 red kikele kindu kiduŋu kikele kiduŋu kiduŋu / kikele dung'hu duung'u -duŋg'u +kêli

178 black kipili kipili / kititu kipiːli kititu kipili /

kititu titu tiitu -titu +jilu mbili

179 white kiʋalafu kindu

kiʋalafu kiʋalafu kiʋalafu kiʋalafu bhalafu valafu amsɔpi

+hûhu -

+hûo nhuo

180 who? jani jani weŋga wanani jani jani niaːni yuyaani jani nyane; nya? ɲa?

181 what? kjani kjani / kiki kjani kiki kiki kiki khikhi kjani kiki kwa

182 *dirty ŋgʊwʊɟitʃafu ŋgʊwʊ itʃafu ŋgowo itʃafu ɟitʃafu ɟitʃafu chafu -lama -hakala; cafu +bepa usapu

183 to be rotten liwolili litunda libovu liwolili liwolili liboʋu kuβola -vola -wɔla jibolike kiboo

184 dry kijʊmʊ kitambala kj

ʊmo kijʊmʊ kjumu kijumili -ʝʊmʊ umu -yumu +jǒ̠mu -jomu

185 wet kivɪsɪ kitambala k

ɪʋɪsɪ kiʋisi kiʋesi kiʋisi - -

186 *to be full imemili tʃupa imemili iméˈmiˑli imemɪli imemili kumema -mema -mɛma -twele -twelela

187 to sit down kutama kutama kuˈtama kutama kutama kutaːma -taama -tama -tama -tama

188 to stand kujima kujɪma kuˈjɪma kujɪma kujɪma kuʝɪma -ima -yima -jema -jema

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

190 to rise up kujumuka kujumuka kujúˈmuka kujumuka kujumuka - -

191 *to ask for kulʊʋa kusʊka kuˈsuka kusuka kusuka kusʊːma -nyilikha -yupa -looba -jopa

192 to bring kuleta kuleta kuˈleˑta kuleta letaji kuheŋgelesja -leeta -lɛta -leta -leta

193 to get, receive kupáta kupata nipáˈtili (kupata) kupata nikaʋili kukaβa -pata -pata -pata

194 to take kutola kutola kuˈtoˑla kutola kutola kutoːla -toola -tɔla -tola -tola

195 to carry kupɪnda kupɪnda kuˈpɪkubapa nda / kupɪnda kupɪnda kupɪnda -pinda -tola -jukua -tola

196 to hold kukamúla kukamula kukáˈmʊla kukamula kukamula kukamula -khamula -kamula -kamula -kamula

197 to sell kuhemelesa kuhemelesa kuhemelésa kuhemelésa kuhemelesa kuɣʊsja -kucha -gulisa -hemelesa -hemelesa

198 to buy kuhemela kuhemela kuhéˈmela kugula kuhemela kuɣʊla -kula -gula -hemela - -lomba -hemela

199 to give kumpela kumpela kuʋaˈpeˑla kupela anipelili kupeːla -peela -pɛla -pekeka -peke

200 to send kutuma kuntuma kulaˈgɪsa kutuma kutuma kukosja / kula

ɣisja -seeng'a -tuma -tuma -tuma

201 to bite kuluma kupiʋina /

ʋina kuˈluma / kuʋɪna kuʋina kuluma kuluma

-luma / -vava

ilino -luma -luma -luma

202 to eat kulja kulja kulja kula kulja kulja -lya -lya -lya -lya

203 to drink kuɲwa kuɲwa kuˈhopa kuhopa ɲwai kuɲwa -hopa -ɲwa -ɲwa -ɲa

204 to boil water kupjʊsa kuheʋa kuteˈleka mat

ʃi kutʃemʃa kuteleka kuheβa -tipula; -lokota -heva -semsa - -tutua -tutua 205 to pour kupʊŋgʊla kujakana kuˈsopa kupʊŋgula kuhumasa kugidisja -sopelela / -dudilila -yita -jegela -poŋgola

206 to vomit kudeka kudeka kuˈɗeka kudeka kudeka kudeːka -deekha -dɛka -tapika -tapika

207 *cough kugohomola kugʊhomola kukosóˈmola kugohomola kukosomola kukosomola -kohomola -kɔsɔmɔla -komola -komola

208 *to sneeze kutjesamula kutʃesamúla kutjésáˈmula kutjesemúla kutjɪsamula kutesemula -tyasamula -tɛsɛmula -sipula -simuka (chafya)

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

210 to suckle kujoŋga kuɲoŋga kuˈjoŋga kuɲoŋga kujoŋga kuʝoːŋga -yong'a -ɲoŋga; -ɲoŋa -joŋga -joŋga

211 to spit kuhuɲa kufuɲa kuˈfuɲmata a kufuɲa mata kufuɲa mata kubeha -beha -huɲa -huna -huna

212 *to blow (wind) kututa kututa upiti mpʊŋgʊ kupuɾa

mpuŋgu kupula - -puka -vuma -po̠ga n̩hwâi -pula

213 to shave kumoɣa kuketa kuˈmoɣa kuketa kukasa kukeːta /

kukasa -timba -keta -moga -moga

214 to whistle kupjʊla kupjola kuˈkʊʋluk a ʊfi

kukuʋa

kufjuɾu kufjula

kukʊːβa lukʊfi

-tova u

mwiluchi lukwilu lulʊhi -jemba luloi

215 to yawn mwajulu kujahamúla kujáˈjʊla kujajula mwajulu kujajʊla kuʝaʝula -ayula; -ayamula -yahamula -jama -jama

216 to sing kujɪmba kujimba kuˈjimba kujimba kujimba kuʝɪmba -yimba -yimba -jemba -jemba

217 to play kukina kukina kuˈkina kukina kukina kukina -khina -kina -kina

218 to dance kuhina kukina ŋoma kuˈhina

ˈŋóma kukina ŋoma kuhina ŋoma kukina liŋoma -khina -hina -hina -hina

219 *to swim kusʊgalila kujogeléla kusʊgaˈlɪla kujogalela kusʊga kusʊːɣa -suuka sambalila -sambila

220 to laugh kuheka kuheka kuˈheka kuheka kuheka kuheka -hekha -hɛka -heka -heka

221 to cry kulila kulɪla kuˈlɪla kulila kulɪla kulɪla -vemba -vɛmba -ng’atalila -lela

222 to lie kudeta kuɟoʋa uɗese kudeta majeja (ndese) kudeta kuudese ɟoʋa - -

223 to speak kuɟoʋa kuɟoʋa kuˈɟoʋa kuɟoʋa kuɟoʋa /

kuloŋgela - -chova -ɟɔva; -luwula -pwaga -pwaga - kukolob'eka 224 to ask kukota kukota kuˈkota

liˈloʋi kukota kukota kukota -levucha -kɔta

la:lua,

-lalukila

225 to answer kuhɪga jibwaji kuˈhɪga kunihiga lepa ɟibwaji kuhmaswali ɪɣa -hika -yidika -koga, kogela

226 to look at kulola kulola kuˈlola kulola kulolakesa -laːŋga -lola -lɔla -lola - -linga -linga

227 *to show kulasa /

kulaŋgisa kulasa kuˈlaˑsa kulasa kulasa kulaːsja -laasa -langia

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

229 to die kuhwa kufa ˈkufwa kufa / afwili kufwa kufwa -fwa -fwa -kuha - -ha kuwa

230 to know kumaɲa kumaɲa kuˈmaɲa kumaɲa kumaɲa kumaɲa -manya -maɲa -manya -manya

231 to be known kumanikana kumaɲikana kumaɲá

ˈkana kumaɲakana kumaɲakana

232 to choose kuhagula kuhagula kuhagʊla kuhagula kuhagula kuhaːɣkuhala ula / -hala -hagula -hagula -haɣula

233 *to help kutaŋgatila kutaŋgátila kutaŋgaˈtɪːla kusaidila kutaŋgatila kutaŋgatila -tanga -taŋgatila -jangatila

234 to walk kugenda kugenda kugeːnda kugenda kugenda kuɣenda -kenda -gɛnda -lega -jenda

235 to run

away kukɪmbɪla kukimbila kukɪ́ˈmbɪˑla kukɪ́mbila kukimbila kuhema -hema -ɟumba / -tila -butuka - -tila -butuka

236 to pull kuhuta kuhuta / kufuta kuˈfuta kuhuta kufuta kukwaβa -khweka -kwɛga / -huta -huta - -hutalila -huta

237 to come kuhika / hikaji kuhika / hikaji hiˈdáji kuhida (hidaji) kuhida (hidaji) kuʝisa -icha -hika -hika -hika

238 to leave kuwʊka kuluta kuˈwʊka kuwuka kuʋʊka kuleka -heka -lɛka -leka -boka

239 to fall kugwa kugwa ˈkuˑgwa kugwa kugwa kuselela -dima -gwa -habuka -hag'uka

240

*to turn (to

revolve) kuŋanaˈmbʊ

ka kuŋanamúka kuŋaná

ˈmʊka kuŋanamʊ́ka ˈkuŋanamʊ́ka kusjʊŋgʊsja -nienga -tindila -hyo̠ngale̠ka

-ng'anam buka

241 *to burn up kuˈɲaɲa kuɲaɲa kuˈɲaɲa kuɲaɲa kuˈɲáɲa kuɲaɲa -ɲaɲa; -pya - -belela

242 to bury kuˈhjɪla kuˈhjɪla kuˈʃiːla kuzika kuˈʃila kusjɪla -siila -higa -taga -tagha

243 grave liˌkaˈbuɾi likabuɾi liˈɲiɲɟa -

maˈɲiɲɟa likabuli likáˈbuɾi likabuli mombwi litinda lítunda 244 to dig (hole) kuˈgíma kugima kuˈhɪmba kugíma kúˈgima kuhola -kima, -yava -gima -emba -hemba

245 *to weed kugehela kukwalalila kugehéˈlela kukwalalila kugehéˈleˑla kugehela -chuva -jipa - -kua

246 to plant kuˈpaˑnda kupanda kuˈpanda mbeju kupanda mbeju kuˈpanda mbeju kupanda mbe

ʝu -yaala -panda -panda -panda

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

248 to grind (grain) kuˈhjaˑɣa kuhjaga / kuhijaga kuˈsaga kuhalula kukuʃaga /

ʃjaga kuhaːlula -haalula -hyaga -hyaga - -pola -hyaga 249 to hunt kuˈhjʊːŋga kuhjuŋga kuˈhjʊŋga kuhjʊŋga kuˈhjʊŋga kufwɪma -fwima -hyuŋga; -ziŋga -benga -benga

250 to cultivate kuˈlɪma kulima kuˈlɪma kulɪma kuˈlɪma kulɪma -lima -lima -gaba -lema

251 *to work kuˈheˑŋga

maˈheŋgo kuheŋga maheŋgo kuˈheŋga liheŋgu kuheŋga liheŋgu kuˈheŋga liˈheŋgu kuβomba -hɛŋga -henga

252 to build kuˈɟeŋga kuɟeŋga kuˈɟeŋga kuɟeŋga kuˈɟeŋga kuɟeŋga -chenga -ɟeŋga -senga -cheŋga

253 to push kuˈkaˑŋga kukaŋga /

kukaŋa kuˈkaŋga kukaŋgá kuˈkaˑŋga kukuŋʊnda -sung'ilichwa -kaŋa -talua - -kanga -kanga

254 to make kutendeˈkesa kuteŋgenesa kuˈwʊmba kuteŋgeneza kutendeˈkesa - -tenda

255 to sew kuˈtota kútota kutota

(kuʃona) kutota

kutota

(nguo) kuhona -hona -tɔta -tota -tota

256 to throw kuˈtaˑga kutaga kuˈtaga kutaga kuˈtaɣa kutaɣa lahiila /

-toocha -taga -lekela

257 to hit kuˈtoʋa kutoʋa kuˈtoʋa kutoʋa kuˈtoʋa kutʊːβa -tova -tɔva -hona; lapu -yatula

258 to slaughter kuˈhɪˑɲɟa kutʃiɲɟa kuˈhɪ́ɲɟa kuhiɲɟa kudúˈmula kuhɪɲɟa -hinja -hinja -sinza -sinza

259 to cut kudúˈmula kudúmula kudúˈmula kudúmula kudúˈmula kudumula

kheeta / ng'enya / -dumula

-dumula -chinja ŋeŋena - - -heketa

260 to wash dishes kuwʊ́ˈjʊla kuwújula / ku

ʋajila kuwʊ́ˈjʊla kuʋájila kuwʊ́ˈjʊla - -

261 *to hide (s.th.) kuˈfíha kufiha kuˈfiha kufiha kuˈfiha kufiha -fiha -hiha; -yuva(lila) -li-hiha - -joba -hia

262 *to marry (man) kutʊ́ˈwʊla kutuwula / kugega kutʊ́ˈwʊˑla kugéga kutʊ́ˈwʊla kugega -keka -gɛga

-togola - -tola mbômba -jukua mbômba

-togola

263 to steal kuˈjɪ́ʋa kujiʋa kuˈhɪɟa kuhekuh ɟa /

ɪɟa kuˈhɪɟa kuhiːɟa -hiicha -yiva -jiba -jiba

264 to kill kuˈkoma kukoma kuˈkoma kukoma kuˈkoma kukoma -vulaka / -buda -kɔma -koma -koma

English

267 to enter kujíˈŋgila kujíŋgila kujíˈŋgila kujiŋgila kujiŋgila kuʝiŋgila -ingila -yiŋgila -jingila -jingila

268 to go out kuˈpita kupita kuˈpiˑta kupita kuˈpita kuhʊma -huuma -huma -pita -pita

269 to move kuhama kuhama kuˈwʊˑka kuˈwʊkuhámili ka / kuˈwʊka kuhama -haama -hama -bʊka -hama

270 to return kukkuwuja ɪ́láˈwʊka / kuwuja kukɪláˈwʊka kuˈwʊja kukɪɾɪβuka -komokha -kiliwuka -buja -kelauka

271 *to dream kuˈlota ˈndoto kulota kuˈlota

ndoto kulota kuˈlota ndoto kuloːta makonafivi -lota -lota ndôtu -lota

272 *to wash clothes kuˈtʃapa

274 *to mix kuhasáˈŋgana kuhasaŋgana kuhasaŋgana kuhasaŋgána kuhasiŋgana / kuhasaŋ gana

kuhasiŋ haɲa

hanjikanyia /

-timbulania -haŋgisana -haŋgaŋgana

-hangang

ndjaŋgu kudɪndula -sinjila -dindula -hogola -jogola

276 to shut kuˈdɪnda kuɗenda kudɪnda

280 to cover (a pot) kugúbaˈkila kugubukila / kugubikila kugubáˈkila kugubákila kugubáˈkila kugubika -kubikha -gubákìla -hyekalela -hyekalela

English

Gloss Lituhi

Litumba

Kuhamba Nsungu Luilo Iwela Kisi Pangwa Ngoni Matengo Mpoto

282 to follow kukɪsa /

kufaːta kufaːta kuˈkɪsa kufaːta kuˈkɪsa kukiːsja -khinja -landa -jengalela -pwata

283 to get lost kuˈhoʋa kujaga kuˈsoʋa kujaga kuˈsoʋa kuʝaɣa -yaka -hova / -yaga -hoba -hoba

284 to stir kukóɲɟaˈgana kukologa kukoɲɟa

ˈgana kukoɲɟigana kukíˈɾiga kutimbula -khilika -konjogana -kolog'ana 285 to knock kugoŋga

litaŋga kugoŋga kugoŋga kundjaŋgu kugoŋga kupndjaŋguʊta ana kuβweʝul- -konga -koŋonda -koŋonda -pota 286 to take leave kuˈlaga kulaga kuˈlaɣa kulaga kuˈlaga kwilaɣa -ilaka -laga -litabuka -lagi

287 *to swallow kuˈmila kumila kuˈmila kumila kuˈmila kumila -mila -hɔpa; mila -mila -mila

288 *to curse kulápaˈkɪsa kulapakisa kundaˑni kulaani kumpela

luˈkoto kumpeːla ljepa -lekha lulekho -luːmba - -loga

289 to smell kunusa kunusa kuˈnusa kubema kunʊsa kunuːsja -nuusa -nuha -nuha -nua

290 to kneel kupiga mafugamilu kupiga magoti kupiga

mafugáˈmilu kufugama kufugama kufugama -fukama -fugama -pega magote

291 to take a

bath kujoɣa kujoga kuˈjoga kujoga kuˈjoɣa kwiʝoɣa -yoka -samba -hoga -joɣa

292 to dive kusuɣáˈlɪla kujogelela kujogáˈleˑla kujogelela / kusugalɪla

kujiʋila kintʊndʊ

-tova ikhimasela 293 to gossip kuˈheha kuheha kuˈheˑha kuhéha kuˈheha kuheːha -heeha

294 to leave kukóˈtoˑka kuleka kuˈleka kuleka kukóˈtoka / kuleka kuleka -sikala -lɛka -leka kukotoka

295 to remain, stay kuhiˈgasa kubakisa kusíˈɣasa kusigisa kusigasa kusiɣala -sikala -higala -higala higalila

32

Anderson, Heidi, Susanne Krüger, and Louise Nagler. 2003a. A sociolinguistic survey of the Manda language community. Unpublished ms.

Anderson, Heidi, Susanne Krüger, Joseph W. Gathumbi, and Louise Nagler. 2003b. A sociolinguistic survey of the Pangwa language community. Unpublished ms.

Bastin, Yvonne, André Coupez, Evariste Mumba, and Thilo C. Schadeberg, eds. 2003. Bantu lexical reconstructions 3. Tervuren: Royal Museum for Central Africa.

http://linguistics.africamuseum.be/BLR3.html, accessed July 29, 2015.

Batibo, Herman M. 2000. The state of spirantization in Sukuma-Nyamwezi: A historical account. In Kulikoyela Kanalwanda Kahigi, Yared Kihore, and Maarten Mous (eds.), Lugha za Tanzania/The languages of Tanzania: Papers in memory of C. Maganga, 18–25. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Bryant, David, and Vincent Moulton. 2004. Neighbor-Net: An agglomerative method for the construction of phylogenetic networks. Molecular Biology and Evolution 21 (2): 255–265.

Ehret, Christopher. 1999. Sub-classifying Bantu: The evidence of stem-morpheme innovations. In Hombert and Hyman (eds.), Bantu historical linguistics: Theoretical and empirical perspectives, 43–147. Stanford: CSLI.

Ehret, Christopher. 2009. Bantu subclassifications.

http://www.sscnet.ucla.edu/history/ehret/BantuClassification%204-09.pdf, accessed October 18,

2010.

Gray, Hazel. Forthcoming. A grammar sketch of Manda. Unpublished ms.

Gray, Hazel, and B. Mitterhoffer. 2016. A sociolinguistic survey of the Manda/Matumba language communities. Ms.

Guthrie, Malcolm. 1971. Comparative Bantu: An introduction to the comparative languages and prehistory of the Bantu languages. Vol. 2. London: Gregg International Publishers Ltd.

Hinnebusch, Thomas. 1999. Contact and lexicostatistics in comparative Bantu studies. In Hombert and Hyman (eds.), Bantu historical linguistics: Theoretical and empirical perspectives, 173–205. Stanford: CSLI.

Holden, Clare J., and Russell D. Gray. 2006. Rapid radiation, borrowing and dialect continua in the Bantu languages. In Peter Forster, and Colin Renfrew (eds.), Phylogenetic methods and the prehistory of languages, 19–31. Cambridge: McDonald Institute for Archeological Research.

Hombert, Jean-Marie, and Larry M. Hyman, eds. 1999. Bantu historical linguistics: Theoretical and empirical perspectives. Stanford: CSLI.

Huson, Daniel H., and David Bryant. 2010. SplitsTree4, Version 4.11.3 Downloaded from:

http://www.splitstree.org/; February 1, 2011.

Lewis, M. Paul, Gary F. Simons, and Charles D. Fennig, eds. 2015. Ethnologue: Languages of the world,

Eighteenth edition. Dallas, Texas: SIL International. Online version: http://www.ethnologue.com. Maho, Jouni Filip. 2009. New Updated Guthrie List, NUGL Online.

http://goto.glocalnet.net/mahopapers/nuglonline.pdf, accessed October 18, 2010.

Mühlhäusler, Peter. 1996. Introduction. In Charles-James N. Bailey, Essays on time-based linguistic analysis. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Nichols, Johanna. 1996. The comparative method as heuristic. In Mark Durie, and Malcolm Ross (eds.),

The comparative method reviewed: Regularity and irregularity in language change, 39–71. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Nurse, Derek. 1988. The diachronic background to the language communities of SW Tanzania. Sprache

und Geschichte in Afrika, 9: 15–115.

Nurse, Derek. 1999. Towards a historical classification of East African Bantu languages. In Hombert and Hyman (eds.), Bantu historical linguistics: Theoretical and empirical perspectives, 1–41. Stanford: CSLI. Nurse, Derek. 2008. Tense and aspect in Bantu. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nurse, Derek, and Gerard Philippson. 1975. Bantu dictionary and wordlist databases.

http://www.cbold.ish-lyon.cnrs.fr/, accessed July 29, 2015.

Nurse, Derek, and Gerard Philippson. 1980. The Bantu languages of East Africa: A lexicostatistical survey. In E. C. Polomé, and C. P. Hill (eds.), Language in Tanzania, 22–67. Oxford: Oxford University Press / International African Institute.

Pelkey, Jamin R. 2011. Dialectology as dialectic: Interpreting Phula variation. Berlin, New York: De Gruyter Mouton.

Roth, Tim. 2011. The genetic classification of Wungu: Implications for Bantu historical linguistics. M.A. thesis. Trinity Western University, Langley.

Schadeberg, Thilo C. 2003. Historical linguistics. In D. Nurse, and G. Philippson (eds.), The Bantu languages, 143–163. London: Routledge.

Tadmor, Uri. 2009. Loanwords in the world’s languages: Findings and results. In M. Haspelmath, and U. Tadmor (eds.), Loanwords in the world’s languages: A comparative handbook, 55–75. Berlin: De Gruyter Mouton.