Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:26

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Moral Disengagement in Science and Business

Students: An Exploratory Study

Suzanne N. Cory

To cite this article: Suzanne N. Cory (2015) Moral Disengagement in Science and Business Students: An Exploratory Study, Journal of Education for Business, 90:5, 270-277, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1027162

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1027162

Published online: 16 Apr 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 47

View related articles

Moral Disengagement in Science and Business

Students: An Exploratory Study

Suzanne N. Cory

St. Mary’s University, San Antonio, Texas, USA

Cases of unethical business practices and technical failures have been extensively reported. It seems that actions are often taken by individuals with little apparent concern for those affected by their negative outcomes, which can be described as moral disengagement. This study investigates levels of moral disengagement demonstrated by business and science undergraduate students. Results indicate higher levels of moral disengagement in men than in women, but few significant differences between students majoring in business and those majoring in science.

Keywords: gender differences in ethicality, moral disengagement, technical failures, undergraduate business students, undergraduate science students, unethical business practices

Cases of unethical business practices and high-profile engi-neering failures have dominated past headlines. These prac-tices have resulted in preventable deaths and environmental destruction as well as loss of financial resources. Both busi-ness people and scientists are often responsible for these events.

Significance of the Issue

Acting irresponsibly without regard to ethical obligations or thinking about others and the possible repercussions of an individual’s decisions can result in negative consequences. Having the ability and the desire to pursue fraudulent activ-ities is only one measure of acts resulting in negative conse-quences for others. An individual’s acting in self-interest, taking inappropriate risks, disregarding warning signs, or demonstrating a caviler attitude toward the welfare of others can result in damage to the environment, unneces-sary deaths, or financial disasters. The lack of concern dem-onstrated by the disassociation of acts and the results of those acts can be fueled by higher levels of moral dis-engagement. Moral disengagement allows an individual to disassociate his or her actions from the consequences of

those actions and removes the restraint of self-censure. There are numerous reports of negative consequences that result when individuals or groups act in a morally disen-gaged manner.

For example, the accounting scandals that were unveiled in the early 2000s and the 2008 financial crisis were brought on by chief executive officers (CEOs), certified public accountants (CPAs), bankers, and other business people who benefitted themselves at the expense of others. In one instance, Fabrice (“Fabulous Fab”) Tourre, a Gold-man Sachs vice president, helped create a subprime mort-gage investment deal called Abacus 2007-AC1. The debt obligation defrauded investors and secretly allowed billion-aire John Paulson’s hedge fund to make a billion dollars by betting against the fund (Rochan, 2013).

Other examples of unethical business practices abound. One need look only at the results of the Enron and World-Com scandals to observe the impact of unethical behavior on the lives of others. Both financial disasters resulted in prison sentences for some of the individuals involved, as well as financial losses for investors, employees and other parties. Yet, Kenneth Lay, former Enron CEO, had been recognized for his community involvement and philan-thropic activities in Houston until his leading role in the company’s corruption scandal was discovered. WorldCom was the largest accounting scandal in U.S. history until Ber-nard Madoff’s Ponzi scheme was brought to light. Madoff, who built an empire out of his own investment firm and

Correspondence should be addressed to Suzanne N. Cory, St. Mary’s University, Bill Greehey School of Business, Department of Accounting, One Camino Santa Maria, San Antonio, TX 78228, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1027162

developed technology that would later become the NAS-DAQ (Bandler, Varchaver, Burke, Kimes, & Abkowitz, 2009), is currently serving 150 years in a maximum-secu-rity prison. Madoff admitted to perpetrating a massive Ponzi scheme that covered several continents and lasted decades, defrauding his clients out of millions. Inappropri-ate actions on the part of professionals that result in harm to others are certainly not limited to the business arena. Those in engineering, sciences, and other related disciplines have taken actions that resulted in injury to others.

For instance, in 2010 the explosion of the Deepwater Horizon oil drilling rig in the Gulf of Mexico has been blamed on failure to heed warnings regarding structural weaknesses in cement casings that were designed to protect the well pipes. Further, management was aware that the blowout preventer had not been working properly for sev-eral days prior to the disaster. Management did not intend for the rig to explode, kill 11 crewmen, and spurt 210 million gallons of oil into the Gulf. However, errors in judgment and lack of concern about the repercussions of a possible blowout preventer malfunction certainly contrib-uted to the catastrophe.

Another example of negative consequences resulting from errors in judgment and a lack of concern for the lives of others occurred in 2003, when missing heat shield tiles on the shuttle’s leading edge caused the Columbia to disintegrate upon atmospheric re-entry, killing all seven astronauts onboard. Heat shield problems had been discovered in earlier shuttle missions and NASA’s administration was aware of the damage to the Columbia. But no plan for repairing or replacing heat shield tiles on the shuttle while in space and thus protecting the astronauts’ lives had ever been pursued.

Taking shortcuts to save time transporting oil to South-ern California refineries was partially to blame for 11 million gallons of crude oil spilling out of the Exxon Valdez tanker in 1989 when it ran aground. The uninten-tional resulting loss of wild life and pristine beauty of the Alaskan shores is difficult to measure, but could have been prevented if management had focused on preparation and planning for cleaning up spills rather than on cost minimization.

The epitome of unethical behavior is illustrated by the technological professionals who designed Nazi death cham-bers and lethal gas delivery systems that resulted in the extermination of millions. Katz (2011) explained how he believes the individuals who planned and created these facilities allowed and accepted their involvement in their design. He asserted a doubling of their personalities occurred, which allowed one part of their personalities to focus on required scientific specifications, with no concern for the end results of the actual implementation of the designs. In other words, they were able to disengage a part of their persona and successfully ignore the moral implica-tions of what they were doing. This could also be consid-ered moral disengagement.

Statement of the Problem

In each of the previous examples, the actions of business people and scientists collided, resulting in disasters of vary-ing dimensions. Individuals involved in these scenarios are often highly educated, obtaining at least an undergraduate degree in their area of specialization. In light of the inci-dents described above, it is important to consider whether individuals in business and in sciences are susceptible to moral disengagement. The question then arises as to whether individuals who study business or those who study in the science arena have higher levels of moral disengage-ment, which allows them to take risks that may result in negative consequences for others.

The purpose of this article is to report the results of a pilot study measuring moral disengagement of undergradu-ate students in various disciplines. More specifically, this study focuses on measuring moral disengagement of under-graduates studying business or science. Additionally, differ-ences in moral disengagement between genders are investigated. Given that this is an exploratory study, no spe-cific hypotheses are developed. Rather, measurement of students’ moral disengagement and differences in moral disengagement between the two groups and between gen-ders are determined. Results may lead to further research in this area and perhaps changes in the ethics curriculum.

Prior Research

Albert Bandura developed the theory of moral disengage-ment in 1986, and his theory explained that an individual’s self-regulatory mechanisms do not operate unless they are activated (Bandura, 2002). This theory attempts to explain why some individuals are able to suffer little or no personal distress from engaging in acts deemed unethical or unlaw-ful by society. Bandura’s theory indicates that high levels of moral disengagement allow an individual to disassociate from the results or implications of his or her actions even if these actions will negatively affect others. Bandura pro-posed three categories of mechanisms used by individuals to achieve this dissociation. The first is cognitively restruc-turing behavior demonstrated by moral justification, euphe-mistic labeling, and advantageous comparison. The second is obscuring or minimizing an individual’s active role in behaviors by displacing responsibility, diffusing responsi-bility, and disregarding or distorting the consequences of an action. The final category is focusing on the unfavorable acts or traits of those negatively affected by dehumanizing victims and attributing blame.

Bandura’s theories of moral disengagement have been applied to societal issues such as terrorism (Maikovich, 2005), the perpetration of inhumanities (Bandura, 1990), cubicle warriors (Royakkers & van Est, 2010), executioners (Osofsky, Bandura, & Zimbardo, 2005) and school bullies (Obermann, 2011). The implosion of our economy in 2008

MORAL DISENGAGEMENT IN SCIENCE AND BUSINESS STUDENTS 271

and fraudulent incidents in the early 2000s has generated interest in applying Bandura’s theories to business.

Some studies have been industry specific such as in J. White, Bandura, and Bero (2009), which looked at moral disengagement exhibited in harmful corporate research related to tobacco, lead, vinyl chloride, and silicosis. Ntayi, Eyaa, and Ngoma (2010) delved into the unethical practices of public procurement officers in Uganda. Other studies such as Claybourn’s 2011 investigation questioned whether work related variables and moral disengagement influence negative behaviors such as work place harassment. Moore, Detert, Trevi~no, Baker, and Mayer (2012) investigated why employees do bad things in the workplace. Barsky (2011) and Anand, Ashforth, and Joshi (2005) researched moral disengagement and how it relates to the rationalization of unethical or corrupt acts in the workplace. Anand et al. claimed that, based on their study, virtually every organiza-tion suffers from fraud.

Application of Bandura’s theories in the sciences is less pervasive. However, use of student subjects has intensified. Using undergraduate students as subjects, Hinrichs, Wang, Hinrichs, and Romero (2012) examined the relationship between leadership beliefs and moral disengagement through displacement of responsibility. Tsai, Wang and Lo (2014) explored the relationships among locus of con-trol, moral disengagement in sport and rule transgression of athletes, using members of a college sports team as subjects.

Previous studies have focused on general moral disengage-ment tendencies among students, such as Detert, Trevi~no, and Sweitzer’s 2008 study, which compared moral disengage-ment tendencies among college freshmen majoring in busi-ness and those majoring in education. The study tested the relationships between empathy, moral identity, trait cynicism, and locus of control compared to higher levels of moral dis-engagement. Ultimately, the study found a negative associa-tion between empathy and moral identity, but a positive association between trait cynicism and locus of control. The results indicated higher levels of moral disengagement in business majors as compared to education majors.

Other studies focused on a particular behavior when test-ing moral disengagement tendencies. For example, Btest-ing et al. (2012) performed an experiment with college students involving academic cheating. Morgan and Neal (2011) compared students’ perceptions of ethical breaches with freshmen and upper level students in information systems courses. Baird and Zelin (2009) used undergraduate stu-dents to study whether a person committing fraud in a situa-tion involving obedience pressure was judged less harshly than an individual committing fraud of his or her own voli-tion. Each year more studies are being conducted using undergraduate students to research not only how these stu-dents view and judge moral disengagement, but how those views and judgments differ over time and when compared to students across disciplines.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Investigations into moral disengagement pertaining to stu-dents in both higher and lower education have incorporated Bandura’s theory. The purpose of this article is to report the findings of an exploratory study using undergraduate stu-dents who are earning bachelor degrees in business or in the sciences. These two student groups were chosen for this study because of the importance of understanding the ethi-cal inclinations of tomorrow’s leaders in these fields. Fur-ther, given their eventual employment opportunities coupled with the ability to put the financial or physical wel-fare of others at risk, or implement unsafe practices, it is important to consider whether individuals majoring in these disciplines are more susceptible to moral disengagement.

The survey provided in the Appendix was adapted from Detert et al. (2008). Their survey was adapted from one developed and used in multiple studies by Bandura and others (e.g., Bandura, Barbaranelli, Caprara, Barbaranelli, & Pastorelli, 1996; Pelton, Gound, Forehand, & Brody, 2004). The survey was designed in order to measure each of the eight components of moral disengagement equally with four questions per component. Given that the survey, or one very similar to it, has been used in previous research (e.g. Bandura et al., 1996; Detert et al., 2008; Pelton et al., 2004) and previously tested extensively for validity, no further tests of validity were deemed necessary.

Students were presented with a list of 32 statements and asked to determine the degree to which they agreed with each, using a 7-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). Questions 1–4 measured moral justification, questions 5–8 measured euphemistic labeling, and questions 9–12 measured advan-tageous comparisons. Questions 13–16 measured displace-ment of responsibility, questions 17–20 measured diffusion of responsibility, and questions 21–24 measured distortion of consequences. Last, questions 25–28 measured attribu-tion of blame, and quesattribu-tions 29–32 measured dehumaniza-tion. Responses to each subset of questions were summed to obtain the measurement for that part of the survey and a grand total was obtained by adding all responses from each respondent.

The survey was given to students taking a general educa-tion course in the fall 2013 semester at a small private lib-eral arts university in the southwest. Total enrollment in 15 sections of the course was 274 undergraduate students and 249 usable responses were received. This resulted in a 91% response rate. In order to analyze responses from the two subgroups of interest, responses from students who were not majoring in business or in the sciences were dis-carded. The remaining sample consisted of 148 responses, of which 53 were completed by business majors and 95 by science majors. There were 33 men majoring in business, with an average age of 18.8 years and 20 women with an average age of 18.2 years. The average age of the 54 men

majoring in the sciences was 18.35 years and the 41 women averaged 18.4 years of age. The science majors included environmental science, engineering, biochemistry, premed, chemistry, biology, and physics. Typical business majors included accounting, finance, marketing, interna-tional business and management. Levels of moral dis-engagement within each group and any differences between the two groups should be of interest.

FINDINGS

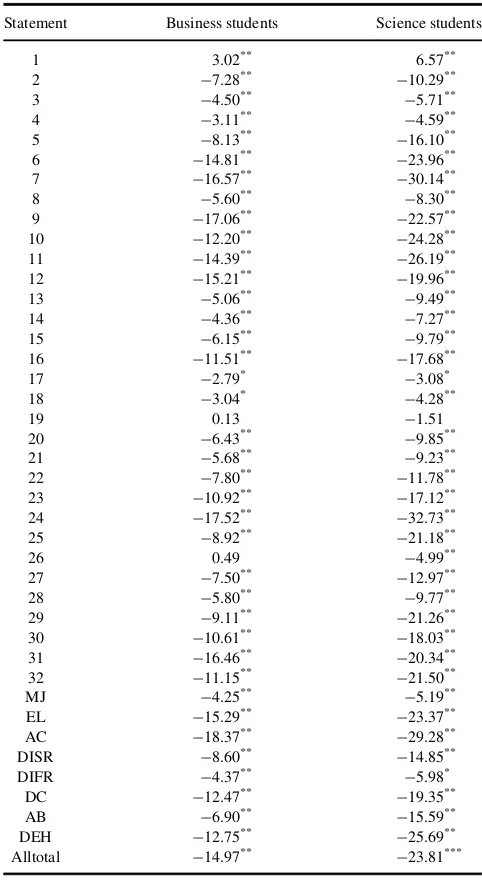

First, the responses were analyzed for each group of stu-dents. Results of thet-test are shown in Table 1. In almost all cases (38 of 41 for the business students and 39 of 41 for the science majors) the students disagreed with the state-ments. However, both groups of students agreed with the first statement (“It is alright to fight to protect your friends”). Neither group strongly agreed or disagreed with statement 19 (“If a group decides together to do something harmful, it is unfair to blame any one member of the group for it”). The science majors strongly disagreed with state-ment 26 (“If someone leaves something lying around, it’s their own fault if it gets stolen”), but the business majors neither strongly agreed nor disagreed with it.

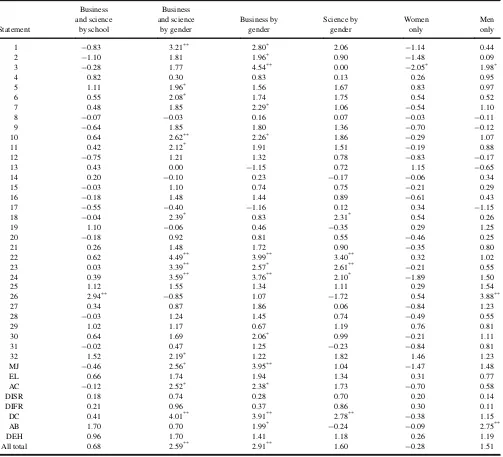

Next, differences in the responses to the survey ques-tions between business majors and science majors were analyzed. Results are shown in column 2 of Table 2. The responses to each question, each category, and the total score were analyzed. Of the 41 comparisons, only one was significantly different between the two groups. Business majors’ mean was higher than that of science majors. col-umn 3 of Table 2 shows the results oft-tests for differences between genders for the total sample. Fourteen significant differences were found and, in every case, responses from men averaged a higher score (more likely to agree with the statement) than responses from women. The question then arose whether gender differences within each school might exist. Therefore,t-tests were computed for response differ-ences between genders within business and within science. Results are shown in columns 4 and 5 of Table 2, respectively.

Fourteen significant differences were found between responses from men and women for the business majors, and five were found for the science majors. Again, in every case, the average response for men was higher than the average response for women. Finally, the responses were divided into two groups based on gender to determine whether any differences could be found between the two disciplines. Results are shown in the last two columns of Table 2. Only one significant difference was found between disciplines for the women (column 6). Women majoring in science had a higher mean than their business major coun-terparts. For men (column 7), three significant differences were found and in every case the average score was higher

for men majoring in business than for men majoring in sci-ence, indicating that male business majors agreed more strongly with the statement than did their counterparts majoring in science.

Based on these results, it seems that women are far less likely to justify immoral actions by using moral disengage-ment tactics. In every comparison wheret-tests indicated a significant difference, the average response from women

TABLE 1

t-Tests for Business and Science Students

Statement Business students Science students

1 3.02** 6.57**

Note: Positivetscore indicates higher level of moral disengagement. ABDattribution of blame; ACDadvantageous comparisons; DCD

dis-tortion of consequences; DEHDdehumanization; DIFRDmeasured

diffu-sion of responsibility; DISRDmeasured displacement of responsibility;

ELDeuphemistic labeling; MJDmoral justification.

*p<.05, **p<.01.

MORAL DISENGAGEMENT IN SCIENCE AND BUSINESS STUDENTS 273

was lower than that for men, which indicates less agreement with the statement. This was true when analyzing results for the full sample between genders (column 3 of Table 2) and within each school by gender (columns 4 and 5 in Table 2). Perhaps these findings should be expected, given past research on differences between the genders in moral devel-opment or moral judgment. For example, Lv and Huang (2012) found gender differences in ethical intentions and

moral judgment in accounting students, but found those dif-ferences were negligible for accounting practitioners, sug-gesting that these disparities fade in the workplace. Also, R. D. White (1999) had similar results for gender differen-ces in moral reasoning. His results indicated that women employed in the public sector had higher levels of moral reasoning than their male counterparts. Whipple and Swords (1992) found consistently higher business ethics for

TABLE 2 t-Tests by Demographic

Statement

Business and science

by school

Business and science

by gender

Business by gender

Science by gender

Women only

Men only

1 ¡0.83 3.21** 2.80* 2.06 ¡1.14 0.44

2 ¡1.10 1.81 1.96* 0.90 ¡1.48 0.09

3 ¡0.28 1.77 4.54** 0.00 ¡2.05* 1.98*

4 0.82 0.30 0.83 0.13 0.26 0.95

5 1.11 1.96* 1.56 1.67 0.83 0.97

6 0.55 2.08* 1.74 1.75 0.54 0.52

7 0.48 1.85 2.29* 1.06 ¡0.54 1.10

8 ¡0.07 ¡0.03 0.16 0.07 ¡0.03 ¡0.11

9 ¡0.64 1.85 1.80 1.36 ¡0.70 ¡0.12

10 0.64 2.62** 2.26* 1.86 ¡0.29 1.07

11 0.42 2.12* 1.91 1.51 ¡0.19 0.88

12 ¡0.75 1.21 1.32 0.78 ¡0.83 ¡0.17

13 0.43 0.00 ¡1.15 0.72 1.15 ¡0.65

14 0.20 ¡0.10 0.23 ¡0.17 ¡0.06 0.34

15 ¡0.03 1.10 0.74 0.75 ¡0.21 0.29

16 ¡0.18 1.48 1.44 0.89 ¡0.61 0.43

17 ¡0.55 ¡0.40 ¡1.16 0.12 0.34 ¡1.15

18 ¡0.04 2.39* 0.83 2.31* 0.54 0.26

19 1.10 ¡0.06 0.46 ¡0.35 0.29 1.25

20 ¡0.18 0.92 0.81 0.55 ¡0.46 0.25

21 0.26 1.48 1.72 0.90 ¡0.35 0.80

22 0.62 4.49** 3.99** 3.40** 0.32 1.02

23 0.03 3.39** 2.57* 2.61**

¡0.21 0.55

24 0.39 3.59** 3.76** 2.10*

¡1.89 1.50

25 1.12 1.55 1.34 1.11 0.29 1.54

26 2.94** ¡0.85 1.07 ¡1.72 0.54 3.88**

27 0.34 0.87 1.86 0.06 ¡0.84 1.23

28 ¡0.03 1.24 1.45 0.74 ¡0.49 0.55

29 1.02 1.17 0.67 1.19 0.76 0.81

30 0.64 1.69 2.06* 0.99 ¡0.21 1.11

31 ¡0.02 0.47 1.25 ¡0.23 ¡0.84 0.81

32 1.52 2.19* 1.22 1.82 1.46 1.23

MJ ¡0.46 2.56* 3.95** 1.04 ¡1.47 1.48

EL 0.66 1.74 1.94 1.34 0.31 0.77

AC ¡0.12 2.52* 2.38* 1.73 ¡0.70 0.58

DISR 0.18 0.74 0.28 0.70 0.20 0.14

DIFR 0.21 0.96 0.37 0.86 0.30 0.11

DC 0.41 4.01** 3.91** 2.78**

¡0.38 1.15

AB 1.70 0.70 1.99*

¡0.24 ¡0.09 2.75**

DEH 0.96 1.70 1.41 1.18 0.26 1.19

All total 0.68 2.59** 2.91** 1.60

¡0.28 1.51

Note: Positivetscore indicates males have higher mean or business major has higher mean. ABDattribution of blame; ACDadvantageous comparisons;

DCDdistortion of consequences; DEHDdehumanization; DIFRDmeasured diffusion of responsibility; DISRDmeasured displacement of responsibility;

ELDeuphemistic labeling; MJDmoral justification.

*p<.05, **p<.01.

female college students than for their male counterparts in both the United States and in the United Kingdom. How-ever, the number and the strength of differences for survey responses between men and women are still somewhat sur-prising. There were 41 comparisons made in each of the three columns (columns 3–5) of results referred to above and presented in Table 2, which totals 123. Of those 123 comparisons, a total of 33 were significantly different between the genders (26%) at least at the 5% level.

Only one significant difference was found in the average responses from women majoring in business and those majoring in sciences (column 6 of Table 2). The female sci-ence majors agreed more strongly with statement 3 (“It’s ok to attack someone who threatens your family’s honor”). When comparing responses from men between schools, three instances were found in which responses from men majoring in business were significantly higher than from men majoring in sciences: “It’s ok to attack someone who threatens your family’s honor” (statement 3), “If someone leaves something lying around, it’s their own fault if it gets stolen and for attribution of blame (statement 26); sum of questions 25–28). Notably, the single difference found between the two subgroups, based on major was also for statement 26 (column 2).

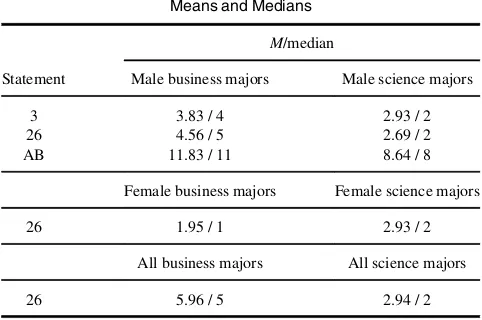

In order to better understand the responses that were sig-nificantly different between women majoring in business and women majoring in science as well as for men majoring in business and men majoring in science, the mean and median scores were determined and are presented in Table 3. The mean and the median for all business majors and all sciences majors for statement 26 are also presented in Table 3.

For statement 3, the mean average score for male busi-ness majors was 3.83, which is closer to 4 (neither agree nor disagree) but the mean average for male science majors was closer to 3 and farther away from neither agree nor dis-agree. The median was 4 for the male business majors and 2 for the male science majors. Hence, male business majors

agreed slightly with the statement, but male science majors disagreed. For statement 26, the mean average for male business majors was about half way between 4 and 5, but the mean average for male science majors was about half way between 2 and 3. The medians were 5 and 2, respec-tively. Thus, male business majors agreed with the state-ment, but male science majors did not agree with it at all, based on both the mean the median. The mean average for male business majors for attribution of blame (the sum of statements 25–28, which results in a minimum of 4 and a maximum of 28) was closer to 12, with a median of 11, but the mean average for male science majors was about half-way between 8 and 9, with a median of 8. The mean for female business majors for statement 26 is very close to 2 and the median is 1. However, the mean for the female sci-ence majors is very close to 3, with a median of 2. Thus, neither group agreed with the statement, but female busi-ness majors agreed with it less. Finally, the mean for all business majors for statement 26 was very close to 6 with a median of 5, but the mean for all science majors was close to 3, with a median of 2. Therefore, on average, business majors slightly agreed with the statement, but science majors slightly disagreed with it.

These results are somewhat inconsistent with previous research in the area of ethical development differences between business students and science students. For exam-ple, Neubaum, Pagell, Drexler, Mckee-Ryan, and Larson (2009) found no differences in personal moral philosophy between business and non-business students. However, these findings are consistent with Segal, Gideon, and Haberfield (2011) who found that business students were more willing to accept unethical conduct than criminal justice majors and Cory and Hernandez (2014) who found that business students demonstrated higher levels of moral disengagement than humanities majors.

CONCLUSION

To summarize the results of this pilot study, only one sig-nificant difference of the 42 comparisons was found when comparing all business majors with all sciences majors. However, several differences were found when comparing responses from men and women both for the total sample and within each major classification. In every case, men exhibited a higher level of moral disengagement tendencies than did the women. Finally, when comparing women between disciplines, only one difference was found, but three differences were found when comparing men by dis-cipline. In every case where a difference was found with men, business majors were more likely to agree with the statement than sciences majors, indicating a higher level of moral disengagement. However, the only difference found between responses from women by discipline indicated a higher level of moral disengagement in science majors.

TABLE 3 Means and Medians

M/median

Statement Male business majors Male science majors

3 3.83 / 4 2.93 / 2

26 4.56 / 5 2.69 / 2

AB 11.83 / 11 8.64 / 8

Female business majors Female science majors

26 1.95 / 1 2.93 / 2

All business majors All science majors

26 5.96 / 5 2.94 / 2

Note: ABDattribution of blame.

MORAL DISENGAGEMENT IN SCIENCE AND BUSINESS STUDENTS 275

The results of the study do not necessarily indicate that, in general, male science students are less morally disen-gaged than male business students. However, differences found between the two groups of students are interesting. Given that ethics courses are required for most college majors, these results may indicate the necessity of increased coverage in certain areas. More specifically, consequences of an individual’s acting solely in self-interest, inappropri-ateness of indifference to possible negative outcomes of actions, possible repercussions to others of taking unneces-sary risks, and possible negative results of inattention to detail, in addition to the unethical behavior of stealing or committing fraud, should be reinforced. Further, the differ-ences in results based on gender imply that men may need more ethics education than women, at least in terms of moral disengagement measures. Those who are teaching ethics at the university level should be made aware of the necessity of including the previous information in the cur-riculum. Moral disengagement may result in adverse conse-quences to others, even if fraud is not directly involved in the actions taken by an individual. Further, it appears that increased coverage and reinforcement of these topics may be necessary in business curricula.

There are certainly limitations to this study. Only stu-dents enrolled in one general education course at one uni-versity completed the survey and their selection was not random. Further, only lower division students were sur-veyed and ethical maturity may have not yet occurred. However, these limitations may be addressed with future research related to this topic.

REFERENCES

Anand, V., Ashforth, B. E., & Joshi, E. (2005). Business as usual: The acceptance and perpetuation of corruption in organizations.Academy of

Management Executive,19(4), 9–23.

Baird, J. E., & Zelin, R. C. II (2009). An examination of the impact of obe-dience pressure on perceptions of fraudulent acts and the likelihood of committing occupational fraud.Journal of Forensic Studies in Account-ing and Business,1, 1–14.

Bandler, J., Varchaver, N., Burke, D., Kimes, M., & Abkowitz, A. (2009). How Bernie did it.Fortune,159(10), 50–71.

Bandura, A. (1990). Moral disengagement in the perpetration of inhumani-ties.Personality and Social Psychology Review,3, 193–209.

Bandura, A. (2002). Selective moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency.Journal of Moral Education,31, 101–119.

Bandura, A., Barbaranelli, C., Caprara, G. V., & Pastorelli, C. (1996). Mechanisms of moral disengagement in the exercise of moral agency.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,71, 364–374.

Barsky, A. (2011). Investigating the effects of moral disengagement and participation on unethical work behavior.Journal of Business Ethics,

104, 59–75.

Bing, M. N., Davison, H. K., Vitell, S. J., Ammeter, A. P., Garner, B. L., & Novicevic, M. M. (2012). An experimental investigation of an interac-tive model of academic cheating among business school students.

Acad-emy of Management Learning & Education,11, 28–48.

Claybourn, M. (2011). Relationships between moral disengagement, work characteristics and workplace harassment.Journal of Business Ethics,

100, 283–301.

Cory, S. N., & Hernandez, A. R. (2014). Moral disengagement in business and humanities majors: An exploratory study.Research in Higher

Edu-cation Journal,23. Retrieved from http://www.aabri.com/manuscripts/

141808.pdf

Detert, J. R., Trevi~no, L. K., & Sweitzer, V. L. (2008). Moral disengage-ment in ethical decisions making: A study of antecedents and outcomes.

Journal of Applied Psychology,93, 163–178.

Hinrichs, K. T., Wang, L, Hinrichs, A. T., & Romero, E. J. (2012). Moral disengagement through displacement of responsibility: The role of leadership beliefs.Journal of Applied Social Psychology,42, 62–80.

Katz, E. (2011). The Nazi engineers: Reflections on technological ethics in Hell.Science and Engineering Ethics,17, 571–582.

Lv, W., & Huang, Y. (2012). How workplace accounting experience and gender affect ethical judgment.Social Behavior and Personality: An

International Journal,4, 1477–1483.

Maikovich, A. K. (2005). A new understanding of terrorism using cogni-tive dissonance principles.Journal for the Theory of Social Behavior,3, 373–397.

Moore, C., Detert, J. R., Trevi~no, L. K., Baker, V. L., & Mayer, D. M. (2012). Why employees do bad things: Moral disengagement and uneth-ical behavior.Personnel Psychology,65, 1–48.

Morgan, J., & Neal, G. (2011). Student assessments of information systems related ethical situations: Do gender and class level matter?Journal of Legal, Ethical, Regulatory Issues,14, 113–130.

Neubaum, D. O., Pagell, M., Drexler, J. A. Jr., Mckee-Ryan, F. M., & Lar-son, E. (2009). Business education and its relationship to student per-sonal moral philosophies and attitudes towards profits: An empirical response to critics.Academy of Management Learning and Education,

8, 9–24.

Ntayi, J. M., Eyaa, S., & Ngoma, M. (2010). Moral disengagement and the social construction of procurement officers’ deviant behaviors.Journal

of Management Policy and Practice,11(4), 95–110.

Obermann, M. L. (2011). Moral disengagement in self-reported and peer-nominated school bullying.Aggressive Behavior,37, 133–144. Osofsky, M. J., Bandura, A., & Zimbardo, P. G. (2005). The role of moral

disengagement in the execution process.Law and Human Behavior,29, 371–393.

Pelton, J., Gound, M., Forehand, R., & Brody, G. (2004). The moral dis-engagement scale: Extension with an American minority sample.

Jour-nal of Psycholpathology and Behavioral Assessment,26, 31–39.

Rochan, M. (2013, November 14). SEC demands former Goldman Sachs VP Fabrice Tourre’s salary details. International Business Times. Retrieved from http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/sec-fabrice-tourre-salary-details-sub-prime-522248

Royakkers, L., & van Est, R. (2010). The cubicle warrior: The marionette of digitalized warfare,Ethics and Information Technology,

12, 289–296.

Segal, L., Gideon, L., & Haberfield, M. R. (2011). Comparing the ethical attitudes of business and criminal justice students.Social Science Quar-terly,9, 1021–1043.

Tsai, J. J., Wang, C. H., & Lo, H. J. (2014). Locus of control, moral dis-engagement in sport and rule transgression of athletes.Social Behavior and Personality,42, 59–68.

Whipple, T. W., & Swords, D. F. (1992). Business ethics judgments: A cross-cultural comparison.Journal of Business Ethics,11, 671–678. White, J., Bandura, A., & Bero, L. A. (2009). Moral disengagement in the

corporate world.Accountability in Research,16, 41–74.

White, R. D. (1999). Are women more ethical? Recent findings on the effects of gender upon moral development.Journal of Public

Adminis-tration Research and Theory,9, 459–471.

APPENDIX—QUESTIONNAIRE

Strongly disagree Neither Strongly agree

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Choose a number from 1 to 7 from the scale above, based on how strongly you agree or disagree with each statement. Put the number in the space provided.

1. __It is alright to fight to protect your friends. 2. __It’s ok to steal to take care of your family’s needs.

3. __It’s ok to attack someone who threatens your family’s honor. 4. __It is alright to lie to keep your friends out of trouble. 5. __Sharing test questions is just a way of helping your friends. 6. __Talking about people behind their backs is just part of the game.

7. __Looking at a friend’s homework without permission is just “borrowing it.” 8. __It is not bad to “get high” once in a while.

9. __Damaging some property is no big deal when you consider that others are beating up people. 10. __Stealing some money is not too serious compared to those who steal a lot of money.

11. __Not working very hard in school is really no big deal when you consider that other people are probably cheating. 12. __Compared to other illegal things people do, taking some things from a store without paying for them is not very serious. 13. __If people are living under bad conditions, they cannot be blamed for behaving aggressively.

14. __If the professor doesn’t discipline cheaters, students should not be blamed for cheating. 15. __If someone is pressured into doing something, they shouldn’t be blamed for it. 16. __People cannot be blamed for misbehaving if their friends pressured them to do it. 17. __A member of a group or team should not be blamed for the trouble the team caused.

18. __A student who only suggests breaking the rules should not be blamed if other students go ahead and do it. 19. __If a group decides together to do something harmful, it is unfair to blame any one member of the group for it. 20. __You can’t blame a person who plays only a small part in the harm caused by a group.

21. __It is ok to tell small lies because they don’t really do any harm. 22. __People don’t mind being teased because it shows interest in them. 23. __Teasing someone does not really hurt them.

24. __Insults don’t really hurt anyone.

25. __If students misbehave in class, it is their teacher’s fault.

26. __If someone leaves something lying around, it’s their own fault if it gets stolen. 27. __People who are mistreated have usually done things to deserve it.

28. __People are not at fault for misbehaving at work if their managers mistreat them. 29. __Some people deserve to be treated like animals.

30. __It is ok to treat badly someone who behaved like a “worm.”

31. __Someone who is obnoxious does not deserve to be treated like a human being. 32. __Some people have to be treated roughly because they lack feelings that can be hurt.

MORAL DISENGAGEMENT IN SCIENCE AND BUSINESS STUDENTS 277