Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:54

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

First-Day Strategies for Millennial Students in

Introductory Accounting Courses: It's All Fun and

Games Until Something Gets Learned

Christian Mastilak

To cite this article: Christian Mastilak (2012) First-Day Strategies for Millennial Students in Introductory Accounting Courses: It's All Fun and Games Until Something Gets Learned, Journal of Education for Business, 87:1, 48-51, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.557102

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.557102

Published online: 21 Nov 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 152

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.557102

First-Day Strategies for Millennial Students

in Introductory Accounting Courses: It’s All Fun

and Games Until Something Gets Learned

Christian Mastilak

Xavier University, Cincinnati, Ohio, USA

Millennial students often possess characteristics at odds with typical lecture-based approaches to introductory accounting courses. The author introduces an approach for reaching millennial students early in introductory accounting courses in ways that fit millennials’ characteristics. This article describes the use of the board game MonopolyRto motivate demand for accounting

information, and the use of LEGOR blocks to demonstrate cost concepts. These approaches

allow students to begin the semester by engaging in experiential and social learning, and to discover for themselves the demand for accounting information and basic cost concepts.

Keywords:accounting, classroom exercises, experimental learning, millennial, social learning

Millennial students (generally those born after 1981) presently entering introductory accounting courses possess characteristics that likely make traditional lecture-based ap-proaches ineffective (for reviews of millennial characteris-tics, see Howe & Strauss, 2000; Oblinger, 2003; Segovia, 2006). They have been socialized to expect instant gratifica-tion, and to emphasize doing rather than knowing. Millenni-als are highly social, preferring face-to-face and online inter-action with peers and instructors to solitary learning. Finally, undergraduate students also tend to have little experience in the business settings that characterize typical introductory accounting instruction.

Introductory accounting courses typically confirm millen-nials’ fears about accounting. These courses are quantitative, require rigorous individual application of logical thinking, and generally have right and wrong answers. And accounting is not obviously relevant to millennials’ social and academic lives. Thus, instructors of introductory accounting courses face significant challenges in capturing students’ attention and interest early in the accounting course.

In this article I present first-day approaches for reaching the millennials early in introductory accounting courses. They are first-day approaches because it may be useful to use the first day of class for these exercises rather than

Correspondence should be addressed to Christian Mastilak, Xavier University, Department of Accountancy, 3800 Victory Parkway, Cincinnati, OH 45207, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

covering the syllabus and overall course requirements. There are several benefits of first-day implementation. First, the first day of class makes an impression that can set the tone for the entire semester. Instructors can immediately show they are interested in their students, and are interested in being interesting. Second, students are often bored by several syllabus presentations on their first day of classes; doing something different makes a class somewhat more memorable. Finally, using the second day of class for syllabus overview allows students more time to get the textbook or to decide whether to drop the class.

Students entering introductory accounting courses have preconceived notions of accounting. According to preclass surveys I have administered, approximately 80% of students either are neutral or disagree with the statement “accounting is fun,” and about 35% are neutral or disagree with the state-ment “accounting is interesting.” To address these attitudes, and to motivate interest, instructors can attempt to broaden students’ conception of accounting by linking it to famil-iar concepts from other setting: performance measurement, reporting, and influencing decisions.

DISCOVERING DEMAND FOR FINANCIAL ACCOUNTING AS SCOREKEEPING: USING

MONOPOLY

To link accounting to familiar concepts, instructors can present accounting as keeping score, and make it clear that

MILLENIAL STUDENTS IN INTRODUCTORY ACCOUNTING 49

scorekeeping matters to everyone, not just the scorekeepers (i.e., the accountants). To make this point, instructors can give students an opportunity to make decisions and to have their score kept. In this exercise, students form small groups and play the board game Monopoly. Monopoly involves investing money into a financial enterprise, developing a strategy, mak-ing investment decisions, paymak-ing expenses, collectmak-ing rev-enues, and competing with other similar enterprises. Thus, the game lends itself very well to financial accounting in-struction (e.g., Albrecht, 1995). Used differently, Monopoly can motivate the discovery of the need for financial account-ing information. That is, the students themselves figure out why accounting is important and useful.

Students are generally familiar with Monopoly, so the game requires little explanation. Instructors can modify the rules slightly to serve pedagogical purposes. For example, requiring teams to purchase a house on their first property ensures the existence of a depreciable asset. Similarly, re-quiring rent to be paid at the beginning of the turn after the one on which a token lands on another team’s property necessitates the recording and settlement of payables and re-ceivables. Instructors can also require teams to write down all their activities, including those that will not eventually be recorded in journal entry form. For example, drawing a “get out of jail free” card would not result in the recording of an asset under current U.S. generally accepted accounting principles, as it has no historical cost. This recorded data can be used later in the semester for the more typical accounting and reporting assignment (e.g., Albrecht, 1995).

At the end of about 10 rounds, instructors can stop the teams and ask them to take an inventory of their assets—that is, to count up their cash, properties, houses and hotels, and other items of value, such as “get out of jail free” cards. In-structors can then ask how well they did, and which team did the best. At this point, students begin to ask questions, such as the following: Should only cash be counted, or prop-erties as well? How much value should be attached to the properties—what was paid, or what they’re thought to be worth to another team who might buy them? What about a “get out of jail free” card, houses, and hotels? Did a team with little cash but many properties do better than a team with more cash but few properties?

These questions and others point to the fact that score-keeping is inherently interesting to those whose score is be-ing kept. They also point to several of the most important issues in financial accounting: Which measures should be used to determine firm success? How should properties be measured: at historical cost, fair value, or some other mea-sure? How are different firms compared to one another, or a firm’s present performance compared to its own performance in a prior period? What does performance in a present period tell about future periods’ performance? How are events that affect multiple periods recorded and measured? And, particu-larly important for introductory financial accounting courses, how are all of a firm’s transactions recorded in a manner that

is logical, complete, efficient, and effective? Thus, on the first day of class, students will have encountered questions that lead them to discover the need for accounting and reporting processes.

This approach not only encourages questions, but it allows for discussion of potential alternative answers in their natural context. In the context of Monopoly, it is not uncommon for players to trade properties, sometimes at values significantly different from their purchase price. For example, players short on cash may pay rent with a property rather than using their remaining cash. The instructor can use this example to begin a discussion about the strengths and weaknesses of historical cost and fair value as valuation methods, or about noncash transactions. Again, students themselves can recognize, in a coherent economic context, why the issues of financial accounting arise and why they matter. Then, later in the course when the material is broken into chapters for pedagogical purposes, each chapter is more easily seen as a part of a whole, and the various discussions of alternative methods make more sense.

This approach fits several key features of the millennial learning style. Students experience for themselves the pro-cess of generating, recording, and evaluating financial results. Students receive instant payoff: Further, by the end of the first class session, students are clearly shown that the instructor expects them to think, participate, and ask and answer ques-tions. The exercise is social and interactive: Groups of 6–12 students are involved in performing the exercise. It is student centered: Students’ decisions drive the activity, and they of-ten lead the class discussion to the relevant accounting topics. And, not least, it is entertaining: Even those students who do not enjoy playing Monopoly are somewhat entertained—at least, more than if they had merely heard a lecture on the ben-efits of providing information to financial statement users.

INTRODUCTORY MANAGERIAL ACCOUNTING: DEMONSTRATING COST

CONCEPTS WITH LEGOs

Despite having different content, introductory managerial accounting courses have many of the same features of intro-ductory financial accounting courses. Both involve logical and quantitative thinking, understanding business contexts, and are not obviously relevant to students’ daily lives. Thus, the managerial accounting instructor faces a similar burden to that of the financial accounting instructor. The approach presented here may help overcome this burden.

Introductory managerial accounting texts (e.g., Garrison, Noreen, & Brewer, 2008) often begin with cost concepts such as product versus period, fixed versus variable, direct versus indirect, sunk, opportunity, and differential. These concepts either imply, or are presented in, manufacturing contexts. However, millennial students seldom have manufacturing experience, and so they may have difficulty comprehending

FIGURE 1 Angle bracket.

these topics. Further, their experiential learning styles are not well suited to imagining manufacturing processes and the related costs. Thus, instructors can demonstrate simple production lines in class to give students a visual reference, experience working in production lines, and a basis for un-derstanding fundamental cost concepts. An example, using LEGO building bricks to produce products, is given here.

The instructor first introduces the product as an angle bracket. The product is made of six LEGO bricks (see Figure 1). The production line consists of two assemblers, a parts mover, and an inspector. Nonproduction personnel include a salesperson and a delivery person. Finally, the instructor serves as the company president. Six volunteers are needed from the class.

Production begins with raw materials (2×2, 2×3, and 2

×4 LEGOR bricks) laid on a table in the front of the

class-room. Assembler 1 attaches two 2 ×2 bricks together and puts the resulting work in process down next to Assembler 2. Assembler 2 attaches a 2×3 brick and three 2×4 bricks. The parts mover moves the finished good to the inspector’s location at a separate table. The inspector’s job is to ensure the finished products are properly made, and to clean the products by wiping them with a paper towel. Because the production process is dirty, a single paper towel can only be used to clean three finished units before a new towel must be used. Although production is ongoing, the salesperson attempts to sell finished angle brackets to customers, represented by those students not participating in the production. The deliv-ery person delivers finished goods to customers as goods are produced. The process needs about 5 min of production for

participating students to learn to do their roles, and observing students to watch the various parts of the process.

Instructors can then ask students to identify the various manufacturing cost concepts involved. Although the produc-tion process is relatively simple, it contains enough elements to demonstrate the basic cost concepts covered early in most managerial accounting textbooks. Product costs are generally obvious to students. Direct materials are the LEGO blocks; direct labor includes the assemblers. Manufacturing over-head costs are several: Indirect labor includes the inspector and the parts mover, indirect materials are represented by the paper towels used for cleaning, utilities can be exemplified by the fact that the classroom’s lights are on, and rent and depreciation can be signified by the table (representing a fac-tory and its equipment). Period costs include the wages of the salesperson and the delivery person as selling expenses, and the president’s salary as an administrative expense.

Cost behavior can also be identified: Variable costs include direct materials, sales commissions, and delivery expenses such as mileage and perhaps maintenance on the (imagined) delivery fleet. Fixed costs include rent; depreciation; wages for the parts mover, inspector, and delivery person; and the president’s salary. The instructor can specify whether assem-blers are paid by the unit or the hour, and discuss whether that affects the behavior of their wages.

Similarly, direct and indirect costs can be identified. Di-rect labor and materials are easily determined by students. Indirect costs such as rent and depreciation are also identified quite easily. Although some may question whether a manu-facturing cost can be considered indirect in a single-product, mass-production setting, instructors may overcome this by treating each individual unit of product as a separate cost ob-ject. The impact of this choice can be maximized by choosing two units that took differing amounts of time to complete. For example, students may drop a unit on the floor, or the instructor may remove one from the assembly line, inspect it or make a comment about it, and then replace it. The ques-tion then arises: Should these units be costed differently just because one took longer in the production line?

Students also generally identify sunk and differential cost concepts. Sunk costs include the cost of the factory and (less obviously) inventory already made. Obvious differen-tial costs in this setting tend to be variable costs—if the firm produces more angle brackets, the amount of direct materials cost will increase. However, expanding the decision set can introduce differential fixed costs as well: What if the firm chooses to quadruple output, and a larger plant is needed? Opportunity costs are more difficult to identify because they result from decisions not made. Asking students to identify an opportunity cost they observed is generally met with useful confusion. The fact that they did not observe an opportunity cost in the same way they observed other costs is instructive about the nature of these costs.

Instructors can also use this example to demonstrate that costs fit into multiple categories at once. The concepts of

MILLENIAL STUDENTS IN INTRODUCTORY ACCOUNTING 51

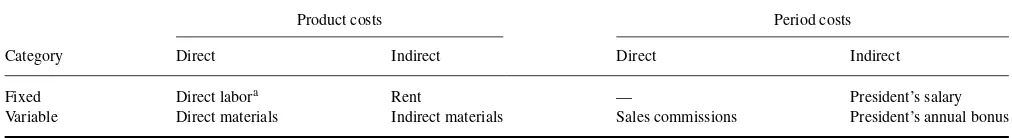

TABLE 1

Presentation of Costs, by Category

Product costs Period costs Category Direct Indirect Direct Indirect Fixed Direct labora Rent — President’s salary Variable Direct materials Indirect materials Sales commissions President’s annual bonus

Note.The cost object is units of production.

aDirect labor not paid on a piece-rate basis may be considered fixed.

product versus period, fixed versus variable, and direct versus indirect allow for eight possible combinations (2×2×2). Instructors can draw two 2 × 2 tables on the board and show that each cost fits into several of these three categories simultaneously (for an example, see Table 1).

As with the Monopoly exercise, the LEGO production line matches millennials’ learning styles. It is experiential: Several students actually produce, sell, or deliver the prod-uct, and the remainder have the opportunity to buy and take delivery of it. Students generally need no more than a def-inition of a cost concept (e.g., variable cost) to identify the costs that fit that type. That is, they discover the concepts by watching the production process unfold in front of them. It reduces required lecturing and gives students a sense of ownership for the course content. It is social and interactive: Students interact with each other on the production line and with the instructor. It is student centered: Students’ produc-tion, sales and delivery activities drives the exercise. And it is entertaining: Students generally enjoy working with LEGOs, trying out clever sales pitches, and competing with each other to produce more products. An outgoing instructor can also establish rapport by playing the role of company president in an engaging manner, gently harassing assemblers and in-spectors for production errors, goading the salesperson to sell more, and effusively deferring to customers’ every demand.

CONCLUSION

Faced with the millennial milieu, instructors have essentially two options. They may bemoan the differences between ac-tual and ideal students, and plow ahead with preferred meth-ods of teaching. After all, accounting is a field that requires serious people willing to do serious work. If students

can-not or will can-not do what is required to keep up, it is better to weed them out sooner rather than later. Another option is to accept millennials how they are and adapt teaching styles to the audience. After all, instructors do need to raise up a new crop of accountants from among the students who actually exist, not from among ideal students who do not exist (and probably never did). It is frustrating and possibly ineffective to continually attempt to teach in a way that is not suited to students.

The present article presents approaches for reaching the millennials where they are to begin bringing them to where instructors want them to be. Students generally find the ap-proaches instructive and enjoyable, and recommend their continued use. The approaches presented here are merely ex-amples. It is not essential that instructors reproduce all the details exactly, and surely there are many ways to improve on them. What is important is to identify who the incoming students are and how they learn, and to develop and imple-ment pedagogical techniques that leverage students’ learning styles.

REFERENCES

Albrecht, W. D. (1995). A financial accounting and investment simulation game.Issues in Accounting Education,10(1), 127–141.

Garrison, R., Noreen, E., & Brewer, P. (2008).Managerial accounting(12th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Howe, N., & Strauss, W. (2000).Millennials rising: The next great genera-tion. New York, NY: Vintage.

Oblinger, D. (2003). Boomers, gen-xers, and millennials: Understanding the “new students”.EduCAUSE Review,38(4), 36–47.

Segovia, J. (2006). Understanding generation NeXt and creating ac-tive learning in accounting courses.Business Education Forum,61(2), 17–20.