S

UPPLY

-

SIDE AND

D

EMAND

-

SIDE

E

XPLANATIONS OF

D

ECLINING

A

PPRENTICE

T

RAINING

R

ATES

:

A C

RITICAL

O

VERVIEW

PHILLIPTONER*

O

ver the last decade numerous academic, industry and government studies have suggested that Australia has experienced a sustained decline in apprentice training rates and that this is contributing to shortages in core vocational occupations. This article redresses significant deficiencies in these studies by providing new data on long-run apprentice training rates by broad occupational group. This data confirms the existence of a sustained break in the long-run apprentice training rate from the early 1990s to the present. The article also provides an overview and critical assessment of the key explanations of this decline and policy recommendations to redress the decline. It is argued that these explanations may be classified into supply-side and demand-side approaches. The article concludes firstly, that, in general, demand-side explanations provide a superior understanding of declining training rates. Secondly, given the potential importance of trade skill shortages additional research is required both to quantify the effect of the various demand-side contributions to reduced training rates and to reorient current policies to better address these demand-side causes.INTRODUCTION1

Over the last decade it has been argued that there has been a significant reduction in the overall apprentice training rate. The training rate is the ratio of apprentices in-training to employed tradespersons. Apprentices in-training is the total stock of employed apprentices at a point in time. It is the conceptual equivalent of total employed tradespersons. Concerns have been expressed at the implications of this decline for the long-run supply of skilled trades for production and main-tenance activity. This issue of declining apprentice training rates is not isolated to Australia, but has been a feature of many countries which have apprenticeship systems including Great Britain and the US. It has also been the subject of considerable international research (Ball 1988; Rainbird 1991; Gospel 1993, 1994; Gann and Senker 1998; Ryan 2000). This study seeks to contribute to this literature firstly by redressing deficiencies in previous Australian estimates of apprentice training rates. These deficiencies precluded definitive conclusions regarding long run trends in training rates. The new data confirm that in the

1990s and early 2000s a marked trend decline occurred in employer investment in apprentice training in the principal trade occupations.

Secondly, the article provides a critical overview of the key explanations and policy recommendations regarding trends in apprentice training rates in Australia. Whilst there is a large literature on this topic, it is highly fragmented with many articles focusing on only one or two potential causes of the decline, or this decline constitutes only a small part of the subject of the articles or reports. The present study is the first attempt to provide a systematic, if brief, overview of the key arguments regarding the decline.

Thirdly, the study argues that the numerous explanations offered for the decline in apprentice training rates may be usefully divided into two opposing approaches to labour market and economic analysis. These competing theories may be characterised as supply-side and demand-side approaches. The task of categorising and outlining the respective arguments is important, as it is often the case that in the literature these arguments are juxtaposed indiscriminately which leads to a lack of conceptual clarity. By classifying the arguments into the two broad approaches the distinct policy implications of the arguments and approaches can be more clearly appreciated.

The study concludes that, in general, demand-side explanations provide a superior understanding of declining training rates. Secondly, given the potential importance of trade skill shortages, additional research is required both to quantify the effect of the various demand-side contributions to reduced training rates and to reorient current policies to better address these demand-side causes.

SUPPLY AND DEMAND-SIDE APPROACHES

These two approaches have a long history in economic theory and broader social sciences. The two approaches have distinct analyses of the bases of production, exchange and competition. Applied to the issue of apprenticeship training, the supply-side approach emphasises human-capital type arguments such as excessive apprentice wages (reducing the demand for apprentices); inflexibilities on the supply-side of the training system (restrictive curriculum, delivery modes, and regulatory complexity) and declining apprentice applicant quality, to explain employers’ declining investment in apprentice training. The supply-side approach regards the level of investment in apprenticeship as the outcome solely of rational decision-making based on cost-benefit analyses on the part of individual employers and apprentices. Adjustment of prices and quantities are assumed to ensure that any under-supply will be temporary.

training in particular, across different economic entities.3There are marked differ-ences in training propensity and intensity between public and private sectors, between full-time and causal employees, and across firm sizes and industries. Shifts in the relative distribution of economic entities with these characteristics will shift the aggregate propensity and intensity of training. Over the last two decades a number of changes have occurred which are argued to be adverse for apprentice training rates. These changes include: corporatisation and privatisation of public sector entities; reductions in average firm size; increased competition; growth of casual and part-time employment and growth of outsourcing and labour hire. Secondly, the demand-side approach argues for the ‘cultural specificity of many skill-supply mechanisms and their location within broader systems of production, industrial relations, inter-firm networks, industrial capital, corporate governance and politics’ (Keep & Mayhew 1999 p. 5).4Given the emphasis on structural and institutional factors the demand-side approach rejects the a priori assumption that the economy will so adjust in the long run as to equilibrate supply and demand, either at an aggregate level or in specific activities, such as ensuring an adequate supply of skilled trades.

These differing broad interpretations have significantly different policy implications for the Vocational Education and Training (VET) system. The supply-side approach recommends measures to ensure the market for training more accurately approximates a competitive model through further deregulation of labour markets and training systems; breaking the historical connection between vocational training and employment; increasing firm-specific training; and shifting the cost burden of training from firms to individuals. The policy responses from the demand-side perspective involve a broad range of specific measures targeted to offset specific structural impediments to lifting apprentice training rates.

DATA ON APPRENTICESHIP TRAINING RATES

Numerous Australian studies have argued that a sustained decline in apprentice-ship training rates and/or intake occurred over the last decade (Marshman 1996, 1998; OTFE 1998; Smith 1998, 1999; Toner 1998, 2000a, 2000b, AiG 2000; BVET 2001). The view of these studies is that, following the 1991–92 recession, there was a sustained break in the long-run trend apprentice training rate.

However, there was uncertainty about these claims due to data limitations which restricted analyses to the period from 1986 onwards. This was due to the intro-duction by the Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS) in 1986 of a new occupational classification (ASCO First Edition), which was largely incommensurable with the previous classification system, the Classification and Classified List (CCLO). The CCLO had been used from the 1960s. Consequently, it was difficult to calculate long-run training rates by broad occupational trade group as comparable data on pre-1986 trades employment were not readily available. (Trades employment is, of course, the denominator in the calculation of the training rate. This data is derived from the ABS Labour Force Australia survey. The numerator is apprentices in-training derived from historical DEET/COSTAC data and

460 THE JOURNAL OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS December 2003

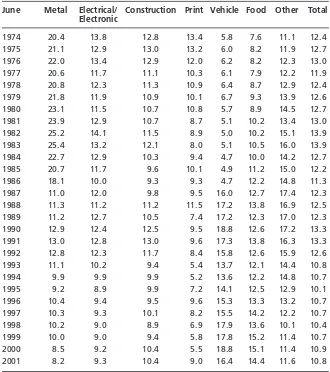

Table 1 Apprentice training rates, Australia, 1974–2001

June Metal Electrical/ Construction Print Vehicle Food Other Total Electronic

1974 20.4 13.8 12.8 13.4 5.8 7.6 11.1 12.4

1975 21.1 12.9 13.0 13.2 6.0 8.2 11.9 12.7

1976 22.0 13.4 12.9 12.0 6.2 8.2 12.3 13.0

1977 20.6 11.7 11.1 10.3 6.1 7.9 12.2 11.9

1978 20.8 12.3 11.3 10.9 6.4 8.7 12.9 12.4

1979 21.8 11.9 10.9 10.1 6.7 9.3 13.9 12.6

1980 23.1 11.5 10.7 10.8 5.7 8.9 14.5 12.7

1981 23.9 12.9 10.7 8.7 5.1 10.2 13.4 13.0

1982 25.2 14.1 11.5 8.9 5.0 10.2 15.1 13.9

1983 25.4 13.2 12.1 8.0 5.1 10.5 16.0 13.9

1984 22.7 12.9 10.3 9.4 4.7 10.0 14.2 12.7

1985 20.7 11.7 9.6 10.1 4.9 11.2 15.0 12.2

1986 18.1 10.0 9.3 9.3 4.7 12.2 14.8 11.3

1987 11.0 12.0 9.8 9.5 16.0 12.7 17.4 12.3

1988 11.3 11.2 11.2 11.5 17.2 13.8 16.9 12.5

1989 11.2 12.7 10.5 7.4 17.2 12.3 17.0 12.3

1990 12.9 12.4 12.5 9.5 18.8 12.6 17.2 13.3

1991 13.0 12.8 13.0 9.6 17.3 13.8 16.3 13.3

1992 12.8 12.3 11.7 8.4 15.8 12.6 15.9 12.6

1993 11.1 10.2 9.4 5.4 13.7 12.1 14.4 10.8

1994 9.9 9.9 9.9 5.2 13.6 12.2 14.8 10.7

1995 9.2 8.9 9.9 7.2 14.1 12.5 12.9 10.1

1996 10.4 9.4 9.5 9.6 15.3 13.3 13.2 10.7

1997 10.3 9.3 10.1 8.2 15.5 14.2 12.2 10.7

1998 10.2 9.0 8.9 6.9 17.9 13.6 10.1 10.4

1999 10.0 9.0 9.4 5.8 17.8 15.2 11.4 10.7

2000 8.5 9.2 10.4 5.5 18.8 15.1 11.4 10.9

2001 8.2 9.3 10.4 9.0 16.4 14.4 11.6 10.8

Source:Data for trades employment was derived from Labour Force Australia, Historical Summary 1966–1984 (ABS Cat. No. 6204.0) and Labour Force Australia(ABS 6203.0, various issues). Conversion of pre-1986 CCLO occupational classification to ASCO (First edition) is based on the ABS concordance (ABS Cat. No. 2182.0). Data on apprentices in-training was derived from COSTAC/DEET Apprenticeship Statistics for data from 1974 to 1993, from 1994–1998 NCVER (1998) Apprentices and Trainees in Australia 1985–1997and NCVER unpublished data 1998-2001 inclusive. The NCVER data from 1999 to 2001 are based on ASCO (Second Edition) Major Group 4 New Apprentices in-training, Australia (December 2001 estimates).

more recent National Centre for Vocational Education Research [NCVER] data). Given the relatively short span of the time series used in these studies, from 1986 onwards, it could have been the case that low training rates evident over the last decade were not unusual if a longer-run perspective had been used. This doubt was reinforced by the fact that the period of the mid-to-late 1980s experienced the highest level of apprentice commencements since records were first published from the 1960s. In other words, the training rates of the 1990s could simply have appeared low in comparison with the high rates of the latter 1980s without this reflecting necessarily any structural break with previous longer-run trends.

This study overcomes this problem by providing data on training rates from 1974 to 2001, and therefore incorporates the effect of several business cycles.5 The problem of incommensurable occupational classification systems was over-come by using an ABS concordance, which permitted the construction of a consistent time series of Trade occupations (see notes to Table 1). Aside from the total apprentice training rate, the selected trade occupations for which a consistent time series over this period could be constructed were Electrical/ Electronics; Construction, Printing; Food and Other.

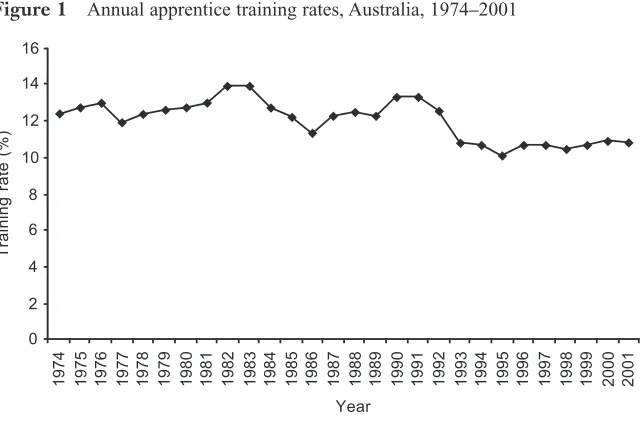

This data confirms the existence of a sustained break in the long-run apprentice training rate following the severe recession in the early 1990s to the present (Table 1 and Fig. 1). Over the 19 years between 1974 and 1992 the training rate averaged 12.7 per cent. From 1993 to 2001 the total annual average training rate was 10.6 per cent. This represents a decline of 16.3 per cent. The change between the two periods 1974–1992 and 1993–2001 is highly statistically significant.6

Trends across occupational groups

Although there was a reduction in the aggregate apprentice training rate after 1992 there was also considerable variation in training rates across the

DECLININGAPPRENTICETRAINING RATES 461

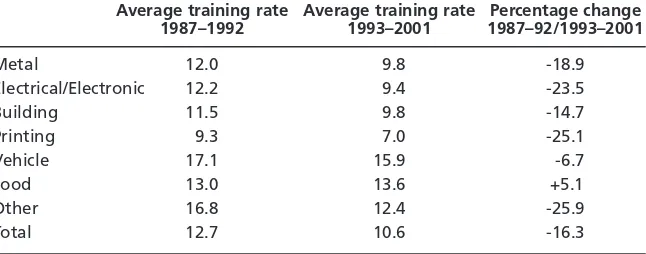

major occupational groups (Table 2). The Metal training rate declined by nearly 19 per cent after 1993 compared to the latter 1980s.7Electrical and Electronic trades training rate declined by close to a quarter after 1993. The training rate for Construction fell by close to 15 per cent, even though the industry recorded a significant increase in trades employment over the 1990s (Table 4) and sustained a record level of real construction output over much of the 1990s and early 2000s (Toner 2000a). Vehicle had a modest decline of around one-third the total fall in training rates. Food experienced an increase of just over 5 per cent during the last decade. The training rate for Printing was volatile over the last decade given the relatively small numbers of apprentices and tradespersons employed, though the overall rate fell by 25 per cent. The Other category also experienced a large slump in the training rate from 1993. (This is due in large part to the decline in hairdressing apprentices, which comprise the bulk of the Other category.)

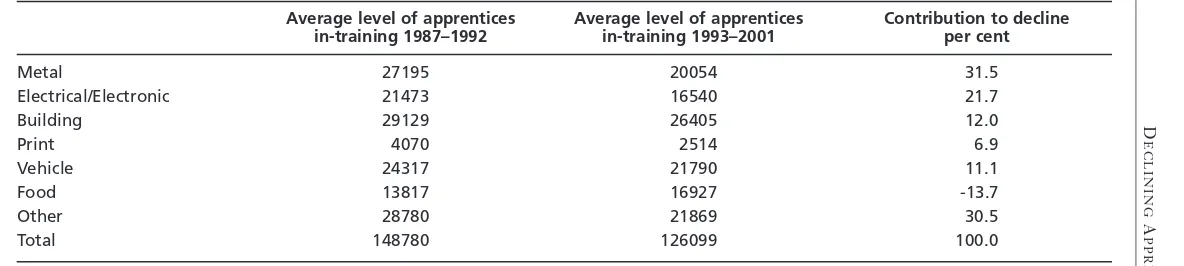

An examination was also made of the contribution of the various occupational groups to the total reduction in the annual average level of apprentices in-training (Table 3). Metal and Electrical contributed 31.5 per cent and 21.7 per cent respectively to the total decline in the annual average level of apprentices in-training over the two periods. Construction accounted for 9.3 per cent of the total decline.

These three broad occupational groups combined represented 50 per cent of total apprentices in-training over 1993–2001, but contributed 65 per cent of the decline in annual average level of apprentices in-training over the period. The other principal contributor to the decline was Other.

As will be described below, the very large variation in the performance of the apprentice occupations in terms of training rates and numbers in-training over the period has important implications for assessing the validity of competing explanations of declining training rates. It is suggested that these findings are more consistent with the demand-side approach, which focuses on industry specific structural and institutional factors stimulating or impeding apprentice training.

462 THE JOURNAL OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS December 2003

Table 2 Apprentice training rates, Australia, 1987–1992 and 1993–2001

Average training rate Average training rate Percentage change 1987–1992 1993–2001 1987–92/1993–2001

Metal 12.0 9.8 -18.9

Electrical/Electronic 12.2 9.4 -23.5

Building 11.5 9.8 -14.7

Printing 9.3 7.0 -25.1

Vehicle 17.1 15.9 -6.7

Food 13.0 13.6 +5.1

Other 16.8 12.4 -25.9

Total 12.7 10.6 -16.3

D

ECLINING

A

PPRENTICE

T

RAINING

R

A

TES

463

Table 3 Contribution to the decline in the total level of apprentices in-training

Average level of apprentices Average level of apprentices Contribution to decline in-training 1987–1992 in-training 1993–2001 per cent

Metal 27195 20054 31.5

Electrical/Electronic 21473 16540 21.7

Building 29129 26405 12.0

Print 4070 2514 6.9

Vehicle 24317 21790 11.1

Food 13817 16927 -13.7

Other 28780 21869 30.5

Total 148780 126099 100.0

464

T

HE

J

OURNAL

OF

I

NDUSTRIAL

R

ELA

TIONS

December

2003

Table 4 Trades employment and percent change in trades employment and apprentices in-training, Australia

Average trades Average trades Change in average Change in average employment employment trades employment apprentices in-training

1987–1992 1993–2001 1987–1992 to 1993–2001 (%) 1987–1992 to 1993–2001 (%)

Metal 226833 206100 -9.1 -26.3

Electrical 175567 176833 0.7 -23.0

Building 254950 270322 6.0 -9.3

Print 43850 36622 -16.5 -38.2

Vehicle 142783 137456 -3.7 -10.4

Food 106900 124011 16.0 22.5

Other 218217 209111 -4.2 -24.0

Total 1169100 1160456 -0.7 -15.2

IMPLICATIONS OF THE DECLINE IN TRAINING RATES

There are numerous implications flowing from reduced training rates for the trades. Only two are briefly mentioned here: the effect on skill shortages and technical innovation.

Training rates and skill shortages

The most obvious implication of the decline in training rates is that the reduction in the supply of new tradespersons from domestic training sources is contributing to current skill shortages in trades occupations. The principal sources of qualified tradespersons are the domestic apprenticeship system and skilled migration, with the former accounting for around 80–85 per cent of the flow of trades skills over recent years.8 Numerous surveys and reports from employer associations, government and academics have identified persistent skills shortages, notably in metal, electrical and construction trades (AiG 1999; DETYA 2000a,b, 2002; Construction Training Australia 2001; Worland & Doughney 2001). A combination of reduced apprentice intake over the 1990s, continuing high wastage rates from the trades (that is, trades employees electing to work in other occupations) and economic growth over the last decade has resulted in significant trade skill shortages. The economic implications of these shortages are severe. ‘Skill shortages, if extensive and sustained, can limit investment and growth opportunities, give rise to upward pressure on earnings and, thereby, dampen the pace of economic and jobs growth and make it more difficult to reduce unemployment’ (DEETYA 1999a, p. 2). The National Skills Shortage List produced by the Department of Employment, Workplace Relations and Small Business which is used for a range of purposes including the targeting of occupations for the Skilled Migration Program, identifies shortages in metal, electrical and construction trades (DEWRSB 2002).

Higher vocational skills and innovation

Higher-level vocational skills are central to the development of innovation, quality product design and production processes and higher productivity.9In turn, these skills are crucial to success in world trade in innovation-intensive manu-factures. These are products, which ‘require a well-qualified workforce capable of rapid adjustment in the work process and continual product innovation’ (Finegold & Soskice 1988, p. 21).

A number of studies have identified the links between national differences in VET performance and national differences in innovation and productivity (Prais 1995; Anderton & Schultz 1999). Some of the specific linkages between higher level VET skills and innovation and productivity include lower rework and defect rates; improved maintenance permitting higher machinery utilisation rates; improved quality assurance; flatter management structures and more efficient operation of flexible specialisation equipment which permits closer tolerances of work and improved quality, product customisation and reduced cycle times (Toner et al. 2002).

This strong nexus between the product-market strategies of firms and the quality and quantity of vocational skills available to them raises a major potential concern. The current failure to adequately reproduce trade skills essential in the production and maintenance of sophisticated manufactures in Australia, and especially in areas such as metal and electrical trades, could lead managers to develop alternative strategies such as informal upgrading of employees into positions previously held by people who had undergone appropriate training. This ‘making do’ with lesser-skilled staff could shift firms’ product-market strategies towards less sophisticated and less innovation-intensive products and alter production techniques towards a more innovation-intensive use of less skilled labour.

SUPPLY-SIDE APPROACHES TO THE EXPLANATION OF DECLINING APPRENTICE TRAINING RATES

The supply-side approach is associated with neoclassical economic theory. The quantum of training undertaken by employers and employees is the outcome of the calculus of the discounted time rate of return on such investments (Becker 1964). Strictly speaking, in a perfectly competitive economy, investment in training will occur up to the point where the marginal cost and marginal revenue of such training are in equilibrium. From such a view, wage costs and the efficiency in the supply of training, entailing a range of factors such as price, flexibility in delivery and relevance of training to the specific needs of the firm, are of central importance. The following outlines the key arguments in the supply-side approach to explaining the decline in apprentice training rates and intake.

Excessive apprentice wages

Sweet (1995, p. 103) has argued that ‘the demand for wage based contractual training arrangements [apprenticeships] has been declining since the early 1980s, and has continued to decline in to the mid 1990s’. The principal reason for the ‘failure to expand wage based contractual training arrangements in Australia lies with inadequate wage structures’ (Sweet 1995, p. 103). The most important inadequacy is the small relativity between apprentice and tradespersons’ wages.

As a percentage of the adult rate, apprentice wages appear to differ little from those applying in classifications to which contractual training is not attached. As a consequence employers therefore provide minimal training (Sweet 1995, p. 106).

However, to this author’s knowledge there is no evidence in the supply-side literature that there has been a compression of apprentice and tradesperson wages over the 1990s which could have led to a substitution of the latter for the former. One economic analysis of apprenticeship training in Australia concluded there is ‘No evidence to suggest that wages for apprentices relative to tradespersons are generally too high’ (Dandie 1996, p. 23).

in apprentice training (Dockery et al. 1996; DEETYA 1997). This study actually confirmed the Keynesian finding of other research that, change in the level of a firm’s output is the dominant explanatory variable in an employer’s decision to hire apprentices (Merrilees 1983). The ‘major single influence on the number of apprentices employed is the expected level of sales or activity. The demand for apprentices is thus derived directly from the demand for the firm’s product’ (DEETYA 1997, p. 31).10In addition to demand, the study found an important non-economic factor in firms’ decisions to engage apprentices: ‘firms appear strongly influenced in their decision to hire apprentices by what may be termed social or community influences, such as a perceived obligation to provide training for young people and a sense of obligation to the trade’ (DEETYA 1997, p. 49; Smith 1998, pp. 134–5).

Using data from the 1970s to the early 1990s the study also estimated the elasticity of employment with respect to apprentice wages. It was found that the variety of subsidies directed at increasing ‘marginal’ employment of apprentices, that is, only paid for additional apprentices, had no effect on total employment. However, other subsidies paid to all apprentices, regardless of ‘additionality’, were found to have increased the stock of apprentices. Taking these latter subsidies ‘as a wage reduction equivalent . . . implies an elasticity in the order of –0.5 to –0.7 ’ (DEETYA 1997, p. 85). The elasticity is significantly less than unity. A 10 per cent reduction in apprentice wages would increase the stock of apprentices by between 5 and 7 per cent. To increase the current level of apprentice intake by 15 per cent, so that the current training rate would equal the long-run rate prior to 1993, would require apprentice wages to fall by between 24 and 34 per cent. However, the study found ‘very little support among employers for the notion of a reduction in apprentice wages’ (DEETYA 1997, p. 45). This was because such a fall ‘would be accompanied by a decline in the average quality of the apprentice intake. Second, many [employer] respondents stated that the apprentice wage should not be reduced as it would be inequitable to do so’ (DEETYA 1997, p. 48).

In summary, there is no evidence in the supply-side literature of a compression in apprentice/tradespersons wage relativity over the last decade that could account for decline in apprentice training rates. Nevertheless, on the basis of the positive historical experience with the introduction of wage subsidies (see Endnote 5) and the econometric evidence cited above, it is possible that an increase in the level of current financial incentives for the employment of apprentices could have a marginally beneficial effect in redressing the declining training rate. In theory, a reduction in apprentice wages could have the ‘same’ effect as a subsidy though, in practice, concerns have been expressed at the effect of such a reduction on the quality of applicants. There are also anecdotal reports that the low level of apprentice wages relative to other employment opportunities for young people acts as a disincentive for more able potential apprenticeship applicants.

This review finds the supply-side explanation of falling training rates based on a compression of apprentice/tradesperson wages is not well founded, though a

case can be made for using adjustments to the level of apprentice wages through a subsidy as a partial solution to declining training rates.

Inadequate financial incentives to employ apprentices

The current system of financial incentives offered to employers of apprentices is inadequate in its response to identified skills shortages and, arguably, biased against the employment of apprentices in favour of trainees. The following sets out some of the problems.

Commonwealth financial incentives are paid to employers of apprentices and trainees upon commencement of the person in employment and upon completion of their training. The same level of payment for the commencement and completion of New Apprentices applies to both apprentices and trainees undertaking Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF) III and IV courses. These payments do not recognise the fact that some AQF III or IV traineeships can be completed in much less time (even one year) compared to the four year term of a metal, electrical or construction apprenticeship. As such, the payments do not recognise the much greater investment of time and effort on the part of the apprentice employer. In theory, an employer could get four cycles of commencement and completion payments for trainees in the same time it takes an employer of an apprentice to get one cycle. The argument is not that the incentive programme has led to a significant substitution of apprentices for trainees, the latter only account for around 10 per cent of New Apprentices classified to ASCO major Group 4 Trades, rather, it is that the incentive pro-gramme does not adequately recognise the greater investment of apprentice employers in training (Toner 2000b).

Secondly, related to the argument above, the incentive programme fails to adequately target scarce training funds on strategic skill shortages. In particular it has been found that traineeships are producing an inordinate share of lower skilled occupations compared to their distribution within the total workforce. Over one-third of the annual intake of trainees in 2001 consisted of Labourers and Elementary Clerical occupations, and another third were Intermediate Clerical and Production workers (Toner 2002b). Between 1995 and 2000 the total number of New Apprentices increased by 100 per cent from 136 000 to 276 00 but the total number of apprentices in-training was largely static (NCVER 2001, p. 66).11

There are now well established precedents for the use of strategic targeting for employer incentives in vocational training. Only minor adjustments to the programme guidelines would be required to significantly improve the effectiveness of these schemes.

Flexibility in the training market

The apprenticeship system is also argued to be in decline due to ‘inflexibility’ in the system, such as mandated course content and time frames for completion of training; lack of choice over training delivery methods; lack of competition in the provision of training; and inadequate focus on the specific training needs of firms.

Reform of industry training should, in the first instance, be about letting markets work and making sure that the right kind of training is delivered. Making training more flexible and responsive to what the market wants will in turn make the industry more efficient (ACIL 1998, p. 18).

This line of analysis also leads to a view that the historical foundation of the system, that is, the link between structured training and employment, needs to be broken or significantly altered. There are two aspects to this line of thought. Firstly, training could become institutionally based, whereby an individual can study for a range of vocational occupations at private and public colleges without contemporaneous employment in the field of study (ACIL 1998, p. 1; AiG 1999, p. xii). Secondly, broader labour market deregulation is required, especially direct workplace negotiation between employees and employers as to the type, delivery, quantum and cost burden of training.

[The] labour market will only become truly efficient and flexible and encourage meaningful training arrangements between employers and employees when genuine, freely negotiated contracts between employees and employers are possible (ACIL 1998, p. 7).

Over the last decade there has been a comprehensive implementation of policies designed to introduce a market for training and remove ‘inflexibilities’ in the apprenticeship system. These measures include, for example, the removal of age restrictions for apprenticeships, removing restrictions for certain types of work to be undertaken only by apprentices or tradespersons, opening up of trade-type training to traineeships, introduction of competency based training in place of ‘time served’ and making public funds for off the job apprenticeship training subject to competition between the public and private sectors (ANTA 1998a; Webster et al.2001; NCVER 2001, p. 57).

These extensive changes have not restrained the decline in apprentice training rates.12 In addition, some of the recommendations for increasing flexibility in apprenticeship arrangements may undermine the traditional economic rationale for employer investment in apprentice training. For example, a significant shortening in the length of the apprenticeship, rather than the traditional time-served indenture could, paradoxically, reduce employer invest-ment in training. This is because the duration of the traditional apprenticeship, usually four years,

can be viewed not as a calculated period necessary to acquire trade training but as a set period which enables an employer to gain a return on the low productivity of the trainee during the early part of the apprenticeship. In other words, the apprenticeship can be seen as being artificially lengthened to prevent other employers from ‘poaching’ the newly trained worker until such time as the individual is regarded as having paid his initial employer for his training (Curtain 1987, p. 18).

A reduction in the period of training before the apprentice receives their trade qualification will, ceteris paribus, reduce the time in which the employer has to recoup their investment.

Inadequate firm specific training

Inadequate orientation of the apprenticeship system towards the provision of firm specific training is also offered as an explanation of declining apprentice training. A shift in the balance of training towards firm-specific, as opposed to general or industry-specific training, is advocated as a means of increasing employer demand for VET in general, and apprenticeships in particular (AiG 1999, p. xv). The content and delivery methods of training should be tied more directly to the needs of particular employers. The case for increased firm-specific training is a subset of the more general ‘flexibility’ argument, though its importance deserves separate consideration.

This explanation of declining apprenticeships may be criticised on a number of grounds. Firstly, like the argument regarding compression of wage relativities and demand for increased flexibility in training markets, the stress on firm specific training does not explain the marked variance in trends in training rates and levels of employment across the broad apprentice occupations. As described earlier some large apprentice occupations such as Food have experienced significant growth in employment and training rates, whilst Vehicle declined by only one third the aggregate fall in training rates over the last two decades. As a general explanation then, the argument regarding inadequate provision of firm specific training is not convincing. Further, advocates of this argument need to explain why this factor should only have begun to dramatically affect aggregate training rates over the last decade.

Secondly, flexibility needs to be an important feature of any training system, though it also needs to be recognised that an undue emphasis on firm-specific training contradicts a key economic rationale for the provision of public funds for vocational training. Commonwealth and state expenditure on the VET system is ‘well over $1 billion per year’ (NCVER 2001, p. 27). A key rationale for the provision of public funds for VET is that there are significant economic benefits to society as a whole in providing workers with industry specific or general skills (Becker 1964). General skills are the broad range of vocational skills that are necessary for undertaking work either for a particular employer, for the industry, or even the economy as a whole. Individual employers, it is argued, will not invest in industry or general skills, as they will not necessarily reap the returns from such investments as workers can freely contract with other employers. Another way of expressing this is that there is market failure in the private provision of general, as opposed to firm-specific, training. The benefits to society from the investment of public funds in general skills are an improve-ment in the quality and productivity of the workforce and an increase in the efficiency of the labour market by improving the intra-firm, intra-industry and inter-industry mobility of labour. This mobility of labour is essential for the economy to adjust in the face of structural change and gain the benefits of an efficient allocation of labour resources.

market could be lost if training becomes overly firm-specific (Buchanan & Callus 1992). This mobile and ‘occupational’ labour market is due to a number of factors, notably the small size of Australian firms, which has precluded the development in the private sector of extensive ‘internal’ labour markets (Curtain 1987). The comparatively small size of the Australian market has also prevented the creation of an intensive division of labour, resulting in smaller firms requiring more broadly skilled trades labour. In turn, this has been influential in the maintenance of identifiable trade occupations (Gospel 1994).

Further, the argument for more firm-specific training is based solely on the interests of the employer and ignores the interests of the apprentice. By accepting a ‘training wage’ a person undergoing vocational training is also investing considerable time and forgone earnings in the acquisition of marketable skills. It is only equitable that individuals investing in such training receive an appropriate balance between firm-specific and industry/general skills, given that they can expect to have multiple employers over their working life.13

Declining quality of apprentice applicants

A number of surveys of employers report that the quality of applicants for apprenticeships is declining (Marshman 1996, p. 24; ACIRRT 2002, p. 35; DETYA 2002, p. 18). These surveys suggest that an important ‘factor identified as having a major effect on apprentice recruitment was a supply-side factor, namely the quality of recruits available, suggesting that many employers would increase the number of apprentices employed if higher quality candidates were available’ (DEETYA 1997, p. 31). It is also undoubtedly the case that many trade fields, such as metals and engineering do have an ‘image problem’ and ‘no doubt the size and quality of the apprentice applicant pool could always be improved’ (Hall & Buchanan 2000, p. 8). The key policy recommendation from this line of analysis is to improve the marketing of apprenticeships (DETYA 2002).

Sweet (1990, p. 233) notes that, whilst school retention rates to year 12 have increased markedly, there has not been a corresponding increase in the proportion of Year 12 apprenticeship commencements. This implies that more academically able students are remaining in the education system rather than electing to enter an apprenticeship. Smith (1998, p. ix) cites a number of studies indicating that apprentices and trainees have ‘inadequate language, literacy and general reasoning skills’. These inadequacies create significant learning problems, especially with the move away from face-to-face teaching, and increased use of computer based and distance learning. The studies cited by Smith, however, do not demonstrate whether apprentices’ difficulty with off-the-job formal training is a recent development reflecting declining intake quality or a long term problem with apprentice intake.

On the other hand, research by the federal department responsible for the administration of the apprenticeship system found that although there may be shortages of quality applicants in particular regions or particular trades, overall, employers reported seven suitable applicants for each vacancy. Group Training Companies reported three suitable applicants for each vacancy. Smaller firms have

more of a problem than larger firms in attracting suitable applicants (DEETYA 1998, p. 5).

Overall, it appears highly probable that, due to a broad range of factors, such as the expansion of tertiary education and associated rapid growth of professional and paraprofessional employment and the ‘image problem’ of some traditional trades, there has been some reduction in the quality of applicants. In turn, this has led employers to reduce their apprentice intake. However, this appears to be only a minor factor in explaining the decline in aggregate training rates.

Demand-side explanations

In contrast to the supply-side interpretation the demand-side approach empha-sises structural shifts in the economy and institutional changes that have reduced employer investment in training in general and apprenticeship training in partic-ular. These changes include a set of self-reinforcing factors, such as greatly increased competition leading to increased down-sizing and contracting out; growth of labour hire companies; increase in the proportion of small firms and privatisation and corporatisation of public services. Some of these major structural changes are summarised below.

Reduced demand for trade skills?

It is crucial to note that the decline in training rates and absolute level of appren-tices does not reflect a proportionate reduction in demand in the economy for trade skills. It would be expected that a trend decline in the stock of employed tradespersons would be accompanied by an equiproportional decline in the flow of new entrants into the trade.

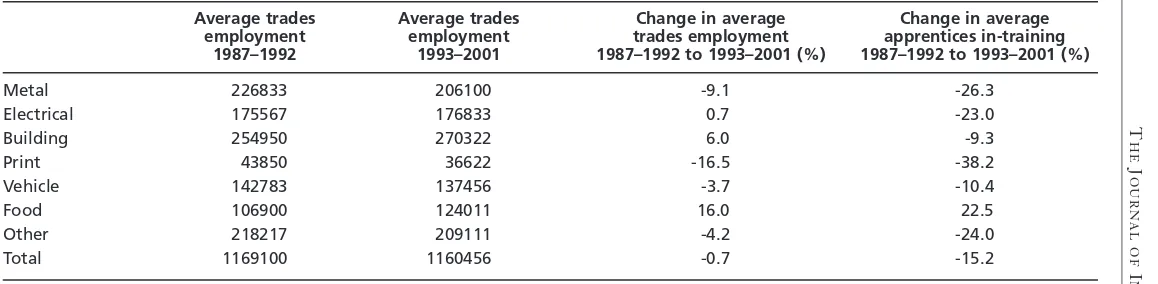

This is not the case. The average total trades employment between 1987–92 and 1993–2001 fell by under 1 per cent, but the total number of apprentices in-training fell by over 15 per cent (Table 4, column 4). The fall in the level of Metal and Vehicle apprentices in-training was nearly three times the decline in the number of Metal and Vehicle tradespersons employed. The number of Electrical apprentices in-training declined by nearly one-quarter but the employ-ment of Electrical trades increased by nearly 1 per cent. The average number of building trades declined by 9.3 per cent over the period but employment of building tradespersons increased by 6 per cent.

Corporatisation and privatisation of government activities

industry and engaged a large proportion of their apprentices on the basis that they would be employed only up to the completion of their training and then be released to the industry. In the mid-1980s NSW Government Business Enterprises (GBEs) alone employed 21 per cent of all electrical apprentices; 10 per cent of building apprentices and 9 per cent of metal apprentices. By the late 1990s the GBEs share had been reduced by 80 per cent. It is estimated that the withdrawal of the public sector accounted for around one-third of the decline in apprentice intake over the last ten years (Toner 1998). Similar large falls in public sector apprentice intake occurred throughout Australia (NCVER 2001, p. 75). Crucially, there was no compensating increase in private sector apprentice employment in the metal, electrical and construction occupations.

Increased competition

Marshman (1996) and (ANTA 1997, p. 12; ACIRRT 2002; Toner & Wixted 2002) have argued that factors such as tariff reduction and globalisation have increased the intensity of competition. Increased competition is especially evident in the trade-exposed areas of the economy, such as manufacturing, where the effects of international competition and globalisation have greatly intensified. Manufacturing is the principal employer of metal trades and to a lesser extent of electrical trades. One measure of this intensification of competition is that in 1989–90 the manufacturing trade deficit was 12.3 per cent of total manufacturing turnover; by 1999–2000 it had increased to 19.4 per cent (Toner & Wixted 2002, p. 33). Another indicator of increased competition is that the profit margins and rate of return on manufacturing assets have not recovered over the decade from rates recorded in the deep recession of the early 1990s (ABS, Cat. No. 8140.0, various issues).

This section highlights four interrelated responses to increased competition. These responses are the intensification of work, introduction of ‘lean production’ systems, growth of labour-hire and increased outsourcing of functions.

Littler (2003, p. 9) has shown that, internationally, corporate downsizing and ‘delayering’ (removal of management layers) over the 1990s has led to an intensification of work, as measured by increased working hours and increased responsibilities of the remaining workforce. The recent ACIRRT (2002, p. 33–38) study of Victorian manufacturers found that as a result of reduced employment the intensity of work in the remaining workforce had increased to the point where there was simply no surplus labour capacity to disengage experienced tradespersons from production to train and mentor apprentices. This lack of surplus labour capacity not only adversely affected the quality of training for existing apprentices but also made firms reluctant to engage apprentices. Employers also reported that intensified competition and tighter margins had reduced their financial capacity to invest in the level of training that they would like.

Increased competition has resulted in unpredictable and shorter contract cycles. This has introduced uncertainty about the future, which makes employers reluctant to enter into the 3-4 year contract involved in the employment of

apprentices. Apart from not having the capacity to carry the additional cost, they do not want to have to put them off if contracts do not eventuate (Marshman 1996, p. 12). Although not explained by Marshman and others, the move to shorter contract cycles reflects the introduction of ‘lean production’ production techniques aimed at reducing a firm’s cost and risk (Harrison 1997). A key element in lean production is the Just in Time (JIT) production method. Under JIT, sub-contractors enter into ‘open ended contracts’ with principals, in which there is no guarantee of a fixed quantity of work over a given period. JIT offers principals considerable competitive advantage through cost savings, especially reduced inventory holdings. It is also a method for shifting the risk of market fluctuations from the purchaser of a good or a service onto the supplier, as the purchaser is not locked into a fixed long term contract. However, JIT production methods make it difficult to provide the continuity of work required for an apprenticeship and they are also a factor in the growth of labour hire. Nearly 50 per cent of employers identified meeting peak production demands as the main reason for the use of labour hire (ANTA 1998b, p. 26). Other research on the drivers of training has found that ‘lean production . . . is associated with the reduction of training activities’ (Smith et al.2002, p. 8).

Many of the industries that were traditionally the principal employers of apprentices, such as manufacturing, construction, and electricity gas and water, are also disproportionately outsourcing production, maintenance and other services (Hall & Bretherton 2000). The significance of this outsourcing of trade-based work to labour hire companies is that ‘labour hire firms primarily rely upon the pool of skilled people in the labour market, and are not large providers of formalised training of the type involved in the traditional apprenticeship’ (ANTA 1998b, p. 1). The growth of labour hire, in turn, reflects increased competition and the need to reduce costs. Related to this is development of ‘lean production’ systems, based on the ‘downsizing’ of firms with a smaller ‘core’ full-time workforce and the growth of a ‘peripheral’ workforce comprised of labour hire employees and other part time or casual employees (Harrison 1997).

This is a complex issue however, as recent research has found that many labour hire firms recognise that their long run existence relies on the availability of a pool of trained workers, and therefore are prepared to assist the training effort, though the clients of these firms ‘were often reluctant, if not downright hostile about having contract apprentices on their site’ (ACIRRT 2002, p. 51). Although this hostility is not explained in the report, it presumably derives from the fact that the labour hire contractee only wants fully qualified and experienced persons working for them and does not see it as their role to ‘train’ labour hire workers.

had increased to 23 per cent (ACIRRT 2002, p. 44). In the US the largest single private sector employer is the labour-hire firm Manpower Inc., with over 500 000 people on its books (Crouch et al.1999, p. 16).

The growth of the labour hire industry, contracting-out and downsizing in the private and public sectors is, at least in the medium term, mutually self-reinforcing in that reducing firms’ full-time core employment increases the demand for contract staff. On the supply-side ‘downsizing and outsourcing means there has been an increase in the number of skilled workers available to labour hire firms’ (ANTA 1998b, p. 46).

Reduced firm size

In many of the industries, such as construction and electricity gas and water, that were traditionally large employers of metal, construction and electrical apprentices, there has been a marked reduction in the average firm size. The reduction in average firm size is due in part to privatisation and corporatisation, downsizing and the outsourcing of work to smaller specialists. In the construction industry for example, there has been a very substantial increase in the share of employment and output from small specialist subcontractors. Over the seven years to 1996–97 the share of total employment in firms employing fewer than five persons increased from 42.6 to 68.6 per cent. All of the employment growth over the period occurred in businesses with fewer than five employees. Employment in larger firms actually declined, with the level of employment in firms with 20 or more employees falling by more than 50 per cent (Toner 2000a).

The significance in the growth of small firms and the reduction in the average size of firms is that both the propensity to train and the intensity of that training increases with firm size. With respect to training intensity, in the private sector in 1996, firms with more than 100 employees spent 3.4 times more on structured training than firms with fewer than 20 employees. With respect to training propensity, the proportion of firms providing structured training is 6.6 times greater in larger firms than smaller firms (ABS 6353.0, Table 4.1). Other research confirms the link between firm size and in-house formal training (Wooden 1996). On the specific issue of the relation between firm size and apprentice training,

It is well known that large firms are more likely to provide formal training, and this extends to apprenticeship training. There is also a positive correlation between firm size and the absolute number of apprentices employed (Dockery et al.1996, p. 14).

Smaller specialist firms can also find it difficult to provide the range of work experience necessary to create a well-rounded tradesperson. Such increases in specialisation are a factor in the reduced demand for apprentices (Construction Training Australia 1999; Toner 2000a).

Growth of casual and part-time employment

Significant growth of ‘non-standard’ working conditions, such as part-time work, casualisation and multiple job holding have also restrained employer investment

in training. In 1982, 13.3 per cent of the workforce were casual employees; this increased to 26.4 per cent in 1999 (Campbell 2000). The significance of these changes in employment status for training is that, controlling for a wide range of personal, educational, demographic, occupational and industry variables, casual employees are much less likely to have undertaken employer-provided training compared to full time employees (VandenHeuvel & Wooden 1999, pp. 27, 43–45).

A consequence of these long-term changes in labour market status of employees is that ‘the growth of non-standard work implies that there may be a serious training deficit emerging with respect to comprehensive trade and voca-tional training and more generalist training’ (Hall & Bretherton 1999, p. 1).

Transformation of the industrial relations system

Many of the changes outlined above, such as those related to the intensification of work, growth of labour-hire and increased outsourcing of functions have been facilitated by reduced union influence in workplaces, the broader deregulation of the labour market and retreat from a centralised wage fixing and industrial relations system. In turn, these changes to the industrial relation system have also contributed to the decline in apprentice training rates.

It has been found that the creation and maintenance of a VET system producing ‘industry’ specific skills, like traditional apprenticeships in Australia and Western Europe, depends on a set of interlocking institutional arrangements. These institutional arrangements include ‘collective wage bargaining systems’ and their associated strong business and union organisations. These arrangements ‘are necessary to sustain cooperation in the provision of specific skills’ (Estevez-Abe et al. 2001, p. 182). Industry specific skills in Australia and Western Europe are acquired through a combination of employment and on and off the job training, have a duration of training of around 3–4 years, and have well-defined standards for entry and training, and in almost all cases result in well-defined occupations which have considerable intra-industry mobility. Key features of these industry specific skills, notably those relating to wages, content of training and duration of training and prescribed off the job training are the subject of negotiation and agreement between peak business organisations and unions. These agreements result in common standards being applied within an industry to minimum wage levels and conditions of employment and consensus on the work content and career paths of tradespersons.14In Australia almost all aspects of these training provisions were prescribed in industrial awards: ‘training and skills formation has been historically coupled to the industrial relations system in Australia through the award system’ (Roan & Lafferty 2001, p. 7). In many cases these awards prescribed certain classes of work to be undertaken by apprentices.

In a prescient statement in 1993 Curtain argued that:

. . . existing forms of regulated training are likely to decline substantially within the next five years as a result of a shift in the centre of gravity of industrial relations away from highly centralised forms of determining wage and conditions to agreements that are negotiated closer to the workplace.

In Australia over the latter 1990s a diminished role for industry based awards, and declining union density in many of the traditional industries that employed apprentices has reduced the capacity of unions to enforce award provisions. There is also some evidence that employers are shifting training more towards meeting firm-specific requirements. One large survey of manufacturing and construction companies found that ‘All respondents had a strong desire to have [Training Package] standards arrangements that suit companies as the primary focus, not necessarily industries’ (AiG 1999, p. 79). In some circumstances such a shift to more firm specific training can result in workers being trained only ‘to acquire the minimum competencies to get the job done’ (ACIRRT 2002, p. 38). This is a shift away from the more comprehensive skills and knowledge such as those embodied in an apprenticeship. It would seem that training is increasingly linked to the immediate production and the worker’s specified range of current duties.

The industrial relations changes that occurred over the 1990s would appear to be adverse to the maintenance of the apprenticeship system, by undermining the broader institutional supports for this system. This applies especially to occupations such as metals, electrical and construction apprenticeships, as these are predominantly in industries such as manufacturing, utilities and construction where union influence was significant, but has waned. The changes have also reduced the incentive for multi-employer coordination of the vocational training system by facilitating more firm-specific training.

DEMAND-SIDE RESPONSES TO DECLINING APPRENTICE TRAINING RATES

A number of policy responses are suggested from the demand-side approach. These responses are intended to remedy specific structural impediments to the employment of more apprentices. There is not the space to provide a detailed account. A fuller account can be found in ACIRRT (2002) and Toner (2003). The principal responses are briefly described below.

• Leveraging government expenditures to lift training. Some state governments are responding to the problems arising from large-scale public sector with-drawal from direct employment of apprentices by requiring private sector contractors on substantial public works projects, including Public-Private Partnerships, to commit a proportion of project costs to training, including apprentice training (NSW Government 2000).

• Improvements in the quantity and quality of training offered by Group Training Companies (GTCs) are also recommended (ACIRRT 1997; Toner & Wixted 2002). GTCs redress a number of the structural impediments to the employment of apprentices, such as reduced firm size and reduced contract cycles, identified in this article. They do this by engaging in a form of labour hire whereby the apprentice is employed by the GTC and hired out to employers over varying periods of time. Given the increased importance of GTCs as employers of apprentices (their share of total apprentices increased from 2 to over 20 per cent during the last two decades), a number of measures have been suggested to ensure that all GTCs operate at a uniform high level of service quality.

• Given reduced employer investment in training, one recent study argued for the re-introduction of a training levy, though one which learns from the errors in the original Training Guarantee Levy (TGL), that operated during the 1990s (Hall et al. 2002). The funds would be intended to lift the quantity and quality of training. There are many current examples of training levies or other forms of compulsory vocational and professional training current in Australia.

• In addition, other industry policy measures directed at improving the innovation-intensity and competitiveness of firms and increasing the level of import-replacement and share of world exports may lift some of the financial constraints on increasing investment in apprentices. Innovation-intensive firms and industries also have a much higher propensity to invest in training and have higher intensity of training as measured, for example, by training expenditures per employee (Toner et al.2002, p. 10).

CONCLUSION

The study concludes first, that there was a large and statistically significant decline in the aggregate apprentice training rate over the last decade. Between 1987–1992 and 1993–2001 the aggregate apprentice training rate fell by 16.3 per cent. The Metal training rate declined by nearly 19 per cent after 1993 compared to the latter 1980s. Electrical and Electronic trades had declined by close to a quarter after 1993. The training rate for Construction fell by close to 15 per cent, even though the industry recorded a significant increase in trades employment over the 1990s. Some trades such as Food experienced a large increase the number of apprentices in-training and a modest rise in the training rate.

Second, the decline is contributing to the deficit in the supply of skilled trades and the resulting shortages can have severe economic impacts. Such shortages could constrain the scope for product and process innovation in industries that intensively used trade skills.

(Recent changes to Commonwealth incentives have redressed some of these latter concerns).

Fourth, the study also found that it is most unlikely that the decline in training rates can be accounted for by a decline in the demand for trade skills. Some trades, such as construction and electrical and electronics had modest growth in employ-ment over the last decade, though the training rates for apprentices declined by 9 per cent and 25 per cent respectively. For other trades such as Metal the decline in the training rate was three times the percentage decline in employed Metal tradespersons.

Fifth, given the diverse range of factors identified as contributing to the decline an equally broad range of solutions is required to redress the problem.

Finally, this study should be regarded as largely preliminary. Further research is urgently required in two areas. A quantification of the demand-side factors identified in this report would assist in establishing a ranking of the principal causes of declining training rates and priorities for remedial action. To date only the effect of the decline in public sector employment of apprentices has been quantified. It contributes around one-third of the decline in training rates (Toner 1998). There are undoubtedly data availability problems in this exercise, though it is an important public policy issue and should be given priority. Secondly, this report is largely silent on the marked decline in training rates in the Other category. Training rates in the Other category declined by 25 per cent over the period and contributed 30 per cent of the decline in the level of apprentices in-training. This is believed to be largely due to the decline in hairdressing apprenticeships. It is unlikely that most of the factors identified as causing the decline in metal, electrical and construction industries apply to the Personal Services industry. Further research is required to explain these trends.

The direction of policies over the last decade to promote apprenticeships has had an almost singular supply-side approach (NCVER 2001, p. 24–28). This study suggests that this direction will not provide an adequate solution to the decline in domestic investment in trade training.

NOTES

1. An earlier version of this paper was given as a conference paper at the 11th Annual VET/TAFE Research Conference, Brisbane, 2002 and, as Declining Apprentice Training Rates: Causes, Implications and Solutions, at Dusseldorp Skills Forum, Sydney. This paper benefited greatly from comments by Dr Evan Jones, Sydney University, Dr Richard Curtain, Curtain Consulting, and Julius Roe, AMWU.

2. For a clear and accessible exposition of the differences between demand and supply side approaches to economic theory see McCombie and Thirlwall (1994). Toner (1999) may also be consulted. In the field of the economics of training the most thorough-going use of the demand side approach is the so-called ‘Oxford School’ represented by writers such as Finegold and Soskice (1989), Keep and Mayhew (1999), Finegold (1999) and Hall and Soskice (2001). 3. Training propensity is the proportion of firms in a given category which engage in structured

training. Training intensity is a measure of training effort per employee, measured by dollars of expenditure or hours of structured training provided to each employee in a given time period. 4. An important example of the institutional foundations of VET systems is the work of

Estevez-Abe et al. (2001).

5. The period from 1974 onwards was chosen due to the introduction of the first national employer subsidy scheme for apprentices in that year. This caused a break in the trend

training rate. The subsidy ‘had an immediate effect on the number of opportunities being offered by employers to apprentices . . . [as] apprentice numbers jumped by over 12 per cent between 1973 and 1974’ NCVER 2001, p. 13).

6. The test involved an OLS regression over the full period 1974 to 2001 with dummy variables of 0 and 1 for the period 1974–1992 and 1993–2001 respectively. The change in the intercept is highly statistically significant at the 95 per cent confidence level (t-statistic –9.28). The regression results are as follows:

It is important to note that similar results are achieved when the ABS data on apprentices in-training (derived from Transition From Education to Work, Cat. No. 6227.0), is used in place of the administrative data derived from COSTAC/DEET and NCVER. There is a high correlation coefficient of 0.83 between the ABS and administrative data sets, indicating the two closely track each other (Toner 2003, p. 36).

7. The period from 1987 onwards was chosen due to changes in the classification of apprentices as described in the explanatory notes to Table 1. These changes apply especially to Metal and Vehicle Trades.

8. Toner (2002a, p. 49) found that between 1995–96 and 1999–2000, net migration contributed the equivalent of 17 per cent of total apprenticeship completions in Australia. This is an upper estimate of the actual contribution of migrants to the qualified trades labour force, as not all migrants declaring a trade occupation would work in this occupation, once settled in Australia. Earlier studies found that there was considerable volatility over the longer term in the ratio of net trades migration to domestic apprenticeship completions (NCVER 1999, p. 12).

9. Toner et al.(2002) provide a comprehensive literature review of the links between VET skills and innovation.

10. The finding that the level of output is the dominant variable in the explanation of apprentice intake would seem to contradict our argument that changes in the structure of the economy are largely responsible for the sustained decline in training rates from 1993 to the present. The econometric studies which identified the dominance of the demand variable were based on data from the mid-1960s to the early 1990s (for example DEETYA 1997, p. 94). This is a period in which the apprentice training rate was relatively constant (Table 1) and prior to those structural changes which, it is argued, occurred over the last decade. In addition, it is implausible to argue that changes in the level of output explain the decline in apprentice training rates over the last decade. Table 4 shows that between 1987–1992 and 1993–2001 average employment in Trades across Australia declined by just 0.7 per cent, but employment of apprentices declined by 15.2 per cent. Some trades such as building and electrical experi-enced increased employment of trades over the period, but large reductions occurred in their respective training rates.

11. Following a review of the New Apprenticeships financial incentives in 2002, a number of improvements were made to the system, which removed other biases in favour of trainees over apprentices. Under the Rural and Regional New Apprenticeships Incentive scheme an additional payment is made to employers engaging persons in ‘an occupation identified as being in skill shortage’ (DEST 2002, p. 1). The list of occupations targeted include many traditional trade occupations. Unfortunately, these payments are only available to employers in non-metropolitan areas. In NSW for example, around 75 per cent of all apprentices are located in metropolitan areas (BVET 2001, p. 37). In addition, a new programme to promote training for innovation-intensive industries, the Innovation Incentive, will operate from July 2003. The new incentive is certainly a positive development, but the program fails to include a broad range of manufacturing industries, such as metals and engineering, which are not only highly innovation intensive, but is the principal employer of those metal trades and apprentices, which are in particular shortage. The programme also does not include construction industry trades. In summary, the two employer incentive programmes that have strategic targets fail to ‘hit’ a number of key shortages in the vocational labour market.

480 THE JOURNAL OF INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS December 2003

Coefficients Standard Error t-stat P-value

Intercept 12.68421 0.124584 101.8123 0.000000