Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Prerequisite Change and Its Effect on Intermediate

Accounting Performance

Jiunn Huang , John O'shaughnessy & Robin Wagner

To cite this article: Jiunn Huang , John O'shaughnessy & Robin Wagner (2005) Prerequisite Change and Its Effect on Intermediate Accounting Performance, Journal of Education for Business, 80:5, 283-288, DOI: 10.3200/JOEB.80.5.283-288

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.3200/JOEB.80.5.283-288

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 20

View related articles

or many years, educators and prac-titioners have been concerned that accounting education has not been preparing students adequately for the business environment. Such concerns have traditionally centered on the nega-tive effect resulting from the prolifera-tion of authoritative promulgaprolifera-tions (Baxter, 1953; Wilson, 1979; Zeff, 1979). In addition, changes in the polit-ical, social, and legal environment of the business world have forced recognition of additional topics in the accounting curriculum. These topics include ethics, accounting history, globalization, and international accounting standards.

In 1984, the Executive Committee of the American Accounting Association organized the Bedford Committee to address possible changes in accounting education. The Bedford Committee observed that

[t]he reorientation of accounting educa-tion from the preparaeduca-tion of financial statements to an expanded economic/ financial information development and distribution function will involve restruc-turing and reorienting university account-ing education material. (American Acc-ounting Association, Committee on the Future Structure, Content, and Scope of Accounting Education [the Bedford Committee], 1986)

Consistent with the Bedford Commit-tee Report, the Executive CommitCommit-tee of the American Accounting Association

formed the Accounting Education Change Commission (AECC) in 1989. The AECC was charged with the task of changing accounting education so that students would have improved capabili-ties for successful professional careers (Mueller & Simmons, 1989).

In 1992, the AECC issued a position statement that dealt primarily with the first course in an accounting program.

The statement reiterated the importance of accounting as “an information devel-opment and communication function that supports economic decision-making” (AECC, 1992, p. 249). The AECC rec-ognized that many of the students taking this first accounting course were not accounting majors and that it was impor-tant that the course emphasize “the rele-vance of accounting information to accounting decision-making (use) as well as its source (preparation)” (p. 250). The first accounting course should have some elements of the decision maker’s orientation.

Following the recommendations of the AECC and after a critical self-assessment, the curriculum designers at San Francisco State University (SFSU) changed their introductory financial accounting course presenta-tion and implemented other curricular revisions, effective Fall 1996. Since then, the introductory financial accounting course has been presented from the financial statement “user’s” perspective—a change from the tradi-tional approach of a “preparer’s” orien-tation. A financial analysis approach has been emphasized, with a concur-rent de-emphasis of the accounting cycle. The designers initiated this change to give both accounting and nonaccounting students a better busi-ness perspective.

Prerequisite Change and Its Effect

on Intermediate Accounting

Performance

JIUNN HUANG JOHN O’SHAUGHNESSY

ROBIN WAGNER

San Francisco State University San Francisco, California

F

ABSTRACT. As of Fall 1996, San

Francisco State University changed its introductory financial accounting course to focus on a “user’s” perspec-tive, de-emphasizing the accounting cycle. Anticipating that these changes could impair subsequent performance, the Department of Accounting insti-tuted a new prerequisite for intermedi-ate accounting: Students would have to pass either a pretest or a 1-unit course focusing on the accounting cycle. In this study, the authors ana-lyzed the effectiveness of the screen-ing/remedial system and concurrent effects on performance. They found that students who passed the pretest or accounting cycle class received signif-icantly better grades in intermediate accounting than did students who failed either the pretest or the 1-unit course and than students who did not take either the pretest or the 1-unit class. This finding implies that this form of pretest/remedial course screen would be effective in similar universi-ties in which a large percentage of accounting majors have taken intro-ductory financial accounting at a com-munity college.

In anticipation that the de-emphasis of the accounting cycle and other “pre-parer-oriented” issues in the introduc-tory accounting course could have neg-ative effects on accounting students’ performance in the subsequent first intermediate accounting course, the Department of Accounting established an additional prerequisite: To enter the intermediate accounting level, students would have to pass either a pretest or a one-unit remedial course focusing on the accounting cycle. These additions were to serve as mechanisms for assessing the level of student prepara-tion for intermediate accounting coursework and would allow for reme-dial study of the accounting cycle.

In this study, our purpose was to deter-mine the effects resulting from the imple-mentation of the “user’s” approach and concurrent changes in the prerequisites on the first intermediate accounting course. We investigated three aspects of these changes: (a) whether the pretest/ accounting cycle system, as implemented in Fall 1996 as a prerequisite to the first intermediate accounting course, serves as a good screening process or predictor of performance in that course; (b) whether the new approach affects student perfor-mance in introductory financial account-ing; and (c) whether the new approach affects student performance in the first intermediate accounting course.

The San Francisco State University Program

At SFSU, the introductory financial accounting class, Principles of Financial Accounting (ACCT 100), is a required course for all business majors, including those interested in accounting. (See Appendix for information on details of the bachelor’s degree in business administration with a concentration [major] in accounting.) After taking a managerial accounting class (ACCT 101), accounting majors then take Inter-mediate Accounting I (ACCT 301), an upper division course, as the first course in the major. Until Fall 1996, ACCT 100 was taught from a “preparer’s” perspec-tive, and the prerequisites for ACCT 301 were passing ACCT 100 and ACCT 101, or their equivalents, with a grade of at least C–.

In response to the recommendations of the AECC and subsequent to a criti-cal self-assessment, the following revi-sions to the curriculum were imple-mented and became effective in Fall 1996:

1. The designers modified the intro-ductory financial accounting course by removing most of the bookkeeping ele-ments, de-emphasizing debits and credits and the accounting cycle, and emphasiz-ing the decision-makemphasiz-ing process and group work. Accounting majors were directed to pertinent material for their self-study.

2. A new textbook was selected based on its emphasis on the use of accounting information rather than on information preparation. The text took a financial statement user’s approach, relegating accounting cycle issues to an appendix. In the textbook’s preface, Ingram and Baldwin (1996, p. iii) made the follow-ing statement: “The authors illustrate accounting not as a set of technical pro-cedures to be memorized but as a way of understanding businesses and a means for evaluating them.”

3. A one-unit course, ACCT 102—the Accounting Cycle—was developed to cover the material de-emphasized in the revised financial accounting course. The course focuses on the maintenance of accounting records and preparation of financial statements using traditional bookkeeping procedure. Students are required to attend classes, complete a practice set, and pass a final examina-tion to pass the class. The grading is on a credit/no-credit basis. This course became a prerequisite for the first inter-mediate accounting course but could be taken concurrently.

In Summer 1998, the Department of Accounting developed a pretest, admin-istered by the University Testing Center, that consists of 30 multiple-choice questions covering double-entry book-keeping and the accounting cycle. To meet the prerequisite for the first inter-mediate accounting course, the student can attain a passing score (70%) on the pretest in lieu of passing the accounting cycle course.

Effective Fall 1998, and continuing to the present, the prerequisite for the first intermediate accounting course was for-mally changed to passing the pretest or passing the one-unit accounting cycle course. In addition, the accounting cycle course could no longer be taken concur-rently with the first intermediate account-ing course. However, instructors have the discretion to waive these prerequisites.

Data Collection

We collected student grades1 in the

first intermediate accounting course (ACCT 301) and the accounting cycle (ACCT 102), as well as pretest scores for the period from Spring 1997 to Spring 2002. For those students who took ACCT 301 multiple times, we used only the first grade obtained in ACCT 301 in this study. For those students who took the pretest or ACCT 102 multiple times, we used only the last score. Stu-dents who received a grade in ACCT 301 other than “A” through “F” were nated from the sample. We also elimi-nated students who took the pretest or ACCT 102 after2 receiving a grade in

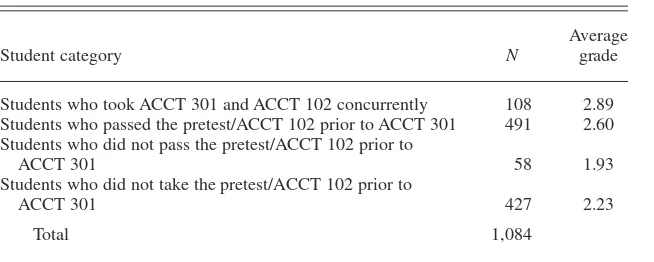

ACCT 301. The population consisted of 1,084 data points, as we show in Table 1.

In addition, we collected grades for the introductory financial accounting

TABLE 1. Breakdown of ACCT 301 Grades and Pretest/ACCT 102 Status

Average

Student category N grade

Students who took ACCT 301 and ACCT 102 concurrently 108 2.89 Students who passed the pretest/ACCT 102 prior to ACCT 301 491 2.60 Students who did not pass the pretest/ACCT 102 prior to

ACCT 301 58 1.93

Students who did not take the pretest/ACCT 102 prior to

ACCT 301 427 2.23

Total 1,084

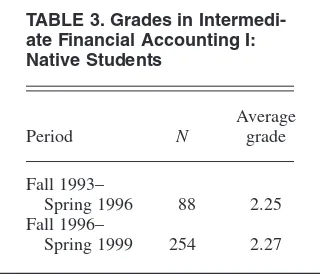

course, ACCT 100, for all students for Fall 1993 through Spring 1996 (i.e., prior to the curriculum change) and for Fall 1996 through Spring 1999 (i.e., subse-quent to the curriculum change). The population consisted of 1,401 data points (see Table 2). In addition, we collected the grades for those ACCT 301 students who took the introductory financial accounting course at SFSU (hereafter, “native” students). This population con-sisted of 342 data points (see Table 3).

Data Analysis

Pretest/ACCT 102 Effectiveness as Screen for Intermediate Accounting

To test whether results on the pretest/accounting cycle course were effective screens or predictors of perfor-mance in intermediate accounting, we performed two tests. First, we compared the average grade in ACCT 301 received by students who took but did not pass either the pretest or ACCT 1023and the

average grade in ACCT 301 for students who took and passed either the pretest or ACCT 102. We formulated the fol-lowing null hypothesis:

NH1: The average grade in ACCT 301 for students who took but did not pass either the pretest or ACCT 102 will not differ significantly from the average grade in ACCT 301 for students who passed either the pretest or ACCT 102.

We used the following alternative hypothesis:

AH1: The average grade in ACCT 301 for students who took but did not pass either the pretest or ACCT 102 will be significantly lower than the average grade on ACCT 301 for students who passed either the pretest or ACCT 102.

We performed a one-sided ttest with the following results:t(66) = 3.908, crit-ical t = 1.668, p = .001. The null hypothesis of no difference was reject-ed. Our results indicated that students who passed either the pretest or ACCT 102 significantly outperformed students who took but failed to pass either the pretest or ACCT 102.

Next, we compared the average grade in ACCT 301 for students who did not take either the pretest or ACCT 1024and

the average grade in ACCT 301 for stu-dents who took and passed either the pretest or ACCT 102. We formulated the following null hypothesis:

NH2: The average grade in ACCT 301 for students who did not take either the pretest or ACCT 102 will not differ significantly from the average grade in ACCT 301 for students who passed either the pretest or ACCT 102.

We used the following alternative hypothesis:

AH2: The average grade in ACCT 301 for students who did not take either the pretest or ACCT 102 will be signifi-cantly lower than the average grade in ACCT 301 for students who passed either the pretest or ACCT 102.

We performed a one-sided ttest with the following results: t(851) = 4.928, critical t = 1.647, p = 5.01E-07. The null hypothesis of no difference was rejected. Our results indicated that stu-dents who passed either the pretest or ACCT 102 significantly outperformed students who did not take either the pretest or ACCT 102.

The results of this study are not par-ticularly surprising because virtually any screening system based on academic abilities is likely to identify a group of

students who will outperform another group of students who were not screened or failed the screening. However, the results are still relevant in that they indi-cate that performance on the pretest and ACCT 102 is useful in predicting perfor-mance in the first intermediate account-ing course. Our results also imply that passing the pretest/ACCT 102 is a better predictor than one that depends on stu-dents’ passing ACCT 100 and ACCT 101 with at least a grade of “C–” (i.e., the prior prerequisite predictor in effect before Fall 1996). This suggests that implementation of such a predictor would be useful for universities with large percentages of accounting majors who have taken their introductory finan-cial accounting course at community colleges, as is the case with SFSU. In addition, our results can be interpreted to mean that the material covered in ACCT 102 and the self-study that students per-formed in anticipation of the pretest enhanced performance in the first inter-mediate accounting course.

Effect of Curriculum Change on Performance in Introductory Financial Accounting

A second objective of our study was to test whether the change in the content of the introductory financial accounting course had an effect on students’ perfor-mance in that course.

We compared the average grades of students who took ACCT 100 prior to Fall 1996 and the average grades of stu-dents who took ACCT 100 during or subsequent to Fall 1996.

We used the following null hypothesis: NH3: The average grade of students who took ACCT 100 before Fall 1996 will not differ significantly from the average grade of students who took ACCT 100 during or subsequent to Fall 1996.

Our alternative hypothesis was as fol-lows:

AH3: The average grade of students who took ACCT 100 before Fall 1996 will be significantly lower than the aver-age grade of students who took ACCT 100 during or subsequent to Fall 1996.

We performed a two-sided ttest with TABLE 2. ACCT 100 Grade

Average

Student category N grade

All students

Fall 1993–Spring 1996 634 1.80

Fall 1996–Spring 1999 767 1.73

ACCT 301 students

Prior to Fall 1996 88 2.42

During or subsequent to Fall 1996 254 2.94

the following results: t(1385) = 1.261, critical t = 1.962, p =.208. The null hypothesis of no difference could not be rejected. Our results imply that perfor-mance, as measured by grades in the introductory financial accounting, were not affected by the change in the accounting curriculum. This does not, of course, indicate that the change was of no value to the students. The results are more likely the effect of instructors’ maintaining a level of rigor despite the de-emphasis on double-entry bookkeep-ing, the debits and credits of which are among the most difficult topics for introductory accounting students. The value, if any, of the change in the per-spective is more likely to surface in sub-sequent business courses.

Effect on Performance in Intermediate Accounting

Our third objective in this study was to analyze the effect of the changes on native accounting student performance, as measured in grades, in both the finan-cial and first intermediate accounting courses. We performed two tests.

First, we compared the average grade in ACCT 100 for (native) accounting majors who took ACCT 100 before Fall 1996 and the corresponding average grade of (native) accounting majors who took ACCT 100 during or subse-quent to Fall 1996.

Our fourth null hypothesis was as fol-lows:

NH4: The average grade in ACCT 100 of (native) accounting majors who took ACCT 100 prior to Fall 1996 will not differ significantly from the average grade of (native) accounting majors who took ACCT 100 during or subse-quent to Fall 1996.

Our alternative hypothesis was as fol-lows:

AH4: The average grade in ACCT 100 of (native) accounting majors who took ACCT 100 before Fall 1996 will differ significantly from the average grade in ACCT 100 of (native) account-ing majors who took ACCT 100 duraccount-ing or subsequent to Fall 1996.

We obtained the following results from a two-sided ttest:t(170) = 5.575,

critical t = 1.974,p = 9.57E-08. These results indicate that there was a statisti-cally significant difference between the grades of the two groups. Accounting majors who took ACCT 100 subsequent to the curriculum change received sig-nificantly higher grades in ACCT 100 than did accounting majors who took ACCT 100 before the curriculum changes. Two interpretations present themselves. The results may imply that “better” students are attracted to the accounting major as a result of their experience in ACCT 100. This interpre-tation is consistent with the prior find-ing that there is no significant difference between average grades in ACCT 100 before and subsequent to the curriculum change. The alternative explanation is that there is a correlation between the grade in ACCT 100 and passing the pretest/ACCT 102. If so, then this result is a function of that correlation because it is based on at least a partial screening of ACCT 301 students.

Next, we compared the average grade in ACCT 301 for students who took ACCT 100 before Fall 1996 and the average grade of students who took ACCT 100 during or subsequent to Fall 1996 (see Table 3). We formulated the following null hypothesis:

NH5: The average grade in ACCT 301 for students who took ACCT 100 before Fall 1996 will not differ signifi-cantly from the average grade in ACCT 301 for students who took ACCT 100 during or subsequent to Fall 1996.

Our alternative hypothesis was as fol-lows:

AH5: The average grade in ACCT 301 for students who took ACCT 100 before Fall 1996 will be significantly higher than the average grade in ACCT 301 for students who took ACCT 100 during or subsequent to Fall 1996.

A one-sided ttest led us to the follow-ing results:t(183) = –0.1167, critical t = 1.653, p = .4536. The results indicate that student performance in ACCT 301 was not affected by the curriculum change in the introductory financial accounting class and concurrent imple-mentation of the pretest/accounting cycle prerequisite to ACCT 301. The results indicate that a change to a “user’s”

approach in teaching financial account-ing did not negatively affect performance in Intermediate Accounting I. This result is inconsistent with the possible interpre-tation that “better” students are drawn to major in accounting as a result of a “user’s” perspective in introductory financial accounting. It is, however, con-sistent with the results of Bernardi and Bean (1999), who concluded that there was no difference in performance in intermediate accounting as a result of using a “user’s” approach as opposed to a “preparer’s” approach. This finding also implies that a university need not offer separate introductory financial accounting classes for accounting majors.

Conclusions

In this study, we analyzed the effec-tiveness of the screening/remedial sys-tem by comparing the performance in the first intermediate accounting course of those students who passed the pretest/accounting cycle screen with the performance of those who either (a) took and failed a prerequisite or (b) did not take either prerequisite. The performance of students who passed the pretest/accounting cycle screen was sig-nificantly better than the performance of the latter two groups. This finding implies that such a screen is more effec-tive than one simply based on grades in the introductory financial accounting class and that the approach would be use-ful for universities in which large per-centages of accounting majors have taken such a class at community col-leges. An additional objective of our study was to determine the effect on stu-dents’ performance in the first intermedi-ate accounting course. The results

indi-TABLE 3. Grades in Intermedi-ate Financial Accounting I: Native Students

Average

Period N grade

Fall 1993–

Spring 1996 88 2.25

Fall 1996–

Spring 1999 254 2.27

cate that accounting majors’ performance in the first intermediate accounting class was not affected, implying that a univer-sity need not offer separate introductory classes for accounting majors.

NOTES

1. San Francisco State University uses the fol-lowing grading scale for accounting courses:

A = 4.00 A– = 3.70 B+ = 3.30 B = 3.00 B– = 2.70 C+ = 2.30 C = 2.00 C– = 1.70 D+ = 1.30 D = 1.00 D– = 0.70 F = 0.00

2. It would be possible for students to take the pretest or ACCT 102 after receiving a grade in ACCT 301 as a result of the following:

(a) The student was allowed to take ACCT 301 without passing either the pretest or ACCT 102, received a grade lower than a C– (which is nec-essary to take the second intermediate account-ing course), and then was forced to pass the pretest or ACCT 102 to repeat ACCT 301. (b) The student was allowed to take the ACCT

301 without passing either the pretest or ACCT 102 but was forced to take ACCT 102 because it was, for a period of time, a required course in the accounting major.

3. As previously indicated, instructors have the discretion to waive prerequisites. The most com-mon reasons that students would be allowed to take the intermediate course after taking and fail-ing to pass either the pretest or ACCT 102 are that the instructor waived the prerequisite because (a) the student barely missed the cutoff point for pass-ing the pretest (i.e., achieved a score of 20 rather than the required score of 21); (b) the instructor knew the student as a result of teaching him or her in the introductory financial accounting course and believed, because of that personal experience, that the student was capable of successfully com-pleting the intermediate accounting course; or (c) the student’s grades in the prerequisite accounting classes, ACCT 100 and ACCT 101, were suffi-ciently good that the instructor believed that the student was capable of successfully completing the intermediate accounting course.

4. As we indicated, instructors have the discre-tion to waive prerequisites. The most common rea-sons that students would be allowed to take the intermediate course without taking either the pretest or ACCT 102 are that the instructor waived the prerequisite because (a) the instructor knew the student as a result of teaching him or her in the introductory financial accounting course and believed, because of that personal experience, that the student was capable of successfully completing the intermediate accounting course; (b) the stu-dent’s grades in the prerequisite accounting classes, ACCT 100 and ACCT 101, were sufficiently good that the instructor believed that the student was capable of successfully completing the intermedi-ate accounting course; or (c) the student claimed extenuating circumstances such as an inability to meet the testing or ACCT 102 class times or a reluctance to add an additional unit that could result in a significant increase in tuition. (Students taking

six or fewer units pay significantly less tuition than students taking more than six units. An instructor might waive the one-unit ACCT 102 requirement if it would result in the student’s incurring signifi-cantly higher tuition costs.)

REFERENCES

American Accounting Association, Accounting Education Change Commission. (1992, Fall). The first course in accounting: Position State-ment No. Two. Issues in Accounting Education,

249–251.

American Accounting Association, Committee on the Future Structure, Content, and Scope of Accounting Education (the Bedford Commit-tee). (1986, Spring). Future accounting educa-tion: Preparing for the expanding profession.

Issues in Accounting Education,168–195. Baxter, W. T. (1953, October). Recommendations

on accounting theory. The Accountant, 10,

405–410.

Bernardi, R. A., & Bean, D. F. (1999). Preparer versus user introductory sequence: The impact on performance in Intermediate Accounting I.

Journal of Accounting Education, 17, 141–156. Ingram, R. W., & Baldwin, B. (1996). Financial accounting: Information for decisions, ‘product

overview’ (2nd ed.). Mason, OH: Thomson

Learning Companies, South-Western. Mueller, G. G., & Simmons, J. K. (1989, Fall).

Change in accounting education. Issues in Accounting Education, 4,247–251.

Wilson, D. A. (1979, April). On the pedagogy of financial accounting. Accounting Review, 54(2), 396–401.

Zeff, S. A. (1979, July). Theory and “intermedi-ate” accounting.The Accounting Review, 54(3), 592–594.

APPENDIX

Program to Obtain a Bachelor’s Degree in Business Administration With a Concentration in Accounting

Business Core (All Business Majors)

Units General Education(GE—all San Francisco State University

students must take)

Segment I: Basis Subjects —12 units

Written Communication 3

Oral Communication 3

Critical Thinking 3

Quantitative Reasoning 3

Segment II: Arts and Sciences—27 units

3 courses in Physical and Biological Sciences Area 9 3 courses in Behavioral and Social Sciences Area 9 3 courses in Humanities and Creative Arts Area 9 Segment III: Relationships of Knowledge

3 courses 9 48

Business Core(all business majors must take)

Introduction to Economic Analysis 3

Principles of Financial Accounting 3

Principles of Managerial Accounting 3

Business Statistics 3

International Business 3

Business Finance 3

Business Communications 3

Information Systems 3

(appendix continues)