Vol. 43 (2000) 75–89

Entitlements and fairness:

an experimental study of distributive preferences

E. Elisabet Rutström

a, Melonie B. Williams

b,∗aDepartment of Economics, Darla Moore School of Business, The University of South Carolina,

Columbia, SC, USA

bUS Environmental Protection Agency, Mail Code 2172, Ariel Rios Building,

1200 Pennsylvania Avenue NW, Washington, DC 20460, USA

Received 11 January 1999; received in revised form 14 February 2000; accepted 23 February 2000

Abstract

Under three different rules for allocation of initial income we elicit experimental subjects’ pref-erences for income redistribution using an incentive compatible elicitation mechanism. The three income allocation rules are designed to capture preferences for distributive justice among sub-jects. The concern is motivated by claims in some of the experimental economics literature that non-self-interested motives often underlie individual behavior. We cannot reject self-interest in fa-vor of any redistribution motives based on our observations. Almost all individuals chose the income distribution which maximized their own income — high income individuals chose no redistribution and low income individuals chose perfect equality in income distribution. © 2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

JEL classification:D3; D63

Keywords:Equity; Distribution; Justice; Fairness; Experiments

1. Introduction

In this study we elicit preferences over income distribution in an incentive compatible way and test how such preferences relate to some simple notions of earnings-based justice. We employ a controlled laboratory setting with no income uncertainty and no strategic consid-erations. Under such conditions, any revealed preferences that are non-payoff-maximizing would be inconsistent with the traditional notion of self-interest, where the individual agent’s

∗Corresponding author. Tel.:+1-202-260-7978; fax:+1-202-260-7875.

E-mail address:[email protected] (M.B. Williams).

utility is independent of the utilities of other agents. Our results strongly favor self-interest and stand in stark contrast to previous experimental evidence.

Our interest in the question of individual preferences over income distribution arises from the discrepancy between theoretical predictions and previous experimental findings. Mainstream political economy models predict payoff-maximizing behavior based on the assumption that agents are motivated by self-interest. Simply put, within these models individuals’ decisions over economic policies do not reflect any preferences that involve a regard for others, whether based on justice or some other consideration. If this assumption is correct, then any preferences over income distribution that are revealed among members of a groupmustbe reflections of each member’s desire to maximize his own income and not of any desire to satisfy others’ wants or needs or to respect others’ rights. Consistent with the assumption of self-interested economic decision-making, several theories of distributive justice and social welfare further assume that decisions regarding what distribution is just can only be made by a representative individual in some “original position”, where the decision maker by assumption would not be biased by his own self-interest.1 Such decisions are sometimes referred to as being made behind a veil of ignorance. Individuals not positioned behind such a veil of ignorance are therefore expected to always act in a manner that disregards justice.

Laboratory experiments have been employed to test whether economic agents are gen-erally motivated by self-interest. Based on observing subjects choosing to redistribute income, many such studies have concluded that experimental subjects do not appear to be motivated solely by self-interest, and that this is true in many economic choice situ-ations and not only behind a veil of ignorance.2 Several experimenters now favor no-tions of fairness or altruism, in addition to monetary payoffs, as motivating individual choice.3

Revealed preferences over income distributions, however, appear to be very sensitive to variations in experimental design. Several experimental studies document results sug-gesting that the origin of initial entitlements has an effect on the extent of apparently non-self-interested behavior;4 when subjects are required to earn their initial entitlements, the frequency of apparently non-self-interested behavior is lower than when initial entitle-ments are allocated according to pure chance. Hoffman and Spitzer (1985, p. 260) propose that experimental subjects behave as if they believe in an earnings-based notion of justice; an unequal income distribution is (un)just when initial entitlements are (randomly assigned) earned. Such results appear to be consistent with equity theory in social psychology, which

1See, for example, Rawls’ (1971) definition of the “original position”, and Harsanyi’s (1955) distinction between

“impersonal social considerations” and “subjective” preferences. Binmore (1998) employs the process of the original position for the renegotiation of the social contract among players in the game of morals.

2The idea that revealed preferences may reflect moral considerations is not new. Harsanyi offers a definition

of subjective preferences that may incorporate moral considerations. Binmore (1994, 1998) offers an alternative definitional classification of preferences into self-interest narrowly conceived and self-interest broadly conceived. He develops these ideas into a complete theory of revealed ethical preferences. See Andreoni and Miller (1998) for a test confirming that distributive preferences obey the Generalized Axiom of Revealed Preferences, suggesting that there may be a trade-off between self-interest and justice motives.

is a theory of earnings-based justice.5 According to equity theory, payments to subjects in experiments get allocated in a way that reflects the subjects’ “intrinsic inputs”. The definitions of “intrinsic input” vary and may include the time spent, the amount of work completed, and also various personal characteristics such as intelligence and social status.6 Some of these definitions capture the notion that the employment of inputs in the task car-ries an opportunity cost and therefore justifies a compensation. We refer to this aspect as theresource costof the input. Other definitions capture the notion that input use leads to expansions in output which rightfully should belong to the producer. In fact, some measures of “intrinsic inputs” focus directly on the amount produced rather than on the inputs used. We refer to this aspect as theproductivityof the input.

We propose a test, not only of the existence of distributive preferences, but also of whether revealed preferences over income distributions are robust with respect to variations in some measure of theresource cost(which we will call “effort”) separately from variations in some measure of theproductivityof the resources used. We therefore perform the following joint hypothesis test: (H1) individuals have preferences over income distribution that differ from their own payoff maximization, and (H2) preferences over income distribution depend on how individuals perceive others’ “worthiness of compensation” as indicated byeitherthe amount of effort usedorby the amount of production performed in the task. For example, worthiness based on productivity could very well depend on how much effort was needed. In cases where productivity and effort cannot be separately observed, however, it is an open question whether it is the effort per se or the resulting production that determines worthiness. That is, it is possible that even unproductive effort can be considered worthy. We therefore add the following sub-hypotheses to H2: (H2,1) the effort used will warrant a compensation

even when the effort is unproductive and (H2,2) productivity, even with relatively little

effort, will be considered worthy of compensation. Later, we will refer to the distributive preferences expressed under the two sub-hypotheses aseffort-basedandproductivity-based preferences. We test these hypotheses by employing a laboratory task with which we can define and measure effort and productivity in a separable way. The task we employ is the Tower of Hanoi puzzle. Many other tasks that have been used in the literature, such as spell correction tasks, do not allow the observer to distinguish between effort and productivity.

With the exception of dictator games and majority voting games, all experimental ob-servations of redistribution choices have been performed using institutions where strategic considerations are important. We want to study individual preferences directly and there-fore our experimental design controls for strategic considerations. Given our interest in eliciting individualpreferencesover income distribution, we also control for differences in decision-making power (as exist in dictator games), which otherwise could provide a motivation for redistribution. In our experiment both advantaged and disadvantaged agents are able to improve their own position at the expense of the other agents. Therefore, we collect choice data not only from well endowed (high income) subjects, following previous dictator games, but also from poorly endowed (low income) subjects. Finally, we find it less interesting to study situations with trivial monetary consequences where the opportunity

5The origin of equity theory is found in Adams (1964) and Homans (1974). Much of equity theory has been

developed in the context of industrial relations, see, e.g., Akerlof (1982) and Akerlof and Yellen (1990).

cost of revealing justice-based preferences is very low. It is more informative to see if such behavior survives at higher opportunity costs.

The basic experimental design involves two phases. In Phase I subjects are assigned a task which will determine their initial income entitlement in Phase II. They work at this task individually. In Phase II subjects are brought together into groups of 12. Each subject is informed about the value of his initial income entitlement and how this has been determined. He is then asked to choose the distribution rule that results in his preferred final distribution of income. Hence, subject decisions should not be influenced by risk attitudes as decisions are made under complete information regarding income entitlements. Finally, to determine which distribution rule will determine the payoffs for the 12 subjects in the group, we employ an incentive compatible mechanism called theRandom Dictator ruleunder which everyone has the same chance of dictating the outcome and strategic considerations are eliminated.

Our results are surprising in light of previous experimental evidence. We find that we cannot reject the hypothesis that self-interest is the sole motivation for subject behavior in either of our earnings treatments. In our sample, 99 percent of subjects chose the dis-tribution rule which maximized their own final payoff. Because of the predominance of apparently self-interested behavior, we implement an additional robustness test, comparing behavior under earned entitlements to behavior under a random entitlement mechanism. In this session, we observe a slight increase in apparently non-self-interested behavior, albeit not in a way entirely consistent with earnings-based distributive preferences. The difference is significant in the statistical sense, though the absolute magnitude is small. Despite this slight support for non-self-interested behavior, we conclude that the model of self-interest in individual decision-making can explain our data very well.

The following section presents an overview of related literature. Section 3 details the experimental design, while the results are presented in Section 4. Conclusions and discussion follow in Section 5.

2. Previous findings

2.1. Tests of distributive justice theory

Several experiments have been designed with the direct purpose of testing theories of distributive justice. These experiments employ group decision-making mechanisms based on unanimity or majority rule. Because of their focus on preferences behind a veil of ignorance, these experiments employ incomplete information about initial entitlements, allowing risk attitudes to be a factor in determining outcomes.7

The experiments documented in Frohlich et al. (1987a,b) and Lissowski et al. (1991) incorporate random entitlement allocations, where all members are uncertain of their in-come position and a unanimous agreement is required of the five-person committee after open discussions. In these studies, group decisions result in redistributions. Frohlich and

7Beck (1994) explicitly tests for the influence of risk attitudes on distributive preferences. When using a Random

Oppenheimer (1990) use a similar design but allocate initial entitlements according to per-formance in a task. Although their focus is not directly on testing how the earnings treatment affects distributive preferences, the revealed group preferences appear to be similar to those observed when using the random allocation mechanism. The use of the unanimity rule, however, does not allow one to observe individual preferences.

Beckman and Smith (1995) use a simple majority rule voting mechanism with full anonymity and a random entitlement allocation. There are two predetermined distribu-tion opdistribu-tions over which each five-person committee can vote. The majority rule decision mechanism allows for observation of individual preferences in addition to the group choice. Subjects choose income distributions under both certainty and uncertainty of income entitle-ments. Beckman and Smith find that they cannot reject self-interested behavior. When initial entitlements are uncertain, subjects reveal a high degree of support for transfers (40 percent voted in favor of redistribution), despite deadweight costs in the transfer mechanism. When initial entitlements are certain, however, only 4 percent of subjects vote for transfers when the transfer would negatively impact their final payment. Thus, the proportion of subjects that reveal choices that are apparently non-self-interested is very small.

2.2. Bargaining and dictator games

Examples of apparently non-self-interested choices abound in the bargaining literature. In ultimatum games such choices by proposers are frequently observed, but could be a result of the strategic nature of the game as proposers might fear that receivers will reject low offers.8 Nevertheless Kahneman et al. (1986) and Forsythe et al. (1992) find evidence of non-self-interested behavior in dictator games with a random allocation rule for initial positions, where there is no issue of strategic interactions. This suggests that it is not the strategic aspect of the ultimatum bargaining games alone that causes such behavior. Hoffman et al. (1994) also find that choices in the ultimatum game are not robust with respect to the rule used for allocating initial entitlements. When subjects earn the right to be the proposer in an Ultimatum game, based on performance in a knowledge test, the median offer drops relative to when the right to be the proposer is randomly allocated. This lends some support to equity theory, but fails to distinguish between equity based on effort and equity based on productivity.

Hoffman and Spitzer (1985) and Burrows and Loomes (1994) directly examine the effects on individual choices of random vs. earned initial entitlement allocations. In these studies, the prediction that earned entitlements will be perceived differently than randomly allocated entitlements is attributed to John Locke9 and referred to as “Lockean desert”. Burrows and Loomes (1994, p. 3) describe Lockean desert as “an entitlement to resources which have been produced through the person’s expenditure of effort.”

Hoffman and Spitzer (1985) model a two-person Coasian bargaining situation in which one agent is designated the role of “controller” based on performance in a task. The task is an interactive two-person hash mark game. Essentially, the controller is endowed with both the initial income entitlement and with the decision-making power. The dollar value of

the entitlement is independent of which allocation rule is used, either random or earned; in particular, it is independent of the performance in the earned allocation rule. Hoffman and Spitzer find a high proportion of equal-split outcomes in the random allocation treatment, even though an equal split makes the controller worse off than with the initial entitlement value that would apply under a disagreement outcome. Hoffman and Spitzer find some reduction in this type of non-self-interested behavior when using the earned allocation rule, but the outcomes are still mixed.

Hoffman and Spitzer emphasize the importance of effort in determining whether an individual deserves the entitlement in a Lockean sense. “The Lockean theory posits that an individual deserves, as a matter of natural law, a property entitlement in resources that have been accumulated or developed through the individual’s expenditure of effort” (p. 264) and, hence, Lockean desert appears to be consistent with equity theory (p. 265). Nevertheless, Hoffman and Spitzer also “think that a Lockean theory of property has room within it for differences inefficacyof effort: even if two people spend the same amount of time or try as hard, the person who does a better job still deserves the resource” (p. 273). In the Hoffman and Spitzer experiments the role of controller is allocated according toperformanceas a measure of effort. Thus, in their design effort isdefined asproductivity.

The experimental design in Burrows and Loomes (1994) consists of a two-person trading environment. As in Hoffman and Spitzer, the decision-making power over redistributions rests with the holding of initial income entitlements. Unlike Hoffman and Spitzer, however, the dollar value of entitlements depend on performance in the earnings phase. Burrows and Loomes also find that allocating entitlements according to a task, rather than just ran-domly, affects bargaining outcomes. When initial entitlements are unequal, the proportion of bargaining outcomes yielding equal splits of final payoffs falls when entitlements are earned relative to when they are random. At the same time, however, the proportion of equal splits of the gains from trade increases. Burrows and Loomes suggest that their results may support a slightly revised version of Lockean desert theory, which they refer to as “two-part desert”; desert derives not only from the effort that produces the allocation of initial entitle-ments, but also from effort in the bargaining process itself. Equal splits of gains from trade correspond to a notion of just desert if the effort in the bargaining process is perceived to be equal across subjects.

3. Experimental design

In the present design we incorporate two treatments where initial income entitlements areearned. We distinguish betweeneffort-based earned entitlements andproductivity-based earned entitlements. As an additional robustness test of earnings-based justice motives, we also include a simplified design with arandomincome entitlement allocation.

The productivity and effort treatments both consist of two phases.10 Phase I is the performance phase: subjects perform a task which determines their initial income for the second phase of the experiment. In Phase I subjects know only that their performance in

10A web-appendix summarizes our instructions which contain more detail on the design. The appendix can be

Phase I will determine their initial income in Phase II; they are not toldhowtheir income will be determined. In Phase II subjects are brought back into groups of 12 and are informed of their initial income and its relationship to their performance in Phase I. Subjects are then asked to choose a distribution rule.11 We take great care to ensure anonymity throughout the experiment, but do not implement a double-blind design as we wish to control for subjects’ socio-demographic characteristics, which must be elicited and matched to individual subject responses. Subjects generally know who is in their group, but do not know the initial income of others or their choices. Subjects are identified by randomly assigned Subject ID numbers only. The experimenter is unable to attach an ID number to an individual. Final payoffs are known only to the subject and a “payment clerk” who is not present during the experiment. In the performance phase subjects are given 30 minutes to solve a computerized version of the Tower of Hanoi problem. Subjects are encouraged to solve the problem more than once. The task can be described as follows: there arekpegs andndisks. The disks are of different sizes and arranged in a pyramid on one peg (the source peg). The object is to move the stack of disks from the source peg to another specified peg (the goal peg), moving only one disk at a time and never placing a larger disk onto a smaller disk. In our experiment the number of pegs is three and the number of disks is five, yielding a rather difficult solution which requires aminimumof 31 moves to solve. We choose this particular task because it allows us to observebotheffort and productivity with no change in experimental instructions. Therefore, there is no difference between treatments in the performance phase. Subjects do not know which treatment they are in during Phase I, nor do they know that we have two treatments in Phase II.

Productivity is measured via the number and quality of solutions. Foreachsolution found, subjects receive 62 “units”, but then lose one unit for each move that particular solution uses in excess of the minimum number of moves (31). Thus, it is possible to solve the problem yet earn zero units if the solution requires 93 (62+31) or more moves. Subjects are given 10 points for each solution found, plus 1 point for each unit received. Points are then positively related to income. In addition, we let the size of the total group entitlement depend on the average productivity in the group. This is quite distinct from the effort treatment where the total group income is kept constant. This design feature should strengthen the expression of productivity-based distributive preferences, since low productivity individuals receive a higher income when teamed up with high productivity individuals.

Effort is measured as the total number of moves the subject makes within the allotted 30 minutes. Total group income is predetermined in the effort treatment, and subjects are assigned places in the income distribution according to their level of effort. Contrary to the productivity treatment in which individual earnings decrease in the number of moves, here individual earnings increase in the number of moves. The relative position of players into income classes based on the number of moves they performed is therefore inverted across these two treatments. There is no reason, therefore, to expect that our subjects would equate

11The two phases of the earned income entitlement treatments were conducted on separate days and all Phase

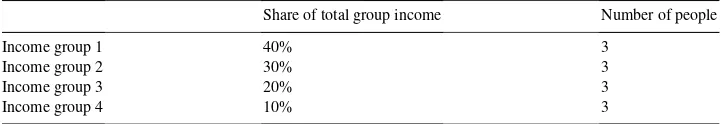

Table 1

Initial income shares

Share of total group income Number of people

Income group 1 40% 3

Income group 2 30% 3

Income group 3 20% 3

Income group 4 10% 3

effort and productivity when they consider how worthy other subjects are of compensation. This allows us to test whether the amount of effort, independent of the productivity of that effort, increases a person’s worthiness for compensation. We recognize that there are other types of effort the subject might put into solving a task, but physical effort, such as moving disks, is the one which is most easily observable and quantifiable.

An important experimental control is to preserve the redistribution rules and to ensure budget balance across the experimental sessions. If we do not maintain redistribution rules we cannot compare the results of the treatments, and if we do not impose budget balance we are not ensuring that all transfers are financed by participating subjects.12 Our solution to this design problem involves defining income classes and redistribution rules in terms of percent allocation of the total initial income for the group. This makes the definition of income class comparable across treatments, but allows total income in the productivity treatment to vary with aggregate performance in the group.

In Phase II, subjects are randomly sorted into groups of 12 across treatment conditions. We explain to them how point earnings are determined. Subjects are then informed that the total group income is divided among four initial income categories. We explain that the three individuals who earned the most points will together receive an initial income of 40 percent of the total income, to be divided equally among those three individuals. The three individuals who earned the fewest points will together receive an initial income of 10 percent of the group income. The remainder of the group income is divided similarly, as illustrated in Table 1. We then distribute income slips which inform each subject of his point earnings and his place in the initial income distribution. Once subjects receive their income slips, they are presented with four distribution rules as shown in Table 2. Subjects are informed that the group will choose one rule which will determine their final payoffs. Distribution rules are presented as income class shares in aggregate group income, and we explain to subjects that this share will be divided equally among the three individuals in each initial income class. Because the translation of shares into final dollar payoffs for the productivity treatments is dependent upon aggregate production in Phase I and which

12If we use redistribution rules that apply the same tax and subsidy rates across treatments, we cannot ex ante

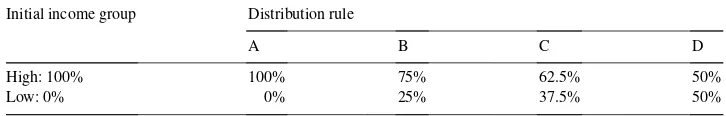

Table 2

Distribution rules for effort and productivity treatments Initial income group Distribution rule

A B C D

I: 40% 40% 35% 30% 25%

II: 30% 30% 28% 27% 25%

III: 20% 20% 22% 23% 25%

IV: 10% 10% 15% 20% 25%

subjects show up for Phase II, they cannot be calculated in advance of the experimental session. Therefore, subjects in each experimental session are shown via blackboard how income shares translate into final dollar payoffs. The distributions of final payoffs for each session are presented in Appendix A.

As detailed in the following section, we observe a predominance of behavior consistent with self-interest across both of our earned entitlements treatments. Accordingly, we de-cided to implement an additional treatment designed to test a random income entitlement rule. Our hypothesis under random entitlements is that advantaged subjects should favor more redistribution than in the earnings treatments and that low income subjects will reveal a preference for full redistribution. To give this hypothesis its best shot, we utilize a single phase design with two income classes involving only the most and the least advantaged agents. Subjects are assigned a high ($40) or low ($0) initial income by means of a lot-tery, where the probability of receiving either income is 50 percent for each subject. The distribution rules incorporated in this treatment are presented in Table 3.

To ensure truth-telling we use the Random Dictator decision rule, which is theoretically incentive compatible. Subjects make their choices anonymously and one individual is ran-domly and anonymously chosen to be the dictator. This individual’s choice determines the distribution rule to be used. Because only one individual’s choice determines the outcome, subjects cannot gain by engaging in strategic behavior. This decision mechanism also has the property that the probability of becoming the dictator is equal across all subjects, and the dictator is not selected until after distribution choices are made. To ensure that subjects understand their incentives, we explain by way of example why truth-telling is their best strategy. In addition, we conduct a Random Dictator trainer which involves a choice over four different types of candy. The candy chosen in the trainer is distributed to all participants. Finally, we gather information on age, sex, household size, household income, country of birth, race and education.

Table 3

Distribution rules for random treatmenta

Initial income group Distribution rule

A B C D

High: 100% 100% 75% 62.5% 50%

Low: 0% 0% 25% 37.5% 50%

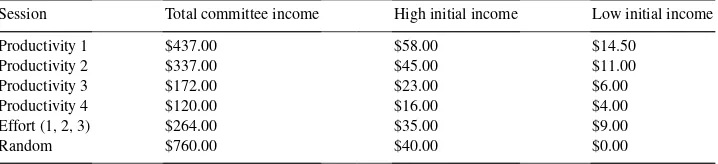

Table 4

Total group and initial incomesa

Session Total committee income High initial income Low initial income

Productivity 1 $437.00 $58.00 $14.50

Productivity 2 $337.00 $45.00 $11.00

Productivity 3 $172.00 $23.00 $6.00

Productivity 4 $120.00 $16.00 $4.00

Effort (1, 2, 3) $264.00 $35.00 $9.00

Random $760.00 $40.00 $0.00

an=12 for all productivity and effort sessions;n=38 for random session.

Based on the shares presented in Tables 2 and 3 we can specify our hypotheses as follows: under hypothesis H1, subjects will not always choose the payoff-maximizing alternatives, where payoffs are maximized under distribution rule A for the higher income classes (Initial Income Groups “I” and “II” in the earnings treatments and “high” in the random treatment), and distribution rule D for the lower income classes (Initial Income Groups “III”, “IV” and “low”). Our experiment is not designed to reject this hypothesis, but we could reject its alternative, self-interested payoff maximization, if we observe a significant proportion of choices other than A for the higher income groups and other than D for the lower income groups. Under hypothesis H2,1, we would expect significantly fewer subjects to choose

redistribution in the effort treatment than in any other treatment because more participants would consider the high income subjects worthy. This hypothesis can therefore only be rejected based on a comparison of behavior across treatments. Hypothesis H2,2, similarly,

predicts that significantly fewer subjects will choose redistribution in the productivity treat-ment compared to all the other treattreat-ments. If, for example, we find that all subjects in the higher income groups choose C in the productivity and random treatments, but A in the effort treatment, and all subjects in the lower income groups choose D in the productivity and random treatments, but B in the effort treatment, we would reject hypothesis H2,2but

not hypothesis H2,1.

4. Results

Our subjects consisted of graduate and undergraduate students from various colleges at the University of South Carolina. Twelve subjects participated in each of four productivity sessions (or groups) and three effort sessions (84 subjects in total). Thirty-eight subjects participated in a single random entitlements treatment session.

Performance in Phase I was highly variable. Not only did this result in a high degree of variability in total group income across productivity groups, but also in a large degree of variability in the relative size of possible dollar transfers. Table 4 presents total income as well as highest and lowest initial incomes for each session.13

13Comprehensive information on initial incomes and final payoffs for each distribution rule for all sessions is

Observed behavior in the productivity and effort sessions indicates that we cannot reject self-interest as the motivation for subjects’ choices. With one exception, all subjects in the high initial income classes chose to keep their initial income (distribution rule A). This distribution rule maximizes payoffs to income classes I and II.14 All low income individuals (income classes III and IV) without exception chose full redistribution (distribution rule D), which maximizes payoffs to these income classes. This result is stable, not only across earnings treatments, but also across different group income levels.15

In the random income entitlements treatment, we observe that 33 of the 38 subjects chose the distribution rule which maximized their immediate payoffs. Five subjects chose distri-butions which did not maximize their immediate payoffs. Two of these were high income individuals; both chose distribution rule B (payoffs of $30 and $10 to high and low income classes, respectively). The fact that more high income subjects choose redistribution in this treatment relative to the earned entitlements treatments is consistent with earnings-based justice (the notion that an unequal distribution based on randomly assigned entitlements is unjust), but two of 38 subjects is not sufficient to reject the self-interest model of behavior. Three low income individuals in the random entitlements treatment chose distributions which did not maximize their immediate payoffs; one chose rule B and two chose rule C (payoffs of $25 and $15 to high and low income classes, respectively). This behavior is contrary to an earnings-based justice concept, since input is the same for high and low income individuals. It is, however, consistent with a property rights argument where the subject believes that high income individuals have rights to their “lottery winnings”.16 Since the opportunity cost of time spent in the random treatment is relatively low, the cost of respecting property rights in lottery winnings is low relative to the earned entitlements sessions.17

These observations do not offer strong support for earnings-based preferences arising from either productivity or effort, as modeled in our design. This is not sufficient to generally reject the existence of distributional preferences based on worthiness, however. It is an open

14The one exception was an individual in a productivity session who was placed in initial income group II ($43.50

in this particular session) and who chose distribution rule D (a final payoff of $36.50, or a transfer of 16 percent of his initial income entitlement). This behavior is not consistent with productivity-based preferences, however, but is consistent with effort-based preferences.

15It is worthwhile to emphasize the variation in group and initial incomes across the productivity sessions, as these

differences imply variation in the absolute “price” of just, or fair, behavior. Nevertheless, we acknowledge that even our lowest price may be “too high” for us to observe the expected variation in subjects’ choices, if revealing justice-based preferences has only a trivial value for subjects.

16In pilot experiments incorporating random income entitlements, subject responses to debriefing questions

suggested that subjects had diverse perceptions of property rights along the lines we discuss here.

17We use the non-parametric McNemar test to determine if our treatment conditions have a significant effect

Table 5

Responses to debriefing questionsa

Question number Productivity Effort

High income (n=24) Low income (n=24) High income (n=18) Low income (n=18)

1 23/24 21/24 8/16 8/13

2 22/23 5/24 10/15 7/15

aEntries are ratios of Yes responses to total Yes/No responses (total responses will be less thannif subject

responded “Do not know”).

question whether other mechanisms for allocating initial entitlements would cause subjects to choose distribution options in an apparently non-self-interested way. Nevertheless, our findings are striking in comparison to the significance of such choices in earlier experiments as reviewed above.

It may be interesting to compare subjects’ actual choices to theirstatementsabout their perception of the “fairness” of the initial income distribution. Table 5 summarizes subject responses to the following debriefing questions distributed at the end of the productivity and effort Phase II sessions:

(1) (Productivity): Do you think it is fair to determine the initial income distribution according to how few moves your solution required and to how many solutions you found? (Effort): Do you think it is fair to determine the initial income distribution according to how many moves participants made?

(2) (Both): Do you think your initial income in this part was determined in a fair way? Question 1 was intended to elicit subjects’ perceptions of the fairness of the entitlement mechanism in determining the overallincome distribution. Question 2 was intended to elicit subjects’ perceptions of the entitlement mechanism in determining the subject’sown income. For most subjects, we find that their ex post statements of fairness in initial allo-cations are consistent with their actual choices over final distributions. This consistency is most pronounced in the productivity treatment; most low-income subjects state that their initial income was unfairly determined (though most state that the initial income distribu-tion was fairly determined). In the effort treatment, however, we note that half of the low income subjects claim that the initial income distribution and their own initial income are fairly determined, even though they choose full redistribution.

5. Conclusions

We implement an experimental design to test for the existence of preferences over income distributions that are motivated by earnings-based justice. With full certainty regarding ini-tial income entitlements, no strategic interaction, non-trivial payoffs, and equal probability of dictating the outcome across all group members, we find that we cannot reject self-interest as the motivating force behind the observed choices. Contrary to findings in many other experiments, the model of self-interest in economic decision-making appears to explain our data very well.

redistribution allowed. We find little variation in this behavior despite variations in how initial income entitlements are allocated. The revealed preference for no redistribution by high income subjects in the earnings treatments is consistent with justice-based preferences, as well as self-interest, if earned entitlements are important for justice. Nevertheless, if this concept of justice applies equally to both high and low income individuals, we would have expected low income subjects to reveal a respect for the rights of the high income subjects to keep their entitlements.

Based on the fact that neither the effort nor the productivity treatment result in a sig-nificantly different proportion of subjects that choose redistribution compared to the two other treatments, we reject both our effort and our productivity hypotheses. Nevertheless, we obviously cannot reject that choicescouldreflect such preferences with a different set of payoff parameters, such that the cost of behaving in a just way would be trivial, or with a different allocation rule for initial entitlements.

Explanations as to why our findings differ from previous ones can only be speculative. Nevertheless, a comparison of our experimental design to those of the previous literature offers two primary candidates: (i) the larger size of the group, and (ii) the possible per-ception of equality in decision-making power given that the dictator was chosen randomly afterthe redistribution choices where collected. All of the dictator and ultimatum games in the previous literature, as well as the games employed by Hoffman and Spitzer (1985) and Burrows and Loomes (1994), were played between pairs of subjects where the high-income subjects had the ultimate decision-making power over the distribution outcome. The only other experimental study of individual preferences employing a larger group size and a somewhat more equal decision-making power is Beckman and Smith (1995), who in fact also found a predominance of payoff-maximizing behavior. Binmore (1998) offers support for our proposal regarding the role of decision-making power (as modeled in the dictator vs. the random dictator games) by suggesting that people’s perception of fairness should depend on whether the random allocation of positions in the game of morals is done prior to the start of the game or in immediate conjunction with the allocation issue at hand. Our results suggest that further research on the relevance of such factors as group size and the distribution of decision-making power is needed to inform the design of mechanisms intended to elicit distributional preferences. Moreover, care should be taken when attempt-ing to infer preferences across alternative social choice situations where group size and decision-making power may differ.

Acknowledgements

Appendix A. Parameters for experimental sessions

Initial income group Distribution rule

A B C D

Random entitlements: total group income=$760.00

I: $40.00 $40.00 $30.00 $25.00 $20.00

II: $0.00 $0.00 $10.00 $15.00 $20.00

Productivity 1: total group income=$172.00

I: $23.00 $23.00 $20.00 $17.00 $14.50

II: $17.00 $17.00 $16.00 $15.50 $14.50

III: $11.50 $11.50 $12.50 $13.00 $14.50

IV: $6.00 $6.00 $8.50 $11.50 $14.50

Productivity 2: total group income=$437.00

I: $58.00 $58.00 $51.00 $43.50 $36.50

II: $43.50 $43.50 $40.50 $39.50 $36.50

III: $29.00 $29.00 $32.00 $33.50 $36.50

IV: $14.50 $14.50 $22.00 $29.00 $36.50

Productivity 3: total group income=$120.00

I: $16.00 $16.00 $14.00 $12.00 $10.00

II: $12.00 $12.00 $11.00 $10.50 $10.00

III: $8.00 $8.00 $9.00 $9.50 $10.00

IV: $4.00 $4.00 $6.00 $8.00 $10.00

Productivity 4: total group income=$337.00

I: $45.00 $45.00 $39.00 $33.50 $28.00

II: $33.50 $33.50 $31.00 $30.50 $28.00

III: $22.50 $22.50 $24.50 $25.50 $28.00

IV: $11.00 $11.00 $16.50 $22.50 $28.00

Effort 1, 2, 3: total group income=$264.00

I: $35.00 $35.00 $31.00 $26.00 $22.00

II: $26.00 $26.00 $25.00 $24.00 $22.00

III: $18.00 $18.00 $19.00 $20.00 $22.00

IV: $9.00 $9.00 $13.00 $18.00 $22.00

References

Adams, J.S., 1964. Inequity in social exchange. In: Berkowitz, L. (Ed.), Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. Academic Press, New York.

Akerlof, G.A., 1982. Labor contracts as partial gift exchange. Quarterly Journal of Economics 97 (4), 543–569. Akerlof, G.A., Yellen, J.L., 1990. The fair wage-effort hypothesis and unemployment. Quarterly Journal of

Andreoni, J., Miller, J.H., 1998. Giving according to GARP: an experimental study of rationality and altruism. Department of Economics, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI. Unpublished manuscript.

Beck, J.H., 1994. An experimental test of preferences for the distribution of income and individual risk aversion. Eastern Economic Journal 20 (2), 131–145.

Beckman, S.R., Smith, J.W., 1995. Efficiency, equity and democracy: experimental evidence on Okun’s leaky bucket. CRESP Working Paper No. 9509. Department of Economics, University of Colorado, Denver, CO. Binmore, K., 1994. Playing Fair: Game Theory and the Social Contract, Vol. 1. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Binmore, K., 1998. Just Playing: Game Theory and the Social Contract, Vol. 2. MIT Press, Cambridge, MA. Burrows, P., Loomes, G., 1994. The impact of fairness on bargaining behavior. Empirical Economics 19, 201–221. Conover, W.J., 1980. Practical Nonparametric Statistics. Wiley, New York.

Eckel, C.C., Grossman, P., 1995. Altruism in anonymous dictator games. Games and Economic Behavior 16, 181–191.

Eckel, C.C., Grossman, P., 1996. The relative price of fairness: gender differences in a punishment game. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 30 (2), 143–158.

Fehr, E., Kirchsteiger, G., Riedl, A., 1993. Does fairness prevent market clearing? an experimental investigation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 108 (2), 437–460.

Forsythe, R., Horowitz, J.L., Savin, N.E., Sefton, M., 1992. Fairness in simple bargaining experiments. Games and Economic Behavior 6 (3), 347–369.

Frohlich, N., Oppenheimer, J.A., 1990. Choosing justice in experimental democracies with production. American Political Science Review 80 (2), 461–477.

Frohlich, N., Oppenheimer, J.A., Eavey, C., 1987a. Laboratory results on Rawls’ distributive justice. British Journal of Political Science 17, 1–21.

Frohlich, N., Oppenheimer, J.A., Eavey, C., 1987b. Choices of principles of distributive justice in experimental groups. American Journal of Political Science 31, 606–636.

Güth, W., Schmittberger, R., Schwarze, B., 1982. An experimental analysis of ultimatum bargaining. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization 3, 367–388.

Harsanyi, J., 1955. Cardinal welfare, individualistic ethics, and interpersonal comparisons of utility. Journal of Political Economy 63, 302–321.

Hoffman, E., Spitzer, M.L., 1985. Entitlements, rights, and fairness: an experimental examination of subjects’ concepts of distributive justice. Journal of Legal Studies 14 (2), 259–297.

Hoffman, E., McCabe, K., Shachat, K., Smith, V., 1994. Preferences, property rights and anonymity in bargaining games. Games and Economic Behavior 7, 346–380.

Homans, G.C., 1974. Elementary Forms of Social Behavior. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York.

Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J.L., Thaler, R., 1986. Fairness and the assumptions of economics. Journal of Business 59, S285–S300.

Lissowski, G., Tyszka, T., Okrasa, W., 1991. Principles of distributive justice. Journal of Conflict Resolution 35, 98–119.

Locke, J., 1978. Second Treatise of Civil Government. W.B. Eerdmans, Grand Rapids.

Rabin, M., 1993. Incorporating fairness into game theory and economics. American Economic Review 83 (5), 1281–1302.