edited by dipesh chakrabarty, sheldon pollock, and sanjay subrahmanyam

Funded by a grant from the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation and jointly published by the University of California Press, the University of Chicago Press, and Columbia University Press

Extreme Poetry: Th e South Asian Movement of Simultaneous Narration by Yigal Bronner (Columbia)

Th e Social Space of Language: Vernacular Culture in British Colonial Punjab by Farina Mir (California)

Unifying Hinduism: Th e Philosophy of Vijnanabhiksu in Indian Intellectual History by Andrew J. Nicholson (Columbia) Everyday Healing: Hindus and Others in an Ambiguously

Islamic Place by Carla Bellamy (California)

Yigal Bronner

Publishers Since 1893 New York Chichester, West Sussex Copyright © 2010 Columbia University Press

All rights reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Bronner, Yigal.

Extreme poetry : the South Asian movement of simultaneous narration / Yigal Bronner. p. cm.—(South Asia across the disciplines)

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9 78- 0- 231- 15160- 3 ( cloth : a lk. p aper)— ISBN 9 78- 0- 231- 52529- 9 ( electronic) 1. Sanskrit poetry— History and criticism. 2. Puns and punning in literature.

I. Title. II. Series. PK2916.B72 2010 891'.21009—dc22 2009028171

Columbia University Press books are printed on permanent and durable acid- free paper. Th is book was printed on paper with recycled content.

Printed in the United States of America c 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 p 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

References to Internet Web sites (URLs) were accurate at the time of writing. Neither the author nor Columbia University Press is responsible for URLs that may have expired or

Dina and Fred Bronner

do ārat sabad bāj rījhe na koi A poem that doesn’t have

Dual- meaning words,

Such a poem does not

Attract anyone at all—

A poem without

Words of two senses.

— Ma{navī Kadam Rā’o Padam Rā’o of Fakhr- e Dīn Niz

Figures and Tables xiii Ac know ledg ments xv A Note on Sanskrit Transliteration xvii

% 1 &

introduction 1

1.1 Ślesa: A Brief Overview of the Mechanisms of Simultaneity 3 1.2 Th e Many Manifestations of Ślesa: A Brief Sketch 6

1.3 What (Little) Is Known About Ślesa 7

1.4 Th e Anti-Ślesa Bias: Romanticism, Orientalism, Nationalism 9 1.5 Is Ślesa “Natural” to Sanskrit? 13

1.6 Toward a History and Th eory of Ślesa 17

% 2 &

experimenting with

le

s

a

in subandhu’s prose lab 20

2.1 Th e Birth of a New Kind of Literature 202.2 Th e Paintbrush of Imagination: Plot and Description in the Vāsavadattā 25

2.3 Amplifying the World: Subandhu’s Alliterative Compounds 33

2.5 Teasing the Convention: Th e Targets of Subandhu’s Ślesa 44 2.6 Bāna’s Laughter and the Response to Subandhu 50

2.7 Conclusion 55

% 3 &

the disguise of language:

le

s

a

enters the plot 57

3.1 Kīcakavadha (Killing Kīcaka) by Nītivarman 58

3.2 Th e Elephant in the (Assembly) Room: Nītivarman’s Buildup 60

3.3 From Smoldering to Eruption: Draupadī’s Ślesa and Its Implications 64

3.4 Embracing the Subject: Ślesa and Selfi ng 71 3.5 Embracing Twin Episodes: Ślesa and the Refi nement

of the Epic 75

3.6 Flowers and Arrows, Milk and Water: Responses to Nītivarman’s Ślesa 78

3.7 Sarasvatī’s Ślesa: Disguise and Identity in Śrīharsa’s Naisadhacarita 82

3.8 Conclusion 88

% 4 &

aiming at two targets:

the early attempts 91

4.1 Th e Mahabalipuram Relief as a Visual Ślesa 924.2 Dandin: A Lost Work and Its Relic 99

4.3 Dhanañjaya: Th e Poet of Two Targets 102

4.4 Lineages Ornamented and Tainted: On Ślesa’s Contrastive Capacities 106

4.5 What Gets Conarrated? Dhanañjaya’s Matching Scheme 112

% 5 &

bringing the ganges to the ocean:

kavirja and the apex of bitextuality 122

5.1 Th e Boom of a Ślesa Movement 123

5.2 Th e Bitextual Movement and the Lexicographical Boom 128

5.3 Sanskrit Bitextuality in a Vernacular World 132

5.4 Kavirāja’s Matching of the Sanskrit Epics 140

5.5 Amplifying Epic Echoes 148

5.6 Conclusion 153

% 6 &

le

s

a

as reading practice 155

6.1 Th e Imagined Ślesa Reader: Repre sen ta tions and Instructions 156 6.2 Th ings Th at Can Go Wrong with Ślesa:

Th e Th eoreticians’ Warning 159

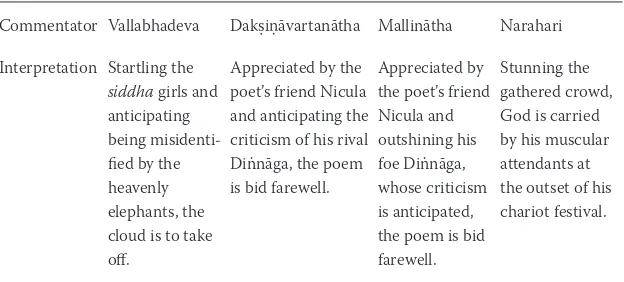

6.3 Seeing Shapes in Clouds: Diff erent Readings of Meghadūta 1.14 169

6.4 Old Texts, New Reading Methods: Th e Commentaries on Subandhu 176

6.5 Ślesa and Allegory in the Commentaries on the Epic 181 6.6 Double- Bodied Poet, Double- Bodied Poem:

Ravicandra’s Reading of Amaru 183

6.7 Th e Ślesa Paradox 192

% 7 &

theories of

le

s

a

in sanskrit poetics 195

7.1 Th eorizing Ornaments: An Overview of Alamkāraśāstra 196

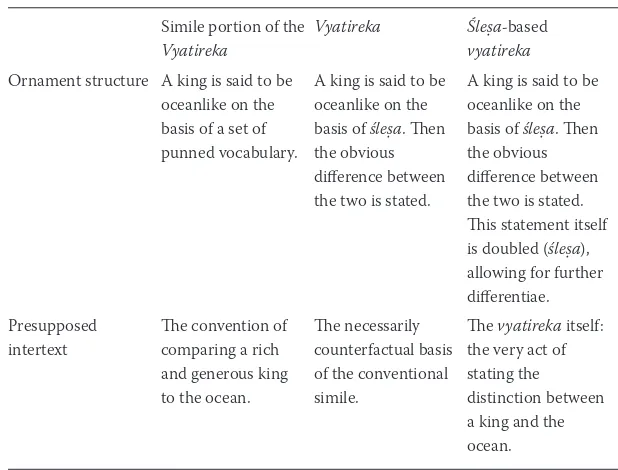

7.2 Ślesa as a Th eoretical Problem 203

7.3 Speaking Crookedly and Speaking in Puns: Ślesa’s Role in Dandin’s Poetics 214

% 8 &

toward a theory of

le

s

a

231

8.1 A Concise History of the Experiments with Ślesa 2318.2 Ślesa as a Literary Movement 234 8.3 Ślesa and Sheer Virtuosity 239 8.4 Ślesa and the Registers of the Self 242 8.5 Ślesa and the Refi nement of the Epic 246

8.6 Playing with the Convention: Ślesa and Deep Intertextuality 250 8.7 Ślesa and Kāvya’s Subversive Edge 254

8.8 Extreme Poetry and Middle- Ground Th eory: Th e Challenges Posed by Ślesa 257

Appendix 1: Bitextual and Multitextual Works in Sanskrit 267 Appendix 2: Bitextual and Multitextual Works in Telugu 272

Notes 277 References 315

figures

Th e Svayamvara of Damayanti/Damayanti Carried to the marriage choice xx

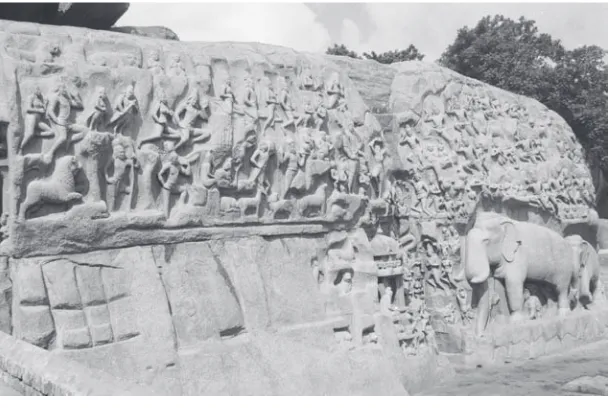

4.1 An Overview of the Mahabalipuram Relief 93

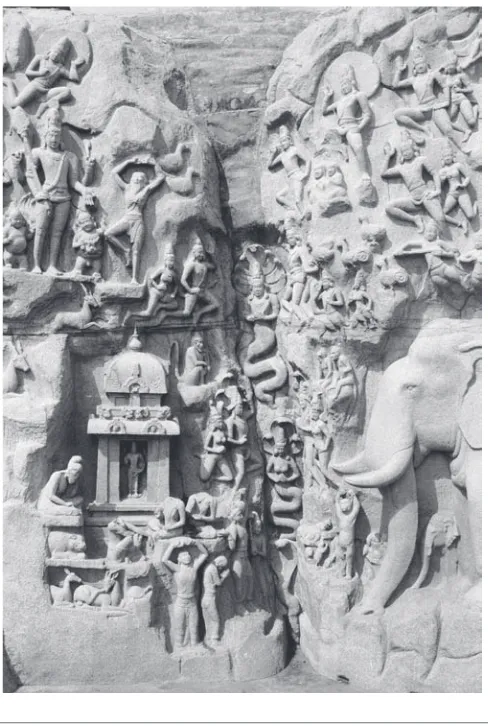

4.2 Śiva Grants a Boon to an Ascetic: Detail from the Maha balipuram Re lief 94

4.3 Center of the Mahabalipuram Relief: Th e River Ganges 96

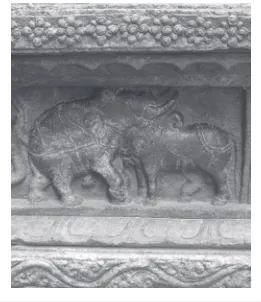

4.4 Th e Bull- Elephant: A Motif from the Jalakantheśvara Temple in V ellore 98

tables

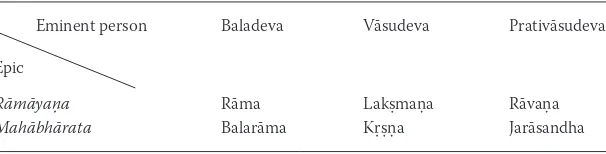

4.1 Triads of the Jain Epic Narratives 106

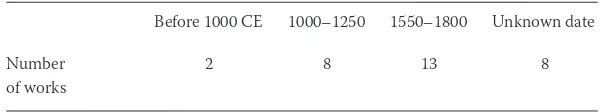

5.1 Bitextual and Multitextual Sanskrit Works by Period 123

5.2 Bitextual and Multitextual Telugu Works by Century 135

6.1 Diff erent Readings of Meghadūta 1 .14 175

6.2 Diff erent Readings and Interpretations of a Go- Between’s Message in Subandhu’s Vāsavadattā 180

T

his book was a long time in the making, and along the way I have incurred many debts. It is my pleasant duty to thank all those who helped me in the pro cess of researching, writing, and editing it and bringing it into its current shape. First and foremost, I wish to thank my two lifelong teachers: Sheldon Pollock, who encouraged, facilitated, and im mensely enriched my work on this project in its many incarnations; and David Shulman, who introduced me to the fi eld of Sanskrit poetry and poetics and who has off ered endless support and invaluable feedback in the pro cess of completing this book. My debt to these two men and their intellectual and personal generosity would be impossible to repay.For their guidance, patience, and generosity I am grateful to many other teachers as well. Th ese include H. V. Nagaraja Rao in Mysore, as well as N. R. Bhatt, K. Srinivasan, and the late S. S. Janaki in Chennai. Although they were never offi cially my teachers, Lawrence McCrea and Gary Tubb have taught me a great deal, and their comments on this book as it evolved were simply priceless. Special thanks are also due to V. Narayana Rao and Vimala Katikaneni, who, together with David Shulman, helped me with the Telugu materials, and my colleague Sascha Ebeling, who enriched my understanding of Tamil ślesas. I am also indebted to Steven Collins and Wendy Doniger, my former professors and now colleagues, and to the many colleagues at the University of Chicago who off ered crucial intel-lectual and moral support. Finally, I wish to convey deep gratitude to my beloved and much- missed Tamil teacher, Norman Cutler, who died pre-maturely in 2002.

Chicago’s amazing Regenstein Library; Dr. V. Kameswari, Hema Varada-rajan, and the entire staff of the Kuppuswami Research Institute in Chen-nai; Professor Saroja Bhate in Pune; Dr. E. R. Ramabai and Dr. M. Visal akshi at the University of Madras and the New Cata logus Cata logorum offi ce; and Dilip Kumar, who was in charge of sending endless packages of books from Chennai to my various addresses. Th anks also to Michael Rabe and Anna Seastrand, who kindly shared with me their photography of and thoughts about Indian art, and Jonathan Bader, who did the same with regard to the hagiographies of Śa]kara.

I am deeply indebted to all those who helped me revise and prepare this book for publication: Catherine Rottenberg and Neve Gordon, friends and partners in many ventures, who carefully read many of my drafts and who were always there for me whenever I needed any help or advice on the intricacies of the academic and publishing worlds; Daisy Rockwell and Daniel Wyche, who both read through the entire manuscript and made extensive editorial suggestions; and Jeremy Morse, who has been a one- man tech team and without whose help I could not have formatted the bibliography and footnotes. Th anks also to Alicia Czaplewski for all her assistance. I am also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for their many useful suggestions and corrections and to Avni Majithia- Sejpal, John Donohue, Charles Eberline, and the outstanding editorial team at South Asia Across the Disciplines and Columbia University Press.

Several institutions and foundations contributed to my research and writing: Th e U.S. Department of Education Fulbright- Hays Doctoral Dis-sertation Research Abroad program, the Mrs. Giles Whiting Foundation, the American Institute of Indian Studies, and the Committee on Southern Asian Studies at the University of Chicago. Special thanks to the Institute of Advanced Studies in Jerusalem, which generously hosted me several times during the past years.

I

magine a poem of large or even epic proportions, say, the try to imagine that the language of this poem is constructed in such a Iliad. Now way that it simultaneously tells an entire additional story. Suppose, in other words, that each verse of the Iliad could simultaneously be read as narrating the Odyssey as well. It is hard to imagine that language could sustain such an eff ort and still be intelligible, let alone beautiful. We can conceive of punned words or even proverbial utterances that are doubly readable, such as “Gladly the cross- eyed bear” for “gladly the cross I’d bear,” but a large- scale poem that is consistently “bitextual” seems inconceivable.Even if there were a person qualifi ed to compose such a bitextual poem— a master linguist, philologist, literature specialist, and gifted poet in one— it would be far from easy to establish a readership for it. Th e de-coding of such poetry would require a reader just as knowledgeable as and no less capable than the poet. Th e reader would have to master the same dictionaries and lexicons as the poet and go through the same linguistic and literary training. He or she would have to be an equal partner in the act of making double sense of a single text.

However, it is not just the im mense diffi culty of composing and reading such poetry that makes it so hard to imagine. Th e very idea seems alien to modern aesthetic values and to our notions of how literature should be enjoyed and how language works. Why, one might ask, would poets invest such eff ort in composing a bitextual poem? Why would readers take the trouble to read it? What possible enjoyment could one fi nd in the conar-ration of the Iliad with the Odyssey besides marveling at the actual feat of combining them?

At the very least, it is diffi cult to imagine that such poetry would be the result of a sudden, inexplicable burst of creative energy. Had we been asked to believe that a few dozen Iliad-Odyssey works actually existed, we could only assume that they were the product of prolonged cultivation by a large group of authors, readers, language specialists, and critics. Only then could we envision a variety of bitextual works, including not just double- epic poems but also, say, “an Iliad where every line and every word should bear a secondary reference to Napoleon’s campaign in Upper Italy.”1

too peculiar to be taken seriously and, at the same time, something natu-ral to India. It is an aberration, but it is also normal.

As a result, this fascinating literary movement has been left in utter obscurity. No one has ever bothered to examine when and how bitextual ślesa poetry was composed, let alone why. Not a single bitextual poem has ever been studied analytically by modern academics. Many Indologists have only a faint idea that this productive genre exists, and those inter-ested in South Asian culture more generally typically know nothing about it. Similarly, Western literary theorists, who have only recently begun to consider wordplay and puns as a worthy object of serious interrogation, are totally unaware of the existence of ślesa, undoubtedly the greatest ex-periment with such poetic devices in the history of world literature.

Th e purpose of this book is to begin fi lling this wide lacuna. It is an at-tempt to underscore and examine the various literary goals and contribu-tions of the ślesa movement. Th e book charts the major phases in the evolution of the movement and off ers a close reading of several central poems from each subgenre in its history. Attention is also given to the readers of ślesa poetry, as well as to the extensive theoretical discourse dedicated to it in Sanskrit. My ultimate objective in this work is to address two crucial questions: Why was South Asian culture so fascinated with the possibility of saying two things at the same time? And what does this literary phenomenon teach us about poetry in general, and about the ways texts generate meaning?

1.1

les.a

: a brief overview of the

mechanisms of simultaneity

he happily relaxed in the bottom sleeper. It was a while before he began to sense that something was not in order. He turned to his neighbor and asked, just to be on the safe side, where they were heading. “Bombay,” came the answer. For a long while the man felt puzzled. Finally he ex-claimed: “How amazing is modern technology! In the same train, the up-per berth travels to Delhi and the lower to Bombay.”2

Ramanujan used this story to illustrate a kind of mental fl exibility on the part of the puzzled passenger. In his view, that the passenger could think in two opposite ways simultaneously is symptomatic of his thesis regarding an “Indian way of thinking.” Th e subject matter of this book also demands such mental fl exibility on the part of its writers and readers alike. In the following pages we will examine a literary train that does in-deed travel in two directions; and we will take a look at its engine. Th e literature in question was created by Sanskrit poets using a variety of techniques, some more familiar to the Western reader than others. Th ese techniques were cata loged by Sanskrit literary thinkers under the heading ślesa (embrace), a term that underscores the tight coalescence of two de-scriptions or narratives in a single poem.

Let us look at a couple of simple examples:

Here’s a king who has risen to the top. He’s radiant, his surrounding circle glows, and the people love him for his levies, which are light.3

Th is poem depicts moonrise as a king’s rise to power. Th is dual eff ect is achieved by the careful juxtaposition of lexical items that lend themselves to the portrayal of both the lunar and the royal: udaya refers to the eastern mountain, over which the moon ascends, as well as to a king’s rise to power; mandala means a circle, like the moon’s disc, but has a more tech-nical sense in po liti cal discourse of a king’s circle of allies; karas are the moon’s rays, but they also denote the taxes a king levies; and the moon itself is conventionally thought of as the king of the stars. Th us the poem is consistently dual, and both its registers are instantly audible to the trained listener.

we can fi nd similar homonyms in the target language.4 But Sanskrit poets

have other, more sophisticated ways of creating linguistic embraces that can be reproduced only by resorting to a set of two parallel translations. Consider the following example:

Having secured an alliance with that vicious king, whose conduct is far from noble, is there anything to stop this villain from tormenting his enemy— me?

A villain made an unholy alliance with a corrupt king in order to harm his nemesis. But the portrayal of this dubious po liti cal deal can also be read as describing the rising moon. Read diff erently, the cruel knight is the night, always tormenting the lonely:

Now that he’s joined by that nocturnal king, who resides among the planets, is there anything to stop the eve ning from tormenting me—

separated from my beloved?5

For pining lovers, the moon is indeed a vicious king who joins forces with their dreaded enemy, nightfall, in a scheme to torture them.

Each “translation” considered separately obviously misses the poem’s main objective, namely, the simultaneous depiction of a king and a moon. Th is special eff ect is achieved by the poet’s carefully crafted oronyms, those “strings of sounds that can be carved into words in two diff erent ways.”6 Take a very simple oronym. Th e word naksatra means “planet,” but

it can also be read or heard as two separate words, the negative particle na and the word ksatra (warrior). Th us, depending on how we carve words from the poem’s string of sounds, it can portray either the moon “who resides among the planets” or a king who does not follow the warriors’ code of conduct.

Th ese specifi c lines are by Dandin (c. 700), a poet and critic to whom we will return in later chapters.7 Here it is important to emphasize that a

is not an allegory or an insinuation based primarily on extralingual fac-tors, but a unique manipulation of language itself with the aim of making it consistently double.8 Th is manipulation very often involves the

con-struction of the utterance so as to allow it to be segmented into words in more than one way. Such “resegmentable” utterances rarely appear in Western literature. In Sanskrit poetry, however, they are numerous and follow highly elaborate patterns, often exploiting the ambiguous resolu-tion of Sanskrit’s euphonic combinaresolu-tions. Th us our opening examples only scratch the surface of ślesa.

1.2 the many manifestations of

les.a

:

a brief sketch

Sanskrit belles lettres, or kāvya, started to emerge around the beginning of the Common Era.9 During the fi rst few centuries of Sanskrit literary

production, the pun seems to have been but one among many rhetorical devices at the poet’s disposal. But around the sixth century poets began to experiment extensively with punning and bitextuality. Th us in the prose poetry of Subandhu and, to a lesser extent, his follower Bāna, ślesa be-came the major medium of long descriptive passages. Other poets were soon attracted by the possibilities of using ślesa to depict specifi c situa-tions and specifi c types of characters. In this capacity ślesa came to oc-cupy sections and even whole chapters of poems, which treated those parts of the plot that seemed particularly suitable for the use of a dou-ble language (e.g., when the heroes are disguised or confl icted). Finally, there are the full- fl edged bitextual poems dedicated to narrating together the two great South Asian epics, the Rāmāyana and the Mahābhārata.

Ślesa was a dominant literary mode not just in mainstream kāvya but also in the related inscriptional poetry, which accompanied offi cial notices of kings and served to eulogize them. It came to dominate royal inscrip-tions throughout South Asia and in more remote areas of what Sheldon Pollock has termed the “Sanskrit Cosmopolis,” such as Southeast Asia (es-pecially among the Khmer), as well.10 In par tic u lar, it was used to

shorter poems. Th ere are also ślesa verses (and possibly works) dedicated to the complementary yet antithetical relationship between Śiva and Visnu, the prominent South Asian gods, as well as the dialectic relation-ship between Śiva and his wife, Pārvatī.

Th ere are also cases of ślesa in which a single passage is able to pass for both Sanskrit and one of its Prakrit sister languages. Other ślesas are bilin-gual in the sense that two diff erent narratives in two diff erent languages are embraced in one utterance. And although ślesa was primarily com-posed in Sanskrit, it was adopted by South Asian poets writing in a wide variety of languages, including Telugu, Tamil, Persian, and Urdu.

Finally, ślesa was not limited to the linguistic medium but extended to other artistic domains, such as sculpture and architecture. Th ere are im-ages combining Śiva and Visnu, as well as Śiva and Pārvatī, which the cor-responding ślesa poetry seems to verbally iconize. Th ere are temples and other architectural buildings that include various kinds of “puns.” In the ancient South Indian port city of Mahabalipuram there is a gigantic nar-rative sculpture panel, dated to the middle or second half of the seventh century CE, that can be interpreted as a kind of visual counterpart to “double- epic” poetry. Examples also exist in dramatic works, a genre more closely associated with poetry. Several bitextual plays were composed, and actors were trained to play two roles simultaneously.

In this context it is also crucial to mention the large body of commen-tarial work accompanying ślesa poetry, the numerous lexicons and manu-als for composing it, and the vast ślesa- related discourse in the tradition of Sanskrit poetics. Ślesa is therefore much more than just a narrowly de-fi ned technical term or a specide-fi c rhetorical ornament (alamkāra). Rather, it denotes a cultural phenomenon of major proportions— a large and self- conscious literary movement. No other contrivance listed by Sanskrit rhetoricians has ever enjoyed such an extraordinary career. How can one explain the profound fascination with what is, technically speaking, a sin-gle poetic device?

1.3 what (little) is known about

les.a

living scholars have actually read a bitextual poem, and no modern scholar has seriously analyzed one. Bitextuality as a phenomenon is, simply put, off the scholarly radar.

Th e most important extant work on this topic remains a rather terse essay by Louis Renou (fi rst published in 1951 and reprinted in 1978) that alludes to the size and importance of ślesa literature without mapping it in any detail.11 A few editions of ślesa works have appeared with informative

introductions, but the vast majority of ślesa poems remain unpublished.12

Sanskrit literary historians from M. Krishnamachariar to Siegfried Lien-hard dedicate only a few pages to ślesa poetry and relegate it to the status of an oddity.13

Th e little that has been written on ślesa poetry is of a descriptive, non-analytical nature. Th is is true of introductions to printed poems, of literary histories (e.g., A. K. Warder’s monumental Indian Kāvya Literature), and of the handful of essays that directly address bitextual poems.14 Perhaps

the only exceptions are David Smith’s note on ślesa usage in Ratnākara’s Haravijaya, an article by David Shulman regarding its use in Harsa’s plays, and an article by Christopher Minkowski on Sanskrit verses that can be read from both left to right and right to left.15 But even these important

essays do not discuss ślesa works per se.

Some attention has been paid to the use of ślesa in identifying the king and the god, particularly in inscribed panegyrics.16 But beyond a generally

utilitarian approach that highlights the po liti cal benefi ts of such identifi -cation, there is very little literary analysis of these inscriptions and no study at all of the large- scale king- god bitextual poems, such as the Rāmacaritam of the eleventh- century poet Sandhyākaranandin, which conarrates the deeds of King Rāma of Bengal’s Pāla dynasty with those of the Rāmāyana’s Rāma.17 Similarly, no research whatsoever has been

car-ried out on bilingual ślesas, with the exception of a single essay by Michael Hahn.18 Nor has bitextual poetry in Telugu and Tamil been charted, let

alone studied.19 Very little, if any, attention has been paid to bitextual

works combining eroticism and asceticism, a genre that usually takes the form of collections of short poems.20

the theory and the poetic practice have not been adequately assessed.21 To

the best of my knowledge, nothing whatsoever has been written on the readership of ślesa poems.

It is important to mention that several art historians of India have be-gun to recognize the importance of ślesa in their respective fi elds. For example, there are studies of ślesa in temple architecture in general, by Michael Meister and Devangana Desai, and works on the Mahabalipuram relief in par tic u lar, most notably by Michael Rabe and Padma Kaimal.22

Th ese art historians, however, fi nd few interlocutors among scholars of Sanskrit literature and culture.

In short, Indology has yet to conceive of ślesa as a general cultural phe-nomenon that is worthy of charting and understanding in its own right. What exactly is the project of ślesa poetry? How does it stand in rela-tion to other cultural productions? And what theoretical insights can it engender? Th ese are questions that have never been asked in modern scholarship.

1.4 the anti-

les.a

bias: romanticism,

orientalism, nationalism

Th e prevalent disregard for this literary movement has partly been the result of a strong distaste for ślesa among modern scholars, both Western and South Asian. Th e vast amount of energy Indologists have invested in writing against ślesa is quite remarkable, particularly when it is compared with the relatively small amount of scholarly work that has been pro-duced about it. Take, for example, the following passage describing Sub-andhu, the author of the ślesa- dominated pathbreaking prose work, the Vāsavadattā:

were all set aside for the author’s inordinate love of profuse verbosity and dry pun.23

Subandhu is not the only ślesa poet to draw such harsh criticism. Nītivarman, the author of the KǬcakavadha (Killing Kīcaka)— one of the many important ślesa works that this book attempts to resurrect— is said to have been “not a great poet in the proper acceptation of the term, nor even a mediocre poet.” His writing amounts to “strained eff orts at mere verbal jugglery, with the result that the story is embellished out of all recognition.” Th us “his theme is slender and no attention is being paid to its really poetic possibilities.”24 Nītivarman, though, is still considered

much better than other authors of the “class of factitious compositions,” like the famous Kavirāja. Indeed, Kavirāja, the most celebrated ślesa poet, has come under severe attack. His work is fl atly decried as an “incredible and incessant torturing of the language.”25 Even harsher is the critique of

a poem of seven concurrent narratives by the poet Meghavijayagani, a work that one critic has dubbed “nothing short of a crime.”26

Th is is only the tip of the iceberg, and what is particularly interesting is that many of these comments appear in introductions to printed editions of the very poems they discuss. Th us they serve as labels warning any potential reader: “Beware! Th is is terrible poetry!” Th is approach has had an im mense and lasting infl uence on the study of Sanskrit: academic insti-tutions tended to remove ślesa works from their curricula, and scholars and readers were actively dissuaded from studying them.27

modern critics have dealt with embellishments in Indian architecture and sculpture.28

Indeed, as shown by Frederick Ahl, scholars of Hellenistic and Latin literatures tended to display a similar “discomfort with fi gures of speech that pluralize meaning.” Th ey formulized what Ahl describes as the “as-sumption of explicitness”: “ ‘classical’ texts are (or should be) sincere, spare and restrained.” When wordplays or puns suggest themselves, the critic’s fi rst strategy is to ignore them and assume that their appearance is coinci-dental. Th is strategy is meant to protect the poet, to allow him to remain classical. For if the poet nonetheless “resists explicit interpretation, he is de cadent, post- classical, or, as we like to say nowadays, ‘mannered.’ ”29 Th e

condemnation of “manner,” “style,” and ornamentation is ubiquitous. Iron-ically, even the poetry of Wordsworth himself later became subject to similar criticism.30

Th is universal approach had a unique local manifestation in the study of South Asia by serving as part of the ideology legitimizing colonialism. Th is ideology portrayed India as in decay and wild, a civilization long past its golden age and much in need of Western values. Th is master narrative of Orientalism— which Edward Said fi rst charted in general and Ronald Inden and others have demonstrated in the Indian case— was used in a wide variety of discourses on South Asian po liti cal and cultural forma-tions, including Indian literatures.31

Kālidāsa, the fourth- century Sanskrit poet and playwright, was cele-brated in nineteenth- century Eu rope as natural, simple, humane, and ex-pressive. His poetry was seen as giving voice to “the true spirit of the In-dian people” and was identifi ed with the tradition’s brief moment of glory, while later literary developments, consisting of the vast majority of what constitutes the Sanskrit corpus, were considered indicative of India’s pu-trefaction.32 It was in the context of this Orientalist narrative that ślesa

works were often characterized as a “real Indian jungle” (ein wahrer in-discher Wald) and their authors dubbed “no better, at the very best, than . . . specious savage[s].”33

view that “little occurred in Sanskrit poetry that was really new after Kālidāsa[, when] poetry grew convention ridden and unnecessarily diffi -cult [and writers] seem . . . to be lacking in sensitivity.”35

Th is is not to say that the Orientalists have entirely invented a canon of kāvya, with Kālidāsa at its center. Representatives of the tradition itself— theoreticians, poets, compilers of anthologies, and commentators— all regard Kālidāsa as one of kāvya’s dearest sons, quite possibly its preemi-nent author. Likewise, the notion of a lost golden age in itself is not wholly alien to the tradition. Th e poet Subandhu, in a famous verse, bemoans the loss of kāvya’s “nine gems” (which probably included Kālidāsa) and the rise of the lesser “modernists.”36 More specifi cally, the tradition

oc-casionally raised its own concerns about ślesa and similar devices in comparison with the poetic ideal of evoking emotional “fl avor” (rasa). Th us some theorists may have considered ślesa poems part of an inferior category of poetry when compared with poems informed by models such as those provided by Kālidāsa.37 Still, the Orientalist system of

canoniza-tion within kāvya is far removed from the traditional view. Th is is as true of the exaggerated attention to Kālidāsa as the last worthy poet— the San-skrit tradition, by contrast, hails numerous subsequent poets— as it is with respect to the uncompromising criticism of ślesa. Th e poetry dis-cussed in this book was widely read, intensively commented on, and in-cessantly copied before the colonial era. Poets from Subandhu in the sixth century to Kavirāja in the twelfth and Śesācalapati in the seven-teenth took im mense pride in their bitextuality, and many critics hailed ślesa as the hallmark of learnedness and poetic power. Even theorists like Ānandavardhana (c. 850), who argued that poetry should evoke emo-tional “fl avors,” did not abstain from composing ślesa. Th us even if we fi nd some ambivalence in the emic approach to ślesa, it is nothing like the adamant dismissal of it in the last 250 years to be found in the etic.

So blinding was the impact of this bias that the authoritative Sanskrit literary histories still fl atly deny the very existence of ślesa poetry in the fi rst millennium CE.38 Th ese histories relocate bitextuality to the late

often still the case that merely to mention ślesa poetry is to off end the taste and sensibilities of a good number of scholars.

1.5 is

les.a

“natural” to sanskrit?

Th e same scholars who view ślesa poetry as unnatural also paradoxically see it as natural to the Sanskrit language. Indologists have time and again explained the unique phenomenon of ślesa poetry by the par tic u lar “in-nate” features of Sanskrit. For example, it has been repeatedly argued that Sanskrit has a rich vocabulary and a wealth of synonyms; it allows for great freedom in creating epithets; it possesses manifold ways of express-ing the same idea; it lends itself to ambiguity because of the diverse ways in which its compounds can be analyzed; its writing system is phonetic and thus generates more homonyms; its phonemic strings can be seg-mented in various ways; and the resolution of its euphonic combinations lends itself to ambiguities. Th us there is a consensus that only “a language as fl exible as Sanskrit” could have yielded a phenomenon such as ślesa poetry. En glish, on the other hand, would “not support the burden of si-multaneous apprehension.”40

Although some of these observations are accurate, both the signifi cance attached to them and the conclusions drawn from them are fl awed. It is one thing to clarify the conditions of possibility that reveal how ślesa works, and an altogether diff erent thing to invoke these conditions as an explanation of why it exists. Th e substitution of the “how” for the “why” has proven all too con ve nient for a variety of researchers.41 It negates the

need to investigate a given poet’s motivation, at a certain time and a cer-tain place, to compose a poem that simultaneously narrates the two prin-cipal epics of his culture. Th is line of argumentation, then, is determinis-tic: it views language and literary culture as frozen, ahistorical entities and does not consider poets, critics, and readers as historical agents. It thus ignores the historical pro cesses that made Sanskrit fl exible and overlooks the possibility of other languages becoming ślesa friendly.

resegmentation (oronyms) because word boundaries have no physical re-ality in speech and, at least in antiquity, were not represented in writing.42

Finally, all orthographies are potentially ambiguous, whether because they are shallow (that is, wholly transparent, as in Sanskrit) or precisely be-cause they are deep (as in En glish). Even in the absence of an objective mea sure of ambiguity, I see no reason to assume that one language is in-herently more ślesa friendly than another.43

Indeed, there are ślesas and ślesa- like devices in other languages, even if on a smaller scale. To appreciate the sheer load of multivalent punning and ambiguity that En glish can carry, one needs only to glance at Finnegans Wake, at an advertisement in any English- language magazine, or even at a children’s rhyme, characterized by “imperfect” puns: “Do you carrot all for me? / My heart beets for you / With your turnip nose / And your radish face / You are a peach. / If we cantaloupe / Lettuce marry, / Weed make a swell pear.”44 Th e extent to which this kind of multivalent

punning is possible through the use of ślesa in other South Asian lan-guages is particularly telling. Th e Tamil ślesas, for instance, are often based on phonetic, morphological, and syntactic traits that are specifi c to the language, and the same is true of Telugu. At least one poet, Pi]gali Sūranna (late sixteenth century), explicitly called attention to the fact that although some of his bitextual techniques are borrowed from San-skrit, many others are unique to Telugu.45 Moreover, in both of these

languages the composition of ślesa was a major cultural phenomenon that began around the beginning of the seventeenth century and was car-ried with full force into the nineteenth and even the twentieth century.46

So if Tamil and Telugu— which do not belong to the same family of lan-guages as Sanskrit, but do share with it a similar cultural milieu— possess their own arsenal of ślesa tools and demonstrate a long- standing tradi-tion of bitextual poetry, then perhaps it is not the nature of language that determines such traits, but a historically traceable use and even modifi -cation of the language by its agents. Perhaps, then, “the special advan-tages aff orded by Sanskrit” could also be enjoyed by other languages.47

nu-merous works of indigenous lexicographers, which include long lists of synonyms, polysemic words, and monosyllabic signifi ers. Th e uncritical assumption of many is that these works simply refl ect the language’s “nat-ural” state of aff airs. Th is assumption overlooks the important possibility that lexicographers are agents of change who participate in the pro cess of shaping their tongue, or, more generally, that a culture’s awareness of its language has signifi cant consequences for its use.

It is well known that the study of language— grammar, phonetics, syn-tax, and lexicon— was uniquely central to Sanskrit culture. Th e grammar of Pānini, to give the most obvious example, is unpre ce dented in its ac-curate description and its complex and elegant metalinguistic conceptual-ization of vast linguistic phenomena. Th e existence of such a sophisti-cated tradition of grammar and the fact that a mastery of it was a basic requirement in elite education clearly infl uenced and changed the use of language. One very obvious example is the fact that Pānini’s descriptive account of the Sanskrit language quickly became prescriptive. But there are less obvious implications, some of which have to do with ślesa. Con-sider Pānini’s rules of euphonic combinations (sandhi). Phonemes are dif-ferently pronounced in diff erent contexts in all languages, and euphonic glides and assimilations are a universal phenomenon. But Sanskrit alone came to possess a near- perfect description of these that was studied and memorized by every educated person. It is this intimate knowledge of the language, rather than its “natural” characteristics, that uniquely empow-ered Sanskrit poets to exploit the language’s phonetic ambiguities. Like-wise, the fact that South Asian orthographies all represent euphonic com-binations, and that words are written diff erently in diff erent phonetic contexts— supposedly making written Sanskrit more ślesa friendly— is by no means determined by the language’s phonetics, but is precisely the re-sult of the grammarians’ investigation of its phonetic structure. Th is, then, is a clear example of how the history of examining and analyzing the lan-guage changed its actual usage, in this case, the way it was written.

played with names and epithets, and fl exed and expanded beyond recog-nition the expressivity of language.

Th is also raises the question of the so- called naturalness of the lexicon. How is it that the word rājan (king) is also listed by the lexicographers to mean “moon”? Is it an arbitrary characteristic of Sanskrit, or is it the result of an incessant and conscious meta phorical identifi cation of the two enti-ties? How is it that the various thesauri list as many as twenty meanings for the word hari (sun, moon, monkey, horse, Indra, Visnu, wind, fi re, yel-low, and so on)? Are we to believe that Sanskrit simply is so multivalent, and that the thesauri only refl ect this quality faithfully, in its “natural” form? And what of the monosyllabic lexicons, wherein syllables like ka are listed to mean Brahma, Visnu, love, fi re, wind, death, sun, soul, king, knot, bird, mind, body, time, cloud, hair, light, word, wealth, happiness, water, and so on, few of which are recorded outside poetic texts? Are these all “natural”?

As we shall see in chapter 5, the massive appearance of these lexicons and thesauri coincides with the boom of ślesa poetry, and this was not coincidental. Quite a few of these wordbooks and their sections were spe-cifi cally designed to cater to the needs of ślesa poets and readers. Some of them even have the word ślesa in their title, while others were composed by ślesa poets themselves. Insofar as lexicographers merely refl ected a re-ality, they refl ected the conscious eff ort of poets to expand and reinvent their language. But, as I argue later, there is good reason to believe that they too were active agents in this pro cess.

Th e idea that the linguistic construct found in grammars, lexicons, and poems refl ects some kind of natural state of aff airs and the thought that Sanskrit as we know it— a language whose very name means “the Refi ned”— is a natural product do not stand to reason. Th e state of a lan-guage, any lanlan-guage, represents the active awareness of its users.48 It was

the users of Sanskrit who produced what Daniel Ingalls has called the “well- cut and tempered tools” that James Joyce did not have at his disposal when he composed Finnegans Wake.49 Th ere is no inherent or natural

rea-son why En glish writers could not have crafted tools similar to those used by Sanskrit poets, had they so desired. After all, poetry is often not “natu-ral” to the language it is written in, nor should it necessarily be. Poets typi-cally write against their language, breaking conventions, transgressing grammatical rules, and saying what could not have been said ordinarily.50

1.6 toward a history and theory of

les.a

Th e apparent contradiction between the notion of ślesa as unnatural po-etry, the product of a long period of de cadence, and the view of it as re-sulting from the natural characteristics of the Sanskrit language should not blind us to the important similarity between the two ideas. In eff ect, both serve to dehistoricize ślesa literature. Th is is perhaps more easily de-monstrable with the latter, deterministic view, but it is equally true of the Orientalist and Romantic approaches. Th e axiomatic position that, on the one hand, real poetry expresses a nation’s character and, on the other, that only “the earliest poets of all nations wrote from passion excited by real events” (that is, naturally), whereas their followers imitated them me-chanically (that is, unnaturally), eliminates the need for serious historical explanations.51 A nation’s character, according to such Romantic notions,

is an unalterable essence, and the cycle of a short moment of insightful revelation followed by a long period of decay is ostensibly fi xed and uni-versal. All that one has to do is to discover the poet who best expresses the spirit of the nation one wishes to study (or control), and the rest will fall into place. Th ere is no need to study later poetry of the ślesa type, given the predictability of such de cadent growth.

Th us instead of writing about ślesa and explaining its evolution, Sanskrit literary historians have written it off and explained it away. Th e early evolu-tion of this amazing literary experiment has been negated, an act that has also served to deny the signifi cance of its later appearances. We are there-fore asked to believe that poems such as the celebrated RāghavapāndavǬya of the twelfth- century poet Kavirāja that perform the almost inconceivable task of narrating the Rāmāyana and the Mahābhārata simultaneously ap-peared out of the blue. According to this view, they were not an outcome of historical developments integral to the South Asian world and had neither precursors nor infl uence on future poets. It is clear, then, that the only way to remedy this amazing neglect and explore the purpose and meaning of the ślesa phenomenon is through charting its evolution. Th us the belief that in order to theorize one must fi rst historicize governs the plan and structure of the present book.

without its benefi ts and that it will allow the reader to experience, fi rst-hand, some of these unique poems without losing sight of their context.

Chapters 2 through 5 provide the main historical account of bitextual literary production. Chapter 2 discusses the fi rst vast experiments with ślesa in the prose works of the sixth and seventh centuries. Chapter 3 ex-amines how poets and playwrights of the seventh and early eighth centu-ries turned ślesa into a plot device. Chapter 4 explores how ślesa was rein-vented as the medium of full- fl edged double- epic poems in the eighth and early ninth centuries. Chapter 5 charts the “bitextual boom” of the second millennium and the reasons that may have led to such a boom and to the continued effl orescence of ślesa in the late medieval and early modern periods. At the center of each of these chapters stands a close examina-tion of the work of one representative author. In chapter 2 it is Subandhu, the prose master and the great pioneer of ślesa. Chapter 3 looks at the work of Nītivarman, who masterfully employed ślesa to portray the dis-guised protagonists of the epic. At the heart of chapter 4 is the fi rst extant Rāmāyana-Mahābhārata poem by Dhanañjaya. Chapter 5 examines the RāghavapāndavǬya by the twelfth- century Kavirāja (King of Poets), the genre’s most celebrated work.

In chapter 6 I look at the same history from a diff erent perspective, ex-amining the possibilities and dangers of reading ślesa from the standpoint of authors, critics, and readers of Sanskrit literature. Specifi cally, I explore the things that can go “wrong” with reading practices that involve this device. Th at chapter also continues the chronological trajectory of the book, for it focuses on a group of early modern commentators who, em-powered by ślesa, produced textual exegeses that seemed unforeseen or even unwelcome to some of their fellow readers. Here too I focus on a representative work: Ravicandra’s controversial reading of Amaru’s fa-mous collection of erotic poems (the Amaruśataka) as being also, if not primarily, about dispassion.

W

hen and why did the fascination with ślesa begin? Historians of Sanskrit literature argue that poetry written primarily in ślesa began to appear only in the second millennium CE. At the same time, they maintain that before the late effl orescence of works that were mainly bitextual, ślesa always enjoyed a prominent place in the poetic tool kit of kāvya.1 Both views are erroneous. In this chapter I tacklethe latter notion, namely, that, as an ever- popular device among Sanskrit poets, ślesa has always existed. Th e bulk of this chapter is dedicated to an exploration of a pioneering work by the sixth- century author Subandhu, the fi rst writer to use ślesa as a major literary vehicle. I analyze Subandhu’s work, his use of ślesa, and why it became the centerpiece of a new prose style. Th e chapter concludes with a brief discussion of the response to Subandhu’s experiment, particularly that of his best- known successor, Bāna.

2.1 the birth of a new kind of literature

In early Sanskrit poetry ślesa was rarely used. Vālmīki’s Rāmāyana, for example, is traditionally regarded as the “fi rst poem” (ādikāvya) and dates to the beginning of the Common Era. But ślesa is virtually absent from the Rāmāyana, despite the presence of many tropes and fi gures of speech.2

Ślesas begin to appear in the fi rst extant “grand poems” (mahākāvyas) and plays of the second- century author Aśvaghosa, but even in the works of the fourth- century poet and playwright Kālidāsa they remain few and far between.3 It is only in the verse of the sixth- century author Bhāravi

corpus of inscribed panegyrics (praśasti), whose language closely mir-rors that of courtly kāvya. In Rudradāman’s Junāgarh inscription (c. 150 CE) there is only “a faint attempt at slesha [ślesa],” and even in the highly ornate panegyric of Samudragupta, inscribed on the Allahabad Pillar by the poet Harisena at the end of the fourth century CE, it is rarely used in comparison with other poetic devices.5 It is only in the second half of

the fi rst millennium CE that ślesa becomes a major mode in inscribed poetry.6

Th is is not to say that before the sixth century CE Sanskrit poets were totally disinterested in ślesa- like devices. Particularly relevant here is the rhyming device called yamaka, or “twinning,” where phonetically identi-cal duplicates are repeated, each time with a diff erent meaning. Aśvaghosa and his followers began to experiment with twinning early on and did so in ways that are highly reminiscent of later ślesas.7 First, the techniques

that underlie such rhymes are identical to those used in crafting ślesas, including resegmentation. Second, poets allowed twinning to dominate long sections or even entire poems, just as they later did with ślesa. Th us the anonymous Ghatakarpara (a short, twenty- verse poem that is be-lieved to have preceded Kālidāsa) is marked by twinning throughout, and Kālidāsa’s Raghuvamśa contains a lengthy section in which each verse contains a pair of verbal twins.8 Finally, as with ślesa, poets tended to use

yamaka meaningfully. For instance, Gary Tubb demonstrates that Kālidāsa’s twinning amplifi es the thematic and psychological concerns of the Raghuvamśa.9

But the early tendency of poets to repeat such homophonous twins only underscores their relative indiff erence to using them with both meanings intended simultaneously. Th e initial preference for yamakas had partly to do with the fact that such rhymes were originally associated with versifi ed poetry. Sanskrit kāvya originated in verse form. Th e famous moment of kāvya’s conception in the Rāmāyana is really described as the invention of the śloka meter.10 It hardly seems a coincidence, then, that the term

ya-maka is almost as old as the earliest extant kāvya, and that early discus-sions of yamaka all include a classifi cation of this device according to its metrical position.11 While yamaka was initially associated with stanzaic

poetry, large- scale experiments with ślesa are closely linked to the later ap-pearance of kāvya in prose.12 Th e very designation “ślesa” is recorded for

One must be cautious, of course, when asserting that a Sanskrit author or work was the fi rst to set a new trend, given the likely loss of earlier ma-terials and the im mense diffi culty in dating what has been preserved. In-deed, little is known about Subandhu, and scholars can only deduce with certainty that he composed his Vāsavadattā before 608 CE.14 Subandhu

certainly did not coin the term ślesa, for he uses it as already established, and he may well not have been the fi rst to compose an entirely prose kāvya work. Stylized prose passages begin to appear in Sanskrit inscrip-tions from the second century CE onward and in a variety of primarily Buddhist works from this period. Th ese include the anonymous Lalita-vistara, a work from the fi rst or second century CE that narrates the life of the Buddha, and Āryaśūra’s Jātakamāla, a poetic rendition of the Bud-dha’s previous lives that is dated to the fi fth century.15 Prose, we should

also note, is more diffi cult to memorize than verse, which makes the loss of early works quite possible.16

Nonetheless, there are compelling reasons to believe that Subandhu’s prose style, with ślesa as its centerpiece, was a groundbreaking innova-tion. Th e very fact that his Vāsavadattā was preserved is a strong indica-tion of this. If prose works are more diffi cult to transmit, and if earlier works did exist but were not handed down to us, then perhaps there was something special or novel about the Vāsavadattā that ensured its sur-vival. Note that Subandhu’s work also fared far better in its preservation and “shelf life” than those prose works that followed it. Of Sanskrit’s triad of prose masters, which includes, in addition to Subandhu, his successors Bāna and Dandin, Subandhu’s work seems to have been transmitted and studied most widely. For example, more than twenty commentaries on the Vāsavadattā exist, and the commentators often explicitly declare that it was Subandhu’s ślesa that attracted them to write about his work.17 Th ese

clearly outnumber the commentaries on the prose works of Bāna and Dandin combined, and the prose of Dandin, at least, has reached our hands in a highly fragmented form.18

More signifi cant than the implications of the Vāsavadattā’s longevity is the author’s own awareness of his innovative style, evident in the work’s signature verse:

I amassed a wealth of craft

constructing a confi guration that consists of ślesa

in letter after letter.19

Th is verse is the earliest known record of the term ślesa, but its importance goes well beyond that: what we have here is the proud unveiling of a new literary form. After all, if works saturated by ślesa had been standard in Subandhu’s days, he would have had no cause to boast about his use of the device. Indeed, it is only here, while claiming credit for a work that con-tains ślesa “in letter after letter,” that our author reveals his identity, as if to ensure the association of his name with this new style of punning.

Note that Subandhu’s statement is exaggerated. Although ślesa is cer-tainly the most important literary vehicle in the Vāsavadattā, it is not the only trope that marks his distinctive style. In fact, this verse displays several other key elements of his innovative prose. Its fi rst compound contains a ślesa: Sarasvatī is a river and also the goddess of poetry, yielding Subandhu the lucidity of her water and words. Th is ślesa is then followed by a play on the author’s name, Subandhu, which is glossed by the echo compound sujanâika- bandhu (“the sole soul mate of people of taste”).20 Such plays on

names and echo eff ects are very common elsewhere in his work. Finally, the second half of the verse supplies a tiny sample of Subandhu’s tendency to use long alliterative compounds, which involve no ślesa. But for its fi nal word, the entirety of the verse’s second half is a single, reverberant com-pound word: praty- aksara-ślesa-maya- prabandha- vinyāsa- vaidagdha- nidhir nibandham. In content and form, then, this stanza inaugurates the main components of an unpre ce dented literary style.

was its eff ort to help Princess Vāsavadattā locate this prince, whose name, Kandarpaketu, was disclosed in her dream. Upon hearing this, the over-joyed Kandarpaketu introduces himself to the parrot, who off ers to lead him to the princess. Th e two lovers unite and use a magic horse to elope back to the forest. Th ere they enjoy only a cruelly short- lived union, for the princess disappears the following morning. Confused and desperate, Kandarpaketu is about to drown himself in the ocean when a voice from heaven promises a reunion with his beloved. After additional months of wandering, he comes across a stone resembling Princess Vāsavadattā, and when he touches it, the stone transforms back to the living princess. She then narrates her part of the story to him— how she had gone to fetch him food and got caught between two hostile armies. Fleeing them, she dis-turbed an irritable sage who turned her into stone. Once re united, the two live happily ever after.

Th is plotline is strikingly novel for the conventions of kāvya.21 It is,

however, reminiscent of kathā literature— a large pool of tales and fables in Prakrit, epitomized by the famous Brhatkathā (Th e Vast Story) of Gunādhya, a work that is now lost. It seems that for Subandhu, a major objective was to import Gunādhya’s world of talking parrots, magic horses, and heavenly voices into the high literary form of kāvya. Just as Aśvaghosa and Āryaśūra rendered the pop u lar tales of the Buddha into poetry, and Kālidāsa rendered stories from the epic and Purānas into or-nate verse, Subandhu aimed to rework kathā materials into the cosmo-politan and prestigious medium of Sanskrit belles lettres. Like the earlier breakthroughs of Aśvaghosa and Kālidāsa, Subandhu’s poetic reworking of the kathā genre resulted in a new and distinctive literary form. As Louis Gray noted a century ago, with the Vāsavadattā Subandhu began “a new literary genre in India.”22

Existing scholarship on the Vāsavadattā off ers us a variety of possible labels for its genre. Th e work is often classifi ed as a novel, although the plotline and the style of Subandhu’s prose are far removed from any speci-mens of this genre.23 Gray and others were probably right to suggest that

the work resembles more a romance by John Lyly than a novel, although this Eu ro pe an example explains little about the actual features of Sub-andhu’s prose and the role of its proclaimed cornerstone, ślesa.24 Others

At any rate, the quest for a genre label is clearly superfi cial if it is not backed by a detailed and careful analysis of the work’s form and contents. We should note that the structure and themes of Sanskrit prose in general are largely uncharted in emic poetic theory26 and have mostly been

ig-nored by those modern scholars who dismiss kāvya in prose as “a real Indian jungle.”27 Robert Hueckstedt’s study of Bāna stands out for its

seri-ous analysis of Bāna’s techniques of sentence building, verb placement, descriptive structure, and syllabic texture. He convincingly argues that Bāna’s prose, far from being a chaotic jungle, is a “highly sculptured gar-den.”28 But the work of Subandhu, Bāna’s greatest infl uence, still awaits

analysis, and very little attention has been paid to the various innovative elements of the Vāsavadattā— its plot, its use of alliterative compounds, and its dominant literary vehicle, ślesa. In short, Gray’s century- old claim that Subandhu invented a new genre remains unsubstantiated.

2.2 the paintbrush of imagination: plot and

description in the

vsavadatt

Th e Vāsavadattā is comparable in size to a longer short story or a short novella.29 It contains no formal divisions but can be divided into four

Th e third portion of the work consists entirely of the events of the fol-lowing night, with a particularly lengthy description of the nightfall itself. Once the moon is out, Kandarpaketu leaves for Vāsavadattā’s city, fi nds her home, and meets the princess, the beloved of his dream. Th e new couple wastes no time: to foil the plan of Vāsavadattā’s father to have his daughter wed by dawn, they elope on horse back before the momentous night is over. A fourth fateful night determines the events of the work’s fi nal quarter. Passing through a nightmarish and gruesome cremation ground, the couple rides into the dark Vindhya Forest, where they spend the hours of darkness together. Kandarpaketu is late to rise, and when he does wake up, Vāsavadattā is nowhere to be seen. Her disappearance leads to his aborted suicide attempt and his subsequent successful search for his beloved.

Vast portions of the text are devoted to lengthy descriptive passages, dedicated to the heroine and hero and to a variety of natural entities such as nighttime, spring, Mount Vindhya, and the ocean. Subandhu is regu-larly accused of neglecting the plot and criticized because the “slender thread of his narrative is lost beneath his numerous descriptions.”30

But although he is clearly invested in the work’s descriptive portions, Subandhu is not unmindful of the plot. Th e Vāsavadattā is carefully built around the parallel versions of the shared dream experienced by the hero and the heroine— one narrated directly, the other through the parrot’s story- within- a-story—and prudently withholds the mystery of Vāsavadattā’s disappearance until the heroine’s explanation at the very end. Th us for every major event, we fi rst see things through Kandarpake-tu’s eyes and then get Vāsavadattā’s version. It also seems that special at-tention is devoted to creating parity between pairs of actors and pairs of actions, such as the pairing of Kandarpaketu’s wise friend Makaranda and Vāsavadattā’s shrewd companion Kalāvatī,31 that of the parrot and

Tamālikā,32 or the parallel episodes of lovesickness33 and the dual escapes

to Mount Vindhya.34

moon fi nally makes an appearance and lights the way for Kandarpaketu’s journey to his beloved. Th is extended passage heightens the erotic inten-sity of the narrative and creates an acute anticipation of the rendezvous of the hero and the heroine. Consider, likewise, the potential suspense in the poet’s detailed meditation on the qualities of the seashore, with the in-tensely erotic activities of its wildlife, and the ocean, with its ferocious waves, just as Kandarpaketu, separated from his beloved and having re-solved to die, is about to submerge himself in the water.

Th e very syntax of Subandhu’s long descriptive sentences adds an ele-ment of suspense. While retaining the normal Sanskrit word order of subject- object- verb, Subandhu often inserts large numbers of modifi ers, severing the subject from the object and the verb. Alternatively, he may begin a sentence with a mammoth adverbial phrase consisting of a long chain of locative absolutes and continue with a set of complex adjectival clauses before disclosing the object and the verb, into which the subject is fi nally built. An extreme example is the work’s longest sentence, contain-ing Kandarpaketu’s dream, where the verb apaśyat (he saw) and its object kanyām (a young girl) come at the very end of eighty- six lines that depict the nocturnal setting and then focus on a description of the physical at-tributes and many charms of Vāsavadattā.35

Moreover, Subandhu’s elaborate and intricate descriptive sentences with their artifi cial syntax actually do advance the plot. By way of example, consider a typical sentence of twenty- fi ve lines depicting Vāsavadattā’s house when Kandarpaketu sees it for the fi rst time. Th e pronoun “he” and the gerund praviśya (having entered [town]) are given at the outset, along with the adjective katakaika- deśe vinirmitam (standing in one part of the capital), but the actual object “house” and the verb “saw” are withheld till the end. In between is enclosed a lengthy portrayal, moving from an outer wall with its protruding fl ags to streams in the garden, adjacent mansions in the compound, and, fi nally, various aspects of the house itself. Th is con-centric modifi cation of the residence, which has yet to be identifi ed, thus imitates the course of Kandarpaketu’s movement and gaze, and the sen-tence, with its almost unbearable gap between gerund and verb, slowly moves the hero toward the much- anticipated union with his beloved.

is initially unclear. Gradually it becomes evident that it is the chatter of Vāsavadattā’s female friends, although this is ascertained only at the end: “Hearing the love- invested chitchat of the ravishing maidens, Kandarpak-etu, accompanied by Makaranda, entered her house.”36 If the previous

long sentence narrated the visual impressions as Kandarpaketu neared the house, the series of shorter utterances depicts an auditory veil that he passes through at its threshold.

Although Subandhu’s descriptions are by no means inimical to the plot, they do have a life of their own, characterized by constant fl uctuation and intricate structure. In addition to mixing long and short sentences, de-scriptive passages also oscillate among a host of semantic and musical verbal patterns. Th ere is a continuous variation within and among meta-phoric, alliterative, and punned units of depiction, and a similar fl uidity characterizes the logical structure. Hueckstedt, for instance, has noted that Subandhu is not bound by the standard foot- to- head method of por-traying human characters, and we fi nd a considerable variety of upward and downward descriptive movements.37 Likewise, the pace of

descrip-tion can change dramatically, with slow modescrip-tion used for some objects or scenes and a kind of fast- forward for others. Th ink, for example, of the hardly mentioned daytime hours between the story’s momentous nights, the horse back journey from the cremation grounds to the forest that passes “in a wink,” and the months of Kandarpaketu’s loneliness that lapse within the span of a brief sentence at the end, when the work’s overall pace accelerates signifi cantly.38

Th us even before we have examined his imagery and vocabulary in de-tail, it is apparent that Subandhu presents his readers with a highly com-plex descriptive arrangement. Modern critics of the work have been right to see this arrangement as the core of Subandhu’s creation, although they have failed to appreciate its poetic qualities and understand its multifac-eted relationship to the plot. Subandhu may have designed his complex descriptive language as the only verbal medium poetically fi t to represent the magical and fantastic world of kathā literature. Indeed, the author’s focus on descriptive language may be consonant with a major narrative choice of the work.

To understand how this is possible, we have to compare the work with a significant intertext. Scholars have neglected to notice that the Vāsavadattā fi ts into a large subset of tales featuring a shared dream, a motif studied by Wendy Doniger O’Flaherty.39 Of these, the story of Usā

Bāna, was raped in her dream by a handsome youth, although in some versions the dream consists of consensual lovemaking. Th is dreamed sex-ual encounter leads to profound personal and cosmological consequences. Madly in love with the molester or lover from the dream, Usā falls ill. Her friend Citralekhā, “the Portraitist,” is called to the rescue. Citralekhā pre-pares sketches of the entire pantheon of gods, among whom Usā recog-nizes her beloved. It is Aniruddha, grandson of Krsna and son of Prady-umna, the god of love. Citralekhā miraculously causes Aniruddha to materialize through her sketch, and the lovers secretly unite in the palace of Usā’s father. When the demon discovers his daughter’s secret lover, he promptly jails him. Krsna and Pradyumna intervene to kill the powerful Bāna, thereby restoring the cosmic balance and allowing the lovers to re unite.40

Th e similarities between the Vāsavadattā and Usā’s story are clear. Both feature an erotic dream encounter that leads to a love aff air in wak-ing life, and in both the heroine miraculously fi nds the hero, who secretly joins her in her palace. In each story the lovers separate before reuniting in the end. Lest these similarities be lost on readers, Subandhu explicitly compares Kandarpaketu with Aniruddha and Vāsavadattā with Usā and unmistakably plants a portraitist named Citralekhā in Vāsavadattā’s reti-nue.41 Th ese points also highlight crucial diff erences between the two

nar-ratives. Subandhu dispenses with the cosmic struggle between the gods and their enemies that frames the Usā- Aniruddha story. Accordingly, the fi nal battle between Aniruddha’s party of gods and Usā’s father’s army of demons is utterly transformed in the Vāsavadattā’s parallel battle scene. Perhaps with Usā’s story in mind, Vāsavadattā initially mistakes the sol-diers she sees in the forest for her father’s rescue team or Kandarpaketu’s loyalists. Th en she realizes that she has inadvertently stepped between two warring forest tribes and escapes the scene, only to be cursed by an irritable sage.42 Th us whereas Usā of Bloodtown (Śonitapura) re unites

with Aniruddha thanks to the intervening troops, an interfering war sets Vāsavadattā of Bloomtown (Kusumapura) apart from Kandarpaketu. In-deed, while Aniruddha’s rape of Usā makes the gods’ plan to kill Bāna pos-sible, in the Vāsavadattā it is Kandarpaketu’s desperate love for Vāsava-dattā that forces the heavens to comply and promise a reunion.

a dream, they do not hesitate to leave their kingdoms behind and attempt to take their own lives.43 Commonsensical, pragmatic approaches are

re-jected outright: think, for example, of Makaranda’s po liti cal advice to the lovesick, bedridden prince, which is fl atly refused.44 Th e lovers are only

rewarded for seemingly unreasonable behavior. Vāsavadattā writes in her love note to Kandarpaketu that she is unsure of his aff ection because she felt it “only” in a dream.45 But oddly enough, her message, entrusted to a

search team that was given no directions, soon lands right in the hands of the overjoyed Kandarpaketu. Kandarpaketu, for his part, miraculously runs into the parrot and then into the stone image of Vāsavadattā despite wandering aimlessly. Th en there is the heavenly voice that prevents his needless suicide. Th is intervention comes as he is in the midst of shark- infested waters, but even the cruel sea monsters become friendly to the hero in love.46 Finally, when Kandarpaketu recognizes his lover in the

rock, even hard stone yields to his loving touch. Subandhu clearly and consistently privileges the internal love vision of the dreamer over con-ventional reality.