207

ICT, development and media

Mark Borg

Introduction

Technology is an inescapable reality that infiltrates every part of our lives. It usually dictates how we do things and undoubtedly im-proves our lives by minimising our mundane tasks, allowing us more time to dedicate to more significant activities. The last century has seen technology advancing in leaps and bounds, because of the sili-cone chip. For instance, in just a decade, the cell phone jumped from our science fiction screens into the hands of millions of consumers with an unprecedented hunger for the technology. Prices dropped dramatically in a very short period to quickly make it one of the most affordable electronic consumer products on the market.

Not quite as flamboyantly as the cell phone, the computer has gone through a comparatively quiet revolution in design. It took less than half a century for a computer that once filled a room to come down to a size that now fits a laptop. With this came advancements in programming, the Internet, audio and video formats and peripherals.

While the developed world took the lead in these technological advancements, the developing world seemed to be watching from the side. But not just watching—many developing countries realised the potential of the technology. Strategies that before were unaffordable had suddenly been made affordable, owing to the versatility of the Internet.

Like everything new, the Internet initially met considerable resis-tance, more so since it is a medium for all kinds of information, in-cluding material that is considered ‘unsavoury’ by sectors of the community.

But precisely because it is a medium for all kinds of information, the Internet made economic sense. Through a single medium, we could suddenly communicate information on health, agriculture or

business, pass on news, educate students, and send mail to individuals. All of these in the form of text, pictures, movies, music and voice messages. It almost seemed that the Internet was as vast as the imagi-nation of the people who were using it.

This was quickly recognised and any initial resistance faded away as people began to understand the benefits it could bring to their work and their lives.

There was a push, especially by international development agen-cies like the United Nations Development Program (UNDP), to use the technology for development purposes. Former UNDP administra-tor Mark Malloch Brown said, ‘ICTs, especially the Internet, are both about stimulating wider participation, exchanging experience, com-municating ideas, transmitting knowledge, sharing new findings and best practices and facilitating the development of communities of practice and new modes of cooperation’ (Brown, 2001). However, the focus had to shift from the technology, and trying to find ways to use it, to development problems and assessing whether the technology could be a solution (or part of a solution) to some of these problems. That is, the focus should be on people and the developmental uses of the information and communication technologies, and not on the tech-nology per se. It was realised that, unfortunately, not everyone was benefiting from ICTs to the same extent. In fact, a ‘digital divide’ had been created.

The digital divide

The Digital Divide has been equated to the gap between the ‘haves’ and the ‘have-nots’ in the world, the rich and poor. Now peo-ple are falling into another two categories, referred to as the ‘knows’ and the ‘know-nots’. It is not a coincidence that the ‘haves’ and the ‘knows’ and the ‘have-nots’ and the ‘know-nots’ are usually the same categories of people, for a very simple reason: wealth gives one access to knowledge and knowledge gives one access to even more wealth.

The Digital Divide can be defined as the gap between those able to benefit from digital technology and those who do not (Hammond, 2001). This refers not only to those who have direct access to

technol-ogy, but also to those who are actually helped by

op-timal use of it for their own and their community’s benefit.

With the advent of the Internet, amazing new opportunities pre-sented themselves to Pacific Island countries. Here was an opportunity to overcome some of the barriers that have plagued island nations, such as distance, isolation and dispersal of their populations.

A study on digital divides in the Pacific was published in 2004 by Dirk Spennemann. He found that each of the Pacific Island coun-tries was mentioned by more than a million pages on the web, with Samoa, Fiji and Guam the most frequently mentioned. However, less than 1 per cent of all pages about Pacific Island countries are hosted on their own domains. He concluded that the divide was so great that it could not be bridged with the resources available to the countries at that time. He suggested that the divide be perceived as being two-fold: access to reliable and affordable technology, and information literacy.

A component of this digital divide is the dependence of the South on the North for technology. To reduce this dependence, some suggest that developing countries ‘should integrate both production and use, and draw on the substantial ICT capabilities existing in the South through bilateral, regional and inter-regional cooperation’ (Joseph, 2005).

through the use of radio and solar technologies. Thus, people in these localities were able to send and receive email before they even had telephones and electricity. The delivery of Internet has been able to provide Internet at a low cost, improve communications, bridge the distances that exist in the archipelago and therefore assist in nation building following the upheavals that the country has experienced.

However, despite these innovations, one cannot ignore the huge obstacles facing the Pacific in its development of ICTs.

Obstacles to ICT development in the region

The Pacific has recognised that there are a number of obstacles limiting the development of ICTs in the region, that is, the limited and unequal access to communications technology, high costs of equip-ment and services, insufficient telecommunications bandwidth, low investment in networks and the outdated and absence of sufficient regulatory frameworks at the national level (Pacific Islands Forum Se-cretariat, 2006). These obstacles, of course, are not confined to the Pa-cific. The international discourse on ICTs lists the same obstacles to ICT development in all continents. However, the Pacific does offer extremes of some of these obstacles and these need to be overcome before people living in developing countries can maximise the bene-fits of this technology.

Prices / rates

many governments have dramatically decreased, or even removed, du-ties and taxation on computer equipment and products (including pe-ripherals and software). One way to overcome the barrier of the high costs of computer equipment is to set up telecentres, that is, commu-nity centres that offer Internet access for a small fee, a version of Internet Cafes found in cities and towns. These telecentres could be set up in schools or community halls.

Infrastructure

The poor telecommunications and electricity infrastructure in the Pacific, particularly in rural areas and outer islands, has inhibited the expansion of ICT technologies in the region. This has been partially overcome by use of technologies that do not need this infrastructure in place (e.g. the use of radio and solar technologies in the People First Network of Solomon Islands). However, if countries intend to deliver more advanced tools over the Internet, there is a need for more robust ICT infrastructure that will support broadband technologies.

Literacy (English)

The Internet is very much an English medium, with 30 per cent of Internet users being English speaking in 2007 (www.internetworld stats.com/stats7.htm) and 68 per cent of the web-content being in Eng-lish (2004 - www.glreach.com/globalstats/refs.php3). The most widely used language in the Pacific region is English. Most sites are in Eng-lish and those who cannot read EngEng-lish are thus handicapped. But the landscape is also quickly changing. This year, over 14 per cent of Internet users worldwide are Chinese Mandarin speaking, 8 per cent Spanish, 7.7 per cent Japanese, 5.3 per cent German and 5 per cent French. In the Pacific, English will likely remain the dominant lan-guage. However, the development of vernacular content in Pacific Is-land countries should be encouraged with information being offered in both English and the other major languages used in the country. This should be a policy for government websites so that this goes some way in overcoming any language barrier that may exist.

Digital literacy (or computer literacy)

The flip side is that large numbers of people are digitally illiterate be-cause they have not had the opportunity to use a computer in their lives, which means they will not be able, on their own, to benefit from any advancement in the technology.

Local content

Although the Internet has a vast amount of content, very little in the Pacific is local content. It is easier to find out what the City Coun-cil of Hamburg, Oslo, or Stuttgart is doing rather than to keep up with the City Council of Suva, Honiara, or Port Vila where we actually live. Pacific Island countries must make serious efforts to develop lo-cal content, relevant to lolo-cal populations, for the Internet as much as for other local media.

All these obstacles point to the need to have technology interme-diaries based at tele-centres. These are trained persons that can help people who are either English illiterate or digitally illiterate to make optimal use of ICTs. They are the ones who know the technology and can assist people receive or pass on the information they require. These intermediaries will also be in an ideal position to develop local content in accordance with the needs of local communities. Without these intermediaries, ICTs will remain inaccessible to most of our populations.

International and regional structures

There are a number of international and regional structures that now deal with the development of ICTs in one way or another.

The international recognition that ICTs and development are linked was probably given by the UN Millennium Summit and the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), particularly Goal 8, which was basically a hotchpotch goal that included targets on trade, aid, debt, the private sector and even land-locked and Small Island devel-oping states. One of the targets under this Goal 8 was: ‘In cooperation with the private sector, make available the benefits of new technolo-gies—especially information and communications technologies’.1

The UN hosted the World Summit on the Information Society

1

(WSIS) held in Geneva in 2003, followed by another Summit in Tunis in 2005.2 In 2003, the Summit produced a declaration of principles and a plan of action (World Summit on the Information Society, 2003). There were 11 principles:

1. The role of governments and all stakeholders in the promotion of ICTs for development

2. Information and communication infrastructure: as essential founda-tion for an inclusive informafounda-tion society

3. Access to information and knowledge 4. Capacity building

5. Building confidence and security in the use of ICTs 6. Enabling environment

7. ICT applications: benefits in all aspects of life

8. Cultural diversity and identity, linguistic diversity and local content; 9. Media

10. Ethical dimensions of the Information Society 11. International and regional cooperation.

On the Media, the Plan of Action suggested the following:

a) Encourage the media—print and broadcast as well as new media— to continue to play an important role in the Information Society b) Encourage the development of domestic legislation that guarantees

the independence and plurality of the media

c) Take appropriate measures—consistent with freedom of expres-sion—to combat illegal and harmful content in media content d) Encourage media professionals in developed countries to establish

partnerships and networks with the media in developing countries, especially in the field of training

e) Promote balanced and diverse portrayals of women and men by the media

f) Reduce international imbalances affecting the media, particularly as regards infrastructure, technical resources and the development of human skills, taking full advantage of ICT tools in this regard g) Encourage traditional media to bridge the knowledge divide and to

facilitate the flow of cultural content, particularly in rural areas.

The 2005 WSIS Tunis Summit produced a ‘Tunis Commitment’ which reiterated the urgency to bridge the digital divide, and an ‘Agenda for the Information Society’. Regionally, we have also made

2

headway in establishing structures that promote and support the use of ICT for development.

PacINET is an annual conference held in the Pacific as a venue to discuss the development of ICT in the Pacific, with an emphasis on technical issues. If the media want to reach the people who are driving the development of ICT in the region, this is the conference they need to attend. PacINET is convened by the Pacific Islands Chapter of the Internet Society (PICISOC). The Internet Society is ‘the international organisation for global coordination and cooperation on the Internet, promoting and maintaining a broad spectrum of activities focused on the Internet's development, availability, and associated technologies’

(http://www.isoc.org/isoc/). It currently has more than 100 organisa-tion members and over 20,000 individual members in over 180 coun-tries. PICISOC was formed in 1999 to represent the Pacific Islands in ISOC as well as provide a space for Pacific Internet users to discuss ICT developments in the region (http://www.picisoc.org).

The University of the South Pacific (USP) was one of the first organisations to realise the need for ICTs in a region such as this. USP’s Distance and Flexible Learning Centre (DFL) makes use of a satellite communications network, USPNet, to deliver tertiary educa-tion to people in the Pacific who would otherwise not be able to study face-to-face. In fact half of USP’s 15,000 students make use of this tool, with over 200 credit courses being offered through DFL.3

Another successful initiative in the region is the Pacific Public Health Surveillance Network (PPHSN or PACNET) coordinated by the Secretariat of the Pacific Community (http://www.spc.int/phs/ PPHSN/index.htm). In existence since 1996, it is a network of health professionals to harmonise health data needs and develop adequate surveillance systems, including operational research; develop relevant computer applications; adapt field epidemiology and public health surveillance training programmes to local and regional needs; promote the use of e-mail, opening the network to new partners, new services and other networks; and produce publications. PPHSN has given rise to other networks: EPINET, LABNET and PICNET. EPINET (Epi-demiology Network) offers coordinated surveillance and response field activities, as well as establishing and maintaining relevant target-diseases surveillance and response protocols, including all technical

3

and resource-related aspects of all operations. LABNET (Laboratory Network) networks a small group of existing laboratories in the Fiji Islands, French Polynesia, Guam and New Caledonia to provide pub-lic health laboratory services for all Pacific Island countries for the six initial target diseases (dengue, measles, influenza, leptospirosis, chol-era and typhoid). PICNET (Pacific Infection Control Network) aims to communicate ways in which, with limited resources, one may ensure patient and health care worker safety from infectious diseases.

PACWIN (Pacific Women’s Information Network), another SPC coordinated Network, brings together a very active network of women, most from the Pacific, who share information and discuss gender-related issues affecting the region (http://www.spc.int/wom en/).

Although all these efforts have benefited some people in Pacific Island countries, ICT initiatives have so far been ad hoc. There is little relationship between these different initiatives. They arose from indi-vidual, mostly donor driven, endeavours. One cannot help feeling that the region could have achieved more if these initiatives arose from a shared vision and according to agreed strategies.

This recognition of the importance of ICTs by Pacific regional organisations has had an impact on the development of regional ICT strategies. The strategy for the development of ICTs in the region is encompassed in a number of documents: the Communication Action Plan (CAP) of 1999 and reviewed in 2002; the Pacific Islands Infor-mation and Communications Technologies Policy and Strategic Plan (PIIPP) of 2002 and the Pacific Regional Digital Strategy (PRDS).

The Pacific Islands Forum Information and Communications Technologies Ministerial Forum held in Wellington in March 2006 is-sued a declaration (termed the ‘Wellington Declaration’) in which it was declared that :

A survey conducted in 20024 by the Forum Secretariat identified a number of priorities including:

• Human resource development (including training and the es-tablishment of systems to assist HRD)

• Price reductions of telecommunications services

• The need for telephone and Internet services to outer islands and outer lying areas

• The need to encourage ICTs in schools by ensuring that

school students have access to computers and the necessary training methods

• Telecommunications infrastructure development

• Improved networked economies through government and e-commerce

• Development of policy and regulatory frameworks.

The Pacific Regional Digital Strategy5 was developed as a com-ponent of the Pacific Plan.6 The strategy is built around three pillars— at the country level, the regional level and the global level.

At the country level, it emphasises the need for ICT country strategies that ‘will develop and sustain strong country leadership of, and stakeholder involvement in, ICT development’. It identifies a number of key programmes that reflect the processes necessary to de-velop ICTs at the national level, but using regional capacity. These in-clude support to leaders to develop policy, plans and programmes; de-velopment of measures to assist in the gathering of statistics and the setting up of development targets; expansion of telecommunications access to rural and remote areas; and development of human re-sources.

Interestingly, at the regional level, the strategy’s primary key pro-gramme regards ICT leadership, including research, governance, ad-vocacy, consulting, regional planning and coordination, promotion of best practice, equity in representation and statistics.

Pacific Island countries are starting to develop their own national ICT strategies. Vanuatu has developed a ‘Telecommunications Policy

4

http://forumsec.org/UserFiles/File/ICTsurveyreport2002.pdf 5

www.pacificplan.org/tiki-page.php?pageName=Digital+strategy1 6

Statement’ that it has submitted for public consultation. In this policy statement, Vanuatu outlines its near-term, medium-term and long-term objectives as follows:

Near term objectives

• Review, update and promulgate a new telecommunications legal and regulatory framework (including a new Telecommunications Act)

• Promote new private entrants to provide services. Medium-term objectives

• Ensure that prices to be paid by the public are at similar levels to those in open markets overseas, even taking into account Vanu-atu’s relatively small domestic market

• Ensure that quality of services will also be of similar levels to those in open markets.

Long-term objectives

• To have effective competition in most of the country, especially in mobile telephony and Internet access

• Achieve very good coverage of rural areas, especially with mo-bile telephone service and Internet access, with private invest-ment and, where appropriate, targeted support from a Telecom-munications Development Fund, and as a consequence also of reasonable licence requirements.

National strategies have been found to be very effective in giving guidance to the development of ICTs in a country, ensuring optimal use of available resources for the benefit of all sectors of society, and not just the privileged few.

Measuring ICT development

A number of indices are now being used to measure the devel-opment of ICTs in different countries and these indices are used to compare development between countries. The one that has taken most usage is the Digital Opportunity Index (DOI).

per-sonal computers and Internet access; and data on more advanced tech-nologies in broadband access.

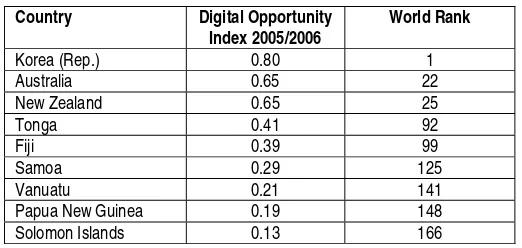

The 2007 World Information Society Report: Beyond WSIS7 provides the Digital Opportunity Index and the World Ranking for most countries in the world.

Table 16.1: Digital Opportunity Index and World Rank: 2005/06

Country Digital Opportunity

Index 2005/2006

World Rank

Korea (Rep.) 0.80 1

Australia 0.65 22

New Zealand 0.65 25

Tonga 0.41 92

Fiji 0.39 99

Samoa 0.29 125

Vanuatu 0.21 141

Papua New Guinea 0.19 148

Solomon Islands 0.13 166

There are some lessons to be learned from countries like Korea. The report attributes the Korean success mostly to the government’s lead role in the deployment of broadband. However, its success is a combination of factors: environmental factors (high literacy and school enrolment, tech-savvy consumers and a largely urbanised population); policy factors (a strong government push towards the In-formation Society and high investment by the private sector in new technologies and services); and a highly competitive market structure. What sets Korea apart is the strong guiding role played by the gov-ernment. The government set up a Ministry of Information and Com-munication (MIC), which promoted broadband deployment by estab-lishing a framework for facilities-based competition. It kept regular consultations with telecommunications operators to keep user costs low and promote access throughout the country. It also promoted na-tion-wide training programmes for computer and Internet skills with large-scale education for children, housewives, the elderly and the disabled. The Pacific may not be able to repeat Korea’s success but there are certainly many lessons to be learned!

7

The full report is available at

Despite all the amazing stories coming out of India, it only ranks 124th on the world index, whereas China, a comparably populous na-tion, ranks 77th. The ICT stories that come out of a country may not necessarily be indicative of the success of their ICT strategies. It may just be an indication of a better thriving media, or an indication that there are better (English speaking) journalists reporting ICT stories in India than there are in China!

In the Pacific, we know that Fiji’s economy is stronger than that of Tonga. However, Tonga has been able to create better digital op-portunity than Fiji, which ranks it higher on the DOI. Similarly, Vanu-atu ranks higher than Papua New Guinea.

Unfortunately, other Pacific Island countries (e.g. Cook Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Kiribati, Marshall Islands, Nauru, Niue, Palau and Tuvalu) are not covered in the Index. This is in itself an indication that these Pacific Island countries need to strive to col-lect the kind of data necessary to be able to work out the digital oppor-tunity indices for these countries as well.

Countries that have made rapid growth in Internet development have been those with prominent IT champions (in the case of Malay-sia it was the then Prime Minister, Mahathir Mohammed himself). The other characteristics include an open and pro-active government; a dynamic private sector; investment in appropriate infrastructure; ap-propriate and forward-looking IT and telecommunications public poli-cies and legislation; and a clear understanding of the overall impact on a country’s welfare.

Reporting ICT for development

Journalists of small media agencies, like those in small island states, are expected to be experts on everything. In the Pacific Islands there is hardly any specialisation in covering beats like ICT, as one would tend to find in larger nations. But this is an important area for national development. The media has a key role to play by analysing and disseminating information and creating awareness.

Media companies can invite specialised contributors, or they may consider giving their journalists specialised training in ICTs, not just in their use, but more importantly in understanding the underlying is-sues of ICT development and ICT for Development (ICT4D).

sabotage. The media cannot ignore the importance of security to a modern society that works through the Internet. Viruses, spyware, identity thefts and problems created by crackers, hackers and spam agents can do a lot of damage.

The more traditional crimes have taken on more sophistication through the use of such a versatile technology to form illegal networks in money laundering, child pornography, trade in women, trade in en-dangered species, trade in stolen antiquities, terrorist groups, and so forth. The Pacific is not immune from these hazards.

The need for journalists to understand ICTs and report on them is further underlined by the rapid growth of the Internet. There are pres-ently some four million websites being added to the Internet every month.8 If something as rapidly expanding as the Internet does not de-serve a journalist’s attention, then what does?

Opportunities need to be created so that our journalists in the Pa-cific region understand the intricacies of a rapidly changing technol-ogy and are thus able to make judgements on the types of technologies being offered by the market; the strategies being offered by govern-ments; and the real digital threats facing our societies (rather than those promoted by governments wanting to control our cyber free-doms using the excuse of some looming cyber-terrorist threat).

Editors and newsroom managers need to recognise the impor-tance of the technology and the need for their journalists to be better prepared and able to understand the issues related to ICT4D. This will enable them to inform the public better about the ramifications of de-cisions and actions taken by their governments or the private sector. Similarly, Pacific leaders should recognise the importance of the me-dia in educating the public on ICTs. The education of journalists in this area should form part of the region’s digital strategy and of any national strategies that are developed.

8