Mel and Khaonh Language

Survey Report

Philip Lambrecht and Noel Mann

SIL International

®2017

SIL Electronic Survey Report 2017-004, March 2017 © 2017 SIL International®

The survey was done under the auspices of the ICC (International Cooperation Cambodia) and included the ethnic Mel and Khaonh people, in Kratie Province of Cambodia. It took place in 2009 to inquire about how ethnic Mel and Khaonh people identify and group themselves in terms of language,

iii

4.1.1 Language use and proficiency – Roluos Village

4.1.2 Language preferences – Roluos Village

4.1.3 Perceptions of language vitality and loss – Roluos Village

4.1.4 Ethnic identity and mixing – Roluos Village

4.2 Paklae Village

4.2.1 Language use and proficiency – Paklae Village

4.2.2 Language preferences – Paklae Village

4.2.3 Perceptions of language vitality and loss – Paklae Village

4.2.4 Ethnic identity and mixing – Paklae Village

4.3 Chhork Village

4.3.1 Language use and proficiency – Chhork Village

4.3.2 Language preferences – Chhork Village

4.3.3 Perceptions of language vitality and loss – Chhork Village

4.3.4 Ethnic identity and mixing – Chhork Village

4.4 Changhab Village

4.4.1 Language use and proficiency – Changhab Village

4.4.2 Language preferences – Changhab Village

4.4.3 Perceptions of vitality and loss – Changhab Village

4.4.4 Ethnic identity and mixing – Changhab Village

4.5 Srae Tahaenh Village

4.6 Education

4.7 Summary of language vitality

1

1 Introduction

The goals of this language survey were to answer the following:

1. How many varieties of Mel and Khaonh languages are there?

2. Speakers of which varieties might be able to share the same language materials?

3. Which varieties of Mel and Khaonh might continue to be used in the next generation?

The data collection for this research was done by International Cooperation Cambodia (ICC) staff between November 27 and December 7, 2009 in six villages in Kratie Province of Cambodia. Some data was also collected by ICC staff in 2006, and some of the wordlists compared were taken by others at different times. Noel Mann did the wordlist comparison.

1.1 Ethnic and language names

The focus of this language survey is the ethnic Mel (pronounced [məl]) and ethnic Khaonh (pronounced

[kʰaoɲ]) people in Cambodia and the languages they speak. The ethnic Mel people speak the Mel

language, and, likewise, the ethnic Khaonh people speak the Khaonh language.1

There are three sub-groups of Mel people: 1) people associated with Roluos village; 2) people associated with Paklae village; and 3) people associated with Changhab village. Ethnic Mel people from Roluos village are sometimes called Mel Kachroung, Kachroung, Mel Kanh Chrong, Kanh Chrong, or Onchrouk. Ethnic Mel people from Paklae village are sometimes called Mel Arach or Arach. Ethnic Mel people from Changhab village are sometimes called Kachrouk or Mel Kachrouk. People from all three of these groups usually just call themselves Mel, and they accept the proposition that people from the other sub-groups are also included in their larger Mel group. The name for the traditional language of all three groups of Mel people is the same as the ethnic name, Mel, but the way people from Paklae speak can also be called Arach, and the way people from Changhab speak can be called Kachrouk, and so on. All of the Mel people we talked to, regardless of the village and variations in ethnic name and way of speaking, included all of the other Mel people with themselves in the same ethnic and language group.

Given the lexical similarity and apparent inherent intelligibility between Mel and Khaonh language varieties, the two varieties could be considered dialects of the same language. Furthermore, some Khaonh people we talked to included people from Paklae, Roluos, or Changhab villages (people who identify themselves as Mel) in their Khaonh ethnic group or as speakers of the Khaonh language. However, all Mel and Khaonh people recognize a distinction between Khaonh and Mel ethnicities and languages, and generally they do not include each other in the same group, in part because, in general, they do not consider the other language to be comprehensible. We will therefore use the two names, Mel and Khaonh, to maintain their distinction between the two peoples and languages.

1.2 Linguistic classification

Neither Mel nor Khaonh languages have been classified linguistically, though they are most lexically similar to languages in the South Bahnaric sub-branch of Eastern Mon-Khmer. Mel and Khaonh

(grouping them together to compare lexical similarity) are most lexically similar to the Stieng language in the Snuol district of Kratie Province (80 percent), followed by the Stieng in Kaev Seima District of Mondul Kiri Province (77 percent), Ra’ong (76 percent), Thmon (74 percent), Kraol (73 percent), Stieng in Memot District, Tbong Khmum Province (70 percent), and Bunong (70 percent).

Ken Gregerson examined some of our wordlists for lexical comparisons and has written some initial statements about the relationship of Mel, Khaonh, Kraol [rka], Thmon, and other South Bahnaric

languages. He tentatively made the following points (Gregerson 2010):2

1. Mel, Khaonh, Kraol, and Thmon languages appear on first inspection to be South Bahnaric. That is,

the burden of proof would seem to be on any classification to the contrary.

2. Mel and Khaonh seem to form a subgroup, as do Kraol and Thmon.

3. Khaonh and Kraol seem to have some kind of relationship cross-cutting the grouping of each with

another language as its main affinity.

4. The similarity of some Mel, Khaonh, Kraol, and Thmon forms with Central Bahnaric may be due to

loans from, say Tampuan [tpu], or it may speak to the greater connections of Central and South Bahnaric themselves.

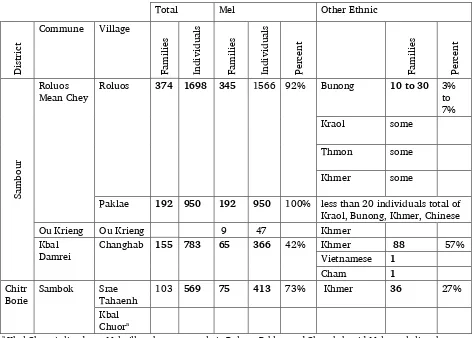

1.3 Location and population

Mel and Khaonh people live in Kratie Province. Roluos, Paklae, Changhab, and Srae Tahaenh are the main Mel villages, although there are a few Mel families in Ou Krieng village as well. Chhork and Kasang are the main Khaonh villages, with a few families reported to live in Changkrang and Kaoh Dach villages as well. The total Mel population is about 3,295 individuals. The total Khaonh population is probably between 300 and 450 individuals. Most of the figures we used to calculate these populations were given to us from village leaders in 2009. These figures from the village leaders in 2009 are in bold type in table 1 and table 2. The rest of the figures in these tables (not in bold) were taken from talking to people in the community in general, between 2006 and 2009.

Table 1. Mel Villages and Population

a Kbal Chuor is listed as a Mel village because people in Roluos, Paklae, and Changhab said Mel people live there. However, when we asked Mel people in Srae Tahaenh, which is about 2km from Kbal Chuor, they said that there are no Mel people in Kbal Chuor. We never went to Kbal Chuor to ask people.

Table 2. Khaonh Villages and Population

Total Khaonh Other Ethnic

District Commune Village Families Families Percent

Chitr

a Kandal Province (see Sections 3.1.5 and 4.3.4 for more details about this move.)

b The figures for Changkrang and Kaoh Dach villages were estimates given by the Khaonh group interviewed in Chhork; we did not get any official numbers for those villages.

1.3.1 Maps

The language areas in these maps are general indications, not actual boundaries. We have no data about ethnic land ownership, just villages or areas that are associated with ethnic groups, around which these areas are drawn. The ethnic/language-identity make-up within any area is not homogeneous. For

example, many villages/areas have people from more than one ethnicity, and Khmer people live in many villages/areas, including those included in ethnic minority areas in this map. Some ethnicities, such as Cham, are not represented. The areas in Ratanak Kiri Province roughly follow commune boundaries and the majority ethnic group represented in those communes, according to village-level records from the Ratanakiri Provincial Department of Planning in 2006. Also, though not indicated by the areas drawn on the maps, some language groups cross national boundaries, such as Bunong and Stieng. All maps were

2 Methodology

The goals of our research were to find out how many varieties of Mel and Khaonh are spoken in

Cambodia, which of those varieties might be able to use the same language materials, and which of those varieties might continue to be used in the next generation.

The way we define a language variety is according to how people group themselves by language. So, if people in three villages agree that they all speak the same language the same way, then we would say those people use the same variety. If people say that they speak the same language, but not in the same way as people in another village, then we report that the people in the two villages speak different varieties. So, we asked people what languages they speak and who else speaks the language in the same way and differently.

In addition, we wanted to know which varieties could probably be grouped together to use the same literature or spoken language materials. Our basis for suggesting varieties which could possibly be grouped together or not is acceptance and inherent intelligibility, as suggested by comprehension and lexical similarity.

In our assessment of vitality, our definition of vitality is that children are now speaking the language, at least in the home, and will possibly choose to speak the language to their children in the next generation. So, we at least wanted to be clear about whether or not the children are now speaking the language. And we wanted to have some idea, based on what languages people think are good to speak, about what choices today’s children will make about what languages to speak to their children in the next generation.

Therefore, our research questions are related to:

• identity—how do people group themselves in terms of ethnicity and language, and what are the

perceived differences between their group and other groups?

• inherent intelligibility—how well can people understand a different language variety based on its

relatedness to their own variety, without having learned it?

• wordlist comparison—how do varieties group together based on lexical similarity?

• language use—what languages do people use in the home and other domains, and what languages

do older people use as compared to younger people?

• language proficiency—what do people report about their ability to speak/understand Mel, Khaonh,

and Khmer?

• language preferences—which varieties do people think are good to use, for them and their children,

for different purposes?

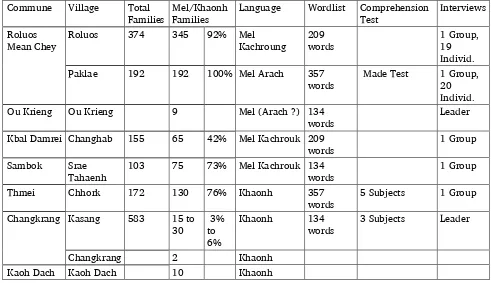

The methods we used to answer our research questions are interviews, wordlist comparisons, and comprehension testing. We talked to people in every Mel and Khaonh ethnic village in Cambodia that we

knew of except for Changkrang, Kaoh Dach, and Kbal Chuor.3 The work we did in each village is listed in

table 3, as well as some of the work the ICC research team did in 2006.

Table 3. Work done in each village

We did group interviews by asking the village leader to bring together, usually the next day, ten to twenty Mel/Khaonh people, preferably older people knowledgeable about their history and culture. When the group gathered at the time set by the village leader, we spent between two and three hours following a questionnaire, asking about how people identified themselves, what languages they use when and how well they speak them, how well they understand other varieties, and so on. We tried to

encourage participation from all the participants in the group interviews. A few of the individuals participating in the groups were not Mel or Khaonh ethnicity, but they were accepted by the others in the group. The groups we interviewed in Roluos, Paklae, and Chhork were all between twenty and twenty-five people, both men and women, most of them probably more than forty years old. The groups we interviewed in Changhab and Srae Tahaenh were seven and about fifteen people, both men and women, and most of them older.

2.2 Individual interviews

Because some of the things we wanted to learn about, like children’s language use or language proficiency, could vary from family to family and from generation to generation, we wanted to get a better representation of the range of responses in the village than we could get in the group interview. To do that we elicited information from randomly selected families/households by interviewing an individual from each of the selected families.

To represent the selected families, we chose adults who were available and willing to be

interviewed, and who were in a middle generation in the family, generally the parents rather than the children or the grandparents. Sometimes a few people from the family participated in the interview. Whether the family was represented by one or a few in the discussion, we chose one individual to report about him/herself, as well as answer questions, following a questionnaire, about the whole family. For example, we asked the individual to report what her first language was, as well as the first language of her grandparents, parents, her siblings, her spouse, her children (if any), and her grandchildren (if any). This leads us to make statements in this report such as, “70 percent of all responses were that they speak Khmer,” which does not mean that seventy people out of one hundred said they speak Khmer, but rather a few individuals, the individuals we interviewed to represent whole families, collectively gave one hundred responses about themselves, their parents, their children, their spouses, etc., and seventy of those responses were that they or their family members speak Khmer. Our assumption in this methodology is that one person in the family can represent other family members for the things we asked about, such as language use.

We intended to show generational differences in responses by asking about grandparents, parents, children, and grandchildren. However, we do not have a record of the age of the individuals that responded for the rest of their family. So, we cannot say precisely whether all of the individuals, the individuals’ spouses, and the individuals’ siblings represent the same generation. Nevertheless, because we were looking for people to interview who were from a middle generation—individuals that probably

had children of their own4 but not the “old” people in the family—we probably interviewed individuals

that were in the middle of the age-range in the village. Our estimation, based on what we can remember about the people we interviewed, is that the individuals we interviewed were all between twenty and forty years old.

We did individual interviews in two villages: 19 interviews in Roluos and 20 in Paklae. In Roluos, we did not get a response for three of the families we had randomly selected; two because they were staying in their fields, farther than we wanted to go to find them, and one because the family had gone to the forest and was not coming back soon. In Paklae, one family we selected did not respond because of illness. When these families did not respond, we interviewed the next family on the list of randomly selected families.

2.3 Lexical similarity comparison

This section describes the lexical comparison approach for computing lexical similarity among the Bahnaric varieties in this survey.

Lexical comparison is an approximation of the percentage of cognates shared by two or more language varieties. The results from this approach do not provide an absolute measure of the relationship between language varieties, but rather a relative measure of the lexical relationship between varieties.

2.3.1 Transcription leveling

For this comparison, wordlists from several different sources were used. While the transcriptions seem to be of high quality, there is some variation in the transcription conventions. Thus, there seemed to be a need to level the wordlists using the same transcription metric in order to make the comparison meaningful. The following conventions were used:

• Replacements were made in the raw data: ʔb=ɓ, ʔd=ɗ, ʔɡ=ɠ, ʀ/ɾ=r, y=j.

• Consonant and vowels given equivalent status: w – u/u – w, j – i/i – j. Equivalent forms were

posited for these segments when it made a match in the lexical set more plausible. When more than

one form is available for comparison between varieties, the more optimal match is used. The only limitation in reinterpreting these vowel and consonant transcriptions is that while diphthongs are allowed, tripthongs are not.

• Vowels clarified: ɑ=a (open central unrounded), ʌ=ɜ, ɵ=ɘ (Barr and Pawley 2013:60).

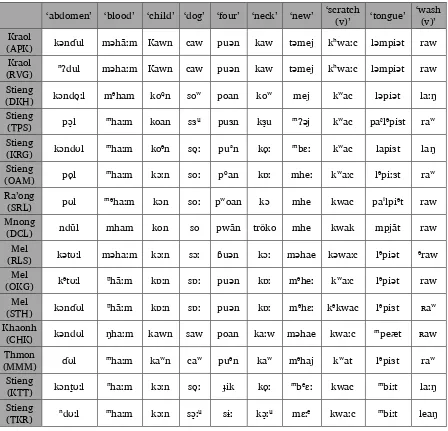

Since vowels and consonants that appear to be raised in some varieties corresponded to non-raised segments in the other varieties, these features are lowered to represent full segments in this comparison except for aspirated stops. Table 4 highlights raised elements that are considered full segments in this analysis.

Table 4. Segmental interpretation of raised elements

‘abdomen’ ‘blood’ ‘child’ ‘dog’ ‘four’ ‘neck’ ‘new’ ‘scratch (v)’ ‘tongue’ ‘wash (v)’

2.3.2 Procedure

Bahnaric languages, like other Mon-Khmer languages, are sesquisyllabic. Sesquisyllabic languages have a minor syllable and a major syllable. The minor syllable comes first and is unstressed while the following major syllable is stressed. Over time, these minor syllables are subject to innovation and sometimes collapse onto the main syllable, while the major syllable is usually retained and can be reliably reconstructed. In some Mon-Khmer varieties the minor syllable may be lost entirely. In Proto South Bahnaric, Sidwell (Sidwell 2000:15) states:

Often the main syllables correspond regularly and it is only the minor syllables which do not agree. In these cases it is obvious that there is one root with different prefixes, and it is straightforward to reconstruct alternate protoforms with the same main syllable, e.g.

*pɑːŋ~*nəpɑːŋ~*pəpɑːŋ ʻpalm, sole’… the main syllable *pɑːŋ is reconstructed securely, and it may

or may not have occurred with the minor syllables indicated.

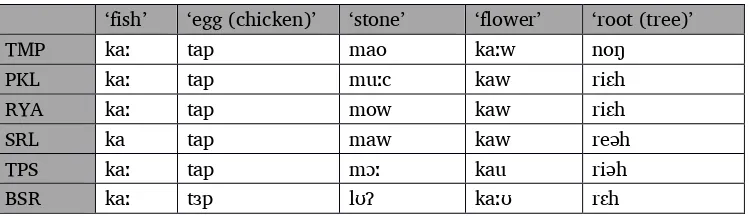

Since the non-main syllables can often obscure the historical relationship between languages, the non-main syllables should be removed in the first phase of the lexical comparison. Consider for example, the following dataset of Bahnaric languages in table 5.

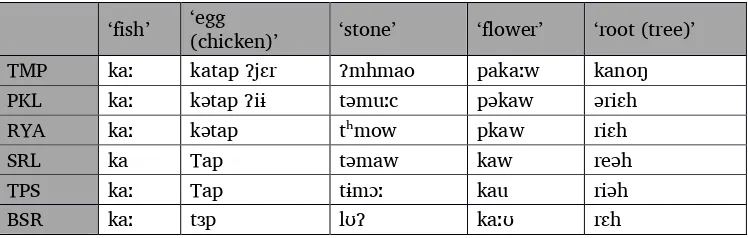

Table 5. Bahnaric lexical sets showing full forms

‘fish’ ‘egg (chicken)’ ‘stone’ ‘flower’ ‘root (tree)’

TMP kaː katap ʔjɛr ʔmhmao pakaːw kanoŋ PKL kaː kətap ʔiɨ təmuːc pəkaw əriɛh

RYA kaː kətap tʰmow pkaw riɛh

SRL ka Tap təmaw kaw reəh

TPS kaː Tap tɨmɔː kau riəh

BSR kaː tɜp lʊʔ kaːʊ rɛh

For the first word ‘fish’ the form is unambiguously monosyllabic, thus no further analysis is required and these forms can be directly compared. For the word ‘egg’, the word ‘chicken’ is sometimes included

as an elaboration, variously [ʔjɛr] and [ʔiɨ], these can be eliminated. Also, the minor syllable [ka] and

[kə] can be removed. The words for stone are more complicated with minor syllables variously [ʔmh],

[tə], [tʰ], and [tɨ] which can be removed. Considering the word forms for ‘flower’ the minor syllable has

various forms [pa], [pə], and [p], which can be eliminated. Finally, the word forms for ‘root’ have minor

syllables with forms [ka] and [ə], which can also be eliminated. Thus, these morphemes are ignored.

Applying these basic steps, we can clarify the data by eliminating minor and supplemental syllables, as

shown in table 6.5

5While illustrating this procedure as though using hand methods, the analysis was performed by the lexical

Table 6. Bahnaric lexical sets showing roots

Considering that some forms may vary phonetically depending on the conventions of the team transcribing them, alternate comparison forms, one with an approximant and one with a vowel, were posited for ‘stone’ and ‘flower’. For these forms, the algorithm is optimized to use the most similar forms in the comparison. Furthermore, vowel length and breathiness are ignored. Thus, this set can be

simplified into the following lexical set in table 7:

Table 7. Bahnaric lexical sets showing roots and simplifications

‘fish’ ‘egg (chicken)’ ‘stone’ ‘flower’ ‘root (tree)’

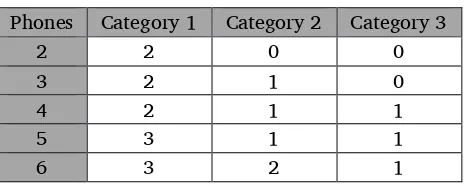

From the data shown in table 7 relationships between the word forms emerge. Using this data, a method adapted from Blair (Blair 1990:31–33) is applied to clarify which forms are lexically similar and which forms are not lexically similar. Table 8 shows the criteria used in this method:

Table 8. Criteria for lexical similarity Criteria

Category 1 a. Exact consonant matches

b. Vowels or diphthongs differing by one or fewer features c. Phonetically similar consonants in three or more word pairs

Category 2 a. Phonetically similar consonants in fewer than three word pairs

b. Vowels or diphthongs differing by two or more features

Category 3 a. Non-phonetically similar consonants

b. A consonant correspondence with nothing in fewer than three word pairs

Ignore a. Non-root syllables (minor syllables and elaborative syllables)

b. A consonant correspondence with nothing in three or more word pairs

c. Interconsonantal schwa [ə]

d. Word initial, final, or intervocalic [h] e. Vowel Length

f. Breathiness

g. [r] corresponding to nothing word final

h. [r] or [l] corresponding to nothing in a consonant cluster (C_) i. Breathiness

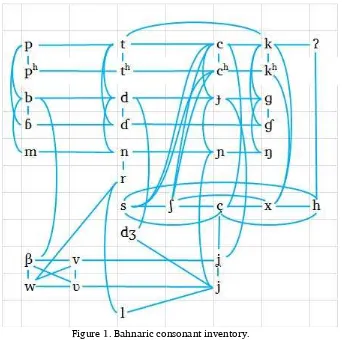

For the Bahnaric wordlists, the phonetic inventory with phonetically similar segments (connected by lines) is shown for consonants in figure 1 and for vowels in figure 2.

Figure 1. Bahnaric consonant inventory.

The following consonants occur word-finally [p, t, c, k, ʔ, m, n, ɲ, ŋ, r, l, w, j, ç, x, h]. Of these

word-final consonants [x] is limited in distribution to occurring only in the word-final position in a few cases. The recurrence of some sound correspondences is limited to specific environments. For example,

the [s–c] relationship is prevalent word-initially while the [t–k] and [ç–h] relationships are evidenced

word-finally. In addition to these vowels there is an abundance of diphthongs with [au] being the most common.

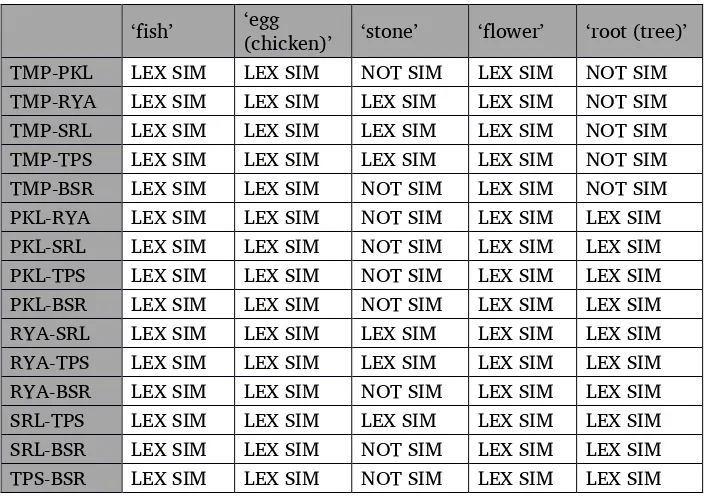

Returning to the Bahnaric dataset, the lexical similarity of word forms can be established based on the criteria from table 9. This yields the result shown in table 10.

Table 9. Lexical similarity criteria application

‘fish’ ‘egg (chicken)’ ‘stone’ ‘flower’ ‘root (tree)’

TMP-PKL 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b,3b 1a,1b,1a 3a,2b,3a

TMP-RYA 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 3a,2b,3a

TMP-SRL 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 3a,1b,3a

TMP-TPS 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 3a,1b,3a

TMP-BSR 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 3a,2b,3b 1a,1b 3a,2b,3a

PKL-RYA 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b,3b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b,1a

PKL-SRL 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b,3b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b,1a

PKL-TPS 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b,3b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b,1a

PKL-BSR 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 3a,2b,3b 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a

RYA-SRL 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b,1a

RYA-TPS 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b,1a

RYA-BSR 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 3a,2b,3b 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a

SRL-TPS 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 1a,1b,1a

SRL-BSR 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 3a,2b,3b 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a

TPS-BSR 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a 3a,2b,3b 1a,1b 1a,1b,1a

Once the categories have been assigned for all of the phones, a phone table is used to determine whether the words thus compared are lexically similar or not. This phone table (table 10) is based on the number of phones and specifies the minimum conditions the word forms must meet in order to be considered lexically similar.

Table 10. Phone table for lexical similarity

Phones Category 1 Category 2 Category 3

2 2 0 0

3 2 1 0

4 2 1 1

5 3 1 1

6 3 2 1

Table 11. Lexical similarity analysis

In table 11 ‘LEX SIM’ means the word pairs are lexically similar, and ‘NOT SIM’ means the word pairs are not lexically similar. From the composite of all these variety comparisons using the root forms, we compute the percentage of lexical similarity and generate the lexical matrix (tables 14 and 15). The number of root forms compared for this report is 85, following the methodology used by Julie Barr (Barr and Pawley 2013). All of the comparisons between wordlists are of 80–85 items, except for the

comparison between Mel-Srae Tahaenh and Bunong-Ou Rona (66 items compared) and the comparison between Mel-Srae Tahaenh and Bunong Preh-VN (67 items compared).

2.4 Comprehension test

The method we used for comprehension testing generally follows Angela Kluge’s retelling method (Kluge 2007). We used a story recorded in Paklae village to test how well Khaonh people in Chhork village understood Mel language from Paklae village. The Paklae story was told by an ethnic Mel woman, about age 50, who had always lived in Paklae village and whose parents were both ethnic Mel and from Paklae village. The story was approximately three minutes of narrative about a time when thieves came to her house. We roughly transcribed the story and translated it word by word so that we had a good idea about the content of the story, phrase by phrase. With this understanding, we divided the story into 15 segments ranging from 6 to 17 seconds (average 12 seconds).

Mel speakers from Paklae. In all 15 segments, there were 26 elements re-told by at least nine of the eleven Paklae people, and so there were 26 possible points for the test.

Before we asked the eleven people in Paklae to re-tell the story in order to identify the

elements/points in each segment, we gave them a practice test, asking them to retell segments of a short Khmer story we made up. We kept going through the practice test with each person until he/she

understood what to do and could retell accurately what was in each segment. If the person did not really get the process or did not re-tell accurately, we did not use his/her responses for scoring. The eleven people in Paklae that passed the practice testing and were scored were all ethnic Mel from Paklae village and spoke Mel language from childhood.

Before we gave this Paklae comprehension test to people in Chhork and Kasang, we made sure they also understood the test procedure by using the same Khmer language practice test, and we also gave them a control test—a test of their own language variety—which we could compare with their score on the Paklae variety test. Normally, this control test of their own language variety would be based on a story in the Khaonh language as spoken in Chhork village. However, because Khmer has become the primary language used by most people in Chhork village, we decided to use a Khmer language story as the control test. We made the assumption that everyone in Chhork speaks Khmer with high or near native proficiency, and therefore we expected that the people we tested in Chhork should get close to 100 percent on a Khmer test, higher than we expected that they would score on a Khaonh test. Our justification for this assumption was 1) what people reported in the group interview about their proficiency in Khmer and Khaonh; 2) our observation that it was easy to communicate with people in Khmer; and 3) our impression that the story teller from Chhork—an older Khaonh woman that the group we interviewed had put forward as a good Khaonh story teller—was actually more fluent in Khmer than Khaonh because she used Khmer more. Furthermore, the village leader could only come up with a list of about 15 older people in Chhork village who really know Khaonh language and could take the

comprehension test. So, we concluded that Khmer is the language Khaonh people in Chhork village, as a whole, are most proficient in. Therefore, we used Khmer for the control test story rather than Khaonh.

We gave the Khmer practice test, the Khmer control test, and the Mel test from Paklae to six people in Chhork village. All six of these people were from Chhork, were ethnic Khaonh, and were

recommended by the village leader as people who could speak Khaonh proficiently. All six of them understood the testing process and could re-tell accurately, judging by their performance on the practice test. Also, all six of them were between 53 and 63 years old. We wanted to test ten people, but the other 15 people on the village leader’s list of proficient Khaonh speakers were not able to master the practice test, were hearing impaired, were not in the village, did not want to take the test, or said they did not really know Khaonh language. So, we found three more people to test in Kasang village. The Khaonh people in Kasang village speak Khaonh in the same way as Chhork people, and the three individuals we tested were actually born in Chhork village. We wanted to test more people in Kasang, so that we could have a total of ten scores for the Paklae test, but we ran out of time.

We ended up with seven valid scores for the Paklae test. One of the eight Khaonh people that took the Paklae test did not score above 82 percent on the Khmer control test, so we did not include her score in the analysis.

3 Language varieties, intelligibility, and acceptance

3.1 Varieties of Mel and Khaonh

There are three main groups of Mel people: those from Roluos village, those from Paklae, and those from Changhab. Mel people in other villages, such as Srae Tahaenh or Ou Krieng, used to live in the same villages with people from Roluos, Paklae, or Changhab and separated in the relatively recent past. In all of the Mel villages we went to—Roluos, Paklae, Changhab, and Srae Tahaenh—there is a shared

understanding that there is a Mel ethnic group as well as a Mel language, the language that Mel people traditionally speak. There is also an understanding that the three groups speak differently from each other, and there are unique ethnic/language names for the three groups. Mel people agree that all of the Mel varieties are mutually intelligible, though people have different ideas about how well they

understand each other, and people have different ideas about what the differences in vocabulary and pronunciation are between the different varieties.

There is one main group of ethnic Khaonh people in Cambodia, the people that are associated with Chhork village, both the people that presently live in Chhork and those that separated after the time of the Khmer Rouge, such as the people in Kasang village. Accordingly, Khaonh people perceive no variation in the way Khaonh is spoken—they all speak the same way, they say.

3.1.1 Roluos perceptions

Mel people in Roluos village call themselves and their language Mel, which, apart from being their name, does not have any meaning. They said that the Mel people from Paklae call them “Mel Kachroung.” “Kachroung” means something like “support each other in unity,” and they accept that longer name for themselves as well, though their practice in the interviews was to refer to themselves simply as Mel.

The people in Roluos consider the Mel people in Paklae and Changhab, as well as the Khaonh people, to all have a common origin with themselves. One elderly man in the group interview said that the Arach (from Paklae), the Kachrouk (from Changhab), and the Khaonh people are all Mel, but they separated from each other and acquired different names.

“Arach” and “Mel Arach” are names that Mel people in Roluos use to refer to the Mel people in Paklae, though they can and do call them simply “Mel” as well. The Roluos group said that the name Arach means “laugh.” We asked if it were acceptable to call Roluos people “Arach,” and some people did not think it would be bad, but their conclusion was that Roluos people are not Arach. One man from Roluos, in informal conversation, said that “Arach” is what the Kraol people call the Mel people, and he added that Onchrouk is another “funny” name for Mel people in Rolous. He also said that Kraol people call Khmer people “Phrum.” The Roluos group described the Paklae way of speaking as noisy and like quarreling.

The group interviewed said that the Paklae speech is heavy sounding, while Roluos speaking is soft. In comparison with Changhab, they said people in Paklae sound curt and loud, less friendly. We asked how well children in Roluos can understand Paklae speaking and the group said children in Roluos do not really speak Mel, they always use Khmer, so they would not understand Mel from Paklae, or anywhere, very well. But older people from Roluos that do speak Mel can understand most of what Paklae people say.

“Kachrouk” and “Mel Kachrouk” are names that refer to Mel people in Changhab village, the Roluos group said, but they think it is acceptable to just call them “Mel.” They do not know what “Kachrouk” means. In describing the way the Changhab language sounds, people commented that it sounds more musical, more friendly, not loud like Paklae, and that Changhab people use long words. They also described Changhab speech as heavier than both Roluos and Paklae. The Roluos group interview participants estimated that old people in Roluos can understand about 70 percent of what Mel people from Changhab say.

people accommodate them and use words they have in common, and he estimated that they could understand about 70 percent of what Khaonh people say.

Out of all these varieties of speaking, Mel people from Roluos think that their way of speaking Mel is the most correct. But, they perceive that they are losing the Mel language in Roluos and that the Mel language in Paklae village is more vital. They would be very happy if the Mel language were preserved, and they think that Paklae people might have the best chance of preserving the Mel language. If the Roluos people heard Paklae people speaking Mel on a radio broadcast, they said they would be happy to listen to that.

3.1.2 Paklae perceptions

Mel people in Paklae identify themselves as ethnic Mel, along with the Mel people in Roluos, Changhab, and Srae Tahaenh villages. When we asked them which villages speak the same language, their first response was only Roluos and themselves, but when we asked how they grouped other villages, they said Changhab and Srae Tahaenh also speak the same language. They said that all of these Mel villages speak Mel language, but they speak differently. Paklae people recognize three groups of Mel people and language. Roluos people are called Mel Kanh Chrong, and the way they speak is “light.” Changhab people are called Mel Kachrouk, and the way they speak Mel is very different from Paklae—long, quiet, and heavy. Paklae people are called Mel Arach. They said “arach” means “laugh,” but they do not know of any meaning for “Mel.” They see the name Arach or Mel Arach as a name that was used more in the past; in the group interview they usually called themselves Mel.

We asked how well children from Paklae can understand the other groups, and they replied that their children can understand people from Roluos well, but they can only understand some of what Changhab people say. Neither children nor adults can understand Khaonh, they said.

Out of all of the varieties of Mel language, Paklae people think that their way of speaking Mel is the right way because it is not “mixed” like the way Roluos people speak. They think that if someone were to develop a written form of Mel language, it should follow the way they speak in Paklae.

3.1.3 Changhab perceptions

Mel people in Changhab include themselves in the same Mel ethnic group as Mel people in Roluos, Paklae, and Srae Tahaenh. The seven or so people we interviewed as a group said that they call themselves (and other people can call them) Mel or Mel Kachrouk. They do not know what “Mel” or “Kachrouk” means. But, they said calling them “Kachrouk” is like Khmer calling Vietnamese people “Yuon,” a Khmer word that means Vietnamese and is sometimes used in a derogatory way. Nevertheless, they said they are not offended or angry if people call them Mel Kachrouk. In regard to language, their point of view is that they and the Mel people in the other villages speak the same language, but in different ways.

They recognize the names “Mel Arach” and “Arach” as referring to the Mel people in or from Paklae, and their language. But they did not know what “Arach” means; it is not a word in Mel language, they said. The group we talked with perceives the Paklae way of speaking to be different from the Changhab way of speaking, comparing the difference between them to the difference between North and South Vietnamese. They further described Mel language from Paklae to be like religious language from ancient times, like “old language,” and as similar to Kraol language, which makes it less pure than the Mel spoken in Changhab.

Mel people in Srae Tahaenh and Kbal Chuor villages came from Changhab, for the most part, the group participants said, so the way they speak is the same as Changhab.

When we asked the Changhab group about Khaonh people, they said they do not have contact with them and that they speak a different language, of which they only understand one or two words. One man said he met Khaonh people during the French colonial time, and he remembered that when they said “go today” he thought they were saying “go tomorrow.”

3.1.4 Chhork perceptions

The Khaonh people in Chhork village identify themselves as ethnic Khaonh people and they call their traditional language Khaonh as well. They said that the name “Khaonh” does not have any meaning. Chhork people include the Khaonh people from Kasang, Kaoh Dach, and Changkrang villages in the same ethnic group as themselves, and they say that they all speak Khaonh language in exactly the same way. We asked the group interview participants if there is anything unique about the Khaonh people that separates them from other ethnic groups, besides the language. They said that Khaonh people make a kind of offering to spirits that Bunong people do not make, though they said Kraol people do something similar.

The Khaonh people in Chhork are aware of Mel people in Changhab, Paklae, and Roluos, and they have some ideas about who those people are and what they speak, but they said in the group interview that they do not have much contact with them. For example, they said that they never visit Changhab and Changhab people never come to Chhork; they only heard about Changhab people from their parents. Their understanding is that the people in Changhab speak Kraol language. Their perception of Paklae people is that Paklae people speak Arach language, which they described as heavier than Khaonh. They estimate they understand about 70 percent of what Paklae people say. A man who went to Paklae said he and the Paklae people had difficulty communicating when using Mel/Khaonh. He could understand some, but he could not speak the way they speak, so they ended up using Khmer language with each other. About Srae Tahaenh village, Chhork people think that the Mel people there speak Kachrouk language, which they also described as heavier than Khaonh.

Going by the group interview discussion, out of all of these varieties of language, the Khaonh people in Chhork think that Khmer language is most acceptable. They think Khmer sounds good, and they use Khmer more than Khaonh language, which they think is second best. They prefer Khmer over Khaonh because Khaonh has no alphabet, they explained.

3.1.4.1 Khaonh responses to a Paklae recording

Five Khaonh people from Chhork village and three from Kasang village took a comprehension test of Mel language from Paklae village. In addition, after the comprehension test, we asked them some questions about the language in the test story they had just heard.

After they had taken the test, one of the later questions we asked was if they had ever met Mel people and heard the Mel language. Five of the eight said they had never met Mel speakers. One of those five had never met Mel speakers herself, but her mother has siblings living in Paklae. The other three takers had met Mel speakers in Paklae or Changhab, to buy animals, or in the forest. Two of the test-takers have relatives living in Paklae.

Two of the people who heard the story said that the language was exactly the same as Khaonh, no different. The other six test takers pointed out some differences between Khaonh and the story language:

• the words are different

• the words are similar to the real words, but not the same

• the story language is not clear

• the language is not clear Khaonh, Kraol, or Bunong

• the language is half different

• four test takers said the story language is “heavier,” Khaonh is softer

• the story teller is “stiff-jawed”

• the story language has a different tone

We asked the eight test-takers to estimate their comprehension in terms of what percent they understood. Four of them estimated that they understood 70 percent (their actual average score was 82 percent), two estimated 100 percent (their actual average score was 80 percent), one estimated 50 percent (actual score: 83 percent), and one estimated less than 50 percent (actual score: 85 percent). The average score for all eight test-takers was 82 percent.

Of the eight that heard the story, six said they liked listening to the language and two said they did not like it. Comparing the Mel story to another Khmer story they heard as part of the comprehension test, three said they would rather listen to the Khmer story than the Mel story; two said the Mel story was preferable to the Khmer, and one said the Khmer and Mel stories were equally good.

For comparison with group interview responses and responses of other people that took the

comprehension test, some of whom had never actually had contact with the Mel language, below are the responses of three comprehension test-takers that had actually had contact with Mel speakers before listening to the comprehension test story.

1. From Chhork, age 60, no education. He has a brother that lives in Paklae and relatives in Srae Chis

and Srae Sbov. He has gone to Paklae, at one time spending ten days there, to buy cows and buffalo. While there, he spoke Khmer, but he heard them speaking their language. After listening to the recorded story from Paklae, he knew that it was Mel language. He estimated he only understood about 50 percent of the story (score: 85 percent). He said the vocabulary was different from Khaonh, but that the story sounded as good as Khaonh.

2. From Kasang, age 56, Grade 3 education. He has been to Paklae and Changhab. He has relatives in

Paklae, and he has visited there two times, staying one month each time. He has no relatives in Changhab so he only goes there rarely for business, to buy chickens or cows. He said that the Paklae and Changhab people speak Khaonh language, but he can only understand about 40 percent of what they say. After listening to the Paklae recording, he estimated that he understood 70 percent of the story (score: 81 percent), and he liked listening to it. He thought the story was either Kraol or Mel language.

3. From Kasang, age 58, Grade 1 education. He has never been to Paklae or Changhab, but he has met

Mel people in the forest. After listening to the story, he estimated that he understood about 70 percent of the story (score: 85 percent), and he liked listening to it, but he preferred listening to the story in Khmer. He thought the story was neither Khaonh, Bunong, nor Khmer language, but a mix of all three.

from Paklae are Khaonh people, and they told a history, retold below, of how Khaonh people came from near Paklae to be in Chhork village.

3.2 History of Mel and Khaonh

Our interviews with people in ethnic Mel and Khaonh villages did not reveal a cohesive history of the relationship between Mel and Khaonh. However, some comments and recollections were shared in the interviews that may be relevant to understanding how the groups of people are related to each other, or at least people’s perceptions.

At one village we went to, though we neglected to note which village, someone told us that the Mel people came from the Kraol people. The way that Mel people separated from Kraol is that one Kraol family was sleeping on a raft in a river, tied to the shore. In the night, the rope came untied and the raft drifted far down the river. The family never made their way back up the river, so they stayed downriver and their descendants are the Mel people.

One elderly man in the Roluos group interview said that Arach (from Paklae), Kachrouk (from Changhab), and Khaonh people are all Mel, but they separated from each other and were given different names. That was the only comment from any Mel people we talked to that suggested that Mel people see themselves as related to Khaonh people. Besides that, the only history the Roluos group interview participants shared was that they have lived in Roluos village ever since they were born.

Likewise, people in Changhab said all they know is that they were born in Changhab. The Changhab interview participants also agreed with the people from Srae Tahaenh that around 1942 or 1953 (we were given two different dates), some Mel people, about 23 families, left Changhab because of disease and made their way to Srae Tahaenh. They are the Mel people in Srae Tahaenh today.

People in Paklae ventured to say that they used to live in a different village, which, they explained, dissolved because of an outbreak of disease. Some of the people from that diseased village came to Paklae. We did not clarify where other people from that village went to, but we think the Paklae people said that some people from that village are in Ou Krieng village now.

We heard the most about history from the Khaonh people in Chhork village. In the group interview they said, “We have been here for a long time, from the time of our ancestors,” though it is not clear what they meant by “here.” They also remembered that at one point all the Khaonh people lived in one village, but when many people there died from disease, they divided into three groups. The Khmer Rouge then brought them all into one village again. After 1979 some Khaonh people moved to Kasang, Kaoh Dach, and Changkrang villages.

The Chhork village leader, his wife, and some others gathered informally outside their house. Prompted by hearing the recorded Paklae story,they told us that the people in Paklae are Khaonh people, and they explained how the Khaonh people came from Paklae to Chhork village. The Chhork village leader is ethnic Khmer (his wife is half Khaonh and half Bunong), and he is the one that told this story.

We asked two or three older people in Chhork village where the Khaonh people came from, in order to confirm the story, but none of them knew about the story. They said they did not know where the Khaonh people came from.

The people we talked to gave us mixed reports about the relationship between Khaonh people and Mel people. While one elderly man in the Roluos group interview said that the Mel and Khaonh used to be the same people, the Mel people in Paklae and Changhab did not recognize a shared history with Khaonh people. Mel people in Paklae and Changhab see the Khaonh as ethnically different, not just another variety of Mel. In Chhork village, while we were given the impression from the group interview that Mel people are not connected to Khaonh people, some of the individuals who took the

comprehension test have been to Mel villages where they have relatives. And, some of the people in Chhork told us the above story and said that Khaonh people came from Paklae in the past.

If the story about the couple fleeing Paklae to live near Ou Chhork is true, it may be, we speculate, that Mel people have distanced themselves from the couple and their descendants, the Khaonh people, in order to disassociate themselves from the curse resulting from breaking the taboo.

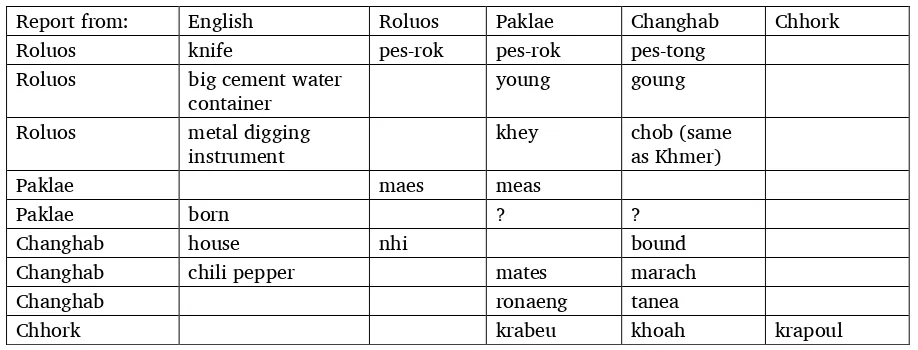

3.3 Perceived word differences

When the groups we interviewed were describing differences between ways of speaking, they sometimes gave examples of the different words people use. The group in Roluos explained that Mel people, especially in Changab, sometimes change the words they use in order to keep taboos about using certain people’s names. In table 12 are the words that the group interview participants said exemplify the differences between varieties. The words were first transcribed using Khmer script and then were transcribed from Khmer script to roman script using Khmer romanization rules, so the transcriptions are not phonetic.

Table 12. Examples of differences in words

Report from: English Roluos Paklae Changhab Chhork

Roluos knife pes-rok pes-rok pes-tong

Roluos big cement water

Changhab chili pepper mates marach

Changhab ronaeng tanea

Chhork krabeu khoah krapoul

3.4 Intelligibility between Mel and Khaonh varieties

To add to our understanding of how well people understand each other, in addition to what people reported about comprehension, we compared wordlists and did a comprehension test.

3.4.1 Lexical similarity comparison

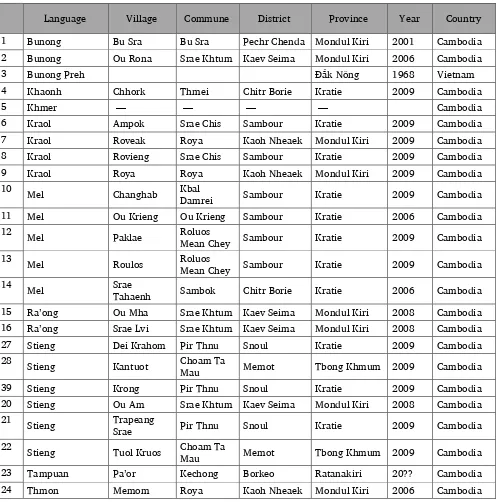

Table 13. Wordlists for lexical comparison

Language Village Commune District Province Year Country

1 Bunong Bu Sra Bu Sra Pechr Chenda Mondul Kiri 2001 Cambodia

2 Bunong Ou Rona Srae Khtum Kaev Seima Mondul Kiri 2006 Cambodia

3 Bunong Preh Đắk Nông 1968 Vietnam

4 Khaonh Chhork Thmei Chitr Borie Kratie 2009 Cambodia

5 Khmer — — — — Cambodia

6 Kraol Ampok Srae Chis Sambour Kratie 2009 Cambodia

7 Kraol Roveak Roya Kaoh Nheaek Mondul Kiri 2009 Cambodia

8 Kraol Rovieng Srae Chis Sambour Kratie 2009 Cambodia

9 Kraol Roya Roya Kaoh Nheaek Mondul Kiri 2009 Cambodia

10 Mel Changhab Kbal

Damrei Sambour Kratie 2009 Cambodia

11 Mel Ou Krieng Ou Krieng Sambour Kratie 2006 Cambodia

12 Mel Paklae Roluos

Mean Chey Sambour Kratie 2009 Cambodia

13 Mel Roulos Roluos

Mean Chey Sambour Kratie 2009 Cambodia

14 Mel Srae

Tahaenh Sambok Chitr Borie Kratie 2006 Cambodia

15 Ra’ong Ou Mha Srae Khtum Kaev Seima Mondul Kiri 2008 Cambodia

16 Ra’ong Srae Lvi Srae Khtum Kaev Seima Mondul Kiri 2008 Cambodia

27 Stieng Dei Krahom Pir Thnu Snoul Kratie 2009 Cambodia

28 Stieng Kantuot Choam Ta

Mau Memot Tbong Khmum 2009 Cambodia

39 Stieng Krong Pir Thnu Snoul Kratie 2009 Cambodia

20 Stieng Ou Am Srae Khtum Kaev Seima Mondul Kiri 2008 Cambodia

21 Stieng Trapeang

Srae Pir Thnu Snoul Kratie 2009 Cambodia

22 Stieng Tuol Kruos Choam Ta

Mau Memot Tbong Khmum 2009 Cambodia

23 Tampuan Pa’or Kechong Borkeo Ratanakiri 20?? Cambodia

24 Thmon Memom Roya Kaoh Nheaek Mondul Kiri 2006 Cambodia

Table 14 Lexical similarity percentages, 65–70 percent scale shading

Lexical Sim. 70 percent + Group

Kh S TK S KT KRY K RV K AP K RG Th M OK M RL M PK M CH M ST Kn S KG S DK S TS S OA R SL R OM B OR B BS B VN Tp

Khmer 100 29 31 34 33 32 32 30 29 31 28 32 29 33 29 27 29 27 25 19 20 20 17 26

Stienɡ – Tuol Kruos 29 100 89 71 70 72 73 67 71 70 69 71 72 67 78 78 75 65 69 72 60 59 64 43 Stienɡ – Kantuot 31 89 100 72 70 72 73 68 73 70 71 75 68 66 77 75 71 70 64 68 58 57 60 45

Kraol – Roya 34 71 72 100 99 98 96 82 71 74 72 72 70 73 78 81 81 71 70 69 64 62 63 53

Kraol – Roveak 33 70 70 99 100 96 95 81 70 73 71 69 69 73 76 77 78 70 67 68 64 61 61 52

Kraol – Ampok 32 72 72 98 96 100 99 80 75 78 75 75 71 78 78 80 78 70 69 69 63 63 64 52

Kraol – Rovieng 32 73 73 96 95 99 100 82 77 75 74 74 70 76 78 80 77 71 70 69 63 63 64 51

Thmon – Memom 30 67 68 82 81 80 82 100 78 75 71 73 73 73 74 76 78 77 76 78 74 75 68 49

Mel – Ou Krieng 29 71 73 71 70 75 77 78 100 98 94 89 86 90 79 80 84 82 78 81 72 75 68 50

Mel – Roluos 31 70 70 74 73 78 75 75 98 100 98 91 89 94 80 80 83 80 77 80 71 73 69 51

Mel – Paklae 28 69 71 72 71 75 74 71 94 98 100 93 83 88 80 80 81 77 73 77 69 71 64 48

Mel – Changhab 32 71 75 72 69 75 74 73 89 91 93 100 90 88 78 77 77 73 72 77 67 69 65 48

Mel – Srae Tahaenh 29 72 68 70 69 71 70 73 86 89 83 90 100 90 79 78 79 73 73 74 66 69 70 52

Khaonh – Chhork 33 67 66 73 73 78 76 73 90 94 88 88 90 100 82 82 83 76 73 77 70 70 70 54

Stienɡ – Krong 29 78 77 78 76 78 78 74 79 80 80 78 79 82 100 92 87 77 78 80 70 68 67 49 Stienɡ – Dei Krahom 27 78 75 81 77 80 80 76 80 80 80 77 78 82 92 100 95 81 80 81 72 68 68 52 Stienɡ – Trapeang Srae 29 75 71 81 78 78 77 78 84 83 81 77 79 83 87 95 100 83 83 83 71 71 70 53 Stienɡ – Ou Am 27 65 70 71 70 70 71 77 82 80 77 73 73 76 77 81 83 100 81 83 82 80 74 48

Ra’onɡ – Srae Lvi 25 69 64 70 67 69 70 76 78 77 73 72 73 73 78 80 83 81 100 95 86 83 80 48

Ra’onɡ – Ou Mha 19 72 68 69 68 69 69 78 81 80 77 77 74 77 80 81 83 83 95 100 85 84 78 51

Bunonɡ – Ou Rona 20 60 58 64 64 63 63 74 72 71 69 67 66 70 70 72 71 82 86 85 100 90 88 47 Bunonɡ – Bu Sra 20 59 57 62 61 63 63 75 75 73 71 69 69 70 68 68 71 80 83 84 90 100 88 43 Bunonɡ Preh—VN 17 64 60 63 61 64 64 68 68 69 64 65 70 70 67 68 70 74 80 78 88 88 100 45

Tampuan – Pa’or 26 43 45 53 52 52 51 49 50 51 48 48 52 54 49 52 53 48 48 51 47 43 45 100

To interpret the results, we follow Nahhas (Nahhas and Mann 2006) in supposing, as a starting point, that any two varieties sharing 70 percent or more lexical similarity might be intelligible to each other. Table 14 shows which wordlists group together at 70 percent or more lexical similarity. If 70 percent lexical similarity were a threshold for intelligibility, then all of the varieties compared, excluding Bunong, Tampuan, and Khmer, should be intelligible to each other. And the speakers represented by one wordlist, Stieng-Trapeang Srae, should be intelligible to speakers of all of the other presumably South Bahnaric varieties (all except Khmer and Tampuan). But, taking into account the following reports and measurements of comprehension, the lexical similarity threshold at which speakers of these varieties understand other varieties and include them in their language group is higher than 70 percent, probably closer to 90 percent.

1. All of the self-defined language groups (in labeled boxes in table 15), groups in which the speakers

represented by those wordlists consider each other to be comprehensible and part of the same language group, are at least 88 percent lexically similar, on average. The lexical similarity of all lists included in a self-grouping, averaged together, is 90 percent.

2. Below an average of 88 percent, no variety is included by the others as part of the same language

group or as comprehensible.

3. Around the margin of 88 percent average, inclusion in the language group may or may not be

universal and comprehension might be less than sufficient for sharing language materials.

• The two Stieng varieties from Memot District (Tbong Khmum Province), Tuol Kruos and

Kantuot, are 89 percent similar, and both identify each other as the Stieng people/language, and both say that the other speaks differently. But it is not clear how well they understand each other. The only other village which Kantuot people mentioned as similar to the way they speak was Kdol, but some Kantuot people said that they could not understand the way Kdol people speak. Comprehension between Stieng varieties in Memot District may be difficult to gauge because many Stieng people use Khmer mostly, or exclusively, and are not very proficient in understanding Stieng of any variety. Either variety of Stieng from Memot district is reportedly unintelligible (76 percent average lexical similarity) to Stieng speakers from Snuol District (Kratie Province), Krong, Dei Krahom, Trapeang Srae.

• Stieng in Snuol district (at 80 percent lexical similarity) is somewhat intelligible to Stieng

speakers in Kaev Seima district (Mondul Kiri Province), Ou Am, where they scored an average 86

percent on a comprehension test of a recorded story from Dei Krahom.6 Out of 25 people who

listened to the recording from Snuol, 18 said it was not their language.

• Mel and Khaonh are 90 percent similar, but their perceptions, discussed earlier in this report,

varied about whether the two varieties are intelligible, or are accepted as the same language group. People in Paklae and Changhab considered the Khaonh people to be different and their language not comprehensible. On the other hand, some Khaonh, though not all, thought the Mel language and people could be called their own. As discussed in section 3.4.2, Khaonh speakers scored an average 81 percent (marginal comprehension) on a comprehension test of a Mel-Paklae recording, and most of them thought it was different from Khaonh, though still good to listen to.

• Mel-Srae Tahaenh is only an average 87 percent similar with the other Mel varieties, but was

accepted in Roluos, Paklae, and Changhab (all the main Mel language areas) as being in the same Mel language group, and was considered to be spoken the same way as Mel is spoken in Changhab. It is therefore presumably as intelligible to the others as the Changhab variety. The Roluos people estimated they can understand about 70 percent of what Changhab people say,

and Paklae people reported that their children would only be able to understand “some” of what Changhab people say, as compared with the Roulous variety, which their children can

understand “well.” Changhab people said that Srae Tahaenh people speak exactly the same as they do, having come, for the most part, from Changhab.

• Bunong Preh-VN (Preh dialect from Vietnam) is 88 percent similar to the two Bunong lists from

Cambodia, and Bunong from Cambodia include it in their language group, though they distinguish between Bunong Preh and other varieties as different ways of speaking the same langauge.

Table 15. Lexical similarity percentages, 69–90 percent scale shading and self-grouping boxes

Lexical Sim. 69 percent–90 percent Scale

Kh S TK S KT K RY K RV K AP K RG Th M OK M RL M PK M CH M ST Kn S KG S DK S TS S OA R SL R OM B OR B BS B VN Tp

Khmer Kh 29 31 34 33 32 32 30 29 31 28 32 29 33 29 27 29 27 25 19 20 20 17 26

Stienɡ – Tuol Kruos 29 SM 89 71 70 72 73 67 71 70 69 71 72 67 78 78 75 65 69 72 60 59 64 43 Stienɡ – Kantuot 31 89 72 70 72 73 68 73 70 71 75 68 66 77 75 71 70 64 68 58 57 60 45

Kraol – Roya 34 71 72 K 99 98 96 82 71 74 72 72 70 73 78 81 81 71 70 69 64 62 63 53

Kraol – Roveak 33 70 70 99 96 95 81 70 73 71 69 69 73 76 77 78 70 67 68 64 61 61 52

Kraol – Ampok 32 72 72 98 96 99 80 75 78 75 75 71 78 78 80 78 70 69 69 63 63 64 52

Kraol – Rovieng 32 73 73 96 95 99 82 77 75 74 74 70 76 78 80 77 71 70 69 63 63 64 51

Thmon – Memom 30 67 68 82 81 80 82 Th 78 75 71 73 73 73 74 76 78 77 76 78 74 75 68 49

Mel – Ou Krieng 29 71 73 71 70 75 77 78 M 98 94 89 86 90 79 80 84 82 78 81 72 75 68 50

Mel – Roluos 31 70 70 74 73 78 75 75 98 98 91 89 94 80 80 83 80 77 80 71 73 69 51

Mel – Paklae 28 69 71 72 71 75 74 71 94 98 93 83 88 80 80 81 77 73 77 69 71 64 48

Mel – Changhab 32 71 75 72 69 75 74 73 89 91 93 90 88 78 77 77 73 72 77 67 69 65 48

Mel – Srae Tahaenh 29 72 68 70 69 71 70 73 86 89 83 90 90 79 78 79 73 73 74 66 69 70 52

Khaonh – Chhork 33 67 66 73 73 78 76 73 90 94 88 88 90 Kn 82 82 83 76 73 77 70 70 70 54

Stienɡ – Krong 29 78 77 78 76 78 78 74 79 80 80 78 79 82 SS 92 87 77 78 80 70 68 67 49 Stienɡ – Dei Krahom 27 78 75 81 77 80 80 76 80 80 80 77 78 82 92 95 81 80 81 72 68 68 52 Stienɡ – Trapeang Srae 29 75 71 81 78 78 77 78 84 83 81 77 79 83 87 95 83 83 83 71 71 70 53 Stienɡ – Ou Am 27 65 70 71 70 70 71 77 82 80 77 73 73 76 77 81 83 SK 81 83 82 80 74 48

Ra’onɡ – Srae Lvi 25 69 64 70 67 69 70 76 78 77 73 72 73 73 78 80 83 81 R 95 86 83 80 48

Ra’onɡ – Ou Mha 19 72 68 69 68 69 69 78 81 80 77 77 74 77 80 81 83 83 95 85 84 78 51

Bunonɡ – Ou Rona 20 60 58 64 64 63 63 74 72 71 69 67 66 70 70 72 71 82 86 85 B 90 88 47 Bunonɡ – Bu Sra 20 59 57 62 61 63 63 75 75 73 71 69 69 70 68 68 71 80 83 84 90 88 43

Bunong Preh – VN 17 64 60 63 61 64 64 68 68 69 64 65 70 70 67 68 70 74 80 78 88 88 45

Tampuan – Pa’or 26 43 45 53 52 52 51 49 50 51 48 48 52 54 49 52 53 48 48 51 47 43 45 Tp

Regardless of the exact relationship between lexical similarity and intelligibility among these languages, the lexical similarity comparison suggests that some varieties are more closely related than others. As mentioned above, groupings around 90 percent average, or above, match how people group themselves, generally. Thus, the 90 percent+ average similarity groups are:

1. Kraol [rka]. The four Kraol wordlists (the box in table 15 labelled ‘K’) average 97 percent with each

other. Kraol is relatively closest to Thmon (81 percent), followed by Stieng Snuol (79 percent),

Mel/Khaonh (73 percent), Stieng Memot (72 percent), and Stieng-Ou Am (71 percent).7

2. Thmon. The Thmon list is most similar to Kraol (81 percent), followed by Stieng-Ou Am and Ra’ong

(77 percent), Stieng Snuol (76 percent), Mel/Khaonh (74 percent), and Bunong (72 percent). This Thmon list is not taken from one of the main Thmon villages, but from Memom village, Khaoh Nheak District, Mondul Kiri Province, where Thmon people tend to use Bunong language more than

Thmon.8

3. Mel and Khaonh. Mel and Khaonh people do not all agree about whether they group together, thus

they are in different boxes (M and Kn) in the table, but they are in the same relative lexical

similarity grouping, at 90 percent between the two varieties, and all six lists are 91 percent average together. Mel/Khoanh is lexically closest to Stieng Snuol (80 percent), Stieng-Ou Am (77 percent), Ra’ong (76 percent), and Thmon (74 percent).

4. Stieng Snuol. Stieng from Snuol District in Kratie Province (the box labelled ‘SS’ in table 15) is

represented by the three Stieng lists from Krong, Dei Krahom, and Trapeang Srae villages, which are 91 percent similar, on average. The Stieng Snuol lists are relatively closest to Ra’ong (81 percent), Stieng-Ou Am (80 percent), Mel/Khaonh (80 percent), Kraol (79 percent), Thmon (76 percent), and Stieng Memot (76 percent). As can be seen from the block of lighter shading across the Stieng Snuol comparisons in table 15, Stieng Snuol is the group that has the highest average similarity with all of the other Bahnaric lists (78 percent).

• A Stieng list from Binh Phuoc Province in Vietnam also fits in this group, but it was not included

in the final comparison since it only contained 65–68 items in common with the other lists. While it is noted that the comparable data was scant for this list, it ranged in lexical similarity from 84 to 92 percent with the three Stieng Snuol lists.

5. Stieng-Ou Am. This wordlist is from Ou Am village in Kaev Seima District, Mondul Kiri Province,

and is most similar to Ra’ong (82 percent), Stieng Snuol (81 percent), Bunong (79 percent), Thmon (77 percent), Mel/Khaonh (77 percent), and Kraol (71 percent).

6. Ra’ong. The two Ra’ong lists from Srae Lvi and Ou Mha villages in Kaev Seima District, Mondul Kiri

Province, grouped themselves together (box R in the table), and were 95 percent similar.9 Ra’ong is

lexically most similar to the Bunong lists (83 percent), Stieng-Ou Am (82 percent), Stieng Snuol (81 percent), Thmon (77 percent), Mel/Khaonh (76 percent), and Kraol (69 percent). Ra’ong may be a blend or transition between Stieng and Bunong.

7. Bunong [cmo]. Speakers of Bunong represented by the three lists in this comparison group

themselves together as part of the same language group (box ‘B’ in table 16), and they average 89 percent lexical similarity together. Bunong is closest to Ra’ong (83 percent), Stieng-Ou Am (79

percent), and Thmon (72 percent).10

7 Stieng Ou Am, is the Stieng wordlist taken in Ou Am village, in Kaev Seima District, Mondul Kiri province. Stieng Memot is our grouping of varieties of Stieng in Memot District, Tboung Khmum Province, represented by the wordlists taken in Tuol Kruos and Kantuot. Likewise, Stieng Snuol is our grouping of the Stieng varieties in Snuol District, Kratie Province.

8 (Barr and Pawley 2013:xvii)

9 Ou Mha is a sub-division of Ou Am village.

8. Stieng Memot. The two Stieng lists from Memot district, Tbong Khmum Province, as mentioned above, are 89 percent similar, and group together lexically (box ‘SM’), though, again, it is not clear if they all agree that they are part of the same language group or how well they understand each other. These two Stieng lists are quite different from the other Stieng lists (76 percent average with Stieng Snuol), and they are more similar to Kraol (72 percent), Mel/Khaonh (70 percent), Ra’ong (68 percent), and Thmon (68 percent), than to Stieng-Ou Am (68 percent). They are 60 percent similar to Bunong.

9. Tampuan [tpu]. Tampuan is classified as Central Bahnaric (Lewis, Simons, and Fennig 2015), in

distinction from the above languages which are all presumably South Bahnaric. The groups closest to the Tampuan list are Kraol (52 percent), Stieng Snuol (51 percent), Mel/Khaonh (51 percent), Ra’ong (50 percent), and Thmon (49 percent). Tampuan and the three Bunong lists average 45 percent.

10. Khmer [khm]. Khmer shows a clear distinction with all of the Bahnaric languages in this analysis.

Khmer is most lexically similar to Kraol (33 percent), followed by Mel/Khaonh, Thmon, and Stieng Memot (30 percent), Stieng Snuol (28 percent), Tampuan (26 percent), Ra’ong (22 percent), and Bunong (19 percent).

11. In addition, a Chrau [crw] wordlist collected by David Thomas in 1972 was included initially in this

comparison, but the results are not included here because the list (from near Chonthan village, Binh Long Province, Vietnam) contained only 64–67 items in common with the other varieties. However, the preliminary results indicated that it may group by itself between Stieng-Tuol Kruos and

Tampuan. This variety of Chrau shows between 45 and 60 percent lexical similarity with the Bahnaric language varieties in this comparison.

Apart from the lists that group together around 90 percent or more similarity, the following varieties make relative groups:

• Kraol and Thmon

• Mel/Khaonh and Stieng Snuol

• Stieng Snuol, Stieng-Ou Am, and Ra’ong

• Stieng-Ou Am, Ra’ong, and Bunong

• Thmon, Mel/Khoanh, Stieng Snuol, Stieng-Ou Am, and Ra’ong (All the South Bahnaric groups

except for Stieng Memot, Kraol, and Bunong)

• And, as apparent in table 15, the largest two relative groups are 1) all the South Bahnaric groups

except for Bunong; and 2) all the South Bahnaric groups excluding Kraol and Stieng Memot.

As for grouping within the Mel variety itself, Roluos village is the most lexically similar (94 percent) to the other villages, and Srae Tahaenh village is the least similar (87 percent), less similar to the other Mel lists, on average, than Khaonh (90 percent).

3.4.2 Comprehension test