Zhilin Yang, Chenting Su, & Kim-Shyan Fam

Dealing with Institutional Distances

in International Marketing Channels:

Governance Strategies That

Engender Legitimacy and Efficiency

Firms doing business in foreign institutional environments face pressures to gain social acceptance (commonly referred to as legitimacy) and difficulty in evaluating market information, both of which undercut firm performance. In this article, the authors argue that firms can design governance strategies to deal with foreign institutions to secure both social acceptance and firm performance. Using a Chinese sample of manufacturers that export products to various foreign markets through local distributors, the authors develop and test a model that bridges the effects of institutional environments and governance strategy on channel performance. Specifically, they find that firms can use two governance strategies, contract customization and relational governance, to deal with both legitimacy and efficiency issues and to safeguard channel performance. Thus, international channel managers are advised to maintain an integrated management of legitimacy and efficiency in foreign marketing channels.Keywords: institutional distance, legitimacy pressure, market ambiguity, contract customization, relational governance, firm performance

Zhilin Yang is Associate Professor of Marketing (e-mail: mkzyang@ cityu. edu.hk) and Chenting Su is Professor of Marketing (e-mail: mkctsu@ cityu. edu.hk), College of Business, City University of Hong Kong. Kim-Shyan Fam is a Professor, School of Marketing & International Business, Victoria University of Wellington (e-mail: [email protected]). The authors thank Daniel Bello, Thomas Kramer, Thomas Madden, Shaohan Cai, Michael Hyman, David Tse, and Jan Schumann for their helpful com-ments on previous versions of this article. They also thank the three anonymous JMreviewers and Ajay Kohli for their invaluable guidance. The first two authors contribute equally. The authors gratefully acknowledge two grants from the Research Grant Council of Hong Kong SAR (9041618 and 9041715) and a grant from City University of Hong Kong (CityU SRG Project No. 7008124) for financial support. Ajay Kohli served as area edi-tor for this article.

For years, we have attempted to learn the business prac-tice in our clients’ country through the lengthy, sometimes painful contracting process. You know, once we build up good relationships with our local distributors, they usually are willing to help us understand the local market environ-ments and adapt our business practice to the local stan-dards for survival.

—Chinese export manager

F

irms managing international marketing channels face different institutional environments that necessitate firm conformance to local business practices to gain social acceptance (commonly referred to as legitimacy) (Eden and Miller 2004; Scott 2008). In addition, foreign institutions blur market information, which leads to firm difficulty in evaluating foreign markets (Martinez and Dacin 1999). Gaining social acceptance, however, may undercut firm efficiency (i.e., firm performance) because firms must invest to understand the local market and developcoopera-tive relationships with local distributors (Eden and Miller 2004; Zaheer 1995). Thus, firms doing business in foreign markets face a managerial challenge—namely, how to gain legitimacy while safeguarding efficiency.

Prior research has not investigated this managerial dilemma in an international marketing context. Neoinstitu-tional theorists provide a one-sided solution—that is, firm conformity to gain social acceptance for survival, regard-less of firm self-interests (Oliver 1991; Scott 2008). In this article, we provide a governance solution and argue that firms can design novel governance strategies to deal with foreign institutions. We address two essential research ques-tions: (1) What are the effects of institutional distances (i.e., the differences between the host and home institutional environments) on firm pursuit of local social acceptance? and (2) Can governance strategies, such as contracts and relational governance, function to gain both social accep-tance and firm performance? To answer these research issues, we introduce the notion of institutional distance as being based on the subdimensions of regulatory, normative, and cultural-cognitive distances in the context of interna-tional marketing channels.

leading to social acceptance. We also find that a given gov-ernance strategy can independently or jointly with other governance strategies safeguard firm performance. Thus, we link transaction cost economics (TCE) to an institutional perspective to shed light on such a legitimacy–efficiency challenge in international marketing channels.

We organize this article as follows: First, we present our conceptual framework and research hypotheses that bridge institutional and efficiency-based effects on channel perfor-mance. Second, we describe the research method and test our model using a Chinese sample of manufacturers that export products to various foreign markets through local distributors. Finally, we discuss the implications of the find-ings and provide directions for further research.

Conceptual Framework and

Hypotheses

Firms engaging in foreign marketing channels are con-strained by a set of foreign institutions encompassing rules, routines, conventions, and normative pressures (Oliver 1996; Scott 2008). They face two main challenges that undercut firm efficiency. First, they cannot foresee what will happen in the market because they are unfamiliar with the foreign institutional environments and are unable to evaluate market-related information (Eden and Miller 2004). Second, their potential host partners do not recog-nize them as socially fit partners because the locals do not know and trust them (Kostova and Zaheer 1999; Kumar and Das 2007). In other words, institutional distances in a for-eign market give rise to market ambiguity and legitimacy pressure, both of which directly or indirectly affect firm efficiency.

How to cope with both legitimacy and efficiency issues in foreign markets represents an underresearched area in international marketing. Typical institutional solutions emphasize firm conformity to gain legitimacy, regardless of firm self-interests (Scott 2008); in this article, we argue for governance solutions because they address the issue of effi-ciency (Williamson 1991). Theorists in TCE have proposed three governance strategies: hierarchy, contract, and rela-tional governance (Heide 1994; Ouchi 1980). Hierarchy

42 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

involves firm vertical integration, which separates the firm from market uncertainties. It is primarily an intrafirm solu-tion and thus is not applicable to governance between firms. Contract customization refers to the extent to which trans-action terms and clauses are tailored according to market conditions and transaction characteristics with a particular partner (Poppo and Zenger 2002; Zhou, Poppo, and Yang 2008). Relational governance relies on trust and social iden-tification, which creates shared behavioral expectations, such as flexibility, information sharing, and solidarity (Heide and John 1992).

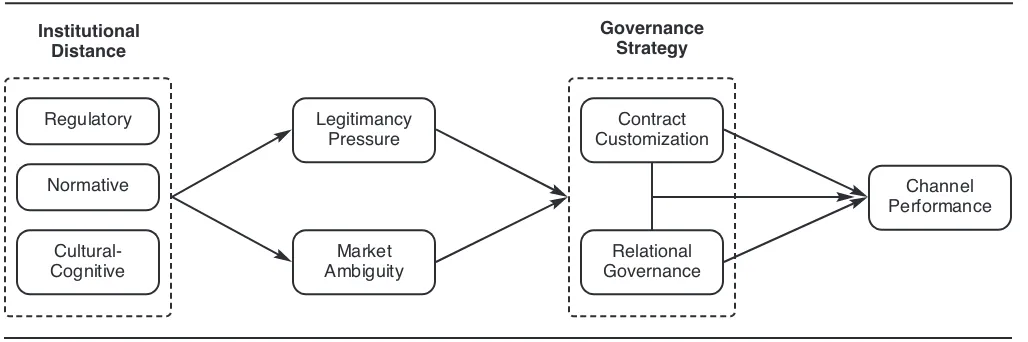

This study posits that the latter two interfirm gover-nance strategies that aim to secure external support and resources for firm performance can each function to miti-gate both the perceived legitimacy pressure and market ambiguity in a host market. We present our conceptual framework in Figure 1 and develop research hypotheses in light of the framework.

Institutional Distance and Its Key Consequences

Scott (2008) maintains that institutions possess three pillars: regulatory, normative, and cultural-cognitive. The regula-tory pillar pertains to a nation’s laws and regulations and delineates what organizations can orcannotdo. It uses legal sanctioning as the basis of legitimacy (Scott 2008). The normative pillar consists of beliefs, values, and norms that define desirable goals and expected behaviors to achieve them in a society. The legitimacy of normative institutions relies on societal beliefs and norms that specify what people

should orshould notdo (Eden and Miller 2004; Scott 2008). Rooted in cognitive psychology, the cultural-cognitive insti-tution emphasizes two important aspects of the shared knowledge, taken-for-granted conventions, and customs in a specific industry: (1) managers’ internal interpretive busi-ness practices, which is shaped by external cultural frame-works, and (2) their business knowledge, which is devel-oped over time through repeated social interactions (DiMaggio and Powell 1991; Kostova and Roth 2002). The legitimacy of this pillar is anchored in cultural orthodoxies that specify what people will typicallydo (Scott 2008).

Using Scott’s (1995) institutional framework, Kostova (1997) advances the concept of “institutional distance” and

Institutional Distance

FIGURE 1 Conceptual Model

Regulatory Legitimancy Pressure

Cultural-Cognitive

Market Ambiguity Normative

Contract Customization

Relational Governance

Channel Performance

defines it as the dissimilarity/similarity of the regulatory, nor-mative, and cultural-cognitive institutions between two coun-tries. Consistent with Martinez and Dacin (1999) and prior studies (Scott 2008; Williamson 1985), we identify the two key consequences of institutional distances as (1) legitimacy pressure to achieve acceptable business practice and (2) mar-ket ambiguity caused by foreign institutional environments.

Legitimacy pressure. First, institutional distances give rise to legitimacy pressure, which, as perceived by the entrant firms, is the degree to which firms are pressed to adopt acceptable business practices for survival in a host market (Scott 2008). Lack of legitimacy implies a lack of social support and resources from the local stakeholders because of a low recognition (Scott 2008). Thus, when con-sidering firm social acceptance, the foreign channel man-agers are concerned about unfamiliar aspects of the foreign legal codes and practices to avoid misbehaviors in the host country (Grewal and Dharwadkar 2002). For example, Chi-nese managers must be cautious about gift giving because it may violate antibribery laws in Western markets.

Second, normative distance may influence entrant firms’ normative legitimacy by affecting the way they embrace socially accepted norms and behaviors to avoid societal and professional sanctions (Selznick 1984). For example, Chi-nese managers may try to gain long-term developments by sacrificing short-term profits in their pricing decisions, which may affect their cooperative relationships with the host partners (Luo 2005). To gain normative legitimacy, therefore, a firm is pressed to participate in local channel decision making and share local business standards and practices.

Third, cultural-cognitive distance may affect firms’ social legitimacy through social interactions in which cul-tural cognitions and knowledge are embedded (Scott 2008). Although a firm’s boundary agents may hold different beliefs, they are strongly motivated to gain social legitimacy by developing friendships with local channel partners. For example, although many Western managers doing business in China find it difficult to assimilate the implicit “doctrine of the mean” that underlies the practice of guanxi(i.e., inter-personal relationships) (Park and Luo 2001; Su and Little-field 2001), they may not hesitate to adopt guanxi strategies to gain broader access to the vibrant China market.

Field interviews with Chinese exporting managers attest to such concerns with survival associated with the per-ceived legitimacy pressure in foreign markets. Specifically, labor policies, environmental protection regulations, indus-try norms, relationship building, working habits, and pro-fessional knowledge about channel management in a host market are among the more difficult things for these man-agers to understand. Therefore, we propose the following:

H1: Legitimacy pressure is positively affected by (a) regulatory distance, (b) normative distance, and (c) cultural-cognitive distance.

Market ambiguity. Institutional distances also increase market ambiguity, which in turn affects firm efficiency (Williamson 1985). To differentiate such institutionally induced market ambiguity from other types of market uncertainties, we define it as the degree of difficulty in

identifying, analyzing, and interpreting market-related information in the host institutional environments (Martinez and Dacin 1999; Scott 2008). Note that such market ambi-guity arises when firms lack knowledge and understanding of the foreign institutional environments; it represents one type of firm-specific uncertainty in which firms may differ in their perceptions of the same institutional environments (Beckman, Haunschild, and Phillips 2004).

Specifically, market ambiguity occurs when a manufac-turer conducts business with a foreign distributor with dif-ferent, seemingly unclear regulations, norms, and culturally distinctive business practices. Thus, the firm is unable to evaluate market-related information such as market trends and partner behavior. For example, Chinese managers may be less confident in interpreting and evaluating market information and predicting future market trends in a host country because they are unclear about how the foreign regulations and laws shape economic transactions (Luo 2005). Similarly, the foreign norms and codes of behaviors in a host market add to market ambiguity and make it diffi-cult for the entrant to judge the local channel member’s market actions and behaviors (Williamson 1985). For example, as mentioned, Western managers may be puzzled by guanxipractices and thus unable to determine the proper relationship behavior in China (Park and Luo 2001). Fur-thermore, foreign cultural-cognitive structures may hinder the managers’ ability to understand local consumer behav-ior and interpret market information. Thus, we propose the following:

H2: Market ambiguity is positively affected by (a) regulatory distance, (b) normative distance, and (c) cultural-cognitive distance.

Governance Strategies

Perceived legitimacy pressure and market ambiguity due to institutional distances invoke interfirm governance strategies, such as contract customization and relational governance, to safeguard firm performance in a host market. Contract customization enhances organizational learning, thus facili-tating cultural assimilation (Luo 2002). Relational exchange helps build trust that transforms foreign firms into “insid-ers” to gain both legitimacy and market information (Mar-tinez and Dacin 1999). We argue that the two interfirm gov-ernance strategies can function to deal with both efficiency and legitimacy issues in international channel management.

with a local partner helped legitimize his company’s behav-ior and enhance interfirm trust.

From the viewpoint of organizational learning, a cus-tomized contract also helps the suppliers learn acceptable business practices in a foreign market. When facing high legitimacy pressures, firms are motivated to gain local knowledge through the interactions embedded in contract drafting and negotiations. Such face-to-face communication often provides good opportunities for firms to learn local business norms, beliefs, and thinking styles. One Chinese manager commented that a detailed contract with cus-tomized terms and clauses helped her prevent wrongdoings and mistakes in the host market. In this sense, Argyres and Mayer (2007) argue that designing a customized contract produces a competitive capability by knowing how to adapt to each partner’s needs and conditions. Thus, legitimacy pressures in a host market motivate contract customization, which functions to facilitate mutual adaptation, mitigate dissimilarities between the entrant and the local partner, and ensure the former’s conformance to secure legitimacy. Thus:

H3: Contract customization is positively influenced by legiti-macy pressure.

Next, we hypothesize that market ambiguity also affects contract customization. As we noted previously, market ambiguity in a host market arises when foreign firms lack institutional knowledge about the host market. This lack of knowledge and understanding by the entrant firm implies an information asymmetry between the firm and its local partners because the local partners are better informed about the institutional aspects of the local market (Heide 1994). Such market ambiguity encourages opportunism because the foreign firm is unable to observe and/or verify its local partners’ actions. Thus, its partners have incentives to limit their efforts to fulfill the agreement, leading to undetected self-interest-seeking behavior (Williamson 1989).

In the presence of market ambiguity, a customized con-tract functions as an ex ante safeguard against partners’ opportunism because it legitimizes monitoring and adds more term specificity and contingency adaptability to the contract (Carson, Madhok, and Wu 2006; Luo 2002; Wathne and Heide 2000). For example, a customized con-tract enables firms to accurately measure and reward pro-ductivity (Mooi and Ghosh 2010; Poppo and Zenger 2002) and avoid performance risk by modifying goals, activities, and arbitration arrangements in advance (Oliver 1991). Our field interviews indicated that a majority of Chinese chan-nel managers, who perceived ambiguous market conditions and practices in a host market, proactively solicited a cus-tomized contract from their host partners to avoid perfor-mance ambiguity and safeguard their interests. Thus, we propose the following:

H4: Contract customization is positively influenced by market ambiguity.

Relational governance. Envisioning the disadvantage of doing business in a host market, the foreign channel man-agers may try to establish relational bonds with the local

44 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

partner to enhance social legitimacy. As strangers in a eign country, firms bear the predetermined “liability of for-eignness” that prevents them from doing business in an effi-cient way (Eden and Miller 2004; Zaheer 1995). To become insiders, firms, particularly manufacturers from emerging markets, are strongly motivated to build relationships with foreign distributors through cooperative actions, such as joint planning and the hiring of local personnel, to develop trust and gain local knowledge (Peng 2003; Xu and Shenkar 2002). Moreover, relational behaviors, such as information sharing, flexibility, and solidarity, provide a foundation for both sides to internalize and formalize their operations into legitimized practices (Heide and Wathne 2006; Poppo and Zenger 2002). Such embedded ties enhance the entrant firms’ ability to learn, understand, and adapt to the business practices of their trading partners’ country (Oliver 1996). For example, Western firms doing business in China are motivated to adopt guanxipractices to become friends with their local partners. In other words, relational governance can facilitate the process by which firms mimic their chan-nel partners to gain social acceptance.

H5: Relational governance is positively influenced by legiti-macy pressure.

Finally, market ambiguity may also encourage relational governance. As we mentioned previously, such institution-ally induced market ambiguity is firm specific because firms may possess different levels of knowledge about the same foreign institutional environments. Typically, when firms enter a new market or deal with an external partner, they experience uncertainty that is unique and internal to them (Greve 1996).

Previous empirical studies indicate that these firms are motivated to develop more extensive relational bonds, such as interlocking and alliance networks, with local partners to explore additional information (Beckman, Haunschild, and Phillips 2004). New information helps them make more informed decisions to deal with firm-specific uncertainty. This logic is consistent with Ouchi’s (1980) argument for clan-based governance, in which firm goals are aligned and cooperation is motivated on the basis of trust. In this clan-like dyad, partners are “insiders” that exchange tacit knowl-edge and private information to shed light on each other’s ambiguous areas (Ouchi 1980). As such, foreign firms experiencing market ambiguity may become insiders by adopting relational governance to foster interfirm informa-tion sharing, flexibility, and solidarity. Our field interviews indicated that Chinese exporting managers are strongly motivated to build guanxi with their local distributors to develop trust, which provides them with more access to the tacit knowledge and information about the local market, such as market trends and conventions of channel opera-tions. Therefore, we propose the following:

H6: Relational governance is positively influenced by market ambiguity.

Channel Performance

strat-egy to safeguard firm performance. A customized, formal agreement between channel members can exert a positive influence on performance outcomes. As we argued previ-ously, the process of creating the agreement assists in devel-oping more robust interfirm communication based on a set of shared rules, procedures, responsibilities, and expecta-tions, which in turn help clarify institutional misunderstand-ings and reduce adaptation costs (Mooi and Ghosh 2010). With a contact, both parties are likely to devote attention to contractual arrangements and work out any issues before they become serious, thus saving transaction costs (Williamson 1985; Zhou, Poppo, and Yang 2008).

Conversely, relational governance leads channel mem-bers to relational norms, in which they solve problems together, share fine-grained information, and provide flexi-bility or make adequate adaptations for conditions in which unusual events might occur (Heide and John 1992; Zhou, Poppo, and Yang 2008). Consequently, economic transac-tions in a host market may reduce both negotiation and con-tract costs by enhancing shared expectations and market information costs by providing insider status (Luo 2002; Mooi and Ghosh 2010).

We further argue that contract customization and relational governance may serve as complements in a foreign market (Poppo and Zenger 2002). Prior research has postulated that trust may supplant contracts in suppressing opportunism, whereas contracts may also undermine relational norms. Thus, contracts and relational governance function as substitutes (Gulati 1995; Macaulay 1963). However, as we argued previously, the two governance strategies both function to facilitate organizational learning and secure external support and resources for firm perfor-mance. Contract customization facilitates cultural assimila-tion through organizaassimila-tional learning (Luo 2002); relaassimila-tional exchange transforms foreign firms into insiders to gain both legitimacy and market information (Martinez and Dacin 1999). When trust develops, foreign distributors are more willing to comply with terms contained in contracts, and when contracts are well customized, opportunism is less likely to occur. Thus, the effect of a given governance strat-egy on firm performance is greater when it functions in conjunction with another governance strategy rather than in isolation (Poppo and Zenger 2002).

Specifically, when the contractual terms and clauses are well specified and articulated, firms operate in a context of information symmetry and perceived fairness; a trusting, interfirm relationship coupled with such a customized con-tract leads to a lower likelihood of concon-tract breach and/or renegotiation, saving ex post transaction costs (Luo 2002; Mooi and Ghosh 2010). In contrast, when firms develop relational bonds with their local partners, a customized con-tract coupled with relational norms provides a roadmap for fulfilling mutually agreed-on responsibilities and dealing with necessary adaptations in an exchange, leading to lower opportunism and saved monitoring costs (Luo 2002; Williamson 1991). Studies have also shown that customized contracts function to reduce opportunism only in conjunc-tion with relaconjunc-tional closeness (e.g., Mooi and Ghosh 2010). In other words, in a foreign market, contract customization

and relational governance may combine to better safeguard firm performance.

H7: Channel performance is positively affected by (a) contract customization, (b) relational governance, and (c) their interaction effects.

Methodology

Data Collection

We tested the hypotheses using a sample of Chinese manu-facturing firms that export products to various countries through foreign distributors. We undertook a systematic random sampling of 1480 manufacturers, based on a list of manufacturing firms in the four-digit Standard Industrial Classification codes 2011–3899 and located in Beijing, Guangzhou, and Shanghai. A national market research firm headquartered in Shanghai with nationwide branches and affiliates was commissioned to conduct the survey through personal interviews.

For the purpose of this research, we established three criteria to select qualified companies. First, the company must be neither foreign owned nor a joint venture, and its senior managers must be native Chinese. We thus reduced the dual effect that might result from cross-cultural manage-ment on evaluations of institutional distances (Kostova and Roth 2002). Second, the company should have an overseas distributor that purchases parts or components at least twice a year. Third, the distributor should not belong to the same company/group or parent company to exclude vertical inte-gration. Qualified senior managers were first contacted by telephone to solicit their cooperation. Of the 600 companies whose managers verbally agreed to participate, 436 man-agers from 218 firms were successfully interviewed on-site. For each firm, we selected two senior managers (e.g., chief executive officer, vice president of sales, export manager) as key informants because of their revealed heavy involvement with their firms’ major distributors. These informants first selected the overseas distributor with which their firm conducted the greatest volume of business. They then answered the survey questions according to their rela-tionships with the chosen distributor. All subjective infor-mation, such as perceived institutional distances, relational governance mechanisms, and the performance measure, was based on multiple informant data. In line with Kumar, Stern, and Anderson (1993), respondents provided data only on the attributes they believed they had the ability to evalu-ate. The mean confidence scores for knowledge about the institutional environments of the country in which their dis-tributor was located and the interfirm relationships were 4.21 (on a five-point scale; SD = .68) and 4.29 (SD = .68), respectively. For items with data from two informants, we pursued the response data-based weighted mean approach to determine a value for each item (for detailed procedures, see Van Bruggen, Lilien, and Kacker 2002).

rate of 34.2% (205 of 600). A comparison of the respon-dents and nonresponrespon-dents using t-tests indicated no signifi-cant differences in terms of key firm characteristics (i.e., industry types, locations, number of employees, and annual sales revenues), suggesting that nonresponse bias is not a major concern for this study.

The final sample consisted of 205 firms across the major Standard Industrial Classification groups within the manufacturing division, spanning various industrial sectors. Of the companies, 82% had annual sales revenues of more than US$3 million, and 62.3% employed between 100 and 500 people. In addition, 35.6% of the sampled firms were state owned, 48.2% were private, and 16.2% were listed stock companies. These companies exported to 14 regions/ countries, including Germany, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, the United States, Hong Kong, Singapore, Malaysia, the United Kingdom, Australia, Canada, France, Thailand, and the Philippines. The first 9 countries are among China’s top trading partners.

Measures

Except for institutional distances, legitimacy pressure, and market ambiguity, we adapted all the multi-item measures used in the survey from established studies. Two researchers educated in both the United States and China translated and back-translated all the measures to ensure conceptual equiv-alence (Hoskisson et al. 2000). To further ensure content and face validity of the measures, we made personal trips to conduct five in-depth interviews with senior export man-agers arranged by the market research firm. On the basis of their responses to the relevance and completeness of the measures, we revised a few questionnaire items to enhance clarity. In addition, we conducted a pilot study with 50 export managers, in which the respondents both answered the questionnaire and provided feedback on the design and wording of the questionnaire. As a result, we modified sev-eral items in line with the feedback from the export man-agers. We present these measures in the Appendix.

Institutional distances. Institutional profiles tend to be issue specific and difficult to generalize across domains (Busenitz, Gomez, and Spencer 2000; Kostova 1997; Kos-tova and Roth 2002). Thus, we adopted KosKos-tova’s (1997) approach and developed an instrument to measure the three perceived institutional distances in the eyes of the channel managers. First, regulatory distance pertains to laws and rules that influence business strategies and operations in marketing channels, reflecting regulatory processes such as rule setting, monitoring, and sanctioning activities (Scott 1995). We drew a list of ten regulatory-related institution items from the Global Competitiveness Report, which is published annually by the World Economic Forum and has been increasingly used in studies on international business (Delios and Beamish 1999). Using feedback from the per-sonal interviews with senior managers, we selected six items most relevant to the regulatory aspects of channel management. These items pertain to enforceability of busi-ness laws, impartiality of arbitration, disputes settlement, intellectual property protection, institutional stability, and number of regulatory bodies of enforcement.

46 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

Second, normative distance refers to the differences in values and norms toward practices of channel management between two countries. Although prior research has used Hofstede’s (1980) dimensions of culture as a proxy of the normative environment, we concur with Kostova’s (1997) claim that it is better to develop a measure specific to channel management. Drawing from the findings of our focus group studies and literature review, we adapted five items to repre-sent norms and values relevant to channel management prac-tice: norms of cooperation among channels, societal-level trust, association intensity, moral obligation to provide quality products and services, and standards of business conduct.

Third, cultural-cognitive distance refers to social knowl-edge and skills that professionals possess and share in oper-ating channels (Busenitz, Gomez, and Spencer 2000). To measure the channel professionals’ knowledge and skills, we used the following aspects: channel management prac-tice, ability to implement programs of efficient channel management, customs of channel operations, business envi-ronment related to channel management, and shared beliefs in the area of transnational channel management. All items of the three distances except one reached a factor loading of .70 or greater. We eliminated the item with a low factor loading (i.e., institutional stability from the regulatory per-spective) from further analysis.

Legitimacy pressure. In line with the definition of legit-imacy (Suchman 1995), we measured legitlegit-imacy pressure by asking export managers to evaluate the degree to which their trading partners pressure them for (1) desirability, (2) properness, and (3) appropriateness of business practice in accordance with the institutional environment in a foreign market. We conceive market ambiguity as being institution-ally induced.1 Following Martinez and Dacin (1999), we operationalized market ambiguity as the difficulty of pro-cessing market information because of the host institutional environments. We explicitly asked the respondents to con-sider this construct in the host institutional environments to capture the tacit nature of such uncertainties. Three items measure the essential aspects of market ambiguity: informa-tion analysis, interpretainforma-tion, and evaluainforma-tion.

Governance strategies. We measured contract customiza-tion using three items, adapted from Cannon and Perreault (1999), that reflect the specificity, formality, and details of contractual agreements between manufacturers and their for-eign distributors. Relational governance is based on the use of shared norms to monitor and coordinate the behaviors of the exchange partners (Macneil 1980), and therefore we operationalize it as a three-dimensional construct consisting of information sharing, flexibility, and solidarity (Heide and John 1992; Jap and Ganesan 2000; Zaheer and Venkatra-man 1995). Consistent with Jap and Ganesan (2000), we measured relational governance as a higher-order factor.

Channel performance. We adopted Bello and Gilliland’s (1997) export channel performance measures, which encom-pass three aspects: strategic, selling, and economic perfor-mance. Strategic performance pertains to the firm’s market-ing, distribution, promotion, and pricing strategy for foreign markets. Selling performance involves maintaining contact with customers, calling on customers in person, and servic-ing customers after the sale. Economic performance consists of economic, sales, growth, and profit goals for foreign mar-kets. Following Bello and Gilliland’s approach, we averaged the items for each construct to form three performance scales, which served as the indicators of the export channel perfor-mance. We tested the unidimensionality of each performance construct and the model fit using a three-construct confir-matory factor analysis (CFA). Consistent with Bello and Gilliland’s study, we find that the three-construct approach represents channel performance well (see the Appendix).

Controls. We controlled for four sets of variables. First, we controlled for three types of exchange characteristics according to TCE: asset specificity, environmental volatility, and transaction frequency (Heide 1994; Poppo and Zenger 2002; Williamson 1985). We adapted items from Heide and John (1992), John and Weitz (1989) and Cannon and Per-reault (1999), and Anderson (1985), respectively, to mea-sure the three constructs. Second, we controlled for firm size, measured as the number of employees in a company, because it may significantly influence organizational behaviors and decisions. Third, prior studies have shown that transaction history is essential to the relationship between organizations and the development of cooperative norms (Gundlach and Murphy 1993). We used partners’ number of years in business together to indicate history of transaction. Fourth, we controlled for the effects of state-owned manufacturers, an important institutional factor in China (Park and Luo 2001), using a dummy variable that equals 1 if the firm is state owned and 0 if otherwise.

Construct validity. We refined the measures and assessed their construct validity following the guidelines Anderson and Gerbing (1988) suggest. First, we ran exploratory factor analyses for each multiple-item variable, which resulted in factor solutions as theoretically expected. Second, reliability analyses show that these measures possessed satisfactory coefficient reliability. Third, we ran CFA for each of the three sets of constructs (i.e., institutional distances; legiti-macy pressure, market ambiguity, and governance strategies; and performance and controls), as well as an overall 15-factor model with all the variables. The confirmatory models all fit the data satisfactorily (see the results of the CFA in the Appendix), indicating the unidimensionality of the measures (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). All factor loadings were highly significant (p< .001), and the composite reliabilities of all constructs were greater than .70 (Bagozzi and Yi 1988). Thus, these measures demonstrate adequate conver-gent validity. Table 1 presents the means, standard devia-tions, and correlations of the constructs.

We assessed the discriminant validity of the measures in two ways. First, none of the confidence intervals of the cross-construct correlations contained a value of 1 (p< .01), signi-fying the discriminant validity of these measures (Anderson

and Gerbing 1988). Second, we ran chi-square difference tests for all the multiple-item scales in pairs (38 tests) to test whether the restricted model (the correlation fixed to 1) was significantly worse than the freely estimated model (the correlation estimated freely). All the chi-square differences were highly significant (e.g., in the test for distributor importance and contract customization: 2(1) = 165.24, p= .000), providing additional evidence for discriminant validity (Anderson and Gerbing 1988). Overall, the measures in this study possess satisfactory reliability and validity.

Common Method Bias Assessment

For the subjective measures in our study, we used two infor-mants to increase the reliability and validity of the measures (Kumar, Stern, and Anderson 1993). However, common method variance may still exist when, in some cases, one respondent provides answers to most of the variables (Pod-sakoff et al. 2003). When this happens, any unusual vari-ance resulting from the respondent may be reflected in all the measures. In addition to the procedural controls for the survey, such as anonymous submission and minimization of the ambiguity of the measurement items, we employed the marker variable assessment technique approach that Lindell and Whitney (2001) recommend to assess common method bias. We added an item pertaining to product technical com-plexity (from not technically complex to extremely techni-cally complex), which had either no significant or very low correlations with the variables in our study. The results of a partial correlation analysis after we controlled for the effect of product technical complexity show no significant change among the important constructs. Finally, of the 36 correla-tions between the nine constructs in the model, 8 were not significant, and 4 of these 8 were negative, indicating the validity of the other correlations (Lindell and Brandt 2000). Our collected evidence suggests that the effect of common method variance is unlikely to be significant.

Results

Level of Analysis

48

/

Journa

l

of

M

ark

et

ing,

M

ay

2

01

2 TABLE 1

Means, Standard Deviations, and Correlations for the Constructs

Construct 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17

1. Regulatory distance .92

2. Normative distance .61 .89

3. Cultural-cognitive distance .48 .55 .83

4. Asset specificity –.10 –.08 –.15 .90

5. Environmental volatility –.07 –.16 –.19 .38 .81

6. Transaction frequency –.08 –.07 –.10 .09 .27 .—

7. Contract customization .22 .29 .31 .28 .23 –.18 .89

8. Relational governance .28 .32 .37 .17 .18 .22 .18 .89

9. Distributor importance .08 .06 .05 .42 .39 .09 .25 .32 .94

10. Legitimacy pressure .26 .37 .44 .16 .19 .11 .18 .35 .16 .92

11. Market ambiguity .29 .39 .51 .31 .26 –.09 .19 .37 –.05 .38 .89

12. Channel performance –.05 –.08 –.11 .07 –.18 .08 .15 .21 .30 –.19 –.16 .87

13. Manufacturer type .06 .01 –.05 –.06 –.02 –.05 .06 –.02 –.04 .06 .01 –.03 .— 14. Location of partners .23 .31 .33 –.01 .10 –.03 .05 –.02 –.06 .09 .03 –.05 .04 .— 15. Technical complexity –.02 –.04 –.07 .08 .02 –.03 .05 –.04 .01 .08 .11 .05 –.01 –.03 .— 16. History of transaction –.02 –.01 .05 .10 .11 .08 –.03 .19 .11 –.06 .00 .15 –.05 –.05 –.05 .— 17. Firm size –.03 –.05 .04 –.16 –.02 .11 –.08 .03 –.06 .08 –.05 –.06 .10 .10 .10 .11 .— M 2.84 2.91 3.05 4.10 3.31 2.10 3.65 4.51 4.03 4.11 3.98 3.64 .08 .44 3.08 2.84 4.15 SD .70 .72 1.12 .88 .67 .86 .65 1.21 .68 .85 1.01 .51 .31 .50 .85 1.06 1.57

Endogeneity Tests

Because managers were not randomly assigned to various export-partner countries in which they reported their per-ceptions of legitimacy pressure and market ambiguity, both constructs may be correlated with unobserved factors (e.g., managers’ selection of exporting products) other than the three institutional distances. Such omitted variables cause endogeneity problems that produce biased and inconsistent coefficient estimators (Wooldridge 2003). To address this concern, we employed the instrumental variable (IV) method by introducing one variable, location of trading partners; we measured it as a dummy variable that equals 0 if the trading partner is located in Asia and 1 if otherwise. Location of trading partners meets the two requirements of a valid IV (Wooldridge 2003).

First, it is correlated with all three distances (see Table 1). Conceptually, geographic distance is associated with institutional distances (Ghemawat 2001). Second, it is not correlated with error terms in the model. We followed Hausman’s (1978) approach and compared the OLS and two-stage least square estimates of both legitimacy pressure and market ambiguity to determine whether they are consis-tent. Specifically, we regressed the three distances on the instrument and then plugged the fitted values into the main regression equations of legitimacy pressure and market ambiguity. Location of trading partner’s country had a sig-nificant, positive effect on the three distances (= .25, .32,

.38, for regulatory, normative, and cultural-cognitive dis-tance, and p< .05, .01, and .01, respectively). The compari-sons of the OLS and IV estimates show that endogeneity exists for legitimacy pressure but not for market ambiguity. When we regressed legitimacy pressure on the three dis-tances, the coefficients of IV estimates were significantly larger than those of the OLS estimates. Thus, to address the endogeneity of legitimacy pressure, we include the IV in the subsequent model test.

We tested our hypotheses using path analysis for two reasons. First, there are two formative constructs, relational governance and export channel performance. Therefore, it is more suitable to use path analysis than the structural equation modeling approach. Second, our model consists of 13 constructs with 205 effective samples; the ratio is less than 15 per construct, the minimum number required for structural equation modeling. In the path analysis model, the constructs were represented with the average scores of their indicators. For relational governance and channel per-formance, we used the average score of each subconstruct as their indicator. The model also included the IV, location of trading partners, and the interaction between contract customization and relational governance. The fit indexes indicate satisfactory model fit for the path analysis model (see Table 2).

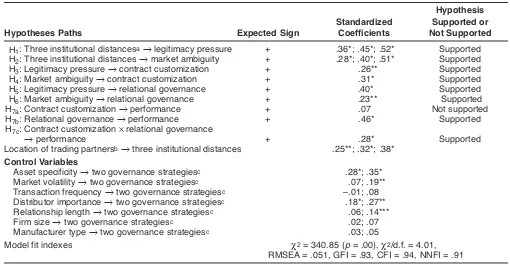

As Table 2 shows, H1is supported, indicating that the three institutional distances significantly affect legitimacy

TABLE 2

Results of Path Analysis

Hypothesis Standardized Supported or Hypotheses Paths Expected Sign Coefficients Not Supported

H1: Three institutional distancesaÆlegitimacy pressure + .36*; .45*; .52* Supported H2: Three institutional distances Æmarket ambiguity + .28*; .40*; .51* Supported H3: Legitimacy pressure Æcontract customization + .26** Supported H4: Market ambiguity Æcontract customization + .31* Supported H5: Legitimacy pressure Ærelational governance + .40* Supported H6: Market ambiguity Ærelational governance + .23** Supported H7a: Contract customization Æperformance + .07 Not supported H7b: Relational governance Æperformance + .46* Supported H7c: Contract customization ¥relational governance

Æperformance + .28* Supported

Location of trading partnersbÆthree institutional distances .25**; .32*; .38*

Control Variables

Asset specificity Ætwo governance strategiesc .28*; .35* Market volatility Ætwo governance strategiesc .07; .19** Transaction frequency Ætwo governance strategiesc –.01; .08 Distributor importance Ætwo governance strategiesc .18*; .27** Relationship length Ætwo governance strategiesc .06; .14*** Firm size Ætwo governance strategiesc .02; .07 Manufacturer type Ætwo governance strategiesc .03; .05

Model fit indexes 2= 340.85 (p= .00), 2/d.f. = 4.01, RMSEA = .051, GFI = .93, CFI = .94, NNFI = .91

*p< .01. **p< .05. ***p< .1.

aThree institutional distances refer to regulatory, normative, and cultural-cognitive distance, respectively. bInstrumental variable.

cTwo governance strategies: contract customization and relational governance.

pressure ( = .36, .45, .52, respectively; p< .01). H2 pre-dicts that all three distances have a significant impact on market ambiguity. The effect strength provides preliminary support for H2(= .28, .40, .51, respectively; p< .01). H3, which predicts that legitimacy pressure affects contract cus-tomization, is also supported (= .26, p< .05). The effect of market ambiguity on contract customization is positive and significant ( = .31, p < .01), in support of H4. The results also show a positive and significant effect of legiti-macy pressure on relational governance (= .40, p< .01), in support of H5. Consistent with H6, the results show that market ambiguity increases the use of relational governance (= .23, p< .05).

Finally, contract customization is not significantly related to channel performance (= .07, p> .1). Thus, H7a is not supported. Relational governance has a positive and significant effect on channel performance (= .46, p< .01), in support of H7b. In terms of a synergistic effect of contract customization and relational governance on performance, the results show a significant, positive interaction effect ( = .28, p< .01). Thus, contract customization and relational governance combine to enhance channel performance, in support of H7c.

In terms of the effects of the control variables, the most significant influence on relational governance comes from asset specificity, followed by environmental volatility, importance of the distributor, and relationship length. For contract customization, both asset specificity and impor-tance of the distributor have significant and positive effects. Overall, the findings are consistent with TCE and institu-tional theory, in support of our position that both theories can contribute to the choice of governance mechanisms.

Discussion

Firms engaging in an institutionally different host market are pressed to gain social acceptance for survival; yet obtaining legitimacy may also incur additional costs of adaptation and market assessment that undercut firm efficiency (Eden and Miller 2004). Thus, firms doing business in a foreign mar-ket are challenged by the managerial dilemma of how to gain legitimacy while safeguarding efficiency.

By combining TCE and institutional theory, we investi-gate this managerial dilemma. We argue that as strategic responses to foreign institutions, firms can design novel governance strategies to deal with both legitimacy and effi-ciency issues in a host market. In the context of international marketing channels, we find that institutional distances (i.e., regulatory, normative, and cultural-cognitive differences) lead to firms’ perceptions of legitimacy pressure and market ambiguity, which in turn invoke firm governance choices to safeguard performance. Specifically, we find that firms can use two interfirm governance strategies, contract cus-tomization and relational governance, to cope with both legitimacy and efficiency concerns and to safeguard firm performance. As such, we fill a gap in which firms facing legitimacy pressures in a host market have been provided with only institutional solutions, that is, conformity to gain social acceptance, regardless of firm self-interests (Oliver 1991). Our results indicate that firms also can use

gover-50 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

nance strategies to safeguard performance while seeking social acceptance. Thus, we contribute to the emerging lit-erature that tries to combine institutional theory and TCE to examine both firm legitimacy and efficiency issues in a host market (Martinez and Dacin 1999; Roberts and Greenwood 1997).

A significant theoretical implication of this study is that a given governance mechanism can serve dual purposes, such as dealing with both legitimacy and efficiency issues. This is because both interfirm governance strategies, as we argued previously, function to build cooperative relation-ships with local partners in a host market. Such interfirm relationships facilitate local adaptation and add to firms’ access to social support and resources, thus enhancing both firm legitimacy and efficiency (Eden and Miller 2004; Oliver 1996).

As such, our empirical results suggest a governance solution to a long-standing paradox faced by neoinstitu-tional theorists: In the pursuit of legitimacy, firms may give up their efficiency and heterogeneity, whereas in the pursuit of efficiency, firms may not attend to some stakeholder interests (Fernández-Alles and Valle-Cabrera 2006). Our results show that firms can use either interfirm governance strategy to address both legitimacy and efficiency concerns in a host market. For example, firms may choose to be legally or socially embedded by forming a legal or rela-tional bond with their host partners. Both types of embed-ded ties function to mitigate dissimilarity and enhance interfirm trust through personal interactions and organiza-tional learning (Granovetter 1985), thus adding to both firm legitimacy and efficiency. However, our results show a positive interaction effect of the two governance strategies on firm performance. Thus, firms can combine these two governance strategies to better attain both legitimacy and efficiency in a host market.

Managerial Implications

Channel managers are driven to establish legitimacy while pursuing efficiency in a host market. However, legitimacy and efficiency should not be contradictory objectives in firms’ management processes. In light of our findings, effi-ciency may follow legitimacy through greater access to local resources (Fernández-Alles and Valle-Cabrera 2006; Oliver 1996). As we noted previously, good relationships with stakeholders, through either legal or social embedded-ness, can translate into new competitive advantages that lead to firm efficiency. Therefore, channel managers should maintain an integrated management of legitimacy and effi-ciency in a foreign market.

sense of the institutional environments. Though often used to circumvent institutional barriers, we find that contract customization does not exert significant direct influence on channel performance, perhaps because of the high cost of concessions in a contract. Channel managers should be aware of the limits of drafting a customized contract for achieving channel performance. As our results show, only when it is combined with relational governance can con-tract customization enhance channel performance in a for-eign market (Mooi and Ghosh 2010).

Alternatively, relational governance helps firms miti-gate legitimacy pressures and market ambiguity through information sharing, flexibility, and solidarity. Managers should build relational bonds with the local partners to become insiders to gain both legitimacy and accurate mar-ket information, which lead to enhanced firm performance. In a Chinese context, guanxi plays an important role in transforming outsiders into insiders (Su and Littlefield 2001). Thus, firms should empower their boundary span-ners to develop friendship with local distributors to gain trust and inside market information.

Further Research

This study has several limitations that deserve further research. We collected data only from the manufacturer side of a channel dyad. Future studies might gather data from both manufacturers and distributors. This bilateral approach would provide more information about the dynamic nature of international channel management. In addition, the gen-eralization of our findings should be viewed with caution because the manufacturers in our sample are primarily engaged in indirect exporting from an emerging market. To verify the current model in a more complicated institutional environment, studies should sample manufacturers that pur-sue direct exporting or manufacturers that face dual institu-tional pressures (i.e., business market and consumer mar-ket) in foreign countries.

As previously mentioned, we tested the model using the organizational-level measure of institutional distances. Fur-ther research might collect data from various countries with a large sample to aggregate data at the national level. In doing so, both the direct and cross-level effects of institu-tional distances on the relationships in the model could be examined thoroughly.

Another concern with generalization of our findings pertains to the relationship stage of the trading partners. Although we controlled for the length of business

relation-ship and the strength of the relationrelation-ships varied among the sample, the manufacturers we surveyed tended to have good business relationships with their distributors. Because of this, the export managers, as our pretest revealed, were able to answer questions related to various, often deep lev-els of institutional environments. However, these incum-bents’ perceptions of institutional environments and resul-tant consequences may differ from those of new entrants or less important partners. Thus, research might further explore the influence of institutional distances on channel governance strategies from the perspective of different types of channel members in various stages of the relation-ship cycle.

Three limitations related to measures are also worth mentioning. First, we attempted to use a variety of methods to capture the essential domain of institutions, but new and different approaches would be desirable to fully uncover cultural-cognitive institutional models (Scott 1995). Further-more, although we believe that the instrument developed in this study reflects the essential differences in terms of the three institutional dimensions, future studies might devote efforts to uncovering the full picture of channel-specific insti-tutional profiles through, for example, unconventional meth-ods such as semiotics and narrative analysis (see Scott 1995). Second, we measured market ambiguity as institutionally induced. A more general measurement without specifying such institutional inducement might generate more robust effects of the institutional distances on market ambiguity.2

Third, we measured legitimacy pressure as a unidimen-sional construct for two reasons: (1) The focus groups indi-cated that channel managers understood the concept as a whole rather than in parts, and (2) although there is much theorizing on the topic of legitimacy, empirical measures of the construct are rare in marketing channels. However, decomposing legitimacy into several aspects related to institutional constraints might reveal more insights into its influence on the choice of governance strategies.

2We conducted an additional test by replacing the current mar-ket ambiguity measure with the new measure, as described in note 1, in the model. The empirical results showed similar patterns except for slightly different coefficients. Specifically, the sizes of the coefficients of the three distances on market ambiguity are slightly smaller for regulatory (.22, p< .05), normative (.29, p< .01), and cultural-cognitive (.42, p< .01) distance than those in the current model. In addition, the effects of market ambiguity on con-tract customization (.49, p< .01) and relational governance (.32, p< .01) are relatively larger than those in the current model.

Institutional Distances(2(45) = 71.25, p< .001; GFI = .95; CFI = .96; IFI = .97; RMSEA = .051)

Regulatory Distance

CR = .87, AVE = .71 New scale

(1 = “not different at all,” and 5 = “completely different”)

Please indicate the magnitude of difference of the following regulatory aspects related to channel management between your distributor country and your home country:

1. Enforceability of business laws. (.78a) 2. Impartiality of arbitration. (.76)

3. Effectiveness of dispute settlement. (.75) 4. Intellectual property protection. (.81) 5. Institutional stability.b(.48)

6. Number of regulatory bodies that enforce channel management. (.71)

52 / Journal of Marketing, May 2012

Normative Distance

CR = .86, AVE = .68 New scale

(response anchor same as for Regulatory Distance)

For each of the following items concerned with social accepted norms and values channel professions are expected to hold, please indicate the magnitude of difference between your distributor country and your home country.

1. Norms of cooperation among channels in general. (.77) 2. Trust as a society-wide phenomenon. (.82)

3. The intensity of trade associations related to channel management. (.76) 4. Moral obligation for providing quality products/services. (.80)

5. Expectations for high standards of codes of conduct. (.72)

Cultural-Cognitive Distance

CR = .83, AVE = .64 New scale

(response anchor same as for Regulatory Distance)

For each of the following items concerned with shared beliefs, conventions, taken-for-granted customs related to channel management, please indicate the magnitude of difference between your distributor country and your home country.

1. Professionals’ knowledge about channel management practice. (.85)

2. Companies’ ability to implement programs of efficient channel management. (.73) 3. Conventions of marketing channel operations. (.75)

4. Professionals’ knowledge of business environment related to channel management. (.80) 5. Professionals’ shared beliefs of transnational channel management. (.73)

Legitimacy, Ambiguity, and Control Mechanisms(2(25) = 86.15, p< .001; GFI = .92; CFI = .95; IFI = .93; RMSEA = .071)

Legitimacy Pressure

CR = .92, AVE = .71 (1 = “no need at all,” and 5 = “completely need”)

Please indicate the degree to which your firm needs to adopt business practices to conform to that of your distributor country in terms of the following aspects:

1. The desirability of business practice. (.82) 2. The properness of business practice. (.78) 3. The appropriateness of business practice. (.83)

Market Ambiguity

CR = .90, AVE = .78 (1 = “not difficult at all,” and 5 = “completely difficult”)

Please indicate the difficulty of processing information from the market in your distributor country due to its different institutional environments:

1. Market-related information analysis. (.87) 2. Market-related information interpretation. (.78) 3. Market-related information assessment. (.80)

Contract Customization

CR = .88, AVE = .72 Adapted from Cannon and Perreault (1999)

1. We have specific, well-detailed agreements with this distributor. (.87)

2. We have customized agreements that detail the obligations of both parties. (.88) 3. We have detailed contractual agreements specifically designed with this distributor. (.72)

Relational Governance

second-order indicator CR = .87, AVE = .69

2(30) = 60.57, p< .001; GFI = .94; CFI = .91; IFI = .92; RMSEA = .054

Information sharing: CR = .89, AVE = .71; adapted from Cannon and Perreault (1999) and Mohr and Sohi (1995).

1. Proprietary information is shared with each other. (.88) 2. We will both share relevant cost information. (.79)

3. We include each other in product development meetings. (.73) 4. We always share supply and demand forecasts. (.81)

Flexibility: CR = .87, AVE = .68; adapted from Heide and Miner (1992)

1. We are able to make adjustments in the ongoing relationship to cope with changing circumstances. (.77)

2. When some unexpected situation arises, we would rather work out a new deal than hold each other to the original terms. (.78)

3. Flexibility in response to requests for changes is a characteristic of this relationship. (.73)

Solidarity: CR = .81, AVE = .72; adapted from Cannon and Perreault (1999) and Anderson and Narus (1990)

1. No matter who is at fault, problems are joint responsibilities. (.89) 2. No party will take advantage of a strong bargaining position. (.83) 3. Both sides are willing to make cooperative changes. (.75) 4. We must work together to be successful. (.86)

5. We do not mind owing each other favors. (.72)

APPENDIX Continued

Channel Performance and Controls(2(34) = 48.91, p> .10; GFI = .97; CFI = .96; IFI = .98; RMSEA = .043)

Export Channel Performance

second-order indicator CR = .87, AVE = 0.68,

2(51) = 62.57, p< .001; GFI = .93; CFI = .95; IFI = .94; RMSEA = .053 Adapted from Bello and Gilliland (1997)

(1 = “extremely poor performance,” and 5 = “extremely good performance”)

Strategic performance:

Please indicate how effectively various aspects of the channel’s operational tasks were performed in terms of the following aspects:

1. Marketing strategy for foreign market. (.79) 2. Distribution strategy for foreign market. (.69) 3. Promotion strategy for foreign market. (.73) 4. Pricing strategy for foreign market. (.75)

Selling performance:

Please indicate how effectively various aspects of the channel’s sales tasks were performed in terms of the following aspects:

Economic performance:

Please indicate how effectively various aspects of the channel’s economic goals were performed in terms of the following aspects:

1. Economic goals for foreign market. (.84) 2. Sales goals for foreign market. (.90) 3. Growth goals for foreign market. (.75) 4. Profit goals for foreign market. (.70)

Asset Specificity

CR = .89, AVE = .71 Adapted from Heide and John (1992)

1. We have made significant investments in tooling and equipment dedicated to our rela-tionship with this distributor. (.76)

2. This distributor has some unusual technological norms and standards, which have required adaptation on our part. (.83)

3. Training and qualifying this distributor has involved substantial commitments of time and money. (.87)

4. Our production system has been tailed to meet the requirements of dealing with this distributor. (.71)

5. Our production system has been tailed to using the particular items bought from this distributor. (.78)

Environmental Volatility

CR = .77, AVE = .52 Adapted from Cannon and Perreault (1999)

Please indicate the significance of changes in the supply market with respect to the following factors:

1. Pricing. (.86)

2. Product features and specifications. (.81) 3. Vendor support services. (.75)

4. Technology. (.73)

Distributor Importance

CR = .77, AVE = .62 Adapted from Cannon and Perreault (1999)

Compared to other purchases your firm makes, the product from this distributor is A. unimportant 1 2 3 4 5 important (.80)

B. nonessential 1 2 3 4 5 essential (.89) C. low priority 1 2 3 4 5 high priority (.75)

Transaction Frequency How frequently has your company been placing orders with this distributor? (reverse coded) 1 = “More than once a day”; 2 = “Once a day”; 3 = “Once a week”; 4 = “2–3 times a month”; 5 = “Once a month”; 6 = “2–4 times a year”; 7 = “5–11times a year.”

History of Transaction How many years has your company been doing business with this distributor?

(1) 1~2; (2) 3~4; (3) 5~6; (4) 7~8; (5) 9~10; (6) 11~12; (7) 13~15; (8) 16~19; (9) 20 or more.

State-Owned Manufacturer 1 = State-owned; 0 = Non-state-owned.

Firm Size Number of employees of the firm: 1 = less than 50; 2 = 50–100; 3 = 101–200; 4 = 201–300; 5 = 301–500; 6 = 501–700; 7 = 701–1000; 8 = 1001–1500; 9 = 1501–2000; 10 = 2001 or more

Overall Model Fit 2(175) = 289.35, p< .001; GFI = .92; CFI = .93; IFI = .93; RMSEA = .056 APPENDIX

Continued

aStandardized factor loading.

bItems deleted from further analysis because of low factor loading.

Notes: CR = composite reliability, AVE = average variance extracted, GFI = goodness-of-fit index, CFI = comparative fit index, IFI = incremen-tal fit index, and RMSEA = root mean square error of approximation. Unless otherwise specified, all items were scored on five-point Lik-ert scales (1 = “strongly disagree,” and 5 = “strongly agree”).

Beckman, Christine, Pamela Haunschild, and Damon Phillips (2004), “Friends or Strangers? Firm-Specific Uncertainty, Mar-ket Uncertainty, and Network Partner Selection,” Organization Science, 15 (3), 259–75.

Bello, Daniel C. and David I. Gilliland (1997), “The Effect of Out-put Controls, Process Controls, and Flexibility on Export Channel Performance,” Journal of Marketing, 61 (January), 22–38.

Bickel, Robert (2007), Multilevel Analysis for Applied Research: It’s Just Regression!New York: The Guilford Press.

Busenitz, Lowell W., Carolina Gomez, and Jennifer W. Spencer (2000), “Country Institutional Profiles: Unlocking Entrepre-neurial Phenomena,” Academy of Management Journal, 43 (5), 994–1003.

Cannon, Joseph P. and William D. Perreault (1999), “Buyer-Seller Relationships in Business Markets,” Journal of Marketing Research, 36 (November), 439–60.

REFERENCES

Anderson, Erin (1985), “The Salesperson as Outside Agent or Employee: A Transaction Cost Analysis,” Marketing Science, 4 (3), 234–54.

Anderson, James C. and David W. Gerbing (1988), “Structural Equation Modeling in Practice: A Review and Recommended Two-Step Approach,” Psychological Bulletin, 103 (3), 411–23. ——— and James A. Narus (1990), “A Model of Distributor Firm and Manufacturer Firm Working Partnerships,” Journal of Marketing, 54 (January), 42–58.

Argyres, Nicholas and Kyle J. Mayer (2007), “Contracting Design as a Firm Capability: An Integration of Learning and Transac-tion Cost Perspective,” Academy of Management Review, 32 (4), 1060–1077.