Ž .

Labour Economics 7 2000 225–247

www.elsevier.nlrlocatereconbase

The effect of strike replacement legislation on

employment

John W. Budd

)Industrial Relations Center, UniÕersity of Minnesota, 3-300 Carlson School of Management, Minneapolis, MN 55455-0438 USA

Received 15 August 1996; accepted 23 July 1999

Abstract

Employers and employer groups often argue that restrictions on an employer’s ability to use replacement workers during a strike reduce employment. This study analyzes provincial employment-to-population ratios for 1966–1994 and unionized bargaining unit employment growth rates for 1966–1993 to test for an impact of provincial strike replacement policies in Canada. A strike replacement ban that restricts the use of both permanent and temporary replacements is found to have adverse employment consequences. The results for

reinstate-Ž .

ment rights provisions effectively banning permanent replacements and professional strikebreaker bans are mixed.q2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords: Strike replacement legislation; Employment; Canada

The impact of labor-related public policies on employment continues to be an important topic of debate within both academic and policy-making circles. The question of whether an increase in the minimum wage decreases employment dominates both policy debates and scholarly research on minimum wages. It is often argued that strong European job security regulations and dismissal laws reduce employment. Mandated employer-provided benefits are often thought to lower employment. Restrictions on employers’ abilities to use replacement em-ployees during strikes are argued to reduce employment. However, while there has

)E-mail: [email protected]

0927-5371r00r$ - see front matterq2000 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

Ž .

Ž

been research on the employment effects of minimum wages Card and Krueger,

. Ž .

1995 , dismissal laws Abraham and Houseman, 1994 and mandated benefits

ŽMitchell, 1990; Gruber, 1994 for example, the impact of strike replacement.

legislation on employment has not been analyzed.

Previous research has investigated the effect of various Canadian strike

replace-Ž

ment policies on strike incidence Gunderson et al., 1989; Budd, 1996; Cramton et

. Ž

al., 1999 , strike duration Gunderson and Melino, 1990; Budd, 1996; Cramton et

. Ž .

al., 1999 and real wages Budd, 1996; Cramton et al., 1999 . In related work,

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Gramm 1991 , Olson 1991 , Starkman 1993 , Gramm and Schnell 1994 and

Ž .

Schnell and Gramm 1994 study various aspects of the actual use of strike replacements. Nevertheless, to my knowledge, no study analyzes the impact of strike replacement policies on employment.

This study uses Canadian province-level aggregate data spanning 1966 to 1994 and disaggregated bargaining unit data spanning 1966 to 1993 to analyze the effect on employment of three types of strike replacement legislation. The most restric-tive type of legislation is a ban on strike replacements, both permanent and temporary. A second type of strike replacement law is one that grants striking workers the right to reinstatement at the conclusion of a strike with priority over temporary strike replacements. This type of statute effectively bans permanent, but not temporary, strike replacements. A third variety of legislation is a ban on the use of professional strikebreakers. As will be detailed below, there is considerable variation across time and across provinces between 1966 and 1994 in the presence of these types of strike replacement laws in Canada. Aggregate provincial data and disaggregated bargaining unit data are used to test for an impact of these laws on employment.

Various other studies have used a similar approach to analyze the effects of

Ž .

public policies. For example, using state-level panel data sets, Levine et al. 1996

Ž .

study Medicaid abortion funding restrictions, Lee et al. 1994 analyze tort reforms

Ž .

and Ellwood and Fine 1987 investigate right-to-work laws. Focusing on

employ-Ž . Ž .

ment, Lazear 1990 and Ruhm 1998 analyze the effect of government-mandated severance pay and parental leave, respectively, using country-level data. Most

Ž . Ž .

similar to the present research, Card 1992 and Neumark and Wascher 1992 ,

Ž .

using state-level data, and Schaafsma and Walsh 1983 , using provincial-level data, analyze the impact of minimum wage policies on employment. The present research applies this methodology to the question of strike replacement legislation’s effect on employment.

1. Strike replacement legislation

Ž .

In NLRBÕs. Mackay Radio and Telegraph, 304 U.S. 333, 346 1938 , the U.S.

( )

J.W. BuddrLabour Economics 7 2000 225–247 227

striking employees with others in an effort to carry on the business’’ thereby

Ž

allowing U.S. employers the use of permanent strike replacements Atleson, 1983; Sales, 1984; Weiler, 1984; Olson, 1991; Spector, 1992; LeRoy, 1993; Estreicher,

. Ž

1994 . This doctrine remains valid in 1999, albeit with some restrictions e.g.,

.

unfair labor practice strikes , since federal, state and local attempts to modify this doctrine have been unsuccessful.1 Thus, there is inadequate scope for empirically

testing the impact of strike replacement legislation in the United States because of the lack of variation in strike replacement policies.

In contrast, the provincial governments, not the federal government, have primary authority to regulate labor relations and collective bargaining in Canada. Consequently, while the foundations of labor relations are similar across provinces

Že.g., exclusive representation , there are many policy differences Adams, 1994 .. Ž .

Central to the present research is that a variety of provincial laws currently

Ž

regulate the use of strike replacements during legal strikes Spector, 1992; Adams,

. Ž

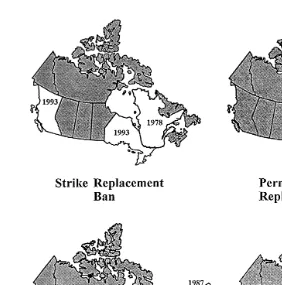

1994 . Fig. 1 provides an overview of these provincial statutes as of December

. 2

1994 .

The most restrictive strike replacement legislation is found in British Columbia

ŽLabour Relations Code, Section 68; effective January 1993 , Ontario. ŽThe

Labour Relations Act, Section 73; effective January 1993 and repealed November

. Ž .

1995 and Quebec Labour Code, Section 109.1; effective February 1978 . These statutes forbid employers from hiring someone to do bargaining unit work while the bargaining unit is engaged in a legal strike and restrict the use of existing

Ž

employees. Manitoba The Labour Relations Act, Section 11; effective January

. Ž Ž . .

1985 and Prince Edward Island Labour Act, Section 9 5 ; effective May 1987 both ban the use of permanent strike replacements. These two laws are weaker than the British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec laws in that the use of temporary replacements or existing employees is not restricted.

A third type of strike replacement law is the granting of reinstatement rights to striking employees. Between 1970 and 1993, Ontario gave striking employees the

Ž

right to return to their jobs within 6 months of the start of a strike The Labour

1

Between 1985 and 1995, the U.S. Congress considered, but did not pass, at least four proposals to limit the use of permanent strike replacements. State legislation restricting the use of replacements has been ruled unconstitutional. An obscure 1936 federal statute, the Byrnes Act, restricts the interstate

Ž .

transportation of strikebreakers. Various states also have anti-strikebreaking statutes Sales, 1984 , but they have often been ruled unconstitutional.

2

In the Canadian federal sector effective January 1, 1999, the revised Canada Labour Code provides reinstatement rights to striking workers and bans the use of replacements ‘‘for the demonstrated purpose of undermining a trade union’s representational capacity rather than the pursuit of legitimate bargaining objectives.’’ Prior to this legislative change, permanent strike replacements were restricted

Ž

in the federal sector by board and judicial precedent e.g., see Eastern ProÕincial AirwaysÕs. Canada

Ž Ž .

Labour Relations Board 84 C.L.L.C. 14,402 at 12,179 Fed. Ct. App. 1984 ruling that the use of .

Ž .

Fig. 1. Provincial strike replacement legislation in Canada December 1994 . Note: Shading denotes no legislation. Dates indicate effective year of legislation.

Ž . Ž . . Ž

Relations Act 1990 , Section 75 1 ; effective November 1970 . Quebec Labour

. Ž

Code, Section 110.1; effective February 1978 , Manitoba The Labour Relations

Ž . . Ž

Act, Section 12 1 ; effective January 1985 , Prince Edward Island Labour Act,

Ž . . Ž

Section 9 3 ; effective May 1987 , Alberta Labour Relations Code, Section

Ž . . Ž

88 1 ; effective November 1988 and Saskatchewan The Trade Union Act,

.

Section 46; effective October 1994 all provide reinstatement rights for strikers as well. These reinstatement policies effectively ban permanent strike replacements since employees are granted the right to return to their jobs with priority over replacement employees. The Saskatchewan policy is illustrative: if a strike or lock-out ends with no agreement on the reinstatement of striking employees, ‘‘an employer shall reinstate each striking or locked-out employee to the position that the employee held when the strike or lock-out began,’’ subject to sufficient work

Ž Ž ..

( )

J.W. BuddrLabour Economics 7 2000 225–247 229

perform the work of striking or locked-out employees during the strike or

Ž Ž ..

lock-out’’ Section 46 4 .

Three provinces have also restricted the use of professional strikebreakers:

Ž Ž .Ž .

British Columbia Labour Relations Code, Section 3. 3 d ; effective November

. Ž Ž .

1973 , Manitoba The Labour Relations Act, Section 14 2 ; effective January

. Ž Ž . Ž .

1985 and Ontario The Labour Relations Act 1990 , Section 73 1 ; effective June

.

1983 . In Manitoba and Ontario, a professional strikebreaker is defined to be ‘‘a

w

person who is not involved in a dispute whose primary object in the board’s

x

opinion , is to interfere with, obstruct, prevent, restrain or disrupt a legal strike.’’ British Columbia’s definition is similar.

Fig. 1 summarizes the incidence of the four types of strike replacement laws in

Ž .

Canada as of December 1994 and underscores the variation in these laws across both provinces and time. If this variation is exogenous, it provides a ‘‘natural experiment’’ for testing the effects of these labor policies. At the same time, however, it is apparent that all of the provinces that banned permanent strike replacements also enacted reinstatement rights provisions. Given this overlap and the conceptual similarity between permanent strike replacement bans and reinstate-ment rights, the empirical analysis will not include a separate variable for permanent strike replacement legislation.

2. Strike replacement legislation: the employment debate

In U.S. and Canadian policy debates over restrictions on employers’ abilities to use strike replacements, employers and employer groups fervently argue that such restrictions would decrease employment. For example, in response to the proposed labor law changes that resulted in the 1993 Ontario strike replacement ban, the

Ž .

Council of Ontario Construction Associations COCA argued that ‘‘proposed labour relations reforms will mean lost jobs, lost investment in the province and

Ž

further erosion of Ontario’s international competitiveness’’ Council of Ontario

.

Construction Associations, 1992a, p. 4 . An Ernst and Young report commissioned by COCA surveyed employers’ beliefs about the likely impact of the proposed Ontario labor law changes and concluded that the proposed legislation would

Ž

result in the loss of 295,000 jobs in Ontario Council of Ontario Construction

.

Associations, 1992b, p. 10 . In announcing the November 1995 repeal of the Ontario strike replacement ban, the Ontario Labour Minister stated that ‘‘by restoring balance to our labour laws, we have taken a major step to attract new

Ž .

investment and create jobs’’ Canada NewsWire, 1995 . In response to a Canadian federal proposal to ban strike replacements, the Business Council of British

Ž .

Ž

Canadian industry.’’ Similar arguments are made in the United States see U.S.

. 3

Congress, 1989, 1991, 1993a, 1995 .

The primary thinking that underlies these arguments is a simple bargaining

Ž .

power model Chamberlain and Kuhn, 1965 . In this framework, restrictions on an employer’s use of strike replacements increase the costs of strikes to employers by making it more difficult to continue production during a work stoppage. At the same time, strike replacement bans decrease the costs of strikes to unions and employees by reducing the risk of job loss. Thus, strike replacement legislation theoretically increases labor’s relative bargaining power which yields collective bargaining settlements with higher labor costs than in provinces without strike

Ž .

replacement restrictions Fares and Robert, 1996; Cramton et al., 1999 . With

`

higher labor costs, employment falls.4

A second line of reasoning articulated is that restrictions on the use on strike replacements may cause production to shift to other locations during a strike. If production is shifted to a locale without strike replacement restrictions and this shift is relatively permanent, then employment will be reduced in jurisdictions with strike replacement legislation. Finally, to the extent that strike replacement prohibitions are perceived to be linked with increased strike activity, employers and potential employers may feel that the industrial relations climate is unattrac-tive and locate production elsewhere.

On the other hand, proponents of strike replacement restrictions claim that these policies can increase employment. In particular, the government of Ontario articulated cooperative labor-management relations and effective employee partici-pation as rationales for the labor law reforms that included the 1993 strike

Ž .

replacement ban Ontario Ministry of Labour, 1991 . Strike replacement restric-tions are argued to reduce antagonism in the collective bargaining relarestric-tionship which yields a more productive workplace and employment is not adversely affected. For the permanent replacement ban, it is possible that employment in some circumstances will increase in that once a strike concludes, the firm must

Ž

re-employ the striking workers but may also wish to retain due to positive search

.

and hiring costs good employees it uncovered during the strike. This effect is limited to those situations in which temporary replacements are actually utilized and is therefore unlikely to have discernable effects beyond specific examples.

Ž .

Finally, Budd and Wang forthcoming develop a sequential model in which wage bargaining follows a fixed capital investment decision. Unlike the other

Ž

models which assume that capital is constant e.g., Fares and Robert, 1996;

`

. Ž .

Cramton et al., 1999 , in the model of Budd and Wang forthcoming , strike

3

Similar arguments are also articulated in response to other proposed labor and employment law

Ž

changes, for example minimum wage increases or workplace safety and health regulatory changes e.g.,

.

U.S. Congress, 1993b . 4

This model also implies that strike replacement restrictions increase wages, but this prediction has

Ž .

( )

J.W. BuddrLabour Economics 7 2000 225–247 231

replacement restrictions potentially reduce capital investment so that the wage effect is ambiguous. Extending this reasoning, strike replacement legislation has an ambiguous predicted effect on employment depending on the legislation’s effect on capital and wages and the relationship between capital, wages and employment.

Thus, two concluding points are in order. One, nearly all of the claims about replacement policies and employment pertain to the threat of using replacements, not the actual usage. Two, there is considerable debate over whether strike replacement legislation affects employment. What happens in practice is an empirical question.

3. Provincial aggregate employment data

The aggregate data used in this study were constructed primarily from monthly and annual Statistics Canada sources. Appendix A contains details on sources and variable construction. The resulting data set contains 3480 observations consisting of a monthly time series of data covering January 1966 to December 1994 for each

Ž

of the 10 provinces. Following the minimum wage literature Card, 1992;

Neu-.

mark and Wascher, 1992 , the dependent variable is the provincial employment-to-population ratio which is the ratio of a province’s number of people employed

Žaged 15 and older to the province’s population aged 15 and older . The average. Ž .

employment-to-population ratio for 1966–1994, weighted by provincial popula-tion, is 57.921.

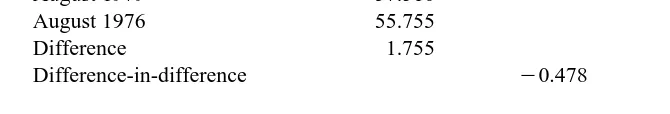

As described above, Quebec enacted legislation banning the use of strike replacements in February 1978 while Ontario and British Columbia enacted similar laws in January 1993. To consider what happened to the employment-to-population ratio, Table 1 illustrates that 18 months before the Quebec law became effective, Quebec’s employment-to-population ratio was 55.755. Eighteen months after the law, Quebec’s employment-to-population ratio had increased by 1.755 to 57.510. To assess the impact of the law, however, one needs to know the counterfactual of what would have happened in the absence of such a law. To this end, Table 1 illustrates that in this same period, the average employment-to-popu-lation ratio, weighted by provincial employment, in the other nine provinces increased by 2.233. If the only determinant of employment-to-population ratios that differs across the 10 provinces is a change in provincial strike replacement legislation, then the employment-to-population ratio change of the other nine provinces can be used to infer what Quebec’s change would have been without a new strike replacement law. This yields the difference-in-difference estimate of the

effect of Quebec’s strike replacement ban of 1.755–2.233s y0.478, or a 0.478

Table 1

Difference-in-difference estimates of the effect of strike replacement bans on the

employment-to-popu-Ž .

lation ratio. Source: Statistics Canada various issues The Labour Force, Ottawa, Ontario, Catalogue CS71-001

a Average provincial employment-to-population ratio

Ž .1 Ž .2

Quebec’s February 1978 strike replacement ban

Quebec All others

August 1979 57.510 63.140

August 1976 55.755 60.907

Difference 1.755 2.233

Difference-in-difference y0.478

Ontario and British Columbia’s January 1993 Strike Replacement Ban Ontario and British Columbia All others

July 1994 61.340 59.477

July 1991 63.067 60.357

Difference y1.727 y0.880

Difference-in-difference y0.847

a

Weighted by provincial population.

British Columbia strike replacement bans. The result is a 0.847 reduction in the employment-to-population ratio.

The validity of these difference-in-difference estimates, however, relies on the assumption that all of the factors affecting provincial employment except strike replacement legislation are changing in the same way across provinces. Thus, differencing the treatment and control group employment-to-population ratio changes removes the impact of the other determinants. If this assumption is not satisfied, the difference-in-difference estimate will be confounded by other factors. Consequently, a multivariate regression estimation strategy is undertaken and the results reported in Table 2.

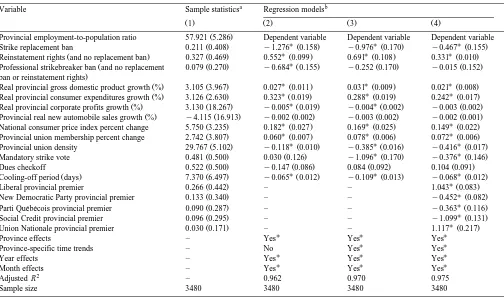

In an attempt to control for observable differences in provincial employment, a variety of additional variables were merged to the provincial employment-to-popu-lation ratio data. These variables are listed, with their sample means and standard deviations, in Table 2 and described in more detail in Appendix A. These variables

Notes to Table 2:

a Ž .

Sample means sample standard deviations in parentheses weighted by provincial population. b

Dependent variable: provincial employment-to-population ratio. Each model also contains an intercept and is weighted by provincial population. The standard errors in columns 2–4 are robust to arbitrary forms of heteroskedasticity.

U

Ž .

()

Regression analysis of the provincial employment-to-population ratio, 1966–1994 standard errors in parentheses . Source: see text

a b

Variable Sample statistics Regression models

Ž .1 Ž .2 Ž .3 Ž .4

Ž .

Provincial employment-to-population ratio 57.921 5.286 Dependent variable Dependent variable Dependent variable

U U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Strike replacement ban 0.211 0.408 y1.276 0.158 y0.976 0.170 y0.467 0.155

U U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Reinstatement rights and no replacement ban 0.327 0.469 0.552 0.099 0.691 0.108 0.331 0.010 U

Ž Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Professional strikebreaker ban and no replacement 0.079 0.270 y0.684 0.155 y0.252 0.170 y0.015 0.152

.

ban or reinstatement rights

U U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Real provincial gross domestic product growth % 3.105 3.967 0.027 0.011 0.031 0.009 0.021 0.008

U U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Real provincial consumer expenditures growth % 3.126 2.630 0.323 0.019 0.288 0.019 0.242 0.017

U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Real provincial corporate profits growth % 3.130 18.267 y0.005 0.019 y0.004 0.002 y0.003 0.002

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Provincial real new automobile sales growth % y4.115 16.913 y0.002 0.002 y0.003 0.002 y0.002 0.001

Ž . UŽ . UŽ . UŽ .

National consumer price index percent change 5.750 3.235 0.182 0.027 0.169 0.025 0.149 0.022

U U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Provincial union membership percent change 2.742 3.807 0.060 0.007 0.078 0.006 0.072 0.006

U U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Provincial union density 29.767 5.102 y0.118 0.010 y0.385 0.016 y0.416 0.017

U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Mandatory strike vote 0.481 0.500 0.030 0.126 y1.096 0.170 y0.376 0.146

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Dues checkoff 0.522 0.500 y0.147 0.086 0.084 0.092 0.104 0.091

U U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Cooling-off period days 7.370 6.497 y0.065 0.012 y0.109 0.013 y0.068 0.012

U

Ž . Ž .

Liberal provincial premier 0.266 0.442 – – 1.043 0.083

U

Ž . Ž .

New Democratic Party provincial premier 0.133 0.340 – – y0.452 0.082

U

Ž . Ž .

Parti Quebecois provincial premier´ ´ 0.090 0.287 – – y0.363 0.116

U

Ž . Ž .

Social Credit provincial premier 0.096 0.295 – – y1.099 0.131

U

Ž . Ž .

Union Nationale provincial premier 0.030 0.171 – – 1.117 0.217

U U U

Province effects – Yes Yes Yes

Province-specific time trends – No YesU

YesU

U U U

Year effects – Yes Yes Yes

U U U

Month effects – Yes Yes Yes

2

Adjusted R – 0.962 0.970 0.975

are intended to capture the economic, political and labor policy climate of each province for a given point in time and were selected based on the previous literature, ex ante expectations and data availability. As indicators for the strength of the provincial economy, the data set includes the real growth rates of provincial

Ž .

gross domestic product GDP , consumer expenditures, corporate profits and the dollar value of new automobile sales. Other explanatory variables included to represent economic and labor market conditions are the national inflation rate, the percent change in provincial union membership and the provincial union density rate.5As proxies for the political climate, dichotomous variables were constructed

Ž

indicating the ruling party in the provincial legislature Conservative is the omitted

.

category . Since other public policies are sometimes enacted at the same time as strike replacement legislation, three variables indicating the presence of a manda-tory strike vote, dues checkoff and required cooling-off period are also included. Of particular interest is the impact of strike replacement legislation. Thus, three indicator variables were created to indicate the strongest statutory strike

replace-Ž .

ment policy in effect in each month in each province see table in Appendix A .

Ž .

The first dummy variable indicates if there was a strong ban on using strike replacements. This variable includes the restrictive bans of British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec, but not the less restrictive bans on permanent strike replace-ments only. The second variable equals one if reinstatement rights for strikers was

Ž .

the most restrictive policy in effect i.e., temporary replacements are not restricted . In this coding scheme, permanent strike replacement bans are considered reinstate-ment rights, not general replacereinstate-ment bans. The third variable indicates province-months in which professional strikebreakers are banned and the other two types of strike replacement legislation are not present. Each of these variables is con-structed from the provincial statutes using the effective dates listed above. As illustrated in column 1 of Table 2, 21.1% of the weighted monthly observations

Ž

include a strike replacement prohibition, 32.7% include reinstatement rights and

.

no ban on temporary replacements , and 7.9% are covered by a professional strikebreaker prohibition only.

Since the general replacement bans of Quebec, Ontario and British Columbia clearly place the greatest restrictions on employers’ abilities to use replacement workers, this variable is predicted to have the strongest effect on employment. A professional strikebreaker ban is a weak, potentially obsolete, restriction and is predicted to have minimal employment consequences. Conceptually, the effect of the reinstatement rights variable on employment is somewhere between the other two policies. However, in practice there has been some confusion about provincial

5

( )

J.W. BuddrLabour Economics 7 2000 225–247 235 Ž

permanent strike replacement policies. For example, Spriggs as quoted in U.S.

.

Congress, 1991, p. 324 , claims that ‘‘all Canadian provinces, through legislation or jurisprudence, require the reinstatement of striking employees to their jobs at

Ž .

the conclusion of a work stoppage.’’ Martinello and Meng 1992, p. 178 claim that ‘‘all jurisdictions prohibit the hiring of permanent replacements for striking workers.’’ These claims are incorrect, but they may cloud the interpretation of the results if such confusion is widespread.6

Column 2 of Table 2 presents the results of regressing the provincial employ-ment-to-population ratio on the independent variables described above, except the political variables, plus year effects, month effects and province effects weighted

by provincial employment.7 The model explains more than 96% of the variance

in the monthly employment-to-population ratio. As one would probably expect, real GDP growth and real consumer expenditures growth are both positively related to employment.

The coefficients of interest, however, are the first three in column 2. The presence of a strike replacement ban is estimated to reduce the employment-to-population ratio by 1.276, on average ceteris paribus. Moreover, this coefficient is statistically significant at all conventional levels of significance with an absolute

Ž

t-statistic greater than 8. In December 1992, the population of Ontario aged 15

.

and older was 7,926,000 so each one point reduction in the employment-to-popu-lation ratio translates to a reduction in employment of approximately 80,000 jobs. While the 295,000 estimate of Ontario jobs lost produced by Ernst and Young

ŽCouncil of Ontario Construction Associations, 1992b seems exaggerated, the.

estimate in column 2 implies significant job loss from enacting a replacement ban. The professional strikebreaker estimate is also statistically significant and

Ž .

negative, albeit not as large in absolute value as the replacement ban coefficient which is what one would expect since a professional strikebreaker ban is not as restrictive. More puzzling is the reinstatement rights coefficient which is statisti-cally significant and positive.

To investigate the robustness of these results, columns 3 and 4 of Table 2 report the results of two alternative specifications. First, while the regression in column 2 controls for province-specific and year-specific fixed effects, ideally one would like to be able to control for province-specific effects that vary over time. For example, while the year effects control for aggregate demographic changes, they do not account for province-specific demographic changes. However, strike

re-6 Ž .

Provincial labor law specifies that striking workers remain employees legally while engaged in a legal strike, but only the federal jurisdiction has been unambiguous in ruling that this legal status renders permanent replacements illegal.

7

The unweighted regression results are very similar. For example, the replacement ban coefficient

Žstandard error in the unweighted regression analogous to the weighted regression reported in column.

Ž .

placement legislation coefficients cannot be estimated in a model with province

Ž .

and year effect interactions. Thus, following Levine et al. 1996 , the regression in column 3 adds province-specific time trends.

Second, column 4 reports the results of adding a set of five indicator variables

Ž

denoting the ruling party of the provincial government Conservative is the

.

omitted category to the regression model. The rationale for the inclusion of these

Ž

regressors is that if political parties affect provincial employment e.g., via

.

regulation or taxes and if strike replacement legislation is correlated with various political parties being in control, then the strike replacement coefficients in columns 2 and 3 suffer from omitted variable bias. In fact, the three strike

replacement bans were enacted by New Democratic Party or Parti Quebecois

´ ´

governments and the estimates in column 4 imply that political parties are correlated with provincial employment.

Focusing on the column 4 results, the strike replacement ban coefficient is

Ž .

significantly smaller in absolute value relative to columns 2 and 3, but is statistically significant at conventional levels of significance with a p-value of 0.003. The professional strikebreaker coefficient is very small and imprecisely estimated. Since the strike replacement bans are very restrictive whereas the professional strikebreaker ban is not, these results are consistent with the nature of the laws. In contrast, the reinstatement rights point estimate is positive and statistically significant — a surprising result which will be addressed after Table 3.

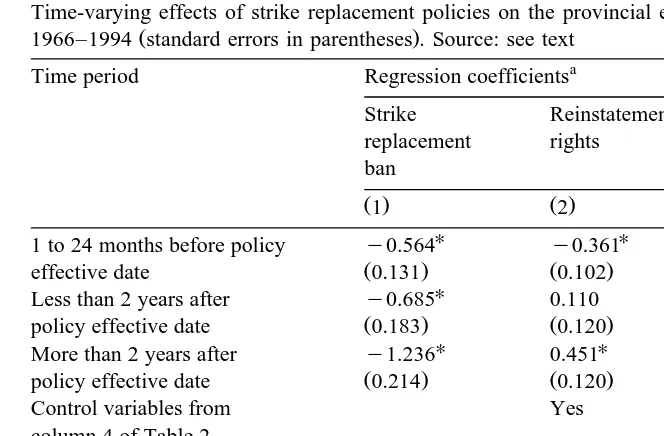

For this natural experiment methodology to yield reliable inferences, however, the policy changes need to be exogenous. If, for example, violent strikes caused a provincial government to restrict the use of replacements and caused business to reduce investment and employment, then the legislation is not exogenous. Lacking suitable instruments, Table 3 reports the results of regressing the employment-to-population ratio on the control variables from Table 2 plus three dummy variables for each strike replacement policy. The first dummy variable for each policy captures what happened to the employment-to-population ratio in the 2-year period prior to the legislation. The other two dummy variables divide each policy into two periods: the first 2 years and after the first 2 years.

The first row of Table 3 illustrates that the provincial employment-to-popula-tion ratio during the 2 years leading up to a new strike replacement policy is significantly different than what is predicted to occur with no policy changes, which suggests that policy changes may not be exogenous. However, the negative coefficients in the first row imply that the estimates in Table 2 are biased towards zero, not away from zero.

( )

J.W. BuddrLabour Economics 7 2000 225–247 237 Table 3

Time-varying effects of strike replacement policies on the provincial employment-to-population ratio,

Ž .

1966–1994 standard errors in parentheses . Source: see text a

1 to 24 months before policy y0.564 y0.361 y1.110

Ž . Ž . Ž .

effective date 0.131 0.102 0.107

U U

Less than 2 years after y0.685 0.110 y1.142

Ž . Ž . Ž .

policy effective date 0.183 0.120 0.254

U U

More than 2 years after y1.236 0.451 0.482

Ž . Ž . Ž .

policy effective date 0.214 0.120 0.207

Control variables from Yes

column 4 of Table 2

U

Dependent variable: provincial employment-to-population ratio. The standard errors are robust to arbitrary forms of heteroskedasticity.

U

Ž .

Statistically significant at the 0.05 level two-tailed test .

predicted that its effect would be the strongest. The results are consistent with this prediction, but the results for the other two policies are more puzzling.

Taken literally, the reinstatement rights estimates imply that banning permanent strike replacements will not have adverse employment consequences — and may even increase employment. However, this effect is not very robust to alternative specifications. For example, in regressions similar to those reported in Table 2, restricting the sample period to 1966 to 1980, 1985 or 1992 yields a significantly negative strike replacement ban as in Table 2, but negative and imprecisely estimated coefficients for the reinstatement rights variable. Excluding British Columbia or allowing the province effects to be different before and after 1980 also have the same effect. Thus, it appears that the reinstatement rights estimates are being driven by very narrow geographical and time factors.

Moreover, as noted above there appears to be some confusion as to the extent that permanent strike replacements are legal in Canada.8 Lastly, as illustrated in

8

()

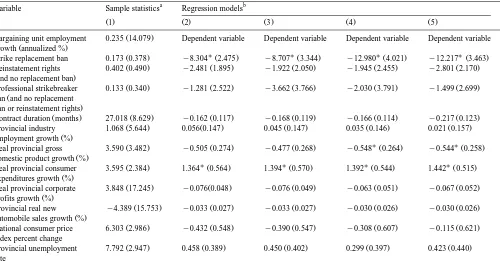

Regression analysis of private sector unionized bargaining unit employment growth, 1966–1993 standard errors in parentheses . Source: see text

a b

Variable Sample statistics Regression models

Ž .1 Ž .2 Ž .3 Ž .4 Ž .5

Ž .

Bargaining unit employment 0.235 14.079 Dependent variable Dependent variable Dependent variable Dependent variable

Ž .

growth annualized %

U U U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Strike replacement ban 0.173 0.378 y8.304 2.475 y8.707 3.344 y12.980 4.021 y12.217 3.463

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Reinstatement rights 0.402 0.490 y2.481 1.895 y1.922 2.050 y1.945 2.455 y2.801 2.170

Žand no replacement ban.

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Professional strikebreaker 0.133 0.340 y1.281 2.522 y3.662 3.766 y2.030 3.791 y1.499 2.699

Ž

ban and no replacement

.

ban or reinstatement rights

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Contract duration months 27.018 8.629 y0.162 0.117 y0.168 0.119 y0.166 0.114 y0.217 0.123

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Provincial industry 1.068 5.644 0.056 0.147 0.045 0.147 0.035 0.146 0.021 0.157

Ž .

employment growth %

U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Real provincial gross 3.590 3.482 y0.505 0.274 y0.477 0.268 y0.548 0.264 y0.544 0.258

Ž .

domestic product growth %

U U U U

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Real provincial consumer 3.595 2.384 1.364 0.564 1.394 0.570 1.392 0.544 1.442 0.515

Ž .

expenditures growth %

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Real provincial corporate 3.848 17.245 y0.076 0.048 y0.076 0.049 y0.063 0.051 y0.067 0.052

Ž .

profits growth %

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Provincial real new y4.389 15.753 y0.033 0.027 y0.033 0.027 y0.030 0.026 y0.030 0.026

Ž .

automobile sales growth %

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

National consumer price 6.303 2.986 y0.432 0.548 y0.390 0.547 y0.308 0.607 y0.115 0.621

index percent change

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Provincial unemployment 7.792 2.947 0.458 0.389 0.450 0.402 0.299 0.397 0.423 0.440

()

Mandatory strike vote 0.409 0.492 7.797 2.052 7.214 2.842 5.657 2.747 7.224 2.527

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Dues checkoff 0.520 0.500 0.551 1.405 0.926 1.786 1.016 1.802 1.034 1.697

Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž . Ž .

Cooling-off period days 7.448 6.474 0.461 0.277 0.489 0.301 0.422 0.298 0.510 0.281

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Liberal provincial premier 0.248 0.432 – – y1.998 2.173 y1.580 1.860

U

Ž . Ž . Ž .

New Democratic Party 0.079 0.269 – – y1.859 2.010 y3.164 1.600

provincial premier

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Parti Quebecois provincial´ ´ 0.112 0.315 – – 3.775 4.763 3.905 4.952

premier

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Social Credit provincial 0.155 0.362 – – y1.792 2.173 y2.672 2.984

premier

Ž . Ž . Ž .

Union Nationale provincial 0.035 0.183 – – 1.274 4.010 y0.201 3.511

premier

Province effects – Yes Yes Yes No

Province-specific time trends – No Yes Yes No

U U U U

Year effects – Yes Yes Yes Yes

Industry effects – YesU

YesU

YesU

No

Bargaining unit effects – No No No Yes

2

Adjusted R – 0.084 0.083 0.085 0.017

Sample size 3629 3629 3629 3629 3629

a Ž .

Sample means sample standard deviations in parentheses weighted by bargaining unit employment. b

Dependent variable: bargaining unit employment annualized percent change over the life of the contract. Each model also contains an intercept and is weighted by bargaining unit employment. The standard errors in columns 2–5 are robust to arbitrary forms of heteroskedasticity.

U

Ž .

the table in Appendix A, the professional strikebreaker ban variable is constructed from only a single province. Therefore, it is prudent to refrain from strong conclusions regarding these two variables until other data sources are used.

4. Disaggregated unionized employment data

The disaggregated data for this study consist of 3629 Canadian private sector collective bargaining agreements. Human Resources Development Canada main-tains a major wage settlements database of collective agreements covering 500 or more workers. This database includes bargaining unit employment as one of the

pieces of information collected.9 By matching successive contracts, the

annual-ized percent change in bargaining unit employment over the life of the collective bargaining agreement can be calculated. After merging control variables similar to those used in the aggregate analysis and deleting observations with missing data,

Ž

3629 private sector collective bargaining agreements remain see Appendix A for

.

details . The resulting panel data set spans 1966 to 1993. The data contain 482 union-establishment bargaining pairs each of which have at least four contracts in the data set.

The sample means and standard deviations of the variables used in the disaggregated employment analysis are presented in column 1 of Table 4. Most of the variables are the same as in the aggregate analysis and only the differences will be highlighted here. Since all of the observations are union contracts, the two union membership variables are dropped from the analysis. As additional indica-tors of the economic environment, the provincial 1-digit industry employment growth rate and the provincial unemployment rate are used. Finally, a set of industry effects is added to the regressions.10

The results of regressing the bargaining unit annualized employment growth rate on the independent variables, weighted by bargaining unit employment, are reported in column 2 of Table 4.11 In sharp contrast to the

employment-to-popula-9

This Human Resources Development Canada database also serves as the basis for the data sets

Ž . Ž . Ž .

used by Gunderson and Melino 1990 , Gunderson et al. 1989 , Budd 1996 and Cramton et al.

Ž1999 to analyze the effect of strike replacement and labor policy legislation on strike activity and.

wages. 10

As in the aggregate regressions, the bargaining unit regressions do not include wage or earnings variables due to potential endogeneity problems. However, including the annualized percent change over the life of the contract in the real base contract wage, real provincial average weekly earnings and its growth rate, various lagged values of the variables or instrumenting for the base wage growth rate using lagged values does not alter the results.

11

The unweighted regression results are similar with the primary difference being that the

replace-Ž .

( )

J.W. BuddrLabour Economics 7 2000 225–247 241

tion ratio models, the disaggregated employment growth rate models have low predictive ability. To wit, the adjusted R2 from the regression reported in column

2 is only 0.084. The R2 values are, however, very similar to those reported in

Ž . Ž .

Abowd and Lemieux 1991, Table 13.4 and Long 1993, Tables 3 and 4 in their analyses of unionized employment growth in Canada.

Notwithstanding the poor overall regression model performance, the estimate in column 2 of the strike replacement ban coefficient is negative and statistically

Ž .

significant at the 1% level p-values0.001 . The reinstatement rights and

professional strikebreaker ban coefficients are negative, but both are imprecisely estimated. The hypothesis that the true coefficient for each of these two strike replacement policies is zero cannot be rejected at conventional levels of signifi-cance.

To investigate the sensitivity of these results to alternative specifications, columns 3–5 report the regression results for three different specifications. Col-umn 3 adds province-specific time trends as in colCol-umn 3 of Table 2. ColCol-umn 4 adds indicator variables for the provincial government ruling party as was done in column 4 of Table 2. To control for unobservable time-constant bargaining unit heterogeneity, column 5 adds a set of bargaining unit fixed effects.

As was the case for the aggregate analysis, the pattern of results for the strike replacement legislation coefficients across these various specifications is fairly

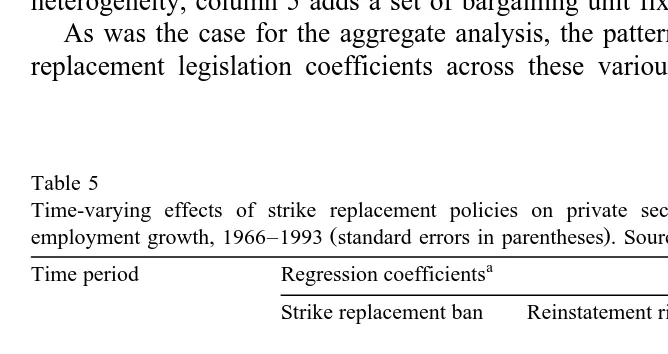

Table 5

Time-varying effects of strike replacement policies on private sector unionized bargaining unit

Ž .

employment growth, 1966–1993 standard errors in parentheses . Source: see text a

Time period Regression coefficients

Strike replacement ban Reinstatement rights Professional strikebreaker ban

Ž .1 Ž .2 Ž .3

Ž . Ž . Ž .

1 to 24 months before 1.160 3.672 7.873 4.348 3.678 2.840

policy effective date

UŽ . Ž . Ž .

Less than 2 years after y12.967 5.878 0.751 2.170 y2.919 5.778 policy effective date

UŽ . Ž . Ž .

More than 2 years after y8.739 3.833 0.874 2.353 0.866 2.866 policy effective date

Control variables from Yes

column 5 of Table 4

U

Dependent variable: bargaining unit employment annualized percent change over the life of the contract. The standard errors are robust to arbitrary forms of heteroskedasticity.

U

Ž .

stable. The reinstatement rights and professional strikebreaker ban coefficients remain negative, imprecisely estimated and statistically insignificant. The esti-mated strike replacement ban coefficient is consistently negative and statistically

Ž .

significant with the largest p-values equalling 0.009 column 3 . Moreover, the point estimates for the strike replacement ban are not modest. For example, relative to the mean growth rate of 0.235% per year in the full sample, the estimate in column 2 predicts that bargaining units in a province with a strike replacement ban will be shrinking by 8.304% per year. The point estimates in the

Ž .

other specifications are even larger in absolute value .

Table 5 presents the results of allowing the strike replacement policy effects to vary over time. In contrast to the aggregate case, one cannot reject the null hypothesis that unionized employment growth rates deviate from the no-policy mean during the 2 years leading up to a policy change, suggesting that endogenous policy changes might not be affecting the results. In terms of short run vs. long run policy implications, the estimates for reinstatement rights and professional strike-breaker bans are statistically insignificant in both time periods. The strike replace-ment ban effect gets smaller 2 years after the policy effective date, but is still quite large. Note that because the Ontario and British Columbia bans were enacted towards the end of the sample time period, the long run strike replacement variable relies solely on Quebec’s experience.

5. Conclusion

This study analyzes the effect of Canadian provincial strike replacement legislation on employment using province-level aggregate data for 1966–1994 and private sector, bargaining unit-level disaggregated data for 1966–1993. Three types of strike replacement statutes are analyzed: strike replacement bans that prohibit both permanent and temporary replacements, reinstatement rights for

Ž .

strikers effectively banning permanent replacements , and restrictions on the use of professional strikebreakers.

( )

J.W. BuddrLabour Economics 7 2000 225–247 243

relies on the experience of a single province. Given the problems with these two variables, definitive conclusions will have to await further research.

For the more restrictive strike replacement bans of Quebec, Ontario and British Columbia, however, the empirical results are consistent in both the aggregate and disaggregated analyses. A strike replacement ban is associated with a lower provincial employment-to-population ratio, on average, and a drastically lower bargaining unit employment growth rate. Both estimated relationships are statisti-cally significant at conventional levels of significance controlling for other poten-tial determinants of employment. Moreover, the negative impact of the replace-ment ban on employreplace-ment is considerably larger for large, unionized bargaining units than for the provincial aggregate. Thus, using aggregate and disaggregated data, legislative restrictions on an employer’s ability to utilize strike replacements are found to have adverse employment consequences, but only for the strongest legislation that restricts the use of both temporary and permanent replacements.

In closing it is important to note that strike replacement legislation is often enacted as part of a larger labor relations reform package and enacted by governments that are likely to undertake other initiatives perceived as unfavorable by business. As a proxy for the latter problem, the empirical analysis controls for the political party of the provincial government. Some controls are also included in the regressions for other labor relations changes enacted at the same time as strike replacement policies, but it is difficult to find sufficient independent variation to isolate each piece of a package. Therefore, the estimated negative employment

Ž

effects for the strike replacement ban might best be thought of as upper bounds in

.

absolute value on the true magnitude of a strike replacement ban’s impact. Nevertheless, a strike replacement ban is arguably the most restrictive piece of any package so it is likely that a sizable portion of the estimate is due to this policy change.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to Christina Brademas, Michael McDermott, David Zimmerman, and seminar participants at the University of Minnesota, Colgate University, and the Fifth Bargaining Group Conference for their assistance in the preparation of this paper and to the Carlson School of Management’s McKnight - Business and Economics Research Grants Program for financial support.

Appendix A

The aggregate employment-to-population ratios were calculated from employ-ment and population data collected by Statistics Canada. Data up to 1991 were

Ž .

Ž .

CD-ROM matrices 2078–2096 and updated using various issues of The Labour

Ž .

Force Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue CS71-001 . The aggregate product

and labor market indicators were also constructed from data retrieved from

Ž .

CANSIM: the Canadian CPI series P48400 , provincial average weekly earnings

ŽAWE. Žmatrices 1433–1493 and 8007–8607 , provincial gross domestic product.

ŽGDP. Žmatrices 2610–2619 and 6949 , provincial consumer expenditures.

Žmatrices 2622–2631 and 6950 , provincial corporate profits before taxes matrices. Ž

. Ž .

2610–2619 and 6949 and provincial new car sales matrix 0064 . More recent data were collected from various issues of Employment, Earnings and Hours

ŽOttawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue CS72-002 , Canadian Economic Obser. Õer

ŽOttawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue CS11-010 and Pro. Õincial Economic

Ac-Ž .

counts Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue CS13-213 . Provincial union

mem-bership data was collected from the annual reports under the Corporations and

Ž . Ž

Labour Unions Returns Act CALURA Ottawa: Statistics Canada, Catalogue

.

CS71-202 . The provincial election data is from the Canadian Parliamentary

Ž .

Guide Toronto, Ontario: Globe and Mail Publishing . The strike replacement

policy variables were constructed using the text of each bill amending the existing provincial statute and its effective date as reported in each province’s legislative reports.

Strike replacement legislation variable codings, 1964–1994

Strike replacement ban Quebec February 1978 to

December 1994

British Columbia January 1993 to

December 1994

Ontario January 1993 to

December 1994

Reinstatement rights Ontario November 1970 to

Žand no replacement ban. December 1992

Manitoba January 1985 to

December 1994

Prince Edward Island May 1987 to

December 1994

Alberta December 1988 to

December 1994

Saskatchewan November 1994 to

December 1994

Professional strikebreaker British Columbia January 1974 to

Ž

ban and no replacement December 1992

.

ban or reinstatement rights

( )

J.W. BuddrLabour Economics 7 2000 225–247 245

average of the current and previous years’ values were created for each month. Whenever a series changed scope or method, e.g., Statistics Canada revised its

Ž .

establishment survey used to compute AWE data in April 1983, the series was spliced together using overlapping observations. The nominal series were con-verted to real series using the Canadian CPI.

The collective bargaining agreement data are collected by Human Resources

Ž .

Development Canada formerly Labour Canada and were gathered from three Human Resources Development Canada sources for use in this paper: two releases

Ž

of the Major Wage Settlements Calculated Master Files on magnetic tape one

.

covering 1964–1985; the other 1978–1993 and recent issues of CollectiÕe

Ž

Bargaining ReÕiew Ottawa: Human Resources Development Canada, Catalogue

. Ž .

L12-13 covering 1993–1995 . These sources contain information on the identity

of the company and the union, bargaining unit size, industry, province, settlement and effective dates, negotiated contract duration and the wage settlement. All three sources were matched based on the available information and duplicates deleted. Contracts covering bargaining units in more than one province were also deleted because it is sometimes difficult to determine which provinces the bargaining unit comes from and it is unclear how to handle situations in which differing pieces of legislation cover different portions of the bargaining unit. Each observation is a collective bargaining settlement and contains information on the starting and

Ž

ending base wage rates typically the wage of the lowest paid bargaining unit

.

classification which were converted to real terms using the Canadian CPI. The bargaining unit size percent change is calculated as the annualized percent change in bargaining unit employment from the contract settlement date to the next contract settlement. In addition to the aggregate variables described above,

provin-Ž .

cial one-digit industry employment matrices 1714 and 4299–4425 was collected from CANSIM.

References

Abowd, J.M., Lemieux, T., 1991. The effects of international competition on collective bargaining

Ž .

outcomes: a comparison of the United States and Canada. In: Abowd, J.M., Freeman, R.B. Eds. , Immigration, Trade, and the Labor Market. University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 343–367. Abraham, K.G., Houseman, S.N., 1994. Does employment protection inhibit labor market flexibility?

Ž .

Lessons from Germany, France, and Belgium. In: Blank, R.M. Ed. , Social Protection versus Economic Flexibility: Is There a Trade-off? University of Chicago Press, Chicago, pp. 59–93. Adams, G.W., 1994. Canadian Labour Law, 2nd edn. Canada Law Book, Aurora, Ontario.

Atleson, J.B., 1983. Values and Assumptions in American Labor Law. Univ. of Massachusetts Press, Amherst.

Budd, J.W., 1996. Canadian strike replacement legislation and collective bargaining: lessons for the

Ž .

United States. Industrial Relations 35 2 , 245–260.

Business Council of British Columbia, 1995. Submission to the Ministry of Human Resources Development on the Proposed Prohibition on the Use of Replacement Workers. British Columbia, Vancouver, February.

Canada NewsWire, 1995. Bill 7 Receives Royal Assent and Becomes Law on Nov. 10th. Toronto, November 10.

Card, D., 1992. Using regional variation in wages to measure the effects of the federal minimum wage.

Ž .

Industrial and Labor Relations Review 46 1 , 22–37.

Card, D., Krueger, A.B., 1995. Myth and Measurement: The New Economics of the Minimum Wage. Princeton Univ. Press, Princeton, NJ.

Council of Ontario Construction Associations, 1992a. Comments on Proposed Reform of the Ontario Labour Relations Act. Toronto, Ontario, February.

Council of Ontario Construction Associations, 1992b. The Impact of Proposed Changes to Ontario’s Labour Relations Act: A Report from Ernst and Young. Toronto, Ontario, February.

Cramton, P., Gunderson, M., Tracy, J., 1999. The effect of collective bargaining legislation on strikes

Ž .

and wages. Review of Economics and Statistics 81 3 , 475–487.

Ellwood, D.T., Fine, G., 1987. The impact of right-to-work laws on union organizing. Journal of

Ž .

Political Economy 95 2 , 250–273.

Estreicher, S., 1994. Collective bargaining or ‘Collective Begging’? Reflections on antistrikebreaker

Ž .

legislation. Michigan Law Review 93 3 , 577–608.

Fares, J., Robert, J., 1996. Replacement Laws, Strikes and Wages. Unpublished paper, University of` Montreal.

Gramm, C.L., 1991. Empirical evidence on political arguments relating to replacement worker

Ž .

legislation. Labor Law Journal 42 8 , 491–496.

Gramm, C.L., Schnell, J.F., 1994. Some empirical effects of using permanent striker replacements.

Ž .

Contemporary Economic Policy 12 3 , 122–133.

Ž .

Gruber, J., 1994. The incidence of mandated maternity benefits. American Economic Review 84 3 , 622–641.

Gunderson, M., Melino, A., 1990. The effects of public policy on strike duration. Journal of Labor

Ž .

Economics 8 3 , 295–316.

Gunderson, M., Kervin, J., Reid, F., 1989. The effect of labour relations legislation on strike incidence.

Ž .

Canadian Journal of Economics 22 4 , 779–794.

Ž .

Lazear, E.P., 1990. Job security provisions and employment. Quarterly Journal of Economics 105 3 , 699–726.

Lee, H.D., Browne, M.J., Schmit, J.T., 1994. How does joint and several tort reform affect the rate of

Ž .

tort filings? Evidence from the State Courts. Journal of Risk and Insurance 61 2 , 295–316. LeRoy, M.H., 1993. The Mackay radio doctrine of permanent striker replacements and the Minnesota

Ž .

picket line peace act: questions of preemption. Minnesota Law Review 77 4 , 843–869. Levine, P.B., Trainor, A.B., Zimmerman, D.J., 1996. The effect of Medicaid abortion funding

Ž .

restrictions on abortions, pregnancies, and births. Journal of Health Economics 15 5 , 555–578. Long, R.J., 1993. The effect of unionization on employment growth of Canadian companies. Industrial

Ž .

and Labor Relations Review 46 4 , 691–703.

Martinello, F., Meng, R., 1992. Effects of labor legislation and industry characteristics on union

Ž .

coverage in Canada. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 46 1 , 176–190.

Ž .

Mitchell, O.S., 1990. The effects of mandating benefits packages. In: Ehrenberg, R.G. Ed. , Research in Labor Economics, Vol. 11. JAI Press, Greenwich, CT, pp. 297–320.

Neumark, D., Wascher, W., 1992. Employment effects of minimum and subminimum wages: panel

Ž .

data on state minimum wage laws. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 46 1 , 55–81. Olson, C.A., 1991. The use of strike replacements in labor disputes: evidence from the 1880s to the

1980s. Unpublished paper, University of Wisconsin-Madison.

( )

J.W. BuddrLabour Economics 7 2000 225–247 247 Ruhm, C.J., 1998. The economic consequences of parental leave mandates: lessons from Europe.

Ž .

Quarterly Journal of Economics 113 1 , 285–317.

Sales, J.E., 1984. Replacing Mackay: strikebreaking acts and other assaults on the permanent strike

Ž .

replacement doctrine. Rutgers Law Review 36 4 , 861–886.

Schaafsma, J., Walsh, W.D., 1983. Employment and labour supply effects of the minimum wage: some

Ž .

pooled time-series estimates from Canadian provincial data. Canadian Journal of Economics 16 1 , 86–97.

Schnell, J.F., Gramm, C.L., 1994. The empirical relations between employers’ striker replacement

Ž .

strategies and strike duration. Industrial and Labor Relations Review 47 2 , 189–206.

Spector, J.A., 1992. Replacement and reinstatement of strikers in the United States, Great Britain, and

Ž .

Canada. Comparative Labor Law Journal 13 2 , 184–232.

Starkman, A.L., 1993. The use of labour replacement in industrial disputes: a British–Canadian comparison. PhD Dissertation, University of Kent.

U.S. Congress, 1989. H.R. 4552 and the Issue of Strike Replacements. Hearings Before the Subcom-mittee on Labor–Management Relations of the ComSubcom-mittee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, July 14, 1988. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

U.S. Congress, 1991. Hearings on H.R. 5, The Striker Replacement Bill. Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Labor–Management Relations of the Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, March 6 and 13, 1991. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. U.S. Congress, 1993a. Legislative Hearing on H.R. 5. Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Labor–

Management Relations of the Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, March 30, 1993. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

U.S. Congress, 1993b. Hearings on H.R. 1280, Comprehensive Occupational Safety and Health Reform Act. Hearings Before the Subcommittee on Labor Standards, Occupational Health and Safety of the Committee on Education and Labor, House of Representatives, July 14, July 21, September 28 and October 20, 1993. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC.

U.S. Congress, 1995. Hearing on Executive Order 12954 and H.R. 1176, To Nullify the Executive Order Prohibiting Federal Contracts with Companies that Hire Permanent Replacements for Striking Workers. Hearing Before the Committee on Economic and Educational Opportunities, House of Representatives, April 5, 1993. U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, DC. Weiler, P.C., 1984. Striking a new balance: freedom of contract and the prospects for union

Ž .