A Cognitive Perspective

William E. Staley

© 2007 by SIL International

Library of Congress Catalog No: 2007-926704 ISBN-13: 978-1-55671-185-5

ISSN: 1934-2470

Fair Use Policy

Books published in the SIL e-Books series are intended for scholarly research and educational use. You may make copies of these publications for research or instructionsl purposes free of charge (within fair use guidelines) and without further permission. Republication or commercial use of SILEB or the documents contained therein is expressly prohibited without the written consent of the copyright holder(s).

Series Editor

Mary Ruth Wise

Volume Editor

Rhonda Hartell Jones

Compositors

List of figures . . . vii

List of tables . . . ix

Abstract. . . xi

Acknowledgements . . . xii

Abbreviations . . . xiii

1. Introduction . . . 1

1.1 Aims and Organization . . . 1

1.2 The Olo Speakers and Language Affiliation . . . 2

1.3 The Current Working Theory of Reference. . . 4

1.4 Summary . . . 6

2. The Olo Language . . . 7

2.1 Introduction . . . 7

2.2 Phonology . . . 7

2.3 Grammatical Characterization . . . 8

2.3.1 The general typology of the clause . . . 9

2.3.2 Word classes. . . 9

2.3.2.1 The verb . . . 9

Subject prefix . . . 10

Object infixes. . . 11

Object suffixes . . . 12

First and second person . . . 12

Third person . . . 13

Set 1 . . . 13

Set 2 . . . 14

2.3.2.2 Nouns . . . 15

Number . . . 15

Noun gender . . . 17

Names . . . 18

2.3.2.3 Adjectives . . . 18

2.3.2.4 Numerals . . . 19

2.3.2.5 Free Pronouns . . . 19

Genitive pronouns . . . 21

Reflexive pronouns . . . 22

Reciprocal pronouns . . . 23

2.3.2.6 Demonstratives . . . 23

Previous referent . . . 25

2.3.2.7 Adverbs . . . 25

2.3.2.8 Prepositions and subordinators . . . 25

2.3.2.9 Conjunctions and discourse particles . . . 26

2.3.3 Noun phrase . . . 27

2.3.3.1 General noun phrase. . . 27

2.3.3.2 Possessive noun phrase . . . 28

2.3.3.3 Genitive noun phrase . . . 28

2.3.4 Adjective phrase . . . 29

2.3.5 Time, aspect, and mood . . . 29

2.3.5.1 Locating events in time . . . 29

2.3.5.2 Continuous aspect . . . 29

2.3.5.3 Realis/irrealis . . . 30

2.3.5.4 Aptative . . . 30

2.3.5.5 Durative. . . 31

2.3.5.6 Event closure . . . 32

2.3.6 Grammatical roles . . . 32

2.3.6.1 Subject . . . 32

2.3.6.2 Object . . . 34

Manipulating the object—promotion and demotion. . . 35

Demotion . . . 35

Genitive raising . . . 35

Two objects . . . 36

Inverse . . . 36

2.2.7 Clausal complexities. . . 37

2.3.7.1 Serial clause construction . . . 37

The serial clause versus the clause chain . . . 37

The serial clause versus the serial verb construction. . . 38

2.3.7.2 Conjoining clauses . . . 41

2.3.7.3 Immediate sequence . . . 41

2.3.7.4 Clause listing . . . 42

2.3.7.5 Complementation . . . 42

Quotatives . . . 43

Cognition . . . 44

2.3.7.6 Clause subordination and relative clauses . . . 44

2.4 Summary . . . 45

3. The Rationale for Different Referential Forms . . . 47

3.1 Why Are There Different Referential Forms? . . . 47

3.2 Definition of Reference. . . 47

3.3 Referential Choice and the Environment . . . 51

3.3.1 Recency models. . . 51

3.3.2 Episode models . . . 53

3.3.3 Memorial activation models . . . 54

3.3.4 Prominence effects . . . 55

3.4 The cognitive effects of reference forms . . . 56

3.4.1 The environmental view versus speaker control . . . 57

3.4.2 Referential form as instructions to the comprehender . . . 57

3.4.3 Activation and search instructions . . . 58

3.5 Goal Oriented Activation . . . 59

3.6 Summary . . . 61

4. Methods . . . 63

4.1 Methods . . . 63

4.2 The Textual Data . . . 64

4.3 Dividing the Text . . . 64

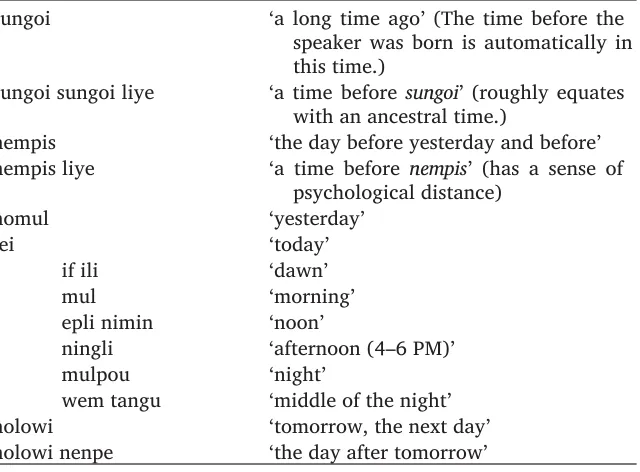

4.3.1 Temporal locations . . . 64

4.3.2 Spatial locations . . . 65

4.3.3 Punctuation . . . 66

4.3.4 Discourse markers. . . 66

4.3.5 Event coherence . . . 67

4.4 Referential Forms . . . 68

4.5 Analysis . . . 69

4.5.1 Referential distance . . . 69

4.5.2 Topic persistence . . . 70

4.5.3 Ranking of participants . . . 71

4.7 Summary . . . 71

5. Results and Analysis . . . 73

5.1 Introduction . . . 73

5.2 General Characteristics of the Database . . . 73

5.2.1 Participant introductions . . . 74

5.2.2 Post introduction references . . . 75

5.3 Referential Distance . . . 75

Referential distance measurements . . . 77

5.4 Topic Persistence . . . 80

Character importance . . . 83

5.5.1 Punctuation . . . 85

5.5.2 Periods. . . 88

5.5.3 Temporal boundaries . . . 90

5.5.4 Spatial change . . . 92

5.5.5 Discourse markers. . . 93

5.5.6 Verbal cohesion. . . 96

5.6 Introduction of Referents . . . 97

5.6.1 Expectations of new referents . . . 97

5.6.2 New referent data. . . 98

5.7 Summary . . . 100

5.8 Conclusion . . . 101

Appendix A . . . 105

Texts . . . 105

1. Amerika by L. . . 105

2. Toilet by A.F. . . 114

3. Two Men with a Ghost by M.S., July 1987 . . . 122

4. Trip to Abrau by A.F., September 1988 . . . 124

5. Hunting at Abrau by A.F., September 1988 . . . 132

6. Coming Home from Abrau by A.F., September 1988 . . . 138

7. Nangou Palowi Metine by S.P. . . 142

8. Fishing Trip by M.S. . . 145

Appendix B . . . 149

The Custom Database Program . . . 149

Figure 1.1. Map of the Olo language area . . . 3

Figure 3.1. Model of discourse production . . . 60

Figure 5.1. Significant differences for topic persistence distinctions . . . 83

Figure 5.2. Graph of the percentage of total occurrences of referential forms . . . 88

Figure 5.3. Graph of the percentage of different forms following a period . . . 90

Table 2.1. Olo vowel chart . . . 7

Table 2.2. Olo consonant chart . . . 8

Table 2.3. Olo subject prefixes . . . 10

Table 2.4. Olo object infixes . . . 11

Table 2.5. Olo first- and second-person suffixes . . . 12

Table 2.6. Olo third-person object suffixes. . . 13

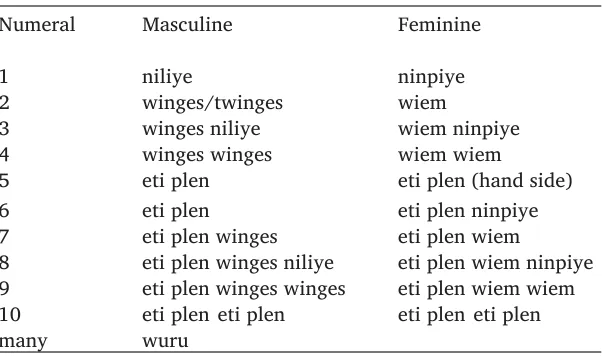

Table 2.7. Olo numerals from 1 to 10 . . . 19

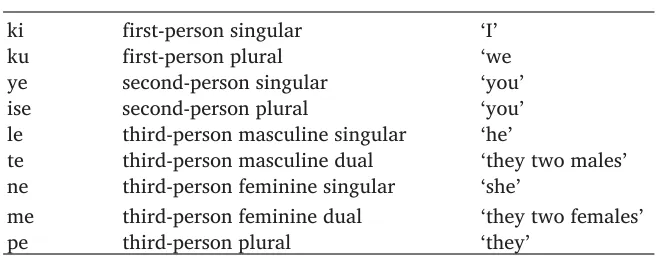

Table 2.8. Olo free pronouns . . . 20

Table 2.9. Olo pronouns by person and number . . . 20

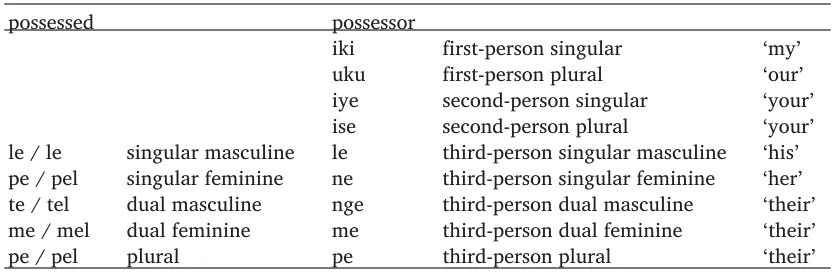

Table 2.10. Olo genitive pronouns . . . 22

Table 2.11. Olo reflexive pronouns . . . 22

Table 2.12. Olo demonstratives. . . 25

Table 2.13. Olo discourse linker . . . 27

Table 2.14. Morphosyntactic forms that realize referents in Olo . . . 45

Table 3.1. Topic continuity hierarchy . . . 58

Table 3.2. Effects on activation of participants by different referential devices . . . 58

Table 3.3. Basic activation instructions . . . 59

Table 4.1. Olo temporal divisions. . . 65

Table 4.2. Olo primary spatial verbs . . . 65

Table 4.3. Olo secondary spatial verbs . . . 66

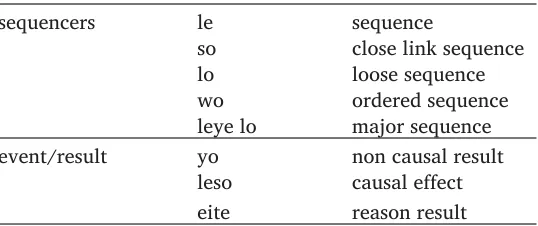

Table 4.4. Olo discourse linkers . . . 67

Table 5.1. Initial introduction referential forms and the number of their occurrences . . . 74

Table 5.2. Post introduction referential forms and the number of their occurrences . . . 74

Table 5.3. Third-person post introduction referential forms . . . 75

Table 5.4. Central tendencies of referential distance for different forms . . . 77

Table 5.5. Frequency of occurrence of different referential forms at specific referential distances . . . 78

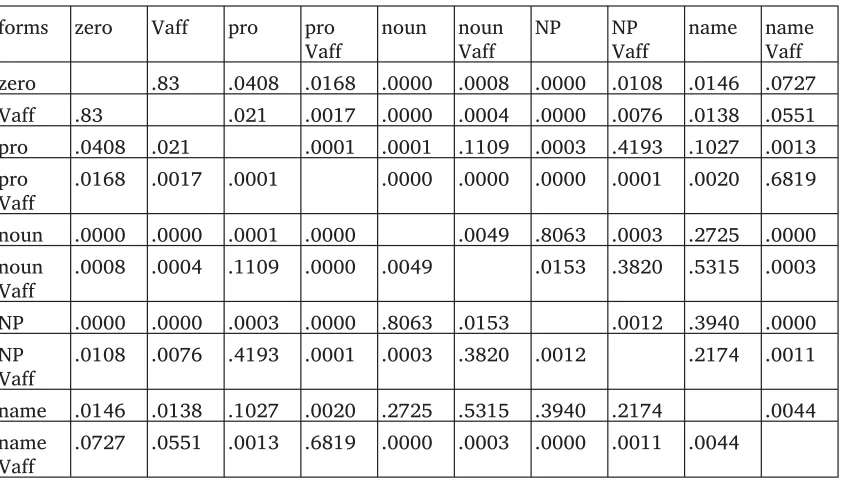

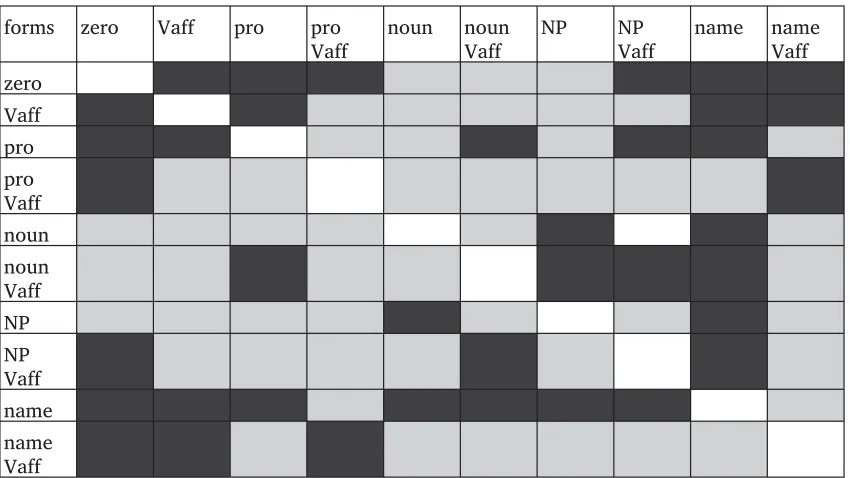

Table 5.6. Probability of error values for referential distance distinctions . . . 80

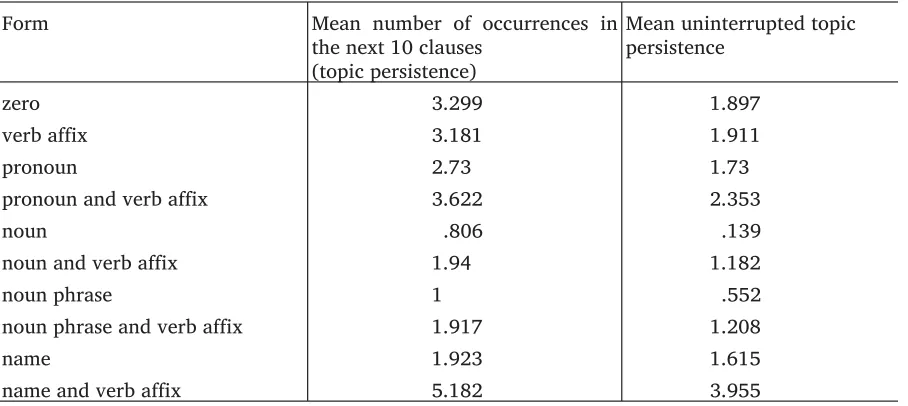

Table 5.7. Mean values of topic persistence for each referential form . . . 81

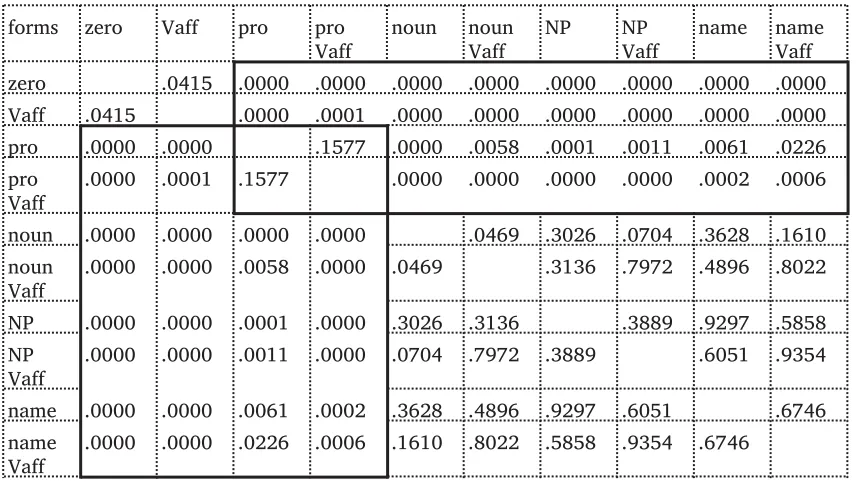

Table 5.8. Probability of error values for topic persistence distinctions. . . 82

Table 5.9. Comparison of very infrequent and very frequent referents . . . 84

Table 5.10. Occurrence of punctuation with different referential forms. . . 85

Table 5.11. Percentage of forms that occur with or without punctuation . . . 86

Table 5.12. Occurrence of punctuation with different referential forms at a referential distance of one . . . 87

Table 5.13. Occurrence of punctuation with different referential form sets at a referential distance of one . . . 87

Table 5.14. Percentage of occurrence of different form sets depending on punctuation . . . . 88

Table 5.15. Occurrences of different referential forms following a period. . . 89

Table 5.16. Percentage of occurrence of different form sets depending on punctuation . . . . 89

Table 5.17. Frequency of occurrence of referential forms on the basis of temporal change . . . 91

Table 5.18. Percentage of occurrence of referential forms on the basis of temporal change . . 91

Table 5.19. Frequency of occurrence of referential forms on the basis of spatial change . . . . 92

Table 5.20. Percentage of occurrence of referential forms on the basis of spatial change. . . . 93

Table 5.21. Frequency of occurrence of referential forms on the basis of discourse markers . . 94

Table 5.22. Percentage of occurrence of referential forms on the basis of discourse markers . . 94

Table 5.23. Frequency of occurrence of referential forms on the basis of discourse markers with a referential distance of one . . . 95

Table 5.24. Percentage of occurrence of referential forms on the basis of discourse markers with a referential distance of one . . . 95

Table 5.25. Frequency of occurrence of referential forms on the basis of verbal cohesion . . . 96

Table 5.26. Percentages of occurrence of referential forms on the basis of verbal cohesion . . 97

This book investigates the phenomena that influence the choice of referential form in Olo narratives. Olo is a language of Papua New Guinea. The investigation is a text-based, quantitative examination which compares the adequacy of different models of referential management. This work uses insights from cognitive studies involving the mental activation of referents in discourse to develop a model of referential management called Goal Oriented Activation. It departs from previous work by claiming the choice of referential form is not based solely on the current activation level of a referent, but also on the activation level that the speaker wants to achieve in the hearer at the end of the sentence. Fur-ther, the choice of form is also dependent on the overall goals of the speaker, who will choose forms not only based on the activation level of the particular referent, but also based on the desired activa-tion levels of the other participants. In this way the speaker will attempt to keep the important referents more activated than the other participants in the story.

The main competing models are current state models. They hold that referential form is based only on what has happened previously in the narrative. The current state models that were considered in this book are: recency, episodes, and memorial activation. All of the competing models were found in-adequate to account for the data found in the Olo texts. All of the tests conducted supported the Goal Oriented Activation model. A crucial piece of data in comparing these models is the introduction of new third-person referents by minimal forms. The participants in question are fully referential, even though they are introduced by a pronominal affix on the verb. This evidence falsifies the recency, epi-sodes, and memorial activation models but is in complete harmony with Goal Oriented Activation.

Also included in this book is information on the Olo language. This language is non-Austronesian and unrelated to highland clause-chaining languages. The information presented here, while not a complete reference grammar, provides material for those interested in both Papua New Guinea and comparative typology.

Editor’s note

The original version of this book was presented to the University of Oregon as a Ph.D. dissertation in 1995. Since the author’s untimely death in January 2004 precludes working with him on a revision, it is published with only minor revisions.

The author and his wife carried out field research on the Olo language under the auspices of the Summer Institute of Linguistics, Papua New Guinea, during the years 1981–1991.

As always a work of this size cannot be done without the help and support of many people. In partic-ular I want to express my sincere appreciation to Russ Tomlin for his guidance and help in producing this work. Scott DeLancey was an unflagging critic and helped me refine my writing and sharpen my thoughts. I appreciate the effort he has put into this work. I also want to thank my other dissertation committee members, Derry Malsch and Dare Baldwin for their contributions. I must make mention of two University of Oregon faculty members who have assisted me, Tom Givón and Colette Craig Grinevald. Tom made some very helpful suggestions on the first two chapters. Colette gave me tremen-dous help in improving my writing, both style and clarity.

I want to express my thanks to the cognitive linguistics study group who listened to my ideas and provided comments. Of particular help were Linda Forrest, Lynn Yang, and Myung-Hee Kim. Kweku Osam also provided invaluable help and support. I also want to thank Philip Meguire for his advice on statistics.

I want to acknowledge the help of my wife Rochelle, who read many drafts and suggested many im-provements. Thanks too, to our children Megan and Neal, who suffered through many table discus-sions on reference and a preoccupied father.

I want to acknowledge the financial help of the Summer Institute of Linguistics that made this work possible, as well as the help of all my colleagues.

Finally thanks be to the Lord Jesus Christ, who gave me the grace and perseverance to see it through.

Bill Staley

University of Oregon 1995

ABL [ablative] M2 [see CB]

APT [aptative] M3 [> so that]

ASS [associated] NCR p. 206, 210

C [> near] NEG negation

[CB combined sequence] nm nonmasculine

CE NP noun phrase

CIR O object

CNC concluded ont

CNT continuative p/PL plural

CMP completive PRP [> ASS]

CONT p. 194 (CNT?) PRV previous

CP [> near] QUES question

DEM demonstrative RD referential distance

dis RFX reflexive

dst RSN [> LS]

d dual s/SG singular

D S subject

DUR durative SBD subordinate

DX [> this] SP

EBT SPR

EMP emphasis SQ [sequence]

EXT TMP

f feminine TP topic persistence

I inverse TS [ordered sequence]

INT intensifier V verb

IR irrealis VOC vocative

ISQ immediate sequence YNQ yes/no question

LS [loose sequence] 1 first person

m masculine 2 second person

M1 [> SQ] 3 third person

Editors note: We have attempted to fill in gaps in this abbreviations page. We have used square brackets where the author's intention was not clear or where we have substituted another abbrevia-tion. A few abbreviations are left undefined.

In examples of more than one clause, the punctuation follows that provided by Olo speakers and the author (see section 4.3, 4.3.3, and 5.5.1). Capitalization, however, is used only for proper names

Introduction

1.1 Aims and Organization

One of the primary distinguishing features of man as a species is the rich communicative ability among species members. This communication occurs primarily through language. Language has a number of functions, such as the transfer of information, showing group solidarity, and communicating emotional states (Brown and Yule 1983). In all these the communicator is giving information about the state or activ-ity of some object. That object may be real or imaginary. It may be a single individual or a group, coded as a either a unit or as a collection of units. For example, given a set of five human males there are a variety of ways to refer to them. We can refer to them as individuals by name: John, George, Bill, Pat, and Harry. We can refer to them as a collection of individuals by using such terms asthe men or the boys. Or we can refer to them as a unit with a collective term such asthe gang(Fleming 1978). Another collective term that I have used all along isthem. The pronominal form is a common way of referring to an object. According to work by Brown (1983) and Givón (1983e) pronominal forms are the single most common referential form in English. Givón (1983e) found pronouns account for 57 percent of the referential forms in spoken English. Brown’s work on written English (Brown 1983) while showing a lower percentage, 27 percent, had pro-nominal forms being the most frequent referential device. Much interest has been expressed in determin-ing why pronouns are used. Because they are such a common type of reference, ldetermin-inguists and psycholinguists have wanted to determine both why language producers1employ pronouns versus other reference forms, and what effect the use of reference forms has on language comprehenders.

The study of referential form has been going on for many years. Much of the work has been done in-side the sentence boundary. Bloomfield (1933) talks about pronouns as one word class that substitutes for other word classes. In his view pronouns are used to replace nouns in an utterance. Bloomfield characterized the pronominal substitute as being used to replace a recently mentioned antecedent, al-though he acknowledged that in certain cases likeit’s raining, the pronoun has no antecedent. The early work of many linguists involved limiting the scope of the research to describing the structures that can be found in a sentence. One branch of the study of reference has evolved from this perspective. Refer-ential phenomena have been viewed as one means of gaining insight into the syntactic rules that oper-ate inside the sentence (Chomsky 1980; Cullicover 1976).

While some linguists felt that they needed to limit the scope of their investigation to the sentence (Chomsky 1957, 1965), among others there was an increasing awareness of the need to examine the whole context of an utterance (Ballard, Conrad, and Longacre 1971; Grimes 1975, 1978; Longacre 1968, 1970; Pike 1964; Wise 1968). The interest in discourse in general extended to trying to determine the conditioning environments which govern the choice of referential form. Grimes edited a volume that looked at this question in a number of languages (Grimes 1978). This present work is intended to build on this discourse tradition.

1

1Language producer is used to include both speakers and authors. Much work has been done both on spoken and written

This study has two goals. The first is to provide an account of the different referential forms in Olo, a minority language in Papua New Guinea, and to show why different referential forms are chosen. To adequately explain the different referential forms, they must be set within the context of a grammati-cal description. Therefore a basic grammar of Olo is included in this work. Making information about Olo more widely known is the second goal of this study. The main thrust of the basic grammar revolves around the morphosyntactic devices used to realize participants in Olo. While the description of Olo is focused primarily on morphosyntactic issues of interest in discourse analysis, it is broad enough that someone interested in languages of Papua New Guinea should find some useful material. The gram-matical analysis is based on language data collected during a period of ten years (1981–1991) while I worked in Papua New Guinea under the auspices of SIL International. The discourse analysis is text based. The texts were either recordings of stories told primarily to Olo speakers or written for Olo speakers. The texts are given in appendix A.

Chapter 1 gives a general background on the Olo-speaking people and a general outline of the theory of reference being pursued in this work. Chapter 2 gives a basic introduction to the Olo language. Chapter 3 defines reference and lays the groundwork for examining reference from a cognitive per-spective, while chapter 4 discusses the methods employed in the analysis of the data. Chapter 5 dis-cusses the results and summarizes the conclusions of the study.

1.2 The Olo Speakers and Language Affiliation

Olo is a non-Austronesian2 language of Papua New Guinea and is spoken by approximately 13,000 speakers. The Olo were little known before the end of World War II. Since then some work has been done in both ethnography (D.E. McGregor 1969, 1982; Mitchell 1973, 1979, 1987, 1990) and linguistics (A. McGregor 1983; D. E. McGregor, 1983b, 1983c, 1983d; Staley 1989, 1994a, 1994b, 1994c, 1994d). This current study will help make known the people and fill in some of the gaps regarding the Olo language. The Olo speakers live in a pear-shaped area extending up to Aitape Township in the north and some thirty miles south in the Sandaun (West Sepik) Province of Papua New Guinea (see the map in figure 1.1). The speakers are spread out among fifty-four villages and the Poro Resettlement Scheme. There are also numerous speakers spread throughout other cities and rural areas of Papua New Guinea. The majority of the population live south of the Torrecelli Mountains, with roughly 1,200 residing in coastal villages. The southern groups live on high ridges while the coastal people live on the plain. The coastal area is serviced out of Aitape while south of the mountains, Lumi is the main government center.

Mitchell summarizes the social life of the people:

The Wape3live in a mountainous tropical forest habitat, are slash and burn horticulturalists [sic] and reside in sedentary villages. Post marital residence is generally virilocal, patrilineal clans are ideally exogamous while patrilineages are strictly so. Marriage is by bridewealth and polygyny is permitted but rare. Cousin kin terms are Omaha. The society is egalitarian in terms of male status and, although the society is hierar-chical in terms of sex and age differences, both women and the young enjoy higher status than in many New Guinea societies. While most Wape are nominal Christians, traditional religious beliefs and practices are of major importance. Most men also are members of curing societies that involve the population in an extensive system of culturally significant ritual exchanges. (Mitchell 1987:18)

Olo is a member of the Wape 3 family of the Torrecelli Phylum. The Torrecelli Phylum is a phylum level isolate (Laycock 1975). The Olo language is divided into three dialects (Staley 1989): Lumi, Somoro, and Coastal. A map with the dialect boundaries is given in figure 1.1. The boundaries of the dialects have been determined based on grammatical considerations, amount of shared words, and sociolinguistic consider-ations. These boundaries should not be considered absolute. Rather, they delineate where major changes take place. Both within the dialects and across dialects, however, there is dialect chaining.

2The term Papuan is often applied to these languages. Using the term Papuan implies more affiliation than there actually is.

Olo is a member of the Torrecelli Phylum which is genetically distinct from the other language phyla of Papua New Guinea. It bears little structural relationship with the “classic” New Guinea highlands language which has distinctives such as medial/final verbs and switch-reference marking.

The data in this study are from the Somoro dialect. While many of the conclusions should hold for the other dialects, there is not a one-to-one correspondence.

1.3 The Current Working Theory of Reference

The study of reference and referential forms is not a modern phenomenon. The philosophical under-pinnings can be traced back to Aristotle. In this section I give a general outline of my theory of why a speaker chooses a specific form to refer to an object so the reader can understand how the different morphosyntactic devices in Olo are used to make reference to objects. Chapter 3 will trace the histori-cal views of reference as well as comparing and contrasting the different theories.

Many different theories have been proposed to account for the use of nouns or pronouns in dis-course. They can be divided into four general categories: recency, episodes, prominence, and me-morial activation. Each of these approaches suffers from various flaws. The recency approach, including topic persistence basically states that certain devices are used if the most recent mention is only a few (one or two) clauses preceding the current mention (see Givón 1983a, 1983b, 1983c, 1983e; Jaggar 1983; Payne 1993). While this approach accounts for large amounts of data, it fails to handle the influence on referential choice of various discourse boundaries or topic persistence. Episode approaches (Anderson, Garrod, and Sandford 1983; Kintsch and van Dijk 1978; Marslen-Wilson, Levy, and Tyler 1982; Pu 1991; Tomlin 1987; van Dijk 1982; van Dijk and Kintsch 1983) claim that the choice is based on episode boundaries in the text. The claim is that nouns are used after an episode boundary and pronouns within an episode. This account fails because it does not address the use of pronouns across episode boundaries, nor the use of nouns inside an episode. The prominence account (Clancy 1980; Hinds 1977; Kuno 1976; Kuno and Kaburaki 1977; Perrin 1978) is not as well quantified as the others. Essentially it claims that the choices of referential form are based on how important a given referent is. The problems with this account have more to do with its testability than its general observations. The Olo data generally supports the idea that the prominence of a referent influences the choice of referential forms. It can not be claimed that prominence is the most important factor however. The fourth approach, and the most promising, is that of memorial activation (Gernsbacher 1989, 1990; Tomlin and Pu 1991). However, all current work in activation considers the choice of a noun versus a pronoun to be based solely on current ac-tivation. In this approach the choice of referential form is made only according to the activation level of the referent at the moment of utterance. The activation level is affected by episode bound-aries at least in Tomlin and Pu’s work (1991). Within an individual episode a recency approach is adopted. In this view the choice of referential form cannot be influenced by any subsequent usage. The model further predicts that all new referents would be introduced by nouns or noun phrases. While this proposal does account for large amounts of the current data, it specifically does not ac-count for differences in referential form being correlated with topic persistence, or the use of ver-bal affixes to introduce new participants.

Underlying all uses of referential devices is the premise that the speaker is attempting to communi-cate with his listener, or the writer with his reader, and will therefore choose referential forms that al-low the listener to connect the form with the object that the speaker intended. A second key premise is that a speaker does not speak in isolated sentences, but rather builds a discourse. In this way the choice of a referential form is dependent not only on the previous utterances, but is foundational for future utterances.

When a listener hears an utterance, the different referential forms have different effects on his men-tal state. In particular, the activation levels of different referents are changed. Activation is essentially a measure of how accessible a concept is to a person. A concept that is highly active can be accessed faster than a concept that is less active. The activation level is not constant, it can be suppressed by the activation of other concepts4and it can decay with time, or with the crossing of boundaries in the dis-course structure (Clark and Sengul 1979; Garrod and Sanford 1988; Sanford and Garrod 1982). Be-sides suppression, activation can also be enhanced by a new reference to the concept. The more

explicit the referential form, the more dramatic the increase in activation of the object referred to and the more suppressed the activation of any non referent.5Other features also affect the activation level of referents. One of the most important is the advantage of first mention (Gernsbacher 1989, 1990; Gernsbacher and Hargreaves 1988). All other things being equal, the referent that is mentioned in a sentence first will have a higher activation level than any of the referents in following positions. The amount of coding material also affects the activation levels, so that a noun has a different effect from a pronoun (Gernsbacher 1990), which is different from zero (Chang 1980; Corbett and Chang 1983). Different grammatical and/or semantic roles could well affect the activation of a referent, but this has not been explicitly tested where it was not confounded with the advantage of first mention.

Given the shortcomings of previous work (recency, episode, prominence, and memorial activation) it is necessary to move to a comprehensive account of activation. I propose a melding of prominence and activation. I call my approach “Goal Oriented Activation.” In this approach the language producer adjusts the activation of the different participants in the discourse, building not only on the current ac-tivation level, but also according to what the producer wants to do in the rest of the discourse with the particular participant. So that the choice of referential form is not determined simply by the producer’s estimation of how active the participant is in the mind of the comprehender, but also how active the speaker wants this particular referent to be vis-á-vis all other participants. The producer takes into ac-count his/her estimate of the activation levels in the mind of the comprehender and uses the appropri-ate device to change the activation to the level he/she wants the comprehender to have at the end of the sentence. This then builds on the previous sentence and lays the foundation for the next sentence. The form of reference chosen should ideally unambiguously denote the participant(s) and adjust the relative activation of the participant vis-á-vis all other participants.

The basic techniques employed for this study involve counting the different occurrences of referen-tial forms in the text database. The instances are marked for referenreferen-tial distance, topic persistence, and occurrence of boundary phenomena. The basic methodology was pioneered by Givón (1983d). The two most important changes I have made to Givón’s methodology involve the treatment of new refer-ents and distant references. In my account new referrefer-ents are kept distinct from later references. The data from new referents is crucial to the argument I am making. Givón did not count more than twenty clauses back for a referent to find the last mention. I impose no such arbitrary limit. This results in more variance in the data. To handle this I use the median rather than the mean to report a figure for the referential distance of each group. The boundary phenomena are simply a yes/no question of whether a certain boundary has occurred since the last mention.

In examining the morphosyntactic devices used to denote a referent in Olo we find some basic dis-tinctions. Firstly, the choice between pronominal6and nominal forms is correlated with referential distance. Pronominal forms have a median referential distance of one, while the median for nominal forms is three or higher. This is consistent with the accounts of both memorial activation and Goal Ori-ented Activation. The topic persistence of pronominals is higher than that of the nominals. Verbal af-fixes and zero have a lower topic persistence than the combination of a free pronoun and a verbal affix. The topic persistence data also distinguishes free forms with no coreferential verbal affixes from free forms with coreferential affixes. This pattern is reported by Payne for Yagua (1993) as well. The topic persistence data is inconsistent with memorial activation, but is highly consistent with Goal Oriented Activation. The boundary phenomena of intonation/punctuation, temporal change, spatial change, and discourse markers also can be correlated with the different referential forms as shall be discussed in detail in chapter 5.

The referential forms used to introduce new referents are inconsistent with the accounts of memo-rial activation and episodes. Both accounts would predict that all unknown referents would be intro-duced by nominals. However, unimportant referents can be introintro-duced by minimal devices, either zero or a verbal affix. All seven instances of introduction of new referents by zero are for referents that occur five or fewer times in the text. In the case of verbal affixes fifteen of the seventeen occurrences

5The term competing referent is sometimes used here. It is best to think of referents as competing when they are ambiguous

and each “competes” for the resolution in their favor. In this case a referent that does not compete in the sense that there is no way it can be confused with the referent mentioned still has it’s activation suppressed.

are for referents that occur five or fewer times. That any occur is counter to memorial activation and episodes, but fully supports the account of Goal Oriented Activation.

1.4 Summary

The Olo Language

2.1 Introduction

This chapter presents some aspects of the phonology and grammar of the Olo language, including the sound system, practical orthography, some aspects of the morphosyntax, and the semantics of Olo. This information is intended to lay the foundation for understanding the use of nouns and pronouns in Olo. The material presented is not intended to be a reference grammar, but should still be of interest to investigators of New Guinea languages. Olo is member of the Torrecelli Phylum and the structures of the language are distinct from both Austronesian and Highland Papuan languages.

2.2 Phonology

Except where otherwise noted the data in this study are given in the practical orthography devel-oped for Olo. The orthography is a compromise between the phonemic contrasts in the language and the Tok Pisin orthography. Three sounds that are distinguished in Olo do not have that distinction pre-served by an orthographic symbol.

The Olo language has seven vowels: /i,I, ¯, a, u,U, o/. The phoneme /¯/ has an allophone [æ] which only occurs before velars and is symbolized in the orthography ase. A chart of the vowels is given in ta-ble 2.1.

Table 2.1. Olo vowel chart

Front Central Back

high i u

tense

high I U

lax

mid ¯ o

low a

While the sound system has seven vowels, the orthography only uses five vowels; /I/ and /U/ are normally symbolized as “i” and “u”, respectively. They are also symbolized by a mid vowel in two cir-cumstances. The first is if there is a minimal pair with a word that is based on the difference between the mid vowel and high vowel, as in (1).

(1) [aisi] aisi ‘sell’ [aisI] aise ‘buy’

The second environment where high lax vowels are written as a mid vowel is near a high vowel that has the same front/back feature as the mid vowel, as in (2).

(2) [Uru] oru ‘hair on the head’

The consonants of Olo are /p, t, k, f, s, l, r, m, n,N, w, y/ as shown in table 2.2.

Table 2.2. Olo consonant chart

labial alveolar velar

stops p t k

fricatives f s

lateral l

liquid r

nasals m n N

semi-vowels w y

The stops in Olo are lenis and unaspirated. Voicing is noncontrastive for stops. Olo has three nasals, the bilabial (m), alveolar (n), and velar (N). While both the bilabial and alveolar nasals have full distri-butions, the velar nasal only occurs before a velar stop. It is contrastive with the alveolar nasal as shown in (3).

The orthography for the consonants is regular and for the most part reflects the phonetic symbols given in table 2.2. The one distinction relates to the marking of the velar nasal. The distinction be-tween the velar and alveolar nasals is made not on the nasals themselves, but rather on the velar stop. The orthographic symbolsngare phonetically [Ng]. All other occurrences of n are alveolar nasals in-cluding the sequence ofnk. The phonetic and orthographic representations are given in (3).

(3) [wangu] wanku ‘a man’s name’1 [waNgu] wangu ‘land crab’

Stress is mostly predictable, occurring on the penultimate syllable. There are a few words which have the antepenultimate syllable stressed. A contrastive pair is given in (4).

(4) wai.kó.pou ‘man’s name’ wá.ko.pou ‘wooden pestle’

2.3 Grammatical Characterization

The general outline of this section involves a typological characterization of Olo, an examination of the structure of the simple clause, and its constituents and their structures. This is followed by a discus-sion of the aspect and mood system. This information is essential to understanding the flow of time and activity in a narrative discourse and is used in examining boundaries in the texts. The final section dis-cusses complex sentence and clause constructions including verb complements, conjoined clauses, and serial clauses.

1The use of a man’s name for the contrasting pair in both this example and the next is only epiphenomenal and does not in

2.3.1 The general typology of the clause

In broad typological terms, Olo can be characterized as an SVO (Subject, Verb, Object) language (A. McGregor 1983; Staley 1994b). Examples showing this ordering are given in (5) and (6). The simple declarative unmarked ordering is SVO. The occurrence of a third-person object infix (marked by an un-derline) as in (5), versus a suffix, as in (6), is a function of verb class. A discussion of verb classes in Olo can be found in the next section as well as Staley (1990 ms, 1994b, 1994c). There is a prefix on the verb which marks the subject of the verb, and provides information about the person, number, and gender2of the subject. Objects are marked as well with the person, number, and gender information occurring as either a suffix or infix.

S V O

(5) Ales l-olto luom

Alex 3m-dip.3m sago

Alex dips sago.

S V O

(6) Martin l-osi-ene Rita

Martin 3m-attack-3f Rita

Martin attacked Rita.

While the normal, unmarked order in Olo is SVO, that is not the only order. The object can be fronted to initial position, as in (7). It is also possible for the subject to remain a free noun phrase when the object is fronted, as in (8).

(7) ki l-irpei-ki

I 3m-speak-1s

Me, he spoke to me!

(8) ki Kowi l-irpei-ki

I Kowi 3m-speak-1s

It was me Kowi spoke to.

Examples (7) and (8) show the type of construction that functions similarly to the passive in English. It could be translated “I was spoken to by Kowi”. Neither of the translations exactly reflects the con-struction in Olo. Olo has no morphosyntactic passive, nor is the fronting of the object to a topic posi-tion a type of the “It was X…” cleft construcposi-tion in English.

Before examining the clausal relations, both semantic and grammatical, let us turn to the grammati-cal structures that make up the clause. Doing this will provide information that is needed to support the analysis of the different relations involving clausal arguments.

2.3.2 Word classes

The large open word classes in Olo are verbs and nouns. Adjectives make up the third largest class. The minor classes consist of numerals, pronouns, demonstratives, adverbs, prepositions and subordinators, and conjunctions and discourse particles.

2.3.2.1 The verb

The verb is the central element in the clause. Often the clause is only composed of a single verb with no free standing arguments.

(9) a. k-e b. l-ifei c. n-aplo-pe

1s-go 3m-sit 3f-pierce-3m

I go. He sits. She pierces them.

Depending on their class, verbs can take up to four different affixes. They can take a subject prefix, an object infix, an object suffix, and can reduplicate part of the verb root to mark continuous aspect. The discussion of the continuous aspect will be handled under the section dealing with aspect and mood.

Subject prefix

The subject prefixes distinguish person: first, second, and third; number: singular, dual, and plural; and gender in third person. The Olo genders are masculine and feminine. Table 2.3 gives the subject prefixes.

Table 2.3. Olo subject prefixes

k- first-person singular ‘I’

w- first-person dual ‘we two’

m- first-person plural ‘we’

Ø- second-person singular ‘you’

y- second-person plural ‘you’

l- third-person singular masculine ‘he’ n- third-person singular feminine ‘she’ t- third-person dual masculine ‘they two’ m- third-person dual feminine ‘they two’3

p- third-person plural ‘they’

The following examples show the subject prefix on both intransitive (10) and transitive (11) verbs.

(10) Wamnei n-a

Wamnei 3f-die

Wamnei dies.

(11) Kowi l-etesi-ne Ros

Kowik 3mk-hit-3fr Roser Kowi hit Rose.

Not all verbs take the subject prefix for phonological reasons. Vowel-initial verbs take the prefix. The only consonant-initial verbs that can take prefixes are those that start with /r/ and /l/; they can take some of the verbal prefixes, specifically: /k, p, t, m/, as in (12)–(14). These are more common in writing than in speech. Some speakers never use them, other speakers will only use them in slow and deliberate speech. No speaker has been observed using them all the time. Speakers who use them in slow and deliberate speech will consistently use them in writing. This use I believe reflects that they are morphologically “present” but deleted because of phonological constraints.

(12) a. Kowi na-iye b. pe na-iye

Kowi call-2s they call-2s

Kowi calls you. They call you.

(13) a. ki k-ratei b. le ratei c. *le l-ratei

I 1s-live he live he 3m-live

I live. He lives

(14) a. pe p-retai b. ne retai c. *ne n-retai

they 3p-know she know she 3f-know

They know. She knows.

With one verb,lolpo‘fight’, the prefix is optional. This may be in part due to the semantic constraint that the subject of this verb must be plural. A fight,lolpo, must involve more than two people. This optionality is only for this verb, so the semantic explanation is the most likely.

(15) metea. p-lolpo b. mete lolpo

men 3p-fight men fight

The men fight. The men fight.

Object infixes

There are thirty-four verbs in the Somoro dialect which use an infix to refer to third-person objects. All these verbs require the object to be marked. The infix normally occurs following the vowel of the first syllable. The object infixes are given in table 2.4. They are underlined throughout this work.

Table 2.4. Olo object infixes

-l- ‘him’

-n- ‘her’

-ut- ‘two males’ -m- ‘two females’

-p- ‘them’

Example (16) shows the verbkali‘get him’, inflected with the different third-person infixes.

(16) ne kali4 ‘She gets him.’

she get.3m

ne kauti ‘She gets two males.’

she get.3md

le kani ‘He gets her.’

he get.3f

le kami ‘He gets two females.’

he get.3fd

le kapi ‘He gets them.’

he get.3p

That these are clearly infixes can be shown from comparing (16) with (17). The parts of the word that remain constant are the outer edges, which are obviously distinct in the different examples.

(17) reltapo ‘put him on it’ put.3m (on something else)

routapo5 ‘put the two of them (m.) on it’ put.3md (on something else)

rentapo ‘put her on it’ put.3f (on something else)

remtapo ‘put the two of them (f.) on it’ put.3fd (on something else)

reptapo ‘put them on it’ put.3p (on something else)

Object suffixes

Olo uses suffixes to mark all first and second-person objects. Third-person objects are marked for some verbs by suffixes and for other verbs by infixes.

First and second person

First- and second-person objects are realized by suffixes. This pattern applies to all transitive verbs including the thirty-four verbs which take third-person object infixes. The suffixes which realize first and second-person objects are given in table 2.5.

Table 2.5. Olo first- and second-person suffixes

-iki first-person singular ‘I’

-uku first-person plural ‘us’

-ye second-person singular ‘you’

-ise second-person plural ‘you’

If one of the object-infix-taking roots is inflected for first or second person, the root can undergo rather drastic but regular alternation. If the vowel in the first syllable is either /a/ or /e/, the first sylla-ble of the root becomes an /ei/. This form is also used for the reciprocal, as will be discussed below.

(18) kali ‘get him’

get.3m

keiye-iki ‘get me’ get-1s

keiyo-uku ‘get us’ get-1p

keiye-iye ‘get you’ get-2s

keiye-ise ‘get you.pl’ get.2p

(19) a. p-alfo p-eifo-iki

3p-put.inside.3m 3p-put.inside-1s

They put him inside something. They put me inside something.

b. l-anei l-eiye-iki

3m-eat.3f 3m-eat-1s

He eats her. He eats me.

c. p-alpo p-eipo-iki

3p-shoot.3m 3p-shoot-1s

They shoot him. They shoot me.

d. l-eptei l-eite-iki

3m-put.3p 3m-put-1s

He puts them. He puts me.

First- and second-person suffixes do not distinguish gender and only make a singular/plural distinc-tion, as in (20a). If a speaker desires to distinguish a dual from a plural for a first- or second-person ref-erent, a free pronoun must be used in addition to the suffix, as in (21).

(20) a. l-eila-iki b. l-eila-uku c. l-eila-iye d. l-eila-ise

3m-lift-1s 3m-lift-1p 3m-lift-2s 3m-lift-2p

He lifts me. He lifts us. He lifts you. He lifts you (p).

(21) a. l-eila-uku ronge b. l-eila-ise rom

3m-lift-1p md 3m-lift-2p fd

He lifts us two men. He lifts you two women.

Third person

The Somoro dialect of Olo has two main suffix sets to mark third-person objects. There are two dis-tinguishing features of the suffix sets. The first is that the third-person masculine suffix is-oor-woin set 1 andØin set 2.6The other difference is that the other set 1 suffixes have an initiale, which does not occur with the second suffix set. Examples of set 1 are given in (22), (23), and of set 2 in (24). The two suffix sets are given in table 2.6.

Table 2.6. Olo third-person object suffixes

set 1 set 2

-(w)o Ø- third singular masculine ‘him’ -ene -ne third singular feminine ‘her’

-enge -nge third dual masculine ‘them’

-eme -me third dual feminine ‘them’

-epe -pe third plural ‘them’

Set 1

(22) esi-o ‘hold him’ hold-3

esi-ene ‘hold her’ hold-3f

esi-enge ‘hold them two masculine’ hold-3md

esi-eme ‘hold them two feminine’ hold-3fd

esi-epe ‘hold them’

hold-3p

(23) ku kulta-wo7 ‘We arouse him.’

we arouse-3m

le kulta-ene ‘He arouses her.’

he arouse-3f

ne kulta-enge ‘She arouses them two masculine.’

we arouse-3md

ku kulta-eme ‘We arouse them two feminine.’

we arouse-3fd

ku kulta-epe ‘We arouse them.’

we arouse-3p

Set 2

(24) etesi-Ø ‘hit him’ hit-3m

etesi-ne ‘hit her’

hit-3f

etesi-nge ‘hit them two masculine’ hit-3md

etesi-me ‘hit them two feminine’ hit-3fd

etesi-pe ‘hit them’

hit-3p

The distinction between the-oand-woin set 1 is phonological. The-oonly occurs following the high front vowel,8i, and-wooccurs in all other environments. A few words that end inican actually take ei-ther form. For some speakers the final vowel is lax, and lax vowels match with the-wo. In all cases a high front lax vowel when followed by a morpheme beginning with either auorwwill harmonize and become backed. This explains the change in the root of (25b) fromkanitokano. For more information on this phenomena see Staley (1990).

7The initialkis part of the root and not a first-person singular prefix as shown by the first-person plural lexical Agent. If this

was a case of agreement then the prefix would need to bew-orm-.

(25) a. kani-o b. kano-wo

help-3m help-3m

Help him. Help him.

The preceding examples have been of prototypical transitive events with Agents and Patients. Not all verbs in Olo mark the Patient as an object by using a suffix. Verbs in Olo that have three inherent se-mantic roles do not mark the Patient on the verb; rather they mark the Beneficiary/Recipient with an object suffix. In (26) the third-person feminine suffix corresponds toWamnei‘a woman’s name’ and not the Patient,ila‘knife’, a masculine noun.

(26) a. ki wat-ene Wamnei ila le-iki b. le wat-ene

I give-3f Wamnei knife m-1s he give-3f

I gave Wamnei my knife. He gave her something.

2.3.2.2 Nouns

Nouns in Olo are distinguished generally for both number and gender (Staley 1994a, 1994b). Olo has a wide variety of number allomorphy. A. McGregor (1983) lists twenty-one subclasses for the Lumi dialect. Analysis is still going on in the Somoro dialect, but there are over fifty different subclasses of nouns in that dialect of Olo, solely based on the allomorphy of singular and plural markings. The two genders are masculine and feminine. The gender and number distinctions are keys in disambiguating third-person referents in narrative texts. Syntactically, nouns function as arguments of the predication, as the head of the noun phrase, and as predicate nominals (Staley 1994b) .

Number

The topic of number affixation on nouns in Olo is both fascinating and complex. It is in general out-side the scope of this work; however, this section details some of the different morphemes used to dis-tinguish singular from plural. The largest single class of number marking on nouns in the Somoro dialect is by zero. This is in part caused by a loss ofsin the final position. It did not affect all words, but did cause the loss of the-splural marker attested to in the Lumi dialect (27). When there is no distinc-tion in number marked on the noun, the adjectives or pronominal affixes on the verb will provide the indication of the number.

(27) a. pilpi pilpi-s (Lumi dialect)

drum.call.sign drum.call.sign-PL

b. pilpi pilpi (Somoro dialect)

drum.call.sign drum.call.signs

Olo uses a variety of suffixes as a plural morpheme. The most common suffix is-elem. It is added to the root replacing the final vowel (28).

(28) fairingo fairing-elem millipede millipede-PL

Another group that uses a simple ending is the final-mfor plural (28).

(29) mingi mingi-m

ear ear-PL

(30) a. wase-ne wase-m wild.boar-SG wild.boar-PL

b. epe-n epe-m

male.animal-SG male.animal-PL

Contrasting with the-mplural marker, some classes use an-mfor a singular morpheme and use dif-ferent plural markers depending on the class, either-peor-s.

(31) a. pa-m pa-pe

wound-SG wound-PL

b. nu-m nu-s

a.seasoning-SG seasoning-PL

Most kinship terms are pluralized by adding a single suffix-re(32a). Kin terms used to designate someone else’s kin have a suffix-teiadded to them. In the plural the-teisuffix is dropped (32b).

(32) a. wau wau-re

grandmother grandmother-PL

b. wau-tei wau-re

someone else’s grandmother grandmother-PL

One word in Olo forms its plural by adding ano-as a prefix.

(33) a. flam o-flam

central.rib.in.a.sago.mid.leaf PL-central.rib.in.sago.mid.leaves

Besides the normal methods of affixation, Olo also uses reduplication (34), and consonant alterna-tion (35).

(34) a. soni soni-ni

shadow shadow-PL

b. rolsi rolsi-si

new.shoot new.shoot-PL

(35) a. eti esi

hand hands

b. etingi esingu

rivulet rivulets

The final type of number affixation involves vowel alternation. This involves two shifts, vowel height (36) and front versus back (37).

(36) mere meri

betel.nut betel.nuts

(37) a. fine funo

b. uno ine

tree.branch tree.branches

These shifts can be combined so there is both a shift in vowel height and a flipping from front to back or back to front.

(38) a. naru nare

bird.wing bird.wings

b. pale palu

liver livers

c. wilpango wilpangi

skull skulls

The vowel shifts can be combined with a suffix as well.

(39) opili opuluwongou

part.of.a.bread.fruit.tree parts.of.a.bread.fruit.tree

Besides the many different regular ways to mark number on Olo nouns, there are also many suppletive forms such as (40).

(40) morou siye

wild.animal wild.animals

Noun gender

Gender is not marked on the noun itself, but is shown by other means: the numeral form used when counting the items denoted by the noun, the possessive pronoun, agreement on some adjectives, and the coreferential affixes on the verbs (41).

(41) a. metine ili moto ine

man big.m woman big.f

a big man a big woman

b. mete winges nimou-re wiem

men two.m woman-PL two.f

two men two women

c. metine l-e moto n-e

man 3m-go woman 3f-go

A man goes. A woman goes.

Any noun denoting something which has a sex (humans, spirits, animals) will have the same gender as sex. Kinship terms can be ambiguous for gender (Staley 1994b). Nouns which denote items which have no sex have “inherent” gender. A rule of thumb is that large items are masculine and small items are feminine.

(42) ki k-alei wapuno ki k-anei kofi

I 1s-eat.3m taro I 1s-eat.3f coffee

Nouns with masculine gender are more common than those with feminine gender. When two items are grouped together and they have different gender, the feminine gender is used for agreement purposes.

(43) metine l-ire moto roum m-e

man 3m-with wife they.fd 3fd-go

A man and his wife, they go.

Names

Among the Olo-speaking people names are of three types: traditional names, Christian names, and descriptive names. The traditional names are often thought of as the “real” name. The child is named after someone and normally given that person’s traditional name. The Christian name normally comes out of a name book. Children also take their father’s name for a last name, and wives take their hus-band’s name. The descriptive name is given by others to a person. These often sound cruel or pejora-tive to western ears, but are not meant that way. Some of these names are:Mingim olpe‘Bad ears (deaf)’ andUrou oli‘Bad leg’. One of the reasons for giving these names is name taboos. People cannot say the “real” name of certain of their in-laws. This allows them to refer to the person by “name” without breaking the custom.

2.3.2.3 Adjectives

Adjectives modify nouns. Historically adjectives in Olo are derived from both nouns and verbs (Staley 1994a). This means that some adjectives in Olo share characteristics with nouns and others with verbs. Those that come from nouns agree with the head noun in number, using a plural marker, as in (44).

(44) a. ki k-alei tifa funi b. ki k-aplei tifa funi-mpe

I 1s-eat.3m banana ripe I 1s-eat.3p banana ripe-PL

I eat a ripe banana. I eat ripe bananas.

Those that come from verbs agree not only in number, but also in gender for the singular and dual forms as in (45) and (46).

(45) a. ki k-ulu-wo ninge kumpu b. ki k-ulu-wenge eple kumpu-nge

I 1s-see-3m son small I 1s-see-3md children small-md

I see a small boy. I see two small boys.

c. ki k-ulu-ene ningio kumpu-ne d. ki k-ulu-eme eple kumpu-me

I 1s-see-3f daughter small-f I 1s-see-3fd children small-fd

I see a small girl. I see two small girls.

e. ki k-ulu-wepe eple kumpu-pe

I 1s-see-3p children small-PL I see small children.

(46) a. ki ili b. ku lingi

I big.m we big.md

I am big. We are big.

male speaker male speaker

about 2 men

c. ki ine d. ku limi e. ku lipi

I big.f we big.fd we big.p

I am big. We are big. We are big.

female speaker female speaker

about 2 women

2.3.2.4 Numerals

Olo has three basic numerals, one, two, and five. All other numerals are built as additives of this base system. The largest of the three forms is given first, then the next largest, and finally the smallest. The numbers are added together. So three is rendered as ‘two one’. The numerals for one and two differ depending on the gender of the noun counted. Table 2.7 gives the numerals in Olo from one to ten, for both the masculine and feminine genders.

Table 2.7. Olo numerals from 1 to 10

Numeral Masculine Feminine

1 niliye ninpiye

2 winges/twinges wiem

3 winges niliye wiem ninpiye

4 winges winges wiem wiem

5 eti plen eti plen (hand side)

6 eti plen eti plen ninpiye

7 eti plen winges eti plen wiem

8 eti plen winges niliye eti plen wiem ninpiye

9 eti plen winges winges eti plen wiem wiem

10 eti plen eti plen eti plen eti plen

many wuru

The number system can be extended to include feet. I have heardeti plen eti plen uro plen uro plen ‘hand side, hand side, foot side, foot side’ for 20. This is very unusual. In many areas the numbering system above 2 or 3 has fallen out of use in favor of Tok Pisin numbers. When an Olo speaker counts on his fingers, he uses the reverse process to mark a counted number. Five fingers spread wide is not 5, but 0. As something is counted one finger is clasped into the palm. A fist means 5.

2.3.2.5 Free Pronouns

Table 2.8. Olo free pronouns

ki first-person singular ‘I’

ku first-person plural ‘we

ye second-person singular ‘you’

ise second-person plural ‘you’

le third-person masculine singular ‘he’

te third-person masculine dual ‘they two males’

ne third-person feminine singular ‘she’

me third-person feminine dual ‘they two females’

pe third-person plural ‘they’

Besides these full pronouns there are two other dual pronouns,rounge‘two males’ androum‘two fe-males’. These do not provide person distinctions, but only number and gender information. These can be used to make number and gender distinctions if they are needed, as in (47).

(47) a. ku rounge w-e

we md 1d-go

We two (m) go.

b. ise roum y-au

you.PL two.fd 2p-come You two (f) come.

The free dual pronouns,te‘they two masculine’ andme‘they two feminine’, are often combined with rounge‘masculine dual’ androum‘feminine dual’. When they are combined the pronoun which has the person information comes first. No meaning difference has been detected, and referentially they are identical. Examples are given in (48).

(48) a. te rounge t-a te t-a

3md two.m 3md-die 3md 3md-die

They two m die. They two m die.

b. me roum m-a me m-a

3fd two.f 3fd-die 3fd 3fd-die

They two f die. They two f die.

A chart is given in table 2.9 showing the pronominal distinctions.

Table 2.9. Olo pronouns by person and number

singular dual plural

first person masculine ki ku (rounge) ku

feminine ku (roum)

second person masculine ye ise (rounge) ise

feminine ise (roum)

third person masculine le te (rounge) pe

feminine ne me (roum)

topic is not coreferential with the subject of the first clause in the chain. In (49), from the text ‘Amerika’, the chain topic isku, the first-person plural pronoun. In the text, this refers to the people of Sipote Village circa 1944. The subject of the first clause is shown on the verb asp, the third-person plu-ral. In the text this includes some of the people of Sipote Village, but not the speaker. The subject of the verb is a subset of the free pronoun. The combination of the two gives a form of first-person plural, ex-cluding the speaker. The speaker is exex-cluding himself since he did not actually participate in the event.

(49) ku p-uluw-epe m-antutu m-ire fla-ye

we 3p-see-3p 1p-run.CNT 1p-with scattering-EMP

Some of us, but not me, saw them, and we ran really scattering about.

The same type of exclusion can be achieved with the second person. In response to hearing (49), the question in (50) can be asked.

(50) ise p-uluw-epe lom

we 3p-see-3p YNQ

Did some of you see them?

A construction of this type allows the speaker to differentiate what he personally witnessed versus what occurred around him.

Genitive pronouns

Olo also has an unusual genitive pronoun system. It is formed by using a pronoun which agrees with the gender and number of the possessed item (which is also the head noun in the noun phrase) fol-lowed by a pronoun which agrees with the person, number, and gender of the possessor. The two pro-nouns are combined into a single word. These propro-nouns are very similar to the free pronoun set. Simple examples are given in (51)–(53) with these pronouns in italics.

(51) ila le-ne knife m-3f her knife

(52) ki k-ulu-wo ninge le-iki

I 1s-see-3m son m-1s

I see my son.

(53) ki k-ulu-wenge eple te-ne

I 1s-see-3md children md-3f I see her two sons.

The forms of the possessed pronoun in the feminine and plural are identical, (54).

(54) a. ki k-ulu-ene ningio pe-iki

I 1s-see-3m daughter f-1s

I see my daughter.

b. ki k-ulu-wepe eple pe-iki

I 1s-see-3p children PL-1s

I see my children.

(55) winem le-iki winem lel-pe winango pel-nge

house m-1s house m-3p houses PL-3md

my house their house the two of their m houses

Finally, if one of the possessed markers is followed byuku‘our’ theein the possessed form assimi-lates to a backed position becoming ano. Sole+ukubecomeslouku, as in (56).

(56) winem lo-uku

house m-1p

our house

The full paradigm for the genitive pronouns is given in table 2.10. The first column is the form for the possessed marker. The second column is the possessor marker. The possessor has forms for first, second, and third person, while the possessed has only third person.

Table 2.10. Olo genitive pronouns

possessed possessor

iki first-person singular ‘my’

uku first-person plural ‘our’

iye second-person singular ‘your’

ise second-person plural ‘your’

le / le singular masculine le third-person singular masculine ‘his’ pe / pel singular feminine ne third-person singular feminine ‘her’

te / tel dual masculine nge third-person dual masculine ‘their’

me / mel dual feminine me third-person dual feminine ‘their’

pe / pel plural pe third-person plural ‘their’

Reflexive pronouns

Olo forms reflexive pronouns based on the free pronoun set and one of three variations of-otei‘self’. The complete set is given in table 2.11.

Table 2.11. Olo reflexive pronouns

kutei first-person singular reflexive ‘myself’ kutou first-person plural reflexive ‘ourselves’ yotei second-person singular reflexive ‘yourself’ isotei second-person plural reflexive ‘yourselves’ lotei third-person masculine singular reflexive ‘himself’

totei third-person masculine dual reflexive ‘themselves, two males’ notei third-person feminine singular reflexive ‘herself’

motei third-person feminine dual reflexive ‘themselves, two females’

potei third-person plural reflexive ‘themselves’

(57) le l-eilu l-otei l-asi era he 3m-cut 3m-self 3m-with.CK rocks He cut himself with rocks.

*He cut himself on the rocks accidentally.

The intent of the unacceptable translation of (57) “He cut himself on the rocks” can only be achieved by casting the instrument as the Agent, making it the primary cause. Once the instrument is cast as the Agent there is no longer any reflexive.

(58) era p-alowi metine

rocks 3p-cut.3m man

The rocks cut him. /He cut himself on the rocks.

A further complication in the picture of reflexives is that these same morphological forms can be used in a similar semantic, but nonreflexive, sense. The central semantic idea is one of exclusivity. In (57) he cut only himself, not anyone else. In (59) the “reflexive” pronoun limits the subject to exclu-sively the third-person masculine referent.

(59) l-otei l-au 3m-self 3m-come

He himself came, he did not bring anyone or thing with him.

Reciprocal pronouns

Olo marks reciprocal action by using a combination of three devices. First, there is no patient affix on the verb. Second, the root form of the verb is the same as when the verb is inflected for a first or second-person objects. And finally, the lexical object position in the clause is filled by the properly in-flected form ofnele‘other.m’. Since a reciprocal must involve two or more participants, the form ofnele must be either dual or plural. An example of the reflexive is given in (60).

(60) a. pe p-alpo metine

they 3p-shoot.3m man

They shoot the man.

b. pe p-eipo-iki they 3p-shoot-1s They shoot me.

c. pe p-eipo nemple

they 3p-shoot other.PL They shoot each other.

2.3.2.6 Demonstratives

(61) wa-iki ila give-1s knife

Give me the knife. (the knife is visible) Give me a knife. (no knife is visible)

If more than one item is visible, a request for a particular item must be distinguished from just a gen-eral request for any item of the type. One of the ways to do this is by its position in relation to the speaker using a demonstrative.

(62) a. wa-iki ila l-epe

give-1s knife m-this

Give me this knife.

b. wa-iki ila l-iye

give-1s knife m-that

Give me that knife.

The demonstratives take an initial prefix which agrees with the number and gender of the head noun. The prefix is identical to the third-person subject prefix. The demonstrative occurs in the final NP position. Examples of the demonstratives are given in (63).

(63) a. metine l-epei metine l-epe metine l-iye

man m-this.close man m-this man m-that

this man close enough to touch this man that man

b. moto n-epei pele-m p-epe nafle-pe p-iye

woman f-this.close dog-PL PL-this bird-PL PL-that

this woman close enough to touch these dogs those birds

Besides functioning as simple demonstratives, these morphemes also are used as locatives. Essen-tially they combinethisandthatwithhereandthere, respectively. Examples of this usage are given in (64).

(64) Ø-au l-epei le l-au l-epe ye Ø-e p-iye

2s-come m-here.close he 3m-come m-here you.SG 2s-go m-there

Come right here. He came here. You go over there.

Also included within this group is the spatial question forminei‘where’. It is distributed the same as the demonstratives marking spatial location.

(65) Ø-e l-inei Ø-e p-inei

2s-go m-where 2s-go PL-where

What place are you going to? What places are you going to?

Where are you going? Where all are you going?

Table 2.12. Olo demonstratives

prefix gender/number demonstrative

l- m -epei near

t- md -epe mid

n- f -iye distant

m- fd -inei spatial question

p- pl

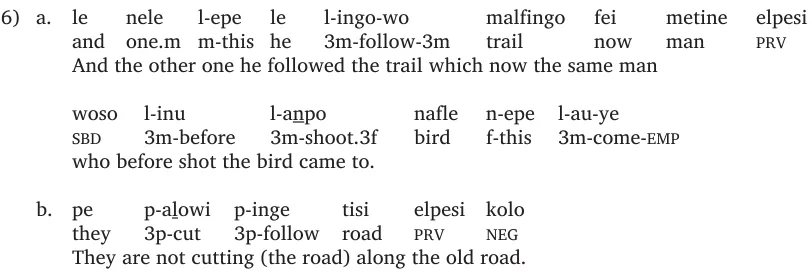

Previous referent

Olo has a special modifier that is used to specify a previous referent,elpesi‘previous’. The word is used to refer to participants in the discourse who recur, but for whom the listener may not be able to make an immediate connection, or might think a new referent is being introduced. The word is also used as a general adjective for certain previously built items. It does not occur often in either stories or conversation. Examples of both uses are given in (66a) and (66b).

(66) a. le nele l-epe le l-ingo-wo malfingo fei metine elpesi

and one.m m-this he 3m-follow-3m trail now man PRV

And the other one he followed the trail which now the same man

woso l-inu l-anpo nafle n-epe l-au-ye

SBD 3m-before 3m-shoot.3f bird f-this 3m-come-EMP who before shot the bird came to.

b. pe p-alowi p-inge tisi elpesi kolo

they 3p-cut 3p-follow road PRV NEG

They are not cutting (the road) along the old road.

2.3.2.7 Adverbs

Olo has a few adverbs. Included among those are words which describe the speed or manner of the event. Examples arefrou ‘quickly’ andmalye‘slow, easy, without force’. Adverbs occur immediately before the verb or immediately following it. While this class is called adverbs, it needs to be clearly stated that while they have some characteristics in common with English adverbs, they cannot be thought of as identical.

(67) ye telpalo Ø-untuluw-epe ara pe-iki

you.SG carefully 2s-look.after-3p money PL-1s You carefully looked after my money.

2.3.2.8 Prepositions and subordinators

There are two prepositions in Olo:ite‘of’ anditiassociated ‘with’. The first-iteis used for kinship re-lations (68a), ownership (68b), and depiction (68c). The form has two possible prefixes,l- ‘third-per-son masculine’ andp-‘non-masculine-singular’.

(68) a. wau p-ite Kowi

grandmother nms-of Kowi

b. tom l-ite Marieta string.bag 3m-of Marieta the string bag of Marieta

c. ki k-ini-epe il p-ite lulem le-iki

I 1s-tell-3p talk nms-of nephew 3m-1s

I tell the story of my nephew.

The second preposition is used for material composition, and associated use.

(69) a. pora l-iti wom

basket 3m-ASS coconut basket made from coconut (fronds)

b. lom p-iti liom

fence nms-ASS garden the fence for the garden.

The same morpheme is also used to introduce subordinate clauses. If this subordinator is used it means a habitual characteristic.

(70) mete p-iti p-eila p-otei

men nms-ASS 3p-lift 3p-self men who lift themselves

men who praise themselves

The other subordinator,wuso, does not have the habitual sense, but is used for attributions, or iden-tifications with single events.

(71) a. mete wuso lipi lepe p-e

men who big these 3p-go

The men who were big go.

b. metine wuso l-esi-ene nafle n-epe l-au

man who 3m-held/flew-3f bird/plane f-this 3m-come

The man who flew this plane came.

When a superlativeoliis suffixed ontowusoto formwusoli, the clause it introduces becomes the rea-son of a rearea-son/result pair.

(72) ki tur-iki, wusoli ki k-ulu-wo tutu.

I afraid-1s because I 1s-see-3m snake

I was afraid because I saw a snake.

2.3.2.9 Conjunctions and discourse particles

Olo has two associative conjunctions, -ire ‘with’ and -asi ‘with’. They are used to associate two groups. The conjunction-asihas a tighter link than-ireas is shown in (73). Both words take the same prefixes as verbs, andirecan take the second verbal suffix set (cf. table 2.6.).

(73) a. le l-alei tipe l-asi fes

he 3m-eat.3m water 3m-with feces

b. le l-alei luom l-ire nimpu

he 3m-eat.3m water 3m-with gnetum.leaves.

He ate dried sago and/with gnetum leaves.

The conjunction-ireis also used for accompaniment and instrument, although the latter use is fairly rare. It does not occur in the text body used in this work.

(74) a. metine l-ire moto roum m-e

man 3m-with wife they.fd fd-go

The man with his wife, they went.

b. ki k-elele nimpe k-ire tomiyo I 1s-fell tree 1s-with ax I fell a tree with an ax.

Olo has a two groups of discourse markers. They are used to link two or more sentences into larger groups. The discourse markers are given in table 2.13.

Table 2.13. Olo discourse linker

sequencers le sequence

so close link sequence

lo loose sequence

wo orde