Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 17 January 2016, At: 23:48

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Indonesian politics in 2013: the emergence of new

leadership?

Dave McRae

To cite this article: Dave McRae (2013) Indonesian politics in 2013: the emergence of new leadership?, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 49:3, 289-304, DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2013.850629

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2013.850629

Published online: 05 Dec 2013.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 3965

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/13/030289-16 © 2013 Lowy Institute for http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2013.850629 International Policy

INDONESIAN POLITICS IN 2013:

THE EMERGENCE OF NEW LEADERSHIP?

Dave McRae*

Lowy Institute for International Policy, Sydney

The rise of Joko Widodo (Jokowi) from small-town mayor to presidential frontrun-ner asks again whether new, alternative leaders could enter Indonesian politics in the 2014 elections. This article surveys Jokowi’s impact on Indonesian politics over the past 12 months, and examines whether his election as Jakarta governor, and his evident popularity, has opened the way for alternative candidates at local level, or if it has changed parties’ calculations for the presidential election. The article con-cludes by considering whether a new leader could tackle some of the entrenched defects of democracy in Indonesia, given that he or she may have only minority support in the parliament. The article focuses in particular on corrupt law enforce-ment, the military and the rule of law, and violent religious intolerance.

Keywords: elections, democracy, alternative candidates, corruption, religious

intoler-ance, military reform

INTRODUCTION

In 2013, as next year’s legislative and presidential elections draw near, there has been a dramatic change of tone in the discussion of Indonesian politics. For some years, expert analysis of Indonesian politics has focused on stagnant reform and democratic regression, as efforts to address the problems of democracy in Indo-nesia have slowed markedly, while conservatives have attempted to wind back certain reforms. This focus has shifted conspicuously over the past 12 months with the election of Joko Widodo, ubiquitously known as Jokowi, to the position of Jakarta governor. Before Jokowi’s election and subsequent rise to presiden-tial frontrunner, widespread voter disillusionment and dropping voter turnouts stood as evidence of the defects of Indonesian democracy. A new optimism would now cast this disillusionment as political capital for Jokowi or a like-minded rival candidate to win the presidency next year.

Asked in mid-2013 about whether and why the 2014 elections are important, Indonesian interlocutors’ answers centred on change. Among their responses:

the elections could be the first time since reformasi that there will be a change of generation in Indonesian politics, and with an alternative candidate there would

* I would like to thank Ed Aspinall, Greg Fealy, Peter McCawley, Ross McLeod and Mar-cus Mietzner for their insightful feedback and helpful advice. Thanks also to Philips Ver-monte for his role as discussant at the 2013 Indonesia Update conference.

be an excellent chance of change. A civil-society figure imagined new access to decision-makers under a new government.1

But will this optimism be fleeting? How great an impact will Jokowi’s rise have on Indonesian politics leading into next year’s elections? Will he even be able to run as a presidential candidate? This article discusses these questions, surveys the prospects for a changing of the guard and considers whether a new leader could tackle some of the entrenched defects of democracy in Indonesia.

STAGNATION

The conclusion that democratic reform in Indonesia has stalled, stagnated or even regressed has become pervasive, including in recent political updates in this journal.2 The reasons are numerous and familiar. Most of the central reforms to

establish a democratic order in Indonesia were concluded during the first six to seven years of post-Soeharto rule, circa 2005 (Mietzner 2012). Since then, far fewer pieces of reformist legislation have been passed. In fact, under democratic rule the Indonesian legislature (Dewan Perwakilan Rakyat, DPR) has passed only around 30 laws on average per year,3 many of which have been budgetary bills or bills

to create new districts and provinces. Some recent legislation has also been criti-cised as regressive, such as a new mass-organisations law enacted in 2013. Civil-society groups have expressed their concern that this law reactivates Soeharto-era controls on societal organisations, which had not been enforced under democratic rule (although they had never been repealed) (Wilson and Nugroho 2012; Human Rights Watch, 17/7/2013).4 A government draft of legislation to end the direct

election of district heads would also be a regressive step if enacted; returning to indirect elections would remove the direct accountability of local leaders to vot-ers.

Another feature of the stagnation has been attempts to weaken impressive new institutions, in particular the Anti-Corruption Commission (Komisi Pemberan-tasan Korupsi, KPK). The DPR also weakened Indonesia’s corruption court, in 2009, when it legislated to situate anti-corruption courts in all provincial capi-tals rather than maintain a central anti-corruption court in Jakarta.5 This change

required the mass recruitment of judges, spurring doubts over their quality (Butt 2011, 2013). Five corruption-court judges have been convicted or made suspects in bribery cases during the past year, and anti-corruption campaigners continue

1 Author’s interviews, Jakarta, June–July 2013.

2 See, for example, Hamid (2012), Fealy (2011), Tomsa (2010), but also Mietzner (2012) 3 Kawamura (2010), and the list of legislation at <http://www.setneg.go.id>.

4 Islamic organisation Muhammadiyah requested a judicial review of 25 articles of the law in October 2013 (Viva News, 10/10/2013).

5 The DPR took this step in response to a decision in 2006 by the Constitutional Court, which ruled that the arrangement of some corruption cases being heard at the corruption court and others in the regular courts constituted an inequality before the law and gave the DPR three years to remediate it (Butt 2013: 19).

to complain of the short sentences and higher acquittal rate – albeit up from zero – since the court was decentralised.6

Additionally, political parties have established barriers to new candidates seek-ing to enter politics. Parties have lost some control of exactly who gets into the DPR, because of changes to the electoral system prior to the 2009 elections which allocated seats based on the number of votes received, rather than on who is high-est on a party’s candidate list. These alterations have opened up the political sys-tem to a degree, as has requiring one of every three candidates to be female. But the cost of running for office remains prohibitive for many Indonesians: most DPR members whom I interviewed estimated that they will spend around $100,000 on their campaign for re-election in 2014 (or, in one case, considerably more). Gain-ing a spot on a party list is an additional expense (Hadiz 2011: 120).

Nor has allowing independent candidates to contest elections for local heads of government significantly diversified the range of candidates winning execu-tive positions in the regions. Gaining a party nomination often involves a steep financial cost and therefore excludes candidates who are unable to pay. Non-party candidates also face onerous and costly requirements to contest elections, because they must gather signatures from 3.0% to 6.5% of voters.7 Only a small proportion

of independent candidates win elections, with the obstacles to success including their lack of political parties’ campaign structures.8

For the presidential election, the Indonesian constitution grants authority only to political parties to nominate candidates, and the parties have set a threshold to do so of 20% of seats or 25% of valid votes in the preceding general election. In 2009, this produced a choice between three establishment candidates: the admit-tedly popular incumbent president, Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono; the incumbent vice-president, Jusuf Kalla; and former president Megawati Sukarnoputri.

For much of the past year, this restrictive nomination process looked as though it would produce an uninspiring, even anti-democratic set of candidates for 2014. An election last year between the top four parties’ candidates would most likely have been a contest between Megawati, already defeated twice in direct presi-dential elections; Aburizal Bakrie, a business tycoon; Prabowo Subianto, a former general dismissed from the military after the fall of Soeharto, who at the time was his father-in-law; and a yet-to-be-determined Democratic Party (Partai Demokrat, PD) successor to Yudhoyono. Polling suggested that Prabowo would have won.

This situation – a stalled reform process, with the real prospect of an authoritarian-era figure as Indonesia’s next president – produced widespread disillusionment. Kompas, Indonesia’s largest newspaper, ran frequent articles on leadership and the need for new candidates, which reflected the mood at the time. For its part, the prominent polling institute Lembaga Survei Indonesia (2012) observed early last year that none of the established presidential candidates was a ‘leader of integrity with empathy for the people’, and mused whether there was really no other candidate who could meet such criteria.

6 See Indonesia Corruption Watch (2013).

7 On the middlemen that this requirement has created, see Buehler (2013).

8 Supriyanto (Suara Merdeka, 25/7/2011) found that only eight independent candidates succeeded in the hundreds of elections in the first two years in which they were able to participate.

THE JOKOWI EFFECT: FROM SMALL-TOWN MAYOR TO PRESIDENTIAL FRONTRUNNER

The mood of disillusionment has changed, though, as Joko Widodo, or Jokowi, has moved from small-town mayor to presidential frontrunner. Jokowi’s elec-tion last September as governor of Jakarta, and his subsequent rise to the top of the presidential-election opinion polls, threatens to open the way for himself and other alternative candidates to contest and win elections. This section examines the evidence for such a ‘Jokowi effect’.

Calls for ‘new’ or ‘alternative’ candidates are common in Indonesia, yet these terms are difficult to define. In this article, they do not refer to independent or anti-party candidates, much as parties have established obstacles to the entry of reform-minded individuals into politics. Instead, new or alternative candidates are those unlikely to have held a senior position in politics or government dur-ing the authoritarian era, or to have run for or held office at the level of politics that they are contesting, or to have a background that may raise doubts over their commitment to democratic good governance. They are often able to make their case for office by drawing on their success in a previous position of leadership or responsibility.

Jokowi’s win in the Jakarta elections has been widely covered but is worth revisiting.9 A furniture businessman by trade, Jokowi, now 52, entered politics in

2005, as a successful Indonesian Democratic Party of Struggle (Partai Demokrasi Indonesia – Perjuangan, PDI–P) candidate for mayor of Solo, a city of around 550,000 people in Central Java. Famed for, among other things, his consultative style in relocating street vendors and squatters away from streets and public spaces (McLeod 2008: 202–3; Phelps et al. 2013), Jokowi won a second term in 2010, receiving 90% of the vote. From there he entered the Jakarta gubernatorial election with running mate Basuki Tjahaja Purnama (known as Ahok), a Chinese Indonesian national parliamentarian, and the support of two parties, Megawati’s PDI–P and Prabowo’s Greater Indonesia Movement (Gerindra) party. Running on a reform-image platform and presenting themselves as men of the people, Jokowi and Ahok beat incumbent Fauzi Bowo in two rounds. One editor put it as it being the first time in a long time that people have seen themselves reflected in a politi-cian.10 In the process, the pair saw off an identity-based campaign warning voters

against choosing the Chinese Indonesian Protestant Ahok.

When Jokowi won, in September 2012, most commentators outlined various benefits that Gerindra frontman Prabowo Subianto would gain from Jokowi’s victory. First, in imagining Megawati and Prabowo to be rivals for the presi-dency, various authors noted that Prabowo remained well ahead of Megawati in a recent opinion poll. A single poll of course does little to illustrate the effect of the Jakarta election, yet its result led PDI–P figures to comment that they would not be attracted to a future coalition with Gerindra (Kompas, 26/9/2012). Second, observers suggested that Prabowo’s support for Ahok would help him win sup-port among Chinese Indonesians, who had been dismayed by Prabowo’s apparent links to the 1998 Jakarta riots. These riots targeted Chinese Indonesian property, and rioters raped an unspecified but significant number of Chinese Indonesian

9 For a detailed discussion of the 2012 Jakarta elections, see Hamid (2012). 10 Author’s interview with Nezar Patria, July 2013.

women (Coomaraswamy 1999: 15–16; Fealy 2013: 107). Last, it was presumed that Prabowo’s support for Jokowi and Ahok could help him clean up his image more generally, and distance himself further from his poor human-rights record and his status as a Soeharto-era establishment figure. In any case, surveys suggest that many members of the voting public are not aware of Prabowo’s past (Tempo, 24/9/2012).

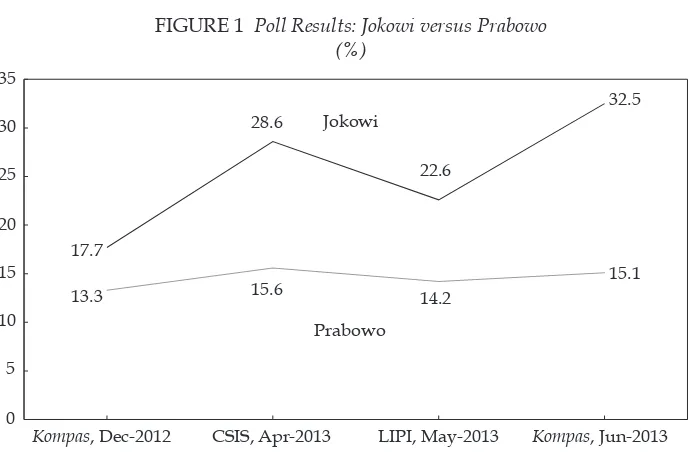

Far from riding to the presidency on Jokowi’s popularity, Prabowo has sunk to second in the polls, behind Jokowi himself. Various surveys from reputable poll-ing agencies show Jokowi comfortably ahead of Prabowo, regardless of whether respondents were asked to name their preferred presidential candidate or to choose from a restricted field of candidates. Kompas polling suggests that Jokowi has increased his advantage over Prabowo since December 2012 (figure 1)

(Kom-pas, 26/8/2013).

Why are Jokowi and Prabowo the frontrunners? Within Indonesia, they are seen as being the antitheses of current president Yudhoyono, considered by many domestically to be stiff, cautious and indecisive. Prabowo, in contrast, is per-ceived as a firm leader, Jokowi as a problem-solver who interacts directly with the people.11

At a party level, PDI–P also appears to have gained more than Gerindra from Jokowi’s victory. PDI–P is certainly more popular than Gerindra – although this was also true before Jokowi was elected, with at least one poll suggesting that the margin would widen further if PDI–P were to name Jokowi as its presidential candidate (CSIS 2013).

PDI–P has also been able to marshal Jokowi to campaign for its gubernatorial candidates in other provinces – almost half of Indonesia’s provinces held

guber-11 Author’s interviews, Jakarta, July 2013.

FIGURE 1 Poll Results: Jokowi versus Prabowo

(%)

17.7

28.6

22.6

32.5

13.3 15.6 14.2

15.1

Kompas, Dec-2012 CSIS, Apr-2013 LIPI, May-2013 Kompas, Jun-2013 0

5 10 15 20 25 30 35

Jokowi

Prabowo

Sources: Kompas, 27/8/2013; CSIS (2013); LIPI (2013).

natorial elections in the 12 months following his victory. Jokowi has campaigned for PDI–P candidates across Java, as well as in North Sumatra and Bali.

It is questionable how strong the Jokowi effect has been in these gubernato-rial elections, either in increasing the number of successful PDI–P candidates or in enabling a new type of candidate to run. The clearest effect was in West Java, where PDI–P paired female national member of parliament Rieke Diah Pitaloka with anti-corruption campaigner Teten Masduki. The pair even used the same distinctive chequered shirts that had been the signature of Jokowi and Ahok’s Jakarta campaign. They did not win, though, in fact gaining a slightly lower pro-portion of the vote than the PDI–P candidate five years earlier (albeit in a larger field). In Central Java, PDI–P shunned its incumbent vice-governor, Rustrining-sih, for Ganjar Pranowo, a young second-term national member of parliament, who swept to victory against the incumbent. Overall, incumbents have domi-nated gubernatorial elections since Jokowi’s success in Jakarta, winning 10 of the next 12 gubernatorial elections. Voters are either not being offered new candidates or not choosing them.

Yet the success of incumbent governors does not mean that there are no prom-ising new leaders emerging at the local level. Tri Rismaharini, for example, elected in 2010 as the female mayor of Surabaya, has gained particular attention (Jakarta

Globe, 23/9/2013). She was named by news magazine Tempo as one of its seven dis-trict heads of the year in 2012; her reputation derives from her urban-regeneration programs and her efforts to reduce levels of prostitution (Tempo, 16/12/2012; Viva

News, 25/10/2012). But in assessing the overall pattern of political leadership, we need to balance such cases against other trends mapped out by political scientist Michael Buehler (2013), of wealthy bureaucrats dominating local elections and of powerful families establishing themselves in local politics. Such elected offi-cials may include individuals committed to improving democratic governance among their ranks, but their success means that most local leaders are drawn from the established elite (Mietzner 2010), whereas the chance of reformists emerging would increase if leaders were drawn from a wider cross-section of the popula-tion. Jokowi’s experience in Solo and Jakarta shows that new leaders can emerge and succeed, but this still appears to be more of an exception than a rule. If evi-dence is limited for a so-called Jokowi effect on local politics, what can we expect to see during the national elections next year?

THE 2014 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS: NEW CANDIDATES?

Jokowi’s rise in the polls has given a new signal to political parties and political elites of whom the public might elect. It also poses questions of whether Jokowi’s evident popularity affects the calculations of other parties or clears the way for alternative candidates to emerge. Yet neither Jokowi’s own party (PDI–P) nor any other has nominated Jokowi as its presidential candidate, and nor has he said definitively that he wants to run.

The 12 parties that will take part in the April 2014 legislative elections have adopted three different strategies for selecting their presidential candidates. First is that of the early movers, the four parties that have already announced their candidates, mostly before Jokowi’s emergence. Of these, only Golkar and Gerin-dra have a realistic chance of securing a nomination, and neither has proposed a democratic reformist. For the other two early movers, Hanura and the National

Mandate Party (Partai Amanat Nasional, PAN), announcing a presidential candi-date looks like a bid for a vice-presidential slot.

Golkar’s candidate is Aburizal Bakrie, the party’s chairperson and key finan-cier. Bakrie is said to have been instrumental in forcing out Sri Mulyani Indrawati as finance minister in 2010, at which point Tomsa (2010: 314) noted that he was ‘widely regarded as a key obstacle to democratic reform in Indonesia’. Bakrie’s great public black mark is the Lapindo mudflow disaster, a blowout in a gas drill-ing operation, part-owned by a Bakrie family company, that submerged a large swathe of East Java under volcanic mud (McMichael 2009). Voters have been con-sistently cold to Bakrie, with his support in single digits. Yet he remains Golkar’s official presidential candidate, and the party’s mid-teens popularity in opinion polls makes it likely that he will be able to run.

Prabowo and his party, Gerindra, have the opposite problem. Prabowo is sec-ond in the polls, but Gerindra’s popularity remains mired in single digits. With Gerindra’s low share of the vote, it is not inconceivable that Prabowo could miss out on a presidential nomination in 2014. He and his supporters certainly seem wary of this eventuality, launching an abortive Constitutional Court challenge to the nomination threshold last year, and failing in their attempt to convince the DPR to lower the threshold (Antara News, 1/10/2012).

The second strategy is that of the wait-and-sees, seven parties who have stated that they will announce their candidates only after the legislative elections. With the exception of PDI–P, these parties’ deferral of their decision suggests that they will receive insufficient votes to be the senior member of a nominating coalition, and that they lack a charismatic figure who has a chance of winning the presidential vote. All of the Islamic parties except for PAN are in this group (and PAN would not look out of place here, either), reflecting their continuing decline. Islamic parties polled roughly 38% of the vote in Indonesia’s first two post-Soeharto elections, but then only 29% in 2009, as outlined by Feillard and Madinier (2011: 223–6). They suggest two reasons for the parties’ declining sup-port: the capture by secular parties of political Islam’s campaign themes, and the weak links between the very large Islamic organisations Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah and the parties that claim to represent them, with these links further weakened by scandals.12

Islamic parties could receive still fewer votes next year; the only party to improve its share in 2009 – the Prosperous Justice Party (Partai Keadilan Sejahtera, PKS) – has been severely damaged by the lurid Beefgate scandal (New York Times, 16/5/2013; Tempo, 10/2/2013; Tempo, 17/2/2013). The scandal concerns PKS’s control of the Ministry of Agriculture, which administers beef-import quotas, with the implication being that PKS has manipulated this process in an effort to build an electoral war chest. Beefgate has seen the PKS president stand trial and has drawn in other senior party figures as witnesses, while filling the papers with tales of bribes, lavish gifts to beautiful women and the seizure of cars from the party’s parking lot. Under the weight of the scandal, the party’s support dropped from 8% in 2009 to less than 3% in mid-2013.

The odd party out among the wait-and-sees is PDI–P. It is the highest-ranked party in opinion polls, and in Jokowi it has the most popular presidential

12 On the role of Nahdlatul Ulama and Muhammadiyah in politics, see also Jung (2008).

candidate – if it chooses to nominate him. PDI–P may win enough votes to be able to nominate a candidate in its own right in 2014, and it will certainly be at least the senior player in a coalition. Despite his popularity with voters, how-ever, Jokowi does not enjoy universal support within PDI–P. Some senior figures would prefer a Megawati–Jokowi ticket, although these figures appear to be los-ing ground within the party.13 Jokowi’s opponents cite his inexperience, arguing

that Megawati has superior qualities as a leader.14 It is hard to escape the

impres-sion, though, that many of Jokowi’s opponents fear that they will lose their posi-tions of influence within the party if it comes under new leadership.

At any rate, the decision is Megawati’s – at PDI–P’s 2010 congress, the party handed her the authority to choose its presidential candidate (Tempo, 15/9/2013). Megawati has opted for Jokowi once before, when she endorsed him as a Jakarta gubernatorial candidate despite her (now deceased) husband Taufik Kiemas wanting PDI–P to support Fauzi Bowo (Kompas, 12/3/2012). Guessing at Mega-wati’s intentions, however, has become akin to reading runes: press reports have noted details such as Jokowi being in the same car as Megawati at various events and making frequent and extended visits to Megawati’s residence (Okezone, 9/6/2013; Detik News, 6/9/2013). Jokowi was also given a prominent role at the party’s national meeting in September 2013, adding to media speculation that he will be PDI–P’s candidate.

Last, we come to Yudhoyono’s PD Party, which finds itself in crisis, despite its nine years as the president’s party. Recent polls put PD’s support at between 7% and 11%, well below its 2009 result of 21% and far from sufficient to nominate a presidential candidate. The slump reflects disquiet with corruption scandals that have consumed prominent PD figures, as well as with Yudhoyono’s performance as president and his failure to groom a successor. PD has responded to its predica-ment by holding an eight-month candidate convention to settle on its presidential contender, which began in mid-September.

Unlike the conventions of political parties in the US, the PD’s convention will not involve a popular vote. Rather, three survey institutes will twice poll the pop-ularity of the 11 candidates – who are all male – after which the party’s High Council, chaired by Yudhoyono, will select the winner. The 11 hopefuls include Yudhoyono’s son-in-law and recently retired general Pramono Edhie Wibowo; trade minister Gita Wirjawan and state enterprises minister Dahlan Iskan, both multimillionaires; and genuine left-field candidates such as former presidential spokesperson Dino Patti Djalal and public intellectual Anies Baswedan.15 Lacking

both cash and a high profile, the latter pair face great obstacles to success. But the convention could foreseeably produce a candidate like Gita Wirjawan or Dahlan Iskan, who would present themselves as reformists in the presidential race.

What, then, might the field of candidates look like after April’s legislative elec-tions? Of the three to four slots available, we may assume that one slot will go to Golkar, which at this stage means to Bakrie, and another to PDI–P, probably to

13 Author’s interviews by email with PDI–P figures, September 2013. 14 Author’s interview with senior PDI–P figure, July 2013.

15 The 11 candidates are Anies Baswedan, Dino Patti Djalal, Endriartono Sutarto, Hayono Isman, Marzuki Alie, Irman Gusman, Gita Wirjawan, Ali Masykur Musa, Dahlan Iskan, Pramono Edhie Wibowo and Sinyo Harry Sarundajang (Kompas, 31/8/2013).

Jokowi. That leaves only one to two free spots, which could be one or both of PD’s candidates, or Prabowo, or, at the very outside, an Islamic-coalition candidate. So it is still possible that Jokowi’s rise may not spur other parties to change their candidates. The PD convention aside, the best that the clutch of other alternative candidates may be able to do will be to run as vice-presidential candidates.

If such a field emerged, Jokowi would have a good chance of winning. His strengths include his skill as a communicator and his strong journalistic appeal, which would negate the media resources of some of his rivals. Moreover, even if he turns out to be a mediocre governor, the time period until the elections is probably too short for this to become evident. His win in Jakarta, where PDI–P has done poorly in elections, shows that he is popular independent of the party, meaning that the risk of PDI–P becoming ensnared in a corruption scandal prior to the elections is less of a threat to him, except that such a scandal might weaken PDI–P’s position in a nominating coalition.

Nor do direct cash transfers look set to be decisive in the 2014 elections. Prior to the 2009 election, the government paid $1.4 billion in direct cash transfers, some of which was to compensate for fuel-price rises, which Mietzner (2009a) argues was central in the electoral success of Yudhoyono’s PD party. This year, the gov-ernment has again given cash transfers to the poor, to offset a fuel-price rise in June 2013 from Rp 4,500 to Rp 6,500. Yet the DPR has approved only roughly half of what was paid five years ago, when adjusted for inflation, and this money will be disbursed over a shorter time period than before (Viva News, 13/6/2013). PDI–P has opposed these transfers, as it did prior to 2009, but although PDI-P fig-ures interviewed by the author were wary of the cash transfers’ potential impact, they appeared confident of their party’s prospects.16

A NEW PRESIDENT, ENTRENCHED OBSTACLES

Having an alternative figure as the frontrunner for president is in itself a big change in Indonesian politics, regardless of the eventual composition of the presidential race. Yet the prospect of a reformist president raises the question of whether a new leader could tackle some of the entrenched problems in the Indo-nesian political system, such as corrupt law enforcement, the incomplete rule of law over the military, and violent religious intolerance.

Corrupt law enforcement

Indonesia’s law-enforcement and judicial institutions are blighted by brazen cor-ruption. There is abundant evidence that corruption is rife in the police and in the prosecutor’s office, and also in the courts.17 Police and prosecutors have shown

little appetite for tackling the problem – leaving the KPK to take on these institu-tions, often with only belated and half-hearted support from the president.18

16 Author’s interviews with PDI–P figures, June–July 2013.

17 For details of law-enforcement and judicial corruption in Indonesia, see Dick and Butt (2013) and Butt and Lindsey (2010). The religious courts (Sumner and Lindsey 2010) and – until the scandal detailed below – the Constitutional Court have generally been considered to be exceptions to this overall pattern.

18 On prior confrontations between the KPK and the police, see Mietzner (2012) and Jans-en (2010).

This year alone, the chief justice of the Constitutional Court has been arrested for bribery; a Supreme Court judge has been dismissed for falsifying a verdict, after it initially appeared he would be allowed to resign (Tempo, 25/11/12;

Kom-pas, 12/12/2012); the national head of traffic police has been convicted of cor-ruption and money laundering; and a former head of the criminal-detective branch has gone to prison for corruption. In addition to these high-level cases, there have been routine revelations of other law-enforcement and judicial corrup-tion scandals. For example, a low-ranking police officer in Papua was arrested in May 2013, after it was discovered that $130 million had passed through his bank account (Kompas, 15/5/2013). In another case, a police officer came to national police headquarters carrying almost $20,000 in cash, which was suspected to be a bribe to gain promotion. He was not charged, and the national police spokesper-son said that it was natural for someone of his rank to have that amount of money (Detik News, 27/6/2013). Subsequently, in July, the KPK apprehended a Supreme Court clerk who was on a motorcycle taxi and carrying roughly $7,000 in cash, also suspected to be a bribe (Detik News, 25/7/2013). These cases contribute to the very negative views within Indonesia of law-enforcement and judicial institu-tions, as captured in surveys of corruption perceptions (for one example, see Dick 2013: 9–10).

In early October, Indonesia was gripped by the arrest of Akil Mochtar, the chief justice of the Constitutional Court, on charges of bribery and money laun-dering. Akil was apprehended at his house, along with a member of parliament from Golkar, a businessman and more than $200,000 in foreign currency (Kompas, 3/10/2013). The corruption commission alleges that the money was a bribe relat-ing to a local electoral dispute in Kalimantan; the commission is also investigatrelat-ing a second district-level electoral dispute, in Banten, handled by Akil, for which it has blacklisted the governor, Ratu Atut Chosiyah, from travelling overseas and arrested her brother for bribery (Tempo, 27/10/2013). Akil’s arrest is noteworthy for three reasons: the Constitutional Court was previously regarded as one of the most important clean institutions formed under democratic rule; the court makes final and binding decisions on Indonesia’s laws; and, because the court hears electoral disputes, a diminution of its standing among the community and political elite poses a potential risk to the orderly conduct of next year’s elections and the acceptance of the results. In response, President Yudhoyono issued emer-gency legislation in mid-September to establish a seven-year grace period before political party members can be appointed to the court; the bill also altered the selection process for Constitutional Court judges, and introduced a new oversight mechanism for the court (Kompas, 18/10/2013). It is unclear whether the DPR will approve or reject this emergency bill.

Prior to Akil’s arrest, the biggest case of the past 12 months was a confrontation between the police and the KPK in October 2012, over the commission’s inves-tigation of Djoko Susilo, the national head of traffic police, for marking up con-tracts to procure driving simulators. When the KPK took up the case, the police tried to block it from seizing documents, sought to take over the investigation and then withdrew 20 seconded detectives from the commission. When Susilo at last submitted to questioning, the police responded by raiding KPK headquarters the same night, aiming to arrest a seconded detective over the shooting death of a criminal suspect years earlier, in 2004. The arrest was averted only when a

group of prominent citizens formed a ‘fence of legs’ in front of the commission, after which Djoko Suyanto, Indonesia’s coordinating minister for political, legal and security affairs, reportedly ordered police to withdraw (Kompas, 6/10/2012). Meanwhile, the KPK’s parliamentary opponents sought to amend the KPK law to weaken the commission’s powers, by requiring it to obtain court permission for wiretaps and by removing its authority to prosecute cases (Kompas, 8/10/2012, 16/10/2012).

Yet the KPK prevailed, when President Yudhoyono stepped in several days later. Having allowed the confrontation between the police and the KPK to develop prior to the aborted raid on KPK headquarters, the president ordered the police to let the KPK investigate Susilo, criticised the timing and manner of the police move against the KPK investigator, and told the DPR to desist (Istana

Negara, 8/10/2012). The KPK pressed on, and Susilo was sentenced to 10 years in prison in September 2013 (Kompas, 3/9/2013). The case thus stood as a victory for the KPK, albeit one that must have reminded the commissioners of their tenuous position when taking on the police.

Another very prominent police corruption case concerned Susno Duadji, a for-mer chief of the national crime investigation agency, who fled when prosecutors came to his house, in April 2013, to take him to prison. Susno had been sentenced in 2011 to three and a half years’ jail for embezzlement and for accepting a bribe during his tenure as West Java police chief (Suara Pembaruan, 3/5/2013). This con-viction followed his being caught, on tape, by the KPK, soliciting a bribe in 2009, which, like the Susilo case after it, triggered an all-out confrontation between the police and the KPK (Jansen 2010). Despite his chequered past, Susno was a reg-istered candidate for the Islamic Crescent Star Party (Partai Bulan Bintang, PBB) for the 2014 elections. When the prosecutors came to his house, Susno refused to cooperate, and instead headed to the police headquarters in West Java to seek protection from Tubagus Anis Angkawijaya, the provincial police chief, who duly granted it. In a national embarrassment, Susno became a celebrity fugitive for nine days and even paused to address the nation on YouTube.19 In the video,

Susno insists that clerical errors in the Supreme Court decision on his case meant that he had not been convicted of a crime, let alone would he need to serve a sentence. The embarrassment for law-enforcement authorities ended only when Susno turned himself in. As he was no longer able to run for parliament, his spot on the PBB ticket went to his daughter (Jakarta Globe, 22/5/2013). Tubagus was also quietly removed a month later, after less than a year in his post (Kompas, 8/6/2013).

Yudhoyono has been reluctant to involve himself in such cases, in what is admittedly a complex and interest-laden area of law-enforcement reform. He set up an anti-legal mafia task force in 2009, but it has faded from sight. To make progress, a new president would need to put more political weight into efforts to clean up law enforcement, by backing the KPK and demanding results from the country’s top law-enforcement appointees. Such moves would tread on influen-tial toes but could only be popular with the voting public.

19 Available at <http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xAbhcmrh1cE>.

The military and the rule of law

Two high-profile attacks in March 2013 showed that the Indonesian military is still willing to engage openly in violence when it believes that its interests have been harmed – and that it demands the right to manage investigations and trials involving military personnel, even if they are clearly guilty of civilian crimes. Such attacks trigger renewed calls to transfer the authority to try these cases to the civilian courts, but that reform stalled in Yudhoyono’s first term (Investor Daily, 14/5/2012; Mietzner 2009b: 311).

In the first attack, around 75 soldiers burnt down a district police station in Ogan Komering Ulu, in South Sumatra, killing a civilian and injuring five police, after a policeman had shot one of their colleagues two months earlier. That police-man was eventually sentenced in a civilian court to 13 years for murder. The twelve soldiers who stood trial in a military court received sentences ranging from a few months to four years. The head of the military court said that these sentences showed that no soldier was above the law.

Then, just two weeks later, soldiers from Kopassus, Indonesia’s special-forces unit, forced their way into the Cebongan prison, in Yogyakarta, and shot dead four prisoners being held for killing a Kopassus member at a nightclub several days earlier. Amid intense public scrutiny the army formed an investigative team to take control of the case from the police. Yet the team’s findings read like a damage-control exercise, or even a justification of the killings, rather than a genu-ine report. The team’s head described the attack as reflecting the strength of the Kopassus soldiers’ esprit de corps and their desire to defend their unit’s honour, and repeatedly referred to the slain men as ‘thugs’.

This approach to the case continued in the military trial, in which the prosecu-tor cited as an ameliorating facprosecu-tor in his sentencing request that ‘not all of the community criticise this act: in particular, the Yogyakarta community feel they have benefited from the accused’s actions’ (Detik News, 31/7/2013), on account of the slain men being thugs. The court handed down custodial sentences of eleven, eight and six years to the three soldiers accused of being the main perpetrators, with the other nine soldiers each receiving sentences of less than two years.

So how did civilian authorities respond to the military’s handling of the attacks in South Sumatra and Cebongan? Yudhoyono commented publicly on both cases, but his statement on Cebongan was decidedly equivocal: he waited two weeks to comment, and then he echoed the military’s justification of the killings, while also making it clear that the perpetrators were to be punished. A new law on the military court remains off the agenda, consistent with scholars’ judgements that Yudhoyono has had little appetite for broader military reform (Mietzner 2009b; Crouch 2010: 177). Honna (2013: 186) sees the current incomplete military reforms as reflecting a grand bargain between civilian and military leaders, in which the military disengages from politics whereas ‘civilian leaders respect [the military’s] institutional autonomy and overlook its lack of accountability’. The military’s institutional autonomy includes a territorial command structure and a diminished but continuing ability to raise off-budget funds (Aspinall 2010). These resources do not mean that the military is in a position to conduct a coup (Crouch 2010: 176–7) – except perhaps in a crisis (Aspinall 2010: 24–5) – but they do make it a powerful adversary for civilian leaders. A new president may be wary of con-fronting a challenge of this magnitude, unless he or she was particularly deter-mined to restart military reform.

Violent religious intolerance

A new president will also face the familiar problem of violent religious intoler-ance (Hamid 2012; Fealy 2011). Over the past 12 months, Yudhoyono has contin-ued the previous trend of ineffective leadership on this issue, whether for fear of the electoral consequences, or because of his shortcomings as a leader, or for other reasons. He has occasionally made firm statements, including bemoaning the failure of security agencies to be impartial in their enforcing of the law, but he has not imposed consequences on state agents who have acted contrary to his directives. In fact, he has allowed Suryadharma Ali, the minister for religion, to champion the cause of intolerance. In July, for example, Suryadharma told Tempo magazine that Syiah Muslims driven from their village in Madura, in East Java, in a violent confrontation in 2012 would need to be ‘enlightened’ before they could return, and that anyone could return as long as their understanding of Islam did not clash with existing understandings (Tempo, 27/7/2013).

Despite these failings of leadership, Yudhoyono travelled to New York in May to receive the World Statesman Award from the Appeal of Conscience Founda-tion, an organisation that aims to promote peace and tolerance and resolve ethnic conflict. This trip became a lightning rod in Indonesia for dissatisfaction with the president’s leadership on this issue.

One encouraging recent development involved Jokowi and his vice-governor, Ahok. One of Jokowi’s early reforms has been to use an open selection process in reappointing Jakarta’s ward and sub-district heads. One of his new appoint-ments, a Christian ward chief in the majority Muslim area of Lenteng Agung, has met with protests on the basis of her religion. Both Jokowi and Ahok have backed the official, with Jokowi saying that officials should be judged only on results. Ahok has been more outspoken, countering a statement from Gamawan Fauzi, the Home Affairs Minister, to the effect that Jokowi should consider replacing the official, by suggesting that the minister should study the constitution (Tempo, 27/9/2013; Kompas, 26/9/2013).

Indonesia has long been short of unequivocal statements on this subject – and the actions to match – and Jokowi and Ahok’s support for the Lenteng Agung ward chief sets a good precedent against which to measure Jokowi’s performance should he be elected president. Countering violent religious intolerance will be a central quality-of-democracy issue for any reformist president.

Political support

The above deficiencies of Indonesia’s democracy are far from an exhaustive list. A survey of the past 12 months could equally have focused on Aceh and Papua, or on the lack of meaningful progress on past human-rights abuses.20 These

prob-lems await the new president, who may have to address them as a novice politi-cian with minority parliamentary support.

All of Indonesia’s democratically elected presidents, Yudhoyono included, have countered their lack of parliamentary support by forming a rainbow coali-tion encompassing most of the large parties in parliament (Diamond 2009; Sher-lock 2009; Tomsa 2010). This has not been effective in Sher-locking in support for the government agenda. Indeed, most observers lamented Yudhoyono’s decision not to form a more narrowly representative cabinet after his decisive win in 2009.

20 On Aceh, see International Crisis Group (2013); on Papua, see IPAC (2013).

A popular mandate would be the main asset of any reformist president. Popu-lar pressure can force action – it has influenced the government’s approach to tackling the aforementioned problems. In indicating the role that public pressure has played in recent years, Mietzner (2012: 219) cites a shift in the role of civil-society activism since 2005 – from pressing for new reforms to defending existing democratic arrangements – as one of the signs of democratic stagnation. A new leader would need to marshal anew civil-society and broader public pressure in favour of his or her policies; rather than seeking the very broad political support of an extensive coalition, a new president may be better off forming a capable cab-inet. At worst, we would see how much can be achieved when a popular leader supported by new entrants to the political system lends his or her political weight to particular causes.

CONCLUSION

This article has attempted to determine what effect Jokowi’s rise has had on Indo-nesian politics ahead of next year’s elections, and whether a new president could tackle some of the entrenched defects of Indonesia’s democracy. There are two reasons to expect Jokowi’s emergence at a national level to have influenced Indo-nesian politics: if his success in Jakarta has signalled that other reformist candi-dates can harness widespread disillusionment as political capital to gain election, and if his leading position in polls ahead of the presidential elections has spurred other political parties to seek new candidates to defeat him should he gain the PDI–P nomination.

At this stage, there is limited evidence for either manifestation of a Jokowi effect. The success of incumbents in the year since Jokowi’s victory suggests that voters in the regions have not been offered or are not choosing a new style of candidate, at least at the gubernatorial level. Nationally, half or more of the field of presiden-tial candidates could be establishment figures such as Bakrie and Prabowo, albeit with their chances of winning diminished.

Nor is it certain precisely what Jokowi’s agenda would be if he were elected. Not having secured his party’s nomination, he has refrained from commenting on national or foreign-policy issues, lest he be seen assuming to be PDI–P’s can-didate. His reticence carries the advantage of enabling the dissatisfied to project their hopes onto him, but over time it is likely to emerge that he does not share all of their views. Yet no matter their level of commitment to reform, Jokowi or another reformist president would face enormous difficulties in trying to restart reforms. Already this has led some pessimists to conclude that next year’s elec-tions will not effect change.

Nevertheless, Jokowi’s emergence and the likelihood that he or another reform-image candidate will win in 2014 have changed discussions of Indonesian politics. The question of whether a novice, reformist president would be able to capitalise on his or her popular mandate to overcome some of the entrenched deficits of Indonesia’s democracy is much more enticing than that of whether an already flawed democratic system would be sufficiently resilient to withstand the efforts of an authoritarian-era president to wind back reforms. Whatever the other effects of Jokowi’s emergence, that shift in focus will stand as an influential change in Indonesian politics in the past year.

REFERENCES

Aspinall, E. (2010) ‘The irony of success’, Journal of Democracy 21 (2): 20–34. Buehler, M. (2013) ‘Married with children’, Inside Indonesia 112 (April–June).

Butt, S. (2011) ‘Anti-corruption reform in Indonesia: an obituary?’, Bulletin of Indonesian

Economic Studies 47 (3): 381–94.

Butt, S. (2013) ‘Indonesia’s anti-corruption courts: are they as bad as most people say and are they getting better?’ in ‘Is Indonesia as corrupt as most people believe and is it get-ting worse?’, H. Dick and S. Butt, CILIS, Melbourne: 17–24.

Butt, S. and Lindsey, T. (2010) ‘Judicial mafia: the courts and state illegality in Indonesia’, in

The State and Illegality in Indonesia, eds E. Aspinall and G. Van Klinken, KITLV, Leiden: 189–213.

CSIS (Centre for Strategic and International Studies) (2013) ‘Uninstitutionalized’ Political

Parties and the Search of Alternative Presidential Candidates, CSIS, Jakarta.

Coomaraswamy, R. (1999) ‘Integration of the human rights of women and the gender per-spective: violence against women – report of the special rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences, Ms. Radhika Coomaraswamy’, United Nations Economic and Social Council Document E/CN.4/1999/68/Add.3.

Crouch, H. (2010) Political Reform in Indonesia After Soeharto, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore.

Diamond, L. (2009) ‘Is a “rainbow coalition” a good way to govern?’ Bulletin of Indonesian

Economic Studies 45 (3): 337–40.

Dick, H. (2013) ‘Statistics, half-truths and anti-corruption strategies’ in ‘Is Indonesia as cor-rupt as most people believe and is it getting worse?’, H. Dick and S. Butt, CILIS, Mel-bourne: 5–15.

Dick, H. and Butt, S. (2013) ‘Is Indonesia as corrupt as most people believe and is it getting worse?’, CILIS, Melbourne.

Fealy, G. (2011) ‘Indonesian politics in 2011: democratic regression and Yudhoyono’s regal incumbency’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 47 (3): 333–53.

Fealy, G. (2013) ‘Indonesia politics in 2012: graft, intolerance, and hope of change’, in

South-east Asian Affairs, ed. D. Singh, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore: 103–20. Hadiz, V. (2010) Localising Power in Post-Authoritarian Indonesia: A Southeast Asian

Perspec-tive, ISEAS, Singapore.

Hamid, S. (2012) ‘Indonesian politics in 2012: coalitions, accountability and the future of democracy’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 48 (3): 325–45.

Honna, J. (2013) ‘Security challenges and military reform in post-authoritarian Indonesia: the impact of separatism, terrorism and communal violence’, in The Politics of Military

Reform: Experiences from Indonesia and Nigeria, eds J. Rüland, M-G. Manea and H. Born, Springer, Heidelberg: 185–200.

Indonesia Corruption Watch (2013) Laporan Pemantauan ICW: Vonis Kasus Korupsi di

Pen-gadilan Pasca 3 Tahun Pembentukan PenPen-gadilan Tipikor [ICW monitoring report: court ver-dicts in corruption cases in the three years after the formation of the corruption courts].

IPAC (Institute for the Policy Analysis of Conflict) (2013) Carving Up Papua: More Districts, More Trouble, IPAC, Jakarta.

International Crisis Group (2013) Indonesia: Tensions over Aceh’s Flag, International Crisis Group, Jakarta.

Jansen, D. (2010) ‘Snatching victory’, Inside Indonesia 100 (April–June).

Jung, E. (2008) ‘Giving up partisan politics?’, Inside Indonesia 94 (October–December). Kawamura, K. (2010) ‘Is the Indonesian president strong or weak?’, Institute of Developing

Economies Discussion Paper No. 235, Institute of Developing Economies, Tokyo. Lembaga Survei Indonesia (2012) ‘Mencari Calon Presiden 2014, Survei Nasional 1-12

Febru-ari 2012’ [Seeking a 2014 presidential candidate, national survey 1–12 February 2012], available at <http://www.lsi.or.id/file_download/132>.

LIPI (Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia) (2013) Survei Pra-Pemilu 2014: Potret Suara

Pemilih Satu Tahun Jelang Pemilu, [Pre-2014 election survey: a portrait of voter opinions one year before the election] LIPI, Jakarta.

McLeod, R. (2008) ‘Survey of recent developments’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 44 (2): 183–208.

McMichael, H. (2009) ‘The Lapindo mudflow disaster: environmental, infrastructure and economic impact’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 45 (1): 73–83.

Mietzner, M. (2009a) ‘Indonesia’s 2009 elections: populism, dynasties and the consolida-tion of the party system’, Lowy Institute for Internaconsolida-tional Policy, Sydney.

Mietzner, M. (2009b) Military Politics, Islam and the State in Indonesia: From Turbulent

Transi-tion to Democratic ConsolidaTransi-tion, Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore. Mietzner, M. (2010), ‘Indonesia’s direct elections: empowering the electorate or

entrench-ing the New Order oligarchy?’, in Soeharto’s New Order and its Legacy: Essays in Honour

of Harold Crouch, eds E. Aspinall and G. Fealy, ANU E Press, Canberra: 173–90.

Mietzner, M. (2012) ‘Indonesia’s democratic stagnation: anti-reformist elites and resilient civil society’, Democratization 19 (2): 209–29.

Phelps, N., Bunnell, T., Miller, M. and Taylor, J. (2013) ‘Urban inter-referencing within and beyond a decentralized Indonesia’, Asia Research Institute, Singapore.

Sherlock, S. (2009) ‘SBY’s consensus cabinet – lanjutkan?’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic

Studies 45 (3): 341–3.

Sumner, C. and Lindsey, T. (2010) ‘Courting reform: Indonesia’s Islamic courts and justice for the poor’, Lowy Institute for International Policy, Sydney.

Tomsa, D. (2010) ‘Indonesian politics in 2010: the perils of stagnation’, Bulletin of Indonesian

Economic Studies 46 (3): 309–28.

Wilson, L. and Nugroho, E. (2012) ‘For the good of the people?’, Inside Indonesia 109 (July– September.