Electronic commerce adoption: an empirical study of

small and medium US businesses

Elizabeth E. Grandon

a,*, J. Michael Pearson

baDepartment of Accounting and Computer Information Systems, School of Business, Emporia State University, Emporia, KS 66801, USA bDepartment of Management, College of Business and Administration, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL 62901, USA

Accepted 22 December 2003

Available online 9 April 2004

Abstract

By combining two independent research streams, we examined the determinant factors of strategic value and adoption of electronic commerce as perceived by top managers in small and medium sized enterprises (SME) in the midwest region of the US. We proposed a research model that suggested three factors that have been found to be influential in previous research in the perception of strategic value of other information technologies: operational support, managerial productivity, and strategic decision aids. Inspired by the technology acceptance model and other relevant research in the area, we also identified four factors that influence electronic commerce adoption: organizational readiness, external pressure, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness. We hypothesized a causal link between the perceived strategic value of electronic commerce and electronic commerce adoption. To validate the research model, we collected data from top managers/owners of SME by using an Internet survey.

#2004 Elsevier B.V. All rights reserved.

Keywords:e-Commerce adoption; Strategic value of e-commerce; SMEs

1. Introduction

Electronic commerce (e-commerce) has been defined in several ways depending on the context and research objective of the author. For this study, we have taken two definitions of e-commerce[44,58]

and adapted them in a B2C context: ‘‘the process of buying and selling products or services using electro-nic data transmission via the Internet and the www.’’ E-commerce provides many benefits to both sellers and buyers; e.g. Napier et al. [43] pointed out that by implementing and using e-commerce sellers can

access narrow markets segments that are widely dis-tributed while buyers can benefit by accessing global markets with larger product availability from a variety of sellers at reduced costs. Improvement in product quality and the creation of new methods of selling existing products are also benefits [13].

The benefits of e-commerce are not only for large firms; small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) can also benefit from e-commerce[52]. In addition, it can ‘‘level the playing field’’ with big business, provide location and time independence, and ease communi-cation [16,29,38,50]. However, in spite of the many potential advantages of e-commerce, its adoption by SMEs remains limited. For example, a survey con-ducted by Verizon [20] found that 36% of small businesses established web sites primarily to advertise

Information & Management 42 (2004) 197–216

*Corresponding author. Tel.:þ1-620-341-5685; fax:þ1-620-341-6346.

E-mail address:[email protected] (E.E. Grandon).

and promote their business, compared to 9% who established one to sell or market online. Similarly, in a survey of 444 SMEs during 2002, Pratt[47]found that many SMEs were reluctant to conduct transac-tions on line; more than 80% were only using the Internet to communicate (via e-mail) and gather busi-ness information. Does this mean that top managers/ owners of SMEs do not realize the strategic value e-commerce to their business or does this mean that they encounter significant barriers to implementing it? Here, we focused our attention on this ‘‘under-studied’’ segment of business organizations [19]

where research findings on large businesses cannot be generalized; e.g. Welsh and White[66]identified important differences in the financial management of small and large businesses while Ballantine et al.

[5] identified unique characteristics of SMEs as lack of business and IT strategy, limited access to capital resources, greater emphasis on using IT and IS to automate rather than informate, influence of major customers, and limited information skills. Similar assertions and findings are given in other papers

[14,18,32,40,46,51].

2. Literature review

This study represents a fusion of two independent research streams: the strategic value of certain infor-mation technologies to top managers and factors that influence the adoption of IT. The former has been studied by Subramanian and Nosek [60] and others (e.g.[6,11]) while the latter has been investigated by Davis [21] and others (e.g. [1,30,35,65]) primarily through the technology acceptance model (TAM).

2.1. Perceived strategic value of IT

Many studies have focused on the relationship between IT investment and firm’s performance in large corporations. For example, Hitt and Brynjolfsson[27]

investigated how IT affects productivity, profitability, and consumer surplus. They found that IT increases productivity and consumer surplus but not necessarily business profits. Barua et al. concluded that the pro-ductivity gains from IT investments have generally been neutral or negative, while Tallon et al. [62]

measured IT payoffs through perceptual measures

and argued that executives rely on their perceptions in determining whether a particular IT investment creates value for the firm.

The majority of the research has proposed a direct causal link between IT investment and firm perfor-mance. However, Li and Ye[37]empirically tested the moderating effects of environmental dynamism, firm strategy, and CIO/CEO relationship on the effect of IT investment on firm performance and found that IT investment appears to have a stronger positive impact on financial performance when there are greater envir-onmental changes, the strategy of the company is more proactive, and closer CIO/CEO ties. In a similar line of inquiry, Lee [36] created a multi-level value model that connects the use of IT to a firm’s profit; she pointed out that the effect of incorporating IT should not be considered alone and argued that there are other variables that can influence the relationship. Her IT business value model incorporated other variables, such as origination cost, cycle time, loan officer retention, control over external partners, and market-ing effort and she found that IT can reduce cycle time and cost, and change the way business is run. She concluded that ‘‘one has to know what other variables to manage and how to manage them in order to make IT investments profitable.’’

Few studies have focused on the perceptions of top management regarding the strategic value of e-com-merce. Amit and Zott [4] is one of the few that has tried to deal with this and even though they focused on e-business, their results can be generalized to e-commerce[28]. They examined how 59 American and European publicly traded e-business firms create value. Approximately, 80% were SMEs (with less than 500 employees). They developed a value-drivers model which included four factors found to be sources of value creation: transaction efficiency, complemen-tarities, lock-in, and novelty. Some of these factors are also found in Saloner and Spence’s[56]work.

e-commerce, their model was used as the basis for the strategic value portion of this study.

2.2. Information technology adoption

Davis proposed TAM, a model that has been tested in many studies (e.g.[26,59,61]). Lederer et al. sum-marized sixteen articles that tested the model for different technologies (e.g. ATM, e-mail, Netscape, Access, Internet, Word, and Excel). In their model, they considered beliefs about ease of use and per-ceived usefulness as the major factors influencing attitudes toward use, which, in turn, affected intentions to use.

Many other studies have attempted to describe the factors influencing IT adoption in SMEs. For example, Iacovou et al. studied factors influencing the adoption of electronic data interchange (EDI) by seven SMEs in different industries; they included perceived benefits, organizational readiness, and external pressure. To measure perceived benefits they used awareness of both direct and indirect benefits. Variables measuring organizational readiness were the financial and tech-nological resources. In order to measure external pressure, they considered competitive pressure and its imposition by partners. The results suggested that a major reason that small firms become EDI-capable is due to external pressure (trading partners). In a similar study, Chwelos et al.[17]considered the same factors influencing the adoption of EDI in 286 SMEs. They considered the trading partner as influencing external pressure and readiness while external pressure was considered to be influenced by the dependency on trading partner and enacted trading partner power. As in the case of Iacovou et al., external pressure was the most important factor contributing to intent to adopt EDI. Kuan and Chau [34] determined the factors influencing the adoption of EDI in small businesses using a technology, organization, and environment framework. The technology factor incorporated per-ceived direct and indirect benefits of EDI. The orga-nization factor consisted of perceived financial cost and perceived technical competence. The environ-ment factor was similar to external pressure in Iacovou et al.’s study but included a new variable: perceived government pressure. There, perceived indirect benefits were not found to be a significant factor.

Igbaria et al. determined the factors affecting personal computer acceptance in small businesses. Among the factors that directly influence personal computer acceptance were perceived ease of use and perceived usefulness. The intra-organizational (inter-nal computing support and training, and management support) and extra-organizational (external computing support and training) variables were hypothesized to influence adoption through perceived usefulness and ease of use. Inconsistent with research in large firms, relatively little support was found for the influence of internal support and training on perceived ease of use and usefulness. However, perceived ease of use turned out to be an important factor in explaining perceived usefulness and system usage. It was also found that perceived usefulness is a strong antecedent of system usage.

In order to develop an integrated model of IS adoption in SMEs, Thong[63]specified four contex-tual variables as primary determinants of IS adoption. He highlighted the fact that the technological innova-tion literature has identified many variables as possible determinants of organizational adoption but this ‘‘suggest that more research is needed to identify the critical ones’’ and provided four groups of vari-ables: CEO, IS, organizational characteristics, and environmental characteristics.

Based on the literature, Premkumar and Roberts

[49] identified the use of various communication technologies and the factors that influence their adop-tion in small businesses located in rural US commu-nities. The technologies studied included EDI, online data access, e-mail, and the Internet. The factors studied as potential discriminators between adopters and non-adopters of communication technologies were grouped into three broad categories: innovation, organizational, and environment characteristics. Within the innovation factor, they included relative advantage, cost, complexity, and compatibility. Orga-nizational characteristics included top management support, and IT expertise. Finally, within the environ-mental characteristics variable, competitive pressure, external support, and vertical linkages were consid-ered. The results suggested that relative advantage, top management support, and competitive pressure were factors influencing the three communication technol-ogies. Compatibility, complexity, external pressure, and organizational size were found to be significant

discriminators between adopters and non-adopters of online data access technology. Cost was found to be an important discriminant factor only for the adoption of the Internet. IT expertise was not found to be an important factor that discriminates between adopters and non-adopters. Finally, vertical linkage was found to be an important discriminant factor for online data access and the Internet adoption.

The adoption of the Internet was also studied by Mehrtens et al.[41]. In order to develop a model of Internet adoption, they conducted a case study on seven SMEs. First, they considered four SMEs that had adopted the Internet. Based on Iacovou et al.’s work and the results of the preliminary analysis, they devised their model using perceived benefits, organi-zational readiness, and external pressure as determi-nant factors. Then, to provide theoretical replication they considered three non-IT SMEs, of which two had adopted the Internet and one had not. All the factors were found to affect Internet adoption by the small firms. Chang and Cheung[12]also determined factors that influence Internet/www adoption with similar results.

In a more recent study and following a similar line of inquiry, Riemenschneider et al. [55] studied the factors that influence web site adoption by SMEs. They proposed a combined model using the theory of planned behavior (TPB)[3]and TAM. They tested individual models, partially integrated models, and fully integrated models by using structural equation modeling. They found that the combined model pro-vided a better fit.

The emerging field of e-commerce has not been ignored in the analysis of adoption. Mirchandani and Motwani[42]investigated the factors that differentiate adopters from non-adopters of e-commerce in small businesses. The relevant factors included enthusiasm of top management, compatibility of e-commerce with the work of the company, relative advantage perceived from e-commerce, and knowledge of the company’s employees about computers. The degree of depen-dence of the company on information, managerial time required to plan and implement the e-commerce application, the nature of the company’s competition, as well as the financial cost of implementing and operating the e-commerce application were not influencing factors. Similarly, Riemenschneider and McKinney[54]analyzed the beliefs of small business

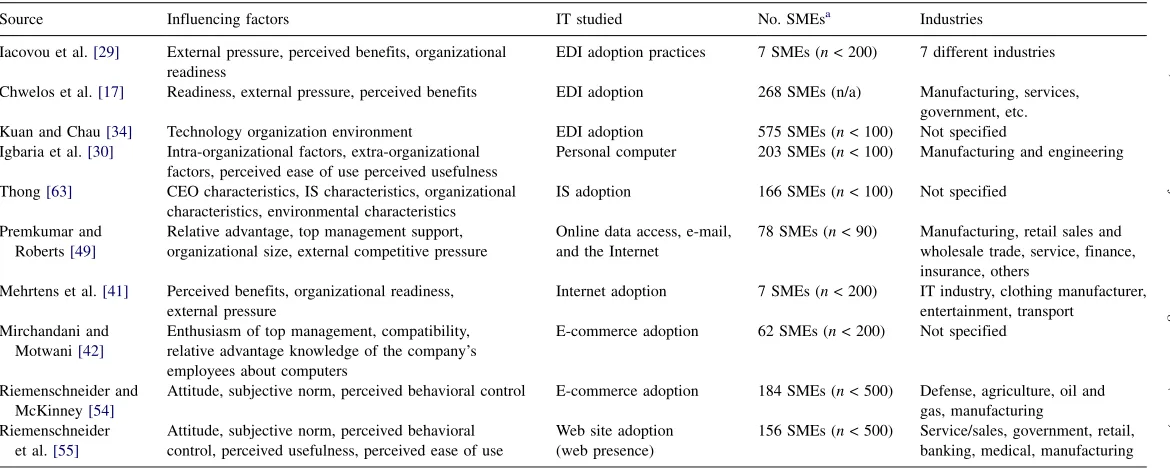

executives on the adoption of e-commerce. They found that all the component items of the normative and control beliefs differentiated between adopters and non-adopters. In the behavioral beliefs (attitude) group, however, only some items (e-commerce enhances the distribution of information, improves information accessibility, communication, and the speed with which things get done) were found to differentiate adopters from non-adopters. Table 1

summarizes the factors involved in the process of technology adoption.

2.3. Causal link

Support for the causal link between perceptions of strategic value and adoption comes from different studies that associate individual perceptions and beha-vior. The theory of planned behavior (TPB) is a well established intention model that has been proven successful in predicting and explaining behavior across a wide variety of domains, including the use of information technology [2]. In general terms, the TPB establishes that perceptions influence intentions which in turn influence the actual behavior of the individual. By considering the intention to adopt e-commerce as the target behavior, the use of intention models theoretically justifies the causal link between perceptions and adoption of e-commerce.

Table 1

Summary of factors of IT adoption in SMEs

Source Influencing factors IT studied No. SMEsa Industries

Iacovou et al.[29] External pressure, perceived benefits, organizational readiness

EDI adoption practices 7 SMEs (n< 200) 7 different industries

Chwelos et al.[17] Readiness, external pressure, perceived benefits EDI adoption 268 SMEs (n/a) Manufacturing, services, government, etc. Kuan and Chau[34] Technology organization environment EDI adoption 575 SMEs (n< 100) Not specified Igbaria et al.[30] Intra-organizational factors, extra-organizational

factors, perceived ease of use perceived usefulness

Personal computer 203 SMEs (n< 100) Manufacturing and engineering

Thong[63] CEO characteristics, IS characteristics, organizational characteristics, environmental characteristics

IS adoption 166 SMEs (n< 100) Not specified

Premkumar and Roberts[49]

Relative advantage, top management support, organizational size, external competitive pressure

Online data access, e-mail, and the Internet

78 SMEs (n< 90) Manufacturing, retail sales and wholesale trade, service, finance, insurance, others

Mehrtens et al.[41] Perceived benefits, organizational readiness, external pressure

Internet adoption 7 SMEs (n< 200) IT industry, clothing manufacturer, entertainment, transport

Mirchandani and Motwani[42]

Enthusiasm of top management, compatibility, relative advantage knowledge of the company’s employees about computers

E-commerce adoption 62 SMEs (n< 200) Not specified

Riemenschneider and McKinney[54]

Attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control E-commerce adoption 184 SMEs (n< 500) Defense, agriculture, oil and gas, manufacturing Riemenschneider

et al.[55]

Attitude, subjective norm, perceived behavioral control, perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use

Web site adoption (web presence)

156 SMEs (n< 500) Service/sales, government, retail, banking, medical, manufacturing

anrepresents the maximum number of employees considered in the criteria to define a SME.

E.E.

Gr

andon,

J.M.

P

earson

/

Information

&

Manage

ment

42

(2004)

197

–216

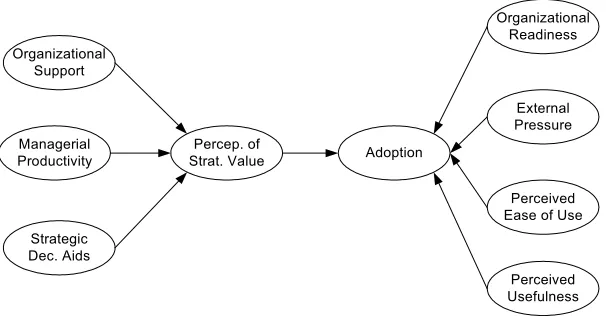

3. Research model

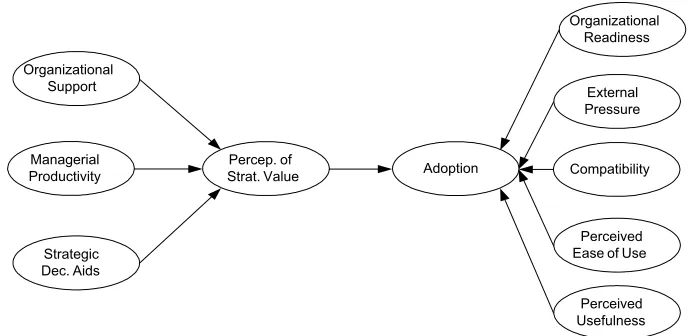

Based on the literature review, we proposed a research model (Fig. 1).

3.1. Perception of strategic value of e-commerce

We considered three major variables as sources of strategic value of e-commerce: ‘‘operational support, managerial productivity, and strategic decision aids.’’ Since the instrument utilized by Subramanian and Nosek was found to have high reliability (Cronbach alpha¼0:82) with convergent and discriminant

valid-ity, we used their items to measure the strategic value construct.Operational supportmeasures how e-com-merce can reduce costs, improve customer services and distribution channels, provide effective support role to operations, support linkages with suppliers, and increase ability to compete.Managerial productivity

suggests how e-commerce can enhance access to information, provides a means to use generic methods in decision-making, improves communication in the organization, and improves productivity of managers. Finally, strategic decision aids defines how e-com-merce can support strategic decisions of managers, support cooperative partnerships in the industry, and provide information for strategic decisions.

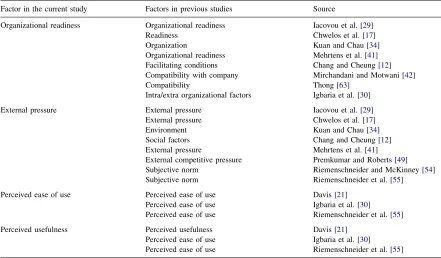

3.2. Factors influencing adoption of e-commerce

We identified the factors found significant in prior research and grouped them based on similarity and

face validity into four different variables: ‘‘organiza-tional readiness, external pressure, perceived ease of use, and perceived usefulness’’ (seeTable 2).

Organizational readinesswas assessed by including two items about the financial and technological resources that the company may have available as well as factors dealing with the compatibility and consistency of e-commerce with firm’s culture, values, and preferred work practices (existing technology infrastructure; and top management’s enthusiasm to adopt e-commerce). Such items were found relevant in other research[7,15,48,64].

External pressure was assessed by incorporating

five items: competition, social factors, dependency on other firms already using e-commerce, the industry, and the government.

We considered a subset of Davis’ instrument to

mea-sureperceived ease of useas modified to make them

relevant to e-commerce. We utilized the six items for per-ceived usefulnessof Davis as modified to fit our research.

3.3. Research questions

The questions we explored were used to validate the proposed two-step model and understand the relation-ship between these two steps.

1. What are the determinant factors of the perceived strategic value of e-commerce in SME?

2. How do the perceptions of strategic value, as viewed by top managers/owners of SMEs, influence their decision to adopt e-commerce?

Organizational Support

Managerial Productivity

Strategic Dec. Aids

Percep. of

Strat. Value Adoption

Organizational Readiness

External Pressure

Perceived Ease of Use

Perceived Usefulness

3. What are the factors involved in the decision to adopt e-commerce by top managers/owners of SMEs?

4. Methodology

4.1. Subjects

We targeted top managers of small and medium size business from a variety of industries in the midwest region of the US. In our study, we considered the number of employees as the principal criterion in determining whether a firm qualified as an SME since other categorizations involving revenue, total capital and/or other types are more difficult to apply and can result in misleading classifications. The number of employees varies according to the agency providing the definition. For example, the US Small Business Administration (http://www.sba.gov) uses a cut-off of fewer than 500 employees. Harrison et al. [25] and Iacovou et al. utilized a cut-off of 200 employees. For this study, we have used ‘‘less than 500 employees.’’

4.2. Data collection

The data were gathered by means of an electronic survey administered during Spring 2002. The process was carried out in three steps. First, a sample of 1069 small and medium size businesses were identified from various sources that focus on SMEs. We identi-fied the company name, a contact person, an e-mail address for that person, an address, and a telephone number. The contact person was typically the owner of the business or a top-level manager. Second, an initial e-mailing that identified the purpose of the study, a request to participate, and an opt-out feature was sent to all potential respondents; 136 of these messages were returned due to incorrect addresses or that the organization was no longer in business. An additional 101 individuals indicated that they were unable or were unwilling to participate.

Thirdly, approximately one week after the initial mailing, a second electronic mailing was sent to the remaining 832 potential respondents. This elec-tronic message directed them to the web site where the survey instrument was located. One hundred

Table 2

Summary of adoption factors in the current study

Factor in the current study Factors in previous studies Source

Organizational readiness Organizational readiness Iacovou et al.[29]

Readiness Chwelos et al.[17]

Organization Kuan and Chau[34]

Organizational readiness Mehrtens et al.[41] Facilitating conditions Chang and Cheung[12] Compatibility with company Mirchandani and Motwani[42]

Compatibility Thong[63]

Intra/extra organizational factors Igbaria et al.[30]

External pressure External pressure Iacovou et al.[29]

External pressure Chwelos et al.[17]

Environment Kuan and Chau[34]

Social factors Chang and Cheung[12]

External pressure Mehrtens et al.[41] External competitive pressure Premkumar and Roberts[49] Subjective norm Riemenschneider and McKinney[54] Subjective norm Riemenschneider et al.[55]

Perceived ease of use Perceived ease of use Davis[21] Perceived ease of use Igbaria et al.[30] Perceived ease of use Riemenschneider et al.[55]

Perceived usefulness Perceived usefulness Davis[21]

Perceived ease of use Igbaria et al.[30] Perceived ease of use Riemenschneider et al.[55]

individuals completed the survey for a response rate of 12%. Possible explanations for this relatively low response rate could include the lack of relevance of the topic to the respondent, delivery method of the instru-ment (electronic), and the time of the year at which the survey request took place.

4.3. Instrument development

Three top managers participated in a pilot of the survey instrument. One of the authors observed the subjects as they completed the survey. Feedback from them resulted in minor changes to the survey instructions and questions. Respondents were required to complete the survey that had the following major sections (see Appendix A for the complete instru-ment).

Seven demographic questions (respondent’s gender, age, education, years of work in present position, and years of work in present firm).

Two general questions about the firm (number of employees and industry.

Four questions about the technology in the organi-zation (number of PCs, presence of Internet server provider, presence of web site, and utilization of e-commerce).

Fifteen questions asking the extent to which e-commerce is perceived as contributing to strategic value.

Twenty-three questions to measure the factors

involved in e-commerce adoption.

A seven-point Likert scale (from strongly disagree to strongly agree) was utilized to measure the ques-tions about perceived strategic value and adoption of e-commerce.

5. Results

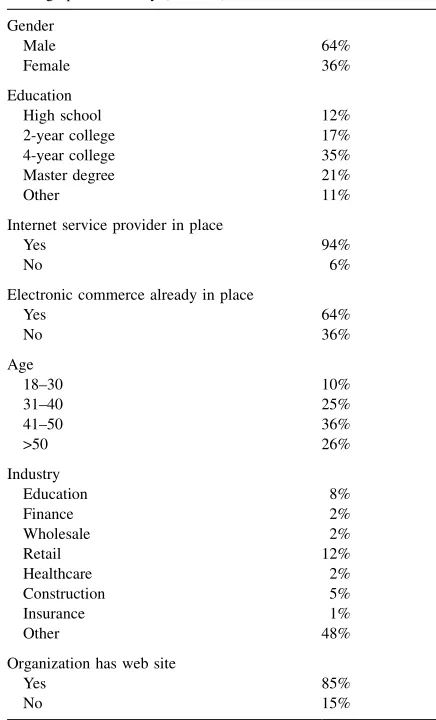

5.1. Demographics and descriptive statistics

The 100 surveys were returned over a 4-week period. Results indicated that the top managers were well educated, with over 56% holding a 4-year college degree or a masters degree. The majority were male (64%) and 36% were between 41 and 50 years of age.

Table 3shows other demographics.

5.2. Statistical analysis

In order to test the model, a statistical analysis was conducted in two stages. The first step employed confirmatory factor analysis to measure whether the number of factors and loadings of items involved in the two main constructs (perceived strategic value and adoption) conform to the proposed model. With this analysis, we found answers to research questions 1 and 3.

Since we were also interested in exploring how the perceptions of strategic value influence the decision to adopt e-commerce (research question 2), canonical analysis was utilized in the second step. This technique

Table 3

Demographics of study (n¼100)

Gender

Internet service provider in place

Yes 94%

No 6%

Electronic commerce already in place

Yes 64%

Organization has web site

Yes 85%

involves developing a linear combination of indepen-dent variables (strategic value variables) and depenindepen-dent variables (adoption variables) to maximize the correla-tion between the two sets [24]. MIS research has benefited from the use of this multivariate technique (see, for example[9,33]). Campbell and Taylor [10]

demonstrated that canonical analysis subsumes other statistical procedures.

Non-response is a potential source of bias in survey studies; it needed to be properly investigated[22]. The potential bias was evaluated by comparing responses between early and late respondents. Early respondents were those who had completed the questionnaire within the initial 2-weeks, while late respondents were those who completed it after the specified period. Approximately 70% of the responses were from early respondents. Demographic data was utilized for this purpose: number of employees, number of years in the current position, number of years in the firm, and number of personal computers in the company. No significant differences were found between the early and late respondent groups, suggesting no non-response bias.

5.3. Confirmatory factor analysis

5.3.1. Perceived strategic value construct

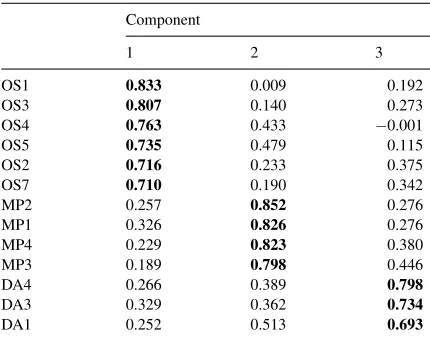

A confirmatory factor analysis was run using SPSS 10.1. All items measuring the perception of strategic value of e-commerce were considered during the first run and resulted in one item not loading on the intended factors. This item was dropped from subse-quent analysis and the construct was recalculated. The items in the final analysis for perceived strategic value are shown inAppendix B.

The factor analysis used principal components in order to extract the maximum variance from the items. To minimize the number of items that have high loadings on any given factor, a varimax rotation was utilized. Using the Kaiser Eigenvalues criterion, we extracted three factors that collectively explained 79.4% of the variance in all items. Hair et al. provide guidelines for identifying significant factor loadings based on sample size. In order to obtain a power level of 80% at a 0.05 significant level, with standard errors assumed to be twice those of conventional correlation coefficient, a factor loading of 0.50 or higher should be considered as a cut-off value.

The rotated component matrix inTable 4shows that all the items loaded cleanly on their intended factors. Six items loaded cleanly on the organizational support factor, four items on the managerial productivity factor, and three on the decision aids factor. Conver-gent and discriminant validity was assessed via factor analysis. Table 4 shows that all items have loading greater than 0.50 and loaded stronger on their asso-ciated factors than on others. Thus, convergent and discriminant validity were demonstrated.

Construct reliability or internal consistency was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha.Table 5shows that the values for alpha vary from 0.88 to 0.95. The scale reliabilities are unusually good compared to the accep-table 0.7 level for field research[45].

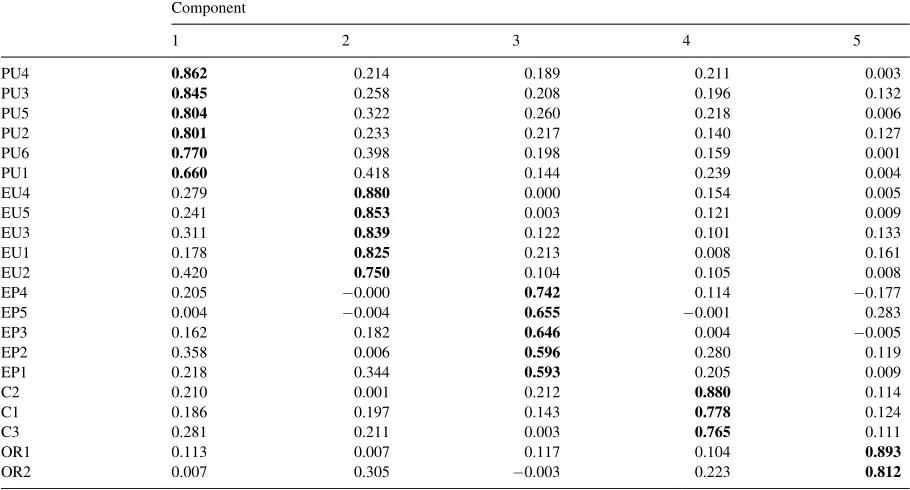

5.3.2. Adoption construct

The adoption construct initially consisted of 23 items. In order to test how these items loaded, another factor analysis was run. Principal component extraction with varimax rotation and required Eigenvalues above 1.0 were considered. As in the case of the perceived

Table 4

Rotated component matrix

Component

1 2 3

OS1 0.833 0.009 0.192 OS3 0.807 0.140 0.273 OS4 0.763 0.433 0.001 OS5 0.735 0.479 0.115 OS2 0.716 0.233 0.375 OS7 0.710 0.190 0.342

MP2 0.257 0.852 0.276

MP1 0.326 0.826 0.276

MP4 0.229 0.823 0.380

MP3 0.189 0.798 0.446

DA4 0.266 0.389 0.798

DA3 0.329 0.362 0.734

DA1 0.252 0.513 0.693

Table 5

Reliability analysis

Construct Cronbach’s alpha

Operational support (OS) 0.91 Managerial productivity (MP) 0.95 Decision aids (DA) 0.88

strategic value construct, the first run of the factor analysis resulted in items that did not load as expected on the intended factors. Two items were dropped from the analysis and the construct was recalculated.

The results of this confirmatory factor analysis resulted in five factors loading cleanly with a total explained variance of 74.9%. Thus, we revised the proposed model and considered a fifth factor, which we named ‘‘compatibility’’ to better describe the items used (see Fig. 2). The results are quite interesting. Previous research has found compatibility an impor-tant factor that influences the adoption of IT. In our study, compatibility emerged freely as a significant independent factor.

The items considered in the final instrument are shown inAppendix C. The following table shows the rotated component matrix.

Convergent and discriminant validity was achieved.

Table 6shows that all items have loading greater than

0.50. They also loaded stronger on their associated factors than on others. Thus, convergent and discri-minant validity were demonstrated.Table 7shows that alpha values range from 0.76 to 0.95 for the perceived usefulness of e-commerce factor. As in the case of the strategic value construct, the reliability of the adoption construct turned out to be very high.

5.4. Canonical analysis

Canonical analysis is a multivariate statistical model that studies the interrelationships among sets

of multiple dependent variables and multiple indepen-dent variables. By simultaneously considering both, it is possible to control for moderator or suppressor effects that may exists among various dependent variables[39].

In canonical analysis there are criterion variables (dependent variables) and predictor variables (inde-pendent variables). The maximum number of cano-nical correlations (functions) between these two sets of variables is the number of variables in the smaller set [23]. In our case, the number of variables for the perception of strategic value construct is three while the number of variables in the adoption con-struct is five. Thus, the number of canonical functions extracted from the analysis is three; i.e., the smallest set.

In order to test the significance of the canonical functions we followed the guidelines given by Hair et al. They suggest three different measures to inter-pret the canonical functions:

(a) the significance of the F-value given by Wilk’s lambda, Pillai’s criterion, Hotteling’s trace, and Roy’s gcr;

(b) the measures of overall model fit given by the size of the canonical correlations; and

(c) the redundancy measure of shared variance.

Table 8shows the corresponding multivariate test of

significance with 15 degrees of freedom whileTable 9

shows the measures of overall model fit in the three canonical functions. Note that the strength of the

Organizational Support

Managerial Productivity

Strategic Dec. Aids

Percep. of

Strat. Value Adoption

Organizational Readiness

External Pressure

Perceived Ease of Use

Perceived Usefulness Compatibility

relationship between the canonical covariates is given by the canonical correlation.

Even though the multivariate test of significance shows that the canonical functions, taken collectively,

are statistically significant at the 0.01 level, from the overall model fit (Table 9) it can be concluded that only the first canonical function is significant (P<0:01). This conclusion is consistent with the

canonical R2values showed inTable 9. For these data, in the first canonical function the independent variables explain approximately 42% of the variance in the dependent variables; the second canonical function explains approximately 7%, and the third one explains only 1.5%. This is not unusual since typically the first canonical function is far more important than the others.

Even though the first canonical function was deemed to be significant, it has been recommended that redundancy analysis be utilized to determine

Table 6

Rotated component matrix

Component

1 2 3 4 5

PU4 0.862 0.214 0.189 0.211 0.003 PU3 0.845 0.258 0.208 0.196 0.132 PU5 0.804 0.322 0.260 0.218 0.006 PU2 0.801 0.233 0.217 0.140 0.127 PU6 0.770 0.398 0.198 0.159 0.001 PU1 0.660 0.418 0.144 0.239 0.004

EU4 0.279 0.880 0.000 0.154 0.005

EU5 0.241 0.853 0.003 0.121 0.009

EU3 0.311 0.839 0.122 0.101 0.133

EU1 0.178 0.825 0.213 0.008 0.161

EU2 0.420 0.750 0.104 0.105 0.008

EP4 0.205 0.000 0.742 0.114 0.177

EP5 0.004 0.004 0.655 0.001 0.283

EP3 0.162 0.182 0.646 0.004 0.005

EP2 0.358 0.006 0.596 0.280 0.119

EP1 0.218 0.344 0.593 0.205 0.009

C2 0.210 0.001 0.212 0.880 0.114

C1 0.186 0.197 0.143 0.778 0.124

C3 0.281 0.211 0.003 0.765 0.111

OR1 0.113 0.007 0.117 0.104 0.893

OR2 0.007 0.305 0.003 0.223 0.812

Table 7

Reliability analysis

Construct Cronbach’s alpha

Organizational readiness (OR) 0.81 Compatibility (CC) 0.88 External pressure (EP) 0.76

Ease of use (EU) 0.95

Perceived usefulness (PU) 0.95

Table 8

Multivariate test of significance

Test name Value Approx. F

Hypoth. DF

Error DF

Sig. of F Pillais 0.501 3.529 15 264.00 0.00 Hotellings 0.801 4.523 15 254.00 0.00 Wilks 0.535 4.028 15 237.81 0.00 Roys 0.415

Table 9

Measures of overall model fit

Canonical function

Canonical correlation

Canonical R2

F-statistic Probability

1 0.644 0.415 4.028 0.000

2 0.266 0.071 0.986 0.448

3 0.122 0.015 0.446 0.720

which functions to use in the interpretation. Redun-dancy is the ability of a set of independent variables, to explain the variation in the dependent variables taken one at a time.Table 10 summarizes the redundancy analysis for the dependent and independent variables for the three canonical functions. The results indicate that the first canonical function accounts for the high-est proportion of total redundancy (94.7% including both dependent and independent variables), the second one accounts for 3.5%, and the third one accounts only for 1.8%. In addition, the redundancy indexes are higher for the first canonical function than for the second. Therefore, only the first canonical function is considered for interpretation.

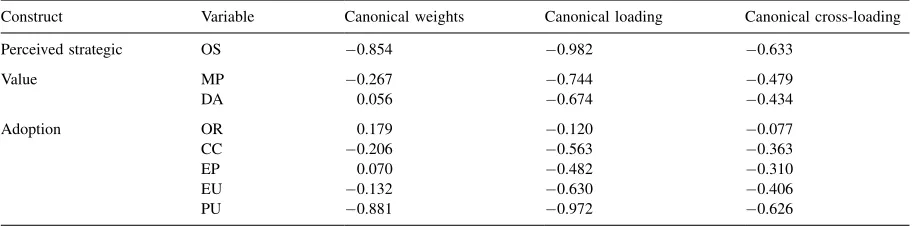

In order to interpret the selected canonical function, three methods were employed: canonical weights, canonical loadings, and canonical cross-loadings.

Table 11 shows the summary of these methods for

the first canonical function considering both indepen-dent and depenindepen-dent variables.

The interpretation of canonical weights is subject to some criticism. For example, Hair et al. stated, ‘‘a small weight may mean either that its corresponding

variable is irrelevant in determining the relationship or that it has been partialed out of the relationship because of a high degree of multicollinearity.’’ Cano-nical weights are also considered to have low stability from one sample to another. As in the case of weights, canonical loadings are subject to considerable varia-bility from one sample to another. For that reason, and in order to increase the external validity of the find-ings, the canonical cross-loadings method has been chosen.

These correlate each of the original observed depen-dent variables directly with the independepen-dent canonical variate, and vice versa.Table 11shows that almost all of the canonical cross-loadings are significant for both dependent and independent variables (cut-off >0.3) with the exception of organizational readiness (OR). The rank order of importance (determined by the absolute value of the canonical cross-loadings) for the perceived strategic value of e-commerce were organizational support (OS), managerial productivity (MP), and decision aids (DA). Similarly, the rank of importance for the adoption construct contributing to the first canonical function were perceived usefulness

Table 10

Canonical redundancy analysis

Canonical function

Variable Share variance CanonicalR2 Redundancy index

Proportion of total redundancy (%)

1 Dependent 0.381 0.415 0.158 34.7

Independent 0.658 0.415 0.273 60.0

2 Dependent 0.129 0.071 0.009 2.0

Independent 0.101 0.071 0.007 1.5

3 Dependent 0.247 0.015 0.004 0.9

Independent 0.242 0.015 0.004 0.9

Table 11

Standardized canonical coefficients and canonical loadings for strategic value and adoption

Construct Variable Canonical weights Canonical loading Canonical cross-loading

Perceived strategic OS 0.854 0.982 0.633

Value MP 0.267 0.744 0.479

DA 0.056 0.674 0.434

Adoption OR 0.179 0.120 0.077

CC 0.206 0.563 0.363

EP 0.070 0.482 0.310

EU 0.132 0.630 0.406

(PU), ease of use (EU), compatibility (CC), and exter-nal pressure (EP). Organizatioexter-nal readiness (OR) seemed to be a non-important factor in the adoption construct.

5.5. Sensitivity analysis

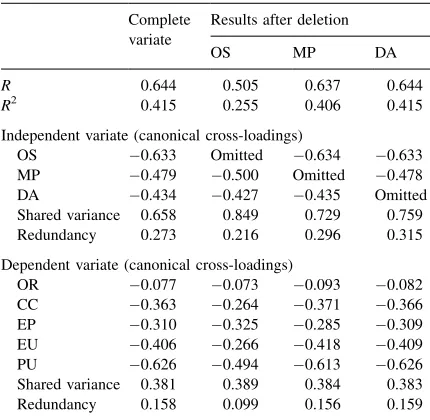

To validate the results, sensitivity analysis of the independent variable set was performed. Table 12

shows the results of the analysis after removing inde-pendent variables (one at a time). In this analysis canonical cross-loading were examined for stability. It can be seen from the table that the canonical cross-loadings are fairly stable when the independent vari-ables are deleted one at a time. The canonical correla-tions (R) as well as the canonical roots (R2) remain fairly stable. Similarly, the shared variance and redun-dancy indexes were found to be stable when removing some of the independent variables. Thus, the sensi-tivity analysis as a whole supported the validity of the canonical function.

6. Discussion

The confirmatory factor analysis corroborated Subramanian and Nosek’s results: all the variables

considered in the perception of strategic value con-struct (organizational support, managerial producti-vity, and decision aids) were found to be significant in explaining the perceptions of strategic value of e-commerce. The scale reliability was found to be comparable.

Most of the factors proposed as determinants of e-commerce adoption: perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, compatibility, and external pressure were found to be statistically significant as determinants of e-commerce adoption. These results corroborate the TAM model in the sense that perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use turned out to be the most influential factors of e-commerce adoption as per-ceived by top managers of SMEs. The results also confirm the studies of Igbaria et al. regarding the factors that influence personal computer adoption and Riemenschneider et al. concerning the factors that influence web site adoption, both in the context of SMEs.

Compatibility between e-commerce and firm’s cul-ture, values, and preferred work practices was also found to be an influential factor in our study. Results confirmed the earlier studies in which compatibility was considered an important factor in determining adoption. In our study, compatibility emerged freely as an independent factor that highly influenced e-com-merce adoption.

Regarding external pressure, our study validated previous research but contrary to what was expected, organizational readiness, which includes the financial and technological resources to adopt e-commerce, was not found to be a significant factor in the decision.

Finally, from the canonical analysis it can be con-cluded that managers who have positive attitude toward the adoption of e-commerce also perceived e-commerce as adding strategic value to the firm. Thus, interventions toward changing managers’ per-ceptions about the strategic value of e-commerce can be devised in order to increase the adoption/utilization of e-commerce by SMEs.

6.1. Limitations

Generalizations from this research should be made with caution. The main limitation corresponds to the number of employees considered in each company. Our sample is mainly of companies whose number of

Table 12

Sensitivity analysis of the canonical correlation results

Complete variate

Results after deletion

OS MP DA

R 0.644 0.505 0.637 0.644

R2 0.415 0.255 0.406 0.415

Independent variate (canonical cross-loadings)

OS 0.633 Omitted 0.634 0.633 MP 0.479 0.500 Omitted 0.478 DA 0.434 0.427 0.435 Omitted Shared variance 0.658 0.849 0.729 0.759 Redundancy 0.273 0.216 0.296 0.315

Dependent variate (canonical cross-loadings)

OR 0.077 0.073 0.093 0.082

CC 0.363 0.264 0.371 0.366

EP 0.310 0.325 0.285 0.309

EU 0.406 0.266 0.418 0.409

PU 0.626 0.494 0.613 0.626

Shared variance 0.381 0.389 0.384 0.383 Redundancy 0.158 0.099 0.156 0.159

employees varies between 10 and 200. Only five firms had more than 200. Thus the sample may be biased toward smaller firms.

7. Conclusions

Throughout this study we attempted to build a model that explains how perceived strategic value of e-commerce influences managers’ attitudes toward e-commerce adoption. By studying two different streams of research, we have proposed and validated a predictive model that suggest three factors as deter-minants of the perceived strategic value of e-com-merce and five determinant factors for e-come-com-merce adoption in SMEs.

The canonical results reveal a significant rela-tionship between the perceived strategic value of e-commerce variables and the factors that influence e-commerce adoption in SMEs. This means that those top managers who perceived e-commerce as adding strategic value to the firm have a positive attitude toward its adoption. From the canonical analysis, we conclude that the three factors proposed as determi-nants of perceived strategic value of e-commerce have significant impact on managers’ attitudes toward e-commerce adoption with organizational support and managerial productivity as the most influential. Over-all, we expect that the results will help managers’ understanding of the relationship between the percep-tions of strategic value of e-commerce and its future adoption.

Appendix A. The survey

Ecommerce, is defined here as ‘‘the process of buying and selling products or services using electronic data transmission via the Internet and the www.’’ Examples that do not fit this definition include electronic publishing to promote marketing, advertising, and customer support. The mere use of electronic mail or the use of a web site for electronic publishing purposes does not constitute ecommerce according to the definition above.

Section 1: General information

Gender Male Female

Age

Education High school 2-year college 4-year college Master/MBA Doctorate Other

Years in present position Years with present firm Total number of employees

Industry in which your firm operates Manufacturing Education Government Finance Wholesale Retail

Healthcare Construction Transportation Insurance Other

Number of PCs in the firm

Does your firm have an Internet service provider? Yes No Does your firm have a web site? Yes No

URL

Section 2: The following questions ask you about your perceptions of strategic value of electronic commerce. Please indicate your agreement with the next set of statements using the following rating scale.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Strongly disagree

Disagree Somewhat

disagree

Neutral Somewhat agree

Agree Strongly agree

In order to provide strategic value to our organization, electronic commerce should help

Disagree Agree

1 Reduce costs of business operations 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 2 Improve customer services 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 3 Improve distribution channels 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 4 Reap operational benefits 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 5 Provide effective support role to operations 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 6 Support linkages with suppliers 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 7 Increase ability to compete 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

In order to provide strategic value to our organization, electronic commerce should help

Disagree Agree

8 Provide managers better access to information

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

9 Provide managers access to methods and models in making functional area decisions

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

10 Improve communication in the organization 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 11 improve productivity of managers 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

In order to provide strategic value to our organization, electronic commerce should help

Disagree Agree

12 Support strategic decisions of managers 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 13 Help make decisions for managers 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 14 Support cooperative partnerships in

the industry

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

15 Provide information for strategic decision 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Section 3: The following questions ask you about your perceptions of adopting electronic commerce. Please

indicate your agreement with the next set of statements using the same rating scale above.

Disagree Agree

1 Our organization has the financial resources to adopt electronic commerce

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

2 Our organization has the technological resources to adopt electronic commerce

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Our organization perceives that electronic commerce is consistent with. . .

Section 3: (Continued)

Disagree Agree

3 culture 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

4 values 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

5 preferred work practices 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 6 Electronic commerce would be consistent with

our existing technology infrastructure

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

7 Top management is enthusiastic about the adoption of electronic commerce

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

8 Competition is a factor in our decision to adopt electronic commerce

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

9 Social factors are important in our decision to adopt electronic commerce

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

10 We depend on other firms that are already using electronic commerce

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

11 Our industry is pressuring us to adopt electronic commerce

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

12 Our organization is pressured by the government to adopt electronic commerce

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

13 Learning to operate electronic commerce would be easy for me

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

14 I would find electronic commerce to be flexible to interact with

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

15 My interaction with electronic commerce would be clear and understandable

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

16 It would be easy for me to become skillful at using electronic commerce

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

17 I would find electronic commerce easy to use 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 18 Using electronic commerce would enable

my company to accomplish specific tasks more quickly

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

19 Using electronic commerce would improve my job performance

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

20 Using electronic commerce in my job would increase my productivity

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

21 Using electronic commerce would enhance my effectiveness on the job

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

22 Using electronic commerce would make it easier to do my job

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

23 I would find electronic commerce useful in my job

1 2 3 4 5 6 7

24 I would like to receive the aggregated results of this survey

Yes No

25 I am interested in participating further in this study

Thank you for completing this survey. We recognize that your time is limited and we value your participation. Please complete the following section if you answered YES to either question 24 or 25 and you would prefer to be contacted at a different address than that shown on the cover sheet or if the person who completed this survey is not the same as the person to whom it was originally sent.

Name: Telephone: Fax: E-mail: Address:

Appendix B. Final items in the perceived strategic value construct

Perceived strategic value

Organizational support OS1 Reduce costs of business operations OS2 Improve customer service

OS3 Improve distribution channels OS4 Reap operational benefits

OS5 Provide effective support role to operations OS7 Increase ability to compete

Managerial productivity MP1 Provide managers better access to information

MP2 Provide managers access to methods and models in making functional area decisions

MP3 Improve communication in the organization MP4 Improve productivity of managers

Decision aids DA1 Support strategic decisions for managers DA3 Support cooperative partnerships in the industry DA4 Provide information for strategic decision

Appendix C. Final items in the adoption construct

Adoption

Organizational readiness OR1 Financial resources to adopt e-commerce OR2 Technological resources to adopt e-commerce Compatibility C1 With culture

C2 With values

C3 With preferred work practices

External pressure EP1 Competition is a factor in our decision to adopt e-commerce EP2 Social factors are important in our decision to adopt e-commerce EP3 We depend on other firms that are already using e-commerce EP4 Our industry is pressuring us to adopt e-commerce

EP5 Our organization is pressured by the government to adopt e-commerce

References

[1] D.A. Adams, R.R. Nelson, P.A. Todd, Perceived usefulness, ease of use, and usage of information technology: a replication, MIS Quarterly (June 1992), pp. 227–247. [2] R. Agarwal, Individual acceptance of information

technolo-gies, in: R.W. Zmud (Ed.), Framing the Domains of IT Management, Pinnaflex Education Resources, 2000, pp. 85– 104.

[3] I. Ajzen, The theory of planned behavior, Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes 50, 1991, pp. 179– 211.

[4] R. Amit, C. Zott, Value creation in e-business, Strategic Management Journal 22, 2001, pp. 493–520.

[5] J. Ballantine, M. Levy, P. Powel, Evaluating information systems in small and medium-sized enterprises: issues and evidence, European Journal of Information Systems 7, 1998, pp. 241–251.

[6] A. Barua, C.H. Kriebel, T. Mukhopadhyay, Information technology and business value: an analysis and empirical investigation, Information Systems Research 6 (1), 1995, pp. 3–23.

[7] R.C. Beatty, J.P. Shim, M.C. Jones, Factors influencing corporate web site adoption: a time-based assessment, Information and Management 38, 2001, pp. 337–354. [8] E.A. Bush, L. Jarvenpaa, N. Tractinsky, W.H. Glick, External

versus internal perspectives in determining a firm’s progres-sive use of information technology, in: J.I. DeGross, I. Benbasat, G. DeSanctis, C.M. Beath (Eds.), Proceedings of the Twelve International Conference on Information Systems, New York, NY, December 1991, pp. 239–250.

[9] T.A. Byrd, D.E. Turner, An exploratory examination of the relationship between flexible IT infrastructure and competi-tive advantage, Information and Management 39, 2001, pp. 41–52.

[10] K.T. Campbell, D.L. Taylor, Canonical correlation analysis as a general linear model: a heuristic lesson for teachers and students, The Journal of Experimental Education 64 (2), 1996, pp. 157–171.

[11] Y.E. Chan, IT value: the great divide between qualitative and quantitative and individual and organizational measures, Journal of Management Information Systems 16 (4), 2000, pp. 225–261.

[12] M.K. Chang, W. Cheung, Determinants of the intention to use Internet/www at work: a confirmatory study, Information and Management 39, 2001, pp. 1–14.

[13] A. Chaudhury, J.P. Kuilboer, E-Business and E-Commerce Infrastructure, McGraw-Hill, Boston, MA, 2002.

[14] L. Chen, S. Haney, A. Pandzik, J. Spigarelli, C. Jesseman, Small business internet commerce: a case study, Informa-tion Resources Management Journal 16 (3), 2003, pp. 17– 41.

[15] W.W. Chin, A. Gopal, Adoption intention in GSS: rela-tive importance of beliefs, DATA BASE 26 (2–3), 1995, pp. 42–64.

[16] S. Chong, Model of factors on EC adoption and diffusion in SMEs, in: Proceedings of the 1st We-B Conference, Working for E-Business: Challenges of the New e-Conomy, November 2000, Fremantle, Western Australia.

[17] P. Chwelos, I. Benbasat, A. Dexter, Research report: empirical test of an EDI adoption model, Information Systems Research 12 (3), 2001, pp. 304–321.

[18] P.B. Cragg, M. King, Small-firm computing: motivators and inhibitors, MIS Quarterly (March 1993), pp. 47–60. [19] P. Cragg, N. Zinatelli, The evolution of information

systems in small firms, Information and Management 29, 1995, pp. 1–8.

[20] Cyber Atlas, Small business use net for customer service, communications, November 2001, available:http://cyberatlas. internet.com/markets/smallbiz/article/0,10098921821,00.html, accessed on July 2003.

Appendix C. (Continued)

Ease of use EU1 Learning to operate e-commerce would be ease for me EU2 I would find e-commerce to be flexible to interact with

EU3 My interaction with e-commerce would be clear and understandable EU4 It would be ease for me to become skillful at using e-commerce EU5 I would find e-commerce easy to use

Perceived usefulness PU1 Using e-commerce would enable my company to accomplish specific task more quickly

PU2 Using e-commerce would improve my job performance PU3 Using e-commerce in my job would increase my productivity PU4 Using e-commerce would enhance my effectiveness on the job PU5 Using e-commerce would make it easier to do my job

[21] F.D. Davis, Perceived usefulness, perceived ease of use, and user acceptance of information technology, MIS Quarterly (September 1989), pp. 319–340.

[22] F.J. Fowler, Survey Research Methods, second ed., Sage, Thousand Oaks, 1993.

[23] P.E. Green, M.H. Halbert, P.J. Robinson, Canonical analysis: an exposition and illustrative application, Journal and Marketing Research 3, 1966, pp. 32–39.

[24] J.F. Hair, R.E. Anderson, R.L. Tatham, W.C. Black, Multi-variate Data Analysis, Prentice-Hall, New Jersey, 1998. [25] D.A. Harrison, P.P. Mykytyn, C.K. Riemenschneider,

Execu-tive decisions about adoption of information technology in small business: theory and empirical tests, Information Systems Research 8 (2), 1997, pp. 171–195.

[26] A.R. Hendrickson, P.D. Massey, T.P. Cronan, On the test-retest reliability of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use scales, MIS Quarterly (June 1993), pp. 227–230. [27] L.M. Hitt, E. Brynjolfsson, Productivity, business

profit-ability, and consumer surplus: three different measures of information technology value, MIS Quarterly (June 1996), pp. 121–142.

[28] S.I. Huff, M. Wade, M. Parent, S. Schneberger, P. Newson, Cases in Electronic Commerce, McGraw-Hill, Boston, MA, 2000.

[29] A.L. Iacovou, I. Benbasat, A. Dexter, Electronic data interchange and small organizations: adoption and impact of technology, MIS Quarterly (December 1995), pp. 465–485. [30] M. Igbaria, N. Zinatelli, P. Cragg, A. Cavaye, Personal

computing acceptance factors in small firms: a structural equation model, MIS Quarterly (September 1997), pp. 279– 302.

[31] S.L. Jarvenpaa, B. Ives, Executive involvement and partici-pation in the management of IT, MIS Quarterly 15 (2), 1991, pp. 205–227.

[32] A. Kagan, K. Lau, K.R. Nusgart, Information system usage within small business firms, Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice (Spring 1990), pp. 25–37.

[33] A.E. Koh, H.J. Watson, Data management in executive in executive information systems, Information and Management 33, 1998, pp. 301–312.

[34] K. Kuan, P. Chau, A perception-based model of EDI adoption in small businesses using technology–organization–environ-ment framework, Information and Managetechnology–organization–environ-ment 38, 2001, pp. 507–521.

[35] A.L. Lederer, D.J. Maupin, M.P. Sena, Y. Zhuang, The technology acceptance model and the World Wide Web, Decision Support Systems 29, 2000, pp. 269–282.

[36] C.S. Lee, Modeling the business value of information technology, Information and Management 39, 2001, pp. 191–210.

[37] M. Li, L.R. Ye, Information technology and firm per-formance: linking with environmental, strategic and man-agerial contexts, Information and Management 35, 1999, pp. 43–51.

[38] J. Longenecker, C. Moore, J. Petty, Small Business Man-agement: An Entrepreneurial Emphasis, SWC Publishing, 1997.

[39] M.A. Mahmood, G.J. Mann, Measuring the organizational impact of information technology investment: an exploratory study, Journal of Management Information Systems 10 (1), 1993, pp. 97–122.

[40] S.C. Malone, Computerizing small business information systems, Journal of Small Business Management (April 1985), pp. 10–16.

[41] J. Mehrtens, P.B. Cragg, A.M. Mills, A model of Internet adoption by SMEs, Information and Management 39, 2001, pp. 165–176.

[42] A.A. Mirchandani, J. Motwani, Understanding small business electronic commerce adoption: an empirical analy-sis, Journal of Computer Information Systems (Spring 2001), pp. 70–73.

[43] H.A. Napier, P.J. Judd, O.N. Rivers, S.W. Wagner, Creating a Winning E-Business, Course Technology, Boston, MA, 2001. [44] E.W.T. Ngai, F.K.T. Wat, A literature review and classifica-tion of electronic commerce research, Informaclassifica-tion and Management 39, 2002, pp. 415–429.

[45] J.C. Nunnally, Psychometric Theory, McGraw-Hill, New York, 1978.

[46] S. Poon, P.M.C. Swatman, An exploratory study of small business Internet commerce issues, Information and Manage-ment 35, 1999, pp. 9–18.

[47] J.H. Pratt, E-Biz: strategies for small business success, US SBA Office of Advocacy, October 2002.

[48] G. Premkumar, M. Potter, Adoption of computer aided software engineering (CASE) technology: an innovation adoption perspective, DATA BASE 26 (2–3), 1995, pp. 105–123.

[49] G. Premkumar, M. Roberts, Adoption of new information technologies in rural small businesses, OMEGA, The International Journal of Management Science 27, 1999, pp. 467–484.

[50] S. Purao, S. Campbell, Critical concerns for small business electronic commerce: some reflections based on interviews of small business owners, in: Proceedings of the AIS Con-ference, 1998, Baltimore, MD.

[51] L. Raymond, Organizational characteristics and MIS success in the context of small business, MIS Quarterly (March 1985), pp. 37–52.

[52] Realizing the potential of electronic commerce for SMEs in the global economy, in: Proceedings of the SME Conference of Business Symposium Roundtable on Electronic Commerce and SMEs. Bologna, June 2000.

[53] B.H. Reich, I. Benbasat, An empirical investigation of factors influencing the success of customer-oriented strategic systems, Information Systems Research 1 (3), 1990, pp. 325– 347.

[54] C.K. Riemenschneider, V.R. McKinney, Assessing belief differences in small business adopters and non-adopters of web-based e-commerce, Journal of Computer Information Systems (2001–2002), pp. 101–107.

[55] C.K. Riemenschneider, D.A. Harrison, P.P. Mykytyn, Under-standing IT adoption decisions in small business: integrating current theories, Information and Management 40, 2003, pp. 269–285.

[56] G. Saloner, A.M. Spence, Creating and Capturing Value, Perspectives and Cases on Electronic Commerce, Wiley, New York, 2002.

[57] G.L. Sanders, J.F. Courtney, A field study of organizational factors influencing DSS success, MIS Quarterly 9 (1), 1985, pp. 77–93.

[58] G.P. Schneider, J.T. Perry, Electronic Commerce, Course Technology, Cambridge, MA, 2000.

[59] G.H. Subramanian, A replication of perceived usefulness and perceived ease of use measurement, Decision Science 25 (5– 6), 1998, pp. 863–874.

[60] G.H. Subramanian, J.T. Nosek, An empirical study of the measurement and instrument validation of perceived strategy value of information systems, Journal of Computer Informa-tion Systems (Spring 2001), pp. 64–69.

[61] B. Szajna, Software evaluation and choice: predictive validation of the technology acceptance instrument, MIS Quarterly (September 1994), pp. 319–324.

[62] P.P. Tallon, K.L. Kraemer, V. Gurbaxani, Executives’ perceptions of the business value of information technology: a process-oriented approach, Journal of Management Infor-mation Systems (Spring 2000), pp. 145–173.

[63] J.Y.L. Thong, An integrated model of information systems adoption in small businesses, Journal of Management Information Systems 15 (4), 1999, pp. 187–214.

[64] J.Y.L. Thong, Resource constraints and information systems implementation in Singaporean small businesses, OMEGA 29, 2001, pp. 143–156.

[65] V. Venkatesh, F.D. Davis, A model of the antecedents of perceived ease of use: development and test, Decision Sciences 27 (3), 1996, pp. 451–481.

[66] J.A. Welsh, J.F. White, A small business is not a little big business, Harvard Business Review (July–August 1981), pp. 18–32.

Elizabeth E. Grandon is an assistant professor at the school of Business Administration at the Emporia State University. She is currently a doctoral candidate at Southern Illinois University where she received her MBA in Manage-ment Information Systems. Her research interests include database management, technology acceptance, e-commerce and information technology adoption in small businesses. Her research has been published inCommunications of AIS,Journal of Computer Information Systems,Journal of Global Information Technology Management, and various national and international conference proceedings.