Australia • Brazil • Canada • Mexico • Singapore • Spain • UnitedKingdom • UnitedStates

Organization Development & Change

9e

Thomas G. Cummings

University of Southern California

Christopher G. Worley

9th Edition

Thomas G. Cummings & Christopher G. Worley

Vice President of Editorial, Business: Jack W. Calhoun

Vice President/Editor-in-Chief: Melissa Acuña Executive Editor: Joe Sabatino

Developmental Editor: Denise Simon Marketing Manager: Clint Kernen Content Project Manager: D. Jean Buttrom Manager of Technology, Editorial: John Barans Media Editor: Rob Ellington

Website Project Manager: Brian Courter Frontlist Buyer, Manufacturing: Doug Wilke Production Service: Integra Software Services, Pvt., Ltd.

Sr. Art Director: Tippy McIntosh

Cover and Internal Designer: Mike Stratton, Stratton Design

Cover Image: Chad Baker, Getty Images

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means— graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution, information storage and retrieval systems, or in any other manner—except as may be permitted by the license terms herein.

For product information and technology assistance, contact us at Cengage Learning Customer & Sales Support, 1-800-354-9706

For permission to use material from this text or product, submit all requests online at www.cengage.com/permissions

Further permissions questions can be emailed to permissionrequest@cengage.com

ExamView® is a registered trademark of eInstruction Corp. Windows is a registered trademark of the Microsoft Corporation used herein under license. Macintosh and Power Macintosh are registered trademarks of Apple Computer, Inc. used herein under license.

© 2008 Cengage Learning. All Rights Reserved. Library of Congress Control Number: 1234567890 Student Edition ISBN 13: 978-0-324-42138-5 Student Edition ISBN 10: 0-324-42138-9 Instructor’s Edition ISBN 13: 978-0-324-58054-9 Instructor’s Edition ISBN 10: 0-324-58058-1 South-Western Cengage Learning 5191 Natorp Boulevard

Mason, OH 45040 USA

Cengage Learning products are represented in Canada by Nelson Education, Ltd.

For your course and learning solutions, visit academic.cengage.com Purchase any of our products at your local college store or at our preferred online store www.ichapters.com

Printed in Canada

Dedication

iv

brief contents

Preface xv

CHAPTER 1

General Introduction to Organization

Development 1

PART 1

Overview of Organization Development 22

CHAPTER 2

The Nature of Planned Change 23

CHAPTER 3

The Organization Development

Practitioner 46

PART 2

The Process of Organization Development 74

CHAPTER 4

Entering and Contracting 75

CHAPTER 5

Diagnosing Organizations 87

CHAPTER 6

Diagnosing Groups and Jobs 107

CHAPTER 7

Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic

Information 121

CHAPTER 8

Feeding Back Diagnostic Information 139

CHAPTER 9

Designing Interventions 151

CHAPTER 10

Leading and Managing Change 163

CHAPTER 11

Evaluating and Institutionalizing

Organization Development Interventions 189

PART 3

Human Process Interventions 252

CHAPTER 12

Interpersonal and Group Process

Approaches 253

CHAPTER 13

Organization Process Approaches 276

PART 4

Strategic Change Interventions 504

CHAPTER 20

Special Applications of Organization

Development 613

CHAPTER 23

Organization Development in Global

Settings 614

CHAPTER 24

Organization Development in Nonindustrial Settings: Health Care, School Systems, the Public Sector, and Family-Owned Businesses 651

CHAPTER 25

Future Directions in Organization

Development 693 Glossary 746

Name Index 756

v

Preface xv

CHAPTER 1

General Introduction to Organization Development 1

Organization Development Defined 1

The Growth and Relevance of Organization Development 4

A Short History of Organization Development 6

Laboratory Training Background 6

Action Research and Survey Feedback Background 8

Normative Background 9

Productivity and Quality-of-Work-Life Background 11

Strategic Change Background 12

Evolution in Organization Development 12

Overview of The Book 14

Summary 17

Notes 17

PART 1

Overview of OrganizationDevelopment 22

CHAPTER 2

The Nature of Planned Change 23

Theories of Planned Change 23

Lewin’s Change Model 23

Action Research Model 24

The Positive Model 27

Comparisons of Change Models 29

General Model of Planned Change 29

Entering and Contracting 29

Diagnosing 30

Planning and Implementing Change 30 Evaluating and Institutionalizing Change 31

Different Types of Planned Change 31

Magnitude of Change 31

Application 2-1 Planned Change at the San Diego County

Regional Airport Authority 32

Degree of Organization 35

Application 2-2 Planned Change in an Underorganized System 37 Domestic vs. International Settings 40

Critique of Planned Change 41

Conceptualization of Planned Change 41

Practice of Planned Change 42

Summary 43

Notes 44

CHAPTER 3

The Organization Development Practitioner 46

Who is the Organization Development Practitioner? 46

Competencies of an Effective Organization Development Practitioner 48

The Professional Organization Development Practitioner 53 Role of Organization Development Professionals 53

Application 3-1 Personal Views of the Internal and External

Consulting Positions 56

Careers of Organization Development Professionals 59

Professional Values 60

Professional Ethics 61

Ethical Guidelines 61

Ethical Dilemmas 62

Application 3-2 Kindred Todd and the Ethics of OD 65

Summary 66

Notes 67

Appendix 70

PART 2

The Process of Organization Development 74

CHAPTER 4

Entering and Contracting 75

Entering into an OD Relationship 76

Clarifying the Organizational Issue 76

Determining the Relevant Client 76

Selecting an OD Practitioner 77

Developing a Contract 79

Mutual Expectations 79

Application 4-1 Entering Alegent Health 80

Time and Resources 81

Ground Rules 81

Interpersonal Process Issues in Entering and Contracting 81

Application 4-2 Contracting with Alegent Health 82

Summary 86

Notes 86

CHAPTER 5

Diagnosing Organizations 87

What is Diagnosis? 87

The Need for Diagnostic Models 88

Open Systems Model 89

Organizations as Open Systems 89

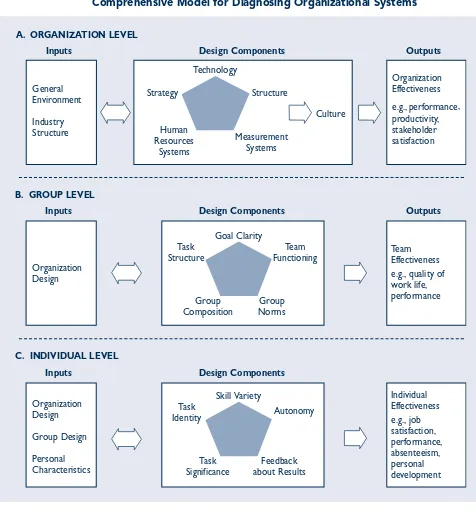

Diagnosing Organizational Systems 92

Organization-Level Diagnosis 94

Organization Environments and Inputs 94

Design Components 96

Outputs 99

Alignment 99

Analysis 99

Application 5-1 Steinway’s Strategic Orientation 100

Summary 105

vii

Contents

CHAPTER 6

Diagnosing Groups and Jobs 107

Group-Level Diagnosis 107

Inputs 107

Design Components 108

Outputs 109

Fits 110

Analysis 110

Application 6-1 Top-Management Team at Ortiv Glass Corporation 111

Individual-Level Diagnosis 113

Inputs 113

Design Components 114

Fits 115

Analysis 115

Application 6-2 Job Design at Pepperdine University 116

Summary 119

Notes 120

CHAPTER 7

Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic Information 121

The Diagnostic Relationship 121

Methods for Collecting Data 123

Questionnaires 124

Interviews 126

Observations 127

Unobtrusive Measures 128

Sampling 129

Techniques for Analyzing Data 130

Qualitative Tools 130

Application 7-1 Collecting and Analyzing Diagnostic Data at Alegent Health 132

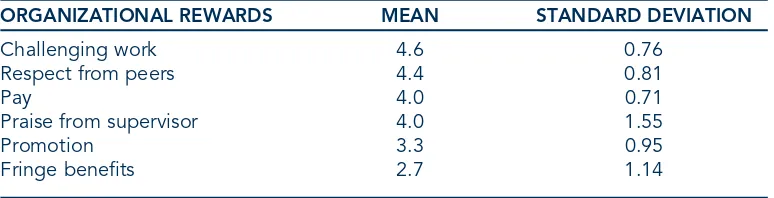

Quantitative Tools 133

Summary 137

Notes 138

CHAPTER 8

Feeding Back Diagnostic Information 139

Determining the Content of the Feedback 139

Characteristics of the Feedback Process 141

Survey Feedback 142

What Are the Steps? 142

Application 8-1 Training OD Practitioners in Data Feedback 143 Survey Feedback and Organizational Dependencies 145

Application 8-2 Operations Review and Survey Feedback at

Prudential Real Estate Affiliates 146

Limitations of Survey Feedback 147

Results of Survey Feedback 148

Summary 149

Notes 149

CHAPTER 9

Designing Interventions 151

What are Effective Interventions? 151

How to Design Effective Interventions 152

Overview of Interventions 156

Human Process Interventions 156

Summary 161

Notes 162

CHAPTER 10

Leading and Managing Change 163

Overview of Change Activities 163

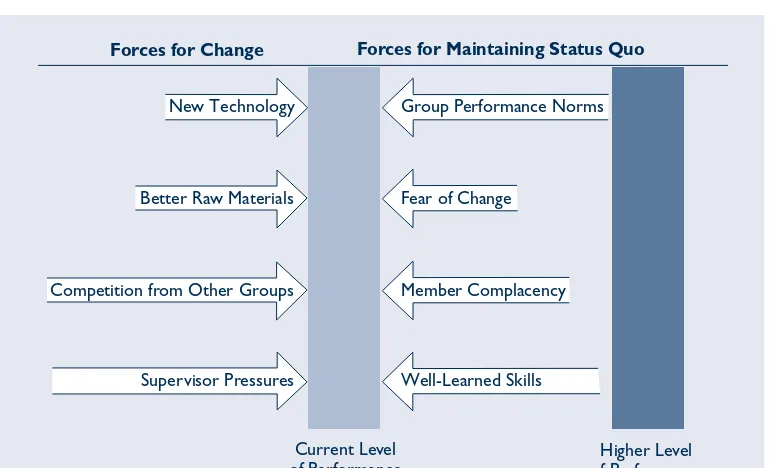

Motivating Change 165

Creating Readiness for Change 165

Overcoming Resistance to Change 166

Application 10-1 Motivating Change in the Sexual Violence Prevention

Unit of Minnesota’s Health Department 168

Creating a Vision 169

Describing the Core Ideology 170

Constructing the Envisioned Future 171

Developing Political Support 171

Application 10-2 Creating a Vision at Premier 172

Assessing Change Agent Power 174

Identifying Key Stakeholders 175

Influencing Stakeholders 175

Managing the Transition 176

Application 10-3 Developing Political Support for the Strategic

Planning Project in the Sexual Violence Prevention Unit 177

Activity Planning 178

Commitment Planning 179

Change-Management Structures 179

Learning Processes 179

Sustaining Momentum 180

Application 10-4 Transition Management in the HP–Compaq Acquisition 181

Providing Resources for Change 182

Building a Support System for Change Agents 183 Developing New Competencies and Skills 183

Reinforcing New Behaviors 183

Staying the Course 184

Summary 184

Notes 185

Application 10-5 Sustaining Transformational Change at

the Veterans Health Administration 187

CHAPTER 11

Evaluating and Institutionalizing Organization

Development Interventions 189

Evaluating Organization Development Interventions 189 Implementation and Evaluation Feedback 189

Measurement 192

Research Design 197

Institutionalizing Organizational Changes 200

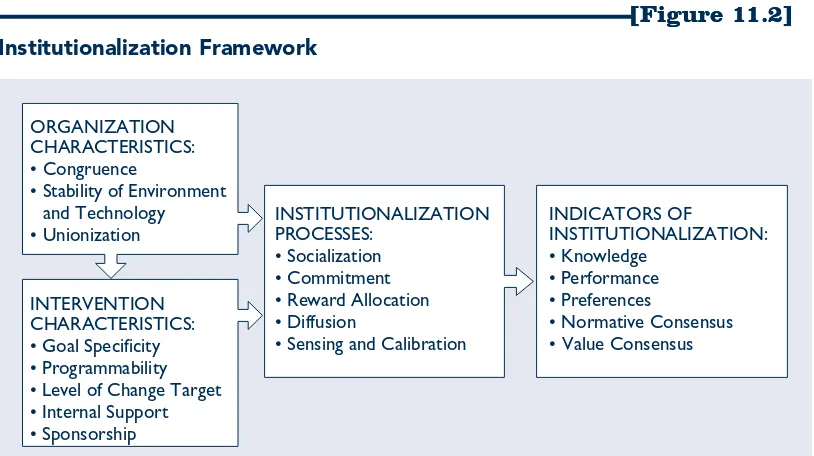

Institutionalization Framework 200

Application 11-1 Evaluating Change at Alegent Health 201

Organization Characteristics 203

Intervention Characteristics 204

Institutionalization Processes 205

Indicators of Institutionalization 206

Application 11-2 Institutionalizing Structural Change at Hewlett-Packard 208

ix

Contents

Notes 210

Selected Cases 212

Kenworth Motors 212

Peppercorn Dining 217

Sunflower Incorporated 239

Initiating Change in the Manufacturing and Distribution Division of PolyProd 241 Evaluating the Change Agent Program at Siemens Nixdorf (A) 247

PART 3

Human Process Interventions 252

CHAPTER 12

Interpersonal and Group Process Approaches 253

Process Consultation 253

Group Process 254

Basic Process Interventions 255

Results of Process Consultation 257

Application 12-1 Process Consultation at Action Company 258

Third-Party Interventions 259

An Episodic Model of Conflict 260

Facilitating the Conflict Resolution Process 261

Application 12-2 Conflict Management at Balt Healthcare Corporation 262

Team Building 263

Team-Building Activities 264

Activities Relevant to One or More Individuals 267 Activities Oriented to the Group’s Operation and Behavior 268 Activities Affecting the Group’s Relationship with the Rest

of the Organization 268

Application 12-3 Building the Executive Team at Caesars Tahoe 269 The Manager’s Role in Team Building 270

The Results of Team Building 271

Summary 273

Notes 273

CHAPTER 13

Organization Process Approaches 276

Organization Confrontation Meeting 276

Application Stages 276

Results of Confrontation Meetings 277

Application 13-1 A Work-Out Meeting at General

Electric Medical Systems Business 278

Intergroup Relations Interventions 279

Microcosm Groups 279

Application Stages 280

Resolving Intergroup Conflict 281

Large-Group Interventions 284

Application 13-2 Improving Intergroup Relationships

in Johnson & Johnson’s Drug Evaluation Department 285

Application Stages 287

Application 13-3 Using the Decision Accelerator to Generate

Innovative Strategies in Alegent’s Women’s and Children’s Service Line 290 Results of Large-Group Interventions 294

Summary 295

Notes 295

Selected Cases 297

PART 4

Technostructural Interventions 314

CHAPTER 14

Restructuring Organizations 315

Structural Design 315

The Functional Structure 316

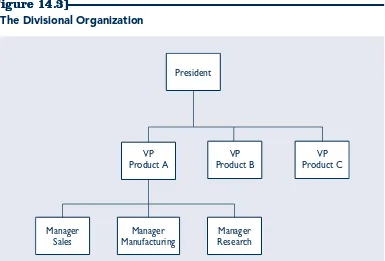

The Divisional Structure 318

The Matrix Structure 319

The Process Structure 322

The Customer-Centric Structure 324

Application 14-1 Healthways’ Process Structure 325

The Network Structure 328

Downsizing 331

Application 14-2 Amazon.com’s Network Structure 332

Application Stages 334

Results of Downsizing 337

Application 14-3 Strategic Downsizing at Agilent Technologies 338

Reengineering 340

Application Stages 341

Application 14-4 Honeywell IAC’s Totalplant™ Reengineering Process 344

Results from Reengineering 346

Summary 346

Notes 347

CHAPTER 15

Employee Involvement 350

Employee Involvement: What Is It? 350

A Working Definition of Employee Involvement 351 The Diffusion of Employee Involvement Practices 352 How Employee Involvement Affects Productivity 352

Employee Involvement Applications 354

Parallel Structures 354

Application 15-1 Using the AI Summit to Build

Union–Management Relations at Roadway Express 356

Total Quality Management 359

Application 15-2 Six-Sigma Success Story at GE Financial 365

High-Involvement Organizations 367

Application 15-3 Building a High-Involvement Organization

at Air Products and Chemicals, Inc. 370

Summary 373

Notes 373

CHAPTER 16

Work Design 376

The Engineering Approach 376

The Motivational Approach 377

The Core Dimensions of Jobs 378

Individual Differences 379

Application Stages 380

Barriers to Job Enrichment 382

Application 16-1 Enriching Jobs at the Hartford’s Employee

Relations Consulting Services Group 383

Results of Job Enrichment 385

The Sociotechnical Systems Approach 386

Conceptual Background 387

xi

Contents

Application Stages 391

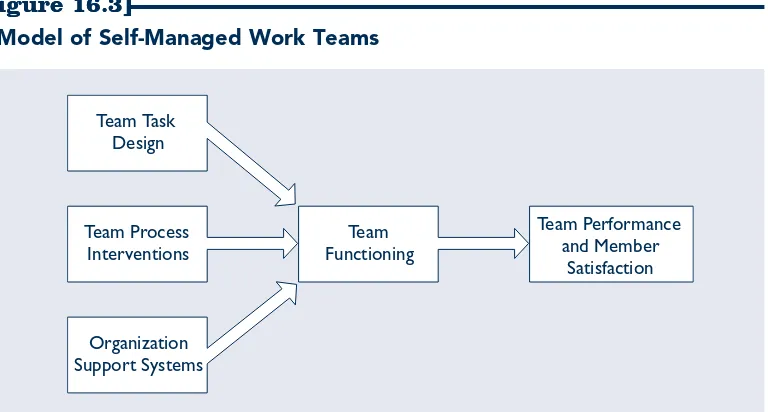

Results of Self-Managed Teams 393

Application 16-2 Moving to Self-Managed Teams at ABB 394

Designing Work for Technical and Personal Needs 397

Technical Factors 398

Personal-Need Factors 399

Meeting Both Technical and Personal Needs 400

Summary 401

Notes 402

Selected Cases 405

City of Carlsbad, California: Restructuring the Public Works Department (A) 405 C&S Wholesale Grocers: Self-Managed Teams 408

PART 5

Human Resource Management Interventions 419

CHAPTER 17

Performance Management 420

A Model of Performance Management 421

Goal Setting 422

Characteristics of Goal Setting 422

Establishing Challenging Goals 423

Clarifying Goal Measurement 423

Application Stages 424

Management by Objectives 424

Effects of Goal Setting and MBO 426

Performance Appraisal 426

Application 17-1 The Goal-Setting Process at Siebel Systems 427 The Performance Appraisal Process 428

Application Stages 430

Effects of Performance Appraisal 431

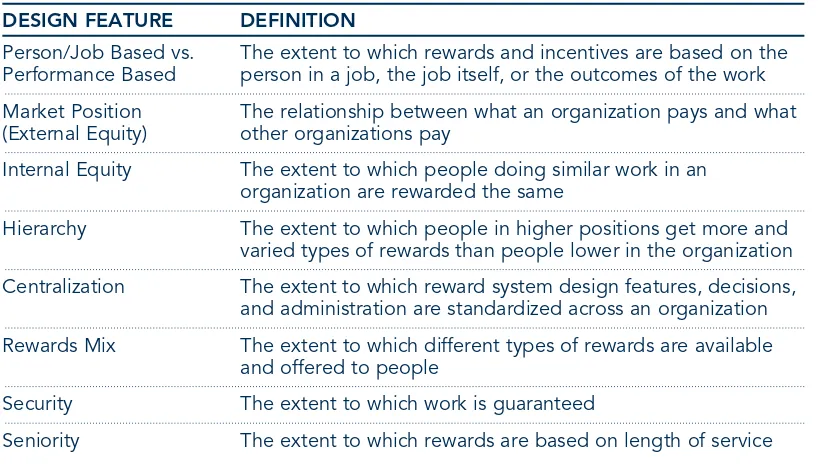

Reward Systems 431

Application 17-2 Adapting the Appraisal Process at Capital

One Financial 432

Structural and Motivational Features of Reward Systems 434 Skill- and Knowledge-Based Pay Systems 437

Performance-Based Pay Systems 438

Gain-Sharing Systems 440

Promotion Systems 442

Reward-System Process Issues 443

Application 17-3 Revising the Reward Systemat Lands’ End 444

Summary 447

Notes 447

CHAPTER 18

Developing Talent 451

Coaching and Mentoring 451

What Are the Goals? 452

Application Stages 452

The Results of Coaching and Mentoring 453

Career Planning and Development Interventions 453

What Are the Goals? 454

Application Stages 455

The Results of Career Planning and Development 463

Management And Leadership Development Interventions 463

Application 18-1 PepsiCo’s Career Planning and Development Framework 464

What Are the Goals? 466

Application 18-2 Leading Your Business at Microsoft Corporation 468 The Results of Development Interventions 469

Summary 469

Notes 470

CHAPTER 19

Managing Workforce Diversityand Wellness 473

Workforce Diversity Interventions 473

What Are the Goals? 473

Application Stages 475

The Results for Diversity Interventions 478

Employee Stress and Wellness Interventions 479

What Are the Goals? 479

Application 19-1 Embracing Employee Diversity at Baxter Export 480

Applications Stages 481

The Results of Stress Management and Wellness Interventions 486

Summary 487

Notes 488

Application 19-2 Johnson & Johnson’s Health and Wellness Program 490

Selected Cases 492

Employee Benefits at HealthCo 492

Sharpe BMW 497

PART 6

Strategic Change Interventions 504

CHAPTER 20

Transformational Change 505

Characteristics of Transformational Change 505

Change Is Triggered by Environmental and Internal Disruptions 506 Change Is Aimed at Competitive Advantage 506 Change Is Systemic and Revolutionary 507 Change Demands a New Organizing Paradigm 508 Change Is Driven by Senior Executives and Line Management 508 Change Involves Significant Learning 509

Integrated Strategic Change 509

Organization Design 512

Application 20-1 Managing Strategic Change at Microsoft Canada 513

Conceptual Framework 515

Culture Change 518

Application 20-2 Organization Design at Deere & Company 519 Concept of Organization Culture 520 Organization Culture and Organization Effectiveness 521 Diagnosing Organization Culture 523

The Behavioral Approach 523

The Competing Values Approach 524

The Deep Assumptions Approach 525

Summary 528

Notes 529

Application 20-3 Culture Change at IBM 533

CHAPTER 21

Continuous Change 535

Self-Designing Organizations 535

The Demands of Adaptive Change 536

Application Stages 536

Learning Organizations 538

xiii

Contents

Application 21-1 Self-Design at American Healthways Corporation 539 Organization Learning Interventions 542 Knowledge Management Interventions 547

Outcomes of OL and KM 550

Application 21-2 Implementing a Knowledge Management

System at Motorola Penang 551

Built-To-Change Organizations 553

Design Guidelines 553

Application Stages 554

Summary 556

Notes 556

Application 21-3 Creating a Built-to-Change Organizationat

Capital One Financial 559

CHAPTER 22

Transorganizational Change 561

Transorganizational Rationale 562

Mergers and Acquisitions 563

Application Stages 564

Strategic Alliance Interventions 568

Application Stages 568

Application 22-1 The Sprint and Nextel Merger: The First Two Years 569

Network Interventions 571

Application 22-2 Building Alliance Relationships 572

Creating the Network 574

Managing Network Change 577

Application 22-3 Fragile and Robust—Network Change

in Toyota Motor Corporation 580

Summary 582

Notes 583

Selected Cases 586

Fourwinds Marina 586

Leading Strategic Change at DaVita: The Integration of the Gambro Acquisition 597

PART 7

Special Applications of Organization Development 613

CHAPTER 23

Organization Development in Global Settings 614 Organization Development Outside the United States 615

Cultural Context 616

Economic Development 618

How Cultural Context and Economic Development Affect OD Practice 619

Application 23-1 Modernizing China’s Human Resource

Development and Training Functions 623

Worldwide Organization Development 625

Worldwide Strategic Orientations 626 The International Strategic Orientation 627 The Global Strategic Orientation 629 The Multinational Strategic Orientation 631

Application 23-2 Implementing the Global Strategy: Changing the Culture

of Work in Western China 632

The Transnational Strategic Orientation 636

Global Social Change 639

Global Social Change Organizations 640

Application Stages 641

Application 23-3 Social and Environmental Change at Floresta 645

Summary 647

Notes 647

CHAPTER 24

Organization Developmentin Nonindustrial Settings: Health Care,

School Systems, the Public Sector, and Family-Owned Businesses 651

Organization Development in Health Care 651

Trends in Health Care 652

Opportunities for Organization Development Practice 655 Success Principles for OD in Health Care 657

Conclusions 658

Organization Development in School Systems 659

Education: Industrial-Age Roots 659 Changing Conditions Cause Stress 659

Disappointing Reform Efforts 660

A New Metaphor for Schools 662

Future Opportunities for OD Practice 664 Technology’s Unique Role in School OD 665

Conclusions 667

Organization Developmentin the Public Sector 667

Comparing Public- and Private-Sector Organizations 669 Recent Research and Innovations in Public-Sector

Organizational Development 674

Conclusions 675

Organization Development in Family-Owned Businesses 675

The Family Business System 676

Family Business Developmental Stages 679

A Parallel Planning Process 680

Values 680

Critical Issues in Family Business 681 OD Interventions in Family Business System 684

Summary 688

Notes 689

CHAPTER 25

Future Directions in Organization Development 693

Trends within Organization Development 693

Traditional 693

Pragmatic 694

Scholarly 695

Implications for OD’s Future 695

Trends in the Context of Organization Development 697

The Economy 697

The Workforce 700

Organizations 701

Implications for OD’s Future 702

Summary 708

Notes 709

Integrative Cases 712

B. R. Richardson Timber Products Corporation 712 Building the Cuyahoga River Valley Organization* 728 Black & Decker International: Globalization of the Architectural Hardware Line 738

Glossary 746

Name Index 756

xv In preparing this new edition, we were struck by how the cliché of “living in changing

times” is becoming almost ironic. The events of each day remind us that things are mov-ing far more quickly and unpredictably than we could ever have imagined. Consider the U.S. economic turmoil brought on by the mortgage- lending crisis and the record price of crude oil, which seemingly rises independent of consumption. Or think about the run-up to the 2008 U.S. presidential election. It strikes us as just a bit surreal to see the word CHANGE plastered on the speaker’s podium and waved by supporters every time Barack Obama comes out to speak. Not to be outdone, Hillary Clinton’s key selling point is her emphasis that she has the ability to lead change. By the time the next edition of this book comes out, a new president will be well into her or his first term and we will no doubt have experienced a lot of change.

Nor is change confined to the United States. As we write this, the new prime min-ister of France is shaking up that country’s work rules, organizations, and policies. Beijing is preparing to host the Olympic Games and show the world a whole new China. Countries in Africa are dealing with drought, AIDS, military dictatorships, and the emergence of democracy. The war in Iraq remains a point of contention among many, and the Middle East remains embroiled in controversy and seemingly intrac-table problems.

Nor is change restricted to governments and organizations. Our personal lives are embedded in change and the dilemmas it poses. Individuals and families are finding that the pace of change exceeds their physical and mental capacity to cope with it. As people experience change accelerating, they tend to feel overwhelmed and alienated. They experience what sociologists call “anomie,” a state of being characterized by the lack of social norms or anchors of stable and shared values. Many Americans, for example, want more time with their families but feel compelled to work longer hours, make more money, and satisfy escalating needs; they espouse diversity but push other cultures to do it “the American way”; they argue that technology will find an answer to the global warming problem and so justify acquiring a Hummer.

Nor is change limited to social systems and their environments. Organization Development—the field of planned change itself—is changing. In a time of unprec-edented change, our views of how and when planned change occurs, who leads and controls it, and what contributes to its success are all changing. Since the last edition of this text, three OD handbooks have been published, a special issue of the Journal of Applied Behavioral Science has been devoted to “reinvigorate OD” and another special issue on international OD is on its way, and volumes on change management and organization transformation have continued to flood the bookstores. Conversations among OD practitioners and scholars about where the field is and should be headed have become more vigorous. The drive to understand and do something about change continues unabated.

In times like these, books on OD and change have never been more relevant and necessary. For our part, this is the ninth edition of the market-leading text in the field. OD is an applied field of change that uses behavioral science knowledge to increase

the capacity for change, and to improve the functioning and performance of organiza-tions. OD is more than change management, however, and the field would do well to differentiate itself from the mechanistic, programmatic assumptions that organization change can simply be scripted by various methods of “involving” people and “enroll-ing” them in the change. OD is not concerned about change for change’s sake, a way to implement the latest fad, or a pawn for doing management’s bidding. It is about learning and improving in ways that make individuals, groups, organizations, and ultimately the world better off and more capable of managing change in the future. Moreover, OD is more than a set of values. It is not a front for the promulgation of humanistic and spiritual beliefs nor a set of interventions that boil down to “holding hands and singing Kumbaya.” It is a set of testable ideas and practices about how social and technical systems can coexist to produce individual satisfaction and sustainable organizational results. Finally, OD is more than a set of tools and techniques. It is not a bunch of “interventions” looking to be applied in whatever organization that comes along. It is an integrated theory and practice aimed at increasing the effectiveness of organizations.

In today’s reality, OD is often misunderstood and its relevance questioned. As men-tioned above, OD is often used synonymously with change management; it is often defined and overly constrained by its association with a set of “touchy-feely” values; and it is often described as a hammer looking for a nail. As a result, it is open to discus-sion whether OD is up to the task of facilitating the changes that organizations need to exist and thrive in the world today. This is OD’s challenge in the decade and century ahead. Can it implement change and teach the system to change itself at the same time? Will it cling to its humanistic traditions and focus on functioning or increase its relevance by integrating more performance-related values? How will OD incorporate values related to globalization, cultural integration, the concentration of wealth, and environmental sustainability? Can it afford not to address the issues that threaten an organization’s survival? These are heady questions for a field barely 55 years old.

The original edition of this text, authored by OD pioneer Edgar Huse in 1975, became a market leader because it faced the relevance issue. It took an objective, research perspective and placed OD practice on stronger theoretical footing. Ed showed that, in some cases, OD did produce meaningful results but that additional work was still needed. Sadly, Ed passed away following the publication of the second edition. His wife, Mary Huse, asked Tom Cummings to revise the book for subsequent editions. With the fifth edition, Tom asked Chris Worley to work with him in writing the text.

The most recent editions have had an important influence on the perception of OD. While maintaining the book’s strengths of even treatment and unbiased report-ing, the newer editions made even larger strides in placing OD on a strong theoretical foundation. They broadened the scope and increased the relevance of OD by includ-ing interventions that had a content component, includinclud-ing work design, employee involvement, and organization structure. They took another step toward relevance and suggested that OD had begun to incorporate a strategic perspective. This strategic orientation proposed that OD could be as concerned with performance issues as it was with human potential. Effective OD, from this newer perspective, relied as much on knowledge about organization theory and econo mics as it did on the behavioral sci-ences. It is our greatest hope that the current edition continues this tradition of rigor and relevance.

REVISIONS TO THE NINTH EDITION

xvii

Strategic Emphasis

In keeping with the increasingly strategic focus of OD, we have expanded the strategic interventions part of the book from two chapters to three chapters. Chapter 20 now describes transformational change and focuses on the interventions and processes associated with episodic forms of large-scale change. There is a whole new section on organization redesign interventions. Chapter 21 is devoted to describing continuous change in organizations, with a new section on built-to-change organizations. Finally, Chapter 22 now combines interventions about multiple organizations, including trans-organizational development, mergers and acquisitions, joint ventures, and networks.

Human Resources Interventions

In addition, the human resources interventions part of the text has been completely reorganized and revised. The original two chapters have been expanded to three chap-ters. While we retained the performance management chapter, there is a new chapter on developing talent (Chapter 18) that includes training, leadership development, career management, and coaching. Chapter 19 has been refocused on managing work-force diversity, wellness, and stress.

Key Chapter Revisions

Other chapters have received important updates and improvements. In Chapter 14— “Restructuring Organizations”—a new section on “customer-centric” organizations was added to reflect important advances in this area. In Chapter 24—“OD in Health Care, School Systems, the Public Sector, and Family-Owned Businesses”—each sec-tion has been completely re-written by new guest authors. Finally, Chapter 25—“Future Directions in Organization Development”—has received a thorough revision based on the authors’ recent research.

DISTINGUISHING PEDAGOGICAL FEATURES

The text is designed to facilitate the learning of OD theory and interventions. We maintained the chapter sequence from the previous edition. Based on feedback from reviewers, this format more closely matches the OD process. Instructors can teach the process and then link OD practice to the interventions.

Organization

The ninth edition is organized into seven parts. Following an introductory chapter that describes the definition and history of OD, Part 1 provides an overview of orga-nization development. It discusses the fundamental theories that underlie planned change (Chapter 2) and describes the people who practice it (Chapter 3). Part 2 is an eight-chapter description of the OD process. It describes how OD practitioners enter and contract with client systems (Chapter 4); diagnose organizations, groups, and jobs (Chapters 5 and 6); collect, analyze, and feedback diagnostic data (Chapters 7 and 8); design interventions (Chapter 9); lead and manage change (Chapter 10); and evaluate and institutionalize change (Chapter 11). In this manner, professors can focus on the OD process without distraction. Parts 3, 4, 5, and 6 then cover the major OD interven-tions used today according to the same classification scheme used in previous ediinterven-tions of the text. Part 3 covers human process interventions; Part 4 describes technostruc-tural approaches; Part 5 presents interventions in human resources management; and Part 6 addresses strategic change interventions. In the final section, Part 7, we cover special applications of OD, including international OD (Chapter 23); OD in health care, family businesses, schools, and the public sector (Chapter 24); and the future of

OD (Chapter 25). We believe this ordering provides professors with more flexibility in teaching OD.

Applications

Within each chapter, we describe actual situations in which different OD techniques or interventions were used. These applications provide students with a chance to see how OD is actually practiced in organizations. In the ninth edition, more than 33% of the applications are new and many others have been updated to maintain the text’s currency and relevance. In response to feedback from reviewers, almost all of the applications describe a real situation in a real organization (although sometimes we felt it necessary to use disguised names). In many cases, the organizations are large public companies that should be readily recognizable. We have endeavored to write applications based on our own OD practice or that have appeared in the popular literature. In addition, we have asked several of our students to submit descriptions of their own practice and these applications appear throughout the text. The time and effort to produce these vignettes of OD practice for others is gratefully acknowledged.

Cases

At the end of each major part in the book, we have included cases to permit a more in-depth discussion of the OD process. Seven of the 16 cases are new to the ninth edi-tion. We have kept some cases that have been favorites over the years but have also replaced some of the favorites with newer ones. Also in response to feedback from users of the text, we have endeavored to provide cases that vary in levels of detail, complexity, and sophistication to allow the professor some flexibility in teaching the material to either undergraduate or graduate students.

Internet Resources

Throughout the book, we have tried to provide references to the Internet, particularly to sites related to the organizations discussed. Although these sites are often updated, moved, or altogether abandoned (so we cannot guarantee that the links will be main-tained as cited), these provide students with an opportunity to explore the information available on the Internet.

Audience

This book can be used in a number of different ways and by a variety of people. First, it serves as a primary textbook in organization development for students at both the undergraduate and graduate levels. Second, the book can also serve as an independent study guide for individuals wishing to learn more about how organization develop-ment can improve productivity and human satisfaction. Third, the book is intended to be of value to OD professionals, executives and administrators, specialists in such fields as personnel, training, occupational stress, and human resources management, and anyone interested in the complex process known as organization development.

EDUCATIONAL AIDS AND SUPPLEMENTS

Instructor’s Manual with Test Bank (ISBN: 0-324-58057-6)

xix

Chapter Objectives and Lecture Notes For each chapter, summary learning objec-tives provide a quick orientation to the chapter’s material. The material in the chapter is then outlined and comments are made concerning important pedagogical points, such as crucial assumptions that should be noted for students, important aspects of practical application, and alternative points of view that might be used to enliven class discussion.

Exam Questions A variety of multiple choice, true/false, and essay questions are suggested for each chapter. Instructors can use these questions directly or to suggest additional questions reflecting the professor’s own style.

Case Notes For each case in the text, teaching notes have been developed to assist instructors in preparing for case discussions. The notes provide an outline of the case, suggestions about where to place the case during the course, discussion questions to focus student attention, and an analysis of the case situation. In combination with the professor’s own insights, the notes can help to enliven the case discussion or role plays.

Audiovisual Materials Finally, a list is included of films, videos, and other materials that can be used to supplement different parts of the text, along with the addresses and phone numbers of vendors that supply the materials.

Instructor’s Resource CD-ROM (0-324-58058-4)

Key instructor ancillaries (Instructor’s Manual, Test Bank, ExamView, and PowerPoint slides) are provided on CD-ROM, giving instructors the ultimate tool for customizing lectures and presentations.

ExamView

Available on the Instructor’s Resource CD-ROM, ExamView contains all of the ques-tions in the printed Test Bank. This program is an easy-to-use test creation software compatible with Microsoft Windows. Instructors can add or edit questions, instructions, and answers, and select questions (randomly or numerically) by previewing them on the screen. Instructors can also create and administer quizzes online, whether over the Internet, a local area network (LAN), or a wide area network (WAN).

PowerPoint TM Presentation Slides

Available on the Instructor’s Resource CD-ROM and the Web site, the PowerPoint pre-sentation package consists of tables and figures used in the book. These colorful slides can greatly aid the integration of text material during lectures and discussions.

Web Site

A rich Web site at http://academic.cengage.com/management/cummings complements the text, providing many extras for the student and instructor.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Our friends and colleagues are always asking about “the text.” “Why did you include that?” “Why didn’t you include this?” “When are you going to revise it again?” “I have some suggestions that might improve this section.” And so on. It is gratifying, after eight (and now nine) editions, that people find the book provocative, refer to it, use it to guide their practice, and assign it as required reading in their courses. Even though the text is revised every three years or so, it seems to be a common subject of con-versation whenever we get together with our OD colleagues and students. When it does come time for revision, it provides us a chance to refresh, renew, and reestablish

our relationship with them. “What have you heard about what’s new in OD?” “How’s your family?” “Do you think we should reorganize the book?” “What’s next in your career?” “Did you see that article in (pick a journal or magazine)?” “What have you been reading lately?”

And then the research, reading, writing, editing, and proofing begins. Writing, debates, and editing occupy most of our time. “Can we say that better, more efficiently, and more clearly?” “Should we create a new section or revise the existing one?” “Do you really think people want to read that?” The permission requests go out and come in quickly . . . at least most of them. Follow up faxes, reminder e-mails, and urgent phone calls are made. The search for new cases and applications is an ongoing activity. “Where can we find good descriptions of change?” “Would you be willing to write up that case?” Deadlines come . . . and go. The copy editing process is banter between two strangers. “No, no, no, I meant to say that.” “Yes, that’s a good idea, I hadn’t thought of that.” Six months into it, our wives start to ask, “When will it be done?” Then, the result of having done this before, they ask, “no, I meant when will it be done, done?” When the final proofs arrive, things start to look finished. We get to see the art work and the cover design, and a new set of problems emerge. “Where did that come from?” “No, this goes there, that goes here.” Doesn’t this sound fun?

So, yes, we continue to hope that our readers, colleagues, and friends ask us about “the text.” We like talking about it, discussing it, and hearing about what we did right or wrong. But please don’t ask us about writing “the text.” We’re very happy to be done (yes, done, done).

Finally, we’d like to thank those who supported us in this effort. We are grateful to our families: Chailin Cummings and the Worley clan, Debbie, Sarah, Hannah, and Samuel. We would also like to thank our students for their comments on the previous edition, for contributing many of the applications, and for helping us to try out new ideas and perspectives. A particular word of thanks goes to Gordon Brooks, Brigette Worthen, and the Pepperdine MSOD faculty (Ann Feyerherm, Miriam Lacey, Terri Egan, and Gary Mangiofico). Our colleagues at USC’s Center for Effective Organizations—Ed Lawler, Sue Mohrman, John Boudreau, Alec Levenson, Jim O’Toole, Jay Conger, and Jay Galbraith—have been consistent sources of support and intellectual inquiry. As well, the following individuals reviewed the text and influenced our thinking with their hon-est and constructive feedback:

Ben Dattner, New York University

Diana Wong, Eastern Michigan University

Merwyn L. Strate, Purdue University

Bruce Brewer, University of West Georgia

Susan A. Lynham, Texas A&M University

We would also like to express our appreciation to members of the staff at Cengage Learning, South-Western, for their aid and encouragement. Special thanks go to Joe Sabatino, Denise Simon, and Jean Buttrom for their help and guidance throughout the development of this revision. Menaka Gupta patiently made sure that the editing and producing of our book went smoothly.

Thomas G. Cummings Christopher G. Worley

Palos Verdes Estates, California San Juan Capistrano, California

1

General Introduction to Organization

Development

This is a book about organization development (OD)—a process that applies a broad range of behavioral science knowledge and practices to help organizations build their capacity to change and to achieve greater effectiveness, includ-ing increased financial performance, customer satisfaction, and organization member engage-ment. Organization development differs from other planned change efforts, such as project management or innovation, because the focus is on building the organization’s ability to assess its current functioning and to achieve its goals. Moreover, OD is oriented to improving the total system—the organization and its parts in the con-text of the larger environment that affects them.

This book reviews the broad background of OD and examines assumptions, strategies and models, intervention techniques, and other aspects of OD. This chapter provides an intro-duction to OD, describing first the concept of OD itself. Second, it explains why OD has expanded rapidly in the past 50 years, both in terms of people’s need to work with and through others in organizations and in terms of organizations’ need to adapt in a complex and changing world. Third, it reviews briefly the history of OD, and fourth, it describes the evolution of OD into its current state. This intro-duction to OD is followed by an overview of the rest of the book.

ORGANIZATION DEVELOPMENT DEFINED

Organization development is both a professional field of social action and an area of scientific inquiry. The practice of OD covers a wide spectrum of activities, with seem-ingly endless variations upon them. Team building with top corporate management, structural change in a municipality, and job enrichment in a manufacturing firm are all examples of OD. Similarly, the study of OD addresses a broad range of topics, including the effects of change, the methods of organizational change, and the factors influenc-ing OD success.

improvement, and reinforcement of the strategies, structures, and processes that lead to organiza-tion effectiveness. This definition emphasizes several features that differentiate OD from other approaches to organizational change and improvement, such as management consulting, innovation, project management, and operations management. The defi-nition also helps to distinguish OD from two related subjects, change management and

organization change, that also are addressed in this book.

First, OD applies to changes in the strategy, structure, and/or processes of an entire system, such as an organization, a single plant of a multiplant firm, a department or work group, or individual role or job. A change program aimed at modifying an organization’s strategy, for example, might focus on how the organization relates to a wider environment and on how those relationships can be improved. It might include changes both in the grouping of people to perform tasks (structure) and in methods of communicating and solving problems (process) to support the changes in strategy. Similarly, an OD program directed at helping a top management team become more effective might focus on interactions and problem-solving processes within the group. This focus might result in the improved ability of top management to solve company problems in strategy and structure. This contrasts with approaches focusing on one or only a few aspects of a system, such as technological innovation or operations manage-ment. In these approaches, attention is narrowed to improvement of particular prod-ucts or processes, or to development of production or service delivery functions.

Second, OD is based on the application and transfer of behavioral science knowledge and practice, including microconcepts, such as leadership, group dynamics, and work design, and macroapproaches, such as strategy, organization design, and international Definitions of Organization Development

Organization development is a planned process of change in an organization’s culture through the utilization of behavioral science technology, research, and theory. (Warner Burke)2

Organization development refers to a long-range effort to improve an organization’s problem-solving capabilities and its ability to cope with changes in its external environment with the help of external or internal behavioral-scientist consultants, or change agents, as they are sometimes called. (Wendell French)3

Organization development is an effort (1) planned, (2) organization-wide, and (3) managed from the top, to (4) increase organization effectiveness and health through (5) planned interventions in the organization’s “processes,” using behavioral science knowledge. (Richard Beckhard)4

Organization development is a systemwide process of data collection, diagnosis, action planning, intervention, and evaluation aimed at (1) enhancing congruence among organizational structure, process, strategy, people, and culture; (2) developing new and creative organizational solutions; and (3) developing the organization’s self-renewing capacity. It occurs through the collaboration of organizational members working with a change agent using behavioral science theory, research, and technology. (Michael Beer)5

Based on (1) a set of values, largely humanistic; (2) application of the behavioral sciences; and (3) open systems theory, organization development is a system-wide process of planned change aimed toward improving overall organization effectiveness by way of enhanced congruence of such key organization dimensions as external environment, mission, strategy, leadership, culture, structure, information and reward systems, and work policies and procedures. (Warner Burke and David Bradford)6

•

•

•

•

•

3

CHAPTER 1 General Introduction to Organization Development

relations. These subjects distinguish OD from such applications as management consult-ing, technological innovation, or operations management that emphasize the economic, financial, and technical aspects of organizations. These approaches tend to neglect the personal and social characteristics of a system. Moreover, OD is distinguished by its intent to transfer behavioral science knowledge and skill so that the system is more capable of carrying out planned change in the future.

Third, OD is concerned with managing planned change, but not in the formal sense typically associated with management consulting or project management, which tends to comprise programmatic and expert-driven approaches to change. Rather, OD is more an adaptive process for planning and implementing change than a blueprint for how things should be done. It involves planning to diagnose and solve organizational problems, but such plans are flexible and often revised as new information is gathered as the change program progresses. If, for example, there was concern about the perfor-mance of a set of international subsidiaries, a reorganization process might begin with plans to assess the current relationships between the international divisions and the corporate headquarters and to redesign them if necessary. These plans would be modi-fied if the assessment discovered that most of the senior management teams were not given adequate cross-cultural training prior to their international assignments.

Fourth, OD involves the design, implementation, and the subsequent reinforce-ment of change. It moves beyond the initial efforts to implereinforce-ment a change program to a longer-term concern for appropriately institutionalizing new activities within the organization. For example, implementing self-managed work teams might focus on ways in which supervisors could give workers more control over work methods. After workers had more control, attention would shift to ensuring that supervisors contin-ued to provide that freedom. That assurance might include rewarding supervisors for managing in a participative style. This attention to reinforcement is similar to training and development approaches that address maintenance of new skills or behaviors, but it differs from other change perspectives that do not address how a change can be institutionalized.

Finally, OD is oriented to improving organizational effectiveness. Effectiveness is best measured along three dimensions. First, OD affirms that an effective organization is adaptable; it is able to solve its own problems and focus attention and resources on achieving key goals. OD helps organization members gain the skills and knowledge necessary to conduct these activities by involving them in the change process. Second, an effective organization has high financial and technical performance, including sales growth, acceptable profits, quality products and services, and high productiv-ity. OD helps organizations achieve these ends by leveraging social science practices to lower costs, improve products and services, and increase productivity. Finally, an effective organization has satisfied and loyal customers or other external stakeholders and an engaged, satisfied, and learning workforce. The organization’s performance responds to the needs of external groups, such as stockholders, customers, suppli-ers, and government agencies, which provide the organization with resources and legitimacy. Moreover, it is able to attract and motivate effective employees, who then perform at higher levels. Other forms of organizational change clearly differ from OD in their focus. Management consulting, for example, primarily addresses financial performance, whereas operations management or industrial engineering focuses on productivity.

performance and competitive advantage. Change management focuses more narrowly on values of cost, quality, and schedule.7 As a result, OD’s distinguishing feature is its concern with the transfer of knowledge and skill so that the system is more able to manage change in the future. Change management does not necessarily require the transfer of these skills. In short, all OD involves change management, but change man-agement may not involve OD.

Similarly, organizational change is a broader concept than OD. As discussed above, organization development can be applied to managing organizational change. However, it is primarily concerned with managing change in such a way that knowledge and skills are transferred to build the organization’s capability to achieve goals and solve problems. It is intended to change the organization in a particular direction, toward improved problem solving, responsiveness, quality of work life, and effectiveness. Organizational change, in contrast, is more broadly focused and can apply to any kind of change, includ-ing technical and managerial innovations, organization decline, or the evolution of a system over time. These changes may or may not be directed at making the organization more developed in the sense implied by OD.

The behavioral sciences have developed useful concepts and methods for helping organizations to deal with changing environments, competitor initiatives, technologi-cal innovation, globalization, or restructuring. They help managers and administrators to manage the change process. Many of these concepts and techniques are described in this book, particularly in relation to managing change.

THE GROWTH AND RELEVANCE OF ORGANIZATION

DEVELOPMENT

In each of the previous editions of this book, we argued that organizations must adapt to increasingly complex and uncertain technological, economic, political, and cultural changes. We also argued that OD could help an organization to create effec-tive responses to these changes and, in many cases, to proaceffec-tively influence the strategic direction of the firm. The rapidly changing conditions of the past few years confirm our arguments and accentuate their relevance. According to several observ-ers, organizations are in the midst of unprecedented uncertainty and chaos, and nothing short of a management revolution will save them.8 Three major trends are shaping change in organizations: globalization, information technology, and manage-rial innovation.9

First, globalization is changing the markets and environments in which organizations operate as well as the way they function. New governments, new leadership, new mar-kets, and new countries are emerging and creating a new global economy with both opportunities and threats.10 The toppling of the Berlin Wall symbolized and energized the reunification of Germany; the European Union created a cohesive economic block that alters the face of global markets; entrepreneurs appeared in Russia, the Balkans, and Siberia to transform the former Soviet Union; terrorism has reached into every corner of economic and social life; and China is emerging as an open market and global economic influence. The rapid spread of Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and its economic impact clearly demonstrated the interconnectedness among the social environment, organizations, and the global economy.

5

CHAPTER 1 General Introduction to Organization Development

the survivors of a busted dot-com bubble, Google has emerged as a major competitor to Microsoft, and the amount of business being conducted on the Internet is pro-jected to grow at double-digit rates. Moreover, the underlying rate of innovation is not expected to decline. Electronic data interchange—a state-of-the-art technology application a few years ago—is now considered routine business practice. The ability to move information easily and inexpensively throughout and among organizations has fueled the downsizing, delayering, and restructuring of firms. The Internet has enabled a new form of work known as telecommuting; organization members from Captial One and Cigna can work from their homes without ever going to the office. Finally, information technology is changing how knowledge is used. Information that is widely shared reduces the concentration of power at the top of the organization. In choosing “You” as the 2006 Person of the Year, Time magazine noted that the year was “a story about community and collaboration on a scale never seen before. It’s about . . . Wikipedia . . . YouTube and . . . MySpace. It’s about the many wresting power from the few and helping one another for nothing and how that will not only change the world, but also change the way the world changes (emphasis added).”11 Organization members now share the same key information that senior managers once used to control decision making.

Third, managerial innovation has responded to the globalization and information technol-ogy trends and has accelerated their impact on organizations. New organizational forms, such as networks, strategic alliances, and virtual corporations, provide organizations with new ways of thinking about how to manufacture goods and deliver services. The strategic alliance, for example, has emerged as one of the indispensable tools in strategy imple-mentation. No single organization, not even IBM, Mitsubishi, or General Electric, can control the environmental and market uncertainty it faces. Sun Microsystems’ network is so complex that some products it sells are never touched by a Sun employee. In addition, change innovations, such as downsizing or reengineering, have radically reduced the size of organizations and increased their flexibility; new large-group interventions, such as the search conference and open space, have increased the speed with which organizational change can take place; and organization learning interventions have acknowledged and leveraged knowledge as a critical organizational resource.12 Managers, OD practitioners, and researchers argue that these forces not only are powerful in their own right but are interrelated. Their interaction makes for a highly uncertain and chaotic environment for all kinds of organizations, including manufacturing and service firms and those in the public and private sectors. There is no question that these forces are profoundly affecting organizations.

Fortunately, a growing number of organizations are undertaking the kinds of organizational changes needed to survive and prosper in today’s environment. They are making themselves more streamlined and nimble, more responsive to external demands, and more ecologically sustainable. They are involving employees in key decisions and paying for performance rather than for time. They are taking the initia-tive in innovating and managing change, rather than simply responding to what has already happened.

OD is obviously important to those who plan a professional career in the field, either as an internal consultant employed by an organization or as an external consultant practicing in many organizations. A career in OD can be highly rewarding, providing challenging and interesting assignments working with managers and employees to improve their organizations and their work lives. In today’s environment, the demand for OD professionals is rising rapidly. For example, large professional services firms must have effective “change management” practices to be competitive. Career oppor-tunities in OD should continue to expand in the United States and abroad.

Organization development also is important to those who have no aspirations to become professional practitioners. All managers and administrators are responsible for supervising and developing subordinates and for improving their departments’ perfor-mance. Similarly, all staff specialists, such as financial analysts, engineers, information technologists, or market researchers, are responsible for offering advice and counsel to managers and for introducing new methods and practices. Finally, OD is important to general managers and other senior executives because OD can help the whole organi-zation be more flexible, adaptable, and effective.

Organization development can also help managers and staff personnel perform their tasks more effectively. It can provide the skills and knowledge necessary for establish-ing effective interpersonal relationships. It can show personnel how to work effectively with others in diagnosing complex problems and in devising appropriate solutions. It can help others become committed to the solutions, thereby increasing chances for their successful implementation. In short, OD is highly relevant to anyone having to work with and through others in organizations.

A SHORT HISTORY OF ORGANIZATION

DEVELOPMENT

A brief history of OD will help to clarify the evolution of the term as well as some of the problems and confusion that have surrounded it. As currently practiced, OD emerged from five major backgrounds or stems, as shown in Figure 1.1. The first was the growth of the National Training Laboratories (NTL) and the development of training groups, otherwise known as sensitivity training or T-groups. The second stem of OD was the classic work on action research conducted by social scientists interested in applying research to managing change. An important feature of action research was a technique known as survey feedback. Kurt Lewin, a prolific theorist, researcher, and practitioner in group dynamics and social change, was instrumental in the development of T-groups, survey feedback, and action research. His work led to the creation of OD and still serves as a major source of its concepts and methods. The third stem reflects a normative view of OD. Rensis Likert’s participative management framework and Blake and Mouton’s Grid® OD suggest a “one best way” to design and operate organizations. The fourth background is the approach focusing on productivity and the quality of work life. The fifth stem of OD, and the most recent influence on current practice, involves strategic change and organization transformation.

Laboratory Training Background

7

CHAPTER 1 General Introduction to Organization Development

Laboratory Training

Action Research/Survey Feedback

Normative Approaches

Quality of Work Life

Strategic Change

1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000

CURRENT OD PRA

CTICE

Today

American Jewish Congress for help in research on training community leaders. A workshop was developed, and the community leaders were brought together to learn about leadership and to discuss problems. At the end of each day, the research-ers discussed privately what behaviors and group dynamics they had observed. The community leaders asked permission to sit in on these feedback sessions. Reluctant at first, the researchers finally agreed. Thus, the first T-group was formed in which people reacted to data about their own behavior.13 The researchers drew two conclu-sions about this first T-group experiment: (1) Feedback about group interaction was a rich learning experience, and (2) the process of “group building” had potential for learning that could be transferred to “back-home” situations.14

As a result of this experience, the Office of Naval Research and the National Education Association provided financial backing to form the National Training Laboratories, and Gould Academy in Bethel, Maine, was selected as a site for further work (since then, Bethel has played an important part in NTL). The first Basic Skill Groups were offered in the summer of 1947. The program was so successful that the Carnegie Foundation provided support for programs in 1948 and 1949. This led to a permanent program for NTL within the National Education Association.

In the 1950s, three trends emerged: (1) the emergence of regional laboratories, (2) the expansion of summer program sessions to year-round sessions, and (3) the expansion of the T-group into business and industry, with NTL members becom-ing increasbecom-ingly involved with industry programs. Notable among these industry efforts was the pioneering work of Douglas McGregor at Union Carbide, of Herbert Shepard and Robert Blake at Esso Standard Oil (now ExxonMobil), of McGregor and Richard Beckhard at General Mills, and of Bob Tannenbaum at TRW Space Systems.15

The Five Stems of OD Practice

Applications of T-group methods at these companies spawned the term “organization development” and, equally important, led corporate personnel and industrial relations specialists to expand their roles to offer internal consulting services to managers.16

Over time, T-groups have declined as an OD intervention. They are closely associ-ated with that side of OD’s reputation as a “touchy-feely” process. NTL, as well as UCLA and Stanford, continues to offer T-groups to the public, a number of proprietary programs continue to thrive, and Pepperdine University and American University con-tinue to utilize T-groups as part of master’s level OD practitioner education. The practi-cal aspects of T-group techniques for organizations gradually became known as team building—a process for helping work groups become more effective in accomplishing tasks and satisfying member needs. Team building is one of the most common and institutionalized forms of OD today.

Action Research and Survey Feedback Background

Kurt Lewin also was involved in the second movement that led to OD’s emergence as a practical field of social science. This second background refers to the processes of action research and survey feedback. The action research contribution began in the 1940s with studies conducted by social scientists John Collier, Kurt Lewin, and William Whyte. They discovered that research needed to be closely linked to action if organization members were to use it to manage change. A collaborative effort was initiated between organization members and social scientists to collect research data about an organiza-tion’s functioning, to analyze it for causes of problems, and to devise and implement solutions. After implementation, further data were collected to assess the results, and the cycle of data collection and action often continued. The results of action research were twofold: Members of organizations were able to use research on themselves to guide action and change, and social scientists were able to study that process to derive new knowledge that could be used elsewhere.

Among the pioneering action research studies were the work of Lewin and his students at the Harwood Manufacturing Company17 and the classic research by Lester Coch and John French on overcoming resistance to change.18 The latter study led to the development of participative management as a means of getting employees involved in planning and managing change. Other notable action research contributions included Whyte and Edith Hamilton’s famous study of Chicago’s Tremont Hotel19 and Collier’s efforts to apply action research techniques to improving race relations when he was commissioner of Indian affairs from 1933 to 1945.20 These studies did much to establish action research as integral to organization change. Today, it is the backbone of many OD applications.

A key component of most action research studies was the systematic collection of survey data that were fed back to the client organization. Following Lewin’s death in 1947, his Research Center for Group Dynamics at MIT moved to Michigan and joined with the Survey Research Center as part of the Institute for Social Research. The institute was headed by Rensis Likert, a pioneer in developing scientific approaches to attitude surveys. His doctoral dissertation at Columbia University developed the widely used 5-point “Likert Scale.”21