Volume 8 Number 3 2011 www.wwwords.co.uk/ELEA

Spatial Conditions: an unheeded

medium in teaching and learning

TINA BERING KEIDING

Danish School of Education in Aarhus,

Aarhus University, Denmark

ABSTRACT This article addresses spatiality as an educational category by asking how spatiality influences students’ experiences of interactions in project-based teaching. It examines students’ experiences with two different spatial conditions - namely, separate rooms, each accommodating a single group, or a much larger open space hosting multiple groups. It concludes that students’ experiences of the two types of spatiality provide very different contexts for interaction and learning. The advantages of separate rooms for multiple groups arise from their affordance of spontaneous inspiration, feedback and learning, but they present challenges regarding the handling of complexity. Single-group rooms support focus in discussions, but prevent members of one group from drawing inspiration from others. Deconstruction of students’ utterances about their interaction with students from other groups indicates that the experience of knowing each other, belonging to and being a part of the community appears to be the factor which makes a difference in students’ engaging in

professional interactions. The findings suggest that the multiple-group room assists in the development of competencies in the areas of networking, professional interaction and learning.

Introduction

Project-based teaching in general plays a significant role in higher education, particularly where the development of professional skills and innovation is a priority (Frey, 1984). However, different types of project-based teaching (individual/group-based; of short as well as of long duration) can be identified in almost any higher education context.

group rooms is used. Hans Kiib, the former head of the study board and the main architect behind the educational programme, regrets this: ‘Our first-year students are put in closed rooms, which means that the transparent learning environment, initiating learning from observation of what and how others do, is absent.’ On the other hand, research indicates that people who work in open offices do not experience more support and feedback from colleagues than those working in cell offices (e.g. Pejtersen, 2006).

The apparent disagreement as to whether open offices afford more dynamic and learning-conducive environments than cell offices generated the first of the two research questions addressed in this article: Are spatial conditions experienced as making a difference for student learning in project-based teaching? An affirmative answer prompted a second question asking after the possible social mechanisms behind these experiences.

Analytical Strategy

This section presents the empirical approach and the theoretical framework used in reflections on empirical findings.

Two Types of Spatial Conditions

The research concerns project-based teaching in two types of spatial conditions: the multiple group room (MGR) and the single group room (SGR).

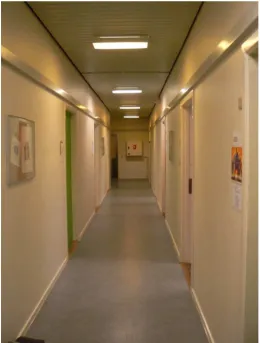

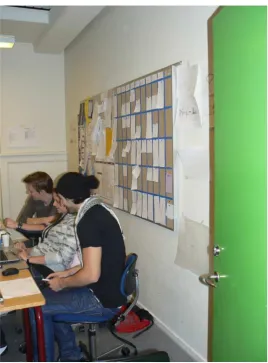

MGR is a semi-open space in which several project groups have their own working space separated by flexible partition walls. Working spaces are placed along the outer walls, leaving an open square in the middle (Figures 1a and 1b). SGR houses a single group and is separated from other areas by solid walls and a door. Both rooms adjoin a narrow corridor (Figures 2a and 2b).

Due to the increased number of students in the Architecture & Design programme at Aalborg University during the academic year of 2007/08, not all groups could be hosted in individual rooms. As a consequence, the groups were assigned their own room (SGR) or placed in an open space office (MGR) by drawing lots. This situation offered a unique opportunity to compare student experiences with the two types of spatial conditions under circumstances in which all other conditions could be assumed to be similar.

The main differences between the two types of spatial conditions relate to the outer surroundings (open square versus narrow corridor) and to differences in boundaries (partition walls and no doors versus solid walls and doors) (Figures 1a, 2a). The inner surroundings with respect to physical conditions are very similar (Figures 1b, 2b).

Figure 1b. Inner surroundings in MGR.

Figure 2b. Inner surroundings in SGR.

Theoretical Framework

The research draws theoretically on concepts from the German sociologist Niklas Luhmann’s systems theory (Luhmann, 1990, 1995a,b,c, 2002a,b,c) and on research in which his general concepts are transposed into theories of teaching and learning (Keiding, 2005, 2007a,b, 2008a,b). A few key words are needed in sketching out Luhmann’s interpretation of systems theory. Beyond the concept of systems, this includes the concepts of self-reference, functional closeness and structural coupling, and the concepts of observation and learning.

Luhmann’s systems theory belongs to the so-called second generation of systems theory, which is devoted to the understanding of the evolution and dynamics of complex units (systems). The key concepts are the notions of self-referentiality and autopoietic reproduction; the latter was developed by the biologists Humberto Maturana and Francisco Varela. Claiming that systems are self-referential and operate autopoietically means that they, in their operations, refer to their previous operations, and through these reiterative processes produce themselves and the elements of which they consist (e.g. Maturana & Varela, 1987).

The concepts of self-referentiality and autopoietic reproduction do not imply that systems are isolated or independent from the environment (Luhmann, 2002a, p. 101). Within this framework, systems are closed at the level of operation but cognitively open. They can observe and use the information thereby gained as a point of departure for new internal operations.

Observations are asymmetric (or symmetry-breaking) operations. They use distinctions as forms and take forms as boundaries, separating an inner side (the Gestalt) and an outer side. The inner side is the indicated side, the marked side. From here one has to start the next operation. The inner side has connective value. (Luhmann, 2002a, p. 101)

In this sense, observations create objects and phenomena, which the system can use for subsequent operations. One distinguishes from other vehicles one car which apparently has no intention to stop at the red light, and one decides to stop until it has passed. From this perspective, observation does not ‘transmit’ information from the environment into the system. It allows for the observing system to produce information about its environment, but the information refers to the system and how it has observed its environment, not to the environment in itself. What students learn from teaching depends on how they, in the act of observation, ‘connect’ to teaching and how the information gained from the observation is interpreted and incorporated into their individual cognitive structures.

This interpretation of systems theory has strong epistemological implications - what a system knows and learns refers to the structures of the system and how it has observed its environment (e.g. Luhmann, 2002a). Luhmann distinguishes between three principle types of autopoietic systems: living systems (i.e. cells, brains and organisms); systems of consciousness (i.e. minds); and systems of communication or social systems (i.e. society, organizations and interactions). Communication in modern society, Luhmann explains, tends to be functionally differentiated into sub-systems such as politics, economics, science, religion, and - particularly relevant to this article - education. Each functional system differentiates itself from its environment (i.e. the rest of society) by a unique coding of its communication. Communication in the economic system is, for instance, organized around the code of gain/loss, whereas communication in the educational system is organized around the code of better/worse knowledge. The processes of differentiation are understood by Luhmann as an answer to increasing societal complexity:

The system becomes more dependent on certain properties or processes in the environment – namely those relevant for input or for registering output – and, conversely, less dependent on other aspects of the environment. It can achieve more sensitivity, more clarity in perceiving the environment, and more indifference, all at once. (Luhmann, 1995a, p. 204)

The gradient of complexity is always declining across the border between environment and system (Luhmann, 1995a, pp. 23ff.). Social interaction and the physical environment are more complex than a psychic system can observe, and the complexity of the psychic system is higher than anything that can be addressed in a specific social system.

With regard to social systems, Luhmann’s systems theory represents a radical break with theorizing that went before it, in that it takes communication rather than the human individual as its central category. It understands social systems - be they society as a whole, or its functional systems, organizations or interaction systems – not in terms of individuals and their agency (or lack thereof), but in terms of the self-referential process of communication. Human beings, as aggregates of a living body and a psychic system, are seen as systems in the environment of social systems. On the one hand they are fundamental for the existence of social systems; on the other hand, they are not the ‘cause’ or point of reference for the dynamics and structures of social systems. ‘Of course, we do not maintain that there can be social systems without consciousness. But subjectness, the availability of consciousness, its underlying everything else, is assumed to be the environment of social systems, not their self-reference’ (Luhmann, 1995a, p. 170).

The attribution of human beings to the environment of social systems has produced strong reactions and accusations of ‘anti-humanism’. That discussion falls outside the scope of this contribution. However, a few remarks must be made on Luhmann’s own reply to the critique:

This article deals with both social and psychic systems - psychic systems as the consciousness of students who experience social interaction under two different spatial conditions. Project groups and more informal, often spontaneous, interaction between students from different project groups are considered as social systems, and are accordingly based on communication. However, social systems are only observed indirectly through students’ observation of their experiences with social interaction and group processes in two different spatial settings (i.e. the analytical unit is students’ psychic system). This will be further elaborated in the descriptions of the empirical method. Information generated through observation may, in some cases, confirm expectations and, in other situations, trigger new learning. In neither case, however, do observation and learning processes transmit anything from the outside into the observing system. External events can stimulate self-referential learning processes, but they do not steer or determine the system’s operation. A psychic system thinks what it thinks and social systems, be they project groups or informal interactions, communicate what they communicate regardless of the processes - for instance, approval or disapproval - occurring internally in other systems. The meaning and significance of any event occurring in a system is defined in the system, not by the environment. Whether a student finds an utterance from the group next door interesting or disturbing depends on the actual internal state of the observing system (i.e. the student’s psychic system). And whether a group finds a suggestion offered by a group member or a student from another group worth further consideration depends on the group as a social system and its actual state of communication, not on the information in itself.

The actual meaning is selected from a horizon of possibilities, and the selection simultaneously produces a new horizon of meaningful possibilities for new expectations or actions. Meaning may be broken down analytically into three dimensions: the fact dimension; the temporal dimension; and the social dimension (Luhmann, 1995a, p. 75). What, when and who, in other words, are constitutive of the horizon of meaning. The three dimensions of meaning are used as guiding differences in order to come closer to student experiences of and expectations for interaction in MGR and SGR.

The theoretical concepts have implications for our understanding of how spatial conditions might influence learning and communication. Due to physical differences, SGR and MGR offer different opportunities for observing the members, products and communication of other groups. In SGR, communication occurring within other groups cannot be heard; their models are not immediately observable. In MGR, both are almost unavoidable. However, spatiality also emerges as a contingent horizon of meaning depending on how it is interpreted and experienced by the students. This means that the influence of spatiality on learning experiences and social interaction cannot be deduced directly from physical appearances and conditions. For instance, the experience of difficulties with engaging in interaction may lead both to a withdrawal from future attempts (‘it does not help anyway’) and to more intensive efforts (‘I must overcome this’).

Consequently, the relation between spatial conditions and student interaction and experience must be conceptualized as affordances, rather than in terms of causalities. This means that how expectations influence interaction, and vice versa, must be described empirically. Expectations and interpretations do not emerge out of the blue. They are shaped – but, again, not causally determined – by the horizon of meaning created from previous experiences. For instance, entering a classroom most likely activates experiences and behaviours from previous participation in classroom interactions, which, in interplay with the actual situation, outline a horizon of expectations for interaction and behaviours (e.g. Bateson, 2000; Keiding & Laursen, 2005).

might be learned besides the intended learning outcomes’ are known as the concept of ‘the hidden curriculum’ (e.g., Jackson, 1968). The concept of the hidden curriculum stems from a critical position regarding what schooling teaches students ‘behind their back’ - for instance, a strong inclination towards competition and individual performances, or loss of determination and self-dependence as a consequence of individual testing and ranking. The same idea – namely, that both social systems and human individuals in the learning process (e.g. designing a teapot) learn about the context of the learning process - is fundamental in Gregory Bateson’s theory of logical categories of learning and communication (Bateson, 2000). He describes this learning about the context and the conditions of interaction (the rules of the game, so to speak) as ‘learning how to interpret signals’, and sees it as fundamental for managing and participating social interaction. Context learning, in other words, provides the learning system with a frame (i.e. a context) which enables it to interpret and select what, based on experiences, can be expected to be relevant actions in a new social situation.

With Bateson, this learning about the context is widely unattended by the learning system, whose attention mainly is on the core subject of the learning process, whatever it might be. Context learning, so to speak, develops along with the learning of the main topic, which makes the concept of co-learning relevant. In this sense, Bateson’s concept of context learning resembles the learning processes described in relation to the hidden curriculum. On the other hand, Bateson clearly addresses context learning, or co-learning, from a functionalist perspective rather than from a critical position. To avoid any implicit and unwanted tendencies towards a critical and normative interpretation, I use the concept of co-learning in describing ‘what also might be learning’ from interaction in different spatial conditions.

Empirical Method

The aim of the research is to explore spatiality as an educational category; more specifically, it is to inquire as to whether different spatial conditions seem to create different contexts for social interaction, with an emphasis on learning and knowledge-sharing. The perspective is currently limited to students’ experiences. Whether different spatial conditions have an impact on observed learning outcomes and project quality is not addressed in this study.

The empirical observations are based on students’ descriptions of their experiences with project-based teaching in the two types of spatial conditions described above (MGR and SGR). Students’ experiences are seen as psychic events (e.g. as thoughts, sensations, impressions, imaginations, and consequently as merely non-linguistic forms). They refer to the single individual’s psychic system and how it has observed, interpreted and experienced social interaction in different spatial conditions (i.e. the analytical unit is the students’ psychic system).

Psychic system experiences cannot be observed directly but must be interpreted on the basis of communicative forms (utterances) (e.g. Luhmann, 2002b). In contrast to psychic systems, communication, especially in recorded interviews and questionnaires, is based largely on linguistic utterances. Accordingly, interviews and questionnaires transform experiences as non-linguistic psychic elements into linguistic forms. This transformation cannot be seen as a neutral preservation of meaning from one medium to another, but adds itself as a layer of interpretation to the empirical process (Keiding, 2010a).

Interviews and questionnaires provide specific conditions for social interaction. Not everything observed in the student’s psychic system is considered relevant as information, and not everything that is conditionally relevant can be uttered in an interview or in questionnaires. Consequently, the utterances reveal what students chose to express and how they chose to express themselves, and are linguistic reconstructions of a complex of experiences as psychic events, not their experiences as a whole. In this sense, the interviews and questionnaires are seen as complexity-reducing processes which select, interpret and transform experiences as psychic events into events in a social system - in this case, the interaction between students and researcher.

their own project. Utterances from interviews and questionnaires were examined in accordance with what was indicated within each guiding difference. Indications were subsequently categorized thematically. The categories were generated from the utterances. The utterance ‘it might be difficult to get some peace when you have to discuss something important in the group’ was, for instance, categorized as ‘noise and disturbances’ within the guiding difference ‘disadvantages OF? MGR’.

In the second phase, utterances were categorized using the three dimensions of meaning (fact dimension, temporality, and social dimension) (Luhmann, 1995a). Within each dimension of meaning, utterances were grouped thematically. The utterance ‘it was not relevant for our project, but you may [get inspiration, TBK] if you are interested in others’ projects’ was assigned to the ‘fact dimension’ and categorized as ‘no inspiration due to differences in fact dimension’.

Quotations are identified by ‘Q’ (for questionnaire) followed by the number of the questionnaire (e.g. Q28, for questionnaire number 28), or by ‘I’ (for interview) followed by group number and date (e.g. I333-2007.11.20. for the interview with group 333 from 20 November 2007). All quotations are translated by the author.

The data were generated in the last part of first semester in the academic year of 2007/08. At this point, students had completed their first project and were well into the third month of their second project. At the beginning of the second project, students had formed new groups and had been assigned rooms by drawing lots. Of a total of 15 groups, 7 were placed in MGR and 8 in SGR. Of a total of 130 students, 50 agreed to participate in the research project, a size which allows for the identification of significant differences within the population. The design, however, does not allow for generalizations beyond the population.

Findings on Advantages and Disadvantages

The most frequently marked advantages in MGR (38 of 50 students) fall into the category ‘inspiration and opportunities for help from other groups’. One student, who carried out his first project in SGR, puts it as follows: ‘I am in MGR, which is far more inspiring and spirited.… It is inspiring just to hear single words or themes from the neighbor group, to pass by their models, etc.’ (Q48). A recurring theme in the responses on MGR is that it is easier to find inspiration and that inspiration occurs almost spontaneously. The previous quotation mentions ‘hearing single words’ and ‘passing by’. Another student writes, ‘You can hardly avoid being influenced or getting good ideas from what you experience from other groups’ (Q50).

It is possible to identify two sources of inspiration. One, illustrated by the previous quotations, concerns random and unforeseen inspiration from the unplanned and spontaneous observation by students of social and physical surroundings. The other type of inspiration occurs in more planned and focused interactions in which projects are discussed and commented on by members of other groups in more formalized settings; for example: ‘it is good to expose your ideas to other groups in order to have them assessed by someone from outside’ (Q42). The difference can also be described by saying that, in the first case, inspiration arises spontaneously, whereas it is deliberately sought out in the other case. Despite the widespread appreciation of the possibilities for inspiration and feedback, a few students mention that this simultaneously challenges them and their project: ‘You can also say that it [i.e. easy access to inspiration, TBK] puts a strain on your trust in yourself sometimes’ (Q48).

The main disadvantages in MGR fall into the category ‘noise and disturbances’ (21 of 50 students). The disadvantages regarding noise vary in description from ‘it might play a role’ (Q6) to ‘more noise than in SGR’ to ‘too much noise’ (Q46). Five students indicate that they appreciate the presence of the other groups and the ‘humming of creativity in MGR’ (Q40). Of a total of 50, as many as 34 students report that they prefer MGR, which indicates that advantages regarding inspiration and professional interaction are valued more highly than disadvantages related to noise.

The major disadvantages in SGR relate to the category ‘inspiration’. Of 50 students, 24 indicate ‘lack of inspiration’ or even ‘isolation’ as a disadvantage in SGR. For example, ‘It [i.e. the project, TBK] becomes more of a one-track process without the informal visits. We end up with a closed door to preclude input, help and just being together with the other groups. We “get stuck” in the group room, not intensively seeking information and dropping in on other groups’ (Q28).

Some students in SGR try to deal with the absence of immediate access to inspiration by deliberately contacting other groups and by reaching agreements on open-door policies. One student reports, ‘We do not talk much with other groups and you do not enter if the door is closed. We have tried to make an agreement that the door should be closed no more than one hour a day, but people do not stick to it. That’s too bad, because it makes it difficult to get inspiration from others’ (Q51). Another student placed in SGR says, ‘I think we are more aware of what we miss by not sitting in the big room. We reach out and can, therefore, have some of the advantages and still close the door when needed’ (Q20). Nine of the 13 students who indicated that they prefer SGR also indicated ‘access to inspiration from other students than the group members’ as the main advantage in MGR.

Looking across the answers, ‘inspiration’ reveals itself as a recurrent topic. But how can mutually closed systems inspire each other? In order to understand this, one must take a closer look at the concepts of observation and learning. As previously mentioned, autopoietic systems can observe their environment and use observations as the starting point for new operations, including learning processes. Observation and learning processes might either take their point of departure as the learning individual actively seeking new information, or be triggered by the environment, which, by its mere appearance, attracts the attention of the learner. In systems theory one often describes this non-causal influence of the environment on a system in terms of ‘irritation’, thereby emphasizing that the environment might affect the system in a non-determining way.

When students describe their social and physical environment as inspiring, they, within Luhmann’s theoretical framework, indicate that observation of the environment irritates or stimulates their psychic system in ways that they find fruitful for their professional learning processes.

Social Mechanisms for Inspirational Interaction

So far, from a student perspective, it is clear that MGR affords better conditions for mutual inspiration and interaction than SGR. The next step is to take a closer look at the descriptions to investigate significant dimensions for the emergence of inspirational interaction. This is done by the categorization of utterances on inspiration into the three dimensions of meaning: the factual, the temporal, and the social. Do students and projects from other groups afford inspiration because they converge on common issues and solutions? Is synchronicity and being in the same phase important? Or are personal relations a major criterion for inspiring interaction? How do enhanced access or limited access, respectively, to other students and their projects make a difference in interaction?

Observing Interaction – fact dimension

In general, students stress that fruitful inspiration is related to gaining ‘new eyes on the project’ or taking ‘a look from outside’. Both perspectives are expressed in condensed form when a student said, ‘You get good ideas from observing what other groups are doing. And because people drop by and comment on what we are doing, you get eyes from outside on your project’ (Q34).

indication can be found that mutual inspiration is related to the merging of, imitation of, or convergence of projects in the fact dimension. On the contrary, students stick to their own ideas and use information and feedback selectively: ‘It [i.e. the project, TBK] might become more versatile, but at the same time you have to stick to your own, so that the project retains its identity’ (Q2).

A number of students claim that the ongoing interaction and inspiration introduce a competitive dimension and raise the level of ambition and the quality of projects: ‘Our group spirit was strengthened by observing that our project was considerably better than that of the group next to us, who worked on the same issue. I think that the competitive dimension is important. You compare with the others. You see that there are different ways of doing things’ (Q32).

Summarizing the fact dimension, inspiration experienced in MGR can be related to enhanced complexity and different perspectives. MGR offers an opportunity for students to sharpen their understanding as well as their project in two ways: either by reflecting their knowledge and solutions within a horizon of other possibilities created solely from spontaneous observation of other projects, or by engaging directly in interaction oriented towards the discussion of and provision of feedback on the projects. In both cases, observation might confirm their own approach or be used as a point of departure for new learning.

Observing Interaction – temporal dimension

The temporal dimension addresses whether inspiration from other projects relates to some degree of synchronicity between the new information and the student’s own project. One student confirms this by saying that feedback from others did not influence the project because ‘we were somewhere else in our project and, due to limitations in time, we felt that we did not have the time for major changes’ (Q29).

One of the most frequently marked disadvantages in MGR relates to the interruption of both individual concentration and discussions in the group. As I see it, interruption is closely related to a question of timing or, rather, ‘bad timing’. Designating a comment or question as an interruption is not a judgment concerning the content of the statement (fact dimension) but relates to the fact that it occurs at the wrong moment. Negative judgments about quality in the fact dimension would contain adjectives such as ‘irrelevant’ or ‘rubbish’ rather than describing utterances as interruptions.

Accordingly, temporality seems to play a significant role in whether a given issue in interaction (fact dimension) is observed as inspiration or disturbance. New issues and ideas are more likely to be inspiring if they appear at ‘the right time’ as seen from the learner’s point of view, either because the learner is open to inspiration in advance or because the information (fact dimension) affects interest and, simultaneously, changes the timing from ‘wrong’ to ‘right’.

Observing Interaction – social dimension

In both MGR and SGR, informants generally refer to their fellow students by using the rather neutral distinction ‘others/us’, thereby generally indicating whether a given statement concerns the student’s own group or another group. However, other distinctions are also used in utterances categorized in the social dimension.

The experience of not knowing other students and being left outside or even excluded from the community versus knowing and being a part of the community influences students’ impulses to take the initiative for interaction. A common theme is that it is easier to interact professionally in the social climate of MGR: ‘Partition’ (Q18). A few students elaborate, saying that one is more daring in asking for help (Q21) and not inhibited in interaction (Q26). Seven students report on SGR in terms that indicate that the door is viewed as a demarcation line between public and private spheres: ‘I rarely looked into other one-group rooms, because you almost break into a private room by opening the door’ (Q23). And: ‘in SGR it seemed completely wrong to enter the room of another group, so I did not know what they were engaged in. In the big room, we meet each other spontaneously’ (Q34). The privacy indicated is also revealed in the interviews when students use the term ‘guest’ (I333-2007.11.20, I341-2007.11.20) or ‘stranger’ (I302h-2007.11.20) to describe a person who enters an SGR. In contrast, students and groups in MGR are generally designated as ‘neighbors’.

Accordingly, students in SGR not only face physical barriers which prevent them from spontaneously and informally overhearing and observing other groups, but also experience mental and social barriers that make them hesitate to take the initiative for interaction.

Reflections on Findings

The findings are discussed in the light of the two guiding questions: Are spatial conditions experienced as making a difference for student learning in project-based teaching? What can be said about the systems’ mechanisms behind these experiences?

MGR and SGR as Contexts for Learning

The major difference between MGR and SGR concerns physical and social surroundings outside a group’s private working area. The inner surroundings are, from a physical point of view, quite similar.

In MGR, oral communication from other projects can be overheard, and spontaneous interactions may occur simply through being present in the room. Furthermore, the working spaces contain project schedules, programmes and models, which can be observed directly when a student leaves her/his own working area. Both are described as inspiring and stimulating opportunities for learning.

In SGR, communication in other projects cannot be heard. Furthermore, when they leave their room, students enter a narrow corridor containing no project-related information and very little that is encouraging the emergence of spontaneous, informal meetings. If the doors to the other rooms are closed, students have no opportunity whatsoever to observe other projects spontaneously. Accordingly, SGR makes it highly unlikely that students become engaged in unforeseen learning situations. This alleviates information overload and reduces complexity, and thus SGR helps both students and their projects to target and stabilize learning processes. When students mention that it is easier to maintain focus in SGR, they seem to refer both to fewer direct interruptions and to enhanced focus on the project due to reduced complexity in the surroundings.

Inspiration from other groups is highly valued by the informants. Regarding MGR, the issue is addressed from a perspective of accessibility and affordance, whereas in relation to SGR, it is addressed from a perspective of isolation and absence. Inspiration and feedback are experienced as both contributing to individual learning and enhancing the quality of the project. However, the impact on learning can be neither confirmed nor disproved, since the research deals exclusively with students’ descriptions of their experiences. Although students in SGR strive to overcome the lack of access to spontaneous inspiration and the risk of isolation by visiting other groups and by making agreements on open-door policies, it seems difficult to realize these things in practice. The SGR is, for better or for worse, experienced as a private sphere, where students from other groups enter more like guests or intruders than as fellow students and learning partners.

almost unavoidable observation of other projects’ communication, schedules, models, and drawings in MGR challenges both students and their projects. In MGR, students face a constant challenge to deal with and reduce complexity. They must decide whether to engage in learning or not, and subsequently whether new individual learning should be introduced in their own project or not. Finally, they must contribute to their projects’ ongoing reflection on new issues: should a new idea be integrated into the project or rejected? Reflection takes time, and in environments in which students continuously observe new perspectives and ideas, it might be harder and take longer for students and projects to target their learning processes and to stick to previous decisions (e.g. Keiding, 2008a).

SGR challenges students to actively seek information that helps them move beyond existing knowledge – for example, by arranging formal meetings or by deliberately ‘crossing borders’ to private rooms. If students in SGR do not actively seek new information or get new impressions from visitors, they are likely to use primarily self-generated information. In such cases, students might create a closed loop of knowledge in which they merely confirm each other rather than challenging and expanding their knowledge. The student who talks about one-track projects addresses this risk.

The findings contradict findings from other research saying that people who work in open offices do not experience more support and feedback from colleagues than people who work in cell offices (e.g. Pejtersen, 2006). Drawing on Luhmann’s concepts of functional differentiation and conditioning, it can be suggested that projects carried out within the social system of education differ fundamentally from tasks carried out in other systems (e.g. Luhmann, 2002c). The educational system is, as mentioned, organized around the code better/worse knowledge. This means that single students and the groups, as psychic and social systems, respectively, use this code as a frame for both external observations and internal reflections. Accordingly, they can be expected to engage in processes which they, from their self-referential point of view, judge as relevant for growth of ‘better knowledge’, and, correspondingly, to avoid involvement in processes which they consider counterproductive for ‘better knowledge’. They can, in other words, be expected to frame themselves as learning systems. This does not mean that students and projects always code themselves as learning systems, it only means that a major part of the interaction in this study, consistent with the code of the educational system, appears to be coded as having an educational purpose and that both students and project groups have a strong inclination towards observations and interactions which they consider fruitful for development of valuable knowledge. In contrast, the professional interactions described in Pejtersen (2006) seem to be framed as work/production processes. What appears as an adequate action in the educational system – for instance, spending time seeking and discussing new knowledge – may appear irrelevant or even inappropriate in the context of production, if the task can be handled without new learning. This difference in framing may be one reason why students in this research project value the opportunity for feedback and learning from fellow students. They might simply ‘be in it for the learning’, whereas learning in work situations might be limited to particular occasions (e.g. Keiding & Laursen 2005, pp. 142ff.). This assumption is supported empirically in Keiding & Laursen, 2008.

Another explanation could be that projects in the Architecture & Design program produce manifest and tangible products – namely, models and drawings which, due to their non-evanescent character, can be observed and used as a source of inspiration whenever the system is ready to learn. Tangible forms, so to speak, offer a stable environment for learning which is less susceptible to timing and synchronicity between the information offered and the operations of the learning system, be it a single student or a group. Students, however, also emphasize the spontaneous and unforeseen inspiration from overhearing discussions in other groups and informal interactions. This appreciation of evanescent events indicates that experiences of mutual inspiration do not relate exclusively to presence of tangible products.

Dimensions of Meaning

Categorizing the descriptions of interaction in the three dimensions of meaning indicates that each dimension plays a different role in the student experience of environments conductive to learning. The fact dimension appears to be of minor importance. This might be related to the fact that the projects all have a common curriculum. They are conditionally framed by common learning objectives, common themes, identical time horizons, and similar levels of knowledge among students. This type of conditioning is likely to be a general condition in the educational system. Consequently, educational projects in general might have favourable conditions for mutual inspiration and feedback with respect to the subject-matter dimension Utterances related to the temporal dimension indicate that timing plays a significant role in decisions on whether particular information is deemed inspiring or disturbing. Partly independent of the fact dimension, information is more likely to be designated ‘inspiring’ if it occurs at the right time, and ‘uninspiring’ or ‘disturbing’ if it occurs at the wrong time.

Drawing on Gregory Bateson’s concept of context markers (Bateson, 2000, p. 289), one might say that ‘timing’ serves as a significant context marker to indicate whether an event is experienced disturbing (information X at the wrong time) or inspiring (information X at the right time). Between these two poles, time seems subordinate to the fact dimension. If the information catches the attention of the student, the time may suddenly become ‘right for learning’. Students address this situation when they talk about ‘unforeseen’ and ‘spontaneous’ inspiration.

Regarding co-learning, findings related to the temporal dimension indicate that students not only learn to reflect on information regarding subject-matter relevance (fact dimension) but also learn to reflect on and evaluate information with respect to the temporal phases of the project. Since not everything can be learned or dealt with at the same time, this dimension of co-learning might be supportive for the development of learning competencies and project competencies. Project competencies are fundamental not only in the educational system; many jobs have the character of projects, since they must be completed within a limited span of time and, simultaneously, operate in semi-open horizons with respect to solutions, content and knowledge (Keiding, 2008a; Keiding & Laursen, 2008).

Disregarding the significance of the fact dimension and timing, the social dimension appears to be most decisive for the emergence of inspirational interaction. The most frequently used distinctions, when students describe the differences between SGR and MGR, concern ‘knowing/not knowing other students’ and ‘being part of/not being part of the community’. Not knowing other students and the experience of not being part of or even of being excluded from the community seem to comprise a highly efficient gatekeeper for mutual inspiration in SGR. That students hesitate to call on groups in SGR relates not to the fact or the temporal dimension, but to a sense of intruding into a private area. In SGR, the experience is that one has to be invited to enter a room – for instance, by an open door - whereas students in MGR feel free to drop in on their neighbours at almost any time.

Regarding physical barriers, as compared with MGR, SGR does not display differences that could not, at least to some extent, be handled by open doors, for instance. The main barrier is the discomfort of entering other rooms. Students hesitate to call on other groups because they experience themselves as strangers entering a private room, and, consequently, they exclude themselves from engaging in professional interaction. This in turn impacts interaction, which becomes superficial and does not seem able to build up the relevant complexity in relation to professional issues. Consequently, the environment appears as one that is inspiring for learning, which again has an impact on overcoming the discomfort of entering an SGR. This might create a negative circle of self-exclusion in SGR. In MGR, the point of departure is different. Students can hardly avoid getting to know each other, and the dynamics of interaction seem to stabilize on quite different structures. Students feel free to call on other groups without being invited; they feel inspired, which in turn prompts them to seek more inspiration.

With respect to co-learning, the tight connection between spatial conditions and opportunities for professional inspiration from and learning with fellow students opens up questions concerning the development of learning competencies and collaborative competencies.

Over several semesters with project-based teaching carried out in SGR, students might, along with the main topics and purposes of their learning processes, learn how to carry out projects and share knowledge within strong, closed networks in which participants know each other well, both professionally and personally. Co-learning from project work in SGR, in other words, mightbe that students become very comfortable, efficient and specialized regarding learning and collaboration in persistent and stable social contexts. But they might face difficult conditions in terms of competencies to establish interactions conductive to learning with new and unfamiliar people and settings. In MGR, co-learning related to professional interaction and knowledge sharing in complex and loose-coupled networks faces far better conditions.

A couple of the informants express themselves on co-learning and the potential for the development of learning and collaborative competencies as follows: ‘I think you get a group with individual persons in MGR – positively meant – because, on your own, you also call on other groups, get rid of your problems, and get new ideas. Then, you are ready to re-enter your group with new energy’ (Q28); and ‘You become more open and “communicative” when you talk frequently with the other students’ (Q21).

Accepting Weick’s (2001) idea that professional work tends to be based on loose-coupled systems characterized by collaboration between several persons in ever-changing settings, one might ask whether SGR offers adequate conditions for the development of relevant learning competencies, or rather, whether it fits into past ideas of division of labor.

Conclusion and Perspectives on Virtual Classrooms

The two types of spatial conditions are clearly experienced as offering different conditions for learning. MGR offers higher complexity, which stimulates and inspires but also challenges students to process a high load of information. SGR provides fewer disturbances and enhanced focus on the project but challenges students actively to seek out information outside the group in order to avoid the risk of running round in circles.

One of the unsolved challenges in MGR is noise. Both students who prefer SGR and those who prefer MGR indicate that noise might be/is a problem in MGR. This is consistent with findings from other studies of different types of open-space offices.

Student descriptions of MGR as beneficial for mutual inspiration contradict other observations of open-space offices. The theoretical framework provides arguments for possible explanations. One, supported empirically in Keiding & Laursen (2008), is that students consider learning as the primary outcome of the project work.

Categorizing student descriptions of their experiences with MGR and SGR into the three dimensions of meaning (fact, temporal, and social dimension) reveal that the dimensions of fact and temporality do play a role in student experiences of inspirational interaction. However, the social dimension is the most important dimension with regard to opportunities for inspiration and knowledge-sharing with fellow students.

The experience of knowing other students and being a part of the community emerges as the difference that makes a difference for participation in professional interactions. In MGR, students spontaneously drop by because they know each other and experience themselves as a part of a community. In SGR, they hesitate to enter a room if the door is closed, because they experience themselves as intruders in a private area. Furthermore, the experience of ‘belonging to’ is described both as a premise for engaging in professional interaction and as a by-product of the interaction.

conditions. Although this research project clearly indicates that students find spatial conditions do make a difference for both individual and project learning, the interplay among spatial conditions, inspiration and learning cannot be interpreted as being the result of simple causal mechanisms. Rather, the interplay must be explored and interpreted from concepts of affordances and challenges. It also means that how students actually benefit from given spatial conditions cannot be guaranteed beforehand. But awareness of affordances and challenges is an important step to benefit from the first and to overcome the latter.

As the actual study concerns only one form of education, other forms of education and disciplines should be studied in order to generate more general insights on the interplay among the type of education, the participants and the spatial conditions.

Preliminary reflections (Keiding, 2009, 2010b) suggest that the concept of spatiality can be fruitfully expanded to virtual classrooms. Virtual classrooms can also be designed to be more or less open. If, for instance, a class is divided into groups with specific assignments or projects within a common topic, the virtual group rooms are often accessible only to members of the specific group and the teacher (e.g. Keiding & Vardinghus-Nielsen, 2004). In this case they, as rooms for learning and interaction, are not only closed, as known from SGR, but they are locked to prevent any kind of observation and irritation from outside. They can become very similar to SGR if provided with tools for ‘calling in’ or ‘knocking on the door’ - for instance, by sending a message to the room asking for permission to look inside. Finally, virtual rooms can be designed so that they are completely open for observation and/or contribution from outside – that is, so that the rest of the class can observe the communication within the room and comment on it. In this case, the virtual room will become very similar to MGR.

From at least one perspective, physical and virtual classrooms seem to face different conditions. In SGR and MGR, the interaction between students is evanescent, primarily based on oral communication. In contrast, virtual classrooms are based on different types of fixed/non-evanescent communication. In this sense, virtual classrooms might offer more stable contexts for learning and, as such, be less sensitive to timing. Inspiration may be sought whenever the learner is ready for it. How opportunities for mutual inspiration and co-learning are actualized and experienced in the virtual setting is, as I see it, worth further empirical study – for example, from the perspective of accessibility to information versus the handling of complexity in information load.

This study indicates that spatial conditions, whether in the form of physical or virtual structures (buildings, rooms), strongly influence formal, and maybe particularly informal, student-centred learning processes and afford very different contexts for learning processes. As a consequence, spatiality should be taken into consideration in theories of teaching and learning. Spatial conditions, virtual and physical, can be fruitfully addressed from a media perspective speaking to the specific conditions of the room and how these conditions mediate social interaction.

References

Bateson, G. (2000) Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Commission of the European Communities (2006) Commission Staff Working Document towards a European Qualification Framework for Lifelong Learning. Brussels.

http://ec.europa.eu/education/policies/2010/doc/consultation_eqf_en.pdf

Framework Provisions (2007) Faculties of Engineering, Science and Medicine, Alborg University, Denmark. http://en.ins.aau.dk/GetAsset.action?contentId=3839118&assetId=3891705

Frey, K. (1984) Die Projektmethode. Weinheim & Basel: Beltz.

Horst, S. & Misfeld, M. (Eds) (2010) Fremtidens undervisningsmiljø på universitetet. Baggrundsrapport. Institut for Naturfagenes Didaktik, Københavns Universitet & Institut for Didaktik, DPU, Aarhus Universitet.

http://www.ind.ku.dk/udvikling/projekter/undervisningsmiljo/baggrundsrapport-fremtidensundervisningsmilj_p_universitetet.pdf/

Keiding, T.B. (2005) Hvorfra min verden går. Et Luhmann-inspireret bidrag til didaktikken. PhD dissertation. Aalborg: Department of Education, Learning and Philosophy, Aalborg University.

http://www.learning.aau.dk/index.php?id=9064#c30283 (summary in English).

Keiding, T.B. (2007a) Learning in Context: but what is a learning context? Nordisk Pedagogik, 27(2), 138-149. Keiding, T.B. (2007b) Luhmann og reformpædagogik – om at afskrive eller genbeskrive

reformpædagogikkens grundsatser, in M. Paulsen & L. Qvortrup (Eds) Luhmann og dannelse. Copenhagen: Unge Pædagoger.

Keiding, T.B. (2008a) Projektmetoden – en systemteoretisk genbeskrivelse, Dansk Universitetspædagogisk Tidsskrift, 3(5), 22-29.

Keiding, T.B. (2008b) Inklusion og eksklusion i fleksibel undervisning, in P. Rasmussen & A. Aarup Jensen (Eds) Læring og forandring. Aalborg: Aalborg University Press.

Keiding, T.B. (2009) Spatial Conditions as an Unheeded Media in Teaching and Learning. Paper presented at European Conference on Educational Research, 28-30 August, in Vienna, Austria.

http://www.eera-ecer.eu/ecer-programmes/conference/ecer-2009/contribution/1280-1/?no_cache=1&cHash=99f69279fa

Keiding, T.B. (2010a) Observing Participating Observation – a re-description based on systems theory, Forum Qualitative Social Research, 11(3), article 11.

http://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/issue/view/35

Keiding, T.B. (2010b) From To Be Or Not To Be, To How To Be There. Paper presented at European Conference on Educational Research, 25-27 August, in Helsinki, Finland.

http://www.eera-ecer.eu/ecer-programmes/conference/ecer-2010/contribution/1856-1/?no_cache=1&cHash=b59a3ac498

Keiding, T.B. & Laursen, E. (2005) Interaktion og læring. Gregory Batesons bidrag. Copenhagen: Unge Pædagoger.

Keiding, T.B. & Laursen, E. (2008) Projektmetoden iagttaget. Metodens didaktik og anvendelse i

universitetsuddannelse. Department of Education, Learning and Philosophy, Aalborg University. http://www.learning.aau.dk/index.php?id=9065#c30292

Keiding, T.B. & Vardinghus-Nielsen, H. (2004) Inklusion/eksklusion: et perspektiv på en flexkasse på et studenterkursus, in H. Mathiasen (Ed.) Det virtuelle gymnasium: 2. del af følgeforskningsrapport om et udviklingsprojekt: Udviklingsprogrammet for fremtidens uddannelser. Copenhagen: Uddannelsesstyrelsen. Luhmann, N. (1990) The Individuality of the Individual, in N. Luhmann, Essays on Self-reference. New York:

Columbia University Press.

Luhmann, N. (1995a) Social Systems. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Luhmann, N. (1995b) Die operative Geschlossenheit psychischer und sozialer Systeme, in N. Luhmann, Soziologische Aufklärung, Bd. 6. Die Soziologie und der Mensch. Opladen: Vestdeutscher.

Luhmann, N. (1995c) Probleme mit operativer Schliessung, in N. Luhmann, Soziologische Aufklärung, Bd. 6. Die Soziologie und der Mensch. Opladen: Westdeutscher.

Luhmann, N. (2002a) The Cognitive Program of Constructivism and the Reality that Remains Unknown, in W. Rasch (Ed.) Theories of Distinction: redescribing the descriptions of modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Luhmann, N. (2002b) How Can Mind Participate in Communication? In W. Rasch (Ed.) Theories of Distinction: redescribing the descriptions of modernity. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press. Luhmann, Niklas (2002c) Das Erziehungssystem der Gesellschaft. Frankfurt am Main: Suhrkamp.

Maturana, H. & Varela, F. (1987) The Tree of Knowledge : the biological roots of human understanding. Boston: Shambhala.

Pejtersen J.H. (2006) Støj i storrumskontorer.

http://www.arbejdsmiljoforskning.dk/upload/JHP_10102006.pdf

Study Guide (2008) Aalborg University, Denmark. http://studyguide.aau.dk/workmethod/grouproom Waldström, C. & Lauring, J. (2006) Sociale netværk som barrierer for videndeling, Ledelse og Erhvervsøkonomi,

1, 28-40.