Family Structure

An Historical Perspective

Carolyn M. Moehling

a b s t r a c t

Cross-sectional studies find a positive relationship between a stateÕs welfare benefits and single motherhood. But is this evidence of a ‘‘welfare effect’’ or rather of cross state differences in social attitudes that influence both policy and behavior? This paper demonstrates that the spatial variation in welfare policy long preceded the spatial correlation of policy and behavior, undermining the social norm hypothesis. But the findings also raise doubts about the role that welfare policy played in the changes in family structure over the century. The correlation between welfare benefits and family structure only appears in 1970, and then only for whites.

I. Introduction

Between 1970 and 2003, the fraction of American families with chil-dren younger than 18 headed by single mothers more than doubled, rising from 12 to 26 percent (Fields 2003, 8). Policymakers and scholars have viewed this change with con-cern. Families headed by single mothers have high rates of poverty, and children raised in such families are more likely to drop out of school, have children out of wedlock, and have difficulties in the labor market as young adults (McLanahan and Sandefur 1994). In the search to explain this dramatic change in American family structure, much of the attention has been focused on the American welfare system. In most states, only fam-ilies headed by single parents are eligible for cash-assistance programs. This restric-tion, it is argued, promotes the formation of single-mother families.

Over the past 30 years, numerous studies have examined this ‘‘welfare effect’’ hy-pothesis and yielded a wide range of results. Moffitt (1998 and 2003) provides re-cent reviews of this literature. Time series evidence provides little support for the Carolyn M. Moehling is an associate professor of economics at Rutgers University. The author thanks Joseph Altonji, Timothy Guinnane, Caroline Hoxby, T. Paul Schultz, Christopher Udry, and Ebonya Washington and seminar participants at Lehigh University, Rutgers University, the University of Missouri, and Williams College for helpful comments and suggestions. The author takes all responsibility for errors and omissions. The data used in this article can be obtained beginning August 2007 through July 2010 from Carolyn Moehling, Department of Economics, Rutgers University, 75 Hamilton Street, New Brunswick, NJ 08901. cmoehling@econ.rutgers.edu

[Submitted July 2005; accepted May 2006]

ISSN 022-166X E-ISSN 1548-8004Ó2007 by the Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System

hypothesis: During the 1970s and 1980s when the number of single-mother families was increasing most rapidly, real welfare benefits were falling (Moffitt 1998, p. 60). However, cross-sectional studies have found that family structure varies with a stateÕs level of benefits. In states with higher benefits, women have been found to be less likely to be married (Schultz 1994 and 1998) and more likely to be single mothers (Moffitt 1994) and household heads (Hoynes 1997). But the cross-sectional evidence is tenuous at best. The estimated welfare effect varies with the data used and the specification of the model, particularly for blacks. In general, the evidence of a wel-fare effect is stronger for whites than for blacks even though single motherhood is much more prevalent among blacks (Moffitt 1998, p. 68).

Repeated cross-section and longitudinal studies produce an even more compli-cated picture of the relationship between family structure and welfare benefits. Mof-fitt (1994) and Hoynes (1997) find that controlling for state fixed effects causes the relationship between benefit levels and single motherhood for whites to disappear. As both authors document, this change occurs because state fixed effects are positively correlated with state benefit levels. In other words, states that offer high levels of benefits are those with high rates of female headship, and states that offer low levels of benefits are those with low rates of female headship. The disappearance of the benefit level effect when state fixed effects are included in the model indicates that white female headship does not respond to the year-to-year changes in the level of benefits. But the basic conclusion is still that states offering the most generous wel-fare benefits have the highest rates of female headship among whites. The same cor-relation, however, does not exist for blacks. Both Hoynes and Moffitt find no correlation between benefit levels and state fixed effects for black female headship, and adding state fixed effects has no effect on the estimated relationship between welfare benefit levels and black female headship.

As Moffitt pointed out in his 1994 paper, these results raise as many questions as they answer (p. 634). Namely, what are ‘‘state fixed effects’’ and how do we interpret them in the context of the debate on the impact of welfare policy on family structure?1A stan-dard explanation is that fixed effects capture differences across states in population com-position and attitudes toward single motherhood. Such factors would influence both the prevalence of single motherhood and the relative support for the welfare system. For example, a ‘‘strong two-parent family tradition’’ in a state will lead to fewer single mothers and less support for welfare programs. But such explanations present other questions. How did the ‘‘strong two-parent family tradition’’ develop? Did this tradition precede and determine the limited support for welfare programs in the state? Or did wel-fare policy itself shape the social norms in a state? And why does the correlation be-tween state fixed effects and welfare policy exist only for whites and not for blacks?

This paper addresses these issues by examining the relationship between welfare programs and family structure from 1910 to 1970. The majority of studies to date have focused on the period from 1968 forward.2 This focus is natural given the 1. State fixed effect models also have been criticized on methodological grounds (Moffitt 1998, p. 58-59). When the methodology is applied to yearly data, the welfare effect must be identified by yearly changes in benefits and single motherhood. The transition into and out of single motherhood, however, takes time, and may respond only with a lag to changes in benefit levels.

changes in family structure that took place in the 1970s and 1980s. But the seeds of those changes were planted much earlier, especially for blacks. Single motherhood was on the rise among blacks as early as the 1940s and began to rise among whites in the 1950s. Moreover, the bias toward single-parent families in the American wel-fare system long precedes these changes. The first public assistance programs tar-geted at single mothers were mothersÕ pensions that were enacted by state legislatures beginning in the 1910s. These early laws set the stage for the tremendous spatial variation in welfare generosity we observe today. The variation in these early programs is striking not only for its extent but also for how closely it corresponds to the variation observed throughout the history of the federally mandated Aid to Fam-ilies with Dependent Children (AFDC) program created by the Social Security Act in 1935. The most generous states in 1919 were the most generous states in 1940 and are still among the most generous states today. If a stateÕs relative welfare generosity is determined by social norms and attitudes toward single motherhood, those norms and attitudes were already in place in the first half of the twentieth century. The ques-tions are: Did state differences in welfare policy in this period lead to cross-state differences in behavior or did they reflect preexisting differences in behavior? Or did the cross-sectional relationship between welfare policy and behavior arise only after the dramatic changes in family structure had begun?

II. The Long History of Cross-State Variation in

Welfare Generosity

Public aid to single mothers had been discussed as early as the late-nineteenth century, but the real push for such programs began with the 1909 White House Conference on the Care of Dependent Children. Much of the discussion at the conference centered on the plight of single mothers who were separated from their children by poverty alone. In fact, many charitable organizations in the early twentieth century encouraged impoverished mothers to place their children in orphanages or fos-ter care (Leff 1973, p. 399). The irony, noted by many conference participants, was that the cost for caring for children in institutions or foster families was frequently much greater than what it would have cost to care for these children in their own homes.

Illinois passed the first statewide mothersÕpension law in 1911 authorizing county governments to provide grants to mothers with dependent children. Other states quickly followed. By the end of 1919, 39 states had enacted mothersÕpension laws. State legislation did not establish state programs, but rather authorized local govern-ments—usually counties—to provide cash grants to destitute parents. Most, in fact, did not even provide state funds for pensions. But state legislation provided the gen-eral parameters under which these programs had to operate.

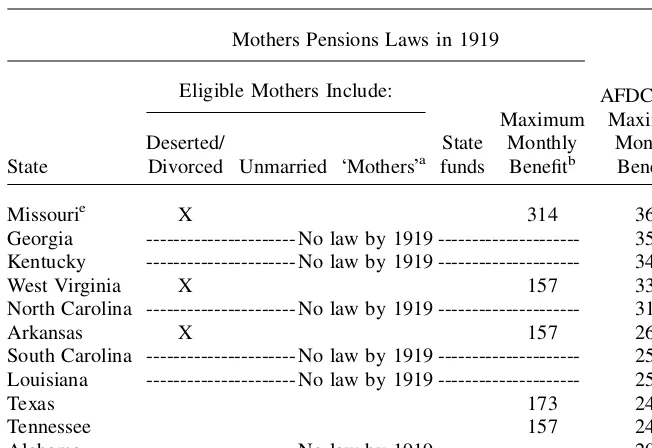

Table 1

Provisions of State Mothers’ Pension Laws, 1919 and AFDC Benefits, 1996

Mothers Pensions Laws in 1919

Divorced Unmarried ÔMothersÕa

Vermont X X 203 760

California X 471 756

New York No max.c 734

Massachusetts X X No max. 714

Washington X 196 686

Connecticut X No max.d 683

Rhode Island --- No law by 1919--- 678

Minnesota X X 275 664

Wisconsin X X 275 661

New Hampshire X X No max. 655

unmarried mothers, but a number of states—Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Wash-ington, Colorado, Pennsylvania, Maine, North Dakota, and Indiana—had legislation that covered ‘‘mothers of dependent children’’ without reference to marital status. Laying the foundation for the variation in benefit levels that characterizes welfare pro-grams today, state laws also varied in the maximum grants they allowed for families of different compositions. In 1919, the maximum monthly grant specified for a family consisting of a mother and three children was $18ð$141 in 2000 dollars) in New Jersey and $40ð$314 in 2000 dollars) in neighboring Pennsylvania. The New York law stated that the benefits paid ‘‘must not exceed what it would cost to care for chil-dren in an institutional home.’’ The Massachusetts law specified no maximum, leav-ing it to local governments to determine grant amounts (U.S. WomenÕs Bureau 1919). MothersÕ pensions programs as implemented never lived up to their legislative success. Many counties, most of them rural, refused to establish programs claiming that no eligible families lived within their boundaries (Leff 1973, p. 413). MothersÕ Table 1(continued)

Divorced Unmarried ÔMothersÕa

Missourie X 314 366

Georgia --- No law by 1919 --- 353 Kentucky --- No law by 1919 --- 348

West Virginia X 157 334

North Carolina --- No law by 1919 --- 317

Arkansas X 157 264

South Carolina --- No law by 1919 --- 258 Louisiana --- No law by 1919 --- 250

Texas 173 242

Tennessee 157 242

Alabama --- No law by 1919 --- 207 Mississippi --- No law by 1919 --- 154

Sources: U.S. Women’s Bureau, (1919); U.S. House of Representatives (1996).

a. Legislation covered ‘‘mothers of dependent children’’ without reference to marital status. b. Maximum benefit levels refer to four-person families and are denominated in 2000 dollars.

c. New York’s legislation stated that the benefits paid ‘‘must not exceed what it would cost to care for child in an institutional home.’’

d. The Connecticut legislation specified the amounts that could be provided for food, fuel and clothing per week, but allowed for a ‘‘reasonable monthly allowance’’ for rent and ‘‘special allowances’’ for sickness and death.

pensions programs, where they did exist, were generally underfunded. The grants provided were small and typically did not even cover the basic expenditure require-ments of families (U.S. ChildrenÕs Bureau 1923).

MothersÕpensions programs also served a very select population. Despite the fact that during the 1920s most states extended coverage to divorced and deserted women, 82 percent of pension recipients in 1931 were widows (U.S. ChildrenÕs Bu-reau 1933, p. 11). Most striking, though, is the degree to which the black population was underserved by these programs. Single motherhood was more prevalent in the black than the white population even in the early twentieth century (Gordon and McLanahan 1991; McDaniel 1994; Morgan et al. 1993; Ruggles 1994), but only 3 percent of mothersÕpensions recipients in 1931 were black (U.S. ChildrenÕs Bureau 1933, p. 13). The limited presence of blacks on the pension rolls was first and fore-most a function of the concentration of blacks in the South. Southern states were slow to enact mothersÕpension laws, and when they did, geographic coverage tended to be quite limited. In 1931, only three of MississippiÕs 82 counties and one of KentuckyÕs 120 counties actually paid out any mothersÕaid grants (ibid, p. 9). Over half of all blacks lived in states that either had no mothersÕpension legislation or had mothersÕpensions programs in fewer than 10 percent of their counties.

The concentration of blacks in areas without mothersÕpension programs was not a geographic accident. The hesitance of Southern rural counties to establish social wel-fare programs is often attributed to racism and the desire to limit public services ex-tended to the black rural poor. Alston and Ferrie (1985), however, have argued that this was a manifestation of class rather than race discrimination: The objective of policymakers and landowners was to keep labor costs low. But even if the motivation was class-based, the outcome had a clear racial dimension: Blacks had significantly less access to public welfare programs than did whites.

Even when blacks lived in jurisdictions with mothersÕ pension programs, they tended to be underrepresented on the rolls (U.S. ChildrenÕs Bureau 1933, pp. 26– 27). It is difficult to determine to what degree this was due to the reluctance of blacks to apply for aid and to what degree this was due to the low probability of blacks re-ceiving aid conditional on applying for it. Many jurisdictions kept little data on the characteristics of women who applied and were denied aid.3A contributing factor was the more limited access black women had to information on these programs. Set-tlement workers in Chicago made a concerted effort to spread information about mothersÕpensions within the black community, and, as a result, the number of black mothers on the pension rolls grew during the 1920s. Nonetheless, blacks still were underrepresented relative to their share in the population (Goodwin 1997, p. 164).

The push for a federal program was motivated primarily by the disparities both within and across states in coverage and benefit levels, disparities that had only wid-ened with the state and local government budget crises generated by the Great De-pression.4However, the proposals were not for a federally administered program, but rather a federally mandated and state-administered program. The consolidation was to be done at the level of the state. States would be required to provide state monies to fund the program, and state agencies, rather than local government units, would

3. See for instance, Stein-Roggenback (2005, p. 302).

determine eligibility and benefit levels. This consolidation was intended to eliminate the variation in aid within states. The variation between states was to be addressed by the use of federal funds. Grace Abbott argued, ‘‘A federal fund would be an instru-ment for improving the standards in backward states and would tend to equalize costs’’ (1934, p. 210).

Linda Gordon (1994) suggests that the resistance to push for a federally adminis-tered program was due to the limited power Abbott and her colleagues at the Chil-drenÕs Bureau felt they had within the federal government in the 1930s. But she also claims it reflected a long-standing preference to work through state welfare agencies (pp. 257–58). The system they proposed would build on the structure they had helped construct over the previous two decades.

The outcome of these proposals was the Aid to Dependent Children (ADC) program (later renamed Aid to Families with Dependent Children—AFDC), which was enacted as part of the Social Security Act of 1935. This program was, as Abbott and others had called for, federally mandated but state administered. Federal funding came in the form of matching grants. Under the original legislation, the federal government would pay one-third of the payments up to $18 for the first dependent child and one-third of the payments up to $12 for each additional dependent child in a home. In 1940, the federal share was increased from one-third to one-half.

ADC did overcome some of the limitations of mothersÕ pensions. The recipient rolls expanded quickly. Between 1935 and 1938, the recipient rolls more than dou-bled from 116,817 families to 279,657 families (Bucklin 1939, p. 33). As these rolls expanded, the composition of families served changed as well. By 1948, 77 percent of recipient families were the families of nonwidows, and 30 percent were black (Alling and Leisy 1950).

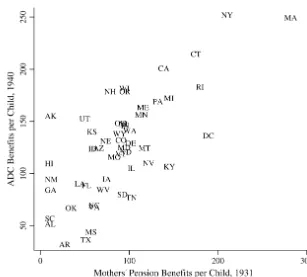

But the substantial cross-state variation in benefit levels remained. The federal leg-islation left benefit level determination entirely up to the states, and the levels states chose were strongly correlated with the levels of benefit payments made under moth-ersÕpension programs. Figure 1 plots the average monthly benefits per child paid in 1940 under ADC against those paid in 1931 under mothersÕpensions. The states near the top of the distribution in 1931 were still near the top in 1940, and those that were at the bottom, stayed at the bottom. The correlation between the average benefit pay-ments under the two systems is 0.72.

The degree of welfare generosity established in the early mothersÕpension laws has proved to be quite persistent. Cross-state variation in benefit levels persisted throughout the history of the ADC/AFDC program even as the federal matching for-mula changed and food stamps and Medicaid were added to the benefit package.5 The correlation between the maximum monthly ADC benefits paid to families of four in 1940 and the maximum monthly AFDC benefit guarantee for a family of four in 1996, the last year of the program, was 0.69. Table 1 provides data on the AFDC maximum benefits to a family of four in 1996 in addition to the provisions of state

mothersÕpension laws. The states are ordered by 1996 benefit levels. Of the ten states with the highest welfare benefits in 1996, seven provided state funds for mothersÕ

pensions, and three extended coverage to mothers of dependent children without ref-erence to marital status. Likewise, the states with the least generous benefits in 1996 had the least generous mothersÕpensions programs in 1919. Six of the ten states with the lowest AFDC benefits in 1996, in fact, had enacted no mothersÕpension legisla-tion by 1919.

The other carry-over from mothersÕpensions to ADC was the disadvantaged status of blacks. Black participation, as noted earlier, increased substantially with the ad-vent of the federally mandated program. But blacks were concentrated in low-benefit states and this again was not simply an accident of geography. In fact, the degree of discretion given to states to set benefit levels in the federal program has been attrib-uted to the racist concerns of Southern legislators. The legislation originally pro-posed would have required states to pay a minimum benefit compatible with ‘‘health and decency.’’ This clause, however, never made it out of committee. The stated concern of many legislators was that such a clause would impose financial obli-gations on a state without any regard to its financial circumstances. But Edwin Witte, Figure 1

who served as the executive director of the Committee of Economic Security, claimed that Southern senators feared the clause would allow the federal government to inter-fere with how their states handled the ‘‘Negro question’’ (Congressional Research Ser-vice 1982). As passed, the legislation only required ‘‘each state to furnish financial assistance, as far as practicable under the conditions in each state, to needy children.’’ The Social Security Board interpreted this wording as merely requiring that each state establish a system for measuring the ‘‘needs’’ of its public assistance recipients. The benefits a state paid did not have to correspond to these needs (ibid, p. 11).

Other aspects of state programs were specifically designed, or implemented in such a way as to discriminate against black single mothers. Many states had ‘‘suit-able home’’ or ‘‘substitute parent’’ policies, which they implemented selectively to keep black women off their welfare rolls (Bell 1965; Gilens 1999, p. 105; Grogger and Karoly 2005, p. 11). In the summer of 1960, Louisiana decided to redefine what constituted an ‘‘unsuitable’’ home and dropped over 6,000 families and 23,000 chil-dren from its ADC program. Before the change in policy, 66 percent of all chilchil-dren receiving ADC in Louisiana had been black. But 95 percent of the children who were dropped were black (Bell 1965, pp. 137–38). The public furor that followed did lead to change, however. Over the 1960s and 1970s, changes in federal policies and court rulings limited statesÕdiscretion in determining eligibility for cash assistance.6But during the early years of ADC, as in the era of mothersÕpensions, blacks were rel-atively underserved.

The primary theme in the history of welfare programs over the twentieth century is continuity. The relative welfare generosity across states has been fairly persistent. This persistence has an important implication for the study at hand. If the variation across states in welfare generosity reflects differences in social norms and attitudes toward single motherhood, these differences were likely already in place in the early twentieth century and were certainly in place by beginning of the ADC program. If such differences drive the cross-sectional variation in family structure observed to-day, then similar variation, or at least the seeds of that observed toto-day, should also have been present during the mothersÕpension era or at least during the early years of ADC. The other continuity, at least up until the 1970s, was the disadvantaged po-sition of blacks in welfare programs.

III. Family Structure, 1910 to 2000

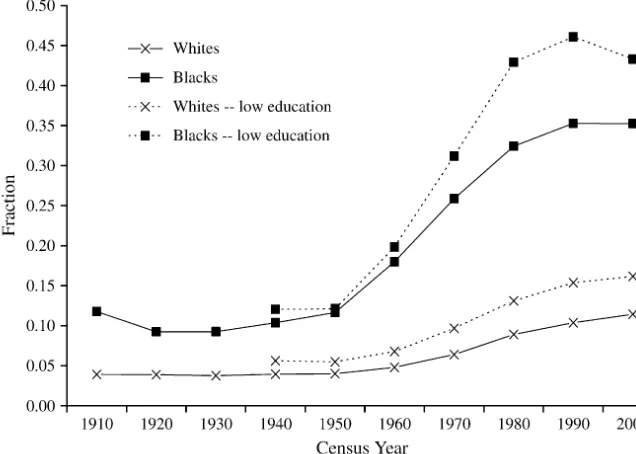

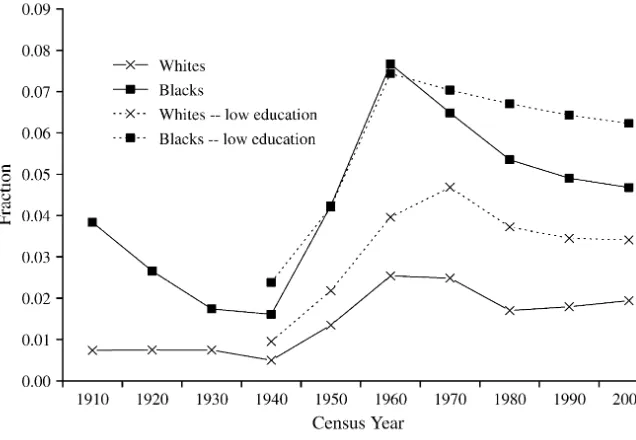

While the history of welfare programs for single mothers in the twen-tieth century is one of continuity, the history of family structure is one of change. Figures 2–4 plot the rates of single motherhood, divorce and separation, and unmarried fertility for women aged 20–44 from 1910–2000.7Single motherhood—defined as

living with oneÕs own child younger than 18 and no spouse—nearly tripled for both blacks and whites between 1910 and 2000. This was due to both increases in divorce and separation and increases in births to unmarried women. For the years 1940 to 2000 for which we have data on schooling, the figures also present the trends in fam-ily structure for women in the bottom quartiles of the black and white education distributions.8The increases in single motherhood, divorce and separation, and un-married fertility were even more dramatic among the least-educated women. By 2000, 16 percent of white women and 44 percent of black women in the lowest ed-ucation quartiles were single mothers.

The changes in American family structure illustrated in Figures 2–4 have been documented and discussed many times before. But it is worth pointing out some fea-tures of these changes that have received relatively little attention. Although the most dramatic changes in single motherhood took place after 1960, the seeds of these changes were planted earlier. Single motherhood began trending upward for blacks in the 1940s and for whites in the 1950s. These increases were preceded by a few decades of steady increases in divorce and separation. And the most dramatic changes in the birthrate to unmarried women took place in the 1940s and 1950s. The question is: Can we connect these changes to welfare policy?

Figure 2

Single Motherhood, Women Aged 20 to 44, 1910–2000

IV. Spatial Variation in Welfare Generosity and

Family Structure

Although the studies to date have produced a wide range of findings, the balance of the evidence, at least for whites, indicates that cross-state differences in family structure have been correlated with cross-state differences in benefits since the 1970s. The objective of this paper is to search for the origins of this correlation. As documented earlier in the paper, the targeting of single mothers in public welfare programs dates all the way back to the 1910s with the advent of mothersÕpensions laws, and those early laws exhibited the spatial variation in welfare generosity that characterizes the welfare system in place today. Did the spatial correlation between family structure and welfare generosity originate with these laws? Or do the origins of this correlation lie in the early years of the ADC program?

I begin by looking at the impact of the provisions of early mothersÕpension laws on changes in family structure between 1910 and 1920. Only in this period can we use a ‘‘natural experiment’’ approach to try to identify the effects on family structure of tar-geting cash assistance to single mothers. I use difference-in-differences models to test whether states that enacted more generous laws experienced larger changes in single motherhood than states that enacted less generous laws. The results of these models also provide a test of the ‘‘state fixed effects’’ hypothesis because they will reveal if mothersÕ

pension provisions were related to any preexisting spatial variation in family structure. Figure 3

Then I use data from the 1940 to 1970 censuses to examine the evolution of the cor-relation between family structure and welfare benefits in the ADC/AFDC program. A. Data

I use individual level data from the 1910, 1920, and 1940 to 1970 federal censuses made available as part of the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (IPUMS).9For the 1910 census, the IPUMS data set is a 1-in-250 national random sample of enu-merated households. The IPUMS data sets for the other five censuses are 1-in-100 national population samples.10The 1950 census, however, asked certain key ques-tions (for example, ‘‘number of years of schooling’’) only of individuals who fell on what was referred to as the ‘‘sample lines’’ on the enumeration forms. Hence, I must use only the sample-line data of the 1950 sample.

The base sample for analysis is all noninstitutionalized women aged 20 to 44 living in the contiguous 48 states. But for 1940 to 1970, I also consider the behavior of women in the bottom quartiles of the white and black education distributions.11These women Figure 4

Birthrates of Single Women Aged 20–44, 1910–2000

9. IPUMS data and supporting documentation is available online at www.ipums.umn.edu. The IPUMS con-tains several samples for the 1970 census each containing slightly different sets of data. I use the ‘‘state, form 1’’ sample.

would have had the most circumscribed opportunities in the labor market and would have been the most likely to participate in welfare programs. And as shown above, these groups experienced the most dramatic changes in family structure. Studies of welfare program effects and participation in recent decades usually define the low-skilled group as high school dropouts. But this definition is not appropriate here. In 1940, more than 60 percent of white women and almost 90 percent of black women had less than a high school education. Using a lower schooling level as the cutoff also is problematic though because of the dramatic increases in schooling between 1940 and 1970. By 1970, only 26 percent for whites and 48 percent of blacks had less than a high school education.12

I look at the three measures of family structure that receive the greatest amount of discussion in the welfare debate: single motherhood, divorce and separation, and births to single mothers. The census data allow for single motherhood to be identified in a straightforward and consistent way across all census years: A woman is desig-nated as a single mother if she was living with an own child younger than 18 and had no spouse present.13Changes in census enumeration practices over time, however, pose challenges for defining the other two measures.

The challenge for defining the rate of marital breakup over the century is that the census did not allow individuals to report their marital status as ‘‘separated’’ until 1950. In the earlier censuses, separated women would have been reported as ‘‘mar-ried’’ with absent spouses. Only looking at the rate of divorce, though, will overstate the change in marital patterns over the century. In the early years of the century, divorce still carried significant social stigma. Many couples who wished to sever their relationships never sought official divorces but rather just lived apart. Hence, 12. I also estimated models in which I defined the low-education group as high school dropouts to be con-sistent with studies done using more recent data. These models yielded the same general conclusions as those presented in the paper.

to create a consistent measure of marital breakups over the century, women who were reported in the census as married but with an absent spouse are grouped with women reported as divorced or separated. This leads to an overstatement of marital breakups because some women living apart from their husbands may have been doing so tem-porarily and still receiving support from them. But excluding women with absent spouses would lead to an understatement of marital breakup before 1950 and hence to a biased picture of the change in marital patterns over the century. The probability of divorce or separation is examined in the context of women at risk to be divorced or separated: that is, women who were ever-married and not widowed.

The challenge in looking at births to single women in the census data comes from the fact that until 1970, fertility questions (‘‘the number of children ever born’’) were only asked ofever-marriedwomen. The data for the earlier censuses do not contain fertility information on never-married women.14Therefore, I use as a measure of the birth rate, the proportion of women who are identified in the census as the mother of a child younger than one. This measure will understate the number of births in that it will miss children who died in the first year of life and those who are living apart from their mothers. But it will capture at least some births to never-married women. It also has the advantage of measuring current fertility. The number of children ever-born captures the outcome of fertility decisions made over a womanÕs lifetime to date. Some of those decisions may have been made when the woman was in a very different situation (and even state of residence) than she is found in the census. For widowed, divorced, and separated women, we cannot determine whether births took place within or outside of marriage. The same criticism can be leveled at looking at the current fertility of these women, but the scope for error is much smaller. B. Family Structure and State MothersÕPensions Laws, 1910 and 1920

Most commonly, difference-in-differences takes the form of examining the differ-ences in an outcome variable in jurisdictions that enacted a particular policy and in those that did not. But as noted above, 39 states enacted mothersÕpensions between 1910 and 1920, and those that did not were concentrated in the South. So the more interesting issue is how family structure varied with the provisions, rather than the timing, of state legislation. MothersÕ pension legislation had many different types of provisions. I focus on the three that I believe best capture the relative generosity of the state legislation: the extension of coverage to mothers other than widows

(NONWID), the provision of state funds (STFUNDS), and the maximum grant for

a family with three children converted to 2000 dollars (MAXBEN).15Six states either did not have legislated maximum benefit levels in 1919 or had flexible maximums: Colorado, Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and New York. To account for this, I include an indicator variable equal to one if a state had no binding maximum benefit level (NOMAX).

14. A measure of the number of children these women have had can be constructed by looking at the chil-dren living in her household on the census date. But this will understate the number of births because it will miss children living elsewhere and children who are deceased.

I estimate the following linear probability model:16

ð1Þ FAMSTis¼a+b1NONWIDs+b2STFUNDSs+b3NOMAXs+b4MAXBENs

+g1YR1920isNONWIDs+g2YR1920isSTFUNDSs

+g3YR1920isNOMAXs+g4YR1920isMAXBENs

+dYR1920is+xis#h+eis

where FAMSTis represents the family structure measure for woman i in state s, YR1920isis an indicator that an observation is from 1920, andxisis a vector of con-trol variables.

The coefficients on the interactions between the legislative provisions and YR1920, thegÕs, represent the treatment effects. These coefficients capture the var-iation in family structure that was related to the provisions of state laws onlyafterthe laws were enacted. The hypothesis that more generous welfare provisions encour-aged women to become or remain single mothers implies that the probability of sin-gle motherhood (or divorce and separation or births to sinsin-gle women) should have been higher in states with more inclusive eligibility rules and states that provided state funding for mothersÕpensions, and should have been positively related to the maximum benefit level. In other words, we would expectgÕs to be positive.

The coefficients on the uninteracted legislative provisions, thebÕs, capture the var-iation in family structure that was related to the provisions of state laws both before and after the laws were enacted. These coefficients will indicate if there was any cor-relation between family structure in a state in 1910 and the provisions of the mothersÕ

pension legislation that state enacted between 1910 and 1920. They therefore provide a test of the ‘‘state fixed effect’’ hypothesis of the origins of the cross-sectional cor-relation between welfare generosity and family structure. If welfare generosity reflected preexisting spatial differences in behavior, thebÕs will be positive.

The model described in Equation 1 is not, however, complete. The discussion so far has ignored another dramatic legislative movement of the 1910s that also may have been related to family structure. Over the same period that states were enacting moth-ersÕpension legislation, they were also enacting workersÕcompensation legislation. This legislation established guaranteed payments of benefits to workers injured on the job and the families of workers killed in job-related accidents. Like mothersÕ pen-sion laws, workersÕcompensation laws diffused rapidly across the states. Between 1910 and 1920, 40 states enacted workersÕcompensation legislation. Because workersÕ com-pensation guaranteed widows of men killed in industrial accidents a set level of bene-fits, these laws too could have been related to the prevalence of single motherhood in a state. So also included among the law variables is a measure of the generosity of fatal benefits available under a stateÕs workersÕcompensation program and its interaction with the year 1920 indicator variable. The measure used is the ratio of the present value of fatal benefits to annual earnings as found in Fishback and Kantor (2000, pp. 209–10). The control variables included in the estimated models are similar to those used by Moffitt (1994) in his study of single motherhood in the 1970s and 1980s. The personal characteristic variables include a womanÕs age and age-squared and indicators for

whether she was illiterate or foreign-born. Also included is an indicator variable for whether a woman lived within a metropolitan area. Like Moffitt, I include variables capturing the sectoral distribution of employment in the state of residence: the percent-ages of a stateÕs employment in manufacturing, trade, services, public service (not elsewhere classified), and clerical jobs. The distribution of employment in a state was highly correlated with the labor market opportunities of women in that state. Moreover, it may have been related to the political climate in the state and, hence, influenced the type of mothersÕpension legislation enacted. To capture differences in income levels across states, I include a measure of per capita personal income.17 Fi-nally, I include the ratio of females to males in a state to account for differences in the availability of males and hence marriage market conditions. Descriptive statistics for these variables are provided in Appendix Table A1. I correct the standard errors for possible clustering by state due to the use of state-level variables in the analysis.

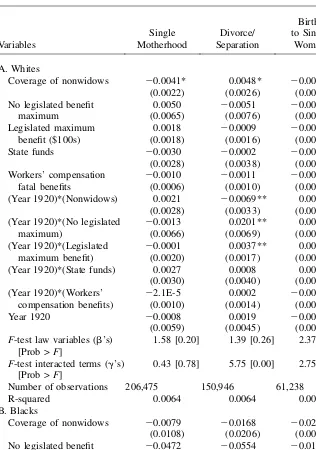

Table 2 presents the coefficients on the legislative variables from the estimated models. States that enacted more generous mothersÕ pension laws did not see increases in either black or white single motherhood between 1910 and 1920. The coefficients on the interactions between the 1920 indicator variable and the law pro-vision variables were jointly statistically insignificant as well as being individually insignificant.18 However, more generous legislation was associated with increases in divorce and separation and births to single women over the decade. For both blacks and whites, divorce and separation increased in states that specified no max-imum benefit level relative to those that did, and for whites, the probability of divorce and separation was also positively related to the legislated maximum benefit levels. States that extended eligibility to mothers other than widows saw increases in single births relative to states that did not.

The evidence of treatment effects would seem to be surprising given the limited scope of mothersÕ pension programs in the 1910s. These effects are perhaps best interpreted as ‘‘glow’’ effects: The attention focused on single mothers in the move-ment to enact these laws and the differences in the tenor of debate in different states may themselves have had an effect on attitudes and behaviors.

Table 2, however, also indicates that the cross-state differences in mothersÕpension laws enacted reflected preexisting cross-state differences in family structure. But contrary to beliefs that relative welfare generosity was positively related to the de-mand for welfare assistance in the state, the balance of the evidence indicates this relationship was negative: states that enacted more generous mothersÕpension laws tended to have lower rates of single motherhood and single births. The only esti-mated effect that suggests a positive relationship between need and welfare generos-ity is the positive coefficient on the indicator for the coverage of nonwidows for white divorce and separation. But in this case, the coefficient on the interaction term is negative, indicating that divorce and separation actually decreased more between 1910 and 1920 in these states than in states that extended coverage only to widows.

Table 2

Estimated Effects of Mothers’ Pension Legislation Provisions: Difference-in-Difference Models

Coverage of nonwidows 20.0041* 0.0048* 20.0018

(0.0022) (0.0026) (0.0015)

State funds 20.0030 20.0002 20.0016

(0.0028) (0.0038) (0.0014)

Workers’ compensation fatal benefits

20.0010 20.0011 20.0002

(0.0006) (0.0010) (0.0004)

(Year 1920)*(Nonwidows) 0.0021 20.0069** 0.0030*

(0.0028) (0.0033) (0.0015)

(Year 1920)*(State funds) 0.0027 0.0008 0.0020

(0.0030) (0.0040) (0.0018)

(Year 1920)*(Workers’ compensation benefits)

22.1E-5 0.0002 20.0003

(0.0010) (0.0014) (0.0006)

Year 1920 20.0008 0.0019 20.0038

(0.0059) (0.0045) (0.0025)

F-test law variables (b’s) [Prob >F]

1.58 [0.20] 1.39 [0.26] 2.37 [0.07] F-test interacted terms (g’s)

[Prob >F]

0.43 [0.78] 5.75 [0.00] 2.75 [0.04] Number of observations 206,475 150,946 61,238

R-squared 0.0064 0.0064 0.0019

B. Blacks

Coverage of nonwidows 20.0079 20.0168 20.0210**

(0.0108) (0.0206) (0.0081)

No legislated benefit maximum

20.0472 20.0554 20.0111

(0.0300) (0.0484) (0.0217)

Legislated maximum benefit ($100s)

20.0080 20.0085 0.0033

These findings, in combination to the evidence on the persistence in relative wel-fare generosity presented earlier in the paper, call into question standard social norm explanations of why estimated ‘‘state fixed effects’’ would be positively correlated to welfare benefit levels. The relative generosity of these earliest cash-assistance pro-grams for single mothers was negatively related to single motherhood, divorce and separation, and births to single women. Rather than social norms driving both policy and behavior, here, policy seems to have been set in opposition to social norms at least as manifested in behavior.

The data in Table 2 do not reveal many substantive differences in the experiences of blacks and whites in states that enacted mothersÕpension laws between 1910 and 1920. But as noted above, most blacks still lived in the South during this decade and many Southern states did not enact mothersÕpension laws before 1920. Differences in the experiences of blacks and whites may have been more strongly related to the timing of enactment in Southern states. Table 3 presents the results of more standard difference-in-difference models using data from only the Southern states. Here we Table 2(continued)

State funds 20.0097 20.0320 20.0159**

(0.0137) (0.0257) (0.0076) Workers’ comp. fatal benefits 0.0005 0.0037 0.0001

(0.0039) (0.0038) (0.0026)

(Year 1920)*(Nonwidows) 20.0009 20.0063 0.0284**

(0.0122) (0.0187) (0.0103)

(Year 1920)*(State funds) 0.0076 0.0135 20.0016

(0.0163) (0.0299) (0.0094) (Year 1920)*(Workers’

comp. benefits)

20.0008 20.0061 20.0027

(0.0036) (0.0049) (0.0031)

Year 1920 20.0078 20.0074 0.0043

(0.0164) (0.0269) (0.0129) F-test law variables (b’s)

[Prob >F]

1.49 [0.23] 1.16 [0.35] 4.70 [0.00] F-test interacted terms (g’s)

[Prob >F]

2.13 [0.10] 2.31 [0.08] 2.39 [0.07]

Number of observations 12,987 9,608 4,449

R-squared 0.0100 0.0199 0.0090

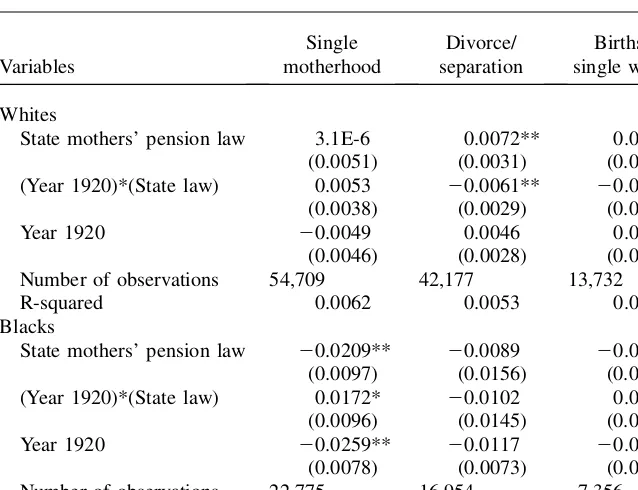

find evidence of treatment effects: Black single motherhood and single births in-creased in the Southern states that enacted mothersÕpension laws of any type relative to those that did not. But more striking are the differences in family structure that existed before the enactment of mothersÕ pension laws: The Southern states that enacted mothersÕpension legislation between 1910 and 1920 had lower rates of black single motherhood, but higher rates of divorce and separation and single births for whites. This reinforces the theme developed above that race has long played a role in the determination of welfare policy.

C. Family Structure and ADC/AFDC, 1940–70

The relative generosity of early mothersÕpension laws was negatively, rather than positively, related to the prevalence of single motherhood and divorce and separation in a state. But the difference-in-difference models indicate that these early laws had some ‘‘treatment’’ effects. Divorce and separation and births to single mothers in-creased between 1910 and 1920 more in the more generous states than in the less generous states. The question is: Did the experiences with mothersÕ pensions lead Table 3

Enactment of Mothers’ Pensions Laws in Southern States: Difference-in-Differences Model

State mothers’ pension law 3.1E-6 0.0072** 0.0073**

(0.0051) (0.0031) (0.0035)

(Year 1920)*(State law) 0.0053 20.0061** 20.0060

(0.0038) (0.0029) (0.0036)

Year 1920 20.0049 0.0046 0.0031

(0.0046) (0.0028) (0.0036)

Number of observations 54,709 42,177 13,732

R-squared 0.0062 0.0053 0.0044

Blacks

State mothers’ pension law 20.0209** 20.0089 20.0043

(0.0097) (0.0156) (0.0083)

(Year 1920)*(State law) 0.0172* 20.0102 0.0165**

(0.0096) (0.0145) (0.0081)

Year 1920 20.0259** 20.0117 20.0112**

(0.0078) (0.0073) (0.0053)

Number of observations 22,775 16,954 7,356

R-squared 0.0108 0.0125 0.0075

to a cross-sectional relationship between welfare benefits and single motherhood in the early years of the ADC/AFDC program? I examine this by estimating cross-sectional models of family structure for 1940 to 1970.

Most of the studies of the impact on AFDC on family structure have used data from 1968 forward. An exception is Ruggles (1997) who examined this relationship using data from 1940 and 1990. He found that the positive cross-sectional correlation between welfare benefits and single motherhood did not emerge until 1980. How-ever, Ruggles estimated models which pooled blacks and whites and assumed that the welfare effect did not differ by race. But as noted above, a key finding in the lit-erature on welfare policy and family structure is the different patterns observed for blacks and whites (Moffitt 1998, p. 68). For all but one of the models presented in this paper, Wald tests led to the rejection of specifications that pooled blacks and whites.19 In addition, Ruggles only estimated models for the general population. But as a number of studies have shown, the link between welfare policy and behavior is strongest for the women with the lowest levels of education and hence, the most limited opportunities in the labor market. Moreover, as shown in Figures 2–4, this group experienced much greater change in family structure between 1940 and 2000 than did the population as a whole.

The measure of welfare generosity used in most studies is the maximum monthly AFDC benefit level for a family of a given composition. This measure, however, is only available back to 1960. Although many states have legislated maximums, the effective maximum is set administratively. Before 1961, the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare collected data on these measures only sporadically (U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare 1963, p. 2). So I try two sets of measures. First, I use a measure that is available for all of the years: the average monthly ADC/AFDC payment per child.20This measure has also been used in the literature on the welfare effects of family structure and is highly correlated with the maximum benefit guarantee measures. Its drawback is that it reflects not only of the level of benefits paid by a state, but also the composition of families on the welfare rolls in that state and the nonpublic assistance income of those families. Sec-ond, I construct a measure of the maximum monthly benefit paid to families of four in 1940 to use in conjunction with the maximum monthly AFDC benefit level data available for 1960 and 1970.21In 1940, the Social Security Administration published data on the monthly payments made by each state to families of different composi-tions (Social Security Administration 1940). These data are presented as the percent-ages of families who received different payment levels (broken down into $5 increments). The distributions for some states contain extreme outliers, most likely reflecting supplemental payments for critical medical services. Therefore, as a mea-sure of the usual maximum benefit level, I use the 90th percentile of each stateÕs distribution of payments to families of four.22The SSA data only include benefits

19. The exception was births to single women in 1950.

20. The average monthly benefit per child was calculated using data on total ADC/AFDC expenditures and the number of children receiving benefits in the month of April in a given census year.

21. Robert Moffit has kindly made available on his website data on welfare benefits by state for the years 1960 to 1998.

paid in states with approved ADC plans in 1940. A number of states—Connecticut, Illinois, Iowa, Kentucky, Mississippi, Nevada, South Dakota, and Texas—did not have such plans. These states did pay grants to single mothers in 1940, but under state mothersÕ pensions programs rather than ADC.23 Instead of excluding those states from the analysis, I include a variable indicating that a womanÕs state of res-idence did not have a federally approved program in 1940. All welfare benefit amounts have been converted to year 2000 dollars.24

Between 1960 and 1970, public assistance benefits available to single mothers in-creased substantially with the creation of food stamps and Medicaid. Food stamps paid the same level of benefits to women in all states, but Medicaid programs dif-fered across states, contributing to the spatial variation in benefits. To capture differ-ences in Medicaid programs, Moffitt (1994) converts average Medicaid expenditures into a ‘‘cash value.’’ Unfortunately, data on average Medicaid expenditures are not available for years prior to 1975.25It also is unclear how well the constructed ‘‘cash value’’ relates to the value women placed on Medicaid benefits.

The estimated 1970 models do, however, incorporate another change in welfare programs that took place over the 1960s. In response to the dramatic rise single motherhood and the concern that this may be related to the targeting of single mothers in public welfare programs, states were allowed to establish AFDC-Unemployed Parent (AFDC-UP) programs that provided benefits to two-parent fam-ilies in which the primary breadwinner was unemployed. I therefore include an indicator variable for whether or not a state had such a program in place in 1970.

I estimate linear probability models with control variables similar to those used in the models presented above. Starting in 1940, the Census collected data on years of schooling. So I replace literacy with measures of schooling levels. For the full sam-ple, I include a set of variables indicating less than nine years of schooling, nine to eleven years of schooling, and some college. Twelve years of schooling is the ex-cluded category. For the low education sample, I enter years of schooling linearly. Due to changes in the data collected by the census, I also use a slightly different set of controls for the economic condition of the state: the ratio of females to males, real per capita personal income, the unemployment rate, and the percentages of stateÕs employed labor force in manufacturing, trade, services, and government. Descriptive statistics for these variables are provided in Appendix Table A2.26I correct the stan-dard errors for clustering by state due to the use of state-level variables in the models. Tables 4 and 5 present the results of the cross-sectional linear probability models. Only in the 1970 data do we find a positive correlation between welfare benefits and

23. The SSA did collect data on total payments and recipients in these states so that we do have data on the average payment per child in these states in 1940.

24. These conversions were made using the GDP deflator for personal consumption expenditures produced by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

25. Robert Moffitt has constructed Medicaid expenditure data for the years 1968 to 1974 using the 1975 data and scaling them back by the growth rate of national Medicaid expenditures. He, however, notes the potential unreliability of these data. Given the other issues regarding how to use such data to construct a cash value of Medicaid benefits, I decided not to use MoffittÕs constructed data for 1970.

Table 4

AFDC Benefits and White Family Structure: Linear Probability Models, 1940-1970

Variables 1940 1950 1960 1970

A. Single Motherhood All women

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 20.0010* 20.0003 20.0011* (0.0005) (0.0005) (0.0006) No federal program 20.0034

(0.0032)

AFDC-UP 26.E-5 (0.0024) R-squared 0.0082 0.0060 0.0103 Model II: AFDC expenditures/child ($100s) 20.0073** 20.0026 20.0006 20.0019 (0.0019) (0.0017) (0.0017) (0.0019) AFDC-UP 20.0008

(0.0023) R-squared 0.0083 0.0048 0.0060 0.0103 Number of observations 228,038 75,375 248,200 254,025 Bottom quartile of education distribution

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 20.0012 0.0008 0.0012 (0.0008) (0.0008) (0.0010) No federal program 1.5E-5

(0.0045)

AFDC-UP 0.0049 (0.0046) R-squared 0.0050 0.0023 0.0039

The

Journal

of

Human

AFDC-UP 0.0036 (0.0043)

R-squared 0.0052 0.0012 0.0023 0.0041

Number of observations 58,068 18,904 62,129 63,547

B. Divorce and Separation All women

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 20.0012 20.0011 20.0029**

(0.0010) (0.0008) (0.0008)

No federal program 20.0076

(0.0060)

AFDC-UP 20.0012

(0.0036)

R-squared 0.0055 0.0062 0.0080

Model II: AFDC expenditures/child ($100s) 20.0077* 20.0088** 20.0030 20.0080**

(0.0042) (0.0031) (0.0027) (0.0027)

AFDC-UP 20.0026

(0.0033)

R-squared 0.0056 0.0043 0.0062 0.0078

Number of observations 171,526 64,004 217,849 217,384

Bottom quartile of education distribution

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 0.0002 6.E-5 20.0006

(0.0012) (0.0010) (0.0010)

No federal program 20.0006

(0.0065)

AFDC-UP 0.0012

(0.0050)

R-squared 0.0060 0.0062 0.0060

(continued)

Moehling

Table 4(continued)

Variables 1940 1950 1960 1970

Model II: AFDC expenditures/child ($100s) 20.0060 20.0049 0.0018 0.0036 (0.0039) (0.0078) (0.0043) (0.0041) AFDC-UP 20.0005

(0.0050) R-squared 0.0061 0.0059 0.0062 0.0060 Number of observations 48,507 16,759 56,093 58,498 C. Births to Single Women

All women

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 20.0004 23.E-6 0.0002 (0.0002) (0.0009) (0.0004) No federal program 20.0019

(0.0014)

AFDC-UP 0.0009 (0.0016) R-squared 0.0041 0.0182 0.0187 Model II: AFDC expenditures/child ($100s) 20.0015 20.0009 0.0007 0.0008 (0.0008) (0.0025) (0.0035) (0.0017)

The

Journal

of

Human

R-squared 0.0041 0.0116 0.0182 0.0187 Number of observations 68,524 15,761 44,260 56,715 Bottom quartile of education distribution

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 20.0005 0.0015 0.0016 (0.0006) (0.0015) (0.0010) No federal program 20.0053

(0.0037)

AFDC-UP 0.0063 (0.0046) R-squared 0.0051 0.0238 0.0284 Model II: AFDC expenditures/child ($100s) 0.0025 20.0062 0.0047 0.0077*

(0.0020) (0.0073) (0.0066) (0.0044) AFDC-UP 0.0060

(0.0044) R-squared 0.0051 0.0183 0.0238 0.0285 Number of observations 12,816 3,453 10,586 11,947

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. For 1940 models, data were weighted to take into account sampling procedures used in construction of the data set. Standard errors have been corrected for clustering by state. *Significant at a 10 percent level; **Significant at a 5 percent level.

Moehling

Table 5

AFDC Benefits and Black Family Structure: Linear Probability Models, 1940-1970

Variables 1940 1950 1960 1970

A. Single Motherhood All women

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 20.0043** 20.0058** 20.0035 (0.0019) (0.0025) (0.0028) No federal program 20.0235**

(0.0083)

AFDC-UP 0.0312** (0.0135) R-squared 0.0045 0.0130 0.0285 Model II: AFDC expenditures/child ($100s) 20.0052 0.0012 20.0053 0.0010 (0.0113) (0.0197) (0.0114) (0.0091) AFDC-UP 0.0260**

(0.0125) R-squared 0.0042 0.0055 0.0127 0.0284 Number of observations 26,660 8,555 28,255 29,147 Bottom quartile of education distribution

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 20.0130** 20.0074** 20.0034 (0.0035) (0.0035) (0.0040) No federal program 20.0415**

(0.0150)

AFDC-UP 0.0404 (0.0254) R-squared 0.0064 0.0080 0.0209

The

Journal

of

Human

AFDC-UP 0.0420 (0.0252)

R-squared 0.0060 0.0046 0.0076 0.0209

Number of observations 6,795 2,178 7,162 7,375

B. Divorce and Separation All women

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 20.0030 20.0026 20.0034

(0.0046) (0.0032) (0.0035)

No federal program 0.0030

(0.0188)

AFDC-UP 0.0405**

(0.0165)

R-squared 0.0303 0.0099 0.0199

Model II: AFDC expenditures/child ($100s) 0.0276 0.0265 20.0025 0.0061

(0.0205) (0.0246) (0.0141) (0.0113)

AFDC-UP 0.0334**

(0.0162)

R-squared 0.0304 0.0240 0.0098 0.0198

Number of observations 19,805 7,090 22,679 22,363

Bottom quartile of education distribution

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 20.0149* 20.0076* 20.0051

(0.0076) (0.0040) (0.0050)

No federal program 0.0161

(0.0229)

AFDC-UP 0.0689**

(0.0337)

R-squared 0.0274 0.0160 0.0296

(continued)

Moehling

Table 5(continued)

Variables 1940 1950 1960 1970

Model II: AFDC expenditures/child ($100s) 20.0563 20.0170 20.0088 20.0166 (0.0356) (0.0557) (0.0181) (0.0212) AFDC-UP 0.0684**

(0.0337) R-squared 0.0255 0.0253 0.0156 0.0295 Number of observations 5,085 1,815 5,734 5,795 C. Births to Single Women

All women

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 20.0010 20.0018 21.E-4 (0.0008) (0.0031) (0.0017) No federal program 20.0020

(0.0054)

AFDC-UP 20.0094 (0.0089) R-squared 0.0049 0.0272 0.0317

The

Journal

of

Human

AFDC-UP 20.0072 (0.0090) R-squared 0.0050 0.0190 0.0272 0.0318 Number of observations 10,497 3,202 11,095 13,430 Bottom quartile of education distribution

Model I: AFDC maximum benefit ($100s) 0.0019 20.0044 0.0014 (0.0024) (0.0058) (0.0026) No federal program 0.0214**

(0.0079)

AFDC-UP 20.0187 (0.0140) R-squared 0.0089 0.0282 0.0380 Model II: AFDC expenditures/child ($100s) 20.0026 20.0223 0.0114 20.0074 (0.0101) (0.0303) (0.0260) (0.0087) AFDC-UP 20.0147

(0.0147) R-squared 0.0082 0.0303 0.0280 0.0380 Number of observations 2,527 778 2,836 3,556

Notes: Standard errors in parentheses. For 1940 models, data were weighted to take into account sampling procedures used in construction of the data set. Standard errors have been corrected for clustering by state. *Significant at a 10 percent level; **Significant at a 5 percent level.

Moehling

family structure, and then only for whites and only when using the average benefit per child measure. Consistent with studies of more recent data, this correlation also only appears for the low education group, here defined as the bottom quartile of the education distribution. The estimated coefficients imply that a $100 increase in the average monthly AFDC benefit per child led to a one percentage point increase in single motherhood and a 0.8 percentage point increase in the birthrate to single mothers. The implied elasticities calculated at the sample means are 0.23 and 0.37 respectively.

In contrast, Table 5 reveals that even by 1970, black single motherhood was not correlated with welfare benefit levels. Black family structure changed dramatically between 1940 and 1970, but the pace of change apparently did not vary with the level of welfare benefits in a given state. By 1970, the spatial variation in black family structure was unrelated to the spatial variation in welfare benefit levels. The history of welfare programs outlined above suggests a straightforward explanation for the contrasting findings by race: Up until 1970, blacks were relatively underserved by public assistance programs.

One interesting policy effect on black family structure does appear in the 1970 data, however. Black single motherhood was higher in states that offered benefits to two-parent families through the AFDC-UP program. While at first this may appear a perverse result, it most likely reflects the endogeneity of a stateÕs decision to create an AFDC-UP program. The states that created such programs were the states that already had the highest rates of black single motherhood.

The 1970 results for whites are not the only ones that reveal a statistically signif-icant relationship between family structure and benefits levels; they are simply the only ones that revealpositiveand statistically significant relationships between wel-fare benefits and family structure. Single motherhood for both blacks and whites in 1940 was negatively related to benefit levels. States that offered higher benefits had lower rates of single motherhood. Despite the evidence presented above that states that had more generous mothersÕ pensions laws experienced increases in divorce and separation and births to single women relative to less generous states, by 1940, the more generous states still had lower rates of single motherhood.

The data in Tables 4 and 5, therefore, serve as another blow to the social norm explanation of the correlation between welfare benefit levels and family structure. The fact that ADC benefit levels in 1940 were not positively related to the prevalence of single motherhood runs counter to the notion that welfare policy and behavior were simultaneously determined by social attitudes toward marriage and family. But these data also do not support the hypothesis that welfare induced changes in family structure. The bias in public assistance for single mothers has been present at least since the mothersÕpension laws enacted in the 1910s, yet we do not observe a cross-sectional relationship between benefit levels and family structure until 1970, and then only for whites. Blacks experienced the most dramatic changes in family structure over the period. By 1970, over 25 percent of black women aged 20 to 44 were single mothers. Yet, even in 1970, Table 5 shows no cross-sectional correlation between welfare benefits and black family structure.

appearance of this correlation indicates that this is not evidence of a direct ‘‘welfare effect.’’ But it may be evidence of welfare policy having an interactive effect with other forces that were leading to changes in family structure in the 1950s and 1960s. Given the strong correlation in benefit levels paid by states in 1940 and 1970 (0.77), the switching of sign of the benefit-level coefficient between these two census years suggests thatchangesin family structure were related to welfare generosity. To illustrate this more clearly, I estimate models which pool the data from Table 6

Pooled Models: Single Motherhood for Bottom Quartile of the Education Distribution

Age-squared 25.2E-5** 1.8E-5 24.9E-4** 6.1E-5

Years of schooling 20.0028** 0.0004 0.0028 0.0017

Foreign-born 20.0060 0.0070

Metropolitan area (identified) 0.0039 0.0024 0.0151** 0.0052 Metro status not identified 20.0183** 0.0056 0.0052 0.0272 State variables

Unemployment rate 20.0649 0.1251 20.3365 0.8861

Percentage employed in:

Manufacturing 20.0091 0.1197 20.2469 0.5577

Trade 20.0666 0.1490 22.6170** 0.7293

Services 0.6814** 0.1682 1.4886** 0.7125

Government 0.1077 0.4746 20.0186 1.3520

Real personal income per cap. ($100s)

20.0002 0.0002 20.0016* 0.0009 Sex ratio (females to males) 20.1928 0.2185 1.3300* 0.6800

Time trend 0.0127** 0.0062 0.1370** 0.0315

Constant 0.0922 0.1914 21.5809** 0.7548

State fixed effects Yes Yes

State time trends Yes Yes

R-squared 0.0078 0.0551

Number of observations 202,648 23,510

1940 to 1970 and allow both for state fixed effects and for state time trends as well as a general time trend. The estimated state time trends capture the changes in family structure that took place within states that cannot be explained by the common time trend or by changes in benefit levels or the control variables in the models.

Table 6 presents the estimated pooled models for the low education samples. The pooled data yield no positive correlation between benefit levels and single motherhood for blacks or whites. However, for whites, the estimated state time trends do reveal a positive association between the changes in single motherhood and welfare generos-ity. Figure 5 plots the estimated state time trends for whites against the average ADC benefits per child in 1940. The correlation of these data is 0.34. States that offered more generous welfare benefits in 1940 experienced more rapid growth in white single motherhood over the period.

This finding is consistent with the idea that welfare policy may have had an inter-active effect: Welfare policy did not induce the change in family structure, but more generous welfare policies may have facilitated more rapid change once the process began. It is instructive to note, however, that for blacks, even evidence of such an Figure 5

interactive effect is lacking. Figure 6 plots the estimated state time trends for blacks against the average ADC benefits per child in 1940. The correlation is20.13.

V. Conclusions

The history of welfare policy and family structure over the twentieth century provides little support for the argument that the positive cross-sectional correlation between single motherhood and welfare benefits is due to social norms that influence both policy and behavior. The relative welfare generosity of states has been quite persistent over the past century; the spatial variation in family struc-ture has not. But the historical perspective also brings into question the view that welfare policy was the driving force behind the dramatic changes in family structure that took place in the second half of the century. The bias in welfare policy toward single mothers long preceded the rise in single motherhood, and cross-state differ-ences in welfare generosity long preceded cross-state differdiffer-ences in behavior. More-over, the links between welfare policy and family structure are the weakest for Figure 6

blacks, the subgroup of the population that experienced the most dramatic increase in single motherhood. The rise in single motherhood that took place in the 1960s must be attributed primarily to other factors such as the worsening of the male labor market and hence the decline in the return to marriage (see Blau, Kahn, and Waldfogel 2000; Moffitt 2000).

That welfare policy played such a minimal role in changes in black family struc-ture before 1970 also follows from the history of welfare programs. Although wel-fare policy may not have been responsive to the needs of white or black families, at many junctures it was set so as to discriminate against blacks. The enactment of mothersÕpension laws in Southern states was negatively related to the prevalence of black single motherhood. Moreover, the exclusion of the ‘‘health and decency’’ clause in the Social Security Act that left the door open for the substantial variation across states in benefit levels was a concession to Southern lawmakers.

Like the studies that preceded it, this study raises additional questions. Most sig-nificantly, why do welfare policies vary so much across the states? A vast literature has tackled this issue, but much of it has focused on the period from 1968 forward.27 But as demonstrated in this paper, cross-state differences in welfare generosity ex-tend all the way back to the 1910s and the early state mothersÕpensions programs. Uncovering why these programs varied the way that they did may provide clues as to why differences in welfare generosity have been so persistent.

Appendix

Table A1Means of Variables for 1910-1920 Models, Women aged 20-44

1910 1920

Coverage of nonwidows 0.38 0.49 0.39 0.49 No legislated maximum benefit 0.23 0.42 0.22 0.42 Legislated maximum benefit (2000 $) 198.12 131.60 200.32 131.31 State funds 0.28 0.45 0.28 0.45 Workers’ compensation fatal benefit ratio 3.35 1.71 3.35 1.71

Age 30.67 7.09 31.02 7.01

Illiterate 0.05 0.21 0.04 0.20 Foreign-born 0.22 0.41 0.20 0.40 Metropolitan area 0.46 0.50 0.52 0.50 State sex ratio (females to males) 0.94 0.06 0.96 0.04 State fraction of labor force employed in:

Manufacturing 0.314 0.110 0.331 0.109 Trade 0.105 0.022 0.110 0.018 Services 0.149 0.024 0.136 0.020 Public services (n.e.c.) 0.013 0.004 0.019 0.007 Clerical 0.052 0.020 0.082 0.028 State personal income per capita (2000 $) 4,541 1,228 5,016 1,262 Number of observations 52,490 153,985 Blacks

Coverage of nonwidows 0.27 0.44 0.30 0.46 No legislated maximum benefit 0.07 0.26 0.08 0.27 Legislated maximum benefit (2000 $) 193.52 87.31 198.99 92.00 State funds 0.10 0.30 0.10 0.31 Workers’ compensation fatal benefit ratio 2.39 1.66 2.50 1.68

Age 29.83 6.80 30.45 6.91

Illiterate 0.19 0.39 0.12 0.32 Metropolitan area 0.37 0.48 0.49 0.50 State sex ratio (females to males) 0.99 0.06 0.98 0.07 State fraction of labor force employed in:

Table A2

Means of Variables for 1940-70 Models, Women aged 20-44

1940 1950 1960 1970

Variables Mean

Standard

Deviation Mean

Standard

Deviation Mean

Standard

Deviation Mean

Standard Deviation

A. Whites

Max. welfare benefit (2000 $) 481.06 284.94 794.46 254.68 867.41 284.22 Ave. benefit per child (2000 $) 146.09 63.27 189.88 69.03 211.13 67.83 238.59 79.36 No federal program 0.18 0.39

AFCD-UP 0.62 0.49 Age 31.22 7.15 31.62 7.05 32.36 7.12 31.10 7.45 Years of schooling 9.85 3.10 10.61 2.99 11.20 2.69 11.94 2.56 Years of school < 9 0.40 0.49 0.26 0.44 0.17 0.37 0.09 0.29 9–11 0.21 0.41 0.22 0.41 0.22 0.41 0.17 0.38 > 12 0.13 0.34 0.16 0.37 0.19 0.39 0.27 0.44 Foreign-born 0.09 0.28 0.05 0.22 0.05 0.22 0.06 0.23 Metropolitan area (identified) 0.58 0.49 0.60 0.49 0.60 0.49 0.64 0.48 Metro status not identified 0.15 0.36 0.13 0.33 State variables

Unemployment rate 0.10 0.03 0.05 0.01 0.05 0.01 0.04 0.01 Sex ratio (females/males) 0.99 0.03 1.01 0.03 1.03 0.02 1.05 0.02 Fraction employed in:

Manufacturing 0.24 0.10 0.26 0.10 0.27 0.08 0.26 0.07 Trade 0.17 0.03 0.19 0.02 0.18 0.01 0.20 0.01

The

Journal

of

Human

Personal income per capita (2000 $) 6,440 1,935 9,113 1,737 10,975 1,961 15,356 2,236 Number of observations 228,038 75,375 248,200 254,025 B. Blacks

Maximum welfare benefit (2000 $) 349.50 234.17 667.63 279.20 794.03 326.56 Average benefit per child (2000 $) 94.84 56.56 143.77 68.77 173.26 73.56 210.91 89.22 No federal program 0.21 0.41

AFCD-UP 0.53 0.50 Age 30.83 6.99 31.22 7.05 31.78 7.08 30.96 7.38 Years of schooling 6.73 3.39 7.97 3.52 9.45 3.30 10.85 2.81 Years of school < 9 0.75 0.43 0.59 0.49 0.38 0.48 0.18 0.38 9–11 0.14 0.34 0.21 0.41 0.29 0.45 0.30 0.46 > 12 0.04 0.20 0.07 0.25 0.10 0.30 0.16 0.36 Metropolitan area (identified) 0.48 0.50 0.59 0.49 0.66 0.47 0.73 0.44 Metro status not identified 0.11 0.31 0.08 0.28 State variables

Unemployment rate 0.08 0.03 0.04 0.01 0.05 0.01 0.04 0.01 Sex ratio (females/males) 1.05 0.05 1.06 0.05 1.07 0.04 1.10 0.04 Fraction employed in:

Manufacturing 0.20 0.08 0.24 0.09 0.27 0.08 0.27 0.07 Trade 0.14 0.04 0.18 0.03 0.18 0.02 0.20 0.02 Services 0.19 0.03 0.18 0.02 0.21 0.02 0.26 0.02 Government 0.03 0.01 0.04 0.02 0.05 0.02 0.05 0.02 Personal income per capita (2000 $) 4,758 2,010 7,903 2,105 10,102 2,332 14,927 2,604 Number of observations 26,660 8,555 28,255 29,147

Notes: Data for 1940 were weighted to take into account sampling procedures and make them representative of the population.

Moehling