Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 20:49

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Learning Goals of AACSB-Accredited

Undergraduate Business Programs: Predictors of

Conformity Versus Differentiation

Kyle E. Brink, Timothy B. Palmer & Robert D. Costigan

To cite this article: Kyle E. Brink, Timothy B. Palmer & Robert D. Costigan (2014) Learning Goals of AACSB-Accredited Undergraduate Business Programs: Predictors of Conformity Versus Differentiation, Journal of Education for Business, 89:8, 425-432, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.929560

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2014.929560

Published online: 04 Nov 2014.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 62

View related articles

Learning Goals of AACSB-Accredited

Undergraduate Business Programs: Predictors

of Conformity Versus Differentiation

Kyle E. Brink and Timothy B. Palmer

Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo, Michigan, USA

Robert D. Costigan

St. John Fisher College, Rochester, New York, USA

Learning goals are central to assurance of learning. Yet little is known about what goals are used by business programs or how they are established. On the one hand, business schools are encouraged to develop their own unique learning goals. However, business schools also face pressures that would encourage conformity by adopting goals used by others. The authors examined the extent to which learning goals of business programs are unique versus similar. Their evidence suggests business schools adopt goals that are quite similar. Public schools and lower ranked schools were more likely to demonstrate such conformity. The implications of goal similarity are discussed for management education and assurance of learning.

Keywords: AACSB, assurance of learning, business accreditation, business education, learning goals

All organizations, including business schools, must contend with the tension between differentiation and conformity in their business strategy. Business schools have debated dif-ferentiation and conformity for roughly 100 years (McKenna, Yeider, Cotton, & Van Auken, 1991). The Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International (AACSB), as the largest accreditor of business schools, wrestles with this same tension. When Joseph A. DiAngelo was the chair-elect of the committee reviewing AACSB’s accreditation standards, he said that “when the rules are too prescriptive, schools’ mission statements, which drive their curricula and hiring patterns, all start to look the same. ‘It’s all vanilla. I want to see the nuts and the cherries and all the things that make your school unique’” (Mangan, 2012, para. 6–7).

We examine the differentiation versus conformity ten-sion in the context of the learning goals of AACSB-accred-ited business schools. Though some scholars have

conducted research related to the AACSB’s strategic man-agement standards (e.g., Hammond & Webster, 2011; Julian & Ofori-Dankwa, 2006; Orwig & Finney, 2007; Palmer & Short, 2008), “studies that are attentive to the impacts upon curriculum design and learning from accredi-tation institutions are atypical” (Lowrie & Willmott, 2009, p. 412). The lack of research related to assurance of learn-ing is unfortunate given that the development of student learning goals is one of the key principles for meaningful educational accountability (Association of American Col-leges and Universities and the Council for Higher Educa-tion AccreditaEduca-tion, 2008).

We chose to focus on learning goals because they form the basis for the curriculum (Rubin & Martell, 2009). The learning goals explicate a business school’s mission and curricular priorities and serve as the link between a school’s mission and assessment. The 2003 Standards (AACSB, 2012) say that learning goals are “a key element in how the school defines itself” (p. 61) and that:

This list of learning goals derives from, or is consonant with, the school’s mission. The mission and objectives set out the intentions of the school, and the learning goals say

Correspondence should be addressed to Kyle E. Brink, Western Michi-gan University, Haworth College of Business, Department of Management, 1903 W. Michigan Avenue, Kalamazoo, MI 49008–5429, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2014.929560

how the degree programs demonstrate the mission. That is, the learning goals describe the desired educational accom-plishments of the degree programs. The learning goals translate the more general statement of the mission into the educational accomplishments of graduates. (p. 60)

When Milton Blood was the managing director of the AACSB, he highlighted the importance of learning goals, saying that they are,

. . .a way of focusing on the competencies you want

stu-dents to have as graduates of the program, and [give] the schools a way to say to both prospective students and to potential employers of graduates of that program, “Here are the knowledge and skills that will be instilled in the gradu-ates of that program.” (Thompson, 2004, p. 437)

In sum, the purpose of our research is to examine the undergraduate learning goals that AACSB-accredited busi-ness programs use for assurance of learning. We identify the extent of variation that exists between business pro-grams with respect to their learning goals as they face com-peting pressure to uniquely position themselves in the market, while at the same time succumbing to conformity brought about from a host of environmental pressures. We also explore program characteristics that predict which types of business schools are most likely to differentiate versus conform through their array of learning goals.

DIFFERENTIATION VERSUS CONFORMITY

The tension for business schools to be distinct, but not excessively so, is not new. McKenna et al. (1991) described how the pendulum began swinging from differentiation in 1959 as a result of the separately commissioned reports by Gordon and Howell and by Pierson. Prior to the 1950s, diversity in business programs was commonplace. Gordon and Howell and Pierson criticized business schools for the lack of standardization with respect to faculty preparation, curricula, and teaching pedagogy (Cotton, McKenna, Van Auken, & Yeider, 1993). Business schools adapted to these criticisms, perhaps too effectively, and “by the 1980s the curricula of most schools of business appeared predictably similar, as if cut from the same cloth” (Cook, 1993, p. 28).

The pendulum, however, would swing in the opposite direction after the AACSB commissioned Lyman Porter and Lawrence McKibbin to undertake a comprehensive review of U.S. business education (Porter & McKibbin, 1988). Their efforts resulted in a significant change in the AACSB’s accreditation standards. In particular, the Porter and McKibbin report argued the AACSB should permit business schools to capitalize upon their unique strengths by crafting uniqueness into their assurance of learning plans, including learning goals.

The tension between differentiation and conformity wit-nessed by business schools is one felt by many types of organizations and can be explained through the lenses of competing views about organizations and their strategies. We examine those perspectives, in the context of assurance of learning standards adopted by business schools, in the following sections.

Assurance of Learning Standards: Differentiation

A common perspective in business is that firms should develop distinctive competencies resulting in asymmetry, or uniqueness, from their rivals. The strategic view would suggest that schools differentiate themselves through learn-ing goals that target particular markets in an attempt to secure resources. In line with the strategic perspective, the 2003 standards (AACSB, 2012) indicate that learning goals should differ across schools. Milton Blood stated that along with the change to direct assessment standards, “we will see very clear differences between schools on how they will define their learning goals. . . . We will start seeing

schools differentiating themselves more and more as they

. . .define learning goals for degree programs” (Thompson,

2004, p. 436).

Guidance provided by the AACSB standards suggests schools derive goals that meet their unique situations. In particular, they state, “because of differences in mission, faculty expectations, student body composition, and other factors, schools vary greatly in how they express their learning goals” (AACSB, 2012, p. 61). Schools are encour-aged to canvass the perspectives of a wide variety of stake-holders, such as alumni, students, and employers, for input about learning goals. One avenue they recommend is to seek direction from advisory boards whose members repre-sent unique stakeholder perspectives (AACSB, 2007).

AACSB is perhaps more emphatic in suggesting differ-entiation in learning goals with regard to addressing student needs. This is because, “goals assist potential students to choose programs that fit their personal career goals. Only with an accurate understanding of the learning goals can a potential student be able to make an informed choice about whether to join the program” (AACSB, 2012, p. 60). In sup-port, Romero (2008) concluded that the AACSB’s stand-ards promote innovation and creativity regarding curriculum and course development, and Glenn (2011) argued for the presence of thousands of learning goals that have been defined across all AACSB-accredited schools.

Assurance of Learning Standards: Conformity

The strategic view promoting differentiation on the basis of learning goals is appealing. However, business schools face considerable pressures that may temper differentiation and promote conformity instead. Theories about organization and economics hold that organizations perform best when

426 K. E. BRINK ET AL.

they fit with the demands of their external environment. This requires administrators to ensure their organizations are attuned to key success factors that are a function of the environment’s demands (Amit & Schoemaker, 1993). More broadly, it is argued that organizations are influenced by “rules of appropriateness” (March & Olsen, 1984, p. 741) resulting in actions that are brought into harmony with environmental conditions (F. M. Scherer & Ross, 1990). Conforming behaviors arise through socialization, educa-tion, as well as “acquiescence to convention” (DiMaggio & Powell, 1991, p. 11). Further, organizations accrue benefits by positioning themselves similar to others who are respected (Elsbach & Sutton, 1992). In the context of busi-ness program assurance of learning, these pressures would result in the selection of learning goals that are similar to those adopted by other schools.

Given our focus on learning goals, we pay particular attention to pressures engendered by assessment and accreditation standards at both the institution and business program levels. At the institutional level, norms in higher education assessment provide one example of a key envi-ronmental constraint. Business schools face pressure to align their goals with commonplace core knowledge goals found at their respective institutions and in higher educa-tion. For example, the Higher Learning Commission, which is the accrediting body for the North Central region of the United States includes in its criteria for accreditation that all university programs engage students in collecting, ana-lyzing, and communicating information and that all pro-grams recognize human and cultural diversity (Higher Learning Commission, 2013). A requirement of a uni-versity’s accreditation, therefore, is the pressure for pro-grams, whether business or arts and sciences, to have learning goals conform to goals that unite the university. It is likely that the learning goals of all business programs would include those that address some of the general knowledge and skills.

Business schools also face pressure from their own accrediting bodies. For example, prior to 2003 the AACSB standards prescribed curricular content areas, whereas the 2003 and 2013 AACSB standards no longer do so. It is plausible that business schools’ learning goals are a vestige of the pre–mission-linked standards that emphasized a prescribed body of knowledge for undergraduate and master’s programs. It was commonly felt that business education should stand on the should-ers of core standards that are shared across business schools. Indeed, a common body of knowledge was the most frequently cited advantage of accreditation by deans and the second most frequent by professors (Hen-derson, Jordon, & Crockett, 1990). Goals may evidence congruence because they have historically been per-ceived to be the right goals that are most appropriate for business school students. In support, Navarro (2008) found little differentiation in core master of business

administration courses and a standard design in core curricula in the 50 top-ranked business schools.

In a similar vein, though the 2003 and 2013 AACSB standards no longer prescribe curricular content, pressure to conform would be heightened through specific language found in these standards. For example, the standards pro-vide several examples of general and management-specific learning goals (e.g., leadership, problem solving), and the AACSB stated that “curricula without [globalization and information systems] would not normally be considered current and relevant” (AACSB, 2012, p. 70). Statements such as these can have the same effect as prescription. As Kilpatrick, Dean, and Kilpatrick (2008) cautioned, “although AACSB does not advocate for a specific approach to meeting standards and itself does not recom-mend standardization, interpreting and complying with new standards may easily be seen as a movement toward just that” (p. 201).

Predictors of Differentiation Versus Conformity in Business Program Learning Goals

Though the tension between differentiation and conformity exists, it is not a dichotomous either–or proposition. Rather, it is a continuum. When business programs establish their learning goals, they make a choice regarding the extent to which they want to differentiate themselves or conform to the influence of environmental pressures. Some programs may exclusively adopt goals that are commonly used by other schools or mirror the topics recommended by the AACSB standards. Some may attempt to develop entirely unique goals. Finally, others may evidence a mix of con-forming and differentiating goals.

We believe there are predictable differences regarding the extent to which business programs differentiate them-selves or conform through their learning goals. For exam-ple, McKenna et al. (1991) suggested that forces for differentiation include market niche, characteristics of the student population, preferences of endowment donors, regional job markets for graduates, and the local economy. Many of these forces are characteristics of the external environment and are not institutional or business program factors, per se. However, institutional control (i.e., public versus private ownership) is an institution-level factor that is related to many of these external forces and, as such, may be related to learning-goal conformity. The philosophy of the institution mission statement may influence the busi-ness program mission (Palmer & Short, 2008) and, in turn, assurance of learning goals.

We expect that public schools are more likely to have conforming learning goals than private schools. Deans of public business schools must satisfy not only the needs of university administrators, faculty, students, and alumni, but also state boards and elected officials. This additional level of oversight is more likely to constrict the range of goals

considered than it is to engender creativity and uniqueness. In contrast, private business schools may have missions that are influenced by the values of nongovernment stake-holder. In addition, private colleges often cater to a smaller niche and, because they are more tuition driven than their public counterparts, they may need to be more adaptive to these niches and more innovative with their learning goals. Private institutions may also receive funding from a wider variety of stakeholder types. Further, some private schools may have a stronger liberal arts focus, others may focus more on social justice and service learning, while others may have a religious affiliation. To the extent that learning goals reflect the greater diversity of missions and stakehold-ers found in private schools, we would expect that private schools also have more differentiated learning goals. This is because they face fewer pressures to conform to learning goals of other business schools and greater pressures to position themselves uniquely in their markets. Thus, the first hypothesis is as follows:

Hypothesis 1(H1):Learning goals of public undergraduate business programs would be more likely to conform than learning goals of private undergraduate business programs.

On the other side of the tension, McKenna et al. (1991) suggest that forces for conformity include accreditation standards, a fixed set of refereed journals, a national faculty and administrator job market, and national rankings of pro-grams. Given that these are forces for conformity, there would be little variability across business programs with respect to most of these factors. However, program rank-ings would have sufficient variability to determine its influ-ence on learning-goal conformity.

It is plausible that the reputation of the undergraduate business program will influence the extent to which the business school conforms or differentiates through its learn-ing goals. AACSB accreditation is regarded by some as the more prestigious of the business school accreditors (Roller, Andrews, & Bovee, 2003). For schools hoping to improve the reputation of their undergraduate business programs, AACSB accreditation may be the only distinguishing factor separating them from similar business programs. In con-trast, more reputable programs have a variety of ways to distinguish themselves including key alliances with world-wide firms and unique centers offering executive education. As a result, AACSB accreditation might be regarded as more valuable or essential to schools aspiring to enhance their reputations, and hewing closely to perceived AACSB norms may be deemed essential to these schools. As such we believe less reputable programs will be more likely to succumb to external environmental pressures and may adopt goal topics that closely imitate their AACSB-accred-ited peers or conform more closely to the AACSB stand-ards. Thus, the second hypothesis is:

H2: Learning goals of less reputable business programs would be more likely to conform than learning goals of more reputable undergraduate business programs.

METHOD

Sample

We searched for learning goals on the websites of U.S. undergraduate business programs that appeared on AACSB’s accreditation list. If the website did not have the learning goals posted, we emailed the business school’s dean to request the program’s learning goals. Searches of schools’ websites yielded 116 sets of learning goals. We received email correspondence from deans or representa-tives of the dean, yielding another 91 sets of learning goals. In total, we obtained the learning goals of 207 of the 465 AACSB-accredited U.S. undergraduate business programs, which translates into a participation rate of 45%.

Coding Business Program Learning Goals

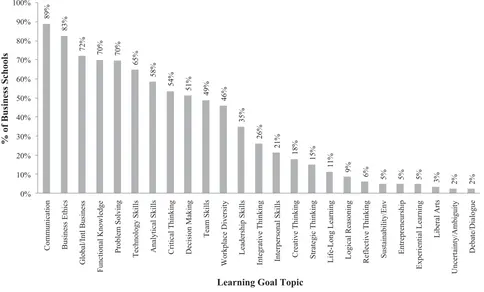

Two independent reviewers (one was the study’s third author and the other was a trained research assistant) inde-pendently coded all business programs’ learning goals. We used Miles and Huberman’s (1994) inductive approach to code learning goals. No precoding of the learning goals was conducted. After all of the goals were collected, the coding process began. Learning-goal themes were identi-fied inductively through an iterative process. More specifi-cally, we reviewed the learning-goal topics or concepts (i.e., knowledge areas, skills, abilities, and other competen-cies) appearing in a representative subset of our sample and developed an initial list of topic areas. We then began cod-ing the learncod-ing goals of each school in the entire sample into our initial topic areas; and in line with Miles and Huberman, we revised our learning-goal categories by add-ing new topic areas as needed. We ultimately identified 25 learning-goal topics (see Figure 1).

We recognize that some of the goal topics are related to one another conceptually (e.g., decision making, problem solving, and analytical skills; integrative thinking and strate-gic thinking; communication and debate or dialogue). Indeed, it would be possible to classify all of the goals into higher order constructs such as conceptual, interpersonal, and technical competencies (cf. Dierdorff, Rubin, & Morge-son, 2009). Nevertheless, each business program made a conscious choice regarding the wording of its final goals. That is, despite the interrelationships among constructs, some programs chose to emphasize interpersonal skills whereas more programs chose to emphasize team skills. A few schools chose to emphasize debate whereas most schools emphasized communication. These intentional word choices may serve as the means for differentiation or

428 K. E. BRINK ET AL.

conformity in learning goals. Even if the words were not carefully chosen with the intent to conform or differentiate, they may still signal conformity/differentiation to stakehold-ers. Therefore, we chose to remain true to the wording used by the business programs rather than attempting to interpret what they may have meant and speculating whether some topics should have been combined with other similar topics.

For all learning goals, a coding of 1 was assigned to a learning-goal topic if the goal was present in the program’s set of learning goals; a coding of 0 was assigned to a learn-ing-goal topic if the goal was not present. Any discrepancy between the two raters was resolved with the independent judgment of a third trained rater. Inter-coder agreement was determined based on the independent ratings of the first two raters using percent agreement and Cohen’s kappa. The overall percent agreement across all learning-goal topics was .88, which is sufficient according to qualitative research standards (Miles & Huberman, 1994). Cohen’s kappa across all learning-goal topics was .73 (p < .001) demonstrating sufficient intercoder agreement (Lombard, Snyder-Duch, & Bracken, 2002; Sun, 2011).

Differentiation and Conformity Variable

In order to test our hypotheses, we needed to establish an index of differentiation and conformity. We first classified

each of the 25 learning goal topics as conforming or differ-entiating goals based on whether they were used more or less frequently than what would be expected by chance (or on average). Our sample included a total of 1,800 goals across 207 business programs and 25 goal topics, which results in an average of .35 goals per school per topic. Therefore, we used the frequency value of 35% as the threshold for defining conforming versus differentiating learning goals. All 11 goal topics with a frequency of 46% or more (see the left-most goal topics in Figure 1) occurred more frequently than would be expected by chance. These conforming learning goals represent areas of conformity among business schools. All 13 goal topics with a fre-quency of 26% or less (see the right-most goal topics in Figure 1) occurred less frequently than would be expected by chance. These differentiating learning goals represent areas of differentiation among business schools. For the leadership goal, the observed frequency (35%) was equal to the expected probability (.35). Therefore, we excluded it from subsequent analyses. Binomial tests confirmed that the observed probabilities of all conforming and differenti-ating learning goals departed significantly (p <.001) from

the expected probability of .35, whereas the observed prob-ability of the leadership learning goal did not.

Next, we established a business program conformity variable as the proportion of a business program’s

89%

83%

72% 70%

70%

65%

58%

54%

51%

49%

46%

35%

26%

21%

18%

15%

11%

9% 6%

5% 5% 5% 3%

2% 2% 0%

10% 20% 30% 40% 50% 60% 70% 80% 90% 100%

Communication Business Ethics

Global/Intl Business

Functional Knowledge

Problem Solving Technology Skills Analytical Skills Critical Thinking Decision Making

Team Skills

Workplace Diversity

Leadership Skills

Integrative Thinking Interpersonal Skills

Creative Thinking Strategic Thinking Life-Long Learning Logical Reasoning Reflective Thinking Sustainability/Env Entrepreneurship

Experiential Learning

Liberal Arts

Uncertainty/Ambiguity

Debate/Dialogue

% of Business Schools

Learning Goal Topic

FIGURE 1. Percentage of business schools using each learning-goal topic (ND207). Communication included goals related to communication, written

communication, or oral communication. Functional knowledge refers to knowledge related to business functions. Integrative thinking included goals related to multidisciplinary, cross-functional, or systems thinking. Creative thinking included innovation or innovative thinking. Experiential learning included goals related to service learning, internships, or cooperative education.

learning goals that were determined to be conforming learning goals. Therefore, the business program confor-mity variable could range from 0 (no conforming goals) to 1 (only conforming goals). The business program confor-mity variable was negatively skewed (MD.82,SDD.13, skewness D –.52); the skewness was statistically

signifi-cant (p <.01). Twenty-two percent of the business

pro-gram sample had perfect conformity (i.e., conformity valuesD1.0) and 1% had conformity values less than .5.

Generally, the descriptive statistics and frequencies sug-gest that business schools are relatively homogenous in their learning goals, indicating that they are more likely to conform than differentiate.

Business Program Characteristics

We gathered data related to institutional control and busi-ness program reputation. Institutional control was measured as public (coded as 0;nD156) versus private (coded as 1;

nD51) with data obtained from the AACSB website. For reputation, we used the 2010 Bloomberg BusinessWeek’s rankings of top undergraduate business schools. The Busi-nessWeek rankings were the first ranking system and are considered the most influential ranking list (Corley & Gioia, 2000; Morgeson & Nahrgang, 2008). We coded each school as unranked (coded as 0;nD161) or ranked (coded as 1;nD46), and we recorded the numeric ranking for the ranked schools.

RESULTS

We analyzed the relationship between institutional control and business program conformity using an independent sam-ples t-test. The result is statistically significant, t(205) D

3.64,p <.001,d D0.59. Public schools (MD.84,SDD

.13) were more likely to conform than private schools (M

D.77, SD D .13), supporting H1. We then analyzed the

relationship between undergraduate business program ranking and business program conformity using an inde-pendent samplesttest. The result was not statistically sig-nificant, t(205) D–0.20,p D.84,d D–0.03), indicating

that ranked (M D.83,SDD.13) and unranked (M D.82,

SD D.13) business programs were equally likely to

con-form in their learning goals.

To drill deeper into the data, we analyzed the relation-ship between undergraduate business program ranking and business program conformity on the subset of 46 ranked programs. The correlation between rank and conformity was statistically significant (r D.37, p D.01), indicating that lower ranked schools (i.e., schools with a larger numeric ranking value) were more likely to conform in their learning goals. Therefore, whileH2was not supported when comparing ranked versus unranked undergraduate business programs, we find supporting evidence when using

the subset of ranked schools and treating rank as a continu-ous variable.

DISCUSSION

We found variation among business programs with respect to their mix of conforming and differentiating goals. Public schools were more likely to conform in their choice of learning goals than private schools, and lower ranked undergraduate business programs tended to conform more than higher ranked programs. However, we did not find a difference between ranked and unranked schools.

Though we found variation among business programs with respect to their mix of conforming and differentiating goals, overall the schools were rather homogenous. In fact, 22% of the programs in our sample utilized only conform-ing goals. The programs that did differentiate themselves did so to a small extent. Therefore, it appears that the conformity pole of the tension is stronger than the differen-tiation pole. Despite the AACSB’s desire for differentia-tion, it is possible that business schools fear that loosing accreditation is more likely to result from the failure to con-form rather than the failure to differentiate.

Implications for Practice

Results of our study would suggest that an area for schools to focus on is thecontentof their learning goals and objec-tives. This would include asking critical questions about a specific program’s optimal mix of goals and objectives such as the following: Why do we have the mix that we do? How can we best align our learning goals to our mission and target markets? Part of this conversation should be focused on purposeful conformity: identifying goals that are relevant to all business students graduating from all business schools. The other component is selecting goals that are unique to programs that are designed to most effec-tively meet the needs of target markets.

Regarding the high level of conformity detected among schools’ goals in our study, we believe it is important for faculty to think about why there is so much commonality among goals and if the goals evidencing high conformity represent skill sets our students are most in need of. Our worry is that common goals such as communication or ethics, while appealing and important, may be used on a shared belief that legitimate business schools adopt them in their assessment plans. However, merely conforming gives short shrift to the underlying potential these goals might provide our students.

Our results also identified goals that are not commonly found in business school assessment plans. Sustainability is a key priority among business (Nidumolu, Prahalad, & Rangaswami, 2009), yet only 5% of the schools in our study identified it as a learning goal. Likewise, many believe that

430 K. E. BRINK ET AL.

today’s hypercompetitive business environments demand innovative thinking (Hamel, 2007), yet this is not a com-monly employed learning goal. While some (18%) have adopted creative thinking and 5% have entrepreneurship, learning goals encouraging innovative thinking are uncom-mon. Our belief is not that all schools need to adopt sustain-ability or innovation (for example) as learning goals. However, we worry that the apparent pressures for confor-mity, whether real or presumed, may be resulting in busi-ness educators adopting learning goals that are not preparing students as well as we can be.

Implications for Future Research

Though our research sheds light on the extent to which business schools conform in their learning goals, we do not yet know what they are conforming to. For example, a busi-ness school may be conforming to the goals of their peer and aspirant schools, to the learning goal and curricula topics put forth in the AACSB standards, or to evidence-based competencies established in empirical research. Any of these sources of conformity could result in homogeneous learning goals across business programs. Additional research is needed to determine the source to which pro-grams are conforming and the extent to which areas of con-formity are relevant to business program stakeholders.

Similarly, though business schools demonstrate more conformity than differentiation in their learning goals, we do not know whether conformity is necessarily a negative outcome. Given that varying degrees of conformity and dif-ferentiation are natural for organizations in all industries, perhaps it should come as no surprise that conformity is present in the business school industry. Apparently there was too much sameness among business schools in the 1970s to 1980s (prior to the Porter & McKibbin [1988] report). Future research should identify how much differen-tiation is desired or needed. Is having one unique learning goal enough, or should programs have several unique goals? At what point does a business program go from being differentiated to one whose legitimacy is suspect? If a business program’s mission is to conform and be similar to other schools, is there value in this to that particular school and what factors might it depend on? Though we did find a correlation between conformity and undergraduate business program ranking, we believe the correlation is more likely a result of better schools being more willing to develop differentiating learning goals and less likely a result of differentiating learning goals causing schools to achieve a higher ranking.

Limitations

Some caution is necessary when interpreting our findings because our sample comprised 45% of U.S. AACSB-accredited undergraduate business programs. Whether our

results generalize to the learning goals of the other 55% of accredited undergraduate programs or graduate, interna-tional, or non–AACSB-accredited programs not in our sam-ple is uncertain.

Though AACSB-accredited schools do not appear to be strongly differentiated from one another, there is some evi-dence that AACSB-accredited programs are differentiated from non–AACSB-accredited programs. For example, R. F. Scherer, Javalgi, Bryant, and Tukel (2005, p. 654) stated that a primary reason business schools seek AACSB accreditation is to “enhance their reputation/image by dif-ferentiating themselves from non-accredited schools.” Sim-ilarly, Jantzen (2000) found small differences with respect to student, faculty and program characteristics between schools that were candidates for AACSB accreditation and those that were recently accredited. However, he found sub-stantial differences between candidate schools and those not pursuing AACSB accreditation, further suggesting that there may be larger differences between accredited versus nonaccredited schools and smaller differences within the sample of AACSB-accredited schools.

CONCLUSION

The AACSB encourages differentiation in mission state-ments as well as in the mission-linked learning goals. How-ever, it appears that Milton Blood’s prophecy of very different learning goals across AACSB-accredited schools has not yet been fulfilled, and Joseph DiAngelo may have a difficult time finding the nuts and cherries. Though the ten-sion between differentiation and conformity is real, in the context of the undergraduate learning goals of AACSB-accredited business programs it appears that the pressure to conform is stronger than the pressure to differentiate. Public schools and lower ranked business programs, in particular, are more likely to adopt conforming learning goals. Addi-tional research is needed to determine what business pro-grams are conforming to and to determine the extent to which learning goal conformity versus differentiation is beneficial to all stakeholders.

REFERENCES

Amit, R., & Schoemaker, P. J. H. (1993). Strategic assets and organiza-tional rent.Strategic Management Journal,14, 33–46.

Association of American Colleges and Universities, & Council for Higher Education Accreditation. (2008).New leadership for student learning and accountability: A statement of principles, commitments to action. Retrieved from http://www.chea.org/pdf/(2008).01.30_New_Leadership_Statement. pdf

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International (AACSB). (2007).AACSB assurance of learning standards: An

inter-pretation. AACSB White Paper No. 3. Retrieved from http://www.

aacsb.edu/en/publications/whitepapers/

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International (AACSB). (2012).Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards

for business accreditation. Retrieved from http://www.AACSB.edu/

accreditation/standards-busn-jan(2012).pdf

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business International (AACSB). (2013).Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards

for business accreditation. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/

accreditation/business/standards/2013/2013-business-standards.pdf

Bloomberg BusinessWeek. (2010). Best undergraduate B-schools ranking

history. Retrieved from http://www.businessweek.com/articles/2013-03-20/best-undergraduate-b-schools-ranking-history

Cook, C. W. (1993). Curriculum change: Bold thrusts or timid extensions.

Journal of Organizational Change Management,6, 28–40.

Corley, K., & Gioia, D. (2000). The rankings game: Managing business school reputation.Corporate Reputation Review,4, 319–333.

Cotton, C. C, McKenna, J. F., Van Auken, S., & Yeider, R. A. (1993). Mis-sion orientations and dean’s perceptions: Implications for the new AACSB accreditation standards. Journal of Organizational Change

Management,6, 17–27.

Dierdorff, E. C., Rubin, R. S., & Morgeson, F. P. (2009). The milieu of management: Exploring the context of managerial work role require-ments.Journal of Applied Psychology,94, 972–988.

DiMaggio, P. J., & Powell, W. W. (1991). Introduction. In W. W. Powell & P. J. DiMaggio (Eds.),The new institutionalism in

organi-zational analysis (pp. 1–38). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago

Press.

Elsbach, K. D., & Sutton, R. I. (1992). Acquiring organizational legiti-macy through illegitimate actions: A marriage of institutional and impression management theories.Academy of Management Journal,

35, 699–738.

Hamel, G. (2007).The future of management. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Business School Press.

Hammond, K. L., & Webster, R. L. (2011). Market focus in AACSB mem-ber schools: An empirical examination of market orientation balance and business school performance.Academy of Marketing Studies Jour-nal,15, 11–22.

Henderson, J., Jordon, C. E., & Crockett, J. R. (1990). AACSB accredita-tion: Perceptions of deans and accounting professors.Journal of Educa-tion for Business,66, 9–12.

Higher Learning Commission. (2013).Policy title: Criteria for accredita-tion. Retrieved from http://policy.ncahlc.org/Policies/criteria-for-accreditation.html

Jantzen, R. H. (2000). AACSB mission-linked standards: Effects on the accreditation process.Journal of Education for Business,75, 343–347. Julian, S. D., & Ofori-Dankwa, J. C. (2006). Is accreditation good for the

strategic decision making of traditional business schools?Academy of

Management Learning and Education,5, 225–233.

Kilpatrick, J., Dean, K. L., & Kilpatrick, P. (2008). Philosophical concerns about interpreting AACSB assurance of learning standards.Journal of

Management Inquiry,17, 200–212.

Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., & Bracken, C. C. (2002). Content analysis in mass communication: Assessment and reporting of intercoder

reliabil-ity.Human Communication Research,28, 587–604.

Lowrie, A., & Willmott, H. (2009). Accreditation sickness in the consump-tion of business educaconsump-tion: The vacuum in AACSB standard setting.

Management Learning,40, 411–420.

Mangan, K. (2012, February 9). New business-school accreditation is likely to be more flexible, less prescriptive.The Chronicle of Higher

Education.Retrieved from

https://chronicle.com/article/New-Business-School/130718/

March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1984). The new institutionalism: Organiza-tional factors in political life.The American Political Science Review,

78, 734–749.

McKenna, J. F., Yeider, R. A., Cotton, C. C., & Van Auken, S. (1991). Business education and regional variation: An administrative perspec-tive.Journal of Education for Business,67, 50–55.

Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. 1994.Qualitative data analysis: An

expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Morgeson, F. P., & Nahrgang, J. D. (2008). Same as it ever was: Recogniz-ing stability in the BusinessWeekranking.Academy of Management Learning & Education,7, 26–41.

Navarro, P. (2008). The MBA core curricula of top-ranked U. S. business schools: A study in failure?Academy of Management Learning and Edu-cation,7, 108–123.

Nidumolu, R., Prahalad, C. K., & Rangaswami, M. R. (2009). Why sus-tainability is now the key driver of innovation. Harvard Business Review,87, 56–64.

Orwig, B., & Finney, R. Z. (2007). Analysis of the mission statements of AACSB-accredited schools.Competitiveness Review,17, 261–273. Palmer, T. B., & Short, J. C. (2008). Mission statements in U.S. colleges of

business: An empirical examination of their content with linkages to configurations and performance.Academy of Management Learning &

Education,7, 454–470.

Porter, L. W., & McKibbin, L. E. (1988).Management education and

development: Drift or thrust into the 21st century.New York, NY:

McGraw-Hill.

Roller, R. H., Andrews, B. K., & Bovee, S. L. (2003). Specialized accredi-tation of business schools: A comparison of alternative costs, benefits, and motivations.Journal of Education for Business,78, 197–204. Romero, E. J. (2008). AACSB accreditation: Addressing faculty concerns.

Academy of Management Learning and Education,7, 245–255.

Rubin, R. S., & Martell, K. (2009). Assessment and accreditation in busi-ness schools. In S. J. Armstrong & C. V. Fukami (Eds.),The Sage

hand-book of management learning, education and development(pp. 364–

383). London, UK: Sage.

Scherer, F. M., & Ross, D. (1990).Industrial market structure and

eco-nomic performance. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin.

Scherer, R. F., Javalgi, R. G., Bryant, M., & Tukel, O. (2005). Challenges of AACSB International accreditation for business schools in the United States and Europe. Thunderbird International Business Review, 47, 651–669.

Sun, S. (2011). Meta-analysis of Cohen’s kappa.Health Services and

Out-comes Research Methodology,11, 145–163.

Thompson, K. R. (2004). A conversation with Milton Blood: The new AACSB standards.Academy of Management Learning and Education,

3, 429–439.

432 K. E. BRINK ET AL.