A Sociolinguistic Profile of the

Biage Language Group

Papua New Guinea, Oro Province

Papua New Guinea

Oro Province

Rachel Hiley, Rachel Gray, and Thom Retsema

SIL International

®2015

SIL Electronic Survey Report 2015-011, May 2015 © 2015 SIL International®

The SIL-PNG language survey team conducted a sociolinguistic survey of Biage [bdf] from October 11th to October 17th and on October 30th 2006. The goals of the survey were to establish language and dialect boundaries, to assess language vitality, and to investigate the potential for a language development program.

iii

3.1 History of work in the area

3.1.1 Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) Church 3.1.2 Anglican Church

3.1.3 CRC/CMI 3.1.4 Other churches 3.1.5 Every Home for Christ

3.2 Language use parameters within church services 3.2.1 As reported

3.2.2 As observed 3.3 Summary

4 Education

4.1 History of schools in the area 4.2 School sites and sizes

5.1.1 Leadership and cooperation within language communities 5.2 Population movement

5.3 Marriage patterns

6 Language and dialect boundaries 6.1 Reported dialect boundaries 6.2 Lexical similarity

6.2.1 Results 6.2.2 Interpretation 6.3 Comprehension

6.3.1 Reported

6.3.2 Comprehension testing results 6.4 Summary

7 Language use and language attitudes 7.1 Reported language use

7.1.1 Language use by domain 7.1.2 Children’s language use 7.1.3 Adult’s language use 7.1.4 Reported mixing 7.2 Observed language use 7.3 Perceived language vitality 7.4 Bilingualism

7.5 Language attitudes 7.5.1 As reported

7.5.2 As Inferred from Behaviour 7.6 Summary

8 Recommendations

Appendix A: Characteristics of the language Appendix B: Wordlists

1 1.1 Language name and classification

Biage is spoken in Oro province, to the west of Kokoda, and is noted in Dutton (1969) as being the name of a tribe speaking Mountain Koiali that is often applied to “any non-Orokaiva, non-Chirima River [Fuyug] inhabitant of the Kokoda sub-district.” It is not currently listed in Ethnologue (Gordon 2005), but falls in the area covered by Mountain Koiali.

Figure 1. Mountain Koiali linguistic relationships (Ethnologue).

Most Mountain Koiali speakers live in Central Province, along the Kokoda trail. Mountain Koiali is classified by Ethnologue as: Trans-New Guinea, Main Section, Eastern, Central and Southeastern, Koiarian, Koiaric. There are three Koiaric languages: Grass Koiari, Koitabu and Mountain Koiali.

Figure 2. Mountain Koiali linguistic relationships (Pawley).

According to Pawley (2005:94), Mountain Koiali is classified as Trans-New Guinea, Southeast Papuan, Koiari, Koiaric.

During the survey Biage was always given as an acceptable name for the language. However, possible alternate names were given in the following Biage villages: in Ebea an alternative name of Humi; in Isurava the alternative name of Isurava; in Pelai an alternative name of Nona which also covers Mountain Koiali in Central Province. In this report the language will be referred to as Biage. After investigating linguistic and sociolinguistic factors, this report will consider Biage as being a separate language from Mountain Koiali.

1.2 Language location

1.2.1 Description of the area

The Biage people live in the foothills and steep mountains of the Owen Stanley Range in the Kokoda sub-district of Oro province. Many of the villages are situated on or near the famous Kokoda trail. They range in elevation from around 400 metres to over 1400 metres. The villages at lower elevation are situated among oil palm plantations and old rubber plantations, but as you leave the valley these are quickly replaced by rainforest. At the higher elevations it can become quite cold at night.

1.2.2 Maps

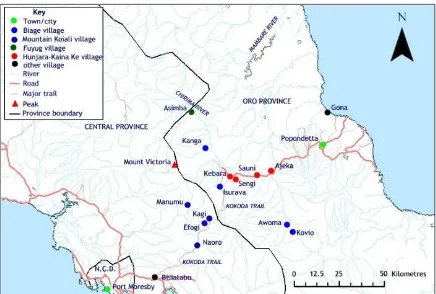

Map 1. Biage language area in Papua New Guinea1

1 Maps 1–5 were produced and are owned by the SIL PNG survey team. These maps attempt to represent linguistic

Map 2. Neighbouring languages

According to Ethnologue (Gordon 2005), the languages neighbouring Biage are classified as shown in figure 3 (language names are in bold). In 2007, Orokaiva [ork] was split into three languages: Orokaiva [okv], Hunjara-Kaina Ke [hkk]2 and Aeka [aez] (Gray et al. 2007a and 2007b).

2 The names Hunjara-Kaina Ke, Hunjara and Kaina Ke all appear in this report. When simply Hunjara or Kaina Ke

Figure 3. Classification of neighbouring languages.

Map 3. Area surrounding Biage Trans-New Guinea

Main Eastern

Binanderean

Binanderean Proper

Ewage-Notu [nou]

Orokaiva [ork] (including dialects Hunjara and Aeka) Central and South Eastern

Goilalan

Fuyug [fuy]

Koiarian

Baraic

Ömie [aom]

Namiae [nvm] Barai [bbb] Ese [mcq]

Yareban

Bariji [bjc]

Nawaru [nwr]

Map 5. Biage villages3

1.3 Population

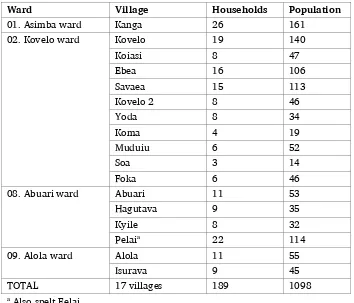

The National Census 2000 (National Statistical Office 2002) gives us the following information on the population of villages in the Biage area.

Table 1. Village populations

Ward Village Households Population

01. Asimba ward Kanga 26 161

02. Kovelo ward Kovelo 19 140

Koiasi 8 47

Ebea 16 106

Savaea 15 113

Kovelo 2 8 46

Yoda 8 34

Koma 4 19

Muduiu 6 52

Soa 3 14

Foka 6 46

08. Abuari ward Abuari 11 53

Hagutava 9 35

Kyile 8 32

Pelaia 22 114

09. Alola ward Alola 11 55

Isurava 9 45

TOTAL 17 villages 189 1098

a Also spelt Felai

Thus, according to the 2000 census, there were 1098 people living in the Biage area at the time of the 2000 census. Population growth in Oro province 1980–2000 was at a rate of 2.7% per year; if this was true of Biage between 2000 and 2006, the total population in 2006 would be nearly 1300.

1.4 Accessibility and transport

There is an airstrip at Kokoda Station, from which regular commercial flights go to Port Moresby. Car roads link Ebea and Kovelo to Kokoda and Popondetta. Public motor vehicles (PMVs) go to Ebea4 three

times a week and there is a PMV based at Kovelo which goes to Popondetta. Isurava and Alola may be reached by the Kokoda trail. There is a trail from Ebea to Kanga. There are trails linking Pelai with Isurava and with Kanandara in the Hunjara-Kaina Ke area.

1.5 Other background information

1.5.1 Previous research

Dutton (1969) defines Biage as the name of a tribe who populate Kovelo and Savaea, with some at Kanga. He also notes that “this term, has broadened in reference, until today it may be used to denote any non-Orokaiva, non-Chirima River inhabitant of the Kokoda sub-district.” Dutton’s research covers six dialects of Mountain Koiali, as shown in map 6.

The Biage and Isurava groups spoke what Dutton defined as the Northern dialect of Mountain Koiali. The other Mountain Koiali speakers living in Oro province were at Awomo and Kovio, which he defined as the Eastern and Lesser-Eastern dialects respectively. He also defined Southern, Central and Western dialects of the language, which are located in Central province. He estimated the total number of Mountain Koiali speakers to be 3734, much higher than Ethnologue’s current population estimate of 1700 (based on Dutton 1975). The New Testament was translated in Efogi which is located in the Central dialect and has the largest number of speakers. According to Dutton, it is also the most prestigious and dominant dialect. Garland (1979) echoes this view, noting that people “will often switch to Efogi talk in order to make us feel comfortable.” Dutton notes the following cognate percentages between the dialects of Mountain Koiali:5

Efogi – Kaili (central – northern): 79–82% Efogi – Awoma (central – eastern): 85–88% Efogi – Kovio (central – lesser eastern): 78–82% Kaili – Kanga (northern – northern): 89% Kaili – Awoma (northern – eastern): 73–75% Awoma – Kovio (eastern – lesser eastern): 82–85%

Garland (1979) has a much narrower description of Mountain Koiali than Dutton; he does not mention the villages in Dutton’s Western dialect at all, neither does he mention most of Dutton’s Southern dialect villages (only Naoro). Dutton’s Central dialect he splits into three dialects (Efogi, Kagi and Manumu). In Oro Province he mentions only Awoma and Kovio as one dialect and Isurava as another; he does not mention Kovelo, Savaea or Kanga villages. He notes that the differences between Mountain Koiali dialects are found in lexical and phonological variations with some variation in verbal endings.

Garland notes that “the Isulava [sic] and Efogi dialects are most dissimilar in vocabulary and intonation being 79% cognate.” He concludes that literature in Efogi dialect will be used easily by the three most central and Awoma dialects, and that Naoro (Garland’s southern dialect) and Isurava (Garland’s northern dialect) would be able to use it but it may not appeal to them as much because of the vocabulary differences.

In his letter to SIL in 1996, Cameron Venables listed 11 Biage-speaking villages: Kanga, Sawaia [sic], Ebe [sic], Kovelo, Isurava, Alola, Pelai, Kagi, Efogi and Manumu. The last three of these villages are in Central Province. According to Garland (2001 personal communication), Biage may include three villages in Central Province, one being Kagi, but Efogi is not a part of Biage. In our research, Biage people never included any Central Province villages in their definition of Biage. When they came up in conversation they were called Koiari, not Biage. Some people said the name Koiari also included Biage, but they said that the villages in Central Province were a different dialect.

2 Methodology

2.1 Village sampling

The survey team began the survey by visiting Efogi,6 the Mountain Koiali village where the New

Testament was translated. This was to collect a wordlist to compare with Biage and a recorded text test (RTT)7 to test Biage speakers’ comprehension of Mountain Koiali. A scripture extensibility test was also

pilot tested, but was not used in Biage as the test was found to be too hard (see section 2.2.5).

5 These villages are depicted on maps 3 and 4 in section 1.2.2 and on map 6 in this section with the exception of

Kaili, which is only depicted on map 6.

Before the survey the team planned to visit five Biage villages. The team tried to visit villages spread across the geographical area of the language, as there are most likely to be differences between villages that are further apart. The team tried to visit villages where there are different church

denominations and where there are elementary, community or primary schools. They were able to spend at least one night in five Biage villages. It was decided to test the RTT in Kanga, the Biage village

furthest from Mountain Koiali, and therefore likely to have the lowest levels of contact with Mountain Koiali.

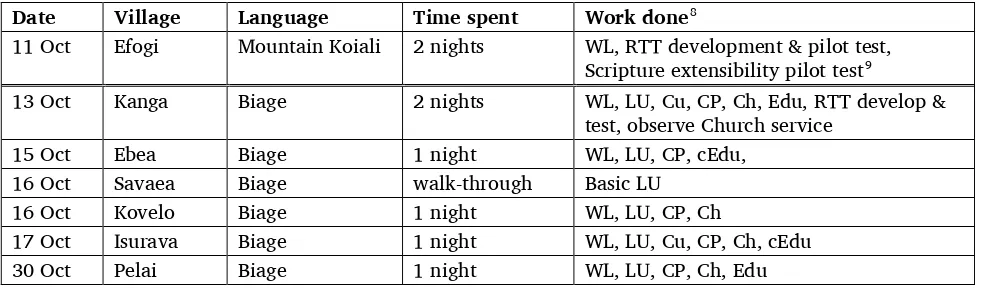

Table 2. Work schedule

Date Village Language Time spent Work done8

11 Oct Efogi Mountain Koiali 2 nights WL, RTT development & pilot test, Scripture extensibility pilot test9

13 Oct Kanga Biage 2 nights WL, LU, Cu, CP, Ch, Edu, RTT develop & test, observe Church service

15 Oct Ebea Biage 1 night WL, LU, CP, cEdu,

16 Oct Savaea Biage walk-through Basic LU

16 Oct Kovelo Biage 1 night WL, LU, CP, Ch

17 Oct Isurava Biage 1 night WL, LU, Cu, CP, Ch, cEdu

30 Oct Pelai Biage 1 night WL, LU, CP, Ch, Edu

2.2 Tools

Language and dialect boundaries were determined based on how people identified themselves,

lexicostatistical data, RTT results and reported comprehension. This information was gained from group language use interviews, wordlists and an RTT.

To investigate whether a language development project could be viable in the Biage language, information was collected on whether Biage speakers are already served by existing literature, and about the vitality of Biage. The survey team investigated whether comprehension (both as reported in group language use interviews and as evidenced by RTT data) and attitudes as reported in group interviews would allow people to use the existing Mountain Koiali literature. Language vitality was evaluated using group language use interviews and observation of language use.

2.2.1 Observation

Observation is a natural, unobtrusive way to find out what languages are being used in particular domains. It is helpful to have observations to either confirm or call into question reported language use data. What language(s) people use in particular domains may also give insight into language attitudes.

2.2.2 Sociolinguistic interviews

The survey team interviewed groups of people in each village about language use, culture, bilingualism and social contact patterns (including intermarriage, trade, immigration and emigration). The group interviews were guided by questionnaires developed by the Sociolinguistic Section of SIL-PNG. An effort was made to ensure that groups interviewed were representative of all people in the village; the survey

8 WL is wordlist, LU is language use questionnaire, CP is contact patterns questionnaire, Ch is church questionnaire,

Cu is culture questionnaire, Edu is education questionnaire, cEdu is community education questionnaire.

team tried to have members of both sexes and several age brackets participating in the interviews.10

Religious leaders and educators were interviewed individually in order to gain an overview of religious and educational institutions in the area. In villages with no school, a small group was interviewed about education levels in their village.

2.2.3 Wordlists

The standard SIL-PNG wordlist of 190 items (170 words and 20 phrases, 1999 Revision) was used for the duration of the survey. The 170 words were elicited in Kanga, Ebea, Kovelo, Isurava and Pelai in the Biage language and Efogi in Mountain Koiali. In addition to the 170 words, the 20 phrases were elicited in Kanga, Kovelo, Isurava and Efogi.

In each village where a wordlist was elicited, the community designated a few people to help with the wordlist. In every village except Isurava there were always at least two people (if not more) present for the wordlist elicitation. It was the desire of the survey team that at least a man, woman and one older person be present for every wordlist, but this was not attainable in every village. In Kanga there was only a man and a younger woman present, in Pelai there were only men at or below 30 years of age and in Isurava there was only one middle-aged man who was the ward councillor. The primary respondents were between 25 and 44 years of age and came from the village where the wordlist was being elicited. In Ebea and Isurava, Retsema forgot to ask whether or not the respondent was from that village. In most cases, both of the primary respondent’s parents were from the language with the exception of Pelai, where intermarriage with Kaina Ke is high and the primary respondent’s father was from Kaina Ke. The primary respondents from Ebea and Isurava were not asked where their parents were from; five of the primary respondents were men and one was a woman. All of the wordlists were elicited by Retsema. The elicitation sessions were recorded on minidisc, which included a recording of the informed consent of the primary respondent.

The wordlists were compared with each other to decide lexical similarity. Elicited forms were compared by inspection. When recognisable, only the roots were compared. Ultimately, Retsema used his own judgment in grouping forms as similar, though he usually conformed to the standard described in Survey on a Shoestring (Blair 1990: 31–33). Instances where there was departure from this method are described below.

For four of the items some forms were grouped as similar even though they did not meet Blair’s standard. In item 21 Isurava and Pelai were grouped with the others even though they had an extra syllable that the others did not have. In item 35 Kovelo was grouped with the other Biage villages even though it was missing an [a]. In item 54 Efogi was grouped with the Biage villages even though it had an extra [lo]. According to the Mountain Koiali dictionary by Garland and Garland (1983) the word for “go” does not contain that extra syllable. In item 163 Kovelo had an extra [u]. In another village it was explained that adding this vowel switches the meaning of the word from ‘you’ to ‘just you.’11

Of the 170 items elicited, twenty-one were not used in the lexical comparison. Eighteen were disqualified because they were duplicates of morphemes already compared in other items and three were disqualified due to confusion over what the gloss meant or elicitation of synonyms.

In eleven other items the form of one or more wordlists was excluded without the whole item being excluded. For one item Kanga, Ebea and Kovelo were excluded because the word for ‘boil’ was given instead of ‘hot’ (item 85), and for three items only the Efogi form was excluded because it seemed that

10 This was normally achieved. However, in Kovelo this was not possible and the respondents were one middle-aged

man and one young woman. In Isurava, although there was a small mixed group present, the main respondent was a middle-aged man who was the ward councillor.

the wrong gloss was given (see items 37, 66 and 120).12 One Kanga item was excluded because it also

seemed to be the wrong word (item 60).13 In three items the Efogi word was excluded because the

morpheme was the same as another morpheme that was already compared with another item (see items 2, 24 and 70). In two additional items the form for Efogi and in one item the form from Pelai was excluded because it was a borrowed word from Hiri Motu (items 43, 134 and 136).14

Of the 170 words on the SIL-PNG standard wordlist, five of the glosses were changed. Gloss 15, ‘foot’, was replaced with ‘sole’, as there was no word for ‘foot’ in Biage. Gloss 45 ‘rat’ was changed to ‘mouse’ as that was probably the form that was given and gloss 69 was changed from ‘he swims’ to ‘he washes’ for the same reason. Gloss 16 ‘big brother’ was changed to ‘younger same sex sibling’; gloss 17 was changed from ‘big sister’ to ‘younger opposite sex sibling’ because the terms for big brother and big sister do not exist in Biage, only ‘older sibling.’

In Mountain Koiali – English Dictionary (Garland and Garland 1983) [meʐia], the word given for ‘meat’ (item 114), is translated as ‘bush game’ and [taɣote], the word given for ‘red’ (item 149), is translated as ‘blood one.’ These forms were compared with the other forms elicited from other wordlists because Retsema believed that he consistently elicited the same form on all of the wordlists.

The forms elicited for the 149 items used in the comparison are listed in the appendices.

2.2.4 Recorded Text Tests

Besides asking people how well they understand Mountain Koiali, the survey team used comprehension tests (RTTs) to get a more direct measure of the intelligibility of Mountain Koiali by Biage speakers. The team followed the retelling method described in Kluge (2005), which requires that individuals listen to a recording of a short, unfamiliar narrative and repeat what they hear, segment by segment. The test is scored by counting how many core elements of the story the subject is able to repeat out of all of the core elements in the story identified by pilot testing with speakers of the recorded dialect. The survey team tested the story on people with little contact with Mountain Koiali in order to see how well Biage speakers can understand Mountain Koiali without learning it.

Test development

The Mountain Koiali test was developed in Efogi, the village where the New Testament was translated into Mountain Koiali, and tested in Kanga, the Biage village furthest from Efogi, and therefore least accessible from Efogi. It was assumed the speech there would be the most different from Efogi and people would have the least contact with Mountain Koiali. There does not appear to be much variation in Biage speech, but people from Kanga have virtually no contact with Mountain Koiali. In addition, people from Kanga had expressed an interest in developing the Biage language (see section 1.5.3). A story was also elicited in Kanga to use as a hometown test there.

The Efogi and the Kanga stories were each elicited from a local man in their respective villages, who had not spent long periods of time living elsewhere. After the story had been recorded, it was

12 The Efogi word given in 37 ‘big sister’ meant ‘big sister’, but the gloss was later changed to ‘younger sister’

because there was only a word meaning ‘older sibling’ in Biage. The Efogi word given for item 66 ‘he dies’ was

[lodoβanu] which is not in the Mountain Koiali – English Dictionary (Garland & Garland 1983). However, the word

[hatinu], which is the word ‘die’ in the dictionary, was given in item 65 ‘he kills.’ The Efogi word given for item 120 ‘wing’ was [atu ɡaβe], which, in the dictionary denotes ‘wing tips.’

13 The gloss given for item 60 ‘he says’ was [kose aɭu], which in Ebea it was explained to mean ‘Em i tok olsem’ in

Tok Pisin, meaning ‘He says it so.’ People in Ebea said that this is not the correct way to translate ‘He says.’

14 The respondent from Efogi said [magani] for ‘wallaby’ (item 43) and [bini] for ‘bean’ (item 134), both of which

written down in the language by someone from the village or by a surveyor, translated, and split into segments of one or two sentences.

As a pilot test, ten or more people who spoke the same language variety as the storyteller were given the test. The participants were played each segment in turn and asked to retell the story in Tok Pisin or English. Based on what was retold, the surveyor probed to make sure important details had not been left out. The answers were compared and core elements identified. An item was considered a core element if all or all but one of the pilot test participants mentioned it. If the survey team felt that a person was an unreliable test-taker, all their answers were ignored. The core elements form the scoring system for the test; each core element being worth one point. (A translation of the texts and the scoring systems may be found in appendix B.)

Sampling

The goal of the survey team was to test at least ten Biage speakers who were competent test takers and had low contact with Mountain Koiali. The reason that participants with low contact were used is that the survey team wanted to know how well people could understand the speech varieties because of the relatedness of the languages and not how well people had learned the other varieties. The survey team assumed that the people with low contact with Mountain Koiali were people who had not travelled to Mountain Koiali and who had little contact with relatives from the other areas. Therefore, participants were screened for contact through travel and relatives, and they were screened for competency through their performance on the test of their own speech variety. People who were judged to have had too much contact or did not score above 87.5% (21/24) on the Biage hometown test were not tested. All ten people who took the Biage hometown test passed and were tested on the Mountain Koiali text. They were between 12 and 40 years old, and none reported any contact with Mountain Koiali.

Test administration

The method for administering the tests was the same as with the pilot test. After collecting information about the participant, the test was given in Biage so the participant could get used to the test format and to screen for competency. To save time, the hometown test was not pilot-tested prior to administering, but scored afterwards as a pilot test and hometown test. If any of the participants had been judged unreliable test-takers, their scores would have been ignored. After the hometown test, the participants retold the story from Mountain Koiali. For both stories, the surveyors tried to probe when the subject left details out in his/her response. Following their retelling of the two stories, the participants were asked a series of attitude questions about the speech varieties they had listened to. The questions are listed below:

1 Is this your language? 2 Where is the speaker from?

3 Is the way he speaks the same as the way you speak? If no, is the way he speaks a little different / very different from the way you speak?

4 Did you understand everything, most things, a few things or nothing? 5 Which story was easiest to understand?

Scoring

The tests were reviewed individually and deviating responses discussed in comparison to base-line responses and responses by other participants and scored accordingly. Some responses were given half credit. The contact details for participants were also reviewed. If participants were found to have scored under 87.5% on the hometown test, or if they were judged to have had too much contact with the other varieties, then their scores would have been ignored.

Limitations of RTT testing

[lasi]. These words are borrowed from languages of wider communication, so test takers might have scored higher than if the stories were told using only vernacular words. The survey team decided to count core elements containing borrowed words anyway because it was impossible to consistently exclude core elements with loanwords—the survey team could only identify loanwords from Tok Pisin and English, but not from any other language unless the people transcribing the story pointed them out. Furthermore, Casad (1974:13) states that if the subjects “referred to entire phrases, each containing only one loan, then systematic bias would probably be negligible.” Also, storytellers had been requested to avoid using loanwords, so it was felt that those that remained were probably commonly used and could be considered part of the vernacular, especially as there is no vernacular alternative for ‘soap’, ‘towel’ and ‘radio’. The word for ‘soap’ confused at least one subject (E11) who, when retelling that segment, said (in Tok Pisin) “he’s talking about going to wash, fetches his soap, no not soap, sobota… I went to wash and came back. I do not want to mislead you…” Only three test-takers mentioned soap and towel when retelling the story.

Another weakness with this RTT test is that it is testing understanding of a simple Mountain Koiali narrative as it is currently spoken as opposed to Mountain Koiali as it is written in literature from more than 20 years ago. As we do not know how much the languages have changed, we cannot draw

conclusions about the understanding of the Mountain Koiali literature from this test.

3 Churches and Missions

The church is one of the main social institutions in Papua New Guinea. Thus, the attitudes of churches towards community projects, such as language development, significantly influence the potential success of a project.

Church parish or district boundaries can cover multiple language groups. Where it is known this is the case, we have included the names of the congregations outside the Biage area that are within the same church districts/parishes.

3.1 History of work in the area

3.1.1 Seventh-day Adventist (SDA) Church

The first SDA missionaries arrived in PNG in 1908, setting up a mission station at Bisiatabu, Central Province (50 kilometres east of Port Moresby) in 1909. In 1924 the missionaries moved inland along the Kokoda trail, establishing a mission at Efogi (Jones, 2004:26–31). Local Christians reported that the mission continued to follow the Kokoda trail, reaching Isurava in 1960 and Kokoda in 1961. The SDA church came to Pelai in 1998 when two Pelai men brought it from Hagutava and the church building was dedicated in 2000.

There are currently SDA churches in Abuari, Alola, Isurava, Hagutava and Kokoda Station. There are currently SDA hand-churches15 in Hoi and Pelai. Inside Kokoda district there are also SDA

congregations in the neighbouring Hunjara-Kaina Ke language at Sirorata, Asisi, Bouru, Hamara, Sairope and Waju and in the Ömie language at Asafa and Enjoro.

3.1.2 Anglican Church

The Anglican Church arrived in the Wedau language area of Milne Bay in 1891 and set up the first mission station at Dogura. Their work predominantly took place in Milne Bay until 1900 when the first permanent mission station on the Mambare River in Oro Province, in the Binandere language area, was

begun (Wetherall 1977:37). Later they went up and down the Oro coast, arriving in Gona (Ewage-Notu) in 1922. The mission moved inland, eventually reaching Saga (Kaina Ke) and erecting a church building there in 1951. They came to Kanga in 1969, and the first building was built there in 1972.

Historically the Anglican Church has encouraged people to use their local language in church services. Some of the first missionaries translated some hymns, liturgy and portions of scripture into Ewage-Notu, Orokaiva and Binandere. The current Bishop is trying to allocate priests so that they work in their own language area, and use the local language.

People from Kanga and Ebea attend the St. Paul’s Chapel16 at Kanga. They are part of Saga parish,

along with Kokoda Station and the Kaina Ke villages of Botue, Amada and Kokoda.

The parishes of Saga, along with Sairope (Hunjara), Asafa (Ömie), Eiwo (Hunjara), Gorari (Hunjara-Kaina Ke), Kebara ((Hunjara-Kaina Ke) and Emo River (Ömie) form Kokoda Deanery. Priests are required to occasionally preach at different churches within the deanery. The Mothers Union have monthly deanery meetings.

3.1.3 CRC/CMI

Originally these churches were Christian Revival Crusade (CRC) churches. The first CRC church in the area was in Ajeka, in the mid-1970s, and was started by a man from Ajeka who went to visit his sister in Port Moresby and brought the CRC denomination back. In 1978 the CRC church was started in Kovelo by a pastor from Australia.

Around 2003 most CRC churches in the Kokoda district changed to Covenant Ministries International (CMI). Different churches reported different underlying reasons for the change. The governing church for Kokoda district is at Sauni (Hunjara).

It was reported that there are currently CMI churches in Kovelo and Kokoda Station. The governing church for Kokoda district is in Sauni (in the Hunjara-Kaina Ke language). The other 16 CMI churches in the district are located in the Hunjara-Kaina Ke area. It was reported that there is only one CRC church in the area, at Kokoda Station.

3.1.4 Other churches

There are some members of the Catholic Church in Kanga. There is a Catholic church in the next village, which is Asimba or a hamlet of Asimba (in the Fuyug language area). There is also a Catholic church at Kokoda Station, a New Apostolic Church at Savaea and a Renewal church at Pelai.

There are some Jehovah’s Witness members in Savaea. The survey team saw a large, permanent, metal Jehovah’s Witness Kingdom Hall at Kokoda Station, but did not manage to find out if there were any members in the Biage area. Members of Jehovah’s Witness have reportedly visited Kovelo to witness.

3.1.5 Every Home for Christ

In Kebara (Hunjara-Kaina Ke) there is a team of ten people working with Every Home for Christ, an interdenominational mission. Currently they are the only team in Oro Province. They visit home to home in the Kokoda area so that everyone may hear the gospel.

The mission started in 1946 in Canada and came to PNG in 1996. Kebara will be hosting a national gathering of Every Home for Christ in November 2006.

3.2 Language use parameters within church services

3.2.1 As reported

Kokoda SDA and Holy Trinity Church (Anglican, Saga) both use mainly English and Tok Pisin for all church services, as well as Sunday school and women’s groups. However, Holy Trinity Church also uses Kaina Ke, but not Biage, as reportedly most of the congregation is Kaina Ke and also the Assistant Priest is a Kaina Ke speaker. Kokoda SDA uses Biage but not Kaina Ke (most of the congregation are Biage speakers, and the pastor is a Biage speaker); they also make use of some Motu and Orokaiva.

For Isurava SDA, Pelai SDA, Kovelo CRC and St. Paul’s Anglican Chapel (Kanga) announcements and sermons are reportedy always in Biage. Scripture reading is mostly English, except that Isurava SDA also uses Mountain Koiali. Isurava SDA, Kovelo CRC and St. Paul’s Anglican Chapel all use Biage for spontaneous prayer; however Pelai SDA uses Tok Pisin. Songs are in English, Tok Pisin or other languages.17 Only St. Paul’s Anglican Church reported using Biage primarily; the other three reported

using it occasionally. Pelai SDA and Isurava SDA sing mainly in English. Kovelo CRC sing mainly in English, Tok Pisin and Kaina Ke. The congregation chairman of St. Paul’s Chapel in Kanga reported that many people there have written many songs in Biage. People in Pelai have adapted five songs from Mountain Koiali into Biage. People in Isurava said that there are people in a settlement in Port Moresby who have also been writing Biage songs, which they also occasionally sing. People in Kovelo occasionally use the songs that people in Kanga and Ebea have written.

Women’s groups and youth services held in Isurava SDA, Pelai SDA, Kovelo CRC and St. Paul’s Anglican Chapel are all in Biage, when there are meetings. Only Pelai SDA reported using Biage during Sunday school. Isurava SDA reportedly uses predominantly English during Sunday school. St. Paul’s Anglican Chapel uses Tok Pisin in Sunday school which may be evidence of some language shift.

Apart from Kokoda SDA and Holy Trinity Church (since they have so many people from other language groups), the churches mainly use Biage for anything spoken, English for anything written, and the singing is mostly in English or Tok Pisin. St. Paul’s Anglican is the only church to write worship songs in Biage and use them extensively.

3.2.2 As observed

The survey team was able to attend one church service at St. Paul’s Chapel in Kanga. English was used for the Bible readings and liturgy as well as two hymns, but Biage and Tok Pisin were used more frequently for songs and prayers. At the beginning of the service, the leaders said that they would alter their language use because of the visitors. There was no reported use of Tok Pisin (unless the

congregation was mixed), but it was used during the service that the survey team attended. There was no one licensed to give a sermon, so the team were unable to observe which language they used for

sermons.

3.3 Summary

All churches in Biage villages used some Biage in their church services, but St Paul’s Anglican Chapel in Kanga was the only church that reported composing many worship songs in the language, and using them extensively. Two people from Ebea have been trying to translate scripture and the Anglican liturgy into Biage language.

Many churches in the area reported falling membership. However, Isurava SDA and Pelai SDA reported that more people attend Sabbath school than there are church members.

4 Education

In order to ascertain the language group’s capability to contribute to a language development programme, the survey team sought to gain information in the area of education. In particular:

1 What is the average level of education?

2 Who in the communities has secondary level education? What are these people doing now? 3 Do the communities value education?

4 What is the literacy rate in the communities?

To this end, the team spoke to teachers or residents in each village asking about school attendance; how many people had finished grade 6, grade 8, grade 10 and beyond; general literacy levels; and attitudes toward education. The survey team also sought to gather information on the existence of and attitudes towards vernacular education.

4.1 History of schools in the area

Kanga Community School was started in 1983; previously students went to school at Kokoda. There are elementary schools in Alola, Savaea, Pelai and Kovelo villages. Elementary schools may have previously existed in Kanga and Ebea, but there were none there at the time of the survey. There was a Tok Ples Prep School18 in Pelai from 1993, run by one of the current elementary teachers there. Classes at Pelai

Elementary are temporarily suspended.

4.2 School sites and sizes

The schools in the Biage area are listed in table 3.

Table 3. Schools in the Biage area

School Name Location/Year Founded Grade Levels Savaea Elementary School Savaea EPa, E1b, E2c

Pelai Elementary School Pelai / 1998 (TPPS from 1993)

EP, E1, E2 (all grades were suspended at the beginning of term 3, 2006; they hope to start again in November) Alola Elementary School Alola

Kovelo Elementary School Kovelo

Kanga Community School Kanga/1983 1, 2, 3, 6 (grade 6 & possibly other grades are currently suspended)

Abuari Community School Abuari 1–6

Kokoda Primary School Kokoda Station 3–8 a Elementary prep

b Elementary grade 1 c Elementary grade 2

18 Tok Ples Prep Schools (“vernacular prep schools”) are local educational institutions that use the local language to

4.3 Enrolment, attendance, academic achievement

4.3.1 Elementary school enrolment

The only elementary school where the survey team was able to interview was Pelai Elementary School. There are fifteen students in EP, ten in E1 and eight in E2. Students come from Pelai, Kyile and Hagutava villages. All classes were suspended at the beginning of term 3 in 2006 as some people had gone into the classrooms and written graffiti on the board with chalk. They hoped to resolve the problem and restart classes in November 2006.

4.3.2 Primary school enrolment

Kanga Community School reported that grade 6 (eighteen children enrolled) is currently suspended. The survey team heard other reports that grade 2 (twenty seven children enrolled) or grade 3 (twenty one children enrolled) may also be suspended. No one reported that grade 1 (twenty children enrolled) was suspended. Kanga Community School serves Kanga, Ebea (Biage) and Asimba (Fuyug language). Five children from Ebea attend Kokoda Primary School and two students from Kanga attend grade 7 in Kokoda. Many children do not attend school at all. School children from Isurava and Pelai attend Abuari Community School and Kokoda Primary School.

Of the ten students who graduated from E2 at Pelai elementary in 2005, seven started grade 3, (at Kokoda) but only one was still in school at the time of the survey. The reasons were school fees and the long distance to walk to school. Although some stayed with relatives closer to school, some walked every day and it was reported by the elementary teacher that they may not have breakfast before they leave so they were very tired and hungry at school.

4.3.3 Secondary school enrolment

There is one student from Ebea in grade 10 at Popondetta Secondary School in Popondetta. There may be one grade 12 student from Ebea currently attending secondary school in Lae.19

4.3.4 Literacy and academic achievement

At the time of the survey, not many people were literate. Less than half the people in Kanga know how to read; Pelai and Ebea reported that only a few people can read, Pelai saying maybe only three or four men and three women can read. Ebea and Pelai reported that there are people who can read English, Biage and Tok Pisin. The teacher at Kanga School reported that literate men could read Tok Pisin, Hiri Motu and Biage and literate women read Biage, Tok Pisin and Hiri Motu.

The people in Pelai were very interested in having a literacy program. One of the current

elementary teachers ran an adult literacy program in 1994 in addition to the Tok Ples Prep School, but he was unable to continue because he had too many other commitments. He said that the community thought literacy was very important and some adults who were listening echoed his sentiment saying, “yes, we want school.” The people interviewed in Isurava, Kanga and Ebea also said that the community felt that literacy was important.

The alphabet used in elementary schools in Savaea and Pelai may be different. Pelai reported that their alphabet was A, B, D, E, F, G, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, S, T, U, V. Savaea reported the same alphabet but did not mention ‘S’, though this could have been due to an oversight.

19 People in Ebea said that there is one grade 10 finisher in Lae, though they did not know if he was working or

Table 4 shows the number of people who have finished each grade level in their respective villages. It also includes how many other people who have finished each grade level and have moved elsewhere. The first number in each box represents the number of school leavers living in the village and the second number represents the number of school leavers from that village who have work elsewhere, with notes on the kind of work or place. You can see that Ebea and Kanga have many more finishers, particularly from grade 6 and 8, than Isurava or Pelai, probably due to the fact that there is a community school in Kanga. However, a surprisingly high number of people from Isurava have studied beyond grade 10, although of the 13 people who have studied grade 10 or higher, only three currently live in the village.

Table 4. Academic achievement in Biage

Village (pop.) Grade 6 Grade 8 Grade 10 Grade 12 Other Ebea (137)

15/0 12/0 7/1 in Lae 0/0

0/1 has a diploma of theology & is a priest in Wanigela

There are many people who do not attend school, with even fewer people having been to secondary school. Although many of them have moved elsewhere, there are still some secondary school graduates in the villages, particularly Kanga and Ebea. There were also many more primary school graduates in Kanga and Ebea, presumably due to the proximity of Kanga Community School. The villages that the survey team visited felt that literacy was important, although the literacy rate and school attendance was low.

5 Social sketch

5.1 Social cohesion

5.1.1 Leadership and cooperation within language communities

Each clan has its own leader called the [ata kitai], [kosi kitai] (both meaning ‘big man’) or they use the loan word ‘lawyer.’ His main work is to lead the people with events that come up and resolve any conflicts that may arise. There is also a chief who leads all of the clans or sub-clans. His title is the same as the titles used for the clan leaders, but his work is to get all the leaders together to resolve conflicts between people of different clans or sub-clans. He is also the one who speaks on behalf of the rest of the community. In matters pertaining to the government, the ward councillor and his committees are the leaders. Both in Kanga and Isurava it was agreed that people generally respect the leaders.20

Community work typically includes working for the church and the government, though some will also do work for the school. Typically, the leader of the given institution (the committee or councillor for

government work and the church council for church work) also leads the community in work associated with that institution. One day a week is generally set aside for government work and another for church work, so that two days a week are used for community work. Another day may be set aside for school work, as in Kanga, where it was reported that Monday is designated for the school, Wednesday for the church and Friday for the government. In Isurava and other villages along the Kokoda Trail, government community work usually consists of maintaining the trail.

In both Kanga and Isurava it was reported that attendance for community work days is not very high. Only a few people come each time. In Kanga it was reported that some people help others who need help with their garden, building a new house or working their cash crop, such as vanilla or coffee.

5.2 Population movement

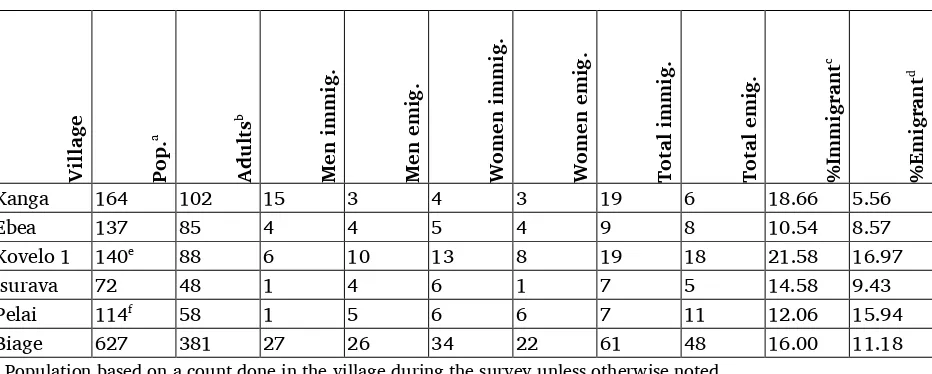

Landweer (1991) includes immigration and emigration as factors which influence the vitality of a language. Specifically, she considers it a higher likelihood that immigration becomes a factor detracting from language vitality if the immigrants are not proficient in the local dialect and the percentage of adults immigrating to the group is more than 10%. She considers it more likely that emigration is a factor detracting from language vitality if the percentage of adults emigrating from the group is more than 10%, and emigrants do not maintain the language of and identification with the group in their new location.

Table 5 tallies the number of male and female immigrants and emigrants for five Biage speaking villages and gives the total for all five villages. This information was elicited from a small group of people in each village. They were asked to think of men and women who had immigrated to their village and of men and women who had emigrated from their village. The percentage of the population above 15 years of age that has immigrated is listed in the ‘Immigrant %’ column and the percentage of the population above 15 years of age that has emigrated is listed in the ‘Emigrant %’ column.

Table 5. Immigration and emigration for Biage

V

a Population based on a count done in the village during the survey unless otherwise noted.

b The number of adults was calculated for each village, using the figure for percentage of population under 15 given

in the 2000 National Census. Age 15+ is considered to be adult in this case because some females as young as 15 may have married in to the village.

c The percentage is the number of male and female immigrants divided by the adult population.

d The percentage is the number of male and female emigrants divided by the adult population including the number

of emigrants.

e Population taken from the 2000 National Census.

Immigration is over 10% in all the Biage villages, which may detract from language vitality. Generally immigrants develop passive bilingualism but do not learn to speak Biage. In Kovelo ten of the people who have married in are reported to be able to speak Biage, three of the people married into Isurava are reported to speak Biage and in Pelai all the people who have married in can speak Biage. The majority of immigration is due to intermarriage, with the exception of Kanga where nine of the men have moved there to live but have not married a woman from there.

In Kanga 49% of children with at least one immigrant parent cannot speak Biage, in Ebea 76% of children with at least one immigrant parent cannot speak Biage, in both Kovelo and Isurava 22% of children with at least one immigrant parent cannot speak Biage. In Pelai all children with at least one immigrant parent can speak Biage.

In Kanga and Ebea, the rate of immigration along with the tendency of immigrants not to learn to speak Biage and many of their children not learning to speak Biage is detracting from language vitality. In Kovelo and Isurava there is some detracting from language vitality, but more immigrants are learning to speak Biage and the majority of their children learn to speak Biage. In Pelai, although there is a substantial rate of immigration, immigrants learn to speak Biage and all their children learn to speak Biage, so immigration is not having as large an effect on language vitality in Pelai as in other Biage villages.

Emigrants are generally reported not to continue using Biage away from the village, with the exception of emigrants from Isurava. The majority of male emigration is due to work, mainly in Port Moresby, and the majority of female emigration is due to marriage. Children of emigrants are generally reported not to know Biage. Emigrants are said to return to visit mostly at Christmas, and occasionally for other holidays. Emigrants from Ebea, Isurava and Pelai all use Biage when they return. Emigrants from Kanga are reported to use Tok Pisin when they return as they only know a little Biage. Emigrants from Kovelo are reported to use both Tok Pisin and Biage when they return if they have gone to Port Moresby, while emigrants who have moved further away are reported to only use Tok Pisin when they return as they have forgotten how to speak Biage.

There is a settlement of people originally from Isurava in Port Moresby, with about 20 adults and their children living there. People from this settlement are reported to write worship songs in Biage which are occasionally used in Isurava. No other settlements of Biage speakers were reported.

Overall the rate of emigration is higher than 10%, although Kanga, Ebea and Isurava all have lower rates of emigration. Rates of emigration from Kovelo and Pelai are well over 10%. Generally emigrants do not maintain the language of and identification with Biage in their new location. Due to these factors, emigration has a higher likelihood of detracting from the vitality of the language.

5.3 Marriage patterns

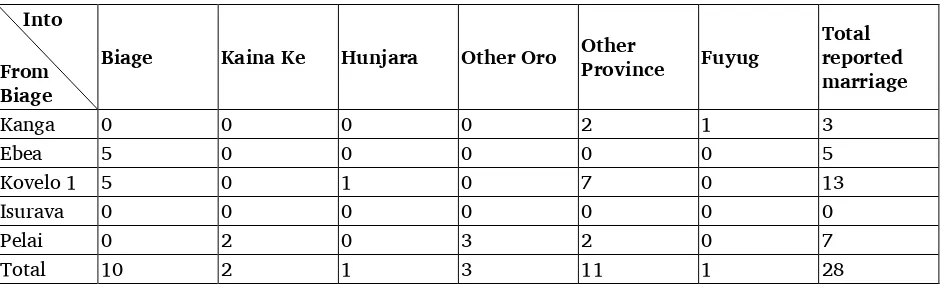

Table 6 and table 7 show reported marriage into and from Biage villages. Table 6. Reported marriage into Biage villages

From Into

Biage Biage Koiali Hunjara Orokaiva

Other

a The Guhu-Samane language is spoken in the mountains across the border of Morobe and Oro provinces. The closest

Table 7. Reported marriage from Biage villages

The majority of marriage into Biage villages is from outside the Biage area. There are high numbers of people from Orokavia marrying into Biage villages, especially Kanga, Ebea and Kovelo. Kanga has a high number of people marrying in from Guhu-Samane, a language spoken around the Morobe-Oro border.

The majority of marriages from Biage villages is outside the Biage area, the highest proportion marrying outside of Oro Province into many other PNG provinces.

Pelai has links with the Ese language with three women from Ese marrying into the village and three Pelai women marrying into Ese.

5.4 Contacts with other languages

Biage speakers have fairly regular contact with both Kaina Ke and Mountain Koiali speakers. People in Isurava especially have a lot of contact with Mountain Koiali speakers passing through every day working as porters and guides on the Kokoda trail.21 Biage speakers meet Kaina Ke speakers at Kokoda

Station. People from many different languages meet at the market at Kokoda Station and at the market on the Mamba Estate.

In the past, people in Pelai traded with Kaina Ke and people from Kanga traded with people from Fuyug. In the past people from Biage fought with people from Orokaiva and Kaina Ke.

6 Language and dialect boundaries

One goal of the survey was to determine whether Biage is a dialect of Mountain Koiali or a separate language. In addition to eliciting wordlists, the survey team also conducted group interviews to investigate speakers’ opinions on language distinctions, ethnolinguistic identity and reported comprehension.

According to ILAC Conference recommendations (1991), the minimum criterion that two speech forms should meet to be called the same language is a lexical similarity of 70% (at the upper confidence limit) and intelligibility of at least 75%. Ethnologue (2005:8) applies additional criteria to help

classification of speech varieties:

• two related varieties are normally considered varieties of the same language if speakers of each variety have inherent understanding of the other variety (that is, can understand based on knowledge of their own variety without needing to learn the other variety) at a functional level;

21 It seems reasonable to assume that this is true of all villages on the Kokoda trail, though the team did not ask

• where spoken intelligibility between varieties is marginal, the existence of a common literature or of a common ethnolinguistic identity with a central variety that both understand can be strong indicators that they should nevertheless be considered varieties of the same language;

• and where there is enough intelligibility between varieties to enable communication, the existence of well-established, distinct ethnolinguistic identities can be a strong indicator that they should nevertheless be considered to be different languages.

6.1 Reported dialect boundaries

There is consensus that there is a speech variety called Biage which covers Kanga, Ebea, Savaea, Kovelo, Isurava, Alola and Pelai. Various other smaller villages and hamlets are also part of Biage.

Mountain Koiali was often seen as being another dialect of the same language, but there is no name covering both Biage and Mountain Koiali. Mountain Koiali is not an acceptable name to Biage speakers, though there is some shared identity between the two groups.

Within Biage there were generally two reported dialects: Isurava and Alola were always grouped together; Kanga and Ebea were also always grouped together. In Kanga, Ebea and Savaea the dialect groupings were: Kanga, Ebea, Savaea and Kovelo in one dialect and Isurava and Alola in the other dialect. Pelai was not mentioned. In Isurava and Pelai the dialect groupings were: Kanga, Ebea and Savaea in one dialect and Kovelo, Pelai, Isurava and Alola in the other dialect. In Kovelo more dialects were listed. Kanga and Ebea were reported to be one dialect, Savaea another, Kovelo another, Pelai another and Alola and Isurava were the final dialect. Reported data suggests there is a mountain dialect and a lowlands dialect of Biage.

6.2 Lexical similarity

6.2.1 Results

Table 8 is a percentage matrix of similar forms of the words compared between the five Biage villages and one Mountain Koiali village where wordlists were elicited.

Table 8. Lexical similarity between Biage villages

Kanga - Biage 100 Ebea - Biage

99 99 Kovelo - Biage 97 98 99 Isurava - Biage 95 97 98 99 Pelai - Biage

80 80 79 82 81 Efogi - Mt. Koiali

6.2.2 Interpretation

The lexicostatistical ties among all of the Biage villages are very strong. With 95% as the lowest percentage between any two villages and the average percentage 98%,22 it is evident that there are no

major dialectal differences within Biage.

There is an average of 80% lexical similarity between the Biage villages and Efogi,23 which is about

the same as Dutton (1969) and Garland (1979) concluded between Efogi and the “Northern Dialect” of Mountain Koiali (Biage). Being well above the 70% lexical similarity threshold, the two varieties could

be considered one language. However, as our definition of language shows, other factors need to be considered.

6.3 Comprehension

6.3.1 Reported

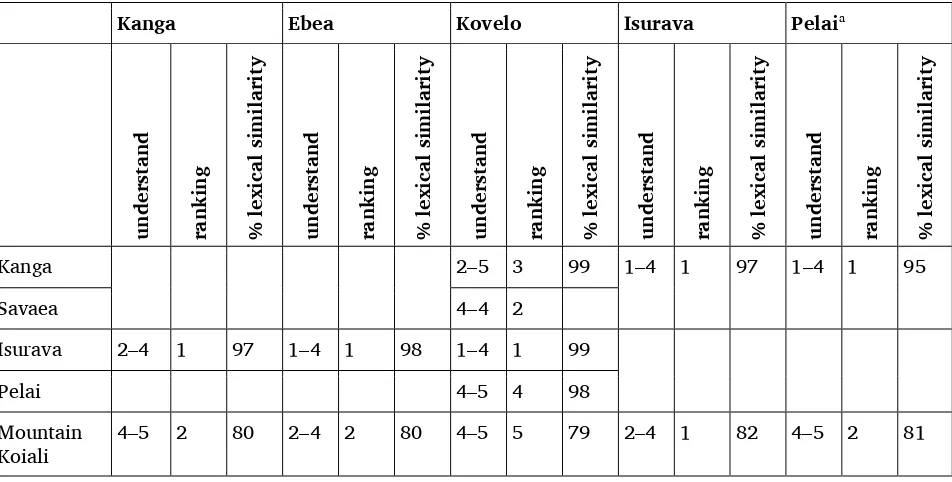

During group interviews in five Biage villages, the survey team asked interviewees how well they can understand other dialects and languages in the area. Specifically, they asked how well adults can understand different varieties and how well children about six years old can understand them. Finally, they asked respondents to rank the varieties from easiest to most difficult to understand.

Responses about how well people understand were interpreted on a scale of one to five: 1= they understand everything; 2= they understand most things; 3= they understand about half; 4= they do not understand most things; 5= they understand nothing. What people reported is shown in table 9. In the table, the first column under the village gives the level of understanding reported for adults followed by the level of understanding reported for six-year-old children.24 As six-year-old children have probably

had little contact with other speech varieties, reports about what they can understand can be indicative of the inherent intelligibility of varieties rather than comprehension resulting from contact. For example, in Ebea, people reported that adults understand everything that people from Isurava say, but children only understand a little. The second column under each village name shows the order that people ranked each language according to which is easiest to understand. For example, people in Kanga reported that of the varieties in the table, Isurava is easiest to understand, followed by Mountain Koiali. Languages that were given the same ranking were considered equally intelligible. The third column shows the lexical similarity percentages.

Table 9. Reported comprehension compared with lexical similarity

Kanga Ebea Kovelo Isurava Pelaia

a Pelai also reported that adults could understand everything in Kaina Ke and 6-7 year old children could understand a

small amount of Kaina Ke. They said Kaina Ke was easier to understand than the dialect of Mountain Koiali spoken in Efogi. This is probably due to bilingualism as there has been intermarriage with Kaina Ke in the past.

Adults in all villages but Kovelo reported that they can understand everything or most things in other varieties of Biage. In Kovelo, adults were reported to understand everything in Isurava and Kanga but only a little of Savaea and Pelai. Adults in all villages reported that children understand little or nothing of other varieties of Biage. If we assume that reports about what young children can understand are indicative of the inherent intelligibility of the varieties, it seems that that different varieties of Biage are not inherently intelligible at a level at which speakers could share literature.

Mountain Koiali is generally reported to not be well understood by Biage adults. Biage children are also reported to understand little or nothing of Mountain Koiali. This suggests Biage and Mountain Koiali could not share literature.

6.3.2 Comprehension testing results

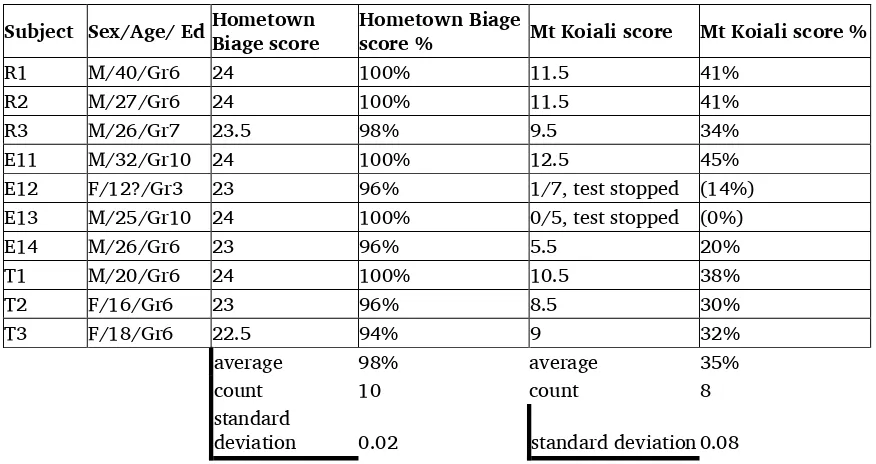

The scores of each individual are shown in table 10. Most scores were between 20% and 45%. Two candidates appeared to find the story so difficult that the test was stopped early. (The candidates had scored 1/7 (E12) and 0/5 (E13), the percentages for what they had heard would be 14% and 0% respectively.) If these two are excluded, the average score is 35%, with a standard deviation of 8%; if they are included, the average goes down to 29% with a standard deviation of 14%.

Table 10. RTT results

That all of the scores are under 50% indicates that it is very hard for Biage speakers to understand Mountain Koiali without learning it. A score of below 70% usually indicates that understanding is too low to share literature. Mountain Koiali is therefore not inherently intelligible to Biage speakers.

After hearing the story, most people classed it as a different language, and identified it as Mountain Koiali. Five of the candidates said that it was very different from their language; three said it was a little different and the two who stopped early were not asked.

Only one candidate (R2) claimed to understand more than a little of the story. He said he understood a lot and was one of the highest scoring candidates, with 41%. The rest said that they understood little or nothing.

RTT results indicate that Mountain Koiali and Biage could be classed as different languages. The low scores suggesting low inherent intelligibility and the stated opinions of speakers during RTTs (that they are two languages) are indicators that understanding of the Mountain Koiali literature may well be low.

Subject Sex/Age/ Ed Hometown Biage score Hometown Biage score % Mt Koiali score Mt Koiali score %

R1 M/40/Gr6 24 100% 11.5 41%

However, it should be noted that as the existing literature is in a form of Mountain Koiali spoken 20 or 30 years ago (when the two varieties were closer), that is not necessarily the case.

6.4 Summary

Reports varied as to whether Biage and Mountain Koiali were separate languages: during language use interviews, interviewees often classed them as one language; however, during RTT testing often they were viewed as more distinct.

Usually interviewees could not give a name that covered both groups. This could indicate something of a separate identity between the two groups; however it could equally be irrelevant. Speakers of many languages in PNG do not use established language names.25

Within Biage, everyone reported dialect differences between villages, often identifying a

northern/lowlands dialect including Kanga, Ebea and Savaea, and a southern/mountain dialect including Isurava and Alola. Reports of which dialect Kovelo and Pelai belong to varied. It was usually reported that adults could understand other Biage varieties well, although children could not, which may mean that there would be difficulties in sharing literature within Biage. Adults reported finding Mountain Koiali hard to understand; the RTT results show that very clearly.

Lexical similarity percentages show that Mountain Koiali is clearly a different variety to Biage, with 80% similarity. However, should they be classed as different languages? Although lexical similarity is above the 70% threshold, Biage speakers reported low intelligibility between the two varieties and they also struggled to understand the Mountain Koiali RTT story. This surprisingly low intelligibility

(considering the 80% lexical similarity) could be the result of a number of issues including differences in discourse, phonology or grammar. It could also reflect separate ethnolinguistic identities of the two groups, a case of speaker-attitude affecting intelligibility. Whether this seemingly low intelligibility is a result of linguistic differences or attitudes resulting from a perception of ethnolinguistic differences, for our purposes (according to the definition of language given earlier) the result is the same: the two varieties must be classed as separate languages.

7 Language use and language attitudes

7.1 Reported language use

7.1.1 Language use by domain

During group interviews in five Biage villages, people were asked which language they used in various domains. The answers are shown in table 11. An asterisk (*) indicates the dominant language in a domain and shaded squares are ones where Biage is dominant.

Table 11. Language use in Biage villages by domain

Kanga Ebea Kovelo Isurava Pelai

Family at home Biage Biage *Biage,

Tok Pisin

Biage Biage

Arguing at home *Biage, Tok Pisin

25 For example, the only “name” speakers of the Siar-Lak language all agree on is a phrase meaning “our language”

Kanga Ebea Kovelo Isurava Pelai

Praying at home *Biage, Tok Pisin,

Outsiders Tok Pisin Tok Pisin Tok Pisin, Motu

Song composition Biage *Biage, Tok Pisin

a Tok Pisin only when outsiders come b Biage is used with other Biage speakers.

c Young people use Tok Pisin. Old people use Motu. d Playing with outsiders

e Depends on the complainant

f If there is an outsider there then Tok Pisin, English and Motu are used.

Biage is reported to be the dominant language in many domains. Tok Pisin is also reported to be used in many domains, although generally Biage is reported to be used more.

The use of Biage is particularly strong in the home and for traditional customs with four out of five villages reporting that Biage is used exclusively in these domains. The reports of mostly Biage being used for joking suggest that the language is strong.

7.1.2 Children’s language use

In Ebea, Savaea, Kovelo and Isurava it was reported that children use both Biage and Tok Pisin with their brothers and sisters, with more Biage than Tok Pisin. In Kanga it was reported that the children use Biage and Tok Pisin with their brothers and sisters; how much Tok Pisin they use depends on whether the children are from a mixed marriage or not. Children with an immigrant parent are reported to use more Tok Pisin than those with two parents from Biage. In Pelai it was reported that children only use Biage with their brothers and sisters.

In Kanga, Ebea, Savaea, Kovelo, Isurava and Pelai it was reported that children use only Biage with their parents and grandparents, the only exception being children from mixed marriages in Kanga who are reported to use Tok Pisin as well as Biage with their parents and grandparents.

Children in Kanga, Isurava and Pelai are said to be able to speak Biage well by the time they start school. In Ebea and Kovelo children are reported to occasionally make a few mistakes in how they speak Biage when they start school.

Children in Kanga, Ebea, Kovelo, Isurava and Pelai are all reported to learn Biage before they learn any other language.

7.1.3 Adult’s language use

Young men and women in Kanga and Pelai are reported to use Biage with their brothers and sisters, parents and grandparents. Young people in Ebea and Isurava are reported to use only Biage with their parents and grandparents, but use a little Tok Pisin, English and Motu with their brothers and sisters as well as Biage. In Kovelo and Savaea young men and women were reported to use mostly Biage but also some Tok Pisin with their brothers and sisters, parents and grandparents.

In Kanga and Pelai, middle-aged and old men and women are reported to only use Biage with other people in the village. In Ebea, Kovelo and Isurava, middle-aged and old men and women are generally reported to use Biage with other people in the village with some exceptions. Middle-aged men in Ebea are said to use a little Tok Pisin and English with children as well as Biage. Middle-aged men in Isurava are reported to use a little Motu and Tok Pisin with children. In Kovelo, middle-aged and old people are all reported to use a little Tok Pisin with everyone in the village.

For young, middle-aged and old people in all Biage villages, Biage is always reported to be the dominant language when speaking to other people in the village.

7.1.4 Reported mixing

All villages in Biage reported that children mix some Tok Pisin with Biage. In Kovelo, Isurava and Pelai only a little mixing was reported. In Ebea children are said to mix a little Tok Pisin with Biage when they talk to adults and a lot of Tok Pisin when they talk to other children. In Kanga children are reported to mix a lot of Tok Pisin and also a little Motu and Fuyug with Biage. As well as mixing Tok Pisin, in Kovelo children also mix a little English with Biage and in Pelai children mix a little Kaina Ke, Ese and English with Biage. In Kanga, Ebea and Pelai people said children mix their languages due to intermarriage. In Kovelo people said that children mix their languages because they learn other languages at school. In Isurava people said children mix languages because they like other languages. In Pelai people said children hear other languages used elsewhere and then come back to the village and use it. In Kovelo, Isurava and Pelai adults said that they mix a little Tok Pisin and Motu with Biage. Adults in Ebea,

7.2 Observed language use

In Ebea, mostly Biage was overheard. A group of children aged five to ten were using Biage while playing rugby. In Savaea children aged six to ten were heard using Biage with each other. In Pelai only Biage was heard. It took people a long time to find a young girl who could speak Tok Pisin who could go with the female surveyors to wash. There were quite a number of children in the village at this point.

Children were heard using both Tok Pisin and Biage. One boy, aged around ten, used Biage to talk to younger children. He was also heard using Tok Pisin to talk about dogs fighting. Women and children looking at a photo on a digital camera were using Biage except for two Tok Pisin statements. A group of five children and young people, aged between five and fifteen were heard using Tok Pisin. A man, who is from Kanga and whose wife is from Kanga, was heard using both Tok Pisin and Biage to his child, about seven years old. A conversation between two girls, one pre-teen and one in her mid-teens, was mainly in Biage but a couple of Tok Pisin phrases were also heard. A group of children, aged under ten, were heard using Biage.

The survey team was unable to observe very much language use in Isurava and Kovelo due to a lack of people in the village at the time of the survey.

7.3 Perceived language vitality

When people were asked if their language was strong or not, everyone responded that it was strong. Opinions on what the future holds for Biage varied. People in Pelai and Isurava said their language would stay strong. People in Ebea and Kanga felt that intermarriage posed a danger for their language. People in Kovelo said that it would depend on whether their children had more schooling or not; they felt if their children had more schooling then their language would lose its vitality. No one would be happy if their language was lost. In Kanga people said if they lost their language they would lose their identity.

When asked what languages children would be speaking in twenty years time, people all listed Biage alongside either or both Tok Pisin and English. When asked if children in twenty years time would be speaking Biage or not, everywhere but Ebea said yes.

7.4 Bilingualism

Biage is the only language in which a large proportion of the population is proficient. Previously Motu was widely spoken, but now only the older people can speak it. Tok Pisin is becoming more widely known, with young men and women generally being reported as being proficient in it. Many older people either understand but do not speak Tok Pisin, or do not understand it. In Pelai old people can speak Kaina Ke, but the majority of middle-aged and younger people do not even understand it.

7.5 Language attitudes

7.5.1 As reported

During group interviews, people were asked: 1 When you hear variety X how do you feel?

2 If your children forgot your language and only spoke variety X how would you feel? 3 In what language do you currently read the Bible?26