ANALYSIS

Identification of development indicators in tropical

mountainous regions and some implications for natural

resource policy designs: an integrated community case study

J. Kammerbauer *, B. Cordoba, R. Escola´n, S. Flores, V. Ramirez, J. Zeledo´n

Department of Natural Resources and Conser6ation Biology,Pan-American Agricultural School,Zamorano,P.O.Box93, Tegucigalpa,Honduras

Received 8 September 1999; received in revised form 4 April 2000; accepted 30 May 2000

Abstract

In tropical and subtropical countries a social gradient can be observed in mountainous regions between small-scale farmers on fragile ecosystems associated with human poverty, and the fertile plains and broad valleys with large-scale cash crop productions and industrial centers associated with relative economic welfare. Sustainable community development paths have to be identified in these less privileged regions. The objective of this study was to make a contribution for defining and assessing development indicators at community level, including ecological, economic and social dimensions, to elicit the conflicting objectives in development and to discuss some practical implications. The study was performed in a typical watershed in central Honduras and special attention was given to au-tochthonous and qualitative indicators for development. Using the pressure-state-response model as a framework, a series of indicators were identified and assessed, which were also used by the local population and grouped into landscape structure, soil fertility, water availability and quality, production system and extractive activities, economic and social performance, and institutions. The development path in this specific case illustrated the transition from an expansive forest conversion agriculture to an intensified and diversified agriculture. This was made possible through technology transfer and improved market access. However, this development path, while increasing economic welfare, generated increasing negative environmental impacts caused by pesticide residues, soil erosion and less regular water supply. As the watershed carrying capacity for traditional shifting cultivation (used as asystemindicator) reached its ecological limit, new sustainable development strategies had to be identified. The implications of the study for policy design are that tools need to be provided for natural and environmental resource monitoring, which may consist of sustainability goal definitions, a minimal set of indicators and simple maps for planning land use at local level. © 2001 Elsevier Science B.V. All rights reserved.

www.elsevier.com/locate/ecolecon

* Corresponding author. Present address: Ecology Institute, Campus Universitario C. c27 Cota Cota, Casilla 10077, La Paz, Bolivia. Tel./fax: +591-2-797511.

E-mail address:[email protected] (J. Kammerbauer).

Keywords:Indicators; Sustainability; Rural development; Natural resources policies; Honduras

1. Introduction

The concept of sustainable development has been widely used as an organizing framework since the Brundtland commission (WCED, 1987) and the UN Conference on Environment and Development (UNCED) in Rio de Janeiro in 1992 promoted this leitmoti6 at an international level. The general idea refers to a broad range of devel-opment objectives for meeting basic human needs while maintaining the life support system for cur-rent and future generations. Following the defini-tion of sustainable development by Barbier (1987), there are three dimensions: ecological sus-tainability, economic feasibility and socio-political acceptability, which are in an interactive conflict-ing process. The general objective is to maximize these goals across the biological, economic and social systems thus generating trade-offs among them. As a powerful but often ambiguous concept within the broader ecological economic paradigm, sustainability has been criticized for only being useful at a conceptual level, not at an operational level (e.g. Redclift, 1987; Munro, 1995). As sus-tainability indicators are seen as necessary to put into effect the concept of sustainability and to introduce it to the policy-monitoring arena, a variety of efforts have been made in the past to develop indicators for sustainable development (Simon, 1997). Two mainstream approaches can be identified; the first being an analytical ap-proach in developing pressure-state-response pat-terns (OECD, 1994), and the second being a systemic approach in defining synthetic indicators. Pressure-state-response indicators have been de-veloped for the agricultural, forest, industrial and energy sectors, for instance, amongst others OECD, 1994; Montreal Process, 1995; Winograd, 1995; CDS, 1996. Whereas system analysis provide these indicators at a system level related to energy efficiency and material flux intensities like environmental space for service units, carry-ing capacities and ecological footprints (Ehrlich and Holdren, 1971; Schroll, 1994; Wackernagel and Rees, 1996).

Economic difficulties and lender pressure have obliged Latin American countries to implement structural adjustment programs, governmental de-centralization and market liberalization; govern-ment expenses were reduced and national markets were opened up to foreign imports, price subsidies were eliminated and many public enterprises pri-vatized. Currently, the liberalization of land and agricultural markets and decentralization, accom-panied by antipoverty and sector investment pro-grams, are dominating the rural development strategy. In many cases, impacts through these interventions on natural and environmental re-sources have not been monitored. Agricultural expansion for cash crops takes place mostly on fertile plains, as observed in most Latin American countries. This puts pressure on small-scale farm-ers to amplify the agricultural frontier in tropical forests and mountainous areas, where ecological, economic and social impacts on these fragile ecosystems are very likely to happen at a larger scale. In this way a social gradient is built up, with poor farmers having to bare additional envi-ronmental costs on less privileged lands.

(Altieri, 1995; Reardon and Vosti, 1995). Most decisions on natural resource management are made at farm or community level. To do so, a minimum set of criteria and indicators have to be defined for monitoring development paths in these fragile ecosystems. The objective of this study is to make a contribution in defining and assessing indicators at community level in a mountainous region, adopting ecological, economic and social dimensions, to elicit the conflicting objectives in development, and to discuss their practical impli-cations and the challenge to apply them at a wider scale. Some specific indicators used are described in detail in the case of land use change (Kammer-bauer and Ardo´n, 1999), pesticide residues (Kam-merbauer and Moncada, 1998) and land degradation and rehabilitation (Paniagua et al., 1999). Special attention is given to autochthonous indicators for a sustainable development. The re-sults obtained by this intensive study of a typical watershed for mountainous regions are briefly presented. Section 2 describes the site selection process and provides some information about the site studied. Section 3 provides a summary of the general conceptual framework for the indicator identification and the assessment steps, together with the study methods used. In Section 4 the indicators identified are presented and assessed. In Section 5 the community development paths and perspectives are discussed. Section 6 is comprised of some conclusions for policy design and moni-toring systems.

2. Site selection and description

The research was carried out during the period from 1994 to 1997. Site selection was developed by drawing on preliminary indicators of environ-mental degradation and community activity (Molina, 1994). The Yeguare river valley in the central region of Honduras comprises an area of about 276 km2containing 54 villages. Agricultural extensionists working in the area mapped the actual land used and assessed the extent of actu-ally observed environmental degradation and degradation risk. On the basis of these results, a selected grouping of villages was visited by the

research team who established a weighting matrix for environmental degradation and community activity for each village evaluated. The watershed of La Lima was finally selected for a detailed analysis of the causal relationships due to its high ranking index for potential environmental degra-dation and an above average index of community activity. The watershed is not representative in a statistical sense, but it is a typical region in Cen-tral America in terms of its hillside feature, its economic subsistence and its traditional social structure.

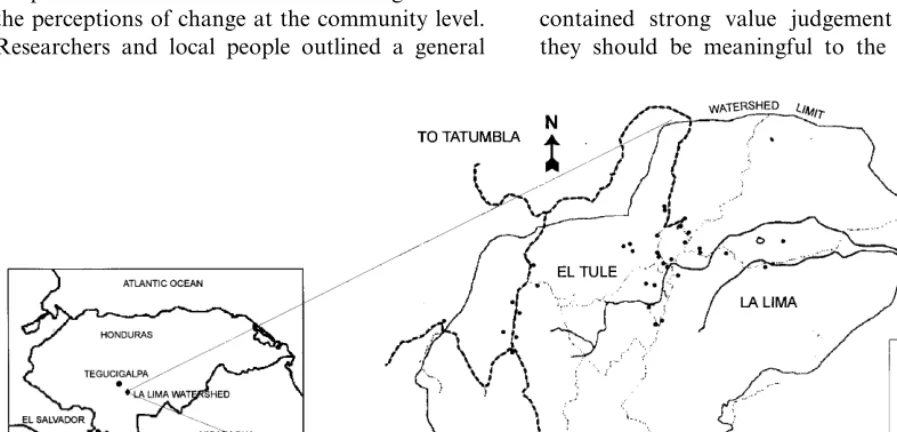

The La Lima watershed (87°25%W, 14°00%N) has an area of about 9.5 km2

and is located 17 km away from Tegucigalpa (Fig. 1). The altitude varies between 1200 and 1668 m above sea level with an annual precipitation ranging from 885 to 1182 mm, with a dry period normally spanning from November to April and a rainy season from May to October. The average temperature is 21.4°C, varying with the altitude, and the natural vegetation is largely pine forest up to about 1600 m, with broadleaf forest above this altitude; these are characterized by a high diversity of mosses (Bryophyta), lichens (Lichenes), bromeliads (Fam-ily Bromeliaceae) and orchids (Fam(Fam-ily Orchi-daceae). The watershed is characterized by a very irregular topographic structure with steep slopes at the borders and a plain area in the center, with permanent springs and creeks and lagoons in the plain. The principal La Lima community consists of a dense settlement of 62 family units as well as a more dispersed community in the surrounding area, comprising of 119 family units in total. Agricultural production consists in a traditional corn-bean system with fallow periods, and inten-sive production of potato, tomato, onions, and garlic.

3. Study methodology

3.1. Framework and limitations

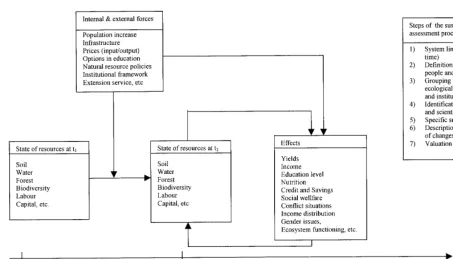

allocation of space for agriculture and forestry activities, and presents a certain barrier to human interactions. The general framework developed to identify indicators and assess the various method-ological steps to be taken is presented in Fig. 2. It is assumed that the conditions of the resources in a defined watershed change over space and time, influenced by driving internal and external forces that have some effects on the community state. Qualitative and quantitative indicators of the state of production factors and the environment can define the resource conditions. The changes in these conditions and their resulting effects on production, income, welfare and distribution define whether or not a development path in the watershed is more or less sustainable in ecologi-cal, economic and social terms. The study iden-tified and assessed indicators of landscape mosaic, soil fertility, water resources, as well as produc-tion systems and extractive activities, economic and social performance, and institutions, both of which were produced by the local population as well as by the researchers. The approach at-tempted to be sensitive to local knowledge and to the perceptions of change at the community level. Researchers and local people outlined a general

sustainable watershed vision considering the basic human needs and the maintenance of life support systems for current and future generations. Iden-tification and assessment of autochthonous indi-cators was achieved through intensive discussions on relevant issues related to community develop-ment. A consensus and feedback process between local people and researchers was reached through constant interviews with individuals, focal groups, and through community workshops. A sustain-ability vision was developed for each indicator during the research process. Indicators should reflect the concern of local people and describe relevant aspects of community development. It was difficult to determine quantitative targets, but the desired directions in which the indicators are expected to develop in the future, ecological, eco-nomic and social welfare of the community are to be improved, were defined. A further constraint was to establish safe minimum standards, with the exception of minimum space for shifting cultiva-tion, fire wood extraccultiva-tion, pesticide contamina-tion in drinking water and nutricontamina-tion status of children. The indicator definition and assessment contained strong value judgement elements, as they should be meaningful to the local

Fig. 2. Steps of the sustainability assessment procedure and indicator framework in the La Lima watershed.

tion, sensitive to changed management practices, but also valid from a scientific point of view. The concept of sustainability demands a holistic and intersectoral approach in order to show trade-offs among development tendencies. One tried to iden-tify the interrelations between the indicators by describing the overall tendencies in the develop-ment path of the watershed area.

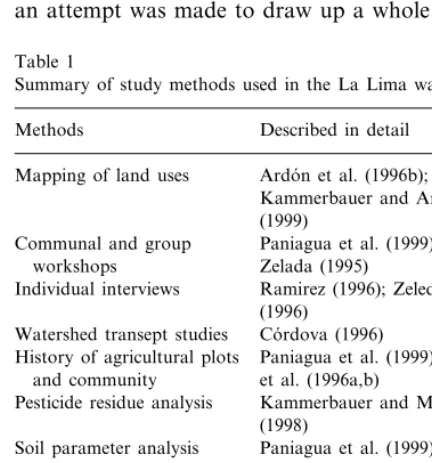

3.2. Methods

This intensive study was performed during the period from 1993 to 1997. A broad range of methods with emphasis in participatory ap-proaches have been used. These and laboratory methods are described in detail in the thematic studies mentioned in Table 1. Only a brief overview is given here. The research team was trained in participatory methods and interview techniques (Falck et al., 1996a,b). As this research had a substantial participatory component, vari-ous workshops were organized to allow interac-tion with the local farmers and elicit their

addi-tionally an agricultural census was performed (IF-PRI and EAP, 1995). The study period covered a period of about 20 years, from 1975 to 1995, and change of land use was assessed over a period of 40 years from 1955 to 1995 using aerial photographs.

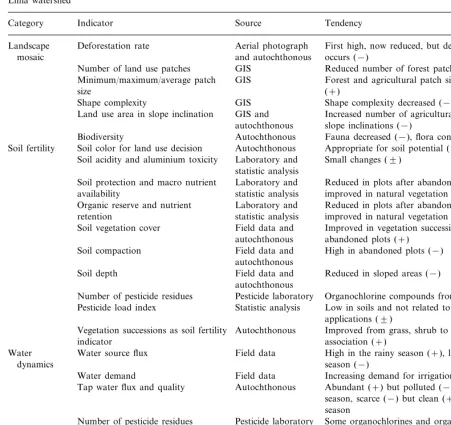

4. Results and discussion

During the research activities a variety of indi-cators appeared to evaluate if development pro-cesses move to sustainablity. The identified indicators relating to change of land use, soil degradation/rehabilitation, water availability and quality are shown in Table 2, and those relating to production systems, economic and social per-formance, and institutions are presented in Table 3. The main sources of information and the gen-eral tendency (towards sustainability or not) are given in comparison to the vision or target for each indicator, as defined by locals and re-searchers. The general framework of indicators is further described in Section 4. In Sections 5 and 6, an attempt was made to draw up a whole picture

of the multi-faceted development tendencies in the watershed and community, and to identify the implications of natural resource policy designs for mountainous regions.

4.1. Landscape mosaic

Spatial and temporal databases derived from aerial photographs and topographic maps have been used to assess the changes in land cover and landscape use patterns over a 40-year period using deforestation rates and landscape patterns as pro-cess indicators for ecological sustainability (Table 2). Land use dynamics and landscape change pat-tern are described in detail in Kammerbauer and Ardo´n (1999). There were clearly two distinct periods of land use development in the La Lima watershed, the first, 1955 – 1975, being an agricul-tural expansion phase with a deforestation rate of 1.2% per year. This consisted of occupying the space from the relative flat central area to the steep, more peripheral areas in the watershed until natural physical and ecological constraints were encountered, mainly slope inclination and thin soils. Forested areas were cleared and converted into agricultural areas, population increase and migration movement being the driving force for this change. The second period (1975 – 1995) can be considered a period of agricultural intensifica-tion and diversificaintensifica-tion, the driving forces consist-ing of technological transfers, access to agricultural extension services, improved access to local markets, subsidized agricultural input prices and limited private forest property rights due to forest regulations. Consequently, the deforesta-tion rate decreased to 0.6% per year, forest use was more extractive and dense forests were con-verted to sparser forest and forests with pasture; the demand for firewood being the main causative factor. Moreover, the landscape pattern changed, with the number of forest patches decreasing and their size increasing, which resulted in a lower shape complexity of the landscape, especially due to the relatively large and closed crop areas. This landscape pattern in combination with steep slopes was more prone to erosion and landslides, which subsequently occurred.

Table 1

Summary of study methods used in the La Lima watershed

Described in detail Methods

Mapping of land uses Ardo´n et al. (1996b); Kammerbauer and Ardo´n (1999)

Paniagua et al. (1999); Communal and group

workshops Zelada (1995)

Ramirez (1996); Zeledo´n Individual interviews

(1996) Watershed transept studies Co´rdova (1996)

History of agricultural plots Paniagua et al. (1999); Falck and community et al. (1996a,b)

Pesticide residue analysis Kammerbauer and Moncada (1998)

Paniagua et al. (1999); Soil parameter analysis

Zeledo´n (1996) Nutrition pattern and Flores (1996)

weight measures of children

Ardo´n et al. (1996a) Inventories of flora and

fauna

Table 2

Examples of indicators on land use change, soil characteristics and water availability and quality identified and assessed in the La Lima watersheda

Source

Category Indicator Tendency

Deforestation rate

Landscape Aerial photograph First high, now reduced, but deforestation still occurs (−)

and autochthonous mosaic

GIS

Number of land use patches Reduced number of forest patches (−) Minimum/maximum/average patch GIS Forest and agricultural patch sizes increased

(+) size

GIS

Shape complexity Shape complexity decreased (−)

Land use area in slope inclination GIS and Increased number of agricultural plots in great slope inclinations (−)

autochthonous Autochthonous

Biodiversity Fauna decreased (−), flora constant (9) Autochthonous

Soil fertility Soil color for land use decision Appropriate for soil potential (9) Laboratory and

Soil acidity and aluminium toxicity Small changes (9) statistic analysis

Soil protection and macro nutrient Laboratory and Reduced in plots after abandonment (−), improved in natural vegetation successions (+) statistic analysis

availability

Laboratory and Reduced in plots after abandonment (−), Organic reserve and nutrient

retention statistic analysis improved in natural vegetation successions (+) Field data and

Soil vegetation cover Improved in vegetation successions in abandoned plots (+)

autochthonous

Soil compaction Field data and High in abandoned plots (−) autochthonous

Field data and

Soil depth Reduced in sloped areas (−)

autochthonous

Pesticide laboratory Organochlorine compounds from past uses (9) Number of pesticide residues

Statistic analysis

Pesticide load index Low in soils and not related to current applications (9)

Vegetation successions as soil fertility Autochthonous Improved from grass, shrub to forest association (+)

indicator

Water source flux Field data High in the rainy season (+), low in dry Water

dynamics season (−)

Field data

Water demand Increasing demand for irrigation water (9) Autochthonous Abundant (+) but polluted (−) during rainy Tap water flux and quality

season, scarce (−) but clean (+) during dry season

Pesticide laboratory Some organochlorines and organophosphates Number of pesticide residues

(−)

Statistic analysis Low in dry season (9), higher in rainy season Pesticide load index

(−)

Autochthonous Limited access for irrigation (−), damages in Water use and management conflicts

the tube system (−)

aValuation results: (+) improving or positive in relation to the defined sustainablity target; (9) not changing or neutral; (−)

declining or negative.

Human intervention has to a certain extent produced a simpler mosaic landscape, although it remains highly complex with diversified land use types, totaling 18 land use categories mostly ma-nipulated by human activities. Many ecological phenomena are sensitive to spatial heterogeneity and fluxes of organisms, materials and energy

Table 3

Examples of indicators on production systems, economic and social performance and institutions identified and assessed in the La Lima watersheda

Indicator Tendency

Category Source

Autochthonous

Crop diversity High in traditional crop varieties and horticulture crops Production

(+) systems/extractive

activities

First increasing (+), now constant (9) Autochthonous

Production area

Yields Autochthonous Improved (+) though fertilizer and pesticide input (−) Organic soil Autochthonous and Low (−)

laboratory analysis enrichment

Home gardens Autochthonous High diversity (+), low production (−) Autochthonous Increased demand (−), increased distances for Forest

recollection (−) extractive

resources

Field data

Biodiversity Shannon–Wiener-index high in traditional agricultural

index plots (+)

Hunting Autochthonous Reduced offer of wild animals (−) resources

Autochthonous and Increased costs (−) with the elimination of subsidies Input prices

Economic and social

Centralbank performance

Output prices Autochthonous and Increased prices (+) with liberated market prices Centralbank

Labor costs Autochthonous Constant (9)

Autochthonous Increased number of plot experiments (+) New

production technologies

Nutrition status Field data Some subnutrition in children (−) Autochthonous

Diet Low diversified (−)

composition

Autochthonous

Access to Improved, less absenteeism (+) primary

education

Various actors in the past (+), now reduced (−) Autochthonous

Extension Institutions

service access

Property rights Autochthonous and Formally not defined (−), but customary rights (+) cadastral maps

Mediania contract as joint venture production and Contract Autochthonous

labor (+) system

Land markets Autochthonous Informal and easy access (+)

Access to credit Autochthonous Formally very low (−), bank guarantees not available (+), mainly informal (+)

Low (−), mainly for emergencies (+); not for Autochthonous

Savings

investments (−)

Improved to neighbor communities and city (+) Market access Autochthonous

Man in production (9), women in household with Field data

Management

decisions taking limited power over resources (−)

aValuation results: (+) improving or positive in relation to the defined sustainablity target; (9) not changing or neutral; (−)

now found less frequently. It is suspected that local water regulation is affected by less water retention in the watershed during the rainy sea-son, which has caused flood damage due to heavy rain in past years.

4.2. Soil fertility

As further shown in Table 2, a number of soil fertility indicators were identified, and farmers have their own system by which to classify the fertility and utility of soils. These perceived physi-cal and ecologiphysi-cal properties of the soils tend to dictate how farmers are to use the land. Colored soils are commonly considered suitable and used for agricultural and horticultural production, black soils being the most fertile. Pulverous soils are considered particularly appropriate for pota-toes, whilst gravely soil is only suitable for forest. In the central and lower part of the La Lima watershed with low slope inclinations, deeper and richer soils can be found, used extensively for horticultural production, whereas in the periph-eral zones with steeper inclinations one finds shal-lower, less fertile soils used for the traditional corn-bean production and are left mainly under forest. Individual plant species are used to indi-cate soil fertility, such as Sal6ia carwinsky, Sar -a6ia sp., Hibiscus tiliaceus, Pteridium aquilinum, and Veronica deppeana. Their presence in the agricultural plots indicate high or remaining soil fertility. The farmers try to enrich soils with crop residues and these are supposed to have major effects on efficiency in nutrient cycling. Neverthe-less, fertility declines after a certain number of production cycles and plots are abandoned.

In addition, vegetation succession stages are used as indicators for soil status, both for its degree of degradation and rehabilitation after plot abandonment. Five vegetation-types were identified:

two different grass associations jaragua´ grass and gramagrass,

a grass-shrub association montecillo,

a shrub association guamil and finally,

a secondary mixed forest.

Peasants classified jaragua´grass plots as highly degraded,gramagrass as degraded land but with

some residual fertility, and guamil and montecillo plots as improved soils. Mixed forest plots were considered as the climax stage in the vegetation succession. Cluster analysis supported the link between vegetation stages and the respective soil characteristics (Paniagua et al., 1999). This system of determining the potential degree of fertility and infertility by vegetation successions appeared as a workable method of identification and it was sup-ported by physico-chemical analysis of the soils. The information derived from factor analysis al-lowed for the construction of simplified soil fertil-ity indicators for scientific purpose, capable of representing more complex physical and chemical data: soil acidity and aluminium toxicity index, soil protection and macro nutrient availability index and an organic reserve and nutrient reten-tion index.

4.3. Water dynamics

sig-nificantly more pesticides than in the drinking water. The pesticide residue patterns are, how-ever, only slightly related to the current pesticide application in use in these production systems and are due to past uses of organochlorine in agricul-ture and household sanitation. Nevertheless, downstream users may be affected by agrochemi-cals used in the La Lima watershed. Different kinds of management conflicts can be observed as water fluxes in the creeks are reduced during the dry period. Farmers compete for irrigation water for their horticulture plots, as clear rules for the assignments of irrigation water are not estab-lished. Further conflicts are reported in operation and maintenance of the potable water system and the fee collection arrangement for water use.

4.4. Production systems and extracti6e acti6ities

The indicators that have been drawn on pro-duction systems and extractive activities are shown in Table 3. The principal agricultural activ-ity is basic grain production for home consump-tion as well as horticultural producconsump-tion for the local Tegucigalpa market. Agricultural plot sizes vary, with 63% of the plots ranging between 0.1 and 1.5 ha. About 60% of the agricultural plots are under permanent cultivation, principally of corn, bean, potato, tomato, onions and garlic, which meet both subsistence and market needs. The traditional production system is an integrated corn-bean association on the hillsides on soils, characterized by medium to low nitrogen, low to high phosphorus, high potassium and low to medium organic matter contents. Different vari-eties of corn and bean are used at different alti-tudes above sea level. To mobilize nutrients, most plots are burned at the end of the dry season. Because of the loss in fertility, these plots are abandoned after approximately 5 years of produc-tion. Under the demographic and economic pres-sures, the shortened cycles of fallow for nutrient and soil regeneration are often not sufficient to maintain the productivity of this traditional sys-tem. Yields are low, compared with modern pro-duction systems, and major management problems include soil erosion and landslides at hillsides, the invasion of weeds and some

organochlorine residues in soil. However, from an ecological standpoint, the traditional cropping system favored a high plant biodiversity index (Shannon – Wiener) on the plots, which ranged from 0.82 to 0.91, with a low incidence of plagues on crops. Biodiversity is important since it affects biogeochemical processes, which themselves influ-ence soil nutrients, plant diseases and weed inva-sion. Further, farmers perceive the invasion by wild animals and the limited access to irrigation water as problematic. The intensive production pattern of horticultural cash crops for local mar-kets fosters a low biological diversity in the plain of the watershed, where labor, irrigation, fertilizer and pesticide inputs are relatively high. Animal production is of little importance and is mainly restricted to cattle ranching for traction purposes in plugging and transport, pigs and other minor animals for autoconsumption. Home gardens have been reported in 70% of households, with an average area of 400 m2, containing a high diver-sity of fruit trees (13 species), vegetables (seven species), tubercles (three species), medicinal plants (11 species) and ornamentals (28 species). In most cases the home gardens do not receive major management attention and it is reported that most products are used for home consumption. Additional economic activities include the produc-tion of coffee and some wild berries and fruit collected by women from shrubs and forest areas for home consumption, marmalade production and some local sale. These products enrich the basic bean and corn nutrition.

The main extractive activity in the forest is fire wood collection with a preference for oak and pine wood species to be used in the loam ovens. Fuel wood is the only energy source in the water-shed. Average extraction rate at watershed level is estimated in 1285 m3

total tree biomass growth above ground in the watershed of 1700 t/year. Assuming that only 50% of tree growth is available for fire wood, extrac-tion rate and growth rate are more or less at equilibrium, but obviously threatened when de-mand increases.

4.5. Economic and social performance

The local population uses different economic and social performance indicators. Special atten-tion was given to the tradiatten-tional corn-bean pro-duction system (Table 3). An economic analysis of these systems showed different results depending on the location in the watershed with an ex-tremely high variation in economic performance, depending on yields, fertilizer and labor inputs. With regards to the opportunity costs for labor paid on a contract basis in the region, production systems located in the mountainous areas had a negative return (−300%), while in the plain area, net utility return was positive (+200%). Exclud-ing labor opportunity costs, the net returns were positive in all cases, varying extensively from 18 to 600% depending on yields at the different locations. A major part of the production is used for home consumption while a minor part is commercialized in nearby communities. The in-tensive horticultural production systems generate a significant higher net return of 250% including opportunity costs for labor, and selling the pro-duce at the market places in Tegucigalpa has been the main source of monetary income.

Farmers’ strategies for improving economic performance consist in identifying improved pro-duction systems. Farmers experiment with natural fertilizer, new crop varieties, seed selection, im-proved pasture and crop associations. It was re-ported that they establish small plots with these new technologies and make a comparative analy-sis in production results. For minimizing risks they only adopt these modified production sys-tems relatively slowly at a wider scale.

Since a major part of the production is con-sumed locally, which itself constitutes the major basis for nutrition, the nutrition status of children and the occurrence of child diseases were used as indicators for social performance. The nutrition

pattern of the community varied little throughout the year and consisted mainly of bean and corn products, with animal products being scarcely available and limited to milk and eggs for the children’s nutrition. One can assume that carbo-hydrates are abundant in this type of nutrition, but protein deficiencies have been observed. Min-erals and vitamins are provided in fruits through-out the year. In order to assess the state of nutrition of the community, the children’s weight and age was determined and compared with com-monly used normal distribution in clinical health monitoring. A total of 59% of the children as-sessed were of normal weight for their age, whereas 41% were underweight in the average range of 15%, probably due to deficiencies in the diet composition. The most frequently reported child diseases were respiratory problems due to smoke from the loam ovens and the housing conditions. These social indicators, with others show that although economic welfare increased to some extent, the social conditions did not reach optimal levels.

4.6. Institutions

environmental impact. Living conditions im-proved significantly at community level with a positive feedback on access for education, trans-port and some higher, but still limited investments in natural resources management (e.g. erosion control, irrigation system, storage capacities). Limiting factors for increased production are the physical environment (slopes, soils, water, etc.), limited access to credit and saving capacities for investments. As land is not formally titled, guar-antees for bank credits are rarely available.

A special organization form of production is the mediania, a production joint venture among two or more farmers in which one, for example, provides land and the other labor and materials and final yield is divided among them. A variety of shared arrangements among them are observed and it is a strategy to overcome restraints in capital, especially to purchase fertilizers and pesti-cides. Farmers with access to land, but with lim-ited financial resources or time to manage it, provide plots through verbal contracts to others who have limited or no access to land, which generates additional income for both of them. The mediania system provides a more efficient alloca-tion of limited producalloca-tion factors in the water-shed and results in a fairer distribution of welfare among households.

In general it is recognized that rural women play an important role in the development pro-cess; yet women remain marginalized, and are the most affected by poverty. In the La Lima case women do not take an active role in the agricul-tural production process, and they seem to have little influence on decisions on natural resource management, although 43% of the women are owners of agricultural plots. They are involved in a very low degree of decision making regarding food production; whereas men make 93% of deci-sions, women only make 5%. However, decisions relating to nutrition and clothing are made at equal parts (42%) by women or men, or by both (16%), and only decisions related to health aspects are taken quasi exclusively by women (93%). De-cisions about savings are taken 58% by men, 21% by women and 21% by both. Obviously, women perform their tasks under considerable con-straints, with limited access to resources,

technol-ogy, education, and training; as it is reported that only 26% of the women are realizing some com-mercial activity, and 38% are illiterate. Also, deci-sions at community level are taken nearly exclusively by men in community-based organiza-tions (patronato, water committee, production committee, padres de familia), where women are scarcely represented.

5. Development paths and perspectives

Development paths are associated both with positive and negative impacts on environment and society. The indicators can be seen as a manage-rial tool in order to assess the overall performance of a defined watershed, including trade-offs among different development strategies. The strat-egy in identifying indicators for rural communities at mountainous regions from a bottom-up per-spective seems to be relevant for guiding to more sustainable development. A further step would be to normalize them in order to make them com-parable to each other. In this case it was proposed to use indices with a different weight for each indicator variable. As there was a lack of histori-cal data, one can only give an estimation of the general development tendencies from an ecosys-tem and inter-sectoral view as shown in Fig. 3. This overview tries to summarize the overall ten-dencies of the indicators in a qualitative way and to visualize the general development tendencies, where thresholds of irreversible environmental changes and extreme poverty present the under boundary, and an undisturbed natural environ-ment with economic and social welfare the upper limit of development. This interpretation and syn-thesis was reached through a consensus process by the local population and the researchers in a community workshop.

Fig. 3. The estimated development path of the La Lima watershed from 1955 to 1995.

1955, the available space for the traditional shift-ing cultivation was already too limited to allow a sufficiently long fallow period to naturally reestablish soil fertility. In 1975 there occurred an intensification of traditional agriculture, a diver-sification of horticultural production and access to irrigation water thus overcoming the aforemen-tioned constraint, but with a higher environmen-tal risk by pesticide residues (Kammerbauer and Moncada, 1998) and fertility loss. The pressure to turn forest areas into agricultural plots was re-duced significantly. Instead, the demand for fire-wood was the main reason for cryptical deforestation reducing tree density and there is some evidence that the estimated extraction rate tended to reach and exceed availability of fire-wood. Nevertheless, this development path per-mitted the watershed to support a rise in the population without impoverishment of local resi-dents; in contrast it increased total welfare in the watershed with better access for water, education, health service and some monetary income for

inversion and consumption, although indicators on nutrition status and diseases of children reveal some deficiencies in social performance.

special attention. Harwood (1996) and Altieri (1995) point out that there exists an extremely broad range of agricultural and agroforestry land-use alternatives in the tropics, but much work still needs to be done to increase productivity and sustainability. For example, a study carried out in Honduras by Mausolff and Farber (1995) showed that ecological farming is a promising practice to lower production costs with less environmental impacts while reaching similar yields as in inten-sive farming. Structured diversity is thus impor-tant where resources are highly limited in space, soils are of low nutrient-holding capacities and on slopes. Within this context the home garden should receive more attention, as gardens are highly complex and provide options to improve nutrition patterns and to avoid malnutrition in children. A further important issue is the energy question as it has a major impact on forest densi-ties; examples like improved energy efficient ovens and firewood plantations should be considered as alternatives. Regular water supply will depend on the preservation of forest area in the water catch-ment zone, depending on the developcatch-ment of communal land use plans. Main conflicting situa-tions which have to be resolved are water use rights and water management issues in the water-shed. In the study case, women play a minor role in decisions related to natural resource manage-ment issues. As a consequence, their economic and social position in the local society has to be fortified by rural development measures, training and investment programs.

6. Conclusions

Relationships among population, technology and resources are critical in agricultural change, with implications for food production, nutrition, health, economic development and sustainablity. As shown in the La Lima case, the natural re-source management structure has been successful in producing improved yields and a diversified production pattern, but less successful in main-taining the environmental quality and services. Farmers use a variety of indicators related to the sustainable use of land, soil fertility, water

availability and quality, production systems, eco-nomic and social performance and institutions, which can be completed by more scientific analy-sis. Better monitoring of status and changes of natural resources, as well as economic and social performance of national policies will be needed at local level. Development projects need to improve capabilities in local administration and promote instruments for local land use planning and natu-ral resource monitoring. This means that tools have to be provided which allow one to determine sustainability goals, as well as a minimal set of indicators and simple land use maps which should be used at community or municipality level and actualized on a regular basis.

There is a major need for participative scientific research in studying these natural resource sus-tainability issues in tropical and subtropical coun-tries, and mechanisms for financing have to be found (Kammerbauer, 1996). As in mountainous regions, there is a strict relationship between up-stream and down-up-stream watershed settlement mechanisms, which have to be found to compen-sate the first in order to maintain a functioning ecological system. The overall sustainability de-pends both on the adaptability of its various farms and enterprises and on the overall balance of ecosystem types in its landscape (Barrett, 1992). It is hoped that some lessons can be learned from the present micro-scale case study, and also from the well-known catastrophic hurri-cane event which took place in 1998 in Honduras, both showing the strong connectivity on the envi-ronmental systems and their functions and ser-vices among regions. Current trends in resource use intensification in mountainous environments require a more sophisticated monitoring approach and natural resource policies have to consider a more integrated and intersectoral vision.

Acknowledgements

The authors express their gratitude to the La Lima community in Honduras for their intensive collaboration and hospitality, Edwin Gomez for comments and suggestions regarding this manuscript and the US-Agency for International Development (SANREM CRSP, Grant No. LAG-4198-A-00-2017-00), the International De-velopment Research Center, Canada (Grant No. 93-0030) and the Swedish International Develop-ment Agency (IAEA-FAO Grant No. 7922) for financing the research. Additionally, for very helpful review comments we thank Dr. Sandrine Simon, Keele University, UK, and two anony-mous referees.

References

Altieri, M.A., 1995. Agroecology: The Science of Sustainable Agriculture. Westview Press, Boulder, CO, USA.

Ardo´n, M., Hoppert, J.C., Thorn, P., Cordoba, B., 1996. Conocimiento local de la flora y fauna en la microcuenca de la Lima, Tatumbla, Fco. Moraza´n, Honduras. Proyecto de Cartografı´a de Recursos Comunitarios e investigacio´n de Polı´ticas. Serie Documentos Te´cnicos No. 3, Escuela Agrı´cola Panamericana, Zamorano, Honduras.

Ardo´n, M., Ardo´n, C., Hoppert, J.C., Falck, M., Kammer-bauer, J., 1996. Dinamica de manejo del espacio en la microcuenca de la Lima. Proyecto de Cartografı´a de Re-cursos Comunitarios e Investigacio´n de Polı´ticas. Serie Documentos Te´cnicos No. 2, Escuela Agrı´cola Panameri-cana, Zamorano, Honduras.

Berkes, F., Folke, C., 1994. Investing in cultural capital for sustainable use of natural capital. In: Jansson, A.M., Ham-mer, M., Folke, C., Constanza, R. (Eds.), Investing in Natural Capital: the Ecological Economics Approach to Sustainability. Island Press, Washington, DC, USA. Barbier, E.B., 1987. The concept of sustainable economic

development. Environ. Conserv. 14, 101 – 110.

Barrett, G.W., 1992. Landscape ecology: designing sustainable agricultural landscapes. J. Sustainable Agric. 2, 83 – 103. Co´rdova, B., 1996. Utilizacio´n de especies silvestres en la

comunidad de La Lima. Proyecto de Cartografı´a de Recur-sos Comunitarios e investigacio´n de Polı´ticas. Serie Re-su´menes de Tesis No. 12, Centro de Ana´lisis de Polı´ticas Agrı´colas y Ambientales, Escuela Agrı´cola Panamericana, Zamorano, Honduras.

CDS, Commission on Sustainable Development of the United Nations, 1996. Indicators of sustainable development framework and methodologies, New York, USA. Ehrlich, P.R., Holdren, J.P., 1971. Impact of population

growth. Science 171, 1212 – 1217.

Falck, M., 1995. Desarrollo sostenible en la agricultura de Honduras: retos para los decisores de polı´ticas. In: De-sarrollo agrı´cola, sostenibilidad y alivio de la pobreza en Ame´rica Latina: el papel de las regiones de laderas. Semi-nario DSE/IFPRI/IICA/UPSA del 4 al 8 de diciembre de 1995, Tegucigalpa, Honduras.

Falck, M., Kammerbauer, J., Hoppert, J.C. (Eds.), 1996. Seminario-taller de estrategias de investigacio´n participa-tivo. Proyecto de Cartografı´a de Recursos Comunitarios e investigacio´n de Polı´ticas. Serie Documentos Te´cnicos No. 5, Escuela Agrı´cola Panamericana, Zamorano, Honduras. Falck, M., Kammerbauer, J., Ardo´n, M., Hoppert, J.C., 1996b. Mapeo de los recursos naturales y comunitarios en laderas: el caso de La Lima, Tatumbla. Proyecto de Car-tografı´a de Recursos Comunitarios e Investigacio´n de Po-lı´ticas. Serie Documentos Te´cnicos No. 6, Escuela Agrı´cola Panamericana, Zamorano, Honduras.

Flores, J.C., 1995. Caracterizacio´n del uso de agua en la comunidad de La Lima, Tatumbla. Tesis de Ingeniero Agro´nomo. Escuela Agrı´cola Panamericana, Zamorano, Honduras.

Harwood, R.R., 1996. Development pathways toward sustain-able systems following slash-and-burn. Agric. Ecosyst. En-viron. 58, 75 – 86.

IICA, Instituto Interamericana de Investigacio´n Agropecuaria, 1994. Perfil sectorial agropecuario de Honduras. Tegu-cigalpa, Honduras.

IFPRI, International Food Policy Research Institute, EAP, Escuela Agrı´cola Panamericana, 1995. Census of La Lima. Tegucigalpa, Honduras, unpublished.

Kammerbauer, J., 1996. Research in sustainable natural re-source management: the case of Honduras. In: Preuss, H.J. (Ed.), Agricultural Research and Sustainable Management of Natural Resources, Zentrum fu¨r regionale Entwick-lungsforschung der Justus-Liebig-Universita¨t Giessen, Schriften 66. LIT Verlag, Mu¨nster-Hamburg, pp. 85 – 96. Kammerbauer, J., Ardo´n, C., 1999. Land use dynamics and

landscape change pattern in a typical watershed in the hillside region of central Honduras. Agric. Ecosyst. Envi-ron. 75, 903 – 1000.

Kammerbauer, J., Moncada, J., 1998. Pesticide residue assess-ment in three selected agricultural production systems in the Choluteca River Basin of Honduras. Environ. Poll. 103, 171 – 181.

Mausolff, C., Farber, S., 1995. An economic analysis of ecological agricultural technologies among peasant farmers in Honduras. Ecol. Econ. 12, 237 – 248.

Molina, J., 1994. Processo de seleccio´n y caracterizacio´n de sitios para el estudio del impacto de politicas en los recursos naturales. Serie Resu´menes de Tesis No. 12, Cen-tro de Ana´lisis de Polı´ticas Agrı´colas y Ambientales, Es-cuela Agrı´cola Panamericana, Zamorano, Honduras. Montreal Process, 1995. Criteria and indicators for the

conser-vation and sustainable management of temperate and bo-real forests. Proceedings of the Montreal Process, Canadian Forest Service, Natural Resources Canada, San-tiago, Chile, Ottawa/Hull.

Munro, D., 1995. Sustainability: rhetoric or reality? In: Trzyna, T.C., Osborn, J.K. (Eds.), A Sustainable World: Defining and Measuring Sustainable Development. IUCN, Sacramento, USA.

OECD, 1994. OECD core set of indicator for environmental performance. Environmental Monographs 83, Paris, France.

Paniagua, A., Kammerbauer, J., Avedillo, M., Andrews, M., 1999. Relationship of soil characteristics to vegetation successions on a sequence of degraded rehabilitated soils in Honduras. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 72, 215 – 225. Pickett, S.T.A., Cadenasso, M.L., 1995. Landsape ecology:

spatial heterogeneity in ecological systems. Science 269, 331 – 334.

Ramirez, V., 1996. Caracterizacio´n de los huertos familiares de La Lima. Serie Resu´menes de Tesis No. 14, Centro de Ana´lisis de Polı´ticas Agrı´colas y Ambientales, Escuela Agrı´cola Panamericana, Zamorano, Honduras.

Reardon, T., Vosti, S., 1995. Links between rural poverty and the environment in developing countries: asset categories and investment poverty. World Dev. 23, 1495 – 1506. Redclift, M., 1987. Sustainable Development: Exploring the

Contradictions. Methuen, London. Simon, S., 1997.

Schroll, H., 1994. Energy flow and ecological sustainability in Danish agriculture. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 51, 301 – 310.

Tilman, D., May, R., Novak, M., 1994. Habitat destruction and the extinction debt. Nature 371, 65 – 66.

Wackernagel, M., Rees, W., 1996. Our Ecological Footprint. Reducing Human Impact on the Earth. Gabriola Island, BC and Philadelphia, PA.

WCED, The World Commission on Environment and Devel-opment, 1987. Our Common Future. Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Winograd, M., 1995. Indicadores ambientales para Lati-noamerica y El Caribe: Hacia la sustentabilidad en el uso de la Tierra. San Jose´, Costa Rica.

Zelada, M.A., 1995. Impacto de las polı´ticas de la moderniza-cio´n agrı´cola en el sector rural. El caso de la comunidad de la Lima, Tatumbala. F.M. Serie Resumenes de Tesis No. 5, Centro de Ana´lisis de Polı´ticas Agrı´colas y Ambientales, Zamorano, Honduras.

Zeledo´n, J., 1996. Caracterizacio´n del sistema de labranza mediante el uso de indicadores de sostenibilidad en La Lima, Tatumbla. Serie Resu´menes de Tesis No. 11, Centro de Ana´lisis de Polı´ticas Agrı´colas y Ambientales, Escuela Agrı´cola Panamericana, Zamorano, Honduras.