Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:12

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Faculty Perceptions of Business Advisory Boards:

The Challenge for Effective Communication

Kelly M. Kilcrease

To cite this article: Kelly M. Kilcrease (2011) Faculty Perceptions of Business Advisory Boards: The Challenge for Effective Communication, Journal of Education for Business, 86:2, 78-83, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.480989

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.480989

Published online: 23 Dec 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 116

View related articles

CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.480989

Faculty Perceptions of Business Advisory Boards:

The Challenge for Effective Communication

Kelly M. Kilcrease

University of New Hampshire at Manchester, Manchester, New Hampshire, USA

The author surveyed over 1,600 business faculty from 395 AACSB-accredited schools to as-certain their opinions about business advisory boards. The findings reveal that vast majorities of faculty were not directly involved with their business advisory boards, but they received updates through documentation and administrative feedback. Most felt, however, the informa-tion provided was deficient in substance and depth. Consequently, faculty who did not attend board meetings saw the contributions and importance of boards as being less significant than did those faculty who attended the meetings. The author presents the results in relation to 6 specific disciplines and from previous studies.

Keywords: advisory boards, effectiveness, participation

INTRODUCTION

Business advisory boards at American colleges have become common because of the need to maintain a competitive ad-vantage and for some schools to contribute to the accredita-tion standards set by the Associaaccredita-tion to Advance of Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). The termbusiness advisory board can mean many things in relation to the representa-tion within a college. For example, an advisory board can represent an entire school of business, a department, a spe-cific discipline, or an on-campus business institute. Board members come from both profit and nonprofit environments and are typically representative of upper management. Con-sequently, the broad purpose of the board is the utilization of their experiences to address strategy and planning within specific academic areas of the institution. Although the sug-gestions of a business advisory board impact many within the institution, business faculty have the greatest impact, as boards give significant guidance in curriculum changes and program development. Information about how well advisory boards complete this task is limited. As more business pro-grams are adopting advisory boards, the question proposed is, how do faculty view board effectiveness in impacting business departments?

Correspondence should be addressed to Kelly M. Kilcrease, PhD, University of New Hampshire at Manchester, Department of Business, 400 Commercial Street, Manchester, NH 03101–1113, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

CURRICULUM REVIEW

Past research guides institutions when creating and main-taining successful advisory boards. For example, Dorazio (1996) concluded that the effectiveness of department advi-sory boards was contingent upon two-way communication between board members and faculty. Conroy, Lefever, and Withiam (1996) focused on the importance of the size of the board, its member composition, and the meeting schedule as it related to hotel administration departments. Parvati-yar and Sheth (2000) showed that effective governance of marketing department advisory boards required a strong re-lationship between college personnel and board members. Andrus and Martin (2001) demonstrated that business ad-visory boards must have the commitment and support of faculty in order to be effective. Olson (2002) offered sug-gestions regarding board authority, and indicated that boards need to recognize that some of their suggestions may have little value or opportunity of being implemented within the business department. Boorom et al. (2003) found that a mar-keting department board’s most important task was address-ing the skills needed by students to be competitive upon graduation. Flynn (2002) showed that in order to be valuable to business departments advisory boards must be formally structured. Coe (2008) verified that a proactive advisory board in an engineering department is one that has an im-pact on students, curriculum, faculty, accreditation, and the community.

The opinions of business administrators have focused on the work activities of advisory boards. Fogg and Schwartz

FACULTY PERCEPTIONS 79

(1985) produced the only research that addressed adminis-trators’ perceptions about the quality of output produced by boards. They found that boards produced four effective out-puts: public relations (M =4.33), fundraising (M =3.62), curriculum review (M =3.49), and alumni relations (M =

3.49). Coco and Kaupins (2002) surveyed business school administrators from AACSB-accredited colleges and found that the four most important tasks boards engage in are ad-dressing curriculum development issues, suggesting ideas for new business programs, providing business department publicity, and developing an organizational mission. Baker, Karcher, and Tyson (2007) surveyed the chairs from AACSB accounting departments and found that curriculum review, strategic planning, and provision of internship opportuni-ties for students were the most important activiopportuni-ties of the board.

The only opinion regarding faculty perceptions came from Kress and Wedell (1993), who examined the opinions of mar-keting faculty in context to the quality of outputs produced by boards. Those surveyed believed that the four greatest out-puts produced by advisory boards were supporting fundrais-ing, providing internships, providing project opportunities for students and faculty, and presenting present marketing trends for faculty use.

The literature review shows there are no contemporary data on the perceptions of faculty regarding business advi-sory boards. Consequently, I surveyed business faculty to ascertain their opinions about communication, effectiveness, membership, and overall importance to the academic pro-gram. These opinions were then calculated for specific dis-ciplines and for two distinct levels of faculty involvement with boards. Finally, a number of comparisons were made using both these opinions and results derived from prior studies.

METHOD

Faculty who were tenured or tenure track (including ment and division chairs) in undergraduate business depart-ments at 395 U.S. AACSB-accredited colleges received an e-mail containing an invitation to complete a questionnaire. The questionnaire took approximately 5 min to complete through an online commercial web site that hosted and tab-ulated the results. Not all of the AACSB-listed schools par-ticipated, as 27 did not allow access to faculty e-mail and 44 were graduate schools only. A total of 10,853 surveys were forwarded, with 1,642 completed, delivering a response rate of 15%. On average, each of the 395 AACSB colleges re-ceived 27 questionnaires. The faculty, chosen at random, represented the general areas of accounting, economics, fi-nance, information technology, management, and marketing. The selected faculty completed the questionnaire on the one advisory board (based on a specific department, division, or school of business) that had the most direct representation

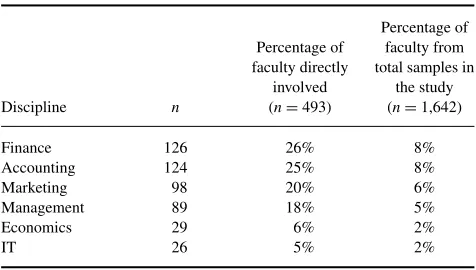

TABLE 1

Disciplines Where Faculty are Directly Involved With Business Advisory Boards

Finance 126 26% 8%

Accounting 124 25% 8%

Marketing 98 20% 6%

Management 89 18% 5%

Economics 29 6% 2%

IT 26 5% 2%

for them in terms of teaching and research. Of the question-naires completed, management had the greatest representa-tion (26%) followed by accounting (20%), marketing (21%), finance (13%), economics (11%), and information technol-ogy (9%). In terms of faculty rank, full professors completed most of the surveys (49%), followed by associate professors (34%) and assistant professors (17%).

RESULTS

Characteristics of Advisory Board Participation

A total of 30% of faculty (n = 493) indicated they were directly involved (attended the meetings) in their representa-tive advisory board, whereas 70% (n=1,149) indicated they had no direct involvement. Table 1 shows that the disciplines of finance and accounting had the greatest faculty represen-tation of the 30% directly involved with advisory boards. When applied to the entire study sample, the involvement by faculty was minute.

For those faculty with direct board participation, the most frequent capacity was as a faculty representative (67%). These individuals had various titles (e.g., faculty advisor, faculty liaison), were required to attend every meeting, con-tributed to issues for discussion, and had voting authority. The remaining faculty (33%) participated as part of their ad-ministrative task requirement. This included responsibilities related to the positions of division chair, department head, program coordinator, or director of an on-campus institute. Many of these representatives were responsible for estab-lishing meeting dates, organizing the agendas, and generally running the meetings.

Of the faculty who did not directly participate in their advisory board, 60% received no information on the activities of the board (this represented 42 percent of all faculty who participated in the study). Table 2 shows that the disciplines of information technology, finance, and economics were most deficient in knowledge on board activities.

TABLE 2

Disciplines Where Faculty Received No Information on Business Advisory Board Activities

Discipline n

Finance 103 91% 94%

Economics 163 86% 90%

Accounting 209 82% 87%

Marketing 244 79% 85%

Management 328 72% 80%

The remaining 40% of faculty who did not directly par-ticipate were aware of the decisions of their board (this rep-resented 28% of the total faculty who completed the sur-vey). They acquired information most commonly through communication with administration (47%). Deans or depart-ment chairs gave this information at departdepart-ment meetings dispersed among other agenda items. The second and third most common ways were by faculty receiving the minutes and memos of board meetings (42%) and by acquiring infor-mation informally (11%). The latter included conversations with faculty who attended board meetings and with those who had no association with the board.

At the same time, of those faculty who did not directly participate but were aware of the decisions of their board, 64% (or 11% of the total faculty who completed the survey) preferred to have even more information than was provided in one of the previous three ways. Indeed, many commented that the secondary communication concerning board activities

was often too brief and lacked depth and specificity regarding the actions of the board. One respondent stated,

We receive minutes from the board meetings and this does give us an overview of the board’s work, but the minutes are typically no more than one page long and offer no way for us to get clarification concerning questions we might have.

In summary, over half of all faculty who participated in this study either received no information about the activities of their advisory board or received inadequate postmeeting communications.

Effectiveness of Advisory Boards

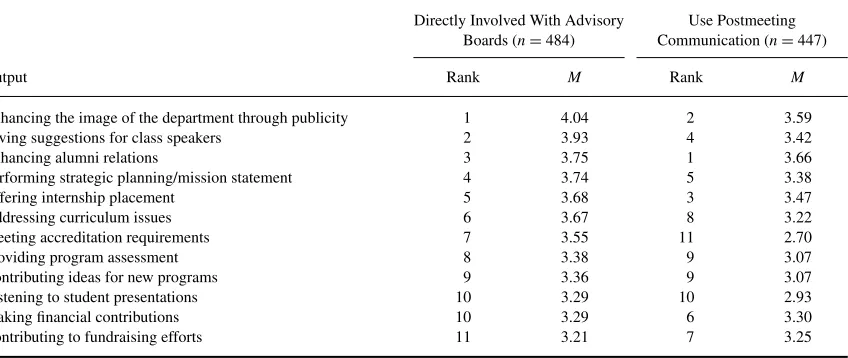

Faculty who either attended the meetings or acquired up-dates through postmeeting communications rated on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1(least effective) to 5 (most effective) how successful their business advisory board was in producing specific outputs. Although not everyone answered the question, Table 3 indicates that faculty directly involved with advisory boards and those who used post-meeting communication differed in output ratings of their boards—most significantly in contributing to fundraising, making financial contributions, and meeting accreditation requirements. The remaining differences in faculty percep-tions of board contribupercep-tions were no greater than two ranking spaces. The means for faculty who used postmeeting commu-nications, however, were noticeably smaller for each of the outputs and for the grand mean (x), as compared with faculty

who were directly involved in advisory boards. Relative to grand mean, attest revealed that there was a statistical signif-icant difference between the two faculty groups (p<.05, two

tailed). Thus, those faculty who received their board infor-mation through postmeeting communications did not believe

TABLE 3

Faculty Perceptions on the Contributions of Business Advisory Boards

Directly Involved With Advisory Boards (n=484)

Use Postmeeting Communication (n=447)

Output Rank M Rank M

Enhancing the image of the department through publicity 1 4.04 2 3.59

Giving suggestions for class speakers 2 3.93 4 3.42

Enhancing alumni relations 3 3.75 1 3.66

Performing strategic planning/mission statement 4 3.74 5 3.38

Offering internship placement 5 3.68 3 3.47

Addressing curriculum issues 6 3.67 8 3.22

Meeting accreditation requirements 7 3.55 11 2.70

Providing program assessment 8 3.38 9 3.07

Contributing ideas for new programs 9 3.36 9 3.07

Listening to student presentations 10 3.29 10 2.93

Making financial contributions 10 3.29 6 3.30

Contributing to fundraising efforts 11 3.21 7 3.25

Note.Based on the grand meanpbetween the two groups of faculty=.009. For Directly Involved With Advisory Boards,SD=0.26, grandM=3.57. For Use Postmeeting Communication,SD=0.27, grandM=3.25.

FACULTY PERCEPTIONS 81

advisory boards contributed to business departments as well as those who were directly involved with board activities.

A comparison of both sets of faculty from Table 3 to the Fogg and Schwartz (1985) administrative perceptions study shows a difference in similarities for the top four contribu-tions of business advisory boards. Public relacontribu-tions for the program and enhancing alumni relations were considered significant contributions by boards in both studies. Fogg and Schwartz, however, found that boards effectively contributed to fundraising and curriculum development, whereas Table 3 shows these variables in the latter half of the output rankings. Kress and Wedell’s (1993) research on marketing faculty opinions indicated that internship placement was the only similar board contribution ranked within the top third in this study, and this applied only to faculty who used postmeeting communications. Another difference is that Kress and Wedell identified board contributions of providing project opportu-nities for students and presenting current marketing trends for faculty use, whereas both faculty groups in this study did not identify these contributions as measurable output.

Finally, relative to administrator’s perceptions on the most important board activities, findings on Table 3 and in Coco and Kaupins (2002) and Baker et al. (2007) indicated quality differences. The only quality similarities that can be found between the past studies and Table 3 are department public-ity and strategic planning and developing an organizational mission (the latter only applies for faculty directly involved with boards). According to faculty in this study, the board was not effectively addressing curriculum issues and con-tributing ideas for new business program as they were other activities. In summation, fewer than half of all the work ac-tivity variables found in the reviewed past studies were found in the top third of Table 3.

Challenges of Advisory Boards

Faculty who were directly involved with their advisory boards and those who acquired updates through postmeeting communications collectively commented on the challenges that must be met to ensure the future success of their business advisory board (n=933). Whereas 53% believed there were no challenges, 47% identified a number of them. The most common challenge was a need for increased activity by the board toward meaningful work (30%). This included using the skills and knowledge that the board possessed to address important problems. One of the responses by a survey partic-ipant captured the involvement that faculty sought from the board:

The board needs something meaningful and concrete to do. Having projects within their range of capabilities is vital to the board’s success. They must be given assignments that have more importance than their work, as we are asking them to substitute our priorities for theirs.

At the same time, some of the institutions had a difficult time finding work that would be meaningful, as demonstrated by another comment from a survey participant:

It is difficult to find things that the board can do that makes the best use of their experience and expertise. We struggle with this constantly. We want them to feel useful and involved; at the same time, we do not want to take up too much of their time.

The second biggest challenge for boards, according to faculty, was increasing the business diversification of the board (27%). This change included better representation from smaller firms, nonprofits, middle management, and re-gions where the institution draws its students. For example, one survey participant stated, “A better diversification of our board would increase its overall effectiveness as it would allow for greater depth in perspective.”

The third biggest challenge was improving the relation-ship between the board and faculty (20%). This was espe-cially applicable in terms of getting to know the work and responsibilities of faculty and allowing more faculty mem-bers to express their ideas and comments at board meetings. Specific activities that faculty suggested to create a better relationship included having a moment in board meetings to present their research projects they are working on and hav-ing board members attend occasional class sessions to get a better idea of the characteristics of the programs.

Advisory Board Membership

Faculty who were directly involved with advisory boards and those who acquired updates through postmeeting communi-cations had opinions about board membership in terms of the college’s representation (n=922). Most believed that there was adequate alumni membership (85%) and faculty repre-sentation (67%) on the board. At the same time, only 30% of faculty felt there was enough student representation, and 39% of faculty stated they required no student representation on their board.

Importance of Advisory Boards

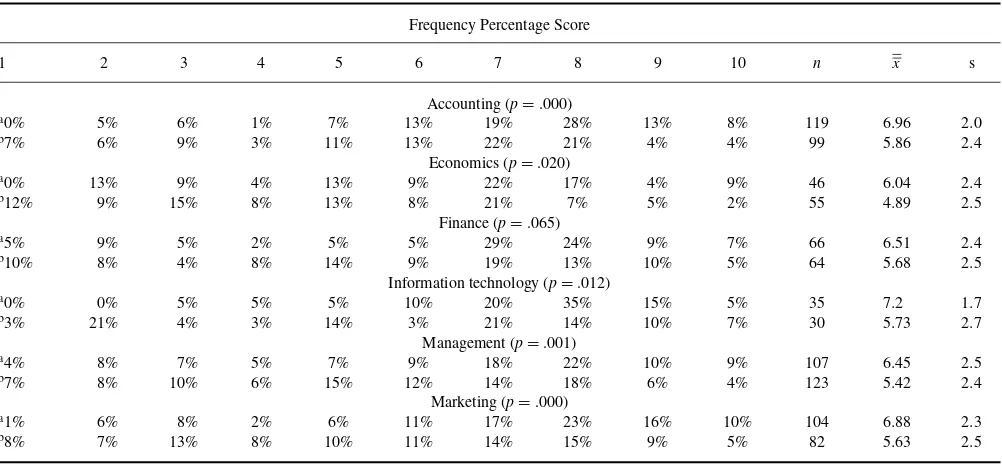

Faculty who were directly involved with advisory boards and faculty who relied upon postmeeting communications ranked on a 10-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (lowest importance) to 10 (highest importance) the impor-tance of business advisory board to the success of their department. A ztest determined any statistical differences between the two faculty groups. As displayed in Table 4, in every discipline except finance there were signifi-cant differences between the two faculty groups (p <.05,

two tailed). The statistical mean for those faculty who di-rectly participated in advisory boards ranged from 6.04 (economics [SD = 2.4]) to 7.25 (information technology [SD = 1.7]). For those faculty who used postmeeting

TABLE 4

Business Faculty Perceptions on the Importance of Advisory Boards

Frequency Percentage Score

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 n x s

Accounting (p=.000)

a0% 5% 6% 1% 7% 13% 19% 28% 13% 8% 119 6.96 2.0

b7% 6% 9% 3% 11% 13% 22% 21% 4% 4% 99 5.86 2.4

Economics (p=.020)

a0% 13% 9% 4% 13% 9% 22% 17% 4% 9% 46 6.04 2.4

b12% 9% 15% 8% 13% 8% 21% 7% 5% 2% 55 4.89 2.5

Finance (p=.065)

a5% 9% 5% 2% 5% 5% 29% 24% 9% 7% 66 6.51 2.4

b10% 8% 4% 8% 14% 9% 19% 13% 10% 5% 64 5

.68 2.5 Information technology (p=.012)

a0% 0% 5% 5% 5% 10% 20% 35% 15% 5% 35 7.2 1.7

b3% 21% 4% 3% 14% 3% 21% 14% 10% 7% 30 5.73 2.7

Management (p=.001)

a4% 8% 7% 5% 7% 9% 18% 22% 10% 9% 107 6.45 2.5

b7% 8% 10% 6% 15% 12% 14% 18% 6% 4% 123 5.42 2.4

Marketing (p=.000)

a1% 6% 8% 2% 6% 11% 17% 23% 16% 10% 104 6.88 2.3

b8% 7% 13% 8% 10% 11% 14% 15% 9% 5% 82 5.63 2.5

Note.For grand means between both groups,t=.000,p<.05, two tailedt-test. aFaculty who directly participated in advisory boards grandM=6.67.

bFaculty who used postmeeting communications to get their information grandM=5.53.

communications to get their board information, the mean ranged from 5.86 (accounting [SD = 2.5]) to 4.89 (eco-nomics [SD=2.4]).

Thus, with the exception of finance faculty, advisory boards were perceived as less important by faculty who re-ceived board information through postmeeting communica-tions, as compared with those faculty involved directly in board meetings. Further, the grand mean (x) score based on

the means for all disciplines showed highly significant sta-tistical differences (p<.05, two tailed), as those who were

directly involved with advisory boards had a grand mean of 6.67 and those who used postmeeting communications had a grand mean of 5.53.

CONCLUSIONS

Although 70% of business faculty did not participate in their advisory board meetings, they were satisfied with the number of faculty representatives. This means, however, they were dependent on post-meeting written and verbal communica-tion board activities. Unfortunately, many faculty received no information on their board’s activities, and, for those who received information, it may have been incomplete and inac-curate, and provided little opportunity for meaningful feed-back.

All faculty in this study believed that advisory boards were fair at best in their contribution and importance to business programs. At the same time, there was a considerable

differ-ence of opinion between those who were directly involved in business advisory boards and those who got their advi-sory board information from postmeeting communications. Those with direct involvement scored the contributions and perceptions of business advisory boards higher than those who used postmeeting communications. This suggests that faculty have to be present at board meetings in order to have a more positive perception of boards. This also reaffirms the perceptions of those faculty who believed that the postmeet-ing communications lack substance in expresspostmeet-ing the activi-ties of the board. Further, as supported by previous studies, business program administrators (who attend the meetings) believed that boards had a significant role in program and curriculum activities, whereas those faculty who received postmeeting communications did not see this relationship as clearly. Again, faculty who did not experience the activities of the board did not assess them as effective.

Consequently, there is a necessity for a more meaningful communication outlet. An easy solution to this problem is to require more detailed board meeting minutes, recognizing that this medium does not allow faculty to ask and receive answers for questions they have about board activities. For-mal department meetings would facilitate questioning, but, depending on the agenda, time could be an issue.

One solution that could address these information defi-ciencies is the implementation of an intranet site for business advisory boards. This site can provide continuous informa-tion for the faculty about issues related to mission, members, leadership, goals, strategy, and activities from prior meetings.

FACULTY PERCEPTIONS 83

More importantly, the site would serve as a communication tool for comments and questions to and from faculty and board members.

The context of the site would be enhanced if, once a year, a business representative from the advisory board would formally meet with interested business faculty to give an overview of board activities. Focused only on advisory board issues, this meeting could consist of a board member review of annual goals, the results of those goals, the future direction of the board, and answers to any questions from faculty or others attending. Naturally, these suggestions would increase the workload of the board, but, because boards typically have membership totaling in the teens, many members can take re-sponsibility for these communication efforts toward faculty. Regardless of the method used to increase the quality of the communication between the board and faculty, the depth and dissemination of the content of board meetings need greater consideration. If faculty do not clearly know what the board is doing, then both the faculty and the board lose the opportunity to make significant new contributions to the quality of the school’s business department.

REFERENCES

Andrus, D., & Matin, D. (2001). The development and management of a de-partment of marketing advisory council.Journal of Marketing Education, 23, 216–227.

Baker, R., Karcher, J., & Tyson, T. (2007). Accounting advisory boards: A survey of current and best practices. Advances in

Ac-counting Education: Teaching and Curriculum Innovations, 8, 77–

92.

Boorom, M., Chandler., W., Dudley, S., Marlow, N., Newstrom, N., Preton, S., & Wayland, J. (2003). Collaboration in course development: The role of business advisory boards in designing a professionalism course.MMA Fall Educators’ Conference Proceedings, 1–2.

Coco, M., & Kaupins, G. (2002). Administrator perceptions of business school advisory boards.Education,123, 351–358.

Coe, J. (2008). Engineering advisory boards: passive or proactive?Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice, January, 7–10.

Conroy, P., Lefever, M., & Withiam, G. (1996). The value of college advisory boards.Cornell Hotel and Restaurant Administration Quarterly,37(4), 85–89.

Dorazio, P. (1996). Professional advisory boards: fostering communication and collaboration between academic and industry.Business Communica-tion Quarterly,59, 98–105.

Flynn, P. (2002, November/December). Build the best BAC.Biz Ed, 41– 44.

Fogg, S., & Schwartz, B. (1985). Department of accounting advisory board: A method of communicating with business and professional community. Journal of Accounting Education,3(1), 179–184.

Kress, G., & Wedell, A.,(1993). Department councils: Bridging the gap between marketing academicians and marketing practitioners.Journal of Marketing Education,15(2), 13–20.

Olson, G. (2002). The importance of external advisory boards.Chronicle of Higher Education.54(24), C3.

Parvatiyar, A., & Sheth, J. (Eds.). (2000).The domain and conceptual foun-dations of relationship marketing. The handbook of relationship market-ing. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.