Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:15

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

MBA Attitudes Toward Business: What We Don't

Know Can Hurt Us or Help Us

William J. Lundstrom

To cite this article: William J. Lundstrom (2011) MBA Attitudes Toward Business: What We Don't Know Can Hurt Us or Help Us, Journal of Education for Business, 86:3, 178-185, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.496301

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2010.496301

Published online: 24 Feb 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 125

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2010.496301

MBA Attitudes Toward Business: What We Don’t

Know Can Hurt Us or Help Us

William J. Lundstrom

Cleveland State University, Cleveland, Ohio, USA

MBA students are often treated as a blank sheet of paper on which the MBA program and its fac-ulty etch and imprint the knowledge and philosophy of business success. Implicit in this think-ing is that students are willthink-ing neophytes in this ritualistic process without a perceptual screen shaping and molding the content being espoused by legions of business philosophers—both academic and professional. The author sheds light on the attitudinal states of the MBA stu-dents who occupy those many seats, engage in class discussions, analyze cases, and finally are knighted as Masters of the Universe. Quite surprisingly, MBA students have diverse attitudes toward the business community. In a sample of 866 MBA students representing 27 MBA pro-grams around the United States, the research suggests that these students do not embrace all aspects of business practices. Students are biased, skeptical and, on certain issues, downright critical of the community they are about to join.

Keywords: attitudes, business practices, MBA, students

As business academics and practitioners, researchers should be concerned with inputs (student achievement levels and attitudes), processes (program content and delivery), and outputs (quality of student knowledge and skills) of profes-sional, educational programs. If MBA programs were similar to manufacturing or service industries, each of these elements would be given equal emphasis in providing a quality prod-uct or service offering. Unfortunately, as the results of this research study suggest, much of the emphasis in MBA pro-grams focuses on the latter two—process and outputs. The vast majority of the research in the academic literature fo-cuses on the process and content of the program. The business press and institutional organizations examine outputs such as final GPA, placement, rankings, perceived quality of the pro-gram, recruiters’ evaluation of program graduates, and start-ing salaries among other measures of outcomes. This is not to say that input factors have been totally overlooked, but most input measures place an emphasis on predictors of program performance—undergraduate GPA, amount of work experi-ence, ethnicity, public or private education, undergraduate major, and GMAT scores.

Correspondence should be addressed to William J. Lundstrom, Cleve-land State University, Nance College of Business, 2121 Euclid Avenue, Cleveland, OH 44115, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

A key ingredient of any process-oriented organization (MBA programs included) needs to know about the qualities of the inputs into the process. Likewise, a customer-driven organization should, and would, know a great deal about its customer base, how and what they think, and the basis for their decisions. Without such knowledge, the manager (or program director) is simply putting together ingredients that may, or may not, lead to a quality, customer-satisfying prod-uct or service. Thus, insight into the attitudes and beliefs of the inputs (students) in the process provides a valuable and worthwhile first step in developing programmatic content that shapes the output in alignment with customer attitudes, or conversely, change attitudes that are out of alignment and a barrier to learning.

The research presented is an exploratory study. From my four decades of experience as a dean, graduate program direc-tor in several universities, service on many MBA admission committees, and involvement in redesigning MBA curricula, the consideration of the attitudes of the entering MBA stu-dent class never came into focus. Nor did the design of the program content and delivery ever take into account the atti-tudinal states of the MBA cohort. Interestingly, in a customer-driven model that is presented as the MBA program dogma, the thought of not considering customer attitudes toward the offering would be unheard of. The need to understand the client base (MBA students) to better offer program content that shapes more knowing managers in the future is simply

MBA ATTITUDES TOWARD BUSINESS 179

following the precepts that are preached. Therefore, this ex-ploratory study presents a first look at how MBAs think about business.

The purpose of the study is to uncover the attitudinal states of MBA students toward the business community and its practices. The study represents a first step in answering the questions: Who are these MBA students? What do these students think? What are the students’ attitudes about the subject they are studying? Do the students believe what we, the academics, are saying? What must be done to reinforce the students’ thinking? What must be done to change the students’ attitudinal state? Knowing the answers to some of these questions, faculty, administrators, and practitioners are in a position to develop curricula, change content of courses, and handle the questions that may arise in class due to a myriad of issues that are discussed regarding present topics.

RELATED LITERATURE

What Is Known

The literature on MBA education is replete with studies showing enrollment trends, curriculum issues, placement, starting salaries, ranking of programs, and demographic de-scriptors of test takers and enrollees in MBA program. An examination of some of the key items presents a picture of what is presently known about the MBA student and program content.

In the 2007–08 academic year, the Graduate Management Admissions Council (GMAC) administered a record number of 246,957 GMAT exams to over 97,000 women and 149,000 men (Graduate Management Admission Council, 2009a). Al-most one half of the test takers were citizens of other coun-tries, the largest proportion was in their late twenties, and minority populations are slowing growing as a percentage of all test takers. Enrollments in MBA programs have grown and are expected to further increase in the down economy. An overview of the studies sponsored by the GMAC in their summary of all research reports (Graduate Management Ad-mission Council, 2009b), shows research has been conducted on the GMAT exam, predicting success factors, validity stud-ies, understanding the value of graduate business education, brand image of MBA programs, and several reports on minor-ity groups and women. These and other research studies by Endres, Chowdhury, Frye, and Hurtubis (2008), Hsu, Chao, and James (2008), Truell, Zhao, Alexander and Hill (2006), and Sulaiman and Mohezar (2006) that examine success, effi-ciency, and satisfaction factors, although informative, tend to be more process- and output-oriented rather than examining the dimensionality and psychological characteristics (other than demographic) of the student input.

Process issues that surface through an examination of the literature tend to focus on three major variables (a) overall program content, (b) individual courses, and (c) course

con-tent and delivery. One of the overriding concerns of MBA programs that are accredited by the Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) International is meeting mission-driven standards that conform to accredita-tion standards. Although these standards have been relaxed in recent years, allowing programs more flexibility in meet-ing standards, meetmeet-ing program content and knowledge areas remains somewhat fixed (Bennis & O’Toole, 2005; Navarro, 2008). As a result of meeting accreditation core curricu-lum standards, the silo mentality is often maintained while garnishing these offerings with additional courses and dif-ferential program formats. The latter has spawned the debate of how to offer content that covers social responsibility and ethics, leadership, and globalization (Bruce & Edgington, 2008; Butler, Forbes, & Johnson, 2008; Crane, 2004; Evans, Trevino, & Weaver, 2006; Fukukawa, Shafer, & Lee, 2007; Krishnam, 2008; Navarro). Lastly, the subject of delivery of course knowledge and what is delivered has spurred ad-ditional debate—course-based versus experiential learning, traditional market perspectives versus innovative technolo-gies, market uncertainties, and a macro–social perspective (Pfeffer & Fong, 2002; Samuelson, 2006; Schoemaker, 2008; Tuleja, 2008). Although process issues are worthwhile sub-jects of debate, what is still missing is specific attitudinal knowledge of the inputs.

What Is Not Known

Information on the psychological makeup of the student body has only now started to surface in the literature. This was fostered by Leavitt’s (1991) charge that MBA faculty and administrators really do not care about the attitudes and be-liefs that MBA students learn and then later incorporate in their careers. In a study of student attitudes, sponsored by the Johnson Graduate School of Management at Cornell (Kiely, 1997), the findings show that students in the nation’s top MBA programs believe in maximizing profits, are more op-posed than older persons to government action for responsi-ble corporate behavior, and take a stricter financial view on making decisions. Much of this was speculative, academic debate until the cheating incident in the graduate school of business at Duke University. Conlin’s (2007) comment on this incident suggested that due to the use of Internet, open sourcing of information, and the use of teamwork in studies, it may be time to revisit how academics defineacademic dis-honesty. Is this really the wave of the future and exemplified by the likes of Madoff and Stanford? What an individual’s attitudes are, and their domain specificity, will largely influ-ence what is learned and how it is shaped in the learning process. A brief review of attitudinal research in business programs is presented in the following section.

In the last few years, academics have begun examin-ing the attitudes of undergraduate business and MBA stu-dents. Wilson and Galloway (2006) showed the importance of how MBA students have benefited from their shaping in the

MBA program and the resulting experience in their careers. Whittingham (2006) has examined the impact of personal-ity characteristics on MBA’s academic performance showing that the detached individual and the extrovert had higher performance for men, whereas women with higher consci-entiousness scores did better in quantitative courses. Further, Elias (2008) began research on the concept of academic self-efficacy versus anti-intellectual attitudes in an undergraduate business population. And Rawwas, Swaidan, and Isakson (2007) studied ethical beliefs of MBA students in the United States against those in Hong Kong, finding that U.S. stu-dents tended to behave ethically whereas their Hong Kong counterparts tended to act more morally.

How these types of studies shape MBA programs remains to be seen because the research deals with personality types, program experience, or ethical beliefs rather than attitudinal states of mind that influence behavior. Because it is known that attitudes play a major role in information processing, learning, and behavior (Hawkins, Mothersbaugh, & Best, 2007), an in-depth look at the attitudes held by MBA students should shed light on how they can be educated, with what material, and whether or not the material presented is con-sistent or inconcon-sistent with their attitudinal states. Learning takes place when ideas, concepts, and theories are consistent with attitudinal states. Impediments to learning are found in attitude conflict, which requires a major effort in attitude change prior to having a positive learning experience (Peter & Olson, 2008). Without this knowledge, the goals of the MBA program may suffer, faculty can be ineffective, and course content may be in conflict with the students’ beliefs.

METHOD

The MBA degree has become ubiquitous throughout the United States and the industrialized and developing world as the degree of choice for business managers. As a start-ing point for this research program, the universe was limited to the students attending an MBA program in the United States. Because both large and small colleges and univer-sities throughout the nation now offer the MBA degree, a representative area sample was drawn from AACSB member institutions with MBA programs. Deans, graduate program directors, and faculty were contacted personally, by phone, or electronically to gain their cooperation and to maintain a geographic, program size, public versus private, and reputa-tional balance in the sample. Many of the MBA programs opted not to participate stating one of two views. One view was that the study would be an invasion of student privacy. Or, secondly, it was the school’s policy not to let outsiders in-terview their students. In all, 27 graduate business programs agreed to participate in the study (see Appendix A). A bal-anced sample of the schools were from each geographic area of the country, represented a mixture of private and public institutions, programs that were both large and small in size,

and attracted students from international and national levels as well as those that were regional and local. Programs were represented by those in the top 50 MBA ranked programs (by

Business WeekorThe Financial Times of London) as well as those with lesser reputations. The latter programs are repre-sentative of where a vast majority of individuals obtain their MBAs and were, therefore, a higher proportion of programs included in this study.

The sample within each institution was drawn by pro-gram directors and faculty members. The instructions were to administer the survey instrument to first-year students to the program, and hopefully reduce bias in answers regarding the business community. The data was gathered during the spring, summer, and fall of 2008. Students were not pressured to participate in the study, completion was voluntary, and respondents would remain anonymous. In addition to item responses, information was obtained on the demographic characteristics of age, ethnicity, undergraduate major, un-dergraduate GPA, the unun-dergraduate institution awarding the degree (public vs. private), GMAT score, and years of work experience.

Sample Characteristics

The total completed returns came from 866 respondents from 27 graduate business programs. The sample consisted of the following characteristics: the mean age was 29 years; men and women represented 65.6% and 34.4% of the sample, respectively; undergraduate degrees were 72% from public-supported universities versus 28% from private universities and colleges; the mean GPA was 3.34; the mean GMAT score (of those 521 students reporting) was 579.7; and, the mean work experience was 7.0 years. Ranges for the demo-graphics indicate that a very wide dispersion of each fac-tor was captured in the sample. Age ranged from 20 to 65 years, and the ethnic makeup was 6.2% African American, 17.4% Asian, 2.9% Asian American, 64.5% Caucasian, 3.1% Hispanic, 0.2% Native American, and 5.6% other. Under-graduate majors included 50.6% business, 17.0% liberal arts, 11.0% engineering, 9.2% science, 1.4% health care, 7.2% computer science, and 3.6% communications. Undergradu-ate GPA ranged from 2.00 to 4.00, GMAT scores ranged from a low of 210 to a high of 780, and the number of years of work experience went from 0 to 45 years. Overall, the 866 respondents represented the span of students seeking the MBA degree and the mean scores were very typical of the average MBA student.

Instrument

To capture the attitudinal states of the MBA student respon-dents, the Short-Form Consumer Discontent Scale was em-ployed in the study. The Short-Form Consumer Discontent Scale is composed of 41 items measuring positive and nega-tive affect toward business practices and related, underlying business motives. The short-form scale was derived from the

MBA ATTITUDES TOWARD BUSINESS 181

Consumer Discontent Scale (Lundstrom & Lamont, 1976) and developed by Scott and Lundstrom (1990). Respondents were asked to express their feelings (attitudes) toward the 41 items related to business on a 6-point Likert-type scale rang-ing from 1 (strongly agree) to 6 (strongly disagree). Items that are positively worded are reverse coded to maintain di-rectionality of the total scale score. The scale and the items measure satisfaction, or dissatisfaction, with business and its practices. Total scale scores can range from 246 (a totally negative overall attitude) to 41 (a totally satisfied overall at-titude). Because the scale uses a forced format of 6 response categories, a mean score of 3.5 would represent a neutral position toward a particular item.

RESULTS

Reliability

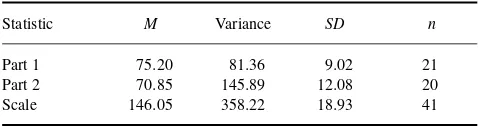

The survey data (Table 1) shows the Short-Form Consumer Discontent Scale to be consistent and indicates relatively high reliability factors. The coefficient alpha was .8596 and the Spearman-Brown and Guttman reliability scores were .75 and .73, respectively. These reliability measures are in keeping with those reported earlier by Scott and Lundstrom (1990) and Lundstrom and White (2006).

Much more interesting than the scale’s reliability coeffi-cients, even though it strongly suggests the scale’s durability over time, were the mean scores of the present sample. Be-cause the administration of the questionnaire, there has been significant downward movement in the economy. Whether these latter economic events that have taken place would change the perspective of the MBA students is unknown. It can only be speculated that the dimensions captured by the scale should be enduring and could be potentially mag-nified by some of the events that have occurred during the timeframe since its administration.

Item Differences

Given the large sample and geographic dispersion, the re-sults of the research are interesting and shed light on where MBA students stand on various attitudinal issues regarding the business community. Of major interest in this study are the attitudinal states of MBA students toward the domains

TABLE 1

Reliability Analysis of the Measure

Statistic M Variance SD n

Part 1 75.20 81.36 9.02 21

Part 2 70.85 145.89 12.08 20 Scale 146.05 358.22 18.93 41

Note. N=866; items=41; Guttman Split-half=.7313; Unequal-length Spearman-Brown=.7510;α=.8596.

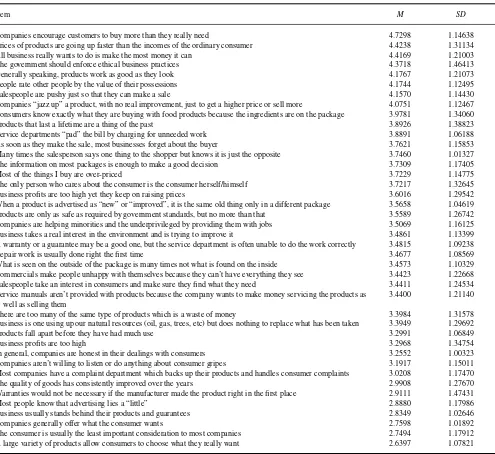

tapped by the individual items in the scale as well as the over-all scale score. These findings are presented in Table 2, which presents the mean scores and standard deviations for the total sample of MBA students. Item scores are presented in de-scending order from the most negative to the most positive scores on individual items.

Most negative. When looking at the items that the

stu-dents find most negative about business, there is a sense that business is insensitive to true consumer needs with the end goal of making as much money as it can. This is exemplified by the statements: “Companies encourage customers to buy more than they really need” (4.73), “All business really wants to do is make the most money it can” (4.42), “Salespeople are pushy just so they can make the sale” (4.16), “Compa-nies ‘jazz up’ a product, with no real improvement, just to get a higher price or sell more” (4.08), “Products that last a lifetime are a thing of the past” (3.89), and “As soon as they make the sale, most businesses forget about the buyer” (3.76). Interspersed with this overall negativity toward busi-ness, which may be labeled insensitive profit making, are rising prices, materialism, lack of true product information, and government intervention to enforce ethical practices.

Most positive. In the opposite direction, students found

many positive attributes about business, which was reflected in their positive attitudinal responses. The generally positive sentiment reflects the cornucopia of product offerings to sat-isfy needs, that the consumer is the central focus of offerings, that business stands behind its products with guarantees and warranties and has effective complaint departments, that the quality of goods has consistently increased over the years, and that businesses are honest in their dealings with con-sumers (see Table 2).

Midrange ‘hot’ issues. Certain items of interest in this

research could be considered hot issues that may be of con-cern to both MBA students and program-directed content. These issues concern sustainability, minorities and the un-derprivileged, business profits, advertising, and a consumer-centric empathy. Unfortunately, answers to these items fall into what can be called a mid-range of item responses that are relatively neutral. That is, item mean scores in the range of 3.3–3.7 indicate a neutral stance on the items measured. Thus, MBA students, on average, did not have strong attitudes about business helping minorities and the underprivileged (3.51), business taking an interest in the environment (3.48) or using up natural resources without replenishment (3.39), business profits being too high yet raising prices (3.60), advertising making people unhappy with themselves because they can’t have everything they see (3.44), and salespeople making sure customers find what they really need (3.44). In essence, none of these potentially hot issues are seen as present problems

TABLE 2

Item Mean Scores in Descending Order, From Most Negative to Most Positive

Item M SD

Companies encourage customers to buy more than they really need 4.7298 1.14638 Prices of products are going up faster than the incomes of the ordinary consumer 4.4238 1.31134 All business really wants to do is make the most money it can 4.4169 1.21003 The government should enforce ethical business practices 4.3718 1.46413

Generally speaking, products work as good as they look 4.1767 1.21073

People rate other people by the value of their possessions 4.1744 1.12495

Salespeople are pushy just so that they can make a sale 4.1570 1.14430

Companies “jazz up” a product, with no real improvement, just to get a higher price or sell more 4.0751 1.12467 Consumers know exactly what they are buying with food products because the ingredients are on the package 3.9781 1.34060

Products that last a lifetime are a thing of the past 3.8926 1.38823

Service departments “pad” the bill by charging for unneeded work 3.8891 1.06188 As soon as they make the sale, most businesses forget about the buyer 3.7621 1.15853 Many times the salesperson says one thing to the shopper but knows it is just the opposite 3.7460 1.01327 The information on most packages is enough to make a good decision 3.7309 1.17405

Most of the things I buy are over-priced 3.7229 1.14775

The only person who cares about the consumer is the consumer herself/himself 3.7217 1.32645 Business profits are too high yet they keep on raising prices 3.6016 1.29542 When a product is advertised as “new” or “improved”, it is the same old thing only in a different package 3.5658 1.04619 Products are only as safe as required by government standards, but no more than that 3.5589 1.26742 Companies are helping minorities and the underprivileged by providing them with jobs 3.5069 1.16125 Business takes a real interest in the environment and is trying to improve it 3.4861 1.13399 A warranty or a guarantee may be a good one, but the service department is often unable to do the work correctly 3.4815 1.09238

Repair work is usually done right the first time 3.4677 1.08569

What is seen on the outside of the package is many times not what is found on the inside 3.4573 1.10329 Commercials make people unhappy with themselves because they can’t have everything they see 3.4423 1.22668 Salespeople take an interest in consumers and make sure they find what they need 3.4411 1.24534 Service manuals aren’t provided with products because the company wants to make money servicing the products as

well as selling them

3.4400 1.21140

There are too many of the same type of products which is a waste of money 3.3984 1.31578 Business is one using up our natural resources (oil, gas, trees, etc) but does nothing to replace what has been taken 3.3949 1.29692

Products fall apart before they have had much use 3.2991 1.06849

Business profits are too high 3.2968 1.34754

In general, companies are honest in their dealings with consumers 3.2552 1.00323 Companies aren’t willing to listen or do anything about consumer gripes 3.1917 1.15011 Most companies have a complaint department which backs up their products and handles consumer complaints 3.0208 1.17470 The quality of goods has consistently improved over the years 2.9908 1.27670 Warranties would not be necessary if the manufacturer made the product right in the first place 2.9111 1.47431

Most people know that advertising lies a “little” 2.8880 1.17986

Business usually stands behind their products and guarantees 2.8349 1.02646

Companies generally offer what the consumer wants 2.7598 1.01892

The consumer is usually the least important consideration to most companies 2.7494 1.17912 A large variety of products allow consumers to choose what they really want 2.6397 1.07821

for the business community but lay in the midground of rel-atively neutral attitudinal states of the MBAs.

Overall Scores and Demographic Differences

As an additional input to the understanding of MBA attitudes toward business is the analysis of overall scale scores. Total scale scores can range from 41 (totally positive) to 246 (to-tally negative). A neutral score would be reflected by a total score of 143. Upon examination, the mean score for the over-all student group is 146.05—just a little toward a negative at-titude. The mean score of the total group, however, can mask the overall neutrality as seem by individual item scores. In an

effort to see whether there are group differences, an analysis of variance (ANOVA) was run on gender, ethnicity, under-graduate major, and type of underunder-graduate institution (public vs. private education) against the total scale score. Addition-ally, correlations were computed on the continuous variables of age, GPA, GMAT score, and work experience with the total scale score. These findings are presented subsequently. Overall, significant differences found were primarily due to the large sample sizes used in each of the analyses: mean scale scores for the demographic variables were within 10 total scale points of one another. The ANOVA results sug-gest that significant differences are found in the characteris-tics of gender (p<.01) and ethnicity (p<.01) but neither

MBA ATTITUDES TOWARD BUSINESS 183

in the undergraduate major nor whether the student attended a public or private institution. The gender differences sug-gest that women have a more negative attitude toward the business community than do men, 149.52 versus 144.23. Ethnic differences were found across the seven groups rep-resented in the study. The highest level of negativity was found in Asians (154.09), Asian Americans (152.60), and African Americans (152.47), whereas Caucasians had the lowest mean score of 142.69. Likewise, correlations on the continuous variables of GPA, GMAT score, work experience, and age showed insignificant and very low correlations with the overall scale score.

DISCUSSION AND IMPLICATIONS

The purpose of this research was to examine and understand the attitudinal states of MBA students toward the business community and business practices. It was unknown whether MBA students held positive, negative, or neutral attitudes toward this domain of activity nor whether there are dif-ferences among groups of students on various demographic characteristics. The results were interesting and varied and suggest that the new MBA graduate is one who may foster both pro and con attitudes about present business conduct and business values.

The research revealed that, overall, MBA students harbor an attitude that business is in the business to make as much money as it can while encouraging customers to buy more than they really need. This may feed into a cycle of materi-alism as a desired end state as consumers are encouraged to spend more and compare themselves to others having more than themselves. This is exhibited by the negative attitudes about people rating others by their possessions rather than qualities of a humanistic nature. This, in turn, may have lead to binging on credit to buy additional items, the vacation home, real estate investments, and other unneeded goods and services that has led to the present credit crisis. What is the proposed solution to this customer- and profit-driven market without concern for the consequences to the consumer? In-terestingly, the surveyed MBA students believed that it is the government who should enforce ethical business practices. Although this begs another question as to what are ethical business practices, it is evident that these respondents are seeking a solution by a higher order entity other than the business community itself.

In contrast, these respondents believe there are many good things about the business community and it is reflected in their positive attitudes. Leading the positive attitudes is the ability of business to provide a wide variety of products and services that customers want. This is combined with business standing behind their products with warranties and customer service departments who try to rectify problems. The re-spondents believe that goods and services have improved over the years and companies are willing to listen to their

needs, gripes, and complaints. However, a more fundamen-tal issue could be that business does listen, offers products and services, and stands behinds these offerings but does not truly consider what the impact of consumption does to the individual—morally, physically, and psychologically. This may be the essence of creating a new and different ethics course in business.

Although there are both positive and negative attitudes to-ward business, there is a broad midrange of attitudinal states that appear to exhibit neutrality on the part of the respon-dents. This midground is reflected in the neutral attitudes toward many of the issues that are considered politically important by some groups. The respondents had neutral at-titudes about business helping minorities and the underpriv-ileged, environmental issues, advertising and meeting safe product standards. Whether this is good or bad depends on the perspective. However, it is fertile ground for discussion and molding these attitudinal issues into ones of greater con-cern and, potentially, doing good for the greater whole of society.

Total scale scores suggest that women hold more antibusi-ness attitudes than men, as do Asians, Asian Americans, and African-Americans. Because these groups represent larger proportions of incoming MBA students, additional effort may be placed on educating these groups about business ethics, practices, and values. Particular emphasis could be made to il-lustrate how diversity efforts are working to include a greater number of women and non-Caucasians in the workforce.

What the research suggests is a look at the softer side of the transaction other than the simple buyer–seller dyad. That is, a more holistic approach to the customer may be warranted in the future for courses. This would include the social, psychological, economic, and technological impacts on the individual rather than trying to investigate the buyer as a transactional unit. By widening the understanding of the individual, business would have a much different mindset of how and why the person functions other than as a consump-tion unit with certain needs, wants and desires.

Limitations

There were limitations to the research in that it represents the attitudes of a subset of MBA students just prior to a major financial crisis. Further administrations that include the outcome of the financial crisis and the abuses that were unveiled may increase the negativity of the responses. The inability to freely sample from all graduate programs could potentially limit the generalization of the results to a larger student population. Also, the administration of the instrument to first-year students by program directors and faculty may potentially skew the results. However, even recognizing these potential shortcomings, the diversity of the representation and the size of the sample would tend to negate these possible pitfalls.

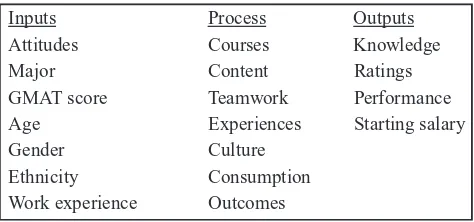

Inputs Process Outputs

FIGURE 1. A new humanistic model for MBA programs, from a holistic

and humanistic perspective.

Implications

The implications of this research study go beyond the atti-tudes of these MBA students and may potentially impinge on the culture and content of MBA programs. First and foremost, these students are people from varying backgrounds, hold-ing differhold-ing attitudes about the community they study. In-dividual students enter MBA programs with thoughts, ideas, values, and attitudes. They are definitely not the blank slates they are sometimes assumed to be. Our courses on ethics need to consider the buyer and the implications that business practices and the business value system has upon them and not just the business community. It is more than just operat-ing in an ethical manner but to be morally just in transactions with customers and gage the impact academics have on them as humans. Perhaps it is necessary to recast MBA program content to include the study of the evolution of societies, reli-gions around the world, and human needs, wants, and desires outside the consumption environment (Figure 1). This same line of reasoning could also be applied to marketing courses that interface with the buying public. To date, most marketing courses stress value driven, or customer value as the mantra of the product or service offering (Kerin & Peterson, 2010). What happens after the value is delivered, consumed, forgot-ten, or disposed of? Is the customer better off than before? Is society? What is the impact on the environment? Thus, it is necessary to redefine the consumption process from the transaction to the totality of the consumption process. Not only how it is done (the process focus of business), but also the long-range consequences of the collective whole of con-sumption. This somewhat different perspective would funda-mentally change the culture of many MBA programs while addressing many of the issues that were brought forward in this study.

CONCLUSION

The purpose of this research study was to ascertain the atti-tudinal states of a national sample of MBA students toward the business community and its practices. The study

encom-passed 27 MBA programs and 866 respondents as measured by the Short-Form Consumer Discontent Scale. Uncovered in this research were a wide variety of attitudes toward many different items in the measure.

The most negative attitudes registered were those encour-aging consumers to buy needlessly just to drive business prof-its. The most positive attitudes centered on offering a wide variety of products and services so that customers had many choices. In the neutral categories, were attitudes toward the environment, minorities, and the underprivileged, advertis-ing, and product safety. Significant demographic differences were exhibited across race and gender but not undergradu-ate major or public versus privundergradu-ate colleges. Attitudes were slightly correlated with age but not with GPA, GMAT score, or work experience.

Results from the study suggest that MBA programs need to reassess their process orientation and look at developing a more holistic, humanistic framework of the inputs and out-comes of the consumption process. Only then can the man-agers of tomorrow fully understand the magnitude of what they are doing in creating a societal good (or evil).

Future researchers should administer the Consumer Dis-content Scale instrument to another sample of MBA students from a similarly broad population. It would be interesting to note the changes in attitudes that have taken place since the outcome of the global financial crisis and the continuing saga of how greed contributed to the downfall. Further, the attitu-dinal structure of the underlying factors contributing to these states should be examined. As a continuing product of this research, individual MBA programs and accreditation bodies should establish task forces to examine the fundamental na-ture and content of an holistic and humanistic MBA program the focus of which is the individual in many different con-texts. The starting point in this is simple; it is the satisfaction of future customer needs that must be met to be successful.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Funding for this research was provided by MERInstitute Grant, Graduate Management Admission Council.

REFERENCES

Bennis, W. G., & O’Toole, J. (2005). How business schools lost their way. Harvard Business Review.83, 96–104.

Bruce, G., & Edgington, R. (2008). Ethics education in MBA programs: Effectiveness and effects.International Journal of Management & Mar-keting Research,1(1), 49–69.

Butler, D., Forbes, B., & Johnson, L. (2008). An examination of a skills-based leadership coaching course in an MBA program.Journal of Edu-cation for Business,83, 227–232.

Conlin, M. (2007, May 14). Cheating—or postmodern learning?Business Week,4034, 42.

MBA ATTITUDES TOWARD BUSINESS 185

Crane, F. G. (2004). The teaching of business ethics: An imperative at business schools,Journal of Education for Business,79, 149–151. Elias, R. Z. (2008). Anti-intellectual attitudes and academic self-efficacy

among business students.Journal of Education for Business,84, 110–117. Endres, M. L., Chowdhury, S., Frye, C., & Hurtubis, C. A. (2009). The multifaceted nature of online MBA student satisfaction and impacts on behavioral intentions.Journal of Education for Business,84, 304–312. Evans, J., Trevino, L. K., & Weaver, G. (2006). Who’s in the ethics driver’s

seat? Factors influencing ethics in the MBA curriculum. Academy of Management Learning & Education.5, 278–293

Fukukawa, K., Shafer, W., & Lee, G. (2007). Values and attitudes toward so-cial and environmental accountability: A study of MBA students.Journal of Business Ethics,71, 381–394.

Graduate Management Admission Council. (2008a). Profile of GMAT candidates. Retrieved from http//www.gmac.com/gmac/Researchand-Trends/GMATStats/ProfileofCandidates.htm

Graduate Management Admission Council. (2008b). All research reports. Retrieved from http//www.gmac.com/gmac/researchandtrends/ researchreportsseries/allresearchreports.htm

Hawkins, D. I., Mothersbaugh, D. L., & Best R. (2007).Consumer behavior: Building marketing strategy (10th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Hsu, M. K., Chao, G. H., & James, M. (2009). An efficiency comparison of MBA programs: Top 10 versus non-top 10.Journal of Education for Business,84, 269–275.

Kerin, R., & Peterson, R. (2010).Strategic marketing problems(12th ed.). New York, NY: Prentice Hall.

Kiely, T. (1997). Tomorrow’s leaders. Harvard Business Review,75(2), 12–13.

Krishnam, V. (2008). Impact of MBA education on students’ values: Two longitudinal studies.Journal of Business Ethics,83, 233–246.

Leavitt, H. (1991). Socializing our MBAs: Total immersion? Managed cul-tures? Brainwashing?California Management Review,33, 127–143. Lundstrom, W. J., & Lamont, L. M. (1976). The development of a scale

to measure consumer discontent. Journal of Marketing Research,13, 373–381.

Lundstrom, W. J., & White, D. S. (2006). Consumer discontent revisited. Journal of Academy of Business and Economics,6, 142–152.

Navarro, P. (2008). The MBA core curricula of top-ranked U.S. business schools: A study in failure?Academy of Management Learning & Edu-cation,7, 108–123.

Peter, J. P., & Olson, J. C. (2008).Consumer behavior and marketing strategy (8th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Irwin.

Pfeffer, J., & Fong, C. T. (2002). The end of business schools? Less success than meets the eye.Academy of Management Learning and Education,1, 78–96.

Rawwas, M., Swaidan, S., & Isakson, H. (2007). A comparative study of ethical beliefs of master of business students in the United States with those in Hong Kong.Journal of Education for Business,82, 146–158. Samuelson, J. (2006). The new rigor: Beyond the right answer.Academy of

Management Learning & Education,5, 356–365.

Schoemaker, P. J. H. (2008). The future challenges of business: Rethinking management education.California Management Review,50, 119–139. Scott, C., & Lundstrom, W. J. (1990) Dimensions of possession

satisfac-tion: A preliminary analysis.Journal of Satisfaction, Dissatisfaction and Complaining Behavior,3, 100–104.

Sulaiman, A., & Mohezar, S. (2006). Student success factors: Identi-fying key predictors. Journal of Education for Business, 81, 328– 333.

Truell, A., Zhao, J., Alexander, M., & Hill, I. (2006). Predicting final student performance in a graduate business program: The MBA.Delta Pi Epsilon Journal,48, 144–152.

Tuleja, E. (2008). Aspects of intercultural awareness through an MBA study abroad program: Going backstage.Business Communication Quarterly, 71, 314–337.

Whittingham, K. L. (2006). Impact of personality on academic performance of MBA students: Qualitative versus quantitative courses.Decision Sci-ences Journal of Innovative Education,4, 175–190.

Wilson, S. R., & Galloway, F. (2006). What every business school needs to know about its master of business administration (MBA) graduates. Journal of Education for Business,82, 95–100.

APPENDIX A

MBA Programs Participating in the Study

Baldwin-Wallace College Babson College

Boise State University Brandeis University

California State University, San Marcos Case Western Reserve University