DOI: 10.1542/peds.2007-0233

2007;120;481-488

Pediatrics

Horbar, Richard C. Wasserman, Patricia Berry and Judith S. Shaw

Charles E. Mercier, Sara E. Barry, Kimberley Paul, Thomas V. Delaney, Jeffrey D.

Collaborative, Hospital-Based Quality-Improvement Project

Improving Newborn Preventive Services at the Birth Hospitalization: A

http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/120/3/481

located on the World Wide Web at:

The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, is

rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.

ARTICLE

Improving Newborn Preventive Services at the Birth

Hospitalization: A Collaborative, Hospital-Based

Quality-Improvement Project

Charles E. Mercier, MDa, Sara E. Barry, MPHa, Kimberley Paul, BSNa, Thomas V. Delaney, PhDa, Jeffrey D. Horbar, MDa,b,

Richard C. Wasserman, MD, MPHa, Patricia Berry, MPHc, Judith S. Shaw, RN, MPHa

aDepartment of Pediatrics, University of Vermont, Burlington, Vermont;bVermont Oxford Network, Burlington, Vermont;cVermont Department of Health, Burlington,

Vermont

The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

ABSTRACT

OBJECTIVE.The goal was to test the effectiveness of a statewide, collaborative, hospi-tal-based quality-improvement project targeting preventive services delivered to healthy newborns during the birth hospitalization.

METHODS.All Vermont hospitals with obstetric services participated. The quality-improvement collaborative (intervention) was based on the Breakthrough Series Collaborative model. Targeted preventive services included hepatitis B immuni-zation; assessment of breastfeeding; assessment of risk of hyperbilirubinemia; performance of metabolic and hearing screens; assessment of and counseling on tobacco smoke exposure, infant sleep position, car safety seat fit, and exposure to domestic violence; and planning for outpatient follow-up care. The effect of the intervention was assessed at the end of an 18-month period. Preintervention and postintervention chart audits were conducted by using a random sample of 30 newborn medical charts per audit for each participating hospital.

RESULTS.Documented rates of assessment improved for breastfeeding adequacy (49% vs 81%), risk for hyperbilirubinemia (14% vs 23%), infant sleep position (13% vs 56%), and car safety seat fit (42% vs 71%). Documented rates of counseling improved for tobacco smoke exposure (23% vs 53%) and car safety seat fit (38% vs 75%). Performance of hearing screens also improved (74% vs 97%). No significant changes were noted in performance of hepatitis B immuni-zation (45% vs 30%) or metabolic screens (98% vs 98%), assessment of tobacco smoke exposure (53% vs 67%), counseling on sleep position (46% vs 68%), assessment of exposure to domestic violence (27% vs 36%), or planning for outpatient follow-up care (80% vs 71%). All hospitals demonstrated preinterven-tion versus postintervenpreinterven-tion improvement of ⱖ20% in ⱖ1 newborn preventive

service.

CONCLUSIONS.A statewide, hospital-based quality-improvement project targeting hospital staff members and community physicians was effective in improving documented newborn preventive services during the birth hospitalization.

www.pediatrics.org/cgi/doi/10.1542/ peds.2007-0233

doi:10.1542/peds.2007-0233

Key Words

preventive services, quality improvement, infant, newborn, birthing centers, hospital

Abbreviations BTS—Breakthrough Series OR— odds ratio CI— confidence interval QI— quality improvement

Accepted for publication Apr 23, 2007 Address correspondence to Charles E. Mercier, MD, Smith 578, Fletcher Allen Health Care-Medical Center Hospital of Vermont Campus, 111 Colchester Ave, Burlington, VT 05401. E-mail: [email protected]

C

OMPREHENSIVE PREVENTIVE HEALTHcare for children begins with adequate obstetric and pediatric prena-tal care.1,2For pediatricians, the prenatal visit serves toinitiate a trusting relationship with the parents and to establish the infant’s medical home. Preventive health care services such as anticipatory guidance on pertinent parenting issues and screenings for identification of high-risk situations can also occur at the prenatal visit.3

Although it is endorsed by the American Academy of Pediatrics and supported by pediatricians, as few as 11% of parents are seen for the pediatric prenatal visit.4The

birth hospitalization may be the first encounter new parents have with the pediatric health care practitioner. When pediatric practitioners initiate health care ser-vices during the birth hospitalization, they work closely with hospital nursing staff members responsible for post-partum and newborn care. The Guidelines for Perinatal Care5state that such nursing care should include initial

and ongoing assessment, newborn care education, sup-port for the attachment process, preparation for healthy parenting, and preparation for discharge and follow-up monitoring of the mother and her newborn. The recom-mended nurse/patient ratio for normal mother-newborn couplet care is 1 nurse for every 3 or 4 mother-newborn couplets.

In 2004, the American Academy of Pediatrics recom-mended a set of initial health care services to be pro-vided, and minimal criteria to be met, before hospital discharge for well newborns.6 Newborn preventive

health care services, including assessment for immuni-zation, metabolic and hearing screenings, anticipatory guidance, risk assessment, and counseling, were among this inventory of recommendations for care during the birth hospitalization.

Over the past several decades, the length of the birth hospitalization has become increasingly short. In 2003, the National Committee for Quality Assurance Health Plan Employer Data Information Set reported the me-dian length of birth hospital stay for well newborns to be 2.2 days.7Extensive work has been performed to

exam-ine the impact of decreased length of stay for well term newborns, although that work was largely limited to a focus on rehospitalizations8–11 or outpatient follow-up

services.12–14 Despite well-documented variability and

deficiencies in the delivery of preventive care in pediatric settings,15–17we found no literature about the

complete-ness of preventive health care services for well newborns during the birth hospitalization.

Quality improvement (QI) collaboratives offer a method for improving the delivery of appropriate health care services. In pediatrics, national and state QI collabo-ratives have focused on improving the quality and safety of care for premature infants and their families in the NICU18 and term infants in the pediatric office

set-ting.19–21However, health care services provided to well

newborns during the birth hospitalization were not in-cluded in that work.

The current intervention implements QI methods modified from the Institute for Healthcare Improvement Breakthrough Series (BTS) Collaborative,22,23

incorporat-ing shared learnincorporat-ing, coachincorporat-ing from a team of experts, provider education, measurement, and feedback. The aim of this study was to examine the effects of a QI intervention on the delivery of newborn preventive health care services during the birth hospitalization in a statewide sample of community hospitals delivering ob-stetric care.

METHODS

Study Setting and Design

All Vermont hospitals with obstetric services were re-cruited to participate. The project principal investigator (Dr Mercier) met with the chief executive officer or designee from each hospital, explained the goals of the project, and described the responsibilities and resources required for hospital participation. Each hospital signed a consent form committing to participation in the project. Hospitals participated in the project for an 18-month period. Hospital participation was initiated on a rolling basis, beginning in May 2002. All hospitals com-pleted the study by June 2004. Audits of 30 newborn medical charts were performed at each hospital for each preintervention and postintervention measurement of preventive health care service delivery. Medical charts were selected at random from lists generated using hos-pital discharge records for newborns delivered in the previous 6 months. Data on predefined preventive health care service variables were abstracted by a team of trained chart abstractors from the Vermont Child Health Improvement Program.24

The selection of newborn preventive services was generally drawn from the American Academy of Pe-diatrics policy statement on the hospital stay for healthy term newborns7and the American Academy

of Pediatrics periodicity schedule.25 The mixture of

newborn preventive services included sensory screen-ing, general procedure, and anticipatory guidance ser-vices. For anticipatory guidance, the risk assessment and counseling tasks of the service were counted as separate services. For example, sleep position assess-ment and sleep position counseling were treated as 2 distinct preventive services. Each of the newborn pre-ventive services was supported by a professional guideline or health policy statement.26–35

safety seat fit, and exposure to domestic violence; and planning for outpatient follow-up care. Services were defined as having been delivered on the basis of docu-mentation in the newborn medical chart. Interrater agreement, defined as the proportion of items coded identically by 2 chart auditors, was established with a random sample of 20% of the charts from each hospital for each measurement period and exceeded 95%. The study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Vermont. All data were collected before the implementation of the Federal Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Population

The population consisted of hospital-born, healthy, newborn infants. There were no gestational age or birth weight limitations; multiple births as well as singleton infants were included. Infants transferred into or out of their birth hospital were excluded.

QI Intervention

Thirteen hospital-based newborn preventive health care services were targeted for the QI intervention. The in-tervention was based on a modified BTS Collaborative model.22,23Each hospital received a performance report

of the preintervention measurement (feedback session) for 13 hospital-based newborn preventive health care services. The feedback session was presented at a facili-tated, multidisciplinary, peer-protected, on-site meeting. The report identified opportunities to improve perfor-mance in the delivery of these hospital-based newborn services. After the report, each hospital was encouraged to form a multidisciplinary (nurse, physician, and qual-ity specialist) hospital-improvement team. Teams were provided guideline- and literature-based references for each of the 13 newborn preventive health care services. Table 2 lists the measurable aims for newborn preven-tive health care services that teams were offered and could choose to adapt to their specific clinical practice. Teams were encouraged to attend 4 face-to-face

state-wide meetings (learning sessions), participate in self-measurement activity, submit monthly progress reports, and participate in coaching calls on process improve-ment methods with project staff members. Continuing medical education and nursing contact hours were pro-vided for both feedback and learning sessions.

Learning sessions focused on planning for outpatient follow-up care, assessment of risk for hyperbiliru-binemia, and assessment of exposure to domestic vio-lence. These 3 topics were chosen because of the com-plexity of organizational and operational issues involved in implementing current guideline recommendations. At the learning sessions, invited experts reviewed the cur-rent literature supporting guideline recommendations, and parents or family members presented personal ex-periences. Hospital teams reviewed potentially effective strategies to improve delivery of these preventive ser-vices and received coaching on process improvement, based on the plan-do-study-act cycle method.36 Each TABLE 1 Definition of Data Variables

Variable Definition

Hepatitis B immunization Hepatitis B immunization given

Assessment of breastfeeding adequacy Suck or latch, audible swallow, and position for holding infant documented Assessment of risk for hyperbilirubinemia Total serum bilirubin sample drawn or transcutaneous measurement

performed

Performance of newborn metabolic screen Performance of newborn metabolic screen documented Performance of newborn hearing screen Performance of newborn hearing screen documented Assessment of tobacco smoke exposure Maternal tobacco smoking assessment documented Assessment of infant sleep position Infant sleep position observed and documented Assessment of car safety seat fit Infant fit in car safety seat observed and documented Assessment of domestic violence Maternal exposure to domestic violence documented

Counseling on tobacco smoke exposure Counseling on risk of infant tobacco smoke exposure documented Counseling on infant sleep position Counseling on proper infant sleep position documented Counseling on car safety seat fit Counseling on proper infant fit in car seat documented

Planning for outpatient follow-up care Day or date of planned newborn follow-up assessment documented

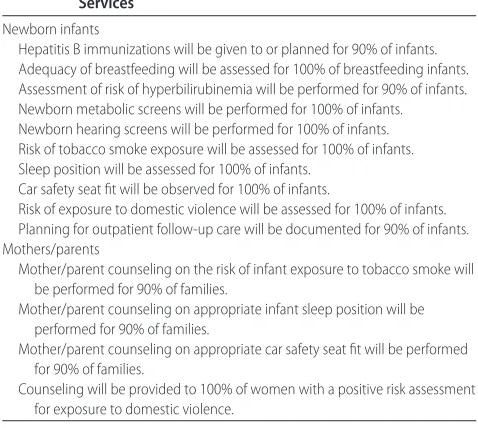

TABLE 2 Measurable Aims for Newborn Preventive Health Care Services

Newborn infants

Hepatitis B immunizations will be given to or planned for 90% of infants. Adequacy of breastfeeding will be assessed for 100% of breastfeeding infants. Assessment of risk of hyperbilirubinemia will be performed for 90% of infants. Newborn metabolic screens will be performed for 100% of infants. Newborn hearing screens will be performed for 100% of infants. Risk of tobacco smoke exposure will be assessed for 100% of infants. Sleep position will be assessed for 100% of infants.

Car safety seat fit will be observed for 100% of infants.

Risk of exposure to domestic violence will be assessed for 100% of infants. Planning for outpatient follow-up care will be documented for 90% of infants. Mothers/parents

Mother/parent counseling on the risk of infant exposure to tobacco smoke will be performed for 90% of families.

Mother/parent counseling on appropriate infant sleep position will be performed for 90% of families.

Mother/parent counseling on appropriate car safety seat fit will be performed for 90% of families.

learning session designated facilitated time for hospital teams to review their preintervention data, to identify gaps in performance, to identify potential changes in their practice that could improve performance, and to develop strategies to test these changes. Hospital teams were also encouraged to choose ⱖ1 other preventive

health care service for targeted improvement work. Modifications to the BTS model included a longer time frame (18 months) during which the intervention was conducted, a greater number of learning sessions (4 sessions) in which hospital teams participated, clinical topic-based presentations at the learning sessions, a greater number of one-on-one coaching telephone calls to team leaders by the project director, systematic shar-ing of deidentified hospital-level data among improve-ment teams, and no facilitated conference calls between participating hospitals.

Outcomes

The primary outcome measure was the aggregate prein-tervention to postinprein-tervention change in delivery of newborn preventive health care services during the birth hospitalization. Improvement in the delivery of preven-tive services at each individual hospital was also exam-ined.

Data Analysis

The data analysis compared preintervention and postint-ervention measures of the delivery of newborn preven-tive health care services. The data were aggregated across hospitals and examined with regard to assump-tions of statistical normality. Logistic regression models were used for analysis of preintervention versus postint-ervention changes for each preventive service variable. In one set of logistic regressions, the models included terms for time (preintervention versus postintervention) and were adjusted to account for changes in Medicaid eligibility (Medicaid or Medicaid eligible versus privately insured) and short length of stay (⬍48 hours versusⱖ48

hours). Models that were not adjusted were also run. For each measure, odds ratios (ORs) for the logistic regres-sion model were generated and evaluated by using a Wald statistic;␣was .05. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) of the ORs were adjusted for clustering of patients within hospitals.

RESULTS

All Vermont hospitals with obstetric services participated (n⫽12; see “Acknowledgments”). All hospitals formed project-improvement teams, and all hospital teams at-tended each learning session, participated in self-mea-surement activity, submitted monthly progress reports, and participated in coaching calls on process-improve-ment methods from project staff members. The median number of health care preventive services for which hospital teams conducted formal process-improvement

work (including plan-do-study-act cycles) was 5 (range: 4 –9 services).

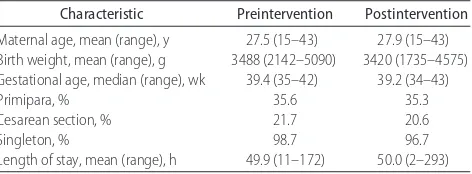

In all, medical charts of 719 newborns were reviewed (359 for the preintervention measurement and 360 for the postintervention measurement), representing ⬃9% of the hospital births that occurred in Vermont during the study period. Table 3 shows the characteristics of the preintervention and postintervention samples. Samples did not differ in the characteristics of average maternal age, birth weight, gestational age, length of hospital stay, or proportions of primiparous births, cesarean sections, or singleton births.

Table 4 shows the results for the aggregate changes in delivery of the 13 newborn preventive health care ser-vices at participating hospitals. Numbers in the unad-justed columns reflect the ORs, the 95% CIs for the ORs, and the P values obtained by using logistic regression analyses without adjustment for changes in Medicaid eligibility or short length of stay. Numbers in the ad-justed columns reflect the ORs, the 95% CIs for the ORs, and the P values obtained by using logistic regression analyses with adjustment for changes in Medicaid eligi-bility or short length of stay. Medicaid status data were not obtained for 1 hospital in the preintervention mea-surement; we used the median insurance status value from the postintervention data for that hospital in the logistic regression equation for the 30 affected cases of preintervention data. In 19 cases in which data on length of stay were not available, the hospital- and measure-ment-specific (preintervention versus postintervention) median value from the other cases was substituted for the missing data.

Adjustment of the regression models for Medicaid eligibility and short length of stay did not have an impact on the analysis of the findings. Significant increases in the delivery of newborn preventive health care services were identified for the assessment of breastfeeding ade-quacy (49.4% vs 80.6%;P⫽.03), assessment of risk of hyperbilirubinemia (14.4% vs 23.4%;P⫽.04), perfor-mance of newborn hearing screens (74.1% vs 97.4%;P ⫽ .01), assessment of infant sleep position (12.7% vs 55.7%;P⫽.02), observation of car safety seat fit (41.8% vs 71.0%;P⫽.04), counseling on tobacco smoke expo-sure (22.7% vs 52.6%;P⫽.03), and counseling on car

TABLE 3 Demographic Measures for the Preintervention and Postintervention Samples

Characteristic Preintervention Postintervention

Maternal age, mean (range), y 27.5 (15–43) 27.9 (15–43) Birth weight, mean (range), g 3488 (2142–5090) 3420 (1735–4575) Gestational age, median (range), wk 39.4 (35–42) 39.2 (34–43)

Primipara, % 35.6 35.3

Cesarean section, % 21.7 20.6

Singleton, % 98.7 96.7

safety seat fit (37.6% vs 74.7%;P⫽.02). No significant changes were noted for the performance of hepatitis B immunization (45.3% vs 29.7%;P⫽.19), performance of newborn metabolic screens (98.0% vs 98.2%; P ⫽

.89), assessment of tobacco smoke exposure (52.5% vs 66.7%; P ⫽ .17), assessment of domestic violence (27.1% vs 36.2%;P⫽.51), counseling on infant sleep position (46.4% vs 68.3%; P ⫽ .08), or planning for outpatient follow-up care (80.3% vs 71.4%;P⫽.38).

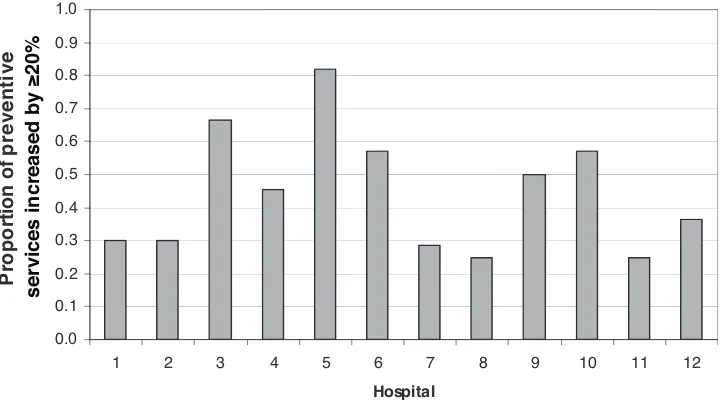

To describe the variability of improvement among individual hospitals, we calculated a hospital improve-ment quotient. The improveimprove-ment quotient was the number of newborn preventive health care services for which there was aⱖ20% increase from preintervention

measurement to postintervention measurement, divided by the total number of services for which an improve-ment ofⱖ20% was possible for a given hospital. Figure

1 shows hospital improvement quotients.

Improvement quotients varied among hospitals, ranging from 0.25 at hospitals 8 and 11 to 0.82 at hos-pital 5. Hoshos-pitals with greater numbers of services for which improvement was possible had greater numbers of improved services (r⫽0.692;P⫽.013).

Whether improvement in infant assessment was re-lated to improvement in family counseling for a specific preventive service was also examined. We evaluated infant assessment for and family counseling on tobacco smoke exposure, infant sleep position, and car safety seat fit, using 20% as the minimum for a change to be considered an improvement. Of 6 hospitals that had the opportunity to improve both assessment of and counsel-ing on tobacco smoke exposure, 1 hospital did so. Of 8 hospitals that had the opportunity to improve both as-sessment of and counseling on infant sleep position, 3 hospitals did so. Of 7 hospitals that had the opportunity to improve both assessment of and counseling on infant

TABLE 4 Preintervention Versus Postintervention Results, Unadjusted and Adjusted for Clustering of Patients at Hospitals

Variable Proportion, % Unadjusted Adjusteda

Preintervention Postintervention Change OR (95% CI) P OR (95% CI) P

Hepatitis B immunization 45.3 29.7 ⫺15.6 0.51 (0.22–1.19) .12 0.51 (0.37–0.70) .19

Assessment of breastfeeding adequacyb 49.4 80.6

⫹31.2 4.24 (1.16–15.46) .03c 4.49 (3.04–6.62) .03c

Assessment of risk for hyperbilirubinemia 14.4 23.4 ⫹9.0 1.83 (1.08–3.11) .03c 1.96 (1.31–2.95) .04c

Metabolic screening 98.0 98.2 ⫹0.2 0.98 (0.20–4.95) .99 1.14 (0.39–3.33) .89

Hearing screening 74.1 97.4 ⫹23.3 13.38 (3.17–56.46) .01c 14.31 (7.05–29.06) .01c

Assessment of smoke exposure 52.5 66.7 ⫹14.2 1.77 (0.91–3.44) .09 1.77 (1.31–2.41) .17

Assessment of sleep position 12.7 55.7 ⫹43.0 8.81 (1.62–47.90) .01c 9.08 (6.21–13.28) .02c

Assessment of car safety seat fit 41.8 71.0 ⫹29.2 3.41 (1.18–9.82) .02c 3.42 (2.51–4.67) .04c

Assessment of domestic violence 27.1 36.2 ⫹9.1 1.43 (0.60–3.41) .42 1.43 (1.04–1.96) .51

Counseling on smoke exposure 22.7 52.6 ⫹29.9 3.71 (1.29–10.66) .02c 3.75 (2.72–5.19) .03c

Counseling on sleep position 46.4 68.3 ⫹21.9 2.49 (0.99–6.29) .06 2.56 (1.88–3.47) .08

Counseling on car safety seat fit 37.6 74.7 ⫹37.1 4.99 (1.41–17.59) .02c 5.07 (3.67–7.01) .02c

Planning for follow-up care 80.3 71.4 ⫺8.9 0.61 (0.25–1.51) .31 0.60 (0.43–0.86) .38

aAdjusted on the basis of insurance status (Medicaid versus non-Medicaid) and length of stay of⬍48 hours. bBased on numbers of breastfed infants (preintervention:n⫽271; postintervention:n⫽278). cP⬍.05.

0 .0

0. 1 0. 2 0. 3 0. 4 0. 5 0. 6 0. 7 0. 8 0. 9

1.0

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12

Ho sp it al

Pr

opor

ti

on

of

preventive

services increased by ≥20%

FIGURE 1

car safety seat fit, 5 hospitals did so. Whether improve-ment in one area of family counseling correlated with improvement in other counseling preventive services was examined for tobacco smoke exposure, infant sleep position, and care safety seat fit. When these were ex-amined as combinations of counseling services, 6 hospi-tals had the opportunity to improve (⬎20%) in all 3 areas, and 3 did so. At the level of the individual infant, 12.2% of families received all 3 counseling services at preintervention measurement and 44.4% of families re-ceived all 3 at postintervention measurement (adjusted OR: 5.71; 95% CI: 3.87– 8.44;P⫽.01).

DISCUSSION

We engaged 12 hospitals in a QI collaborative targeting newborn preventive services during the birth hospital-ization. Significant improvements were seen in the as-sessments of breastfeeding adequacy, the risk of hyper-bilirubinemia, infant sleep position, and car safety seat fit. The performance of newborn hearing screens and counseling on tobacco smoke exposure and car safety seat fit also improved. Hospitals with more areas to improve demonstrated a greater number of improve-ments. More research is needed to understand the pre-dictors of a hospital’s success in improvement work.

The preventive services audited did not include all newborn preventive services appropriate for the birth hospitalization. Furthermore, the preventive services chosen for this work neither indicated our prioritizing of services nor suggested a standard of medical care. Fi-nally, the mixture of preventive services focused exclu-sively on newborn care and safety. In general, routine obstetric prenatal care, such as maternal screening for syphilis or HIV infection, which ultimately could affect the health status of the newborn, was not included in this work. The one exception was the assessment of maternal tobacco use.

Measurement of preintervention and postinterven-tion newborn preventive services relied exclusively on medical chart audits performed by study personnel. None of the medical charts selected for either the prein-tervention or postinprein-tervention audit was found to be missing or unavailable or was judged as incomplete by study personnel. Although study personnel had no affil-iation with a hospital whose medical charts were au-dited, those individuals were aware of the project objec-tives.

Audits of newborn medical charts reflected documen-tation in the medical charts. It is possible that changes in the delivery of preventive services occurred as a result of changes in documentation and not actual improve-ments. This was of particular concern when counseling services were assessed. However, our chart auditors rou-tinely found evidence of standardized tools that either scripted counseling or served as triggers prompting re-view of several parental teaching points.

Documentation of newborn preventive services in the mothers’ medical charts would not have been discovered in our audits. It is possible that exclusion of the mothers’ medical charts from the auditing process affected the results of the intervention. This was of particular con-cern when exposure to domestic violence was assessed. Hospital staff members admitted that, when the father of the infant was alleged as the perpetrator of domestic violence, anxiety about his access to the newborn med-ical chart was a specific barrier to documentation of assessment. It is likely that this barrier had an impact on our ability to measure changes in the assessment of maternal exposure to domestic violence across the inter-vention period.

Eleven of 12 hospitals that participated in this project exclusively offered basic (level 1) obstetric services to their communities. The numbers of licensed beds in these level 1 hospitals ranged from 25 to 188; 4 hospitals had⬍50 beds. In 2003, the numbers of births in these level 1 hospitals ranged from 213 to 570. All 11 level 1 hospitals were actively engaged in a regionally coordi-nated system of perinatal health care services that sup-ported interhospital patient transfer to a subspecialty (level 3) perinatal health care center, as well as profes-sional nurse and physician continuing education. As a part of this regional system, birth center nurse managers at all 11 level 1 hospitals routinely met as a group, semiannually, to discuss issues related to managing ob-stetric and birthing center units. At least 1 pediatric practice serving each hospital had previous experience participating in a statewide, office-based, QI project tar-geting preventive services.21 Each hospital also had a

representative from the Vermont Department of Health affiliated with the hospital and participating in the project team.

The true total cost is difficult to define. We estimate that the cost of conducting the project, including all personnel and operating costs, was $350 000, or approx-imately $29 000 per hospital. An additional unmeasured cost is that of the staff time devoted by each hospital in carrying out the QI work. With ⬃5900 well newborn infants per year born in the state and the estimate that this project affected 97% of that population, the cost per infant over the period of this intervention was approxi-mately $41.

The effect of our modified BTS intervention was as-sessed at the end of an 18-month intervention period. The ideal time to assess the effect of an intervention is not clear.37 Notable changes in practice patterns could

the initiation of this project.38 During the intervention

period, the US Food and Drug Administration licensed a combined diphtheria, tetanus toxoids, acellular pertussis absorbed, hepatitis B (recombinant), and inactivated po-liovirus vaccine (Pediarix; SmithKline Beecham Biologi-cals, Rixensart, Belgium) for use for infants 2, 4, and 6 months of age.39 This event likely contributed to the

decrease in the postintervention immunization rate to 29.7%.

CONCLUSIONS

Hospital-based birthing center teams were able to iden-tify opportunities for improvement, to support a single set of improvement goals, to learn to apply basic QI methods, and, in doing so, to improve the quality of newborn care provided at a statewide level. Perfor-mance-based feedback, education on evidence-based practice, and parental testimony each made important contributions to the success of hospital team efforts. Leadership from the state department of health and an experienced QI team based in an academic medical cen-ter was important to hospital-based team success.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Participating hospitals were as follows: Brattleboro Me-morial Hospital, Brattleboro, Vermont; Central Vermont Medical Center, Barre, Vermont; Copley Hospital, Mor-risville, Vermont; Gifford Medical Center, Randolph, Vermont; North Country Hospital, Newport, Vermont; Northeastern Vermont Regional Hospital, St Johnsbury, Vermont; Northwestern Medical Center, St Albans, Ver-mont; Porter Medical Center, Middlebury, VerVer-mont; Rutland Regional Medical Center, Rutland, Vermont; Southwestern Vermont Medical Center, Bennington, Vermont; Springfield Hospital, Springfield, Vermont; Vermont Children’s Hospital at Fletcher Allen Health Care, Burlington, Vermont.

We thank the team members at the 12 Vermont hospitals for their voluntary participation in this study, which made this research possible. We thank Rachael Beddoe and Mary Ingvoldstad for work as the study data abstractors, Joseph Carpenter for assistance with devel-opment of the chart-auditing tool, Gary Badger for as-sistance with data analysis, and Lewis First for support of this work.

REFERENCES

1. Hagan JF Jr, Coleman WL, Foy JM, et al. The prenatal visit.

Pediatrics.2001;107:1456 –1458

2. Kogan MD, Alexander GR, Jack BW, Allen MC. The association between adequacy of prenatal care utilization and subsequent pediatric care utilization in the United States.Pediatrics.1998; 102:25–30

3. Serwint JR, Wilson MEH, Vogelhut JW, Repke JT, Seidel HM. A randomized controlled trial of prenatal pediatric visits for urban, low-income families.Pediatrics.1996;98:1069 –1075 4. Schanler RJ, O’Connor KG, Lawrence RA. Pediatricians’

prac-tices and attitudes regarding breastfeeding promotion. Pediat-rics. 1999;103(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/ content/full/103/3/e35

5. American Academy of Pediatrics; American College of Obste-tricians and Gynecologists.Guidelines for Perinatal Care.5th ed. Elk Grove Village, IL: American Academy of Pediatrics; 2002: 24 –25

6. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Fetus and Newborn. Hospital stay for healthy term newborns.Pediatrics.

2004;113:1434 –1436

7. National Committee for Quality Assurance. Commercial HEDIS 2002 audit means, percentiles and ratios. Available at: http://web. ncqua.org/Default.aspx?tabid⫽494. Accessed July 7, 2007 8. Braveman P, Egerter S, Pearl M, Marchi K, Miller C. Early

discharge of newborns and mothers: a critical review of the literature.Pediatrics.1995;96:716 –726

9. Margolis LH. A critical review of studies of newborn discharge timing.Clin Pediatr (Phila).1995;34:626 – 634

10. Meara E, Kotagal UR, Atherton HD, Lieu TA. Impact of early newborn discharge legislation and early follow-up visits on infant outcomes in a state Medicaid population. Pediatrics.

2004;113:1619 –1627

11. Datar A, Sood N. Impact of postpartum hospital-stay legislation on newborn length of stay, readmission, and mortality in Cal-ifornia.Pediatrics.2006;118:63–72

12. Galbraith AA, Egerter SA, Marchi KS, Chavez G, Braveman PA. Newborn early discharge revisited: are California new-borns receiving recommended postnatal services? Pediatrics.

2003;111:364 –371

13. Madden JM, Soumerai SB, Lieu TA, Mandl KD, Zhang F, Ross-Degnan D. Effects on breastfeeding of changes in mater-nity length-of-stay policy in a large health maintenance orga-nization.Pediatrics.2003;111:519 –524

14. Wall TC, Brumfield CG, Cliver SP, Hou J, Ashworth CS, Norris MJ. Does early discharge with nurse home visits affect ade-quacy of newborn metabolic screening? J Pediatr.2003;143: 213–218

15. Bordley WC, Margolis PA, Lannon CM. The delivery of immu-nizations and other preventive services in private practices.

Pediatrics.1996;97:467– 473

16. Taylor JA, Darden PM, Slora E, Hasemeier CM, Asmussen L, Wasserman R. The influence of provider behavior, parental characteristics, and a public policy initiative on the immuniza-tion status of children followed by private pediatricians: a study from Pediatric Research in Office Settings.Pediatrics.1997;99: 209 –215

17. Chung PJ, Lee TC, Morrison JL, Schuster MA. Preventive care for children in the United States: quality and barriers.Annu Rev Public Health.2006;27:491–515

18. Horbar JD, Plsek PE, Leahy K. NIC/Q 2000: establishing habits for improvement in neonatal intensive care units. Pediatrics.

2003;111(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/ full/111/4/e397

19. Margolis PA, Lannon CM, Stuart JM, Fried BJ, Keyes-Elstein L, Moore DE Jr. Practice based education to improve delivery systems for prevention in primary care: randomised trial.BMJ.

2004;328:388 –392

20. Young PC, Glade GB, Stoddard GJ, Norlin C. Evaluation of a learning collaborative to improve the delivery of preventive services by pediatric practices.Pediatrics.2006;117:1469 –1476 21. Shaw JS, Wasserman RC, Barry S, et al. Statewide quality im-provement outreach improves preventive services for young chil-dren.Pediatrics. 2006;118(4). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/ cgi/content/full/118/4/e1039

22. Kilo CM. Improving care through collaboration. Pediatrics.

1999;103(suppl):384 –393

through Series—IHI’s Collaborative Model for Achieving Break-through Improvement. Available at: www.ihi.org/IHI/Results/ WhitePapers/TheBreakthroughSeriesIHIsCollaborativeModel for Achieving⫹BreakthroughImprovement.htm. Accessed July 7, 2007

24. University of Vermont College of Medicine. Vermont Child Health Improvement Program. Available at: www.vchip.org. Accessed December 20, 2006

25. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine. Recommendations for preventive pedi-atric health care.Pediatrics.2000;105:645– 646

26. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious Dis-eases. Recommended childhood and adolescent immunization schedule: United States, 2005.Pediatrics.2005;115:182 27. American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Breastfeeding.

Breastfeeding and the use of human milk.Pediatrics.2005;115: 496 –506

28. American Academy of Pediatrics, Subcommittee on Hyperbil-irubinemia. Management of hyperbilirubinemia in the new-born infant 35 or more weeks of gestation.Pediatrics.2004;114: 297–316

29. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Genetics. Newborn screening fact sheets.Pediatrics.1996;98:473–501 30. Joint Committee on Infant Hearing; American Academy of

Audiology; American Academy of Pediatrics; American Speech-Language-Hearing Association; Directors of Speech and Hearing Programs in State Health and Welfare Agencies. Year 2000 position statement: principles and guidelines for early hearing detection and intervention programs.Pediatrics.

2000;106:798 – 817

31. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on

Environmen-tal Health. EnvironmenEnvironmen-tal tobacco smoke: a hazard to children.

Pediatrics.1997;99:639 – 642

32. American Academy of Pediatrics, Task Force on Infant Sleep Position and Sudden Infant Death Syndrome. Changing con-cepts of sudden infant death syndrome: implications for infant sleeping environment and sleep position.Pediatrics.2000;105: 650 – 656

33. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Injury and Poison Prevention. Safe transportation of newborns at hospital discharge.Pediatrics.1999;104:986 –987

34. American Academy of Pediatrics, Task Force on Violence. The role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention in clinical practice and at the community level. Pediatrics. 1999;103: 173–181

35. American Academy of Pediatrics, Ad Hoc Task Force on Defi-nition of the Medical Home. The medical home. Pediatrics.

1992;90:774

36. Langley GJ, Nolan KM, Nolan TW, Norman CL, Provost LP.The Improvement Guide: A Practical Approach to Enhancing Organiza-tional Performance. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1996 37. Krumholz HM, Herrin J. Quality improvement studies: the

need is there but so are the challenges.Am J Med.2000;109: 501–503

38. American Academy of Pediatrics, Committee on Infectious Dis-eases. Universal hepatitis B immunization.Pediatrics.1992;89: 795– 800

39. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. FDA licensure of diphtheria and tetanus toxoids and acellular pertussis ab-sorbed, hepatitis B (recombinant), and poliovirus vaccine com-bined (PEDIARIX) for use in infants.MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep.2003;52:203–204

BROWN’S MEDICAL SCHOOL GETS BIG GIFT

“Retail entrepreneur Warren Alpert’s foundation has donated $100 million to Brown University’s medical school in a major boost to the Ivy League insti-tution’s effort to expand the school. Brown, in Providence, RI, is renaming its medical school after Mr. Alpert in honor of the gift, the largest in the medical school’s history. University and foundation officials plan to announce the donation today. . . . Universities have seen a surge in gifts of $100 million or more in recent years. The largest gift to a US university was a $600 million donation to the California Institute of Technology in 2001 from Intel Corp cofounder Gordon Moore and his wife, Betty.”

DOI: 10.1542/peds.2007-0233

2007;120;481-488

Pediatrics

Horbar, Richard C. Wasserman, Patricia Berry and Judith S. Shaw

Charles E. Mercier, Sara E. Barry, Kimberley Paul, Thomas V. Delaney, Jeffrey D.

Collaborative, Hospital-Based Quality-Improvement Project

Improving Newborn Preventive Services at the Birth Hospitalization: A

& Services

Updated Information

http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/120/3/481

including high-resolution figures, can be found at:

References

http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/120/3/481#BIBL

at:

This article cites 31 articles, 26 of which you can access for free

Citations

s

http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/120/3/481#otherarticle

This article has been cited by 4 HighWire-hosted articles:

Subspecialty Collections

n

http://www.pediatrics.org/cgi/collection/premature_and_newbor

Premature & Newborn

following collection(s):

This article, along with others on similar topics, appears in the

Permissions & Licensing

http://www.pediatrics.org/misc/Permissions.shtml

tables) or in its entirety can be found online at:

Information about reproducing this article in parts (figures,

Reprints

http://www.pediatrics.org/misc/reprints.shtml