A Sociolinguistic Survey of the

Adara of Kaduna and Niger

States, Nigeria

Luther Hon, Grace Ajaegbu,

of Kaduna and Niger States, Nigeria

Luther Hon, Grace Ajaegbu, Carol Magnusson, Uche S. Nweke, and Zachariah Yoder

SIL International

®2018

SIL Electronic Survey Report 2018-004, March 2018 © 2018 SIL International®

The survey team visited the Adara language group of Kachia, Kajuru and Paikoro Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Kaduna and Niger States in Nigeria, from March 1 to March 16, 2011. The team did not visit Muya LGA because the dialect spoken is the same as the one spoken in Paikoro LGA. The Adara people are commonly called Kadara, especially by outsiders. They are known to speak dialects of the Kadara language. The dialects are Adara [kad], Ada [kad], Eneje [kad], Ajiya [idc] and Ekhwa [ikv]. The main goal of the survey was to determine the most suitable dialect(s) that all speakers of Adara

understand and accept as the best for a standard written form of Adara that would serve all of them. The survey team tested for intelligibility, interviewed different people and groups, gathered words for checking lexical similarity and asked the people about their potential support of a language project.

This survey would not have been possible without the support of many people throughout the language area surveyed. We express our profound gratitude firstly to the paramount ruler, His Royal Highness, the Agom-Adara,1 Mr Maiwada Galadima (JP2), who permitted us to go into the villages of the Adara people to do our work. We also express our appreciation to the various district, village and family heads who mobilized their people to participate in the survey process.

We appreciate the time and energy of those who volunteered to help us in eliciting the wordlists from the five Adara varieties, those who narrated the stories used for testing dialect comprehension, as well as the pastors, other church leaders and teachers who, in spite of their tight schedules, responded patiently to the questions on our interview forms.

1 The literal translation from the Adara language means “chief person” or more likely “chief of the Adara people.” Agom means ‘chief’ and Adara means ‘person’.

iv

1.2.5

Agriculture and economic/commercial units

1.2.6

Health care services

1.2.7

Religious profile

1.2.8

Estimated population

1.3

Goals

2

Language identification

2.1

The dialects that the Adara people speak in their area

2.2

Dialect relatedness

2.3

Summary of language identification

3

Social interaction

3.1

Intermarriage between the Adara [Kadara] people

3.2

Interaction with neighboring language groups

3.3

Church networks and Christian associations in the Adara [Kadara] language area

3.4

Government officials in the area

3.5

Local development associations

3.6

Economic/commercial units

4

Language vitality

4.1

Children’s language use

4.2

The domains where Adara is primarily spoken

4.3

The Adara [Kadara] groups who mainly speak the local language without mixing with Hausa

4.4

The language that the people mostly use in rural and urban areas

4.5

The people’s perception of their language

4.6

The people’s attitudes towards the shift and death statuses of their language

4.7

The Adara [Kadara] people’s attitudes towards languages of wider communication

4.8

Summary of language vitality

5

Language acceptability

5.1

The dialect(s) that people are willing to read and write in

5.2

Most acceptable dialect that might be used as a standard written form for all Adara people

5.3

The languages that literature is available in

5.4

Summary of language acceptability

6

Intelligibility

6.1

The dialect(s) that the people are reported to understand

6.2

Recorded text testing

6.3

Summary of intelligibility

7

Bilingual proficiency/language use

7.1

Other languages spoken by the Adara [Kadara] people

7.2

Neighboring languages spoken fluently by the Adara [Kadara] people

7.3

Language spoken by each segment of the Adara [Kadara] society

7.4

Where these languages are learned

8 Contact patterns

8.1 Interaction among speakers of the dialects 8.2 Local development associations

8.3 Church networks and Christian associations in the Adara [Kadara] language area

9 Literacy

9.1 The age group(s) that can read and write

9.2 The language(s) that each age group can read and write well 9.3 The best medium to serve the Adara [Kadara] people

9.4 Summary of literacy

10 Church support

10.1Church leaders’ feelings about language development 10.2The people’s desire for materials in their language

10.3The people’s ability to work together and support a language project 10.4Summary of church support

12.2Adara [Kadara] dialects for which people can score above 75 percent on RTT

vi

Table 1. Names of villages visited and the dialects spoken in each Table 2. Names of markets and market days

Table 3. Percentage of Adara [Kadara] language speakers per LGA Table 4. Names of dialects and alternate names

Table 5. Where wordlists were elicited and checked Table 6. Comparing words for ‘medicine’

Table 7. Lexical similarity percentage

1

The purpose of the Adara survey was to elicit data that would assist the Adara people and interested organizations that are involved in language development to identify which of the dialects of the Adara language group of the southern parts of Kaduna and Niger States of Nigeria is most suitable and accepted by the people for a standard written form of the Adara language. The survey team visited the Adara language group of Kachia, Kajuru, and Paikoro Local Government Areas (LGAs) of Kaduna and Niger States in Nigeria, from March 1 to March 16, 2011.

The Adara people are commonly called Kadara, especially by outsiders. They are known to speak dialects of the Kadara language. The dialects surveyed are Adara dialect [kad], Ada [kad], Eneje [kad], Ajiya [idc] and Ekhwa [ikv]. Note that there are two meanings of Adara used in this report, “Adara dialect” and “Adara language.” One dialect of the Adara language is also called Adara. Therefore, in this report, we will be referring to this dialect as “the Adara dialect,” the whole language as “the Adara language” and the people as “the Adara people.” We will use Kadara in square brackets after Adara when referring to the language and the people, for example: “Adara [Kadara] language” and “Adara [Kadara] people.”

Map of the Adara area

© 2016 OCHA ROWCA, through Ngandu Kazadi Bruno-Salomon, the Information Management Officer, United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, Nigeria – 15, Mississippi Street, Maitama, Abuja. Adapted by John Muniru (used QGIS, free mapping software). Used with permission.

1.1 Previous research/background information

However, he maintains that the actual settlements of the speakers in these three places are not known. Dancy and Gray, in their survey report of 1966, state that the language is spoken north of Abuja and north-east of Minna, while Crozier and Blench (1992:62) report that the speakers of Adara [Kadara] are located in Kachia LGA of Kaduna State and in the former Chanchaga LGA, now Paikoro and Muya LGAs of Niger State.

Temple writes that Hausa is generally understood by the Adara [Kadara] speakers (1919:180). Dancy and Gray say that most young and a few older people speak Hausa (1966:2). Temple also maintains that the Adara [Kadara] speakers in Fuka also speak Gbagyi (1919:180). Gunn feels that the people may be assimilating into the culture and language of other groups in these areas (for example Gbari, Koro and Ganagana) (1956:123).

Three wordlists were collected over the years: the Swadesh one hundred-item wordlist that was collected in 1966 by Dancy and Gray; John Ballard’s list of Adara words as incorporated into the Benue Congo Comparative wordlist by Williamson (1973:lxi); and another recent set in 2004̵̵̵–2006 of the Adara [Kadara] language group by Alex Maikarfi with Roger Blench (Maikarfi 2006).

1.2 Social setting

1.2.1 Adara administrative setting

The Adara language speakers are headed and guided by a paramount ruler, His Royal Highness, the Agom-Adara, and other senior title holders. There are also lower chiefs, village heads and their assistants who are answerable to the paramount ruler. The palace serves as a place where the speakers of the various dialects of the Adara language meet and interact with each other.

1.2.2 Adara villages

The Adara have many villages but we were only able to visit a few where we did our work. Each village that we visited has a village head who looks over all affairs and reports to the district head who may be living in a separate village. The villages that we visited are tabulated here with the dialect that is spoken in each:

Table 1. Names of villages visited and the dialects spoken in each

Village Dialect

1.2.4 Intermarriage

The Adara people intermarry mainly among the Adara language group and with the Kuturmi, Kamatan, Ikulu and Jabba people.

1.2.5 Agriculture and economic/commercial units

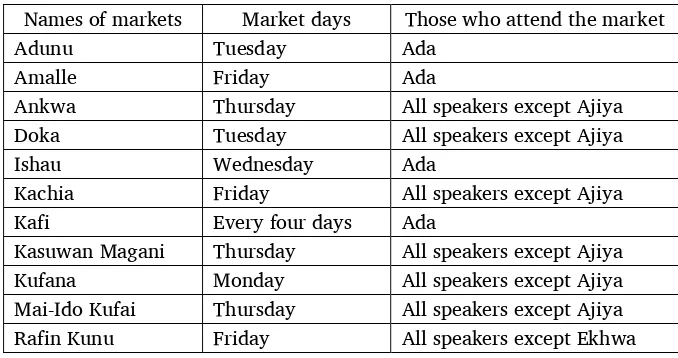

The Adara people are mostly subsistence farmers who grow maize, guinea corn, yams, groundnuts, cassava, sweet potatoes, millet, rice, soya, cocoyams, ginger, and sugar cane. They have many markets in the area where some of the produce is offered for sale on market days. The markets are attended

according to the days shown in table 2. Most of these markets provide opportunities for speakers from the different dialects to meet each other.

Table 2. Names of markets and market days

Names of markets Market days Those who attend the market

Adunu Tuesday Ada

Amalle Friday Ada

Ankwa Thursday All speakers except Ajiya

Doka Tuesday All speakers except Ajiya

Ishau Wednesday Ada

Kachia Friday All speakers except Ajiya

Kafi Every four days Ada

Kasuwan Magani Thursday All speakers except Ajiya

Kufana Monday All speakers except Ajiya

Mai-Ido Kufai Thursday All speakers except Ajiya

Rafin Kunu Friday All speakers except Ekhwa

1.2.6 Health care services

We came across some good looking structures that were said to be designed to serve as either hospitals or clinics in some of the villages that we visited, but most of them were reported and observed not yet in use. In fact, while we were working at Ankwa, a pregnant woman was about to give birth but because the clinic in the village was neither equipped with facilities nor personnel, she had to be rushed in our car to the hospital in the main town, Kachia, where the general hospital is located. The situation was a little better at Rafin Kunu where we came across a maternity home where two women were reported to be the only staff.

1.2.7 Religious profile

There are Christian churches of different denominations (see section 3.3) in the area. The population of Christians is estimated at 66 percent while the Muslim population is estimated at 7 percent and the African traditional religionists were also estimated at 7 percent.

1.2.8 Estimated population

Table 3 presents the 2006 national population census figures of the four LGAs in Kaduna and Niger States where the Adara [Kadara] language speakers predominantly live. In order to find out the present population of Adara [Kadara] language speakers in these LGAs, we asked a colleague about the

appear in table 3. The population in Kaduna and Niger States between 2006 and 2011 increased

annually by an estimate of 3.0 percent and 3.4 percent respectively (Federal Republic of Nigeria, 2007). We used the 2006 figures and the estimated annual growth rate percentages together to calculate the population in the four LGAs in 2011. We used the percentages of Adara [Kadara] speakers as they were given to us by our colleague to determine the estimated population in each of the LGAs for 2011. In conclusion, we estimate the population to be almost 300,000.

Table 3. Percentage of Adara [Kadara] language speakers per LGA

Census

We gathered data primarily based on these goals:

• To identify Adara dialects and their linguistic relationship.

• To determine whether the speakers of the dialects understand each other.

• To determine which dialect is central and would be the best choice for all Adara literature. • To determine whether the Adara are shifting to speaking primarily another language or if Adara

is still their primary language.

• To determine whether the local church would support language development and literacy work. The field work for this survey was done from March 1 to 16, 2011.

The field surveyors elicited data in ten villagesː Kurmin Kare (Ovah),3 Sabon Gari Ankwa, Barga, Mai Ido Rafi (Ivlo), and Ankwa villages in Kachia Local Government Area (LGA) of Kaduna State; we also collected data in Rubu, Rafin Kunu and Tudu Iburu in Kajuru LGA of Kaduna State and in Barakwai and Amalle of Paikoro LGA of Niger State (see map). We chose these three LGAs because that is where the five dialects of the Adara [Kadara] language are spoken. We did not choose to work in Muya LGA because the dialect in Muya is the same as the one spoken in Paikoro LGA.

2 Language identification

2.1 The dialects that the Adara people speak in their area

The people of the villages that we visited reported that five Adara dialects are spoken in the area: Adara dialect, Ada, Ajiya, Ekhwa and Eneje. However the respondents did not know the dialect names that the speakers of each dialect used for their dialects. The speakers of each dialect could easily identify each

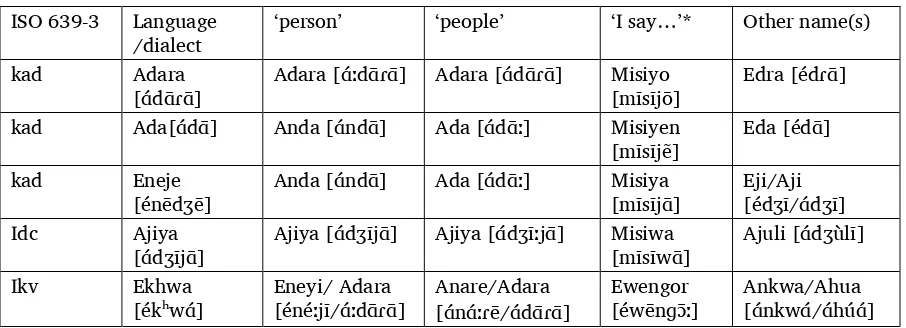

other by their different ways of expressing the emphatic phrase: ‘I say…’ in their respective dialects (see table 4).

Table 4. Names of dialects and alternate names

ISO 639-3 Language

[ɑ́dʒījɑ̄] Ajiya [ɑ́dʒījɑ̄] Ajiya [ɑ́dʒīːjɑ̄] Misiwa [mīsīwɑ̄] Ajuli [ɑ́dʒùlī]

Ikv Ekhwa

[ékʰwɑ́]

Eneyi/ Adara

[énéːjī/ɑ́ːdɑ̄ɾɑ̄] Anare/Adara [ɑ́nɑ́ːɾē/ɑ́dɑ̄ɾɑ̄] Ewengor [éwēnɡɔ̄ː] Ankwa/Ahua [ɑ́nkwɑ́/ɑ́húɑ́] *These phrases, which mean ‘I say…’ are used for identification of each other by all speakers.

His Royal Highness, the Agom-Adara, told us that the name or term Kadara is the Hausa term for the name Adara, which means ‘people’. Furthermore, many respondents reiterated the Agom-Adara’s claim during the group interviews. Contrastingly, an elderly man who is a speaker of the Ajiya dialect said Kadara, as written by previous researchers, was the original name. He maintained that Adara referred only to the speakers of the Adara dialect.

2.2 Dialect relatedness

Our respondents for group and individual interviews in Rubu, Barga, Rafin Kunu, Barakwai, Kurmin Kare and Mai Ido Rafi reported that all the dialects (and their speakers) are linguistically, socially and

culturally related but that the Ekhwa and Ajiya dialects have a high degree of linguistic variation from the other three dialects.

Speakers of the Adara, Ada and Eneje dialects whom we interviewed reported that they speak the same as each other, but with lexical and phonological variations. On the other hand, the Ekhwa and Ajiya people were reported by the other groups to speak very different dialects (see lexical similarity results in section 12.1).

2.3 Summary of language identification

The people identified their language as Adara [Kadara] and the dialects as Adara dialect, Ada, Eneje, Ajiya, and Ekhwa. But they simply refer to each other by the emphatic phrase ‘I say…’ in their language. However, speakers of Adara dialect, Ada, and Eneje say they understand each other, but do not

understand either Ekhwa or Ajiya.

3 Social interaction

3.1 Intermarriage between the Adara [Kadara] people

3.2 Interaction with neighboring language groups

The Adara language speakers co-exist happily with the Kuturmi, Kamatan, Ikulu, Gbari, Gbagyi, Jabba, Koro, Fulani and Ganagana people groups. They go to the same markets, farming areas, churches, mosques and schools. They also intermarry and are at peace with each other.

3.3 Church networks and Christian associations in the Adara [Kadara] language area

There are many churches of various denominations working with each other. The churches are:

Evangelical Church Winning All (ECWA); Catholic; Baptist; Maranatha; Assemblies of God; Deeper Life; Chapel of Good News; Anglican; Seventh Day Adventist; Chapel of Grace; Methodist; and Living Faith. Furthermore, many Adara [Kadara] people attend ECWA and Catholic churches because they are the two big denominations that are found in many villages in the area. Also, there are a few subgroups in each church working hand in hand with the leadership. These include the women’s fellowship, youth fellowship, choir, and Boys and Girls Brigades. These subgroups from the various denominations bring the speakers of the various dialects together during inter-church group or association programs. The Christian Association of Nigeria (CAN) is the large fellowship umbrella and the forum that brings all the churches and the speakers of the various dialects together, through its regular general meetings.

3.4 Government officials in the area

The Adara [Kadara] language speakers are headed and guided by His Royal Highness, the Agom-Adara, and other senior title holders. There are also lower chiefs, village heads and their assistants who are answerable to the paramount ruler. The palace of His Royal Highness, the Agom-Adara, in Kachia town serves as a place where the speakers of the various varieties of the Adara language meet and interact with each other.

3.5 Local development associations

The interviewees reported that there is an Adara Development Association at the village, state and national levels. The Adara [Kadara] people, at home and abroad, come together every year to celebrate their cultural festival named Adara Day and to discuss the way forward for the entire Adara language group. There is also an association called the Akpazuma (in the Adara dialect) or Akpazwã (in the Ada dialect). Each dialect group is said to have their own Akpazuma which draws people together to discuss the problems and progress of their own community.

3.6 Economic/commercial units

There are many markets in the area. The markets are held on specific days as earlier indicated in section 1.2.5. These markets provide opportunities for speakers from the different dialects to meet each other.

4 Language vitality

4.1 Children’s language use

4.2 The domains where Adara is primarily spoken

Adara seems to be the language most often spoken in the home domain. The people reported and were observed speaking the Adara [Kadara] language in their homes with all age categories: parents with children, grandparents with grandchildren, wives with husbands and brothers with sisters. The Adara [Kadara] language was said to be mainly spoken during hunting, on the farm and at play with age-mates and friends in school during the recess.

4.3 The Adara [Kadara] groups who mainly speak the local language without mixing with Hausa

The age groups in each village that we visited reported—and we observed—that they mainly spoke their language among themselves. Even so, Ekhwa speakers in Sabon Gari Ankwa seemed to use Hausa loan words. They also use complete Hausa clauses in long discussions.

4.4 The language that the people mostly use in rural and urban areas

In the villages that we visited it was reported—and we observed—that the people use their own dialects of Adara [Kadara] in all non-formal domains. We also observed some use of Hausa in all of the villages we visited. It was reported—and we observed—that Hausa was mostly used in the towns. Curiously, in Katari, a big town of the Ada speakers, a few people of all age groups were observed speaking the Ada dialect at the houses near the palace. This indicates that the desire to maintain the Ada dialect is strong; despite the contact they have with Hausa speaking outsiders, they still maintain their language.

4.5 The people’s perception of their language

The people in the villages we visited said that everyone in their villages speaks their Adara [Kadara] dialect. They said their children start learning this language first before any other language. They also said that a few of their non-Adara neighbors, both adults and children, also learn to speak their

language. Furthermore, they reported that they use their language in all domains, except with non-Adara [Kadara] speaking outsiders. Contrary to Gunn’s 1956 view that the Adara [Kadara] people are

assimilating other cultures and languages (see section 1.1), the Adara [Kadara] language is very much in use, despite the general use of Hausa in their areas.

4.6 The people’s attitudes towards the shift and death statuses of their language

The people we interviewed in the villages we visited responded both in the group and in the individual interviews that they would never be happy if their language was diminishing or dying. The group in Barakwai expressed strong optimism that the Adara [Kadara] language would never diminish or die and they maintained that “even the unborn generation would continue to speak the Adara [Kadara]

language.” The group in Ankwa felt that the diminishing or death of the Adara [Kadara] language would amount to throwing away their heritage and culture.

4.7 The Adara [Kadara] people’s attitudes towards languages of wider communication

and economic advantage. It appears that English is desired because of its perceived advantage while Hausa is used because it is widely spoken in the Adara [Kadara] language area.

4.8 Summary of language vitality

Adara is the language of every home, particularly in the rural areas. Children speak it with each other and their parents, and all adults speak it in all domains. The speakers expressed strong positive attitudes towards the maintenance of their language.

5 Language acceptability

5.1 The dialect(s) that people are willing to read and write in

The information gained from the questionnaires, interviews and the participatory method of data gathering showed that most people would choose the Adara dialect as the dialect that should be developed for all the Adara [Kadara] people to read and write in. Their second choice would be Ada, followed by Eneje. Furthermore, the answers showed that the speakers of Ekhwa and Ajiya would also choose the Adara dialect. However, the intelligibility and lexical similarity results showed that Ajiya and Ekhwa are separate languages both from the other three dialects and from each other and would benefit from separate development.

5.2 Most acceptable dialect that might be used as a standard written form for all Adara people

The groups and individuals that we interviewed would choose Adara as the main dialect that could be used for all the Adara [Kadara] people to read and write in. Adara was also chosen as the dialect that could be used for all the Adara [Kadara] people to read and write in during the facilitation of the participatory method of data gathering. The groups gave reasons that, “everyone understands the tongue,” “they [Adara dialect speakers] are the majority,” “it is central and easy” and “it is like the general one.” The groups in Barga (Eneje) and Sabon Gari Ankwa (Ekhwa) chose Ada and Eneje

respectively. This choice could have been made because of the proximity between Ekhwa, Ada and Eneje villages. The group in Barga felt that Ada was “pure, no adulteration.”

5.3 The languages that literature is available in

Hausa and English literature is available throughout the Adara [Kadara] language area. The expressed feelings of the groups and individuals interviewed seemed not to be very favorable to literature in Hausa or English.

5.4 Summary of language acceptability

Adara speakers we worked with chose Adara dialect for development because it is central to the other dialects and easily understood by everyone. The speakers believe that it is the only dialect that could unite them.

6 Intelligibility

6.1 The dialect(s) that the people are reported to understand

speakers of Adara dialect also said that they understand a bit of the Ajiya dialect. Only Ekhwa speakers claimed to understand all the dialects.

6.2 Recorded text testing

We used the recorded text testing (RTT) method to directly measure the intelligibility between the Adara dialects. Generally, if results are lower than 75 percent on an intelligibility test, separate literature needs to be developed (SIL 1991). However, if the results are 75 percent or greater, other factors need to be considered before we can be sure that literature can be understood by speakers of two or more dialects. The results indicate that:

• Each of the five groups scored above 90 percent on its own text.

• Eneje speakers scored 100 percent on the Adara dialect text and 96 percent on the Ada text. • Ada speakers scored 75 percent on the Adara dialect text and 70 percent on the Eneje text. • Adara dialect speakers scored 75 percent on the Eneje text and 66 percent on the Ada text. • Adara dialect, Ada and Eneje speakers scored very low on the Ekhwa’s text and Ekhwa speakers

also scored very low on texts from these dialects.

6.3 Summary of intelligibility

The Adara text was easily understood by Eneje speakers and marginally (75 percent) by the Ada

speakers. This implies that Adara may serve the three dialects. Also, the Ada story was easily understood by Eneje speakers, but the Adara speakers scored an insufficient score of 66 percent.

Ekhwa and Ajiya speakers did understand the Adara, Ada and Ekhwa texts; however, they achieved a low score on the three texts.

7 Bilingual proficiency/language use

7.1 Other languages spoken by the Adara [Kadara] people

Besides speaking their own dialect of Adara [Kadara], almost every person in the villages that we visited was reported and observed to speak Hausa to some level. English was also reported to be spoken well by just a handful of individuals who have acquired higher Western education in the area. Furthermore, a few people were said to speak Kuturmi, Jabba, Kamatan, Ikulu, Gbagyi or Koro.

7.2 Neighboring languages spoken fluently by the Adara [Kadara] people

None of the neighboring languages mentioned in sections 3.2 and 7.1 was reported in the group and individual interviews to be spoken fluently by the Adara [Kadara] people. Some people are reportedly able to speak a bit of some of the languages. A few children and women were said to speak Kuturmi quite well.

7.3 Language spoken by each segment of the Adara [Kadara] society

All segments of the Adara [Kadara] society speak the local language fluently in all domains. The youth are said to be the primary speakers of Hausa in the region. Many middle-aged people and children are also said to speak Hausa but not as well as the young people, while most old people are said to speak just a bit of it.

7.4 Where these languages are learned

A child learns his/her dialect in the home and we observed its use everywhere in the village.

Furthermore, the people reported that their children learn to speak Hausa from the children of strangers, particularly the Fulani, who live around all their villages. They said their children meet with other children in school and use Hausa as the common and easiest medium of communication between them (Hausa is taught as a subject in almost all schools in northern Nigeria). Also, teachers are said to occasionally instruct in Hausa whenever pupils appear not to understand concepts in English and other subjects.

English is the major language of school everywhere in Nigeria. Pupils in the Adara [Kadara] language group area are said to be encouraged to speak it while in class. In fact, a pupil may reportedly be punished for speaking Adara [Kadara] in class. However, we observed primary and secondary school children struggle mostly without success to respond to our questions in English. As a result, we did almost all our interviews in Hausa.

7.5 Summary of bilingualism

The people are mostly bilingual in Hausa and some of them, especially children, youth and middle-aged adults, speak English, and a few women and children speak Kuturmi quite well.

8 Contact patterns

This section has to do with how and where the Adara speakers meet with each other.

8.1 Interaction among speakers of the dialects

The Adara [Kadara] people are conscious of their oneness and reportedly men and women from the different dialects intermarry. Wives and husbands speak each other’s dialect or learn to speak them when necessary. Adara-Day, the cultural festival of all the Adara [Kadara] people, brings people together from Kaduna and Niger States. It is celebrated in the town of Kachia, where the palace and house of the paramount ruler are located. Kachia remains the primary place of convergence. Also, there are many markets in the various villages that we visited where the speakers of the various dialects meet.

8.2 Local development associations

The people reported that there is an Adara [Kadara] Development Association at the village, state and national levels. All the Adara [Kadara] people, at home and abroad, come together every year to celebrate their cultural festival named Adara-Day and to discuss the way forward for the entire Adara language group. There is also an association called the Akpazuma. Each dialect group is said to have its own Akpazuma which draws people together to discuss the problems and progress of their own

community.

8.3 Church networks and Christian associations in the Adara [Kadara] language area

9 Literacy

This section deals with the reading/writing ability of the people and the people’s access to education. It also deals with the kind of medium that would be most appropriate and the people’s attitudes towards the available literature in the area.

9.1 The age group(s) that can read and write

Many people reported in the group and individual interviews that they can read and write. The children, youth, and middle-aged people seem to be the most literate among all of them. Only a few old people are said to be able to read and write.

9.2 The language(s) that each age group can read and write well

The youth are said to read and write in Hausa and English, which they learn at school. Middle-aged people are also reported to be able to read and write in Hausa and English, but not as well as the youth. Only a few old people reported that they are able to read and write in Hausa or English. Only a handful of all the age categories are reported to be able to read and write letters and other notes in the Adara language.

9.3 The best medium to serve the Adara [Kadara] people

Books and audio-visual media seem to be the primary means that could be used to serve the Adara [Kadara] language group. The youth and children, who are the future of the Adara [Kadara] people, were reported during the group and individual interviews to prefer reading and watching TV to only listening to audio messages. Only a few middle-aged people were also reported to prefer reading, watching and listening to just listening to audio or radio messages.

9.4 Summary of literacy

The children, youth and middle-aged people are the most literate in English and Hausa in the area, although the youth and middle-aged were said to read and write better than the children. The people chose book and audio-visual mediums over merely listening to audio messages.

10 Church support

10.1 Church leaders’ feelings about language development

The church leaders interviewed in the Adara language group area expressed enthusiasm about the translation of materials into the local language. They said that if materials were translated into an Adara [Kadara] dialect, children and youth would learn how to read and write in it. Also, they reasoned that Adara [Kadara] language development would help maintain the mother tongue. The church leaders pledged to give their support and do awareness campaigns among the people should there be a language development project, so that everyone may support it in various ways.

10.2 The people’s desire for materials in their language

language but they did not. They further demonstrated their desire to see their language developed when they reported that they were ready to get involved in any kind of project that would lead to the

development of their language into a standard written form.

10.3 The people’s ability to work together and support a language project

During the interviews, it became apparent that the people’s ability to work together for their progress is remarkable. They said they had jointly built primary schools, classrooms, markets, roads to clinics, bridges, and dug wells in their various communities. We personally observed some of these projects.

10.4 Summary of church support

The people have demonstrated an ability to work together and potentially support language development and literacy work in their area. They also mentioned a few names of individuals who may be of

tremendous assistance in the cause of the prospective language development work.

11 Methodology

Following are the methods that we used to investigate the language situations in the Adara [Kadara] area.

11.1 Interviews

We visited ten villages. In one village from each dialect area (Adara dialect, Ada, Eneje and Ekhwa), we interviewed a group of forty individuals of both sexes and all ages. We also interviewed teachers and church leaders. We did not do individual interviews in any Ajiya village because we did not plan for it. We thought the Ajiya dialect was the same as the Adara dialect until we discovered during a group interview in Rubu village that Adara dialect speakers could not understand it.

11.2 Recorded text testing (RTT)

We did recorded text testing in each dialect area in order to ascertain mutual intelligibility between the speakers of the different dialects of the Adara [Kadara] language.

11.2.1 Test development and administration

First, short stories about an interesting event in the storyteller’s life were recorded in the vernacular in four dialects: Adara, Ada, Eneje and Ekhwa. Two more stories were recorded in the Eneje dialect, making the Eneje stories three. They were used to test for reliability of the RTT method. The stories were named “Eneje Love,” “Eneje Travel,” and “Eneje Farm.” The stories were about two to three minutes in length. These texts were transcribed, and then an English phrase-by-phrase free translation was made with key words glossed. For each of these texts, fifteen basic comprehension questions were created. No inferences or background knowledge were required in order to answer the questions correctly; the correct

responses were found in the texts themselves. The questions attempted to cover a wide range of semantic categories (e.g., who, what, when, where, how many, action, instrument, quotation, etc.) and were formed in such a way as not to be answerable on the basis of common knowledge alone. The texts were recorded on minidiscs, and track marks were inserted indicating points where comprehension questions should be asked.

of a language of wider communication (LWC) from the test results. However, experience has shown that subjects tend to find responding to questions coming from a machine extremely unnatural and rather confusing. Responding to a person asking questions is much more natural and eliminates this confusion from the testing situation. Hence, we verbally asked questions and did not insert the questions into the recording.

We administered the RTT by playing the text up to the point where a question should be posed, pausing the playback and then asking the subject the question. We asked the questions in English or Hausa, sometimes followed by a translation into the local dialect, provided by local interpreters. The subject responded in either the local dialect, Hausa, or English. The response was written down in English, Hausa or Adara. When appropriate, the tester would prompt to clarify if the subject understood that portion of the text. For example, if the subject responded with other elements of the story but not the answer sought by the question, the question was posed again or rephrased slightly. The tester, as well as the interpreter, had to take care not to give away the correct answer in their prompt questioning and interpreting. If there was some distraction during the playback of a portion of the text, such as loud noises, people talking, or the subject had a problem understanding the text the first time, the tester replayed that portion of the text. All such follow-up questions and replays were noted on the answer sheets.

Since the tester is working with a rough transcription of a text in an unfamiliar speech variety, it is possible that the questions devised will not coincide with the text or not appear to be logical to native speakers. The initial fifteen questions were pilot tested with ten speakers of the same speech variety as the story. Questions which elicited unexpected, wrong, and/or inconsistent responses from vernacular speakers were eliminated, and the ten best questions were retained for the final test.

11.2.2 Reliability of the RTT method

The professional term “reliability” means the state of dependability or similarity of test results if a test is repeated. To determine the reliability of the tests we used more than one text, each tested with speakers of other dialects. Thus, three Eneje texts were used to test with speakers of the Ada, Ekhwa, Ajiya, and Adara dialects. This was part of a larger study that included three other language areas besides Adara [Kadara] (Yoder 2014).

11.2.3 Subject selection

For the pilot test we found at least ten subjects of any age (most were young) and gender who were vernacular speakers of that dialect and who were willing to participate.

When administering the actual test, we tested people with as little contact with the other dialect as we could find. The guidelines for acceptable levels of inherent intelligibility are based on testing people with no contact with the other varieties. This is necessary to determine the inherent intelligibility of the test dialect as opposed to intelligibility acquired through contact. Pupils in primary school class 3 (P3) to junior secondary school class 3 (JSS3) were chosen as test subjects. Where possible, we tried to choose subjects in primary school classes P4–P6 or junior secondary school classes 1–3 (JSS1–JSS3). The students in this age range are old enough to have a good command of their own dialect but have not usually had many opportunities to visit other villages. Therefore, they are likely to be those with the least amount of contact with other dialects.

We selected a sample of twenty vernacular speakers of each dialect to listen to the texts. We chose two villages from each dialect area with the exception of Ajiya, and tested ten subjects from each of these villages. Related to the study of the reliability of the RTT, which we mentioned earlier, we selected a different sample of fifteen to twenty subjects each in three villages to listen to the three Eneje texts.

11.2.4 Testing procedure

gathering basic demographic information (age, sex, level of education), verifying that the subject was a vernacular speaker of the dialect of interest (mother and father were both from the dialect area), and screening for contact with the other dialects being tested (subject does not travel to one of the other dialect areas frequently or have close relatives from another dialect). With only a few exceptions (due to a shortage of subjects), all subjects met these criteria.

The second phase was a short practice test in the subject’s own dialect, which served to familiarize the subject with the testing procedure. The practice story was written out by a surveyor and then translated and recorded in order to save time on transcription and to make sure the story contained useful content. Four questions were created for this story. The test was not graded as part of the RTT. This was sometimes played twice if it appeared the subject was beginning to understand the procedure, but had not completely understood. This was done to screen out poor test takers.

The third phase was the hometown test. Each subject was tested using the text in their own dialect first, which served as a further screening procedure. If subjects could not score 85 percent on the test in their own dialect, they were judged incompetent to follow the testing procedure (or incompetent in their vernacular dialect) and no further testing was performed.

The final phase was administering the test in the dialects of interest. After passing the hometown test, each subject was tested on the three other stories. The order in which the other tests were played was rotated in order to avoid any effect on the average scores by testing-fatigue of the subject.

11.2.5 Scoring

For each text, the answers given by the vernacular speakers of that dialect were taken to be correct. Usually, the pilot testers gave consistent answers to each of the ten questions selected for the final test. Occasionally, there was a small range of related answers given by the pilot testers and/or the hometown subjects (e.g., “he is not grown enough” versus “he did not reach age”), and in this case, the entire range of these answers was considered a correct response. Sometimes, a subject would give a response that was partially correct (e.g., correct noun or object but incorrect action, such as: “rain wants to fall” instead of “rain fell”), and such responses were scored as half correct. During the analysis phase of this survey, every response was crosschecked for consistency in scoring.

11.2.6 Post-test questions

Immediately after hearing each story, each subject was asked a series of questions regarding that speech variety:

1. Is the way this man speaks the same as the way you speak, a bit different, or very different? 2. What language was he speaking?

3. How much of the story did you understand: all, most, some, little, or none? 4. Was he easy to understand: easy, not difficult, a bit difficult, not easy, difficult?

Carla Radloff (1993) found in a similar survey that the answers to questions like numbers 1 and 3 usually corresponded to intelligibility test results, which supported the tests’ conclusions. Moreover, where responses to these questions differed from the test results, they corresponded to strong attitudes (usually negative) towards the dialects in question. On this survey, question 4 allowed subjects to further clarify their response to question 3. Question 2 revealed whether the subject had had enough contact with the dialect that they had just heard to be able to identify it. Responses to all of these questions can indicate not only the information specifically asked for but also any strong language attitudes.

11.3 Wordlist

Wordlists were elicited to compare how similar the lexicons of each dialect of the area surveyed are to each other. A total of five wordlists (of five dialects) were elicited in five villages—two villages per dialect. The wordlist taken in village A was crosschecked in village B of the same dialect before proceeding to village C to collect a fresh wordlist in a different dialect. However, we did not check the Ajiya wordlist in a second village.

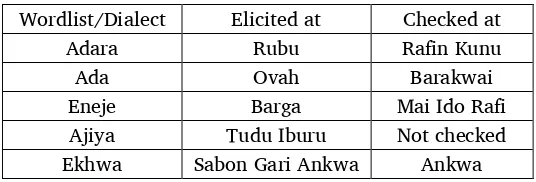

Table 5 below provides more explanation.

Table 5. Where wordlists were elicited and checked

Wordlist/Dialect Elicited at Checked at

Adara Rubu Rafin Kunu

Ada Ovah Barakwai

Eneje Barga Mai Ido Rafi

Ajiya Tudu Iburu Not checked

Ekhwa Sabon Gari Ankwa Ankwa

11.3.1 Wordlist elicitation

The wordlist was based on the one used in surveying the Fali of Mubi LGA, Adamawa State, Nigeria. We elicited a wordlist from a group of three or four residents in each village. The primary informants were males between eighteen and eighty years of age. In most villages onlookers (men and women) besides the primary informants were present during the elicitation. They helped decide which word was the most appropriate in cases where the gloss we elicited could have been expressed by more than one word in the local dialect. In some cases, the primary informant was not able to help with the entire wordlist, so a new person was sought and found from the group of people who were observing.

Wordlists were handwritten on a printed wordlist form, using the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). We elicited both singular and plural forms (where applicable) for nouns. Verbs were elicited in “dictionary form” and 3rd person singular past (or perfective) tense, for example: ‘eat’ and ‘he ate’. Adjectives were elicited both in isolation and with an example noun (e.g., ‘long’ and ‘long road’). For documentation purposes, audio recordings of all the words elicited were taken using a ZOOM Handy Recorder H2 recording device, recording singular and plural nouns and adjective and verb forms (both in isolation and in a frame).

All phonetic transcriptions tend to be influenced by the phonology of the transcriber’s language. The transcriptions were done by Carol Magnusson (American English) and Zachariah Yoder (American English). The wordlists were checked, usually by a different surveyor than the original elicitor and/or transcriber. Each word was re-elicited. Items different from the first transcriptions were re-transcribed and re-recorded in order to make each list as reliable as possible in the amount of time available for the survey.

11.3.2 Wordlist comparison

The 364 wordlist items were analyzed using WordSurv 6, a program that calculates the percentage of forms judged to be similar by surveyors. To judge similarity, we typically followed the methodology for comparison (Blair 1990:27–33). In this method, corresponding phones in two words to be compared are classified into three clearly defined categories. Words are only considered similar if at least half the phones in the words are category one (roughly “almost identical”) and no more than a quarter of the phones are category three (roughly “not similar”). For a more detailed explanation of this method, see Blair 1990:27–33.

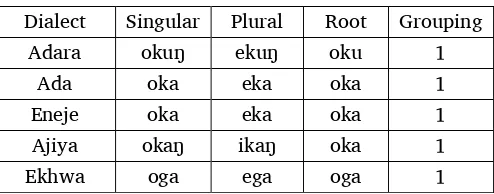

Table 6. Comparing words for ‘medicine’

Dialect Singular Plural Root Grouping

Adara okuŋ ekuŋ oku 1

Ada oka eka oka 1

Eneje oka eka oka 1

Ajiya okaŋ ikaŋ oka 1

Ekhwa oga ega oga 1

We first compare the root of all the dialects. When we match the first phones with the first, second with second, we see that Adara, Ada, Eneje, Ajiya and Ekhwa match similarly (so they are in category one). Since more than half of the phones of the two words are category one (in this case 2 out of 2) and less than a quarter are category three (0 out of 2) we conclude words are “similar” and include them in one group.

11.4 Observation

We also used the participant observation method (Spradley 1980) in order to investigate the general language use of the people we visited in each dialect area. Surveyors watched people’s activities and interaction among themselves and listened to the languages they used. Even while working with a group, the facilitators continued to observe how the people used their language and other languages.

11.5 Sampling

We randomly chose the respondents for individual interviews. We met them in informal places and interviewed them. For the RTT testing, we randomly chose a separate group of ten to twenty subjects who had little or no contact with speakers of other Adara dialects.

Our sample consisted of:

• Forty respondents each in Kurmin Kare (Ovah), Sabon Gari Ankwa, Barga, and Rubu for individual interviews.4

• Ten to twenty subjects in each dialect area who have little or no outside contact for the RTT testing.

11.6 Participatory method

We chose to use the participatory method because it allows speakers of a language to be part of the survey process in identifying the domains in which they use their language and other languages (particularly English and Hausa), and how often they use these languages in their community. The tool also helps speakers to identify their dialects and the names of the villages where their dialects are spoken. Using the tools they are also able to identify the dialects that are very similar to their own and those that are not. This tool is divided into two sections: domains of language use and dialect mapping.

(a) Domains of language use: We asked the speakers to write down the languages that they use in their community, the domain in which the languages are used and how often they use each language. This was done so that we could determine whether the people are still speaking their language or whether they have shifted to speaking another one.

(b) Dialect mapping: We asked the speakers to write down the name of their language, its dialects and the names of the villages where their dialects are spoken. Furthermore, we asked them to indicate dialects that are very similar and those that are a bit different. This was done in order to determine the dialect boundaries.

12 Results

12.1 Lexical similarity and interpretation

Blair’s lexical similarity judging standard states that if the results of a wordlist comparison between two speech varieties are greater than sixty percent, then the varieties should be regarded as “similar” and if otherwise “dissimilar” (1990:23–24).

In each of the five dialects we collected a wordlist of 364 items. In all but the Ajiya dialect, this list was re-elicited in a second village to verify that the correct words were transcribed correctly. Similar word forms were identified using the rules described by Blair (1990:27–33). The percentages of similar forms between dialects are shown in table 7.

Table 7. Lexical similarity percentage

From table 7, we can make the following observations:

• Ekhwa is a separate language from all the other dialects surveyed (less than 30 percent similarity).

• Ajiya is clearly a very different dialect from Adara dialect, Eneje, Ada, and Ekhwa (less than 35 percent similarity).

• Eneje is lexically the most central dialect, having higher similarity with the Adara dialect and Ada than these two have with each other.

• Eneje may be slightly more similar to Ada (70 percent) than to the Adara dialect (64 percent). • The Adara dialect has a rather low similarity with Ada (57 percent). It seems likely that speakers

of these dialects will have difficulty understanding each other.

12.2 Adara [Kadara] dialects for which people can score above 75 percent on RTT

Our original research question sought to determine which dialects speakers of other dialects could score above 75 percent on. Thus, any that cannot succeed in scoring higher than 75 percent are considered to have too low of an intelligibility to use audio or written materials developed in the tested dialect. With reference to section 11.2.3, regarding the question of the reliability of the RTT method, we played one text from each dialect5 to a sample of nine to eleven subjects in five villages, using the text “Eneje Love” to represent Eneje. These results are shown in table 8.

Table 8. Test site and recorded text testing percentage

Texts

Dialect Village Subjects Adara Eneje Love Ada Ajiya Ekhwa

Adara Rafin Kunu 11 96% 75%a 66% 4%

Eneje Mai Ido Rafi 10 100% 96% 96% 3%

Ada Barakwai 10 75% 70% 98% 6%

Ajiya Tudu Iburu 9 31% 23% 11% 97%

Ekhwa Ankwa 10 11% 30% 12% 96%

a If the eighth question is removed from the test, the Adara subjects score 79 percent on “Eneje Love.” The other site’s results do not change significantly if this question is removed.

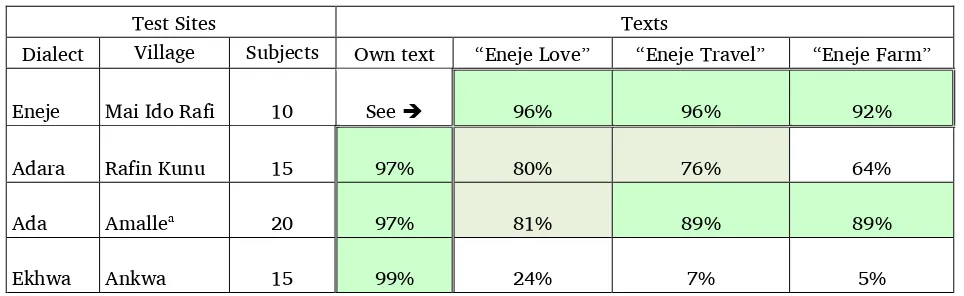

Then, using a different sample of fifteen to twenty subjects in three villages, we tested the three Eneje texts, with the results shown in table 9.

Table 9. Comparing three Eneje texts (different subjects)

Test Sites Texts

Dialect Village Subjects Own text “Eneje Love” “Eneje Travel” “Eneje Farm”

Eneje Mai Ido Rafi 10 See 96% 96% 92%

Adara Rafin Kunu 15 97% 80% 76% 64%

Ada Amallea 20 97% 81% 89% 89%

Ekhwa Ankwa 15 99% 24% 7% 5%

a We could not find more than ten subjects who could participate in the research in Barakwai, so we tested the three Eneje texts in a different Ada village.

These two tests did not yield the same results. As seen in table 8, only Eneje subjects were able to score significantly above 75 percent on any text besides their own. In fact, on average they were able to score above 95 percent on both the Adara and Ada dialect texts. The Adara and the Ada subjects did not get a mean score above 75 percent on the Eneje test. The difference may be due to Eneje speakers learning to understand the other varieties (acquired intelligibility; see the comment on contact in section 8.1 as well as the discussion in this section) or it may be that there is an asymmetric inherent intelligibility.

Considering the observations made earlier in this section, we can make inferences about which dialects are understood well by speakers of other dialects.

• Considering the low lexical similarity between Ekhwa and Ajiya (see table 7), and the subjects’ low comprehension of other dialects included in this survey, Ekhwa and Ajiya speakers would not be well served by literature in any dialect other than their own. Both Ekhwa and Ajiya dialects will need separate development.

• The Adara dialect text was understood well by Eneje subjects, and marginally (75 percent) by the Ada subjects. Perhaps it could serve all three.

• The Ada text was understood well by Eneje subjects, but the Adara dialect subjects achieved a score of 66 percent which is below the potential intelligibility threshold.

• The Eneje texts produced mixed results (see table 9). Depending on which text test result is considered and which village the subjects are from, the results could indicate that speakers of either Adara dialect or Ada score above 75 percent on Eneje or that speakers from both Adara dialect and Ada or even neither do. Using the more conservative results, we might question whether speakers of either Adara dialect or Ada can understand Eneje well.

13 Findings

The following are the findings of the survey.

We found out that five dialect groups claimed to speak the Adara language: Adara dialect, Ada, Eneje, Ekhwa, and Ajiya. However, lexical similarity comparisons and intelligibility text testing results indicate that Ekhwa and Ajiya are two separate languages. So, the dialects of the Adara language are Adara dialect, Ada and Eneje. Even so, the lexical similarity results indicate that Ada shares more similar words with Eneje (70 percent) than with the Adara dialect (57 percent). Adara, Ada and Eneje speakers reported that they understand the Adara dialect, and the intelligibility test results confirm that the Adara dialect is most understood. Eneje and Ada subjects scored 100 percent and 75 percent respectively on the Adara dialect text.

The Adara dialect is reportedly prestigious and most understood by all, just as indicated in the intelligibility results. These indicators are convincing enough to qualify Adara dialect as the central and best choice for Adara [Kadara] language literature.

Adara [Kadara] children speak their mother tongue in their homes and at play and they also speak Hausa as a second language. The Adara [Kadara] language is still the people’s primary language.

14 Conclusion and recommendation

Based on the lexical similarity, the intelligibility results and the interview responses of some individuals, it seems the Adara, Ada and Eneje dialects are similar and people of these dialect groups could possibly use the same literature. Furthermore, all the interviewees from these three dialects appeared to exhibit positive attitudes towards the Adara dialect as their preference for development. They feel that the Adara dialect is generally the best understood and easiest to learn among these dialects. In fact, even songs in the Adara dialect are reportedly understood and appreciated by the speakers of the other two dialects. Therefore, our first suggestion is that the Adara dialect should be developed to serve not only speakers of the Adara dialect but also those of the Eneje and Ada dialects.

Table 8 indicates that Eneje speakers understand the Adara dialect well, while Ada speakers may need some time to get used to it.

Since work in the Ada dialect is reportedly in progress, and it appears that Ada speakers may need some time to perfect their understanding of the Adara dialect, we make the alternative suggestion that the Ada dialect may also be developed alongside the Adara dialect. If the Ada dialect is developed, some Eneje speakers may prefer to use that instead of the Adara dialect.

21

Language village Ada Ovah Ada Barakwai

Date 02 March 2011 12 March 2011

Given language name Ada Ada‐Check

Given village name Ovah Barakwai

LGA Kachia Paikoro

State Kaduna Niger

Informant SB PA

Age 25 47

Sex M M

Reliability: good good

Elicited by: CM CM

Other Informanʦ: DG, 28, M DM, 49, M

Language (village) Ada (Ovah) Ada (Barakwai)

No. English Gloss Sg. Pl. / 3rd sg. Sg. Pl. / 3rd sg.

1 hair none unsɛɾɛcʷɛ əsɛɾɛcʷe unsɛɾɛcʷɛ

2 head ɛcʷɛ acʷɛ ɛcʷɛ acʷɛ

3 forehead mbɛkɛ umbɛkɛ mbɛkɛ umbɛkɛ

4 ear ɔːtɔŋ aːtɔŋ ɔːtɔŋ aːtɔŋ

5 mouth ɔːnu ɔːnu ɔːnu ɔːnu

6 tooth idʒri edʒɾi idʒri edʒɾi

7 tongue iːno iːno iːno iːno

8 saliva ɛkpɛ none ɛkpɛ none

9 sweat iːdo none iːdo none

10 chin ocʷo ocʷo ocʷo none

11 beard unfocʷo none unfocʷo none

12 nose uᵏpɛwɛ akpɛwɛ ukpelo akpelo

13 eye ijɛ ajɛ ɪridʒre ɪɾidʒ̠re

15 tear drop ajɛ none adɛn none

16 neck ɑnta anta ontoh antoh

17 shoulder obʷe ɑbʷe obʷige abʷige

19 belly ofo̚ ɑfo etuŋ none

20 navel iko nko iko none

21 stomach omofo ɑmɑfo aʲki none

22 intestines onɑ ænæ onɑ ænæ

24 knee uŋbun oŋbun uŋbun oŋbun

25 leg ofɾa afɾa ofɾa afɾa

26 foot apɛnpʰofɾa apampʰafɾa apɛnpʰofɾa apampʰafɾa

27 shoes opula aᵏpala opula aᵏpala

28 thigh okɾo akɾo okɾo akɾo

29 arm onʲe anʲe onʲe anʲe

31 finger eɾenje eɾenje eɾenje eɾenje

32 fingernail eŋbenje eŋbenje eŋbenje eŋbenje

33 skin eta eta etaŋ (none)

52 clothing onkʲoʃe onkʲotʃe onkʲoʃe onkʲotʃe

71 grass, dry õmbo kʷo ambo kʷo õmbo kʷo (none)

107 brother ewedʒim ewedʒim ewedʒim ewedʒim

108 sister afuwom afuwom afuwom afuwom

111 chief agoŋ agoŋ agoŋ agoŋ

112 friend onusɛm onusɛm onusɛm onusɛm

113 stranger oːsoŋ oːsoŋ oːsoŋ oːsoŋ

115 name ontuwa (none) ontuwa (none)

116 animal onijatʃa (none) oŋketɾaŋ (none)

118 pig ubusuɾum obusuɾum ubusuɾum obusuɾum

119 tail utʃi etʃi utɾi etɾi

122 fly ensuŋ ẽsisuŋ ensuŋ ẽsisuŋ

123 spider agiᵉ agiᵉ agiᵉ agiᵉ

124 mosquito evoh evoh evoh evoh

135 crocodile aːkwõ aːkwõ aːkwõ aːkwõ

137 chicken ãno ãno arano ãno

150 buffalo ɛkuwa ɛkuwa ɛkuwa ɛkuwa

151 elephant ɛnka ɛnka ɛnka ɛnka

154 hyena ɛkɾo õŋkɾo ɛkɾo õŋkɾo

155 dog ava ava ava ava

156 house/hut abaŋ abaŋ abaŋ abaŋ

157 room ũŋko õŋko ũŋko õŋko

158 fence ugbɛ̆lɛ egbɛ̆lɛ ugbɛ̆lɛ egbɛ̆lɛ

159 road/path õŋtʃãŋ ɛŋtʃãŋ õŋtʃãŋ ɛŋtʃãŋ

160 pit ukpo okpo ukpo okpo

161 farm (field) onum onum onum onum

162 at ko mabaŋ ko mabaŋ omabaŋ (de)

163 door anjatija atija anjatija atija

164 chair/stool ɛntɾetʃo ontʃɔtʃɔ ɛntɾetʃo ontʃɔtʃɔ

165 salt onija (none) onliga (none)

167 mortar otʃo otʃo utʃu otʃu

173 stone ɛntʃitʃe ontʃutʃə ɛntɾa ontɾotɾa

174 cave ukpote okpote ofopaʰ afapaʰ

193 canoe okpambɾe ekpambɾe okpambɾe ekpambɾe

194 bridge ɛndᶾɾə ondᶾɾə ɛndᶾɾə ondᶾɾə

195 water ambɾe (none) ambɾe (none)

196 lake uŋkpo oŋkpo uŋkpo oŋkpo

197 sky apɾemin (none) apɾemin (none)

198 moon opɾe apɾe opɾe apɾe

199 star eɾinkɛn oɾunkɛn eɾinkɛn oɾunkɛn

200 sun onːum (none) onːum (none)

201 year aːme aːme aːme aːme

202 morning otuɾəmbo (none) otuɾəmbo oturəmbo

276.13 he usually eat akaⁱja (na) aloⁱjə (na)

276.14 he didn't eat asojamma (na) asojamma (na)

276.5 do du odu odu olodu

277 dance ota ata ota alata

278 play ovivili avivili ovivili alavivili

279 smell onja onjʷun onja onjʷun

285 listen njɛnato aŋjɛnato njɛnato alanjɛnato

286 hear okoᵑ akoᵑ okoᵑ alakoŋ

287 bark ugbɾe ogbɾe ugbɾe olɛgbɾe

288 shout okɛ̚kpa atɛ̚kpa okɛ̚kpa alatɛ̚kpa

289 cry utɾi etɾe utɾi ɛlitɾe

290 fear okibo ekibo ukibu alakibu

291 want oni eni ni ələni

292 think orekɾe arekɾe orekɾe alarekɾe

293 count opuə apuə opuə alapuə

301 spit otakpe atakpe otakpe alatakpe

302 sneeze ɛndiʃa atandiʃa ɛndiʃa alatandiʃa

303 bite onwa anwa onwa alanwa

304 sweep oze aze oze alaze

305 sit otʃɛtʃa atʃɛtʃa otɾɪtɾa alatɾɪtɾa

306 stand njinjə anjinjə njinjə alanjɪnjə

307 fight okwɛn akwɛn okwɛn alakwɛn

308 lie down naw anaŋa naw alaŋa

309 yawn oŋanu aŋanu oŋanu olaŋanu

316 give oma ama oma alamu

323 marry obɾa olobɾa obɾa alakobɾa

324 die uk�po ok�poŋ uk�po oluk�po

325 kill opɾe apɾe opɾe alakpɾe

326 fall ok�pao ok�pao ok�pao ok�pao

327 fall over ok�pa ok�pa ok�pa ok�pa

328 walk ososuŋ ososuŋ ososuŋ olusosuŋ

329 run utito etito utito ɛletito

330 fly ufɾu ofɾu ufɾu olufɾu

331 jump oːfili eːfili utikpɾifu ofɾu

332 swim owo awo owo alawo

333 come ba aːba ba alaba

334 enter onjⁱɾə anjʳɾə onjⁱɾə alanjiɾə

335 exit tʃo ofʃo utɾiti olutɾitri

336 go k�po kaŋ ok�po kaŋ k�po kaŋ olok�pukaŋ

342 scratch okăla akăla okăla alakălu

354 fill okʷoŋ (de) okʷoŋ (de)

355 push otaŋjiᵒ (de) uze (de)

356 pull uwo (de) uwo (de)

357 squeeze okʲun (de) oma (de)

358 dig utu (de) utu (de)

359 plant utʃuwe (de) utʃuwe (de)

361 harvest owa (de) oɾa (de)

31

Language village Ankwa Sabon Gari Ankwa Ankwa

Date 04 March 2011 10 March 2011

Given language name Ankwa Ankwa‐Check

Given village name Sabon Gari Ankwa Ankwa

LGA Kachia Kachia

Language (village) Ankwa (Sabon Gari) Ankwa (Ankwa)

No. English Gloss Sg. Pl. / 3rd sg. Sg. Pl. / 3rd sg.

1 hair ensɛlɛcʷeː onsɛlɛcʷɛ ensɛlɛcʷeː onsɛlɛcʷɛ

2 head ecʷe acʷe ecʷe acʷe

3 forehead ikpoʃo omkpoʃo ikpoʃo omkpoʃo

4 ear oto ato oto ato

10 chin ikpɛndɛre ukpɛndɛɾe ikpɛndɛre ekpɛndɛɾe

11 beard icʷoŋjo ucʷuŋjo icʷoŋjo ucʷuŋjo

12 nose ɛnʃɛwo oŋʃowo ɛʃeo oŋʃowo

13 eye ikɛnɪze ikɛnɪze ikɛnɪze ikɛnɪze

15 tear drop eːzi eːdʒi eːzi eːdʒi

16 neck ogor agor ogor agor

17 shoulder oŋkʲe aŋkʲe oŋkʲe aŋkʲe

19 belly ata.ɛnje atonje ata.ɛnje atonje

20 navel iku uŋku iku uŋku

21 stomach enʲe onʲe aⁱəɾeŋi onʲe

22 intestines igɛɾɛ ungɛɾɛ igɛɾɛ ungɛɾɛ

23 back ɛgo oŋgo ɛgo oŋgo

24 knee utʃuroɾo otʃoroɾo utʃuroɾo otʃoroɾo

25 leg obra abra obra abra

27 shoes otikə atikə otikə atikə

28 thigh ohʷa ahʷa okhʷa akhwa

29 arm ovo avo ovo avo

31 finger emvo omavo emɛmvo amomvo

32 fingernail əkjoᵐ oŋkjoᵐ əkjoᵐ oŋkjoᵐ

33 skin əta ətaː əta ətaː

46 root engɛne engɛne engɛne engɛne

47 branch ɛne one ane ane

48 medicine oga ega oga ega

49 thorn ogan agan ogan agan

50 rope iwe iwe iwe iwe

51 basket ɛmbɛre ombɛre ɛmbɛre ombɛre

52 clothing onga (none) onga (none)

53 seed ewo ewo ewo ewo

54 ax andum andum andum andum

55 cutlass ahoɾa.awaʃe onhoɾa.awaʃe ahoɾa.awaʃe onhoɾa.awaʃe

56 hoe okpolə akpalə okpolə akpalə

57 and

okpolə na

hoɾa.awaʃe (na) same "na" (na)

58 leaf oja aⁱja oja aⁱja

59 ground nut ivi ivi ivi umvi

60 bambura nut ivahʷa ivahʷa ivakʷa umvakʷa

61 guinea corn ogro (none) ogro (none)

74 fruit itʃumaʃɛ itʃimoʃɛ ikuɾaʃe ikuɾaʃe

105 mother aŋjinə aːŋjinə aŋjinə aːŋjinə

106 child awʰe ahʷe awʰe ahʷe

116 animal ɛnumoromu ɛnumoramu ɛnumoromu ɛnumoramu

119 tail ekʲɛn aŋkʲɛn ekʲɛn aŋkʲɛn

122 fly odʒ̠udʒu oːdʒudʒu odʒu oːdʒudʒu

123 spider oːpantɾe aːpantʃe oːpantɾe aːpantʃe

124 mosquito ɛvoʰ ɛvoʰ ɛvoʰ ɛvoʰ

135 crocodile ogʷe egʷe ogʷe egʷe

137 chicken ãno ãno ãno ãno

138 guinea fowl uzo ozo uzo ozo

139 bird ɛno õno ɛno awono

140 claw ɛmpʲo ompʲo ekʲom aŋkjom

141 wing ovo.ɛno avo.ɛ̆no opepʲɛʰ apapɛh

142 feather opɛʰ apapɛʰ apɛh apapɛʰ

150 buffalo ɛkawe ɛkaːwe ɛkawe ɛkaːwe

151 elephant ɛŋka oŋka ɛŋka oŋka

154 hyena ɛᵏhuɾə ɛᵏhuɾə ɛᵏhuɾə ɛᵏhuɾə

155 dog ɛnvə onvə ɛnvə onvə

156 house/hut ɛgbɛ ɛgbɛ ɛgbɛ ɛgbɛ

157 room odo ado odo ado

158 fence opaŋ apaŋ opaŋ apaŋ

159 road/path odʒa adʒa odɾa adɾa

160 pit opolo apulo opolo apulo

161 farm (field) oɾumo (none) oɾumo orum

162 at ɛjɛgbɛ (na) asaɛjɛgbe (na)

163 door oŋʲodo oŋʲado oŋʲodo oŋʲado

164 chair/stool ik�pik�po unk�pok�po ik�pok�po ik�pok�po

165 salt õno (none) õno (none)

166 broom ejilɛh oŋjilɛh ejilɛh oŋjilɛh

167 mortar iːdu undu iːdu undu

168 pestle owodu owodu owodu owodu

170 smoke undʒo (none) undʒo (none)

188 rainy season egolo oŋgolo egolo oŋgolo

189 dry season ewoʰ oŋwoʰ ewoʰ oŋwoʰ

190 dew ume (none) ume (none)

191 stream akɾo akɾo akɾo akɾo

192 river uŋjine ɛŋjine uŋjine ɛŋjine

193 canoe udʒiɾgi ɛmɛtʃi idʒiɾgi ɛmɛtʃi ukpo okpo

194 bridge ogada egada odɛɾ adɛɾ

202 morning odudɾe egʷigʷe odudɾe egʷigʷe

203 afternoon atʃari (none) atʃari (none)

204.1 evening ontoɾe antoɾe ontoɾe antoɾe

205.1 night ugʷe egʷe ugʷe egʷe

206 yesterday kore (none) kore (none)

207 tomorrow ofukʲia (none) ofukʲia (none)

208 knife ɛnkwuɾə onkwuɾə ɛnkwuɾə onkwuɾə

208.1 my bow otaⁱ (na) otaⁱ (na)

208.2 your otaʷ (na) otaʷ (na)

208.4 her otaŋ (na) otaŋ (na)

211 quiver ɪnturu unturu ɪnturu unturu

212 spear ɛkoŋ oŋkoŋ ɛkoŋ oŋkoŋ

222 ripe ɔkɔbɾa itʃimaʃekɔbɾa obɾa (na)

223 rotten ovɔ itʃimaʃɛkovɔ uʃowe (na)

230 black eŋguolup otai ublup ɪtʃitʃi (na)

231 dark uɟʷɛ uɟʷe utʃitʃi uɟʷɛ (na)

232 red ŋgoŋcoŋ otai oncoŋ oŋcoŋ (na)

233 sharp (de) ɛŋhoɾoŋza ondʒa (na)

234 dull (de) (de) ɛndʒanjamwa (na)

235 evil ibzibzi ancʷibzibzi ekɾɪli (na)

236 good ɛgjom anaɟagjom egjegjom (na)

237 many anaɾɛ adɾa saɾe osoŋɾɛ (na)

238 wide ɔɾɔɾai ɔdʒɔ ɔɾɔɾai ɔɾɔɾai (na)

239 narrow upɾupɾi ɔdʒu upɾupɾi owʰale (na)

240 straight ɛdʒi ɔdʒɔdʒɛ utitubo (na)

241 crooked ɛŋgɔgɾɔgɾai ɔdʒɔɾɔgɾai ugegɛmi (na)

243 long ɛdʒi ɔdʒɔdʒɛ odʒodʒe (na)

244 short utiŋ ɔdʒu utitiŋ ukukʷe (na)

246 thick ip͡tsi oʃup͡tsi ipipi (na)

![Table 3. Percentage of Adara [Kadara] language speakers per LGA](https://thumb-ap.123doks.com/thumbv2/123dok/3586865.1452609/11.612.117.492.170.313/table-percentage-adara-kadara-language-speakers-lga.webp)