On: 30 Decem ber 2013, At : 08: 33 Publisher : Rout ledge

I nfor m a Lt d Regist er ed in England and Wales Regist er ed Num ber : 1072954 Regist er ed office: Mor t im er House, 37- 41 Mor t im er St r eet , London W1T 3JH, UK

Psychology, Crime & Law

Publ icat ion det ail s, incl uding inst ruct ions f or aut hors and subscript ion inf ormat ion:

ht t p: / / www. t andf onl ine. com/ l oi/ gpcl 20

Feeling guilty to remain innocent:

the moderating effect of sex on guilt

responses to rule-violating behavior in

adolescent legal socialization

Lindsey M. Col ea, El l en S. Cohna, Cesar J. Rebel l onb & Karen T. Van Gundyb

a

Depart ment of Psychol ogy, Universit y of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA

b

Depart ment of Sociol ogy, Universit y of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA

Publ ished onl ine: 15 Nov 2013.

To cite this article: Lindsey M. Col e, El l en S. Cohn, Cesar J. Rebel l on & Karen T. Van Gundy , Psychol ogy, Crime & Law (2013): Feel ing guil t y t o remain innocent : t he moderat ing ef f ect of sex on guil t responses t o rul e-viol at ing behavior in adol escent l egal social izat ion, Psychol ogy, Crime & Law, DOI: 10. 1080/ 1068316X. 2013. 854794

To link to this article: ht t p: / / dx. doi. org/ 10. 1080/ 1068316X. 2013. 854794

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTI CLE

Taylor & Francis m akes ever y effor t t o ensur e t he accuracy of all t he infor m at ion ( t he “ Cont ent ” ) cont ained in t he publicat ions on our plat for m . How ever, Taylor & Francis, our agent s, and our licensor s m ake no r epr esent at ions or war rant ies w hat soever as t o t he accuracy, com plet eness, or suit abilit y for any pur pose of t he Cont ent . Any opinions and view s expr essed in t his publicat ion ar e t he opinions and view s of t he aut hor s, and ar e not t he view s of or endor sed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of t he Cont ent should not be r elied upon and should be independent ly ver ified w it h pr im ar y sour ces of infor m at ion. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, act ions, claim s, pr oceedings, dem ands, cost s, expenses, dam ages, and ot her liabilit ies w hat soever or how soever caused ar ising dir ect ly or indir ect ly in connect ion w it h, in r elat ion t o or ar ising out of t he use of t he Cont ent .

and- condit ions

Feeling guilty to remain innocent: the moderating effect of sex on guilt

responses to rule-violating behavior in adolescent legal socialization

Lindsey M. Colea*, Ellen S. Cohna, Cesar J. Rebellonband Karen T. Van Gundyb

aDepartment of Psychology, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA;bDepartment of

Sociology, University of New Hampshire, Durham, NH, USA

(Received 8 February 2013; accepted 1 October 2013)

Legal socialization researchers have ignored the role of emotions such as guilt to explain rule-violating behavior (RVB). The purpose of Study 1 was to determine if anticipated guilt or guilt proneness was a better predictor of RVB. Participants were 325 university students who completed an online questionnaire. Correlations indicated that both measures were related significantly to RVB; however, when both were entered into a multiple regression as predictors, only anticipated guilt was significant. This suggested that anticipated guilt was a stronger predictor of RVB than guilt proneness. The purpose of Study 2 was to investigate the effects of anticipated guilt on future RVB while controlling for the integrated legal socialization variables. Participants were 283 middle school and 187 high school students. Multiple regression analyses were conducted to predict students’future engagement in RVB. Anticipated guilt predicted RVB for middle school and high school students. However, sex moderated these effects. Male students low in anticipated guilt committed more RVBs than male students high in guilt. Female high school students showed a similar effect but not at the same magnitude as the male students. Guilt had no significant effect on RVB for female middle school students. Implications for the findings are discussed.

Keywords:adolescents; legal socialization; delinquency; emotion; gender differences

Many of the legal socialization theories explaining delinquent behavior suggest that rational, systematic thinking is the primary component in the decision-making process to engage in these behaviors. Most theories and models that address issues such as rule and law breaking, compliance with authority figures, and moral transgressions have taken a cognitive reasoning approach to understanding the behaviors (Cohn & White, 1990; Levine & Tapp, 1977; Tapp & Kohlberg,1971). As Haidt and Kesebir (2010) explain, however, social and developmental perspectives on morality have become compartmen-talized, failing to address other potential influences on moral transgressions. For example, few researchers have attempted to include an emotional component, especially within legal research (Haidt, 2001; Murphy & Tyler, 2008). Not all human decisions and motivations are rational; many are influenced by one’s emotions. Although one’s emotional state might motivate one to comply with or break rules, the role of emotion has yet to be considered in the legal socialization model.

There has been a considerable amount of research conducted on the relation between emotional response and engagement in transgressions (Baumeister, Stillwell, & Heatherton,

*Corresponding author. Email:lmu3@wildcats.unh.edu http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1068316X.2013.854794

© 2013 Taylor & Francis

1994; Lewis,1971; Tangney & Dearing, 2002); however, there has been little research conducted considering the effects of both emotional response and cognitive reasoning on engagement in these transgressions (Haidt, 2001; Murphy & Tyler, 2008). Without understanding how these two important components affect engagement in RVB, we cannot begin to formulate a complete picture of the legal socialization process. The goal of the current study was to determine if anticipated feelings of guilt provided unique predictive power of rule-violating behavior (RVB) beyond the legal socialization variables proposed by Cohn and colleagues (Cohn, Bucolo, Rebellon, & Van Gundy,2010; Cohn & White,

1986,1990).

Legal socialization

Legal socialization is the process by which an individual develops attitudes and beliefs about the law (Cohn & White, 1990; Levine & Tapp, 1977). Within the field of legal socialization, understanding and predicting engagement in delinquent behaviors has been the predominant topic of research. Past researchers have taken a rational cognitive developmental approach (Cohn & White,1986). In particular, classic models proposed by Levine and Tapp (1977) and Tapp and Kohlberg (1971) conceptualize this approach as a form of legal reasoning that follows a logical process. From this perspective, it is assumed that the decision to engage or not to engage in delinquent behavior is a choice, which is rationally weighed by using one’s ability to engage in complex reasoning regarding legal and moral issues (Cohn et al.,2010).

The original legal socialization theory was derived from theories of moral (Kohlberg,

1969; Piaget, 1932/1965) and legal reasoning (Levine & Tapp, 1977). The legal socialization model proposed by Cohn and White (1986, 1990) expanded upon the original model and proposed the addition of two legal attitudes, normative status and enforcement status, as mediators between cognitive legal reasoning and engagement in RVB. Normative status is the degree to which one approves or disapproves of engaging in RVB. Enforcement status is the degree to which one approves or disapproves of enforcing punishments for breaking rules or laws. Both variables have been shown to be highly predictive of RVBs, particularly in adolescents (Cohn et al.,2010; Cohn & White,1986). Within the integrated legal socialization model, which incorporates both legal and moral reasoning as well as legal attitudes, the level of reasoning attained predicted delinquent behavior (Cohn et al., 2010; Cohn, Trinkner, Rebellon, Van Gundy, & Cole,

2012). Generally, this model is supported by previous research showing that delinquent adolescent offenders tend to have lower levels of moral or legal reasoning compared to their nondelinquent peers (Jurkovic, 1980; Nelson, Smith, & Dodd, 1990). Both the original legal socialization model and the integrated model proposed by Cohn and colleagues have shown a developmental component to the acquisition of cognitive reasoning skills and its relation to RVB (Cohn & White,1986,1990; Cohn et al.,2010; Levine & Tapp, 1977; Tapp & Kohlberg, 1971). For example, Cohn, Bucolo, Rebellon, and Van Gundy (2010) found that the relation between legal reasoning, moral reasoning, legal attitudes, and RVB was different for middle and high school students. This suggests that the relation between legal socialization variables and RVB may change over time as individuals age. Moreover, the relation between moral and legal reasoning and delinquency extends into adulthood and continues to predict offending in later years (Moffitt, 1997; Raaijmakers, Engels, & Van Hoof, 2005). Therefore, it is important to

consider age when examining the relation between legal socialization and RVB, as the model may differ at different stages of development.

Despite the inclusion of both legal and moral reasoning measures, as well as attitudes regarding legal transgressions into the legal socialization model, there has been no attempt to expand the model beyond cognitive and attitudinal factors to include other potential factors, such as emotion. However, by ignoring other factors like emotional responses to RVB, we may be missing an important component in understanding the full scope of the legal socialization process and its relation to engagement in RVB (Haidt,

2001; Haidt & Kesebir,2010). The current study is the first to include guilt, a measure of emotion in addition to cognitive reasoning and attitude measures to the legal socialization model.

Emotion

While there are many different types of emotions experienced by human beings, those connected to engagement in RVB are moral or self-conscious emotions (Baumeister et al.,

1994; Lewis, 1971; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). Individuals who lack the ability to experience an emotional response to normally arousing stimuli, like social transgressions, tend not to develop naturally inhibiting behavior mechanisms (Cleckley, 1982) or appropriate moral emotions (Baumeister, 1998; Hoffman, 1998; Scheff, 1995) and are more likely to break laws (Cleckley, 1982; Frick,2006; Tangney, Stuewig, & Mashek,

2007). Although there is an innate dispositional component in having a moral emotional response to social transgressions, obtaining and utilizing these emotions in a beneficial way is developed from childhood through adolescence and into adulthood (Crystal, Parrott, Okazaki, & Watanabe,2001; De Rubeis & Hollenstein, 2009).

Much of the research conducted on moral emotions has focused on trait measures or a proclivity to feel emotional responses (Ferguson, Stegge, Miller, & Olsen,1999; Hosser, Windzio, & Greve,2008; Lewis,1971; Tangney,1991). However, different situations and types of behaviors may elicit a different emotional response from the same individual. Therefore, it may also be important to consider the relation between emotional responses to specific behaviors in predicting whether that individual will engage in that behavior again in the future. Of the moral emotions previously examined, guilt has been suggested to be one of the most important emotions in relation to moral transgressions (Tracy, Robins, & Tangney, 2007).

Guilt

Guilt has been described as a healthy and adaptive emotion (Baumeister et al., 1994; Tangney,1991). Those who experience guilt tend to want and/or attempt to make some sort of reparation to the victim for their actions (Baumeister et al., 1994; Lewis,1971; Tangney,1991). This proactive approach to a transgression can have a natural inhibitory effect on future behavior, as the desire to repair a wrong doing often involves sympathetic or empathetic feelings toward the victim. Those who are guilt-prone or experience more guilt are less likely to engage in RVB in the future (Ferguson et al.,1999; Hosser et al.,

2008; Lewis,1971).

Guilt has also been described as a private emotion, meaning that it can be experienced even in the absence of others knowing about the transgression (Smith, Webster, Parrott, & Eyre,2002). Thus, there does not have to be a social evaluation of the behavior, but a

self-evaluation and acknowledgment of the inappropriateness of the behavior. Because guilt assessment can be difficult, particularly in young individuals, the experiences of guilt develop with age (Lagattuta & Thompson,2007; Lewis,2007). Older individuals tend to have higher guilt proneness and more experiences of guilt in response to a transgression than children or even adolescents (Orth, Robins, & Soto,2010). Furthermore, women tend to experience more guilt than men (Benetti-McQuoid & Bursik, 2005; Ferguson & Crowley,1997; Walter & Burnaford,2006).

Although there is little research focused on sex differences in this area, some researchers have found that there may be distinct relations between experiences of guilt and engagement in RVB for men and women (Ferguson et al., 1999). For example, Ferguson, Stegge, Miller, and Olsen (1999) found that boys aged 5–12 showed significantly less RVB than girls of the same age when they exhibited high levels of guilt. Both boys and girls low in guilt had greater RVB than high guilt children, but the difference was significantly more profound for boys than it was for girls. However, there has been no existing research, to our knowledge, that has investigated both developmental (comparison of cohorts) and sex differences in guilt experiences when examining behavior. Therefore, further investigation into sex and developmental differences in guilt response to RVB is clearly warranted.

Although an individual may have a proneness to feeling guilty, the actual amount of guilt one experiences may vary from situation to situation. The likelihood of an individual engaging in a specific behavior or type of behaviors may be better predicted by the amount of guilt experienced from those specific behaviors. For example, self-reports of anticipated feelings of moral emotions in response to transgressions have also been shown to be predictive of engagement in RVB (Hay, 2001; Rebellon, Piquero, Piquero, & Tibbetts,

2010; Tibbetts,1997,2003). Furthermore, the integrated legal socialization model utilizes situational or behavioral intention measures of attitudes and reasoning (Cohn et al.,2010). Therefore, it may be more appropriate to use a situational measure of guilt over a trait measure when comparing emotional response to reasoning and attitudes toward these specific behaviors.

Current studies

The current set of studies had two purposes. Study 1 sought to establish the relation between the trait measure of guilt (Tangney, Miller, Flicker, & Barlow,1996), a situational measure of anticipated guilt, and RVB using a cross-sectional survey. Study 2 sought to identify whether anticipated guilt predicted future RVB while controlling for the integrated legal socialization model variables. Study 2 measured guilt responses to RVB in a longi-tudinal study of adolescents. In order to address and explore a potential developmental effect, we compared two age cohorts of participants: one group of middle school students in the same grade and one group of high school students in the same grade. We hypothesized that the anticipated guilt response to RVB would predict engagement in RVB two years later after controlling for the measures of legal reasoning, moral reasoning, normative status, and enforcement status from the integrated legal socialization model. Furthermore, we hypothesized that experiences of guilt would have different relations to RVB for middle and high school students due to developmental differences. We anticipated that guilt would have a stronger relation to RVB for older adolescents. Finally, we conducted an exploratory analysis to assess if the relations between guilt and RVB were moderated by sex.

Study 1 Method

Participants

Participants were 325 (217 female and 108 male) university students (Age: M = 19.23, SD = 2.67). Students were recruited from introductory psychology, research methods, and statistics courses using an online participant pool system. Participants received one credit toward their psychology course requirement for completing the survey.

Materials

Demographics. Participants completed a brief demographic section that included measures of sex (dummy coded: 0 = female, 1 = male), age, and year in college.

Guilt proneness. Guilt proneness was measured using the 15-item subset from the Test of Self-Conscious Affect – Adolescent (TOSCA-A; Tangney et al., 1996). Participants read scenarios and then responded to items by indicating how likely they would be to react in the same way described in the scenario on a scale from 0 (not likely at all) to 4 (very likely). An example of an item is ‘You break something at a friend’s house and then hide it.’Participants then had to indicate how likely they would be to think‘this is making me anxious and I need to fix it.’ All 15 items were averaged to create a composite score for guilt proneness with higher scores indicating higher proneness to feeling guilty (M = 2.88, SD = 0.49, α = 0.83).

Anticipated guilt. Guilt was measured by asking the participants ‘how guilty would you feel about doing the following things even if nobody found out?’ for six behaviors. The six behaviors fell into one of three categories of illicit behaviors, stealing, assault, and substance use, with two items for each type of behavior included in the measure. Responses were given on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (not guilty at all) to 6 (very guilty) with higher scores indicating greater anticipated guilt for each behavior. A score for guilt was computed by averaging all six responses (M =3.09, SD = 1.04, α = 0.78).

RVB. The measure of RVB used for this study was taken from the Delinquency Component of the National Youth Longitudinal Survey (Wolpin, 1983). Students were asked to report how many times in the last six months they had engaged in each of the 26 RVBs. The examples of behaviors are drawn from three general categories of RVB including assault, theft, and substance use. An example of a behavior included in the measure is‘taking something from a store without paying for it.’Due to the highly skewed distribution in scores, responses were recoded into yes/no (0 = no, 1 = yes) for each behavior and summed to create a total variety RVB score (see Trinkner, Cohn, Rebellon, & Van Gundy,2012). Reported scores ranged from 0 to 25 (M = 3.46,SD= 2.78, α= 0.77), with higher scores indicating a greater variety of reported behaviors.

Procedure. Participants registered for the study on the psychology department online experiment scheduling system and were given a link to the online survey. The survey was administered using surveymonkey.com, a secure survey website. Participants were given a completion code at the end of the survey to email to the researchers to receive credit for participating. Therefore, all responses were kept anonymous.

Results and discussion

Bivariate correlations were conducted between the composite measures of guilt proneness, anticipated guilt, sex, and RVB to determine the relation between each of the variables. All variables were significantly correlated in the expected directions. Guilt proneness and anticipated guilt were positively correlated,r= 0.32,p< 0.001, suggesting that they are related constructs but perhaps measure different aspects of guilt. Guilt proneness and RVB were significantly negatively correlated, r = −0.21, p < 0.001, as were anticipated guilt and RVB, r= −0.59,p < 0.001. Moreover, there seemed to be a much stronger relation between anticipated guilt and RVB than guilt proneness and RVB. Next, a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA) was performed to determine if there were sex differences in responses on the guilt proneness and anticipated guilt measures, as well as reported engagement in RVB. The MANOVA was significant, Wilk’s

Λ= 0.95,F(3, 321) = 5.58,p= 0.001. The tests of between subject effects suggested that there were significant differences in guilt proneness, F(1, 323) = 4.45, p = 0.04, anticipated guilt,F(1, 323) = 9.84,p = 0.002, and RVB,F(1, 323) = 14.29,p < 0.001, between male and female participants. Female participants, on average, had higher guilt proneness (male:M= 2.80; female:M= 2.92), anticipated guilt (male:M= 2.85; female: M = 3.22), and reported less engagement in RVB (male: M = 4.23; female: M = 3.06) than male participants. This finding supported the examination of sex as a potential moderating factor between guilt and RVB in further analyses.

To test the competing measures of guilt, a multiple regression analysis was performed with both guilt proneness and anticipated guilt as predictors of RVB. The overall regression was significant,F(2, 149) = 37.46,p< .001,R2= 0.34. Anticipated guilt was a significant predictor of RVB,β=−0.58,t(149) =−8.18,p< 0.001, while guilt proneness was not a significant predictor,β=−0.01,t(149) =−0.05, ns. Therefore, anticipated guilt was considered to be the better predictor of RVB over guilt proneness for the purposes of the current study.

The results suggest that the anticipated guilt measure has a more direct relation to engagement in RVB than the guilt proneness measure. The anticipated guilt measure uses responses to specific behaviors consistent with the types of behaviors reported in the RVB measure. Because both measures utilize the same type of specific behaviors, it makes sense that there would be a stronger relation than with a more general measure, like guilt proneness. In considering the incorporation of a measure of emotion into the integrated legal socialization model, the measure of anticipated guilt is more consistent with preexisting legal socialization attitude measures and would have a stronger predictive value to engagement in RVB than the guilt proneness measure. Therefore, based on the findings from the current study, anticipated guilt seems to be a better measure to be used in conjunction with legal socialization variables.

Study 2 Method

Participants

Individuals in the present study are participants in the New Hampshire Youth Study (NHYS; see Cohn et al.,2010), an ongoing longitudinal study of adolescent RVB in a cohort of middle school and high school students from four urban communities in New Hampshire. Only those participants that had both active parental consent and participant

assent were included in the study. The present paper utilized data from the second (spring 2007), third (fall 2007), and sixth (spring 2009) phases of the NHYS. For the purposes of the current study, the measurement occasions will be referred to as Time 1 (T1), Time 2 (T2), and Time 3 (T3), respectively. At the time of the spring 2007 (T1) collection, participants were in the sixth (age:M= 11.73,SD= 0.53) and ninth (age:M= 14.79,SD = 0.59) grades.

Participants were from two age cohorts, 283 middle school (171 female, 112 male) and 187 high school (129 female, 58 male) students participating in the NHYS. Only participants who had completed questionnaires at T1 (wave 2; spring 2007), T2 (wave 3; fall 2007), and T3 (wave 6; spring 2009) were included in the analyses. There were time lapses of approximately 6 months between collections at T1 and T2, and 18 months between T2 and T3. Due to the rotating schedule of measurement in the NHYS, the time-lapse between T1 and T2 was much shorter than T2 to T3 in order to get all predictor variables measured as closely together as possible.

Drop out rate

Out of the 1040 students who agreed to participate in the NHYS, 939 students completed surveys during the spring of 2007 (T2), 831 students completed additional surveys in the fall of 2007 (T3), and 613 students completed additional surveys in the spring of 2009. After eliminating students with missing/incomplete data, we were able to match a total of 470 (45.2% of entire sample) students to completed surveys at all three data collection sessions. Statistical comparisons of means and standard deviations between students who did not complete all three sessions, and those who did complete all three sessions suggested that there were no significant differences among these groups.

Materials

Due to the rotating measurement schedule of the NHYS, not all measures were included at every collection. Therefore, all controls and predictors used in these analyses were taken from T1, except for measures of emotion, which were measured at T2 six months later. RVB was measured at T3.

Demographics. Participants were asked a series of demographic questions assessing their sex, age, average grade, and the highest level of education completed for each parent. Average grade was indicated on a scale ranging from 1 (Mostly A’s) to 9 (Mostly F’s). Scores were recoded so that higher scores reflected higher grades (M= 7.63,SD= 1.57). Parental level of education was reported on a scale ranging from 1 (less than high school) to 6 (graduate or professional degree) for both mother and father. An average score of parents’education level was used as a proxy for socioeconomic status (SES) (M= 2.41, SD= 1.12).

Anticipated guilt. Anticipated guilt was measured using the same measure described in study 1. See study 1 description for details. A composite score was calculated by averaging all six items with higher scores indicating greater anticipated guilt (M = 4.74, SD= 1.30, α= 0.92).

Legal reasoning. A scale developed by Finckenauer, Tapp, and Yakovlev (1991) was used as a measure of legal reasoning in the NHYS survey. This 11-item measure is a revised scale modified from Tapp and Kohlberg’s (1971) original measure of moral development. The 11 questions were given three possible response answers, each

corresponding to a different level of legal reasoning development ranging in score from 1 (pre-conventional) to 3 (post conventional).‘People should follow law…’is an example of one of the legal reasoning questions and the corresponding answer choices are‘to gain order for society’scored as 3,‘to gain benefits for all’scored as 2, or ‘to avoid being punished’scored as 1. A mean score was taken from all the items to represent the level of legal reasoning for each participant with higher scores indicating higher levels of reasoning. The composite scores ranged from 1.18 to 2.55, with the majority of participants approximately at the conventional or middle level (M =1.93,SD =0.21) on average. Due to the nature of this measure, scale reliability was low (M =1.93, SD = 0.21,α= 0.41), however, this measure has been the standard measure for legal reasoning in previous legal socialization research and was, therefore, included in the current model.

Moral reasoning. A 7-item subscale of Shelton and McAdams’ (1990) Visions of Morality scale was used as a measure of moral reasoning. This subscale of moral reasoning has also been used in previous research on the integrated legal socialization model (Cohn et al.,2010). The scale consisted of brief scenarios that asked participants to rate the likelihood that they would perform a pro-social act in each situation (e.g., donate money found on the street to a charity). The rating system for each scenario was based on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (I definitely would not do) to 7 (I definitely would do), with higher scores reflecting more advanced moral reasoning. The score for moral reasoning was computed as an average of the seven items with scores ranging from 1 to 7 (M = 4.72,SD =1.12,α= 0.82).

Normative status. Normative status is the degree to which one approves of committing RVB. Participants were asked to rate the degree to which they approved of 23 different RVBs (‘How much do you approve of…’). The examples of behaviors are drawn from three general categories of RVB including assault, theft, and substance use. An example of a behavior included in the measure is ‘taking something from a store without paying for it’. Participants rated their approval on a scale from 0 (strongly disapprove) to 3 (strongly approve). A score was calculated by taking an average of all 23 items with higher scores indicating greater approval of RVB. Overall scores for approval ranged from 0 to 3 (M =0.26,SD =0.39,α= 0.95).

Enforcement status. Enforcement status is the degree to which one believes in enforcing punishment for committing RVB. Participants were asked how much they approved of enforcing punishment (‘Should people be punished for …’) for the same 23 behaviors used in the normative status measure. Participants rated the degree to which the behavior should be punished on a scale from 0 (no, definitely not) to 3 (yes, definitely). A mean score was taken to create an overall score of enforcement status with higher scores indicating greater belief in enforcing punishment for RVB. Participant scores ranged from 0 to 3 (M = 2.60,SD = 0.49,α= 0.98).

RVB. The measure of RVB was the same measure used in Study 1. See Study 1 for details. Reported scores ranged from 0 to 23 (M = 1.92, SD = 3.27, α = 0.87), with higher scores indicating a greater variety of reported behaviors.

Procedure

Participants completed the survey in mass testing sessions at their schools and were placed one seat apart from each other to assure confidentiality. After completing the

survey, participants reported to a research assistant and provided their name. The research assistant then located that participant’s arbitrary ID number assigned to them during the first collection from a list and recorded it onto the survey. Participants were compensated for each phase they participated in with a $10 gift certificate to a national bookstore chain.

Results

Preliminary analyses

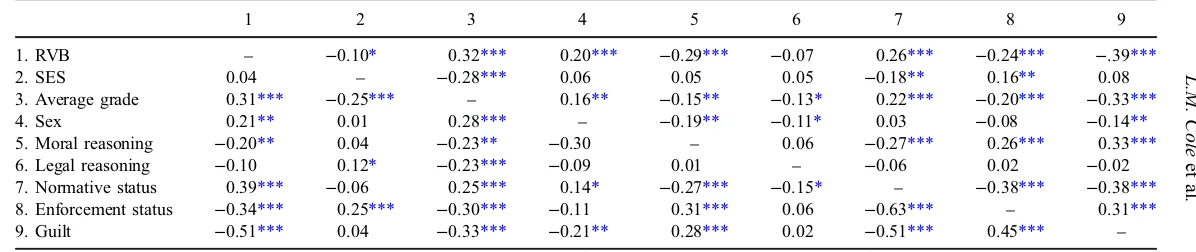

Following the model established by Cohn et al. (2010), middle school and high school students were examined separately in all analyses due to developmental differences in the legal socialization model. Correlational analyses (seeTable 1) were conducted between guilt, legal reasoning, moral reasoning, legal attitudes, RVB, and control variables (sex, SES, and average grade) separately for both middle school and high school students. All significant correlations were in the expected directions (seeTable 1).

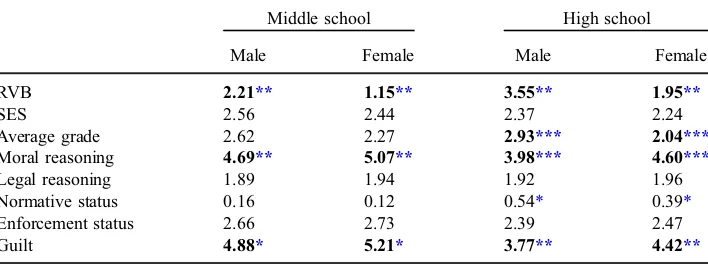

Next an ANOVA was conducted to determine potential differences in guilt response between age cohorts and genders. The test of between subject effects for guilt showed that middle school students had higher levels of guilt (M= 4.95,SD = 0.07) than high school students (M= 4.06,SD= 0.10),F(1, 533) = 52.72,p< 0.001 with a medium effect size,η2= 0.08. The between subject test of guilt for sex showed that male students (M= 4.33,SD = 0.10) had lower levels of guilt than female students (M= 4.68, SD= 0.07), F(1, 533) = 13.80,p= 0.003. The effect size for sex, however, was only small,η2= 0.02. This supported the separation of analyses for each age cohort and the inclusion of sex as a covariate and interaction term (see Table 2 for all mean differences between male and female participants).

Primary analyses

Two hierarchical multiple regression analyses were performed for each cohort, middle school and high school students, to assess the relation between RVB and guilt after controlling for variables taken from the integrated legal socialization model. In the first step of the analyses, all of the integrated legal socialization variables (i.e., legal and moral reasoning measures, normative status, and enforcement status) and control measures including sex, SES, and average grade, were entered. The second step of the analyses tested the main effect for guilt, while controlling for the legal socialization variables. The third step included interaction terms to explore potential moderation between sex (dummy coded; 0 = female, 1 = male) and each emotional response in predicting RVB. The final model included only significant interactions after nonsignificant interactions were removed.

Middle school students. In the middle school analysis predicting future RVB (seeTable 3), the overall regression for the first step (Step 1) for the analysis testing only the integrated legal socialization variables and controls was significantF(7, 275) = 9.05,p< 0.001,R2= 0.19. Guilt was added in Step 2 to test for main effects. This regression was significant,F(8, 274) = 9.74,p< 0.001,R2= 0.22 and was a significant increase over the legal socialization variable model, R2Δ = 0.03,F(1, 274) = 12.03,p = 0.001. Sex,β = 0.12, t(274) = 2.25,p = 0.03, normative status,β = 0.14,t(274) = 2.16,p = 0.03, and guilt,β=−0.22,t(274) =−3.47,p= 0.001, were all significant predictors of RVB at T3. In the final step (Step 3), the interaction term between sex and guilt was entered into the

Table 1. Bivariate correlations: middle and high school students.

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

1. RVB –

−0.10* 0.32*** 0.20*** −0.29*** −0.07 0.26*** −0.24*** −.39***

2. SES 0.04 – −0.28*** 0.06 0.05 0.05 −0.18** 0.16** 0.08

3. Average grade 0.31*** −0.25*** – 0.16** −0.15** −0.13* 0.22*** −0.20*** −0.33***

4. Sex 0.21** 0.01 0.28*** – −0.19** −0.11* 0.03 −0.08 −0.14**

5. Moral reasoning −0.20** 0.04 −0.23** −0.30 – 0.06 −0.27*** 0.26*** 0.33***

6. Legal reasoning −0.10 0.12* −0.23*** −0.09 0.01 – −0.06 0.02 −0.02

7. Normative status 0.39*** −0.06 0.25*** 0.14* −0.27*** −0.15* – −0.38*** −0.38*** 8. Enforcement status −0.34*** 0.25*** −0.30*** −0.11 0.31*** 0.06 −0.63*** – 0.31*** 9. Guilt −0.51*** 0.04 −0.33*** −0.21** 0.28*** 0.02 −0.51*** 0.45*** –

RVB, rule-violating behavior (T1); SES, socioeconomic status; middle school students above diagonal; high school students below diagonal; sex dummy codedfemale= 0,male= 1. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001.

L.

M.

Cole

et

al

.

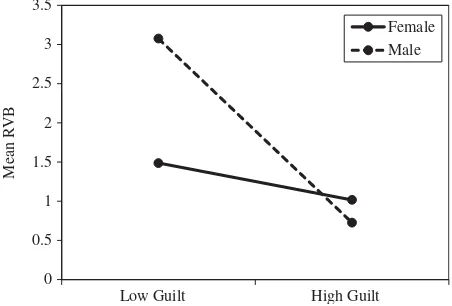

regression. This regression was also significant overall,F(9, 273) = 9.90,p< 0.001,R2= 0.25, and explained significantly more variance than the regression from step 2, R2Δ = 0.03,F(1, 273) = 8.97,p= 0.001. There was a significant main effect for sex,β= 0.11, t(273) = 2.04,p= 0.04, and guilt,β= −0.21,t(273) =−3.46,p= 0.001. The interaction between sex and guilt was also significant,β=−0.16,t(273) =−2.99,p= 0.003, with an effect size of f2= 0.33. Results suggested that the relation between guilt and RVB was different for male and female students.

In order to test the significance of this interaction, conditional effects of guilt at high (+ 1 SD) and low (−1SD) levels for male and female students were assessed using simple slope testing (seeFigure 1). However, one standard deviation above the mean for guilt resulted in an impossible score. Therefore, high levels of guilt were set at the maximum possible value of six. Results showed that anticipated guilt did not have a significant effect on RVB for female students,β=−0.08,t(273) =−1.08,p= ns. Anticipated guilt did have a significant effect for male students,β=−0.41,t(273) =−4.59,p< 0.001. At high levels of guilt, there was no significant difference in RVB between male and female students,β=−0.08,t(273) =

−0.58,p= ns. At low levels of guilt, however, there was a significant difference between male and female students’in predicting RVB,β = 0.49,t(273) =−3.63,p < 0.001. This suggested that male students with low anticipated guilt were more likely to engage in greater RVB than female students low in guilt.

High school students. In the high school student analysis (see Table 4), the overall regression for the first step testing only the integrated legal socialization variables and controls was significant,F(7, 179) = 8.74,p< 0.001,R2= 0.26. Guilt was entered on the second step of the regression to test for a main effect. The overall regression including guilt was significant, F(8, 178) = 11.06, p < 0.001, R2 = 0.33, and was a significant increase over the legal socialization model from step 1,R2Δ = 0.08, F(1, 178) = 20.58, p < 0.001. In the current model, the significant predictors of RVB at T3 were guilt,β= −0.36, t(178) =−4.57,p < 0.001, SES, β = 0.17,t(178) = 2.54, p = 0.01, and average grade, β = −0.17, t(178) = −2.38, p = 0.02. The results suggested that there was an inverse relation between anticipated feelings of guilt and engagement in RVB at T3.

In the final step, a product term between sex and guilt was entered into the regression. The overall regression was significant,F(9, 177) = 11.95, p <0.001, R2= 0.38, and was a Table 2. Mean differences between predictors male and female middle school and high school students.

Middle school High school

Male Female Male Female

RVB 2.21** 1.15** 3.55** 1.95**

SES 2.56 2.44 2.37 2.24

Average grade 2.62 2.27 2.93*** 2.04***

Moral reasoning 4.69** 5.07** 3.98*** 4.60***

Legal reasoning 1.89 1.94 1.92 1.96

Normative status 0.16 0.12 0.54* 0.39*

Enforcement status 2.66 2.73 2.39 2.47

Guilt 4.88* 5.21* 3.77** 4.42**

Note: Bolded values indicate significant values. Mean differences significant at *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001.

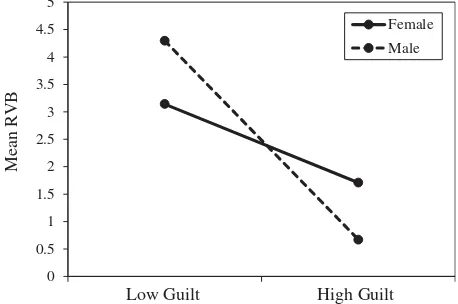

significant increase over the main effect model, R2Δ = 0.05, F(1, 177) = 13.05, p < 0.001. There was a significant main effect for guilt,β=−0.19,t(177) =−2.16,p= 0.03, SESβ= 0.16,t(177) = 2.44,p= 0.02, and average grade,β=−0.18,t(177) =−2.62,p= 0.01. There was also a significant interaction between sex and guilt,β=−0.29,t(177) = −3.61,p< 0.001, with an effect size off2= 0.61, indicating a significant difference in the effect of guilt on male and female students’RVB.

To test the significance of these differences, conditional effects testing using simple slope tests was employed at high (+ 1SD) and low (−1SD) levels of guilt (seeFigure 2). Results showed a significant effect of anticipated guilt on RVB for male students, β = −0.66,t(177) =−5.82,p< 0.001, and for female students,β=−0.19,t(177) =−2.16,p= 0.03, although the effect was much stronger for male students. For both male and female students, those higher in anticipated guilt engaged in less RVB at T3 than those low in guilt. At low levels of guilt, there was a significant difference between male and female students’RVB, β = 0.23, t(177) = 2.71, p = 007, indicating that male students low in Table 3. Standardized and unstandardized regression coefficients predicting total rule-violating behavior at T3 middle school students.

Variables Legal socialization Guilt main effect Guilt × Sex interaction

SES −0.08 (−0.21) −0.10 (−0.23) −0.09 (−0.21) Average grade −0.09 (−0.17) −0.04 (−0.08) −0.04 (−0.07)

Sex 0.14 (0.81)* 0.12 (0.72)* 0.11 (0.65)*

Moral reasoning −0.10 (−0.27) −0.08 (−0.20) −0.10 (−0.26) Legal reasoning 0.00 (0.00) −0.02 (−0.24) −0.04 (−0.49) Normative status 0.19 (2.00)** 0.14 (1.43)* 0.12 (1.22) Enforcement status −0.14 (−0.91)* −0.11 (−0.67) −0.10 (−0.61)

Guilt −0.22 (−0.51)** −0.21 (−0.58)***

Sex × Guilt −0.16 (−0.77)**

F-test F(7, 275) = 9.05***, R2= 0.19

F(8, 274) = 9.74***, R2= 0.22,R2Δ= 0.03**

F(9, 273) = 9.90***, R2= 0.25,R2Δ= 0.03**

Note: Coefficients outside parentheses are standardized. Coefficients inside parentheses are unstandardized. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001.

0 0.5 1 1.5 2 2.5 3 3.5

Low Guilt High Guilt

Mea

n

R

V

B

Female Male

Figure 1. Guilt by sex interaction predicting RVB at T3 middle school students.

anticipated guilt engaged in more RVB at T3 than female students low in guilt. There was also a significant difference between male and female students’ RVB at high levels of guilt, β = −0.21, t(177) = −2.25, p = 0.03, suggesting that female students high in anticipated guilt committed more RVB at T3 than male students high in guilt.

Discussion

Legal socialization researchers have primarily focused on cognitive reasoning measures and have largely ignored the role of emotions in predicting RVB. However, previous emotions researchers have shown that emotions like guilt relate to engagement in RVB (Dearing, Stuewig, & Tangney, 2005; Ferguson et al., 1999; Hosser et al., 2008). The purpose of the present study was to argue for the inclusion of a guilt variable in legal socialization models. We were interested in evaluating the predictive power of anticipated guilt on future RVB while controlling for the integrated legal socialization model

0

Figure 2. Guilt by sex interaction predicting RVB at T3 high school students.

Table 4. Standardized and unstandardized regression coefficients predicting total rule-violating behavior at T3 high school students.

Variables Legal socialization Guilt main effect Guilt × Sex interaction

SES −0.18 (0.65)* −0.17 (0.61)* 0.16 (0.57)* Average grade −0.20 ( 0.47)** −0.17 (−0.40)* −0.18 (−0.43)*

Sex 0.07 (0.54) 0.04 (0.28) 0.01 (0.06)

Moral reasoning −0.06 (−0.22) −0.03 (−0.09) −0.03 (−0.12) Legal reasoning −0.01 (−0.21) −0.04 (−0.66) 0.01 (0.14) Normative status 0.28 (2.27)** 0.14 (1.12) 0.09 (0.72) Enforcement status −0.10 (−0.73) −0.04 (−0.25) −0.05 (−0.34)

Note: Coefficients outside parentheses are standardized. Coefficients inside parentheses are unstandardized. *p< 0.05, **p< 0.01, ***p< 0.001.

variables. The results indicated that the inclusion of anticipated guilt as a predictor of RVB explained significantly more variance than the legal socialization variables alone. This supports that anticipated guilt provides a unique contribution beyond the legal socialization model. Moreover, many of the legal socialization predictor variables became nonsignificant after including the interaction between sex and guilt into the analysis. Therefore, this suggests that guilt may even have some sort of mediating role in the legal socialization model.

Emotional responses to committing RVB may be an important part of legal socialization process that has long been ignored or undervalued. Although there has been a considerable amount of research conducted examining the effect of moral emotions on RVB alone (Baumeister et al., 1994; Lewis, 1971; Tangney & Dearing,

2002), there have been few researchers who have examined cognitive reasoning processes and moral emotional responses to transgressions together. Moreover, the relation between reasoning ability, emotional response, and RVB may be different when both factors are considered together. In failing to recognize this important factor in cognitive reasoning models of RVB engagement, the results from the current study suggest that researchers are missing a whole other piece to the legal socialization process that goes beyond what cognitive reasoning and attitude measures can tell us alone.

How such emotions like guilt fit into the process of legal socialization remains to be seen. Results showed that the inclusion of anticipated guilt made a unique contribution to the model, perhaps even as a potential mediator. Researchers in this area should consider the inclusion of measures of emotional response to RVB in building new models of legal socialization and focus on how these factors would fit into the existing cognitive models. However, the results from the current study suggest that the relation between emotional responses to RVB and future RVB engagement may not be the same for everyone. This will also have to be an important consideration in creating new models of legal socialization that includes an emotion component.

In the current study, anticipated guilt was an important predictor of RVB for both middle and high school students. However, many of the effects of guilt on RVB were qualified by a sex interaction. The middle school student analysis indicated a significant effect for anticipated guilt on later RVB, but only for male students. Male students who reported low levels of anticipated guilt had greater RVB than male students who reported high levels. For female middle school students, this relation was in the same direction, but was not significant. In addition, there was no significant difference in RVB between male and female students high in anticipated guilt. However, there was a significant difference between male and female students low in anticipated guilt with male students engaging in significantly greater RVB than female students.

Anticipated guilt was also an important predictor for the high school cohort. Students who reported low levels of anticipated guilt engaged in significantly greater RVB at T3 than students who reported high levels of guilt; however, this effect was stronger for male students. Interestingly, male students who were high in anticipated guilt specifically committed the least amount of RVB at T3 than did all other high school students. Furthermore, male students who were low in anticipated guilt committed the greatest amount of RVB at T3 than did all other high school students both high and low in guilt. These findings support previous research suggesting that individuals with high levels of guilt (Ferguson et al.,1999; Hosser et al.,2008; Lewis,1971) are less likely to engage in RVB in the future. However, the differences found between male and female students within the same cohort are somewhat inconsistent with previous research in this area.

Previous researchers have often found that women tend to have greater experiences of guilt than men (Lewis, 1987; Smith et al.,2002; Tangney & Dearing, 2002). However, this does not explain why the relation between anticipated guilt and engagement in RVB was stronger for male students than for female students. Due to the exploratory nature of the sex interaction analysis, it would be difficult to render an accurate explanation for this phenomenon. One explanation, however, is that the difference may stem from measurement. For example, many of the previous studies on emotion and RVB have used a different form of measurement for assessing guilt response (Lewis, 1987; Tangney,

1991; Tangney & Dearing, 2002; Tangney & Fischer,1995). These measures focus on internal feelings associated with experiencing guilt and do not specifically ask the individual how much guilt they would experience, as did the measure used in the current study.

The difference in measurement could have contributed to the contradictory findings between previous research and the current study. It might be that the measure of anticipated guilt is able to detect differences that other measures, like guilt proneness, may not be sensitive to. In addition, many of these studies have been conducted using university and adult samples. Perhaps this difference in the relation between anticipated guilt and RVB for men and women is only evident in adolescence and becomes less pronounced, as individuals get older. If this were the case, it could explain why there was little effect of guilt on RVB for female middle school students and a significant effect for female high school students. It could also explain why many researchers have not found similar results, as guilt may actually have the same effect on RVB for male and female participants in adulthood.

In a study conducted by Ferguson and colleagues (1999), a similar pattern of results was found between guilt and RVB for young school aged girls. The researchers, in this case, suggested that it might be a function of how girls are socialized. Girls may be held to higher standards of sympathetic response than boys but are in turn expected to adhere to the rules more. Therefore, when girls do violate rules, they may perceive that they will be punished more severely if they do not show remorse for their actions than would boys. Because girls are socialized to display an emotional and remorseful response to rule-violation, there may not be very much difference in anticipated guilt response between female students, regardless of how much RVB they actually commit.

The difference between male and female students may also be a result of the amount and type of behaviors being committed. In both the middle and high school student analyses, for example, female students in general committed significantly less RVB than male students (seeTable 2). If female students are committing few RVBs overall, there may not be enough variability in RVB between students low and high in anticipated guilt to show an effect. The difference could also be a result of developmental trajectories. Previous researchers have found that female adolescents tend to have greater experiences of guilt than males (Benetti-McQuoid & Bursik, 2005; Ferguson & Crowley, 1997; Walter & Burnaford,2006), even at young ages, which suggests that female adolescents may mature emotionally earlier than their male counterparts. If this were the case in the current study, however, then the male students would have showed an effect of guilt on RVB in high school but perhaps not in middle school while female students would have showed an effect in both middle and high school. Therefore, the findings would not suggest developmental maturity differences as a potential explanation.

Finally, the differences found between male and female students in anticipated guilt response in the current study could simply be because we were controlling for cognitive

reasoning factors. Female students’ guilt response to committing RVB may be closely tied to their cognitive reasoning. If the relation between emotional response and cognitive reasoning is interrelated for female students but are independent mechanisms for male students, then it could explain the difference found in the effect. Women have been found to be more receptive to others’emotions and tend to have greater feelings of empathy in response to committing social transgressions than men (Benetti-McQuoid & Bursik,

2005; Tangney, 1991). As many forms of RVB include harming another, women may generally have a greater emotional response to committing RVB against another because of their increased feelings of empathy and in turn have integrated those emotions into their cognitive reasoning skills for considering committing RVB in the future. Because we controlled for cognitive reasoning measures including legal reasoning and moral reasoning, the measures of anticipated guilt themselves may not have showed a very large effect due to shared variance with the cognitive reasoning measures.

Limitations and future directions

There were some limitations that should be addressed in future research. First, due to the rotating schedule of variable inclusion in the NHYS survey, all predictive measures were not collected at the same time. For example, the legal socialization variables were collected at T1 while the emotion variables were collected at T2, six months later. In order to combat this issue, future waves of data collection will attempt to include all necessary measures together. Additionally, through the continued inclusion of these variables, we will also be able to track changes in the relation between guilt and RVB into adulthood with our oldest sample.

A second limitation relates to the nature of the measures. We decided to use self-report measures of RVB and anticipated feelings of guilt instead of a guilt proneness measure typically used in examining RVB (Tangney & Fischer, 1995; Tangney et al.,

1996; Tracy et al., 2007). Both of these measures may, therefore, result in self-presentation inflation. In other words, many participants may over or under report the number and frequency of behaviors engaged in. This was partially alleviated by using a variety measure over a frequency measure of behavior, but unfortunately cannot be completely eliminated due to the survey style of the study. As for the guilt measure, our initial study suggested that the anticipated guilt measure was a better predictor of RVB for the purposes of the current study and the integrated legal socialization model. However, the anticipated guilt is a self-report measure and may have been affected by social norms of how people think they should feel in response to committing RVB based on social standards and not necessary how they actuallywould feel.

In addition, the measure of guilt used in the current study assumed that participants were able to distinguish between feelings of guilt from other moral emotions, particularly shame. Shame is often thought of as requiring public exposure and negative evaluation of the behavior by others (Rebellon et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2002) while guilt has been described as a private emotion (Smith et al., 2002). The anticipated guilt measure was specifically worded to maximize this distinction by stating‘how guilty would you feel…

even if nobody found out?’ The purpose of the current study, however, was not to compare the effect of guilt and shame but to introduce a measure of emotional response into legal socialization. Although a similar measure of shame was not included in the current study, future research could include a measure of shame to compare and contrast

to the measure of guilt used. Future researchers could also include other measures of emotional response into the model as well.

A third limitation is the behavioral measure used. In the current study, a composite measure of RVB was used, consistent with previous research on the integrated legal socialization model (Cohn et al., 2010, 2012). The majority of behaviors that female students did engage in, however, were substance use behaviors. It may be that the relation between anticipated guilt and substance use is different from other types of behaviors like assault or theft. For instance, substance use could be considered a victimless crime where a desire for reparation, which is characteristic of feeling guilt (Baumeister et al., 1994; Lewis, 1971; Tangney, 1991), is not present because there is no perceived victim. Moreover, substance use may be viewed by adolescents as common or a less severe offense than assault or theft, thereby limiting the amount of guilt one would feel for engaging in the behavior. In the future, we would like to examine the relation between guilt and specific types of RVBs.

Other factors may also relate to engagement in RVB that were not included in the current study. One of the most important may be personality factors. Previous researchers have found that personality traits like impulsivity, sensation seeking, and novelty seeking are predictive of engagement in RVB (Farrington & Jolliffe, 2001; Jones, Miller, & Lynam,2011). Although personality factors were not the focus of the current study, future research should assess the predictive ability of these factors within the legal socialization model as well.

Conclusion

Overall, the analyses supported our hypotheses. Guilt predicted future RVB over and above the behavioral and cognitive based measures in the integrated legal socialization model. Furthermore, there was a developmental difference in the relation between guilt and RVB for middle and high school participants. Legal socialization researchers have previously ignored the importance of emotion in RVB engagement. The results from this study suggest that future researchers should consider including an emotion component in building new models of legal socialization. Moreover, the findings highlight a distinction in how guilt is related to future RVB in male and female students. Without a definitive explanation for this difference, however, further research is needed to disentangle the nature of this effect and replicate these findings. Because there is very little research concerning sex differences in the relation between emotion and engagement in delinquency, findings from this study show strong support for future research in this area. Hopefully, future studies will begin to address the importance of understanding the emotional component to engagement in delinquent behaviors in addition to the cognitive component that is so widely accepted.

References

Baumeister, R. F. (1998). Inducing guilt. In J. Bybee (Ed.), Guilt and children (pp. 127–138). Boston, MA: Academic Press.

Baumeister, R. F., Stillwell, A. M., & Heatherton, T. F. (1994). Guilt: An interpersonal approach. Psychological Bulletin,115, 243–267. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.115.2.243

Benetti-McQuoid, J., & Bursik, K. (2005). Individual differences in experiences of and responses to guilt and shame: Examining the lenses of gender and gender role.Sex Roles,53(1–2), 133–142. doi:10.1007/s11199-005-4287-4

Cleckley, H. (1982).The mask of sanity. St. Louis: C.V. Mosby.

Cohn, E. S., Bucolo, D. O, Rebellon, C. J., & Van Gundy, K. (2010). An integrated model of legal and moral reasoning and rule-violating behavior: The role of legal attitudes. Law and Human Behavior,34, 295–309. doi:10.1007/s10979-009-9185-9

Cohn, E. S., Trinkner, R. J., Rebellon, C. J., Van Gundy, K. T., & Cole, L. M. (2012). Legal attitudes and legitimacy: Extending the integrated legal socialization model.Victims & Offenders, 7, 385–406. doi:10.1080/15564886.2012.713902

Cohn, E. S., & White, S. O. (1986). Cognitive development versus social learning approaches to studying legal socialization.Basic and Applied Social Psychology,7, 195–209. doi:10.1207/ s15324834basp0703_3

Cohn, E. S., & White, S. O. (1990).Legal socialization: A study of norms and rules. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Crystal, D. S., Parrott, W. G., Okazaki, Y., & Watanabe, H. (2001). Examining relations between shame and personality among university students in the United States and Japan: A developmental perspective.International Journal of Behavioral Development,25(2), 113–123. doi:10.1080/01650250042000177

Dearing, R. L., Stuewig, J., & Tangney, J. P. (2005). On the importance of distinguishing shame from guilt: Relations to problematic alcohol and drug use. Addictive Behaviors, 30, 1392–1404. doi:10.1016/j.addbeh.2005.02.002

De Rubeis, S., & Hollenstein, T. (2009). Individual differences in shame and depressive symptoms during early adolescence. Personality and Individual Differences, 46, 477–482. doi:10.1016/j. paid.2008.11.019

Farrington, D. P., & Jolliffe, D. (2001). Personality and crime. In N. J. Smelser & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social and behavioural sciences(pp. 11260–11264). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Ferguson, T. J., & Crowley, S. L. (1997). Gender differences in the organization of guilt and shame.Sex Roles,37(1–2), 19–44. doi:10.1023/A:1025684502616

Ferguson, T. J., Stegge, H., Miller, E. R., & Olsen, M. E. (1999). Guilt, shame and symptoms in children.Developmental Psychology,35, 347–357. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.35.2.347

Finckenauer, J. O., Tapp, J., & Yakovlev, A. M. (1991).American and Soviet youth: A comparative study of legal socialization. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Frick, P. J. (2006). Developmental pathways to conduct disorder.Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America,15, 311–331. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2005.11.003

Haidt, J. (2001). The emotional dog and its rational tail: A social intuitionist approach to moral judgment.Psychological Review,108, 814–834. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.108.4.814 Haidt, J., & Kesebir, S. (2010). Morality. In S. Fiske, D. Gilbert, & G. Lindzey (Eds.),Handbook of

social psychology(5th ed., pp. 797–832). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Hay, C. (2001). An exploratory test of Braithwaite’s reintegrative shaming theory. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency,38(2), 132–153. doi:10.1177/0022427801038002002 Hoffman, M. L. (1998). Varieties of empathy-based guilt. In J. Bybee (Ed.),Guilt and children

(pp. 91–112). Boston, MA: Academic Press.

Hosser, D., Windzio, M., & Greve, W. (2008). Guilt and shame as predictors of recidivism: A longitudinal study with young prisoners. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(1), 138–152. doi:10.1177/0093854807309224

Jones, S. E., Miller, J. D., & Lynam, D. R. (2011). Personality, antisocial behavior, and aggression: A meta-analytic review.Journal of Criminal Justice,39, 329–337. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2011. 03.004

Jurkovic, G. J. (1980). The juvenile delinquent as a moral philosopher: A structural developmental perspective.Psychological Bulletin,88, 709–727. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.88.3.709

Kohlberg, L. (1969). Stage and sequence: The cognitive-developmental approach to socialization. In D. A. Goslin (Ed.),Handbook of socialization theory(pp. 347–480). Chicago: Rand McNally. Lagattuta, K. H., & Thompson, R. A. (2007). The development of self-conscious emotions. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.),The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 91–113). New York: Guilford Press.

Levine, F. J., & Tapp, J. L. (1977). The dialectic of legal socialization in community and school. In J. L. Tapp & F. J. Levine (Eds.), Law, justice and the individual in society: Psychological and legal issues(pp. 163–182). New York, NY: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston.

Lewis, H. B. (1971).Shame and guilt in neurosis. New York, NY: International Universities Press.

Lewis, M. (2007). Self-conscious emotional development. In J. L. Tracy, R. W. Robins, & J. P. Tangney (Eds.),The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research (pp. 134–149). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Moffitt, T. E. (1997). Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent offending: A complementary pair of developmental theories. In T. P. Thornberry (Ed.),Developmental theories of crime and delinquency(pp. 11–54). Piscataway, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

Murphy, K., & Tyler, T. (2008). Procedural justice and compliance behaviour: The mediating role of emotions.European Journal of Social Psychology,38, 652–668. doi:10.1002/ejsp.502 Nelson, J. R., Smith, D. J., & Dodd, J. (1990). The moral reasoning of juvenile delinquents: A

meta-analysis.Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology,18, 231–239. doi:10.1007/BF00916562 Orth, U., Robins, R. W., & Soto, C. J. (2010). Tracking the trajectory of shame, guilt, and pride

across the life span.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,99, 1061–1071. doi:10.1037/ a0021342

Piaget, J. (1932/1965).The moral judgement of the child. New York, NY: Harcourt, Brace & World. Raaijmakers, Q. A. W., Engels, R. C. M. E., & Van Hoof, A. (2005). Delinquency and moral reasoning in adolescence and young adulthood. International Journal of Behavioral Develop-ment,29, 247–258. doi:10.1080/01650250544000035

Rebellon, C. J., Piquero, N. L., Piquero, A. R., & Tibbetts, S. G. (2010). Anticipated shaming and criminal offending. Journal of Criminal Justice, 38, 988–997. doi:10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2010. 06.016

Scheff, T. J. (1995). Conflict in family systems: The role of shame. In J. P. Tangney & K. W. Fischer (Eds.), Self-conscious emotions: The psychology of shame, guilt, embarrassment, and pride(pp. 393–412). New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Shelton, C. M., & McAdams, D. P. (1990). In search of everyday morality: The development of a measure.Adolescence,25, 923–943.

Smith, R. H., Webster, J. M., Parrott, W. G., & Eyre, H. L. (2002). The role of public exposure in moral and nonmoral shame and guilt.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,83(1), 138– 159. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.83.1.138

Tangney, J. P. (1991). Moral affect: The good, the bad, and the ugly.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,61, 598–607. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.61.4.598

Tangney, J. P., & Dearing, R. L. (2002).Shame and guilt. New York, NY: Guilford Press. Tangney, J. P., & Fischer, K. W. (Eds.). (1995).Self-conscious emotions: The psychology of shame,

guilt, embarrassment, and pride. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Tangney, J. P., Miller, R. S., Flicker, L., & Barlow, D. H. (1996). Are shame, guilt, and embarrassment distinct emotions?Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,70, 1256–1269. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.70.6.1256

Tangney, J. P., Stuewig, J., & Mashek, D. J. (2007). Moral emotions and moral behavior.Annual Review of Psychology,58, 345–372. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.56.091103.070145

Tapp, J. L., & Kohlberg, L. (1971). Developing senses of law and legal justice.Journal of Social Issues,27(2), 65–91. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1971.tb00654.x

Tibbetts, S. G. (1997). Shame and rational choice in offending decisions. Criminal Justice and Behavior,24, 234–255. doi:10.1177/0093854897024002006

Tibbetts, S. G. (2003). Self-conscious emotions and criminal offending.Psychological Reports,93 (1), 101–126. doi:10.2466/pr0.2003.93.1.101

Tracy, J. L., Robins, R. W., & Tangney, J. P. (Eds.). (2007).The self-conscious emotions: Theory and research. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

Trinkner, R., Cohn, E. S., Rebellon, C. J., & Van Gundy, K. (2012). Never trust anyone over 30: Parental legitimacy as a mediator between parental style and changes in rule-violating behavior over time.Journal of Adolescence,35, 119–132. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2011.05.003 Walter, J. L., & Burnaford, S. M. (2006). Developmental changes in adolescents’guilt and shame:

The role of family climate and gender.North American Journal of Psychology,8, 321–338. Wolpin, K. (1983).The national longitudinal handbook 1983–1984. Columbus, OH: Center for

Human Resource Research, Ohio State University.