AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS

Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra

in English Letters

By

LANOKE INTAN PARADITA Student Number: 044214098

ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMNET OF ENGLISH LETTERS

FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

AN UNDERGRADUATE THESIS

Presented as Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Sarjana Sastra

in English Letters

By

LANOKE INTAN PARADITA Student Number: 044214098

ENGLISH LETTERS STUDY PROGRAMME DEPARTMNET OF ENGLISH LETTERS

FACULTY OF LETTERS SANATA DHARMA UNIVERSITY

YOGYAKARTA 2009

No Rain. No Rainbow

For my siblings,

Lana and Mona

And my best friends,

Ningsih and Senny

This thesis will never find its way without all His grace. I thank Allah SWT, my God Almighty. I realize this thesis will never reach its end, without great supports from countless gorgeous people. I thank Adventina Putranti, S.S., M. Hum very much, my wonderful advisor, for her valuable guides through out the writing process and my co-advisor, Harris Hermansyah S., S.S., M.Hum for his support. I also thank all lectures and staffs of Sanata Dharma University, especially those cheering up the Department of English Letters, for all the knowledge and experience shared.

My great gratitude for my parents for their never-ending challenges, my brother, Lana, hopefully he will run as fast as the wind soon. For my sister Mona, my Grandmother, my aunt Bude Rini, Tante Endang, and my uncle Pakde Sam for their support. I also send many thanks for my beautiful best friends Ningsih, Senny, and Ståle for their lifetime experiences. For Eling, Mas Topik, Aryk, Toni, Tuti, Wira, Ade, for the best friendship and the great change of my life. For all of my creative brilliant friends in Komunitas Gayam 16, Mbak Dita for her valuable sharing, Rosyi, Penceng, Icak, Dika, Yusda, Mas Hana, Mas Asep, Mas Djijit, Mas Djoko, Mas Rudit, Mbah Sapto, Simak Aciek, Mbak Beta, Mbak Sani, and Mbak Putri who give a never ending chance for me to grow.

I also thank Bank BCA very much for the fund helping me passing those many semesters. I also send my gratitude to Pak Edy who gives me the inspiration, Skaeys for all of the surprises, my Aikido-ka friends, String Movie Maniacs, EDS Sadhar, and Panggung Boneka for the precious experiences. My countless thanks Masashi Kishimoto-sensei, Akeboshi, and Bang Andrea Hirata for their wonderful and beautiful spirit, and for Robin S. Sharma for his wisdom.

I also thank Saoran for his unbelievable experiences and Sigit for those wakes up; they certainly did!

And my honor for everyone who never stops fighting for their dreams!

Lanoke Intan Paradita

APPROVAL PAGE………

A. Background of the study………...

B. Problem Formulation………

C. Objectives of the Study………. D. Definition of Terms………... CHAPTER II: THEORETICAL REVIEW……… A. Review of Related Studies………. B. Review of Related Theories………...

1. Theory of local organization operating within a conversation………. 2. Theory of Cooperative Principles by Grice……….. C. Theoretical Framework……….. CHAPTER III: METHODOLOGY...

A. Object of the Study……….

B. Approach of the Study………

C. Method of the Study………...

D. Research Procedure………

1. Data collection………

2. Data Analysis………...

CHAPTER IV: ANALYSIS……….. A. The analysis of maxims violated………... 1. The violation of maxim of quantity………... 2. The violation of maxim of quality……….. 3. The violation of maxim of manner……….

4. Opting out………...

5. The violation of maxim of quantity and maxim of manner………... 6. The violation of maxim of Quality and maxim of

1. To control the other participants’ feeling by creating fear……. 2. To plead the other participants………... 3. To repair what has been said by the participant………. 4. To cover or keep the truth a secret………. 5. To persuade someone doing something……….

50 50 51 52 54 56

CHAPTER V: CONCLUSION………. 58

BIBLIOGRAPHY……… xii

APPENDIX……….. xiii

ix

CF : to create fear or control the other participant’s feeling CT : to cover or keep the truth as a secret

MMn : (the violation) of maxim of manner MQl : (the violation) of maxim of quality MQn : (the violation) of maxim of quantity Op : opt out of a maxim

PDS : to persuade the other participants to do something PS : to plead the other participants

LANOKE INTAN PARADITA. The Analysis of Grice’s Non-observance Conversational Maxims Operating in Shrek. Yogyakarta. Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters, Sanata Dharma University, 2009

The study that is conducted in this thesis is aiming at the analysis of Grice’s Cooperative Principles which are constituted in a conversation. The analysis particularly discusses the non-observance of conversational maxims in the conversation, which are described in four different ways that are by flouting, violating, opting out, and infringing over maxim(s). This study however will focus on the violation and the opt out.

The object of the study is a comedy cartoon film entitled Shrek. This film is chosen to be the object since there is a close relationship between comedy or humor and the non-observance of the Cooperative Principles specifically the violation and opt out. Moreover, this film is regarded as the best cartoon film ever made.

In doing the analysis, the writer formulates two problem formulations as the frame for the whole analysis. The first problem formulation is how the participants in Shrek violate and opt out over maxim(s). The second problem formulation is what possible reasons which may prompt the participants to either violate or opt out of maxim(s).

The study is using an empirical study which data are taken from Shrek dialog which is transcribed into a film script. The data then are compared with the printed script which is collected from the internet. To do the analysis, the writer uses a pragmatic approach since the study involves how the participants use the language to attain their goals and how they interpret the utterances that are conveyed.

The analysis shows that there are thirteen violations and opts out. The violation of the maxim of manner becomes the maxim violated most, which occurs four times out of eleven violations in nine dialogs. Based on the analysis, there are five reasons as the main backgrounds which prompt the participants to fail in following or observing the maxims. The reasons are to create fear or control the other participants’ feeling, to plead the other participants, to repair what the participants has already said, to cover the truth or keep the truth as a secret, and to persuade the other participants to do something.

x

xi

LANOKE INTAN PARADITA. The Analysis of Grice’s Non-observance Conversational Maxims Operating in Shrek. Yogyakarta. Department of English Letters, Faculty of Letters, Sanata Dharma University, 2009

Penelitian yang dilakukan dalam penulisan skripsi ini bertujuan untuk menganalisis prinsip kerja sama yang dikemukakan oleh Grice yang terdapat dalam sebuah percakapan. Secara khusus, analisis dalam skripsi ini mendiskusikan tentang non-obsarvance dari prinsip kerja sama dalam percakapan yang digambarkan dalam empat cara yang berbeda, yaitu flouting, violating, opting out, dan infringe. Akan tetapi, penelitian ini akan secara khusus membahas violating dan opting out.

Objek dalam penelitian ini adalah film kartun komedi yang berjudul Shrek. Film ini dipilih sebagai objek penelitian karena adanya hubungan yang dekat antara komedi atau humor dengan non-obervance pada prinsip kerja sama Grice, khususnya violating dan opting out. Terlebih lagi, film ini dianggap sebagai salah satu film paling sukses yang pernah dibuat.

Untuk melakukan analisis, penulis memformulasikan dua rumusan masalah sebagai kerangka untuk keseluruhan analisis. Rumusan pertama adalah bagaimana para pelaku tindak tutur dalam film Shrek melakukan violation dan opt out. Rumusan masalah yang kedua adalah alasan apa yang mungkin dimiliki oleh para pelaku tindak tutur sehingga mereka melakukan violation dan opt out terhadap maksim-maksim dalam prinsip kerja sama..

Penelitian ini merupakan penelitian empiris. Dara yang digunakan didapat dari percakapan Shrek yang diterjemahkan ke dalam naskah film. Data ini kemudian dibandingkan dengan naskah tertulis yang didapat dari penelusuran internet. Dalam melakukan analisis, penulis menggunakan pendekatan pragmatik karena penelitian ini berkaitan dengan bagaimana para pelaku tindak tutur menggunakan bahasa untuk mencapai tujuan-tujuan mereka dan bagaimana mereka menginterpretasi kalimat-kalimat yang diutarakan.

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION

A. Background of the study

In human daily activities, people always make interaction with others. They use various media to exchange information and convey meaning. One common way is by having conversation with others. In fact, many researches on language recognize that individuals, social groups, and speech communities produce different amounts of conversation (Asher, 1994: 747).

The participants of a conversation frequently mean much more than their words actually say (Thomas 1995 in Dornerus, 2005:1). Therefore the listeners should interpret in order to understand what the speaker intends to say. When the hearers try to understand the implied meaning, they are trying to find the implicature of the utterances uttered by the speaker that is ‘the implication of the utterance not directly stated in the words but hinted at for the hearer to interpret’ (Dornerus, 2005: 4). Based on the context the participants are communicating, Grice defines two kinds of implicature that are conventional and conversational implicature (Dorenus 2005 and Kalliömaki 2005). The conventional implicature has the same implication no matter what the context is, while conversational implicature is generated directly by the speaker depending on the context (Thomas in Dornerus 2005: 4).

guidelines for the participants in order to have an efficient and effective use of language. These guidelines are constituted in four basic maxims that are the maxim of quality, quantity, relevance, and manner (Kalliömaki, 2005:22). These maxims generate a general term called as Cooperative Principle. The principle is:

Make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged (in Mooney, 2003:1).

The participants generally will not generate any implicature if they are following or successfully observe the principle, because there will be no difference upon what is said and what is implied (Kalliömaki, 2005: 24). However, in some occasion the participants intentionally make a distinction from what they say to what they mean. This case of non-observance of the maxims are in fact is a frequent use within a conversation. Grice describes four ways of non-observance that are flouting a maxim, violating a maxim, opting out of observing a maxim, and infringing a maxim (Asher 1994 and Kalliömaki 2005).

The object to study in this thesis is a conversation of a comedy cartoon film entitled Shrek which is transcribed into a film script. A comedy film is chosen based on the fact that there is a close relationship between the violations of the maxim in Grice’s cooperative principles with humor (Attardo, 1994: 271) since Grice himself has used a humorous example (Attardo, 1994: 205). Moreover, this film is a box office film which is considered as one of the most successful cartoon film ever made.

The example of the conversation which participant (Gingerbread Man) violates the maxim of manner is seen below:

Turn Participants Dialogs

128 Farquaad That's enough. He's ready to talk.

129 Farquaad (he picks up the Gingerbread Man's legs and plays with them) Run, run, run, as fast as you can. You can't catch me. I'm the gingerbread man.

130 Gingerbread Man You are a monster

131 Farquaad I'm not the monster here. You are. You and the rest of that fairy tale trash, poisoning my perfect world. now, tell me! Where are the others?

132 Gingerbread Man Eat me! (He spits milk into Farquaad's eye.)

(http://www.imsdb.com/scripts/Shrek.html)

Farquaad about where his friends are hiding. This remark is seen as his unwillingness to cooperate since this remark is a kind of remark blocking any further turn within a conversation and at the same time shows a dispreferred second turn from Gingerbread Man.

As a matter of fact, like the example above, there will be many occasions when the participants fail to observe the maxims, especially the flouting of a maxim since there are lots of conversation in which participants convey implicit meaning and expect the listeners to understand it. However, this study will focus on the non-observance categories of violating and opting out of the maxim. Therefore, the conversations used in the analysis will only cover the conversations in which the participants are regarded as intentionally violating and opting out of the conversational maxim.

B. Problem formulation

The problems are formulated as follow:

1. How are the maxim(s) violated and opted out in Shrek’s conversation? 2. Why the participants in Shrek’s conversation violate and opt out of the

maxim?

C. Objective of the study

the discussion is going to see what possible reasons may prompt the participants so that they prefer to violate or opt out of a maxim.

D. Definition of terms

For perceiving a clear understanding upon the discussion, it is better to know the meaning of terms used throughout the discussion:

1. Conversation

Conversation is discourse mutually constructed and negotiated in time between speakers; it is usually informal and unplanned (Cutting, 2002: 28).

2. Conversation analysis

Cutting (2002: 24) explains that conversational analysis is an approach to looking at the structure of discourse (in this case is film script), which studies the way that what speakers say dictates the type of answer expected, and that speakers take turns when they interact.

3. Cooperative principles

Cooperative Principle according to Grice is to ‘make your conversational contribution such as is required, at the stage at which it occurs, by the accepted purpose or direction of the talk exchange in which you are engaged’ (in Mooney, 2003:1).

4. Conversational maxims

of quality, maxim of quantity, maxim of relation, and maxim of manner. Usually the maxims are regarded as unstated assumption in conversation (Yule, 1996: 37).

5. Violating maxims

Violation is the unostentatious non-observance of a maxim (Asher, 1994: 756). A speaker is violating a maxim when they know that the listener will not know the truth and will only understand the surface meaning of the words. They intentionally generate a misleading implicature (Cutting, 2002: 40), that what is inferred is not mentioned (Yule, 1996: 40).

6. Opting out of the maxims

A speaker opts out of observing a maxim by indicating unwillingness to cooperate in the way that the maxim requires (Asher, 1994: 757). He or she cannot reply in the way expected, for example is their unwillingness to cooperate for legal or ethical reason (Cutting, 2002: 41). The speakers opt out in order not to give false implicature which lead them violate the maxims.

7. Non-observance conversational maxim

CHAPTER II

THEORETICAL REVIEW

A. Review on Related Studies

Since conversation analysis is not a new study, there has been many studies and research concerning this subject in relation with many fields of study. Related to linguistics, conversation analysis is broadly developed and also used for understanding conversation of doctor-patient, lecturer-student, and buyer-seller.

In Literate Journal on Literature, Language, and Cultural Studies (2007), Eko Prasetyo Humanika writes “Conversational Analysis” addressing the nature of conversation between a teacher and a student which is full of denials and implicit meanings. Using an empirical study, he focuses his analysis in the formal aspect of a conversation which uses six basic principles of conversation that are speech acts, Grice’s maxim or principle of cooperative behaviour, adjacency pairs, turn taking, repair, and overall organization, as the tools for doing the analysis.

Humanika uses a conversation in an examination which is taken from

Humanika uses the six basic principles of conversation to analyze the denials and implicit meanings. He studies the conversation by analyzing each sentence and observes what basic principle(s) is applied. He finds that all of the basic principles are applied within the conversation. At the end of his analysis, he states that the conversation is dominated by denials and implicit meanings.

Related to Humanika studies, the analysis to do in this paper will also discuss the formal aspects of the conversation. However, the discussion will be narrowed to Grice’s cooperative principles, particularly how the principles are violated and opted out of the conversation. Moreover, the discussion will also cover the possible reasons for the participants to do the violation and opt out in the conversation.

B. Review on Related Theories

There are two main theories to use throughout the analysis. The first theory will concern the local organization within a conversation. The second theory is Grice’s cooperative principles. These two theories will be used jointly to discuss the first and the second question stated in the problem formulation.

1. Theory of local organization operating within a conversation

between speakers; it is usually informal and unplanned. A talk may be classed as a conversation when:

a. It is not primarily necessitated by a practical task

b. Any unequal power of participants is partially suspended c. The number of the participants is small

d. Turns are quite short

e. Talk is primarily for the participants not for an outside audience (Thomas in Cutting, 2002: 28)

For example, a doctor-patient, a TV quiz show, and teacher-student exchange are not conversation because they do not have all properties listed above. There is an unequal power balance in doctor-patient exchange since the doctor takes control of the event and is necessitated by a practical task of diagnosing and prescribing. The unequal power also occurs in the exchange of teacher-student in a class. While the TV quiz show is certainly for outside audience.

In a conversation, there is always local management organization operating within every conversation. The local management is a set of convention which control the turns, that is getting turns, keeping them, or giving them away (Yule, 1996: 72), The local management is governed by some basic principles that are turn taking, adjacency pairs, and sequences. (a) Turn taking

the floor. ‘Any possible change-of-turn point’ (Yule, 1996: 72) or ‘a point in a conversation where a change of turn is possible’ (Cutting, 2002: 29) is called a Transition Relevance Place (TRP).

In having the conversation, sometimes the participants try to speak at the same time, which is called overlap (Yule, 1996: 72), as the reverse of overlap, sometimes there is an absence of vocalization between the participants which is called as silence (Humanika, 2007: 73). If one speaker actually turns over the floor to another and the other does not speak, which produce a silence, intending to carry meaning, the silence is called as an attributable silence (Cutting, 2002: 29).

(b) Adjacency pairs

There is always pattern in a conversation which apparently happens automatically. The pattern is likely to be question-answer, offer-accept, blame-deny, apology-minimization, etc. This pattern is called as adjacency pairs at where the participants are having the turn taking system and thus operating the first and second part of the conversation.

Schegloff and Sacks as in Levinson (1983: 303), characterizes adjacency pairs as two utterances that are:

(i) adjacent

rs art (ii) produced by different speake

(iii) ordered as first part and second p

(iv)typed, so that a particular first part requires a particular second (or range of second parts) – e.g. offers require acceptances or rejections, greetings require greetings, and so on,

‘having produced a first part of some pair, current speaker must stop speaking, and next speaker must produce at that point a second part to the same pair.’ (Levinson, 1983: 303-304)

(i) Preference structure

Whenever the first part creating an expectation of a particular second part, the structure is called as preference structure, that each part has a preferred and a dispreferred response. A dispreferred response usually tends to be refusal or disagreement (Cutting, 2002: 30). Some linguists have generalized the characteristics of dispreferred seconds in which turns typically exhibit at least a substantial number of the following features: (a) delays: (i) by pause before delivery, (ii) by the use of a preface,

(iii) by displacement over a number of turns via use of repair initiators or insertion sequences

(b) prefaces: (i) the use of markers of announcers of dispreferreds like Uh and Well, (ii) the production of token agreements before disagreements, (iii) the use of appreciations if relevant (for offers, invitation, suggestions, advice), (iv) the use of apologies if relevant (for requests, invitations, etc), (v) the use of qualifiers (e.g. I don’t know for sure, but..), (vi) hesitation in various forms, including self editing

(c) accounts: carefully formulated explanations for why the (dispreferred) act is being done

(d) declination component: of a form suited to the nature of the first part of the pair, but characteristically indirect or mitigated (Levinson, 1983: 334)

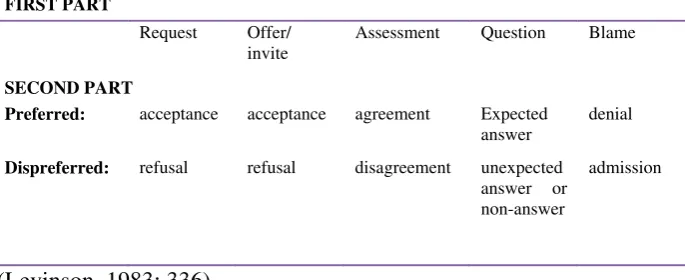

and content found across a number of adjacency pair seconds which is described in the following table:

Table 1. Correlation of content and format in adjacency pair seconds

Preferred: acceptance acceptance agreement Expected

answer

denial

Dispreferred: refusal refusal disagreement unexpected

answer or non-answer

admission

(Levinson, 1983: 336)

Based on the table, therefore, when a speaker makes a request, as the first part of a whole sequence of conversation, a listener can give two possible responses upon the request. This response is the second part of the sequence in which the listener can give the response either in a preferred structure, that is by accepting the request, or dispreferred structure, that is by refusing the request. These pairs can be repeated in the sequence.

(c) Sequences

Having the conversation, the participants are constructing certain sequences. The sequences can be pre-sequences, insertion sequences, and opening and closing sequences (Cutting, 2002: 31). (i) Pre-sequences

as invitations (I’ve got two tickets for the rugby match..’), pre-request (‘Are you busy tonight?’), and pre-announcements (‘You’ll never guess!’) (Cutting, 2004: 31).

(ii) Insertion sequence

ce

Often in a talk exchange, the first part does not immediately receive the second parts. There sometimes other sequences are embedded between the first and second part of the talk exchange. This insertion is called the insertion sequence. For example of insertion sequence is

A Do you want some of those cakes? (Turn 1) B Do they look good? (Turn 2)

A Er—no (Turn 3)

B No (Turn 4)

The first part (Turn 1) is actually responded in Turn 4, which within its sequence, Turn 2 and Turn 3 are embedded within the conversation.

(iii) Opening and closing sequen

for the second part, which exchange establishes an open channel for talk.

While there is usually a typical structure for opening sequence, the conversation also establish a general schema for the closing sequence, which in Levinson’s Pragmatics (1983: 317), might be represented as:

(a) a closing down of some topic, typically a closing implicative topic; where closing implicative topics include the making of arrangements, the first topic is monotopical calls, the giving of regards to the other family members, etc

(b) one or more pairs of passing turns with pre-closing items, like Okay, All right, So, etc

(c) if appropriate, a typing of the call as e.g. a favour requested and done (hence Thank you), or as a checking up on recipient’s state of health (Well I just wanted to know how you were), etc., followed by further exchange of pre-closing items

(d) a final exchange of terminal elements: Bye, Rights, Cheers, etc.

2. Theory of Cooperative Principles by Grice

It is assumed that in exchanging information via conversation the participants are following certain principles. This is often called as cooperation between the participants. The cooperation involves the assumption that the participants do not try to confuse, trick, or withhold relevant information from each other (Yule, 1996: 35) and often refer as following or able to observe the principles operating within the conversation. There are four conversational maxims which Grice proposes as what is formulated below:

Quantity: Make your contribution as informative as is required (for the current purposes of the exchange)

Do not make your contribution more informative than is required

Do not say what you believe to be false

Do not say that for which you lack adequate evidence Relation Be relevant

Manner Avoid obscurity of expression Avoid ambiguity

Be perspicuous

Be brief (avoid unnecessary prolixity) Be orderly

(Yule, 1996: 37)

Since the focus in this study is the failure of observing the maxim by violating and opting out, the flouting and infringing are not discussed any further.

(a) Violating the maxim

Based on Thomas (1995) that is quoted by Cutting (2002: 40), a speaker is violating a maxim when they know that the listener will not know the truth and only understand the surface meaning of the words. They intentionally generate a misleading implicature. A maxim violation is unostentatiously, quietly deceiving. The speaker deliberately supplies insufficient information, says something that is insincere, irrelevant or ambiguous.

(i) Violation of quantity maxim

The speakers violate the quantity maxim when they do not give the listener enough information to know what is being talked about, because they do not want the listener to know the truth. For example:

A Does your dog bite? B No.

A (Bends down to stroke it and gets bitten) Ow! You said your dog doesn’t bite!

B That isn’t my dog

(ii) Violation of quality maxim

If the speaker is intentionally being not sincere and giving wrong information, he or she is violating the maxim of quality. For example is in the case of Sir Maurice Bowra below:

‘When Sir Maurice Bowra was Warden of Wedham College, Oxford, he was interviewing a young man for a place at the college. He eventually came to the conclusion that the young man would not do. Helpfully, however, he let him down gently by advising the young man, ‘I think you would be happier in a larger—or a smaller—college’

If Sir Maurice Bowra, in the example above, knew that the young man did not realize that he had failed the interview because of his performance, and that if he knew that the young man would believe that it was the size of the college that it was the size of the college that was wrong to him, then he could be said to be telling a lie, because he violating the maxim of quality (Cutting, 2002:40). (iii) Violation of relevance maxim

A speaker is violating the maxim of relevance if the speaker says something in order to distract the listener. The distraction is by intentionally giving a misleading implicature, so that the speaker can change the topic and keep the truth covered. For example:

Husband How much did that new dress cost, darling?

The wife intends not to tell the husband about the price of the dress, thus she intentionally remarks with the utterances which are made in order to distract her husband and directly change the topic. (iv) Violation of manner maxim

Within a conversation, if a speaker says the utterance in obscure or vague reference and avoids giving a brief and orderly answer, he/ she could be regarded as violating the maxim of manner. The violation is intended in the hope that what is said could be taken as an answer and the matter could be dropped because the listener do not know the truth. Example:

X What would the other people say?

Y Ah well I don’t know. I wouldn’t like to repeat it because I don’t really believe half of what they are saying. They just get a fixed thing into their mind.

In the above sheltered home example, the old lady answer the interviewer’s question in a way that could be said to be violating the maxim of manner, in that she says everything expect what the interviewer wants to know. Her ‘half of what they are saying’ is an obscure reference to the other people’s opinion, and ‘a fixed thing’ contains a general noun containing vague reference. She may be using these expressions to avoid giving a brief and orderly answer, for the moment (Cutting, 2002:41).

(b) Opting out

wish to avoid generating a false implicature or appearing to be uncooperative.

Asher (1994: 797) added that,

‘When a speaker explicitly opts out of observing a maxim, she or he could be seen to provide privileged access into the way in which speaker normally attend to the maxims, which in turn offers prima facie evidence for Grice’s contention that there exists on the part of interactants a strong expectation that, cateris paribus and unless indication is given on the contrary, the cooperative principles and the maxims will be observed’ (Asher, 1994: 797)

Therefore, the speaker may wish to opt out of a maxim and drop the topic in order to make the listener not to have a false implicature, Moreover, by opting out a maxim the speaker may also seem to avoid in having conversation unless the listener will be able to recognize the maxim operating in the speaker’s utterance.

(c) Flouting a maxim

A speaker is flouting a maxim when they appear to fail in observing the maxims but is not intending to deceive or misleading, but because the speaker ‘wishes to prompt the listener to look for a meaning which is different from, or in addition to, the expressed meaning’ (Asher, 1994: 754).

(d) Infringing

drunkenness, excitement), having a cognitive impairment, or simply incapable of speaking clearly (Cutting, 2002: 41).

When a speaker is infringing a maxim, he or she does not have any intention to generate implicature, deceive, or mislead the listener (Asher, 1994: 757).

C. Theoretical Framework

CHAPTER III METHODOLOGY

A. Object of the Study

The object of this study is conversation of a cartoon film entitled Shrek which is transcribed into a film script. The story of the film is a story adapted from William Steig’s book and is written by Ted Elliot. This film is considered one of the most successful films produced by Dream Works Ltd., a well-known production house. As a fact, Shrek wins some prestigious and popular awards such as Oscar (2002 as a best animated feature), BAFTA Film Award (2002 as a best screenplay-adopted) and nominated in Golden Globe (2002 as best motion picture-musical or comedy), MTV Film Award (2002 as best comedic performance and best film), and another 27 wins and 42 nominations <http://us.imdb.com/title/tt0126029/> (1 March 2008).

This film is a parodied fairy tale which mainly tells about a love story between Shrek, who is an ogre, and Fiona, a princess of Far Far Away Kingdom. Half of the events in the film tell about Shrek’s journey with his friend, Donkey, rescuing Princess Fiona in order to get Shrek’s swamp back. Another half of this film tells about how actually Shrek and Princess Fiona accidentally in love and how these characters finally accept each other.

B. Approach of the Study

said by the speaker. This approach requires ‘a consideration of how speakers organize what they want to say in accordance with who they are talking to, where, when, an under what circumstances’ (Yule, 1986: 3). In other words, using the pragmatic point of view, the study to do in this thesis will look at how the conversation is organized by the participants and what may prompts them to organize in such a way, regarding the specific context of the conversation in accordance with the non-observance maxims introduced by Grice.

C. Method of the study

The study is an empirical study as it uses factual data (Anderson, 2001: 22). The data are film conversations which are transcribed into a film script. The data are primary sources as they are taken directly without any extraction from other source and because they are a ‘first-hand accounts of experimentation and investigation’ (Anderson, 2001: 22).

D. Research Procedure 1. Data collection

(Creswell, 2003: 187). During the transcription process some differences of the conversation between the film and the script obtained from the internet occur. These differences are then match up with the film.

2. Data analysis

There are two main steps for analyzing the film transcription. The first step is to segment the transcription based on its speech events. Using both theories, there will be non-observance conversational maxim identification for each segment. The non-observance is seen when there are ‘any turns which are breaking one or more of the Gricean maxims’ (Brumark, 2004:13). After identifying the existence of non-observance conversational maxim, each of them will be coded using the code such as: 01/1/MMn/CT. This code is read as: this is the non-observance conversational maxim number one which is occurred in line 1. MMn means that the non-observance conversational maxim identified is the violation of maxim of manner. CT is read as covering the truth which shows the reason of the participants to do a violation or opt out. The other abbreviation is listed on the table of abbreviation.

cooperative principle is used to value and identify the conversation, whether it gives sufficient information which is given truthfully and in an order.

CHAPTER IV ANALYSIS

This chapter will discuss two main ideas of analysis based on the problem formulation addressed in chapter two. There will be two sub chapters discussing each problem formulation. The first sub-chapter will deal with how each character in the film, which hereinafter referred as participant, violates the maxim of conversation. Meanwhile, the second sub-chapter will deal with some possible reasons of each participant for violating the maxims.

A. The analysis of maxims violated 1. The violation of maxim of quantity

01/6-8/MQn/CF

Turn Participants Dialogs

2 Man 1 Think it's in there? 3 Man 2 All right. Let's get it!

4 Man 1 Whoa. Hold on. Do you know what that thing can do to you?

5 Man 3 Yeah, it'll grind your bones for it's bread. 6 Shrek (Shrek sneaks up behind them and laughs)

Yes, well, actually, that would be a giant. Now, ogres, oh they're much worse.

They'll make a suit from your freshly peeled skin.

7 Men No!

8 Shrek They'll shave your liver. Squeeze the jelly from your eyes! Actually, it's quite good on toast.

in turn (4) by Man 1 and is answered in turn (5), that ogres will grind Man 1’s bones for their bread. This conversation is suddenly interrupted by Shrek who inserts himself in the dialog. He utters the disagreement upon Man 3’s opinion of what ogres can do to them like what he says: ‘Yes, well, that would be a giant’. Moreover, in this turn he also gives his personal opinion upon what ogres do like what he stated in ‘They’ll make a suit from your freshly peeled skin’.

This explanation is denied by the men, but is ignored by Shrek since he does not stop the explanation. Instead, he adds more information that ogres will shave the men’s liver and squeeze the jelly from their eyes as well (Shrek, 2001). All of these information, indeed, follows the adjacency pairs, that is when the first speaker’s assessment, in this case is Man 3’s answer in turn (5), is commented by the second speaker’s disagreement (Shrek’s turn) which serves as his dipreferred second sequence (Levinson, 1983:336).

However, both in turns (6) and (8), Shrek apparently fails to observe the maxim which consequently makes him violate the conversational maxim, particularly quantity maxim. In the time he gives the explanation of why he disagrees with Man 3, Shrek also gives his personal opinion which is not needed to be inserted in his explanation such as ‘Now, ogres, oh they’re much worse’ in turn (6) and ‘Actually it’s quite good on toast’ in turn (8).

quantity, of course he does not need to add his personal opinion. Because of his choice to give too much information, Shrek then is regarded as violating the maxim of quantity. The next data will also discuss the violation upon quantity maxim.

02/49-53/MQn/PS

Turn Participants Dialogs

47 Donkey Can I say something to you? Listen, you was really, really, really somethin' back here. Incredible!

48 Shrek Are you talkin' to...(he turns around and Donkey is gone) me? (he turns back around and Donkey is right in front of him.) Whoa! 49 Donkey Yes. I was talkin' to you. Can I tell you

that you was great back here? Those guards! They thought they was all of that. Then you showed up, and bam! They was trippin' over themselves like babes in the woods. That really made me feel good to see that.

50 Shrek Oh, that's great. Really. 51 Donkey Man, it's good to be free.

52 Shrek Now, why don't you go celebrate your freedom with your own friends? Hmm? 53 Donkey But, uh, I don't have any friends. And I'm

not goin' out there by myself. Hey, wait a minute! I got a great idea! I'll stick with you. You're mean, green, fightin'

machine. Together we'll scare the spit out of anybody that crosses us.

I say something to you?’ turn (47) and ‘Can I tell you that you was great back there?’ turn (49). His pre-announcements in fact are always in a form of asking permission to say something to Shrek and then followed with the announcements. In addition, his announcements mostly are compliments to Shrek because he drives the army off.

Since the beginning of the conversation, none of Donkey’s pre-announcements and pre-announcements is replied by Shrek. This happens because every time he finishes asking the permission, Donkey does not give Shrek any chance to reply it. This fact, indeed, shows the occurrence of a violation upon a maxim, namely the maxim of quantity, which will be explained as follow.

In turn (49), after asking the permission Donkey does not give Shrek any chance to say whether he gives the permission or not. Moreover Donkey directly utters what he wants to tell Shrek. The information that Shrek is great back there and the explanation which is stated in his turn: ‘Those guards! They thought they was all of that. Then

you showed up, and bam! They was trippin' over themselves like babes in the woods. That really made me feel good to see that.’ indeed are the information that Shrek never asks, which means that Shrek does not need these information. Suppose that Donkey gives enough information, he will only reply ‘Yes. I was talking to you’ as his answer for Shrek’s question in turn (48): ‘Are you talkin’ to...me?’.

on Shrek’s turn in (52): ‘Why don’t you celebrate your freedom with your own friends?’, Shrek needs an answer to explain why Donkey does not go and celebrate his freedom with his own friends. Instead, Donkey gives not only the explanation but also an idea that he is better to be with Shrek because by being together they will scare the spit out of everybody that crosses them (Shrek, 2001). In case that Donkey gives the information that Shrek needs, he will only gives the explanation of why he does not go, that is because he does not have any friends like what is stated in turn (53) and does not need to add any more information.

Because Donkey gives too many information than what is needed by Shrek, he is regarded as violating the maxim of quantity.

2. The violation of maxim of quality 03/71/MQl/TR

Turn Participants Dialogs

67 Donkey Man, I like you. What's you name?

68 Shrek Uh, Shrek

69 Donkey Shrek? Well, you know what I like about you Shrek? You got that kind of I-don't-care-what-nobody-thinks-of-me thing. I like that. I respect that, Shrek. You all right. (They come over a hill and you can see Shrek's cottage.) Whoa! Look at that. Who'd want to live in a place like that? 70 Shrek That would be my home.

This dialog happens in the same time when Donkey finally comes with Shrek. During their walk, Donkey seems to create an image that he likes Shrek and is not afraid of being together with him as seen in turn (69): ‘Well, you know what I like about you Shrek? You got that

kind of I-don't-care-what-nobody-thinks-of-me thing. I like that. I respect that, Shrek. You all right.’ In the next sentence, Donkey utters a sudden remark upon a cottage he sees which he does not know yet that the cottage belongs to Shrek. By uttering ‘Whoa! Look at that.’ Donkey shows his surprise of seeing a cottage ‘like that’ and by giving the remark ‘Who’d want to live in a place like that’ Donkey shows that in his opinion the cottage he is looking at is not a nice one to live at.

Moreover, Donkey’s use of the conjunction and is intended to mislead Shrek so that he will believe that what Donkey means is that he has a lovely and beautiful cottage. The fact that Donkey tells something that he believes as false and his attempt to mislead the implicature from his utterance in turn (71) make him regarded as violating the quality maxim. The next data will discuss another violation of quality maxim.

09/492/MQl/CT

Turn Participants Dialogs

488 Shrek There it is, Princess. Your future awaits you.

489 Fiona That's DuLoc?

490 Donkey Yeah, I know. You know, Shrek thinks Lord Farquaad's compensating for something, which I think means he has a really...(Shrek steps on his hoof) Ow! 491 Shrek Um, I, uh- - I guess we better move on. 492 Fiona Sure. But, Shrek? I'm - - I'm worried

about Donkey.

493 Donkey What?

494 Fiona I mean, look at him. He doesn't look so good.

495 Donkey What are you talking about? I'm fine.

In the dialog above Fiona violates the maxim of quality. She violates the quality maxim since she tells the information that she actually believes as something untrue, which will be explained below.

(Levinson, 1983: 337). Meaning to say, this is the turn which prompts anyone to respond Shrek.

Regarding the fact in the film, this scene pictures that Fiona and Shrek begin to get attracted to each other and that they will soon reach DuLoc. It means they will say good-bye soon. In order to have a bit more time to be together, Fiona uses the chance that is accidently ‘provided’ in Shrek’s previous turn. Fiona takes the chance to respond Shrek’s opinion by giving a remark which is seemed to approve Shrek that they are better to move on.

Indeed, her approval leads to her disagreement which is seen in her use of a yes, but format of response, or a disagreement prefaced by a token agreement (Levinson, 1983: 338) which is constituted in her turn (492): ‘Sure. But, Shrek?’ and gives an explanation that they are better to have a rest because Donkey is not in a good condition as in her next utterance: ‘I’m—I’m worried about Donkey’.

information, Fiona therefore is regarded as violating the maxim of quality.

.

3. The violation of maxim of manner 05/136-142/MMn/CT

Turn Participants Dialogs

133 Farquaad I've tried to be fair to you creatures. Now my patience has reached its end! Tell me or I'll...(he makes as if to pull off the Gingerbread Man's buttons)

134 Gingerbread Man No, no, Not the buttons. Not my gumdrop buttons.

135 Farquaad All right then. Who's hiding them? 136 Gingerbread Man Okay, I'll tell you. Do you know the

muffin man? 137 Farquaad The muffin man? 138 Gingerbread Man The muffin man.

139 Farquaad Yes, I know the muffin man, who lives on Drury Lane?

140 Gingerbread Man Well, she's married to the muffin man.

141 Farquaad The muffin man? 142 Gingerbread Man The muffin man!

143 Farquaad She's married to the muffin man.

By having the ‘agreement’, Farquaad will consequently expect that Gingerbread Man has already cooperated with him. In fact, however, Gingerbread Man does not cooperate like what is expected. This is seen in his following utterances throughout the conversation. Gingerbread Man uncooperative manner is first seen in his utterance of asking Farquaad ‘Do you know the muffin man?’ in turn (136) which shows a dispreferred second turn. This utterance shows his dispreferredness because Gingerbread Man does not give Farquaad’s expected answer. In case that Gingerbread Man is willing to cooperate he will directly tell Farquaad where the other fairy tale creatures hide (the adjacency pairs of question-answer). However, in fact, he gives the answer which form is a ‘yes or no’ question which consequently needs Farquaad to answer it (question-question).

It seems that Gingerbread Man has a good opportunity to be obscure since Farquaad seems to be unsure about who the muffin man is. Therefore, in his turn (137) Farquaad asks Gingerbread Man back, which question is in fact merely a repetition of the muffin man’s name, ‘The muffin man?’ in turn (137). Because of Farquaad’s uncertainty, Gingerbread Man takes the chance not to tell Farquaad directly about the other fairy tale creatures where about by repeating the name of the muffin man himself, ‘The muffin man’ in turn (138).

obscure answer: ‘Well, she’s married to the muffin man’, which does not help Farquaad to know this particular muffin man. This is seen in Farquaad’s turn (141) where he once again repeats the name of the muffin man in order to assure himself that they are talking the same muffin man. Eventually, this question is answered by Gingerbread Man with another turn (142): ‘The muffin man!’.

At the end of the conversation, it is seen that Gingerbread Man never tells or even gives just a hint about where his friends hide to Farquaad. Gingerbread Man intentionally diverts Farquaad by giving the answer not in a brief way. Moreover, he distracts Farquaad’s focus by never giving a direct answer to what Farquaad asks. Therefore, Gingerbread Man is regarded as violating the maxim of manner. The other violations of maxim of manner is discussed in 06/249/MMn/PDS and 11/514-517/MMn/CT.

06/249/MMn/PDS

Turn Participants Dialogs

227 Donkey Uh, Shrek? Uh, remember when you said ogres have layers?

228 Shrek Oh, aye

229 Donkey Well, I have a bit of a confession to make. Donkeys don't have layers. We wear our fear right out there on our sleeves.

230 Shrek Wait a second. Donkeys don't have sleeves. 231 Donkey You know what I mean.

232 Shrek You can't tell me you're afraid of heights. 233 Donkey No, I'm just a little uncomfortable about

being on a rickety bridge over a boiling like of lava!

235 Donkey Really? 236 Shrek Really, really.

237 Donkey Okay, that makes me feel so much better. 238 Shrek Just keep moving. And don't look down. 239 Donkey Okay, don't look down. Don't look down.

Don't look down. Keep on moving. Don't look down. (he steps through a rotting board and ends up looking straight down into the lava) Shrek! I'm lookin' down! Oh, God, I can't do this! Just let me off, please! 240 Shrek But you're already halfway.

241 Donkey But I know that half is safe!

242 Shrek Okay, fine. I don't have time for this. You go back.

243 Donkey Shrek, no! Wait!

245 Shrek Just, Donkey - - Let's have a dance then, shall me? (bounces and sways the bridge) 246 Donkey Don't do that!

247 Shrek Oh, I'm sorry. Do what? Oh, this? (bounces the bridge again)

248 Donkey Yes, that!

249 Shrek Yes? Yes, do it. Okay. (continues to bounce and sway as he backs Donkey across the bridge)

250 Donkey No, Shrek! No! Stop it! 251 Shrek You said do it! I'm doin' it.

252 Donkey I'm gonna die. I'm gonna die. Shrek, I'm gonna die. (steps onto solid ground) Oh!

This dialog occurs when Shrek and Donkey arrive at the gate of the tower at where Fiona is kept by the dragon. To be able to reach the tower they have to pass a bridge above a boiling lava. At the time they arrive to the bridge, Donkey is seen to refuse passing it. His refusal is identified in his pre-announcement in turns (227)-(229) and the announcement of his the refusal in turns (231)-(233).

he said in turn (234): ‘Come on, Donkey. I'm right here beside ya, okay?

For emotional support. We'll just tackle this thing together one little baby step at a time.’

This support indeed successfully makes Donkey to pass the bridge until half of its way. Yet, arriving to the middle of the bridge Donkey gives up and wants to go back. Responding Donkey unwillingness to move on, Shrek apparently approves Donkey’s refusal like in turn (242) when he utters ‘Okay, fine’. However, the following turns show that Shrek in fact rejects Donkey’s refusal by giving a new way to force Donkey to pass the half bridge. The new way is to sway and bounce the bridge which is initiated by Shrek’s creation of a new topic as seen in turn (245): ‘Just Donkey--Let’s have a dance then, shall me’ that is used to divert Donkey’s attention.

however, intentionally refers this pronoun as an agreement from Donkey to keep swaying and bouncing the bridge.

Similar sequences also happen in turns (249)-(251). In turn (249) Shrek once again asks for clarification upon Donkey’s agreement in ‘Yes, that!’ Shrek pretends that he wants to clarify whether what Donkey means with his ‘yes’ is to keep swaying and bouncing the bridge. However, at the same time Donkey has got no chance to give any response before Shrek sways and bounces the bridge. Thus, without any clarification from Donkey, Shrek is ‘free’ to intentionally miss-infer the ‘silence’ to keep swaying and bouncing the bridge.

Responding to Shrek’s action, Donkey tries to re-request him to stop the sway and bounce as in turn (250): ‘No, Shrek! No! Stop it!’ In fact, Shrek justifies himself that he is doing what Donkey wants, that is to sway and bounce the bridge as what he says in (251): ‘You said do it! I’m doin’ it’.

11/514-517/MMn/CT

Turn Participants Dialogs

510 Shrek (They smiles at each other.) Um, Princess?

511 Fiona Yes, Shrek?

512 Shrek I, um, I was wondering...are you...(sighs) Are you gonna eat that?

513 Donkey (chuckles) Man, isn't this romantic? Just look at that sunset.

514 Fiona (jumps up) Sunset? Oh, no! I mean, it's late. I-It's very late.

515 Shrek What?

516 Donkey Wait a minute. I see what's goin' on here. You're afraid of the dark, aren't you? 517 Fiona Yes! Yes, that's it. I'm terrified. You

know, I'd better go inside

518 Donkey Don't feel bad, Princess. I used to be afraid of the dark, too, until - - Hey, no, wait. I'm still afraid of the dark.

The dialog above tells how Fiona tries to cover her form as an ogre. Her effort to cover the fact, as seen in the dialog, makes her to violate the maxim of manner since she becomes ambiguous in giving some statements as will be explained below.

The violation is first seen in her turn (514). As what is stated before, Fiona tries to hide her ogre form which will always come in every sunset. However, in turn (514) Fiona looks so surprised that it is already sunset which means that within a few minute she will change into an ogre.

The repetition of ‘It’s late’ into ‘I-It's very late’ indeed shows her anxiety as well. However, using Donkey’s assessment in turn (516) that Fiona is afraid of the dark, she gets the advantage in her next turn to use the pronoun it to intentionally mislead Shrek and Donkey about the reason of her anxiety. This pronoun, in fact, has two meanings. The first meaning is Shrek and Donkey’s assumption that Fiona’s anxiety is caused by Fiona’s fear of the dark, nothing more than it, as a result from his assessment in turn (516). The other meaning is the real reason of Fiona’s fear of the dark that is the fact that she will change into an ogre. By using this pronoun, it seems that Fiona justifies Donkey’s assessment as in her statement: ‘Yes! Yes, that’s it’ which successfully mislead Shrek’s and Donkey’s implicature of the pronoun it.

Because Fiona intentionally misleads the implicature by becoming ambiguous in her use of the pronoun it in order to make Shrek and Donkey will only know the literal meaning and do not curious upon her anxiety in her expression toward the coming sunset, Fiona is regarded as violating the maxim of manner.

4. Opting out 04/132/Op/CT

Turn Participants Dialogs

128 Farquaad That's enough. He's ready to talk.

129 Farquaad (he picks up the Gingerbread Man's legs and plays with them) Run, run, run, as fast as you can. You can't catch me. I'm the gingerbread man.

130 Gingerbread Man You are a monster

poisoning my perfect world. Now, tell me! Where are the others?

132 Gingerbread Man Eat me! (He spits milk into Farquaad's eye.)

The dialog above occurs when Farquaad interrogates Gingerbread Man in order to know where the other fairy tale creatures hide. Farquaad starts the interrogation by imitating the running Gingerbread Man as a form of threat in turn (129). This threat is interrupted by Gingerbread Man by mocking Farquaad that he is a monster.

This interruption serves as a blame for Farquaad as well since he designates many of fairy tale creatures. However, Farquaad denies the blame as seen in turn (131): ‘I’m not the monster here,’ Even he blames Gingerbread Man back in his statement: ‘You are (the monster). You and the rest of that fairy tale trash, poisoning my perfect world.’

Farquaad’s next sentence, as seen in turn (131) is a type of a direct speech act namely directives speech act which is intended to make the hearer, in this speech event is Gingerbread Man, to do what he asks (Yule, 1996: 55). This order, however, replied by Gingerbread Man in the way that Farquaad never expects. Instead of telling Farquaad where his friends are hiding, Gingerbread Man answer Farquaad’s order by a reply: ‘Eat me!’ which in fact blocks Farquaad’s chance to request or give him any more orders. This blocking answer also serves as a sign of his dispreferred second turn.

with Farquaad. Gingerbread Man consequently is regarded as dropping the conversation out and is opting out of a maxim. Moreover, his answer is a common answer to follow the ethic that he shall not betray his friends by telling where they are hiding. This type of answer usually puts the speaker to opt out of a maxim because he or she does not want to generate any further implicature or inferences which will enable the hearer to observe any maxim operating within the conversation (Asher, 1934:797). Another opting out is discussed below.

08/384-392/Op/CT

Turn Participants Dialogs

377 Donkey (heaves a big sigh) Hey, Shrek, what we gonna do when we get our swamp anyway?

378 Shrek Our swamp?

379 Donkey You know, when we're through rescuing the princess.

380 Shrek We? Donkey, there's no "we". There's no "our". There's just me and my swamp. The first thing I'm gonna do is build a ten-foot wall around my land.

381 Donkey You cut me deep, Shrek. You cut me real deep just now. You know what I think? I think this whole wall thing is just a way to keep somebody out.

382 Shrek No, do ya think?

383 Donkey Are you hidin' something? 384 Shrek Never mind, Donkey.

385 Donkey Oh, this is another one of those onion things, isn't it?

394 Shrek Everyone! Okay?

395 Donkey (pause) Oh, now we're gettin' somewhere.(grins)

The dialog 08/384-392/Op/CT shows both Donkey’s attempt to get information from Shrek and Shrek’s trial to hide the information and close the conversation. In turn (381), Donkey assumes that Shrek is trying to ‘keep somebody out’ or even hiding something from him as seen in turn (383): ‘Are you hiding something?’. Starting from this turn, Donkey’s next turns are dominated with utterances in form of questions as constituted in turns (385), (387), (389), and (393) which show his curiosity upon what thing Shrek may hide from him.

However, as it is seen in the conversation as well, Shrek does not want to discuss it with Donkey. His unwillingness is seen in some of his attempt to close the conversation. His first attempt is in turn (384): ‘Never mind, Donkey.’ which means that Donkey does not have ‘to think and consider it’ (Hornby, 1995:240). By giving such remark to Donkey’s question, Shrek intends to close the conversation immediately and at the same time avoids any chance for Donkey to infer something. However, as it is seen in the next turn, Donkey indeed infers that the problem Shrek hides is related to the ‘onion things’ that they have discussed before.. Therefore, Shrek’s first attempt to close the conversation is fail.

‘Donkey, I’m warning you.’ However, this turn is unsuccessful to drop out the conversation as well. It is proven by the next turn from Donkey which still keeps the conversation going for more turns.

Both turns (384) and (392) show that in fact Shrek does not want to have any further conversation or in other words, Shrek does not want to cooperate with Donkey in exchanging information. His refusal to cooperate is generated in a form of his attempt to step out from the conversation. Moreover, these turns (384) and (392) also show that Shrek cannot reply the way that is expected by Donkey, that is the explanation upon what Shrek hides. Because of these reasons, Shrek is considered as opting out of the conversation no matter the fact which shows that all of his attempts fail.

5. The violation of maxim of quantity and maxim of manner 07/352-355/MQn-MMn/CT

Turn Participants Dialogs

348 Donkey Okay, so here's another question. Say there's a woman that digs you, right, but you don't really like her that way. How do you let her down real easy so her feelings aren't hurt, but you don't get burned to a crisp and eaten?

349 Fiona You just tell her she's not your true love. Everyone knows what happens when you find your...(Shrek drops her on the ground) Hey! The sooner we get to DuLoc the better.

350 Donkey You're gonna love it there, Princess. It's beautiful!

351 Fiona And what of my groom-to-be? Lord Farquaad? What's he like?

353 Donkey I don't know. There are those who think little of him. (they laugh again)

354 Fiona Stop it. Stop it, both of you. You're just jealous you can never measure up to a great ruler like Lord Farquaad.

355 Shrek Yeah, well, maybe you're right, Princess. But I'll let you do the "measuring" when you see him tomorrow.

The conversation above occurs after Fiona acknowledging that the prince willing to save her is Lord Farquaad that is put Shrek and Donkey in a quest to rescue Fiona from the dragon. Since it is not Farquaad himself rescuing Fiona, consequently she has never seen him and so she asks Donkey of how Farquaad looks like (in turn (351)). In turn (352), Shrek interrupts their chat and remarks that ‘men of Farquaad’s stature are in short supply’ (Shrek, 2001) which is followed by Shrek’s and Donkey’s laughter. This remark, then, is commented by Donkey in turn (353) by the marker like ‘I don’t know’ and adds some more information that: ‘there are those who think little of him’ and is followed by another laughter from Shrek and Donkey.

The word short in short supply means, first, that there is not many people are like Farquaad, and second, that Farquaad is not existing in large enough quantities to satisfy demand (as a prince charming) (Hornby, 1995: 1090), and third, that Farquaad is less than the average or required height (Hornby, 1995: 1089). Meanwhile the word little in ‘think little of him’ means first, little in a sense that Farquaad is not big or small or small when compared with others (Hornby, 1995: 688) and second, little also means an indefinite pronoun which in ‘think a little of him’ can be inferred that there are only ‘a small amount’ (Hornby, 1995: 668) of people thinking of him. All of the meanings in those two words basically point on Farquaad’s posture which is small.

By using these multiple meaning words, Shrek and Donkey are ambiguous in describing Farquaad and because of their manner of excluding Fiona to be the third party (when they laugh together), Shrek and Donkey are regarded as violating the maxim of manner. Moreover, they are also regarded as violating the maxim of quantity since they do not give Fiona sufficient information about how Farquaad looks like as what is needed by Fiona.

6. The violation of maxim of Quality and maxim of Manner 10/497/MQl-MMn/CT

Turn Participants Dialogs

488 Shrek There it is, Princess. Your future awaits you.

489 Fiona That's DuLoc?

490 Donkey Yeah, I know. You know, Shrek thinks Lord Farquaad's compensating for something, which I think means he has a really...(Shrek steps on his hoof) Ow! 491 Shrek Um, I, uh- - I guess we better move on.

495 Donkey What are you talking about? I'm fine. 496 Fiona (kneels to look him in the eyes) That's what

they always say, and then next thing you know, you're on your back. (pause) Dead. 497 Shrek You know, she's right. You look awful.

Do you want to sit down?

identified as a violation of the maxim of quality since she gives Donkey the information that she believes to be untrue.

As it is noted before, in this time Shrek and Fiona begin to get attracted to each other. It seems that both of them want to delay their arrival to DuLoc in order to have more time to spend together. To attain this goal, Shrek needs Donkey to believe that what Fiona has said is true. Shrek’s effort to assure Donkey is by justifying Fiona’s opinion, that first, Donkey is not in a good condition, and second, that people usually think that they are okay before they die, like what Donkey think. Shrek’s justification, however, indirectly makes him violating the maxim of quality since he gives the information that he believes to be false.

In his turn (497): ‘You know, she’s right’, Shrek tells Donkey that what Fiona has said, which in fact is not true, is right. By ‘supporting’ Fiona’s statement in turn (494) that Donkey does not look good, Shrek is therefore telling untrue information. Considering that Shrek intentionally gives the information to mislead Donkey so that he will believe that he is not in a good condition, Shrek, therefore, is regarded as violating the maxim of quality.

their first encounter. This judgement appears in some of the previous dialog such as in turn (58): ‘Stop singing! It's no wonder you don't have any friends.’, which shows Shrek’s dislike toward Donkey.

In the mean time Shrek chooses to use this word, he can freely express his dislike to Donkey by stating that he is ‘awful’ and opens an access for Donkey to infer that he really is in a bad condition. This inference is possible to arise since Shrek’s next utterance is an offering to Donkey to have a rest (‘Do you want to sit down?’). Because of his attitude of becoming ambiguous, Shrek is considered as violating the maxim of manner. His violation of the maxim of manner is seen in the fact that in this dialog it is only Fiona and Shrek who seem to understand what the real meaning of Shrek’s first assessment (that Fiona is right) which attitude makes Donkey seen to be excluded as the third party in the conversation. Because Shrek intentionally gives ambiguous statement and shares the ‘true information’ only with Fiona, Shrek is regarded as violating the maxim of manner.

B. The analysis of possible reasons the participants violate the maxims

1. To control the other participants’ feeling by creating fear

This reason is carried in the dialog 01/6-8/MQn/CF when Shrek frightens the men who try to capture him. In this scene, there are three men sneaking in the bush and spying Shrek’s cottage. During their spy, these men are involved in a conversation about what ogres can do to harm people. In the conversation, Man 3 tells the others about what kind of threat ogres can do in turn (5): ‘Yeah, it’ll grind your bones for it’s bread’.

In the next turn, Shrek suddenly inserts himself in the conversation and gives a correction to Man 3 that what he explains to his friends are the harmful thing which is usually done by giants. Shrek’s existence within the men of course is one point which makes them afraid since Shrek himself is an ogre which people are afraid of. This fear, moreover, is added by some of Shrek’s opinions which are constituted in turns (6) and (8) and will be explained as follow.

As what has been discussed in the previous analysis, in this dialog Shrek fails to observe the conversational maxim and is regarded as violating the maxim of quantity. He violates the maxim of quantity since he gives too much information than is needed (by the men) which is constituted in his personal opinion upon what ogres can do to the men. His personal opinions eventually are used to add the men’s fear so that they will not try to catch and bother Shrek.

the men. This opinion then is followed by the ‘worse thing’ that has been said before that ogres will make a suit from the men’s freshly peeled skin.

In his next turn (8), Shrek does the same thing with his previous turn. He adds his own personal opinion upon his previous correction that the jelly of the men’s eyes is quite good on toast as in ‘They’ll shave your liver. Squeeze the jelly from your eyes! Actually, it’s quite good on toast’. Yet again a point to be considered, this opinion comes from Shrek who is an ogre. Meaning to say that by being an ogre and utters such opinion, Shrek seems to strengthen the point that ogres are indeed frightening and even worse than giants as what he has stated in turn (6).

Giving these kind of opinions, Shrek apparently wants to make the men stop chasing after him and leave him alone. In addition, Shrek does not like to live with other people and rather to choose to enjoy his life alone in his swamp. This is seen in many of the scenes in the film, such as in the beginning of the film showing that Shrek is so happy in his swamp alone and his own statement that he loves his privacy (Shrek, 2001). He chooses to be alone since he is oftenly misjudged by the people as a horrible creature before they know who Shrek really is.

2. To plead the other participants