Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2981858

Effects of an Information Sharing

System on Employee Creativity,

Engagement, and Performance

Shelley Xin Li

Tatiana Sandino

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2981858 Working Paper 17-094

Copyright © 2017 by Shelley Xin Li and Tatiana Sandino

Working papers are in draft form. This working paper is distributed for purposes of comment and discussion only. It may not be reproduced without permission of the copyright holder. Copies of working papers are available from the author.

Effects of an Information Sharing

System on Employee Creativity,

Engagement, and Performance

Shelley Xin Li

University of Southern California

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=2981858

1 Effects of an Information Sharing System on

Employee Creativity, Engagement, and Performance

Shelley Xin Li

Leventhal School of Accounting

University of Southern California, Los Angeles, CA 90089

Tatiana Sandino* Harvard Business School

Harvard University, Boston, MA 02163

May 1, 2017

Abstract

Many service organizations empower frontline employees to experiment with different ways to meet diverse customer needs across different locations. We conducted a field experiment in a retail chain to test the effects of an information sharing system recording employees’ creative work— a control system often used to promote local experimentation—on the quality of creative work, job engagement, and financial performance. While, on average, the mere introduction of the information sharing system did not have a statistically significant effect on any of these outcomes, we find that the system had a significantly positive effect on the quality of creative work when it was more frequently accessed. It also had a positive effect on the quality of creative work in stores with fewer same-company nearby stores (i.e., with less natural exposure to peers’ creative work) and on the value of creative work and the attendance of salespeople working for stores in divergent markets where customers had distinctive needs requiring customized service. We also find weak evidence that the system led to better financial results when salespeople had lower rather than higher creative talent prior to introducing the system. The findings of our study shed light on when information sharing systems can affect the quality and performance consequences of employees’ creative work.

* Corresponding author’s contact information:

Morgan Hall 367, Harvard Business School, Boston MA 02163 E-mail: [email protected]

Phone: (617) 495-0625

2 1. Introduction

Service and retail organizations in diverse markets often need to find ways to understand and

satisfy customer needs on a timely basis. To do so, these organizations tend to allocate greater

decision authority to their frontline employees, who have better access to relevant local

information than headquarters, so that they can gather information about customer needs and

generate creative and timely solutions to fulfill those needs (Baiman, Larcker, and Rajan [1995],

Fladmoe-Lindquist and Jacque [1995], Aghion and Tirole [1997], Dessein [2002], Campbell,

Datar, and Sandino [2009]). However, despite the perceived value in employees’ local creativity

and the formally granted permission to experiment, not all employees use discretion to generate

creative ideas or solutions (Campbell [2012]). Prior studies in economics, accounting, and

management have examined several control systems that facilitate or inhibit such local creative

experimentation. Collectively, these studies highlight the importance of providing long-term

incentives, tolerating short-term failures, and selecting the “right” type of employees

(Holthausen, Larcker, and Sloan [1995], Campbell [2012], Manso [2012]). However, these

studies have mostly overlooked the role information sharing plays in ongoing local

experimentation and, more specifically, in employees’ creative efforts.

In this study, we exogenously increased access to information on peers’ creative work through a

field experiment that introduced an information sharing system recording employees’ creative

work (hereafter ISSC). Our goal was to examine the impact of introducing an ISSC on the

quality of creative work, job engagement, and financial performance.1

1 For the purposes of this study, we assess the quality of creative work based on Hennessey and Amabile’s [2009] definition of what

3 There are various economic and behavioral forces that make it unclear whether an ISSC will, in

practice, promote experimentation and yield positive performance outcomes. This kind of system

could yield significant benefits by (a) providing employees with greater access to information,

enhancing their creative abilities through a broader and more diverse pool of ideas than their

initial set and/or (b) affecting the employees’ motivation and engagement by increasing

accountability for the quality of their creative work.

Yet, the system could also impose significant costs if it unintentionally leads employees to

reduce their experimentation by conforming to a common, unimaginative norm. Employees

could do so to minimize risk (if they fear that novel work would be judged negatively by their

peers), if they free-ride on their peers by copying their creative work, or if they felt threatened

that their peers would free-ride on their own creative work (Arrow [1962]).

We partnered with a mobile phone retail company (hereafter MPR) differentiating on customer

service and operating 42 company-owned stores to develop a field experiment testing the effects

of implementing an ISSC. Like many other customer-focused retailers, idea generation based on

the local environment is an integral part of the work at MPR’s stores. MPR operates in an

emerging market where customization of the sales process is essential to compete with local

mom and pop shops. The salespeople at the retail stores create hand-made sales posters to attract

local customers’ attention and to explain the store’s promotion plans, which are updated by the

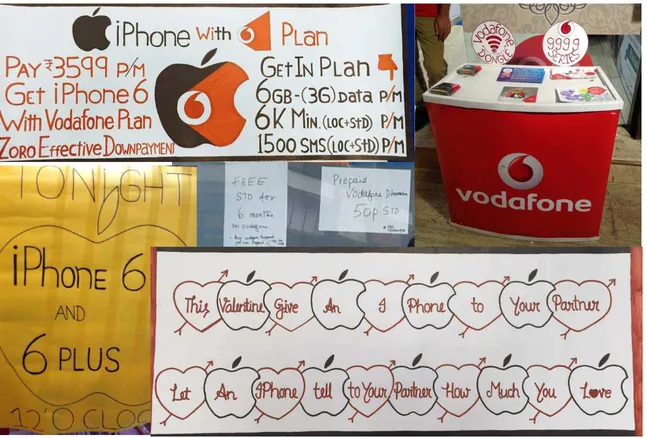

retailer and/or its suppliers on a weekly basis. Figure 1 presents examples of the posters

salespeople create and display at their stores.2

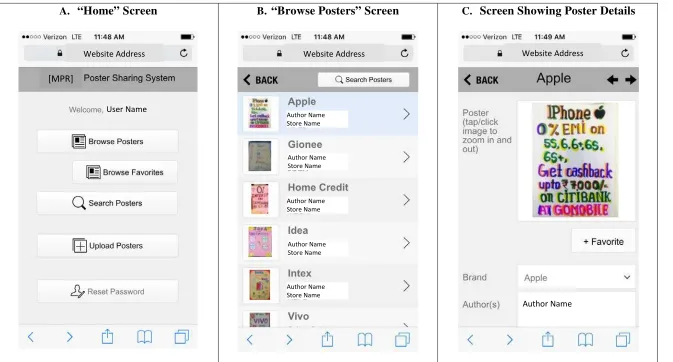

4 MPR collaborated with us on a field experiment in which the company pilot-tested an ISSC (a

web app) showcasing the sales posters developed by the salespeople at the treated stores (i.e., the

stores where the system was tested). The site was accessible via mobile phone by the store

managers and the salespeople working at the treated stores, who could both upload posters and

browse other people’s posters by brand or by favorites.3 Although the salespeople produced these

posters on an ongoing basis, prior to this experiment, the sales posters had never been shared

across stores. In the field experiment, we randomly assigned stores to a “treatment” group, where

we introduced the ISSC, and to a “control” group.

We examined the effects of the ISSC on three outcomes of interest: quality of creative work, job

engagement, and financial performance. Following prior creativity studies (e.g. Amabile [1988]),

we measured the first outcome based on two dimensions: the value of the creative work

(measured on a 1-5 scale capturing the poster’s ability to communicate the products and deals

offered) and the novelty of the creative work (measured on a 1-5 scale, capturing the posters’

ability to distinctively grab the attention of customers). We used the brand promoter’s weekly

attendance as a proxy for job engagement, and the store-brand weekly sales to measure financial

performance. Our findings suggest that, on average, the ISSC did not have a statistically

significant impact on any of these outcomes.4 However, further tests uncover circumstances

where the system was associated with a number of favorable outcomes. Our analyses show that

the ISSC had a positive effect on the quality of creative work (and to a more limited extent, the

stores’ financial performance and attendance) when it was more frequently accessed, even after

3 In the field experiment, the exposure of the posters on the website was mandatory. Store managers and managers at the headquarters followed up with all the salespeople in the treatment stores during the monthly “uploading” period to make sure that every salesperson’s poster was in the system.

4 Based on our power analyses, we are 80% confident that, on average, the ISSC did not change the quality of creative work

5 controlling for the types of stores more prone to accessing the system. In stores where the system

was used most often, the effect of the system was associated with an increase in the value

(novelty) of creative work of 0.40 (0.23) points on a 1-5 point scale.

We also explore three conditions that could have affected the impact of the ISSC: the users’

natural exposure to others’ ideas, the ex-ante creative talent of the individuals, and the type of

market served (mainstream vs. divergent). On the first condition, we find that the ISSC was

associated with greater quality of creative work in stores with fewer same-company nearby

stores (i.e., an increase of 0.38 points in the value of creative work on a 1- 5 point scale and 0.29

points in the novelty of creative work on a 1 - 5 point scale). This suggests that the system was

more beneficial where salespeople were naturally less exposed to others’ creative work.

Interestingly, the system was also associated with a 0.30 decrease in the novelty of creative work

on a 1-5 scale in stores with more same-company nearby stores, suggesting that salespeople at

those stores may have been more concerned about their peers’ free-riding. On the second

condition, we find that the system led to better financial results when salespeople had lower

creative talent than when they had higher creative talent prior to introducing the system. A 25%

increase in sales following the adoption of the ISSC was observed for store-brands with

promoters whose ex-ante creativity was below the median, suggesting that they may have had

more to learn from others’ work. Finally, on the third condition we find that the ISSC was

associated with a 0.28 point increase in the value of creative work on a 1-5 scale and a 0.24 days

6

markets,5 consistent with the idea that stores requiring greater customization could benefit more

from the system.

In summary, although the introduction of the ISSC at our site did not strongly lead to significant

improvement in average outcomes, the system was associated with improvement in the quality of

creative output when accessed frequently and/or where information was most needed (i.e., where

the salespeople were less exposed to others’ ideas or where they needed to tailor their efforts to

specific customers’ needs). Furthermore, the system was associated with increases in financial

performance for store-brands whose promoters were initially less creative and to greater job

engagement in divergent markets where customers demanded greater customization.

Our study contributes to two streams of literature. First, we contribute to the accounting literature

that examines the effects of management control systems on the quality and performance

consequences of employees’ creative work. This literature has largely focused on examining the

extent to which executive and employee incentive pay can enhance creativity and innovation. For

instance, Holthausen, Larcker, and Sloan [1995] find modest evidence that business units where

executive pay was tied to long-term performance were linked to greater future innovation. Prior

laboratory experiments rewarding subjects for either the quantity or the creativity-weighted

quantity of their creative output show that the former type of rewards leads to greater

creativity-weighted productivity than the latter (Kachelmeier, Reichert, and Williamson [2008],

Kachelmeier and Williamson [2010]). In a similar experiment, Chen, Williamson, and Zhou

[2012] find that, when rewarding individuals for the creativity of their output, group-based

5 The manager identified as “divergent stores” those where the salespeople had to customize the service more due to distinctive

7 tournament incentives are more effective at promoting group creativity than both

individual-based tournament incentives and group-individual-based piece-rate incentives. In contrast with the focus on

incentive systems in these prior studies, our study, to the best of our knowledge, is the first to

focus on a management control system that gives employees access to information—specifically,

an ISSC—that could not only affect the employees’ motivation to be creative and engage more

closely with their jobs but also enhance the knowledge and skills needed to be creative in their

work. Our study finds that these positive effects materialize only when users engage with the

system, and/or when users have greater potential to learn from the information in the system

given either their lack of creativity or exposure to others’ creative work (limited supply of ideas)

and/or their need to customize their creative work (greater demand for ideas).

Second, this study contributes to the literature in accounting and management that studies the

effect of increased access to information on decision outcomes and new knowledge creation.

Prior studies in accounting have found that the implementation of information sharing systems in

organizations is associated with improvements in decision quality and financial performance

(Banker, Chang, and Kao [2002], Campbell, Erkens, and Loumioti [2014]). Moreover,

organizational knowledge creation theory suggests that interactions among diverse practitioners

lead to innovation (Nonaka [1994], Nonaka and Krough [2009]). In two laboratory experiments,

Dennis and Valacich [1993] and Girotra, Terwisch, and Ulrich [2010] apply this theory to test

the effects of information sharing systems on brainstorming sessions. Their findings reveal that,

by enabling subjects to work individually before exposing their ideas to others in brainstorming

sessions, the use of information sharing systems contributes to increasing the number and quality

of ideas generated as well as the participants’ satisfaction with the group ideation process. To our

8

work of individuals as well as their resulting job engagement and performance. And it is also the

first to examine these effects on individuals as they perform day-to-day creative tasks in the

context of their organizations. Our results suggest that an ISSC can affect creativity and

engagement (a) when users engage with the systems on a regular basis, a requirement that may

be harder to attain when individuals are performing their daily jobs than when, as in prior

experiments, they are explicitly asked to use a system to complete a task, and/or (b) when

individuals have greater need to learn about and implement creative ideas.

Beyond contributing to the academic literature, our study aims to shed light on a topic that has

gained significant attention from the business community in recent years, with companies

increasingly seeking ways to leverage the use of information networks within their firms to

increase employee interactions and exchanges of ideas.

The rest of this proposal is organized as follows. Section 2 presents our hypothesis development,

Section 3 describes our research method and setting, Section 4 provides a detailed description of

our research design, presents our analyses, and discusses our findings. Section 5 concludes.

2. Related Literature and Hypothesis Development

Prior research on service organizations has found that many so-called empowered frontline

employees fail to use their discretion to creatively meet the needs of local customers (Campbell

[2012]). An emerging literature in finance and accounting has identified management control

mechanisms that organizations could effectively use to motivate local experimentation among

employees, including long-term incentives, tolerance for early failures, and the recruitment of

9 [2012]). However, to our knowledge, this literature has ignored an important control mechanism,

ISSCs, which has been extensively employed in practice with the intent to promote creativity.6

While prior studies have shown that information sharing systems could benefit organizations

(e.g., Kulp [2002], Kulp, Lee, and Ofek [2004], Devaraj, Krajewski, and Wei [2007], Campbell,

Erkens and Loumioti [2014]), they have focused on benefits related to improvements in

coordination and decision making rather than on improvements in local creativity and

experimentation. Examining the effects that such information sharing systems could have on

creativity and the performance outcomes of creative efforts is relevant, since these effects are

unclear. On the one hand, organizational knowledge creation theory suggests that sharing ideas

enhances creativity (Nonaka [1994], Nonaka and Krough [2009]). In addition to the effect on

creative work itself, prior research suggests that the encouragement of individual creative

activities can lead to greater task engagement and learning (Conti, Amabile, and Pollack [1995]).

On the other hand, economics scholars suggest that the sharing of creative ideas can lead to free

riding and reduce the production of new ideas (Arrow [1962], Dyer and Nobeoka [2000]). To the

extent that free riding diminishes employee investment in thinking about how to do their work

more effectively and/or crowds out some of the best creative ideas across the organization, the

implementation of an ISSC could result in an overall decrease in creativity and value.

Our main objective is to examine whether an ISSC ultimately leads to better financial

performance. However, we first develop hypotheses on the intermediate outcomes that can affect

6According to a survey conducted by McKinsey Global Institute [2012, p.12], approximately 70% of companies use information

10 financial performance (i.e., quality of creative work and employee engagement) before we state

hypotheses on the financial results.

2.1. Effect on the Quality of Creative Work

Traditional monitoring and incentive systems can be useful means of setting expectations and

evaluating employees in tasks and goals that can be explicitly stated. However, customer-focused

service organizations that require employees to apply discretion and creativity to do their job are

often unable to specify in advance all the tasks and processes employees should follow and the

goals they should attain to engage and serve customers effectively (Banker et al. [1996]). Much

of the information on which empowered employees make decisions is idiosyncratic (Campbell,

Erkens, and Loumioti [2014]). To be effective, empowered employees need to rely on tacit

knowledge, which is know-how that is difficult to transmit through explicit means and which can

only be obtained through engaging in practical activities, interacting with mentors, and observing

how experienced colleagues incorporate idiosyncratic information on a regular basis into their

decisions and actions (Polanyi [1966], Tsoukas [2003]).

For two reasons, ISSCs have the potential to overcome some of the limitations that traditional

management control systems have in guiding and motivating empowered employees to use their

local expertise to experiment with new ways to conduct their job. First, ISSCs can expose

employees to a broader and more diverse pool of ideas from their peers, helping them acquire

tacit knowledge or domain-relevant skills that could enhance their jobs. Organizational

knowledge creation theory states that employees who are exposed to other people’s ideas are

encouraged to reflect on their own practices and are more likely to discover new ways to do their

11 Nonaka and Krough [2009, p.645], “by bringing together different biographies, practitioners gain

‘fresh’ ideas, insights, and experiences that allow them to reflect on events and situations.…

Practitioners’ diverse tacit knowledge, that they particularly acquired in their diverse social

practices, is a source of creativity.” Consistent with this theory, Chen, Williamson, and Zhou

[2012] find that tournament rewards for creativity are more likely to result in creative solutions

when awarded to teams rather than to individuals. The organizational knowledge creation

literature also suggests that the process by which ideas are shared in electronic ISSCs enhances

creativity more effectively than the process by which individuals usually share ideas in

face-to-face meetings. This is because electronic ISSCs enable individuals to work alone and share ideas

at different times, preventing the “production blocking” that occurs when individuals attempt to

simultaneously come up with ideas in face-to-face meetings where they need to take turns to

speak up (Dennis and Valacich [1993], Girotra, Terwiesch, and Ulrich [2010]).

Second, by exposing the employees’ creative work to their superiors and/or peers, ISSCs could

motivate employees to increase their efforts to produce high-quality creative work. The most

creative workers might feel motivated, knowing that their work could impact others and be

recognized within the organization, while the least creative workers might exert efforts to avoid

exposing work they might not feel proud of and the appearance of doing worse work than most

of their peers (since the work of all employees is exposed side by side).

Despite the arguments presented above, the implementation of ISSCs could backfire and lead to

a decrease in creativity. Individuals exposed to the creative work of others could converge on

doing work in similar ways and could decrease rather than increase the creativity of their work.

12 emulate common features of their peers’ creative work or from the employees’ decision to

neither pursue nor present their most original ideas for fear of being judged negatively (Diehl

and Stroebe [1987]). Furthermore, the exchange of creative ideas among a group of employees

could lead to free riding (Alchian and Demsetz [1972]). This can occur if individuals copy

others’ ideas in their work or decrease their efforts to produce high-quality work for fear of being

copied by their peers.

The conflicting arguments described above suggest that the introduction of an ISSC could lead to

either an increase or a decrease in the quality of creative work,7 as stated in the following

hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1a: The introduction of an information sharing system recording creative

work (ISSC) will lead to an increase in the quality of the employees’ creative work.

Hypothesis 1b: The introduction of an information sharing system recording creative

work (ISSC) will lead to a decrease in the quality of the employees’ creative work.

2.2. Effect on Employee Engagement

Prior research suggests that two key antecedents of employee engagement (i.e., investment of an

individual’s complete self into his/her work) are the individual’s sense that his/her work is

meaningful and valuable and the sense that he/she is capable of performing this work (Kahn

[1990], Rich, Lepine, and Crawford [2010]). ISSCs have the potential to enhance a worker’s

13 sense of value by increasing the outreach of the worker’s creative work, the expected impact this

work could have on others, and the worker’s potential to be recognized by superiors and peers.

These non-pecuniary benefits could increase employees’ overall level of effort in conducting

their creative work. These systems also have the potential to develop an individual’s abilities and

confidence in those abilities to produce creative work. Furthermore, creative activities tend to

require a more active and extensive search for information. An ISSC that could stimulate greater

participation in creative activities could increase employee efforts in information acquisition and

processing, regardless of the quality of their creative work.

However, ISSCs could unintentionally increase individuals’ fears of being singled out, evaluated,

and embarrassed in front of their peers, leading to an overall loss of confidence (Diehl and

Stroebe [1987], Toubia [2006]). Free riding could also lead individuals to withdraw from

investing in producing high-quality creative work, resulting in a decrease in the value of their

work. These two unintended effects would most likely reduce employee engagement. Given the

unclear effect that ISSC would have on engagement, we split our second hypothesis as follows.

Hypothesis 2a: The introduction of an information sharing system recording creative

work (ISSC) will lead to an increase in employee engagement.

Hypothesis 2b: The introduction of an information sharing system recording creative

work (ISSC) will lead to a decrease in employee engagement.

2.3. Effect on Financial Performance

Customer-focused service organizations that are able to unleash the creativity of their employees

and increase employee engagement in the workplace should expect to achieve greater results.

14 work can be expected to have greater mastery of the brands and deals offered at their stores.

Consequently, they should be better able to communicate these offerings to their customers and

relate them to their customers’ needs even if the quality of their creative work may not improve

significantly (i.e., there could be benefits in the act of creating, regardless of the outcome). Prior

studies on employee engagement demonstrate that employees who are highly engaged in their

work exhibit greater task performance, since they not only exert greater physical effort but also

focus their cognitive and emotional energies on achieving work-related goals (Kahn [1990],

Rich, Lepine, and Crawford [2010]). These arguments suggest that the direction in which the

implementation of an ISSC will affect financial performance will be contingent on the effect of

the system on the quality of creative work and employee engagement. Following the predictions

above, we state our third hypothesis as follows.

Hypothesis 3a: The introduction of an information sharing system recording creative

work (ISSC) will lead to an increase in financial performance.

Hypothesis 3b: The introduction of an information sharing system recording creative

work (ISSC) will lead to a decrease in financial performance.

3. Research Method and Setting

We test our hypotheses by running a field experiment in a mobile phone retail chain (MPR) in

India that operated 42 company-owned stores as of September 1, 2016. On that date, the

company introduced a pilot project in a random group of stores to test the effects of an ISSC.

The system consisted of a web app that displayed sales posters generated by salespeople across

different stores operating across different markets. The managing director of the company

15 experiment, where the stores adopted the system as part of their regular work and the store

teams did not know that they were part of an experiment (Floyd and List, 2016).

This method has several advantages. First, a natural field experiment allows us to test the

impact of an intervention on a randomly selected group of participants who are doing the types

of tasks they naturally perform in their working environment and who possess all the tacit

knowledge needed to perform those tasks. This point is particularly relevant, since some of the

reasons why ISSCs may work (e.g., employees exerting greater efforts to avoid exposing

low-quality work) or may not work (e.g., employees’ free riding on their peers’ work) may be more

relevant in natural settings where individuals have been engaged with their work and their

peers over a long period than in laboratory settings. Second, the natural field experiment

method we employ also allows us to avoid the selection problem that arises when subjects

choose whether to participate in an experiment. In our study, participants were automatically

enrolled in the experiment because the implementation of the ISSC was a pilot program that

they were unable to opt out of. Finally, apart from avoiding this selection bias, a natural field

experiment can mitigate concerns related to the Hawthorne effect (the effect of employees

reacting to being observed rather than reacting to the treatment itself).

MPR operates in a highly dynamic and locally idiosyncratic competitive environment. Its

primary competitors are small independent sellers of handsets and connection services who,

through their intimate knowledge of the local setting, are able to quickly respond to customer

needs and changes in customer preferences. The second most relevant set of competitors is

online retailers who often offer lower prices. To compete with these two sets of competitors,

MPR positions itself as a retailer that offers more value to customers. This is reflected by its

16 for the prices offered; its extensive assortment of products and services to better match customer

needs; and its trustworthy, high-quality customer service. It is essential to MPR’s business

strategy and commercial success that salespeople at the store level can effectively convey the

value of product or service offerings to local customers.

The MPR stores are staffed by a manager, a cashier, and multiple promoters representing various

brands (connection providers, insurance providers, credit providers, and handset manufacturers).

The managers and cashiers are employed directly by MPR and are tasked with efficiently

managing and operating the stores. However, most of the salespeople who interact with

customers and generate sales at each store are so-called brand promoters. Each promoter is hired

by, and receives compensation from, the MPR supplier whose brand s/he represents. A

promoter’s pay typically includes a salary component and/or a sales commission component.

MPR occasionally offers promoters incentives for strong sales performance as well as career

opportunities to become cashiers or store managers.8 None of the explicit incentives promoters

receive are related to the quality of their posters or of any other creative work they produce.

Both the MPR and MPR’s suppliers offer customers attractive packages for their products and

services, including bundles of handsets and connections, accessories, different credit options, and

promotional rewards (hereafter promotion deals). Promoters have significant discretion to

advertise these promotion deals by making their own sales posters to match the needs of their

local customers and displaying them in their stores.

8 The performance-based incentive structure at this setting is typical for the retail industry where frontline employees interact with

17 In a competitive market such as the mobile phone retailing industry in India, promotion deals are

updated weekly. Successful sales posters clearly communicate the essence of the latest deals

through a creative visual design that grabs people’s attention and attracts foot traffic into the

store. Even after customers are drawn into the store, promoters often explain the offering and

make a sales pitch by referring to the posters (see Figure 1 for a sample of the posters designed

by promoters).

The process of coming up with posters requires both a deep understanding of the local customer

base (e.g., what deals and what features in the deals would be most appreciated by the customers

in a specific region and what language is required to connect with them) and a great deal of

creativity (e.g., presenting the important features of the deals in a clear and visually appealing

way). The company realized that motivating promoters to generate more creative posters that

attract local customers is a very important part of achieving commercial success in this market.

However, although most if not all promoters come up with some form of posters as a part of their

sales effort, only a handful of them have consistently generated appealing sales posters that stand

out. Many promoters exert little effort or lack the skills to come up with more creative visual

designs (Figure 1).

To engage more promoters in the process of generating creative posters and to increase the

overall quality and effectiveness of these posters, the company implemented its ISSC.

This setting provides us with a valuable opportunity to test our hypotheses. First, it exemplifies a

typical setting in which ISSCs have the potential to add significant value: retail chains that

differentiate on customer service and which rely on the empowerment and creativity of their

18 interact with local customers and possess deep and real-time knowledge of their preferences and

needs. This knowledge is highly relevant input to producing creative work that aims to generate

sales from local customers. Second, creative output in the natural work environment is generally

difficult to measure. Sales posters developed at the store level enable us to reasonably measure

the quality of creative work, identifying the two main aspects that the literature highlights

regarding the quality of creative work: their value and their novelty (Hennessey and Amabile

[2009]). Furthermore, sales posters are a natural part of the frontline salespeople’s work at this

company and have a direct link to attracting local foot traffic and generating sales. Our findings

are generalizable to service organization settings in which frontline employees’ participation in

creative outputs is valuable and an important driver of financial performance and where such

employees have implicit or explicit incentives linked to financial performance.

4. Research Design, Analyses, and Results

4.1. Description and Timeline of the Experiment

4.1.1. General Description of the Experiment

We planned our study as an eight-month field research experiment from May 1, 2016 to

December 31, 2016. We extended the end of the experiment to January 31, 2017 due to an

exogenous economic shock in India significantly affecting the retail sector and, in particular, our

research site in the month of November.9Our main analyses include data from the month of

January 2017 and exclude data from the month of November 2016, maintaining the same number

9 During our experiment (in the post-intervention period), on November 8, 2016, the Indian government announced the demonetization of Rs.

19 of months that we originally planned to include in the pre- and post-experimental periods and

minimizing the impact of the economic shock on our analyses.

The participants in this experiment were all the brand promoters at MPR. As of September 1,

2016, 36 of the 42 stores had at least one brand promoter per store. On average, these 36 stores

had six brands with promoters per store and six promoters per store (the company generally

assigns a single promoter for a given brand to each store but sometimes—in less than 10% of the

cases— has two or more promoters of the same brand in the same store). We randomly assigned

the 36 stores into two groups: treatment group A (18 stores, 105 brands, and 106 promoters as of

September 1, 2016) and control group B (18 stores, 100 brands, and 104 promoters as of

September 1, 2016).10

Our analyses test the effects of MPR’s ISSC at the treatment stores relative to the control group

on three outcomes at the store–brand level: the quality of creative work, job engagement, and

financial performance. We measure these outcomes using weekly data from archival sources

(i.e., MPR’s accounting and personnel databases) and evaluations of the creative work by

customer panel participants, and validate these measures using survey data from pre- and

post-experimental surveys.

4.1.2 Timeline of the Field Experiment

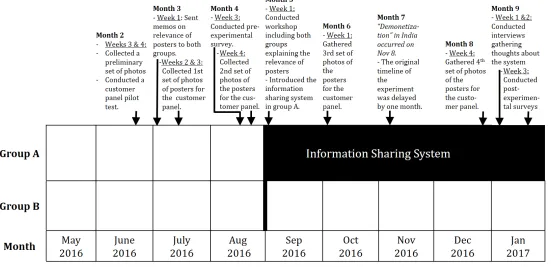

Figure 2 shows the timeline of the field experiment. We explain this timeline by describing the

events related to (a) the pre-intervention period, (b) the intervention, (c) the post-intervention

period, and (d) the ongoing implementation of the ISSC.

10 In a few cases, store proximity could lead employees in the “control” stores to learn that an information sharing system was implemented in

20

Pre-intervention period. The first four months comprised the pre-intervention period. In June of

2016 (month 2), we tested some of the data collection methods that would be employed during

the experiment.11 The company’s managing director then sent out a memorandum to store

managers (“team leaders” as they are referred to in the company) and promoters in July of 2016

under both experimental conditions. The memorandum described the relevance of sales posters

to the brands’ sales, explained what a high-quality poster is, and let the salespeople know about

company resources they were able to use to prepare their posters. The director also asked store

managers to highlight the relevance of the sales posters to their store staff. The purpose of

sending the memorandum to both the treatment and control groups before our poster data

collection during the pre-intervention period was twofold: (1) to make sure the promoters and

store managers were aware of the importance of sales posters and what good posters should look

like and (2) to hold the information about the importance of these posters constant across both

experimental conditions. Appendix 1 shows the content of this memorandum (month 3

memorandum). In addition to sending an initial memorandum during this period, we conducted a

pre-experimental survey to measure the promoters’ engagement, their store managers’

assessment of the quality of the creative posters, the extent to which the promoters were

motivated to produce creative work, and the extent to which they improved their skills to

produce creative work over the prior month. Whenever possible, we employed survey

21

instruments validated by prior research to design our questions.12 Appendix 2A presents the

questions included in this survey. Finally, the headquarters collected pictures of the posters

displayed across all the stores for the future customer panel evaluations in month 3 (July 2016),

and again in month 4 (August 2016), shortly before implementing the intervention.

Intervention. At the beginning of month 5 (September 2016), the managing director conducted

two workshops to increase the promoters’ awareness of the relevance of creating posters and to

introduce the treatment stores to the ISSC.13 The workshops were completed in two consecutive

days, the first workshop targeted control stores, and the second targeted treatment stores. During

the workshops, the director described what a high quality poster is (emphasizing that posters

should be useful and attractive), and invited the promoters to work on posters for 30 minutes as

they sat in tables organized by store, which had a stack of poster-making materials they could

use (colored cardboards, scissors, pencils, markers, tape, etc.). The director asked each store

team to select their favorite poster and then asked the authors of the posters to explain how they

came up with their posters. Both workshops were identical, except that the workshop for the

treatment stores also included an introduction to, and explanation of, the ISSC.14 While the

promoters and store managers of the treatment stores were working on their posters, two

facilitators helped the promoters and store managers get an account for, and access to, the ISSC

web app. To reinforce the messages communicated during the workshop, the managing director

12 The survey questions that aim to measure employee job engagement are from Rich et al. [2010]. The researchers (us) designed the self-assessment questions. Some of the self-assessment questions on the motivation to generate creative work are adapted from the survey questions on psychological empowerment from Zhang and Bartol [2010].

13 The managing director believed that the ISSC had to be introduced and described in a workshop. Otherwise, it would be ignored.

To avoid confounding the effect of the workshop with the effect of the ISSC, the authors of this paper asked the managing director to run workshops for both the control and treatment groups, differing only in the introduction of the ISSC.

14 One of the authors of the paper monitored the workshops in person to make sure that there were no technical difficulties

22 sent a memorandum to all stores. The memorandum reminded the store teams of the relevance of

producing high quality posters, and, in the case of the treatment stores, also reminded the store

staff about how to use the ISSC web app and the next steps they would need to follow to upload

their posters into the system. Appendix 1 shows the content of the memoranda sent in month 5

(September 2016) to the treatment and control stores.

Post-intervention period. We collected data to evaluate the effects of the intervention during this

period. We gathered photos of the posters displayed across all the stores at two times: shortly

after the implementation of the ISSC (in week 1 of month 6, i.e., the beginning of October 2016)

and toward the end of the sample period (in week 4 of month 8, i.e., the end of December

2016).15 In month 9 (January 2017), we also conducted a post-experimental survey that asked all

of the store managers to assess the promoters’ engagement, their motivation, and their ability to

produce posters. See post-experimental survey questions in Appendix 2A. To capture qualitative

insights and users’ impressions of the system, we also conducted 19 in-person interviews in

January at the stores, asking store managers and promoters of 8 treatment stores to discuss their

experience with the ISSC. See Appendix 2B for the interview questions.

Implementation of the information sharing system. As the memoranda distributed in month 5

explains (see Appendix 1), the ISSC consisted of a web app where the promoters from the

treatment group were able to see the sales posters created by other promoters and the stores

creating these posters. On the back end, the web app was administered by three head office

15This allows us to test the effects of the ISSC on financial performance, engagement, and quality of creative work, within one

23 employees, the managing director, the web developer, and the authors of this paper. The website

enabled the promoters to observe all the posters created in all stores in their mobile or desktop

devices, to pick their favorite posters, and to search the posters by brand, by store, or by favorites

(see screenshots of this website in Figure 3). If despite the mandate, a promoter did not submit a

poster, a blank space with an X and the words “No poster was created” appeared above the name

of the store-brand. The first set of pictures of sales posters were taken and uploaded into the

ISSC right after the system was introduced (in September 2016). From then on, store managers

and promoters at the treatment stores were required to post their pictures in the ISSC once a

month (the first week of month 6, and the fourth week of months 7 and 8).16 The store managers

and promoters of all the treated stores received an email following the uploading and approval of

the pictures every month to let them know the ISSC had been updated.

4.2. Data Collection and Measurement of the Main Variables of Interest

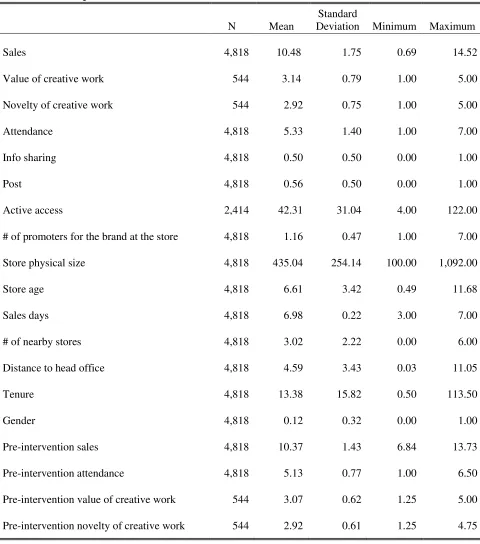

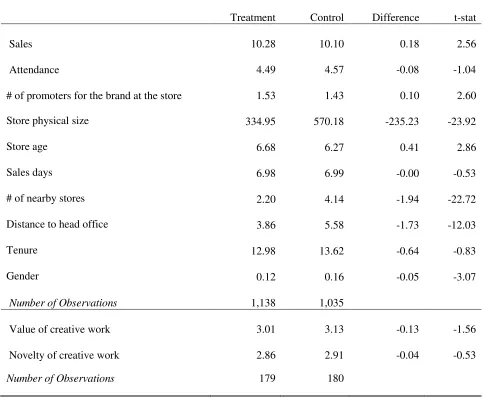

Table 1 Panel A provides descriptive statistics for our main variables of interest. We include

observations for which we have complete data to run our analyses: 4,818 store-brand-week

observations (including only weeks when a promoter of the brand attended the store) and 544

store-brand-month when posters were collected for customer panel evaluations (for our analyses

assessing the quality of creative work).

4.2.1. Main Outcome Variables.

We measure financial performance using store-brand sales data (largely attributed to the brand

promoters working at the store) from the company’s accounting system. “Sales” is defined as the

16 The original plan required the managers and promoters to upload new pictures on the first week of every month after the ISSC

24

natural logarithm of the store-brand weekly sales.17 We exclude cases where the weekly sales for

the store-brand are less or equal to zero.18 The average weekly brand-sales at a store during our

sample period were 10.48 (about Rs.36,000 or US$ 535), but varied considerably from 0.69 to

14.52 (i.e., from less than Rs.5 or just a few US cents, to Rs.2 million or US$ 30,418).

To assess the quality of the creative work (i.e., sales posters), we collected photos of all the

posters two times during the pre-intervention period and two times after the intervention, as

explained in Section 4.1.2. We recorded the dates of the posters, and presented them (without the

date) to a customer panel after collecting all the pictures of the posters and completing the

experiment. We collected a total of 683 unique posters during our experiment. Prior literature

recommends measuring creativity based on the value and the novelty of the work (Amabile

[1988], Sethi, Smith and Park [2001], Hennessey and Amabile [2009]). We obtained two

measures for the quality of creative work (adapted from Sethi, Smith and Park [2001]) from a

customer panel, where we asked the customer panelists to evaluate the value of the posters by

assessing their usefulness in communicating the products and deals offered, and the novelty of

the posters by assessing their visual attractiveness and ability to grab the attention of customers.

The customer panel was convened after the experiment and included customers of two income

groups that the company served (low and high). Each poster was evaluated by 8 customer

panelists: 2 customers per income group x 2 income groups (low and high) x 2 dimensions (value

and novelty). We created a software application that customers at the stores used to consistently

rate the posters in batches of 25 posters at a time. The batches were organized by brand and the

17 One of the 15 brands with promoters at the store provided credit services (Home Credit). Sales in this case are estimated as the

dollar amount of items purchased on credit.

25 selection of posters for each batch was generated randomly, including posters collected

throughout the pre- and post- intervention periods.19 This approach allowed us to hold constant

the evaluating circumstances and to make a fair comparison of the quality of creative posters

drawn at different times. Appendix 3 explains in detail what the customer panel did and presents

screenshots of the software application that the customer panel used to evaluate the posters.

The customer panel measures include a value rating indicating how effective the poster is at

communicating the products or deals offered using a not useful (1) – very useful (5) scale, and a

novelty rating indicating how much the poster’s visual design grabs the customer’s attention

using a not attractive (1) – very attractive (5) scale.20 The intra-class correlation coefficient for

the four ratings received by each poster on the value dimension is 0.3917, and for the 4 ratings

received by each poster on the novelty dimension is 0.3916 (both correlations are significantly

different from zero, with a p-value<0.01). The ratings of the posters of a store-brand collected on

the same month were averaged to obtain an average store-brand rating for each dimension for

each time period, resulting on the main measures for “Value of creative work” and “Novelty of

19 We decided to create batches per brand after noticing, during a pilot test, that some customers were sorting the posters based on brand

preferences. To solve this issue, we decided to include posters of the same brand in each batch.

20 The exact wording used to define these constructs appears in Appendix 3. The customers read the following definitions when

rating the posters at the stores based on either attractiveness or usefulness: Attractiveness:

• Very attractive posters are those that grab your attention the most. For example, you know that a poster is attractive if it prompts you to stop, read it, and walk into the store.

• Not attractive posters are those that grab your attention the least. For example, you know a poster is not attractive if it does not stand out.

Usefulness

• Very useful posters are those that most clearly communicate the products or the deals offered.

• Not useful posters are those that are least able to communicate the products or the deals offered.

26

creative work” used in our analyses.21 As Table 1 Panel A shows, the average value rating for the

posters of a store-brand was 3.14 and the average novelty rating for a store-brand was 2.92.

Our main measure capturing job engagement is “Attendance,” a weekly measure of brand

promoter attendance.22 We adjusted this measure to exclude cases when a new promoter did not

last more than a week at the company or when a promoter reported that s/he attended a store

different from his/her home store for 2 or less days in a month.23 The latter case is because

promoters occasionally visit other stores for a few hours for training purposes. Table 1 Panel A

reports that the promoters of a brand attended the store an average of 5.33 days a week, with

attendance ranging from 1 to 7 days a week. In addition, we constructed measures of employee

engagement through pre- and post-experimental surveys (see Appendix 2A). The survey

measures on job engagement are positively associated with Attendance, our proxy for

engagement (correlation=39.1%, significant at a 1% level).

4.2.2. Explanatory Variables

The main explanatory variables in our analyses are the variables “Info sharing” (identifying

treated stores) and “Post” (identifying the period after which the ISSC was introduced). A

similarly relevant variable is “Active access,” which measures the number of times the staff at

each store accessed the system to actively engage with it (e.g. upload or browse posters) in the

post period. Table 1 Panel A shows that, although the average frequency of access to the system

21 In addition to these measures, we asked the promoters’ store managers to rate the posters in pre- and post-experimental surveys

(see Appendix 2A for the questions included in the pre- and post-experimental surveys). The store managers’ assessment of the quality of the promoters’ creative work was positively associated with the customers’ assessment of the quality of the promoters’ posters, estimated based on the average of the value and novelty ratings of the posters (correlation=10%, significant at a 10% level).

27 was low, there was wide variation in the use of the system, with some stores only accessing it

minimally (4 times) while others accessing it much more often (up to 122 times).

We also collected data from company records and surveys to construct control variables related

to store and promoter characteristics. Store characteristics include the number of promoters for

each brand at the store, store physical size, store age, sales days (i.e., number of days in the week

when the store made sales), number of nearby stores from the same retail chain, and distance to

MPR’s head office. Promoter characteristics include tenure, gender, and pre-intervention

measures for sales/attendance/quality of creative work. Appendix 4 describes how the variables

were constructed. Table 1 Panel A shows significant variation across all these variables.

Table 1 Panel B compares the pre-intervention values of the main variables used in our analyses

between the treatment and control groups. There are no statistically significant differences in

pre-intervention attendance, value of creative work and novelty of creative work between the two

experimental conditions. There was greater pre-intervention sales for the treatment group.

Treatment and control groups also show different pre-intervention values in a number of

covariates despite the random assignment of treatment conditions. In our analyses, we control for

all these covariates as well as the pre-intervention average values of the outcome variables.

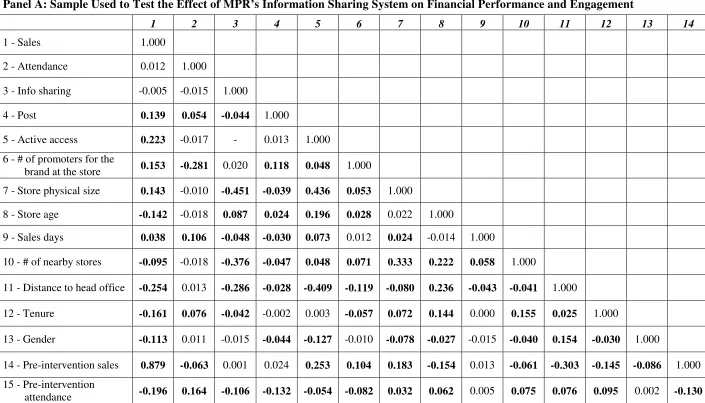

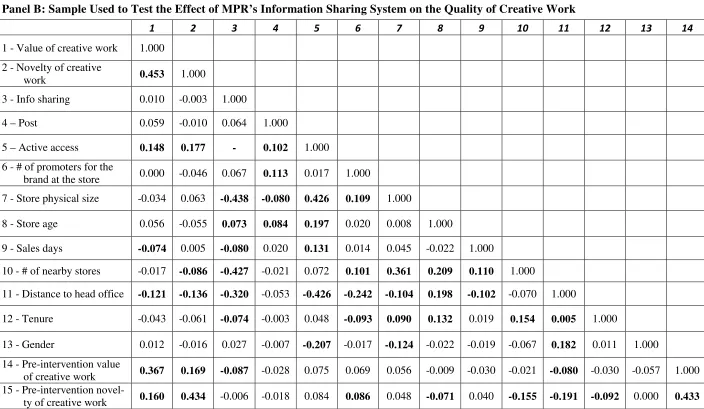

4.2.3. Correlation Tables.

Table 2 Panels A and B display two correlation tables corresponding to the two samples used to

assess the effect of MPR’s ISSC on weekly store-brand sales and store-brand promoter

attendance, and the effect of the system on the quality of creative posters. Table 2, Panel A

28 dummy variable for adopting the ISSC (Info sharing), but reports a general increase in sales and

attendance across treatment and control stores after the ISSC was introduced (Post).

Furthermore, the table shows a positive and significant correlation between the salespeople’s

access to the system and sales. Many control variables are significantly associated with Sales,

Attendance, or both measures, and in many instances are also associated with our Info sharing

and Active access variables, suggesting a multivariate analysis would yield more accurate

insights than the correlation table. Similarly, Table 2, Panel B does not show any association

between the proxies for the quality of creative work and Info Sharing, but it shows a significantly

positive association between the quality of creative work measures and salespeople’s access to

the ISSC. Several statistically significant correlations between the control measures and both, the

dependent variables and the ISSC variables (Info sharing and Active access), support the use of

multivariate analyses.24

4.3. Regression Analyses Testing Our Hypotheses

We test our hypotheses by estimating the following difference-in-differences regression model at

the store (i)–brand (j) level, using robust standard errors clustered by store:

Outcomeijt = β0 + β1 Info sharingi + β2 Info sharingi*Postit + β3 Postit

+ βn Controlsijt + Brand fixed effects+ εijt (1)

where Outcomeijt is measured using (a) the natural logarithm of sales for brand j at store i in

week t, (b) the quality of the creative work displayed at store i in month 3, 4, 6, or 8 (based on

24 Matching each poster to the average weekly sales data ranging from two weeks before a given poster collection to two weeks

29 customer panel evaluations of the posters), or (c) promoter attendance for brand j at store i in

week t.25 The variable Info sharing is equal to one if the store is treated (i.e., is part of group A)

and zero otherwise. Hypotheses 1 to 3 (predicting significant effects of the ISSC on the quality

of the creative work, job engagement, and financial performance) are tested by examining the

direction and significance of β2.

The controlsijt include the store and brand promoter characteristics described in Tables 1 and 2,

as well as brand fixed effects (since the brands have different types of products spanning

different price ranges). Appendix 4 defines the variables used in our analyses.

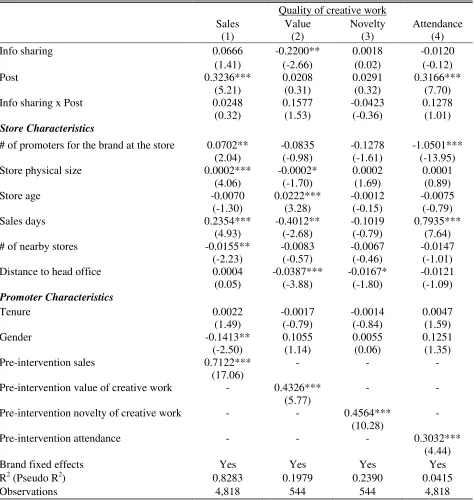

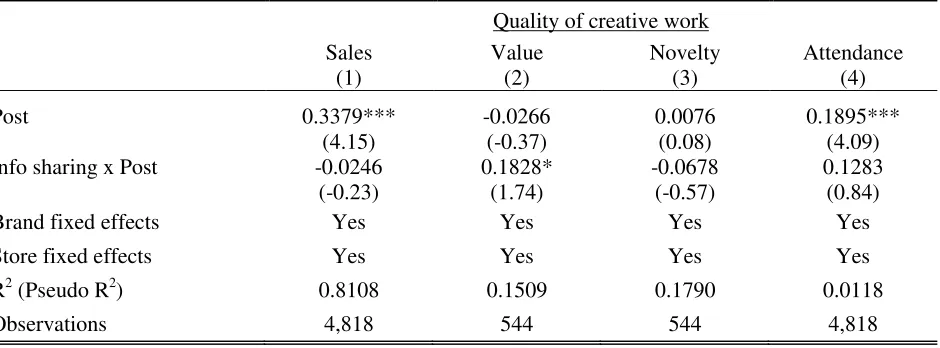

We first evaluate the average treatment effect of the ISSC on sales, the financial outcome (Table

3, column 1). Then, we run similar regressions to evaluate the average treatment effect of the

ISSC on important intermediary outcomes, that is, the quality of the creative work, measured

based on the value and novelty of the posters (Table 3, columns 2 and 3), and job engagement,

measured based on weekly promoter attendance (Table 3, column 4). Our results in Table 3

suggest that the introduction of the ISSC did not have a statistically significant effect on any of

the outcomes of interest. Based on our power analyses, we are 80% confident (1-β=0.8, using a

10% significance level, α=0.1) that, on average, the mere introduction of the ISSC did not

change our creative measures by 0.18 points or more on a 1-5 point scale; the promoters’

attendance by 0.23 or more days per week; or sales by 13% or more.26 We conduct a series of

25 For stores with two or more promoters for a given brand (which make up less than 10% of the store-brands) in a given week, the attendance variables and promoter-level characteristics are an average value across the promoters in the same store-brand. 26 These power analyses are based on regressions where we use brand and store fixed effects as our control variables and rely on

30 tests to ensure that our results are robust to alternative specifications. We rerun our analyses

making the following changes, one at a time:

a. We substitute all of our control variables for brand and store fixed effects (the results of

these tests are presented in Table 4).

b. We winsorize our sales variable at the 1st and 99th percentiles.

c. We re-include store-brand-weeks when the sales are equal to zero, as long as a brand

promoter attended the store in those weeks.

d. We re-include in our attendance measure cases when the promoter attended a different

store than his/her home store for 2 days or less in a month or when the (new) promoter

did not last more than a week with the company.

e. We re-include the month of November into the analyses (which we had excluded from

our main specification due to disruptions caused by the demonetization in India).

All, except the first, of these five specifications yield coefficients for the Info sharing x Post

variable that are statistically insignificant and similar in magnitude to the coefficients reported in

Table 3. The only analysis that produces somewhat different results (the first in the list above) is

presented in Table 4. In this case, the Info sharing x Post coefficient for the “Value of creative

work” variable becomes statistically significant. The coefficient in this case is only slightly

bigger than that in Table 3, and suggests that the introduction of MPR’s ISSC resulted in a

marginally significant increase in the value of the poster ratings of 0.18 points (in a 1-5 scale).27

27 The size of this coefficient is roughly equal to the minimum detectable effect size that we estimated for this analysis before

31

In summary, our results suggest that the ISSC did not significantly affect financial performance,

quality of creative output, or job engagement at the treatment stores. We conjecture that the lack

of results may be due to either (a) the limited extent to which salespeople accessed the ISSC28 or

(b) the inherent nature of the ISSC, which could have simultaneously provided useful

information to produce high quality posters but also triggered free-riding or other unintended

behaviors. To test our first conjecture, in section 4.4.1, we examine whether salespeople that

accessed the system more often were significantly impacted by the introduction of the ISSC. To

test our second conjecture, in section 4.4.2, we examine factors that could have increased or

decreased the benefits of the ISSC.

4.4. Additional Analyses

4.4.1. Effect of the Information Sharing System Contingent on Active Access to the System

We examine whether the lack of impact of the ISSC could be related to the promoters’ limited

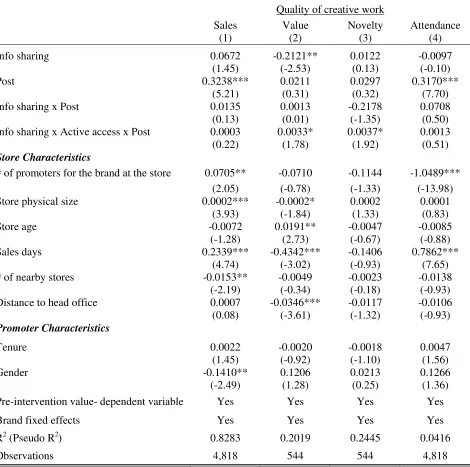

use of the system. Columns 2 and 3 of Table 5 show that the introduction of the ISSC was

associated with greater increases in the value of the creative work and the novelty of the creative

work when the store staff accessed (and used) the system more frequently. In terms of economic

significance, the ISSC was associated with an increase in the value (novelty) of creative work of

0.40 (0.23) points on a 1-5 point scale for the store(s) that used the system most often.29 These

increases in creativity are similar or larger than those resulting from providing creativity-based

28 This limited access, combined with the fact that the managing director drew significant attention to the relevance of creating high

quality posters across both treatment and control stores through the in-person workshops and the memoranda, may have diminished the power to distinguish a significant difference between the treatment and control groups.

29 We use data from Tables 1 and 5 to estimate the effect of the system for the stores that used the system most often on the value of

32 incentives to individuals (e.g. Kachelmeier et al. 2008 find increases in creativity ratings of 0.49

points on a 1-10 scale, following the implementation of such incentives).

The results in Table 5 are robust to several alternative specifications where we (a) winsorize

sales at the 1st and the 99th percentiles, (b) re-include observations where sales are equal to zero,

(c) re-include attendance measures when the promoter attended a different store than his/her

home store for 2 days in a month or less or did not last more than one week with the company,

and (d) when we re-include the month of November into the analyses. Yet the results change

slightly when we implement an additional specification: when we substitute all of our control

variables with brand and store fixed effects, the effect of the ISSC on our proxies for the quality

of creative work become insignificant. However, its effect on both sales and attendance becomes

significantly positive for stores where the staff accesses the system more frequently.

In addition to the different model specifications described above, we split the treatment stores

based on the median frequency of access of the system to control for any inherent differences

between treatment stores that used the system more frequently and those that used it less

frequently. We rerun the analyses including separate dummies for high access treatment stores

(i.e., where the frequency of access to the system was at or above the median of all the treatment

stores) and low access treatment stores (where the frequency of access was below the median),

and interacting those dummies with the Post indicator variable. Untabulated results show that,

for high access treatment stores, the introduction of the system was associated with a significant

increase in the value of creative work (Coef.=0.34, t-stat=2.38), and a positive but insignificant

increase in the novelty of creative work (Coef.=0.14, t-stat=1.33). These stores also experienced

33 Overall, our results provide evidence that the ISSC had a positive effect on the quality of creative

output (and to a limited extent, on the stores’ financial performance and job engagement) when it

was most frequently accessed.

We complement our analysis with qualitative insights on the extent to which salespeople were

accessing the system from the 19 interviews that we conducted at 8 of the treatment stores in

January. Although the salespeople found that the app was easy to use, about half of them cited

reasons why they did not access the system more often: forgetting their usernames, their

passwords, the link to the system, etc. Furthermore, our interviews suggested that several

promoters only used the system as a mechanism to upload rather than to actively browse posters

and many of them asked the head office to upload posters on their behalf. Most of them used the

system only when they were required to upload their posters.

Despite their limited use of the ISSC, all of the store managers and promoters interviewed stated

that they had found the new focus on creating posters very useful. They made several comments

praising the use of posters, such as: “There is a difference in a simple and a well-designed

handmade poster. The customer will definitely have a look at well-designed posters.” The

salespeople that more actively used the system suggested that the ISSC had changed the way

they made posters. Elaborating on this, one interviewee stated: “We take ideas from other posters

now.” Another one indicated: “There is always this thought in my mind that these posters are

going to be uploaded in the system and it changes the way I make posters.”

Based on the feedback gathered, and the results suggesting that salespeople accessing the system

34 to roll out the system to all of the stores, to promote more aggressively the use of the system, and

to make investments to create a more engaging user experience.

4.4.2. Conditions Affecting the Effect of the Information Sharing System on Outcomes

Whether a company would be better off letting ideas naturally emerge and spread throughout the

company (the current model of the company studied) or implementing an ISSC might depend on

the conditions of the stores. We explore three conditions that could lead to better or worse

economic outcomes associated with the implementation of an ISSC: the salespeople’s natural

exposure to others’ ideas, the creative talent of the salespeople, and the type of market they

served (mainstream vs. divergent).

a. Natural exposure to others’ ideas. Alternative channels to learn about others’ creative work

will likely diminish the potential benefits of an ISSC. At our site, promoters could potentially

learn about others’ posters by walking into nearby stores and looking at the posters. To

formally examine whether the system’s effect was greater in stores isolated from other MPR

stores, in Table 6 we split our samples into stores with more nearby stores (above the

median) and those with fewer nearby stores, rerun our baseline regressions, and compare the

treatment effects of the two subsamples. Although the level of exposure to other stores did

not affect the extent to which the system affected sales and attendance, our findings suggest

that the ISSC was associated with greater Value and Novelty of creative work in the

35

stores.30 The ISSC was associated with a 0.38 point increase on the 1-5 point scale measuring

the value of creative work (usefulness) and a 0.29 point increase on the 1-5 point scale

measuring novelty of creative work (attractiveness) in stores with fewer same-company

nearby stores. Interestingly, the system was also associated with a 0.30 decrease in the

novelty of creative work on the 1-5 point scale in stores with more same-company nearby

stores, where promoters may have been more aware that others could free-ride on their work.

b. Creative talent of the salespeople. Individual creative talent could affect the effectiveness of

the ISSC. On the one hand, if only a few individuals have creative talent at the stores, it may

be suboptimal to impose an ISSC that would require all individuals to spend time producing

creative work rather than focus on selling. On the other hand, even if many individuals lack

creative talent, their investment in developing posters could lead to greater engagement with,

and understanding of, their work, producing greater benefits. Furthermore, exposing the work

of creative individuals to their peers could further motivate them to develop higher-quality

sales posters. To explore the effect of creative talent on the effectiveness of the ISSC, we

compare the treatment effects between stores with higher-quality ex ante creative output

(above the median) with those with lower-quality ex ante creative output, rerun our baseline

regressions, and compare the treatment effects between the two subsamples. Table 7 suggests

that the effect of the system on the outcomes of interest was generally statistically

insignificant, regardless of the ex-ante creative talent of the salespeople. Yet, the effects of

the system were consistently positive for the subsample of stores with lower ex-ante creative

talent. A comparison of the Info sharing x Post coefficients across subsamples, suggests that

30 The difference in the Info sharing x Post coefficients between the subsamples with more vs. fewer nearby stores is statistically significant