Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 22:28

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Working Environment and the Research

Productivity of Doctoral Students in Management

Kiwan Kim & Steven J. Karau

To cite this article: Kiwan Kim & Steven J. Karau (2009) Working Environment and the Research Productivity of Doctoral Students in Management, Journal of Education for Business, 85:2, 101-106, DOI: 10.1080/08832320903258535

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832320903258535

Published online: 07 Aug 2010.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 73

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323

DOI: 10.1080/08832320903258535

Working Environment and the Research Productivity

of Doctoral Students in Management

Kiwan Kim and Steven J. Karau

Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois, USA

The authors examined the influence of creative personality and creative working environment on the research productivity of doctoral students in business. Students in management doctoral programs (N=200) participated in an online survey. The results show that faculty support was positively associated with research productivity. Among demographic predictors, doctoral candidacy and years in one’s present program were also positively associated with research productivity. The emergence of faculty support as the only significant environmental predictor of research productivity highlights the unique importance of faculty support, encouragement, and mentoring in developing the research potential of doctoral management students.

Keywords: Creative personality, Creative working environment, Doctoral students, Faculty support, Research productivity

A central concern in doctoral education is preparing students for future careers that require strong research skills. Thus, it is important to identify factors that might support research capability and productivity. Identifying such factors would allow faculty and administrators to focus energy and atten-tion on those specific aspects of the graduate school environ-ment that are most likely to yield improveenviron-ments in research productivity. Unfortunately, little research has examined ei-ther work environment or individual difference influences on the research productivity of doctoral students. Most creativ-ity scholars have focused on business organizations, paying little attention to the implications of creative working envi-ronment for academic organizations and doctoral programs. Yet, in order to carry out research successfully, doctoral stu-dents are likely to need access to key resources and sup-port from faculty, peers, and family. In the present study, we sought to address these gaps in the literature by examining the influence of creative working environment and creative personality on the research productivity of doctoral students. Thus, our research makes a distinctive contribution by ap-plying personality and situational variables that have been previously shown to affect creative performance in business contexts to the new context of academic business research

us-Correspondence should be addressed to Steven J. Karau, Department of Management, Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, IL, USA. E-mail: skarau@cba.siu.edu

ing a sample of doctoral management students in the United States.

In agreement with many prior discussions (Amabile, Conti, Coon, Lazenby, & Herron, 1996; Ford, 1996; Wood-man, Sawyer, & Griffin, 1993), we define creativityas the production of useful and novel products or ideas. In the broader organizational context, considerable prior research suggests that employee creativity contributes to organiza-tional performance. Organizaorganiza-tional scholars have identified a variety of contextual factors that may enhance employee creativity, including support from supervisors (Deci & Ryan, 1985, 1987) and colleagues (Madjar, Oldham, & Pratt, 2002; Zhou & George, 2001), adequate resources (Scott & Bruce, 1994), autonomy (Amabile et al.), and appropriate levels of time pressure (Amabile, 1988). In the context of doc-toral business programs, these factors logically extend to support from faculty and fellow students, adequate research and other resources, control over one’s own work, and ap-propriate temporal expectations. In contrast, factors such as conservatism, role conflict, and internal strife may inhibit employees from translating creativity into increased perfor-mance (Kimberley & Evanisko, 1981). Several influential perspectives (e.g., Amabile et al.; West & Farr, 1990; Wood-man et al) have overlapped in the identification of individual differences, work-related resources, and social influences as important influences on individual creative capacity. Consis-tent with those broader prior viewpoints on business organi-zations, we focused our study on creative personality, faculty

102 K. KIM AND S. J. KARAU

support, family support, colleague support, research re-sources, and workload pressures.

Personality and environmental factors are likely to af-fect creativity. Regarding personality, many researchers have proposed that creativity is closely related to cognitive abil-ity or style (Ford, 1996), personalabil-ity (Amabile; Barron & Harrington, 1981), and knowledge (Ford). In particular, a creative person may have characteristics such as original-ity, flexibiloriginal-ity, elaboration, intuition, divergent thinking, cu-riosity, self-confidence, and energy (Amabile; Barron & Harrington; Ford). Oldham and Cummings (1996) character-ized highly creative people as capable, clever, intelligent, in-ventive, and reflective, and characterized less creative people as cautious, conservative, and mannerly. These viewpoints suggest that people with certain characteristics perform well in creative contexts. Because successful research requires doctoral students to generate ideas, develop sound research designs, and analyze complex data, we predicted that creative personality would be positively associated with the research productivity of doctoral students.

Hypothesis 1(H1): The individual creative personality of

doc-toral students is positively associated with research pro-ductivity.

Regarding environmental factors, prior creativity research on business organizations has suggested that productivity on work that requires creativity can be enhanced by sup-port from the organization or supervisor (Amabile et al.; Scott & Bruce, 1994), support from family and friends (Madjar et al., 2002), the availability of sufficient resources (Amabile et al.; Scott & Bruce), appropriate workload pressures (Amabile), and freedom or autonomy (Amabile et al.; Oldham & Cummings, 1996; Scott & Bruce). A num-ber of studies have demonstrated that supervisory style influ-ences employee creativity at work (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 1985, 1987; Shalley, 1991). Supportive supervisors show concern for employees’ feelings and needs, encourage the expression of opinions, promote interest in work activities, and provide positive feedback (Deci & Ryan, 1985). In doctoral educa-tion, the complexities involved with research projects may enhance the importance of mentoring and supervision in al-lowing students to understand how to translate their creative ideas into feasible research projects and papers. Consistent with this logic, Weidman and Stein (2003) suggested that social interactions between students and faculty stimulate a student’s research productivity by creating a supportive en-vironment. With this evidence in mind, we reasoned that faculty support would enhance doctoral students’ research productivity.

H2: Support from faculty is positively associated with

re-search productivity.

Research on stress and burnout has shown that support from family members and friends outside of the workplace

can help people cope with negative aspects of the workplace (e.g., Ryan & Miller, 1994) and can also enhance positive out-comes such as creative performance (e.g., Koestner, Walker, & Fichman, 1999; Madjar et al., 2002). We expected these more general findings to also apply to the academic research context, such that psychological and social support from fam-ily and friends would have a positive influence on research productivity.

H3: Support from family and friends is positively associated

with research productivity.

A variety of studies suggest that collaboration among di-verse associates has a positive association with creative per-formance. For example, Kasperson (1978) suggested that sci-entists that interact across disciplines make a more innovative contribution. Payne (1990) found that internal and external group communication had a positive association with team performance. Scott and Bruce (1994) found that the cohe-siveness of a work group influenced members’ willingness to voice their ideas and opinions. Consistent with this prior work, we reasoned that doctoral students who get support from colleagues would attain higher levels of research pro-ductivity.

H4: Support from colleagues is positively associated with

research productivity.

Many scholars have claimed that the provision of ade-quate resources is closely related to organizational perfor-mance (Damanpour, 1991; Delbecq & Mills, 1985). Besides the obvious practical limitations of extreme resource restric-tions, individuals’ views about the sufficiency of resources can also influence their perceptions of the intrinsic value of projects (Farr & Ford, 1990; Payne, 1990). In a similar vein, educational researchers have argued that resource availabil-ity can have an impact on academic performance. A study of accounting professors found that the availability of re-sources such as research assistants, information technology, and editorial help contributed to research productivity (King and Henderson, 1991). Brewer and Brewer (1990) found that research productivity was related to perceptions of the avail-ability of research resources such as research assistants, sec-retarial help, computers, and libraries. These general findings are also likely applicable to the context of doctoral students in management. Therefore, we predicted that research resources would be positively related with research productivity.

H5: Research resources are positively associated with

re-search productivity.

Although excessive workload pressures might undermine creativity, prior research has shown that some degree of pressure can actually promote creativity when individu-als perceive the pressure as appropriate to the inherent challenges of the work (Amabile). Similarly, time pres-sure has been found to promote creativity in research and

development scientists, except when that pressure reached an undesirably high level (Andrews & Farris, 1972). Regarding doctoral students, workload pressures are likely to come from coursework, research projects, and assistantship work. Given that these pressures would likely be viewed as reason-able and necessary to the academic enterprise, we predicted that workload pressures would be positively associated with research productivity among doctoral students.

H6: Workload pressures are positively associated with

re-search productivity.

In summary, we hypothesized that creative personality and five work environment factors—support from faculty, support from family and friends, support from colleagues, research resources, and workload pressures—would all have a positive influence on doctoral students’ research produc-tivity. We tested these hypotheses using an internet survey of doctoral management students. We assessed all predictor variables using established, previously validated measures, and assessed research productivity based on total scholarly output during a 5-year period.

METHOD

Setting, Participants, and Procedure

We recruited doctoral students in management and management-related areas from business schools in the United States. Using the Carnegie Classification (Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching, 2000) and business school accreditation Web sites, we identified 103 business schools that offered doctoral degrees in management and management-related areas. We included departments la-beled (by the business school) as management departments or departments of traditional management areas (e.g., or-ganizational behavior, organization theory, strategy, human resources, international business, entrepreneurship, produc-tion and operaproduc-tions, decision science, management science, supply-chain management, information technology, manage-ment information systems). We also included doctoral stu-dents in departments housed in business schools and labeled as areas related to management (e.g., industrial and orga-nizational psychology, industrial and labor relations, small business, and project management).

Using university, college, and department Web sites for these programs, we identified a total of 943 e-mail addresses of doctoral students. We contacted prospective participants in two waves (separated by 6 weeks) by e-mail to invite them to participate in our online survey. The first wave produced 186 responses (165 useable), and the second wave produced an additional 45 responses (35 useable). Thus, the final sam-ple size constituted of 200 participants (54.5% men, 45.5% women), representing a response rate of 21.2%. Within this final sample, 63% of respondents were married (with a M

of 0.72 children, SD=1.03) and 48% were doctoral candi-dates (i.e., had attained ABD status). The mean time at each individual’s present program was 2.95 years (SD=1.57).

Measures

For our predictor variables, we selected previously validated instruments with good-to-excellent internal consistency and good apparent face validity. Where possible, we also selected fairly brief scales to keep the length of our survey reasonable and encourage participation. For research productivity, we used a self-report measure of total scholarly manuscripts accepted for publication or presentation during a five-year period.

Creative Personality

We measured creative personality using the 30-item Cre-ative Personality Score index (CPS; Gough, 1979). This in-dex has been used frequently to assess creative personality (Oldham & Cummings, 1996). Gough demonstrated conver-gence between the CPS and expert ratings of the creativity levels of individuals in a variety of creative contexts. Re-spondents are given 30 adjectives and asked to check all that describe themselves well. A score of “+1” is assigned to adjectives typical of creative people, and a score of “–1” is as-signed to adjectives atypical of creative people, with possible total scores ranging from –12 to 18. Oldham and Cummings reported a reliability of.70 for the CPS. The reliability in the present study was .67.

Support from Faculty

We adopted 7 items from Weidman and Stein (2003;

α=.84, items assessed using 7-point scales). Items assessed the extent to which faculty were accessible, aware of student concerns, engaging students in scholarly activities, and were available to discuss academic and other matters (α=.83 in the present sample).

Support from Colleagues

We used the 7-item scale from Podsakoff, Ahearne, and Mackenzie (1997;α=.95). Items asked respondents how much their colleagues were helpful in work, sharing their ex-pertise, and encouraging one another (α=.92 in the present sample).

Support from Family and Friends

We measured support from family and friends with the 4-item scale developed by Caplan, Cobb, French, Harrison, and Pinneau (1975;α=.86). Items addressed the degree to which family and friends were willing to support individuals and help them deal with work responsibilities (α=.80 in the present sample).

104 K. KIM AND S. J. KARAU

Research Resources

We employed a 6-item scale from Scott and Bruce (1994;

α =.77). Items assessed the degree to which adequate re-sources, assistance, funding, and personnel were available to support creativity and innovation. We made slight wording changes in some items in order to make them appropriate to an academic organization (α=.82 in the present sample).

Workload Pressures

We measured workload pressures using the 5-item scale from Hamel and Bracken (1986;α=.81). Items asked how frequently the job required a lot of work to be done in a limited amount of time (α=. 86 in the present sample).

Research Productivity

Using separate questions, we asked respondents to report how many journal articles, conference proceedings or presen-tations, books, and chapters in edited books they had pub-lished or presented during the previous 6 years (2002–2006). Initial analyses showed the same general pattern of results whether we used individual measures or indices that com-bined across measures. Thus, we present our results in terms of a total research productivity index that adds journal arti-cles, conference papers, books, and book chapters.

RESULTS

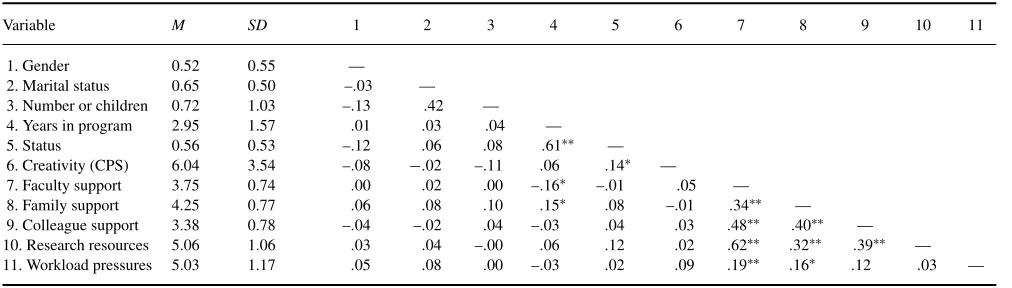

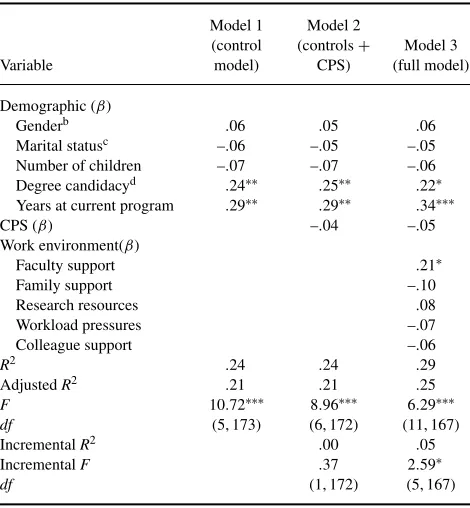

We tested our hypotheses using multiple regression analyses. Table 1 presents means, standard deviations, and correlations. Table 2 presents our key analyses. Model 1 shows that demo-graphic variables explained 24% of the total variance in re-search productivity. Among significant demographic predic-tors, doctoral candidacy and years at the individual’s present program were both positively associated with research pro-ductivity. Model 2 tested the effect of creative personality

on research productivity (H1), over and above demographic

variables. This model indicates that creative personality did not explain significant variability in research productivity and that the addition of CPS made no incremental contribu-tion toR2. Hence, Hypothesis 1 was not supported. Model

3 tested the influence of faculty support (H2), family and

friend support (H3), support from colleagues (H4), research

resources (H5), and workload pressures (H6) on research

productivity, controlling for creative personality and demo-graphic variables. The results show that there was only one significant relationship between creative-environment vari-ables and research productivity: Namely, faculty support had a significant, positive relationship with research productiv-ity. Hence,H2 was supported but H3–6were not supported.

The addition of creative-environment variables produced a significant increase inR2, indicating that environmental fac-tors added significant explanatory power over demographic predictors and personality and explained an additional 5% of the variance in research productivity.

DISCUSSION

Our results show that support from faculty has a significant impact on the research productivity of management doctoral students. This result is consistent with previous findings from business organizations (e.g., Deci & Ryan, 1985, 1987) as well as with prior educational research (Weidman & Stein, 2003). The present results extend this prior work to doctoral management education and suggest that faculty support is important to the development of research skills and resulting research productivity. Given the absence of other significant predictors of research productivity, each of which had been shown to be important in prior organizational studies, fac-ulty support may take on special importance. With the many complexities, subtleties, and judgment calls that can arise in research projects, our results suggest that a primary avenue

TABLE 1

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations

Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

1. Gender 0.52 0.55 —

2. Marital status 0.65 0.50 –.03 —

3. Number or children 0.72 1.03 –.13 .42 —

4. Years in program 2.95 1.57 .01 .03 .04 —

5. Status 0.56 0.53 –.12 .06 .08 .61∗∗ —

6. Creativity (CPS) 6.04 3.54 –.08 −.02 –.11 .06 .14∗ —

7. Faculty support 3.75 0.74 .00 .02 .00 –.16∗ –.01 .05 — 8. Family support 4.25 0.77 .06 .08 .10 .15∗ .08 –.01 .34∗∗ — 9. Colleague support 3.38 0.78 –.04 –.02 .04 –.03 .04 .03 .48∗∗ .40∗∗ — 10. Research resources 5.06 1.06 .03 .04 –.00 .06 .12 .02 .62∗∗ .32∗∗ .39∗∗ — 11. Workload pressures 5.03 1.17 .05 .08 .00 –.03 .02 .09 .19∗∗ .16∗ .12 .03 —

Note.Variables were coded as the following: Male=0, Female=1; Not married=0, Married=1; Non-ABD=0, ABD=1. ∗p<.05.∗∗p<.01.

TABLE 2

Research Productivity as a Function of Demographics, CPS, and Work Environment

Variable

Faculty support .21∗

Family support –.10

Research resources .08

Workload pressures –.07

Colleague support –.06

R2 .24 .24 .29

Note.Variables were coded as the following: Male=0, Female=1; Not married=0, Married=1; Non-ABD=0, ABD=1. CPS=Creative Personality Score index (H. G. Gough, 1979).

∗p<.05.∗∗p<.01.∗∗∗p<.001.

for enhancing doctoral students’ research skills is the active support, involvement, and mentoring of faculty members.

The hypotheses that did not receive support are also inter-esting. Because past studies have shown creative personality to be a significant predictor of creative performance in busi-ness organizations, it is intriguing that those results did not extend to research productivity in the present study. With re-gard to family support, colleague support, research resources, and workload pressures, none of these variables showed a significant relationship with research productivity within the present sample. One plausible general interpretation for all of these null results concerns range restriction issues. Doctoral-granting research-oriented universities are likely to provide at least adequate research resources to doctoral students and often select those students from large applicant pools based partially on their creativity, research capabilities, and prior research accomplishments. Thus, our participants may share many similarities in that they have a higher creative personal-ity (M=6.09, SD=3.54) than employees in manufacturing companies studied in prior work (M=0.15 in Madjar et al., 2002;M =4.26 in Oldham & Cummings, 1996). It would be a promising research area to examine these same predic-tors in a wider variety of academic contexts and university environments.

With regard to demographic variables, the status of doctoral students was a significant predictor of research

productivity, meaning that students who had reached degree candidacy had higher research productivity than non-ABD students. Similarly, the year in the individual’s present pro-gram was also a significant predictor, indicating that tenure within a doctoral program is associated with research pro-ductivity. These results are likely attributable to more experi-enced students having more research experience and contact with faculty as well as having accumulated more time to con-duct research projects that have progressed through the peer review process.

Although our research takes an important first step of ex-amining creative personality and creative work-environment influences on research productivity among business doctoral students, it also had some limitations that might be addressed by future researchers. First, our response rate of 21.2% raises the possibility that the sample might not be representative of all management doctoral students. Similarly, our focus on management students (chosen to allow a common basis of research comparison) did not allow us to draw broader con-clusions about the full scope of research productivity in all business majors or to wider disciplinary contexts. Second, although environmental factors explained significant incre-mental variability in research productivity, the addition to

R2 was small (5%). Overall, all predictors explained 29%

of variance, suggesting that most of the variance in research productivity is explained by other factors not examined in the present research. Additional environment variables impli-cated in productivity and stress literature, such as role conflict and role ambiguity, could be studied by future researchers. Third, our use of self-report data raises the potential for common-method bias. Finally, we note that we measured research productivity based on the quantity of publications, conferences, and book chapters. Although research produc-tivity in terms of publications is certainly a key outcome in the academic world, given variation in the quality of jour-nals and conferences, the use of more qualitative measures in future research might reveal additional information.

In spite of these limitations, our research nevertheless contributes valuable initial insights into how working envi-ronment may influence the research performance of manage-ment doctoral students, and documanage-ments that faculty support enhances research productivity in this context. In the past, creativity scholars have been less interested in academic or-ganizations than business oror-ganizations. However, academic organizations are valuable to study due to their inherently creative nature. We hope our research stimulates further in-quiry into the dynamics of creative working environments in business schools and other university environments.

REFERENCES

Amabile, T. M. (1988). A model of creativity and innovation in organiza-tions. In B. M. Staw & L. L. Cummings (Eds.),Research in organizational behavior(pp. 123–167). Greenwich, CT: JAI Press.

106 K. KIM AND S. J. KARAU

Amabile, T. M., Conti, R., Coon, H., Lazenby, J., & Herron, M. (1996). Assessing the work environment for creativity.Academy of Management Journal,39, 1154–1184.

Andrews, F. M., & Farris, G. F. (1972). Time pressure and performance of scientists and engineers: A five year panel study.Organizational Behavior and Human Performance,8, 185–200.

Barron, F. B., & Harrington, D. M. (1981). Creativity, intelligence, and personality.Annual Review of Psychology,32, 439–476.

Brewer, P. D., & Brewer, V. L. (1990). Promoting research productivity in college of business. Journal of Education for Business, 45, 875– 883.

Caplan, R. D., Cobb, S., French, P., Harrison, R. V., & Pinneau, S. R. (1975).

Job demands and worker health. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare.

Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching. (2000). The Carnegie classification of institutions of higher education (2000 edi-tion). Stanford, CA: Author.> Retrieved September 1, 2006, from http://www.carnegiefoundation.org/classifications/index.asp

Damanpour, F. (1991). Organizational innovation: A meta-analysis of ef-fects of determinants and moderators.Academy of Management Journal,

Academy of Management Journal, 555–590.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1985). Intrinsic motivation and self-determination in human behavior. New York: Plenum.

Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (1987). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,53, 1024–1037.

Delbecq, A. L., & Mills, P. K. (1985). Managerial practices that enhance innovation.Organizational Dynamics,14, 24–34.

Farr, J. L., & Ford, C. M. (1990). Individual innovation. In M. A. West & J. L. Farr (Eds.),Innovation and creativity at work(pp. 63–80). Chichester, England: Wiley.

Ford, C. (1996). A theory of individual creative action in multiple social domains.Academy of Management Review,21, 1112–1142.

Gough, H. G. (1979). A creative personality scale for the adjective check list.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,37, 1398–1405. Hamel, K., & Bracken, D. (1986). Factor structure of the job stress

question-naire (JSQ) in three occupational groups.Educational and Psychological Measurement,46, 777–786.

Kasperson, K. J. (1978). Scientific creativity: A relationship with informa-tion channels.Psychological Reports,42, 691–694.

Kimberley, J. R., & Evanisko, M. J. (1981). Organizational innovation: The influence of individual, organizational and contextual factors on hospital adoption of technological and administrative innovations.Academy of Management Journal,24, 689–713.

King, J. G., & Henderson, J. R. (1991). Faculty research from the perspec-tive of accounting academicians.Journal of Education for Business,66, 203–207.

Koestner, R., Walker, M., & Fichman, L. (1999). Childhood parenting ex-periences and adult creativity.Journal of Research in Personality,33, 92–107.

Madjar, N., Oldham, G. R., & Pratt, M. G. (2002). There is no place like home? The work and non-work creativity support to employees’ creative performance.Academy of Management Journal,45, 757–767.

Oldham, G. R., & Cummings, A. (1996). Employee creativity: Personal and contextual factors at work.Academy of Management Journal,39, 607–634.

Payne, R. (1990). The effectiveness of research teams: A review. In M. A. West & J. L. Farr (Eds.),Innovation and creativity at work(pp. 101–122). Chichester, England: Wiley.

Podsakoff, P. M., Ahearne, M., & Mackenzie, S. B. (1997). Organizational citizenship behavior and the quality and quantity of work group perfor-mance.Journal of Applied Psychology,2, 262–270.

Ryan, E. B., & Miller, K. I. (1994). Social support home/work stress and burnout: Who can help?Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 30, 357–373.

Scott. S. G., & Bruce, R. A. (1994). Determinants of innovative behavior: A path model of individual innovation in the workplace.Academy of Management Journal,37, 580–607.

Shalley, C. E. (1991). Effects of productivity goals, creativity goals, and per-sonal discretion on individual creativity.Journal of Applied Psychology,

76, 179–185.

Weidman, C. J., & Stein, E. L. (2003). Socialization of doctoral students to academic norms.Research in Higher Education,44, 641–657. West, M. A., & Farr, J. L. (1990).Innovation and creativity at work.

Chich-ester, England: Wiley.

Woodman, R. W., Sawyer, J. E., & Griffin, R. W. (1993). Toward a theory of organizational creativity.Academy of Management Review,18, 293–321. Zhou, J., & George, J. M. (2001). When job dissatisfaction leads to creativity: Encouraging the expression of voice.Academy of Management Journal,

44, 682–696.