Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 21:57

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Linking Course-Embedded Assessment Measures

and Performance on the Educational Testing

Service Major Field Test in Business

Gustavo A. Barboza & James Pesek

To cite this article: Gustavo A. Barboza & James Pesek (2012) Linking

Course-Embedded Assessment Measures and Performance on the Educational Testing Service Major Field Test in Business, Journal of Education for Business, 87:2, 102-111, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.576279

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2011.576279

Published online: 15 Dec 2011.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 90

View related articles

JOURNAL OF EDUCATION FOR BUSINESS, 87: 102–111, 2012 CopyrightC Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2011.576279

Linking Course-Embedded Assessment Measures

and Performance on the Educational Testing Service

Major Field Test in Business

Gustavo A. Barboza and James Pesek

Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Clarion, Pennsylvania, USA

Assessment of the business curriculum and its learning goals and objectives has become a major field of interest for business schools. The exploratory results of the authors’ model using a sample of 173 students show robust support for the hypothesis that high marks in course-embedded assessment on business-specific analytical skills positively affect performance on overall business disciplinary competence proxy by results in the Major Field Test in Business (MFT-B) examination, while controlling for SAT score, GPA, major, and gender differences. This particular result provides useful and relevant information to advance the assessment process in schools of business as a valuable tool to enhance the overall learning experience. The authors also found a marked difference across majors.

Keywords: assessment, business disciplinary competence, learning goals and objectives

Assessment of learning goals and objectives across the busi-ness curricula is increasingly receiving significant attention as an important task conducive to successful Assurance of Learning (AoL) and a driver for accreditation processes. In this regard, assessment of learning goals plays a predominant role in determining and evaluating students’ performance and effectiveness in achieving overall business competence. Not surprisingly, in recent years, a growing interest has been ob-served in the literature on learning outcomes assessment for business students, in part, due to the emphasis that the Associ-ation to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) International has placed on AoL since 2003. For example, based on surveys conducted at several AACSB-accredited schools in 2004 and 2006, Martell (2007) confirmed the dra-matic progress those institutions made in developing and supporting their AoL activities, including spending an aver-age of$20,000 on AoL activities in 2006—a fivefold increase over 2004. Using the 2006 survey results, Martell listed the most popular direct methods of assessment as the following: evaluating written and oral assignments with rubrics, course-embedded assessments, evaluating cases with a rubric, us-ing the Educational Testus-ing Service (ETS) Major Field Test

Correspondence should be addressed to Gustavo A. Barboza, Clarion University of Pennsylvania, Department of Administrative Science, 319 Dana Still Hall, Clarion, PA 16214, USA. E-mail: [email protected]

in Business (MFT-B; Educational Testing Service, 2011), and systematically evaluating teamwork. However, Martell posed the question as to whether certain populations of stu-dents demonstrate different levels of achievement on learn-ing goals, and added that uncoverlearn-ing those differences may identify groups of students that may require remediation or represent model practices or delivery systems that others may emulate.

In this regard, a common practice across the assess-ment literature indicates a strong preference for using the ETS MFT-B as the preferred measure of business disci-plinary competence. As Bush, Duncan, Sexton, and West (2008) reported, the MFT-B has been found to be a very good way of assessing student learning outcomes. It also provides users with baseline data and the opportunity to benchmark students’ performances against national norms, and measure possible student learning outcome variations across nine business subjects: accounting, economics, man-agement, quantitative business analysis, finance, marketing, legal and social environment, information systems, and in-ternational issues. Although some faculty have expressed concerns about the content validity of the MFT-B (see Bycio & Allen, 2007), Gerlich and Sollosy (2008) noted that the MFT-B has become for many the de facto standard of standardized assessment instruments for business programs. In Martell’s (2007) survey, 46% of the respondents indicated that their institutions were using the MFT-B.

LINKING COURSE-EMBEDDED ASSESSMENT MEASURES 103

From an empirical point of view, several researchers—using similar approaches—have investi-gated the determinants of business disciplinary competence as the main driver of AoL. For example, Allen and Bycio (1997); Bycio and Allen (2007); Gerlich and Sollosy (2008); Marshall (2007); Terry, Mills, and Sollosy (2008); and Bush et al. (2008), among others, have attempted to address some of Martell’s (2007) questions by conducting studies analyzing assessment results. These studies have involved one or more of the following predictor variables: overall grade point average (GPA), business core GPA, SAT or ACT scores, gender, academic business major, grades earned in certain courses, student motivations, and international students and transfer students, and have found consistent evidence of their effects on the dependent variable for business disciplinary competence, the ETS MFT-B.

More specifically, Bycio and Allen (2007) found a posi-tive and significant effect of students’ GPA in business core classes on MFT-B performance. In addition, the overall GPA and general intellectual aptitude (as reflected by SAT Ver-bal and SAT Math performance) predicted MFT-B scores equally well. In addition, the researchers noted a signifi-cant improvement in MFT-B performance as a function of course credit incentive offerings (Bycio & Allen, 2007). While controlling for gender, age, ACT scores, and GPA, Black and Duhon (2003) found that management majors were at a significant disadvantage relative to all other business majors.

Terry et al. (2008) examined the determinants of student performance on the MFT-B with a focus on student moti-vation using percentile scores on the MFT-B as the depen-dent variable and ACT and SAT scores, GPA, transfer status, international student, gender, and two motivation variables as independent variables. Similar to other studies, Terry et al. found that academic ability, as measured by the ACT and SAT, and GPA were statistically significant variables. Other demographic variables were not statistically signifi-cant. However, the two motivation variables, a 10% applica-tion of the ETS score to the final course grade and a 20% application of the ETS score to the final course grade, were both positive and statistically significant.

Marshall (2007) conducted a study involving types of business majors, gender, transfer students, and grade per-formance in selected courses, including the capstone course in business. She discovered that overall, accounting and fi-nance majors generally scored better than any of the other majors, particularly management and marketing majors. In comparing her results, which centered on GPAs and grades in the business capstone course, and the studies that used the MFT-B scores, she concluded that differences in per-formance existed among majors in business programs. In a related issue, Allen and Bycio (1997), using the MFT-B as an assessment measure, found that there was an overall sig-nificant difference in the MFT-B performance as a function of business major.

No¨el, Michaels, and Levas (2003) collected questionnaire data from graduating seniors at two regionally diverse uni-versities and found differences in accounting and marketing majors’ personality and self-monitoring behaviors, noting that marketing types were creative, easygoing, and enthu-siastic, whereas accountants were more likely to be more reserved, practical, and prone to use concrete and focused thinking. Such behaviors help explain why some business students select a particular major (No¨el et al.). Of course, it may be a good thing that those who work in accounting are not too creative! Differences in pedagogical preferences and personality and self-monitoring behaviors may help ex-plain performance differences on the MFT-B among majors. Ulrich (2005) provided similar results supporting this argu-mentation.

The implicit assumption and common factor among the studies mentioned previously is that a successful assessment process—one that meets or exceeds expectations—should positively affect the scores in the standard measure of business disciplinary competence. The positive effects that assessment practices may have on ETS MFT-B perfor-mance are then captured, most commonly, through its in-teraction with variables such as business core GPA and overall GPA, (i.e., ∂MF T∂GP A−B >0). The remaining observed portion of the business competence variation is then ex-plained by control variables such as, but not limited to, SAT scores—∂MF T∂SAT−B >0—and demographics such as gender and major. However, a common shortcoming of the previous studies is that none of them used course-embedded assess-ment specific variables as determinants of overall business competence. In particular, understanding the role that assess-ment processes and corresponding instruassess-ments used in this process has received little attention in the literature. This is to say that the role, direction, and magnitude effects that as-sessment instruments may have in advancing and achieving the overall goal of business disciplinary competence remains unanswered.

Thus, despite the advances made in understanding the determinants of business disciplinary competence, as mea-sured by performance in the ETS MFT-B, the role of course-embedded instruments as they relate to linking assessment ef-forts to achieve learning goals and objectives and their effects on higher demonstration of business disciplinary competence remains largely unexplained. Therefore, in this exploratory study we aimed to advance the understanding of assurance of learning and its relevance for demonstrating business dis-ciplinary competence by expanding on previous research and measuring the significance and explanatory power of endogenous and program-specific course-embedded assess-ment measureassess-ments, along the lines of business-specific an-alytical knowledge and writing skills, and their effect on student performance on the MFT-B (business disciplinary competence). In the next section, we describe the program setting and corresponding learning goals and objectives and how they relate to the assurance of learning and assessment

104 G. A. BARBOZA AND J. PESEK

Goal 1.0 – Demonstrate Business Disciplinary Competence

Objective 1.1 Knowledge in the key business disciplines. Key business disciplines shall include accounting, economics, finance, management, and marketing.

Goal 2.0 – Show an Awareness of the Ethical Dimensions of Business Issues

Objective 2.1 Knowledge and ability to examine ethical issues in business

Objective 2.2 An understanding of the social forces shaping the environment of business

Goal 3.0 – Communicate Effectively Orally and in Written Form

Objective 3.1 Demonstration of effective oral communication skills Objective 3.2 Demonstration of effective written communication skills

Goal 4.0 – Demonstrate Analytical Thinking Skills

Objective 4.1 Interpretation of evidence

Objective 4.2 Identification and evaluation of points of view Objective 4.3 Formulation of warranted, non-fallacious conclusions

Goal 5.0 – Understand Global Issues in the Functional Areas of Business

Objective 5.1 Understanding the forces affecting businesses that operate in the global economy

Goal 6.0 – Demonstrate Effective Use of Technology and Data Analysis

Objective 6.1 Demonstration of communication and presentation technologies used in the business environment

Objective 6.2 Understanding of and ability to use common methods of statistical inference Objective 6.3 Understanding of data analysis and its use in business decision making

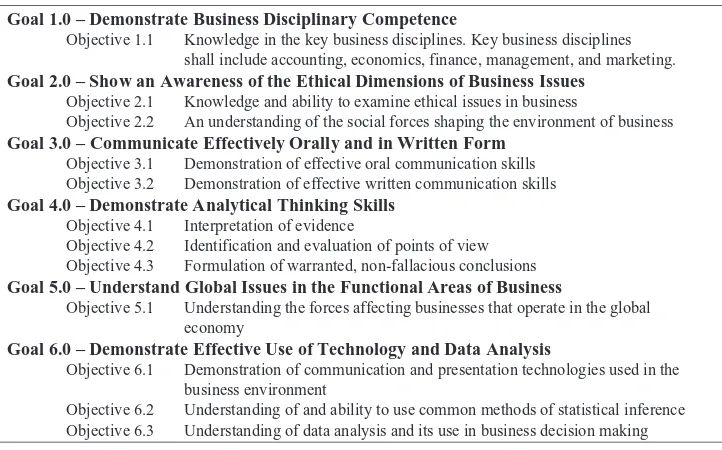

FIGURE 1 Bachelor of Science in business administration learning goals and objectives.

measures. We then present the model specification and dis-cuss the data and empirical approach, followed by the analy-sis and discussion of results. We end with recommendations and conclusions.

SETTING AND BACHELOR OF SCIENCE IN BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION (BSBA)

ASSESSMENT BACKGROUND

The setting for this study is a small, mid-Atlantic rural state university with approximately 7,300 students. The univer-sity’s primary mission is teaching and learning, as it offers over 50 undergraduate majors and 11 master’s degree pro-grams. Although the university admits students from a wide range of backgrounds, it does not have an open access admis-sions policy. Over the last five years, university admisadmis-sions acceptance rates for first-time freshmen ranged from a high of 78% for fall 2005 to a low of 68.5% for fall 2009. The overall average SAT score (using only the verbal and mathe-matics scores) for regular admitted students over the last five years (fall 2005 through fall 2009) has ranged from a low of 999 in fall 2006 to a high of 1006 in fall 2007.

In the business program, approximately 88% of the busi-ness majors were White or non-Hispanic and 80% were res-idents of the state. Although 63% of the university’s student body was female, 54% of those majoring in business were male. The College of Business Administration (COBA) has been accredited since the late 1990s by AACSB International. Undergraduate students in COBA are offered eight majors: accounting, economics, finance, marketing, management, in-ternational business, industrial relations, and real estate.

To assess student learning, the COBA developed six learn-ing goals with correspondlearn-ing objectives and standard rubrics

to conduct assessment. The program performs continuous assessment of all learning goals on a yearly basis at different points in the curriculum. In addition, the program adminis-ters the ETS MFT-B as an external measure for assessment of learning goal 1.0 (i.e., demonstrate business disciplinary competence). In particular, in this study we focused only in data corresponding to goals 1.0, 3.0 (objective 3.2), and 4.0 (see Figure 1), and its corresponding assessment of the capstone course senior project on strategic management (we explain in further detail subsequently).

MODEL

As indicated previously, the interest of this study was to determine the effects and significance of course-embedded assessment measures—in particular business-specific ana-lytical skills and overall writing skills—and other demo-graphic information on demonstrating business disciplinary competence. To this purpose, we proposed to use a par-simonious model description—similar to that found in the literature—that follows the general specification of

yi =xi′β+εi. (1)

where εi is the errors term and is assumed to be an inde-pendent and identically distributed random variable as usual;

x′

i is the matrix of explanatory variables;β is the vector of coefficients to be estimated; andyiis the measure of business disciplinary competence. The vector of independent variables includes the conventional demographic elements of gender and major. It also includes GPA and the SAT scores (to-tal [SATT], verbal [SATV], and mathematics [SATM]). The model in Equation 1 expands on the existent literature by adding the endogenous academic performance variable of

LINKING COURSE-EMBEDDED ASSESSMENT MEASURES 105

business-specific analytical skills and overall writing skills (see Appendix).

Thus, we proposed to estimate empirically the following equation:

MF T −Bi =α0+α1SAT(T =V +M)i

+α2GP Ai+βiMaj ori

+α3Analyt icali+α4W rit ingi+εi (2)

where MFT-Bi score is the dependent variable and is used as an external (exogenous) performance measure to assess learning goal 1.0 (demonstrate business disciplinary compe-tence; see BSBA Goal 1.0 in Figure 1). We selected MFT-B1 as our dependent variable for several reasons. The first rea-son is because it is an exogenous variable to the program and therefore eliminates any possible endogeneity problems with the rest of the variables that were determined within the program in our model specification. Second, the MFT-B is a preferred measure of business disciplinary competence because it is a nationally administered test and assumed to be normally distributed. Last, we selected MFT-B as our dependent variable to obtain the highest possible degree of comparison with previous research in this field, which proves useful when assessing the implications of our findings.

The explanatory variables of performance in the ETS MFT-B exam are the following: (a) GPA, the cumulative GPA at the time students took the MFT-B examination, thus GPA is not influenced by MFT-B scores and vice versa; (b) academic major, a dummy variable for the student’s declared major when taking the ETS MFT-B1; (c) SATT (and its cor-responding decomposition between SATV and SATM) is the students’ aptitude score as a measure of student capabili-ties used for admission purposes2; (d) gender is a dummy variable for the population composition between females (1) and males (0); (e) analytical is overall score in the course-embedded assessment measure of the business-specific an-alytical knowledge competence of the final paper for the capstone course in business along seven business-specific dimensions3; and (f) writing is the course-embedded assess-ment measure of the written component along five dimen-sions4of the same paper for the capstone course as they relate to the learning goals 4.0 and 3.0, respectively (see Figure 1 and the Appendix).

Although previous research has acknowledged the role that student motivation may play in performance on the MFT-B (see MFT-Black & Duhon 2003), instructors in the capstone course did not provide bonus points or a grade incentive for the students. Rather, instructors encouraged students to try their best since good performance on the exam could be included on a resume or graduate school admissions appli-cation.

Based on the model outlined in Equation 2, we advanced the following hypotheses, and proceeded to test them empir-ically:

Hypothesis 1(H1):α2>0 Higher GPA would correspond to higher MFT-B scores, all other things being equal, and demonstrating that a better comprehension of the aca-demic curriculum would reflect a higher performance in demonstrating business disciplinary competence (learn-ing goal 1).

H2:α1>0 Higher scores on the SAT (verbal and mathemat-ics) exam would have a positive (and possibly increas-ing) effect on the MFT-B performance as they relate positively to test-taking ability and native intellectual ability.

H3:γ1≈γ2=0 Gender differences would not have an effect on demonstrating business disciplinary competence as measured by the MFT-B exam.

H4: α3>0 Higher scores in the business-specific analyti-cal skill learning goal assessment results would have a positive impact in demonstrating business disciplinary competence, and therefore would be positively related to MFT-B scores.

H5:α4>0 Higher scores in the writing learning goal assess-ment results would have a positive impact on demon-strating business disciplinary competence, and therefore would be positively related to MFT-B scores.

DATA AND ESTIMATION PROCEDURE

Data for this study came from a sample of 173 graduating seniors from an AACSB-accredited college of business. Ac-tual data used for the empirical estimations are less than the initial 173 because of missing observations for some variables. The data cover the period from 2007 to 2009. In particular, the MFT-B examination score—our dependent variable—was administered to the graduating seniors in the spring semester in the capstone course. Data for the inde-pendent variables were collected in the following way: GPAs were collected after the capstone business course was com-pleted. This is relevant because the capstone course has been flagged as the main course in which several learning goals are assessed, including business-specific analytical and over-all writing learning goals along with the oral communication goal.5The SATT score is the official entering score on which initial admission to the university was granted. We also used SATV and SATM scores to determine any possible differ-ential effects of each test component. Data for major came from the MFT-B results report, as indicated by the declared major in the examination, and thus a dual-major student was forced to select only one major. Writing and analytical data were collected from the assessment of the learning goals in the capstone senior project along several dimensions, as noted previously. These data cover 12 different categories grouped in two sections in which each item was assessed based on a 3-point Likert-type scale –ranging from 1 (fails to meet expectations) to 3 (exceeds expectations). The writing

106 G. A. BARBOZA AND J. PESEK

component corresponds to the summation of items 1 through 5, and items 6 through 12 correspond to the business-specific analytical skills component (see rubric in the Appendix for more details).

To better understand the significance of our analytical variable, it is relevant to note that analytical—an endogenous variable to the program—was constructed from the assess-ment of the senior project in the capstone business course. Analytical measured the degree of mastery that students achieved on business-specific concepts, the use of business analytical tools and their applications to discover business problems and issues, and the consequent construction of fea-sible business strategies. Therefore, analytical measured the development and accumulation of skills above and beyond those that a student could acquire outside the business cur-riculum. To be more specific, the senior project is a multistep process that makes extensive and intensive use of a strength, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT) analysis and correspondent Internal Factor Evaluation (IFE) and External Factor Evaluation (EFE) matrices6; utilizes several business-specific analytical tools such as the Boston Consulting Group (BCG), Internal-External (IE), SPACE, GRAND, and Quali-tative Strategic Planning Matrix (QSPM) matrices to identify problems and issues; and develops alternative strategies and consequently recommends feasible courses of action for a Fortune 500 company.

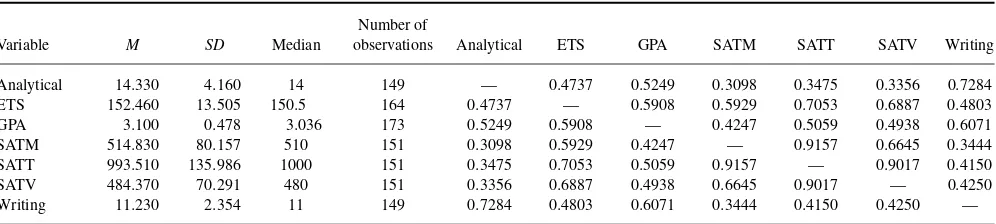

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics for selected vari-ables, including corresponding correlations. It is interest-ing to note that the MFT-B and SAT scores are leptokurtic, whereas the GPA scores are platykurtic. This is to say that the MFT-B and SAT scores were highly concentrated around the mean, with lower variation within the observations, whereas GPA scores were more widely spread than normal and were flatter around the mean, indicating a more wide variation across students. In addition, the data indicate that students in the sample had an average GPA of 3.099 on a 4-point scale or (letter grade of B), with all students meeting the school’s major requirements of a C average or better. In addition, the analytical and writing assessment scores indicate that stu-dents met or exceeded the assessment target as established in the assessment plan. However, average scores on these

categories indicate the existence of room for improvement in terms of achieving higher scores on average. Although the majority of the students (54%) in the school of business were men, for this sample 52% were women.

FINDINGS

We performed several estimations of alternative model spec-ifications of Equation 2 using a log-log transformation. The log-log transformation allowed us to account for differ-ences in units of measure and scales of several variables. Thus, this transformation facilitates interpretation of the re-sults. In addition, because our data were cross-sectional in nature, we used ordinary least squares (OLS) with White heteroscedasticity-consistent standard errors and covariance. The estimated coefficients are interpreted as elasticities.

With these basic considerations in mind, Table 2 shows results for all alternative models with Log (MFT-B) as the dependent variable. We estimated a total of 9 models. Our baseline models (1, 4, and 7) included GPA and SATT. We then teased out the data by conducting estimations (models 2, 3, 5, 6, 8, and 9) with the decomposition of SAT between verbal (SATV) and quantitative (SATM) to separate the spe-cific effects of each SAT component on business disciplinary competence. We then introduced our course-embedded vari-ables and conducted joint and separate estimations with the analytical and writing variables to determine their joint and individual effects on business disciplinary competence and determine whether multicollinearity between these two as-sessment course-embedded measures was present. In partic-ular, we had a strong interest to determine if the observed high correlation between analytical and writing (0.7284 in Table 1) translated into possible model misspecification. All estimations controlled for demographic effects as captured by differences in major and gender. This is to say that our course-embedded measures captured effects above and be-yond those reported for the conventional determinants of ETS MFT-B performance, as outlined in the literature.

Based on our estimations, there are several results worth noting: first, the positive and significant effects that the GPA

TABLE 1

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations for Selected Variables

Variable M SD Median

Number of

observations Analytical ETS GPA SATM SATT SATV Writing

Analytical 14.330 4.160 14 149 — 0.4737 0.5249 0.3098 0.3475 0.3356 0.7284

ETS 152.460 13.505 150.5 164 0.4737 — 0.5908 0.5929 0.7053 0.6887 0.4803

GPA 3.100 0.478 3.036 173 0.5249 0.5908 — 0.4247 0.5059 0.4938 0.6071

SATM 514.830 80.157 510 151 0.3098 0.5929 0.4247 — 0.9157 0.6645 0.3444

SATT 993.510 135.986 1000 151 0.3475 0.7053 0.5059 0.9157 — 0.9017 0.4150

SATV 484.370 70.291 480 151 0.3356 0.6887 0.4938 0.6645 0.9017 — 0.4250

Writing 11.230 2.354 11 149 0.7284 0.4803 0.6071 0.3444 0.4150 0.4250 —

Note.ETS=Educational Testing Service; GPA=grade point average; SATM=SAT mathematics test; SATV=SAT verbal test.

TABLE 2

Log-Log Assessment Estimation Models With the ETS MFT-B

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

Variable SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE SE

Constant 2.959∗∗ 0.348 3.330∗∗ 0.293 3.609∗∗ 0.248 2.964∗∗ 0.353 3.332∗∗ 0.296 3.609∗∗ 0.245 2.984∗∗ 0.359 3.355∗∗ 0.307 3.619∗∗ 0.255

Log (GPA) 0.1415∗∗ 0.046 0.154∗∗ 0.045 0.176∗∗ 0.048 0.139∗∗ 0.043 0.150∗∗ 0.043 0.179∗∗ 0.046 0.150∗∗ 0.048 0.164∗∗ 0.048 0.183∗∗ 0.049

Log (SATT) 0.265∗∗ 0.053 0.263∗∗ 0.054 0.262∗∗ 0.054

Log (SATV) 0.235∗∗ 0.052 0.232∗∗ 0.052 0.231∗∗ 0.054

Log (SATM) 0.178∗∗ 0.042 0.179∗∗ 0.042 0.177∗∗ 0.043

Management –0.028 0.018 −0.034∗ 0.017 –0.029 0.019 –0.028 0.017 –0.034∗ 0.017 –0.028 0.019 –0.028 0.018 –0.034∗ 0.017 –0.029 0.019 Finance 0.004 0.014 0.002 0.015 0.006 0.016 0.004 0.014 0.002 0.015 0.006 0.016 0.002 0.014 –0.001 0.014 0.004 0.016 Marketing –0.048∗∗ 0.013 –0.052∗∗ 0.013 –0.049∗∗ 0.014 –0.048∗∗ 0.013 –0.053∗∗ 0.013 –0.049∗∗ 0.014 –0.052∗∗ 0.013 –0.057∗∗ 0.013 –0.053∗∗ 0.014

Economics 0.033 0.027 –0.029 0.026 –0.031 0.029 –0.033 0.026 –0.029 0.026 –0.032 0.029 –0.034 0.027 –0.029 0.026 –0.032 0.030

Log (Writing) –0.009 0.041 –0.013 0.041 0.010 0.039 0.035 0.034 0.033 0.034 0.049 0.031

Log (Analytical) 0.046∗ 0.022 0.047∗ 0.023 0.041 0.024 0.042∗ 0.018 0.042∗ 0.019 0.045∗ 0.019

M 0.005 0.010 0.013 0.011 0.005 0.011 0.006 0.010 0.014 0.010 0.005 0.011 0.006 0.010 0.014 0.011 0.006 0.01

F 21.75∗∗ 21.37∗∗ 17.22∗∗ 24.65∗∗ 24.21∗∗ 19.52∗∗ 23.49∗∗ 23.02∗∗ 18.79∗∗

R2 0.628 0.624 0.572 0.628 0.623 0.572 0.616 0.611 0.562

Note. nobservations=126. ETS MFT-B=Educational Testing Service Major Field Test for Business; GPA=grade point average; SATT=total SAT test score; SATV=SAT verbal test score; SATM

=SAT mathematics test score.

∗p=.05.∗∗p=.01.

107

108 G. A. BARBOZA AND J. PESEK

and SAT had on MFT-B performance confirm what previous researchers have also found.7In particular, our estimations expand the present body of empirical evidence in the field by demonstrating that the verbal section of the SAT examination (SATV) had a larger impact on determining MFT-B perfor-mance than the corresponding quantitative section (SATM) did. In all our estimations SATV had an estimated elasticity of 0.26 versus a corresponding estimated elasticity of 0.17 for SATM. The coefficient for GPA ranged from 0.139 to 0.183 in the alternative models, and was the second most important determinant of overall performance in the MFT-B. Also, theR2value was higher when we controlled for SATT. In relation to differences across majors, we used the ac-counting variable as the reference group (omitted variable). The coefficient for differences across majors was negative and statistically significant for management majors when we used SATV, but not when SATT or SATM were used. It ap-pears that management majors performed significantly lower than their accounting peers in the SATM,and these differ-ences persisted across the curriculum. Marketing majors, on the other hand, consistently performed at the lowest level even after controlling for predetermined abilities on SAT scores and GPA. This result is also a partial confirmation of findings in previous research, as noted previously in the literature review, but expands on the finding that marketing majors’ lower performance accentuates during the business program (i.e., marketing majors lag behind in relation to their peers even after controlling for ex-ante differences in SAT scores). There was no statistically significant difference be-tween finance and economics majors with accounting majors in any of the models.

As expected, there existed a high correlation between the writing and analytical variables. In general, we observed that a well-written paper tends to convey and receive high marks for business-specific analytical thinking. However, this cor-relation does not imply causation. Rather, the positive sign of the analytical coefficient should be interpreted as a true and direct effect on increased business disciplinary compe-tence, deriving solely from program-specific acquired ana-lytical skills, and not from writing skills. This is a partic-ularly relevant result because it provides direct evidence of program-specific value-added components for business disci-plinary competence achievement, and serves as an indication of positive effects of AoL efforts. Finally, the results for the gender effects indicate that there was no statistically signif-icant difference between performance of women and men. We can safely argue that the ETS MFT-B is a test that does not favor one gender over the other.

To further explore the sources of variation on MFT-B per-formance, we conducted some sensitivity analysis. As noted previously, although SAT and GPA show some degree of correlation (and it is well documented in the literature that high SAT scores are more likely to result in higher GPA scores), they serve different functions in measuring business disciplinary competence. This is because both variables are

statistically significant at the 1% level of confidence. More relevantly, the business-specific analytical measure had ex-planatory power above and beyond what was depicted by GPA performance. In this regard, if the analytical score were to increase by 1% (0.03 points) the business disciplinary competence score would increase by 0.04 points.

Further exploration of the relationship between SAT and GPA on overall business competency reveals that the separa-tion of SAT scores between the SATV and SATM variables was relevant (see models 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, and 8). First, we discov-ered that SATV had a larger impact on MFT-B performance in relation to SATM. This difference is robust to whether we included analytical and writing concurrently or separately. Second, the major variable for marketing was consistently negative and significant, indicating a relatively lower perfor-mance in relation to the peers. For management majors, the negative relationship was statistically significant only when we used SATV as the control variable. Furthermore, our as-sessment measure for business-specific analytical skills was statistically significant in all models but model 3.8In addi-tion, writing was not statistically significant in any model, neither when included concurrently with analytical nor sepa-rately. We argue that writing skill effects are already captured in the SATT (and in particular STAV) and GPA variables.

Our results yield the preliminary conclusions that SAT scores (SATT and SATV) are the most relevant individ-ual determinants of MFT-B performance. GPA and SATM have an almost identical overall effect on overall business competency performance. In principle, schools with higher SAT standards should achieve higher MFT-B scores, all other things being equal. In fact, these differences tend to be larger the higher the SAT scores. However, this should not be taken as a sufficient condition for higher performance in MFT-B alone, as the initial effects of SAT diminish in importance as students advance in their studies, and other variables such as GPA and development of business-specific analytical skills become more relevant. In this regard, GPA is the second most important determinant of MFT-B scores, and all other things being equal, the more students apply themselves in the learn-ing process the greater the likelihood that they will score higher in the exogenous measure of business disciplinary competence, ETS MFT-B. Thus, high GPA performance may offset possible initial disadvantages that schools with lower SAT admission standards may have.

However, although we do not dispute the fact that SAT scores are a relevant measure of general abilities, our empir-ical estimates indicate that business-specific analytempir-ical skills are internally developed in the business program and serve to enhance the MFT-B performance of the students, above and beyond those capabilities capture by the SAT and GPA scores. Thus, the robustness of the business-specific analyti-cal assessment measure as a significant determinant of MFT-B performance is an indication of two things. First, efforts to develop business-specific analytical skills are a true mea-sure of value added, as they relate to increasing business

LINKING COURSE-EMBEDDED ASSESSMENT MEASURES 109

disciplinary competence; second, although analytical and writing are correlated, our analytical variable is clearly en-dogenous to the program and a reinforcement to AoL prac-tices as mechanisms to demonstrate business competence. That is to say, although there might be room for improved business disciplinary competence through better writing, these skills develop in large part ex-ante to students entering the business curriculum. The evidence extends the argument to indicate that this appears to be the case across all busi-ness majors. In terms of policy recommendations it is worth noting that business programs have a larger control over the analytical component of the program and its positive effects on achieving higher levels of business disciplinary compe-tence than other components. This is a clear indication of the robust effect that the business-specific analytical assessment variable has as a value-added measure for demonstrating business disciplinary competence. This in fact is the primary finding of this study. Although we acknowledge that there may be an alternative explanation in this regard, namely that the students may have acquired more general analyti-cal skills prior to entering the business program—or from a third source while in the program—this explanation does not diminish the importance of our findings because our an-alytical variable is business-specific and endogenous to the program curriculum. In addition, SAT scores capture some of the writing and more general analytical abilities that are time and program invariant. Finally, differences across majors in-dicate that some attention needs to be paid at the program level to bring the performance of marketing and management majors to the level of the reference group.

Put simply, students that apply themselves and success-fully achieve higher GPAs and develop strong business-specific analytical skills could potentially catch up with those students that initially had a SAT advantage. It follows that this improvement is highly correlated with the complete-ness, complexity, and overall thoroughness of the business curriculum because achieving a higher GPA in a more rigor-ous program is more difficult than otherwise. In this regard, placing an emphasis in learning activities that emphasize ac-quisition, development, and use of business-specific analyt-ical skills play a determinant role in achieving higher levels of business disciplinary competence, as our results elucidate through the positive effects on MFT-B scores.

Incidentally, our business-specific analytical assessment variable measured abilities that students had acquired during their academic program in terms of conceptualization, identi-fication, application, recommendation, and building of over-all business strategies for effective decision making, which are directly related to a comprehensive business disciplinary competence. Assessment of this particular variable plays a fundamental role in achieving the preset learning goals for the program. The most relevant and immediate result is that our endogenous (program and business-specific) measure of analytical skills is also a good predictor of overall business disciplinary competence. Thus, program value added builds

on pre-existent capabilities (SAT scores), and serves as a measure of the program effectiveness to overcome any pos-sible selectivity bias that could affect less stringent, yet rigor-ous, admission procedures—a result not found in the existent literature.

Our results push the knowledge envelope on assessment-related issues on two major fronts. First, continuous as-sessment of learning goals at the program level proves valuable in identifying, establishing, measuring, and guid-ing strategies conducive to increasguid-ing business competence through course-embedded assessment. Second, although stu-dents may also develop and hone their analytical and critical thinking skills in nonbusiness courses, in the present we study made use of program-specific value-added measures in the form of business-specific analytical skills development to as-sess and quantify their effect on business competence, while controlling for conventional ability measures (GPA and SAT) and other demographics.

RECOMMENDATIONS AND CONCLUSIONS

There are several relevant recommendations that spring from our analysis. In particular, our results point out the possible changes in curriculum and target levels for assessment in the core areas of the business program to continue improving business disciplinary competence achievement.

In terms of the program recommendations, it is interest-ing to notice the convergence of two effects. First, students achieving high marks (meet or exceed expectations) in the business-specific analytical component of their senior project performed better in the MFT-B than otherwise. This is a re-sult in support of a continuous assessment effort to foster excellence in teaching and learning. Also, program efforts directed to not only meet accreditation requirements and tar-get levels, but aimed at boosting business-specific analytical scores above the target, or that result in overall increased targets, should also yield higher business disciplinary com-petence as measured by MFT-B scoring. On the same note, adding more projects with a strong business-specific ana-lytical content across the business curriculum should have the same positive impact on achieving higher scores on the external measure of business disciplinary competence. How-ever, notice that achieving a higher MFT-B score is not a learning goal in itself, but the result of a program learn-ing goal and objective, which is achievlearn-ing and successfully completing a comprehensive business competence that de-rives in a significant amount of program value added. In this regard, developing a simpler version of the business-specific analytical skills rubric—presently used at the senior level only—with the intention to assess business-specific knowl-edge upon admission to the business program could prove useful to develop a true valued-added measure of business analytical skills. This however, is beyond the scope of the present study.

110 G. A. BARBOZA AND J. PESEK

The exploratory results of this study also point out to the direction that assessment of the business curriculum provides valuable information on achieving and meeting the learning goals and corresponding objectives. Promoting practices that raise the overall assessment results should positively affect the overall learning process. More specifically, promoting practices that result in increased GPA and higher business-specific Analytical scores could prove beneficial and a signif-icant determinant for improvement in business disciplinary competence. These effects indicate that students excelling in the classroom gain knowledge and develop their intellect beyond the native abilities as reflected by the SAT scores.

The results also indicate that there are persistent differ-ences across business majors, with accounting, finance, and economics majors outperforming the rest. In this regard, two questions remain unanswered and are possible outlets for further research. First, are the observed differences across majors correlated to the SAT scores? Or, more importantly, are there program-specific differences in the business cur-riculum across majors that result in overall differentiated learning outcomes that are major specific? Previous research provides some insight to this question, but a closer examina-tion of the curriculum across majors may prove beneficial. A third less likely yet possible explanation relates to the MFT-B construct and whether the examination design provides more opportunities for accounting and finance majors to do well, compared with other business majors, as noted by No¨el et al. (2003). These questions are outside the scope of this article. Finally, we summarize results from our study as the fol-lowing: Assessment of the business curriculum proves to be a valuable tool to assure a comprehensive and mission-oriented learning process. Clear and direct program- and mission-oriented learning goals and objectives that are comprehen-sive and use consistent rubrics with well-established targets are valuable in measuring business disciplinary competence. These positive effects of course-embedded assessments pro-vide robust epro-vidence that a continuous monitoring of the academic progress results in improved performance and ef-fective and efficient use of resources to enhance the overall learning experience along the established mission statement.

NOTES

1. According to the ETS (2011) website, the ETS MFT-B “contains 120 multiple-choice questions designed to measure a student’s subject knowledge and the ability to apply facts, concepts, theories and analytical meth-ods. .. The questions represent a wide range of diffi-culty and cover depth and breadth in assessing students’ achievement levels.”

2. Previous research indicates that SAT scores are relevant overall performance indicators for lower levels courses—freshman- and sophomore-level classes—whereas GPA becomes a more rel-evant performance determinants for higher level

courses—junior- and senior-level courses. Neverthe-less, we incorporated SAT scores because the MFT-B performance could potentially be exogenously deter-mined, beyond actual learning taking place in the busi-ness curricula.

3. The seven dimensions were factual knowledge, ap-plication of strategic analytical tools, identification of case problems and issues, application of case problems and issues, generation of alternatives, recommenda-tions, and business knowledge.

4. Writing dimensions were thesis or opening statement, organization, spelling and word choice, grammar, and sentence structure.

5. Oral communication scores were not used in this study. 6. The construction of the IFE and EFE matrices relies heavily on the use and mastery of the Resource Based View and the Porter’s Five Forces analysis, respec-tively.

7. Bycio and Allen (2007) noted that the positive effect of SAT on MFT-B results could be an indication of general test-taking ability. Furthermore, they noted that schools with strong SAT profiles have stronger performance in comparison with schools with less stringent admission requirements.

8. The analytical variable was marginally significant at 8% in this model. The reduction is significance could be a consequence of sample size. Notice that the coef-ficient magnitude and sign is robust across models.

REFERENCES

Allen, J. S., & Bycio, P. (1997). An evaluation of the Educational Testing Service Major Field Achievement Test in Business.Journal of Accounting Education,15, 503–514.

Bycio, P., & Allen, J. S. (2007). Factors associated with performance on the Educational Testing Service (ETS) Major Field Achievement Test in Business (MFAT-B).Journal of Education for Business,82, 196–201. Bush, H. F., Duncan, F. H., Sexton, E. A., & West, C. T. (2008). Using the

Major Field Test-Business as an assessment tool and impetus for program improvement: Fifteen years of experience at Virginia Military Institute. Journal of College Teaching and Learning,5, 75–88.

Educational Testing Service. (2011).Major Field Test in Business. Retrieved from http://ets.org/mft/about/content/bachelor business

Gerlich, R. N., & Sollosy, M. (2008). Predicting assessment outcomes: The effect of full-time and part-time faculty.Journal of Case Studies in Accreditation and Assessment,1, 1–9.

Marshall, L. L. (2007). Measuring assurance of learning at the degree pro-gram and academic major levels.Journal of Education for Business,83, 101–109.

Martell, K. (2007). Assessing student learning: Are business schools making the grade?Journal of Education for Business,82, 189–195.

No¨el, N. M., Michaels, C., & Levas, M. G. (2003). The relationship of per-sonality traits and self-monitoring behavior to choice of business major. Journal of Education for Business,78, 153–157.

Terry, N., Mills, L., & Sollosy, M. (2008). Student grade motivation as a determinant of performance on the Business Major Field ETS Exam. Journal of College Teaching & Learning,5(7), 27–32.

Ulrich, T. A. (2005). The relationship of business major to pedagogical strategies.Journal of Education for Business,80, 269–274.

LINKING COURSE-EMBEDDED ASSESSMENT MEASURES 111

APPENDIX—EFFECTIVE WRITTEN COMMUNICATION RUBRIC

Draft—Scoring Rubric (Developed by Monique Forte, Stetson University) Strategy Case Analysis to Assess Written Communication and Analytical Thinking Skills

Evaluative criteria Fails to meet expectations (1) Meets expectations (3) Exceeds expectations (5)

Written communication

1. Thesis/opening statement Offers a weak or unfocused thesis statement

Opens with a clear statement of case problems/issues

Hooks reader with clever/insightful opener to clearly identify case issues

2. Organization Uses few headings or paragraph breaks; shows weak logical flow

Provides organized analysis that generally maintains focus

Provides clear organization scheme to guide reader through logic of analysis

3. Spelling & word choice Uses many misspelled words and shows only elementary vocabulary level

Has spellchecked, but may miss a typo or use an inappropriate word/term

Uses correct spelling throughout and demonstrates strong vocabulary skills

4. Grammar Commits several grammatical errors that detract from the paper’s readability

Generally uses correct verbs, tenses, pronouns, etc., with 1–2 minor errors

Shows correct grammar throughout; offers varied sentences for good style

5. Sentence structure Offers multiple sentence fragments, run-ons, comma splices, or agreement errors

Generally uses good sentence structure, with 1–2 minor errors

Uses good sentence structure throughout; offers varied sentences for good style

Analytical thinking

6. Factual knowledge Shows little knowledge of case facts, makes factual mistakes

Shows solid understanding of case facts

Shows thorough grasp of case facts and offers additional factual knowledge about company or industry

7. Application of strategic analytical tools

Misuses industry analysis models or misconstrues SWOT elements

Appropriately applies competitive forces, driving forces and SWOT analyses

Neglects to identify case issues; recounts facts of case with little analysis

Clearly identifies the key issues in the case and demonstrates

understanding of company’s decision situation

Develops a well-integrated statement of the complex issues of the case and demonstrates understanding of

Clearly relates case problem/issue to factual information and strategic analytic tools

Extends discussion of case problem/issue to secondary related issues with supportive diagnosis

10. Generation of alternatives Identifies weak or infeasible alternatives with little attention to addressing case issues

Generates 2–3 feasible alternatives for resolving the key issues of the case

Develops 2–3 insightful alternatives for resolving the issues, offers specificity and originality 11. Recommendations Offers weak recommendations or

pays little attention to addressing case issues

Provides well-reasoned

recommendations that flow from the preceding analyses and clearly 12. Business judgment Shows little attention to presenting

sound arguments or backing up ideas with analysis; offers “I think” statements

Provides good arguments backed up with factual knowledge, analysis