Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:44

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

A Study of Organizational Identification of Faculty

Members in Hong Kong Business Schools

Po Yung Tsui & Hang-Yue Ngo

To cite this article: Po Yung Tsui & Hang-Yue Ngo (2015) A Study of Organizational

Identification of Faculty Members in Hong Kong Business Schools, Journal of Education for Business, 90:8, 427-434, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1087372

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1087372

Published online: 14 Oct 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 22

View related articles

A Study of Organizational Identification of Faculty

Members in Hong Kong Business Schools

Po Yung Tsui and Hang-Yue Ngo

Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong

The authors examine how four organizational antecedents affect the organizational identification (OI) and in-role and extra-role performance of Hong Kong business school faculty. OI was tested to be a mediator. The survey results indicated a high level of OI, consistent with the collectivist cultural value of Chinese employees. However, OI was positively associated with two antecedents only. And contrary to the existing literature that OI only affects extra-role behavior, OI was positively associated with both consequences. The data did not support OI as a mediator. Further research in the Chinese context and extension of studies with additional variables are recommended.

Keywords: business school, business school rankings, faculty, organizational identification, university rankings

Defined as “the perceived oneness with an organization and the experience of the organization’s success and failure as one’s own” (Mael & Ashforth, 1992, p. 104), organizational identification (OI) has attracted considerable management research interest (Ashforth, Harrison, & Corley, 2008; Edwards, 2005; Riketta, 2005). OI is positively associated with many types of employee behavior (Ashforth et al., 2008; Edwards, 2005). Given the phenomenon of eroding employee loyalty due to organizational changes, attention to OI effects is thus important.

Despite the rich OI literature, this study intends to fill a few existing research gaps. First, we examine the concept of OI, which is rarely found in higher education institution (HEI) literature. Globalization has led to reforms of HEIs, which often compete through university ranking systems. Criticism of this competitive process, however, is ubiqui-tous (Marginson, 2007; O’Connell, 2013). Nevertheless, stakeholders are tempted to judge HEIs using these systems (Kreutzer & Wood, 2007). Competition among business schools is intense (Corley & Gioia, 2000, 2002), and favor-able rankings provide numerous advantages to business schools. High rankings have strong positive correlations with program fees (Peters, 2007), salaries commanded by

graduates (Kreutzer & Wood, 2007), and faculty percep-tions (Elsbach & Kramer, 1996).

In Hong Kong, a culture of competition has also emerged among its business schools (So, 2013). They compete based on a variety of performance indicators, including their inter-national rankings (Hou, Fan, & Liu, 2014; Mudambi, Peng, & Weng, 2008). Different business schools may cite diverse sources of information to reflect their favorable status. It is clear that they actively pursue success in the ranking game. However, competition has created intense frustration, as well as changing roles and identities among faculty (Winter, 2009). In Asia, faculty must take on increasingly workloads and experience a substantial reduction in decision-making power (Mok & Nelson, 2013). Therefore, it is critically important to elucidate business school faculty’s OI, which is likely to be affected by the above factors.

Second, it is unfortunate that most existing OI research has been conducted in the West. But many aspects of Asian cultures differ from those of the West (Hofstede, 2001). The concept of OI and its underlying social identity theory is particularly relevant to the Chinese setting, as Chinese people are typically more collectivist, and would thus iden-tify more strongly with their organizations. Although a few OI studies have been performed in Asia, most have taken place in industrial settings (Liu, Loi & Lam, 2011; Ngo, Loi, Foley, Zheng, & Zhang, 2013; Tso, 2005). Moreover, current literature about Asian higher education only pro-vides general descriptions of education reforms or univer-sity rankings (Deem, Mok & Lucas, 2008; Mok & Nelson, Correspondence should be addressed to Po Yung Tsui, Chinese

Univer-sity of Hong Kong, Department of Management, Room 833, Cheng Yu Tung Building, 12 Chak Cheung Street, Shatin, New Territories, Hong Kong. E-mail: [email protected]

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1087372

2013). To the best of our knowledge, no study has yet examined the identification of Chinese academics with their institutions. This study, possibly the first one in Asia, attempts to fill this void using the quantitative method.

Third, while most research has examined OI either as a predictor or an outcome variable, this construct may be considered as a mediator (Olkkonen & Lipponnen, 2006). In fact, the relationships of OI with other constructs, antece-dents, and consequences are frequently confusing in the extant literature (Meyer & Allen, 1997; O’Reilly & Chapman, 1986). In the limited number of studies con-ducted in Chinese settings, the research findings are ambig-uous as well (Liu et al., 2011; Tso, 2005). Furthermore, current theories mainly describe the conditions under which people identify with an organization, but do not identify the reasons why they do so (Pratt, 1998).

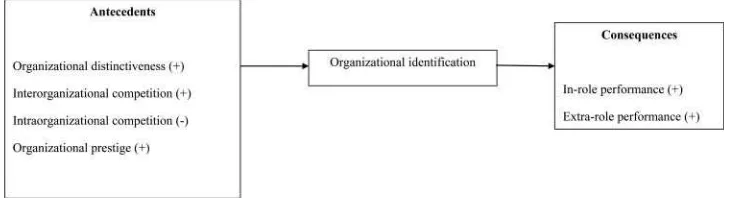

Accordingly, the objective of this study is to address the above research gaps with the following model (Figure 1). Hong Kong is selected because (a) it is widely considered to be Asia’s world city and has been recognized as the world’s freest economy for many years (Heritage Foundation, 2015); (b) it is a melting pot of Eastern and Western cultures, which provides a unique opportunity to understand how its universities are affected by international rankings; and (c) Hong Kong is promoted as a regional hub of higher education (Mok & Nelson, 2013). Therefore, the findings would be instruc-tive to other Asian or Chinese HEIs.

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND AND HYPOTHESES

OI is a form of social identification that constructs identities in terms of memberships and affiliations with organizations (Ashforth & Mael, 1989; Riketta, 2005). Studies of OI mainly utilize the insights of social identity theory (SIT) and self-categorization theory (SCT). According to SIT, an individual’s self-concept consists of both a personal iden-tity and a social ideniden-tity. A social ideniden-tity is “part of an individual’s self-concept which derives from his knowledge of his membership in a social group (or groups) together with the value and emotional significance attached to that membership” (Tajfel, 1978, p. 63). The more the individual identifies with an organization, the more likely he or she is

to take the organization’s perspective as self-defining and act in the organization’s best interest (van Knippenberg & van Schie, 2000).

SCT was developed to compensate for the inadequacies of the SIT. It argues that the categorization of the self and social groups can occur at various levels of abstraction trig-gered by social cues of two kinds (i.e., the salience of inter-group boundaries as well as maximization of within-inter-group similarity and between-group difference; Hogg, 1996). Based on these two theories, researchers hypothesize that clear and distinct differences between groups, and a high salience for organizational categories in an attractive group can enhance identification with a particular social group (Pratt, 1998).

Organizational Identification and its Antecedents

Existing literature suggests that individuals’ perception of their organization as distinctive and prestigious constitute key criteria for OI (Ashforth & Mael, 1989, 1992). Per-ceived organizational distinctiveness taps into individuals’ need to be unique and does so through membership in a dis-tinctive group. When an organization becomes “infused with value” (Selznick, 1957), its distinctiveness generates strong loyalty from members. It also differentiates an orga-nization from others, and strong levels of OI are found. We predicted a positive relationship between OI and organiza-tional distinctiveness.

Perceived organizational prestige indicates the “degree to which the institution is well regarded both in absolute and comparative terms” (Mael & Ashforth, 1992, p. 107) that aligns individuals and organizational identities through a focus on self, since individuals identify with organizations partly to enhance their own self-esteem. The more presti-gious the organization, the greater the potential for raising self-esteem through identification with the organization. As a result, members’ perception of their business school’s prestige (through their business school’s international rank-ings in this study) was expected to be positively related to their OI strength.

For perceived interorganizational competition, existence of outgroups facilitates individuals to differentiate their ingroups from outgroups, and causes them to assume ingroup homogeneity (Brown & Ross, 1982). This in-group

FIGURE 1. Proposed model of organizational identification.

428 P. Y. TSUI AND H-Y. NGO

homogeneity makes it easier for them to identify with the organization. A positive relationship between interorgani-zational competition and members’ OI was thus hypothesized.

Finally, perceived intraorganizational competition was hypothesized to be negatively related to OI. Increasing internal competition would weaken the homogeneity of organizational members. A negative relationship between intraorganizational competition and members’ OI was hypothesized.

Organizational Identification and its Consequences

Riketta (2005) demonstrates high correlations between OI and in-role and extra-role performance. As in-role permance belongs to work behaviors that are prescribed by for-mal job roles as assigned by organizations (Williams & Anderson, 1991), it should play a crucial role in the OI pro-cess. Thus, members with a high level of OI would expend greater efforts in their in-role performance.

Extra-role behavior is the “behavior that attempts to ben-efit the organization and that goes beyond existing role expectations” (Organ, Podsakoff, & MacKenzie, 2006, p. 33). Despite ambiguous findings, it is contended that members employ extra-role behavior as a strategy to con-firm their organizational identity (Swann, 1987). Therefore, people possessing high levels of OI tend to engage in more extra-role performance.

Finally, as shown in Figure 1, OI may act as a mediator. For example, when members perceive organizational dis-tinctiveness in a positive light, they tend to develop a strong identification with their organization, which in turn results in positive role behaviors.

The preceding discussion results in the following hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1(H1):OI of Hong Kong business school fac-ulty would positively related to perceived organiza-tional distinctiveness, perceived interorganizaorganiza-tional competition, and perceived organizational prestige, and would be negatively related to perceived intraorga-nizational competition.

H2: OI of Hong Kong business school faculty would be posi-tively related to their in-role and extra-role performance.

H3: OI of Hong Kong business school faculty would mediate the relationship between in-role and extra-role performance, and perceived organizational distinc-tiveness, interorganizational competition, intraorganiza-tional competition, and organizaintraorganiza-tional prestige.

METHODS

The unit of analysis for this study was business school fac-ulty members in Hong Kong. A survey was conducted

between August and October 2012. A total of 1,162 faculty (including full-time, part-time, and adjunct faculty on both research and teaching tracks) were invited from 11 Hong Kong universities. Altogether, 194 completed valid ques-tionnaires were received. The quesques-tionnaires were devel-oped using well-established scales from existing literature. Unless otherwise stated, all responses were given on a 5-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree).

For OI and its antecedents, existing measures developed by Mael and Ashforth (1992) were utilized. Regarding organizational identification, a 6-item scale was adopted, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .871. Perceived organizational distinctiveness, measured by a 4-item scale, had a Cronbach’s alpha of .799. The Cronbach’s alpha of per-ceived interorganizational competition’s 4-item scale was .710. Perceived intraorganizational competition had a 4-item scale with Cronbach’s alpha .639, which was a bit lower than desired. Perceived organizational prestige was assessed by another 4-item scale complemented with inter-national rankings, and its Cronbach’s alpha was .859.

Concerning the consequences, the in-role performance variable was from Williams and Anderson’s (1991) study, with a Cronbach’s alpha of .935. The extra-role perfor-mance was adapted from a scale in Somech and Drach-Zahavy (2000), and its Cronbach’s alpha was .806.

Six control variables were included: gender (coded 0 for male and 1 for female), highest education level (four cate-gories: 1, bachelor; 2, master; 3, doctoral or above degree; 4, others), year of service/tenure in current business school (four categories: 1, 0–5 years; 2, 6–10 years; 3, 10–20 years; 4, more than 20 years), job type (0, research track; 1, teaching track), employment status (0, tenured; 1, contract, part-time, or others), and university (coded from 1 to 11).

RESULTS

Table 1 presents the descriptive statistics. The respondents reported quite a high level of OI (x̄D3.384,SDD.76, on a

5-point scale). In other words, the local faculty did possess a fairly strong sense of belonging to their business schools. Interestingly, however, a negative correlation was found between years of service and OI. It was conjectured that faculty members in the early stage of their careers might be more likely to report a higher level of OI than those at a later career stage. On the other hand, faculty with longer service may become less identified with their organizations given the occurrence of various changes and educational reforms. As expected, OI was positively correlated with organizational distinctiveness, interorganizational competi-tion, and organizational prestige. However, contrary to the expectation, OI exhibited a positive correlation with intra-organizational competition. OI’s correlations with the two

consequences (i.e., in-role and extra-role performance) were significant and in predicted directions.

Business school faculty in different universities might possess different perceptions regarding antecedents, OI, and their work behaviors. Thus, a series of one-way analy-sis of variance (ANOVA) was conducted. Table 2 shows that respondents of various business schools reported ent levels of organizational antecedents. Significant differ-ences were found in interorganizational and intraorganizational competition, as well as organizational prestige, among different business schools. Especially, the organizational prestige variable possessed a large signifi-cantFratio,FD13.576 (dfD10, 180),p<.001, revealing significantly different perceptions of this variable among business school faculty members.

Table 3 presents the results of hierarchical regression anal-yses in order to elucidate the effects of different variables on OI, and in-role and extra-role performance. To test the medi-ating effect, the first condition set by Baron and Kenny (1986) required that the independent variable must predict the dependent variable. In our study, this means that the four ante-cedents should have a significant effect on two consequences. However, for in-role performance, Model 2 indicates that only interorganizational competition had a positive effect. Moreover, all four independent variables did not have any effect on extra-role performance (Model 5).

Nevertheless, the second condition of mediation was examined. The four antecedents should have significant effects on OI. Model 8 indicates that organizational distinc-tiveness and organizational prestige were indeed significant predictors of OI, but not interorganizational competition and intraorganizational competition. The second condition of mediation was partially fulfilled with effects from two antecedents (i.e., organizational distinctiveness and organi-zational prestige). Based on the previous results, H1 was partially confirmed only.

The third condition requires the mediator to affect the dependent variable. From Table 3, OI had a significant pos-itive effect on in-role and extra-role performance (Models 3 and 6). It thus affirmed the third condition of mediation.H2

was supported, as OI was positively related to both in-role and extra-role performance.

The last condition of mediation was assessed. After OI was entered into Model 3, the original coefficient of interor-ganizational competition on in-role performance did not reduce significantly. It changed slightly and remained sig-nificant, frombD.219 (p<.05) tobD.211 (p<.05).

Fur-thermore, Model 6 showed that the coefficients of the four antecedents remained insignificant. OI did not mediate the relationships between the four independent variables on the two outcomes. Thus,H3was not supported.

DISCUSSION

In this study we aimed to enrich the stream of OI research by investigating relationships among several organizational antecedents, OI, and the business school faculty’s work behavior under a Chinese higher education context. The findings, however, could fulfill limited expectations only. First, local business school faculty reported quite a high level of OI, consistent with the collectivist cultural value of Chinese employees. In addition, OI had positive correla-tions with all four antecedents and two consequences. A surprising finding came from its positive correlation with intraorganizational competition. Possible explanations for this are the following: (a) competition between business schools was so intense that there was a spillover effect from interorganizational competition to competition between faculty members in the same business school; (b) it could reflect that the inherent nature of business schools is com-petitive; and (c) it could be due to core elements of Chinese

TABLE 1

Descriptive Statistics and Correlations of Study Variables

Variable M SD 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1. Gender 0.300 0.458

2. Highest education level 2.850 0.369 ¡.120

3. Years of service 2.100 1.103 ¡.137 .116

4. Job type 0.280 0.448 .214**

¡.579** ¡.120

5. Employment status 0.630 0.487 .172*

¡.191** ¡.517** .361**

6. University 6.110 3.373 .027 .003 .121 ¡.116 ¡.020

7. Organizational identification 3.384 0.757 ¡.020 .047 ¡.149* ¡.036 ¡.044 ¡.090

8. Organizational distinctiveness 3.184 0.828 ¡.013 .016 ¡.068 ¡.042 ¡.010 ¡.104 .427**

9. Interorganizational competition 3.992 0.617 ¡.045 .018 ¡.055 .022 ¡.054 ¡.144* .185** .176*

10. Intraorganizational competition 3.084 0.666 ¡.064 .051 .047 ¡.114 ¡.065 ¡.108 .160* .214** .235**

11. Organizational prestige 2.829 0.974 ¡.045 ¡.004 ¡.094 ¡.010 ¡.104 ¡.436** .387** .462** .253** .403**

TABLE 2

Results of Analysis of Variance: Differences Among Universities on Various Variables

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

Variables/University M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD M SD Fratio df

Organizational distinctiveness 3.13 0.70 2.86 1.12 3.56 0.77 3.50 0.79 3.50 0.90 3.06 0.40 2.75 0.79 3.06 0.80 2.88 0.95 3.43 0.82 3.09 0.78 1.868 Interorganizational competition 4.29 0.54 4.21 0.39 4.09 0.65 3.90 0.61 3.70 0.54 3.53 0.80 3.40 0.42 3.95 0.64 3.99 0.51 3.83 0.72 4.10 0.55 2.310* Intraorganizational competition 3.29 0.71 3.14 0.79 3.22 0.65 2.88 0.61 3.22 0.49 2.31 0.55 2.50 0.53 3.17 0.59 3.13 0.62 2.98 0.62 2.96 0.77 2.307*

Organizational prestige 3.41 0.77 3.50 1.17 3.88 0.75 2.23 0.84 2.53 0.81 1.47 0.49 2.00 0.47 2.86 0.71 2.49 0.74 2.35 0.75 2.31 0.72 13.576*** 10, 180 Organizational identification 3.46 0.77 3.52 0.73 3.44 0.76 3.62 0.63 3.89 0.76 2.81 0.66 3.43 0.38 3.27 0.77 3.08 0.76 3.60 0.65 3.47 0.80 1.812

In-role performance 4.18 0.47 4.27 0.48 4.24 0.50 4.47 0.45 4.29 0.38 4.19 0.40 3.83 0.23 4.13 0.73 4.29 0.46 4.40 0.65 4.34 0.46 0.941 Extra-role performance 3.84 0.53 3.71 0.26 3.62 0.42 3.91 0.42 3.94 0.47 3.28 0.79 3.67 0.28 3.62 0.46 3.51 0.62 3.75 0.49 3.86 0.57 1.877

Note. nD194.

*p<.05 (two-tailed).

**p<.01 (two-tailed).

culture, particularly Confucianism. Specifically, Confucian ideology places a heavy emphasis on education, hard work, and competitiveness. However, it simultaneously encour-ages harmony between people (Yao & Tu, 2011). These contradictory forces motivate people to strive for high work goals while achieving harmony with each other without demonstrating strong overt competition. A positive correla-tion between intraorganizacorrela-tional competicorrela-tion and OI was thus noted.

The second observation was that perceived organiza-tional distinctiveness and organizaorganiza-tional prestige engen-dered direct effects on OI; whereas, there were no significant relationships between OI and interorganizational as well as intraorganizational competition. This partially supported ourH1. In other words, distinctiveness and pres-tige of a business school constituted the main factors driv-ing faculty’s OI. Especially, perceived organizational prestige was critically important, which is consistent with the findings of Western studies. Rankings identify a busi-ness school as an elite provider of educational services, and stakeholders would attempt to ascribe quality and status to themselves through affiliation (Elsbach & Kramer, 1996). This study provides important evidence to Asian HEIs, demonstrating that in order to obtain strong attachment from current and potential members, Hong Kong (or other Chinese or Asian) business schools must engage in interna-tional ranking exercises, despite the existing controversy.

However, in contrast to the results of Western studies that showed that increased interorganizational competition or reduction of intraorganizational competition would increase members’ OI, our investigation found that these factors did not induce stronger OI. In other words, competi-tion, in the form of outgroups versus ingroups, or internal

subgroups, did not result in increased OI. Two reasons may explain the nonsignificant effect of interorganizational competition on OI. First, it may again be due to the Confu-cian nature of Chinese culture. Members in a ConfuConfu-cian society, who typically strive for harmony and respect, did not seek strong interorganizational competition as a basis of organizational identification. Thus, if business schools focused on competition, it would not prompt categorization processes regarding membership. Second, members might perceive competitive threats between business schools as causing their organizations to engage in harmful behavior. Business schools pursuing competitive actions would be perceived as deviating substantially from educational ideals that encompass typically positive values, such as equality, justice, and truth. Thus, members might dissociate them-selves from their business schools. Regarding the nonsig-nificant effect of intraorganizational competition on OI, it could be argued that OI derives from a collective identity. However, the pursuit of intraorganizational competition and rewards would drive one toward an individual identity, contrary to the Chinese collectivist culture.

Third, we found that OI was positively associated with both consequences, andH2was thus confirmed. This study, how-ever, refuted the findings of some Western studies that showed that OI affects extra-role behavior but not in-role performance (O’Reilly & Chatman, 1986). While the faculty exerted great efforts to complete their normal duties, they also identified their membership in the organizations positively and were willing to perform tasks outside of their scope.

Finally, OI was not found to be a mediator. Thus,H3of the proposed model could not be proved. This does not mean that OI is not a mediator in the Chinese context. Rather, it indicates that the model could not be replicated in

TABLE 3

Dimensions of Regression Results on In-Role Performance, Extra-Role Performance, and Organizational Identification

In-role performance Extra-role performance Organizational identification Variable Model 1 Model 2 Model 3 Model 4 Model 5 Model 6 Model 7 Model 8 Gender .019 .021 .025 ¡.126 ¡.114 ¡.115 ¡.010 ¡.005

Highest education level ¡.025 ¡.027 ¡.043 ¡.098 ¡.090 ¡.115 .058 .071

Years of service .015 .046 .081 ¡.170 ¡.142 ¡.089 ¡.221* ¡.167*

Job type .006 ¡.014 ¡.024 .016 .032 .013 .040 .053

Employment status ¡.122 ¡.088 ¡.072 ¡.149 ¡.120 ¡.092 ¡.155 ¡.094

University .057 .108 .093 ¡.047 .032 .005 ¡.037 .095

Organizational distinctiveness .072 .021 .129 .062 .237** Interorganizational competition .219* .211** .051 .040 .032 Intraorganizational competition ¡.075 ¡.076 .084 .083 .007

Organizational prestige .088 .034 .129 .043 .285** Organizational identification .203* .296*** — AdjustedR2 ¡.017 .025* .053* .017 .071** .138*** .006 .181***

DR2 .018 .063 .032 .051 .073 .068 .039 .188

Fstatistics 0.523 1.452 1.886* 1.519 2.345* 3.568*** 1.177 4.955*** df# 6, 168 10, 164 11, 163 6, 171 10, 167 11, 166 6, 173 10, 169

Note. nD194. Standardized regression coefficients are reported.

*p<.05 (two-tailed). **p<.01 (two-tailed). ***p<.001 (two-tailed).#regression and residual degree of freedom.

432 P. Y. TSUI AND H-Y. NGO

Hong Kong under the business school context only. Other antecedents (e.g., organizational commitment) may exist that can affect members’ OI first. Additional studies in other faculties/universities in China or Asia would be nec-essary to elucidate this issue.

Implications

In addition to the previous theoretical findings, this research provides some practical insights. First, employees coming from collectivist cultures, such as those in Asia, often pos-sess a stronger identification with their organization than do those from individualistic cultures. Second, this study found that organizations should increase the perceptions of organi-zational distinctiveness and prestige among their employees in order to raise their members’ OI. To increase distinc-tiveness, possible strategies include having charismatic lead-ers or specialized curricula and programs, creating a unique organizational culture and values, as well as developing relationships between stakeholders (Clark, 1970). To enhance members’ perceptions of organizational prestige and their OI, universities/business schools should commence or continue actively participating in various international ranking exercises that signify status and competence (but not purely for the sake of competition). There are numerous ways to achieve this goal. For example, universities may recruit prominent faculty, such as Nobel laureates and com-munity leaders, name buildings and erect statues honoring prominent individuals, maintain high admission standards, establish ties with world-renowned institutions, and strive for internationalization. In addition, high-commitment human resource strategies that increase individuals’ evalua-tion of their own status inside of their organizaevalua-tion may help. Examples of this are perceived growth opportunities and participation in decision making by the employees (Fuller et al., 2006). Third, this study revealed that creating a competitive culture between (or inside) business schools did not help to increase members’ OI. If leaders of these business schools/universities emphasize competition, this may be disadvantageous because it may lower their mem-bers’ sense of belonging. Fourth, different from Western findings, members of Chinese society tended to exhibit cooperative behavior that was related to their own role spec-ifications, as well as those beyond their job assignments. Given the existing reform pressure, universities should pay close attention to their members’ OI levels and their rela-tionship with employee behaviors. This issue is particularly important for people in collectivistic cultures.

REFERENCES

Ashforth, B. E., Harrison, S. H., & Corley, K. G. (2008). Identification in organizations: An examination of four fundamental questions.Journal of Management,34, 325–374.

Ashforth, B. E., & Mael, F. A. (1989). Social identity theory and the orga-nization.Academy of Management Review,14, 20–39.

Baron, R. M., & Kenny, D. A. (1986). The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

51, 1173–1182.

Brown, R. J., & Ross, G. F. (1982). The battle for acceptance: An investi-gation into the dynamics of intergroup behavior. In H. Tajfel (Ed.),

Social identity and intergroup relations (pp. 155–178). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Clark, B. R. (1970).The distinctive college: Antioch, Reed and Swarth-more. Chicago, IL: Aldine.

Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2000). The rankings game: Managing busi-ness school reputation.Corporate Reputation Review,3, 319–333. Deem, R., Mok, K. H., & Lucas, L. (2008). Transforming higher education

in whose image? Exploring the concept of the “world-class” university in Europe and Asia.Higher Education Policy,21, 83–97.

Edwards, L. L. (2005). A model of the effects of reputational rankings on organizational change.Organization Science,16, 701–720.

Elsbach, K. D., & Kramer, R. M. (1996). Members’ responses to organiza-tional identity threat: Encountering and countering the Business Week rankings.Administrative Science Quarterly,41, 442–476.

Fuller, J. B., Hester, K., Barnett, T., Frey, L., Relyea, C., & Beu, D. (2006). Perceived external prestige and internal respect: New insights into the organizational identification process. Human Relations, 59, 815–846.

Gioia, D. A., & Corley, K. G. (2002). Being good versus looking good: Business school rankings and the circean transformation from substance to image.Academy of Management Learning and Education,1, 107–120. Heritage Foundation. (2015).2015 index of economic freedom.The

Heri-tage Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.heriHeri-tage.org/index Hofstede, G. H. (2001).Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors,

institutions, and organizations across nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Hogg, M. A. (1996). Social identity, self-categorization, and the small

group. In J. Davis & E. Witte (Eds.),Understanding group behavior: Vol. 2. Small group processes and interpersonal relations (pp. 227– 254). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Hou, M. J., Fan, P. H., & Liu, H. (2014). A ranking analysis of the manage-ment schools in Greater China (2000–2010): Evidence from the SSCI database.Journal of Education for Business,89, 230–240.

Kreutzer, D. W., & Wood, W. C. (2007). Value-added adjustment in undergraduate business school ranking.Journal of Education for Busi-ness,82, 357–362.

Liu, Y., Loi, R., & Lam, L. W. (2011). Linking organizational identifica-tion and employee performance in teams: The moderating role of team-member exchange.International Journal of Human Resource Manage-ment,22, 3187–3201.

Mael, F. A., & Ashforth, B. E. (1992). Alumni and their alma mater: A par-tial test of the reformulated model of organizational identification. Jour-nal of OrganizatioJour-nal Behavior,13, 103–123.

Marginson, S. (2007). Global university rankings: Implication in general and for Australia.Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management,

29, 131–142.

Meyer, J. P., & Allen, N. J. (1997).Commitment in the workplace: Theory, research and application. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Mok, K. H., & Nelson, A. R. (2013). Introduction: The changing roles of academics and administrators in times of uncertainty.Asia Pacific Edu-cation Review,14, 1–9.

Mudambi, R., Peng, M. W., & Weng, D. H. (2008). Research rankings of Asia Pacific business schools: Global versus local knowledge strategies.

Asia Pacific Journal of Management,25, 171–188.

Ngo, H. Y., Loi, R., Foley, S., Zheng, X. M., & Zhang, L. Q. (2013). Per-ceptions of organizational context and job attitudes: The mediating effect of organizational identification.Asia Pacific Journal of Manage-ment,30, 149–168.

O’Connell, C. (2013). Research discourses surrounding global university rankings: Exploring the relationship with policy and practice recommen-dations.Higher Education,65, 709–723.

O’Reilly, C. A., & Chatman, J. (1986). Organizational commitment and psychological attachment: The effects of compliance, identification, and internalization on prosocial behavior.Journal of Applied Psychology,

71, 492–499.

Olkkonen, M., & Lipponnen, J. (2006). Relationships between organiza-tional justice, identification with organization and work unit, and group-related outcome.Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Pro-cesses,100, 202–215.

Organ, D. W., Podsakoff, P. M., & MacKenzie, S. P. (2006). Organiza-tional citizenship behavior: Its nature, antecedents, and consequences. London, England: Sage.

Peters, K. (2007). Business school rankings: Content and context.Journal of Management Development,26, 49–53.

Pratt, M. G. (1998). To be or not to be? Central questions in organizational identification. In D. A. Whetten & P. C. Godfrey (Eds.),Identity in organizations: Building theory through conversations (pp. 171–208). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Riketta, M. (2005). Organizational identification: A meta-analysis.Journal of Vocational Behavior,66, 358–384.

Selznick, P. (1957).Leadership in administration. Berkeley, CA: Univer-sity of California Press.

So, A. Y. (2013). Globalism and competitive culture in the universities of Hong Kong.Education Research Journal,3, 1–6.

Somech, A., & Drach-Zahavy, A. (2000). Understanding extra-role behavior in schools: The relationships between job satisfaction, sense of efficacy, and teachers’ extra-role behavior.Teaching and Teacher Education,16, 649–659. Swann, W. B. Jr. (1987). Identity negotiation: Where two roads meet.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,53, 1038–1051. Tajfel, H. (1978). The achievement of group differentiation. In H. Tajfel (Ed.),

Differentiation between social groups: Studies in the social psychology of intergroup relations(pp. 77–98). London, England: Academic Press. Tso, S. K. (2005).Organizational identification under unfavourable

out-come: A factory study in China. (Unpublished doctoral thesis). Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong.

van Knippenberg, D., & van Schie, C. M. (2000). Foci and correlates of organizational identification. Journal of Occupational and Organiza-tional Psychology,73, 137–147.

Williams, L. J., & Anderson, S. E. (1991). Job satisfaction and organiza-tional commitment as predictors of organizaorganiza-tional citizenship and in-role behaviors.Journal of Management,17, 601–617.

Winter, R. (2009). Academic manager or managed academic? Academic identity schisms in higher education.Journal of Higher Education Pol-icy and Management,31, 121–131.

Yao, X. Z., & Tu, W. M. (2011).Confucian studies: Critical concepts in Asian philosophy. New York, NY: Routledge.

434 P. Y. TSUI AND H-Y. NGO