Storytelling in Urban Wayfinding

Shiho Asada

Formatting and printing: Shiho Asada

Images: Figure 4 is recreated by Asada based on the original figure prepared by Montgomery. The rest of figures are found from books or online. The sources and URLs are included in captions.

Proofreading: Andrew Baird

Abstract

Contents

Abstract 3

1 Introduction 7

2 Context 10

2.1 The many faces of storytelling 10

Literary usage 10

Storytelling as a means of community development 11 The storytelling approach in the private sector 11

2.2 Urban wayfinding 12

Types of urban wayfinding 12

Urban wayfinding in city design 14

2.3 Can storytelling be used in the design of urban wayfinding systems? 18

3 Case studies: storytelling in urban wayfinding in practice 23

3.1 Research method 23

3.2.1 Pedestrian wayfinding — Ben Acornley 25

The meaning of storytelling 27

Reasons for using storytelling 27

Storytelling in the urban wayfinding design process 28

Relationship to clients 34

Relationship with the culture and identity of a place 35 Discussion 38 Summary 40 3.2.2 Interactive wayfinding — Sami Niemelä 40

The meaning of storytelling 43

Reasons for using storytelling 43

Storytelling in the urban wayfinding design process 44

Relationship to clients 46

Relationship with the culture and identity of a place 46 Discussion 47 Summary 48

4 Conclusion 49

1 Introduction

In recent years, mobile web mapping applications such as Google Maps have found use beyond their traditional function as a means of pedestrian wayfinding and have become increasingly popular for exploring cities and urban landscapes. But while Google Maps is extremely effective at finding particular routes or locations it lacks the capacity to provide users with a unique experience of the city that they are exploring. Take, for example, London and New York, beyond distinct street names and grid layouts, the experience of exploring these very different cities through Google Maps is essentially the same. As Goldberger (2007) argues, when people discover a city through their mobile phones, they may physically be in that city but their minds are focusing on other places. For many, the act of exploring a new urban landscape has therefore necessarily become less an enjoyable experience.

The fact remains, however, that those visiting a particular city still want to experience those distinctive features and quirks that make that city unique even as this has become more challenging as a result of globalisation. As Simón (2013) has highlighted, it is imperative for cities to have a strong identity in order to attract tourism and enterprise in the age of globalisation. The founder of Applied Wayfinding, Tim Fendley (2015), contends;

‘The differentiation and distinctiveness peculiar to places will have more, not less, importance in the digital age. Events, unique gatherings and face to face meetings will become more powerful. And local flavour, accent, and attitude will be even more sought after.’

The challenges of creating an effective and enticing method of guiding people around a city, however, are numerous. Retaining the walker’s attention, navigating them to their destination and fostering an appreciation of the city are perhaps the most obvious of these challenges. In order to confront these issues, those designing urban wayfinding systems must have an understanding of a broad array of fields from urban design to user experience as well as an appreciation of both information and graphic design.

But what approaches can be used in developing an effective means of urban wayfinding? Bill Moggridge (2008), one of the founders of IDEO, has suggested storytelling as a possible solution for tying together the various aspects which make a successful urban wayfinding system. He states:

‘When you put all these things together, with elements from

architecture, physical design, electronic technology from software, how do you actually prototype an idea for a service, and it seems that really, it’s about storytelling, it’s about narrative.’

The ability that storytelling has to synthesise the various elements of a complex service system chimes closely with the requirements of urban wayfinding design.

and prospective students including information from their own experiences such as shortcuts they had found or difficulties that they had experienced when navigating their own way round the department.

2 Context

As a human centred approach1, storytelling has been increasingly

used by businesses and corporations as a means of more effectively engaging with consumers and, consequently, has begun to feature strongly in areas such as urban design and information design. Before considering the idea of utilising storytelling as an approach for developing methods of urban wayfinding, it is necessary to both define storytelling within more familiar contexts as well as provide a more comprehensive understanding of what is meant by the concept of urban wayfinding.

2.1

The many faces of storytelling

Literary usage

Storytelling can also be referred to as narrative, a term primarily used in linguistic and literary studies. It should, however, be noted that there are clear distinctions between what is narrative and what is a story (Chatman 1978). While a story contains elements such as a plot, characters and settings, the narrative is the way in which that story is told whether that is verbally, in a film, through dance or through a landscape. Prince’s (1987), A Dictionary of Narratology defines narrative as:

“The recounting (as product and process, object and act, structure and structuration) of one or more real or fictions events communicated by one, two, or several (more or less overt) narrators to one, two, or several (more or less overt) narratees.”

According to this definition, text that is purely descriptive (i.e.‘the fish is blue’/ ‘Anne is tall’) cannot be narratives whereas that which depicts specific events (i.e. the fish died’/ ‘Anne broke a glass’) are considered to be narratives. As well as in the spoken or written word, these defining features of narrative are also evident in other mediums of storytelling, such as fixed or moving images, gestures, music and landscapes (Barthes 1977, 79; Prince 1987, 58). Narrative has been a key component of the cultural landscape for millennia and is a fixture of many of humanity’s most celebrated modes of 1. Human-centred approach

storytelling from myths, fables and epics to tragedies, comedies and dramas while also underpinning less familiar methods of storytelling such as paintings and festivals. It is clear, therefore, that narrative, through the mediums listed above, is a significant element in people’s everyday lives which has led to individuals increasingly understanding their surroundings and experiences through the recollection, interpretation and creation of stories.

Storytelling as a means of community development

Narrative also has an important role to play in the community; the study of the forms and functions of narrative in the everyday has been carried out by researchers’ in disciplines as wide-ranging as sociolinguistics, folklore, anthropology and literary theory who have explored the relationship between the use of language and society. As Johnstone (1990) states, narratives are ‘shared voices which reflect the texture of the community’. Narratives allow people to communicate with and understand each within communities and wider society through stories that foster a sense of shared cultural experience. Pre-historic cave drawings which depict animals, human beings and simple objects are perhaps one of the most powerful examples of this. They have been found in most parts of the world: from Europe to Africa, America, Asia, Australia, and the Polynesian Islands. The oldest ones were found in Lascaux and Niaux, southern France, drawn around 13,000 bce. The pictures (Fig. 1) were frequently drawn on cave walls serving as a prompt to those narrating stories while also helping their audience to visualise the tale being recounted (Poulin 2012). Consequently, caves became a venue for listening to stories for these communities. Stories, therefore, not only bring people together but also tie people to specific places.

The storytelling approach in the private sector

In recent years, storytelling has become an influential strategy in the world of business by allowing companies to convert their insights and service ideas into user experiences. Companies now use the art of storytelling as a means of communicating with consumers as evidenced by adverts designed to portray the lives of their customers or depict the experiences of their employees. Demonstrating why a customer might use a particular product /

Figure 1. Cave painting, Cougnac, France, 13,000 bce

Poulin, Graphic Design + Architecture, a 20th Century History: A Guide to Type, Image, Symbol, and Visual Storytelling in

service or developing personas around their product/service are common examples of how this technique is utilised. By using these methods, companies are able demonstrate the applications and functions of their products to consumers much more effectively than by simply stating dry facts (Hensel 2010). A corporation which has been successful in using the storytelling approach to sell their products is technology giant Apple. Apple’s particular brand of advertising tells a story rather than simply saying ‘buy our product’ and this has evidently appealed to customers. After purchasing an iPhone at an Apple Store, the customer removes the sleek packaging in which the new phone is encased, all the while remembering the product which they have seen in adverts and displayed on Apple’s website. Once the outer packaging has been removed, the customer then finds a well-designed brochure made attractive by stunning photography before they finally uncover the much anticipated iPhone. It is this experience which has proved so appealing by giving users their own story.

Although contemporary appropriations of the art of storytelling may sound different from its literary and oral origins, the role of stories in modern society remains the same, to share experiences and make things understandable to everybody in a particular community or place.

2.2

Urban wayfinding

Types of urban wayfinding

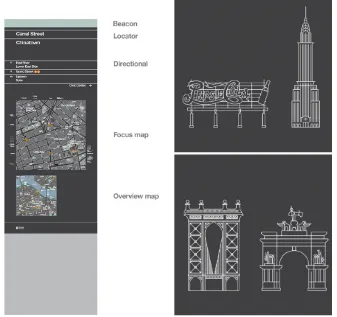

while On The Go Interactive Wayfinding Kiosks (Fig. 3), operated by Control Group, are situated in subway stations and provide users with features such as countdown to arrival, real-time train information one-touch graphic maps, district maps and local advertising (Control Group 2015). Although both are managed by New York’s Metropolitan Transport Authority (mta), they clearly fulfil different functions.

The emergence of digital technology has greatly expanded the potential of urban wayfinding systems. As Mollerup highlights, interactive kiosks, smartphone apps, qr codes and augmented reality not only enable people to find a route to a particular location but also facilitate the exploration and understanding

Figure 2. WalkNYC designed by Pentagram, in corporation with City ID, Billings Jackson Design, rba Group and T-Kartor, 2013

http://new.pentagram.com/2013/06/new-work-nyc-wayfinding/

Figure 3. On The Go Interactive Wayfinding Kiosks, designed by Control Group in corporation with mta, 2014

of new urban landscapes. Moreover, utilising real time data can provide people with details of the quickest and most convenient way of getting somewhere by factoring in sources of delay such as traffic congestion. Bays and Callanan (2012) highlight that this technology is used widely by local authorities and administrations to understand the needs of urban areas as well as to overcome challenges and exploit opportunities.

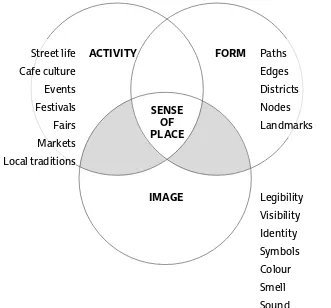

Urban wayfinding in city design

The way in which people travel around a metropolitan area is, of course, a crucial consideration when designing a city. Before focusing on the role of wayfinding in urban design, it is necessary to highlight the essential qualities and elements of planning what could be termed a ‘good city’. Numerous theories and strategies for urban design have been put forward since the 1960s but, as the European Commission highlights in a Green Paper published in 1990, generating and protecting a sense of place is an essential element of city design. The notion of a ‘sense of place’ can broadly be defined as those unique features such as historical heritage and cultural identity which differentiate one place from another. Montgomery (1989), a renowned urban planner, points out that fostering a sense of place is at the heart of planning a good city. He also states that a good urban environment has quality in three essential areas: form (landmarks, public streets), image (legibility, symbols) and activity (street life and events, local traditions)

Figure 4. Policy directions to foster an urban sense of place. Urban wayfinding may exists in between Form and Image, or Image and Activity (areas of grey colour).

John Montgomery, ‘Making a City: Urbanity, Vitality and Urban Design.’

With respect to image, the primary function of urban wayfinding systems in this area is to improve the definition and perceptibility of city forms. As Lynch (1960) states, there are five core elements which comprise the form of a city: paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks all of which should be clearly recognisable with intuitive and consistent symbols if an urban wayfinding system is to both capture and contribute to the form of individual cities. A map with pictograms and illustrated landmarks or a set of written instructions are, for instance, methods that can be used to emphasise the form of a city within urban wayfinding systems. New York, for example, boasts a wayfinding system that is particularly effective at demonstrating the unique form and character of the city through cartography, pictograms and typography which are consistent as well as a clear hierarchy of information (Fig.5). Moreover, illustrations of notable landmarks

(Fig.6) are simplified by being easily recognisable.

Figure 7. Logo of London underground http://media-2.web.britannica.com/eb-media/46/

Figure 8. The first logo of London underground Poulin, Graphic Design + Architecture, a 20th Century History: A Guide to Type, Image, Symbol, and Visual Storytelling in the Modern World

Figure 5 (left).

WalkNYC, hierarchy of information produced by Pentagram, 2013.

http://new.pentagram.com/2013/06/new-work-nyc-wayfinding/

Figure 6 (right).

WalkNYC, landmark illustrations for maps designed by Pentagram, 2013.

http://new.pentagram.com/2013/06/new-work-nyc-wayfinding/

Figure 9. Tokyo Art Beat app released by Gadago npo.

Left: Shows exhibitions nearby a user Right: Map of nearby exhibitions http://www.tokyoartbeat.com 2. Mental maps

Lynch (1960) defines mental maps are simple sketches of maps drawn from memory of urban areas. He used mental maps collected from citizens of three cities of the USA in order to reveal the geographical and social problems of the cities.

Furthermore, since the importance of the psychological impacts of urban design were first discussed by Lynch (1960), designers of wayfinding systems have sought to introduce cues which enable people to form mental maps2. Developing systems which

contribute to or invoke feelings of safety, comfort, vibrancy or quietude is essential in urban wayfinding.

• Activity

location so that events which are not to the user’s taste, unpopular or inaccessible can be easily filtered out. This kind of digital urban wayfinding therefore not only contributes to the distinct identity of a city but also helps people access events and places that they want to experience.

As such, generating and protecting a sense of place may be possible by improving the quality of urban wayfinding systems available. Indeed instilling a sense of place has become increasingly important as cities vie with each other to attract enterprise and tourism on both the national and global stage (Radovic, 2008). Richard Simón (2013), Planning Director at Applied Wayfinding highlights that metropolises throughout the world are struggling to meet the challenges of developing sustainable communities, alleviating pressure on increasingly congested transport links as well as protect and promote cultural diversity. Ensuring that there are distinct features not seen anywhere else in the world is key to the planning and branding of a city.

2.3 Can storytelling be used in the design of

urban wayfinding systems?

The multi-faceted, complex nature of designing methods of urban wayfinding would seem to suggest that storytelling could hold the key to the development of urban wayfinding systems which reflect the character and distinctiveness of the city that it services. Due to the limited number of sources available on the relationship between storytelling and wayfinding, this

dissertation will also consider the existing literature on the impact of storytelling techniques in related fields including urban design and information design to develop a broader understanding of the benefits that the storytelling approach offers. Many scholars and practitioners in the fields identified above have reflected on the potential of storytelling in their work but interpretations and uses of it can vary considerably due to the demands and nuances of their respective areas of study.

Figure 10. Paris Metro Entrance designed by

Figure 11. Mockup of a concept idea of Otaniemi metro station platform, 2010 Viña, and Mattelmäki, ‘Spicing up Public Journeys – Storytelling as a Design Strategy.’

to convey aspects of culture and tradition in an effort to create an image and establish a sense of place (Potteiger and Purinton 1998; Childs 2008). In some cases these stories reflect religious or political issues, ideas or values (Eagleton 1983; Duncan and Duncan 1988) such as in the case of Greater London which was established by London County Council in the wake of World War II to help address issues arising from population growth, housing shortages, unemployment and growing pressure on transport. As this example clearly demonstrates, storytelling in urban spaces reflects the cultures, traditions and political issues that shape a city’s image and identity.

Similarly, environmental graphic design such as signs and

billboards have been described as visual storytelling (Poulin 2012). Over the centuries, collaboration across the fields of architecture and graphic design has shaped the cityscapes that are the defining feature of urban centres across the world today. The basic tenets of environmental graphic design are typography, images and symbols all of which can be used to convey a sense of time and place in a city as well as contribute to the visual stories told by the architecture of buildings and landmarks. The entrance to the Paris Metro, designed by Hector Guimard (Fig. 10), is an iconic example of the interplay between architecture and environmental graphic design. The typography, inspired by the work of French type designer, George Auriol, exists in complete harmony with the art-nouveau style of the surrounding architecture providing a striking identity and brand for the Paris Metro.

The analysis above considers isolated examples of where storytelling has been incorporated into the design of urban environments and spaces but, similar to the aim of this

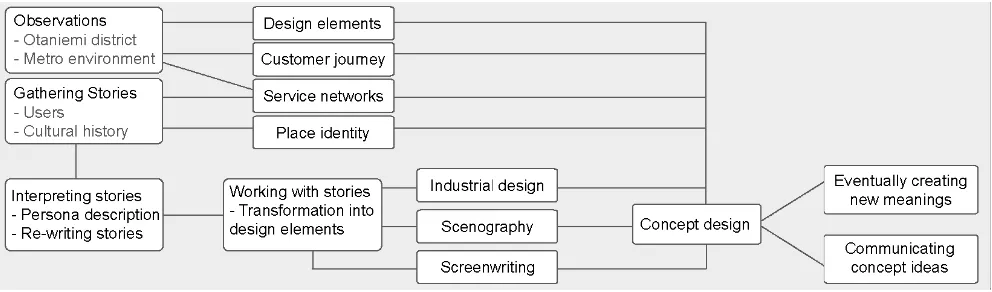

Figure 12. The path of storytelling as a design strategy prepared by Viña and Mattelmäki, 2010. Storytelling is not a single process. One process and its outcome relate to more than one next processes.

Viña, and Mattelmäki, ‘Spicing up Public Journeys – Storytelling as a Design Strategy.’

more towards space design and urban experiences, Viña and Mattelmäkis’ interpretation of storytelling and the processes that were followed in order to create an enjoyable public space at the Metro Station in Otaniemi are remarkable. They define the purpose of storytelling approaches as the need to, ‘identify, strengthen and create a strong identity of a place in which inhabitants and travellers can relate to’.

Figure 12 is a visualisation of the processes which Viña and Mattelmäki followed in order to successfully use the storytelling approach as a design strategy. Their first step was to develop an understanding of the distinct identity of Otaniemi which was achieved through observation of the district as a whole and the environment around the Metro station. Stories from residents of Otaneimi were also gathered and collated through interview design probes, a method used by sociologists to collect data and information on user journeys and urban practices, which enabled Viña and Mattelmäki to build up a picture of the cultural history of the area and clarified specific elements of the design of the experiential space. The final part of the project was to come up with the final concept of the design based on the outcomes of their research. Viña and Mattelmäki concluded that the storytelling approach was the most effective means of realising their vision of creating an aesthetically powerful experiential space that interacts with human emotions and engages all of the senses. Moreover, storytelling was also used to create and arrange the image that the service projected.

3. Look and feel

According to Davis (2009), it is ’the visual style of a brand which encompasses the brand mark, colours, font and images’. The look and feel produces a visual identity of the brand, and it is utilised in the commercial world.

4. Touchpoint

Touchpoint is defined as ‘any point of contact between a Customer and the Service Provider’ (The Master Board 2013). Regarding urban wayfinding system, touchpoints are pedestrian signs, maps in transportation and mobile applications.

the research phase when stories are collected from users and information is gathered from the surrounding environment. In terms of the information design element of wayfinding, system designers can collate users’ stories on how they journey through a given environment such as the strategies they use, what

shortcuts they take and any difficulties that they encounter. They can then build up a nuanced picture of user experiences, personas and journeys from these findings (Moldenhauer 2003). Information about the identity of a specific environment or place can also be gleaned from aspects of the cityscape such as the five elements posited by Lynch (1960) (paths, edges, districts, nodes and landmarks). The heritage of a city should also be given consideration, for example, does the city have its origins as a market towns or ports or did it develop from the protection and patronage of a castle? The information gained from these areas of research is important in designing all elements of the wayfinding system from its most basic functions to the overall look and feel3 of

the system.

Secondly, storytelling is also effective at developing a holistic service system that incorporates the many different requirements of urban wayfinding in the 21st Century which demands the

coordination and management of an array of organisations, service touchpoints4 and design features. Despite the complex make up of

cities, in the main people are disinclined to learn more than one method of wayfinding and, as such, Fendley (2015) has suggested that cities should have just one user-friendly system. Stories which are developed from an understanding of the needs of customers’ and the interplay between people and places is a means of tying the cityscape, architecture, communication, marketing and user experience elements of urban wayfinding together. Storytelling, therefore, is a way of creating a service and system that fulfils users’ requirements while at the same time cutting through the complexity of cities.

of the system such as place names, typography, colour palette and how landmarks are illustrated. All of these features help to capture the distinctive social and historical narrative that makes each city unique.

It can therefore be asserted that the storytelling approach enables designers to create comprehensive, human-centred wayfinding systems which provide users with a unique experience of the city they are in. Beyond their primary function as a navigational tool, wayfinding systems can impart information about the history and traditions of a city through succinct, well organised facts and anecdotes while its cultural identity and character can be reflected through its visual aspects. If urban wayfinding is able to marry these features tastefully it will contribute to both a distinctive identity of the city and generate a sense of place.

It is, however, rare for wayfinding designers to attempt to capture the cultural identity of the city in the systems that they create. Krzysztofiak (2011), in his thesis Wayfinding in Poland, concludes that many wayfinding designers in Poland are unaware of the impact that the visualisation of wayfinding can have on the image and branding of public places. He discovers that designers give little thought to the notion of trying to reflect Polish culture and identity in the systems they develop suggesting a lack of understanding of the importance of wayfinding as a form of environmental graphic design. Rather it appears that greater significance has been placed on ensuring that representations are accurate and easily understood.

Watson and Bentley (2007) assert that every aspect of a city contributes to how its identity is constructed and projected. Wayfinding may just be one small part of the many elements and features that comprise a city but it undoubtedly has a part to play through the provision of a unique experience which offers a distilled version of that city’s distinct identity to users.

3.1

Research method

The limited number of sources available on how storytelling can be applied to urban wayfinding does present some challenges for developing a coherent understanding of the relationship between the two. Furthermore, as alluded to above, storytelling is, by nature, ambiguous meaning that the interpretation and uses of this approach for the purposes of urban wayfinding design has the potential to vary considerably among practitioners. For this reason, it was decided to conduct more accurate research by interviewing experts in the field of urban wayfinding with a focus on how they have interpreted and utilised the storytelling approach in their own projects.

Designers who practice storytelling methods in either physical or digital urban wayfinding systems were invited to take part in interviews. The first of these was with Ben Acornley, Partner and Creative Director at Applied Wayfinding, UK. Acornley has been involved in numerous urban wayfinding projects including Legible London as well as having a wealth of experience in the areas of editorial and branding. Acornley was approached for an interview on account of his intuitive use of storytelling approaches when developing methods of pedestrian wayfinding as well as his insights on detailed visual communication and branding. The second interviewee was Sami Niemelä, Creative Director and Co-Founder of Nordkapp based in Helsinki. One of his major projects, Urbanflow, is a concept piece which posits the idea of an operating system for individual cities (Nordkapp and Urbanscale 2011). Niemelä was approached for an interview due to his efforts to create better urban spaces through human-centred interaction design as well as his use of storytelling for prototyping interactive wayfinding and product presentation. Acornley was asked to propose the most convenient time for an interview and this was conducted at the office of Applied Wayfinding. The conversation which took place was recorded and notes were taken. Due to the length of the discussion and the complex nature of some of the

language used, the interview is only partially transcribed and is summarised rather than written in full in this dissertation. The interview with Niemelä was conducted in the form of an email questionnaire and is cited in full. The disparity in the volume of material taken from each interview is due to the different ways that they were conducted with Acornley’s interview yielding much more information due to the fact that it was a one-hour conversation in person during which numerous projects were discussed. By contrast, the interview with Niemelä by email only gave the opportunity to discuss one project. The two participants were asked the same set of questions regarding urban wayfinding projects that they have been involved in, with a specific emphasis on uncovering what the concept of storytelling means to them, the advantages of the storytelling approach at different phases of the design process and the effect it has on user experience and visual outcomes. The first five questions were specifically ordered to mirror the process of wayfinding design: defining meaning and methodology, developing the system and the concept, designing the visuals and, lastly, evaluating the results. The final question, Question 6, sought to explore how storytelling relates to the culture and identity of a place.

The section on case studies is divided between the two interviewees. Each case will begin with a description of the participants’ company and some of the projects they have been involved in following which the interviewee and their role in each of the projects will be introduced. Finally, their answers to each of the questions will be presented and discussed in detail. The contents of each interview will be categorised into the following five sections: The meaning of storytelling, Reasons for using storytelling, Storytelling in the urban wayfinding design process, Relationship to clients and Relationship with the cultural and

List of questions:

1. What does storytelling mean to you?

2. Why do you use storytelling in your wayfinding project? 3. How do you use storytelling in your wayfinding project? At what stages in designing do you use storytelling?

4. How do you introduce the concept of storytelling into a client’s brief?

5. In what ways has storytelling affected the outcomes of your projects?

6. In what ways do you relate storytelling to the culture and identity of a place? How does this affect the visual design?

3.2.1

Pedestrian wayfinding — Ben Acornley

Although there is an abundance of research material available on pedestrian wayfinding, the majority of it tends to concentrate on ways to improve the legibility and usability of these systems through visual design, for example, colour contrasts and typography. This would appear to suggest that more research is required on enhancing user experience and the contribution that wayfinding can make to the identity of a city. Indeed, Applied Wayfinding have implemented a number of pedestrian wayfinding projects during which they have conducted extensive research on user experiences and how these systems translate across cultural boundaries. To explore how Applied Wayfinding have combined the findings of their research with the narrative of the areas in which they created wayfinding systems was the purpose of the interview with Ben Acornley.

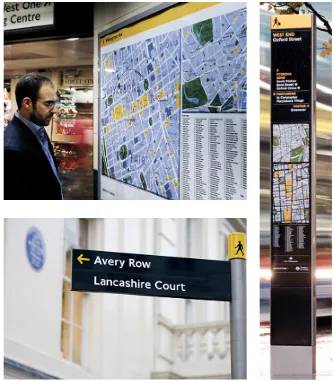

Applied Wayfinding is an international consultancy based in London which has built its name on designing legible systems for diverse and complex environments. The Company garnered a strong reputation in the wake of their Legible London (Fig. 13–15)

Figure 13 (left). Legible London, map in underground stations designed by Applied Wayfinding

http://appliedwayfinding.com/

Figure 14 (right). Legible London, on-street minilith designed by Applied Wayfinding http://appliedwayfinding.com/

Figure 15. Legible London, totem sign designed by Applied Wayfinding http://appliedwayfinding.com/

as well as developing a system for Heathrow Airport. Through these projects, Applied Wayfinding have been at the forefront of exploring the potential of urban wayfinding which they have achieved through careful research and intelligent analysis of the legibility of cities. Despite the complex environments and information with which they work, expertise in the editorial and design fields have allowed them to ensure that the experience of the end user is the focus of the systems that they create.

worked for many years at branding design studios. His background in editorial design, branding and in-depth understanding of

typography have strongly influenced the visual presentation of the wayfinding projects undertaken by the Company.

In the following sections, a summary of the interview with

Acornley is provided and is considered in conjunction with a book which was been written on the Legible London project entitled Yellow Book: A Prototype Wayfinding System for London, published by Applied Information Group (now Applied Wayfinding) in 2007.

The meaning of storytelling

For Acornley, storytelling is about effectively interpreting and projecting the image of a particular place by understanding its essential components and characteristics. He believes that while landmarks and tourist attractions are important protagonists in the narrative of any city, to understand the full story one must look beyond the obvious and consider every facet of that city’s character including the people that make up the city and the culture

and traditions to which they contribute. This interpretation of storytelling chimes with the perspective of many urban designers (Potteiger and Purinton 1998; Childs 2008) particularly Acornley’s view on the role that architectural and cultural features play in a city’s story.

Reasons for using storytelling

and informative experience that connects them with their surroundings, something which storytelling is particularly effective at achieving. If urban wayfinding can provide tourists with good experiences and leave them with fond memories of the place they have visited by providing an effective and informative means of navigation then this will hopefully make them more likely to want to return. Conversely, poorly designed wayfinding systems which lead to visitors getting lost will ultimately make them less likely to want to come back.

Storytelling in the urban wayfinding design process

As explained above, Acornley’s interpretation of storytelling is a method which enables designers to capture the character of a specific place and, consequently, begins during the research phase of the project when it is considered alongside the needs of people and visitors as they interact with the surrounding environment. Storytelling is further used to provide a succinct description of the city which can be easily understood by local residents and visitors alike. The storytelling approach is therefore applicable during numerous phases of the project from the initial research to the development and implementation of the system.

• Identifying the character of a place

Acornley emphasises that environmental information, forms of architecture and graphic language are picked up and decoded as representations of a particular place. In the case of Legible London, building design, urban form, street layout, lighting, use of street furniture and public art are the important elements (Applied Information Group 2007); Acornley describes these features as ‘the story of architecture’. Although identifying the character of a place constitutes the initial stage of the project, the information that this research provides is fundamental in shaping the way in which the system develops and how the visual elements of the way finding system are designed.

• Observing people

system. Conducting interviews with users about their experiences and journey through the environment where the wayfinding system will be located is an effective means of collecting and collating users’ stories. The interviewee cited to the project which he undertook in Qatar as an example, stating that ‘because of the heat, people in Qatar prefer using their cars rather than walking, so they need information about car parking’. Therefore, the information that people require depends on their behaviours and customs. Visiting the location where the wayfinding system will be located in order to conduct field research is perhaps the best way of observing people and gathering user stories.

• User persona

Acornley asserts that designers should seek to understand and develop systems that meet the needs and expectations of different groups of users including residents, tourists and commuters. The journeys that these groups take through an environment vary considerably and thus observations should lead to the

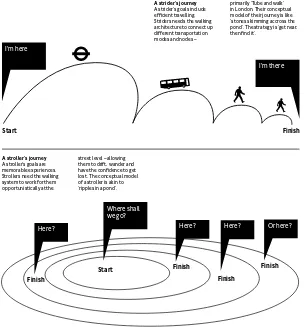

development of several user personas that will inform the eventual design of the system. In the case of Legible London, the project team identified four main groups of people from their research, namely novice striders, expert striders, novice strollers and expert strollers (Applied Information Group 2007). Those termed as striders wish to travel efficiently utilising available methods of transport whereas strollers prefer to traverse and explore the city on foot (Fig.16). Legible London was created in order to meet the needs of all the four groups identified during the research phase is reflected in the user experience. Such as in this case, designing a system which is capable of responding to the requirements of each user persona identified is a necessity for the development of a successful method of wayfinding.

• Mapping

A strider’s journey

A strider’s goals include efficient travelling. Striders needs the walking architecture to connect up different transportation modes and nodes –

primarily ‘Tube and walk’ in London. Their conceptual model of their journey is like ‘stones skimming accross the pond’. The strategy is ‘get near, then find it’.

A stroller’s journey

A stroller’s goals are memorable experiences. Strollers need the walking system to work for them opportunistically at the

street level – allowing them to drift, wander and have the confidence to get lost. The conceptual model of a stroller is akin to

Here? Here? Here? Or here?

I'm here

I'm there

Figure 16. Legible London,diagrams of two types of user journeys produced by Applied Wayfinding

Applied Information Group, Yellow Book: A Prototype Wayfinding System for London.

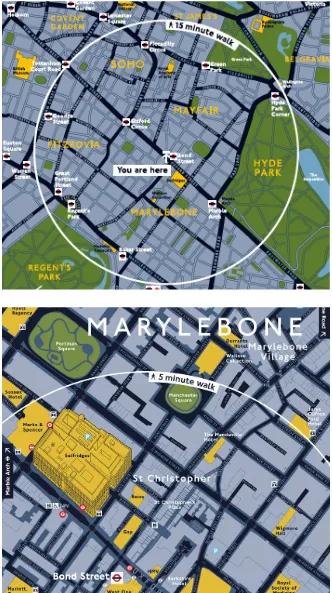

has two different types of map, a wider map termed a ‘Planner’ or ‘15-minute map’ (Fig. 17) which primarily show how close areas are to each other as well as pinpointing transport hubs. As such, these maps are designed to help people plan long distance journeys on foot and keep track of where sites such as bus stops and underground stations are located. ‘Finder’ or ‘5-minute’ maps

(Fig.18) are narrower but provide a more detailed representation of a smaller area with landmarks appearing as 3d illustrations in order to guide users to the end point of their journey. The two types of maps have described above fulfil separate functions and provide user experiences that are distinct.

Figure 18. Finder/ 5-minute map of Legible London by Applied Wayfinding

https://onemillionsigns.files.wordpress. com/2009/04/picture-85.png

Figure 17. Planner/ 15-minute map of Legible London by Applied Wayfinding

is governed by flight schedules and this can often make for a stressful experience. At the same time, however, when they aren’t dashing from check-in to boarding, people want to be able to go for a coffee or visit duty free and both of these extremes had to be factored into the design of their wayfinding system. To address this challenge, Applied Wayfinding created information hierarchies which were reflected in the design of maps with the location of individual terminals being the most important feature, followed by gates, shops and so on. It was also important to link the hierarchy together so that spatial relationships are clearly identifiable to users. The result was the creation of what has been termed a ‘Living Map’ system (Fig. 19–21) which accurately represents the layout of the entire airport and clearly demonstrates the easiest and quickest way to get between two places. The map is available in both digital (on the Heathrow Airport website and mobile app) and printed formats (on signs and printed in airport magazines), it is necessary to update the map every two weeks reflecting the fact that Heathrow Airport is perpetually in flux. Having both printed and digital versions means that those passing through the airport can access information about the location of shops, restaurants and other facilities in whichever format they prefer. By comparison, the wayfinding systems in operation at the majority of airports around the world are largely similar in terms of the typeface and colour schemes they use with most opting for a san-serif font in black on a yellow background. Despite the fact that the wayfinding system at Heathrow utilises the same colour palette as at most airports, the Living Map offers travellers an experience which is unique to Heathrow Airport and one which enables them to use their time more efficiently.

Some designers are sceptical about the necessity of a detailed map in wayfinding systems and prefer to use a more minimalistic approach which relies on streamlined directional signage. Applied Wayfinding (Applied Information Group 2007) contests this

view, describing maps as the simplest and most effective way of providing users with a wealth of information. Maps offer a rich experience and have the capacity to provide a quick answer to questions that users may have about their present location, where their destination is situated, the quickest route to their destination

Figure 19. Living Map System for Heathrow Airport, mobile application designed by Applied Wayfinding

Figure 20. Living Map System for Heathrow Airport, heads-up sign designed by Applied Wayfinding

http://appliedwayfinding.com/

Figure 21. Living Map System for Heathrow Airport, web site designed by Applied Wayfinding

Figure 22. Legible London, 3d building for maps designed by Applied Wayfinding Applied Information Group, Yellow Book: A Prototype Wayfinding System for London.

Figure 23. New Johnston Transportation for London originally designed by Edward Johnston, and redesigned by Eiichi Kono Applied Information Group, Yellow Book: A Prototype Wayfinding System for London.

as well as the length of the time the journey might take. It can therefore be said that maps are at the heart of the storytelling approach in urban wayfinding design.

• Designing the visual

It is Acornley’s view that visual outcomes should be related to the features of where the wayfinding system is being designed for such as iconic locations and landmarks. Elements of the system such as product design, colour palette and 3d illustrations of buildings

(Fig. 22) should be a reflection of the identity and narrative of where it is located. In the Legible London project, for example, the typeface used is same as one used by Transport for London, New Johnston (Fig. 23). Acornley suggests that if aspects of the surrounding environment are evident in the visual aesthetic of the system this will provoke an unconscious fascination in users. It is, however, also important to ensure that information is presented clearly and succinctly so as not to appear daunting or difficult to decipher. This is why buildings and landmarks are illustrated in 3d (Fig. 22) on maps designed by Applied Wayfinding as what is sacrificed in the technical aspects of the illustration are more than made up for in the usability of the map particularly for people who may struggle to read maps such as those with learning disabilities (Applied Information Group 2007). Therefore, the storytelling approach can influence wayfinding design by helping it to reflect the character and features of the surrounding environment while at the same time presenting concise, well-organised information to users. It is these features that both enrich a user’s experience and give them greater confidence in exploring the city around them.

Relationship to clients

and then consider the best format and approach (i.e. walking map or mobile application) to use in order to achieve this. For example, Walk Brighton (Fig. 24–27), is a wide-ranging wayfinding system developed by Applied Wayfinding in conjunction with Brighton and Hove City Council in order to enhance tourism in the area (Applied Wayfinding 2015). Monolith signs have been constructed throughout the city, including on the beach, and provide an intuitive navigational tool for visitors. Conversely, Leeds Walk It

(Fig. 28–30) was developed with the City Centre Management Team of Leeds City Council in order to facilitate better integration between two new major shopping centres, Trinity Leeds and Eastgate Quarters and has been successful in improving the

experience for shoppers’ in Leeds. Legible London, by contrast was project with a number of stakeholders spanning transportation authorities, local government and the business community including Westminster City Council, the New West End Company, Transport for London, the Mayor of London and the Crown Estate. The brief was to design a harmonised wayfinding system across the capital in time for the London Olympic Games in 2012. Applied Wayfinding was successful in balancing the expectations of all parties involved in the project to create a system that is deceptively simple given the large and diverse area that it covers. The outcome of this project has significantly contributed to improving tourism and has increased the commercial success of the area that it covers. Wayfinding is far more nuanced than simply directing people to a particular location and, as this section shows, there can be any number of reasons why a local authority or business might commission a wayfinding system. The flexible nature of storytelling makes it suitable for a variety of purposes and can be adapted to encapsulate the character and identity of where the wayfinding system is being developed for.

Relationship with the culture and identity of a place

Figure 24 (left). Walk Brighton, minilith sign designed by Applied Wayfinding

http://appliedwayfinding.com/

Figure 25 (right). Walk Brighton, on-street monolith designed by Applied Wayfinding http://appliedwayfinding.com/

Figure 26. Walk Brighton, Brighton

iconography designed by Applied Wayfinding http://appliedwayfinding.com/

Figure 27. Walk Brighton, Brighton base map designed by Applied Wayfinding

Figure 28. Leeds Walk It, on-street monolith designed by Applied Wayfinding

http://appliedwayfinding.com/

Figure 29. Leeds Walk It, on-street map designed by Applied Wayfinding http://appliedwayfinding.com/

Figure 30. Leeds Walk It, Leeds handy map for the shopping area designed by Applied Wayfinding

Linked appearance of typography

Figure 31 (above). ‘OXFORD STREET’ on a map of Legible London designed by Applied Wayfinding

Figure 32 (below) ‘OXFORD STREET’ on a street sign, London

Applied Information Group, Yellow Book: A Prototype Wayfinding System for London

projects, Legible London and Walk Brighton. In particular, the typography and colour palette used for the Legible London is strongly influenced by the classic and sober visual identity of the city it represents. In conjunction with the impact of utilising a font similar to that used by Transport for London, the use of uppercase lettering on Legible London maps (Fig. 31) is in order to mirror the look of London street signs (Fig. 32) (Applied Information Group 2007). This is also useful for individuals from countries who use a non-Roman alphabet by allowing them to relate street signs to information contained within the maps more easily. Furthermore, the combination of white or yellow text on a dark blue background reflects the character of London while ensuring that text is clear to users. The visual identity of Walk Brighton differs considerably from the look of Legible London, reflecting Brighton’s character as a vibrant city whose location by the sea has made it popular with tourists. The pale green colour in the design shown in Figure 24

was taken from the fences situated along the beach. Moreover, the maps located along the promenade are longer than those in the town centre thereby reflecting the topography of the beach. Acornley indicates that the amount of information contained on the maps is significantly less than those designed for the Legible London project. The maps in Walk Brighton are relatively fixed and enable tourists to roam around Brighton’s beach, town centre and parks freely. The separate wayfinding systems designed for London and Brighton are a celebration of the distinct cultural and historical identity of each city something which is clearly reflected in the design and usability of the systems created by Applied Wayfinding and is something which should be aspired to in all wayfinding projects. By doing so, these systems can contribute to the sense of place and a city’s individual identity as discussed in Chapter 2.

Discussion

Acornley utilises storytelling throughout many stages of the wayfinding design process including research, cartography and visual development. His approach to storytelling shares similarities with the three ways of using this method for developing wayfinding systems identified in Chapter 2:

system and ensuring that the completed project reflects the cultural identity of the place in which it is located. As emphasised on a number of occasions throughout the interview, however, Acornley believes the storytelling approach to be at its most useful in identifying and translating the distinct features of a place. These are gathered through architectural and environmental information as well as by developing an understanding of people’s needs and movements. Once these features have been identified they can be reflected in the visual design of the wayfinding system such as through the typography, colour palette and even the shape of signs as demonstrated in the Walk Brighton project (Fig. 24). People’s behaviours when journeying through a particular environment can then be distilled into user personas which influence the appearance of maps and other aspects of the system.

Summary

» Storytelling is to pick up the features of place

» Stories are collected from environments, users and clients » Storytelling approach should be developed flexibly adjusted for each city

» Storytelling can be used in many phases in designing: research, mapping and visual development

» Visual outcomes reflect the features and identity of the place

3.2.2

Interactive wayfinding — Sami Niemelä

Real-time data is a phenomenon which has only recently been considered by designers as a way of improving the information available through urban wayfinding. As a result, the majority of cases discussed in this section are still in the development or prototype phase. The advantages that real-time data can bring to urban wayfinding, however, are not disputed and it is anticipated that the opportunities it presents for ensuring that information is always accurate and up-to-date have important implications for the future of urban wayfinding. Although the Urbanflow (2011) project which has been developed by Nordkapp is still in the prototype stage, it offers an excellent example of how storytelling can contribute to the development of interactive wayfinding models particularly given that storytelling can enhance the prototyping process. The prototype model of Urbanflow is currently being developed for Helsinki and so the project is called Urbanflow Helsinki. To uncover how the storytelling approach can be used in prototyping interactive forms of wayfinding through display screens in urban centres was the reason that Sami Niemelä was chosen as an interviewee.

Nordkapp is a product and information design firm based in Helsinki, Finland. They specialise in developing strategic approaches to information and data visualisation as well as

interaction and interface design. Urbanflow Helsinki is a prototype project co-created by Nordkapp and Urbanscale and which

and Urbanscale 2011). The aim of the project is to ‘make the city more accessible and enjoyable for both residents and visitors through a situated interactive service which uses living data from the city. It would offer far-reaching benefits for both city administrators and local citizens. Urbanflow can be tailored to meet the needs and address the challenges of different cities, in its prototype form, however, it is Urbanflow Helsinki and has been developed in conjunction with Forum Virium Helsinki, a research centre owned by the City of Helsinki to invent and design new digital service. Although this project is not yet at the stage of installing screens in Helsinki, a concept video (Fig. 33) was released in 2011, which offers an insight into what it is intended Urbanflow will look like when it is finished. The video also

demonstrates the advantages that the system will provide when it has been completed including the use of information outlets such the screens mentioned above for wayfinding and other purposes, allowing eventual users to visual how the Urbanflow Helsinki will work in practice.

Sami Niemelä is the Creative Director of Nordkapp. His primary involvement in the Urbanflow project has been to refine the concept, conduct research, develop the prototype and direct presentational videos. Niemelä’s vision is to use design in order to rethink cities and urban living through ‘the lens of functional and human centric design (Niemelä 2012). He has an intrinsic appreciation of simplicity which owes much to his time growing up in the Finnish countryside while his preference for functional design, apparent in Alva Aalto, echoes Finland’s socialist political model. Besides urban information design, Niemelä has strong insights into interaction and interface design.

Figure 33. Urbanflow Helsinki, concept video

produced by Nordkapp, 2011

This video shows how Urbanflow works in the real world in combination of filming and motion graphics. Although this project looks futuristic, this video enables viewers to imagine how it benefits them.

The meaning of storytelling

Niemelä (2012) has drawn attention to the fact that the use of stories, or narratives, as a medium of communication is something shared by all cultures and civilizations for multiple purposes such as education, entertainment, and cultural preservation or for inculcating moral values in the community. Moreover, within the context of an urban environment, Niemelä asserts that storytelling can be a way of visualising the inordinate amount of data and information that cities produce. Reflecting on those views in light of his own experience, Niemelä suggests that:

‘Storytelling equals communication. Finding a suitable narrative to tell a story fit to a preset context is an important part of storytelling.’

Therefore, it can be said that storytelling has the potential to be an effective means of presenting interesting and informative data for the purposes urban wayfinding.

Reasons for using storytelling

Niemelä has identified three primary reasons for utilising the storytelling approach:

1. ‘Video is an excellent way to encapsulate a story. A good design fiction, speculative or product video tells a self-contained story of the why, what and how of a product.’

2. ‘Writing the narrative to the story forces you to think and prioritise, especially when writing a “sales pitch” to someone else. A voiceover and the reasonably short length of an average user’s attention span is a good restriction.’

3. ‘Lastly, on product level storytelling is a great way to introduce a product and the thing it does.’

City Council and win their support for the project. Promotional videos can be an effective and concise means of doing this by clearly demonstrating how users can interact with the system through urban screens while also providing insights into what advantages it can bring to the city and its inhabitants. Thus short videos are able to share both the concept and the advantages of projects such as Urbanflow Helsinki to system designers, potential stakeholders and future users.

Storytelling in the urban wayfinding design process • Making a concept and scenarios of a product Niemelä states:

‘For Urbanflow, the story was the final product. After the initial concept stage, communicating and truncating the story helped us to crystallize what we had.’

Urbanflow Helsinki is the culmination of extensive research and in depth analysis of the findings of this research. Firstly, Nordkapp conducted studies on interactive elements of the cityscape

exploring how people interacted with twenty different urban screens in Helsinki. At the time this research took place, urban screens were, in the main, non-interactive and were largely used for advertising purposes. This was followed up with interviews and observations in the cities of Helsinki and Tallinn over the course of a year to develop an understanding of people’s needs. From this research they identified three potential scenarios for using urban screens (Niemelä 2011; Nordkapp and Urbanscale 2011):

• Wayfinding for visitors and tourists (Fig. 34): it enables users to plan their journeys through live transit information and route suggestions.

• Showing and visualising real time information (Fig. 35) in relevant to people’s lives such asenergy consumption, traffic density air quality and municipal works.

• Enabling people to give direct feedback to the City.

Figure 34. Urbanflow Helsinki, live wayfinding using real-time transit information designed by Nordkapp, 2011

http://www.fastcoexist.com/1679254/ urbanflow-a-citys-information-visualized-in-real-time#1

Figure 35. Urbanflow Helsinki, visualisation of real-time information designed by Nordkapp, 2011

http://www.fastcoexist.com/1679254/ urbanflow-a-citys-information-visualized-in-real-time#1

piece of design fiction telling a story of how urban screens have a place in the city enhancing people’s lives and making the city more transparent and friendly for all’. In this way, storytelling has the ability to integrate and provide useful information from a city to its inhabitants in a logically ordered and attractive way. As a direct consequence of the research conducted and the presentation on the Urbanflow initiative which Niemelä and his team delivered, Nordkapp gained support in developing and implementing their idea from Urbanscale and Forum Virium in 2010.

• Introducing the product

final phase of the project could be an effective of way of winning support for a project.

• Effects on the outcome

Regarding the impact of storytelling on the outcomes of a project, however, Niemelä states:

‘Like I said, everything is a story, and design is about

communicating. I wouldn’t say storytelling itself has much effect, but instead it just is part of the final delivery. A video is a video of course, so that sets the tone and bar for a certain type of resources.’

This shows clearly that he does not believe storytelling has a direct or tangible influence on outcomes. Rather, he emphasises the role of storytelling as a communication tool useful during the implementation phase of the project and how it can be used to present ideas in an appealing way.

Relationship to clients

In his answer to question 4, Niemelä states that, ‘sometimes as an end product [a video], most times not at all since it is a part of the process anyway’ Niemelä’s primary use of the storytelling approach is to distil a number of factors into a single concept. Urbanflow’s concept video, for example, is successful at integrating elements such as the background, purposes and values of the projects in order to communicate these to clients. For prototype projects, demonstrating what the system will be able to do when it is fully functional could be vital for securing the support and funding from clients and stakeholders.

Relationship with the culture and identity of a place Niemelä indicates:

‘The culture and identity of a place tell the story at large. Graphic design is a strong part of identity of a place– both current in form of advertising and wayfinding as well as in layered history such as remains of past places, signs and so forth.’

Figure 36. Urbanflow Helsinki, interface of map designed by Nordkapp

Typeface: Proxima Nova designed by Mark Simonson

On urban screens, this typeface balance legibility and warms.

http://www.fastcoexist.com/1679254/ urbanflow-a-citys-information-visualized-in-real-time#1

of them are environmental graphic designs that represent the features of a place, construct its cityscape and form an identity. The design of the Urbanflow Helsinki map (Fig. 36)is also inspired by the look and feel of Helsinki (Nordkapp and Urbanscale 2011). Yet the system is also highly flexible and can be adapted to fit with the aesthetic and reflect the identity of other cities by changing features such as typography.

Additionally Niemelä (2012) considers a city to consist of numerous layers that have developed at different speeds and which have come into being at different times. The layers referred to by the interviewee are things such as fashion, commerce, infrastructure, governance, culture and nature. Urban interactive wayfinding can therefore combine these physical and figurative layers of a city through digital technology in order to add new meanings to abandoned spaces and recount the story of a place from a variety of perspectives. As such, digital wayfinding systems can contribute to the character of a city and emphasise aspects which give it a distinct identity.

Discussion

the values of the product and also highlight the context in which it will be used.

As Niemelä mainly works in the field of interaction and interface design, Urbanflow is primarily about urban interaction design rather than traditional wayfinding. Interestingly, he views cities as a combination of huge amounts of different types of data which he then uses technology to curate and present which he describes as ‘telling compelling stories’. Despite this, Niemelä appreciates the importance of incorporating the cultural and historical identity of cities into the design of the systems which he develops. Using interactive screens for the purposes of urban wayfinding offers the opportunity to use compelling stories to package interesting and informative data for users.

Summary

» Storytelling is communication

» Storytelling does not affect outcome significantly, but is useful for developing a concept which consists of numerous ideas and extensive research, as well as for presenting the appealing points of a product

» Videos are a powerful form of media which capture a story and convey it to many people

4 Conclusion

The outcome of the two interviews demonstrate how storytelling based approaches to urban wayfinding systems differ amongst those who design them. Whereas Acornley utilises storytelling in many stages of the development process, from research and cartography to final visual development; Niemelä perceives the value of storytelling to be as an effective and compelling means of communicating with clients and users once the project has been completed. Acornley focuses on understanding the features and narrative of an environment which can then be translated into visual outcomes while Niemelä’s preference is to use the storytelling approach to build a narrative around the product itself which can then be put into a format such as a short video.

Despite the clear disparities in the way that Acornley and Niemelä view the role that storytelling approaches can play in developing wayfinding systems, they seem to share the opinion that storytelling can be particularly effective at integrating and synthesising various elements into a single idea. In the initial stages of developing a wayfinding system, for example, both interviewees feel that the storytelling approach can be an effective means of integrating aspects including the needs of both users’ and clients as well as information about the surrounding environment. Designing an urban wayfinding system is a complicated task that encompasses a wide range of disciplines from city planning to information design, the storytelling approach helps to galvanise these disparate areas and channel them into a single concept.

Furthermore, both Acornley and Niemelä emphasise the

nowhere else. By providing visitors with fond memories of exploring a city, a well-designed, effective wayfinding system will ultimately encourage visitors to return. The advent of real-time data has also dramatically expanded the possibilities of wayfinding particularly in the realm of information relating to transportation as highlighted by the Urbanflow project. This has the potential to change the face of these systems providing benefits to local authorities, residents and tourists.

As regards the interviewees that were chosen for this dissertation, the task of finding designers who advocate user-centred

approaches and the inclusion of cultural aspects in their wayfinding models was challenging as many prefer to focus on the technical aspects of their projects. Acornley suggests that this may be as a result of an undue emphasis on design theory and wayfinding technique. Placing pedestrian experience should be at the heart of creating any wayfinding system.

Interviews

Participants quoted in the dissertation:

Acornley, Ben. Interview by Shiho Asada. Recording, 20 August 2015. London.

Bibliography

Applied Information Group. 2007. Yellow Book: A Prototype Wayfinding System for London. London: Mayor of London.

Applied Wayfinding. 2015. ‘Applied Wayfinding.’ http:// appliedwayfinding.com/.

Barthes, Roland. 1977. Image, Music, Text. Translated by Stephen Heath. New York: Hill and Wang.

Bays, Jonathan, and Laura Callanan. 2012. ‘Emerging Trends in Urban Informatics.’ New York: McKinsey & Company.

Chatman, Seymour Benjamin. 1978. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Childs, Mark C. 2008. ‘Storytelling and Urban Design.’ Journal of

Urbanism: International Research

on Placemaking and Urban Sustainability 1 (2): 173–86. doi:10.1080/17549170802221526.

Cullen, Gordon. 1961. Townscape. New York: Reinhold Pub. Corp.

Davis, Melissa. 2009. The Fundamentals of Branding. Switzerland: AVA Publishing

de Waal, Martijn. 2014. The City as Interface: How Digital Media Are Changing the City. Translated by Vivien Reid. Rotterdam: nai010 publishers.

Duncan, James, and Nancy Duncan. 1988. ‘(Re)reading the

Landscape.’ Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 6 (2): 117–26.

European Commission. 1990. Green Papaer on the Urban Environment. Brussels: EC.

Fendley, Tim. 2015. ‘What next for Legible Cities?’ Eg Magazine 12.

Finnegan, Ruth H. 1988. Literacy and Orality: Studies in the Technology of Communication. Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

Goldberger, Paul. 2007. ‘Disconnected Urbanism.’ Metropolis Magazine. February. http://www.metropolismag.com/ December-1969/Disconnected-Urbanism/.

Hensel, Jason. 2010. ‘Once Upon a Time.’ Meeting Professionals International. February. http://www.mpiweb.org/ Magazine/Archive/US/February2010/OnceUponATime.

Johnstone, Barbara. 1990. Stories, Community, and Place Narratives from Middle America. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Krzysztofiak, Jan. 2011. ‘Wayfinding Systems in Poland’. Reading: University of Reading.

Lawrence, David. 2000. A Logo for London: The London Transport Bar and Circle. Middlesex: Capital Transport Publishing.

Lynch, Kevin. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Moggridge, Bill. 2008. ‘Prototyping Services with Storytelling.’ presented at the Danish CIID conference Service Design Symposium., May 14. http://www.180360720.no/?p=276.

Moldenhauer, Judith A. 2003. ‘Storytelling and the Personalization of Information: A Way to Teach User-Based Information Design.’ Information Design Journal 11 (2): 230–42.

Montgomery, John. 1998. ‘Making a City: Urbanity, Vitality

and Urban Design.’ Journal of Urban Design 3 (1): 93–116. doi:10.1080/13574809808724418.

Niemelä, Sami. 2011. ‘Building Urbanflow Helsinki.’ Nordkapp. September 12. http://nordkapp.fi/blog/2011/09/building- urbanflow-helsinki/.

Niemelä, Sami. 2012. ‘Stories, Behaviour and Purpose.’ presented at the Mashable Innovation Series / BMW Guggenheim Labs Berlin, July. http://nordkapp.fi/blog/2012/07/talk-

stories-behaviour-and-purpose/.

Nordkapp. 2011 ‘Urbanflow Helsinki.’ http://helsinki.urbanflow.io.

Norman, Donald A. 2013. The Design of Everyday Things. The revised and expanded edition. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press.

Potteiger, Matthew, and Jamie Purinton. 1998. Landscape

Narratives: Design Practices for Telling Stories. New York: John Willey & Sons, Inc.

Poulin, Richard. 2012. Graphic Design + Architecture, a 20th Century History: A Guide to Type, Image, Symbol, and

Visual Storytelling in the Modern World. Beverly, MA: Rockport Publishers.

Prince, Gerald. 1987. A Dictionary of Narratology. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Radovic, Darko. 2008. ‘The World City Hypothesis Revisited: Export and Import of Urbanity Is a Dangerous Business.’ In World Cities and Urban Form Fragmented, Polycentric,