Geography

Vol 99 Part 1 Spring 2014176

Geographical

leadership,

sustainability

and urban

education

Geographical

leadership,

sustainability

and urban

education

Andrew Kirby

ABSTRACT: Geography possesses in its intellectual DNA a unique ability to understand cities. Decades ago, it embarked on this project but was distracted, for a number of reasons. The emergence of a field committed to sustainability has renewed the relevance of urban education. This, the first of two articles, begins to identify what geography has to offer. In the second article, I will suggest in greater detail how the discipline can provide leadership both in schools and in public policy in relation to studies of cities and sustainability.

Introduction

The purpose of this and a second, linked, article (to be published later in 2014) is to explore the possibility of a realignment of geographical practice. As this is not a minor undertaking, in this article I lay out what I believe to be missing from contemporary geography, and, in the second article, I provide a route map towards a different disciplinary focus. Although this may be seen by some as ‘angry geography-bashing’ (as one reviewer put it) that is not my intention. I am not professionally invested in criticism of the discipline, but I am perplexed that geography’s place in both school and the public sphere seems to have been eclipsed in recent years.

The critique offered in this first article is actually part of a broader analysis of urban studies, which aims to show that much of what is taken for granted in the field is no longer appropriate. Urban geography is relevant to this critique, but no more so than several other disciplines. However – and this is the main reason I have written these articles – geography is very much central to what I envisage as a re-structured urban studies. Indeed, the need for this within public policy is so pressing that it has, in my view, the potential to place geography at the forefront of educational practice. The remainder of this article is an elaboration of this bold claim.

Geography and the urban

opportunity

First is a brief and highly selective assessment of Anglophone geography in the twentieth century, which, I am keen to show, had the potential to craft a sophisticated field – urban geography – and to provide intellectual leadership within urban studies. However, this did not come about for several reasons.

Geographers were once so concerned with regions that it was very unusual to teach about cities (see Pacione, 2005, for an excellent summary). This situation changed in the 1960s as researchers in the United States began to focus on cities and systems of cities, using quantitative methods to explore economic ideas. Concurrently, researchers in the UK began to look at the internal

mechanisms of urban structure, and invoked more social and political forms of explanation.

Geography was, therefore, uniquely placed: the discipline possessed the potential to see cities within complex urban networks, and yet as part of the landscape in its broadest sense. But these were fated to be disparate endeavours. Since then, urban ideas have not only become more

Green thinkinghas promoted an environmental consciousness, although that observation itself masks the complexity of contributions to this evolution. The anti-technological stance dates back at least to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring

(1962); an anti-population-growth stance that can be traced to the time of Robert Malthus (the nineteenth-century cleric), and an anti-urban sentiment that extends back to the Romantic ideals of the nineteenth century. It has also tended to be global in its consciousness (Castells, 1996).

In contrast, the brown revolution has argued – and fought – for individual and collective rights, especially in the global South. Linked to urban social movements (also identified by Castells,

1983), the demands for basic services such as water and housing have highlighted the inequalities manifested in the rapidly-expanding megacities of Latin America, India and Africa.

Taken together, green and brown thought are the obverse of neoliberalism . This was arguably the most powerful strand of public policy-thinking in the decades prior to the financial meltdown of 2008. With its critiques of public spending and its claims for unfettered global competition,

neoliberalism has powerfully implicated cities as engines of capital accumulation and transfer, while focusing attention on urban competition via such things as branding, bond ratings and a discourse of ‘creative cities’.

177

Geographical

leadership,

sustainability

and urban

education

If we turn to contemporary cities, we find diversity and much contradiction as to what they represent. Figure 1 indicates some of the complexity of how cities are now viewed, identifying three distinct perspectives: green thinking, the brown revolution and neoliberalism (see, for instance, Vojnovic, 2013).

Together, these very different perspectives have produced a complex and even contradictory characterisation of what cities are. This notion of complexity is developed further in Figure 2 (overleaf), which focuses on specifically academic literatures – i.e. world cities, anti-global and climate change perspectives – as they relate to our urban understanding.

When we bring all of these different strands together we see that we have a remarkably

confusing tableau: on the one hand cities are seen as a basic component of the global economic project, and on the other is the view that urban development is destroying the planet. The historian Carl Schorske (1981) has defined this as a fundamental struggle between city as ‘good’ and city as ‘evil’. The most recent attempt to resolve this contradiction has manifested itself in a broad literature of urban sustainability and concomitant efforts to redesign cities in order to achieve climate change mitigation goals.

The professional

consensus: what is a

sustainable city?

There is strong professional agreement on the importance of sustainability, which urban

Figure 1:Current perspectives on the city: green thinking, the brown revolution and

neoliberalism. See text for explanation.

Geography

Vol 99 Part 1 Spring 2014Green

thinking

Brown

revolution

178

Geographical

leadership,

sustainability

and urban

education

The first strand can be classified as the world or global citiesliterature. This has various

components, all of which share an emphasis on the networks – Castells (1996) terms them ‘flows’ – that connect cities within the global economy. These flows can be financial transfers, but ideas, workers and commodities (and even drugs and people who are trafficked) are included.

The second strand comprises the many different empirical projects that focus on the lived experience of urban residents. In the same way that world cities research is rarely ‘pro-globalism’, most contemporary work on is not explicitly anti-globalrather its stance is broadly critical of urban life. In essence, the anti-global perspective offers a critique of the privatisation and the loss of public space; the fragmentation of the city and the creation of private spaces (such as shopping malls and gated communities); and the gentrification of neighbourhoods, endemic

homelessness and life in slums. In large measure, the anti-global is a literature that mourns the dense organic city and bemoans the creation of suburbs; its nemesis is sprawl and its champion is smart growth. It is multidisciplinary but connected in its implicit belief that urban space can and should reflect progressive social values.

From this standpoint, cities should not be implicated in the processes whereby social, political and economic inequalities are manifested in urban landscapes, nor should they reify

segregation, food deserts and obesity, social stress and violence.

The third, climate change, is perhaps the most powerful perspective on the city of all. This emerging body of knowledge has placed attention firmly upon the planet as the crucial scale of policy development. It has underscored the dangers that result from greenhouse gas emissions, implicated the automobile in this equation, and emphasised relentlessly that mitigation is the only appropriate course of action. What this means is that we now have a powerful argument which states that cities are the fundamental cause of climate change and that this has arisen as a consequence of industrial development in the nineteenth century, suburban development in the twentieth and rural-to-urban migration in the twenty-first century. This thinking extrapolates that, for mitigation to occur (for the planet to survive), cities must be re-conceived and redesigned and sustainable cities are the crucible within which our future rests.

Geography

Vol 99 Part 1 Spring 2014Geography

Vol 99 Part 1 Spring 2014179

Geographical

leadership,

sustainability

and urban

education

geography acknowledges. Ellin writes that, ‘there is now a virtual consensus among planners and urban designers about what constitutes good urbanism’ (2013, p. 1), but it is less clear just what the pathway to sustainability might be and how it is to be accomplished.

Some of the challenges become apparent in our attempts to find a robust definition of ‘sustainable urbanism’, which has inherited the vagueness of the broader sustainability field (see Jackson, 2009). In an editorial launching a journal devoted solely to this topic (entitled Sustainable Cities and Society), Riffat can only offer this anodyne statement:

’A new model of sustainability is needed. This will provide greater incentives to save energy, reduce consumption of resources and protect the environment. Sustainable cities should be a dense and socially diverse environment where economic and social activities overlap and where communities are focused around neighbourhoods. Cities increase energy efficiency, consume fewer resources, produce less pollution and avoid urban sprawl. Future cities must be developed or adapted to meet the emerging needs of its [sic] citizens’

(2011, p. 1).

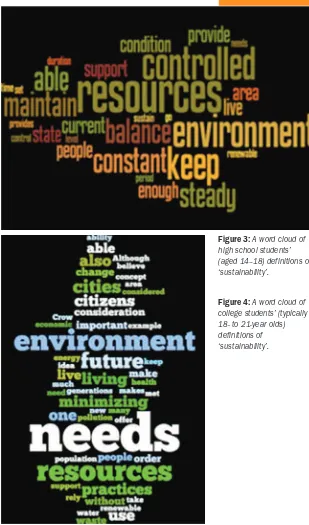

This does not take us very far beyond the kinds of ideas that can be generated by any individual. Figures 3 and 4 show ‘word clouds’; these are aggregations of the definitions of ‘sustainability’ created by high school and college students, respectively.2As we can see from the students’

responses, issues of resource use and

environmental health predominate, although some more nuanced ideas are represented, including ‘citizenship’ and ‘waste’.

Perhaps because of the complexities and contradictions identified above it is more usual to find statements in the literature about what constitutes an unsustainablecity. In a

representative passage, Roseland points to ‘low-density single-family dwellings, car-dominated transport systems, unchecked waste, omnipresent air conditioning and profligate water use’ (2012, p. 23). Working with these indicators, plenty of examples describe what constitutes good (and bad) practice. In the United States, Portland (Oregon) is frequently used as an exemplar of a sustainable city – the city has become something of a poster child, although high-density, compact cities with public good transport systems, such as Manhattan and San Francisco, are also lauded (Glaeser, 2011). Singapore is also on the ‘good city’ list, alongside European examples such as

London (UK), Paris (France), Freiburg (Germany), Copenhagen (Denmark), Helsinki (Finland), Venice (Italy) and Vitoria-Gasteiz (Spain) (Beatley, 2012). The antitheses to these ‘good’ cities, automobile-dependent metro areas such as Houston, Las Vegas and Phoenix (USA) are typically excluded, due to their indiscriminate sprawl. In fact, Ross claims that Phoenix, Arizona, is the ‘least

sustainable city [on the planet]’ (2011). There are two significant limits to this literature. First, while it may encompass many facets (for example, the Freiburg Charter – an annual award given to outstandingly sustainable cities (see

Figure 3:A word cloud of high school students’ (aged 14–18) definitions of ‘sustainability’.

Geography

Vol 99 Part 1 Spring 2014Academy of Urbanism, 1992) – has 12 elements ranging from diversity to governance), the concern for compact cities rests ultimately on a single key goal: climate change mitigation. Second, in emphasising a narrow selection of city design ‘norms’, it may produce socially-unjust outcomes. Here, it is important to note this critique is introduced en route to a different set of goals and outcomes, which will be developed in depth in the second article. Consequently, this discussion should neither be taken as evidence of scepticism of climate change nor as an endorsement of mindless consumerism and profligate energy use. Rather, it is intended to be read as consistent with reminders that any consideration of capitalist development is both complex and often at odds with the norms on display within the urban

sustainability literature (see, e.g. Westaway, 2009).

The limits to mitigation

For more than 30 years, the blueprints for arguments about natural resources have become fixed on the depletion of fossil fuels, the move to energy alternatives and the pressing need to reduce carbon emissions. These arguments do not exist in a vacuum: statements aboutoverpopulation and famine warnings have

continued for decades (Ehrlich and Ehrlich, 1991). However, these claims are of the direst sort; their advocates brook no dissent and no alternatives – see, for instance, Gore (2006) and Lambert (2008) on the obligations to deal with climate change; Hornborg (2009) on the extinction of the human species; and Heinberg and Lerch (2010) on the peak oil scenario, the depletion of energy resources and the obligations to develop clean alternatives.

However, one problem with such observations is that the planet’s health and energy future are much more complex than is claimed in these dystopian scenarios. The emergence of natural gas as a fuel cleaner than coal (although gas is neither a clean nor a renewable resource) is an example from the United States. Crying ‘wolf’ comes at a price in terms of allowing opponents to

delegitimise the entire issue and in terms of trying to deny energy options to the global South (e.g. Glaeser, 2011). The more pressing policy issue here is that there is no evidence that mitigation is, or can be, a successful strategy (e.g. Susskind, 2010). This is a controversial posture, and it is no exaggeration to state that nay-sayers like Bjørn Lomborg (2001) have been branded climate sceptics, which is (professionally) only one step away from being accused of holocaust denial (Oreskes and Conway, 2010). However, as Pielke et

al. (2007) argue, the debate is not about the rightness of the science (another equally complex issue in itself), instead it concerns the expense of this policy obligation and the zero sum costs it imposes elsewhere – a point I will return to in my follow-up article. Here it is sufficient to state agreement with the view of Pielke and colleagues: that the sums being spent on mitigation (with little result) could be better spent on helping those in poverty adapt to life in marginal locations which should result in more extensive and positive social outcomes.

Sustainability: for whom?

The second strand of critique offered here is that sustainability – asserted in a narrow context focused on resource use and abuse – cannot be simplistically applied to a complex social context such as a city. As several commentators, including Peter Marcuse (1998) and David Satterthwaite (2011), have argued, there are many social arrangements that are very sustainable (in the sense that these arrangements endure), but this tells us little to nothing about who benefits under such arrangements. The same is true of the more recent version offered within the engineering and planning literature: that of ‘resilience’. Just as the concept has been examined in the context of mental health, it is not only important that human arrangements endure, but also that they have positive outcomes for all concerned. When we begin to consider collective social outcomes in this way, it is more likely that merely sustaining or enduring in the face of climate change outcomes is not enough (Davoudi, 2012).What this implies is that the rubric of ‘sustainable cities’ is an essentially empty vessel into which we may pour whatever we choose. With an emphasis upon environmental concerns, we can prioritise specific design features and spatial outcomes, but as we have seen, these tend to produce

problematic social outcomes. Compact cities tend to be unaffordable cities, from which we can infer that the commonly-understood meaning of sustainability – i.e. a city with a minimal footprint, locally-sourced foods and a walkable environment – is (for most of us) as much an artificial construct as ‘Main Street’ in Walt Disney World. Portland, Oregon, may be the poster child for smart growth (see Figure 5), but the city offers affordable housing in only of 8 of its 225 neighbourhoods (Butz and Zuberi, 2012).

Geography

Vol 99 Part 1 Spring 2014181

Geographical

leadership,

sustainability

and urban

education

environments. The results of these economic pressures are clearly manifested in illegal infill, overcrowding, social anxiety and, often, health outcomes that pose a significant cost for the residents of these compact cities. Furthermore, this is evident in the megacities of the emerging economies, where we see an attenuated version of what comes with dense urban environments: traffic congestion, air and noise pollution and severe constraints on social and economic progress.

Moving to closure

This discussion opened with the observation that geography has not capitalised on its opportunities to provide strong intellectual leadership with regard to understanding urban development. Instead, it has joined the crowd with ‘critical’ rejections of the contemporary urban experience, a standpoint that offers no succour to residents of a planet with a population that is growing and which must (literally) accommodate 2 billion more urban residents. These families cannot be housed in versions of Portland, sustained by a lifestyle of heightened gentility. Nor, obviously enough, should they be crammed into a twenty-first-century version of Bijlmermeer (the vast and notorious housing development in Amsterdam), or the Lea Valley in the UK (see Pacione, 2013), or any one of the thousands of brutalist slums offered up by architects and planners in former decades.

The challenges of urban growth and urban poverty, especially in the global South, underline the reality that while mitigation is not the answer, adaptation truly is. We face an environmental crisis, but it is a variegated one. How shall we deal with an

uncertain future of climate change, or perhaps that should be a certain future of climate change, with such unknown and highly contextual outcomes? If this needs a clear demonstration, let us look to the example of New Orleans, perhaps the least-adapted city on the planet. As has already been demonstrated this century, the city is extremely vulnerable to natural damage (viz Hurricane Katrina in 2005), and, as it sinks year-by-year, is actually becoming less adapted while sea levels rise and storms become more unpredictable. We must confront the fact that world-wide there are 10,000 cities that demand this kind of attention: cities that are vulnerable to floods of all kinds, to fires, to earthquakes, to hurricanes, to tornadoes, and so on. Cities that demand an adaptive response in order to make them sustainable, places that truly provide their populations with some security for the future (Satterthwaite, 2012).

The discipline of geography has enormous potential here. The subject has, within its DNA if not in its current practice, all the elements to provide strong intellectual leadership. Practitioners have studied the city and done so in an

ideographic, contextual manner, which is what will

Geography

Vol 99 Part 1 Spring 2014be demanded in the future. Geography has the ability to integrate its understanding of both human and social systems in a way that other disciplines do not. It also has the powerful techniques to show how and where adaptive planning must take place, for example, via geographical information systems analysis.

Conclusion

This, the first of two articles, has deliberately taken several risks in questioning the efficacy of climate change mitigation and the robustness of thinking on urban sustainability. Its purpose is to propose a more radical alternative. The article holds out no comforting illusions concerning the safety of the planet; rather it demands that geography confronts the existing threats to life and livelihood faced by millions throughout the world on a daily basis. It is also intended as a call for geography to take action in order to bring about urban adaptation, which will be explored in more depth in the second article.

Notes

1. I should emphasise that, while I believe Michael Pacione (2005) is correct in his observations about increased diversity and disintegration, he himself does not appear to support this position.

2. The word clouds shown in Figures 3 and 4 are based on exercises undertaken with students in high schools and colleges respectively. Individual students were asked to provide a written definition of ‘sustainability’ and their responses were then converted to word clouds using Wordle.

References

Academy of Urbanism (1992) Freiberg Charter for Sustainable Urbanism. Available online at

www.academyofurbanism.org.uk/freiburg-charter (last accessed 8 November 2013).

Beatley, T. (2012) Green Cities of Europe. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Butz, A. and Zuberi, D. (2012) ‘Local approaches to counter a wider pattern? Urban poverty in Portland, Oregon’, The Social Science Journal, 49, pp. 359–67. Carson, R. (1962) Silent Spring.Boston, MA: Houghton

Mifflin.

Castells, M. (1983) The City and the Grassroots. London: Arnold.

Castells, M. (1996) The Rise of the Network Society. Massachusettes: Blackwell.

Davoudi, S. (2012) ‘Resilience: a bridging concept or a dead end?’,Planning Theory and Practice, 13, 2, pp. 299–307.

Ehrlich, P. and Ehrlich, A. (1991) The Population Explosion.

London: Simon & Schuster.

Ellin, N. (2013) Good Urbanism. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Glaeser, E. (2011) The Triumph of the City. New York, NY: Penguin.

Gore, A. (2006) An Inconvenient Truth: The planetary emergency of global warming and what we can do about it. Emmaus, PA: Rodale.

Heinberg, R. and Lerch, D. (eds) (2010) The Post Carbon Reader: Managing the 21st century’s sustainability crises.Bristol: Watershed Media.

Hornborg, A. (2009) ‘Zero-sum world challenges in conceptualizing environmental load displacement and ecologically unequal exchange in the world-system’,

International Journal of Comparative Sociology, 50, 3 – 4, pp. 237–62.

Jackson, P. (2009) ‘Editorial: thinking about sustainability’, Geography, 94, 1, pp. 2–3.

Lambert, D. (2008) ‘Inconvenient truths’, Geography, 93, 1, pp. 48–50

Lomborg. B. (2001) The Skeptical Environmentalist: Measuring the real state of the world. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Marcuse, P. (1998) ‘Sustainability is not enough’,

Environment and Urbanization, 10, 2, pp. 103–12. Oreskes, N. and Conway, E.M. (2010) Merchants of Doubt:

How a handful of scientists obscured the truth on issues from tobacco smoke to global warming.London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Pacione, M. (2005) ‘Sustainable urban development in the UK: rhetoric or reality?’, Geography, 92, 3, pp. 248– 65.

Pacione, M. (2013) ‘Urban sustainability in the UK’ in Vojnovic, I. (ed) Urban Sustainability, Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan University Press, pp. 611–32.

Pielke, R., Prins, G., Rayner, S. and Sarewitz, D. (2007) ‘Climate change 2007: lifting the taboo on adaptation’, Nature, 445, 7128, pp. 597–8. Riffat, S. (2011) ‘Welcome to a new journal – Sustainable

Cities and Society’, Sustainable Cities and Society, 1, 1, pp. 1–2.

Roseland, M. (2012) Toward Sustainable Communities: Solutions for citizens and their governments.Gabriola Island, BC: New Society Publishers.

Ross, A. (2011) Bird on Fire: Lessons from the world’s least sustainable city. New York: Oxford University Press.

Satterthwaite, D. (2011) ‘How urban societies can adapt to resource shortage and climate change’,

Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences, 369, 1942, pp. 1762–83.

Schorske, C.E. (1998) Thinking with History: Explorations in the passage to modernism.Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1998.

Susskind, L. (2010) ‘Policy and practice: responding to the risks posed by climate change: cities have no choice but to adapt’, Town Planning Review, 81, 3, pp. 217–35.

Vojnovic, I. (2013) Urban Sustainability: A global

perspective. Ann Arbor, MI: Michigan University Press. Westaway, J. (2009) ‘A sustainable future for geography?’

Geography, 94, 1, pp. 4–12.

Andrew Kirby is Professor of Social Sciences in the School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Arizona State University, Pheonix, USA (email: