InTRODUCTIOn

Advertisers often attempt to inluence media by asking for special favors in exchange for their advertising dollars. Abundant anecdotal (Atkin-son, 2004; Christians et al., 2009; Collins, 1992; Fine, 2004; Gorman, 2010; Gremillion and Yates, 1997; Hickey, 1998; Hoyt, 1990; Ives, 2010; Knecht, 1997; Rappleye, 1998; Sanders and Halliday, 2005; Sutel, 2005; Underwood, 1998a, 1998b) and more limited empirical evidence (An and Bergen, 2007; Hays and Reisner, 1990; Howland, 1989; Just and Levine, 2000; Just, Levine, and Regan, 2001; Price, 2003; Reisner and Walter, 1994; Soley and Craig, 1992) suggest the existence of “advertiser pressure”—the term introduced by Soley and Craig (1992).

Favors in exchange of advertising dollars are “on top of” the scheduled media buy and can range from special advertising placement to overt manip-ulation of editorial content including both favora-ble stories supporting the campaign and avoidance of any voices critical of the advertiser or its busi-ness category. “Advertiser pressure”—especially if

the tactic is successful—represents a serious threat to consumer interests and, as such, is a key (yet, often unrecognized) advertising-ethics issue.

The separation between editorial and advertis-ing content belongs to the core of normative jour-nalistic and media ethics, and it is often compared to the fundamental political principle of the separa-tion of “church and state” in modern democracies (Rappleye , 1998). Although the First Amendment of the U.S. Constitution advocates freedom only from state intervention, the notion of the “free media” often is understood in the sense of inde-pendence from commercial interests (Shoemaker and Reese, 1991).

In fact, some critics argue that “private entities in general and advertisers in particular constitute the most consistent and the most pernicious ‘censors’ of media content” (Baker, 1992, p. 2099). Indeed, the independent and free democratic press—which is not unduly inluenced by private or state inter-ests—is perceived as a key political institution to most political convictions.

norms of newspaper Editors and Ad Directors

GERGELY nYILASY university of Melbourne [email protected]

LEOnARD n. REID university of Georgia [email protected]

newspaper journalists and advertising directors were surveyed to update and extend

research on advertising pressure. Results reveal that:

• advertiser pressure is widespread in newspapers; despite economic threats, however,

advertisers succeed with their inluence attempts relatively infrequently;

• smaller newspapers do not differ much from larger ones with regard to any forms of

advertiser pressure;

• advertising directors are more permissive in their personal ethical norms for handling

advertiser pressure than editors;

• employees of small newspapers are not much more permissive in their ethical norms

than those of large papers; and

The second, more pragmatic, problem is the potential for consumer deception. As Hoyt suggested in the Columbia Journalism Review (1990, “From the reader’s perspec-tive this conluence of advertising and edito-rial is confusing: Where does the sales pitch end? Where does the editor take over?”

There is some evidence that original edi-torial content is perceived as more trust-worthy than advertisements provided by third parties (Cameron, 1994).If, by using this perceptual difference, advertisers actively manipulate editorial content— and this inluence is not acknowledged— consumers are deceived in their search for reliable product information.

In this latter sense, advertiser pressure falls under a larger ethical problem area: the increasing “blurring of advertising and editorial content” (Peeler and Guthrie, 2007).

Infomercials, advertorials, product placement, branded entertainment, cer-tain forms of public relations, and emerg-ing digital forms of communication (viral marketing, buzz marketing/seeding, blogger outreach) all potentially are ethi-cally problematic because of consumers’ inability to identify whether the informa-tion is sponsored (and as such, subject to appropriate attributions about intent and information value) or “objective” (not intentionally furthering commercial inter-ests; Spence and van Heekeren, 2005).

The blurring of editorial and adver-tising content may deceive even the “informed, skeptical, sophisticated con-sumer” (Preston, 2010), on whom much of modern consumer-interest regulation is based, because he or she does not have

a chance for an accurate assessment of source credibility.

Advertising practitioners may not fully appreciate these issues identiied by ethics scholars. There seems to be a gap between the enthusiasm of the proponents of editorial/advertising intermingling and the vigilance of ethics researchers. What is “economic censorship” (Baker, 1992), “advertiser pressure” (Soley and Craig, 1992) or “sponsor interference” (Just and Levine, 2000) for ethics academics seems to be value-neutral conceptualizations of “product placement in print” (Atkin-son, 1994; Fine, 2004), “entertainment/ advertising convergence” (Donaton, 2004) or “value-added media buy” (“Media Round Table,” 1990; Fahey, 1991; Hoyt, 1990) for some advertising practitioners.

The topic is all the more important today because media—especially ttional print media—are undergoing radi-cal transformation and are under severe economic pressure (Nyilasy, King, and Reid, 2011). It has been argued that cer-tain forms of media undergoing economic hardship are more willing to compromise on ethical norms than economically pow-erful players within a market (Soley and Craig, 1992; An and Bergen, 2007). Print media, particularly newspapers, therefore are prime candidates for increased acqui-escence to advertiser pressure.

For all these reasons, it is imperative that academic research give detailed and updated accounts of advertiser pressure.

The consequences of advertiser pressure are far-reaching; it has both ethical and managerial implications for both media and advertising organizations, let alone

millions of consumers. Perhaps surpris-ingly, despite the foremost importance of advertiser pressure, very little is known about the phenomenon in an empirically rigorous manner.

The purpose of the research reported in this article is to give a recent and com-prehensive update on the phenomenon, in the context of the newspaper industry. The contribution of the study is threefold:

• It takes a fresh look at both the extent to which advertiser pressure is present in the newspaper business and the fre-quency by which it occurs today. • It incorporates the investigation of

per-sonal ethical norms for handling adver-tiser pressure.

• It targets not only newspaper editors but newspaper advertising directors.

Although advertiser pressure is present in all media, the authors selected the con-text of newspapers for the present research because, arguably, newspapers represent the traditional elite of journalism. Thus, it is in newspapers that the consequences of advertiser pressure are both the most sali-ent and potsali-entially the most severe.

LITERATURE REvIEW: ADvERTISInG ETHICS AnD ADvERTISER PRESSURE Before a review of the targeted empirical literature on advertiser pressure, it makes sense to situate the subject in the broader theoretical and empirical tradition of advertising ethics.

Despite its importance, the topic of advertiser pressure on media, surpris-ingly, does not appear very frequently on the agenda of advertising-ethics research. It is telling that although advertiser inlu-ence on media editorial content has been proposed as a high-priority research topic (Hyman, Tansey, and Clark, 1994), only a handful of targeted studies on the sub-ject have been conducted to date. Further,

Advertiser pressure is widespread in newspapers;

despite economic threats, however, advertisers succeed

the topic does not appear in more gen-eral accounts of advertising practition-ers’ ethical views (Chen and Liu, 1998; Drumwright and Murphy, 2004; Hunt and Chonko, 1987; Rotzoll and Christians, 1980).

One possible explanation for this lack of salience is that it is not advertising agen-cies—but rather the advertisers them-selves—that exert pressure on media. Because practitioner surveys/interviews in advertising ethics traditionally have focused on agencies, the topic remains hidden from view.

The study of advertiser pressure also is dificult to situate within advertising eth-ics’ classic typologies. Although the ield of advertising ethics traditionally deals with either the “advertising message” or the “advertising business” (Drumwright and Murphy, 2009), advertiser pressure falls somewhere between those two topics. It clearly is an organizational ethics issue; however, it has an impact on consum-ers through the manipulation of editorial content.

In the macro-meso-micro typology of marketing ethics’ levels of analysis (Brink-mann, 2002; Victor and Cullen, 1988), and, in this last sense, it is a “personal eth-ics” problem (Shaver, 2003). Although the authors recognize all these relevant layers (also encompassed by Hunt and Vitell’s comprehensive marketing ethics model (2006), the present paper focuses on per-sonal ethical norms (Kohlberg, 1984) when explaining how media workers confront advertiser pressure.

Although there are numerous anec-dotal accounts of advertiser pressure affecting all media forms (Atkinson, 2004; Christians et al., 2009; Collins, 1992;

Fine, 2004; Gorman, 2010; Gremillion and Yates, 1997; Hickey, 1998; Hoyt, 1990; Ives, 2010; Knecht, 1997; Rappleye, 1998; Sanders and Holliday, 2005; Sutel, 2005; Underwood 1998a, 1998b), little system-atic empirical evidence has been pub-lished in academe.

The authors undertook an extensive search of research publications to identity studies on advertiser pressure on media. The step-by-step process started with searching research databases (i.e.,EBSCO Business Source Premier and Academic Research Premier, Emerald, Factiva) for the keywords of “advertiser pressure,” and “advertising” and “media” combined with “social pressure,” “censorship,” “self-censorship,” “ethics,” “corrupt prac-tices.” Next, the titles of papers in the con-tents of the main advertising journals (i.e.,

Journal of Advertising, Journal of Advertising Research, International Journal of Advertising

and Journal of Current Issues and Research in Advertising) were scanned for relevance. Finally, the literature review sections and references were read in the identiied papers for further literature. The authors focused the literature review on the most important papers, as evidenced by their highest citation levels or inherent research interest.

Systematic scholarly evidence comes in two forms on the topic: indirect and direct. Indirect evidence is based on the compari-son of editorial and advertising content. Studies in this group investigated whether there was a correlation between the fre-quency/quality of editorial coverage and the frequency of advertising (for the given advertiser/industry) in the media/vehicle

studied. The results were mixed. Some studies found a strong correlation and deduced the existence of successful adver-tiser pressure (Reuter and Zitzewitz, 2006; Rinallo and Basuroy, 2009; Williams, 1992). Others found no relationship (Rouner, Slater, Long, and Stapel, 2009; Poitras and Sutter, 2009).

Direct evidence is supplied by surveys among media workers. Soley and Craig’s “Advertiser Pressures on Newspapers: A Survey” in the Journal of Advertising (1992) proved that the phenomenon existed at that time. That paper also provided an estimate of the phenomenon’s spread in U.S. newspapers. The survey investigated its three facets:

• Inluence attempts—advertisers try-ing to include positive and exclude or manipulate negative stories

• Economic pressure—the threat to with-draw and actual withwith-drawal of advertis-ing from the medium

• Acquiescence—the extent to which newspapers cede to advertiser pressure through:

– complying to overt inluence

attempts,

– internalizing the pressure, and – self-censorship.

Findings showed that the majority of newspaper editors (in the 70- to 90-percent range) had experienced advertiser pres-sure in the form of both inluence attempts and threats of advertising withdrawal. Acquiescing to such overt pressure, how-ever, seemed to be much less common among editors.

Despite its importance, the topic of advertiser pressure

on media, surprisingly, does not appear very frequently

A more recent study (An and Bergen, 2007) surveyed advertising directors at daily newspapers using a scenario approach. Although the study conirmed the existence of ethical dilemmas around advertiser pressure, because of its use of hypothetical scenarios it did not directly report on the extent of the phenomenon and, therefore, is not directly comparable to Soley and Craig’s study (1992).

Magazines also have had their share of advertiser pressure. A survey reported in

Folio, a magazine for magazine manag-ers, reported that more than 40 percent of the editors surveyed had been instructed by an advertising director or publisher to do something that they believed signii-cantly compromised editorial (Howland, 1989). Acquiescence on the part of those editors, however, was signiicantly lower; according to the study, 60 percent of the editors said “no” to the inluence attempts. Another survey among farm-magazine writers and editors found that both inlu-ence attempts and threats to withdraw advertising were common (Hays and Reis-ner, 1990).

A replication of Soley and Craig’s 1992 study among television reporters and editors showed that advertiser pressure also was widespread in that medium (Soley, 1997). The majority of respond-ents reported that they had experienced inluence attempts and threats to with-draw advertising; however, much less actual withdrawal (44 percent) or suc-cessful pressurizing (40 percent) was reported. Two surveys conducted as part of the Project for Excellence in Journal-ism offered further support that a signii-cant number of television news directors encountered advertiser pressures (Just and Levine, 2000; Just, Levine, and Regan, 2001). These surveys examined only the “inluence attempts” dimension of advertiser pressure, stating that it was much more common to ask for favorable

coverage than attempting to prevent negative stories to appear. In contrast, a survey of television news directors found no difference between the frequency of pressure to report positive stories versus not to report negative ones (Price, 2003). Uniformly, 93 percent of the respondents said they had never felt the pressure to do either of these.

The aforementioned studies assessed the extent to which advertiser pressure was present in the media but left unanswered the question regarding how often the phe-nomenon happened. The only study that reported how many times pressure was exerted by advertisers on the medium is a 1994 survey of newspaper reporters cov-ering agricultural news (Reisner and Wal-ter, 1994). Results showed that advertiser pressure was not as frequent as anecdo-tal sources would have suggested: Even though prepublication threats to withdraw advertising were received almost every month (M = 11.5 per year), other forms of advertiser pressure (such as demands for coverage, M = 1.7; post-publication withdrawals, M = 0.1) occurred much less frequently.

RESEARCH QUESTIOnS AnD HYPOTHESES Based on the literature, the authors tested one research question and six hypotheses. The research question addressed both the

extent and frequency with which advertis-mon assumption of anecdotal sources: the proposition that smaller market news-papers are more susceptible to advertiser pressure than large newspapers. They for-mulated two hypotheses:

• Smaller newspapers are subject to more inluence attempts and economic pressure.

• Smaller newspapers are more likely to acquiesce to pressure.

The study had mixed results, con-cluding that there was no evidence that smaller newspapers received more pres-sure; however, at least on one measure of acquiescence—self-censorship—small newspapers tended to score higher.

The authors’ irst two hypotheses are as follows:

H1: Small-circulation newspapers are subject to more advertiser

Journalism ethics codes traditionally have advocated the maintenance of an impenetrable wall between editorial and advertising content. With the increasing acceptance of the market-oriented news-paper, however, the separation between editorial and advertising department no longer seems so absolute (Hoyt, 1990; Underwood, 1998a, 1998b).

about how advertising pressure will be handled than written (but all too vague) codes (Reisner and Walter, 1994). Indeed, general media-ethics research guidelines advocate the study of both explicit, written codes and personal ethical criteria (Chris-tians, Rotzoll, and Fackler, 1991).

There was only one study in the litera-ture that dealt with such personal ethical norms in the context of advertiser pressure (Howland, 1989). The Folio survey among magazine editors and advertising directors contained a seven-item scale about per-sonal ethical norms grounded in everyday journalistic practice. The study found that advertising directors seemingly were more permissive about how they handled adver-tiser pressure than editors. The authors’ third hypothesis is that the situation is the same at modern newspapers:

H3: At newspapers, advertising directors are more permissive in their personal ethical norms for handling advertising pressure than editors.

As small newspapers are hypothesized to be more prone to advertiser pressure and acquiescence, it is reasonable to assume there is also a difference in the personal ethical norms with which they handle such pressure. As small newspapers are considered economically more vulnerable (Soley and Craig, 1992), our hypothesis is that they are also more permissive in how they handle advertiser pressure. This sug-gests a fourth hypothesis:

H4: The employees of small news-papers are more permissive in their subjective guidelines for handling advertising pressure than those of large newspapers.

Personal ethical norms for advertiser rela-tions are not independent of the strength

of the advertiser pressure that the editorial people are forced to handle. In fact, there are a number of reasons why there may be a positive relationship between adver-tiser pressure strength and personal policy permissiveness.

On the one hand, it might be more dif-icult for newspaper workers to maintain traditional ethical values in an environ-ment that strongly discourages them to do so. Indeed, the pressures might be so strong that employees would handle the conlict by loosening some personal ethical norms. On the other hand, the causal low might work the other way, too: the percep-tion that newspaper workers are more per-missive might encourage some advertisers to exert more pressure on those newspa-pers. Further, as ethical norms—both per-sonal/implicit and explicitly stated—have the purpose of resisting some allegedly unethical behaviors, it follows that if these ethical norms are less strict, the pressure can be more successful.

Therefore, the authors’ inal two hypoth-eses are as follows:

H5: The presence of advertiser pres-sures—both inluence attempts and economic pressure—is posi-tively related to more permis-sive personal ethical norms.

H6: More permissive personal ethi-cal norms are positively related to acquiescence to advertiser pressure.

• Inluence attempts—whether advertis-ers attempted to inluence the inclusion, exclusion, and content of stories

• Economic pressure—whether adver-tisers threatened to withdraw or in fact withdrew their advertising from the newspaper

• Newspaper acquiescence—whether advertisers succeeded in pressuring the newspaper to modify its editorial content, or if the newspaper decided to exercise self-censorship.

One item from the Soley and Craig (1992) study (“Has there been pressure from within your paper to write or tailor news stories to please advertisers?”) was omitted from the current research because it was applicable to editors only, and thus it did not suit the broader approach of extending the study by the inclusion of advertising directors. The option of ask-ing the question of editors and advertis-ing directors in different ways also was rejected, because the intention was to keep the questionnaire uniform, allow-ing consistent comparisons across the two groups. Additional items were included to assess the strength of the different fac-ets of advertiser pressure, asking for the frequency with which the phenomena occurred during the past year.

The concept of personal ethical norms was measured by the scale developed by Howland in Folio (1989). Open-end ques-tions allowed respondents to include a more detailed description of their reac-tions to advertiser pressure and to specify the advertiser groups from which they had received the most attempts to inluence editorial content.

• The timeframe for measuring the rate of recurrence of advertiser pressure was expanded from a 2-month window to a year to allow greater variance.

• The visual layout of the questionnaire as posted on the Web site was simpliied, making the completion of the question-naire easier for respondents.

Sampling

A random sample of U.S. newspapers was drawn from the Editor and Publisher International Yearbook. “Large” newspa-pers were deined operationally as the “Top 100” daily newspapers listed by the Yearbook; all these newspapers were included in the sample. Further, a simple random sample of smaller newspapers (n = 100) was drawn from the rest of the listed newspapers (the cutoff point for the inclusion in the small category was 101,598 daily circulation). A similar sepa-ration of large and small newspapers at the 100,000 mark was used by Underwood and Stamm in their “Balancing Business with Journalism: Newsroom Policies at 12 West Coast Newspapers” in Journalism Quarterly (1992).

From the staff of each large newspaper, the managing editor, the national news editor, the regional editor, and the adver-tising director were selected. In the case of small papers, the managing editor and the advertising director were identiied. The sampling procedures yielded 392 e-mail addresses for large newspapers and 173 for small dailies.

Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected through a multimodal survey; respondents were invited through e-mails to go to a Web site and ill out the questionnaire. The Internet platform was chosen because it is an effective method to reach respondents who might be over-burdened by other, more traditional con-tact attempts (Schaefer and Dillman,

1993; Cook, Heath, and Thompson, 2000). Internet surveys also can be administered much faster than mail surveys because of instantaneous distribution and very high response speed, two factors in achiev-ing higher response rates (Illieva, Baron, and Healey, 2002). Internet-based surveys have been shown to be especially effective with audiences that have near-universal Internet-access (Couper, 2001). News-paper workers are a good it because they are savvy Internet users who often check e-mail and browse websites (Garrison, 2004).

To maximize response rate, a tailored design to survey administration was uti-lized (Dillman, 2000). An endorsement e-mail from a well-known veteran journal-ist—who was also the head of a credible newspaper management research center— was sent out to every respondent in the sample. The letter emphasized the impor-tance of participating in the study and notiied the respondents that the research-ers will soon contact them through e-mail. The invitation e-mail was sent out a few days after the endorsement letter and asked the recipients to participate in the survey. The letter contained a hyperlink to the opening webpage of the survey, which had been placed on UGA’s website prior to the mailings. The webpages included a brief introduction, a consent form, and the survey instrument itself. Complete ano-nymity was promised, aiming at minimiz-ing social desirability bias. A follow-up e-mail was sent 3 weeks later reminding the recipients to participate in the sur-vey. Finally, a thank you note followed 3 weeks later, asking non-respondents to visit the study website and ill out the questionnaire.

One hundred and one questionnaires were returned, of which 81 were com-pleted and useable. After excluding unde-liverable mailings, the adjusted response rate was 23.4 percent. This igure is within

the inter-quartile range (20 percent–46 percent) of mail business sample response rates, as evidenced by a recent meta-anal-ysis in organizational research (Cycyota and Harrison, 2006). Ethics topics are also known for lower response rates, with Hunt and Chonko (1987) reporting 17 per-cent. Non-response error was checked by comparing early and late responses on key variables (Armstrong and Overton, 1977). No signiicant differences were found.

FInDInGS

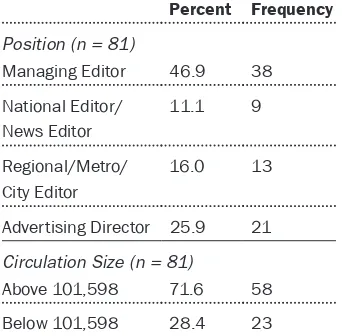

The majority of respondents were from the editorial side (managing editors 46.9 percent; national and news editors, 11.1 percent; regional and city editors, 16.0 per-cent), while 25.9 percent of the respond-ents were advertising directors (See Table 1). Nearly three-quarters (71.6 percent) of the responses were from large newspapers (top 100, above 101,598 daily circulation).

Advertiser Pressure: Inluence Attempts, Economic Pressure, and Acquiescence The different aspects advertiser pres-sure—the primary focus of R1—showed wide variation (See Table 2). Although

TABLE 1

Proile of national newspaper

Respondents

Circulation Size (n = 81)

Above 101,598 71.6 58

attempts to inluence the selection of sto-ries (reported by 64.2 percent of respond-ents), to inluence the content of stories (70.9 percent), and both threatening to withdraw advertising from the newspa-per (80.0 newspa-percent) and actual withdrawal (78.2 percent) were widespread, many fewer cases were reported about advertis-ers attempting to kill stories (37.2 percent) or newspapers giving in to overt pressure (23.4 percent) or practicing self-censorship (19.8 percent).

The number of times advertisers exert pressure on newspapers yearly also varied. Although equally widespread, inluence attempts (on story selection: M = 3.8 per year, SD = 8.69; on story content: M = 3.7, SD

= 7.49) seem to take place more frequently than the use of economic pressure (threat to withdraw: M = 2.2, SD = 3.01; withdrawal:

M = 1.0, SD = 1.38). In contrast, whereas few newspapers acquiesced to advertiser pres-sure, those that did seem to have given in relatively frequently (M = 1.9, SD = 1.87) compared to the number of attempts.

Personal Ethical norms for Advertiser Relations

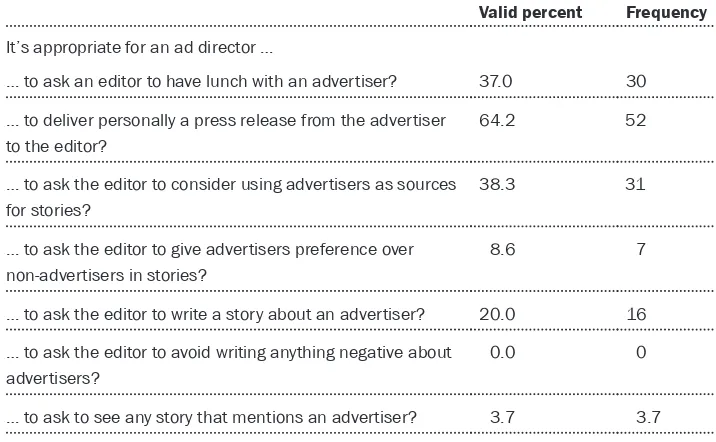

Personal ethical norms for newspaper-advertiser interaction also showed some variation (See Table 3). Although the majority of the respondents (64.2 per-cent) said that they thought that there was nothing wrong with the advertising director delivering a press release to the editor, asking the editor to have lunch with advertisers (37.0 percent) or to use advertisers as sources for stories are considered much less acceptable (38.3 percent).

A request for a story by the advertising director was adequate, according to 20 per-cent of the respondents. Preference over non-advertisers (8.6 percent) and advertis-ing-director access to stories before print-ing (3.7 percent) were even less favored.

TABLE 2

Advertiser Pressure: Inluence Attempts, Economic Pressure,

and Acquiescence

†valid

percent Frequency

number of times last year (mean)

number of times last year (standard deviation)

Inluence Attempts

Attempt to inluence story selection 64.2 52 3.8 8.69

Attempt to inluence content 70.9 56 3.7 7.49

Attempt to kill story 37.2 29 0.7 1.67

Economic Pressure

Threat to withdraw advertising 80.0 64 2.2 3.01

withdrawal of advertising 78.2 61 1.0 1.38

Acquiescence

Has any advertiser succeeded in inluencing news or features in your newspaper?

23.4 18 1.9 1.87

Our newspaper seldom runs stories which our advertisers would ind critical or harmful.

19.8 16 — —

† Percentages and frequencies in table relect respondents who answered “Yes” or “Agree.”

TABLE 3

Personal Ethical norms for Advertiser Relations

†valid percent Frequency It’s appropriate for an ad director …

… to ask an editor to have lunch with an advertiser? 37.0 30

… to deliver personally a press release from the advertiser to the editor?

64.2 52

… to ask the editor to consider using advertisers as sources for stories?

38.3 31

… to ask the editor to give advertisers preference over non-advertisers in stories?

8.6 7

… to ask the editor to write a story about an advertiser? 20.0 16

… to ask the editor to avoid writing anything negative about advertisers?

0.0 0

… to ask to see any story that mentions an advertiser? 3.7 3.7

The biggest taboo seemed to be asking the editor to avoid negative reporting about advertisers. No respondent considered it appropriate.

The Effect of Circulation Size on Advertiser Pressure

The irst hypothesis (H1) suggested that smaller newspapers were more likely to be subject to advertiser pressure than larger ones. A Z-test of proportions indi-cated there was limited support for the hypothesized relationship (See Table 4). The only variable that might be related to circulation size was threats of advertis-ing withdrawal (73.7 percent of the large newspaper respondents reporting threat vs. 95.7 percent of small newspapers) as indicated by a Z value of 2.013. Thus, there was only partial support for the hypothesis.

According to the second hypothesis (H2), smaller newspapers were more

prone to acquiescing to advertiser pres-sure. There was some support for this hypothesis (See the bottom part of Table 4). Direct acquiescence was sig-niicantly related to circulation size for the self-censorship outcome of “seldom running stories advertisers would ind critical or harmful” (39.1 percent of small newspapers reported self censorship vs. 12.1 percent of large newspapers, Z

value = 2.449), though circulation size was not related to advertiser’s perceived suc-cess in inluencing news coverage. Thus, there again was only partial support for H2.

Predictors of Personal Ethical norms: Employee Position and Circulation Size The third hypothesis (H3) predicted that advertising directors were more lenient in their approach to advertisers than editors and the authors’ data shows strong sup-port for that prediction.

All interpretable signiicance tests showed a difference between advertising directors and editors (See Table 5). Adver-tising directors were more likely to think that it is acceptable:

• to ask the editor to have lunch with the advertiser (ad directors: 71.4 percent vs. editors: 25.0 percent; Z value = 3.53,

df = 1, p < 0.05);

• to deliver a press release personally from advertiser to editor (ad directors: 90.5 percent vs. editors: 55.0 percent;

Z value = 2.654, df = 1, p < 0.05);

• to consider using advertisers as sources for stories (ad directors: 81.0 percent vs. editors: 23.3 percent; Z value = 4.415,

df = 1, p < 0.05); and

• to ask the editor to write a story about an advertiser (ad directors: 42.9 percent vs. editors: 11.9 percent; Z value = 2.771,

df = 1, p < 0.05).

The rest of the differences could be interpreted only qualitatively owing to the low cell counts; all but one relationship (one item showing zero variance), how-ever, were in the expected direction. H3 is accepted.

The authors also hypothesized (H4) that employees of small newspapers (both edi-tors and advertising direcedi-tors) were more permissive in their personal ethical norms prescribing normative behaviors with advertisers than large ones. And there was limited support for the hypothesis (See Table 6).

There were two items that were related to employee position; employees of small newspapers thought it was more acceptable to consider using advertisers as sources for stories than large newspa-per employees (small: 60.9 newspa-percent vs. large: 29.3 percent; Z value = 2.382, df = 1,

p < 0.05) and also to ask the editor to write a story about an advertiser (small: 39.1

TABLE 4

newspaper circulation size as an Indicator of Advertiser

Pressure Outcomes

†Large newspapers (%) (n = 58)

Small newspapers

(%) (n = 23) Z value

Outcome variable

Attempt to inluence story selection 58.6 (34) 78.3 (18) 1.46

Attempt to inluence content 71.9 (41) 68.2 (15) 0.214

Attempt to kill story 41.8 (23) 26.1 (6) 0.892

Threat to withdraw advertising 73.7 (42) 95.7 (22) 2.013*

withdrawal of advertising 74.5 (41) 87.0 (20) 1.245

Has any advertiser succeeded in inluencing news or features in your newspaper?

20.4 (11) 30.4 (7) 0.822

Our newspaper seldom runs stories which our advertisers would ind critical or harmful.

12.1 (7) 39.1 (9) 2.449*

* p < 0.05

percent vs. large: 12.3 percent; Z value = 2.449, df = 1, p < 0.05).

Other aspects of the personal ethi-cal norms concept were independent of newspaper size, including the rela-tionships that can be interpreted only

qualitatively. Thus, H4 had only limited support.

To test the inal two hypotheses (H5 and H6), the authors created scales for inluence attempts, economic pressure, acquiescence, and personal ethical norms.

Most scales reached an acceptable level of reliability (inluence attempts, α = 0.75;

economic pressure, α = 0.76; personal

ethical norms, α = 0.62). Acquiescence to

overt pressure and self-censorship had to be kept separate because of low scale

TABLE 5

Employee Position as an Indicator of Personal Policies for Advertiser Relations

†Editors (%) (n = 60)

Advertising Directors

(%) (n = 21) Z value

Outcome variable

It’s appropriate for an ad director …

… to ask an editor to have lunch with an advertiser? 25.0 (15) 71.4 (15) 3.53*

… to deliver personally a press release from the advertiser to the editor? 55.0 (33) 90.5 (19) 2.654* … to ask the editor to consider using advertisers as sources for stories? 23.3 (14) 81.0 (17) 4.415* … to ask the editor to give advertisers preference over nonadvertisers in stories? 5.0 (3) 19.0 (4) —‡

… to ask the editor to write a story about an advertiser? 11.9 (7) 42.9 (9) 2.771*

… to ask the editor to avoid writing anything negative about advertisers? 0.0 (0) 0.0 (0) —‡

… to ask to see any story that mentions an advertiser? 1.7 (1) 9.5 (2) —‡

*p < 0.05

† Percentages and frequencies in table relect respondents who answered “Yes.” Percentages are within-group. Within-group frequencies are in parentheses. All tests have 1 degree of freedom. ‡ The Z statistic cannot be interpreted because cells have counts of less than 5.

TABLE 6

newspaper circulation size as an Indicator of Personal Policies for Advertiser Relations

†Large

newspapers (%) (n = 58)

Small

newspapers (%)

(n = 23) Z value

Outcome variable

It’s appropriate for an ad director …

… to ask an editor to have lunch with an advertiser? 31.0 (18) 52.2 (12) 1.521

… to deliver personally a press release from the advertiser to the editor? 58.6 (34) 78.3 (18) 1.406 … to ask the editor to consider using advertisers as sources for stories? 29.3 (17) 60.9 (14) 2.382* … to ask the editor to give advertisers preference over nonadvertisers in stories? 3.4 (2) 21.7 (5) —‡

… to ask the editor to write a story about an advertiser? 12.3 (7) 39.1 (9) 2.449*

… to ask the editor to avoid writing anything negative about advertisers? 0.0 (0) 0.0 (0) —‡

… to ask to see any story that mentions an advertiser? 3.4 (2) 4.3 (1) —‡

*p < 0.05

reliability. Pearson correlations were cal-culated to test the hypotheses.

The analyses yielded mixed support for H5. There was a signiicant correla-tion between economic pressure and per-sonal policy permissiveness (r = 0.309, p

< 0.05), but inluence attempts were not related to personal ethical norms. Finally, H6 suggested that the more permissive newspaper workers are, the more likely advertisers will be successful with their inluence attempts. The hypothesis was rejected; neither success of overt attempts, nor the degree of self-censorship is related to personal policy permissiveness. the newspaper business; despite eco-nomic threats to withdraw advertising, however, the extent and frequency of advertisers succeeding with their inlu-ence attempts is relatively low.

• Smaller newspapers do not differ greatly from their larger counterparts with regard to any aspects of advertiser pressure.

• Advertising directors are more permis-sive in their personal ethical norms for handling advertiser pressure than editors.

• Employees of small newspapers are not much more permissive in their personal ethical norms than those of large papers. • The more economic pressure a news-paper receives (but not other forms of pressure), the more likely it is that the employees will have more permissive ethical norms for handling pressures.

Overall, these indings are in line with previous studies; advertiser pressure is widespread, but some of its forms are

more likely to occur than others. In accord-ance with the Soley and Craig (1992) study, inluence attempts on content and selection are more likely than attempts to kill stories. Similarly, advertisers do not always succeed with their inluence attempts; in fact, more often than not, they fail. Soley and Craig’s inding that adver-tiser pressure is to some extent independ-ent of circulation size also is replicated by the present study.

The authors’ data showed decreased levels of advertiser pressure (with the exception of one variable) when compared to the 1992 numbers. Overall, newspapers reported less pressure in the current study than their counterparts did nearly two decades ago, with an average negative dif-ference of 15.7 percent. The largest drop was in overt attempts to kill stories (34.2 percent). Self-censorship was the only var-iable that shows a higher value compared to the 1992 data (a 4.8-percent increase).

All personal policy permissiveness scores were lower in the present study than what Howland (1989) reported 21 years ago (an 18-percent decrease). It is important to note, however, that the Folio

study was conducted in the context of magazines, which are usually considered more prone to advertiser pressure than newspapers (Soley, 2002). Nevertheless, the negative difference offers further sup-port for the conclusion that advertiser pressure is decreasing.

This decrease in advertiser pressure might seem counterintuitive, especially when one considers anecdotal sources suggesting an actual increase (Ives, 2010; Sanders and Halliday, 2005; Sutel, 2005).

Similarly, the advertising industry’s increasing willingness to try to merge advertising and editorial content through advertorials, product placements, branded entertainment, and other forms of cross- over would suggest a contradictory pre-diction (Atkinson, 2004; Donaton, 2004; Fine, 2004; Gorman, 2010).

There are a number of possible reasons why the authors have found these some-what surprising results. One possibility is that advertiser pressure truly decreased, perhaps because newspapers have real-ized (and have also made their advertisers understand) that, even if in the short run it pays to allow some conluence of adver-tising and editorial content, the long-term interest of the newspaper industry is edi-torial integrity.

It is also possible that advertisers have become subtler in their inluence attempts (this may be supported by the inding that there is a large drop in overt attempts to kill stories) and instead they chose to let the newspapers censor themselves. This possibility is corroborated by the fact that self-censorship was the only measure that increased compared to the 1992 data. Reported self-censorship, however, still was much lower (19.8 percent) than other measures of advertiser pressure.

Finally, it is also possible that news people have become more cautious when discussing advertiser pressure. Moreover, as it is socially undesirable to admit to what traditionally is considered as some-thing opposing fundamental advertising and media ethics, they paint a rosier pic-ture than what reality is like. Although this explanation is possible, the fact that

Smaller newspapers do not differ greatly

from their larger counterparts with regard

the authors granted complete anonymity should have reduced that social desirabil-ity bias, if not eradicated it altogether.

IMPLICATIOnS FOR PRACTICE

The implications of this study for media and advertising are far-reaching. Wide-spread advertiser pressure—and even a limited extent of acquiescence to such pressures—has serious ethical conse-quences for newspapers.

Journalism’s special claim for elevated, professional status hinges on the idea of objective information dissemination and the altruistic ideal of serving the pub-lic’s right to know. If this ideal were to be curtailed by economic interests beyond acceptable ethical standards, the newspa-per industry would have to face a loss of its special status.

How managers at newspapers deal with advertising pressure, however, is much more than an ethical issue. Advertisers’ controversial requests also have economic ramiications for the future of newspapers, both directly and indirectly.

If newspapers can sell their advertising space only by also selling their editorial content to a certain extent, it evidently leads to the devaluation of their primary com-modity. It is an ethical concern for newspa-pers to preserve not only the integrity of the editorial content but economic self-interest.

Further, the perception that a newspa-per is biased in favor of certain advertis-ers—or that it has “sold out” to advertisers in general—very quickly can undermine its reputation among its primary consum-ers—the reading public. Loss in credibility and a negative image, in turn, may lead to diminished readership and eventually advertising revenue losses. It is the news-papers’ self-interest to stop the downward spiral and preserve editorial integrity, even if it means stiffer resistance to adver-tising pressure (Gorman, 2010).

One aspect of the successful manage-ment of advertiser pressure is the devel-opment of better corporate-, “meso-level” ethical norms and matching ethical cli-mate (Brinkmann, 2002; Victor and Cul-len, 1988). And, in fact, there seems to be a wide disagreement between editors and advertising directors about what is sub-jectively acceptable when interacting with advertisers and advertising pressure.

Closing the gap between the newsroom and the advertising department, in this sense, may be a step forward. Making the personal ethical norms explicit can clarify what is acceptable. Clear and com-mon understanding of advertiser pressure guidelines within newspapers or other media organizations can make resistance against ethically questionable advertiser requests easier. Although explicit poli-cies, in themselves, are not suficient—as evidence shows, individuals are far too willing to violate company policy when incentives are present (Beltramini, 1986)— they can be a way forward.

The current study also has implications for advertisers and advertising agencies. Although merging editorial and advertis-ing content has signiicant appeal for an advertising industry haunted by decreas-ing advertisdecreas-ing effectiveness, consumer cynicism, advertising avoidance, and media fragmentation, advocates of blur-ring editorial and advertising content need to realize that serious ethical issues are also involved in these practices.

It is in the advertising industry’s self-interest to clarify these issues, and lesh out under what speciic conditions it is acceptable to move into the content or, conversely, when it might be deceptive for the consumer.

A crucial distinction might lie, for instance, between entertainment (ictional) and editorial (nonictional) media content and, in the case of inherently nonictional

newspapers, between “hard” news and allegedly reporting objective evaluations of products and services (featured)—is different from product placement in ic-tional/entertainment contexts (embedded or placed); and the expectations of objec-tivity might even differ in the case of hard news versus features.

The advertising industry must develop speciic guidelines—much more detailed than the foregoing distinctions—in coop-eration with the various media forms to avoid the specter of an entire new species of commercial manipulation.

In short, advertiser pressure is no longer an ethical issue for only the media but for the advertising industry as well.

FUTURE RESEARCH DIRECTIOnS

One potential future research direction could clarify hypothesized differences between media in terms of the extent and frequency of advertiser pressure: the con-tention that magazines are more prone to advertiser pressure and especially acqui-escence should be tested (Zachary, 1992). Previous academic studies of advertiser pressure on television showed that the phenomenon was less common than it was in print; the use of different question-naire items, however, makes direct com-parisons dificult.

com-parisons possible, more research is needed about pressures on magazine and TV.

The other side of advertiser pressure— the advertisers themselves—also could be a good source of information for future research. In particular, details about pres-sure tactics could be investigated. This information would be especially useful as most of what we know about advertiser pressure is coming from media workers. Although some forms of advertiser pres-sure might be perceived by advertisers as controversial—and subject to social-desir-ability biases—advertisers can be quite open about some other variants.

For instance, anecdotal sources suggest that “advance-warning ethical norms”— guidelines requiring media to notify advertisers in advance of controversial stories to be published in the medium the advertisers buy space in—is one variety that advertisers are receptive to (Gorman, 2010; Ives, 2010; Sanders and Halliday, 2005; Sutel, 2005). The study of advertiser pressure from the advertisers’ perspec-tive could complement the existing direct knowledge about advertiser pressure, information that exclusively is based on surveys of media workers.

All of these research issues should be studied cross-culturally and in the con-text of American media. It is reasonable to speculate that media in different countries are pressured by advertisers, though such actions and outcomes are surely affected by speciic political, cultural, and eco-nomic conditions of indigenous market-ing/media systems.

Comparative research is needed to doc-ument the nature, extent, and frequency of advertiser pressure on media around the world.

GerGeLy nyiLasy is lecturer at the department of marketing

and management at the university of Melbourne in Australia. His main research interests are practitioner cognition and professionalism in marketing and advertising, advertising effects, market research methods, and ethical issues. His research has appeared in the Journal of Advertising, Journal of Advertising

Research, International Journal of Advertising, and

Admap. Before reentering the academic world, Gergely

was a planner at JwT, new york and head of R&D at Hall & Partners, new york.

Leonard n. reid is professor of advertising at the

university of Georgia. He is a former editor of the Journal

of Advertising and is a Fellow of the American Academy

of Advertising. His most recent research has focused on trust in advertising, practitioners’ theories of advertising, and pharmaceutical advertising. His research has appeared in the Journal of Advertising, International

Journal of Advertising, Journal of Current Issues and

Research in Advertising, and Journal of Advertising

Research.

REFEREncEs

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF MAGAZINE EDITORS.

“Guidelines for Editors and Publishers.”

Retrieved November 13, 2010, from [URL:

http://www.magazine.org/asme/asme_

guidelines/guidelines.aspx].

AMERICAN SOCIETY OF NEWSPAPER EDITORS.

“Statement of Principles.” Retrieved

Novem-ber 13, 2010, from [URL: http://asne.org/

article_view/articleid/325/asnes-statement-of-principles.aspx].

AN, S., and L. BERGEN. “Advertiser Pressure

on Daily Newspapers: A Survey of

Advertis-ing Sales Executives.” Journal of Advertising 36,

2 (2007): 111–121.

ARMSTRONG, J. S., and T. S. OVERTON. “Estimating

Nonresponse Bias in Mail Surveys.” Journal of

Marketing Research 14, 3 (1977): 396–402.

ASSOCIATED PRESS MANAGING EDITORS.

“State-ment of Ethical Principles.” Retrieved

Novem-ber 13, 2010, from [URL: http://www.apme.

com/?page=EthicsStatement].

ATKINSON, C. “Press Group Attacks Magazine

Product Placement: Wants ASME to Afirm Ban

on Commerce/Content Mixing.” AdAge.com,

September 27, 2004. Retrieved November 13,

2010, from [URL: at http://www.adage.com/

news.cms?newsId=41597].

BAKER, C. E. “Advertising and a Democratic

Press,” University of Pennsylvania Law Review

140, 6 (1992): 2097–2243.

BELTRAMINI, R. F. “Ethics and the Use of

Com-petitive Information Acquisition Strategies.”

Journal of Business Ethics 5, 4 (1986): 307–311.

BRINKMANN, J. “Business and Marketing Ethics:

Concepts, Approaches and Typologies.” Journal

of Business Ethics 41, 1/2 (2002): 159–177.

CAMERON, G. T. “Does Publicity Outperform

Advertising?: An Experimental Test of the

Third-Party Endorsement.” Journal of Public

Relations Research 6, 3 (1994): 185–205.

CHEN, A. W., and J. M. LIU. “Agency

Practi-tioners’ Perceptions of Professional Ethics in

Taiwan.” Journal of Business Ethics 17, 1 (1998):

15–23.

CHRISTIANS, C. G., K. M. ROTZOLL, and M.

FACKLER.Media Ethics: Cases and Moral

Reason-ing. New York: Longman, 1991.

CHRISTIANS, C. G., M. FACKLER, K. B. MCKEE,

P. J, KRESHEL, and R. H. WOODS JR.Media

Eth-ics: Cases and Moral Reasoning. New York:

Long-man, 2009.

COLLINS, R. K. L. Dictating Content: How

Advertising Pressure Can Corrupt a Free Press.

Washington, DC: Center for the Study of

COOK, C., F. HEATH, and R. L. THOMPSON. “A

Meta-Analysis of Response Rates in Web- or

Internet-Based Surveys.” Educational and

Psy-chological Measurement 60, 6 (2000): 821–836.

COUPER, M. P. “Web Surveys: A Review of

Issues and Approaches.” Public Opinion

Quar-terly 64, 4 (2001): 464–494.

CYCYOTA, C. S., and D. A. HARRISON. “What

(Not) to Expect When Surveying Executives: A

Meta-Analysis of Top Manager Response Rates

and Techniques over Time.” Organizational

Research Methods 9, 2 (2006): 133–160.

DILLMAN, D. A. Mail and Internet Surveys: The

Tailored Design Method. New York: J. Wiley, 2000.

DONATON, S.Madison & Vine: Why the

Entertain-ment and Advertising Industries Must Converge to

Survive. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2004.

DRUMWRIGHT, M. E., and P. E. MURPHY. “How

Advertising Practitioners View Ethics: Moral

Muteness, Moral Myopia, and Moral

Imagina-tion.” Journal of Advertising 33, 2 (2004): 7–24.

DRUMWRIGHT, M. E., and P. E. MURPHY. “The

Current State of Advertising Ethics: Industry

and Academic Perspectives.” Journal of

Advertis-ing 38, 1 (2009): 83–107.

FAHEY, A. “Cable TV Pushes Value-Added

Deals.” Advertising Age 62 (April 1, 1991): 34.

FINE, J. “Marketers Press for Product

Place-ment in Magazine Text: Call for End of Strict

Separation between Advertising and Editorial

Content.” AdAge.com, April 12, 2004. Retrieved

November 13, 2010, from [URL: http://www.

adage.com/news.cms?newsId=40248].

GARRISON, B. “Newspaper Journalists Use

E-Mail to Gather News.” Newspaper Research

Journal 25, 2 (2004): 58–69.

GORMAN, S. “L.A. Times Sells Disney Front

Page for Movie Ad.” Reuters.com, March 5,

2010. Retrieved November 16, 2010, from

[URL: http://www.reuters.com/assets/print?

aid=USTRE6250BL20100303].

GREMILLION, J., and K. YATES. “US Editors

Fight to Defend Magazine Content from

Adver-tiser Inluence.” Campaign (August 1, 1997): 23.

HAYS, R. G., and A. E. REISNER. “Feeling the

Heat from Advertisers: Farm Magazine Writers

and Ethical Pressures.” Journalism Quarterly 67,

4 (1990): 936–942.

HICKEY, N. “Money Lust: How Pressure for

Proit Is Perverting Journalism.” Columbia

Jour-nalism Review 37, 2 (1998): 28–36.

HOWLAND, J. “Ad vs. Edit: The Pressure

Mounts.” Folio 18, 12 (1989): 92–100.

HOYT, M. “When the Walls Come Tumbling

Down.” Columbia Journalism Review 28, 6 (1990):

35–40.

HUNT, S. D., and L. B. CHONKO. “Ethical

Prob-lems of Advertising Agency Executives.”

Jour-nal of Advertising 16, 4 (1987): 16–24.

HUNT, S. D., and S. J. VITELL. “The General

Theory of Marketing Ethics: A Revision and

Three Questions.” Journal of Macromarketing 26,

2 (2006): 143–153.

HYMAN, M. R., R. TANSEY, and J. W. CLARK.

“Research on Advertising Ethics: Past, Present,

and Future.” Journal of Advertising 23, 3 (1994):

5–15.

ILLIEVA, J., S. BARON, and N. M. HEALEY. “Online

Surveys in Marketing Research: Pros and

Cons.” International Journal of Market Research

44, 3 (2002): 361–376.

IVES, N. “The Ad/Edit Wall Worn Down to a

Warning Track.” Advertising Age, 81 (August 23,

2010): 3, 22.

JUST, M., and R. LEVINE. “Brought to You By…:

Sponsor Interference.” Columbia Journalism

Review 39, 4 (2000): 93.

JUST, M., R. LEVINE, and K. REGAN. “News

for Sale: Half of Stations Report Sponsor

Pres-sure on News Decisions.” Columbia Journalism

Review, 40, 4 (2001): 2–3.

KNECHT, B. G. “Hard Copy: Magazine

Adver-tisers Demand Prior Notice of ‘Offensive’

Arti-cles.” Wall Street Journal, April 30, 1997.

KOHLBERG, L. The Psychology of Moral

Develop-ment. San Francisco: Harper and Row, 1984.

MEDIA ROUND TABLE. “Value-Added, the New

Medium: Marketing Partnerships Taking on an

Increasing Importance with Media Owners.”

Advertising Age, 61 (April 9, 1990): S36, S38.

NYILASY, G., K. W. KING, and L. N. REID.

“Checking the Pulse of Print Media: Fifty Years

of Newspaper and Magazine Advertising

Research.” Journal of Advertising Research 51, 1

Supplement (2011): 167–175.

PEELER, L., and J. GUTHRIE. “Advertising and

Editorial Content: Laws, Ethics, and Market

Forces.” Journal of Mass Media Ethics 22, 4 (2007):

350–353.

POITRAS, M., and D. SUTTER. “Advertiser

Pres-sure and Control of the News: The Decline of

Muckracking Revisited.” Journal of Economic

Behavior & Organization 72, 3 (2009): 944–958.

PRESTON, I. L. “Interaction of Law and Ethics in

Matters of Advertisers’ Responsibility for

Pro-tecting Consumers.” Journal of Consumer Affairs

PRICE, C. J. “Interfering Owners or Meddling

Advertisers: How Network Television News

Correspondents Feel About Ownership and

Advertiser Inluence on News Stories.” Journal

of Media Economics 16, 3 (2003): 175–188.

RAPPLEYE, C. “Cracking the Church-State Wall:

Early Results of the Revolution at the Los

Ange-les Times.” Columbia Journalism Review 36, 5

(1998): 20, 23.

REISNER, A., and G. WALTER. “Journalists’

Views of Advertiser Pressures on Agricultural

News.” Journal of Agricultural and Environmental

Ethics 7, 2 (1994): 157–172.

REUTER, J., and E. ZITZEWITZ. “Do Ads

Inlu-ence Editors? Advertising and Bias in the

Finan-cial Media.” Quarterly Journal of Economics 121, 1

(2006): 197–227.

RINALLO, D., and S. BASUROY. “Does

Advertis-ing SpendAdvertis-ing Inluence Media Coverage of the

Advertiser?” Journal of Marketing 73, 6 (2009):

33–46.

ROTZOLL, K. B., and C. G. CHRISTIANS.

“Advertising Agency Practitioners’ Perceptions

of Ethical Decisions.” Journalism Quarterly 57, 3

(1980): 425–431.

ROUNER, D., M. SLATER, M. LONG, and L. STAPEL.

“The Relationship Between Editorial and

Advertising Content about Tobacco and

Alco-hol in United States Newspapers: An

Explora-tory Study.” Journalism & Mass Communication

Quarterly 86, 1 (2009): 103–118.

SANDERS, L., and J. HALLIDAY. “BP Institutes

‘Ad-Pull’ Policy for Print Publications.” Ad

Age.com, May 24, 2005. Retrieved November

16, 2010, from [URL: http://www.adage.com/

news.cms?newsId=45132].

SCHAEFER, D. R., and D. A. DILLMAN.

“Devel-opment of a Standard E-Mail Methodology:

Results of an Experiment.” Public Opinion

Quar-terly 62, 3 (1993): 378–397.

SHAVER, D. “Toward an Analytical Structure for

Evaluating the Ethical Content of Decisions by

Advertising Professionals.” Journal of Business

Ethics 48, 3 (2003): 291–300.

SHOEMAKER, P. J., and S. D. REESE. Mediating

the Message: Theories of Inluences on Mass Media

Content. New York: Longman, 1991.

SOCIETY OF PROFESSIONAL JOURNALISTS. “Code

of Ethics.” Retrieved November 13, 2010,

from [URL: http://www.spj.org/pdf/

ethicscode.pdf].

SOLEY, L. “‘The Power of the Press Has a Price’:

TV Reporters Talk About Advertiser Pressures.”

Extra!, (July/August 1997). Retrieved

Novem-ber 13, 2010, from [URL: http://www.fair.org/

extra/9707/ad-survey.html].

SOLEY, L. Censorship, Inc.: The Corporate Threat

to Free Speech in the United States. New York:

Monthy Review, 2002.

SOLEY, L. C., and R. L. CRAIG. “Advertiser

Pres-sures on Newspapers: A Survey.” Journal of

Advertising 21, 4 (1992): 1–10.

SPENCE, E. H., and B. VAN HEEKEREN.Advertising

Ethics. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice

Hall, 2005.

SUTEL, S. “Newspaper Editors Fret about

‘Shadow Ads.’” TheLedger.com, June 8,

2005. Retrieved November 16, 2010, from

[URL: http://www.theledger.com/apps/

pbcs.d11/article?AID=/20050608?NEWS/

506080329/1001/BUSINESS].

UNDERWOOD, D. “When MBAs Rule the

News-room.” Columbia Journalism Review 26, 6 (1998a):

23–30.

UNDERWOOD, D. “It’s Not Just L.A.” Columbia

Journalism Review 36, 5 (1998b): 24–26.

UNDERWOOD, D., and K. STAMM. “Balancing

Business with Journalism: Newsroom Policies

at 12 West Coast Newspapers.” Journalism

Quar-terly 69, 2 (1992): 301–317.

VICTOR, B., and J. B. CULLEN. “The

Organi-zational Bases of Ethical Work Climates.”

Administrative Science Quarterly 33, 1 (1988):

101–125.

WILLIAMS, W. S. “For Sale! Real Estate

Adver-tising and Editorial Decisions about Real Estate

News.” Newspaper Research Journal 13, 1/2

(1992): 160–169.

ZACHARY, G. P. “All the News? Many

Jour-nalists See a Growing Reluctance to Criticize

Advertisers.” Wall Street Journal, February 6,