i

Joint National/International Expanded

Programme on Immunization and

Vaccine-Preventable Disease

Surveillance Review

ii Joint National/International Expanded Programme on Immunization and Vaccine-Preventable Disease Surveillance Review, Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste

© World Health Organization 2017

Some rights reserved. This work is available under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO licence (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO; https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo).

Under the terms of this licence, you may copy, redistribute and adapt the work for non-commercial purposes, provided the work is appropriately cited, as indicated below. In any use of this work, there should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organization, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted. If you adapt the work, then you must license your work under the same or equivalent Creative Commons licence. If you create a translation of this work, you should add the following disclaimer along with the suggested citation: “This translation was not created by the World Health Organization (WHO). WHO is not responsible for the content or accuracy of this translation. The original English edition shall be the binding and authentic edition”.

Any mediation relating to disputes arising under the licence shall be conducted in accordance with the mediation rules of the World Intellectual Property Organization.

Suggested citation. Joint National/International Expanded Programme on Immunization and Vaccine-Preventable Disease Surveillance Review, Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste,New Delhi: World Health Organization, Regional Office for South-East Asia; 2017. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Cataloguing-in-Publication (CIP) data. CIP data are available at http://apps.who.int/iris.

Sales, rights and licensing. To purchase WHO publications, see http://apps.who.int/bookorders. To submit requests for commercial use and queries on rights and licensing, see http://www.who.int/about/licensing.

Third-party materials. If you wish to reuse material from this work that is attributed to a third party, such as tables, figures or images, it is your responsibility to determine whether permission is needed for that reuse and to obtain permission from the copyright holder. The risk of claims resulting from infringement of any third-party-owned component in the work rests solely with the user.

General disclaimers. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of WHO concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Dotted and dashed lines on maps represent approximate border lines for which there may not yet be full agreement. The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by WHO in preference to others of a similar nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters.

iii

4.1 Policies, strategies and service delivery ... 6

4.1.1 Major achievements and issues identified ...6

4.1.2 Recommendations ...7

4.2 Immunization supply chain management ... 7

4.2.1 Major achievements and issues identified ...7

4.2.2 Recommendations ...8

4.3 Programme monitoring and use of data ... 8

4.3.1 Major achievements and issues identified ...8

4.3.2 Recommendations ... 10

4.4 New vaccine introduction ... 10

4.4.1 Major achievements and issues identified ... 10

4.4.2 Recommendations ... 10

4.5 Communication and social mobilization ... 11

4.5.1 Major achievements and issues identified ... 11

4.5.2 Recommendations ... 11

4.6 VPD surveillance ... 11

4.6.1 Major achievements and major issues identified ... 11

4.6.2 Recommendations ... 14

4.7 Disease elimination and control ... 15

4.7.1 Polio eradication ... 15

4.7.1.1 Major achievements and major issues identified………. 16

4.7.1.2 Recommendations……….17

4.7.2 Measles elimination and rubella/CRS control ... 17

4.7.2.1 Major achievements and major issues identified……….………..18

4.7.2.2 Recommendations……….………19

4.7.3 Maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination ... 19

4.7.3.1 Major achievements and major issues identified……….……..19

4.7.3.2 Recommendations……….………21

4.8 Healthcare system ... 22

4.8.1 Major achievements and issues identified ... 23

iv

5 References ... 26

6 Annexes ... 27

6.1 Participants and team members ... 27

6.2 Team members and sites visited ... 29

6.3 List of background documents reviewed ... 32

v

Abbreviations and acronyms

AEFI adverse events following immunization

ANC antenatal care

AFP acute flaccid paralysis

BCG Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (tuberculosis) vaccine

bOPV bivalent OPV

BSP package of basic services

CHC community health centre

CRS congenital rubella syndrome

cVDPV circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus

DHIS District Health Information Software

DHS Demographic and Health Survey

DPHO district public health office

DT diphtheria tetanus toxoids, paediatric formulation

DTP diphtheria-tetanus toxoids and pertussis vaccine

DTP1 first dose of DTP

DTP3 third dose of DTP

DHO district health office

EPI Expanded Programme on Immunization

EVM effective vaccine management

FHR family health register

GVAP Global Vaccine Action Plan

HDI Human Development Index

HepB hepatitis B vaccine

HSS Healthy System Strengthening

vi HMIS Health Management Information System

HP health post

IPV inactivated polio vaccine

India the Republic of India

Indonesia the Republic of Indonesia

MCV1 the first dose of measles-containing vaccine

MHO municipal health office

MNT maternal and neonatal tetanus

MNTE maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination

MoH Ministry of Health

MPHO municipal public health office

MR measles-rubella vaccine

MR1 first dose of MR

MR2 second dose of MR

NCCPE National Certification Committee for Polio Eradication

NT neonatal tetanus

OPV oral polio vaccine

OPV2 OPV type 2

OPV3 third dose of OPV

PHC primary healthcare

PSF promotor saude familiar (family health promoter)

PV poliovirus

RCCPE Regional Certification Commission for Polio Eradication

RI routine immunization

SEAR South-East Asia Region

SEARO (WHO’s) Regional Office for South-East Asia

vii SOPs standard operating procedures

Td tetanus and diphtheria vaccine, adult/adolescent formulation

tOPV trivalent OPV

Timor-Leste the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste

TT tetanus toxoid

TT2+ second and subsequent doses of tetanus toxoid

UNICEF United Nations Children’s Fund

VAPP vaccine-associated paralytic polio

VPD vaccine-preventable disease

VVM vaccine vial monitor

WHA World Health Assembly

WHO World Health Organization

WPV wild poliovirus

WPV1 WPV type 1

WPV2 WPV type 2

WPV3 WPV type 3

viii

Acknowledgements

We would like to express our sincere gratitude and appreciation to Mr Jose dos Reis Magno, General Director of the Ministry of Health of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste (MoH); Mr Marcelo Amaral, National Director of the Directorate of Finance and Procurement Management, MoH; Mr Carlitos Correia Freitas, National Director of the Public Health Directorate, MoH; Dr Inesh Teodora Almeida da Silva, Director of Services of Diseases Control, MoH; Ms Isabel Maria Gomes, Director of Services of Community Health, MoH; and Dr Virna Martins Sam, President of the National Certification Committee for Polio Eradication.

We would also like to thank Dr Rajesh Panav, Representative of the World Health Organization (WHO) in the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste; Ms Desiree M. Jongsma,

Representative of the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) in the Democratic Republic of

Timor-Leste; and Dr Teodulo Clemente de J. Ximenes of the United States Agency for International Development.

1

1

Introduction

The Sixty-fifth World Health Assembly in May 2012 endorsed The Global Vaccine Action Plan (GVAP) based on an extensive consultation with countries and multiple stakeholders. In addition to articulating a global vision for immunization and outlining key strategies, the GVAP proposes five key goals for the Decade of Vaccines (2011– 2020): (1) to achieve a world free of polio; (2) to meet vaccination coverage targets; (3) to reduce child mortality; (4) to meet global and regional elimination targets; and (5) to develop and introduce new vaccines. Each Regional Member State is expected to further define specific targets and develop and implement action plans to advance the global goals. Through the Regional strategic plan and other initiatives, the World Health Organization’s (WHO’s) Regional Office for South-East Asia (SEARO) has identified specific targets for its Member States. Due to the commitment of national Expanded Programmes on Immunization (EPIs) and multiple partners, the Region has made significant progress towards achieving these goals, as exemplified by the certification of the Region as polio-free in March 2014 and by setting the goal to eliminate measles and control rubella and congenital rubella syndrome (CRS) by 2020. In addition, all countries of the South-East Asia Region (SEAR) have certified validation of maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination (MNTE) except the Republic of Indonesia (Indonesia) and the Republic of India in which MNTE remains to be validated in a few provinces or states. However, as noted in the GVAP, sustaining these achievements and meeting the current global and Regional objectives and targets will require committed country ownership, ensuring comprehensive and equitable vaccination coverage, sustainable health systems, and innovation to address new challenges as they arise.

Periodically reviewing how each country is meeting these requirements not only provides insight into the status of the national immunization programme (NIP) , but also allows best practices to be shared with other national EPIs . A comprehensive review becomes even more important in the context of large migration and cross-border movements. The last joint national and international review of the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste’s (Timor-Leste’s) EPI by the MoH and WHO was conducted in 2008 with a follow-up review in 2010. The current review was conducted from 1–13 March 2015 and provided the opportunity to objectively assess the progress and current status of the EPI and vaccine-preventable disease (VPD) surveillance programme as well as to provide recommendations for addressing the challenges faced in meeting national, Regional and global immunization goals and targets.

2.

Background

2 poverty line.(2) The infant mortality rate is 45 per 1 000 live births, while the maternal mortality rate is 557 per 100 000 live births.(3)

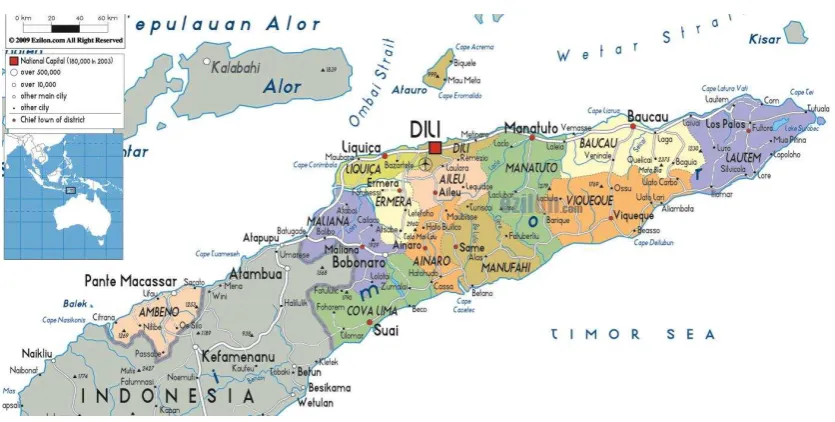

Administratively, the country is divided into 13 municipalities, 65 postos or administrative units, 442 sukus or villages, and 2 228 aldeias or hamlets (Figure 1). There is one national referral hospital in Dili, and five municipal hospitals that serve as referral centres. At the municipal level, health services are managed by the district health office (DHO) or municipal health office (MHO), and curative and preventive health services are provided at the administrative posto level in community health centres (CHCs) of which there are 67. In selected areas of the country, there are also health posts (HPs), of which there are 213.

A programme targeting remote populations and referred to as servisu integradu da saúde communitária (SISCa) or integrated community health services is implemented in 477 locations across the country. This programme establishes temporary fixed posts at locations which are distant from health facilities to provide a MoH-approved package of basic services (BSP) encompassing maternal health, child health (including immunization), communicable diseases, noncommunicable diseases, health promotion and environmental health.

Figure 1. Administrative map of Timor-Leste

3 reported to WHO as 77% in 2014, while national coverage with the first dose of measles-containing vaccine (MCV1) was reported as 74% for that same year.(2)

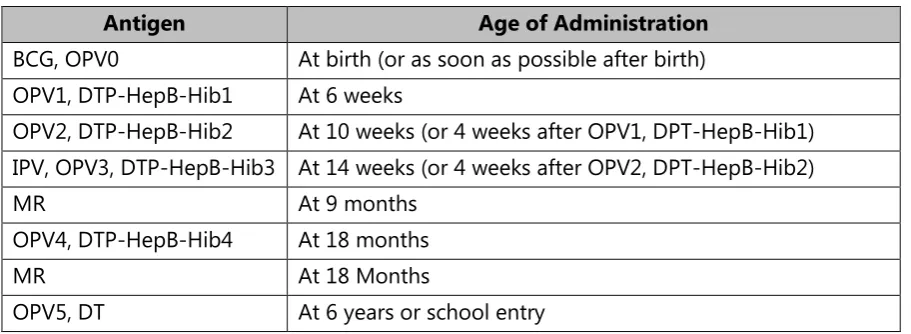

The current immunization schedule (Table 1) will be modified significantly as of September 2015 (Table 2). Anticipated changes include the addition of rubella and a second dose of measles vaccine administered as first dose measles-rubella vaccine (MR1) and second dose measles-rubella vaccine (MR2), the addition of a dose of inactivated polio vaccine (IPV), and the administration of a fifth dose of oral polio vaccine (OPV) as well as a diphtheria-tetanus toxoids (DT) booster at six years of age or school entry.

Table 1. Immunization schedule, Timor-Leste, March 2015

Antigen Age of Administration

BCG Birth to 1 year

DTP-HepB-Hib (3 doses) 6 weeks or 1st contact after 6 weeks, +1 month, +1 month OPV (birth dose + 3 doses) 0-2 weeks, 6 weeks or 1st contact after 6 weeks, +1 month,

+1 month

Measles (1 dose) 9 months

Tetanus Toxoid (TT) (5 doses)

Pregnant women: 1st contact, +1 month, +6 months, +1 year, + + 1 year.

Table 2. Immunization schedule, Timor-Leste, September 2015

Antigen Age of Administration

BCG, OPV0 At birth (or as soon as possible after birth) OPV1, DTP-HepB-Hib1 At 6 weeks

OPV2, DTP-HepB-Hib2 At 10 weeks (or 4 weeks after OPV1, DPT-HepB-Hib1) IPV, OPV3, DTP-HepB-Hib3 At 14 weeks (or 4 weeks after OPV2, DPT-HepB-Hib2)

MR At 9 months

OPV4, DTP-HepB-Hib4 At 18 months

MR At 18 Months

4

3.

Objectives and methodology

3.1

Objectives

The objectives of the review were discussed and agreed upon with the MoH prior to the mission. The overall objective of the review was to identify system strengths and weaknesses in view of making recommendations to improve these, with the intention of meeting country-level requirements for the global polio eradication endgame strategy by 2018 and meeting the SEAR measles elimination and rubella control target by 2020. Specific objectives of the review were:

To identify which children in Timor-Leste are not being fully immunized and the reasons for incomplete immunization. Reasons to be examined should include all aspects of programme implementation, including service delivery, community mobilization, vaccine hesitancy issues (if any), and the readiness of the country to introduce IPV, MR2, DTP and DT booster doses, all to be delivered through RI services.

To determine whether the VPD surveillance system meets national and global targets, and is able to detect VPD outbreaks.

To determine how immunization and VPD surveillance data recording, reporting and analysis are managed at various administrative levels and to determine whether the strategies being implemented to achieve measles elimination and rubella and CRS control are adequate to meet Regional targets by 2020.

To determine whether the strategies being implemented and current capacity are adequate to sustain the nation’s polio-free status and meet requirements of the polio endgame plan. This evaluation should include the quality of acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) surveillance, the extent of population immunity, the existence and comprehensiveness of polio outbreak or poliovirus importation rapid detection and response plan, the extent of laboratory containment and the functioning of polio oversight bodies, including the capacity and performance of the National Certification Committee for Poliomyelitis Eradication and the Committee on Laboratory Containment of Wild Poliovirus.

To determine which populations are not being fully immunized against tetanus and examine whether the strategies being implemented nationally are adequate to sustain MNTE. This determination should be made in the context of the 2015 global MNTE goal, the recent validation of Timor-Leste as having achieved MNTE and entered a maintenance phase for the control of maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNT), and the mandate of the EPI to vaccinate women against tetanus in order to prevent MNT.

5

3.2 Methodology

Nine teams were formed, each of one national and one international expert. One team reviewed the functioning of the EPI and VPD surveillance programme at national level, while the other eight teams each reviewed the EPI and VPD surveillance programme in one or two municipalities, resulting in review of the programmes in all 13 municipalities. Review team members are listed in Annex 1.

The teams assigned to municipalities visited the DHO/MHO, at least two CHCs and two HPs, interviewed healthcare providers and reviewed data and records. Community leaders and church representatives were also met. The team assigned to the national level met and interviewed officials from several MoH departments involved in immunization and surveillance, including the national laboratory, the central pharmacy and the institution in charge of training, as well as key partners supporting immunization and surveillance (a list of institutions and sites visited is provided in Annex 2).

All teams used the review protocol and guidelines developed prior to the mission, and were provided ahead of the review with a series of documents (listed in Annex 3) for an initial desk review.

After the visits, each team prepared written feedback on key findings and recommendations. These were consolidated and discussed with all team members. Core findings and recommendations were presented at a meeting on 12 March 2015 chaired by the Director General of Health and attended by national and municipal level officials. Municipality-specific reports were also drafted for later distribution to the DHO/MHOs.

4.

Findings and recommendations

RI services are integrated into the municipal primary healthcare framework which benefits from one of the best ratios of healthcare personnel to population in the Region. Approximately 50% of sukus have at least one HP, designed to be staffed by a doctor and nurse or midwife, and with access to the electrical grid approximately 40% of the time. RI services are delivered largely through fixed sites in CHCs and HPs, as well as through temporary sites coordinated by SISCa. National guidelines require that each suku have at least one SISCa clinic held monthly. Supplementary vaccination activities are also conducted.

In the past few years, a number of initiatives have been implemented to improve access to immunization services. These include prioritizing conducting SISCa clinics regularly, and assigning recently-trained doctors to CHCs and HPs to improve service delivery in rural areas. Nonetheless, further improvements to RI services could be achieved through equipping all HPs with appropriate cold chain equipment, ensuring that staff is trained in basic immunization skills, and offering more frequent vaccination sessions.

6

4.1

Policies, strategies and service delivery

4.1.1 Major achievements and issues identified

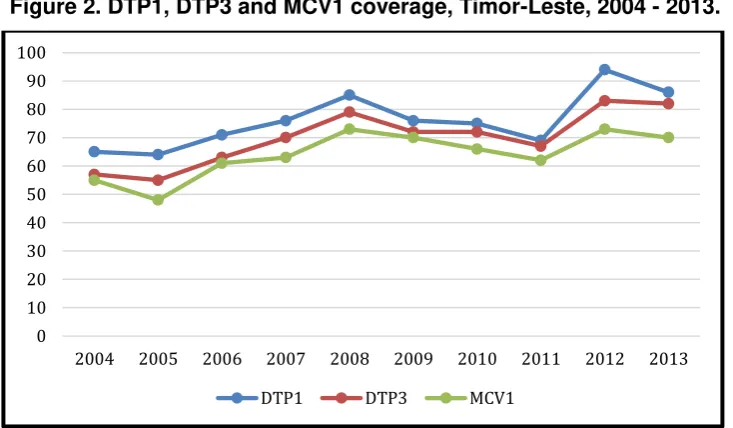

Despite these initiatives, RI coverage for DTP1, DTP3 and MCV1 has remained suboptimal (Figure 2). Currently, vaccinations administered through SISCa clinics and fixed sites do not reach all eligible children and women. Only half of the sukus in the country have functioning HPs and 70% of these HPs do not have cold chain equipment and therefore cannot provide regular vaccinations. The current guideline of one SISCa clinic per suku may be inadequate, especially for larger sukus or sukus with houses scattered over a large area. SISCa activities often take place at the HP/CHC or in the vicinity of existing health facilities, thus minimizing the extent to which these clinics truly improve access for remote and hard-to-reach populations, especially during the rainy season. In addition, the review revealed that there is no systematic defaulter tracking to reach children and women who missed immunization at SISCa or fixed site clinics. Many HPs provide antenatal care (ANC) and delivery services, but due to the absence of refrigerators, children born at these HPs are not offered Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) at birth or a birth dose of OPV.

Figure 2. DTP1, DTP3 and MCV1 coverage, Timor-Leste, 2004 - 2013.

Source: WHO. Immunization Country Profile. Available from

http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/coverages?c=TLS Accessed November 23, 2017

With the current coverage rates, the programme is at risk of not reaching or sustaining national, Regional and global targets for control and elimination of vaccine-preventable diseases. To be able to reach these targets, RI coverage as defined by DPT3 coverage needs to be a great deal higher than it currently is. Children will need to have a minimum of four contacts before their first birthday (not counting the birth doses for BCG and OPV). This will require scheduling SISCa clinics throughout the year, maximizing the output of fixed sites and adding supplementary visits to sukus currently receiving vaccination services through SISCa clinics to trace defaulters and reach the unreached.

2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013

7 Programme management capacity is also a concern at both national and subnational levels. The capacity of the health staff is suboptimal and requires rigorous enhancement to be able to drive the programme to achieve its objectives. There is also an inequitable distribution of health staff at DHO/MHO, CHC and HP levels and many staff, particularly the newly-recruited doctors, have not received any immunization-specific training. Lastly, supportive supervision is lacking, perhaps in part due to inadequate funding. Addressing these challenges will require support from national level or from partners.

4.1.2 Recommendations

(1) Increase immunization coverage as defined by DTP3 coverage to a level of 95% or higher to reach VPD control/elimination targets through

- Repositioning SISCa clinics within villages and communities, and

increasing mobile clinics/outreaches and outreach activities to reach the unreached.

- Developing a systematic strategy for defaulter tracking. This strategy

should be supported by clear guidelines and a budget allocation. (2) Ensure the quality of the immunization programme by

- Documenting and scaling up existing best practices within the health

system and as practised by health practitioners.

- Ensuring that regular supportive supervision takes place at all levels.

Quarterly reviews should be conducted at municipal level.

(3) Use the opportunities of the upcoming measles-rubella vaccine (MR) campaign and IPV introduction to address weaknesses in the routine immunization RI system services through staff training, communication and social mobilization, data quality assessment and other supportive activities

4.2

Immunization supply chain management

4.2.1 Major achievements and issues identified

The cold chain and vaccine storage and handling practices are of serious concern. Many of the health facilities visited contained outdated or broken cold chain equipment; about 70% of HPs did not have appropriate or functional cold chain equipment. Distribution of vaccine from the national level to municipalities and from municipalities to CHCs and HPs was perceived to be problematic.

8 from the national level. Without adequate vaccine management, the quality of the vaccines administered cannot be ensured.

In many CHCs visited during the review, it was observed that the refrigerators used have limited storage and cooling capacity. The required storage and cooling capacity needs will increase in the near future with the planned introduction of several new vaccines.

Recently, the MoH has procured cold chain equipment to be distributed to DHOs/MHOs, CHCs and HPs as part of a comprehensive effective vaccine management (EVM) improvement plan. In preparation for the installation of the new equipment, new standard operating procedures (SOPs) for vaccine management at all levels are being developed. Job aids to assist local managers in implementing the SOPs for cold chain equipment and vaccine management have also been developed along with a five-year plan for managing the cold chain. The new cold chain equipment has arrived in the country and will be distributed in the coming months.

Review teams also observed a high level of vaccine wastage: –approximately 50% for all vaccines, and up 80% for BCG. Ideally, wastage for pentavalent vaccine should not exceed 25%. The high levels of wastage in Timor-Leste seem attributable to the fact that WHO’s multi-dose vial policy is not fully implemented. (4)

During the review, there was an attempt to analyse national stocks-in-hand, incoming and distributed vaccines, and regular reserves for all vaccines. However, due to inconsistencies with the data collected, a thorough stock analysis could not be presented in this report.

4.2.2 Recommendations

(1) Expand cold chain to ensure all HPs have refrigerators that function well. (2) Accelerate implementation of the EVM implementation plan.

(3) Train staff at all levels to increase competency in EVM. (4) Establish a cold chain maintenance system at all levels.

(5) Ensure that national cold rooms are well maintained with temperature validation and that stock management practices are fully implemented. (6) Envisage the full implementation of the WHO multi-dose vial policy to

decrease the high wastage rates for vaccines for which the policy applies. (7) Make a complete inventory of vaccine stocks-in-hand at the national level,

and assess the national reserves of vaccines for 2015 and beyond.

4.3

Programme monitoring and use of data

4.3.1 Major achievements and issues identified

9 and 2014, the timeliness of the reporting has improved from 41% to 91%. At all levels, performance is monitored through coverage graphs for selected vaccines. Best practices include some facilities that calculate coverage levels by suku and aldeia levels to identify underserved communities. Booklets to record ANC and vaccination of mother and child are routinely distributed to mothers.

Population estimates based on the 2010 census (1) are used as target denominators for planning and coverage measurement. Some HPs and CHCs continue to use the family health register (FHR) data that have been collected and maintained by the promotor saude familiar (PSFs) or family health promoters and suku leaders. However, FHR-based denominators frequently conflict with census-projection denominators – the former being either higher or lower than the latter – resulting in confusion as to true coverage.

Data on coverage of key vaccines are analysed using monitoring graphs. Facilities often do not analyse their coverage data to identify inequities in access, underserved or unreached populations at the suku or aldeia level. Fully vaccinated children1 are reported to the national level, but these data are not plotted in monitoring graphs nor analysed locally. Although the national definition of “fully

vaccinated” includes the birth dose of OPV, it is unclear whether all children reported

as fully vaccinated have indeed received this dose of OPV. With the introduction of IPV and MR, the definition of “fully vaccinated” may require modification.

Concerns have been raised as to the quality of reported data. It is not clear whether and to what extent the quality of vaccination data collection is assessed during supervisory visits. No formal data quality assessment or dedicated vaccine coverage survey have been carried out in the past few years. However, in 2014 a large food and nutrition survey among nearly 2400 children aged 12–23 months confirmed the reported administrative coverage levels in 2013 for the third dose of pentavalent vaccine (82%) and and the first dose of measles vaccine (77%). The survey estimated the fully-vaccinated population of children in this age group at 74%.

EPI reporting tools, in particular registers and daily tally sheets, were not always available at the time of the review teams’ visits, and self-made books and sheets were being used in place of these. The registers and forms that are in use are out of date as they often do not reflect the current national immunization schedule. The registers and forms are not ready for recording the new vaccine doses scheduled to be introduced later in the year. A further complication is that, for DT and the fifth dose of OPV (both administered at school entry), current age groupings for data reporting will need to be adapted. The record books distributed to pregnant women also need updating to recognize TT doses that the pregnant woman has received in earlier pregnancies

Coverage data are analysed and published by the national level on a quarterly basis, which is inadequate to allow timely intervention to increase coverage when necessary. This analysis reveals widely heterogeneous subnational immunization coverage.

1

10 4.3.2 Recommendations

(1) Obtain reliable population data and EPI targets, preferentially using FHR data.

(2) Regularly analyse immunization coverage data to identify low performing areas. These can be identified through disaggregated analyses, and mapping. Action plans to increase coverage in areas of low immunization performance should be developed.

(3) Update recording and reporting forms (registers, daily/monthly reporting forms) to include new vaccines. (pentavalent, MR1 and MR2, IPV, DT) (4) Update home-based record books distributed to pregnant women with

relevant new vaccines for children and define the upper age at which the record book can be used to record child vaccines. For maternal TT dose recording and reporting, consider adding a reporting option “Fully protected in previous pregnancies”.

(5) Increase the quality and frequency of data reporting by conducting data quality assessments and increasing the frequency of reporting in DHIS-2. These actions should help to increase the use of data for action.

4.4

New vaccine introduction

4.4.1 Major achievements and issues identified

There are a number of new vaccines to be introduced and booster doses to be added to the national immunization schedule in 2015. These include MR1 and MR2 at 9 and 18 months of age respectively, IPV, a DTP booster dose at 18 months, and a DT booster dose at six years of age or school entry. The introduction of these new vaccines and booster doses represents a real opportunity to improve the immunization programme in Timor-Leste by identifying system weaknesses and implementing strategies to address these. However, without careful planning and preparation, adding these new vaccines over a short period of time can risk overwhelming the programme, especially in light of weaknesses previously alluded to in this report.

4.4.2 Recommendations

(1) Ensure good preparations for introductions of MR, IPV, and the DTP booster dose (given as pentavalent vaccine). Lead time for proper planning of the MR campaign should take into account current local capacity.

(2) Consider replacing the dose of single antigen measles vaccine currently given at 9 months of age with MR immediately after completion of the MR campaign, as well as giving MR at 18 months of age.

11

4.5

Communication and social mobilization

4.5.1 Major achievements and issues identified

The review revealed that the capacity for health promotion at national and subnational levels is low. Current communications and social mobilization activities are insufficient to lead to demand for immunization and therefore more investments are needed in this area. At the present time, there is no communication and social mobilization strategy or plan for the RI programme. Overall, the resources allocated for communications and social mobilization from the national budget are limited in view of the activities required. At the local level, suku and aldeia leaders, the promotor saude familiar (PSF) (family health promoter) and church groups are key to mobilizing communities, but their activities are not always coordinated with each other to ensure optimal community mobilization. priorities, and as an early warning system to identify VPD outbreaks. Surveillance data are also used to monitor progress towards specific goals of the immunization programme, such as polio eradication, measles elimination and rubella/CRS control, and MNTE.

4.6.1 Major achievements and major issues identified

The VPD Surveillance Department in Timor-Leste is under the Direction of Disease Control Services in the MoH. The VPD Surveillance Department is composed of three units including Data Management. Six staff work on VPD surveillance; however, this number is insufficient to conduct adequate supportive supervision as well as offer training for the municipalities and administrative postos. For example, in 2014, only three supportive supervision visits were conducted by the VPD surveillance team. A contributory factor may be lack of dedicated vehicles.

VPD surveillance guidelines were first published in Timor-Leste in 2005 and revised in 2008. These guidelines explain approaches to VPD surveillance, case definitions, what data should be collected and how suspected cases should be investigated, how to collect laboratory specimens and how to analyse, report and disseminate VPD surveillance data. Although these guidelines were distributed by the national surveillance unit, the review team noted that several municipalities and administrative postos did not have a copy of the guidelines available. Reporting forms were also missing from some locations.

13

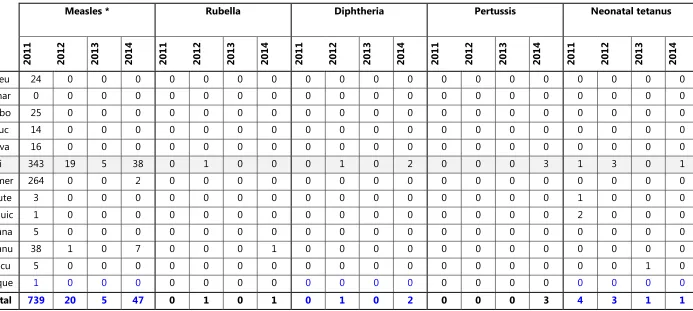

Table 3. Reported cases of VPD by municipality, Timor-Leste, 2011-2014

Measles * Rubella Diphtheria Pertussis Neonatal tetanus

2011 2012 2013 2014 2011 2012 2013 2014 2011 2012 2013 2014 2011 2012 2013 2014 2011 2012 2013 2014

Aileu 24 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Ainar 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Bobo 25 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Bauc 14 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Cova 16 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Dili 343 19 5 38 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 2 0 0 0 3 1 3 0 1

Ermer 264 0 0 2 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Laute 3 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0 0 0

Liquic 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 2 0 0 0

Mana 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Manu 38 1 0 7 0 0 0 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Oecu 5 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 1 0

Vique 1 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 0

Total 739 20 5 47 0 1 0 1 0 1 0 2 0 0 0 3 4 3 1 1

14 The aim of AFP surveillance is to detect as many AFP cases in the community as possible. WHO recommends that AFP surveillance systems detect at least two non-polio AFP cases per 100 000 population aged <15 years old annually to demonstrate adequate sensitivity. The estimated 2014 population aged <15 years old in Timor-Leste is 510 594, implying that Timor-Timor-Leste should detect at least 10 AFP cases every year. However, the annual non-polio AFP rate in the last five years has been<1 nationally. In 2014, it was 0.59. This problem reflects non-reporting of AFP cases from referral hospitals. There is a need to ensure systematic reporting of cases and to strengthen coordination and communication in the reporting units, especially between the district public health office (DPHO) and the municipal public health office (MPHO) and the referral hospitals.

Laboratory surveillance of VPDs

The country has structured public health laboratory services starting from CHC laboratories, municipal laboratories attached to the municipal reference hospital, and one national laboratory in Dili. The CHC laboratories are equipped to perform microscopic examinations for malaria and tuberculosis, and basic urine examinations. The municipal laboratories are equipped to perform haematological, biochemical and clinical pathology investigations. Samples are occasionally referred to the national hospital laboratory. In some of the referral hospitals visited, there is ongoing rotavirus surveillance with weekly sample transportation to the national laboratory. The national laboratory also performs biochemical tests and serological investigations for hepatitis, HIV, measles, rubella and Japanese encephalitis. The review found that clinical and laboratory staff had not been trained on sample collection, sample storage and transportation of specimens from cases of VPDs. There were also no guidelines in the facilities visited as to the collection, storage and transportation of laboratory samples from suspected VPD cases, and some of the clinicians lacked the skills required.

In summary, the major issues identified with regard to VPD surveillance were:

inadequate staff and resources at the central level for achieving high-quality surveillance

poor coordination between the surveillance unit of the MoH, the national hospital and referral hospitals

VPD surveillance guidelines, recording and reporting forms not present in several of the DPHO/MPHO and health facilities visited;

health staff at the DPHO/MPHO and health facilities levels inadequately trained on case detection based on case definitions;

no laboratory capacity at the municipality and administrative posto levels for sample collection, storage and transportation to the national laboratory.

4.6.2 Recommendations

(1) Designate a focal surveillance person at each health facility.

15 team) in each site under the leadership of the designated surveillance focal person.

(3) Train all health staff on VPD surveillance, particularly newly-recruited medical doctors. Training on venepuncture and laboratory sample collection should be included.

(4) Ensure that surveillance guidelines, recording and reporting forms are available in all health facilities.

(5) Build capacity among laboratory staff in referral hospitals and CHCs so that they are familiar with laboratory sample collection, storage and transportation.

(6) Conduct quarterly reviews of VPD surveillance performance at municipal level using standard WHO surveillance indicators.

(7) Ensure availability of transportation to allow staff to conduct surveillance activities.

4.7

Disease elimination and control

4.7.1 Polio eradication

Timor-Leste was certified polio-free on 27 March 2014, together with all other countries in WHO’s SEAR. This is a major public health achievement. Nonetheless, risk of wild poliovirus (WPV) re-introduction continues with circulation in the endemic countries of Afghanistan, Nigeria and Pakistan. The situation of importations is regularly reviewed by the WHO International Health Regulation (IHR 2005) Emergency Committee on Polio, which provides quarterly recommendations to the Director-General of WHO. The status of global polio eradication and performance levels in all countries is also discussed at the annual World Health Assembly (WHA).

The Global Polio Eradication Initiative’s Polio Eradication and Endgame Strategic

Plan 2013-2018, approved by the Executive Board of WHO in January 2013, calls for an important transition in the vaccines used to eradicate polio and requires the removal of all OPV in the long term. This will eliminate the rare risks of vaccine-associated paralytic polio (VAPP) and circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus (cVDPV). Currently, 145 countries use trivalent OPV (tOPV) to vaccinate children against polio in their RI programmes. tOPV contains all three poliovirus (PV) serotypes (1, 2 and 3), and the use of this vaccine has led to the eradication of WPV type 2 (WPV2), with the last case occurring in 1999. Given the risk that the type 2 component of tOPV poses to a world free of WPV2, tOPV will be replaced in routine programmes and supplementary immunization activities (SIAs) by bivalent oral polio vaccine (bOPV). bOPV contains type 1 and 3 serotypes only, to help stop transmission of WPV types 1 and 3 (WPV1 and WPV3), and to reduce the risk of VAPP and cVDPVs.

16

4.7.1.1 Major achievements and issues identified

The general situation of the immunization and surveillance systems and key programme strengths has already been described in previous sections of this report. To maintain its polio-free status, Timor-Leste offers four doses of OPV, including a birth dose to infants; has a framework for active surveillance for AFP cases and laboratory testing in the Regional Reference Laboratory in Thailand in place; has completed phase one laboratory containment of WPV infectious and potentially-infectious materials; and has established a polio outbreak preparedness and response plan. Oversight for maintaining polio-free status is the function of the National Certification Committee for Polio Eradication (NCCPE) under the Regional and global certification framework, with regular reporting requirements to the Regional Certification Commission for Polio Eradication (RCCPE).

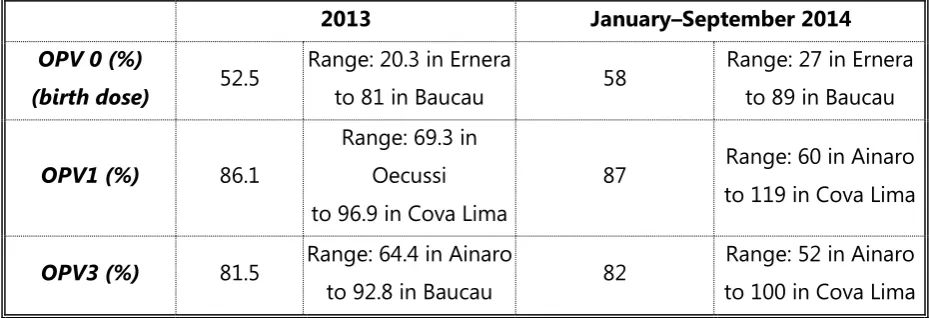

After gradually increasing coverage during previous years, reported national coverage with the third dose of OPV (OPV3) reached the minimum requirement of 80% in 2012, although it has declined slightly since that time.(2) There is, however, a large variance among municipalities, with the lowest coverage with OPV3 under 60% (Table 4). As such, it can be assumed that a substantial number of susceptible children have accumulated, and that population immunity is not high enough to prevent imported WPV from spreading.

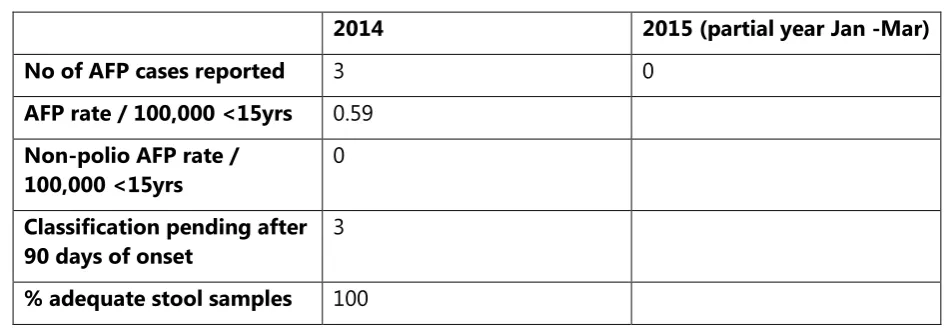

The key reporting standards for AFP surveillance were not met in 2014 or to date in 2015 (Table 5); as such, imported WPV or emergent cVDPV may not be detected in a timely manner. Delays should also be noted in the final classification of AFP cases. Other specific constraints in VPD surveillance have already been included in the report section titled “VPD surveillance”.

Table 4. National coverage with OPV and range of coverage by municipality by dose and year, 2013 and January – September 2014, Timor-Leste

17

Table 5. AFP surveillance indicators, 2014 and 2015, Timor-Leste

2014 2015 (partial year Jan -Mar)

No of AFP cases reported 3 0

% adequate stool samples 100

4.7.1.2 Recommendations

(1) Achieve and sustain universally high population immunity through RI coverage and periodic SIAs targeted to populations selected based on risk assessment. Consider vaccination of travellers to/from polio-affected countries.

(2) Achieve and sustain high-quality AFP surveillance including laboratory testing. (3) Update WPV and cVDPV preparedness plans.

(4) Sustain an active NCCPE and submit annual progress reports to the RCCPE.

(5) Introduce an IPV supplemental dose before the end of 2015. This introduction should focus particularly on health staff training and strategy communication for health workers, parents and communities.

(6) Document nationally the last WPV2

4.7.2 Measles elimination and rubella/CRS control

In September 2013, at the Sixty-sixth Session of the WHO Regional Committee Meeting for SEAR, the 11 Member States of the Region, including Timor-Leste, committed to eliminate measles and control rubella and CRS by 2020.

For several years prior to 2011, there were no confirmed measles cases in Timor-Leste. Confirmation testing of suspected measles cases began to be implemented in 2008–2009. In 2011, there was a major measles epidemic in the country. Eighty-seven measles cases were confirmed in six municipalities. The actual number of cases was many times greater (739 reported cases). Since then, there have been sporadic cases of confirmed measles, including 26 laboratory-confirmed cases in 2014. Confirmatory testing for suspected measles cases from 2011 to the present has identified a few rubella cases.

Population immunity of 92-95% is required to assure measles elimination, which is defined as no indigenous transmission of measles for more than a year. If measles disease is eliminated through the use of MR vaccine, rubella will be controlled.

18 campaign will take place during the summer of 2015. The purpose of the campaign is to ensure that all children aged 6 months to 14 years are vaccinated against rubella, while also providing a second dose of measles vaccine to those children who have already received a first dose.

If 95% two-dose MR coverage can be achieved in the years following the 2015 introduction of MR into Timor-Leste’s national childhood immunization schedule, it should be possible to reach the goal of measles elimination and rubella/CRS control by the targeted year of 2020.

In 2011, there was a national measles campaign in the country. The campaign was not a complete success. Difficult-to-access rural areas and densely populated areas in Dili were not well covered. Major issues were insufficient microplanning, lack of a phased implementation approach (which would have been able to maximize scarce monitoring and supervision capabilities), and only marginally-effective social mobilization. The major problem with the social mobilization effort was insufficient lead time in enlisting the support of the church hierarchy, the Ministry of Education, and local governmental authorities.

MR is safe and effective. As previously mentioned, to achieve the 2020 measles elimination and rubella/CRS control goal, Timor-Leste will introduce MR into its national immunization schedule in 2015, and will adjust the child immunization schedule so that each child will receive two doses of the vaccine instead of the single dose of single antigen measles vaccine currently offered by the programme. The second dose of MR will be given at 18 months of age.

In addition to 95% two-dose coverage with MR, achieving this elimination and control goal will require high-quality surveillance throughout the country, with laboratory confirmation of measles and rubella cases.

In summary, achieving the measles elimination and rubella/CRS control goal will require a very successful MR campaign, as well as increased immunization programme coverage following the campaign. A successful campaign and increased coverage following the campaign will require reinforcement of the present system for reaching the target population.

4.7.2.1 Major achievements and issues to be addressed

Surveillance for suspected measles is also in place down to the HP level. As explained in the VPD surveillance section of this report, health staff knows that they should look for and immediately report suspected measles cases. Blood samples will then need to be collected and tested in the national laboratory in Dili.

To access the expanded target age group and to achieve the target 95% coverage during the upcoming MR campaign, the vaccine and vaccination delivery system will require enhanced support for the following programme components:

microplanning to identify and target poorly vaccinated populations in rural areas;

special efforts to achieve high coverage in Dili Municipality, especially in the most densely populated areas;

19

enhanced social mobilization activities and support, particularly through the church hierarchy, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of State Administration and local governmental authorities;

expanded supervision and monitoring capability; enhanced cold chain support;

management of used injection material disposal.

4.7.2.2 Recommendations for the upcoming MR campaign

(1) Seek the highest level of political commitment possible for the campaign. (2) Establish a coordination mechanism and operational working groups. (3) Ensure good microplanning at all levels, particularly for rural areas that are

presently not well covered, and densely populated areas of Dili Municipality.

(4) Enlist the support of the church hierarchy in the country, the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of State Administration, and local governmental authorities, to mobilize and educate the national population about the campaign and its benefits.

(5) Coordinate with the Ministry of Education for planning that targets all school children.

(6) Adopt a phased campaign implementation schedule to maximize monitoring and supervision effectiveness.

(7) Ensure that the adverse event following immunization (AEFI) surveillance system is operational for the MR campaign.

4.7.3 Maternal and neonatal tetanus elimination

Elimination of maternal and neonatal tetanus (MNT) in Timor-Leste was confirmed in 2012 through the WHO formal validation process. This represents a very important public health success, and is in line with the goal for global elimination in 2015.

Prior to validation and to help raise immunization levels of second and subsequent doses of TT (TT2+), a national TT campaign targeting all women aged 12– 49 years (estimated to be 225 000) was organized. The first two rounds of the campaign were conducted in October and November 2008. A third nationwide round was conducted in June 2009. Of women of reproductive age, 87% received at least two TT doses after three rounds with municipal coverage ranging from 61% to 100% and only two municipalities reporting coverage below 80%. Among women of reproductive age (WRA), 74% received at least three doses of TT after the three rounds, with municipality coverage with three doses of TT varying from 48% to 96%. An additional SIA round was implemented in 2010 in three municipalities, in which 70% of WRA were reached in Alieu, 54% in Ainaro and 49% in Ermera municipalities.

20 4.7.3.1 Major achievements and issues identified

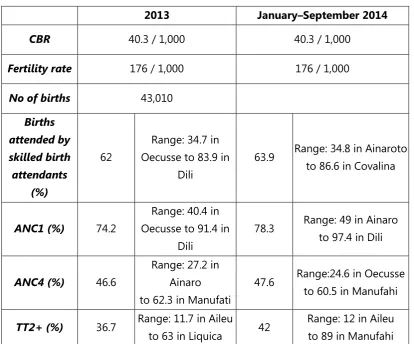

Similar to other estimations of vaccination coverage, TT coverage for WRA is subject to difficulties with data reliability. The way in which TT vaccinations are recorded in Timor-Leste suggests that coverage may actually be higher than what is estimated from reported data. Reported data indicate that TT2+ coverage in the country is about 40%; with great variance among municipalities. According to the 2010 Demographic and Health Survey (DHS), three-fourths of mothers with a live birth in the five years preceding the survey received two or more TT doses during their last pregnancy, and four-fifths were protected during their last delivery. The survey furthermore indicated that mothers in Manatuto were most likely to have received two or more TT doses (92%) and to have had their last delivery protected against NT (95%) compared with mothers in all other municipalities. TT coverage was lowest among mothers in Ermera and Ainaro. Reported TT2+ coverage in 2013 and the first nine months of 2014 indicate the lowest levels in Aileu.(3)

21

Table 6. Fertility, skilled birth attendant, antenatal care and TT2+ coverage, Timor-Leste, 2013 and January - September 2014

2013 January–September 2014

63.9 Range: 34.8 in Ainaroto to 86.6 in Covalina

Legend: CBR: Crude birth rate; ANC1: percentage of pregnant mothers attending a first antenatal clinic visit; ANC4: percentage of pregnant mothers attending a fourth antenatal clinic visit; TT2+; percentage of women of reproductive age who have received two or more doses of tetanus toxoid.

It is possible that TT2+ coverage has been generally underestimated in Timor-Leste as many women have, over the course of multiple pregnancies, received the maximum number of five tetanus toxoid doses and are not eligible to receive more. Nonetheless, MNT may still occur as TT2+ coverage may still be low in some areas. Furthermore, a large proportion of mothers still applies high-risk traditional substances to the umbilical cord stump. The percentage of all babies who are delivered in health facilities also remains low in remote areas. However, it is anticipated that the percentage of assisted deliveries will increase now that more skilled staff are available and the birth planning and preparedness package has been launched.

NT surveillance is currently integrated with VPD surveillance. However, the notification efficiency for NT surveillance is low. All cases should be investigated and responded to appropriately.

4.7.3.2 Recommendations

(1) Further increase and sustain high TT protection, through the following measures:

22

- Improve documentation of doses provided and investigate and

document extent of existing TT protection of pregnant women.

- Consider vaccinating WRA in remote areas during RI sessions.

- Develop a strategy to reach high coverage with the new DT booster

dose.

- Consider introducing TT (or tetanus and diphtheria vaccine,

adult/adolescent formulation (Td)) through school-based immunization. (2) Enhance surveillance through the following measures:

- Conduct an annual review of MNT-related data.

- Regularly supervise sites in order of priority (high to medium to low); all

health facilities should know NT case definition and report cases.

- Encourage maternal and neonatal death registration and audits.

- Encourage community-based surveillance through having health

volunteers track and report pregnant women, deliveries, maternal and neonatal deaths and midwives check on mothers and recently-born children during postnatal follow-up and home visits.

(3) Promote health facility/assisted/clean delivery, through the following measures:

- Explore means to improve access (for example, offering free

transportation, incentives, and developing and disseminating communication tools)

- Improve community awareness of safe and clean delivery and clean cord care through coordination with health volunteers, community leaders and influencers and use of IEC materials.

4.8

Healthcare system

A full review of the different components of the EPI and VPD surveillance programme requires an analysis of the healthcare system, taking into account relevant factors with regard to social determinants of health. The system’s management structure, human resources, access to capacity building, and fiscal management are all relevant lenses through which to examine the system.

Social determinants of health

The EPI and VPD surveillance programmes in Timor-Leste operate in a context challenged by a number of different factors, as outlined below.

Most communities reside in remote mountainous areas with generally difficult access and limited infrastructure.

The Human Development Index (HDI) value for 2012 is 0.576, ranking the country at 134 out of 187 countries and territories.(5)

It is estimated that 68.1% of Timor-Leste's population lives in multidimensional poverty, with an additional 18.2% ‘considered “vulnerable to multiple deprivations”.(6)

23

Improved access to drinking water, which supports sanitation and hygiene improvement, is low.

The adult literacy rate (that is to say, the percentage of the populated aged 15 years and above that is literate) is estimated to be approximately 58%.(7)

National Health Sector Strategic Plan 2011–2030

Timor-Leste’s National Health Sector Strategic Plan 2011–2030 (8) states that “The Strategic Plan provides the Ministry of Health with a framework for understanding its direction and moving forward with a sense of direction, purpose and guidance of activities and decisions required by key actors in the health sector for the next twenty

years”. An important expected result under the child health section of the document

is the reduction of under-5 and infant mortality from 61 to 21 and 44 to 15 per 1000 live births respectively. Increased access to high quality immunization services is identified as one of the four strategies to achieve these reductions in mortality, and achieving and maintaining immunization coverage of 90% by 2015 is anticipated.

The Fifth Constitutional Government (2012–2015) and Sixth Constitutional Government (2015–2017) in the national Strategic Development Plan 2011–2030 (9) and the National Health Sector Strategic Plan 2011–2030, (8) state that:

Over the next 5 years, the government will ensure that sukus with populations of 1500 to 2000 people located in very remote areas will be serviced by HPs delivering a comprehensive package of services.

The government will develop the necessary human resources to ensure at least one doctor, two nurses, two midwives and a laboratory technician in every suku of at least 2000 people.

The SISCa programme is to be fully implemented in every suku.

The government will seek to improve the provision and maintenance of appropriate transportation services.

The government will focus on improving maternal and child health.

Coverage of preventive and curative services for newborns, babies and children will be improved and expanded to decrease child mortality.

4.8.1 Major achievements and issues identified

The review found that, with few exceptions, the health staff is dedicated and understands its mission. Although knowledge and skills are still to be improved among the health staff, the currently available human resources in the health sector in Timor-Leste represent a real strength of the immunization and VPD surveillance programmes. Doctors who have recently completed training in Cuba have been sent throughout the municipalities, and will further strengthen human resources.

The current network of health institutions is well distributed geographically, although HPs remain to be opened in remote areas, as stipulated in the National Health Sector Strategic Plan 2011–2030.(8)

24 the Vaccine Alliance which has offered support for Health System Strengthening (HSS) funding during 2014-2018.

The recently implemented primary healthcare (PHC) programme offering a comprehensive service package and the initiative to strengthen the HMIS through the pilot DHIS-2 project should also be noted.

Despite these positive findings, the review noted challenges to be addressed. These included a lack of managerial capacity at national level for the EPI and the VPD surveillance programme. The EPI oversees a budget of approximately US $2 000 000, but, at national level, is staffed by a single manager and his assistant At the periphery, programme managers seemed preoccupied with the technical aspects rather than the managerial aspects of their positions. This may be due both to a lack of clarity in job descriptions as well as a lack of focus on building management capacity. A further challenge is ensuring optimal distribution of health staff in facilities – both in terms of skills and in terms of numbers. The review noted that some facilities were staffed with a fairly large number of health professionals, considering the population served, while other facilities were not staffed with a sufficient number for the population covered. High turnover of national and municipal-level staff remains a challenge.

This high turnover aggravates the lack of adequate knowledge and skills related to EPI and VPD surveillance found among health staff, including among the recently-trained physicians. Planning and costing, RI and vaccine management, VPD surveillance, laboratory, data management and health promotion were all identified as topic areas in which staff would benefit by training.

From a financial perspective, there is a lack of clarity on budget allocations and

“financial flow”. As mentioned in the recent health system analysis, the national health

policy/strategy/plan formulation, operation and budgeting processes appear disconnected. As a consequence, the budget allocation for the EPI and VPD surveillance programme does not reflect the prioritization of these programmes and appears inadequate.

Finally, there are concerns about the provision of sufficient funds for supervision and monitoring of staff, for equipment maintenance and repairs, for implementation of mobile clinics and outreach activities, and for health promotion. Overall, the health budget as a percentage of total government spending is noted to be declining.

4.8.2 Recommendations

(1) Reinforce the EPI and VPD surveillance functions at all levels to strengthen these two programmes through the steps outlined below.

- Upgrade/write the terms of reference and SOPs for key positions. - Increase EPI staff at the national level by reassigning staff.

- Ensure effective coordination and communication between different departments, units, hospitals and health facilities.

(2) Ensure an equitable distribution of health staff, taking into account the size of the target population and the immunization services to be delivered. Redistribute staff where necessary based on access and population criteria. (3) Ensure that health professionals, including new doctors, master best

25 planning and costing, midlevel management training, EVM, VPD surveillance, collection of laboratory samples, data management, health promotion and community mobilization.

(4) Enhance the ability of programmes at national and municipal levels to request and obtain adequate funding by

- rigorously costing and budgeting expenses;

- ensuring the development of proposals and advocacy to obtain local

budget support; and

- ensuring that municipalities develop their annual EPI plans in advance

26

5.

References

1. National Statistics Directorate (NSD), United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA). Population and Housing Census of Timor-Leste, 2010 [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2017 Nov 22]. Available from: https://www.mof.gov.tl/wp-content/uploads/2011/06/Publication-2-English-Web.pdf

2. WHO | Immunization Country Profile [Internet]. World Health Organization; [cited 2017 Nov 21]. Available from:

http://apps.who.int/immunization_monitoring/globalsummary/coverages?c=TLS

3. National Statistics Directorate - NSD/Timor-Leste, Ministry of Finance/Timor-Leste, ICF Macro. Timor-Leste Demographic and Health Survey 2009-10 [Internet]. 2010 [cited 2017 Nov 23]. Available from: https://dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR235/FR235.pdf

4. World Health Organization. HANDLING OF MULTI-DOSE VACCINE VIALS AFTER OPENING WHO Policy Statement: Multi-dose Vial Policy (MDVP) [Internet]. 2014 [cited 2017 Nov 23]. Available from: http://www.who.int/immunization/documents/en/

5. United Nations Development Programme. | Human Development Reports [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov 30]. Available from: http://hdr.undp.org/en/composite/trends

6. United Nations Development Programme. Human Development Report 2016 Human Development for Everyone Timor-Leste. [cited 2017 Nov 30]; Available from:

http://hdr.undp.org/sites/all/themes/hdr_theme/country-notes/TLS.pdf

7. UNICEF. Statistics | At a glance: Timor-Leste | UNICEF [Internet]. [cited 2017 Nov 30]. Available from: https://www.unicef.org/infobycountry/Timorleste_statistics.html

8. National Health Sector Strategic Plan 2011-2030 [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017 Nov 25]. Available from:

http://dev.nationalplanningcycles.org/sites/default/files/country_docs/Timor-Leste/attachment_1_c_timor_leste_nhssp_english_finish_1201_reduced.pdf

9. Timor-Leste Strategic Development Plan 2011-2030 [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2017 Nov 25]. Available from:

27

6.

Annexes

6.1

Participants and team members

National level

Mr Jose dos Reis Magno, General Director of MoH

Mr Marcelo Amaral, National Director of Directorate Finance and Procurement Management, MoH

Mr Carlitos Correia Freitas, National Director of Public Health Directorate, MoH

Dr Inesh Teodora Almeida da Silva, Director of Services of Diseases Control, MoH

Ms Isabel Maria Gomes, Director of Services of Community Health, MoH

Dr Virna Martins Sam, President of the NCCPE

Dr Jose Antonio Gusmao, Executive Director of National Hospital of Guido Valadares

Dr Odete Belo, Executive Director of SAMES

Dr Santina Gomes, Executive Director of National Laboratory

Ms Ivonia de Jesus Santos, Executive Director of INS

Dr Triana Oliveira, Head of MCH Department, MoH

Ms Maria Angela Varela Niha, Head of Surveillance Department, MoH

Mr Ivo C Lopes G, Head of HMIS Department, MoH

Mr Luis Correia, Head of Health Promotion Department, MoH

Mr Manuel Mausiry, EPI Manager

Municipality level

Mr Jose da Costa, Director of Health Services, Municipio Aileu

Ms Agustinha da C.S.S., Director of Health Services, Municipio Dili

Mr Victor Soares Martins, Director of Health Services, Municipio Bobonaro

Mr Bonifacio dos Reis, Director of Health Services, Municipio Ermera

28 Mr Hilariao Ramos, Director of Health Services, Municipio Ainaro

Mr Artur N.B. da Silva, Director of Health Services, Municipio Manatuto

Mr Bernardinho Amaral, Director of Health Services, Municipio Covalima

Mr Julio Pereira, Director of Health Services, Municipio Lautem

Mr Pedro Paulo Gomes, Director of Health Services, Municipio Liquisa

Mr Teofilo Julio Kehic Tilman, Director of Health Services, Municipio Manufahe

Mr Julio Soares, Director of Health Services, Municipio Vikeke

Ms Lucia Taeki, Director of Health Services, Municipio Oecusse

International Organizations

Dr Rajesh Panav, WHO Representative

Ms Desiree M. Jongsma, UNICEF Representative

Dr Teodulo Clemente de J. Ximenes, USAID

International team members National team members

Mr Abu Obeida Eltayeb, UNICEF, EAPRO Mr Aderito Docarmo, UNICEF

Mr David Basset, Consultant Mr Herminio Lelan, WHO

Dr Emma Lebo, CDC, Atlanta Mr Jose Lima, MoH

Mr Eric Laurent, Consultant Mr Leoneto Soares Pinto, WHO

Dr Hemlal Sharma, UNICEF, Timor-Leste Mr Manuel Mausiry, MoH

Dr Paul Bloem, IVB, WHO headquarters Ms Maria Niha, MoH

Dr Sigrun Roesel, IVD, WHO, SEARO Mr Mateus Cunha, WHO

Dr Sudath Peiris, WHO, Timor-Leste Mr Francisco Viana, MoH

29

6.2

Team members and sites visited

Team Team

members Admin level visited Institutions/Persons visited or met

C

General Director of Ministry of Health; National Director of Planning, Finance and

Procurement; National Director of Public Health; Director Services of Diseases Control;

Director Services of Community Health; President of the NCCPE; Executive Director of

National Hospital; Executive Director of SAMES; Executive Director of National Laboratory; Executive Director of INS; Head

of MCH Department; Head of Surveillance Department; Head of HMIS Department; Head of Health Promotion Department; EPI

Manager; WHO; UNICEF; USAID

Dili Municipality Dili DHS Office, CHC Formosa, CHC Comoro, HP Lemkari, HP Hera

Manatuto Municipality DHS Office, CHC Laklubar, HP Lei, CHC Laleia and HP Kairui

DHS Office, Baucau Referral Hospital, CHC Vemasse, HP Loilubo, CHC Venilale and HP

Bercoli

CHC Iliomar, HP Trilolo, HP Maluhira, HP Kakaven,HPLeuro DHS Office, CHC Lospalos,