Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=cbie20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 18 January 2016, At: 00:25

ISSN: 0007-4918 (Print) 1472-7234 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/cbie20

Indonesian universities in transition: catching up

and opening up

Hal Hill & Thee Kian Wie

To cite this article: Hal Hill & Thee Kian Wie (2012) Indonesian universities in transition: catching up and opening up, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies, 48:2, 229-251, DOI: 10.1080/00074918.2012.694156

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2012.694156

Published online: 27 Jul 2012.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 661

View related articles

ISSN 0007-4918 print/ISSN 1472-7234 online/12/020229-23 © 2012 Indonesia Project ANU http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2012.694156

INDONESIAN UNIVERSITIES IN TRANSITION:

CATCHING UP AND OPENING UP

Hal Hill* Thee Kian Wie*

Australian National University Indonesian Institute of Sciences (LIPI), Jakarta

Indonesia’s higher education system is changing rapidly: in 2010 there were about 5 million students, up from 2,000 in 1945. Effectively the tertiary system has four tiers, three of which are within the public sector. However, the system is increasingly private sector driven. The key themes of this paper on universities are rapid growth; overcoming the historical backlog; and the need for further fundamental reform. The quality of Indonesia’s tertiary institutions is highly variable. Governance structures and incentives regimes within the state universities are complex and obscure. The government both over-regulates and under-regulates. Major reforms are under way and increasing inancial resources are available.

Keywords: universities, education quality, accreditation

INTRODUCTION

This is a period of unprecedented and multi-dimensional growth and change in universities throughout the world.1 Individuals aspire to tertiary education

because it can enhance their lifetime earnings and broaden their employment horizons, and for personal enrichment as well as for social recognition. Govern-ments support the tertiary education sector for several reasons: as a response to community pressure for greater provision and easier access; as an equalising instrument, enhancing social and occupational mobility; for the social dividends above and beyond the personal calculus; and as a means of building a strong civil society.

Tertiary education is globalising rapidly. Like knowledge itself, universities have always been global in character, with faculty, students and ideas drawn from around the world. Traditionally, these lows were concentrated primarily among the advanced countries, but developing countries have become major players in

* This paper draws on research that was commissioned by the Australian Agency for Inter -national Development (AusAID), but the views expressed are entirely those of the authors. For comments on an earlier draft and much assistance with the research, we wish to thank Diastika Rahwidiati, Idauli Tamarin, Scott Guggenheim, Siwage Dharma Negara, Mayling Oey-Gardiner, Peter Gardiner and Colin Brown; we also express our gratitude to the many people interviewed during ieldwork in Jakarta and Bandung in 2011.

1 For recent analyses of universities in a global (albeit mainly US) perspective, see Wildavsky (2010).

global higher education over the past two decades. As their incomes have risen, the access of their citizens to higher education in the west has also expanded. Governments and universities in the rich economies have greatly facilitated the process, seeing a range of commercial and diplomatic advantages in opening up their universities.

Funding and incentives are central to these university dynamics. Govern -ments everywhere seek to balance broad-based participation with high-quality outcomes, alongside constrained iscal positions. Earlier principles of free uni -versal university education have had to be jettisoned. Most of the growth has to be privately funded. Thus the role for government is being transformed, from funder, owner and provider to enabler, facilitator, regulator and catalyst. This in turn requires a major rethink of higher education policy, and a major reform of ministries of education.

Indonesian universities relect these dynamics and policy issues. The country is a high-growth latecomer to university education, building on a historical under-investment in education at all levels in the colonial and early post-independence periods. There is great pressure on the government to expand higher education participation and to lift quality, in the context of a modest total expenditure of about 1.2% of GDP, of which just one-quarter is provided by the government (World Bank 2010: ix). Although private funding accounts for about three-quar -ters of the resources and most of the recent growth in enrolments, the government has only very gradually commenced the transition to a less heavily regulated environment that promotes the eficient and equitable allocation of resources. The country’s higher education sector also remains rather isolated from its global counterparts, although this, too, is beginning to change.

The next section of the paper examines Indonesia’s approach to education and education outcomes. We then analyse the international context and comparative experiences. After investigating the changing structure and policy environment of Indonesian universities, we focus on management and incentives within institu-tions. Finally, we discuss reform issues and options in light of what is generally regarded as international best practice.

INDONESIAN EDUCATION: AN OVERVIEW The educational landscape

Educational outcomes are a product of a country’s history, economy, culture and broad developmental philosophy. As a prelude to more detailed analysis we therefore provide a brief overview of how some of these factors have shaped Indonesian educational outcomes, both in general and at the tertiary level.2

2 Indonesia’s education system comprises pre-school, six years of primary education, and three years each of lower and upper secondary education. At the tertiary level, there are diploma, bachelor, master and doctoral programs, with the irst two of these taking from one to four years. Technical and vocational education and training (TVET) is an alternative to general education that can be undertaken at the secondary or the diploma level. For each level of education, a separate Islamic stream is also available.

Indonesia is, comparatively speaking, an educational latecomer and laggard, owing to colonial neglect and indifferent economic performance during the irst two decades of independence. According to the widely used Barro–Lee schooling attainment data set, 68% of the population aged 15 years and over in 1960 had no or incomplete primary education, and the average years of schooling for this pop-ulation was 1.6 (Barro and Lee 2011). The comparable igures for Indonesia’s low-to-middle income ASEAN neighbours were: Malaysia, 49.7% and 2.0 years; the Philippines, 25.6% and 4.2 years; and Thailand, 36.9% and 4.3 years. Educational disadvantage of this magnitude takes generations to overcome. This is notwith-standing oficial statements and plans emphasising the importance of education. In the 1970s the objective was to achieve universal primary education by around 1990, while in the 1980s it was to achieve universal junior secondary education by around 2005. More recently, in 2005, the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) passed an amendment to the Constitution that requires 20% of the government budget to be spent on education.

Three features have dominated Indonesia’s educational outcomes and poli-cies since 1970. First, the quantitative expansion has been very rapid at all lev -els, although, consistent with the conventional wisdom on education priorities, policy has focused on the primary and lower secondary levels. Second, oficial education policy has been egalitarian in its rhetoric but in practice – apart from the rapid expansion of low-quality public education – little attention has been paid to equity. Third, public expenditure on education has been low by compa-rable international standards, particularly at the tertiary level, where privately funded education has been the major driver of expansion. We now briely discuss each of these propositions.

Indonesia has made impressive gains in enrolments at secondary and tertiary levels over the past two decades.3 The strongest gains in both primary and sec-ondary education were made earlier, between 1975 and 1985. Primary enrolments are only now recovering from a decline following the Asian inancial crisis. The 2010 gross primary enrolment rate of 118% is still below the 1985 peak of 125%.4

In 2010, gross enrolment reached 92% at the junior secondary level, and 63% in senior secondary schools. Despite these gains, Indonesia lags behind most of its neighbours in the gross enrolment rate (GER) in its secondary schools. Its 2009 rate of 75%, while higher than Malaysia’s (68%), was below that of the Philippines (85%), Thailand (76%) and China (80%). It also trailed the East Asia and Paciic regional average of 76% and the OECD average of 101%.

3 Unless otherwise indicated, this section draws on material presented in Di Gropello, Kruse and Tandon (2011). Other data are from the World Bank’s World DataBank educa-tion statistics database, available at <http://databank.worldbank.org/data/home.aspx>, or from Index Mundi, available at <http://www.indexmundi.com/facts/indonesia/ school-enrollment>.

4 The net enrolment rate (NER) is the total enrolment of those in the appropriate age group for a given level (for example, 6–12-year-olds for primary level) as a percentage of the total population in that age group. The gross enrolment rate (GER) is the total enrolment at a given level, regardless of age, as a percentage of the population in the age group appropri-ate to that level. Hence the GER can be greappropri-ater than 100% but the NER cannot.

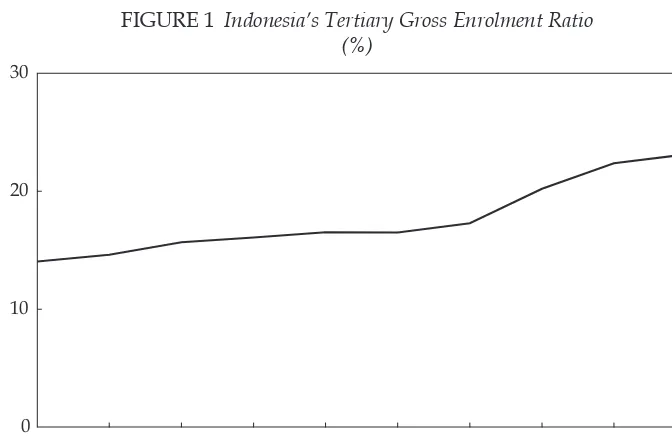

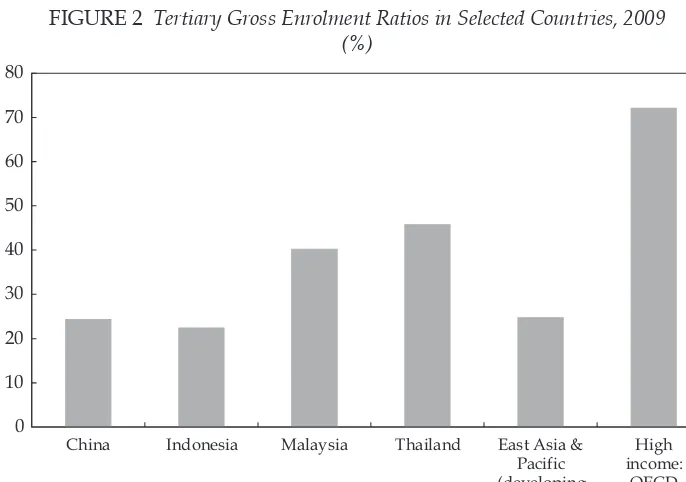

Indonesia has gradually increased its higher education enrolments over the past decade (igure 1). In 2001, its tertiary GER was 14.4%; by 2010 it had reached 23.1%. Like its secondary GER, Indonesia’s GER for higher education is lower than those of most of its neighbours (igure 2). The World Bank’s education sta -tistics (see footnote 3) indicate that Indonesia’s 2009 tertiary GER of 22.4% lagged behind those of China (24.4%), Malaysia (40.2%) and Thailand (45.8%). It was below the East Asia and Paciic regional average of 24.7% and far below the aver -age of 72.0% for high-income OECD countries. In Korea, the igure was 103.9%.

Despite progress on enrolment and an increased emphasis on the vocational training sub-sector, the overall educational attainment of Indonesia’s labour force remains fairly low. In 2010 just under 50% of Indonesia’s working popu-lation (deined as those aged 15 years and above who had worked in the past week) had completed only primary education or less, down from nearly 60% in 2000. Some 45% of the working population had completed high school (up from 38% in 2000). While the proportion with a higher education qualiication in 2010 – 6.3% – is substantially above the 2000 level of 3.6%, it is only one-quarter to one-third of the most recent (2007) igures provided by the World Bank Data -Bank for neighbouring countries such as Malaysia (20%) and the Philippines (28%).

As Di Gropello, Kruse and Tandon (2011: 160–8) show, Indonesia’s enrolment gains have not removed inequalities in access to education. Substantial spatial, gender and income disparities remain, especially in higher education. Rural–urban disparities are signiicantly larger than those of gender. Only 15% of those study -ing for a bachelor, master or doctoral degree in 2007 were rural students – less than one-third their share of the population. The participation of women has increased across all education levels. At the primary level, 53% of those enrolled in 2007 were

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 0

10 20 30

FIGURE 1 Indonesia’s Tertiary Gross Enrolment Ratio (%)

Source: World Bank, World DataBank, Education Statistics, <http://databank.worldbank.org/data/

home.aspx>.

female, while at the diploma level it was 56%. However, the proportion of women with bachelor degrees was still much lower than that for men (43% compared to 57%) in 2007, as it was for the percentage of the population aged 25 years and older with secondary education (24% compared to 31%). Current enrolments at the secondary level suggest that these disparities will disappear within a generation.

There are very large differences between the rich and the poor in access to all levels of education, particularly the tertiary level. More than 70% of those enrolled in universities in 2007 were in the richest quintile of the population. Students from the poorest three income quintiles made up only 10% of university graduates, and the poorest quintile accounted for less than 1% of those enrolled in university (Di Gropello, Kruse and Tandon 2011: 164). Poverty and low educational attainment are therefore strongly correlated.

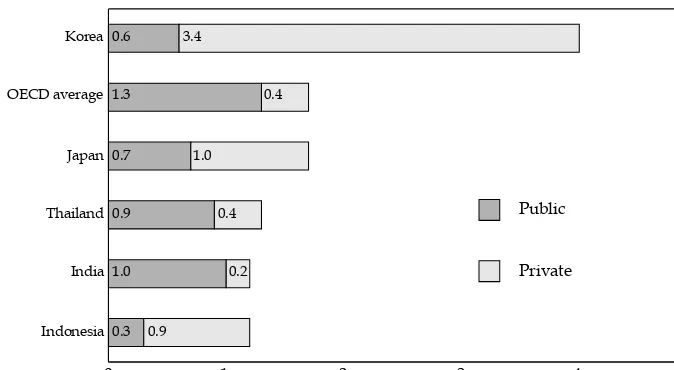

Public spending on education in Indonesia has risen substantially in recent years, boosted by the 2005 constitutional amendment on education spending. Consistent with the historical emphasis on primary and secondary education, public funding for tertiary education remains very modest, even by developing Asian standards. The Indonesian government currently spends the equivalent of about 0.3% of GDP on tertiary education (igure 3). This is about one-third of the corresponding percentage for India and Thailand, one-quarter of the OECD average, and one-seventh of the percentage for Malaysia (not shown). Thus, most of the funding for tertiary education in Indonesia comes from private sources, that is, tuition fees. Private funding is about three times the level of public funding, one of the highest ratios in developing Asia. In aggregate, however, Indonesia spends less on tertiary education than most of its neighbours.

China Indonesia Malaysia Thailand East Asia & Pacific (developing

only)

High income:

OECD

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80

FIGURE 2 Tertiary Gross Enrolment Ratios in Selected Countries, 2009 (%)

Source: World Bank, World Data Bank, Education statistics, <http://databank.worldbank.org/data/

home.aspx>.

Educational quality

Comparative international assessments such as the US-based Trends in Inter-national Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) and the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) show that Indonesia’s performance lags behind that of its neighbours other than the Philippines. The absence of any sig-niicant improvement over successive rounds of both series is cause for concern (Suryadarma and Sumarto 2011). The test scores indicate that quality needs to be strengthened. However, if the analysis takes account of differences in per capita GDP, the Indonesian record is comparatively good, as illustrated with reference to the PISA scores. Indonesia’s PISA scores are generally at least comparable with, and often higher than, those from countries with a similar per capita GDP.

Comparative quality at the tertiary level is dificult to measure. The two major international rankings are the World University Rankings published by the Times Higher Education Supplement (THES) and the Academic Rankings of World Uni-versities published by Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU).5 For what they are

worth, the 2008 World University Rankings included only three Indonesian uni-versities among the top 400 in the world: the University of Indonesia (UI) was ranked 287th, Bandung Institute of Technology (ITB) was 315th, and Universitas

Gadjah Mada (UGM) 316th. The rankings do luctuate from year to year, how

-ever. In some other recent years, no Indonesian universities appear in the top 400. According to the SJTU survey, no Indonesian university is placed within

5 Both rankings use objective and subjective criteria. The THES rankings, which com-menced in 2004, focus most heavily on international reputation. The SJTU rankings, which started in 2003, use objective indicators exclusively, related to the academic and research performance of faculty and alumni.

FIGURE 3 Public and Private Spending on Tertiary Education as a Share of GDP (%)

Source: World Bank (2010: 11, igure 2.3, citing UNESCO, World Education Indicators 2007). Figures

relect estimates for 2004–05. Indonesian igure is from 2009 budget. Indonesia

India Thailand Japan OECD average Korea

0 1 2 3 4 5

0.3 0.9

1.0 0.2

0.9 0.4

0.7 1.0

1.3 0.4

0.6 3.4

Public

Private

the top 100 institutions in Asia. Various comparative assessments conirm these general conclusions. Suryadarma, Pomeroy and Tanuwidjaja (2011) conclude, on the basis of an examination of the Social Sciences Citation Index database for the period 1956–2011, that only about 12% of social science research publications on Indonesia were authored by researchers based in-country. This was the lowest share among the seven major developing countries included in their compari-son, and about half of the corresponding igures for China (21%) and India (25%). Sumarto (2011) conirms these indings: a search of the ‘Econlit’ database showed that, among the articles published in English on the Indonesian economy in all refereed journals over the period 1980–2000, the 10 most published authors were all foreigners.

The origins of tertiary education

Although the country’s oldest university, UI, technically dates its origins to 1849,6 in practice Indonesia’s university system is almost entirely a creation of the sec-ond half of the 20th century (Buchori and Malik 2004; Welch 2011). In this respect,

Indonesia’s colonial experience lags behind those of India and the Philippines, for example. Three of the country’s other leading universities – Airlangga University (Unair) in Surabaya, the Bogor Agricultural Institute (IPB) and ITB – also date their origins to the establishment of single faculties or schools in the 1920s, during the Dutch colonial era. The irst post-independence university was UGM, located in Yogyakarta. State universities were then progressively established in the major provinces in the 1950s and 1960s, albeit with grossly inadequate funding.

During the colonial period, the faculty consisted almost exclusively of profes-sors from the Netherlands, teaching that country’s curriculum. The standards were high, in general comparable with those of the leading home institutions. The language of instruction was Dutch, but these institutions were open to the Dutch (including Eurasians) and to qualiied ethnic Chinese and indigenous Indonesian students – mainly from the privileged priyayi class – who had graduated from the Dutch language senior high schools.7 The Dutch academic community, which had

left Indonesia during the Japanese occupation, returned in the late 1940s. How -ever, Dutch academics progressively left in the course of the 1950s, as bilateral relations deteriorated in response to the festering dispute about the status of West Irian (now comprising the provinces of West Papua and Papua). By the late 1950s, with the switch to Indonesian as the language of instruction, the Dutch academic community had totally disappeared

6 UI’s 1849 origins are based on the establishment in Jakarta in that year of the Dokter Jawa School (School tot Opleiding van Inlandse Artsen or Stovia, School for the Training of Indigenous Physicians), which eventually became the university’s faculty of medicine in the late 1940s.

7 During the period 1920–40, fewer than 1,500 Indonesian students had qualiied to enter a tertiary institution; only 230 had graduated from Indonesian tertiary institutions; and just 344 had graduated from universities in the Netherlands (Booth 1989: 118).

UNIVERSITIES: THE GLOBAL CONTEXT Issues and trends

Higher education has historically been an international activity, with the great centres of learning attracting scholars and students from around the world. The number of people participating in the global delivery and receipt of higher educa-tion has risen rapidly over the past two decades. According to OECD estimates (OECD 2008a, 2008b), there were about 120 million university students in 2007, of whom about 3 million were undertaking education abroad. The US was the largest host country, with about 20% of the total, followed by the UK, Germany, France and Australia. Students from Asia accounted for the largest proportion of foreign students, led by China (457,000), India (162,000) and Korea (107,000). Indonesia, with 33,500 students, ranked low at number 20.8

There is much discussion about the prerequisites for the creation of high-class universities. Leadership, vision and resources are central. The consensus is that at least three factors are essential (Salmi 2009). First, there must be a high concen -tration of talent, based on a capacity to attract the best faculty and students. By deinition, this will be on a global scale, with at least 30% international faculty and 20% international students regarded as useful rules of thumb in rich coun-tries. Moreover, top universities typically have a high proportion of high-quality graduate students enmeshed in faculty research activities. Second, the universi-ties need to be well resourced. US expenditure (public plus private) on higher education in 2008 was about 2.7% of GDP, more than twice the proportion spent by the EU21 (1.3%) (OECD 2011a: 231.9 The top US universities (which are

over-whelmingly private) are well resourced, with endowments per student about 40 times the level in publicly funded US universities. A third factor is high-quality university governance, which typically features autonomy from government and political pressures, incentives for high performance, and a competitive spirit. Most of the top universities have evolved over decades or even centuries, and establishing top-class universities de novo is very expensive, with estimates rang-ing up to a billion dollars (Economist, 27/3/2010).

Several attributes supportive of high university quality that are implicit in the above analysis deserve emphasis. The irst is mobility within and between coun -tries, including the ability to attract the best faculty and students domestically and internationally. This in turn requires at the very least that regulatory barriers such as visa regulations are minimal.10 A second attribute relates to governance and

independence from governments. Aghion et al. (2010: 10), for example, test the hypothesis that ‘a combination of autonomy and competition makes universities

8 The OECD estimates appear to under-state the stock of Indonesian students abroad. Al-though accurate igures are not available, the number is Al-thought to be about 60,000. 9 The EU21 average is ‘the unweighted mean of the data values of the 21 OECD countries that are members of the European Union for which data are available or can be estimated. These 21 countries are Austria, Belgium, the Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia, the Slovak Republic, Spain, Sweden and the United Kingdom’ (OECD 2011a: 26).

10 To quote Salmi (2009: 21), ‘tertiary education institutions in countries where there is little internal mobility of students and faculty are at risk of academic inbreeding’.

more productive’. They conclude that increases in a university’s expenditure gen-erate greater output – as measured by patents or publications – if the univer-sity has greater autonomy and faces more competition. They therefore propose ‘increased reliance on competitive grants, enhanced competition for faculty and students (promoted by reforms that increase mobility)’, and competition against yardsticks based on various assessment exercises (Aghion et al. 2010: 7). A third key attribute is the presence of arms-length, independent processes for review of all aspects of university operations, including appointments, promotions, aca-demic output and resource allocation. Indeed, the president of a leading US uni-versity observed that ‘the bedrock of uniuni-versity quality in the United States is peer review’ (quoted in Salmi 2009: 59).

Country experiences

Developing country tertiary education experiences vary enormously, and it is beyond the scope of this paper to survey them. However, a few key lessons from selected Asian countries are salutary.

In the case of China, there has been a major commitment to tertiary education since the 1990s (Li et al. 2011). Undergraduate and graduate student enrolments have been growing at 30% per annum. China now produces three times as many PhD graduates in science and engineering as the US, although on a per capita stock basis the US still leads. Much of the increased government spending has been channelled into the 10 elite universities, which select the top students nation-wide through national entrance exams. Alongside this quantitative expansion is the push for quality, with emphasis on objective indicators such as international publications, citations and cooperation. There is a strong focus on science and engineering, with these ields constituting 41.3% of enrolments, compared with an economics and management share of 23.3%. As a result, China’s share of pub -lished output in the sciences is rising quickly, from 14.5% of Asian science and engineering articles in 1998 to 22.4% in 2003 (Li et al. 2011: 523–4).

The Indian record is surprisingly similar to that of Indonesia, in spite of the former’s head start at the time of independence, and notwithstanding the fact that it has a marked edge with its handful of elite institutions and access to an extensive international diaspora of leading academics.11 India’s tertiary GER

is slightly below Indonesia’s, its education dropout rates appear to be higher, and its performance in international university rankings is only a little higher. As in Indonesia, governments have adopted an ambivalent stance towards lib-eralisation of the tertiary sector and the role of the private sector. On the one hand, real per student funding has been declining, forcing the public universities to seek alternative funding sources. But caps remain on tuition fee levels, and there are barriers to entry into the industry. As expected, the private institutions have grown most rapidly in disciplines where start-up costs are low, returns to graduates are high, and the supply response from the public sector is sluggish. The country’s regulatory system is complex. Onerous rules cover the minimum

11 For example, two Indian institutions – the Indian Institute of Technology Delhi and the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay (IITB) – were placed in the top 150–200 in the THES 2008 ranking. This paragraph on India draws on OECD (2011b: ch. 5, ‘Building on progress in education’).

qualiications required of staff, in addition to arrangements governing promo -tions, workloads and curricula. The establishment of a new university requires an act of parliament.

Malaysia has consistently attached a high priority to education, with very rapid growth in enrolments at all levels, generous inancial support and the extensive provision of overseas study opportunities. Education has been central to the objec-tive of redressing the country’s large ethnic imbalances, with ethnic-based afirma -tive action quotas for enrolments (and implicitly for faculty recruitment) in public universities introduced as part of the government’s New Economic Policy follow-ing ethnic hostilities in May 1969. There is considerable debate about the effective -ness of Malaysia’s overall education policies, with concern that the system has become heavily bureaucratic and is performing poorly on equity and pedagogic grounds (Lee and Nagaraj 2012). From the mid-1980s there was a rethink of educa -tion policy, prompted by iscal stringencies and global changes. The 1996 Private Higher Educational Institutions Act was a watershed. Private universities were permitted for the irst time, and their numbers have risen rapidly, contributing most of the country’s very rapid growth in tertiary enrolments (Tham 2011). The private universities are also being encouraged to upgrade, with liberalised visa entry provisions for foreign students and faculty. In 2000–05, the government set a target for foreign student numbers to increase from 20,000 to 25,000, but by 2005 the actual number was already twice the target, and 82% of these foreign students were enrolled in higher education. Thus Malaysia has successfully developed a middle-level niche as a regional hub for higher education, based on its relatively low cost and reasonably competent quality assurance. However, major challenges remain (Lim 2011). No Malaysian university performs well in the various inter-national ranking exercises. Concern persists that the afirmative action programs have weakened the public universities. Malay graduate unemployment is high, and there is pressure on an already bloated civil service to hire these graduates.

Singapore aspires to establish world-class universities and to become the lead-ing international centre for high-quality university education in Southeast Asia and beyond (Lee and Gopinathan 2008). Its university sector is not large, compris-ing just three public universities; the oldest, the National University of Scompris-ingapore, is already highly ranked internationally. Major reforms have been introduced since 2000. Universities now have greater autonomy (with a 2005 reform having transformed them from statutory boards under the Ministry of Education to uni-versity companies); one-line budgets; and aggressive endowment funding initia-tives through 3:1 matching grants from the government. The inceninitia-tives systems have also been reformed, with rewards for high performance, opportunities for staff upgrading, favourable staff–student ratios, and frequent, rigorous audits for quality. Singapore universities have aggressively developed international exchanges and cooperation, with notable successes in niche areas such as prestig-ious international business schools. However, the country has been less successful in attracting full-ledged international campuses.

INDONESIAN HIGHER EDUCATION:

DEVELOPMENTS, POLICIES, PRIORITIES

Planning

The Indonesian government’s educational objectives are set out in its Medium-Term Development Plan (Rencana Pembangunan Jangka Menengah, RPJM) for 2010–14 (GOI 2010) and its Master Plan for the Acceleration and Expansion of Indonesian Economic Development (Master Plan untuk Percepatan dan Perlu-asan Pembangunan Ekonomi Indonesia, MP3EI). Key assessments and priorities include the following.

First, the two documents note the signiicant educational advances made. The government has signed on to the Millennium Development Goal that all children will have completed primary education by 2015. By 2008, mean years of school-ing had reached 7.5, and the illiteracy rate for those aged 15 years and above was just 6%. The GER for higher education has been rising steadily, from 14.6% of the age group 19–24 years in 2004 to 23.1% in 2010, but at this rate it is not certain whether the 2014 target of 30% is attainable. The percentage of the workforce with a diploma or degree rose from 5.3% to 6.2% between 2004 and 2008. The indicators for educational quality, relevance, teacher education, governance and accountability are all rising. The MP3EI also emphasises the importance of the knowledge economy as an engine of economic development, and that univer-sity research institutes should be developed as national innovation centres. The number of PhD graduates in science and technology is to be quickly expanded, to about 7,000–10,000 by 2014, although this may be dificult to achieve, as evidently most graduate students prefer the social sciences and humanities.

Second, the RPJM notes several current challenges. Over 1 million children have not completed primary education. There is great pressure for entry into upper secondary schools and universities, relecting the delayed effects of the 1980s decision to aim for a universal nine years of compulsory schooling. In higher education, Indonesia’s GER remains lower than those of its ASEAN neighbours, and access to higher education is uneven by gender, socio-economic status and region.

Third, the government is aiming for greater autonomy in the university sector, commencing with four leading institutions, UI, ITB, UGM and IPB, to be extended to three more, Universitas Pendidikan Indonesia (Indonesian University of Edu-cation, UPI), Universitas Sumatera Utara (University of North Sumatra, USU) and Unair (which is often bracketed with the four above as one of the nation’s ive leading universities). However, the application of the not-for-proit principle in the private provision of education needs to be clariied, especially in light of a recent Constitutional Court ruling, discussed below.

Fourth, the RPJM states that funding and administrative procedures are in need of reform: ‘the current mechanism for the allocation and channelling of education funds is very complex and needs to be simpliied in order to achieve greater efi -ciency and accountability’.

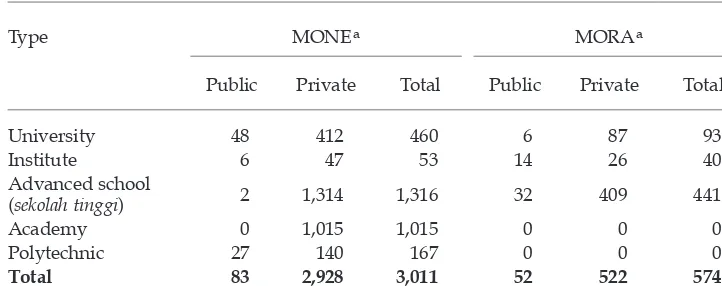

Structure and characteristics of Indonesia’s higher education sector12

In 2010, approximately 5 million students were enrolled in Indonesia’s higher education institutions, up from the estimated 2,000 at the time of independ-ence in 1945. Effectively there is a four-tier system, with three of the tiers located mainly in the public sector.13 But the system is private sector dominated (table 1). Three-quarters of the total expenditure is in the private sector, most of the recent growth has been in these private institutions, and the state universities are de facto increasingly ‘privatised’ in terms of their funding.

The four main groups of higher education institutions are: • 5–7 ‘elite’ public universities;

• 47–49 public universities of mixed but generally low quality;

• a vast private sector of hugely variable quality, comprising approximately 400 private universities and around 3,000 polytechnics, academies and ‘sekolah tinggi’;14 and

12 The most detailed study on the subject is World Bank (2010), which is the source for some of the statistics quoted in this section.

13 The universities and institutes could of course be classiied according to alternative crite -ria. For example, if quality were the main arbiter, the top group would include the elite state universities together with a small group, probably similar in number, of private institutions. 14 Di Gropello, Kruse and Tandon (2011: 190) provide the following explanation of the types of tertiary institutions. ‘Academies are legally deined as higher-education institu -tions that provide instruction in only one ield; most offer diplomas and certiicates for tech -nician-level courses in applied science, engineering, or art at both public and private institu-tions. Advanced schools [sekolah tinggi] provide academic and professional university-level education in one particular discipline. Polytechnic schools are attached to universities and provide subdegree junior technician training. Institutes are those HEIs [higher education institutions] that offer several ields of study by qualiied faculty and are ranked as universi -ties with full degree-granting status. Universi-ties are larger than institutes and offer training and higher education in various disciplines.’ These are unoficial deinitions, and best seen as only a guide; for example, two ‘Institutes’, IPB and ITB, are larger than most universities.

TABLE 1 Indonesian Higher Education Institutions, by Type, 2009/2010

Type MONEa MORAa

Public Private Total Public Private Total

University 48 412 460 6 87 93

Institute 6 47 53 14 26 40

Advanced school

(sekolah tinggi) 2 1,314 1,316 32 409 441

Academy 0 1,015 1,015 0 0 0

Polytechnic 27 140 167 0 0 0

Total 83 2,928 3,011 52 522 574

a MONE = Ministry of National Education; MORA = Ministry of Religious Affairs.

Source: Ministry of Higher Education, Higher Education Statistics, 2009/2010.

• a very large number of universities and other institutions administered by the Ministry of Religious Affairs – mainly Islamic but also including schools for students of Christian and other religious communities – and other government departments (such as health, foreign affairs, defence and inance), also of highly variable quality.

The agency oficially charged with the development of higher education in Indonesia, the Directorate General for Higher Education (Direktorat Jenderal Pen -didikan Tinggi, Dirjen Dikti), has limited capacity to implement the government’s higher education policy. It effectively supervises the 54 state (public) universities, but in practice it has limited inluence over private sector institutions, and even less over the fourth tier of institutions that operate under the purview of other government agencies. These limitations are compounded by its limited inancial resources, equivalent to about 0.3% of GDP. It therefore has very few opportuni -ties to offer inancial incentives to encourage tier three and four institutes to con -form to its policy goals. Moreover, it broadly lacks the analytical capacity to drive the public and intellectual debate on higher education strategies.

Although state institutions constitute just 4% of Indonesia’s higher education institutions, they account for 32% of enrolments, and they set the standard for academic quality and performance (Buchori and Malik 2004). They are the only ones to have any international ranking or proile. The well-established national universities rank highest in student application preferences, owing to prestige, higher quality and lower cost. Most Indonesian academics with foreign PhDs are products of the elite state universities, and state and foreign scholarships at the PhD level go disproportionately to these universities, which also have the high-est proportion of graduate students. Within the state system, a small but variable number are regarded as higher-quality universities. Historically it was the ive noted above (UI, ITB, IPB, UGM and Unair). Other classiications add the state universities in Semarang (Universitas Diponegoro, Undip), Bandung (UPI and Universitas Padjadjaran, Unpad), Medan (USU), Surabaya (Universitas Teknologi 10 Nopember) and Malang (Universitas Brawijaya, Unbraw). Several of these universities have concentrations of PhD holders, indicating that they have the potential to be research-active. The four top-ranking universities in Indonesia in the THES University World Ranking tables (that is, UI, ITB, UGM and IPB) have over 2,500 faculty members with PhDs. However, in aggregate only 5% of faculty lecturers in Indonesian higher education institutions (HEIs) have PhD degrees.15

Until the early 2000s, the state universities were run along civil service lines. Resources were provided by the central government, permanent staff were required to be civil servants, and major decisions about resource allocation, fees and stafing were determined at the centre. Only in the past decade have there been gradual moves towards increased autonomy and greater lexibility, focused mainly on the elite group. This was in part a recognition of the reality that the central government does not have the resources to fund these universities fully. Direct grants from Dikti now typically account for between a third and a half of state university revenues, with the leading state universities at the lower end of

15 Those with at least a masters degree constitute 30% of state HEI and 11% of private HEI faculty.

this range owing to their much greater inancial strength. These universities have the capacity to earn more revenue through commercial activities and supplemen-tary student fees.

Private universities are a relatively recent phenomenon in Indonesia, although some of the larger ones were established in the early 1960s, including Taruma -nagara University and Trisakti University, both located in Jakarta. More began to emerge in the 1970s, some evolving out of ‘sekolah tinggi’, others established de novo. Typically they are creatures of either a major business conglomerate or a religious organisation, as in the case of the various campuses of the Muham-madiyah University. They began to grow very rapidly in the 1980s, in response to rising incomes, limited state iscal capacity, growing commercial demand and the economic deregulation that was occurring at this time. Until the 1990s, the gov-ernment paid little attention to them, other than to ensure that they were not incu-bators of anti-government protest movements. Their status was regularised by a 1999 presidential decree on higher education, PP60/1999. A further boost to their development was the recent requirement that teachers and professional civil serv-ants have at least a bachelor degree. Private HEIs receive very little public money, typically less than 5% of their revenue. There is also very little private educational philanthropy, apart from small-scale scholarships and minor endowments.

The private sector displays greater quality variability than the public sec-tor, with several large, relatively well-endowed private universities at one end of the spectrum and small ‘sekolah tinggi’ with very rudimentary facilities at the other. The well-established private universities are closely integrated with and responsive to the labour market, and their graduates have little dificulty securing employment upon graduation. The ethnic Chinese community is disproportion-ately represented in the better private universities, owing to a semi-formal policy of afirmative action in favour of pribumi (indigenous Indonesian) students at the state universities. The quality of the Islamic universities is also highly variable, with a few strong institutions, such as Universitas Islam Negeri Syarif Hidayatul-lah in Jakarta, operating alongside many of low quality.

There is some specialisation between public and private universities. Private universities usually specialise in low-cost courses in high demand, such as infor-mation technology, inance, accountancy and management. State universities are usually expected to offer a full range of course offerings, including courses in less lucrative ields such as agriculture, public health and mathematics. There is also an expectation that the state universities will undertake research.16 Regional state universities have a local development mission. The HEIs that are under the supervision of other government departments are beyond the scope of this study, except to note that they are by nature specialised institutions. Some, such as the Akademi Statistik (the training institution run by the Central Board of Statistics, BPS) are highly regarded.

16 In the words of the World Bank (2010: 19), private institutions are ‘totally devoid of a research program and do not offer courses in ields thought to be essential for development in areas such as agriculture, forestry and public health’.

Finance

Financial arrangements for Indonesian HEIs are complex. Of Dikti’s 2009 budget of Rp 18.5 trillion, about 85% went to tertiary institutions: 69% to 75 non-autono -mous state HEIs, 11% to the seven autono-mous state universities and 6% to pri -vate institutions (World Bank 2010: ix). According to estimates prepared by the World Bank (2010), in 2009 the average annual cost of course delivery per student in HEIs was about $1,500. This igure is comparable with that in middle-income economies, but quite high relative to Indonesia’s per capita GDP. There is sub-stantial variation in per student costs between state and private institutions, with the average for 2009 being Rp 22 million in the former and Rp 12 million in the latter (World Bank 2010: ix). There are evidently no uniform funding formulae for standardised courses, nor do Dikti allocations reward eficient course delivery. Recurrent Dikti allocations are generally incremental and based on those of the previous year. Capital budgets are determined on a ‘needs’ basis and are negoti-ated case by case. It is oficial Dikti policy to further the general goal of greater autonomy, with a system of block grants, performance-based grants and competi-tive grants, combined with portable scholarships. Law 9/2009 on Legal Educa-tion Entities (Badan Hukum Pendidikan, BHP) was designed to facilitate these objectives, and eventually to extend these principles to senior secondary school funding. However, progress in its implementation has been slow, in part because the Constitutional Court has declared the Law invalid, as we discuss below.

In terms of resource eficiency, the average length of tertiary study for a bach -elor’s degree (known as ‘S1’) has been declining, from 6 to 4.5 years in public universities in the past decade. The graduation time in private institutions has always been shorter and it too has declined in recent years, from 5.7 to 4 years. Given the faster graduation times and lower cost structure of private institutions, the World Bank (2010: 26) estimates that the average cost of a private degree is about half that of a comparable degree from a public university.

Regulation

The overall regulatory framework is therefore changing, albeit slowly. Dikti is caught between the earlier approach to higher education, which for the state uni-versities was highly prescriptive, and the transition to a system that conforms more closely to international best practice, with greater autonomy and performance-based funding. Dikti’s accreditation process is institutionally well established, through the National Accreditation Board for Higher Education (Badan Akreditasi Nasional Pendidikan Tinggi, BANPT), but in practice its small, non-specialised staff are unable to do much more than routine checks.17 The Ministry of

Educa-tion and Culture (until October 2011 the Ministry of NaEduca-tional EducaEduca-tion) is also in the process of inalising a presidential decree for an Indonesian Qualiication Framework. However, the foundations of a credible regulatory framework are not yet present. Serious peer review mechanisms have yet to be developed, and there is not yet the bureaucratic capacity to deliver arms-length assessments.

17 In fact, the director general of Dikti, Djoko Santoso, has stated that about one-quarter of the country’s higher education institutions are not actually accredited (Jakarta Post, 11/7/2011).

Although increasing numbers of Indonesian citizens study abroad, the Indo-nesian university system is rather isolated internationally. This relects the coun -try’s latecomer status, its still low per capita income and the relatively poor English-language proiciency of most Indonesian students. But Indonesian gov -ernment policies reinforce this isolation. Visa regulations frustrate the movement of faculty and students. Indonesia attracted 5,366 international students in 2007, predominantly from Malaysia (52.6%) and East Timor (31%), and almost half in medicine. Malaysia, by comparison, had about 48,000 international students in that year. Indonesia is also missing out on the rapidly growing trend for students to take a semester or a year for study abroad. For example, about 223,000 US students were studying abroad in 2006. Most of these go to Europe, but China attracted 11,100 and Thailand 1,600. Indonesia hosted just 29 of these students.18

Moreover, although Indonesian universities are developing various international twinning and other arrangements, its investment laws discourage a more sub-stantial foreign university presence, of the type now rapidly expanding in several ASEAN countries. As Magiera (2011) demonstrates, in spite of the passing of Law 25/2007 on Investment and the issuing of a uniied ‘Investment Negative List’ (of sectors closed to foreign investment or open with restrictions), considerable uncertainty remains, because government departments are bypassing this list and issuing their own decrees. In the case of higher education, the major imple-menting regulations have been Perpres (Presidential Regulation) 111/2007, which allows foreign investment in limited liability companies with a 49% equity limit, and Perpres 36/2010, which permits foreign investment subject to laws on educa -tion. The latter regulation also removed the foreign equity limit on investment in education, and investment is permitted subject to a ‘special licence’ approved by the education minister. The implementation of both of these laws is uncer-tain, owing both to the Constitutional Court decision on legal education entities discussed below and to Dikti’s own policies. In any case, there is no signiicant foreign university presence, apart from a few ‘foundation year’ programs.

Equity

We noted above the very large differences in tertiary education participation between low and high-income groups, and speciically that the well-off are greatly over-represented in enrolments. By implication, the government’s higher education expenditures are unequalising: 80% of public spending goes to the better-off 40% of households, and over 60% goes to the richest 20% (World Bank 2010: 29, 32, based on calculations from the 2006 National Socio-Economic Sur -vey, Susenas). Even for the poor who manage to enter higher education, very few scholarships are available. Less than 2% of higher education enrollees receive scholarships (World Bank 2010: 35), and these are minimal in nature, with sti -pends of just Rp 350,000 per month. Recognising the problem, in 2010 the gov -ernment announced a ‘bidik misi’ (‘targeted poor’) scheme, which stipulated that

18 We thank Shannon Smith for drawing our attention to these data. Since 1995 a larger, though till modest, number of Australian students have undertaken part of their tertiary studies in Indonesia under the auspices of an Australian support organisation known as ACICIS (Australian Consortium for ‘In-Country’ Indonesian Studies, <http://www.acicis. murdoch.edu.au/>).

20% of students in state universities must be from poor households, and must receive a tuition fee waiver and a stipend. However, no speciic funding has been provided to implement the scheme, and it remains unclear whether it will become operational.

The state universities do make some effort to accommodate poor students, with most informally offering some sort of lexible fee structure for demonstrated cases of economic hardship. However, no detailed information on their practices is available, the schemes lack transparency, and there is almost certainly great variability. With the major public universities now having increased autonomy with regard to fees and admissions (for example, UI now directly admits 50% of its student intake), it is well known that inancial contributions and political connections play an important role in securing entry. As the World Bank (2010: 31) observes, and frequent reports in the Indonesian press attest, the universities ‘have large discretion in admission practices’. The director-general of Dikti stated in 2011 that, in order to control the mushrooming direct admission procedures, which are highly lucrative for universities, the government might revert to the former practice of regulating university entry directly through a national entrance examination (Jakarta Post, 1/7/2011). This hardly seems feasible unless the gov-ernment is willing either to increase direct support to the state universities or to allow higher tuition fees. Neither option is likely.

The Constitutional Court decision on Law 9/2009

One inal observation on the regulatory environment for higher education relates to the decision of the Constitutional Court on 31 March 2010 to declare uncon -stitutional Law 9/2009 on legal education entities. As part of its overall reform program, it was the intention of Dikti to provide increased autonomy with respect to hiring, fees and inancial management more generally for seven leading state universities, all Java-based, comprising the so-called ‘top ive’ plus Undip and Unbraw. The basis for the Constitutional Court decision is controversial, and illus-trates the ambivalence of inluential opinion towards market-based higher educa -tion approaches. The Court concluded that, by allowing the provision of higher education on a user-cost basis, Law 9/2009 limited access to education, treating it as a private good, whereas under the Constitution education is a public good guaranteed for everybody. Clearly the decision does not relect the current reality, demonstrated above, that the poor are not well served by the higher education system. The decision has had the effect of impeding the already slow progress towards greater university autonomy. Moreover, as Gunawan (2010) observes, Law 9/2009 also has implications, as yet uncertain, for the future management and viability of private universities.

INSIDE INDONESIAN UNIVERSITIES: GOVERNANCE AND INCENTIVES

At the heart of any eficient service delivery is a system of incentives and employ -ment practices that motivate and reward good staff performance. Unless there are strong, credible, durable incentives in higher education, it is unlikely that its broader objectives can be met. First, high-performing academics must be pro -vided with the resources needed to discharge their responsibilities. These include

libraries and other information technology resources, laboratories for science-based work, and research support staff. Second, support for the maintenance of academic networks is essential. There need to be active seminar programs and opportunities for international conference participation and collaborative research. Third, there needs to be the freedom to pursue sustained academic endeavours; this ranges from the major (for example, long-term, multi-year and multi-person research projects) to the apparently trivial (such as not being bound by ‘regular’ ofice hours and related civil service requirements). Fourth, while the assessment of academic output is inherently challenging, any assessment system must recognise and be compatible with the nature of the academic environment, including, importantly, international practice. Fifth, transparent, arms-length but administratively simple processes of peer review and competition must be a major determinant of the allocation of resources. Sixth, remuneration must be suf-icient to ensure that academic staff can focus diligently on the discharge of their core teaching, research, administrative and public service responsibilities.

How do practices inside Indonesian universities compare with these bench-marks, given that the system is still embryonic and changing rapidly? Compre -hensive answers to these questions would require detailed survey work. In its absence, we offer the following relections based on ield interviews and the very limited literature on the subject.

The academic salary structure in Indonesian state universities is complex, obscure and poorly geared towards incentives. Actual incomes often bear little relationship to oficial salaries, since most academics earn a signiicant propor -tion of their income – often as much as three-quarters – off-campus. This applies particularly to the better-known academics from leading universities, who have ample external consulting and teaching opportunities. We are unaware of any recent comprehensive data on academic salaries,19 but the following example of

remuneration options for the case of a recently completed international PhD at a leading state university is broadly indicative:

• The lecturer would receive a base civil service (pegawai negeri) salary of approximately Rp 2–3 million ($220–330) per month. Other routine tasks such as committee meetings would attract an additional Rp 2–3 million.

• Supplementation of this income within the university (or, very commonly, in a private university), with a heavy teaching load of ive courses for each semester, would attract about Rp 2 million per course, or Rp 9–10 million per month. This would typically entail a 5½-day teaching week for at least nine months of the year.

• A major administrative load would attract Rp 15 million per month (and possibly more), but the heavy teaching load and hence supplementary income mentioned above would no longer be possible.

• Historically, with a seniority-based promotion system, an academic would have some prospect of being promoted to guru besar (full professor) after 20–25 years of minimally satisfactory teaching performance and very limited academic output. Since Indonesian academics typically complete their PhDs

19 Chatani (2012) presents comparative data on school-teacher salaries, concluding that those for Indonesia are low, even after adjusting for per capita income.

comparatively late, generally when aged in their 30s, this rank might be achieved at around age 55. A salary package at the most senior level might then be up to Rp 30 million per month, including gaji pokok (base salary) of about Rp 10 million, teaching of about Rp 10 million (which for senior academics is very often ‘sub-contracted’ to junior faculty), and professional and research supplements such as uang profesi and tunjangan penelitian of Rp 5–10 million. Several features of this illustrative example are worth emphasising. The irst is its complexity, with many components, not all performance related. Second, there is very little opportunity for serious academic research. This would be largely precluded by both the heavy teaching option and the administrative option. Third, there is an incentive to assume an administrative post quickly, because it offers both control over resources and a more secure path to a reasonable income. Fourth, the seniority-based promotion system provides very little incentive to excel in teaching or research.

Academics and policy makers have long been aware of these problems. Thee (1991: 174) stated that the root cause of low academic productivity is ‘the inad -equate and inappropriate structure of incentives, particularly material incentives, prevailing in the state universities and research institutes’. In his report on the state of Indonesian universities, Geertz (1971) referred to university academ-ics and their environment as characterised by a ‘spasmodic quality – a kind of chronic distraction – [that] arises from the scattering of energies imposed by an irrational salary structure for academics which forces them into multiple occupa-tions, and by the excess of essential tasks over people qualiied to perform them’. A late rector of IPB maintained that the problems could not be resolved ‘as long as a full professor’s pay is less than half the starting salary of his or her advisee who became the manager of a hamburger joint’ (Nasoetion 1991: 76). Not surprisingly, many academics devote most of their time to non-campus work. Clark and Oey-Gardiner (1991), in their study of staff at three top state universities (UI, ITB and IPB), found that academics typically devote about 30% of their time to oficial uni -versity duties. More recently, in a survey of remuneration practices in Indonesian research institutions, Suryadarma, Pomeroy and Tanuwidjaja (2011) found that about three-quarters of the income of the university researchers in their sample came from supplementary or non-core activities such as research projects, con-sulting and additional teaching (often in another institution).

Low oficial salaries are only part of the problem. Academic promotion is based largely on seniority, and is governed by an extremely complex system developed by Dikti and known as the ‘KUM’ (academic credit) system. The weightings employed in the KUM system bear little relationship to usual academic prac-tice (Oey-Gardiner 1991; McCawley 1974). Moreover, although the KUM sys-tem applies only to state universities, their importance among the country’s top universities means that the system also substantially inluences practices in the private universities. Consistent with the civil service culture of state university administration, recommendations for promotion at the middle and senior aca-demic levels must be approved by Dikti.

A second constraint is that the essential resources that academics at leading universities in OECD countries take for granted are rarely available in Indonesia. Foreign journal subscriptions are scarce, even at the top universities, effectively cutting academics off from the international mainstream. Information technology

facilities are generally inadequate. There are, moreover, very few incentives or opportunities for international intellectual engagement, such as international conference participation. Sabbaticals are not available. A well-established seminar culture is rare in Indonesian universities.

Third, inter-institutional academic mobility – an essential ingredient of a dynamic, high-quality system – is almost non-existent. This is due to regulatory restrictions, compounded by a sort of institutional ‘tribal culture’. Staff are typi-cally recruited at junior levels, often having graduated from the same institution, and remain in the institution for life (Oey-Gardiner 1991: 89). Here the private universities display a good deal more lexibility than their state counterparts.

Fourth, virtually no peer review work is undertaken, either of academic out -put or of competitive grant applications. In fact, very few genuinely competi-tive grant facilities are available for academic research. Dikti manages one such scheme, known as Hibah Bersaing (Competitive Grants), but it is small in scale and restricted largely to the sciences. There is very little recourse to outsiders (from other Indonesian institutions or from overseas) in the evaluation processes.

Finally, surveys of pedagogic practices within universities conclude that they are generally not conducive to effective learning and independent inquiry. There tends to be an emphasis on rote learning rather than independent thought. Lectur-ers are frequently not present at class, and delegate their teaching responsibilities to junior staff. Teaching methods also tend to be theoretical rather than practical, and to be lecture based. Hence there is something of a disconnect between aca-demic programs and the needs of the labour market (see, for example, USAID 2009; Di Gropello, Kruse and Tandon 2011: ch. 4).

There are, however, a few hopeful signs of reform, albeit on an extremely modest scale. Reforms have been prompted by a general awareness that Indo-nesian universities are lagging behind on most comparative indicators. With their stronger resource base, some state universities have begun to experiment with various incentive programs to encourage staff to become more research-active. One such program is the dosen inti (core lecturer) facility introduced by UI. Under this scheme, staff receive a relatively high salary, about Rp 15 million per month, on condition that they are research-active. The assessment criteria for research activity typically entail at least one international and one domestic publication per year, and the development each year of at least a formal research proposal. Participants in the scheme are reviewed annually, and modest teaching and outside consulting are permitted. Within the better private universities there is a closer link between performance and reward: staff are expected to teach their designated allotments; student reviews are more likely to be encouraged; there is less multiple jobbing; and salaries are therefore structured on the assumption that staff will be working full time. These universities generally have little or no signiicant research aspirations, or facilities to support research, however, so the promotion system remains heavily based on seniority.

THE FUTURE: ELEMENTS OF A POLICY REFORM AGENDA

The Indonesian university reform agenda is a large and complex one, the vested interests opposed to these reforms are powerful, and there are few obvious ‘reform champions’ embedded in the system. Nevertheless, there are international

pressures to lift standards. These will intensify as the country becomes a major regional and international power, and continues to graduate from the develop-ment assistance that has funded a signiicant proportion of its high-level inter -national graduate education. We therefore conclude with some discussion of elements of a reform agenda.

First, public funding should as much as possible be contestable, and transpar -ently allocated in block grant form against clearly stated objectives and criteria, thus accelerating a process that is now under way in embryonic form. Genuine arms-length and adequately remunerated peer review mechanisms need to be in place. That is, teaching and research that receive public funding need to be reviewed regularly and rigorously. Universities also need to diversify their funding sources, for example, to include high-quality (and generally publishable) contract research.

Second, continuing reform of the state universities is essential, both because of their national importance and because there will be low-on effects to private uni -versities. The government should not be in the business of running uni-versities. They need to be granted full operational autonomy over inances, stafing and student selection, and no longer to be run along civil service lines. Instead, the government needs to set clear performance and service provision goals for them, and to allocate funding accordingly. State universities also need to be encour-aged to optimise the value of their real estate and buildings commercially, since some of this appears to be in excess of their reasonable needs. Faculty and student mobility needs to be encouraged. Excellence in teaching and research needs to be clearly identiied and generously rewarded. Staff conditions – such as sala -ries and support facilities, and opportunities for upgrading and development of international connections – need to be improved signiicantly, with commensu -rate expectations about productivity. At the very top tiers, the government needs to recognise that the compensation levels will have to approximate at least the lower end of the international remuneration spectrum, as the authorities in China and Malaysia, for example, are now doing.

Third, the government should function as a facilitator and regulator, setting clear rules and standards; providing an enabling environment; intervening where markets do not work, or will under-supply key ingredients of a successful univer-sity system; benchmarking eficient service provision; and avoiding unnecessarily complex and opaque regulatory arrangements.

Fourth, these interventions might include the development of high-quality, credible quality assurance programs; broader curriculum development, includ-ing in ields where content, methodologies and delivery modalities are changinclud-ing rapidly; major and well-funded opportunities for staff upgrading and profes-sional enrichment (such as sabbaticals, curriculum development, research initia-tives, new teaching modalities, and international conference participation); and long-term analytical thinking about higher education issues. A generous national research grant scheme needs to be introduced that has progressively more demanding internationally refereed competitive standards and highlights areas of national importance.

Fifth, especially for an educational latecomer such as Indonesia, openness and international engagement are essential at all levels – for students, faculty and pro-viders, and also in the broader labour market. Thus it will be necessary to relax, or at least substantially modify, the current regulatory barriers that affect foreign

students and faculty, the recognition of foreign curricula, and the involvement of educational investors.

Sixth, equity issues are crucial, through mechanisms that ensure that family background, ethnicity, gender and geography are not the major determinants of participation in the higher education system. Generous, merit-based, portable national scholarships need to be provided, at all levels, for domestic and over-seas study. In fact, as a general principle, public funding should increasingly be directed through students – that is, there needs to be a shift from supply-side to demand-side inancing. Contingent funding and loan schemes need to be consid -ered, such as the Higher Education Contribution Scheme pioneered in Australia, once the authorities can be conident that the taxation ofice can implement such schemes.20

REFERENCES

Aghion, P., Dewatripont, M., Hoxby, C., Mas-Colell, A. and Sapir, A. (2010) ‘The govern-ance and performgovern-ance of universities: evidence from Europe and the US’, Economic Policy 25 (61): 7–59.

Barro, R.J. and Lee, J-H (2011) ‘A new data set of educational attainment in the world, 1950–2010’, NBER Working Paper No. 15902, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge MA, available at <http://www.barrolee.com/data/dataexp.htm>.

Booth, A. (1989) ‘The state and economic development: the Ethical and New Order periods compared’, in Observing Change in Asia: Essays in Honour of J.A.C. Mackie, eds R.J. May and W.J. O’Malley, Crawford House Press, Bathurst: 111–26.

Buchori, M. and Malik, A. (2004) ‘The evolution of higher education in Indonesia’, in Asian Universities: Historical Perspectives and Contemporary Challenges, eds P.G. Altbach and T. Umakoshi, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore MD: 249–78.

Chapman, B. (2005) ‘Income contingent loans for higher education: conceptual issues and international reforms’, in Handbook on the Economics of Education, Vol. 2, eds E.A. Hanushek and F. Welch, North-Holland, Amsterdam.

Chatani, K. (2012) ‘Human capital and economic development’, in Diagnosing the Indonesian Economy: Towards Inclusive and Green Growth, eds M. Ehsan, H. Hill and J. Zhuang, Anthem Press, New York NY: 275–300.

Clark, D.H. and Oey-Gardiner, M. (1991) ‘How Indonesian lecturers have adjusted to civil service compensation’, Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 27 (3): 129–41.

Di Gropello, E. with Kruse, A. and Tandon, P. (2011) Skills for the Labor Market in Indonesia: Trends in Demand, Gaps, and Supply, World Bank, Washington DC.

Geertz, C. (1971) A report to the Ford Foundation concerning a program for the stimulation of social sciences in Indonesia, Institute of Advanced Studies, Princeton NJ.

GOI (Government of Indonesia) (2010) RPJM [Medium Term Development Plan] 2010–2014, Book II, Chapter 2, ‘Education’, Bappenas, Jakarta.

Gunawan, J. (2010) Otonomi perguruan tinggi [Autonomy in higher education], Paper presented to the National Scientiic Meeting (Pertemuan Ilmiah Nasional) of the Indo -nesian Academy of Sciences (Akademi Ilmu Pengetahuan Indonesia, AIPI) conference, Jakarta.

20 See Chapman (2005), by the originator of the scheme, for a detailed exposition of the principles behind such a loan-contingent facility. The contingency arises from the fact that students begin to repay the loan, as an income tax surcharge, only when their incomes exceed some threshold, such as average weekly earnings.