Daniel James Palmer is director of institutional research for the South Dakota Board of Regents in Pierre, South Dakota. His research focuses on education policy and analytic techniques.

E-mail: [email protected]

Public Administration Review, Vol. 73, Iss. 3, pp. 441–451. © 2013 by The American Society for Public Administration. DOI: 10.1111/puar.12037.

College Administrators as Public Servants

Th is article deploys Q methodology in an exploration of the public service orientation in the context of American postsecondary leadership. Th irty-seven senior college administrators were asked to rank a series of state-ments regarding the administrative values, motives, and attitudes that underlie their own subjective views on administrative conduct. Analysis proceeded in two stages: (1) factor analysis of the administrative perspectives off ered by participants and (2) qualitative comparison of these perspectives to extant scholarly portrayals of the public service orientation. Results indicate the existence of two dominant perspectives among participants. Factor 1, Societal Trusteeship, is fundamentally oriented toward the needs of external society and expresses a willingness to leverage institutional resources to improve the human condition. Factor 2, Organizational Stewardship, by contrast, is an internally oriented perspective that emphasizes institutional performance. Importantly, the factors are not dichotomous and suggest considerable cognitive complexity in the professional orientations of college executives.

P

ublic administration scholars have long been interested in the profes-sional orientations of public sector managers. One relevant concept from the province of public administration is that of the “public service orientation,” that is, the notion of embrac-ing a duty to serve the publicinterest. Among other things, this viewpoint has been posited to underlie a host of attitudinal, motivational, aff ective, and behavioral diff erences between private and public sector employees. Yet formal eff orts to explore the public service orientation have centered mainly on conventional venues of government and have tended to overlook the realm of the college administrator.1 Th e absence of such work seems

surprising given the gamut of publicly oriented virtues ascribed to higher education and, by association, its managers.

American colleges and universities—especially public institutions—are tied to “government” proper by fi nancial and structural fi bers that shape the norma-tive context of campus administration. In exchange for fi nancial support, state governments put forward a host of expectations for the management of public institu-tions. State governing and coordinating boards have become increasingly involved in managing the internal aff airs of colleges and universities and often press public institutions to demonstrate strong productivity.2

Newman, Couturier, and Scurry recount that legisla-tors and other public offi cials “expect higher education to mirror the changes taking place in the economy … and become more fl exible, adaptable, consumer-friendly, innovative, technologically advanced, per-formance driven, and accountable” (2004, 75). Such attitudes lay much responsibility at the feet of post-secondary administrators. Consequently, Birnbaum and Eckel off er that “[college] presidents may fi nd themselves becoming like middle managers in public agencies rather than campus leaders” (2005, 347).

Given the many linkages between government and higher education, might we not suspect that their respective managers share, to some extent, compara-ble administrative values? It was taken as the central aim of this project to examine the manage-rial perspectives of senior college administrators with respect to the public service orientation. At its core, the research was driven by a single organizing question: What are the administrative orientations of senior college adminis-trators, and how do they compare with existing scholarly portraits of the public service orientation?

As a means for approaching the rather ponderous notion of “administrative orientation,” the study employed Q methodology, an intensive, mixed qualitative-quantitative method designed to map research participants’ subjec-tive perspecsubjec-tives on a given object of thought (Ramlo

Daniel James Palmer South Dakota Board of Regents

Given the many linkages

between government and higher

education, might we not suspect

that their respective managers

share, to some extent,

Observers of the public sector have long contended that with regard to professional values and motives, “government is diff erent.” Early authors, such as Barnard (1938), Appleby (1945), and Mosher (1968), off ered descriptive accounts of a unique normative perspec-tive held by public sector employees. According to these writers, public workers are expected to operate from a deep-rooted sense of duty to the public interest, underpinned by a range of bureaucratic and democratic ideals. Th ese observations gave rise to an entire body of writings on the public service orientation, writings that have cen-tered on several substantive areas. First, publicly oriented professionals are thought to embrace a unique array of personal and administrative values, including accountability, eff ectiveness, empathy, responsive-ness, and self-sacrifi ce (Nalbandian and Edwards 1983; Perry 1996; Posner and Schmidt 1996). Second, a number of social perspectives and needs—such as humanitarianism and the sensed need for job security—similarly have been posited as illustrative of the public serv-ice orientation (Baldwin 1987; Brewer 2003; Houston 2000). Th ird, this perspective has been linked to several behavioral and attitudinal predictors, including high civic participation and comparatively low job satisfaction (Houston 2006; Rainey 1989). Finally, public sector workers consistently have been associated with a preference for intrin-sic rewards over economic incentives (Crewson 1997; Rainey 1982).

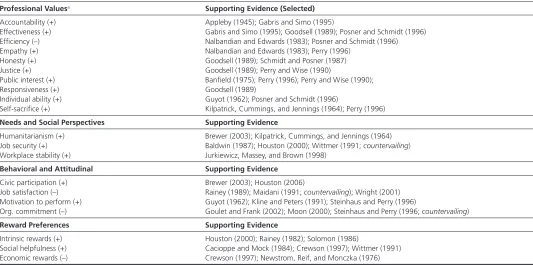

Table 1 organizes the preponderant statements of fi nding from the foregoing literature. Th e framework mostly comprises empirical studies, although it also contains several review articles and thought pieces with high currency in the public administration canon. Th e “Supporting Evidence (Selected)” column notes studies (in paren-theses) whose results may clash with the majority of fi ndings. It follows that this summary may occasionally oversimplify the current state of the research literature, in that some areas (such as job satis-faction) have generated cumulative fi ndings that have been some-what indeterminate. Th is framework is tentative but nonetheless and Newman 2011). Th irty-seven senior campus offi cials in the Upper

Midwest were asked to rank-order a series of 40 statements refl ecting some stance on one of the many values, needs, attitudes, and reward preferences associated (in existing empirical work) with the posited public service orientation. Analysis centered on interpreting the extent to which the emergent (factor-analyzed) managerial perspectives comport with customary impressions of the idealized public service orientation. Two operant factors emerged, both of which can be seen to share characteristics with the public service orientation.

Literature Review: The Public Service Orientation Overview

Beginning with luminary commentaries from Wilson and

Willoughby and extending through the Simon–Waldo furor, public administration scholars have long grappled with the nature of administrative values in public organizations (Molina 2009). In time, public administration practice has come to be associated with a cohesive professional ethic. Some public administration scholars have encapsulated this value set using the notion of the “public service orientation.” Th is concept sometimes is referred to alterna-tively as the “public service ethic,” “public service ethos,” or (more formally) “public service motivation.”

Th eoretical work on the public service orientation has been marked by a diversity of empirical ideas. Early scholars disagreed about the foundations of the public service orientation and intermittently proposed that it encompasses all manner of dynamics, including attitudes, values, motives, needs, drives, and reward preferences. Indeed, many researchers seeking to characterize this worldview have not done so under the explicit banner of “public service orien-tation” research. Th ese conditions can frustrate eff orts to evaluate a cumulative reservoir of fi ndings. Nonetheless, a formal explanatory construct has begun to emerge from this body of related writings.

Table 1 Summary of Public Service Orientation Findings by Topical Area

Professional Valuesa Supporting Evidence (Selected)

Accountability (+) Appleby (1945); Gabris and Simo (1995)

Effectiveness (+) Gabris and Simo (1995); Goodsell (1989); Posner and Schmidt (1996)

Effi ciency (–) Nalbandian and Edwards (1983); Posner and Schmidt (1996)

Empathy (+) Nalbandian and Edwards (1983); Perry (1996)

Honesty (+) Goodsell (1989); Schmidt and Posner (1987)

Justice (+) Goodsell (1989); Perry and Wise (1990)

Public interest (+) Banfi eld (1975); Perry (1996); Perry and Wise (1990);

Responsiveness (+) Goodsell (1989)

Individual ability (+) Guyot (1962); Posner and Schmidt (1996)

Self-sacrifi ce (+) Kilpatrick, Cummings, and Jennings (1964); Perry (1996)

Needs and Social Perspectives Supporting Evidence

Humanitarianism (+) Brewer (2003); Kilpatrick, Cummings, and Jennings (1964)

Job security (+) Baldwin (1987); Houston (2000); Wittmer (1991; countervailing)

Workplace stability (+) Jurkiewicz, Massey, and Brown (1998)

Behavioral and Attitudinal Supporting Evidence

Civic participation (+) Brewer (2003); Houston (2006)

Job satisfaction (–) Rainey (1989); Maidani (1991; countervailing); Wright (2001) Motivation to perform (+) Guyot (1962); Kline and Peters (1991); Steinhaus and Perry (1996)

Org. commitment (–) Goulet and Frank (2002); Moon (2000); Steinhaus and Perry (1996; countervailing)

Reward Preferences Supporting Evidence

Intrinsic rewards (+) Houston (2000); Rainey (1982); Solomon (1986)

Social helpfulness (+) Cacioppe and Mock (1984); Crewson (1997); Wittmer (1991)

Economic rewards (–) Crewson (1997); Newstrom, Reif, and Monczka (1976)

scales—that focus on targeted aspects of a broader concept. It was the aim of the current analysis to off er a fresh approach.

Methodology Q Method: Overview

Q methodology is a research technique designed to focus attention on human subjectivity rather than on empirical eff ects, traits, or characteristics. Procedurally, Q methodology comprises two main operations: the administration of a modifi ed rank-order card sorting task to a selection of participants, followed by a specialized factor-analytic procedure that maps common patterns of subjectivity (Brown 1980).

Instrument Construction

Th e study’s Q-set fl owed conceptually from the above review of literature. Following methodological best practices, the statement sample attempted to provide representative and balanced cover-age of the “universe of discourse” on the public service orientation (Brown 1980; Brown, Durning, and Selden 2008; McKeown and Th omas 1988; Watts and Stenner 2012). Actual statement text was drawn from two sources: (1) academic articles off ering empirical or descriptive accounts of administrative values, attitudes, and motives and (2) interview transcripts generated from a related original study.3 Statements were sought that expressed a subjective point of

view on some aspect of administrative orienta-tion and, more specifi cally, the four general elements identifi ed in the literature review. Th ese included statements about administra-tive values (e.g., “Bureaucratic systems are wasteful and ineffi cient”), needs (e.g., “I often wonder about my job security”), behaviors and attitudes (e.g., “Entrepreneurship is not limited to the business sector”) and reward preferences (e.g., “Much of what I do is for a cause bigger than myself ”).

It was anticipated that categorical divergence might occur between private and public conceptions of normative legitimacy. Consequently, the Q-set contained (1) statements expressing a “public-leaning” view on each of the four substantive dimensions outlined earlier and (2) statements refl ecting a more “private-lean-ing” perspective. However, the fi nal Q-set purposefully contained statements whose sector orientation was more opaque or even unknown. Eff orts were made to select statements that would invite the widest possible variety of viewpoints. In addition to seeking full and nonduplicative coverage of the research topic, succinct statements were favored over verbose ones out of concern for sorting expedience (Watts and Stenner 2012). A total of 40 state-ments were selected for use in this study; a full list is given in the appendix.

Participant Selection

Q studies typically rely on theoretical participant selection tech-niques for the composition of the person sample or “P-set.” McKeown and Th omas (1988) recommend that if respondents’ points of view are expected to vary as a function of a particular attribute, the P-set should be balanced accordingly. Accordingly, this study’s P-set was designed to facilitate representation from public, private, proprietary, nonproprietary, two-year, and four-year provides a plausible skeleton of the public service orientation.

Further, the substance of this outline plays a key role in shaping the content of the Q methodological instrument applied in this analysis.

Related Research on Postsecondary Executives

Postsecondary executives have received meager attention from public administration scholars interested in illuminating the public service orientation. Scant data exists to link college administrators to any particular professional orientation, much less the public service orientation. Dennison, in fact, laments that “much of the extant literature concerning the university [presidency] appears trivial at best and off ensive at worst” (2001, 270).

To what extent does the academic literature suggest that campus executives endeavor to serve the public interest? Th omas asserts that the opportunities for university administrators to engage with the public are many: “Institutional leaders, including trustees, academic aff airs offi cers, deans, and particularly presidents, can play an important role in a community. Th ey serve on local boards, speak at public and private events, host parties or provide a forum for addressing particular issues, and comment for the media about current events” (2000, 76). Kubala and Bailey (2001) contend that community colleges are especially well connected to their external communities, mainly because such institutions often are fi nanced through local tax revenues. Writing about

college presidents specifi cally, Nelson follows that, “With remarkable consistency, presi-dents have nearly universally affi rmed … the responsibility of colleges and their students to uphold the critical social and civic virtues associated with American society” (2000, 109). Yet apart from the rhetorical fl our-ishes that punctuate presidential addresses, little evidence exists that helps us under-stand whether a public orientation is truly ingrained in the professional sensibilities of campus leaders.

Empirical evidence for an external orientation among college executives does exist. Neumann and Bensimon (1990), using an interview design, identify four distinct role orientations among college presidents. One of the four “presidential types” generated by these authors, referred to only as “Presidential Type A,” refl ects a strong external orientation with a clear commitment to the public goods delivered by higher education. According to Neumann and Bensimon, “Presidents refl ecting type A are more than institutional spokespersons or ambassadors to the outside world; they are active participants in and shapers of that outside world. Most assume an active public service role—for themselves as individuals and for their institutions” (1990, 686).

A broad review of the relevant literature suggests that the Q meth-odological approach used in the present article is uncharacteristic of this research area. Only one known study has directly probed the public service orientation using Q methodology (Brewer, Selden, and Facer 2000). Further, studies on the public service orientation typically have not attempted to illuminate the comprehensive per-spectives of their research participants. Most studies have proceeded from quantitative designs—typically based on surveys or other

Yet apart from the rhetorical

fl ourishes that punctuate

presi-dential addresses, little evidence

exists that helps us understand

whether a public orientation is

truly ingrained in the

profes-sional sensibilities of campus

Following advice from Creswell (1998), the study used “member checks” as its main verifi cation technique. Following analysis, a subset of n = 14 participants was provided (by e-mail) with a pre-liminary written summary of each factor and asked to identify the perspective that “sounds most like you.” Participants were encour-aged to elaborate on the reasons for their choice of a self-defi ning perspective. Th is feedback was useful in shaping the fi nal interpreta-tion of the study’s factors.

Analysis and Findings

Factor Analysis and Factor Arrays

In Q methodology, factor analysis centers on the intercorrelation of entire Q sorts rather than individual variables. Th e principal compo-nents analysis with varimax rotation performed on the current data recommended a two-factor solution, that is, two dominant perspec-tives expressed by respondents.4 Yet even after rotation, a number

of mixed-loaded cases (those with signifi cant loadings on multiple factors) remained in the data set. To resolve the problem of mixed loadings, sorts were defi ned (i.e., fl agged as being representative of a factor) manually. Th is approach ensured that no severely mixed cases would shape the developing factor structure. Altogether, fi ve “pure” cases were fl agged for factor 1 and three such cases were fl agged for factor 2. Th e resultant factor arrays (discussed later) produced a fi nal Pearson’s r of .392.

Factor arrays were computed using the PQMethod platform. Factor arrays (see appendix) indicate the relative importance of each state-ment within each factor and are constructed by merging the Q sorts of purely loaded respondents. Factor arrays comprise factor scores, which are simply transformed z-scores (ranging from –4 to +4) gen-erated from the composited raw scores of factor exemplars.

Findings and Interpretation

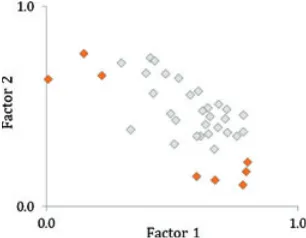

A word about the geometric properties of the factors is in order. As has been noted, the principal components analysis and varimax rotation of the study’s Q sort data resulted in two factor arrays that were correlated at a level of r = .392. Further, the tendency for par-ticipants to load positively on both factors suggested a dual unipolar loading distribution. Figure 1 provides a scatterplot of rotated factor loadings. Th e highlighted observations nearest to either axis denote the cases fl agged as “defi ning” for each factor.

Th e plots shown in this fi gure indicate that the participants’ factor loadings were not orthogonal but rather were obliquely related. Th e absence of statistical independence between factor loadings leads institutions. Participation was limited to a select cluster of

organiza-tional roles: presidents, chief academic offi cers, academic or admin-istrative vice presidents, and academic deans.

Expecting a modest rejection rate, 77 campus administrators in the Midwest were contacted with an off er to participate in the study. Participation was solicited using an invitation letter followed by a direct phone call to each administrator’s offi ce for the purpose of vetting the prospective participant, discussing the research topic, and scheduling a meeting date. Altogether, 37 participants were mustered; participant characteristics are shown in table 2.

Q Sorting

Data collection was conducted on site by the researcher. Participants were instructed to sort printed statements into the shape of a quasi-normal distribution with a –4 to +4 rating scale. Sorts were completed under the following condition of instruction: “Sort these items accord-ing to those with which you most agree (+4) to those with which you most disagree (–4).” By this method, participants were allowed to place a specifi ed number of cards into each column of a histogram-like pat-tern that forced most statements into a middle “neutral” classifi cation, with fewer statements in each tail of the distribution.

At the close of each session, participants were asked to provide verbal responses to a brief sequence of closed- and open-ended con-textual questions. In many cases, these questions led to additional, unstructured conversations about the general research topic. Th ese conversations allowed participants to off er an eclectic range of pro-fessional stories, informal hypotheses, and personal musings. Audio recordings of all sorting sessions were made, and these recordings greatly enriched the study’s analysis phase.

Table 2 Participant Characteristics

n Percent

Total participants — 37 100.0

By institutional type Public, 2-year 5 13.5

Public, 4-year 18 48.6

Private, proprietary, 2-year 1 2.7 Private, proprietary, 4-year 1 2.7 Private, nonproprietary, 2-year 4 10.8 Private, nonproprietary, 4-year 8 21.6

Total 37 100.0

By full-time enrollment Under 5,000 19 51.4

5,000–9,999 7 18.9

10,000–19,999 8 21.6

20,000 or more 3 8.1

Total 37 100.0

By administrative title Presidenta 18 48.6

VP (Academic)b 6 16.2

VP (Administrative)c 6 16.2

Dean 7 18.9

Total 37 100.0

By time in current position Fewer than 5 years 17 45.9

5–10 years 12 32.4

11–15 years 3 8.1

16–20 years 2 5.4

More than 20 years 3 8.1

Total 37 100.0

a. Includes one retired president and two interim presidents. b. Includes participants holding the title “dean of the college.” c. Includes vice presidents of fi nance, administration, and enrollment

management.

Th e concern for public well-being indicated by the foregoing state-ments also seems to extend to these participants’ conceptions of appropriate managerial conduct. Societal trustees are marked by a desire to foster administrative transparency, as well as a rejection of the notion that the need for effi ciency overrides the competing value of equity. Both observations suggest that administrators of this disposition tend to ascribe some level of importance to the notion of stakeholder deference.

Statement 33: I try to act in a manner that is open and visible to relevant stakeholders, both on and off campus. (+4 +1)‡

Statement 16: In my role, effi ciency is more important than equity or fairness. (–3 –2)

Participants’ appraisals of certain facets of the administrative envi-ronment also are revealing. Societal trustees show a favorable view of the policy-making enterprise. Responses are suggestive of a personal affi nity for the consensus-building aspects of the policy process, as well as a distaste for the insinuation that “politics” is a pejorative concept. At the same time, these administrators appear not to relish the opportunity to fraternize with other power elites.

Statement 24: Th e give and take of policy making appeals to me. (+3 –1)†

Statement 8: “Politics” is a dirty word. (–2 –2)

Statement 17: I take pleasure in getting chances to “rub elbows” with important people. (–2 –1)‡

Further, in comparison with organizational stewards (discussed later), societal trustees tend to be more dismissive about the importance of one’s occupational prospects. Th ese participants seem to experience little anxiety with respect to job security and also downplay the need to establish steady footing within the professional ranks.

Statement 18: I often wonder about my job security. (–2 0)†

Statement 13: In terms of my career, it is important to me to create a secure and comfortable future. (–1 +1)‡

Factor 2: Organizational stewardship. Whereas societal trustees are fundamentally oriented toward society at large, organizational stewards are distinguished by the emphasis that they place on their own institutions. Th eirs is an internal perspective, one that focuses diligently on the welfare of their organizations. Th ey are critically concerned with the operational management of their institutions and tout their on-campus labors as a source of pride. Further, their atten-tion to the internal aff airs of their instituatten-tions begets a high degree of personal commitment to their respective organizations. Both of the two highest-ranked statements in the factor array for this group (Statements 34 and 2) were distinguishing between the factors.

Statement 2: I am proud to be working for this organization. (+1 +4)†

Statement 34: What happens to this organization is really important to me. (+3 +4)‡

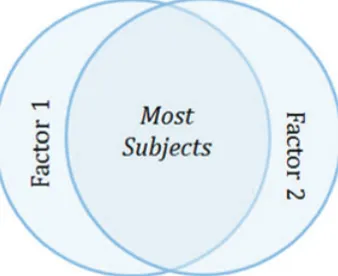

to the conclusion that these two perspectives were not mutually exclusive. Indeed, most participants occupied a middle ground that shared characteristics with two “ideal types.” Despite this overlap (see fi gure 2 for conceptual representation), a small subset of par-ticipants expressed a relatively pure alignment with one pole or the other, and these accounts provided the leverage needed to examine the normative structure of each factor.

Factor 1: Societal trusteeship. Participants loading on this factor convey a humanistic concern for external society and view them-selves as members of an interconnected world. Th ey see themselves as promoters of the public interest and embrace a sense of responsi-bility for facilitating social equity. Th is external orientation perme-ates not only these participants’ common sense of vocational scope but also their shared societal telos. Th ese views are underpinned by factor scores from the following statements:5

Statement 7: I am often reminded by daily events how dependent we are on one another. (+4 0)†

Statement 6: I actively recommend policy positions that represent general public needs and interests. (+2 –3)†

Statement 28: If any group does not share in the prosperity of our society, then we are all worse off . (+2 –2)†

Statement 39: Service to humanity is the best work of life. (+2 –2)†

Societal trustees are fundamentally concerned with the improve-ment of macro-level social conditions, and they appear willing to take an active role in that venture by way of institutional channels. Th ese observations comport with participants’ treatment of state-ments refl ecting altruistic orientations to society. Th ey fi rmly reject the primacy of fi nancial remuneration as a meaningful professional reward and also underscore the salience of service to humanity as a powerful motivator.

Statement 29: Doing well fi nancially is more important to me than doing good deeds. (–4 –1)†

Statement 30: Making a diff erence in society means more to me than personal achievements. (+3 +2)

be positively correlated with one another, and 17 of the study’s 37 participants generated signifi cant loadings on both factors. Th e prevalence of mixed factor loadings points to the possibility that rather than bisecting participants into two separate groups, the Q sample instead activated two diff erent dimensions of a unitary but complex managerial perspective. Th is possibility is further borne out by the observation that even after limiting the extraction of z-score arrays to the purely loading “true believers” of each factor, the fac-tors still show evidence of normative overlap.

Th is certainly is not to say that the factors are indistinct. Several deep fi ssures are indicated by the factor arrays. In general, societal trustees exhibit an externally oriented, humanist perspective. Th is point of view underscores a need for social equity and communi-cates a willingness to apply organizational polices to the benefi t of the broader public. Perhaps consequently, transparency and fairness are underscored as administrative values. Th e policy process is seen as an appealing endeavor, though likely not because of the opportu-nities that it aff ords for socializing with elites. Financial compensa-tion is rebuff ed as a professional motivator, and job security is not a pressing consideration.

Th e second factor is defi ned by a strong sense of organizational stewardship. Th e welfare of the institution is of primary interest, and this concern fosters feelings of organizational involvement and pride. Th e broader needs of society are seen as legitimate concerns but not a realistic object of institutional resources. Th is perspective is somewhat more growth oriented and entrepreneur-ial than its counterpart and fi nds little satisfaction in bureaucratic mechanisms or the policy process. Professional success is of keen signifi cance, and personal assertiveness is a defi ning characteristic.

It appears that qualitative diff erences between the factors are present, but they are by no means purely adversarial and show several points of contact. First, both factors are marked by feelings of professional

accomplishment. Both factors reject the asser-tion that work does not engender a sense of achievement, but at the same time, both are lukewarm to the idea that this satisfaction is derived from social recognition. Second, while the organizational stewardship viewpoint is characterized by its intraorganizational orienta-tion, feelings of attachment to one’s campus weigh prominently for societal trustees as well. Alignment with either factor entails a commit-ment to one’s current institution and a concern for its welfare. Finally, societal trustees are not alone in their contem-plation of social conditions. Indeed, both factors involve some extent of refl ection about community issues, though societal trustees appear more apt to consider an interventional role for their institutions.

Conclusions: A Split Personality?

Th ese mixed loadings and partially overlapping factor scores com-bine to suggest that rather than bilateral adversaries, the two factors are likely to be semi-integrated shades of the same global orienta-tion. But what would account for the coexistence of views that seem somewhat confl icted if not contradictory?

Th is question calls to mind the notion of cognitive complexity, a concept that has been used in various management literatures to Statement 5: I am committed to my campus and its

stake-holders. (+2 +3)

Th is pronounced sense of responsibility to the organization is coupled with a drive for personal control and professional achieve-ment. Compared with societal trustees, organizational stewards report a tendency to exert control when dealing with others and to disapprove of bureaucratic mechanisms. Th ese characteristics seem consistent with stereotypical images of the “take-charge” manager and reinforce these participants’ aspirations for professional success. At the same time, the organizational stewardship view does not appear to be associated with autocratic leanings, as its adherents also affi rm the notion of pluralist decision making.

Statement 23: I tend to tell people what I like and what I don’t like, and what I want them to do. (–1 +3)†

Statement 14: Bureaucratic systems are wasteful and ineffi -cient. (–1 +1)†

Statement 2: I have a very strong desire to be a success in this world. (0 +3)†

Statement 20: My work as an administrator fi ts into a plural-ist decision making system in which many competing actors have a part. (+1 +2)

Organizational stewards, then, tended to place on the positive end of the Q distribution statements related to organizational well-being and a goal-directed personal orientation. On the opposite pole of the sorting continuum, these administrators defi ne themselves in ways seemingly antithetical to the other factor perspective. In particular, organizational stewards express skepticism with the idea that institu-tional priorities should be subjugated in the interest of the public good:

Statement 25: I would prefer seeing cam-pus offi cials do what is best for the larger community, even if it harmed the school’s interests. (0 –4)†

Also in stark contrast to societal trustees, organizational stewards express a lack of aff ec-tion for the policy-making process (Statement 24) and a less visceral reaction to the role of fi nancial motives (Statement 29). Th is

perspective seems slightly more disposed to favor an entrepreneurial, pro-growth administrative agenda, although not through high-risk organizational strategies:

Statement 19: I like to see rewards go to the entrepreneurial units on campus. (0 +2)

Statement 32: One of my key responsibilities is successfully growing the institution’s operations and capacity. (+1 +2)

Statement 31: Campuses must be risk takers. (+2 –1)‡

Summary of factors. A recap is in order. First, it is clear that the factors are not dichotomously populated. Raw Q sorts tended to

Both factors involve some

extent of refl ection about

com-munity issues, though societal

trustees appear more apt to

consider an interventional role

noted that two of the three purely loaded cases on the organizational stewardship perspective were situated in for-profi t institutions, while all fi ve societal trusteeship exemplars worked in public or private nonprofi t institutions. Further, organizational stewards tended, on average, to be substantially younger than their societal trustee counterparts, suggesting a pos-sible diff erence in outlook between early-career and late-career administrators.

Alternatively, situational factors may have triggered the expression of a particular fac-tor. Birnbaum (2002) observes that campus executives are, fi rst and foremost, storytellers.

Postsecondary leaders are captains of institu-tional values and, as such, must shape shared conceptions of reality through compelling narratives. As storytellers, college executives must artfully project a cogent worldview to their listeners. Bolman and Deal add that the essence of selecting and eff ectively applying a particular cognitive frame lies in “match-ing situational cues with a well-learned mental framework” (2008, 11). Perhaps then, it is possible that contextual features (e.g., professional background or institutional factors) or situational fea-tures (e.g., perceptions about the research task) may have activated a particular cognitive script held by the study’s participants. Post hoc verifi cation responses from participants tended to support this interpretation. Feedback from one respondent highlights the fl uid, situational nature of alignment with one perspective over the other:

[Th e two perspectives] are obviously not dichotomous, and I feel that both of them show in my own perspective of my position and the duties and obligations of the deanship. I would say that these are two diff ering themes in an average deanship, with one winning out over the other in particular circumstances. I would bet that you would fi nd that people are very contextually oriented, and that in some instances they were “A” and some more “B like.” (emphasis added)

Th e blending of administrative perspectives seen in the current study would seem to bear important implications for the public service orientation literature. In particular, the foregoing discussion may underscore a chief reason for the inconsistent or inconclusive fi ndings that have marked this area of research. Th e next section examines the conceptual points of contact between the public serv-ice orientation and the study’s factors.

Discussion of the Public Service Orientation

Th e current study was proposed not only as a means to explore the administrative orientations of college executives, but also to fl esh out the public service orientation in a previously untapped venue. Th e study so far has delayed discussion of the latter topic to avoid tainting the study’s interpretation with “logico-categorical” com-mentary.6 What, then, is the fi nal word on the comparison between

the study’s operant factors and the public service orientation?

Th e perspectives painted by this study are reminiscent of those off ered by earlier researchers. Societal trusteeship conjures up notions of describe the ability of individuals to evaluate

complex scenarios and, consequently, to bring multiple perspectives to bear on complex decisions. Bartunek, Gordon, and Weathersby suggest that “complicated understand-ing involves the ability to apply multiple, complimentary perspectives to describing and analyzing events” (1983, 275). To make sense of multiple and confl icting realities, then, organizational leaders often must embrace a palette of cognitive frameworks or interpre-tive lenses (Weick 1995). Similarly, Bolman and Deal (2008) assert that the use of varied “cognitive frames” is a behavioral hallmark of organizational leaders.

Particularly in the present era, the vast admin-istrative complexities encountered by postsec-ondary executives create a need for complex management orientations. New challenges—

such as increasing pressures for productivity, accountability, and aff ordability, uncertain political, economic, and regulatory condi-tions, and movement toward radically redesigned delivery mecha-nisms—present college administrators with environments that seem markedly unsettled. Del Favero notes that “[m]ulti-dimensional, or multi-frame thinking then, as a measure of cognitive complexity, can be considered a requisite tool for university leaders in a time when many believe the challenges presented to the leadership of higher education are greater than ever before” (2006, 285).

Perhaps it should not be surprising, then, that data from the present study seem indicative of multiple perspective taking by college executives. Such an assertion is not new to research on the administrative worldviews of postsecondary leaders. Earlier researchers have found that college presidents tend to simultane-ously embrace an array of managerial perspectives and that situ-ational cues may infl uence the ways in which presidents present themselves to others (Bensimon 1990; Neumann and Bensimon 1990). Cohen and March (1974) and Birnbaum and Eckel (2005) propose that the college presidency is characterized by three main roles—administrator, politician, and entrepreneur—and that each role places diff erent demands on the incumbent. Presidents and other senior college administrators are expected to oscillate—often on a daily basis—among the many “hats” of offi ce. Th ese view-points combine to suggest that the myriad obligations of the higher education executive are undergirded by a discrete set of cognitive schemata. Indeed, Birnbaum and Eckel refer to the “schemas of eff ectiveness” (2005, 359) that college executives construct as a means to reconcile perceived ambiguity in the workplace. Under this view, it seems plausible that the Q instrument simply tapped the societal trusteeship schema among some participants while eliciting the organizational stewardship schema among others.

Understanding individual participants’ leanings toward one or the other of the study’s factors is a matter unto itself. Th e extent to which institutional or other demographic factors may have motivated par-ticular patterns of response is, of course, an empirical question, but one that the small-n data generated by the present study are not well suited to answer. Th ough far from statistically compelling, it can be

It can be noted that two of the

three purely loaded cases on

the organizational stewardship

perspective were situated in

for-profi t institutions, while all fi ve

societal trusteeship exemplars

worked in public or private

nonprofi t institutions. Further,

organizational stewards tended,

on average, to be substantially

younger than their societal

trustee counterparts, suggesting

a possible diff erence in outlook

between early-career and

precise structure of the public service orientation—particularly on college campuses—may require researchers to hit a moving target.

Implications

Perhaps the most important implication of this study for higher educa-tion researchers arises from the fi nding that senior college administra-tors appear to simultaneously identify with multiple role orientations.

Rather than normative monists, these executives tend to be value pluralists whose administrative lenses appear transitory and situational. Th is conclusion not only is consistent with cogni-tive complexity theory but also makes sense in light of college administrators’ multifaceted task environments. Th is pluralism would seem to call into question the eff orts of earlier research-ers to taxonomize campus executives into singu-lar administrative “types.” Such approaches may underestimate college administrators’ tendency to see the world in multidimensional ways. Consequently, the current fi ndings may compel scholars to reframe the ways in which they conceptualize other administrative technologies, such as leadership style and managerial approach.

By extension, this logic implicates the vast majority of studies on the public service orientation and underscores the present study’s main contribution to the public administration literature. Public admin-istration theorists have devoted decades to the task of discerning the public service orientation. Critically, most studies have proceeded from one central, implicit assumption: that the public service orien-tation is a cleanly measurable and stable construct that is, with suffi -cient time and eff ort, empirically defi nable. Th e normative blending seen in the present analysis challenges this view and, consequently, calls for a reexamination of this core assumption.

Strengths, Limitations, and Future Directions Like any work of scholarship, this project admits a number of analytic strengths and weaknesses. In this study, Q methodology allowed for the mapping of complex perspectives by drawing out participants’ whole responses, as opposed to individual traits or characteristics. Th is capability paved the way for naturalistic, com-prehensive, and subject-centered analysis.

At the same time, the current study is limited in its theoretical characterization of “administrative orientation.” Because the study centered only on the aspects administrative orientation that are relevant to the public service orientation literature, the items used in the statement sample were undoubtedly restrictive. For example, participants were not asked to refl ect on their views toward affi rma-tive action, preferred accounting principles, or casual Fridays—as these aspects of administrative orientation do not bear appreciably on the public service orientation. Subsequent Q methodologists studying the broad worldviews of college executives may wish to use a more inclusive and less structured statement sample, one that is not based on an a priori theoretical framework. Th is strategy would allow researchers to see whether similar factors emerge even when they are not being “lured” by the instrument.

Investigating the demographic drivers of administrative orientation (e.g., gender, geography, institutional factors, and even national Brewer, Selden, and Facer’s “samaritans,” who, while not stirred by any

proverbial sense of duty, see themselves as compassionate “guardians of the underprivileged” (2000, 257). Selden, Brewer, and Brudney’s (1999) typology of bureaucratic role orientations, with its “stewards of the public interest” exemplar, also is called to mind. Finally, societal trustees’ human relations orientation seems uncannily similar to that of “Presidential Type A” proposed by Neumann and Bensimon (1990, 686). As described by these authors, such

execu-tives “are generally concerned about making major contributions to the state, to the country, to humanity, or to local regions or communi-ties. Th ey visualize the institution as a partici-pant in an increasingly interdependent world.”

It seems clear that the societal trusteeship

perspective represents the cleanest approxima-tion of the idealized public service orienta-tion. Perry’s (1996) formal model of public service motivation (PSM) includes four main

dimensions: attraction to policy making, commitment to the public interest, compassion, and self-sacrifi ce. It can be argued that all four dimensions are present in the societal trusteeship perspective. However, this perspective also is dissimilar from typical descriptions of public servants in that it appears unconcerned with occupational stability. At the same time, the organizational stewardship perspective appears normatively distant from the public service orientation but still is defi ned by a prevailing sense of duty.

Neither of the factors isolated by the present study represents a “glass slipper” match to the classic public service orientation. While this outcome may speak to the nature of the research instrument or the participant group, another reasonable conclusion exists. It may be that the “classic” public service orientation (to the extent that any such thing exists) is a more conceptually complex construct than is implied by most of the extant research.

Some writers have hinted at this. Th e venerable Anthony Downs (1967) notes an intermingling of self-interest and altruism in the professional motives of bureaucratic offi cials. Nalbandian and Edwards (1983) further suggest that public administrators are marked by a defi ning value set, but that this value set overlaps with those of other professional groups. More recently, Q methodologists Brewer, Selden, and Facer assert that “PSM is more complex than depicted in previous studies that have explored adjunct concepts and contrasted groups … we fi nd that the motives for performing public service are mixed” (2000, 261).

Th ese appraisals cast doubt on the public service orientation as a homogenous and invariable concept. Comparison of the study’s factors to the public service orientation is challenged further by the possibility that the public service orientation itself is not only some-what indistinct but also shifting. Particularly in light of contempo-rary eff orts to “redesign, to reinvent, to reinvigorate” the culture of the public sector, it seems reasonable to think that the normative mold of the public steward has changed, and continues to change.7

Contemporary higher education seems an especially murky petri dish for observing public service values in light of the indefi nite defi nitions of “public” and “private” in academe (Marginson 2007; Newman and Clark 2009). Accordingly, future eff orts to peg the

Perhaps the most important

implication of this study for

higher education researchers

arises from the fi nding that

senior college

administra-tors appear to simultaneously

leadership through such posts as president, chief academic offi cer, vice president, or dean. Such executives traditionally rise from the ranks of the professorate and exercise primary control over major administrative and academic functions. Consequently, the project no doubt refl ects its sociocultural and structural roots in the U.S. postsecondary system.

2. Th e recent ouster and subsequent reinstatement of University of Virginia president Teresa Sullivan by the Board of Visitors off ers a potent example of such board activism.

3. Th e “related original study” mentioned here was an unpublished qualitative examination of public service values conducted as part of a doctoral seminar at a Midwestern research university.

4. All analysis was conducted in PQMethod 2.11, a freeware analytic platform developed by Peter Schmolck of Bundeswehr University Munich.

5. Values in parentheses display the factor scores for factors one and two, respectively. Factor scores ranged from –4 (most disagree) to +4 (most agree). Th ose statements that were “distinguishing” (i.e., generated signifi cant factor

culture) seems a worthwhile venture. Neumann and Bensimon (1990) surmise that context plays a key role in shaping the leader-ship orientations of college executives. Indeed, numerous partici-pants volunteered a casual hypothesis about the demographic drivers of administrative orientation. Yet, while Q methodology is able to bring holistic worldviews into sharper relief, alternative tools are needed to explore their incidence in the working world. On this point, Danielson (2009) shares ideas for integrating Q methodology with traditional survey methods, noting that each of these method-ologies capitalizes on the weaknesses of the other. Such methodo-logical pluralism may aff ord new opportunities for grounding the current fi ndings in the realm of professional practice.

Notes

1. Th e term “college administrator” is used here in an American context. In general, this review applies this term to executives holding positions of academic

Appendix Statement Sample: Z-Scores, Ranks, and Factor Scores

No. Statement

Factor 1 Factor 2

Z-Score Score Z-Score Score

1 I believe in putting duty before self. –0.07 0 0.85 2

2 I am proud to be working for this organization. 0.82 1 1.76 4

3 It is hard for me to get intensely interested in what is going on in my community. –1.35 –3 –1.54 –3

4 A good administrator will expose what he/she views as unethical conduct, even if that activity is not against the law.

0.49 1 0.45 1

5 I am committed to my campus and its stakeholders. 1.04 2 1.50 3

6 I actively recommend policy positions that represent general public needs and interests. 1.03 2 –1.67 –3

7 I am often reminded by daily events how dependent we are on one another. 1.86 4 –0.06 0

8 “Politics” is a dirty word. –1.17 –2 –1.21 –2

9 I have a very strong desire to be a success in this world. –0.17 0 1.07 3

10 Much of what I do is for a cause bigger than myself. 0.55 1 0.37 0

11 The greatest prosperity results from the greatest possible productivity of the people in the organization.

–0.36 –1 0.33 0

12 I rarely think about the welfare of people I don’t know personally. –1.10 –2 –1.31 –3

13 In terms of my career, it is important to me to create a secure and comfortable future. –0.33 –1 0.41 1

14 Bureaucratic systems are wasteful and ineffi cient. –0.89 –1 0.48 1

15 I enjoy the social position in the community that comes with my job. 0.04 0 0.07 0

16 In my role, effi ciency is more important than equity or fairness. –1.48 –3 –0.90 –2

17 I take pleasure in getting chances to “rub elbows” with important people. –0.99 –2 –0.28 –1

18 I often wonder about my job security. –1.18 –2 0.16 0

19 I like to see rewards go to the more entrepreneurial units on campus. 0.41 0 0.66 2

20 My work as an administrator fi ts into a pluralist decision making system in which many competing actors have a part.

1.02 1 0.99 2

21 To me, the phrase “duty, honor, and country” stirs deeply felt emotions. –1.26 –3 0.39 1

22 Serving others would give me a good feeling even if no one paid me for it. 0.66 1 0.38 0

23 I tend to tell people what I like and what I don’t like, and what I want them to do. –0.94 –1 1.22 3

24 The give and take of policy making appeals to me. 1.35 3 –0.22 –1

25 I would prefer seeing campus offi cials do what is best for the larger community, even if it harmed the school’s interests.

–0.16 0 –1.79 –4

26 I would like to be able to work for my organization as long as I wish. –0.21 0 0.27 0

27 The buck stops here. I need to be accountable to stakeholders. 0.17 0 0.45 1

28 If any group does not share in the prosperity of our society, then we are all worse off. 1.09 2 –1.04 –2

29 Doing well fi nancially is more important to me than doing good deeds. –1.72 –4 –0.68 –1

30 Making a difference in society means more to me than personal achievements. 1.25 3 0.92 2

31 Campuses must be risk takers. 1.09 2 –0.34 –1

32 One of my key responsibilities is successfully growing the institution’s operations and capacity.

0.59 1 0.58 2

33 I try to act in a manner that is open and visible to relevant stakeholders, both on and off campus.

1.37 4 0.56 1

34 What happens to this organization is really important to me. 1.23 3 1.95 4

35 I would fi nd it very satisfying to be able to form new friendships with whomever I liked. –0.44 –1 0.22 0 36 I believe everyone has a moral commitment to public affairs no matter how busy they are. –0.10 0 –0.18 –1 37 People may talk about the public interest, but they are really concerned about their self

interest.

–0.55 –1 –0.78 –2

38 My job does not give me a strong feeling of accomplishment. –1.71 –4 –2.44 –4

39 Service to humanity is the best work of life. 1.07 2 –0.99 –2

score diff erences from the other factor) are fl agged († for α = .01, ‡ for α =

.05). While some of the statements shown here are not statistically distin-guishing, they nonetheless refl ect important substantive information about the factors.

6. Brown cautions researchers against the interpretation of Q factors along a priori empirical (i.e., logico-categorical) frameworks out of concern that analysts may “end up describing relationships among their own mental constructs rather than the reality upon which the constructs are superimposed” (1980, 28).

7. Remarks taken from President Bill Clinton’s public address announcing the rollout of the National Performance Review, March 3, 1993 (Shafritz, Hyde, and Parkes 2004, 556).

References

Appleby, Paul H. 1945. Big Democracy. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Baldwin, J. Norman. 1987. Public Versus Private: Not Th at Diff erent, Not Th at Consequential. Public Personnel Management 16(2): 181–93.

Banfi eld, Edward C. 1975. Corruption as a Feature of Governmental Organization.

Journal of Law and Economics 18(3): 587–605.

Barnard, Chester I. 1938. Th e Functions of the Executive. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Bartunek, Jean M., Judith R. Gordon, and Rita Preszler Weathersby. 1983. Developing “Complicated” Understanding in Administrators. Academy of Management Review 8(2): 273–84.

Bensimon, Estela Mara. 1990. Viewing the Presidency: Perceptual Congruence between Presidents and Leaders on Th eir Campuses. Leadership Quarterly 1(2): 71–90.

Birnbaum, Robert. 2002. Th e President as Storyteller: Restoring the Narrative of Higher Education. Th e Presidency 5(3): 32–39.

Birnbaum, Robert, and Peter D. Eckel. 2005. Th e Dilemma of Presidential Leadership. In American Higher Education in the Twenty-First Century: Social, Political, and Economic Challenges, 2nd ed., edited by Philip G. Altbach, Robert O. Berdahl, and Patricia J. Gumport, 340–68. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Bolman, Lee G., and Terrence E. Deal. 2008. Reframing Organizations: Artistry, Choice, and Leadership. 5th ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Boss.

Brewer, Gene A. 2003. Building Social Capital: Civic Attitudes and Behavior of Public Servants. Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 13(1): 5–25.

Brewer, Gene A., Sally Coleman Selden, and Rex L. Facer II. 2000. Individual Conceptions of Public Service Motivation. Public Administration Review 60(3): 254–64.

Brown, Steven R. 1980. Political Subjectivity: Applications of Q Methodology in Political Science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Brown, Steven R., Dan W. Durning, and Sally Coleman Selden. 2008. Q Methodology. In Handbook of Research Methods in Public Administration, 2nd ed., edited by Kaifeng Yang and Gerald J. Miller, 721–63. Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Cacioppe, Ron, and Philip Mock. 1984. A Comparison of the Quality of Work Experience in Government and Private Organizations. Human Relations 37(11): 923–40.

Cohen, Michael D., and James G. March. 1974. Leadership and Ambiguity: Th e American College President. New York: Harper & Row.

Creswell, John W. 1998. Qualitative Inquiry and Research Design: Choosing among Five Traditions. Th ousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Crewson, Philip E. 1997. Public-Service Motivation: Building Empirical Evidence of Incidence and Eff ect. Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 7(4): 499–518.

Danielson, Stentor. 2009. Q Method and Surveys: Th ree Ways to Combine Q and R.

Field Research 21(3): 219–37.

Del Favero, Marietta. 2006. An Examination of the Relationship between Academic Discipline and Cognitive Complexity in Academic Deans’ Administrative Behavior. Research in Higher Education 47(3): 281–315.

Dennison, George M. 2001. Small Men on Campus: Modern University Presidents.

Innovative Higher Education 25(4): 269–84.

Downs, Anthony. 1967. Inside Bureaucracy. Boston: Little, Brown. Gabris, Gerald T., and Gloria Simo. 1995. Public Sector Motivation as an

Independent Variable Aff ecting Career Decisions. Public Personnel Management

24(1): 33–51.

Goodsell, Charles T. 1989. Balancing Competing Values. In Handbook of Public Administration, edited by James L. Perry, 575–84. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass. Goulet, Laurel R., and Margaret L. Frank. 2002. Organizational Commitment across

Th ree Sectors: Public, Non-Profi t, and For-Profi t. Public Personnel Management

31(2): 201–10.

Guyot, James F. 1962. Government Bureaucrats Are Diff erent. Public Administration Review 22(4): 195–202.

Houston, David J. 2000. Public-Service Motivation: A Multivariate Test. Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 10(4): 713–27.

———. 2006. “Walking the Walk” of Public Service Motivation: Public Employees and Charitable Gifts of Time, Blood, and Money. Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 16(1): 67–85.

Jurkiewicz, Carole L., Tom K. Massey, and Roger G. Brown. 1998. Motivation in Public and Private Organizations: A Comparative Study. Public Productivity and Management Review 21(3): 230–50.

Kilpatrick, Franklin P., Milton C. Cummings, Jr., and M. Kent Jennings. 1964. Th e Image of the Federal Service. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Kline, Cathy J., and Lawrence H. Peters. 1991. Behavioral Commitment and Tenure of New Employees: A Replication and Extension. Academy of Management Journal 34(1): 194–204.

Kubala, Tom, and Gina M. Bailey. 2001. A New Perspective on Community College Presidents: Results of a National Study. Community College Journal of Research and Practice 25(10): 793–804.

Maidani, Ebrahim A. 1991. Comparative Study of Herzberg’s Two-Factor Th eory of Job Satisfaction among Public and Private Sectors. Public Personnel Management

20(4): 441–48.

Marginson, Simon. 2007. Th e Public/Private Divide in Higher Education: A Global Revision. Higher Education 53(3): 307–33.

McKeown, Bruce F., and Dan B. Th omas. 1988. Q Methodology. Newbury Park, CA: Sage Publications.

Molina, Anthony D. 2009. Values in Public Administration: Th e Role of Organizational Culture. InternationalJournal of Organizational Th eory and Behavior 12(2): 266–79.

Moon, M. Jae. 2000. Organizational Commitment Revisited in New Public Management: Motivation, Organizational Culture, Sector, and Managerial Level. Public Performance and Management Review 24(2): 177–94. Mosher, Frederick C. 1982. Democracy and the Public Service. 2nd ed. New York:

Oxford University Press.

Nalbandian, John., and J. Terry Edwards. 1983. Th e Values of Public Administration: A Comparison with Lawyers, Social Workers and Business Administrators.

Review of Public Personnel Administration 4(1): 114–29.

Nelson, Steven J. 2000. Leaders in the Crucible: Th e Moral Voice of College Presidents.

Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.

Neumann, Anna, and Estela M. Bensimon. 1990. Constructing the Presidency: College Presidents’ Images of Th eir Leadership Roles, a Comparative Study.

Journal of Higher Education 61(6): 678–701.

Newman, Frank, Lara Couturier, and Jamie Scurry. 2004. Th e Future of Higher Education: Rhetoric, Reality, and the Risks of the Market. San Francisco: Wiley. Newman, Janet, and John Clark. 2009. Publics, Politics and Power: Remaking the

Newstrom, John W., William E. Reif, and Robert M. Monczka. 1976. Motivating the Public Employee: Fact vs. Fiction. Public Personnel Management 5(1): 67–72. Perry, James L. 1996. Measuring Public Service Motivation: An Assessment of

Construct Reliability and Validity. Journal of Public Administration Research and Th eory 61(1): 5–22.

Perry, James L., and Lois Recascino Wise. 1990. Th e Motivational Bases of Public Service. Public Administration Review 50(3): 367–73.

Posner, Barry Z., and Warren H. Schmidt. 1996. Th e Values of Business and Federal Government Executives: More Diff erent than Alike. Public Personnel Management 25(3): 277–89.

Rainey, Hal G. 1982. Reward Preferences among Public and Private Managers: In Search of the Service Ethic. American Review of Public Administration 16(4): 288–302. ———. 1989. Public Management: Recent Research on the Political Context and

Managerial Roles: Structures and Behaviors. Journal of Management 15(2): 229–50. Ramlo, Susan E., and Isadore Newman. 2011. Q Methodology and Its Position in

the Mixed-Methods Continuum. Operant Subjectivity 34(3): 172–91. Schmidt, Warren H., and Barry Z. Posner. 1987. Values and Expectations of City

Managers in California. Public Administration Review 47(5): 404–9.

Selden, Sally Coleman, Gene A. Brewer, and Jeff rey L. Brudney. 1999. Reconciling Competing Values in Public Administration: Understanding the Administrative Role Concept. Administration & Society 31(2): 171–204.

Shafritz, Jay M., Albert C. Hyde, and Sandra J. Parkes, eds. 2004. Classics of Public Administration. 5th ed. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/Th omson.

Solomon, Esther E. 1986. Private and Public Sector Managers: An Empirical Investigation of Job Characteristics and Organizational Climate. Journal of Applied Psychology 71(2): 247–59.

Steinhaus, Carol, and James L. Perry. 1996. Organizational Commitment: Does Sector Matter? Public Productivity and Management Review 19(3): 278–88.

Th omas, Nancy L. 2000. Th e College and University as Citizen. In Civic

Responsibility and Higher Education, edited by Th omas Erhlich, 63–97. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Watts, Simon, and Paul Stenner. 2012. Doing Q Methodological Research: Th eory, Method and Interpretation. London: Sage Publications.

Weick, Karl E. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. Th ousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Wittmer, Dennis 1991. Serving the People or Serving for Pay: Reward Preferences among Government, Hybrid Sector, and Business Managers. Public Productivity and Management Review 14(4): 369–83.