Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 19:26

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Toward Universal Definitions for Direct and

Indirect Assessment

Matt Elbeck & Don Bacon

To cite this article: Matt Elbeck & Don Bacon (2015) Toward Universal Definitions for Direct and Indirect Assessment, Journal of Education for Business, 90:5, 278-283, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1034064

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1034064

Published online: 30 Apr 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 65

View related articles

ISSN: 0883-2323 print / 1940-3356 online DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1034064

Toward Universal Definitions for Direct and Indirect

Assessment

Matt Elbeck

Troy University-Dothan, Dothan, Alabama, USA

Don Bacon

University of Denver, Denver, Colorado, USA

The absence of universally accepted definitions for direct and indirect assessment motivates the purpose of this article: to offer definitions that are literature-based and theoretically driven, meeting K. Lewin’s (1945) dictum that, “There is nothing so practical as a good theory” (p. 129). The authors synthesize the literature to create new definitions of direct and indirect assessment that are evaluated and refined, versus existent literature-based definitions by assessment experts. They conclude by discussing applications of the proposed definitions.

Keywords: accreditation, assessment methods, direct assessment, indirect assessment

College accreditation boards in the United States and abroad require learning goals and ways to assess how well these goals are met (Jones & Price, 2002). The Associ-ation to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business Interna-tional (AACSB) standards (Betters-Reed, Chacko, Marlina, & Novin, 2003) and the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools (SACS) standards (Commission on Colleges, 2006) demand business programs set learning goals addressing the skills, attributes, and knowledge they want their students to obtain, and to demonstrate that their graduates have met these goals. Two broad categories to assess learning are direct and indirect assessment (Martell & Calderon, 2005) such that the AACSB suggests that “indirect measures, however, cannot replace direct assessment of student performance” (AACSB, 2012, p. 68).

Interestingly, the assessment literature has not converged on a single definition of direct or indirect assessment, creating some confusion for faculty to help determine which current and emerging assessment methods fit into which assessment category. The purpose of this article is to provide useful def-initions of direct and indirect assessment. A brief overview of the assessment literature is followed with a two-phase investigation. Phase 1 is a synthesis of the direct and indirect

Correspondence should be addressed to Matt Elbeck, Troy University-Dothan, Department of Marketing, 500 University Avenue, University-Dothan, AL 36304, USA. E-mail: melbeck@troy.edu

assessment literature to create new definitions of direct and indirect assessment. Phase 2 invited assessment experts to evaluate and comment on the new versus existent literature definitions resulting in a revised and more robust final set of definitions.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Assessment guides student learning by encouraging eval-uation of student skills and knowledge (Ramsden, 2003). Learning assessment helps fulfill the learning process itself and contributes to the student’s experience and information about learning goals and strategies (Taras, 2002). Assessment also results in feedback to students (Ovando, 1994) who are able to comprehend the strengths and weaknesses of their work and implement necessary adjustments to improve the quality of their work (Yorke & Longden, 2004). The advan-tages and disadvanadvan-tages of any learning measure is the ability to capture differences in learning subject to the model being used (e.g., Bloom’s taxonomy; Krathwohl, Bloom, & Masia, 1964). The assumption driving this study is if the definitions of direct and indirect assessment are lucid and universal, this should help mitigate a number of design and implementation hurdles such as faculty engagement (Garrison & Rexeisen, 2014) and to meet Assurance of Learning (AoL) standards (Martell, 2007).

DEFINITIONS FOR DIRECT AND INDIRECT ASSESSMENT 279

METHOD

Phase 1: Defining Direct and Indirect Assessment

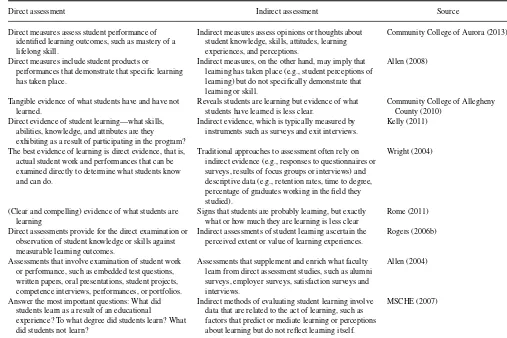

The results of a literature review listing a variety of direct and indirect assessment definitions is shown in Table 1. In toto, the definitions include examples but fall short by not offering a theoretical definition or distinction between di-rect and indidi-rect measures. Definitions based on examples of items in a category are easy to use and apply as long as an object to be categorized is clearly listed in the definition. However, creating an exhaustive, detailed list of possible measures is impractical. Consequently, many possible mea-sures will not be included on list-based definitions, creating difficulty for assessment practitioners wanting to categorize such measures. Further, as new measures are developed, list-based definitions would need constant updating. The goal of this article is to offer definitions that are literature-based and theoretically-driven that meet Lewin’s (1945) dictum that, “There is nothing so practical as a good theory” (p. 129). These new definitions will go beyond lists to explain why a measure should be categorized as direct or indirect. To ac-complish this task, we searched for common threads in the previously published definitions.

As can be seen in Table 1, a common thread among the direct measure definitions is the evaluation of an actual stu-dent performance that could demonstrate achievement of a learning goal (Allen, 2004, 2008; Community College of Aurora, 2013; Wright, 2004). A common thread among the indirect measure definitions is reference to surveys of stu-dents, alumni, or employers (Allen, 2004; Community Col-lege of Allegheny County, 2010; Community ColCol-lege of Aurora, 2013, Kelly, 2011; Wright, 2004), the sense that indirect measures capture opinions, feelings, thoughts, and perceptions (Allen, 2004, 2008; Community College of Al-legheny County, 2010; Community College of Aurora, 2013; Rogers, 2006b; Wright, 2004), and that indirect measures are “less clear” than direct measures (Community College of Al-legheny County, 2010; Rome, 2011). Also, some definitions of indirect measures include reference to measuring the fac-tors that predict, mediate, or may be consequences of learning (Middle States Commission on Higher Education [MSCHE], 2007; Wright, 2004).

A review of the common threads in these definitions re-veals ambiguity in how some measures might be categorized. For example, if we ask students to evaluate the team skills of their peers on a team, is that an indirect measure because it looks like a survey of students, or is it a direct measure be-cause it involves evaluating specific performances? Similarly, if we ask internship supervisors to evaluate oral presentations of interns, is that an indirect measure because it looks like a survey of employers, or a direct measure because it involves evaluating performances? Further, does it make a difference if a rubric is used in either of these, or if a simple rating scale

is used? A simple rating scale might provide less reliable evidence, and thus be less clear, an occasionally mentioned quality of indirect measures.

To develop clear definitions of direct and indirect mea-sures, it is important to note that good learning measures should meet specific goals of learning. In broader terms, the measures must be valid, where a measure is valid if “it does what it is intended to do” (Nunally, 1978, p. 86). However, the validity of the measure is a separable issue from whether it is a direct measure or an indirect measure. For exam-ple, most assessment experts would agree that a 100-item multiple-choice test that has been refined with item analy-sis and is carefully aligned with the learning goals of the program is a direct measure of student learning. But what about a one-item multiple-choice test that is poorly aligned? We argue that this latter measure is not reliable or valid, but the lack of same does not make it an indirect measure; it is simply a poorly designed direct measure. By extension, the use of a rubric versus a rating scale is not a defining distinc-tion between direct and indirect measures, but it could have a substantial impact on reliability and validity. Considering the patterns just identified, we initially proposed definitions of direct assessment and indirect assessment.

Direct assessment. Direct assessment involves scor-ing a learner’s task performance in which the performance is believed to be contingent on achieving a learning goal. The direct assessment definition does not stipulate (a) who must do the scoring (e.g., faculty, peers, alumni, whoever), (b) the method of the scoring (e.g., ratings scales, rubrics, objective scoring), or (c) the type of task (e.g., writing, portfolio gen-eration, taking a test). However, all of these scoring options should be considered carefully to at least achieve face va-lidity. A survey of student perceptions of their own learning would not be a direct measure because it does not involve scoring a task. However, if students scored each other’s oral presentations, this could be a considered a direct measure, subject to the validity caveats mentioned previously.

Indirect assessment. Indirect assessment involves measuring variables assumed to covary with learning that do not involve scoring task performance. The indirect assess-ment definition does not stipulate who must do the scoring, the method of the scoring, or the specific variables measured. However, assumed covariates of learning would include all of the examples in Table 1 related to indirect measures, in-cluding as student perceptions of their learning, student sat-isfaction, retention rates, or placement success. It should be noted, however, that while student perceptions of learning and student satisfaction are often assumed to be associated with learning, more recent research has indicated that these variables are uncorrelated with student learning (Sitzmann, Ely, Brown, & Bauer, 2010).

TABLE 1

Definitions of Direct and Indirect Assessment

Direct assessment Indirect assessment Source

Direct measures assess student performance of identified learning outcomes, such as mastery of a lifelong skill.

Indirect measures assess opinions or thoughts about student knowledge, skills, attitudes, learning experiences, and perceptions.

Community College of Aurora (2013)

Direct measures include student products or

performances that demonstrate that specific learning has taken place.

Indirect measures, on the other hand, may imply that learning has taken place (e.g., student perceptions of learning) but do not specifically demonstrate that learning or skill.

Allen (2008)

Tangible evidence of what students have and have not learned.

Reveals students are learning but evidence of what students have learned is less clear.

Community College of Allegheny County (2010)

Direct evidence of student learning—what skills, abilities, knowledge, and attributes are they exhibiting as a result of participating in the program?

Indirect evidence, which is typically measured by instruments such as surveys and exit interviews.

Kelly (2011)

The best evidence of learning is direct evidence, that is, actual student work and performances that can be examined directly to determine what students know and can do.

Traditional approaches to assessment often rely on indirect evidence (e.g., responses to questionnaires or surveys, results of focus groups or interviews) and descriptive data (e.g., retention rates, time to degree, percentage of graduates working in the field they studied).

Wright (2004)

(Clear and compelling) evidence of what students are learning

Signs that students are probably learning, but exactly what or how much they are learning is less clear

Rome (2011)

Direct assessments provide for the direct examination or observation of student knowledge or skills against measurable learning outcomes.

Indirect assessments of student learning ascertain the perceived extent or value of learning experiences.

Rogers (2006b)

Assessments that involve examination of student work or performance, such as embedded test questions, written papers, oral presentations, student projects, competence interviews, performances, or portfolios.

Assessments that supplement and enrich what faculty learn from direct assessment studies, such as alumni surveys, employer surveys, satisfaction surveys and interviews.

Allen (2004)

Answer the most important questions: What did students learn as a result of an educational

experience? To what degree did students learn? What did students not learn?

Indirect methods of evaluating student learning involve data that are related to the act of learning, such as factors that predict or mediate learning or perceptions about learning but do not reflect learning itself.

MSCHE (2007)

To revisit the ambiguous measures mentioned previously (peer evaluation and employer evaluations), following the definitions proposed here, student peer valuations of team skills would be considered direct measures because they in-volve scoring the performance of a task. Similarly, internship supervisor scoring of presentations would also be considered a direct measure. The conclusion reached here regarding stu-dent peer evaluation is consistent with the conclusion pre-sented by Loughry, Ohland, and Woehr (2014), which cited a personal communication from Dr. Jerry Trapnell, who was the AACSB’s chief accreditation officer.

Phase 2: Validating and Enhancing the Proposed Definitions

The definitions proposed are literature based. To validate and further develop these, input was sought directly from assessment experts. A judgment sample, or purposive sam-ple was used here because we were “searching for ideas and insights” and “not interested in a cross section of opinion but rather in sampling those who can offer some perspective on the research question” (Churchill, 1991, p. 541). Other mar-keting research texts refer to this method as an experience

survey (e.g., Zikmund, 1989). Although recommended as an exploratory technique, some researchers have found that for research questions that can be answered with logic more than with aggregated personal opinions, even a small sample of experts can provide actionable results. For example, Bacon and Butler (1998) argued that small (six to 10 respondents) experience surveys can be quite informative in business to business marketing research, where market demand is driven by functional needs, while large, random sample surveys may be necessary in business to consumer market research, where market demand is often driven by idiosyncratic social and emotional needs. Our goal in this research is to evaluate defi-nitions that should lend themselves to logical analysis as long as the evaluator has expertise in the area. Therefore, an expe-rience survey is appropriate for this research. As described in more detail subsequently, the survey was administered as a simple in-email text survey, enabling participants to respond simply by inserting their responses in a reply email.

Expert sample. Ten experts in the field were invited via email to rate the proposed definition along with two other definitions selected from the literature for direct and

DEFINITIONS FOR DIRECT AND INDIRECT ASSESSMENT 281

rect assessment. Seven experts responded; one declined, one returned an incomplete response, and one could not be lo-cated. These experts included two representing the literature (Allen, 2004, 2008; Rogers, 2006a, 2006b); two represent-ing the academic community with a history of scholarship in student assessment, leadership at AACSB assessment confer-ences, and active participation in the AACSB AoL listserve (Douglas Eder and Kathryn Martell); and three from business accreditation organizations (Steven Parscale, director of ac-creditation, Accreditation Council for Business Schools and Programs; a senior member representing the AACSB who wished to remain anonymous; and Sue Cox, vice president, academic network, European Foundation for Management Development).

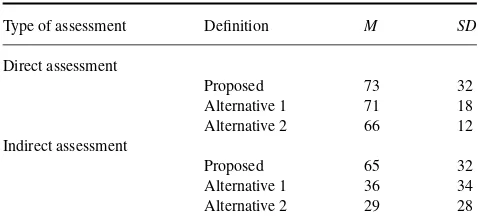

Instrument. Each respondent was asked to rate the quality of two sets of three definitions, one set for direct assessment and one set for indirect assessment. The first seven of nine pairs of definitions in Table 1 were used as the alternate definitions to compare with this study’s proposed definition. We did not use the final two definitions in Table 1 because one was example based, and the other lengthy that may have introduced a contrast effect bias (Sherif, Taub, & Hovland, 1958) when compared to the other much shorter definitions. In addition to randomly presenting this study’s proposed definition in each list to avoid order bias (Ferber, 1952) error, each of the two alternate definitions per as-sessment was assigned a number (e.g., 1, 2, 3) and the two selected was based on a random number table. A 100-point scale was used, where a higher score indicated a better defi-nition. The source of each set of three randomly ordered def-initions was not revealed to the participants. After rating the definitions, the respondents were invited to offer qualitative comments about what they liked and did not like about the various definitions. These comments were requested so that the proposed definitions could be improved after the survey.

RESULTS

Table 2 reports the experts’ rating of the various definitions resulting in the proposed definition (developed in phase one of this study) achieving the highest average scores. Further, our proposed direct and indirect assessment definitions were each rated most highly by five of the seven (71%) experts. The variance in scores was quite large, indicating differences of opinion across our experts, which further underscores the need for this study that can promote clear, well-founded and well-reasoned definitions for direct and indirect assessment. The small sample size and unusual distribution of responses does not justify the use of parametric statistical tests. Con-sidering nonparametric alternatives, if the definitions were equally attractive, each definition would be expected to be rated highest about 33% of the time. Applying the binomial distribution, finding one definition with the highest rating

TABLE 2

Expert Rating of Proposed and Alternative Definitions

Type of assessment Definition M SD

Direct assessment

Proposed 73 32

Alternative 1 71 18

Alternative 2 66 12

Indirect assessment

Proposed 65 32

Alternative 1 36 34

Alternative 2 29 28

five times out of seven or more would have a probability of .045. Therefore, the finding that the proposed definitions were rated most highly is statistically significant at the .05 level.

The generally high expert ratings of the proposed def-initions suggest the defdef-initions would be an improvement over those in the existing literature. To further refine our proposed definitions, we read each expert’s comments and noted the cases where two or more experts raised the same concern. In the following section, we identify these themes and where a change was considered appropriate we incorpo-rate the change into our final set of definitions.

Source of Data

Two experts noted that a key factor discriminating direct from indirect assessment is that direct measures come from observing a student performance, while indirect do not (the source of indirect was not specified). The proposed defini-tion of direct measures already includes reference to rating a student performance, and the definition of indirect measures allowed for other sources besides students. However, since self-reports by students were specifically mentioned by two of our experts as a prototypical indirect measure, we now include specific reference to student surveys as a common source of indirect measures in our definition.

Complex Wording

Three experts indicated the proposed definitions were too complex or awkwardly worded, although most did not offer specific workable improvements. One did mention that the word covary may be confusing to some readers. In response to this suggestion, the definition of indirect measures was modified to use a suitable synonym related.

Reference to Learning Goals

Two experts indicated the importance of connecting direct measures to specific learning goals. Thus, a holistic, non-specific evaluation of a learner’s performance could be con-sidered an indirect measure of learning, but to be direct, the evaluation must be connected to a specific learning goal. Our

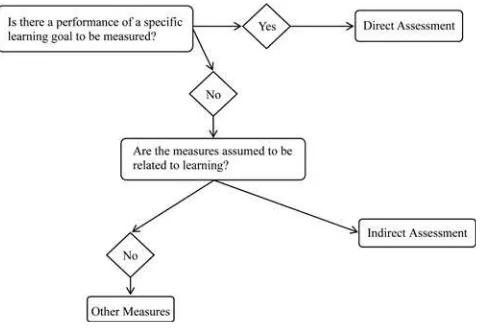

FIGURE 1 Flowchart for direct and indirect assessment.

definition of direct measures was modified to indicate the importance of a specific learning goal.

Perceptions and Opinions

Two experts indicated that indirect measures generally in-clude perceptions, opinions, or feelings about learning, espe-cially from the learners themselves. However, we note that external raters using rubrics (direct measures) will often dis-agree slightly due to differences in perceptions or opinions. Therefore, we do not use objectivity to distinguish between direct and indirect measures.

Final Set of Definitions of Direct and Indirect Assessment

Building on the improvements suggested by the experts, the revised definitions follow.

Direct assessment:Scoring a student’s task performance or demonstration as it relates to the achievement of a spe-cific learning goal.

Indirect assessment:Measures which are assumed to be re-lated to learning that do not involve scoring learner task performance or demonstration.

Figure 1 graphically presents the relationship among di-rect, indidi-rect, and other forms of assessment. The essential discovery is that direct and indirect assessment are not mutu-ally exhaustive. That is, just because a measure is not direct does not make it indirect. Measures must be presumed to be related to learning to be direct or indirect. For a simple example, a student’s height would not be a direct or an indi-rect measure of learning. More substantively, it is possible to question measures of terminally qualified faculty or faculty publications as indirect measures, unless there was strong evidence to believe that these are related to student learning.

DISCUSSION

Clearly, whether the performance itself adequately captures the learning goal is itself an additional challenge that in-cludes both validity and reliability issues. Furthermore, di-rect assessment is necessary but not sufficient for effective assessment; valid direct assessment is also necessary. For as-sessment to be effective, the faculty must be able to close the loop, that is, measure outcomes, make curricular changes, and then measure outcomes again in an effort to detect if the changes have been effective. If the measures are not accurate (i.e., unreliable), or if the sample size is not large enough (i.e., insufficient statistical power), the faculty will not be able to determine with confidence what changes should be made or if past changes have been effective (Bacon, 2004). Examples of how direct and indirect assessment methods may each have high and low validity are shown in Table 3. In our experience, if assessment is not valid, the effort will not have much curricular impact or be sustainable because faculty will not find the assessment findings credible.

The refined definitions stress the importance of learning in the schema of assessment, such as the most powerful decla-ration of learning would be to use direct assessment methods

TABLE 3

Examples of Direct and Indirect Measures by High and Low Validity

Type of assessment High validity Low validity

Direct assessment •A written case analysis •Scored by multiple raters •Using a rubric

•With high inter-rater reliability •Aligned to program goals •With an adequate sample size

•A written case analysis •Scored by a single rater •Using a holistic rating scale •Not aligned with program goals •With a small sample

Indirect assessment •A student survey

•Using multiple measures of engagement •Using behaviorally anchored scales •Completed by an adequate sample

•A student survey

•Using a single measure of engagement •Using an ambiguous rating scale •Completed by a small sample

DEFINITIONS FOR DIRECT AND INDIRECT ASSESSMENT 283

that require the identification of a desired outcome (learn-ing). In contrast, indirect assessment methods are assess-ments about learning that do not include a specified learning outcome and often times are assumed to assess learning. The overarching demand is for faculty to carefully differentiate between the presence or absence of the performance of a spe-cific learning goal that predicates the assessment to be direct or indirect. Even if an assessment measure is not direct in nature, one must not rush to judgment that the assessment is therefore indirect. To qualify as an indirect assessment method, the measure must be assumed to be related to learn-ing, and, if not, it is neither direct nor indirect in nature. We hope this article will motivate progress toward valid direct assessment and improved student learning.

REFERENCES

Allen, M. J. (2004). Assessing academic programs in higher education.

Bolton, MA: Anker.

Allen, M. J. (2008). Strategies for direct and indirect assessment of student learning. Retrieved from http://assessment.aas.duke.edu/ documents/DirectandIndirectAssessmentMethods.pdf

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB). (2012).Eligibility procedures and accreditation standards for business accreditation. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/ ˜/media/AACSB/ Docs/Accreditation/Standards/2003%20Standards/2012-business-accre ditation-standards-update-tracked-changes.ashx

Bacon, D. R. (2004). The contributions of reliability and pretests to ef-fective assessment.Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation,9(3). Retrieved from http://PAREonline.net/getvn.asp?v=9&n=3

Bacon, F. R., & Butler, T. W. (1998).Achieving planned innovation: A proven system for creating successful new products and services. New York, NY: Simon & Schuster.

Betters-Reed, B. L., Chacko, J. M., Marlina, D., & Novin, A. M. (2003, September).Assurance of learning: Small school strategies. Paper pre-sented at the 2003 Continuous Improvement Symposium, University of Memphis, Memphis, TN.

Churchill, G. A. (1991).Marketing research: Methodological foundations (5th ed.). Chicago, IL: The Dryden Press.

Commission on Colleges. (2012). Principles of accreditation: Founda-tion for quality enhancement(5th ed.). Decatur, GA: Southern Asso-ciation of Colleges and Schools. Retrieved from http://www.sacscoc. org/pdf/2012PrinciplesOfAcreditation.pdf

Community College of Allegheny County. (2010). Handbook for faculty. Retrieved from https://www.ccac.edu/uploadedfiles/Imported/ 97a1cd245a3e483fabc996ebea43edd4.pdf

Community College of Aurora. (2013). Direct vs. indirect assessment measures. Retrieved from http://www.ccaurora.edu/students/academic-support/testing/assessment-testing/direct-indirect

Ferber, R. (1952). Order bias in a mail survey.Journal of Marketing,17, 171–178.

Garrison, M. J., & Rexeisen, R. J. (2014). Faculty ownership of the assurance of learning process: Determinants of faculty engagement and continuing challenges.Journal of Education for Business,89, 84–89.

Jones, L. G., & Price, A. L. (2002). Changes in computer science accredita-tion.Communications of the ACM,45, 99–103.

Kelly, R. (2011). Effective assessment includes direct evidence of stu-dent learning. Educational assessment. Retrieved from http://www. facultyfocus.com/articles/educational-assessment/effective-assessment-includes-direct-evidence-of-student-learning/

Krathwohl, D. R., Bloom, B. S., & Masia, B. B. (1964).Taxonomy of educational objectives: Handbook II: Affective domain. New York, NY: David McKay.

Lewin, K. (1945). The Research Centre for Group Dynamics at Mas-sachusetts Institute of Technology.Sociometry,8, 126–136.

Loughry, M. L., Ohland, M. L., & Woehr, D. J. (2014). Assessing teamwork skills for assurance of learning using CATME Team Tools.Journal of Marketing Education,36(1), 5–19.

Martell, K. (2007). Assessing student learning: Are business schools making the grade?Journal of Education for Business,82, 189–195.

Martell, K., & Calderon, T. (2005).Assessment of student learning in busi-ness schools: Best practice each step of the way.Tallahassee, FL: Asso-ciation for Institutional Research.

Middle States Commission on Higher Education (MSCHE). Student learning assessment: Options and resources(2nd ed.). Retrieved from https://www.msche.org/publications/SLA Book 0808080728085320.pdf Ovando, M. N. (1994). Constructive feedback: A key to successful teaching and learning.International Journal of Educational Management,8(6), 19–22.

Ramsden, P. (2003).Learning to teach in higher education.New York, NY: Routledge.

Rogers, G. (2006a). Direct and indirect assessments: What are they good for? Assessment 101, assessment tips with Gloria Rogers.Community Matters, A Monthly Newsletter for the ABET Community, August 2006, 3. Rogers, G. (2006b).Assessment 101: Assessment tips with Gloria Rogers, Ph.D. Direct and indirect assessment. Retrieved from http://www. abet.org/WorkArea/DownloadAsset.aspx?id=1303

Rome, M. (2011).Best practices in student learning and assessment: Creat-ing and implementCreat-ing effective assessment for NYU schools, departments and programs. Retrieved from http://www.nyu.edu/content/dam/nyu/ provost/documents/Assessment/Overview-and-Goals-2011–02–17.pdf Sherif, M., Taub, D., & Hovland, C.I. (1958). Assimilation and contrast

effects of anchoring stimuli on judgments.Journal of Experimental Psy-chology,55, 150–155.

Sitzmann, T., Ely, K., Brown, K., & Bauer, K. (2010). Self-assessment of knowledge: A cognitive learning or affective measure?Academy of Management Learning & Education,9, 169–191.

Taras, M. (2002). Using assessment for learning and learning from assess-ment.Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education,27, 501–510. Wright, B. D. (2004).Guidelines for good assessment of student

learn-ing at the department or program level. Retrieved from https://www. haverford.edu/iec/files/guidelines.pdf

Yorke, M., & Longden, B. (2004).Retention and student success in higher education. Maidenhead, England: Open University Press.

Zikmund, W. G. (1989). Exploring marketing research, third edition. Chicago, IL: Dryden Press.