Robert Biswas-Diener

Editor

Positive Psychology

as Social Change

Editor

Robert Biswas-Diener SE. Aldercrest Rd. 4625 97222 Milwuakie Oregon USA

jayajedi@comcast.net

ISBN 978-90-481-9937-2 e-ISBN 978-90-481-9938-9 DOI 10.1007/978-90-481-9938-9

Springer Dordrecht Heidelberg London New York

© Springer Science+Business Media B.V. 2011

No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, microfilming, recording or otherwise, without written permission from the Publisher, with the exception of any material supplied specifically for the purpose of being entered and executed on a computer system, for exclusive use by the purchaser of the work. Printed on acid-free paper

Editor’s Foreword

If you were to bring all of the authors who contributed to this volume and put them in a single room they would argue. In part it is because some of them are, by nature, argumentative. The other reason is that there is not universal agreement about the science of positive psychology. There is no agreement about the best methods for defining and measuring elusive concepts such as happiness or empathy. There is not even total agreement about how to interpret the results of solid peer-reviewed studies. As Scollon and King point out in the opening chapter, psychologists once interpreted the modest correlations between income and subjective well-being to mean that “money does not matter all that much to happiness.” In more recent times, according to Scollon and King, scientists have looked at those same correlations and offered an interpretation of this relationship as being “always positive and robust.” And so it should come as no surprise that a wide range of academics, hailing from different disciplines and various cultures, might argue about how to best approach the science and application of positive psychology. What is more surprising and— to me at least—more inspiring, is the fact that, despite all the obvious differences, the scholars represented between the pages of this book share in common a desire to engage in a productive dialogue on the topic of the good life. In this way the authors are a reflection of positive psychology itself: Although we have differences and disagreements, we can band together for a higher purpose and work toward the greater good.

For many years this dialogue on the good life focused heavily on personal well-being. This individualistic focus may be the result of the fact that positive psy-chology is deeply anchored in Western culture. The influence of classical Greek philosophy, the humanistic movement, and the predominance of North American scholars in the early days of modern positive psychology may have set the stage for a discipline that was primarily concerned with researching and intervening at the individual level. To some degree I think we can point to the influence of Ed Diener—my father—to explain the emphasis on individual well-being. He was part of the highly influential positive psychology steering committee in the early days of the field and his area of expertise—subjective well-being—was a natural place to look for a useful positive psychology outcome measure. Optimism, courage, and curiosity might all lead to growth and higher functioning but these, in turn, can

vi Editor’s Foreword

be weighed against the gold standard of increases in personal happiness. I suggest no Machiavellian intent on behalf of my father; rather, happiness became a widely used outcome measure precisely because it was useful, sensible, and there were good assessments available. To his credit, my father has turned his attention toward the ways in which well-being intersects public policy and group level flourishing, as illustrated by his chapter in this volume.

Happiness-related measures tend to narrow our attention to the individual level of psychological experience, sometimes at the expense of other legitimate foci for positive psychologists, especially those that are specifically pro-social. Take the case of empathy. Despite the fact that a PsycInfo search reveals that there are more than twice the number of scholarly publications on “empathy” than on “happiness,” papers on the latter topic are 33 times more likely to be paired with “positive psy-chology” as a keyword. In fact, empathy is rarely included in conferences or edited volumes specifically related to positive psychology. By way of illustration, the flag-ship journal of the field—Journal of Positive Psychology—has only two publications on empathy as opposed to 26 on happiness. Similarly, a PsycInfo search on the word “altruism” yields more than 2,300 results of which only five are explicitly coupled with the search term “positive psychology.” Compare this to the term “strengths” which is paired with “positive psychology” in nearly 300 cases.

In all fairness, in their 2000 introductory article on positive psychology, Seligman and Csikzsentmihalyi discussed the emerging field as being concerned with both individual well-being and group-level concepts such as civic virtues and positive institutions. This sentiment was echoed again in Seligman’s 2009 address to atten-dees of the conference of the International Positive Psychology Association. In this speech Seligman issued a challenge to measurably increase flourishing around the world. Although, on some level, this may be interpreted to mean the flourishing of individuals the mechanisms by which this goal is achieved must necessarily include group-level interventions, policies, and social change broadly. It is in this spirit that this volume is being published. I feel that positive psychology is at an important turning point: The idea that positive psychology is not a western pursuit alone, that it is not solely about the individual, and that it is not only about happiness are ideas that are gaining purchase. My editorial mission for this volume was to create a plat-form for scholars to weigh in on various aspects of the idea that positive psychology is about positive social change. As a basic science it is about promoting research and public policy that can be leveraged to enhance social welfare. As an applied science positive psychology is about creating tools and interventions by which we might advance both individual and group-level flourishing. It is my ultimate hope that this volume will become a seminal work for a new generation of positive psychologists who are interested in less individualistic and culturally constrained science.

Editor’s Foreword vii

and the Netherlands, as well as from the United States. Certainly they don’t repre-sent every corner of the globe but I am proud of the fact that American contributors are outnumbered by non-Americans in this book. What’s more, I wanted to avoid the natural professional trap of believing that psychologists own the monopoly on positive psychology. Although we certainly play an overwhelmingly large role in the field, it is a mistake to overlook the many insights offered by people from other professions. As a result, the contributors to this volume include an anthro-pologist, a sociologist, coaches and consultants, educators, entrepreneurs, and a computer scientist in addition to research and practice related psychologists. In this way the authors also reflect positive psychology itself: What once was a principally American concern has become a truly global endeavor.

Despite the fact that my editorial mission was to shift the emphasis of positive psychology from individual to group-level well-being, I tasked the authors with a different set of instructions. I believe that if something is worth doing it is also worth having fun while doing. In this vein I asked the authors to take risks. I offered them a platform by which they might present arguments or theory that they might not otherwise get to voice. Gandhi famously introduced his own idea of “7 deadly sins” which included “science without humanity.” With this in mind I wanted to offer the contributors a chance to bring some of their humanity to the table in a way that is often drained from more traditional academic works. I encouraged them to take linguistic risks, play with conventional style, and sprinkle humor in their chapters. In some cases, such as the chapters by Nic Marks and George Burns, the authors write in the first person. In others, such as the one by Antonella Delle Fave and Giovanni Fava, the authors present a more formal academic tone but their deep passion for their topic shines through. More than anything else, I wanted to avoid creating a collection that included authors’ “staple chapters,” the type of fare they can churn out in mildly modified form to reprint in volume after volume. I wanted fresh ideas and presentation and am pleased to report that, without exception, this is exactly what I received as you will soon discover.

viii Editor’s Foreword

thoughts on public policy, which dovetail nicely with the next part of the book, addressing exactly that topic.

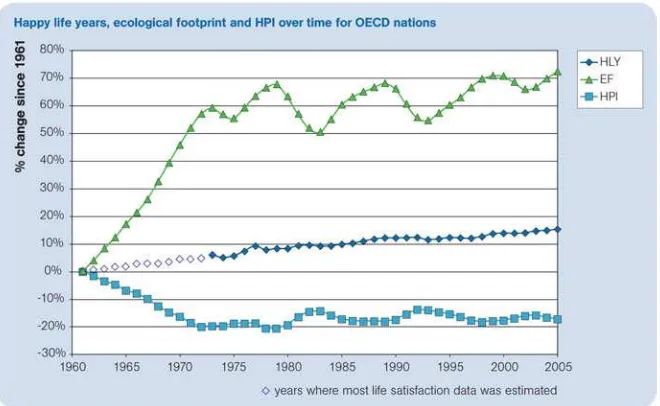

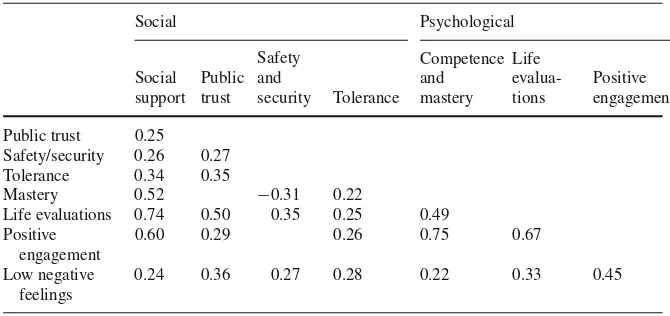

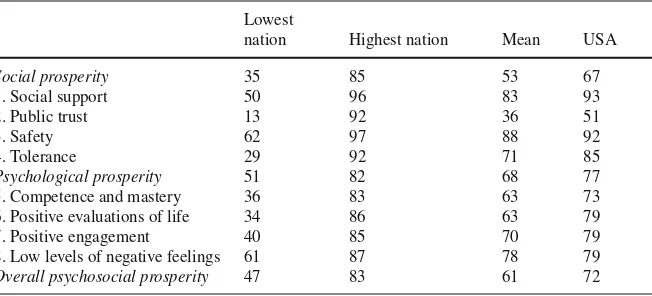

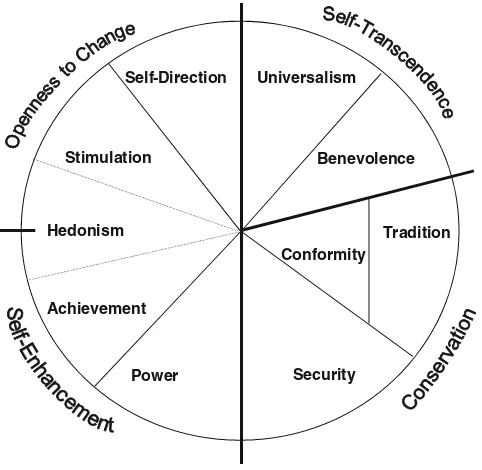

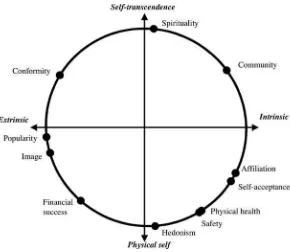

Part II begins with Ed and Carol Diener’s chapter on “monitoring psychoso-cial prosperity.” In it the authors extend the recent professional conversation on creating well-being indicators to a more specific policy suggestion that includes candidate variables. George Burns follows with an interesting account of the Gross National Happiness policy of Bhutan, including some good examples of how that government balances competing factors such as environmental development with the well-being of its citizenry. This leads nicely into the following chapter by Tim Kasser on ecological and materialistic values. Kasser argues that a fundamental shift in values needs to occur that will promote both ecological sustainability and per-sonal well-being. Far from being an environmental alarmist, Kasser offers practical examples of change strategies ranging fromtime affluenceto restrictions on adver-tising. Rounding out the section on policy is a chapter on health promotion by Dora Guðrún Guðmundsdóttir. I am particularly intrigued by Guðmundsdóttir’s chapter

because it is far too seldom that we attend to physical health concerns within positive psychology and far too seldom that health policy looks at positive functioning.

The third part of this book is devoted to the intersection of poverty and positive psychology. This area is one of my personal passions and, indeed, I co-authored the first of two chapters in this part. It is my belief that the study of the emo-tional quality of life of people living in poverty represents the type of approach that Neil Thin would approve, and helps us gain greater knowledge about where and how social change needs to happen from a bottom-up approach. In this chapter, Lindsey Patterson and I explore the psychological dimensions intervention tech-niques related to poverty alleviation programs. In particular, we focus heavily on microfinance and the ways it can increase psychological empowerment. Our chapter is, in essence, a companion to that written by Alex Linley and his colleagues. Linley champions the idea of a strengths-based approach to community development and offers a variety of compelling case studies to illustrate how this might be accom-plished. One of the unusual elements of this chapter is that Linley’s co-authors are personally involved in one of the programs they describe. Rather than raising red flags related to bias and objective science I believe that this is a good example of what Gandhi meant when he advocated “science with humanity.” This portion of the book is intended, in part, to remind readers of our obligation to offer both our science and intervention strategies to less privileged groups.

Editor’s Foreword ix

is one of those instances in which no one can criticize the content for being “aca-demic” or otherwise divorced from real-world application. The same is true of the chapter by Traci Fention, the founder of WorldBlu, which certifies businesses as being “democratic.” After providing a rationale for creating democratic workplaces Fenton offers extraordinarily clear theoretical guidelines for creating democratic organizations and illustrates these with a real world example of Da Vita, a Fortune 500 company. This part of the book should be a go-to source for any coach or consultant aspiring to use positive psychology in his or her practice.

Part V includes two chapters that introduce two topics that I feel have been some-what overlooked by positive psychology: empathy and altruism. Both of these topics are inherently positive and their absence from conferences and volumes on positive psychology is conspicuous. Both of these topics are, by their very definition, “other focused” and are, therefore, a conceptual fit for the mission of this book. The first chapter in this portion is by Lara Aknin and her colleagues and concerns pro-social spending. The authors report on a new but growing research on the psychological effects of spending money on others. Importantly, they describe elements of giv-ing that have rarely been explored in research such as factors that predict recipient happiness, how pro-social spending affects team performance, and how spending on others can create a positive feedback loop. The other chapter in this part is on an aspect of empathy known as perspective taking, and is written by Sara Hodges and her colleagues. Together, these authors tackle a complex research literature that spans empathic concern, accuracy, helping behaviors, and developmental psychol-ogy, to name just a few portions. They do an excellent job of making a case for the natural development of perspective-taking ability and tie this together with con-cern for others. Particularly interesting is their discussion of how perspective taking reduces prejudice, making it among the most powerful psychological mechanisms available for widespread social change.

x Editor’s Foreword

personal agency, responsibility, and a sense of meaning and offer important dis-cussion of cultural caveats. I find their description of their short-term Well-being Therapy (WBT) and its effectiveness to be particularly useful.

The next chapter in the “intervention” part of the book is on recreation, written by my doctoral advisor and friend, Joar Vittersø. To pull back the curtain on the edi-torial process, this was the chapter I had the hardest time placing. Should a chapter on leisure find a place next to a chapter on folk theories of the good life, or might it sensibly be included with chapters on intervention techniques? Ultimately, I felt Vittersø’s discussion of recreation was framed as an intervention. At the heart of this chapter is a provocative and elegant theory of pleasant emotion counter-balanced against unpleasant engagement states. Vittersø argues that we must move between these two psychological states for optimal mental health and discusses the role of leisure pursuits in this context.

The final chapter in the intervention part of the book is on Positive Computing, by Tomas Sander. I believe this is the seminal article on positive computing and brings a fundamental part of daily life—the use of technology—into the wider positive psychology discussion. This, in my opinion, is long overdue. Although Sander envi-sions far-reaching implications of affective and persuasive computing technologies he is not a fantasist. He restrains his commentary to the ways in which computers can potentially help individuals and groups function better. Notably, he brings his expertise as a computer scientist to the table, discussing ethical issues related to privacy and other concerns that might not immediately be on the minds of many positive psychologists. Ultimately, Sander offers a challenge to positive psychology in that he suggests that there may be ways that technology is actually better than human intervention in delivering certain positive psychology services. There will, undoubtedly, be those who are uncomfortable with the idea of a hand-held Personal Happiness Assistant, but Sander makes an excellent case that it iswhen, notif, such devices will appear in our lives.

The book closes—in my opinion—with a bang. Master storyteller and change agent Scott Sherman invokes a rallying cry in his chapter, Change the World! Sherman tells two stories, his own, and that of the most dangerous place in the United States. I will leave it for him to tell the tale, for he does so better than I, but I still feel compelled to mention the effect of his writing. Sherman is not a rosy-eyed cheermonger, of the type that Neil Thin warns us against. Instead, Sherman is inter-ested in proof that one person can make a positive impact, and he delivers nicely on this point.

Editor’s Foreword xi

may be about increasing material wealth for those in need, or in sharing wealth, or in avoiding the trap of valuation wealth to toxic levels. There is no one correct answer about this sticky issue and so I leave it to the intelligence of the reader to tease your own conclusions out of the chapters that follow. The other theme implicit (and sometimes explicit) in this volume is that science—and positive psychological science in particular—possesses many of the answers to pressing social ills. The contributors in this volume, without exception, believe that a better world is pos-sible. But it is not their instinctual optimism displayed in the pages of this book, it is their expert knowledge of cutting-edge science. In some cases it is anecdotal evidence drawn from years of working with clients while in other instances it is a showcase of careful laboratory research. In each chapter the contributors offer at least one tangible, useable tool by which we can affect positive social change. The only thing not on offer here is an excuse not to use them.

Contents

1 What People Really Want in Life and Why It Matters: Contributions from Research on Folk Theories

of the Good Life. . . 1 Christie Napa Scollon and Laura A. King

Part I Some Cautionary Thoughts

2 Think Before You Think . . . 17 Nic Marks

3 Socially Responsible Cheermongery: On the Sociocultural

Contexts and Levels of Social Happiness Policies . . . 33 Neil Thin

Part II Positive Psychology and Public Policy

4 Monitoring Psychosocial Prosperity for Social Change . . . 53 Ed Diener and Carol Diener

5 Gross National Happiness: A Gift from Bhutan to the World . . . 73 George W. Burns

6 Ecological Challenges, Materialistic Values,

and Social Change . . . 89 Tim Kasser

7 Positive Psychology and Public Health . . . 109 Dora Guðrún Guðmundsdóttir

Part III Positive Psychology and Poverty

8 Positive Psychology and Poverty. . . 125 Robert Biswas-Diener and Lindsey Patterson

xiv Contents

9 Strengthening Underprivileged Communities: Strengths-Based Approaches as a Force

for Positive Social Change in Community Development. . . 141 P. Alex Linley, Avirupa Bhaduri, Debasish Sen Sharma,

and Reena Govindji

Part IV Positive Psychology and Organizations

10 Creating Positive Social Change Through Building Positive

Organizations: Four Levels of Intervention . . . 159 Nicky Garcea and P. Alex Linley

11 Organizational Democracy as a Force for Social Change . . . 175 Traci L. Fenton

Part V Positive Psychology and a Focus on Others

12 Better Living Through Perspective Taking . . . 193 Sara D. Hodges, Brian A.M. Clark, and Michael W. Myers

13 Investing in Others: Prosocial Spending for (Pro)Social Change . . 219 Lara B. Aknin, Gillian M. Sandstrom, Elizabeth W. Dunn,

and Michael I. Norton

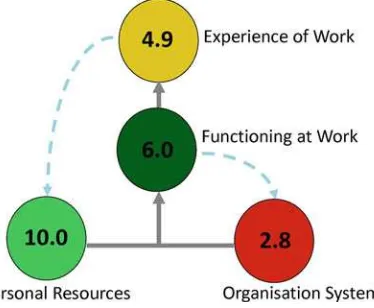

Part VI Positive Psychology and Social Change Interventions 14 How Does Coaching Positively Impact Organizational

and Societal Change?. . . 237 Sunny Stout Rostron

15 Positive Psychotherapy and Social Change . . . 267 Antonella Delle Fave and Giovanni A. Fava

16 Recreate or Create? Leisure as an Arena

for Recovery and Change . . . 293 Joar Vittersø

17 Positive Computing. . . 309 Tomas Sander

Part VII Change the World

18 Changing the World: The Science of Transformative Action . . . . 329 Scott Sherman

Contributors

Lara B. AkninUniversity of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, laknin@psych.ubc.ca

Avirupa BhaduriCentre of Applied Positive Psychology, Coventry, UK Robert Biswas-DienerCentre for Applied Positive Psychology, Coventry, UK; Portland State University, Portland, OR, USA, jayajedi@comcast.net

George W. BurnsHypnotherapy Centre, Milton H. Erickson Institute, Western Australia, Australia, georgeburns@iinet.net.au

Brian A. M. ClarkUniversity of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA, clark13@uoregon.edu

Antonella Delle FaveUniversità degli Studi di Milano, Milan, Italy, Antonella.dellefave@unimi.it

Ed DienerUniversity of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA; The Gallup Organization, Washington, DC, USA, ediener@uiuc.edu

Carol DienerUniversity of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, IL, USA

Elizabeth W. DunnUniversity of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, edunn@psych.ubc.ca

Giovanni A. FavaUniversità degli Studi di Bologna, Bologna, Italy, giovanniandrea.fava@unibo.it

Traci L. FentonWorldBlu, Inc., Cedar Rapids, Iowa, USA, traci@worldblu.com Nicky GarceaCentre of Applied Positive Psychology, Coventry, UK,

Nicky.garcea@cappeu.com

Reena GovindjiCentre of Applied Positive Psychology, Coventry, UK Dora Guðððrún GuðððmundsdóttirPublic Health Institute of Iceland, Reykjavík,

Iceland, dora@publichealth.is

xvi Contributors

Sara D. HodgesUniversity of Oregon, Eugene, OR 97403, USA, sdhodges@uoregon.edu

Tim KasserKnox College, Galesburg, IL, USA, tkasser@know.edu Laura A. KingUniversity of Missouri at Columbia, Columbia, MO, USA, kingla@missouri.edu

P. Alex LinleyCentre of Applied Positive Psychology, Coventry, UK, Alex.linley@cappeu.com

Nic MarksNew Economics Foundation, London, UK, nic.marks@neweconomics.org

Michael I. NortonHarvard Business School, Boston, MA, USA, mnorton@hbs.edu

Lindsey PattersonPortland State University, Portland, OR, USA, lbp@pdx.edu Sunny Stout RostronManthano Institute of Learning (Pty) Ltd, Cape Town, South Africa, express@iafrica.com

Tomas SanderHP Labs, Princeton, NJ 08540, USA, tomas.sander@hp.com Gillian M. SandstromUniversity of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, gsandstrom@psych.ubc.ca

Christie Napa ScollonSingapore Management University, Bras Basah, Singapore, cscollon@smu.edu.sg

Debasish Sen SharmaCentre of Applied Positive Psychology, Coventry, UK Scott ShermanTransformative Action Institute, Los Angeles, CA, USA, ssherman@transformativeaction.org

Chapter 1

What People Really Want in Life

and Why It Matters: Contributions

from Research on Folk Theories

of the Good Life

Christie Napa Scollon and Laura A. King

At the heart of social progress is the human capacity to notice a discrepancy between how things are and how they might be. Certainly, such progress requires more than simply this realization. It requires the belief that change is possible and right. It requires social cooperation and work by groups for the common good. But these activities would never occur without someone at some point noticing that things could be better: that profoundly difficult lives could be good and good lives could be better. Thus, the human capacity to imagine and envision a better or ideal life is linked to the emergence of social progress. Of course, this human capacity to imagine a future that is different from current circumstances can also be a force for social change in the opposite direction. When accompanied by greed, hatred for difference, or concern for power and dominance, we can see this capacity reflected in various historical and social atrocities and catastrophes.

In a sense, naïve notions of what constitutes the good life represent the ideals toward which individuals might aspire or actively strive. These naïve conceptions of optimal human functioning reveal the content of common human longings and can tell us against what standards current circumstances are judged.

Certainly, not-so-naïve conceptions of what makes a life good have had enor-mous impact on human intellectual thought, ethics, and the psychology of well-being. Since Aristotle (and certainly even before), philosophers, religious leaders, and humans more generally have puzzled over what it is that qualifies as a good life. Many thinkers have provided strong statements about how life ought to be lived and what aspects of life qualify it as a good one. Psychology, perhaps especially positive psychology, also provides guidelines in this regard, suggesting, for instance, ways to insure optimal happiness, thriving, or resilience or optimal psychological devel-opment, maturity, moral reasoning, etc. Knowledge of these prescriptions for the good life tells us about the values of psychologists, but may miss the ideals that lurk inside each person – thegood life as defined by everyday people for themselves. The research we review here takes up just this question: What makes a life good for everyday people and what do these conceptions of the good life tell us about the

L.A. King (B)

University of Missouri at Columbia, Columbia, MO, USA e-mail: kingla@missouri.edu

1 R. Biswas-Diener (ed.),Positive Psychology as Social Change,

2 C.N. Scollon and L.A. King

values that everyday people wish to see realized in their own lives? Do everyday people think that money buys happiness? Do they privilege happiness over other values such as, the experience of meaning? Do they believe that career success is more important than relationships? In what ways does the naïve notion of the good life converge with psychological research and in what ways does it diverge? Notions of the good life are certainly contextualized in culture. How does culture influence naïve notion of the good life? Before describing the results of a number of studies on these provocative questions, we briefly discuss the value of studying folk theories of the good life.

Why Study Folk Theories of the Good Life?

The prudential argument. There are at least three reasons to study folk theories of the good life. The first is prudential. As the title of this volume suggests, one of the goals of positive psychology is to improve lives. However, before we can begin to understand how people strive to achieve the good life or the resources that they draw upon in their pursuit of the good life, it is important to understand how people answer the question of “What makes a life good?” As positive psychology articulates its view of the good life, lay persons may well have a different, and possibly opposing, vision of the world (Kasser,2004).

Folk theories and scientific theories complement each other.Fletcher (1995) has argued that scientific theories that take into account folk theories have the potential to produce insights beyond common sense. Moreover, the divergence of folk and scientific theories is more than an aha! opportunity to show that lay thinking is fallible. In fact, the divergence between folk and scientific theories is often where the action is. For example, part of the excitement about the early scientific finding that money and happiness are only weakly correlated was that, at the time, there was widespread belief that this finding ran counter to people’s intuitions. For example, Myers and Diener (1995) included the belief that wealthy people are happier as one of the myths of happiness (see also Myers,2000). Our research was the first to show how folk theories of the good life were actually far closer to scientific theories than researchers realized, although newer research has begun to show money does matter more than we (both scientists and laypersons) think.

On a more practical level, an understanding of the convergence and divergence among folk and scientific theories may further the aims of subjective well-being research by highlighting what everyday people already know or don’t know. Even if a folk theory happens to be factually incorrect, it can serve as a good starting point for helping people to understand the scientific theory. Examining folk theories explicitly allows us to identify how and when psychologists have gotten human beings wrong. That is, folk theories are an excellent place to uncover the subtle misanthropic bias that sometimes creeps into psychological research (itself a central goal of positive psychology, Sheldon & King,2001).

1 What People Really Want in Life and Why It Matters 3

both within and across cultures. After all, folk theories of the good life are prob-ably more strongly shaped by culture than, say, folk theories about electricity and illness (although there are a wide range of beliefs on these topics as well). Rather than treat folk theories as error-ridden sources of information, we view them as a rich source of meaning – an intersection of individual values, local meaning sys-tems, and shared cultural beliefs (Fletcher,1995). As such, folk theories exert an enormous amount of influence on behavior and judgment (Bruner,1990; Fletcher, 1995; Harkness & Super,1996). For example, differences in the beliefs about the malleability of personality influence attributions for behavior, desire for revenge, views toward punishment (Chiu, Dweck, Tong, & Fu,1997; Chui, Hong, & Dweck, 1997).

In terms of SWB research, a culture that defines the good life in terms of wealth has different priorities and therefore behaviors and judgments than a culture that defines the good life in terms of happiness. Thus, understanding how different cul-tures define the good life might lead us to clues as to why some societies are more conducive to happiness than others. Clearly, different societies have different val-ues, so why shouldn’t there be cultural differences in folk theories of the good life? At the same time, there may be some good which is so desirable that people around the world agree on the virtue of that good. Happiness may be one of these.

Our Research Paradigm

In all of our studies of the good life, we asked participants to judge the desirabil-ity and moral goodness of another person’s life based on circumscribed attributes which we manipulated. Specifically, participants viewed a “Career Survey” osten-sibly completed by another individual rating aspects of his or her job. In King and Napa (1998), the target survey was manipulated to reflect a life of high or low hap-piness, high or low wealth, and high or low meaning. All other target information was held constant across experimental conditions. In subsequent studies, we altered the various attributes included in the target survey, but the basic design of the study remained the same. After viewing the survey, participants made judgments about the target’s life.

Independent variables.At this point some consideration of our independent vari-ables is warranted. As noted above, in our research, we have generally manipulated three key variables, happiness, meaning, and money. These characteristics were chosen because they reflected the interests of psychologists and assumptions that psychologists had made about people. Clearly, a great deal of research within posi-tive psychology has focused on happiness and ways to make people happier. From a psychological perspective, it is difficult to argue against the importance of hap-piness. Who doesn’t want to be happy? Yet, the empirical question remained to be addressed: Do everyday people view happiness as an important aspect of the good life?

4 C.N. Scollon and L.A. King

burgeoning debate in the well-being literature, the contrast between hedonic and eudaimonic conceptions of well-being (e.g., Biswas-Diener, Kashdan, & King, 2009; Kashdan, Biswas-Diener, & King,2008; Ryff & Singer,2008). Hedonic well-being is essentially how an individual feels about his or her life; in a very general way this construct maps on to personal happiness. Following Aristotle’s contrast between hedonistic happiness and eudaimonic happiness (for Aristotle, happiness that emerges out of living in accord with one’s daimon), some psychologists had asserted that well-being ought to be understood not simply as hedonic feelings, but as the positive affect that emerges out of living in accord with one’s authentic self (Waterman,2008), actualizing one’s potential (Ryff & Singer,2008) or from the pur-suit of organismic needs (Ryan & Deci,2001). From the eudaimonic perspective, a life devoted to hedonic happiness runs the danger of a pleasant but meaningless existence. Would everyday people prefer a life of hedonic enjoyment, even if it were devoid of meaning?

Finally, we included income as an independent variable in the design. If there was a lesson in research on SWB prior to 1998 it was that money does not buy hap-piness. Research had shown that those who value extrinsic goods such as monetary success over more intrinsic values such as relatedness, autonomy, and competence were more likely to suffer both psychologically and physically (Kasser & Ryan, 1993). Other researchers noted with some surprise the lack of strong relationship between income and happiness. Such results were often described as having impor-tant relevance for everyday people who might think that money buys happiness. Thus, it was of interest to explore the question “Do everyday people think money does buy happiness?” In sum, then, in response to the issues that were relatively hot at the time, we manipulated levels of these three variables in the lives of the targets to be judged. Rather impersonal target lives were then evaluated by participants in terms of their “goodness.” We defined goodness in two ways, the desirability of a life and its moral character. These dependent measures themselves now warrant some discussion.

1 What People Really Want in Life and Why It Matters 5

hell) to 10 (likely to go to heaven), typically hovered around 6.50. In a sense, just as the Protestant work ethic considers earthly success as a mysterious sign of God’s good graces, this rating allowed participants to render their own similarly mysterious evaluation.

Putting the folk into folk theories: The participants.Before sharing the results of these investigations, it makes sense to give a bit of information about the participants who have taken part in these studies. The goal of studying folk concepts of the good life is to uncover the ways that everyday people think of the optimal human life. Thus, one might wonder who the everyday people were who participated in these studies. First, of course, some of the participants were college students. Although the use of students in psychological research is often criticized, it is worth noting that, contrary to popular belief, college students are, in fact, people. Second, we recruited participants from a wide variety of venues – in the waiting rooms of jury duty selec-tions in Dallas County, TX (King & Napa,1998; Twenge & King,2005), in the waiting areas of major US airports (Scollon & King,2004), and around downtown areas, near public transportation stations, and around local neighborhoods (Scollon & Wirtz, 2010). Participation in these studies takes approximately 5 min, which provided participants time to look over the target life and judge it accordingly.

What We Know: A Review of Research on Folk

Theories of the Good Life

What makes a life good?In 1998, we noted that researchers often assumed, without empirical knowledge, that people think money is an important component of the good life. We set out to investigate how people weigh the characteristics of happi-ness, meaningfulhappi-ness, and wealth in determining the overall value of a life. Using our Career Survey paradigm, we found that Americans overwhelmingly defined the good life in terms of happiness and meaning. Not only was happiness considered desirable, but happy people were judged as more likely to go to heaven in our studies. Further, the very best, most desirable, and morally good life was a life of happiness and meaning. Wealth, on the other hand, was relatively unimportant to people’s notions of the good life.

6 C.N. Scollon and L.A. King

More generally, King and Napa (1998) showed some convergence among folk concepts of the good life and the scientific research on subjective well-being. Early SWB research found the correlation between income and happiness to be modest (typically about 0.17–0.21 according to Lucas & Dyrenforth,2006 meta-analysis). In addition, the very rich are somewhat happier than middle-class folks, but not hugely (Diener, Horwitz, & Emmons, 1985). Thus, it seemed that peo-ple, Americans at least, were not prioritizing wealth over happiness and meaning, as some early SWB researchers had feared. Furthermore, everyday folk were not hedonists who eschewed meaning for pleasure. Rather, for the everyday person in our study meaning and happiness were each robust predictors of lives being judged as good.

Since then, the research on wealth and happiness has taken an interesting twist. Whereas early researchers interpreted correlations of 0.20 between income and well-being as small and inconsequential, more recently, the pendulum has swung back somewhat. For example, in1995Myers and Diener included in their “myths about happiness” the belief that money could buy happiness. By 2008 Lucas, Dyrenforth, and Diener’s myths of happiness included “small correlations between income and happiness [mean] that the rich are barely happier than the poor” (p. 2004). Researchers now recognize that the relation between wealth and well-being is, in fact, always positive and robust. Lucas and Schimmack (2009) have argued that the correlational methods for studying wealth and happiness underesti-mate the real effects of wealth. When comparing the difference in happiness among rich and poor groups, the effect size becomes quite large. Even if the absolute size of the effect is not disputed, Lucas and Dyrenforth (2005) noted that effects of similar size for marriage on happiness have been touted as important and large. Ironically, despite a newer take on income and happiness, researchers still rely on old assump-tions about lay theories of the good life. Lucas and Schimmack (2009), for instance, concluded that “No psychologist or economist has proposed a value for the corre-lation between income and happiness that he or she believes would match people’s intuition...it is possible that it is not the layperson’s intuition that is flawed, but

psychologists’ and economists’ interpretation of this effect” (p. 75). In our view, the typical correlations between income and wealth are just about on the mark for people’s intuition. In this case, scientists have gotten people’s intuitions wrong.

1 What People Really Want in Life and Why It Matters 7

mastery (White,1959). In other words, lay persons and scientists alike may con-verge on the components of a life well-lived, but they dicon-verge in their views ofhow to reach the good life. Lay persons, it seems, are willing to work hard and desire effortful engagement, but only if it is easy! Just as the lay notion of a good marriage may equate to a lifelong honeymoon, the lay notion of the good life may equate to a very long vacation.

Although these results seem to indicate that folk notions of the place of effort in the good life are inaccurate, it is worth noting that when hard work was portrayed as occurring in the context of happiness it was viewed as part of the good life. This notion, that positive effect is linked with the role of effort in optimal human states is certainly part and parcel of the psychological notion of states such as flow and intrinsic motivation. These states of high effort are, of course, effort paired with enjoyment.

The good life is a relational life. Although initial research using the Career Survey paradigm typically focused on life in general or the work domain, the good life might be understood as encompassing both work and, of course, social rela-tionships. Freud famously noted that a healthy person should have the capacities for love and work, and many philosophical treatments of the good life include both active engagement in work and meaningful social relationships. Yet, modern people often complain of conflicts between these two realms of experience and often, it seems, work wins out over relationships. Popular culture exhorts us to spend more time with our families and we are reminded that no one wishes on his death bed that he had spent a little more time at work. Are these exhortations needed? Do every-day people view work as more important to evaluations of life than relationships? In a set of related studies, Twenge and King (2005) used a similar methodology to compare the relative importance of relationship versus work fulfillment in the good life. In these studies, targets were described as experiencing high or low fulfillment (defined as meaningful engagement) in either their work or their personal relation-ships. Targets were identified as either male or female. The dependent measures were, again, the desirability and moral goodness of those lives. The results of this work showed that, regardless of target (or participant) sex, fulfillment within the relationship realm was a robust predictor of both desirability and moral goodness. Fulfilling work, although desirable, was not seen as a strong necessity. Indeed, in college and community samples work fulfillment was largely irrelevant to ratings of the moral goodness of a life. In the absence of relationship fulfillment, a target who found enormous fulfillment in the work domain was rated as immoral and destined for hell. These results are especially notable given that the samples were drawn from Dallas, TX (certainly a hotbed of individualism) and Ann Arbor, MI. Even in US samples, meaningful relationships trumped work fulfillment as a determinant of the goodness of a life.

8 C.N. Scollon and L.A. King

suggest that, regardless of how they spend their time, everyday Americans view social relationships as the centerpiece of the good life.

In a way, these results converge with a general sentiment that relationships are the heart of human existence. However, they also suggest that people may underes-timate the role of work in the good life. Specifically, in their study of the most happy individuals, Diener and Seligman (2002) found that every single very happy indi-vidual had strong social relationships. However, not every person with good social relationships was among the most happy. In other words, good social relationships were necessary but not sufficient for high well-being. Although the effect of social relationships on well-being is undeniable, the size of this effect has more recently been disputed and is now believed to be smaller than most people think it is (Lucas et al.,2008; Lucas & Schimmack,2009).

Whereas Diener and Seligman did not examine work fulfillment in their study, Scollon and Diener (2006) examined both changes in work and relationship ful-fillment over time and their correspondence to changes in personality traits. They found that increases in work fulfillment and relationship fulfillment both corre-lated with increases in emotional stability. Furthermore, research has shown that loss of employment can be particularly devastating to well-being (Lucas, Clark, Georgellis, & Diener,2004). This influence of job loss on well-being has been used as an example against the notion of recovery from negative life events. One factor in this negative response may well be the surprise that individuals feel over their own loss, because after all “it was just a job.” The discrepancies among folk theories and SWB findings reveal that lay thinkers may not fully realize the high importance of work fulfillment in the good life.

The good life across cultures.In all of our studies of folk theories of the good life, we have always recognized that notions of the good life are inextricably bound by culture and time. Until recently, however, most of our samples were drawn from middle-class individuals in the United States. Scollon and Wirtz (2010) were the first to examine folk theories of the good life across cultures, comparing two societies similar in economic development, modernity, language, and exposure to Western media – Singapore and the United States. Using stimuli similar to that employed by King and Napa (1998) which examined the components of happiness, meaning, and wealth (with wealth information updated to reflect inflation), Scollon and Wirtz examined the role of culture in folk concepts of the good life.

1 What People Really Want in Life and Why It Matters 9

can be toxic to high life satisfaction (Kasser & Ryan,1993; Nickerson, Schwarz, Diener, & Kahneman,2003).

In addition, the data for this investigation were collected in early 2009, provid-ing an intriguprovid-ing opportunity to see if American views toward wealth had changed after the global financial crisis that began in September 2008. After all, the late 1990s ushered in an era of extraordinary wealth for Americans, and like health which often recedes into the background of people’s lives when it is good, the size of one’s income may be less important in times of prosperity but more impor-tant when it is threatened. With news outlets consimpor-tantly reporting the collapse of banks, foreclosures, and unemployment, financial concerns may have been loom-ing large in American (and Sloom-ingaporean) consciousness, and Scollon and Wirtz (2010) were interested to see if this would be reflected in folk theories of the good life.

Researchers interested in the good life across cultures should note that great care had to be taken to create stimuli of psychological equivalence across both samples. That is, it was not possible to take the incomes of our targets in the Career Survey and simply convert US dollar amounts to the Singaporean dollar. Through exten-sive research of labor statistics and pretesting of materials, Scollon and Wirtz were able to create similar stimuli across our groups (see Scollon & Wirtz for details). Even within the United States, income levels had changed in 10 years, such that the poor target would appear much poorer than intended had the income information remained the same as in 1998.

Scollon and Wirtz found both cultural similarities and differences in folk con-cepts of the good life. Both Singaporeans and Americans defined the good life in terms of happiness and meaning. However, whereas Americans largely discounted wealth when judging the good life, for Singaporeans, the good life included wealth. In samples of both college students and community adults, Singaporean respon-dents considered the wealthy life to be more desirable than the less wealthy one to the degree of half a standard deviation or more. Given that the effects of materialism on life satisfaction are negative and robust (Kasser & Ryan,1993; Nickerson et al., 2003), a society that includes wealth as part of the good life is bound to have lower life satisfaction than one that views the good life only in terms of happiness and meaning.

10 C.N. Scollon and L.A. King

the third-person perspective leads to greater emphasis on objective standards, we might expect people in a third-person perspective to view wealth as more important to the good life than people in the first-person perspective.

To test this idea, Scollon and Wirtz (2010) temporarily manipulated the perspective-taking of Singaporeans either to be from the inside out or to be from the outside in by having people write either brief autobiographies (first person) or biographies (third person) of their lives. Following the perspective-taking manipu-lation, participants viewed the Career Survey, this time with only information about the target’s happiness and wealth level (we dropped meaning as an independent variable to reduce the complexity of the design and because our other studies had shown that both cultures value meaning to nearly the same degree as happiness). As expected, viewing the self from the third person perspective heightens the role of money in conceptions of the good life. After writing about their lives from the third person perspective, respondents viewed the wealthy life as more desirable than the less wealthy one to the degree of 1 standard deviation (SD) in difference. By contrast, when individuals wrote about their lives in the first person, there was less difference in ratings of the poor versus wealthy target (only 1/3 of a SD in difference).

These studies extended past research on the good life in two important ways. First, they showed cultural differences in folk concepts of the good life that are consistent with cross-cultural differences in mean levels of SWB. Second, they demonstrated through a priming experiment how differences in at least one aspect of folk concepts of the good life emerge.

In summary, this program of research demonstrates how examining folk theo-ries of the good life can not only illuminate the ways that everyday people view optimal functioning but also the ways that psychologists have missed the mark in their assumptions about everyday folk. Further, comparing the responses of every-day people to results in the literature demonstrates the realms of fulfillment that may be neglected in folk theories. Finally, they demonstrate how culture influences these naïve theories of optimal human functioning. While these studies are clearly provocative, they certainly do not exhaust the ways that folk theories of the good life may be studied. Next we briefly consider other strategies for exploring this important facet of experience.

Alternative Approaches to Folk Theories of the Good Life

1 What People Really Want in Life and Why It Matters 11

people weigh different characteristics of a life in judging its overall value without interference from other information such as occupation, race, or sex. All other things being equal, would a happy but poor life be considered as good as a rich one? In addition, by rating another person’s life, our approach was indirect and helped min-imize any defensiveness about the good life that answering questions about one’s own life might introduce.

Some past studies have used qualitative approaches to understanding the good life, either through ethnography or open-ended research questions (e.g., “What is happiness?” Lu,2001; Lu & Gilmour,2004). While such approaches undoubtedly provide rich descriptions of local meanings, they provide limited means of assessing broad and truly shared concepts, and they do not facilitate comparisons across indi-viduals or groups. Another approach to understanding how people define the good life is simply to ask participants directly what it is they value (e.g., Schwartz’s value survey). Unfortunately, abstract ratings of values might inflate the value of desirable things. Most characteristics are important, and there is nothing to stop participants from circling the highest rating for everything (Cottrell, Neuberg, & Li,2007; Li, Bailey, Kenrick, & Linsenmeier,2002).

The Next Frontiers of Research on the Good Life

In many ways, research to date has merely scratched the surface of the fascinat-ing realm of folk theories of the good life. Here we suggest a variety of potentially valuable areas for future research, including, expanding the consideration of culture, incorporating manipulations that uncover the sources of individual and national dif-ferences, further examining the role of wealth in lay theories of the good life, and expanding the net of independent variables considered. We address each of these in turn.

12 C.N. Scollon and L.A. King

remains an empirical question. In any case, our paradigm offers an adaptable and simple way to examine the good life across cultures.

More studies examining the construction of lay theories.At the descriptive level, studies of the good life are important in their own right, but future studies should also try to “unpack” folk concepts by examining how they are constructed. Scollon and Wirtz (2010) were the first to show how this can be done by combining context-sensitivity (Suh,2007) with perceptions of the good life. These studies are also interesting in that they demonstrate both stability and malleability of folk theo-ries. On the one hand, the American conception of the good life remained relatively unchanged over a decade. On the other hand, experimental manipulations can affect judgments of the goodness of a life. Future research will hopefully be able to establish the boundaries of stability and transient factors in constructions of the good life.

A deeper understanding of the role of wealth in the good life.Lay theories of the good life in North America are primarily defined in terms of happiness and meaning, not wealth. At the same time, newer research is beginning to show there may be a kernel of truth to the saying that money can buy happiness (Lucas & Schimmack, 2009). One possible explanation for why Americans may downplay the role of wealth in the good life is that the accumulation of wealth often requires hard work, and many people may be unwilling to sacrifice a life of leisure in exchange for more money. Consistent with this notion, Scollon and King (2004, Study 1) found an interaction among wealth and effort such that a wealthy life of hard work was valued just as much as a wealthy life of leisure. Thus, people are sensitive to the idea that greater income compensates for hard work. Effort, in turn, produces benefits beyond the monetary such as flow, mastery, or eudaimonia. Thus, if rich people are somewhat happier than the poor, the differences may be due to the psychological benefits confounded with a high-earning lifestyle. Future research would do well to examine interactions among wealth and effort more closely.

Other components of the good life.We might note what sorts of variables were not included in our studies, as these might be of interest in future research and would certainly provide interesting fodder for our continuing understanding of folk concepts of the good life. These variables include (but are not limited to) gender, religiosity, employment, race and ethnicity, age, living conditions, acts of service to others, etc. Again, our methodology can easily be adapted to examine these other aspects of the life well lived.

Conclusions

1 What People Really Want in Life and Why It Matters 13

happiness, but materialism detract from it?) as well as public policy (e.g., Should governments aim to increase the wealth or happiness of its citizens?).

In short, folk theories really are at the heart of cultural psychology, and questions about the good life are centrally important to positive psychology. Research on folk concepts of the good life remains an important part of a science that aims to bring about social change. As Aristotle noted inNicomachean Ethics, “Shall we not, like archers who have a mark to aim at, be more likely to hit upon what we should? If so, we must try, in outline at least, to determine what it is.” We would suggest that knowing what mark individuals are aiming at provides an important piece of information that is relevant to the question of social progress. Such data tell us about the content of the better lives and better worlds that individuals may aspire to, the sources of their discontent with present circumstances, and perhaps the inspiration for their actions toward those better lives and worlds.

References

Biswas-Diener, R., Kashdan, T., & King, L. (2009). Two traditions of happiness research, not two distinct types of happiness.Journal of Positive Psychology,4, 208–211.

Bruner, J. (1990).Acts of meaning. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Chiu, C.-y, Dweck, C. S., Tong, Y.-y, & Fu, H.-y (1997). Implicit theories and conceptions of morality.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,73, 923–940.

Chiu, C.-y, Hong, Y., & Dweck, C. S. (1997). Lay dispositionism and implicit theories of personality.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,73, 19–30.

Cottrell, C. A., Neuberg, S. L., & Li, N. P. (2007). What do people desire in others? A sociofunc-tional perspective on the importance of different valued characteristics.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,92, 208–231.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990).Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. New York: Harper Perennial.

Diener, E., Diener, M., & Diener, C. (1995). Factors predicting the subjective well-being of nations.

Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,69, 851–864.

Diener, E., Horwitz, J., & Emmons, R. A. (1985). Happiness of the very wealthy.Social Indicators Research,16, 263–274.

Diener, E., Scollon, C. K., Oishi, S., Dzokoto, V., & Suh, E. M. (2000). Positivity and the con-struction of life satisfaction judgments: Global happiness is not the sum of its parts.Journal of Happiness Studies,1, 159–176.

Diener, E., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2002). Very happy people.Psychological Science,13, 80–83. Fletcher, G. J. O. (1995).The scientific credibility of folk psychology. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence

Erlbaum.

Harkness, S., & Super, C. (1996).Parents’ cultural belief systems: Their origins, expressions, and consequences. New York: Guildford Press.

Kashdan, T. B., Biswas-Diener, R., & King, L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 219–233.

Kasser, T. (2004). The good life or the goods life? Positive psychology and personal well-being in the culture of consumption. In A. P. Linley & S. Joseph (Eds.),Positive psychology in practice

(pp. 55–67). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Kasser, T., & Ryan, R. M. (1993). A dark side of the American dream: Correlates of financial success as a central life aspiration.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,65, 410–422. King, L. A., & Napa, C. K. (1998). What makes a life good?Journal of Personality and Social

14 C.N. Scollon and L.A. King

Li, N. P., Bailey, J. M., Kenrick, D. T., & Linsenmeier, J. A. W. (2002). The necessities and luxuries of mate preferences: Testing the tradeoffs.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 82, 947–955.

Lu, L. (2001). Understanding happiness: A look into the Chinese folk psychology.Journal of Happiness Studies,2, 407–432.

Lu, L., & Gilmour, R. (2004). Culture and conceptions of happiness: Individual oriented and social oriented SWB.Journal of Happiness Studies,5, 269–291.

Lucas, R. E., Clark, A. E., Georgellis, Y., & Diener, E. (2004). Unemployment alters the set-point for life satisfaction.Psychological Science,15, 8–13.

Lucas, R., & Dyrenforth, P. S. (2005). The myth of marital bliss?Psychological Inquiry,16, 111–115.

Lucas, R., & Dyrenforth, P. S. (2006). Does the existence of social relationships matter for sub-jective well-being? In K. D.Vohs and E. J.Finkel (Eds.),Self and relationships: Connecting intrapersonal and interpersonal processes(pp. 254–273). New York: Guilford Press. Lucas, R. E., Dyrenforth, P. S., & Diener, E. (2008). Four myths about subjective well-being.Social

and Personality Psychology Compass,2, 2001–2015.

Lucas, R., & Schimmack, U. (2009). Income and well-being: How big is the gap between the rich and the poor?Journal of Research in Personality,43, 75–78.

Myers, D. (2000). The funds, friends, and faith of happy people.American Psychologist,55, 56–67. Myers, D., & Diener, E. (1995). Who is happy?Psychological Science,6, 10–19.

Nickerson, C., Schwarz, N., Diener, E., & Kahneman, D. (2003). Zeroing in on the dark side of the American dream: A closer look at the negative consequences of the goal for financial success.

Psychological Science,14, 531–536.

Rice, T. W., & Steele, B. J. (2004). Subjective well-being and culture across time and space.Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,35, 633.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: A review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. In S. Fiske (Ed.),Annual review of psychology(Vol. 52, pp. 141–166). Palo Alto, CA: Annual Reviews, Inc.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (2008). Know thyself and become what you are: A eudaimonic approach to psychological well-being.Journal of Happiness Studies,9, 13–39.

Scollon, C. N., & Diener, E. (2006). Love, work, and changes in extraversion and neuroticism over time.Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,91, 1152–1165.

Scollon, C. N., Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Biswas-Diener, R. (2004). Emotions across cultures and methods.Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology,35, 304–326.

Scollon, C. N., & King, L. A. (2004). Is the good life the easy life?Social Indicators Research,68, 127–162.

Scollon, C. N., & Wirtz, D. (2010).Is the good life happy, meaningful, or wealthy? Cultural differences and the context-sensitive self. Manuscript under review.

Sheldon, K., & King, L. A. (2001). Why positive psychology is necessary.American Psychologist,

56, 216–217.

Suh, E. M. (2007). Downsides of an overly context-sensitive self: Implications from the culture and subjective well-being research.Journal of Personality,75, 1321–1343.

Suh, E., & Koo, J. (2008). Comparing subjective well-being across cultures and nations: The ‘what’ and ‘why’ questions. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.),The science of subjective well-being

(pp. 414–427). New York: Guilford Press.

Twenge, J. M., & King, L. A. (2005). A good life is a personal life: Relationship fulfillment and work fulfillment in judgments of life quality.Journal of Research in Personality,39, 336–353. Waterman, A. S. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: A eudaimonist’s perspective. Journal of

Positive Psychology,3, 234–252.

Part I

Chapter 2

Think Before You Think

Nic Marks

I work in a think tank, so perhaps it is not surprising that I am suggesting that we all think a little harder about how positive psychology could be a force for (positive) social change. The main question that we are seeking to address at the centre for well-being atnef(the new economics foundation) is what policy making and the economy would look like if their main aim were to promote well-being. In doing so, probably the key thing we aim to achieve is to make an impact whilst simultaneously being robust and grounded in evidence. We want to make a difference – a difference to people’s lives both now and in the future. But before I try to impress upon you why I think we should all take systemic issues a lot more seriously, perhaps it is best if I tell you a little about me, the work we do at the centre for well-being, and why we do it.

You might think it a little strange for a Brit to start off talking about himself; it’s all a bit personal isn’t it? Well, I am of the opinion that all change starts within us. And, as this is a book about social change, it seems relevant to start with my experiences and what I have learnt from them and then move on from there. You can always skip this bit, or indeed this whole chapter, if it doesn’t appeal to you – free will and all that!

Probably one of the first things to say is that I’m not really an academic. In fact, I’m a bit of a failed academic. I tried to do a PhD but simply had neither the patience nor the determination to spend 4 years of my life explaining why it was valid to think of “collective quality of life in an ecological and humanistic context” (which was the working title of my 1-year aborted attempt). Not only was the rigour of a PhD perhaps too arduous for me, but over the years, I (and others) have had to learn to accept that by nature I am a little lazy – or as I prefer to put it – I seek to be efficient with the use of my time and energy! In fact, seeking to be efficient will be a theme that runs through this contribution.

N. Marks (B)

New Economics Foundation, London, UK e-mail: nic.marks@neweconomics.org

17 R. Biswas-Diener (ed.),Positive Psychology as Social Change,

18 N. Marks

Thinking

So I am not an academic as such, but that doesn’t mean I don’t value thinking! When I was at university, I studied mathematics, economics, and management systems, eventually specialising in what was then called “operational research” (OR). OR is basically the study of optimal solutions to complex problems and relies on the use of statistics, mathematical modelling, and simulation techniques. One of the insights I particularly liked was the 80:20 rule – getting 80% of the way to an optimal solution for 20% of the computing effort. This could be my hidden life philosophy! But the thing with the 80:20 rule is that you have tothink before you thinkabout “solving” the problem. You have to think about how to frame the problem, which key parameters to include in the model, and what strategies will be best employed in tackling it.

Operational research also introduced me to the concepts of algorithms and heuris-tics. The key difference is that an algorithm is a precise rule (or set of rules) for solving a problem whereas a heuristic is more of an experience-based technique that approaches a solution; in other words, an algorithm is more precise and formal whereas a heuristic is a bit of a rule of thumb. I’ll come back to algorithms and heuristics later and to the reasons that I tend to favour the latter.

Listening

After university, for some reason, I decided that as well as working as a consultant and a statistician, I also wanted to become a psychotherapist. I am not really sure why I chose to do this, except that my mother worked in the field, but I had great fun doing the training and learnt so much about people (including myself) along the way that it has to be one of the most valuable things I have ever done. In addition to a lot of theories about personal development, the course was also very practical and taught us listening skills and intervention techniques. Therapy is very much a two-way process and one of the major challenges for the therapist is to manage his/her own biases and prejudices, the so-called “counter-transference” during the therapeutic process.

In fact, one of the reasons I have chosen to write this chapter in the first person and give an almost chronological feel to my thinking is to ensure my biases and prejudices are transparent (and challengeable). On my course, I was very struck by one teacher who identified the basic tasks of psychotherapy as three-fold: to listen to your client, to reflect back to them what you have heard, and occasionally to ask challenging questions. In a sense, if I learnt tothink before I thinkfrom OR, then I learnt tolisten before thinkingfrom psychotherapy.

Intervening

2 Think Before You Think 19

Skills and Strategies. It was concerned with three levels of change: personal, group, and organisational. Each theme started with the personal, then later came back to treat the same issue from a group perspective, and then again from an organisational one. It isn’t much of a stretch to think of the next level as social change and I chose to write about these links on many occasions during the coursework. There was quite a bit of debate amongst participants on the course as to whether it should be a Master of Arts (MA) course rather than a Master of Science (MSc) course as it actually was. Perhaps not a distinction that other parts of the world would make, but I think many participants felt that facilitating groups of people was much more of a dynamic relationship, a dance if you like, than a mechanical set of rules to follow, so more an art than a science. I was unsure; for whilst I was deeply engaged with the very experiential dimension of the course, I also loved the brain-food of models and theories!

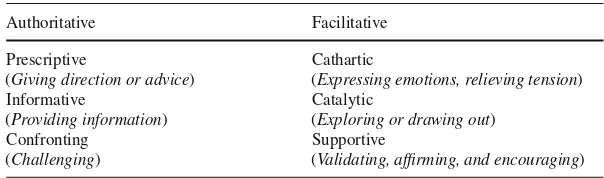

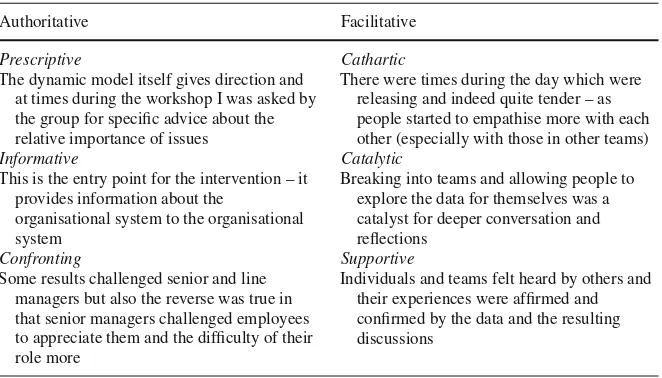

[image:37.439.67.369.367.456.2]At one stage I remember that the tension between facilitation as an art or a science came to a head in the group with many people (probably on this occasion including me) being strongly resistant to a categorisation of interventions model devised by John Heron (one of the original founders of the course who had long since left). It is strange that I was resistant to it, as in retrospect it is one of the models I find most useful. Heron (1990) really, really likes categorisations and quite possibly overuses them in a slightly pedantic way but they can be a simple way of opening up com-plex issues. Anyway, the one I still find useful said that when you are deliberately seeking to promote change at any level, there are two broad types of intervention – authoritative and facilitative – each with three subtypes. Table2.1shows the full categorisation (Heron,1990).

Table 2.1 Heron’s six categories of interventions Authoritative Facilitative

Prescriptive

(Giving direction or advice)

Cathartic

(Expressing emotions, relieving tension) Informative

(Providing information)

Catalytic

(Exploring or drawing out) Confronting

(Challenging)

Supportive

(Validating, affirming, and encouraging)

I found this categorisation helpful as it highlights the validity of many of different styles of intervention whilst encouraging meto think carefully before intervening.

Issues of Primary Importance

20 N. Marks

To help me steer a course through this particular minefield, I have often turned to one thinker who, over the years, has been a sort of mentor to me: Manfred Max-Neef, the Chilean Right Livelihood Award winner and so-called barefoot economist.

In a brilliantly thoughtful paper with a great title – About the pruning of language (and other unusual exercises) for the understanding of social improvement– he sug-gests that a lot of us spend most of our time worrying about issues of secondary importance (Max-Neef,1988). He implores us at this time in history to concentrate on issues of primary importance. So what does he mean by “issues of primary impor-tance”? An example he gives is that a lot of people worry about who is in power and they spend a lot of their effort trying to get someone into a position of power – basi-cally someone more like them, someone with their sort of values – in the hope that once that person gets into power, the world will become more like the world that they want it to become. Max-Neef calls this an issue of “secondary importance” because, he argues, we have tried very many different people in power – we’ve tried moderates, we’ve tried radicals from the left and the right – but the challenges still remain. The issues of primary importance have not been solved by addressing the question of “who is in power”; instead, he suggests, they are more to do with “the structure of power”, i.e., the way that we organise power in society.

Three Global Issues

So what are the issues of primary importance at this time in the early twenty-first century? Obviously different people might have different lists and emphases but quite probably at a systemic level they are all interconnected. For me, there are three main issues.

Perhaps the most obvious issue is that in an era of unprecedented plenty for the rich, more than 3 billion people – about half the world’s population – live on the equivalent of less than $2.50 a day. This is 400 million more than in 1981. The aver-age incomes of the richest 1% of the world’s population are over 100 times those of the poorest 20%. During the same period, health improvement in the developing world, as measured by life expectancy and infant mortality, has slowed dramati-cally. As well as global inequalities, the gains made from the 1920s in reducing the income and wealth inequalities in countries such as the UK and the USA have been reversed in the last 30 years. For example, in the UK the wealthiest 10% have assets of about 100 times that of the poorest 10% (£853,000 compared to £8,800). This is a comparable level of inequality to that of the 1930s. So prob-lem No. 1 is that we live in a world with entrenched poverty and rising global inequalities.

2 Think Before You Think 21

two most serious issues facing the world today, the only issue scoring higher being poverty (69%). Whilst the details of the future impact of climate change are being endlessly debated, it seems clear that we will be entering a period of constraints on our consumption levels driven by an urgent need to reduce carbon emissions. This is without considering the huge loss of b