This ar t icle was dow nloaded by: [ Univer sit as Dian Nuswant or o] , [ Rir ih Dian Prat iw i SE Msi] On: 27 Januar y 2014, At : 01: 04

Publisher : Rout ledge

I nfor m a Lt d Regist er ed in England and Wales Regist er ed Num ber : 1072954 Regist er ed office: Mor t im er House, 37- 41 Mor t im er St r eet , London W1T 3JH, UK

Accounting and Business Research

Publ icat ion det ail s, incl uding inst ruct ions f or aut hors and subscript ion inf ormat ion:

ht t p: / / www. t andf onl ine. com/ l oi/ rabr20

What has the invisible hand achieved?

Ross L. Wat t s aa

Sl oan School , Massachuset t s Inst it ut e of Technol ogy , E-mail : Publ ished onl ine: 28 Feb 2012.

To cite this article: Ross L. Wat t s (2006) What has t he invisibl e hand achieved?, Account ing and Business

Research, 36: sup1, 51-61, DOI: 10. 1080/ 00014788. 2006. 9730046

To link to this article: ht t p: / / dx. doi. org/ 10. 1080/ 00014788. 2006. 9730046

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTI CLE

Taylor & Francis m akes ever y effor t t o ensur e t he accuracy of all t he infor m at ion ( t he “ Cont ent ” ) cont ained in t he publicat ions on our plat for m . How ever, Taylor & Francis, our agent s, and our licensor s m ake no r epr esent at ions or war rant ies w hat soever as t o t he accuracy, com plet eness, or suit abilit y for any pur pose of t he Cont ent . Any opinions and view s expr essed in t his publicat ion ar e t he opinions and view s of t he aut hor s, and ar e not t he view s of or endor sed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of t he Cont ent should not be r elied upon and should be independent ly ver ified w it h pr im ar y sour ces of infor m at ion. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, act ions, claim s, pr oceedings, dem ands, cost s, expenses, dam ages, and ot her liabilit ies w hat soever or how soever caused ar ising dir ect ly or indir ect ly in connect ion w it h, in r elat ion t o or ar ising out of t he use of t he Cont ent .

51

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

What has the invisible hand achieved?

Ross L. Watts*

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Abstract-This paper was commissioned for the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales Information for Better Capital Markets Conference held on 19-20 December 2005. It evaluates the effect of the market on financial reporting recognising that financial reporting and accounting are only parts of a general re- porting, financing and governance equilibrium. That equilibrium is affected by the political process, as well as by capital and other markets. I explain how and why both market and political forces have influenced accounting and financial reporting and provide examples of those influences. Further, I draw implications for accounting standard- setting bodies that desire to change the nature of accounting and financial outcomes. Finally, I predict the effects of the radical standard-setting changes proposed by the FASB and IASB.

1.

Introduction

When I was invited to present at this conference I was asked to address the question: ‘What has the invisible hand achieved? (in financial reporting)’. This is a rather broad question and an impossible one to answer using the evidence in the empirical accounting literature in capital markets alone. Accounting is only one mechanism in financial re- porting and corporate governance and it evolved to fit in with other mechanisms, to be part of a gen- eral reporting, financing and governance equilibri- um. The evidence in the international accounting literature is consistent with such an equilibrium (e.g., Ball et al., 2000). Evaluating the market’s ef- fect on financial reporting requires an understand- ing of the market’s effects on financing and corporate governance, an understanding of the ex- tent to which mechanisms in those areas substitute for, or complement, accounting and financial re- porting. Thus, evidence on the evolution of corpo- rate finance and governance is crucial to any assessment of the market’s achievements in finan- cial reporting

Another factor that is crucial in the assessment of the market is the legal and political environ- ment. Markets require property rights in order to function. The nature of those property rights af- fects financial reporting. For example, the effec- tive limited liability of joint stock companies appears to have influenced debt contracts and the accounting in those contracts and in shareholder reports (see Watts, 2003). When the political process produces changes in property rights, the

*The author is at the Sloan School, Massachusetts Institute of Technology. This paper was presented at the Institute of Chartered Accountants in England and Wales Information for Better Capital Markets Conference in London on 20 December 2005. He is grateful to Ryan LaFond, Karthik Ramanna, Sugata Roychowdhury and Joseph Weber for their comments. All remaining errors are the author’s. E-mail: rwatts@ mit .edu

market adjusts. When shareholders’ rights to bring litigation were changed in the US in the second

half of the twentieth century the market responded by making accounting and financial reporting more conservative despite the antipathy of the Financial Accounting Standard Board (FASB) to-

wards conservatism in financial reporting (see Basu, 1997; Holthausen and Watts, 2001). The na-

ture of financial reporting and accounting that evolves in the market is influenced by the political process and as a result the market demand for fi- nancial reporting also influences the political process (see for example Watts and Zimmerman,

1978; Ramanna, 2005).

The consequence is that the market achieve- ments are a function of economic forces that de- termine both the private economic arrangements and the outcomes of the political process. If pro- posed changes in accounting standards and finan- cial reporting ignore those economic forces and generate unverifiable accounting numbers and the market is unable to prevent those changes occur- ring and/or adjust for them, the market will tend to ignore the resultant financial statements and dis- closures and find other ways to meet the demand for financial reporting.’

Understanding the market’s achievements re- quires an understanding of the market’s responses to the demand for accounting and financial report- ing that is generated both from the market and from the political process. My objectives in this paper are to:

i) explain the how the market has responded in the past to demands in the market itself and to demands that come through the political

process;

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

I Evidence of the market ignoring unverifiable accounting

numbers can be found in Leftwich (1983), who reports that debt contracts exclude goodwill when measuring total assets.

ACCOUNTING AND BUSINESS RESEARCH

dend payments and reduce the agency costs of debt. Such restrictions appeared around the time faceless share trading started in the London stock market.2 Faceless share trading effectively gener- ated limited liability, which in turn made borrow- ing very d i f f i ~ u l t . ~ Dividend covenants in debt contracts made it less likely that funds could be inappropriately distributed to shareholders. Anticipation of losses and lack of anticipation of gains meant that net assets were likely to be a ‘hard’ number. That accounting is similar to cor- porate liquidators’ accounting when making timely distributions to claimholders in a way that does not violate legal priorities.

Individuals also have limited liability in the sense that there is a limit to the penalties that can be imposed on them. That limited liability com- bined with the manager’s limited tenure and hori- zon (e.g., retirement) likely plays a role in accounting’s conservatism (Watts, 2003). The manager has an incentive to recognise gains and defer losses until after he has left the firm to avoid being fired and to earn higher earnings-based com- pensation. Once paid, such compensation is diffi- cult to recover. Conservatism defers recognition of the gains until there is verifiable evidence that the gains exist, or in other words until there is ‘hard’ evidence (see below).

The empirical evidence is consistent with the limited liability of the shareholders (managers) in- ducing asymmetric loss functions for the debthold- ers (shareholders) in contracting with shareholders (managers) (Watts, 2003). These asymmetric loss functions caused efficient debt and compensation contracts and corporate governance mechanisms to use conservative accounting that deferred recognition of gains. That deferral reduced the amount of inappropriate early distributions to both

shareholders and managers.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2.3. Timely reporting

The evidence also suggests that while conser- vatism is part of the efficient private contracting and governance accounting procedures, it does not alone determine the recognition of gains. Timeliness of reporting is also important. Before formal standard-setting there was variation in the timeliness of recognition of gains across indus-

52

ii)

iii)

derive implications for standard-setting bodies and others who want to change the nature of accounting and financial reporting; and

predict the effects of current proposed stan- dards.

To those ends the next section explains how and why private market forces have influenced ac- counting and financial reporting. Section 3 ex- plains how and why the political process and the courts have affected accounting reporting. In

Section

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4,

I provide implications for how account-ing reporting standards should be set. Section 5

predicts the eventual outcomes if the FASB and International Accounting Standards Board (IASB) continue in their apparent resolve to fundamental- ly change the nature of accounting and financial reporting. Finally, Section 6 provides a summary

and my conclusions.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2. Private market forces and financial

reporting

2 . I . Agency costs andJinancia1 reporting

The original development of accounting and fi- nancial reporting appears to be driven by control of agency costs. These costs arise when a princi- pal delegates decision-making ability to an agent who maximises his own welfare rather than that of the principal. There is considerable evidence that writing itself was developed in order to allow for accounting and control of the costs of agency relations such as that between a noble and a stew- ard (de Ste Croix, 1956; Yamey, 1962; Chadwick, 1992). Millennia later, the wardens of English medieval guilds would prepare and present audit- ed financial accounts as a mechanism to reduce agency costs (Watts and Zimmerman, 1983). The early English companies inherited this mecha- nism from the guilds. For example, even in its first years the British East India Company pre- pared annual audited financial statements and presented those statements to its shareholders (Watts and Zimmerman, 1983). Effectively, au- dited financial reporting was a corporate gover- nance mechanism.

2.2. Accounting conservatism

The audited financial statements also played a role in the early English company’s contracts. In Watts (2003) I argue that the use of those finan- cial reports in debt contracts influenced the na- ture of accounting, providing an incentive for conservatism: a higher standard of verifiability for recognition of gains than for losses. This asymmetric recognition of gains and losses gen- erated an understatement of net assets. Effectively it produced a lower bound estimate for net assets that could be used to restrict divi-

Kehl

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(1941:4) reports that in 1620 the corporate charter of the New River Company included a provision that dividendscould be paid from corporate profits only. He also states that those provisions were employed in the rest of the seventeenth century and became increasingly more common in the eigh- teenth century. This time series suggests that the inclusion of the dividend provision in charters was voluntary.

DuBois (1938:95) concludes that

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

de fact0zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

limited liability existed by the 1730s and 1740s and that ‘for England at anyrate, the fact of incorporation either by the Crown or by Parliament came to be the criterion for the extent of limited li- ability’ (p. 96).

International Accounting Policy

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Forum. 2006zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

53tries, presumably induced by 'common law' type principles enforced by auditors."

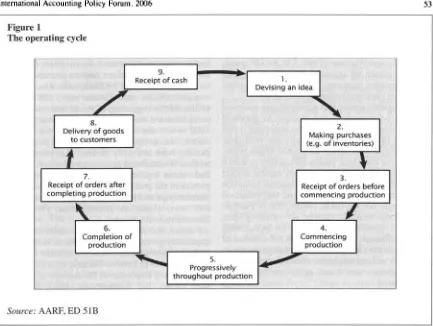

Figure 1 reproduces a graph of the operating cycle produced by the Australian Accounting Research Foundation. The different boxes in the graph can be considered as potential points for the recognition of profit. The most timely recognition would be at point 1 when the entrepreneur first has the idea for a positive net present value project. This is the point that Jeff Skilling (PresidentKO0 and briefly, CEO of Enron) argued should be used for recognising profits and at which Enron did recognise 'profits' in many cases (McLean and Elkind, 2003). The problem with point one is that the expected cash flows for the profits are in the future, very uncertain and not verifiable. Recognition at that point is likely to generate frauds (as in Enron's case).

As one moves around the cycle, the outcome be- comes less uncertain. Historically, accounting waited for the profits to become verifiable. By the beginning of the twentieth century most firms recognised profit at the time title to goods passed, at the time of delivery (point 8). However, in some industries firms were able to recognise profit at an earlier point in the operating cycle, in particular at

points

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5 and 6. Two prominent examples of suchindustries are mining and construction. Until the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Staff Accounting Bulletin (SAB) No. 101 (SEC, 1999),

some mining firms listed on US exchanges still recognised profit at production (Demers et al.,

2005). Why were firms in these industries able to recognise profits earlier than other firms? The ap- parent answer is that the mining firms had con- tracts for the forward sale of their output. The output's sale and its sale price were guaranteed by contract, so recognition of profit at production would not induce overproduction by management to overstate profits (create frauds). In construction, some firms had contracts that gave them guaran- teed payments at various stages of the construction process. This evidence suggests that when the na- ture of the sales contracts made fraud less likely and profits verifiable, efficient private accounting allowed profits to be more timely. Profits were re- ported as soon as they were verifiable.

2.4. The nature

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of the balance sheet and income statementThe emphasis in private contracting is on distri- bution of net assets so the balance sheet is a con- servative estimate of the value of the net assets rather than a measure of firm value (i.e., the bal- ance sheet did not incorporate the value of rents). Intangibles such as goodwill are excluded from the calculation of net assets in debt contracts

See Matheson (1893) for a discussion of the auditors' fights with managers over accounting procedures.

[image:4.540.55.488.77.403.2]54 ACCOUNTING AND BUSINESS RESEARCH

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

(Leftwich, 1983). Consistent with this contracting, before the Securities Acts in the US, goodwill was typically written off the balance sheet as soon as possible, often being reduced immediately to one dollar (Ely and Waymire, 1999).5 In the UK good- will was written off against equity. Accounting in- come measured increases in net assets (excluding intangibles) before dividends.

The probable reason that goodwill was removed from the balance sheet and changes in goodwill were not considered in the income statement is that estimates of goodwill are typically not verifiable. Goodwill and some other intangible assets repre- sent rents or economic profits (the ability to earn a rate of return above the appropriate capital market rate). Their periodic estimation requires valuation of the firm (or part of the firm) and that valuation is frequently not verifiable (Watts, 2003). Further, when firms were in danger of violating debt covenants, goodwill was likely to be approaching zero (Holthausen and Watts, 200 I). Inclusion of goodwill in the balance sheet and changes in good- will in the income statement would make account- ing numbers ‘soft’ and open to fraud and manipulation.

It is important to note that even though market- driven accounting was conservative prior to the es- tablishment of the US Securities and Exchange

Commission (SEC) in 1934

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

, tangible asset valueswere occasionally written up to their market value when the increased asset value was verifiable. Fabricant (1936) reports that in a sample of 208 large listed industrial US firms in the period 1925-1 934 there were 70 write-ups of property, plant and equipment and 43 write-ups of invest- ments. The investment write-ups were likely secu- rities traded in liquid markets where the market value could be observed. Revaluation of property

was associated with financing (Finney, 1935, ch.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

40).

If an independent appraiser had valued the property for refinancing purposes, the appraised value was likely to be verifiable (particularly if the appraiser was employed by the lender). Just as in the operating cycle, market accounting allowed greater timeliness when there was verifiability. The SEC effectively banned asset write-ups in thelate 1930’s (Zeff, 1972:15&160; Walker, 1992)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

2.5. The role offinancial reporting in providing information to the market

As indicated above, the early English companies did present audited financial statements to the shareholders at the annual general meeting. The

tremendous growth of the London stock market in the second half of the nineteenth century caused substantial changes in the auditing of financial statements and the provision of financial reports for investment purposes! From 1844-1900 the

UK company acts did not require an outside audi- tor and from 1856 to 1900 an audit was not even required (Watts and Zimmerman, 1983; Hunt, 1935). At the beginning of the period audits were conducted by non-director shareholders, but by 1900 when the compulsory audit was reintro- duced, ‘the accounts of most of them (public com- panies) were not only audited but were in fact audited by chartered accountants. Indeed, practice had outrun legal minima’ (Hunt, 1935454). The growth of the professional audit firm was a market phenomenon and indeed, the accreditation of audi- tors was a market phenomenon (Watts and Zimmerrnan, 1983).

Further, the audited financial statements were apparently given to non-shareholders. In the 1890s British auditors came to the US to audit US firms raising capital in London because their firms’ rep- utations were important to the success of those is- sues (Watts and Zimmerman, 1983; DeMond, 1951). Stock exchange requirements played a role in the presentation of audited financial statements in the US (see Benston, 1969). Such requirements were introduced not because of governmental reg- ulation but because the exchanges found it to be in their own self interest. Different US exchanges had different requirements allowing variation in the quality of information presented.

Despite the use of audited financial statements for evaluation of investments, prior to the US

Securities Acts the accounting produced by listed companies for the purpose of raising capital was essentially the same accounting produced for con- tracting and control purposes. Daines (1 929:94) describes the dominant objective of accounting as being ‘to reflect that income which is legally avail- able for dividends’. Further, even though the Securities Acts were based on a broader informa- tion role for financial reports, US practice and opinion among accountants was slow to change in that direction. Forty years after the Securities Acts, a 1975 FASB survey found that only 37% of re- spondents agreed with the information role being the basic objective of financial statements. Those disagreeing took the position that ‘the basic func- tion of financial statements was to report on man- agement’s stewardship of corporate assets and that the informational needs of readers was of second- ary importance’ (Armstrong, 1977:77).

State company law dividend restrictions caused the man- agement of some companies not to write-off goodwill because the write-off would prevent them paying dividends.

Between 1853 and 1893 the nominal value of listed secu-

rities on the London stock exchange increased by a factor of

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

14 (Morgan and Thomas, 1962).

Why didn’t accounting take on the broader role suggested by today’s standard-setters and provide a broader range of information and even estimates of the market Of the firm (as imp1icit in

FASB proposals)? Why did the general opinion of

International Accounting Policy Forum. 2006

accountants in the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

US disagree with that broaderview, 40 years after the Securities Acts? My an- swer is that the evidence suggests accounting’s comparative advantage in supplying information to capital markets is something other than produc- ing a broad range of information or an estimate of firm value. It is to produce ‘hard’ verifiable num- bers that discipline other sources of information?

Let us look at the relation between information and the stock market price. The stock market price for a security is the result of the interaction of large numbers of investors all with varying information about the firm. No one investor has all the infor- mation. Those investors buy or sell based on their information. The more confident they are in their information the more they bet and the investors who are successful in gaining and using the infor- mation survive and have more wealth to continue to operate. The result is that the stock price con- tains more information than the information of any single investor (Hayek, 1945). The accountant, or financial reporting in general, cannot hope to pro- duce a range of information anywhere near what is in the price or to generate an estimate of a firm’s equity value that captures much of the information that is in the market price. Despite some anom- alous evidence, the great bulk of the evidence in fi- nance supports this conclusion.

How then does accounting fit into the supply of information to capital markets? The outcomes of events implied by information eventually flow through the company’s cash flows. Accounting does not wait for all the cash flows to occur. For exam- ple, in Figure 1 profit is recognised (at sale or pro- duction) before cash inflows occur. Accounting is more timely than cash flows (e.g., Dechow, 1994), but accounting information in financial statements is still generally verifiable or ‘hard’. Most recent frauds are not due to soft standards, but are the re- sult of a failure to apply existing standards.

If an analyst reports an expected increase in a company’s profitability, the quality of the analyst’s information can be checked by observing whether the company’s accounting income later reflects that predicted increase. Market participants come to learn which analysts are better predictors and better sources of information than other analysts and con- sequently stock prices react more to those analysts’ information. If accounting standard-setters force accountants to include unverifiable value changes in income, income will become noisy and frauds will increase. This will reduce the ability of the market to identify the most reliable analysts and in- deed the most reliable other sources of information.

If accounting financial statements become ‘soft’ so

will the information generated by other sources.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

55

2.6. Market reactions to so)

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

accounting andfinancial reporting

Soft accounting standards generated by standard setters will generate market reactions. Any reduc- tion in the usefulness of financial reporting will provide incentives for private alternative account- ing and financial reporting systems to appear. An example of a private alternative to formal stan- dards is Standard and Poor’s search to identify and report ‘core earnings’ (Business Week Online,

24 October 2002). Increasing frauds due to unver- ifiable numbers will generate increases in US liti-

gation costs and induce conservatism by management (Basu, 1997; Holthausen and Watts, 200 1). Finally, managers will react to dysfunction- al standards by using the political process to change the standards.

The history of US accounting standard-setting is replete with instances of managers and other par- ties using the political process to influence ac- counting standards and indeed to change the accounting standard-setting body. The Securities Acts gave the SEC power to set accounting stan- dards for listed firms’ filings in order (among other things) to reduce the variety of accounting proce- dures. Over the years since, the SEC has delegated the setting of standards first to the Committee on Accounting Procedures (CAP) (1939-1959), then the Accounting Principles Board (APB) (1960-1973) and finally the FASB (1973-?). The inability of the CAP to reduce the diversity of ac- counting procedures, ill-will from management from the attempted elimination of procedures and consequent pressure from Congress was the cause of the CAP’S demise in 1959 (Moonitz, 1974). The APB alienated corporate management, politicians and the financial community with its proposals on business combinations (pooling) and other issues and consequent Congressional pressure caused it to be replaced by the FASB (Zeff and Dharan, 1994:2-3). The FASB’s survival and the consis- tency of US standards with IASB standards

depends heavily on the political process. Standard- setters cannot depart significantly from the market equilibrium without their standards being sup- planted by private alternatives or themselves being replaced by an alternative mechanism via the po- litical process. Finally, the courts’ interpretations of the accounting that results from the standards play a major role in how standards work in prac-

tice.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

~ ~ ~~

’

Lambert (1996) and Ball (2001) also suggest accounting plays a role in disciplining other sources of information.3. Political forces and financial reporting

For convenience, I include the legal system, the political system and regulation in the conduits for political forces affecting accounting and financial reporting.

56

3.1. Legal system

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

There is evidence that US courts significantly in- creased the Conservatism reflected in listed firms’ published financial statements. Informal and for- mal evidence (Holthausen and Watts, 2001) sug- gests US financial statements were conservative before the Securities Acts as expected from the contracting and corporate governance forces act- ing in the market. However, there was relatively little litigation under those acts until the rules for bringing class action suits were changed in 1966 (see Kellogg, 1984; Kothari et al., 1988). The rules change enabled lawyers to act as entrepreneurs in bringing lawsuits and increased litigation signifi- cantly. The legal market responded to the change in rules and caused a large increase in the conser-

vatism of the financial reports

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

- a market responseby corporate managers.

At one level, the explanation for why increased litigation produced more conservatism in the US is relatively simple as Beaver (1993) and Watts (1993) pointed out. The reason is that in securities suits, buyer suits outnumber seller suits by 13 to one (Kellogg, 1984). If a firm overstates its in- come and net assets, a suit is much more likely than if the firm understates its income and net as- sets. Basu (1997) uses periods of changing liabili- ty identified in Kothari et al. (1988) to test and confirm the Beaver and Watts prediction. Holthausen and Watts (2001) confirm the Basu re- sults on a longer period. On the basis of the US lit- igation effect, Ball et al. (2000) predict that financial statements of UK listed companies are less conservative than the statements of US listed companies. They find results consistent with that prediction.

At a deeper level, the explanation for litigation’s effect on conservatism could be related to the con- servatism generated by market accounting. US

courts’ asymmetric treatment of realised losses (buyers’ suits) and foregone profits (seller’s suits) mirrors a similar asymmetry found in regulation by the Federal Drug Administration (FDA) that might also reflect court behaviour (Peltzman, 1976). The FDA acts as though realised deaths or realised side effects of drugs released are more im- portant than lives lost because drugs are not re- leased. Perhaps it is more difficult to produce verifiable evidence of profits that might have been made and lives that might have been saved than to produce verifiable evidence of losses that actually occur and the cause of deaths that actually occur. Whether it is that explanation or whether there is an asymmetric loss function in the public sector as well as in the private sector, accounting financial statements generate asymmetric costs for gains and losses. Given the size of litigation in the US, accounting financial statements and disclosures

(Hutton et al., 2003) are likely to continue to be

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

ACCOUNTING AND BUSINESS RESEARCH

conservative regardless of the standards intro- duced by the FASB.

3.2. The political process and regulation

The political process has significant influence on accounting standards at least in the US (Watts, 1977; Watts and Zimmerman, 1978; Ramanna, 2005) and likely in the UK as well. Congressional concern with standards played a role in the re- placement of the APB by the FASB. Recent FASB examples of Congressional involvement include: SFAS 115 (accounting for securities investments, FASB , 1993); SFAS 123 (expensing employee stock options, FASB, 1995); SFAS 133 (account- ing for derivatives and hedges, FASB, 1998); SFAS 141 (elimination of pooling, 2001a) and SFAS 142 (impairment of goodwill, FASB, 200 1 b)

.

In the last case (SFAS 141 & 142) opponents of the elimination of pooling had a bill introduced into Congress to override the FASB. With that bill in Congress, opponents went to the FASB with a compromise that would eliminate the amortisation of goodwill and replace it with impairment. The FASB adopted the compromise even though the compromise in effect made firms that pooled ‘bet- ter off’ in terms of their objectives: the opponents kept the stronger income that pooling produces by eliminating amortisation; and they gained the stronger balance sheet that purchase generates. The stronger balance sheet can be achieved be- cause the valuations for determining goodwill im- pairment are unverifiable so that impairment can be avoided (Watts, 2000; Ramanna, 2005). The impairment is assessed at the reporting unit level where there is typically no observable equity mar- ket value. Ramanna (2005) is able to predict the positions of firms lobbying on the standards using those firms’ ability to manipulate the estimated values necessary for impairment.

History makes it apparent that standard-setting in the US is constrained by political forces - if the standard is too far from a political equilibrium, it cannot last. The long-term political equilibrium in the US appears to require conservatism, so it is likely that SFAS 142 will not last in its current form. Some of the firms with unverifiable good- will that are underperforming will fail and in the political process part of the blame for failure will be attached to the failure of the accounting meth- ods to recognise that assets were overstated.

Watts (1 977:67) argues that conservatism is the equilibrium in the political process because losses from overstatement of asset values and income are more observable and usable in the political process than foregone gains from understatement of assets and income. This in turn could be due to differ- ences in ability to verify or differences in loss functions (see above), but regardless of reason,

International Accounting Policy Forum. 2006

conservatism’s effects are apparent. The rationale for the Securities Acts was that the NYSE crash in 1929 was due to overstatement of assets and in- come (Benston, 1969). This rationale caused the SEC to ban upward revaluations of assets for 30 years (Zeff, 1972:156-160; Walker, 1992). And, there is other evidence that the SEC is still more conservative than the market: the revenue recogni- tion standards in SAB 101 are more conservative than market forces would dictate. Vogt (2001) points out that in some cases SAB 101 requires less timely recognition than implied by contract law. Certainly, SAB 101 did stop some mining companies from recognising profit at production in circumstances the market had allowed for at least a century (see above).

The Vogt (2001) paper is an example of the lim- its the market places on standard-setters and regu- lators. The paper is aimed at contracting professionals and provides examples of how to write contracts to avoid the over-conservative con- sequences of SAB 101, for example how to con- tract to ensure revenue is recognised at sale with no deferral. At the other end of the spectrum we observe the finance community working hard to allow their clients to avoid constraints on capital- king leases so as to keep debt off the balance sheet and generating new securities to produce ‘instant’ profits (see below).

The bottom line is that in the

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

US, the behaviourof the courts, Congress and regulatory bodies such as the SEC and Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) will ensure that US ac- counting standards will be conservative. This will constrain the FASB’s ability to introduce and sus- tain accounting standards that involve unverifiable asset and income increases. Given that we observe conservatism generated privately by contracting and other market forces in the UK, I would expect similar but perhaps weaker restrictions on stan-

dard-setting there as well.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

51

have a conceptual framework that is flexible enough to accommodate equilibrium accounting methods resulting from the economic and politi- cal forces

4. Implications for accounting standard-

setting and financial reporting reforms

The cumulative evidence on the economic forces acting on accounting via the market and political processes provides strong cautions for those pro- posing to reform or significantly change account- ing and financial reporting. If those proponents want their reforms or changes to work and last, they must ensure those reforms or changes:

anticipate how managers and others will react to any standards or proposed reforms;

require verifiable numbers for financial state- ments;

do not try to value the firm;

allow conservatism; and

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

4.1. Anticipate reactions to standards

If standard-setters or reformers want their stan- dards or reforms to be introduced and to last, they have to look ahead to how various individuals will react to the standards or reforms, particularly man- agers. A good standard or reform is one that works in practice and how it works in practice will de- pend on how managers and others use it.

In Watts (2003) I report an example of a stan- dard-setting body’s failure to anticipate managers’ reactions and their consequences. As a market maker in energy-related contracts and derivatives, Enron management marked those instruments to market (trading securities) and reflected the value changes in earnings used in bonus compensation (McGraw-Hill Inc., 2002). The FASB’s Emerging Issues Task Force (EITF) allowed managers of firms making markets in thinly traded energy-re- lated contracts and derivatives the discretion to choose the ‘bid’ price or the ‘ask’ price for valuing those instruments at the end of a period. As a mar- ket maker (in some cases the only market maker) Enron could determine those prices (Weil, 2001). Weil reports that Enron’s ask prices often were as much as eight times their bid prices. Given such high ask prices would not lead to sales, they pro- duced significantly overstated values and earnings. It is difficult to imagine how any experienced au- ditors on the EITF could not anticipate such an ob- vious result.

4.2. Require verifiability

At present the FASB is proposing to revise SFAS 141 to allow profits to be recognised on ‘bargain purchases’ (FASB, 2005a). These are acquisitions where the fair value of the net assets of the firm ac- quired exceed the acquisition price. Since the fair value of the net assets is determined by the man- agement of the acquiring company this seems to allow unverifiable ‘instant’ profits on acquisitions. Management of more than a few companies are certain to take advantage of this opportunity to overstate and inject noise into their earnings, mak- ing accounting and financial reporting ‘softer’.

In their current state, SFAS 141 and 142 intro- duce unverifiable estimates into accounting (Watts, 2003). They require the recognition of dif- ferent types of intangible assets that in total repre- sent rents. Given that rents are essentially the return to monopoly power, they do not represent individual assets (unless they are separable and saleable in the form of a licence or a taxi medal- lion). Any attempt to allocate rents to individual intangible assets is equivalent to allocating joint

58

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

benefits: no meaningful allocation is possible. Any one allocation of rents is as good as another, so the required allocation provides managers with oppor- tunities to introduce both noise and bias into eam- ings. Earnings become ‘softer’.

The impossibility of meaningful rent allocation appears to be used by managers to avoid goodwill impairment under SFAS 142. That standard re- quires acquired goodwill to be allocated across re- porting units. If there are synergies between the reporting units, there is no meaningful way to make those allocations. This provides managers with the opportunity to locate purchased goodwill

in reporting units that already have large

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

unrecog-nised rents or goodwill (they have grown their own

goodwill). Since impairment is assessed at the re- porting unit level, that unrecognised goodwill will mask any overpayment and consequent goodwill overstatement and significantly reduce the likeli- hood of future impairment.

In addition, the SFAS 142 requirement that, in order to estimate goodwill impairment, managers estimate the value of reporting the unit using dis- counted forecasted future cash flows, forecasted earnings and earnings multiples, or other similar methods also considerably increases the ‘softness’ of earnings. Anyone who has tried to value a growth firm knows how difficult it is to forecast future cash and how large a range of values are possible. With the market value of the reporting unit unobservable, the management’s valuations of those units are certainly not verifiable. The conse- quence is that despite the fact that many firms recognised goodwill impairment in SFAS 142’s transitional year (for big bath and below-the-line reporting reasons) hundreds of firm with a market- to-book ratio less than one did not report impair- ments (Beatty and Weber, 2005). SFAS 142 introduced considerable variation in earnings across firms, variation that is due to lack of con- sistent treatment of goodwill impairment. Earnings became ‘softer’ and noisier.

ACCOUNTING AND BUSINESS RESEARCH

porting compete with the market in this dimen- sion? Concentrating on such estimation to the detriment of providing hard data that help market participants estimate market value seems perverse. It is likely to reduce information in the market- place both by making accounting numbers less meaningful and removing accounting’s discipli- nary role from the market. At a minimum, tradition- al transaction-based financial statements should be retained as one set of information provided.

4.3. Do not try to value the firm

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Earlier in this paper I made the argument that the market value of a listed firm is likely to incorpo- rate more information and be a harder estimate of value than a manager’s unverifiable estimate. Holthausen and Watts (2001) make the same argu- ment. Why should accounting and financial re-

The evidence on the nature of asset revaluations (Fabricant, 1936; Finney. 1935) suggests they were not fraud- ulent. Further, economists consider the cause of the depression

to be trade wars (Kindleberger, 1986) and poor monetary

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

pol- icy (Friedman and Schartz, 1963). By the end of 1929 the DowJones Index had recovered to record a loss for 1929 of only 17% and stock prices continued rising in early 1930. In 1930 President Hoover signed the Smoot-Hawley tariff. raising tar- iffs on dutiable items by 5 2 8 .

4.4. Allow conservatism

In the US, any attempt to ban accounting con-

servatism is sure to fail. Pressures from the courts and from the regulatory and political process will induce many managers and accountants to make financial statements conservative nevertheless. At the same time, a lack of conservatism will allow some managers to generate frauds. The consequent political reaction to such frauds will eventually generate removal of the responsible standards and likely eventual removal of the responsible stan- dard-setting body.

The usual reason for opposing conservatism is that the information provided in financial state- ments should be unbiased and as noise free as practicable. If unbiased and low noise information

in practice is the objective then the response of

some managers to an unverifiable standard should be anticipated and built into the design of the stan- dard. The EITF and FASB examples given above provide strong support for this prescription.

4.5. An accommodating conceptual framework

The US Securities Acts were built on a myth:

that accounting and financial reporting caused the 1929 NYSE crash and the great depression.* That story provided a convenient rationale for the Securities Acts and the appearance that Congress was doing something to remove the causes of those calamities. The rationale also created a de- mand for a conceptual framework to guide the reg- ulation of accounting and financial reporting (Watts and Zimmerman, 1979). The SEC (aware of the substantial variation in existing accounting and reporting and the economic and political costs generated by standardisation) passed that role onto a sequence of private standard-setting bodies. The normative conceptual frameworks that emerged to provide guidance and rationales for choice of ac- counting and reporting procedures do not take ac- count of the market and political processes that determine the nature of accounting and financial reporting. And, it is not apparent that completely open and frank consideration of those forces would be politically viable. However, considera- tion of the forces in determining the framework is essential to prevent the proliferation of standards that stand no chance of achieving their objectives.

International Accounting Policy Forum. 2006

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5. Likely outcome of proposed changes in

reporting

I foresee a number of likely outcomes of the cur- rently proposed changes in financial reporting, given the economic and political forces that deter-

mine accounting practice:

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5.1. International accounting standards

It is difficult to envisage a true standardisation of international accounting standards. First, the US Congress is unlikely to cede that right to an inter- national body. Their demonstrated willingness to intercede in the standard-setting process is not likely to disappear. Lobbying by various groups will continue. International accounting standards have no government to enforce them. Second, the frauds likely to emerge from accounting standards that do not consider manager reactions, the impor- tance of verifiability and conservatism will cer- tainly reinforce Congress’s strong incentives to intervene. Third, having only one set of standards limits the evolution of accounting that works. When large numbers of companies can experiment and invent new methods of accounting, one of those experiments might actually improve finan- cial reporting and lead to other firms imitating the new accounting method. The number of such ex- periments has been reduced enormously by the ex- istence of national standard-setting bodies. Reduction of the number of standard-setting bod- ies that experiment similarly reduces the likeli-

hood of efficient innovation.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

59

Move to firm valuation. After centuries of trans-

action-based financial statements and reporting, the FASB proposes financial reporting to move to a firm valuation approach. Inclusion of intangibles that are intended to capture rents, changes the bal- ance sheet from measurement of the opportunity cost of investment and the abandonment option to measurement of firm value. Schipper (2005) ar- gues that in estimating firm value the FASB imi- tates the market. The imitation comes from the use of discounted cash flows, earnings multiples, etc. However, the strength of market valuation is not the varying forms that market participants use to value firms, but the large numbers of participants with varying information that cause the market to incorporate a wide spectrum of information in the market price. The FASB mistakes the form of mar- ket valuation for its substance. In the past the FASB has acted as though an important function of accounting is to inform market participants, a function consistent with the evidence. This FASB is undertaking an experiment based on the form of the market process not its substance. Reliance on form means the experiment is likely to fail. Unless the SEC or other regulatory bodies intervene promptly, the experiment will generate significant numbers of market frauds.

Correction seems unlikely to occur immediately. The FASB is still writing standards that are in- tended to include fair value (including valuation of the firm) into what is effectively its conceptual framework. On 21 October 2005 the FASB issued

a working draft of SFAS

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

15X

(fair value measure-ments, FASB 2005b) that the FASB intends to be

effective for financial statements beginning after

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

15 December 2006. On 25 January 2006, the FASB issued an exposure draft of a proposed state- ment of financial accounting standards (FASB 2006) that suggests firms be given the option to value certain financial assets and liabilities at fair value, beyond the requirements of SFAS 1 15. That draft states that it is phase 1 of a fair value project. Phase 2 would extend the option to non-financial assets and liabilities and to some financial assets and liabilities excluded from phase 1 .

5.3 Market use offinancial reporting

Debt contracts have increasingly contracted out of a number of GAAP standards (see Watts, 1977; Leftwich, 1983; Beatty and Weber, 2005). If the FASB and IASB continue on their current course, debt contracts may cease to use GAAP-based ac- counting entirely. Similarly, compensation con- tracts currently use many performance measures other than earnings. I expect the relative use of modified GAAP earnings in top management com- pensation to decline if standard-setters continue on their current course.

The declining use of accounting numbers from

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

5.2. Future

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of the FASBThe current FASB seems committed to a course that is likely to be disastrous for the institution. It will either be replaced by a governmental agency

or significantly restructured. The reasons for this prediction are spread through my preceding dis- cussion. Two likely focal points are:

Ability to audit standards. At the last American

Accounting Association meeting a former board member (with no denial from the board members present) publicly declared that it was not the FASB’s responsibility to consider the ability to audit their standards when setting standards. The FASB’s sister institution, the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB), that, like the FASB, is responsible to the SEC is concerned about the ability to audit recent standards such as SFAS 142. When the SEC has to examine specific examples of the problems that non-auditable stan- dards generate (frauds), it is highly likely to take the PCAOB’s side. Evidence of such a reaction is provided by the SEC’s relatively recent SAB 101 that adopts a more conservative revenue recogni- tion standard than market forces generate (see Watts, 2003). Like all regulatory bodies, the SEC has strong incentives to be conservative.

60

the audited financial reports in their traditional contracting role is likely to affect the financial re- ports of private companies. It is entirely plausible that if GAAP-based reports do not meet the con- tracting market test, alternative accounting reports that are audited by non-CAs or CPAs could replace them. Recent CPA ethics cases suggest this is al- ready happening.

If GAAP-based published audited financial statements also fail the market test in providing in- formation for share valuation (as seems likely if they are designed to value equity and produce un- verifiable numbers), individuals who currently use those statements will increasingly turn to other, more reliable, alternatives.

ACCOUNTING AND BUSINESS RESEARCH

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

6. Conclusion

The survival of GAAP-based financial reporting requires that reporting meet economic and politi- cal demands. Injudicious changes in reporting that do not consider economic and political forces will not survive or if they do, that reporting will be a mere formality and not be used for productive pur- poses. In this latter event, other mechanisms will arise to meet the demands ignored by formal re- porting. The result could well be that CPAs or CAs will find themselves replaced by competitive insti- tutions.

References

Armstrong, M. S . (1977). ‘The politics of establishing ac-

counting standards’. Journal of Accountancy,

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

143.76-79. Ball, R. (2001). ‘Infrastructure requirements for an eco-nomically efficient system of public financial reporting

and disclosure’. Brookings- Wharton Papers

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

on Financial Services, 127-169.Ball, R., Kothari, S. P. and Robin,A. (2000). ‘The effect of international institutional factors on properties of ac-

counting earnings’. Journal of Accounting

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

& Economics,29 (February): 1-5

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

1 .Basu, S . (1997). ‘The conservatism principle and the asym- metric timeliness of earnings’. Journal of Accounting &

Economics, 24 (December): 3-37.

Beatty, A. and Weber, J. (200.5). ‘The importance of ac- counting discretion in mandatory accounting changes: an examination of the adoption of SFAS 142’. Journal of

Accounting & Economics. Forthcoming.

Beaver, W. H. (1993). ‘Conservatism’. Working paper, Stanford University (presented at the American Accounting Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA.)

Benston, G. J. (1969). ‘The effectiveness and effects of the SEC’s accounting disclosure requirements’ in H. G. Manne (ed.), Economic Policy and the Regulation of

Corporate Securities. Washington, DC: American Enterprise Institute.

Chadwick, J. (1992). The Decipherment of Linear B. Canto edition. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. Daines, H. C. (1929). ‘The changing objectives of ac-

counting’. Accounting Review, 4 (June): 94-1 10. Dechow, P. M. (1994). ‘Accounting earnings and cash

flows as measures of firm performance: the role of ac- counting accruals’. Journal of Accounting & Economics,

18 (July): 3 4 2 .

Demers, E., Joos, P. and Watts, R. L. (200.5). ‘SAB 101’. Unpublished working paper, University of Rochester.

DeMond, C. W. (1951). Price Waterhouse &

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Co.zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

inAmerica: A history of a public accounting firm. New York: Comet Press. Reprinted by Arno Press, New York,

1980.

De Ste Croix, G. E. M. (1956). ‘Greek and Roman ac- counting’ in A. C. Littleton, and B. S . Yamey (eds.),

Studies in the History of Accounting. Homewood, IL: Richard D. Irwin Inc.

DuB0is.A. B. (1938). The English business company after

the Bubble Act 172&1800. The Commonwealth Fund. Ely, K. and Waymire, G. (1999). ‘Intangible assets and eq-

uity valuation in the pre-SEC era’. Unpublished working paper, University of Iowa.

Fabricant, S . ( 1936). Revaluations of fixed assets,

192.5-1934. National Bureau of Economic Research. Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (1993).

Statement of financial accounting standards no. 11.5.

Accounting for certain investments in debt and equity se- curities. FASB, Norwalk, CT.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (1995).

Statement of financial accounting standards no. 123.

Accounting f o r stock-based compensation. FASB, Norwalk, CT.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (1998).

Statement of financial accounting standards no. 133.

Accounting for derivative instruments and hedging activ- ities. FASB, Norwalk, CT.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (200 1 a).

Statement of financial accounting standards no. 141.

Business Combinations. FASB, Norwalk, CT.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (2001b).

Statement of financial accounting standards no. 142.

Goodwill and other intangible assets. FASB, Norwalk, CT.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (2005a).

Proposed statement of financial accounting standards (Exposure draji). Business combinations, a replacement of FASB statement no. 141. FASB, Norwalk, CT. Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (2005b).

Statement offinancial accounting standards no. 1.5X. Fair value measurements. FASB, Norwalk, CT.

Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB) (2006).

Proposed statement of financial accounting standards. The fair value option forfinancial assets andfinancial li-

Finney, H. A. (1935). Principles of Accounting, Volume 11.

New York, NY: Prentice-Hall.

Friedman, M. and Schwartz, A. J . (1963). A Monetary

History of the United States, 1867-1960. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Hayek, F. A. (1945). ‘The use of knowledge in society’.

American Economic Review, 35: 5 19-530.

Holthausen, R.W. and Watts, R.L. (2001). ‘The relevance of value-relevance literature for financial accounting stan- dard setting’. Journal of Accounting & Economics, 31

(September): 3-75.

Hunt, B. C. (193.5). ‘Auditor independence’. Journal of

Accountancy, 59,453.

Hutton, A. P., Miller, G. S. and Skinner, D. J. (2003). ‘The role of supplementary statements with management earn- ings forecasts’. Unpublished working paper, Tuck School of Business.

Kehl, D. (1941). Corporate Dividends. The Ronald Press Company.

Kellogg, R.L. (1984). ‘Accounting activities, securities prices and class action lawsuits’. Journal of Accounting &

es (Exposure draft,. FASB, Norwalk, CT.

International Accounting Policy Forum. 2006

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Economics, 6 (December): 185-204.

Kindleberger, C. P. (1986). The World in Depression.

1929-1939. Revised and enlarged edition. Berkeley:

University of California Press.

Kothari. S. P., Lys, T.. Smith, C. W. and Watts, R. L. (1988). ‘Auditor liability and information disclosure’.

Journal

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

of Accounting, Auditing and Finance, 3 (Fall): Lambert, R. A. (1996). ‘Financial reporting research andstandard setting’. Unpublished working paper, Stanford University.

Leftwich. R. W. (1983). ‘Accounting information in private markets: Evidence from private lending agreements’. The

Accounting Review, 63 (January): 23-42.

Matheson, E.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

( 1 893). The Depreciation ofFactories, Minesand Industrial Undertakings and Their Valuation .

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Reprinted by Amo Press, New York, 1976.

McGraw-Hill (2002). ‘Enron used mark-to-market ac- counting to hide losses, ex-trader tells Senate’. Inside

F.ER.C.’S Gas Market Report ( I February).

McLean, B. and Elkind, P. (2003). The Smartest Guys in

the Room. New York, NY: The Penguin Group.

Moonitz, M. (1974). ‘Accounting principles -how they are developed’ in R. Sterling (ed.), Institutional Issues in

Public Accounting. Scholars Book Company.

Morgan, E. V. and Thomas, W. A. (1962). The Stock

Exchange: Its History and Functions. Elek Books. Peltzman, S. (1976). ‘Towards a more general theory of

regulation’. Journal of Law and Economics, (August): 21 1-240.

Ramanna, K. (2005). ‘The political economy of financial reporting standards: evidence from the business combina- tions project’. Working paper, University of Rochester. Schipper, K. (2005). ‘Fair values in financial reporting’.

Unpublished working paper (presented at the American Accounting Association Annual Convention, San Francisco, CA).

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) ( 1999). 307-339.

61

Accounting Bulletin (SAB) No. 101. SEC, Washington,

DC .

Vogt, R. V. (2001). ‘SAB 101: Guidance on contract is- sues’. Contract Magazine (June).

Walker, R. G. (1992). ‘The SEC’s ban on upward asset revaluations and the disclosure of current values’. Watts, R.L. (1977). ‘Corporate financial statements, a product of the market and political processes’. Australian

Journal of Management, 2 (April): 53-75.

Watts, R.L. (1993). ‘A proposal for research on conser- vatism’. Unpublished working paper, University of Rochester (presented at American Accounting Association Annual Meeting, San Francisco, CA). Watts, R.L. (2003). ‘Conservatism in accounting Part I: ex-

planations and implications’. Accounting Horizons, I7 (September): 207-22 I .

Watts, R.L. and Zimmerman, J. L. (1978). ‘Towards a pos- itive theory of the determination of accounting standards’.

Accounting Review, 53 (January): 112-134.

Watts, R.L. and Zimmerman. J. L. (1979). ‘The demand for and supply of accounting theories: The market for excus- es’. Accounting Review, 54 (April): 273-305.

Watts, R.L. and Zimmerman, J . L. (1983). ‘Agency prob- lems, auditing and the theory of the firm: Some evidence’.

Journal of Law and Economics, 26 (October): 613-634. Weil, J. (2001). ‘After Enron, “mark to market” accounting

gets scrutiny’. Wall Street Journal, (4 December). Yamey. B. S. (1962). ‘Some topics in the history of finan-

cial accounting in England 1500-1900’. In W. T. Baxter and S. Davidson (eds.), Studies in Accounting Theory.

London, UK: Sweet and Maxwell.

zyxwvutsrqponmlkjihgfedcbaZYXWVUTSRQPONMLKJIHGFEDCBA

Zeff. S. A. (1972). Forging Accounting Principles in Five Countries: A History and Analysis of Trends 1971. Arthur

Andersen Lecture Series. Champaign, IL: Stipes Publishing Company.

Zeff, S. A. and Dharan, B. G. (1995). Readings and Notes

on Financial Accounting, fourth edition. New York. NY

Abacus, 28: 3-35.

‘Revenue recognition in financial statements’. StafS McGraw-Hill, Inc.