Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at

http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=vjeb20

Download by: [Universitas Maritim Raja Ali Haji], [UNIVERSITAS MARITIM RAJA ALI HAJI

TANJUNGPINANG, KEPULAUAN RIAU] Date: 11 January 2016, At: 18:35

Journal of Education for Business

ISSN: 0883-2323 (Print) 1940-3356 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/vjeb20

Mission-driven expected impact: Assessing

scholarly output for 2013 Association to Advance

Collegiate Schools of Business standards

Laurel R. Goulet, Kevin J. Lopes & John Bryan White

To cite this article: Laurel R. Goulet, Kevin J. Lopes & John Bryan White (2016) Mission-driven expected impact: Assessing scholarly output for 2013 Association to Advance

Collegiate Schools of Business standards, Journal of Education for Business, 91:1, 11-18, DOI: 10.1080/08832323.2015.1108280

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1108280

Published online: 23 Nov 2015.

Submit your article to this journal

Article views: 18

View related articles

Mission-driven expected impact: Assessing scholarly output for 2013 Association

to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business standards

Laurel R. Goulet, Kevin J. Lopes, and John Bryan White

U.S. Coast Guard Academy, New London, Connecticut, USA

ABSTRACT

As of the 2016–2017 academic year, all schools undergoing Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business accreditation will be assessed on the new standards that were ratified in 2013, which include the assessment of the impact of portfolios of intellectual contributions. The authors discuss key ideas underlying a business school’s research portfolio, its alignment with its mission, and its expected impact. Next the authors leverage these ideas to develop a model of mission-guided expected impact. They then show how the model can be operationalized for the case of an undergraduate-only business school. The authors conclude with a discussion of the potential contribution of our model.

KEYWORDS

AACSB; assessment; scholarly impact

While many business schools have well-established quality standards for scholarship, many struggle to define and assess the impact of that scholarship. It is

important to note that by the academic year 2016–

2017 all schools undergoing Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business (AACSB) accreditation visits should be using the 2013 standards, which include assessing the impact of faculty scholarship

(AACSB,2013a).

The role of faculty scholarship in business schools has followed an evolving path since the creation of the AACSB in 1916. Faculty scholarship in the accredita-tion process has changed dramatically over the years and the phrase publish or perish certainly applied to business professors. In spite of the changes in faculty scholarship requirements, one aspect of the accredita-tion process has remained constant—to ensure that faculty are qualified to deliver management education at a high level.

In this study we show how a small, undergraduate-only business program at a public institution devised such a system. We recently experienced our 2-day team visit, so this system has been scrutinized in a real-life sce-nario. Furthermore, our visit team agreed that our method of scholarship assessment was an appropriate application of the mandate on scholarship from the AACSB.

Background

Historically, AACSB standards focused on inputs instead of outputs when accrediting business schools. The stand-ards assumed that if a business school had sufficient resources, then its output would be a creditable business degree. Thus, accreditation standards focused on ade-quate funding, a suitable library, and an adeade-quate quan-tity of business faculty members (size of credentialed faculty). With adequate resources in place, scholarly out-put was expected to organically emerge and serve as an engine for the continuous improvement of the business school’s program(s).

Over time, the standards began to increase the focus on the quality of inputs. The quality of a business school faculty was associated with its capacity to generate schol-arly output. If enough individual business faculty mem-bers had productive research agendas, then their combined scholarly output was expected to make an impact underlying continuous improvement. From the faculty’s perspective, this meant that a terminal degree in

field was no longer a sufficient indicator of their qualifi -cation. A terminal degree AND recent scholarly activity became the keys to maintaining an academically

quali-fied status. At the school level of analysis, the expectation that scholarly output would result in the desired level of impact reinforced an accreditation-driven focus on

CONTACT John Bryan White [email protected] U. S. Coast Guard Academy, Department of Management, 27 Mohegan Ave., New London, CT 063200, USA.

Color versions of one or more of thefigures in this article are available online at www.tandfonline.con/vjeb. This article not subject to U.S. copyright law.

© 2016 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

2016, VOL. 91, NO. 1, 11–18

http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2015.1108280

inputs. Individual faculty members were categorized as either academically qualified (AQ) or professionally qualified (PQ). AQ faculty had a terminal degree and adequate research output, while PQ faculty maintained their relevance through professional activities such as training or conferences. To earn or maintain accredita-tion, a school needed a minimum of 50% of its faculty to be AQ, and 90% to be either AQ or PQ (AACSB,2009).

Different business schools were recognized to have different mission characteristics, allowing them to meet the needs of different stakeholders. Over time a business school’s mission characteristics should shape its schol-arly output, focusing the expected impact in areas that are aligned with the school’s strategies. From an input perspective, if individual faculty members participated in the management and governance of a business school, then their scholarly output could be assumed to be aligned with the business school’s mission. To this end, faculty members were categorized as either participating faculty or supporting faculty. Participating faculty were individuals who taught full-time as well as performed other duties such as advising/mentoring students and serving on committees. Adjunct faculty members were the most common example of supporting faculty. A school had to ensure at least 75% percent of the school’s teaching (and at least 60% percent of the teaching in each discipline) was delivered by participating faculty.

The maturation of the AACSB accreditation standards has resulted in the increased granularity of input meas-ures, as well as a significant shift toward including output and self-defined mission alignment measures in the assessment of the business school’s program(s). For

example, current AACSB standards (AACSB, 2013b)

now divide a business school’s qualified faculty into four categories instead of two: scholarly academic (SA), prac-tice academics (PA), scholarly practitioners (SP), and instructional practitioners (IP). At least 90% of the fac-ulty must be in one of the four categories. In addition, at least 40% of the faculty must be SA, and 60% must be either SA, PA, or SP.

SA and SP faculty members are now required to pro-duce a qualifying level of scholarly output that is expected to create an impact that is aligned with their business school’s mission characteristics (AACSB, 2013b). Connecting scholarship, mission, and impact involves understanding the quantity, purpose, quality, and impact of scholarly output. AACSB, however, does not define how such a connection must be established. It is therefore up to the individual school to develop a sys-tematic connection relating output measures for scholar-ship to mission characteristics and expected impact. What follows is how we addressed this issue for our 2014 AACSB accreditation visit.

The context of scholarship impact

The phenomenon of determining the impact of faculty research is not limited to AACSB International, but it is a relatively recent occurrence. Conceptually, at least, impact is generally defined in one of two ways: (a) as the influence of the research on other academic research (Engemann & Wall, 2009; Harland, 2013; Lazaroiu, 2009) or (b) as the transfer of knowledge of academic research results to the field (Agrawal & Henderson, 2002; Wright, Milne, Price, & Tose, 2013). Essentially, the measure of impact seeks to answer the question: “Does our research have any impact on other researchers or on practice in the real world?”

In what follows wefirst discuss key ideas underlying a business school’s portfolio, its alignment with mission, and its expected impact. Next we leverage these ideas to develop a model of mission-guided expected impact. We then show how the model can be operationalized for the case of an undergraduate-only business school. We con-clude with a discussion of the potential contribution of our model.

Scholarly output

Scholarly inquiry is a school’s engine for innovation. While an individual faculty member’s rolling five-year portfolio of intellectual contributions has routinely been assessed, the 2013 standards now require the school to provide an organization-level analysis of scholarly out-put. A business school’s aggregate portfolio of intellectual contributions is its scholarly output. How a business school ought to aggregate and assess its school level port-folio of scholarly output is not entirely clear.

Business schools are well practiced in providing a portfolio of evidence summarizing an individual’s intel-lectual contributions over the most recent 5-year review period. Each individual intellectual contribution has the potential to advance the theory, practice, and/or the teaching of business and management. The AACSB defines corresponding categories of basic or discovery scholarship, applied or integration/ application scholar-ship, and teaching and learning scholarship. At the

indi-vidual level of analysis, each faculty member’s

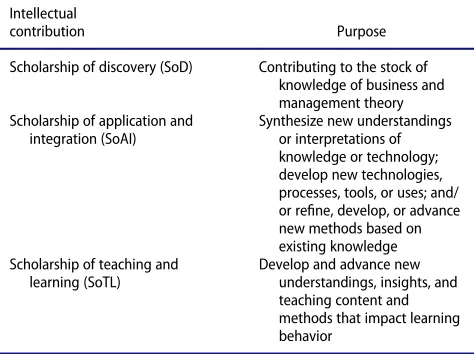

intellectual contribution is placed in one of these catego-ries. Table 1displays the categories of scholarly inquiry and the purpose an intellectual contribution in that category.

Aggregating all individual faculty contributions into a single annual table creates an annual portfolio of schol-arly output. Sorting this portfolio by intellectual contri-bution category creates a three-category portfolio that is aligned with the three major purposes of scholarly 12 L. R. GOULET ET AL.

inquiry. Leveraging the categories defined by the AACSB allows a business school to consider whether or not its scholarly output portfolio is reflective of its mission characteristics.

Mission characteristics

According to AACSB Standard 1,

The school articulates a clear and distinctive mission, the expected outcomes this mission implies, and strategies outlining how these outcomes will be achieved. The school has a history of achievement and improvement and specifies future actions for continuous improvement and innovation consistent with this mission, expected outcomes, and strategies. (AACSB,2013b, p. 14)

One of the bases for judgment is“The school’s mis-sion, expected outcomes, and strategies clearly define the school’s focus on quality intellectual contributions that advance the knowledge, practice, and teaching/pedagogy of business and management.”Guidance for documenta-tion includes “Describe how the mission, expected out-comes, and strategies clearly articulate the school’s areas of focus in regards to educational activities, intellectual contributions, and other activities.”

Each business school is unique in the role that it plays in local, national, and global economies. The Impact of Research Task Force noted that a business school has the right and responsibility to define its research priorities (AACSB, 2008). Standard 2 indicates that the overall impact of intellectual contributions should reflect the strategic focus identified by the institution’s mission statement and strategic plan. From this strategic perspec-tive, mission characteristics should guide the expected impact of scholarship, and therefore be a part of the model used for assessing the expected impact of scholarly output.

Expected impact

While every business school is unique, it is helpful to consider the relationship between mission characteristics and expected impact. Common areas where business schools vary include their emphasis on scholarship, their degree program model, their master’s and doctoral pro-grams, and their emphasis on executive education. The

Impact of Research Task Force (AACSB, 2008) used

these characteristics to identify four common business school models (A–D). The intended impact of each cate-gory of scholarly output—theory, practice or teaching— was prioritized to align with each model. For example a small undergraduate-only business school (Model A) may have intended impact to teaching as its highest pri-ority, to the practice of business and management as a moderate priority, and to theory development as its low-est priority. Alternatively, a large business school may have theory development as its top priority, the practice of business and management as a moderate priority, and intended impact to teaching as its lowest priority. The Task Force’s table summarizing this relationship is reproduced inTable 2.

The purpose of the Task Force’s report was not to force all business schools into one of four models. Rather, their goal was that any output metric estimating expected impact of scholarly output must align with the mission-driven business model of the individual business school.

A model for assessing mission directed expected impact

AACSB’s categorization of all intellectual contributions into three purpose-driven categories creates an opportu-nity to capture the alignment of a business school’s scholarly output and its mission characteristics. Each of these categories has a different purpose; to generate and communicate new knowledge or methods, to synthesize interpretations of knowledge or technologies, or to develop and advance teaching methods. Impact is con-cerned with the difference made or innovations fostered by intellectual contributions (e.g., what has been changed, accomplished, or improved).Table 3shows the categories of intellectual contribution, the purpose of that category, and the intended impact of that category.

Standard 2 requires schools to produce “high-quality intellectual contributions that are consistent with its mis-sion, expected outcomes, and strategies that impact the theory, practice, and teaching of business and manage-ment”(AACSB,2013b). While the unguided portfolio of scholarly output produced by a business school in any given year would clearly be expected to make some

Table 1.Categories of scholarly output.

Intellectual

contribution Purpose

Scholarship of discovery (SoD) Contributing to the stock of knowledge of business and management theory Scholarship of application and

integration (SoAI)

Synthesize new understandings or interpretations of knowledge or technology; develop new technologies, processes, tools, or uses; and/ or refine, develop, or advance new methods based on existing knowledge Scholarship of teaching and

learning (SoTL)

Develop and advance new understandings, insights, and teaching content and methods that impact learning behavior

impact, Standard 2 assumes the mission characteristics and resulting strategies of a business school provide the conditions for scholarly output development. The inter-action between a business school’s scholarly output and its mission characteristics affects the strength of the rela-tion between scholarly output and expected impact. This

systematic connection linking scholarly output, mission characteristics, and expected impact is graphically repre-sented inFigure 1.

When designing a model for measuring mission-guided expected impact, the weighting of the three cate-gories of scholarly output (discovery [SoD], application/ integration [SoAI], and teaching/learning [SoTL]) must align with individual business school mission character-istics, strategic outcomes, and the resulting prioritization between goals for developing theory, practice, and teach-ing. A business school can use its unique mission charac-teristic weighting of impact expectations to code its portfolio of scholarship output. The interaction between the mission of the business school and the composition of the portfolio of scholarly output can then be assessed.

In order to adequately anticipate and support a port-folio of scholarly output, a business school must use additional categories and weightings to measure expected impact. The Impact of Research Task Force

Report (AACSB, 2008) suggests the use of several

Table 3.Categories of scholarly output.

Intellectual

contribution Purpose Intended impact

Scholarship of

Table 2.Relationship between mission characteristics and expected impact.

Characteristics Model A Model B Model C Model D

Scholarship emphasis Scholarship emphasizes learning and pedagogical

General model of degree program emphasis

Mix of undergraduate programs that emphasize entry-level professional preparation

Mix of undergraduate and master’s programs that emphasize professional preparation

Mix of master’s programs that emphasize professional preparation and specialist careers

Mix of master’s and doctoral programs that emphasize professional preparation, specialist careers, and research

MBA/specialized master’s emphasis

No MBA/Master’s programs Small to medium sized MBA programs with significant part- time student and practitioner focus

Medium to large MBA programs, including full-time MBA and executive MBA

Large traditional student MBA, executive MBA, specialized master’s programs Doctoral program emphasis No doctoral program No doctoral program Doctoral program that

emphasizes practice and/or places graduates in teaching focused schools or industry

No or only minimal faculty deployment to support

Significant faculty deployment to support

Figure 1.Linkage between scholarly output and expected

impact.

14 L. R. GOULET ET AL.

additional categories and ratings when measuring expected impact. It states:

For every faculty member with responsibilities to con-tribute to a school’s portfolio of intellectual contribu-tions (which for accreditation purposes must be a substantial cross–section of faculty) the school should understand and track: (a) the focus of the effort (what is intended to be accomplished); (b) the product form to be produced (books, articles, sets of speeches involved); (c) the audience to be influenced by the effort (a disci-pline academic community, practitioners); and (d) the appropriate metrics to be used to assess impact on that audience (what constitutes evidence of “success”). (AACSB,2008, p. 32)

The expected impact of a business school’s research is defined by the focus of the effort, the product form, the target audience, the scope, and the distribution or adop-tion of its scholarship outputs.

Focus of effort

At an aggregate level of analysis, a business school pro-vides areas of focus for what is to be accomplished. While an individual faculty member’s academic freedom to contribute is in no way limited, providing focal areas allows a business school the opportunity to coordinate talent, provide developmental guidance, and tailor resource support.

Product form

It is important for a business school to understand the common product forms comprising its scholarly output portfolio. It can guide faculty development, provide resources, and solicit opportunities. It can increase the expected impact of the business school’s scholarly out-put. The product form of scholarly output may be: articles, presentations, or other (cases, books, profes-sional magazines).

Target audience

Scholarly output targets one of three different audien-ces—academics, practitioners, or students. Weighting the preferred target audiences as high, moderate, or low provides alignment between the business school’s mis-sion characteristics and the target audience:

Academics: SoD

Discovery of new knowledge (i.e., original

research) Practitioners: SoAI

Development of technologies, methods, materials, applications, or uses that apply current research and technology

Development of new applications for general the-ories and conceptual frameworks

Integration of existing knowledge, ideas, and

research, leading to a new understanding or com-prehensive framework

Students: SoTL

Development of technologies, methods, materials, applications, or uses that enhance the effective-ness of teaching and learning busieffective-ness and man-agement (AACSB, 2013b, p. 16).

Scope

Intellectual contributions may target change, accom-plishment, or improvement across a local, a national, or often an even wider scope. A contribution that creates an impact at a local level is narrower in scope than a contri-bution that is widely applicable across all organizations. Weighting the following categories of scope as high, moderate, or low provides alignment between the busi-ness school’s mission characteristics and research expect-ations: global/all organizations, national/government-wide, and local/narrow.

Distribution and adoption

Business schools strive to grow by promoting, enhancing, and leveraging scholarly activity. Primary outlets for dis-tribution and adoption of scholarly output where

intellec-tual contributions can consistently create change,

accomplishment or improvement may be selected. How-ever, diverse faculty interests and a relatively broad scope of academic disciplines are likely to result in the commu-nication of intellectual contributions through various other outlets. With limited faculty andfinancial resources available for research activities, a business school may be reluctant to identify lists of targeted publications. We argue that distribution should instead be measured on a case-by-case basis. Weighting the following categories as high, moderate, or low provides alignment between the business school’s mission characteristics and research expectations for distribution and adoption: known adop-tion, extended distribuadop-tion, and local distribution.

Measures have been developed to systematically assess and optimize the expected impact of a business school’s scholarly output given its mission characteristics. Next, a case is presented demonstrating one successful use of these measures for peer team review under the 2013 AACSB standards.

The case of our institution

Our institution is a small, undergraduate-only, teaching-focused institution. In many cases the business school

faculty is one person deep in a discipline (e.g., finance, human resources, marketing, strategy). Therefore, com-piling lists of target journals is not realistic or meaningful for us. The business school does not offer a master’s or doctoral program, and does not deploy faculty to support executive programs.

The business school defines the impact of its research by the focus of the effort, the product form, the target audience, the scope, and the distribution or adoption of its scholarship outputs. In an effort to capitalize on the different faculty talents, and to provide guidance for developmental purposes, business school support for scholarship is generally focused around: leadership and mentorship, crisis leadership, organizational effective-ness, and scholarship of teaching and learning.

The primary mission of our institution is the develop-ment of leaders of character. Thus, leadership and men-toring are seen as central to the mission. Crisis leadership is a part of our institution’s DNA. As a teach-ing institution, the SoTL is supportive of our mission. Intellectual contributions that do not align with our focus of effort are not mission-related.

Product form

The product form of the intellectual contribution is important to guiding development and providing resour-ces to support individual or team outputs. The business school anticipates the following product forms: peer-reviewed articles, presentations, and other (cases, books, professional magazines).

Target audience

Intellectual contributions produced by the business school are designed to target three different scholarship discipline categories: SoAI (as our goal is to produce scholarship that is relevant), SoTL (as we are an under-graduate teaching institution), and SoD (as we remain open to the idea of helping to address emergent and unknown needs).

The impact of scholarly output will be measured and assessed over the nextfive years at the school-wide level of analysis to ensure alignment with the strategic focus of our institution and the business school mission statement.

The following weighting provides alignment between our institution’s strategy and the business school’s research expectations:

Practice (SoAI): higher;

Teaching (SoTL): moderate; and

Theory (SoD): lower.

Scope of impact

The following weighting provides alignment between the Our Institution’s strategy and the business school’s research expectations:

Global/all organizations: higher;

National/government-wide: moderate; and

Local/narrow: lower.

Distribution and adoption

Our institution strives to grow as a nationally prominent intellectual asset by promoting, enhancing, and leverag-ing scholarly activity. However, the combination of a small faculty and a relatively broad scope of academic disciplines results in the communication of intellectual contributions through various outlets. The following weighting provides alignment between our institution’s strategy and the business school’s research expectations: known adoption: higher, extended distribution: moder-ate, and local distribution: lower.

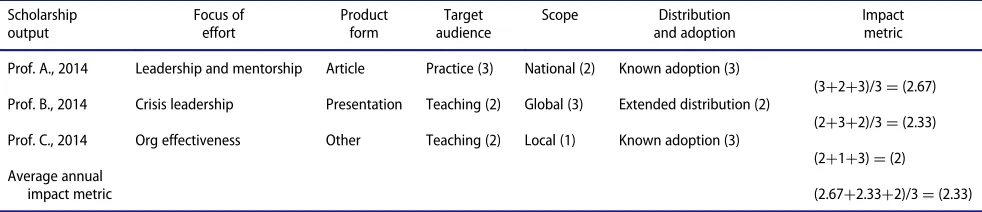

Weighted factors representing the target audience, scope, and distribution and adoption are assigned the following numerical values: higher D 3, moderate D 2, and lowerD1.

The numerical values for target audience, scope, and distribution and adoption are averaged to create an impact metric for each individual scholarship output. Our institution’s aggregate scholarly output target is set

Table 4.Department of management quality impact of scholarship example.

Scholarship output

Focus of effort

Product form

Target audience

Scope Distribution and adoption

Impact metric

Prof. A., 2014 Leadership and mentorship Article Practice (3) National (2) Known adoption (3)

(3C2C3)/3D(2.67) Prof. B., 2014 Crisis leadership Presentation Teaching (2) Global (3) Extended distribution (2)

(2C3C2)/3D(2.33) Prof. C., 2014 Org effectiveness Other Teaching (2) Local (1) Known adoption (3)

(2C1C3)D(2) Average annual

impact metric (2.67C2.33C2)/3D(2.33)

16 L. R. GOULET ET AL.

during the annual assessment and planning meeting. School-wide aggregate scholarly output is measured for each academic year by averaging the impact metrics from all scholarship outputs produced by the business school.

Process

Table 4 provides an example of how the mission-driven expected impact of scholarly output from the business school could be represented for the year 2014. First, intellectual contributions are indexed by author. Next, each intellectual contribution is catego-rized in terms of its focus, product form, target

audi-ence, scope, and distribution/adoption. Then a

weighted numerical value is assigned to the target audience, scope, and distribution and adoption catego-ries. An Impact Metric is then calculated for each scholarly output. Finally, the impact metrics from all of the scholarly outputs are averaged to attain an Annual Impact Metric at the school-wide level of anal-ysis.Table 4demonstrates a school-wide scholarly out-put portfolio that that has an Annual Impact Metric of 2.33.

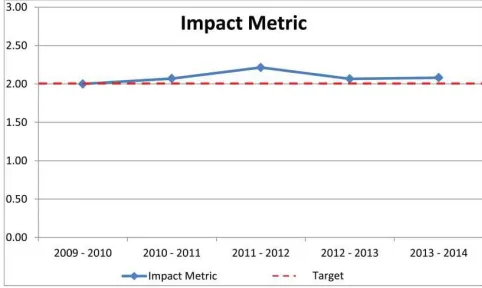

Using the analysis model demonstrated in Table 4, our institution was able to assess its five-year trend in aggregate expected impact. The following assessment data was provided to a peer review team evaluating mis-sion alignment and the expected impact of scholarly out-put. The peer review team found the report to be a successful way of meeting the new 2013 AACSB standards.

The business school targeted an aggregate impact metric of 2.0. The 2013–2014 aggregate impact metric was 2.08. The five-year results from their school-level analysis are summarized inFigure 2.

The model demonstrated inTable 4was also used it identify alignment with mission focus. During the 2013– 2014 academic year the business school produced 41 intellectual contributions, with 39 of the 41 (95%) tied to the mission.

Conclusion

We have reviewed key ideas underlying a business school’s portfolio, its alignment with mission, and its expected impact. It leveraged these ideas to develop a model of mission-guided expected impact. Finally, it showed how the model has been successfully operation-alized for the case of an undergraduate-only business school.

The model provides a systematic methodology for addressing the 2013 AACSB Standard 2. Standard 2 pre-sented a new challenge for accreditation; it required a school-level of analysis that had not been required before. It required systematic consideration of aggregate scholarly output, its interaction with mission characteris-tics, and its expected impact. Our model meets this standard.

What is known is that one peer review team accepted the model as a reasonable method of assessing scholarly impact. Having been validated in a single case, it remains to be seen if this method can be generalized to other model A business schools, and beyond. Our hope is to make the process available to other business schools so it can be refined, expanded, adapted and improved through many more peer review team visits.

References

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business Interna-tional (AACSB). (2008).Final report of the AACSB Interna-tional impact of research task force. Retrieved from http:// www.aacsb.edu/~/media/AACSB/Publications/research-reports/ impact-of-research.ashx

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business Interna-tional (AACSB). (2009).AQ/PQ status: Establishing criteria for attainment and maintenance of faculty qualifications: An interpretation of AACSB accreditation standards. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/~/media/AACSB/Publi cations/white-papers/wp-aq-pq-status.ashx

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business Interna-tional (AACSB). (2013a).2003 to 2013 accreditation stand-ards transition timeline. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb. edu/en/accreditation/standards/2013-standards/transition-timeline.aspx

Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business Interna-tional (AACSB). (2013b).Eligibility procedures and accredi-tation standards for business accrediaccredi-tation. Retrieved from http://www.aacsb.edu/~/media/AACSB/Docs/Accreditation/ Standards/2013-business-standards.ashx

Figure 2.Five year school-level expected impact trend.

Agrawal, A., & Henderson, R. (2002). Putting patents in con-text: Exploring knowledge transfer from MIT.Management Science, 48,44–60.

Engemann, K. M., & Wall, H. J. (2009). A journal ranking for the ambitious economist.Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis Review, 91,128–139.

Harland, C. M. (2013). Supply chain management research impact: An evidence-based perspective. Supply Chain Management: An International Journal, 18,483–

496.

Lazaroiu, G. (2009). Constructing journal rankings and the reliability of prestigious scholarly journals. Economics, Management and Financial Markets, 4,111–115.

Wright, D., Milne, R., Price, A., & Tose, N. (2013). Assessing the international use of health technology assessments: Exploring the merits of different methods when applied to the National Institute of Research Health Technology Assessment (NIHR HTA) pro-gramme. International Journal of Technology Assess-ment in Health Care, 29,192–197.

18 L. R. GOULET ET AL.