Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 492

CMC IN ELT: THEORIES AND PRACTICES

Dian Toar Y. G. Sumakul

Abstract

The internet has changed the way people communicate. Particularly after the introduction of Web 2.0 technology, which triggered the emergence of various Social Networking Sites (SNSs), the rate of online interactions has increased. Now, people write more in the internet. This online writing is known as CMC, or Computer-Mediated Communication. Harnad (1991) labels CMC as the 4th revolution in human communication, after language, writing, and print. Furthermore, incorporating both spoken and written communication features, Beauvois (1998) labels it as „conversation in slow motion‟, while Crystal (2001)

calls it „netspeak‟. Correspondingly, it is also considered as the hybrid (Kost,

2008) and bridge (Handley, 2010) of the two traditional modes of communication: speaking and writing. This nature of CMC is then the starting point of the idea to bring CMC at the foreground of ELT (English Language Teaching), particularly of EFL (English as a Foreign Language) Teaching. This paper is intended to provide theoretical framework that support the application of CMC in ELT. For this purpose, theories on CMC will be reviewed and findings from relevant research about the advantages of CMC in language learning will also be discussed. The second aim of this paper is to present practical suggestions of how CMC could be integrated in ELT. Within this scope, examples of the use of CMC in ELT, through a number of online tools, will also be elaborated.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the fact that there have been studies looking at how to use CMC (Computer Mediated

Communication technologies into classrooms, one criticism to the idea of bringing these

technologies into the classrooms is the nature of the CMC use itself. Although it is true that

the internet has been part of our students life, some studies suggest that the use of CMC tools

for educational purposes is still minimum (Bosch, 2009; Selwyn, 2009; and Hew, 2011).

Students use these internet tools mostly for social needs. However, a more recent study

(Vrocharidou & Efthymiou, 2012) shows that, although still little, there are evidence that

students already use CMC technologies, such as emails, SNSs (Social Networking Sites), and

IMs (Instant Messagings) or online chats, for academic needs. Demirci (2007) also found that

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 493 teachers to discover creative and effective ways to cope with the nature of their students to

promote and facilitate learning (Godwin-Jones, 2010). Another positive finding is also

reported by Landu Amah (2012) mentioning that EFL students has also used CMC on

Facebook, for practicing their English. It is a common phenomenon that foreign language

learners are practicing using the target language by communicating with their teachers, peers,

and native speakers at a distance. The ability of the language learners to collaborate, create,

and share content or ideas with other users might prove useful for language learning

(Lomicka & Lord, 2009), which might also play significant role in their second language

acquisition (SLA).

With the fact that there have been studies suggesting the ideas of embracing CMC

technologies in educational uses and our students are already familiar with these

technologies, this paper is aimed at two points. First, this paper will discuss the underlying

theories that supports the incorporation of CMC technologies in language teaching and

learning. Second, practical examples of how these technologies have and could be utilised in

English as a Foreign Language (EFL) classrooms will also be elaborated.

RELEVANT THEORETICAL AND RESEARCH BACKGROUND

The Internet and Language Learning

The technology brought by the internet has brought a new medium in human communication.

Traditionally, people use spoken and written forms of language to communicate each other.

With the internet now, particularly after the introduction of Web 2.0, people could easily

connect to each other using various internet tools such as emails, IMs, and SNSs, which have

been widely known as Computer Mediated Communication (CMC). This new phenomenon

in communication has intrigued some linguistic and educational researchers to discuss its

potentials in educational environment (e.g. Erlich et al, 2005; Baran, 2010; Godwin-Jones,

2010;; Hew, 2011; and Anderson et al, 2012), particularly in language teaching and learning

(e.g. Lafford & Lafford, 2005; Grosseck et al, 2011; and Sumakul, 2011), and really apply it

in language classrooms (e.g. Blattner & Fiori, 2009; Mills, 2010; Shih, 2011; and Sumakul,

2012) .

In implementing this technology into classrooms, Roth (2009) argues that CMC activities

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 494

Plato‟s principles of education. Traditional classrooms are losing the ability to challenge and

motivate our internet generation students, who expect more from a class, not only lectures

and books. Today‟s students are accustomed to living with the internet technologies in their

everyday life. They are considered as digital natives (Prensky, 2001), who would enjoy

computer and internet resources to be used in their classrooms (Luke, 2006). Bringing digital

technologies in our teaching would make the class more interesting for the students. These

internet technologies have been embedded in our students‟ daily lives, and as as Chapelle (2003) suggests that we, teachers, could make use of these technologies and explore their

implications for language teachers and researchers. With the same sense, Pritchard (2007: 2)

argues:

“With the growing awareness of the theory associated with learning and a growing interest in the ways that new technologies might change the way that teachers teach and children learn, there is scope, perhaps even a real need, to look at what is currently known about learning, especially in relation to the new possibilities afforded by Information and Communications Technologies

(ICTs).”

Defining CMC

CMC exists not only in the form of text-based form but also in the form of

video-conferencing, where people could talk like in Face-to-face (FTF) conversation. However, in

linguistic studies, to distinguish it from traditional writing processes and FTF conversation,

CMC is mostly related to text-based communication. Within that sense, CMC is defined as

„the direct use of computers in a text-based communication processes‟ (Miller & Sullivan, 2006: 2). Furthermore, CMC also comes in two different modes, synchronous and

asynchronous (Hyland, 2003). Synchronous writing occurs when people interact in real time,

while asynchronous writing occurs when people communicate in a delayed way.

In this era of Web 2.0 technology, CMC could be found, for example, in chats as

synchronous, and in emails as asynchronous. In SNSs, such as Facebook or Twitter, CMC

could occur both in synchronous or asynchronous forms.

Features of CMC: A Combination of Spoken and Written Forms

From traditional point of view, there were two main modes of communication, written and

spoken modes (Meyer, 2009). However, since the era of the internet, particularly after the

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 495 incorporates both features of spoken and written forms. Although the mode of

communication is written, it also employs several features of oral communication. Within this

scope, CMC is viewed as the bridge (Chun, 1994; Handley, 2010) or the hybrid (Kost, 2008)

of spoken and written languages. In addition, for this written and spoken forms incorporation,

there are several names suggested for CMC. For example, Beauvois (1998) call this

„conversation in slow motion‟ and Crystal (2001) simply calls it „netspeak‟.

What features of speaking and writing are mediated in CMC? First, we can view it from their

temporal elements of language production. Speaking is online, because the message, because

the message is conveyed at the time of speaking, whereas writing is offline because the

message is conveyed not during language production, but later, when other people read the

written language. These characteristics in both modes are incorporated in CMC, with the

spontaneity and informal style of spoken language are contained within the production mode

of written language. For this reason, Murray (1991) considers CMC as written speech.

Second, it can be discussed from their functions. Writing is reflectional and speaking is

interactional (Warschauer, 1997). These two features are also attached to CMC. When you

communicate on the internet, it is interactional and at the same time reflectional because

people still can see and edit their message before sending it to their interlocutor during online

interactions. Moreover, as it is written using computers, it could easily be stored for

reflectional purposes.

Incorporating the features of both spoken and written languages, CMC is considered as the 4th

revolution in human communication and cognition after language, writing, and print (Harnad,

1991). Meanwhile, Crystal (2011), in describing CMC with the internet as the medium, sees

the internet as the 4th medium of linguistic communication after the phonic medium for

speaking, graphic medium for writing, and visual medium for signing.

Advantages of CMC

Research suggests that CMC could bring positive effects to EFL students. In terms of

language learning, the first benefit can be seen from the perspective of linguistics. It has been

found that that CMC could help the students produce a higher level of language complexity

(Chun, 1994), amplify students‟ attention to linguistic forms (Warschauer, 1997), help the

development of oral proficiency (Payne & Ross, 2005), trigger greater amount of language

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 496

Fiori, 2009), and have the potential for improving learners‟ cognitive skills in linguistic

analysis (Sumakul, 2011).

From the psychological perspective, CMC could engage learners to the learning activities

(Meskill & Anthony, 2007; Mills, 2010), create a positive effect on the student-to-student and

student-to-teacher relationship (Mazer et al, 2007), and provide a less stressful

communicative environment (Kost, 2008), and develop a positive attitude towards learning

(Grossecka et al, 2011). Referring back to linguistic perspective, these positive psychological

conditions such as less stressful and engaging environment and positive attitude toward

learning are important when they come to language production, in particular if the language

used is not the speaker‟s first or native language.

These advantages are actually the ground why CMC is suggested as a good tool in language

learning. Bringing CMC activities into EFL classrooms would provide learners with an

effective and fun way in learning English. Kim (2009) states that compared to learning a

language without CMC, using CMC can motivate students to learn language better.

In the next section we are going to see a number of CMC tools in the internet and how they

were utilised in foreign language classrooms, covering different skills. Although some of the

methods used were not in English classrooms, they could be adapted in EFL learning and

teaching.

CMC PRACTICES IN LANGUAGE CLASSROOMS

Facebook in Grammar Classroom

Facebook is mostly used for social needs, but one use of FB is for learning (e.g. Kabilan,

Ahman, & Abidin, 2010; Landu Amah, 2012). Within this purpose, Grosseck et al (2011:

1426-1427), looking at different previous studies, summarises how Facebook can be

beneficial to not only students but also teachers.

Looking from teaching sequence point of view and collaborating with 3 other English

teachers, Sumakul (2012) explores how teachers use Facebook in 3 different EFL classrooms

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 497 1. After the lessons on gerund and infinitive phrases, students are given homework to

write status using gerund phrase and/or infinitive phrase on their Facebook account

and also to comment each other. As the teachers are also friends with the students on

Facebook, she then monitors this activity from home, and discuss the language the

students use on their next meeting.

2. During a lesson about perfect and continuous tenses, the students are asked to go to

Facebook using their mobile phones or laptop computers. Working in groups of three,

first they are asked to find posts containing perfect or continuous tense on their

friends‟ posts, then they are asked to error analyse the posts, and finally they need to write on their Facebook statuses sentences containing continuous or perfect tense.

3. At home students are asked to write any Facebook status in English, not necessarily

related to their previous lesson. The teacher monitors this from home, and on the next

meeting, she provides feedback, error analysing and explaining the ungrammatical

posts.

In his discussion, Sumakul (2012) explains that when students do the Facebook homework in

point 1 and 3, students do noticing on isolated grammatical patterns, which is a

consciousness-raising activity. This is important for focused attention and could promote

acquisition.

Facebook group for communicative grammar practice

Another Facebook activity was also carried out by Sumakul2 early this year. In his grammar

class for 1st year English Department university students, he created a Facebook group for

students to practise the lessons they get in the classrooms. Students were given assignments

to write on this group‟s wall and to comment each other.

2

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 498

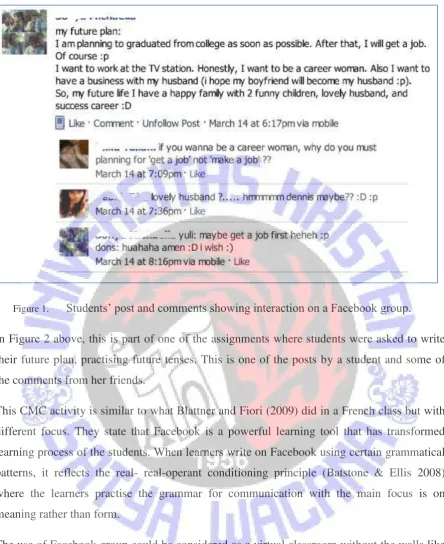

Figure 1. Students‟ post and comments showing interaction on a Facebook group.

In Figure 2 above, this is part of one of the assignments where students were asked to write

their future plan, practising future tenses. This is one of the posts by a student and some of

the comments from her friends.

This CMC activity is similar to what Blattner and Fiori (2009) did in a French class but with

different focus. They state that Facebook is a powerful learning tool that has transformed

learning process of the students. When learners write on Facebook using certain grammatical

patterns, it reflects the real- real-operant conditioning principle (Batstone & Ellis 2008)

where the learners practise the grammar for communication with the main focus is on

meaning rather than form.

The use of Facebook group could be considered as a virtual classroom without the walls like

in physical classrooms. By setting the privacy of the group, that only the members of the

group (i.e. the teacher and the students) can participate and see the posts, the safety of the

real-world classroom could be preserved. Harmer (1998) says that keeping the safety of the

classroom is important because it could assist their language use in the real world. Schwartz

(2010) also makes use Facebook Group in her teaching. She creates a Facebook group for

mentoring university students. Facebook groups allow the students (and also teachers) to

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 499 Facebook in reading classroom

One of my colleagues, Henry Wijaya, also used Facebook in his EFL classroom. It was a

reading class. In introducing scanning and skimming skills to the students, the students were

asked to go to their Facebook account using their mobile phones to practise scanning and

skimming. For scanning, the students were asked to go to the homepage (newsfeed) of their

Facebook and find who had a birthday that day, what the shortest status was, and what the

longest one. For skimming, they were asked to read their friends‟ statuses on their Facebook homepage and generalise the mood of the statuses. Since it was Monday, the mood was „I hate Monday‟.

He admitted that it was only a spontaneous idea since he thought that the original material

was rather boring, and it could have been better with more thoughts and preparation.

However, by using Facebook, the activity became more engaging to the students. The

students could understand the concepts of skimming and scanning in reading and experience

them in their own context. It is an example of contextualised learning (Roth, 2009).

Facebook in writing classroom

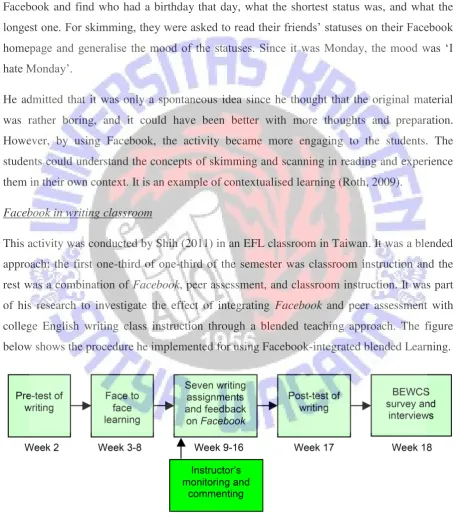

This activity was conducted by Shih (2011) in an EFL classroom in Taiwan. It was a blended

approach: the first one-third of one-third of the semester was classroom instruction and the

rest was a combination of Facebook, peer assessment, and classroom instruction. It was part

of his research to investigate the effect of integrating Facebook and peer assessment with

college English writing class instruction through a blended teaching approach. The figure

below shows the procedure he implemented for using Facebook-integrated blended Learning.

Figure 2. Implementation procedure for using Facebook-integrated blended learning

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 500 From the finding of the research, the researcher suggests that incorporating peer assessment

and Facebook in EFL writing classrooms is interesting and effective for the students. They

can improve their writing skills not only from the in-class instruction but also from

cooperative learning through Facebook. Moreover, blended learning that combines online and

face-to-face instruction could be beneficial for both the teachers and the students.

Email for collaborative reading

Sumakul3 tried out this activity during an ESP reading class for economic university students

as part of his research in finding out students‟ perception on email-based assignments. During the course, students were given a number of email based reading assignments. At first, the

students were given a text to read and the questions they needed to answer and send the

answers to the teacher by email. At the end of the semester the students needed to work

collaboratively in their reading activity. The following tasks were set up by the teacher:

1. Students work in groups of 4.

2. The teacher finds a text in Wikipedia and send the link to Student 1.

3. Student 1 reads the text and develops 2 questions based on the text and sends them to

Student 2.

4. Student 2 reads the text, answers the questions from Student 1, develop another 2

questions and sends them to Student 3.

5. The same activities are repeated until Student 4 sends two questions to Student 1.

6. At the end of this email cycle, the teacher give feedback to all of the students in each

group.

With this email assignments, students can interact with their friends at their own pace and

take time think about their responses rather than being “put on the spot”, which could hinder

their communication, as in the physical classroom (Shih, 2010). They could also get help

from various resources, their friends, dictionaries, or other online tools, while completing the

3

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 501 task. This is an example of the capability of technologies in enabling our traditional 4-wall

classroom to be connected to the real world.

Google Talk for communication and translation practice

This was conducted in a Bahasa Indonesia class of the PIBBI4 level 6 programme, focusing

on translation skills. In using Google Talk, an IM tool, the students were asked to work in

groups of 4 with the following tasks:

1. Student 1 chats with Student 2 in Bahasa Indonesia.

2. Student 2 translates the message from Student 1 into English and uses it to chat with

Student 3.

3. Student 3 translates the English message from Student 2 into Bahasa Indonesia and

uses it to chat with Student 4.

4. Student 4 replies the Bahasa Indonesia message from Student 4 also in Bahasa

Indonesia.

5. Student 3 translates the Bahasa Indonesia message from Student 4 into English and

uses it to chat with Student 2.

6. Student 2 translates the English message from Student 3 into Bahasa Indonesia and

uses it to chat with Student 1.

7. Student 1 replies back to Student 2 in Bahasa Indonesia.

The complete flow of the interaction in this activity is depicted in Figure 3 below.

Student 1 Student 2 Student 3 Student 4

Bahasa Indonesia

English Bahasa

Indonesia

4

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 502

Figure 3. Students‟ interaction using Google Talk in translation class.

From the figure above we could learn that the actual conversation is actually conducted

between Student 1 and 4 and Student 2 and 3 are the translators. One might argue that with

this activity only Student 2 and 3 experience the benefit of the learning from this CMC tool.

However, of course the teacher could ask the students to change roles for everyone could

have the same interaction and learning experience. The following figure is an excerpt from

the conversation.

Student 1 transcription Student 4 transcription

11:23 AM Student 1: Halo mas baik :) apa kegiatan anda hari ini?

11:30 AM Student 3: Aku juga sangat baik :) apa kamu

melakukan hari ini?

11:34 AM Student 2: Hanya bekerja sampai jam 5 siang ini, apa kegiatan Anda? sangat suka itu, saya suka aksi film dan horor film, bagaimana dengan Anda?

11:41 AM Student 4: iya saya sangat suka , saya suka film action dan horor, kalo kamu ?

Figure 4. An excerpt from the students‟ interaction using Google Talk

The shaded area is actually the actual conversation between Student 1 and 4, while

non-shaded area is the translation provided by Student 2 and 3. Engaging, contextual and

communicative, this activity could help pragmatic development of the students. Kasper

(1997) mentions two types of learning activities: activities that are able to help raising

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 503 practise the target language for communication. Both types were incorporated in this Google

Talk activity.

CHALLENGES

Despite the benefits of CMC on language learning as pointed out by various studies, there

things we need to consider in implementing CMC activities in our EFL classrooms. In this

paper, two important challenges (probably, out of many) are suggested:

1. Some teachers are digital immigrants

Prensky‟s (2001) terms of digital immigrants could be applied to some teachers.

Compared to their digital native students, these teachers are not really capable with or

accustomed to using digital technology such as the internet as the medium (Crystal,

2011) of CMC activities. This condition could lead to the fact that these teachers

would not be comfortable of designing their teaching with CMC activities. Even if

they try to use these digital technologies, they would be hampered by their nondigital

cultural heritage (Prensky, 2001). Take the Facebook case for an example. Ratcham

and Firpo (2011) report that Facebook is easy-to-use and familiar for the students, but

is it the same case for the teachers? For CMC activities to be effectively used in

classrooms, Karpati (2009) suggests that ICT (Internet and Communication

Technology) competences are needed, not only for the students, but also for the

teachers.

2. Technical obstacle: slow data transfer and still expensive internet fee

Particularly in Indonesia, in general the internet is still slow and expensive for most

learners. Even if we could have our schools and campuses connected to the internet

and have the CMC activities done in the language and computer laboratories, not all

schools could afford the connection fee. Slow data transfer is also inefficient and

would disturb the communication process in a CMC activity.

CONCLUSION

As Web 2.0 technology has garnered much attention from researchers and practitioners

(Ractham & Firpo, 2011), more research and examples are available for the use of CMC in

educational environment, or particularly in language classrooms. Other online tools are also

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 504 learning. There are Wiki documents, blogging, or other SNSs. For example, Stevenson and

Liu (2010) provide an analysis of how a number of Web 2.0 sites can be used for language

learning. Another example, Mollett et al (2011) provide guidelines of how Twitter can be

used in university academic uses. It now depends on teachers‟ willingness, creativity, and

digital competences to incorporate these online tools in designing their classroom materials.

Using these technologies in our classroom can facilitate learner- centred approach to our

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 505 REFERENCES

Anderson, B., Fagan, P., Woodnutt, T., & Chamorro-Premuzic, T. (2012). Facebook

Psychology: Popular Questions Answered by Research. Psychology of Popular Media culture, 1(1), 23-37.

Baran, B. (2010). Facebook as a formal instructional environment. British Journal of Education Technology, 41(6), E146-E149.

Batstone, R., & Ellis, R. (2009). Principled Grammar Teaching. System(37), 194-204.

Beauvois, M. H. (1998). Conversations in Slow Motion: Computer-Mediated Communication in Foreign Language Classroom. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 54(2), 198-217.

Blattner, G., & Fiori, M. (2009). Facebook in the Language Classroom: Promises and Possibilities. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 6(1), 17-28.

Bodomo, A. R. (2010). Computer-Mediated Communication for Linguistics and Literacy. New York: Information Science Reference.

Bosch, T. E. (2009). Using online social networking for teaching and learning: Facebook use at the university of cape town. Communicatio: South African Journal for

Communication Theory and Research, 35(2), 185–200. Chapelle, C. A. (2003). English Language Learning and Technology.

Amsterdam/Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Crystal, D. (2001). Language and the Internet. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Crystal, D. (2011). Internet Linguistics: A Student Guide. London: Routledge.

Demirci, N. (2007). University Students' Perceptions of Web-Based vs. Paper-Based

Homework in a General Physics Course. Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science & Technology Education, 3(1), 29-34.

Erlich, Z., Erlich-Philip, I., & Gal-Ezer, J. (2005). Skills required for participating in CMC courses: An Empirical Study. Computers & Education, 44, 477–487.

Godwin-Jones, R. (2010). Emerging Technologies: Literacies and Technologies Revisited. Language Learning & Technology, 14(3), 2-9.

Grosseck, G., Branb, R., & Tiruc, L. (2011). Dear teacher, what should I write on my wall? A case study on academic uses of Facebook. Procedia Social and Behavioral Sciences, 15, 1425-1430.

Handley, Z. (2010, October 21). Computer Mediated Communication: Bridging the gaps between writing and speaking. Retrieved March 31, 2012, from Oxford University Press – English Language Teaching – Global Blog:

http://oupeltglobalblog.com/2010/10/21/computer-mediated-communication/

Harmer, J. (1998). How To Teach English, An introduction to the practice of English language teaching. Longman.

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 506 Hew, K. F. (2011). Students' and Teachers' Use of Facebook. Computers and Human

Behaviour, 27, 662-676.

Hyland, K. (2003). Second Language Writing. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Karpati, A. (2009). Web 2 technologies for Net Native language learners: a "Social CALL". ReCALL, 21(2), 139-156.

Kasper, G. (1997). The role of pragmatics in language teaching education. In K. Bardovi-Harlig, & B. S. Hartford (Eds.), Beyond Methods:Components of Second Language Teacher Education (pp. 113-136). New York: McGraw-Hill.

Kost, C. R. (2008). Use of Communication Strategies in a Synchronous CMC environment. In S. S. Magnan (Ed.), Mediating Discourse Online (pp. 153-190). Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Lafford, P. A., & Lafford, B. A. (2005). CMC Technologies for Teaching Foreign Languages: What's on the Horizon? CALICO Journal, 679-709.

Landu Amah, O. (2012). Code Mixing in CMC. Satya Wacana School of Foreign Languages, English Language and Literature Department. Salatiga: Satya Wacana School of Foreign Languages.

Lomicka, L., & Lord, G. (2009). Introduction to social networking, collaboration, and Web 2.0 tools. In L. Lomicka, & G. Lord (Eds.), . In L. Lomicka & G. Lord (Eds.), The next generation: Social networks and online collaboration in foreign language learning. San Marcos: CALICO.

Luke, C. L. (2006). Situating CALL in the broader methodological context of foreign language teaching and learning: Promises and possibilities. CALICO Monograph, 5, 21-41.

Mazer, J. P., Murphy, R. E., & Simonds, C. J. (2007). I‟ll See You on “Facebook”: The

Effects of Computer-Mediated Teacher Self-disclosure on Student Motivation, Affective Learning, and Classroom Climate. Communication Education, 56(1), 1-17.

Meskill, C., & Anthony, N. (2007). Form-focused Communicative Practice via CMC: What Language Learners Say. CALICO Journal, 25(1), 69-90.

Miller, K. S., & Sullivan, K. P. (2006). Keystroke Logging: An Introduction. In K. P. Sullivan, & E. Lindgren (Eds.), Computer Keystroke Logging and Writing: Methods and Applications (pp. 1-10). Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Mills, N. (2010). Situated Learning through Social Networking Communities: The Development of Joint Enterprise, Mutual Engagement, and a Shared Repertoire. CALICO Journal, 28(2), 345-368.

Mollett, A., Moran, D., & Dunleavy, P. (2011). Using Twitter in university research,

teaching and impact activities: A guide for academics and researchers. London: LSE Public Policy Group.

Motteram, G., & Sharma, P. (2009). Blending Learning in a Web 2.0 World. International Journal of Emerging Technologies & Society, 7(2), 83-96.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On The Horizon, 9(5), 1-6.

Research in Teacher Education : What, How, and Why?, November 21-22, 2012, UKSW 507 Promnitz-Hayashi, L. (2011). A Learning Success Story Using Facebook. Studies in

Self-Access Learning Journal, 2(4), 309-316.

Ratcham, P., & Firpo, D. (2011). Using Social Networking Technology to Enhance Learning in Higher Education: A Case Study Using Facebook. 44th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, (pp. 1530-1605).

Roth, A. D. (2009). Following Plato's Advice: Pedagogy and Technology for the Facebook Generation. Journal of Philosophy and History of Education, 59, 125-128.

Schwartz, H. L. (2010, January). Facebook, the New Classroom Commons? The Education Digest, pp. 39-42.

Selwyn, N. (2009). Faceworking: Exploring students‟ education-related use of Facebook. Learning, Media and Technology, 34(2), 157–174.

Shih, R.-C. (2011). Can Web 2.0 technology assist college students in learning English writing? Integrating Facebook and peer assessment with blended learning. Australasian Journal of Educational Technology, 27(Special Issue, 5), 829-845.

Stevenson, M. P., & Liu, M. (2010). Learning a Language with Web 2.0: Exploring the Use of Social Networking Features of Foreign Language Learning Websites. CALICO Journal, 27(2), 233-259.

Sumakul, D. T. (2011). EFL Learners' Communication Strategies in Coping with

Grammatical Difficuties in Synchronous CMC. Liverpool: University of Liverpool.

Sumakul, D. T. (2012). Facebook in Grammar Classrooms: A Look at 3 EFL Classes in Indonesia. The New English Teacher, 6(1), 60-81.

Vrocharidou, A., & Efthymiou, I. (2012). Computer mediated communication for social and

academic purposes: Profiles of use and University students‟ gratifications. Computers & Education, 58, 609-616.

Warschauer, M. (1995). Virtual Connections: Online Activities and Projects for Networking Language Learners. Honolulu: Second Language Teaching and Curriculum:

University of Hawaii.