ABSTRACT An initial study on the habitat distribution and diversity of plants as feed resources for mouse deer (Tragulus javanicus) and barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak) was conducted at Gunung Halimun National Park. The survey was carried out by visiting places where mouse deer and barking deer are usually seen, and collecting specimens of the plant species on which those animals feed. In Gunung Kendeng the mouse deer prefers forest habitats up to a height of 1,100 m asl, such as dense bush, rock crevices or tree hollows, dense tea plantations, and bush areas not far from rivers. Barking deer prefer forests up to a height of 1,100 m asl in Gunung Kendeng, but up to 1,600 m asl in Gunung Botol. Barking deer prefer dense bush on the forest edges. Results showed 50 plant species consisting of 22 families as possible feed resources for mouse deer and barking deer.

Key words: feed plant, habitat, Muntiacus muntjak, Tragulus javanicus.

Mouse deer (Tragulus javanicus), categorized in family tragulidae, and barking deer (Muntiacus muntjak), categorized in family cer vidae, are distributed in Indonesia on Sumatra, Java, Kalimantan, and the surrounding islands (Lekagul & McNeely, ). The Mouse deer is the world,s smallest ruminant, and was first discovered in Java (Van Dort, ). It does not have horns and the adult male has canine teeth. It is dispersed throughout the primary and secondary forests of South East Asia (Medway, ), and according to Kudo et al.

( ), has good potential as an herbivorous laboratory animal. People have long used the meat of this animal as a protein resource. The Mouse deer, marked by brown– reddish body hair with three white lines under the chin, is categorized as an endangered species. This condition has been caused by habitat damage due to exploitation of the forest for settlement and plantations, forest fires,

and uncontrolled hunting activities. As an endangered species, the mouse deer is listed in IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals (IUCN, ).

Mouse deer generally live in lowland areas up to an altitude of m above sea level (Payne et al., ), and according to Adhikerana ( ), this animal is one of main tourism assets of the Gunung Halimun National Park in West Java. Understanding the habitat distributions of both the mouse and barking deer, as well as the diversity of forest plants preferred by these animals as their feed resources is an urgent priority if these animals are to be maintained (in situ) in their Gunung Halimun National Park habitat. In addition, the preservation of the dietary plants selected by mouse deer and barking deer is also crucial.

Barking deer footprints are frequently found in Gunung Halimun National Park. The animal has a deer –like posture, and the male has short horns and canines with a smaller, more slender body size than other deer. Barking deer prefer living among the bushes and shrubs growing in abandoned, un–irrigated agricultural fields or teak forests in both lowland and mountainous areas up to , m above sea level. Its body hair is short and delicate whilst longer hairs grow around its ears. The brown–reddish body hair is faded on the bodies of female and young barking deer. The color of its back is darker whilst the hair under parts of the chin, neck, and stomach is white. In Thailand, the Barking deer continues to be hunted for its high quality meat (Lekagul & McNeely, ). Both the mouse deer and the barking deer are solitary species, and both species couple at the time of mating only. Their feeding activities occur at night and in the early morning. Preserving the wholeness of the mouse deer and barking deer habitats, and conserving the plant species these animals use in their diet is necessary to ensure the continued existence of these animals in the Gunung Halimun National Park. Thus it is necessary to identify the nutrient contents of the selected plants, in the form of young leaves, young shoots, flowers, and fruits, for the purpose of finding alternative foods in

Wartika Rosa FARIDA, Gono SEMIADI, Tri H. HANDAYANI and HARUN

Bidang Zoologi, Pusat Penelitian Biologi – LIPI, Jl. Raya Bogor–Jakarta KM , Cibinong , Bogor, E–mail: [email protected]

Habitat distribution and diversity of plants as feed resources

for mouse deer (Tragulus javanicus

) and barking deer

Wartika Rosa FARIDA, Gono SEMIADI, Tri H. HANDAYANI and HARUN

order to keep these animals in captive breeding programs (ex situ), both for research and commercial purposes. The aim of this research was to understand the habitat distributions of mouse deer and barking deer, as well as the diversity and nutrient contents of plants selected by both animals as their feed resources.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A field survey was conducted over days in June using tracks suggested by forest rangers and local people familiar with the presence of mouse deer in the Gunung Halimun National Park. The survey locations (Table ) were in the vicinity of Gunung Kendeng ( m– , m above sea level) and Gunung Botol ( , m – , m above sea level). This survey was an initial study consisting of visiting places where mouse and barking deer are frequently found, observing the habitat distribution, and recording any forest plants these animals include in their diet. The locations/habitats preferred by mouse and barking deer were also recorded. These locations and places were chosen based on the fact that mouse deer and barking deer (and/or signs of the nests of these animals) were frequently found there. Food plant data were obtained based on the types and the parts of food plants (e.g. leaf, trunk, and fruit) eaten by mouse and barking deer. Observing and recording the data of these animals, diet, in this study, is limited to bush/shrub, climbing, grass, and herb.

The plants parts included in the diet were collected in order to build a herbarium and to analyze the nutrient contents.

Plant samples complete with trunks, branches, leaves, flowers, and fruit (if available) were collected, put

between newspapers, and moistened with methylated spirits to prevent decay and facilitate identification at the Bogoriense Herbarium.

In addition, the forest plants samples, in the form of leaves, trunks, flowers, and fruit, were dried under the sun for – days to prevent decay. The samples were kept in plastic bags prior to laboratory analysis. In the laboratory, all the samples were dried in an oven at ºC for – hours, milled and kept in closed containers prior to nutrient content analysis based on Harris method

( ).

During the field research, mouse deer were only seen on two occasions during daylight periods. It is very difficult to see this shy animal unless using a camera trap. Mouse deer and barking deer were distributed in almost all the research locations (Table ) at the foot of Gunung Kendeng, but not in Gunung Botol, Gunung Halimun National Park. The finding of feces, traces of nests and of feed plants, plus information from local people guiding researchers around the forest confirmed this during the research.

It is apparent that the mouse deer lives in areas up to , m above sea level around Gunung Kendeng, whereas literature has mentioned that it can only be seen in areas up to m above sea level (Hoogerwerf, ; Lekagul & McNelly, ). Mouse deer seem to prefer habitat types such as thick, protective bush, holes in trunks, holes in rocks, and areas near rivers. According to Anonymous ( ), the mouse deer is a tropical animal that inhabits primary and secondary forest habitats, and prefers dry land close to springs and dense vegetation. The delicate feet of these species make it difficult to find or even see footprints. Researchers found some feces on the forest floor, and local people reported that mouse

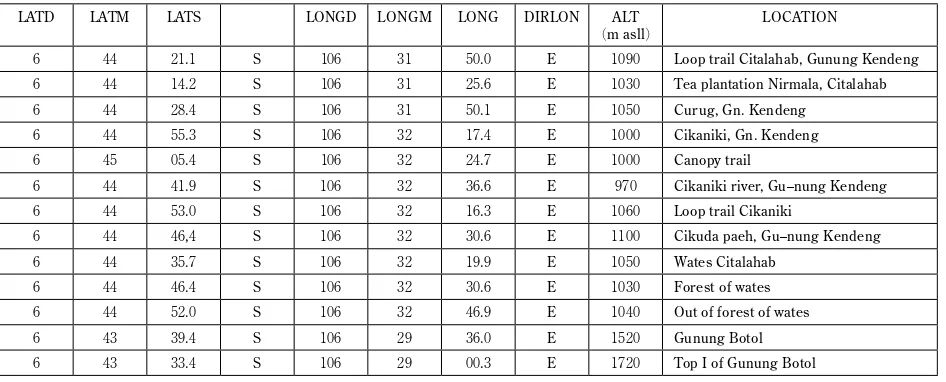

Table 1. Position of research location in Gunung Halimun National Park

LATD LATM LATS LONGD LONGM LONG DIRLON ALT

m asll LOCATION

. S . E Loop trail Citalahab, Gunung Kendeng

. S . E Tea plantation Nirmala, Citalahab

. S . E Curug, Gn. Kendeng

. S . E Cikaniki, Gn. Kendeng

. S . E Canopy trail

. S . E Cikaniki river, Gu–nung Kendeng

. S . E Loop trail Cikaniki

, S . E Cikuda paeh, Gu–nung Kendeng

. S . E Wates Citalahab

. S . E Forest of wates

. S . E Out of forest of wates

. S . E Gunung Botol

deer were frequently seen coupling by the sides of rivers flowing in the area of Gunung Kendeng, and sometimes drinking water there. Mouse deer and barking deer have also been seen under tea bushes growing in the Gunung Halimun National Park, and barking deer have frequently been observed during the afternoon on open land consisting of young tall, coarse grasses.

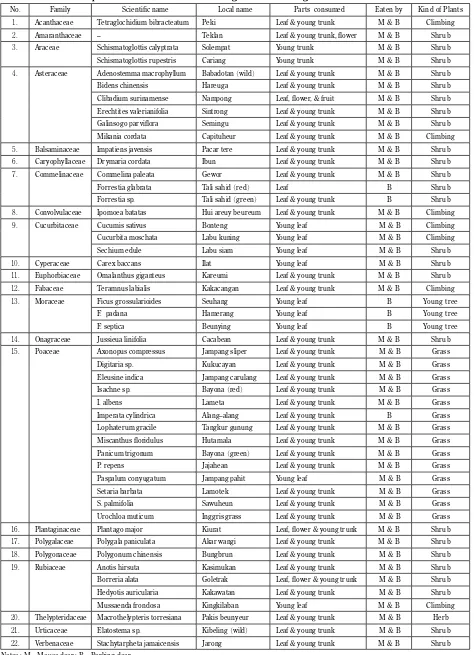

Fifty species of feed plants grouped into families were documented during the course of this study. Table shows that all plant species consumed by mouse deer ( species) are also consumed by barking deer. However, there are feed plants species consumed by barking deer, namely Foorestia glabrata, Forrestia sp., Ficus grossularioides, F. padana, F. septica, and Imperata cylindrica, which are not consumed by mouse deer. Medway ( ) reported that the forest mouse deer is ver y selective, consuming plants such as bushes, some grasses, and fruits lying on the forest floor, whilst according to Kay et al. ( ), the mouse deer prefers leaves containing water, seeds, and easy–to–digest fruits, such that it is categorized as a browser or concentrate selector (Agungpriyono, ). On the other hand, the barking deer, although also categorized as a browser or concentrate selector, consumes a higher number of grass types than the mouse deer. The barking deer also consumes leaves, bushes, herbs, and forest fruit (Leakagul & McNeely, ).

The Barking deer differs from other ruminants in that it does not like grasses in the vegetative phase but prefers the young buds of tall, coarse grasses that grow after fire. This willingness to consume young buds in burnt fields is linked with the effort of the barking deer and other Cervidae species to meet their mineral needs, and is especially so for male animals growing velvet (Semiadi, ).

There are some plant species consumed by barking deer that are not selected by mouse deer as dietary resources. This fact is seemingly caused by the fact that the plants contain alkaloids, which mouse deer cannot tolerate. It is known that some plants protect their leaves from herbivores by producing compounds such as tannins and phenols. A sharp sense of smell allows mouse deer to avoid these plants and concentrate instead on plants and leaves not containing such compounds (Kinnaird, ). Table shows that the kinds of leaves consumed by mouse deer and barking deer are all young, easy to digest leaves with soft and palatable trunks, that contain low tannin and lignin levels (Waterman, ). The report of Kudo et al., ( ) states that the amount of cellulotic microbes in the digestive organs of ruminants

food. It is reported that for rough fiber of . %, the mouse deer is able to digest . % (Nolan et al., ). Considering that this research indicates that the rough fiber content consumed by mouse deer is higher (Table ), it is necessary to observe the optimum capability of this animal to consume rough fiber. On the other hand, because information on the morphology of the digestive organs of barking deer is very scarce, research on the anatomy and morphology of the digestive system of this animal is greatly needed.

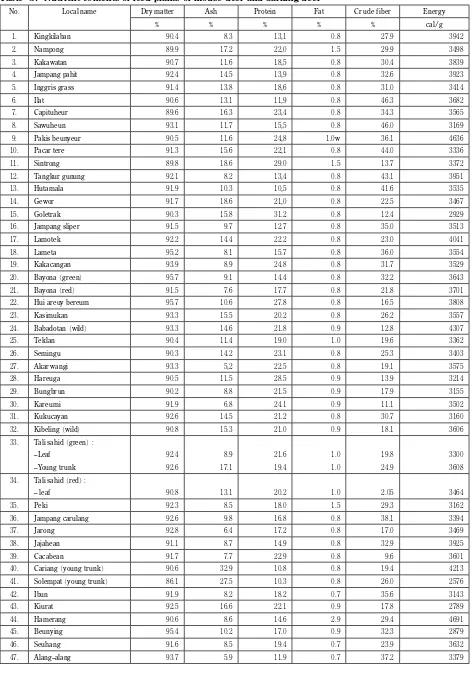

The nutrient contents of the plants mouse and barking deer use as diet resources in their habitats (Table ) show considerable variation. Ash (mineral) content ranges from . % to . % (average . % . ), protein from . % to . % (average . % . ), fat from . % to . % (average . % . ), rough fiber from . % to . % (average . % . ), and energy from , cal/g to

, cal/g (average , . cal/g . ).

The result of nutrient analysis shows that feed plants selected by mouse deer and barking deer as their diet resources have varying value ranges for the content of protein and rough fiber. This condition will greatly facilitate the effort of supplying and selecting the types of alternative feed should (ex situ) captive breeding programs – for both research and commercial purposes – ever be established for these animals.

CONCLUSION

This research concludes that the mouse deer exists in all Gunung Kendeng foot areas up to , m above sea level, but does not exist in the foot areas of Gunung Botol, whereas the barking deer is distributed in both areas. The types of habitats preferred by the mouse deer are dense, protected areas such as under tea bushes, holes in tree trunks, holes in rocks and nearby rivers, whilst the barking deer prefers protected bushes in forests and non–irrigated fields. This research also resulted in a documentation of species including families of forest plants selected by mouse and barking deer as diet resources.

Wartika Rosa FARIDA, Gono SEMIADI, Tri H. HANDAYANI and HARUN

Table 2. List of feed plants of mouse deer and barking deer in Gunung Halimun National Park

No. Family Scientific name Local name Parts consumed Eaten by Kind of Plants . Acanthaceae Tetraglochidium bibracteatum Peki Leaf & young trunk M & B Climbing . Amaranthaceae – Teklan Leaf & young trunk, flower M & B Shrub . Araceae Schismatoglottis calyptrata Solempat Young trunk M & B Shrub Schismatoglottis rupestris Cariang Young trunk M & B Shrub . Asteraceae Adenostemma macrophyllum Babadotan wild Leaf & young trunk M & B Shrub Bidens chinensis Hareuga Leaf & young trunk M & B Shrub Clibadium surinamense Nampong Leaf, flower, & fruit M & B Shrub Erechtites valerianifolia Sintrong Leaf & young trunk M & B Shrub Galinsogo parviflora Semingu Leaf & young trunk M & B Shrub Mikania cordata Capituheur Leaf & young trunk M & B Climbing . Balsaminaceae Impatiens javensis Pacar tere Leaf & young trunk M & B Shrub . Caryophyllaceae Drymaria cordata Ibun Leaf & young trunk M & B Shrub . Commelinaceae Commelina paleata Gewor Leaf & young trunk M & B Shrub Forrestia glabrata Tali sahid red Leaf B Shrub Forrestia sp. Tali sahid green Leaf & young trunk B Shrub . Convolvulaceae Ipomoea batatas Hui areuy beureum Leaf & young trunk M & B Climbing . Cucurbitaceae Cucumis sativus Bonteng Young leaf M & B Climbing Cucurbita moschata Labu kuning Young leaf M & B Climbing Sechium edule Labu siam Young leaf M & B Shrub . Cyperaceae Carex baccans Ilat Young leaf M & B Shrub . Euphorbiaceae Omalanthus giganteus Kareumi Leaf & young trunk M & B Shrub . Fabaceae Teramnus labialis Kakacangan Leaf & young trunk M & B Climbing . Moraceae Ficus grossularioides Seuhang Young leaf B Young tree

Table 3. Nutrient contents of feed plants of mouse deer and barking deer

No. Local name Dry matter Ash Protein Fat Crude fiber Energy

% % % % % cal/g

. Kingkilaban . . , . .

. Nampong . . , . .

. Kakawatan . . , . .

. Jampang pahit . . , . .

. Inggris grass . . , . .

. Ilat . . , . .

. Capituheur . . , . .

. Sawuheun . . , . .

. Pakis beunyeur . . , . w .

. Pacar tere . . , . .

. Sintrong . . . . .

. Tangkur gunung . . , . .

. Hutamala . . , . .

. Gewor . . , . .

. Goletrak . . . . .

. Jampang sliper . . . . .

. Lamotek . . . . .

. Lameta . . . . .

. Kakacangan . . . . .

. Bayona green . . . . .

. Bayona red . . . . .

. Hui areuy bereum . . . . .

. Kasimukan . . . . .

. Babadotan wild . . . . .

. Teklan . . . . .

. Semingu . . . . .

. Akar wangi . , . . .

. Hareuga . . . . .

. Bungbrun . . . . .

. Kareumi . . . . .

. Kukucayan . . . . .

. Kibeling wild . . . . .

. Tali sahid green :

–Leaf . . . . .

–Young trunk . . . . .

. Tali sahid red :

– leaf . . . . .

. Peki . . . . .

. Jampang carulang . . . . .

. Jarong . . . . .

. Jajahean . . . . .

. Cacabean . . . . .

. Cariang young trunk . . . . .

. Solempat young trunk . . . . .

. Ibun . . . . .

. Kiurat . . . . .

. Hamerang . . . . .

. Beunying . . . . .

. Seuhang . . . . .

Wartika Rosa FARIDA, Gono SEMIADI, Tri H. HANDAYANI and HARUN

REFERENCES

Adhikerana, A. S. . Keanekaragaman jenis satwa di Taman Nasional Gunung Halimun sebagai aset wisata alam. Laporan Ekspose dan Lokakar ya Potensi Taman Nasional Gunung Halimun dan Pemanfaatannya secara Berkelanjutan. JICA, Puslitbang Biologi – LIPI, dan Ditjen PHPA, Dept. Kehutanan dan Perkebunan. Bandung, – Maret . Pp. – .

Agungpriyono, S., Yamamoto, Y., Kitamura, N., Yamada, J., Sigit, K., & Yamashita, T. . Morphological study on the stomach of the lesser mouse deer (Tragulus javanicus) with special reference to the internal surface. Journal of Veterinary Medical Science54: – .

Anonymous. . Pedoman Pengelolaan Satwa Langka. Jilid I : Mamalia, Reptilia, dan Amphibia. Direktorat Jenderal Kehutanan. Direktorat Perlindungan dan Pengawetan Alam. Bogor.

Harris, L. E. . Nutrition Research Techniques for Domestic and Wild Animals. Animal Science Department, Utah State University, Logan.

Hoogerwerf, A. . Udjung Kulon. The Land of The Last Javan Rhinoceros. Leiden.

IUCN. . IUCN Red List of Threatened Animals. IUCN, Gland, Switzerland and Cambridge, UK. Kay, R. N. B., Engelhardt, Von W. & White, R. E. .

The digestive physiology and Metabolism in Ruminants. st Ed. Avi Publishing Co. Westport,

Conn. USA.

Kinnaird, M. F. . North Sulawesi. A Natural History Guide. Development Institute Wallacea, Jakarta. Kudo, H., Fukuta, K., Imai, S., Dahlan, I., Abdullah, N.,

Ho, Y.W. & Jalaludin, S. . Establishment of lesser mouse deer (Tragulus javanicus) colony for use as a new laboratory animal and/or companion animal. JIRCAS JournalNo. 4: – .

Lekagul, B. & McNeely, J. A. . Mammals of Thailand. The association for the conser vation of wildlife, Bangkok.

Medway, Ld. . The Wild Mammals of Malaya (Peninsular Malaysia) and Singapore. nd Edition.

Oxford University Press. Kuala Lumpur.

Nolan, J. V., Liang, J. B., Abdullah, N., Kudo, H., Ismail,

H., Ho, Y. W. & Jalaludin, S. . Food intake, nutrient utilization and water turnover in the lesser mouse deer (Tragulus javanicus) given lundai (Sapium baccatum). Comparative Biochemistry and PhysiologyIIIA (1): – .

Payne, J., Francis, C. M., & Phillips, K. . A Field Guide to The Mammals of Borneo. The Sabah Society with World Wildlife Fund Malaysia.

Semiadi, G. . Budidaya Rusa Tropika sebagai Hewan Ternak. Masyarakat Zoologi Indonesia. Bogor.

Van Dor t, M. . Note on the Skull Size in The Two Symmetric Mouse Deer Species, Tragulus javanicus Osbeck, and Tragulus napu F. Cuvier, . Institute of Taxonomy Zoology. Zoological Museum, University of Amsterdam. Netherlands. Waterman, P. G. . Food acquisition and processing as

a function of plant chemistry. Pp. – . In Food acquisition and processing in primates (Chivers, D. J., Wood, B. A. and Bilsborough, A. Eds.). Plenum Publishing Corporation, New York.

Received th Mar.

Accepted th June.

. Labu kuning . . . . .

. Labu siam . . . . .